Sacred Texts Sacred Sexuality Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

The Sacred Fire, by B.Z. Goldberg, [1930], at sacred-texts.com

|

Even as the passion of man |

As you look upon the map of Europe, you notice a strip of land hanging down like an old man's whiskers into the Mediterranean waters. This is the troublesome Balkan peninsula, mother of many conflicts, including the last great war. Further down, the whiskers grow thin and scattered, splitting up into tiny bits. This is the land of the ancient Greeks, the clever people who stood at the gateway of the continents, collecting all that came out of the East and sending it forth into the West, retouched a bit here and there, with the attached label "made in Greece."

Among the numerous things the Greeks collected were also gods. Many a Greek divinity when scratched will be found to hail from some country back east, or from an island in one of the seas not far off. It may have seen better days on the banks of the Nile, in the streets of Babylon, in the bushes of Ethiopia, or in Cathay. But its locks were evenly trimmed and its nose straightened à la Greek.

Like all good collectors, the Greeks had a sense of order.

[paragraph continues] They could not let all these gods roam aimlessly about Hellas. So a mountain was dedicated to the folk that were divine, where they might live their own lives with as little interference in the affairs of man as man deemed necessary. All gods were delegated to Mount Olympus.

Once on the mountain, they went about their lives much the same as the humans in the valley below. There, god struggled with god for power or love, the 'vanquished undergoing torture or eternal imprisonment. There, they loved and suffered, their hearts eaten away by jealousy; there, they also loved and were happy, basking in the sunshine of bliss. On Olympus they were born, grew up, begat children, and there, some of them perished, like the mere humans at the foot of the mountain.

Fate and luck played their parts above as well as below. Some of the gods, for all their divine presence, cut no figure at all, while others dominated, not only their immediate family, but the very length and breadth of Olympus. There was Hera, mother of gods, not much of a figure in the feasts and festivities on the mountain, yet a kindly creature, in whose arms her many children might find peace and protection. Yonder was Aphrodite, charming in her beauty, sprung from the foam of the sea when Poseidon was good naturedly at play. There was Pan, the merrymaker of the divine dwelling-place, stirring the heart with love and laughter. There was chaste Artemis, athletic goddess of the hunt; Hermes with his winged feet, fleet messenger of the gods; and the swart and limping Hephæstus, their mechanic, hammering out the heavy armors on his smoky forge. And there was Pallas Athena, goddess of wisdom and learning, sprung fully armed from the head of Zeus, best loved of all the

gods and goddesses, but most cherished by the intellectual Athenians.

One could go on indefinitely naming the worthies among the gods, not to mention the lesser lights sauntering about and in between the mighty on the Mount. Yet, to one

Click to enlarge

When gods made merry

who knew his way among them, they were not so numerous after all. Many were the names entered on the Divine Register and many the passports held by the Keeper of Records of individual divinities. Yet, in their essence, many were much the same, changing only with time and locality. Gods like Fascinus, Tutunus, Mutinus, Liber, Bacchus, all bore different names; but they were all one

god. They were the same as Priapus, a naturalized citizen on Olympus, having been born in Lampsacus on the Hellespont.

Once we leave Hellas and wander about lands and continents peopled by man and god, the aliases among gods are by far greater than among men. The very same lady, fanning the embers of love in the hearts of humans, whom we know as Venus, was called Mylitta, or Milidath, by the Assyrians, which to them meant genetrix, mother. To the Persians she was Anahita, and the Arabs called her Alitta. The Chaldeans knew her as Delephat, the Babylonians as Ishtar, the Saracens as Cobar. In the Bible we read of her as Assera, or Astarte. Wherever she was and whatever her name, she was female, young, beautiful, desirable, guarding over the passion of sex and over the sentiment of love.

Thus, setting out on our venture among the gods, we must be guided neither by name nor by origin. Our criterion should be the function of the divinity—the thing he was supposed to do for mankind, in return for which he was rewarded in worship.

Many were the favors that the worthies on the Mount were bestowing upon man below. Whatever he found in the world about him, whether it was a ready cave or a ripe fruit, man took it as a gift from the gods. All that he got by his own effort was also accredited to the divine powers. Were they not guiding him along the path of success, steadying his bow and properly setting his net? Pious people today see "the finger of the Lord" in many things happening about them. Old Anthropology Adam was

even more god-intoxicated. His world was absolutely god-controlled.

Man may ever have been the ungrateful creature he is now reputed to be. Yet he was never an ingrate to his god. He always returned full value in worship, prayer, and sacrifice for the favors that the higher powers bestowed upon him. If Zeus had ever called the gods and people together for an accounting, the final balance would have shown a divine indebtedness to mankind, rather than the contrary.

Among all these divine gifts there was one that man even more fully appreciated; one might say, over-appreciated. It was that awe-inspiring power that ushered in new life, birth, generation. Whether it was a new stalk breaking out of the black soil, the first quiver of a new leaf upon the limb of a tree, the thud of a new born dropping in the herd, or the first cry of a babe on the bed of hides in his cave—it delighted man's heart. It overwhelmed him with its shroud of mystery no less than with the boundless joy he felt, yet could not explain.

Standing there at the scene of regeneration, Old Anthropology Adam had neither benefit of priest or of sacrament, nor the thought or the knowledge of religion as such. Still, there he was, a worshipper before what was to be later revealed to him as "divine presence." He was awed, mystified, rejoicing, adoring. Above all, he was exalted, well on the way toward the state of ecstasy, in which his heart seemed to be melting away in happiness; a state man was later to conceive of as entering into communion with the "all", the cosmos, the universe, God.

Of all that man received from the hands of the gods nothing was so highly prized as the gift of love and none

was more readily and with greater exaltation repaid in its own kind. The generative god served man via sex; man worshipped him in return sexually. The god whose will it was to bring abundance to the earth would be glad to see man, his humble servant, seeking in his own small way to enhance abundance about him. The power whose function it was to cause births through the union of the sexes would feel flattered to see humans in union. It was a way of realizing the will of the god among men. It was akin to our belief that a righteous God would have righteousness prevail in human society—a realization of the Kingdom of Heaven upon earth. Sex worship thus became the appropriate recompense, reward, blessing—however one may designate the religious attitude—for the revered god of love and procreation.

Like all forms of religious service, the worship of the creative power was not only pleasing to the god, but it also enraptured man. It carried with it the usual pleasures accompanying the exercise of the sexual function. Furthermore, by its fusion with other mental components entering into the religious attitude, passion became fired and all-embracing. Grief and pain often intensify passion; fear, awe, and devotion are oil on the flame of love.

Still, sex worship did for man even more than that. It was the redeemer of his imprisoned soul. It provided an outlet for those sexual passions which the race had known in its infancy, but which later had apparently been driven out of heart and mind. Memories of them may have lingered on, as they had not been entirely effaced from the earth. At all events, the desire was there, smouldering beneath the heap of suppressions.

Once, man was a free agent sexually. He could mate

with any female that came his way. Now, he was in chains. Sex worship came to break the fetters and, if only for a brief space of time, to bring back to man the freedom that had been his. What was forbidden at large in the bush not only was permitted, but, in fact, became a duty in the temple of the gods.

When, in the temple, man was free to do as he pleased sexually, he pleased to do it with all the freedom possible. Venturing far out across land and sea to India, we come upon a people, Kauchiluas by name. On the day of a festival we may follow them along the crooked path through fields of corn until we reach the woods. Further, we cannot go. Beyond, it is only for their own and for the initiated. Yet we do know what is happening there.

The Kauchiluas enter the temple individually. Here the sexes separate, the males proceeding further inside, while the females remain for a few minutes with the priest. They remove their bodices and deposit them in a box held by the divine representative, each receiving a number or check for the bodice deposited. Presently they join the males and the service is begun.

There is song and prayer and dance. As the ritual advances, hearts beat faster and eyes dilate in the glimmer of the burning fire in the front. Then the priest marches about the temple with the box of bodices offering it to each male, who takes one. The woman who has the number corresponding to that garment thereby becomes his partner for the remainder of the service. She may be a stranger, a young girl, or an old woman; she may be his own sister, or his very mother. Whoever she is, it is her

most sacred religious duty to join with him in the fulfillment of the last sacrament of the worship—the union of the sexes. This rite is exercised in communion within the temple and is accompanied by shrieks and wild exercises of an orgiastic nature.

This service was engaged in by all present, by the most devout and pure-minded women, by persons who were otherwise as modest and chaste as any group of men and women today. To them, this promiscuous union was a sacred and solemn observance; yet, while it lasted, it was an overwhelming passion of sexual fury.

The bodice of the Kauchilua woman was the magic wand that converted an act strictly interdicted as a deadly sin into a sacred duty. There, in the temple, all the veneer that social custom had placed upon the exercise of the sexual function was removed. Accompanied by prayer and song, they reverted to the original form of sex relationship, absolute promiscuity.

The Kauchiluas were by no means the only people to dispose of all their sex taboos in worship. There were many such cases in all parts of the world. It was the same at the sacrifice of the Cartavaya to the Indian god Krishna. Again, it was a feature of the Soma-sacrifice in the Vedic ritual. Among the Nicaraguans, who were otherwise a people unusually strict in sex matters, the women could choose any man they might wish in their annual festival. In the frenzy of religio-sexual excitement, their choice was neither discriminating nor limited. In fact, the more strict a people was in matters of sex, the more likely the individuals were to break out in orgy at their worship. This we see in the story of the tribe of Tarahumare.

Here we have a peaceful, orderly, and reserved people. Whether dancing or singing they never lost their decorum and ever behaved with great formality and fitting solemnity. In fact, their self-control so impressed the traveler, who first came upon them, that he did not hesitate to state that "in the ordinary course of his existence, the uncivilized Tarahumare is too bashful and modest to enforce his matrimonial rights and privileges; and only by means of the national drink tesvino is the race kept alive and increasing."

Yet there was a place in their ceremony when formality and solemnity gave way to what the writer quoted above describes as "debauch." For this very drink of tesvino was an essential part of the worship. It was generously imbibed at the close of formal services, and, as the intoxicant was becoming effective, men and women entered into open promiscuous sexual relationship in which they engaged until well nigh dawn.

Without tesvino, religious worship could not dissolve the chains of sexual constraint for the Tarahumares. Among other primitive peoples, it also failed in this liberating function in at least one respect: incest. Promiscuous as the worshippers in the temple were, they still observed the taboo on incestuous relationship. Contact between parent and child persisted in the orgiastic rites of secret sects past and present, but it was banished from the temple of the gods. However, all other forms of sexual promiscuity as a feature of religious worship continued for many thousands of years.

Sacrifice is one element that early found its way into the worship of all gods. Its origin was humble indeed. It

may have been a bribe to a menacing god to stay his hand, a gift to a supernatural power to secure his favor, or a reward to an obliging divinity who did man's bidding. Again, it was sometimes just a fine for an act displeasing to the gods, imposed upon a person by his own guilty conscience. However it originated, the concept of sacrifice grew with the human mind. It gathered intellectual and emotional values as it rolled along the path of human progress.

As fear gave way to love in the heart of primitive man, and he came to adore his gods rather than to look upon them in dread and horror, sacrifice began to take on a devotional aspect. The dominant note became that of homage. Just as the lover enjoys bringing a gift to his love and is exalted by the very act of giving, so is the devotee happy to offer what is nearest and dearest to him to his god out of sheer love for the divinity.

In the worship of the generative divinities sacrifice also came to play its part. Here, perhaps even more than in the worship of other gods, it secured a hold upon the people to an overwhelming extent, more for what man got out of it directly than for what the gods might offer in return. For sacrifice in sex worship came to be another outlet for the collected sexual energies of man, diverted from their natural course through the numerous social inhibitions.

Although the sacrifice to the gods of generation was to be sexual, it could assume several different forms. It could be the product of the sexual union, the firstborn. Like the lover who brings his beloved a gift and is himself first treated to it by the grateful recipient, primitive man offered to the generative god the first gift of new life received through his influence. The firstborn was also

the thing man waited for so long, the object that was most precious to him. In many a corner of the world, the firstborn—whether crop or fruit or animal, not even excluding human—was sacrificed to the divine being. The Phœnicians offered the dearest child, the firstborn, to propitiate their god. In Exodus we read that "All that openeth the womb is mine," and in old Judea the firstborn was commonly considered an object for sacrifice. Even today the firstborn Jewish child, if it be a son, rightfully belongs to the descendant of the tribe of Levi, the priesthood of the temple. The father has to redeem the firstborn from the cohen. Thirty days after the birth, a ceremony is performed which is called "the redemption of the son" and in which the father gives the cohen anything of value. The latter receives it in lieu of the boy. After the transfer is made, there is a jolly party and a feast according to the means of the parents. In practically all cases the cohen returns the ransom before he leaves the house.

Just as the fruit of the sexual union was offered in sacrifice to the god of fertility, so did the agents in this process, that is, the organs of procreation, also become material for sacrifice. Both foreskin and hymen are the appropriate parts to be rendered to the divinity. The hymen is the guardian at the gateway of generation. Its presence is a sign that no generative services have as yet been brought by the female individual. It is destroyed in the very process so dear to the god of fertility. It is, therefore, sacred to the god and must be sacrificed at his altar.

The Roman bride offered her hymen directly to the god of generation, Priapus. To his temple she repaired with her parents and the groom. The latter waited in

the ante-room while the young maiden alone entered into the sacred chamber of the temple. There, in the representation hewn out of marble, was Priapus himself, a strong, nude male, in passion. The youthful bride embraced him in fear and trembling, and when she left the sacred chamber, she was a virgin no longer.

A similar custom prevails even today in some parts of India. A writer, who was long a sojourner there, relates: "Many a day have I sat at early dawn in the door of my tent, pitched in a sacred grove, and gazed at the little group of females stealthily emerge from the adjoining village, each with a garland or bunch of flowers, and when none were thought to see, accompany their prayer for pulee-pullum (child fruit) with a respectful abrasion of a certain part of their person on a phallus."

To the westerner, watching stealthily, it was, perhaps, a quaint, erotic scene. To the maidens about to enter matrimony, this was a solemn sacrifice of their hymen to the god within whose power it was to bless them with many births, assuring them of the love of their husbands, or to curse them with barrenness, causing them to be hated and despised.

Among very primitive peoples the god was personified in the ceremony, not by an inanimate object, but by his priest. In many places, this divine representative acted openly, even demanding a fee. Again, he played the part of the god under cover, in the dark of the night. So it was that some brides believed they had actually consorted with the divinity, while others realized, perhaps, that it was with the priest. But the priest here became impersonal. He was no longer a mere human but rather the divine representative upon earth. He played a rôle similar to

that of the modern priest when, as the confessor, he takes the place of Christ in forgiving the sins of the contrite penitent.

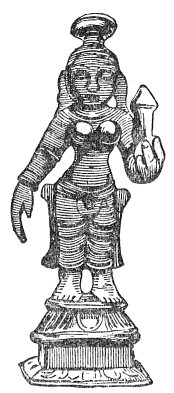

The custom of having the priest act as the representative of the god is practiced in India even at the present time. It is not uncommon for a husband to accompany his wife to the priest and to remain a reverential spectator of the

A Hindu goddess offering a lingam

act representing the union of god and woman. In certain parts of the country, there are definite days each year on which women call at the temples to receive from the priests the sacred blessing that they are unable to obtain from the god of creation through the medium of their husbands.

Where a king or lord assumed a theocratic function as was usual in ancient times, it was customary for him to

substitute for the god at this hymeneal sacrifice. In our own times, the Justice of the Peace claims the right to kiss the bride first. He is entirely ignorant of the fact that therein he merely claims a mild substitute for the first right to the bride that should be his according to ancient custom.

In the male, there is nothing to correspond to the hymen, which so symbolically represents the transition' from virginity to the realm of sex experience. Still, the foreskin is the nearest to it. Like the hymen, it undergoes a change in sexual intercourse. Again, like the hymen, it can be removed with pain, yet with little danger to the life of the individual. We thus have the circumcision operation at the time of puberty as the sacrifice of the male agent in the sexual process. This ceremony is performed among the Jews on the eighth day after birth; among the Arabs at the age of thirteen; but by other peoples in various parts of the world as a tribal rite of initiation corresponding to the modern confirmation ceremony.

The sacrificial meaning of both circumcision and hymeneal rupture becomes even more apparent in the perversions of some religious sects. Among those people who live religion very intensely and vividly, we find the true intent of the rite unmitigated by the consideration of individual well being and the interest of the group. We see it in the actual incisions in the female organs, such as removing the clitoris, or in the infibulation of the labia minora. We see it again in the castrations following great religious excitations in both ancient and modern times.

In the heat of religious passion, the avid worshippers of Cybele lost all sense of reality and ran about like mad men with furious eyes and streaming hair. At times they joined

in wild, fantastic dance amidst the cries and shouts of drunken song. Again, they broke up and rushed about through the woods, falling upon each other and flogging themselves relentlessly with iron chains. And all the time they carried burning torches or brandished sacred knives.

For hours the drunken, furious orgy went on and in the excitement of the dance, drink, and flogging, they forgot themselves completely. In the pain and frenzy of the approaching ecstasy, they thrust the knives upon their bodies in the name of the goddess. Unconscious of the resulting anguish, they continued their mad dance and waved about the severed portions of their bodies, while the blood streamed from the gaping wounds. When the fury had died away, they approached the altar to present their goddess with the spoils of their virility. They had made the great sacrifice for her and now they were to adopt woman's dress and serve her in the temple—eunuch priests.

As religion develops and love ever plays a larger part in it, the idea of sacrifice becomes more and more sacred, the sacrificial object ever growing in holiness. Hence, once the agents of the sexual process were offered in sacrifice to the generative divinity, it is only natural that they came to be looked upon as something sacred. When one took an oath in olden times and, as we do today, had to put his hand upon a sacred object, he placed it upon his genitals. When Abraham is stricken with age and desires his servant Eliezer, who is also the Elder of his household, to swear that he will take a wife for his son Isaac, not from the daughters of Canaan, but from Abraham's own people, he says:

"Put, I pray thee, thy hand under my thigh and I will make thee swear by the Lord, the God of heaven and the God of earth. . . ."

The thigh was a generic term for the organ of creation. In the Bible, one refers to his descendants as those "who came out of my thigh."

Travelers tell of a people whose priests on various occasions go about uncovered so that the worshippers of the generative divinity may pay the lingam the homage usually paid when sacred objects are exposed to the veneration of the pious. In Canara and other districts of India, the priests went about naked in the streets, ringing the bells that they held in their hands. It was to call out the women to the religious duty of piously embracing their sacred organs.

'The old idea of the sanctity of the lingam survives in the Christian attitude of reverence toward the Holy Prepuce, the foreskin of Jesus. Until very recently, there were twelve such prepuces extant in European churches, and many a legend was woven about them. One of these, the pride possession of the Abbey Church of Coulomb, in the diocese of Chartres, France, was believed to possess the miraculous power of rendering all sterile women fruitful. It had the added virtue of lessening the pains of childbirth.

Where the sanctity of the organs of generation had worn off, there still existed a certain attitude toward them—akin to sacred. The genitals were taboo. They were out of the range of usual experience, not to be touched or mentioned by name. The Mosaic law had no pity upon those who violated this taboo.

"When men strive together one with another, and the

wife of one draweth near to deliver her husband out of the hand of him that smiteth him, and putteth forth her hand and taketh him by the secrets, then thou shalt cut off her hand; thine eye shalt have no pity." The punishment was to be so severe because she had touched an object that was most taboo.

In many parts of the world, among savages, to uncover oneself before a person is to curse him. In Russia and other places in eastern Europe, one expresses spite or defiance by making a fist with the tip of the thumb extended between the index and the middle fingers. This is called a "fig" and is symbolic of the male genital. Although, when used as suggested, it may be very effective in producing the desired result, very few people are aware of its original significance. As late as the latter part of the eighteenth century, in Naples, this same figure was used as an amulet and worn to guard against the evil eye.

There was yet another sacrifice that man could offer to the god of generation—the sacrifice of coition. Just as he created his god in his own image, so did he bestow upon him that which he himself cherished most. Respectable old Herodotus was shocked to find that all people, with the exception of the Greeks and the Egyptians, cohabited within their temples.

In principle, the first sex experience was to be with the god himself. There was involved in it the sacrifice of the hymen as well as the first act of coition. In the absence of the god, his priest or temporal representative could fill his place. There were yet other surrogates, such as the stranger and the group as a whole.

In a world where the group is small, every one is known, and travelers are rare, a stranger becomes an oddity. His coming and going are veiled in mystery. So it was that he came to be looked upon as a divine emissary, a possible angel in the flesh. To the Jew of the Middle Ages, every stranger was a potential Elijah the prophet, in disguise. To the Christian, he was possibly the wandering Jew or a reincarnation of Christ or some saint. To the Easterner, the stranger was a sacred man, and that accounts for the famed hospitality of the Orient. The same halo hung about him already in primitive times. What was due to a god was frequently given to the stranger and what was expected from the divinity was looked for in the possible gift some passing traveler might bring.

No wonder, then, that the virgin coition was also to be performed with a stranger. We read of maidens, among primitive peoples, being brought to the altar of the generative goddess at least once before their nuptials, to be sacrificed to a stranger. This did not at all detract from their value in marriage. In fact, to this day a husband in the Kamerun has small opinion of his wife if she has had only limited sex experience before her marriage, for "if she were pretty men would have come to her."

Among the American Indians, when girls enter into womanhood, they are taken to a hut, painted, and made to cohabit with strangers while songs are offered to the. goddess Iteque. Similarly must the Santal girl, once in her life, cohabit with a stranger in the temple of Talkupi Ghat. And when we reach the stage of so-called temple prostitution, it is the stranger again who takes away the prettiest girl, the girl that is first to be initiated.

Not only the stranger, but the group as a unit may take

what rightfully belongs to the gods. A vestige of this attitude we have in the popular concept of vox populi vox dei—the voice of the people is the voice of god. We have it again in the unusual theological powers which a conclave of ministers will assume for themselves. A hundred rabbis will void a marriage vow against the rule for divorce. A church council will decide upon substantiation and the figure of the cross.

The tribe as a whole may delegate to itself the privilege that accrues only to the god. In Serang a maiden must herself provide the food for her wedding feast. Yet she has nothing with which to get it but her maidenhood. So she calls at the temple and there, after prayer and song, she is ceremoniously bathed and clothed in a skirt of fiber. Now she is at the service of every man until she has collected as much as she needs for the feast.

At the feast, a pot filled with water is covered with a leaf. An old woman takes the index finger of the girl's right hand and thrusts it through the leaf. This symbolizes the fact that her hymen has been broken. The leaf is then displayed on the ridge of the roof. It is a sign for the old men of the village that it is their night, and during that evening, they all have access to her room.

Herodotus tells us that among the people of Lydia, the bride, on her wedding night, accorded her favor to all the guests for which they, in return, presented her with gifts. Possibly our custom of wedding presents is a forgotten hang-over of such rewards to the bride for her amorous favors, just as our privilege of kissing her may be a mild form of another and more severe claim upon the newly wed maiden by all the members of the clan.

It was not only the first coition that became a sacrifice.

Any sexual union, if executed within the temple and under the auspices of the divinity, might be offered to the god of generation. Soon, any man, a lonesome stranger or a tired soul, weary with the burdens of life, could come to the temple to find escape from worldly troubles through the gateway of love. He had only to pay the god for the privilege of representing him, and the union in which he joined was then but another sacrifice of coition. Hence, we find the widespread custom of the duty upon every woman, at least once in her life, to come to the temple and to give herself to anyone for a donation to the god. Little did it matter how humble or how noble she might be; she must offer herself to the first bidder.

We are told by Herodotus that once in her lifetime every woman born in Chaldea had to enter the inclosure of the temple of Aphrodite, sit therein, and offer herself to a stranger. Many of the wealthy were too proud to mix with the rest and repaired to the temple in closed chariots, followed by numerous attendants. The greater number seated themselves in long lanes on the sacred pavement. The place was thronged with strangers passing down the lanes to make their choice. Once a woman had taken her place there, she could not return home until a stranger had thrown into her lap a silver coin and had led her away with him beyond the limits of the sacred enclosure. As he threw her the money, he pronounced the words: "May the goddess Mylitta make thee happy."

A similar custom prevailed among the American Indians. Among the ancient Algonquins and Iroquois as well as among some South American tribes, there was a festival during which the women of all ranks extended to .whosoever wished, the same privileges that the matrons of ancient

[paragraph continues] Babylon granted even to the slaves and strangers in . the temple of Mylitta. It was one of the duties of religion.

In the course of time, this custom passed out of existence. No longer could the group take the place of the god in the sacrament of sex. Yet it continued in a different form. What the group could not do as a whole with all the individuals participating in it, some individuals representing the group could still do for the god of generation. Instead of the entire group joining in promiscuous sexual union, certain individuals were selected by the group to execute the act on behalf of the entire assemblage.

In those temples in India where there is no general sexual union, there is still a ceremonial performance of coition by a chosen couple. It is carried out in a so-called "vacant enchanted place," which is rendered pure by sprinkling it with wine. Secret charms are whispered three times over the woman, following which the sexual act is consummated.

When Captain Cook visited one of the Pacific Islands, he and his party invited the natives to a religious ceremony. In return, the natives performed a rite of their own. After the usual Indian ritual, a tall, strong young man and a slight girl of about twelve stepped forward and, upon an improvised altar, joined in sexual union, the elder women advising and assisting the young girl in the performance of her amorous duty. The entire audience stood silent as they looked on in solemn reverence.

Various were the forms that the sexual sacrifice assumed in the temples of the gods. In one case, it may have been just the hymeneal offering of the first union in sex. In another, it may have been a union at any time during the life of the woman. In still another, the sacrifice was to be repeated annually, or every time a certain festival was

celebrated. These variations were effected by the religious institution itself, the priests, and the social traditions of the group.

Still other variations found their origin in the different attitudes of the individual women. One woman may have brought the single sacrifice more out of necessity than out of inner desire. To her, it may have been a painful

Click to enlarge

A Hindu god in copulation

duty of which she was glad that no more was required. To another woman, the one sacrifice may have left only greater desire for a repetition of the worship. In terms of our modern psychology, this distinction would be one of sexual sensibility and erotic propensities. To the primitive man, the distinction was in degree of piety. It was the extent to which one was devoted to the god and ready to serve him.

Five times a day the Azan is chanted on the balcony of

the minaret. It is the call to the faithful Moslem to wash his face, hands and feet, and bend down in prayer. North-light, meridian, and sunset are reminders to the Jew to "listen that the Lord is his God, the Lord is One." Morning, noon, and evening the Angelus bell tells over and over again to the faithful Christian the story of Christ's advent upon the earth and reminds him of the worship he owes his God.

There are those whose lives are merely intermissions between acts of worship. There are others whose worship is a rare and thin sprinkling over a secular existence. This was true in primitive times as it is today. There were women whose sexual sacrifice at the temple was an incident of small significance in their lives. There were other women who were devotees of the divinities, bent upon serving them continually. In time, such persons came to be the priestesses of the god and acquired as much dignity in the temple as the priests who performed the rites of worship. He who chanted the incantations or carried the idol was no more entitled to the dignity of the priesthood than she who honored the god in her own sentient flesh.

There were priestesses who devoted themselves entirely to the god, sleeping in the sacred chamber and never leaving the temple. Their lives were given wholly to the divine being. They offered themselves directly to him, foregoing all the joys of secular living. There were others who did not cohabit with the god directly, but with his representatives, the stranger, the passer-by, anyone who might call in the divine name. They were offering themselves in sexual sacrifice. The procreative god was served by the act of procreation performed in the temple. The priest partook of the sacrifice of the firstborn. The priestess partook

of the sacrifice of coition. In the latter we have the origin of the institution of temple priestesses, which has so shocked the prudes of later times.

The execution of the sexual union as a sacrifice to the gods gave rise to a very important and almost universal institution of pagan religion. We know it by the unsavory name of prostitution,—temple or religious prostitution. Perhaps it was unsavory at the time the Roman writers were preserving it from historical oblivion. Whatever we know of it, we owe to writers who belonged to a later culture and who looked at it adversely, if not with actual disgust; who saw it in its disintegrating, degenerating ugliness, when it was dying a shameful death.

In its inception, however, there was nothing degrading about it. To the primitive man, it was both honorable and pious. He looked at it in some such fashion as this:

Sexual union is a pious act pleasing to the gods. Every woman is enjoined by the god to sacrifice at least one such union in his honor. The god being divine and physically absent, a surrogate is necessary to receive the sacrifice. He may be a priest, a stranger, or a group. Whoever the surrogate is, he who is thus honored must himself bring an offering to the god; he must show his appreciation of this privilege by contributing his mite for the divine needs. In our own plain, prosaic words, we might say: he must pay for it. Now, let us remember: pay, not the woman, but the god for partaking of her sacrificial favor.

When the priest was the surrogate, no one was to inquire how he squared it with the god. Presumably, he repaid it in prayer and worship. Sometimes, it was the woman herself,

or her family, who provided the recompense which was due from the priest. Whenever the surrogate was not of the god's human family, that is, not of the priesthood, he contributed to the upkeep of the god's house in coin or in gift from field or forest.

When the man threw the coin to his choice of the women aligned at the temple and said: "May the goddess Mylitta make thee happy," he was not buying the woman's body. He was participating in a religious ceremony in which his share consisted not only in uniting with the woman but also in bringing an offering to the god—in this case, a monetary one, since the priests must live and the temple of the divine being must be kept up.

In fact, one may question the justice of applying to this institution the term "prostitution." By the latter we seek to signify a sexual union in which one of the partners fulfills his part for reward or material gain outside the field of sexuality. It is the motive that determines whether a sexual union is prostitutional or not. Certainly, the woman who came piously to the temple, waiting in prayerful mood to be chosen by anyone at all, be he ever so unattractive physically, and receiving for herself no monetary or material compensation,—certainly, this woman cannot be called a prostitute.

True, in its later development, this institution of sacrificial sexual union did assume a semblance of prostitution. As time went on, the temple priestesses easily outnumbered the priests. In some temples, there were as many as a thousand of them.

Our churches and synagogues are built in locations where they may be most eaqly accessible to the public. A modern house of worship will not disdain to advertise its services so

as to attract a greater number of worshippers. The pagan temples followed a similar course in their attempt to attract a large attendance. They were even more concerned with it, since the economic factor here played a greater rôle. The human family of the god was large and their material needs were considerable. In consequence, their temples were built on crossroads and, in cities with a port, not far distant from the docks. For it was the traveler, most in need of the sexual sacrifice, who was sure to call at the temple. It was he, too, that was to be favored, and in many cases, when a woman came to offer herself at the temple, she was to do so only to a stranger, as he was possibly a divine representative.

With so many priestesses and so many worshippers, the service had to become systematized, the fee or monetary sacrifice definitely fixed, and the share of the priestesses in the proceeds justly apportioned. No wonder, then, that to infidel eyes this looked more like a brothel than a house of worship. Did not any man call there, just as he calls on a legalized house of prostitution, pays the fee, and takes a woman in sexual embrace?

But the fact that the services of the temple priestesses had been so definitely systematized need not be deprecatory of the temple priesthood. System is a necessary feature in any large human institution, religious as well. Our worship today is only too well systematized. Nor need we be shocked by the payment offered for the services of the priestesses, since it was really the sacrifice of the male. The priestess offered her sexual function to the god, the man offered his coin. In fact, both were offering coin in addition to the sexual union, for the temple was receiving the payment from the male on account of the female. She

Click to enlarge

Venus in a phallic shrine

was as much a partner to the monetary contribution to the temple as she was a partner to the sexual intercourse.

Even her sharing the fee with the temple need not be surprising considered from the pagan viewpoint. When the farmer brought his first-born to the temple, it was sacrificed to the gods; yet, only a small part went to the god directly, that is, was burnt at the altar. The greater portion was returned to the donor and he was supposed to feast upon it in the temple court. And a goodly portion went to the priest. Just as the priest received his portion of the sacrificial lamb, so did the priestess receive her part of the fee for the sexual sacrifice. The one is no more prostitution than the other.

After all, the term prostitution is psychological in nature. There is nothing inherent in the physical union of the sexes to make one prostitutional and the other legitimate or respectable. It is the way in which society looks upon a sexual union and the way the partners feel about it that determines whether it is prostitutional or not. In those times and places where the institution of temple priestesses was established, society did not look upon it as prostitutional. Quite to the contrary, it was the most respectable and pious vocation a woman could select, or have selected for her by her parents or guardians. Nor did the temple priestess view herself as a prostitute. She saw herself a servant of the god, possibly bringing more joy and gladness to the divinity than to herself.

There were several paths by which a woman found her way to the temple priesthood. She may have come as a virgin to marry the god, where such marriages between

divinities and humans were performed. In this case, she was wedded to the god according to the rite of the tribe. After being initiated by the priests, she was the divine spouse and could, therefore, receive all his worshippers. The priests, in addition to consecrating her to her love-life, may have trained leer in the art of love. In proportion to her amorous talents, her fame and fortune grew to the extent that she was paid by lay married women for private instruction in the ars amandi.

Again, she may have come after her marriage, preferring the exalted erotic life in the temple to the cheerless existence of a primitive wife in servitude. In that case, she approached the divine dwelling-place, bearing upon her head some such gift as a cocoanut and a packet of sugar. She was received by the priest and given cakes and rice to eat. After her consecration, she was assigned to temple duty, such as sweeping and purifying the floor by washing it with cow-dung and water, and waving a fly-whisk before the god. In the meanwhile, she was instructed in the art of the sexual sacrifice by priest or priestess and, in time, she assumed her place before the god of generation.

More often, perhaps, she was brought to the temple by her father or brother, at an age when she was not yet old enough to have an opinion in the matter or to understand its significance. Her father may have had a guilty conscience; perhaps he had broken his marriage vow. He may have committed adultery, and the punishment for this would be visited upon the entire tribe. The tribe, in turn, would wreak its vengeance upon him. It were best to mend things before it was too late. So he took his female child, possibly not more than five years of age, and brought her to the temple in expiation. It was not much of a

sacrifice, girls being of little account anyway. In addition, it conferred an amount of distinction—one was somehow associated with the priesthood.

Occasionally, she got there by accident. Times were hard for the tribe; somehow the god or goddess was not pleased with the worship of the people. Then, a number of girls were collected and, en masse, admitted to the temple so that the divine frown might disappear. In another case, all may have been well with the tribe. Gods were pleased and man grateful. Once more, girls were consecrated to the divinity. Xenophon dedicated fifty courtesans to the Corinthian Venus, in pursuance of the vow he had made beseeching the goddess to give him victory in the Olympian games. Pindar makes Xenophon address the priestesses thus:

"O, young damsels, who receive all strangers and give them hospitality, priestesses of the goddess Pitho in the rich Corinth, it is you who, in causing the incense to burn before the image of Venus and in inviting the mother of love, often merit for us her celestial aid and procure for us the sweet moments which we taste on the luxurious couches where is gathered the delicate fruit of beauty."

However a girl came into the temple, she had a long period of training before her. This training was neither in religion nor in sex, but primarily in the graces of lovemaking and companionship. For the vocation of the temple priestess was complicated, indeed. She was catering not to the Western man, but to the man of the East whose loving was as refined as it was intricate.

To the Occidental man, love is either highly spiritual—romance and chivalry, or purely physical, mere sexual union. The prostitute of the West answers the call of his

physical love. She receives her guest in the dark and only for a brief moment. The man comes to her when his passion runs high; the minute the passion is spent he leaves. The Chinese or Indian prostitute is first of all a companion and an entertainer. She will delight her guests intellectually by conversation, or artistically by playing or singing; she may dance and she may serve tea. What follows is a relationship gradually drifted into, not an act bought and paid for.

The temple priestess is, therefore, trained for Oriental love-making. For ten hours each day these little girls are instructed in singing and dancing. From the age of seven or eight to fourteen or fifteen, they dance six times daily. They are taught, too, to acquire charm and poise and to make their bodies attractive through the use of fine clothes, sweet-scented powders, and delicate perfumes whose exotic fragrance enhance their allurement. Their minds are also trained and they become delightful conversationalists.

A pen picture of the priestess in action is offered us by Savarin: "The suppleness of their bodies is inconceivable. One is astonished at the mobility of their features, to which they give at will an impression agreeable to the part they play. Their indecent attitudes are often carried to excess. Their looks, gestures, all speak in such an expressive manner that it is not possible to misunderstand what they mean. At the commencement of the dance they throw aside, with their veils, the modesty of their sex. A long, very light silken robe descends to their heels enclosed by a rich girdle. Their long black hair floats in perfumed tresses over their shoulders; a gauze chemise, almost transparent, veils their breasts. To the measure of their movements, the

form and contours of their bodies are successively displayed. The sound of the flute, of the tambourine and cymbals, regulates their steps and hastens or slows their motions. They are full of love and passion; they appear intoxicated; they are Bacchantes in delirium; then they seem to forget all restraint and give themselves up to the disorder of their senses."

The sexual sacrifices by these priestesses were usually carried on in the ante-rooms of the temple but sometimes, also, outside, in the court or out buildings, or even along the banks of the sacred rivers. The price was always considerable. In India, in comparatively recent times the sacred fee was from ten to forty dollars, while the Nizam of Haldabad offered a thousand pounds sterling for three nights. Stories of Egypt and Greece indicate that the fee was considerable. King Cheops, impoverished, sacrificed his daughter to procure the necessary funds for the pyramid he was building. Flora, a priestess, was the benefactress of her town, erecting at her own expense a statue to the father of Croesus.

To what extent favors were highly paid for in antiquity may be gleaned from the following anecdote of a famous courtesan, Archidice. A young Egyptian became infatuated with her and offered her all his possessions for one night of love. Archidice disdained his offer. In despair, the lover besought Venus to give him in his dream what the beautiful Archidice refused him in reality. The prayer was answered and the young Egyptian had the dream he so much desired. When Archidice heard of it, she had the young man arrested and taken before the judges to make him pay for his voluptuous dream. The judges decided

that Archidice should, in turn, pray to Venus for a dream of silver in repayment for a fictitious lover.

In India, there were even wandering troupes of priestesses led by old women, former servants of the temple. Raynal describes their activity:

"To the monotonous and rapid sounds of the tom-tom these Bayaderes, warmed by a desire to please and by the odors with which they are perfumed, end by becoming beside themselves. Their dances are poetic pantomimes of love. The place, the design, the attitude, measure, sounds and cadences of these ballets, all breathe of passion and are expressive of voluptuousness and its fury.

"Everything conspires to the prodigious success of such women—art and the richness of ornament, the skill with which they make themselves beautiful. Long dark hair falling over their lovely shoulders or arranged in pretty tresses is loaded with sparkling jewels, glittering among natural flowers. Precious stones flash from their jewel-decked necklaces and tinkling bracelets. . . . The art of pleasure is the whole life occupation and only happiness of the Bayaderes. It is extremely difficult to resist their seductions."

The institution of temple priestesses was widely spread and quite extensively developed. Strabo said that there were as many as a thousand of them at the temple of Corinth. There were nigh twelve thousand such priestesses in Madras in quite recent times. There was not a country in which the institution was not present in some form. It was a natural development out of the sex worship which was universally followed. Beginning with a god of generation and reaching a stage of sexual sacrifice, a priesthood for the sacrifice was a natural and logical consequence.

There was another way in which man sought to tap divinity by his sexual emotion. To our eyes it would seem most unholy, as pitiable as it was unnatural. And yet it was there, exercised in all the piety and seriousness man is capable of. For not only did man create his gods in his own image but he also served them in his likeness. The man whose sex life was contrary to nature, set upon members of his own sex, served his generative god homosexually.

The Armenian father who brought his daughter to the temple of the goddess to be there consecrated as a priestess, often brought a son along as well. The son, too, was consecrated and his service was just as much a sexual sacrifice. The priest of Cybele who castrated himself in religious frenzy assumed feminine dress not without a purpose. He continued in the service of the temple and like the priestess served man for the required fee. There were male priests serving males in the temples of all the gods. The homosexual priest had a special designation in both the Hebrew and Babylonian languages. Kadosha was the name applied to the temple priestess engaged in sexual worship; kadosh was the word for the male in the same service.

In Tahiti, there were special divinities for homosexual worship. It was the god Chin himself who instituted homosexualism in Yucatan and sanctified it. His priests, therefore, wore feminine dress. What Chin was in the primitive world for the homosexual man, Mise, Pudicitia and Bona Dea were for the homosexual woman in antiquity. In these services artificial lingams were used by the women worshippers. There were divinities, like the Phrygian Cotytto, that were homosexually worshipped in some places

by men and in others by women. And at the service to Demeter at Pellene not only were men excluded but even male dogs so that there would be no disturbing element whatever for the rites to be performed.

Among the Santees, an American Indian tribe, if a man had a nightmare and dreamed of the terrible goddess, the moon, he had to appease the divinity by putting on feminine dress, serving as a woman and offering himself to men. In other tribes, the medicine men had to be effeminate and always wore the dress of women. In old Japan, according to Xavier, priests were to have sexual relations not with women but with men. Arabic travelling merchants reported, in the ninth century, that the Chinese resorted to pederasty in the worship of their icons. Leo Africanus tells of an order of women Satacat in northern Africa that served the gods in tribadistic fashion.

Even the gods resorted to homosexual practices. Zeus, their very father, came down from Mount Olympus attracted by a rosy-faced, bright-eyed youth. It was Ganymede, the most beautiful of mortals, whom the god, disguised as an eagle, seduced and carried away to the Mount. There, Ganymede became the object of love among the divinities for whom he acted as cup-bearer. And Zeus, to compensate the boy's father for the loss of his son, sent him a team of beautiful, light-footed horses.

The key to this strange way of serving a god must, as already indicated, be sought in the homosexual tendency that we find creeping up throughout the entire history of man. There were special lupanars for boys in Greece which were frequented by both men and women and were subject to the same tax and regulations as other lupanars. Dufour tells us that "Rome was filled" with male hierodules

Click to enlarge

Siva as the Hermaphroditic God, the eye in the center of his forehead symbolizing the union of the two creative forces

who "rented themselves out like the girls of the town. There were houses especially devoted to this kind of prostitution and there were procurers who followed no other business than that of renting out, for profit, a hoard of degraded slaves and even free men." Some of the greatest men of Rome, especially among the Cæsars, though not infrequently among the poets as well, were publicly known to be homosexual. They frequently gave themselves to men for gain—monetary or political. There seems to be no people on earth that did not know of this sexual relationship. In fact, it seems to have come down the animal line with man, for this very practice is found even among animals. It still is not uncommon. Less than a century ago, there were legalized brothels of men for homosexual practice in Paris just as there had been in Greece and Rome. The late Doctor Ivan Bloch described a ball of homosexuals in Berlin. There were some thousand of them; some in men's clothes, others in the dress of women, and still others in futuristic attire. At present, in America, homosexualism seems to be on the increase, especially in the artistic circles.

How did man come to prefer a member of his own sex to a person of the opposite one? This is a very interesting question but it need not concern us here. Suffice it to say that at first man's sexual nature is indefinite. It is a vague, blind yearning that has to be set to a person and to a sex, and that is conditioned by first associations and experience. There are environmental and social conditions that give man's instinct a homosexual turn. These obtained in the past as they still do today. That is why the homosexual tendency was ever present, running parallel with the so-called natural instinct.

Was homosexual worship merely a reflection of homosexual

living? Quite likely it was, although by a stretch of the imagination one may derive it in another way:

Originally the gods were hermaphroditic and were, therefore, worshipped by the union of the opposite sexes. As the hermaphroditic divinity separated itself into god and goddess, the worshippers, in some places, may also have separated by sexes, the male serving the god, the female the goddess. When members of one sex exclusively worship a generative god, their service is well in danger of becoming homosexual. Still, it seems more simple and doubtless more psychological to assume that homosexual man preceded the homosexual worshipper; and that even in homosexualism man only offered to his god what was dearest to him and all-embracing in his life.

. . . . . . .

On the shore of the island of Cyprus, in the waters of the Mediterranean, there once was a townlet called Amathonte. It lay well in the shade of Mount Olympus, yet it dared to defy the gods.

Its women were modest, reserved, contemptuous of all carnal pleasures. They covered their bodies and were disdainful of the flesh. One day, Venus was washed upon their shore. As the women came down to see her, they noticed her nudity and treated her with scorn. So when Venus came to her own, she descended to punish the women of Amathonte. She called them together and ordered them to prostitute themselves to all corners, so that they might glory in the very flesh they had so disdained. The women had no other recourse but to do as commanded by Venus. Still, they did it so reluctantly and with such distaste as to defeat the purpose of the goddess. Then Venus came down again and turned these women into stone.

And this was the end of the women of Amathonte, the women who denied the call of the flesh. They who feign would live were turned into stone while life went on. For in time, in this very city of Amathonte, a temple to Venus was erected, and other women came to live there, women who instead of denying love lived to worship it, who instead of rebelling against the flesh lived to triumph in it.

And amid the stones that once were women, the song of love was heard, love, natural, physical, permeating the

Click to enlarge

In the Temple of Siva

entire existence of mankind. And woman's rebellion against sex defeated its own purpose.

There was yet another revolt against sex—by man; and this is the story of Siva and his lingam:

Siva was a great god. With Brahma and Vishnu, he was master of the universe, his own function being generation and aiding new life to emerge out of death, like the

spring out of the arms of winter. It was Brahma himself who said: "Where is he who opposes Siva and yet is happy?"

But the great god Siva himself was not happy, for he was bereaved of his mate and he was tired and weary. So he wandered about the land and came to the forest of Daruvanam, where the sages live—the sages and their wives.

And when the sages came out to see the great god Siva and noticed that he was haggard and sad, they treated him with scorn and only saluted him with bent heads.

Siva was tired and weary and said nothing but: "Give me alms." Thus the god went about begging along the roads of Daruvanam. But wherever he came the womenfolk looked at him and felt a pang at the heart. At once their minds were perturbed and their hearts agitated by the pains of love. They forsook the beds of the sages and followed the great god Siva.

And as the sages saw their wives leaving with Siva, they pronounced a curse upon him:

"May his lingam fall to the ground."

Was it the effectiveness of the curse, or did Siva himself shed his lingam in affliction at the loss of his consort? Whatever the cause, there it was—his lingam—sticking into the ground and Siva himself gone.

As the lingam fell, it penetrated the lower worlds. Its length increased and its top towered above the heavens. The earth quaked and all there was upon it. The lingam became fire and caused conflagration wherever it penetrated. Neither god nor man could find peace or security.

So both Vishnu and Brahma came down to investigate and to save the universe. Brahma ascended to the heavens to ascertain the upper limits of Siva's lingam, and Vishnu

betook himself to the lower regions to discover its depth. Both returned with the news that the lingam was infinite: it was lower than the deep and higher than the heavens.

And the two great gods both paid homage to the

Click to enlarge

Siva leaning on the lingam

lingam and advised man to do likewise. They further counseled man to propitiate Parvati, the goddess, that she might receive the lingam into her yoni.

This was done and the world was saved. Mankind was taught that the lingam is not to be cursed or ignored; that it is infinite in its influence for good or evil; and that rather

than wishing it destroyed, they should worship it by offering it flowers and perfumes and by burning fires before it.

Whether it was the goddess Venus or the god Siva, whether it was the feminine principle or the masculine, the worship of the god or of the goddess came as a punishment for sex ignored. Love suppressed, offended, and imprisoned came to be rescued by the gods of religion.