Ancient Tales and Folk-lore of Japan, by Richard Gordon Smith, [1918], at sacred-texts.com

Click to enlarge

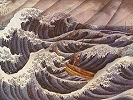

61. The Spirit of the Willow Tree Appears to Gobei

LVI

THE SPIRIT OF A WILLOW TREE SAVES FAMILY HONOUR

LONG ago there lived in Yamada village, Sarashina Gun, Shinano Province, one of the richest men in the northern part of Japan. For many generations the family had been rich, and at last the fortune descended in the eighty-third generation to Gobei Yuasa. The family had no title; but the people treated them almost with the respect due to a princely house. Even the boys in the street, who are not given to bestowing either compliments or titles of respect, bowed ceremoniously when they met Gobei Yuasa. Gobei was the soul of good-nature, sympathetic to all in trouble.

The riches which Gobei had inherited were mainly money and land, about which he worried himself very little; it would have been difficult to find a man who knew less and cared less about his affairs than Gobei. He spent his money freely, and when he came to think of accounts his easy nature let them all slide. His great pleasures were painting kakemono pictures, talking to his friends, and eating good things. He ordered his steward

not to worry him with unsatisfactory accounts of crops or any other disagreeable subjects. 'The destiny of man and his fate is arranged in Heaven,' said he. Gobei was quite celebrated as a painter, and could have made a considerable amount of money by selling his kakemonos; but no—that would not be doing credit to his ancestors and his name.

One day, while things were going from bad to worse, and Gobei was seated in his room painting, a friend came to gossip. He told Gobei that the village people were beginning to talk seriously about a spirit that had been seen by no fewer than three of them. At first they had laughed at the man who saw the ghost; the second man who saw it they were inclined not to take quite seriously; but now it had been seen by one of the village elders, and so there could be no doubt about it.

'Where do they see it?' asked Gobei.

'They say that it appears under your old willow tree between eleven and twelve o'clock at night—the tree that hangs some of its boughs out of your garden into the street.'

'That is odd,' remarked Gobei. 'I can remember hearing of no murder under that tree, nor even spirit connection with any of my ancestors; but there must be something if three of our villagers have seen it. Yet, again, where there is an old willow tree some one is sure to say, sooner or later, that he has seen a ghost. If there is a spirit there, I wonder whose it is? I should like to paint the ghost if I could see it, so as to leave it to my descendants as the last ominous sign on the road which has led to the family's ruin. That I shall make an effort

to do. This very evening I will sit up to watch for the thing.'

Never had Gobei been seized with such energy before. He dismissed his friend, and went to bed at four o'clock in the afternoon, so as to allow himself to be up at ten o'clock. At that hour his servant awoke him; but even then he could not be got up before eleven. By twelve o'clock, midnight, Gobei was at last out in his garden, hidden in bushes facing the willow. It was a bright night, and there was no sign of any ghost until after one o'clock, when clouds passed over the moon. Just when Gobei was thinking of going back to bed, he beheld, arising from the ground under the willow, a thin column of white smoke, which gradually assumed the form of a charming girl.

Gobei stared in astonishment and admiration. He had never thought that a ghost could be such a vision of beauty. Rather had he expected to see a white, wild-eyed, dishevelled old woman with protruding bones, the spectacle of whom would freeze his marrow and make his teeth clatter.

Gradually the beautiful figure approached Gobei, and hung its head, as if it wished to address him.

'Who and what are you?' cried Gobei. 'You seem too beautiful, to my mind, to be the spirit of one who is dead. If you are indeed spectral, do tell me, if you may, whose spirit you are and why you appear under this willow tree!'

'I am not the spirit or ghost of man, as you say,' answered the spirit, 'but the spirit of this willow tree.'

'Then why do you leave the tree now, as they tell

me you have done several times within the last ten days?'

'I am, as I say, the spirit of this willow, which was planted here in the twenty-first generation of your family. That is now about six centuries ago. I was planted to mark the place where your wise ancestor buried a treasure—twenty feet below the ground, and fifteen from my stem, facing east. There is a vast sum of gold in a strong iron chest hidden there. The money was buried to save your house when it was about to fall. Never hitherto has there been danger; but now, in your time, ruin has come, and it is for me to step forth and tell you how by the foresight of your ancestor you have been saved from disgracing the family name by bankruptcy. Pray dig the strong box up and save the name of your house. Begin as soon as you can, and be careful in future.'

Then she vanished.

Gobei returned to his house, scarcely believing it possible that such good luck had come to him as the spirit of the willow tree planted by his wise ancestor had said. He did not go to bed, however. He summoned a few of his most faithful servants, and at daybreak began digging. What excitement there was when at nineteen feet they struck the top of an iron chest! Gobei jumped with delight; and it may almost be said that his servants did the same, for to see their honoured master's name fall into the disgrace of bankruptcy would have caused many of them to disembowel themselves.

They tore and dug with all their might, until they had the huge and weighty case out of the hole. They broke off the top with pickaxes, and then Gobei saw a

collection of old sacks. He seized one of these; but the age of it was too great. It burst, and sent rolling out over a hundred immense old-fashioned oblong gold coins of ancient times, which must have been worth £30 each. Gobei Yuasa's hand shook. He could hardly realise as true the good fortune which had come to him. Bag after bag was pulled out, each containing a small fortune, until finally the bottom of the box was reached. Here was found a letter some six hundred years of age, saying:

'He of my descendants who is obliged to make use of the treasure to save our family reputation will read aloud and make known that this treasure has been buried by me, Fuji Yuasa, in the twenty-first generation of our family, so that in time of need or danger a future generation will be able to fall back upon it and save the family name. He whose great misfortune necessitates the use of the treasure must say: "Greatly do I repent the folly that has brought the affairs of our family so low, and necessitated the assistance of an early ancestor. I can only repay such by diligent attention to my household affairs, and also show high appreciation and give kindness to the willow tree which has so long been watching and guarding my ancestor's treasure. These things I vow to do. I shall reform entirely."'

Gobei Yuasa read this out to his servants and to his friends. He became a man of energy. His lands and farms were properly taken care of, and the Yuasa family regained its influential position.

Gobei painted a kakemono of the spirit of the willow tree as he had seen her, and this he kept in his own room during the rest of his life. It is the famous painting, in

the Yuasa Gardens to-day, which is called 'The Willow Ghost,' and perhaps it is the model from which most of the willow-tree-ghost paintings have sprung.

Gobei fenced in the famous willow tree, and attended to it himself; as did those who followed him.