Allan Antliff

Adrian Blackwell’s Anarchitecture: The Anarchist Tension

2010

In anarchist political activism, social structures are autonomous from, yet intimately related to, our agency. Society’s betterment is conceived as a collective process of self-actualization wherein individual freedom and social freedom are contiguous: anarchism’s potential is realized in the social trace of its own immanence. But that trace asserts itself in the face of formidable opposition. Given that existing societies are so antithetical to anarchist values, anarchism necessarily provokes antagonism, conflict, and challenge alongside pre-figurations of freedom as a sensuous reality. These are the politics of artist-architect Adrian Blackwell, who has been active for some time combating the forces of gentrification in Canada’s largest city, Toronto. In the course of this struggle, Blackwell has developed the antagonistic aspect of anarchist aesthetics by creating zones of tension enacted in the spaces between art and architecture.

In the first instance, this has been his means of overcoming forces of alienation in the architectural profession. Blackwell argues that the production of architecture is “highly mediated [...] within the collaborative yet hierarchical structure of a firm” while art is “generated in a context that is proximate to the everyday lives of its producers” (Blackwell, 2005: 78). Architects build the environments we live in, but the creative freedom of the architect is systemically constrained. How, then, can one radicalize the social potential of architecture? Blackwell’s solution has been to incorporate architectural concerns into art-making, prefiguring anarchic social relationships in the guise of art that takes aim at the popular culture of capitalist gentrification and the social relations marked out in the urban spaces it creates (ibid.).

What is the popular perception of gentrification in Canada and the United States? The term was first coined by British sociologist Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe the transformation of a neighbourhood shaped by a less well-off class to suit another more affluent one. For Glass, gentrification was a predatory social process with a multitude of negative impacts, however, as the decades passed it began to lose its critical bite, at least in North America. Here, where the institution of private property is routinely treated as the structural foundation of civic development, gentrification was naturalized as a positive, politically neutral process of urban revitalization that removes “the stain of poverty” while physically improving the cityscape (Blackwell, 2006: 30). In his political study of the contemporary urban public sphere, American social theorist Jeff Ferrell has pinpointed the rhetorical features of civic uplift through gentrification as deployed by developers, civic officials, and law enforcement. Gentrification cleans up “‘quality of life’ crimes” and solves the unpleasantries of poverty and homelessness by forcing the poor to leave. Out of sight, out of mind, so to speak (Ferrell, 2001: 15).

In late September 1998, after considerable negotiations with city administrators and local businesses, Blackwell installed a portable toilet near the corner of Queen and Spadina in Toronto’s downtown (Blackwell, 2004: 306). The installation was pitched as part of an off-site exhibition organized by an artist-run gallery and Blackwell committed himself to servicing and cleaning the toilet for a month. Prior to installation, he modified the toilet by replacing the door with a two-way mirror. The mirror allowed the casual round of toilet users to watch the street, creating possibilities for play and voyeurism.

At the time the Conservative government of Ontario had passed a “Safe Streets Act” empowering police to criminalize the survival strategies of homeless people. Gentrification was intensifying under the auspices of Toronto’s city hall, which was promoting condominium development in the downtown core. As part of the effort, Toronto police were given increased funding for overtime and a mandate to clear the homeless from public areas (ibid.). Government and private developers found common cause in the popularization of a familiar gentrification equation: poor people = danger. Blackwell installed his toilet adjacent to a busy corner where street people cleaned car windows for money. Local businesses had been agitating for the corner to be cleared, and one of their strategies was to deny access to washrooms.

This was an intervention on the side of the window cleaners, providing a much needed public service to those being discriminated against. In the process, systemic segregation along class lines and the imposition of proprietor rights on the public sphere was successfully disrupted. Use of the toilet also provided respite from intensified police surveillance mandated by the Ontario government and Toronto city council “in the name of the public good” (ibid., 307). In effect, every time a street person used the toilet the watched became the watcher, a reversal of perspective that went hand in hand with Blackwell’s provocative push-back against social harassment at the behest of business interests.

In the late 1990s, Toronto’s planning department announced a competition to design a new public square at the corner of Younge and Dundas Streets in the heart of the downtown. Brown and Storey Architects invited Blackwell to help develop a proposal, but he pulled out once he realized their plans were at odds with his own. The firm went on to win a place in the competition, and eventually secured the commission, giving us the square as it exists today (Blackwell, 2008: 86). The square was a classic exercise in gentrification, promoted as a festive, business-friendly space, tightly-managed and packaged for rental purposes. Accordingly, Brown and Storey designed a square that serves the needs of commerce. A prominent electronic billboard bombarded the public with advertizing and architectural features were introduced to channel traffic flow between shopping destinations. The plaza was conceived as a stage for corporate-backed promotional events, replete with water jets for crowd management.

Blackwell walked away from the privatization of Dundas Square, but he refused to abandon the public space being colonized. Instead, he created his own alternative design, which he presented at a public event celebrating the competition’s winning entries. The proposal was inspired by the spaces of civic discourse in ancient Greece — the market place, called the agora, and the focused amphitheater (Blackwell, 2003b: 308).

It took the form of a spiralling platform that gently descends towards a large open area in the centre. A balcony and bleachers provide alternative ways to experience the space which can be entered from multiple directions. The aesthetics are porous, open to the whims of the public (Blackwell, 2008: 86). Following the privatizing logic of gentrification, the planning commission’s square was intended to mirror the commercial vocabulary of its surroundings; and this is precisely what Blackwell rejected. In accord with the anarchist insight that diversity, disorder and unpredictability are inescapable facets of social freedom, his square is free of any ideological manipulation, notably the advertising tower that figured so prominently in the winning plan. Blackwell’s proposal fostered antagonism between a space for discussion and debate and the commercialized environment surrounding it. The design welcomed demonstrations and other manifestations of political conflict because it refused to impose a hegemonic notion of community on civic life. Accommodating “the diversity and friction which democracy requires” the proposal encouraged “freedom of action” that exceeds any boundaries set down by civic or state authorities (Blackwell, 1998a). Anarchy was flagrantly and overtly celebrated. “Playing with fire, eating outside, telling a lie, kissing on concrete, walking a line, fighting the power, loving a stranger” — in a civic space autonomous from regulation, the possibilities could and should be endless (Blackwell, 1998b). Blackwell exposed the Dundas Square competition as a gentrifying exercise intent on commercializing the public sphere and managing it.

Occasionally, life imitates art. In 2008, the city employee in charge of Dundas Square’s development was appointed Toronto Chief Planner. Meeting with a newspaper reporter for a photo op, he was chased off his own square by an “events manager” who brought along a security guard. They were told that “doing anything on the square” required a permit. A pizza company was setting up to hand out free slices, so they had to move on. Civic rhetoric aside, the reporter concluded, “what we have [at Dundas and Younge] is a private square run by a board of management that rents it for corporate events” (Anonymous, 2009).

In the wake of his Dundas Square intervention, Blackwell decided to distill his proposal’s anarchic features in ideal form, as a sculpture designed for public use. Model for a Public Space was completed in 1999 and has been exhibited in a number of galleries and outdoor civic settings. The model is composed of concentric bleachers about twenty-five feet in diameter. The ring starts at ground level and rises to a height of seven feet before spiralling gradually downward into the centre. This sculpture was inspired by anarchist decision-making processes in which participants form a circle so as to engage with each other face to face. The model is designed to accommodate a larger group of people than a standard circle. Variations in elevation create conditions for playing with the dynamics of implied hierarchies that offset each other. Power relations are symbolically situated and made fluid in the process. Who is more commanding, a person closer to the centre or a person higher up on the periphery? (Blackwell, 2008: 87).

In 2000, in the midst of Toronto’s development frenzy, Blackwell exhibited Model for a Public Space at the Lisgar Street location of Mercer Union, one of the city’s oldest artist-run galleries (est., 1979). Buildings in the area were being converted at a rapid pace into condominiums and upscale locations for high tech companies. Around the corner from the gallery, real estate developers had set up show rooms and stage apartments to lure buyers. While Model for a Public Space was on exhibit, Blackwell organized several open forums in which local residents discussed the social problems arising from gentrification and the lack of affordable housing in the immediate neighbourhood (Osborne, 2000: 26–7). A social sculpture of antagonism and agitation pitted the civic freedoms of artists, wage earners, and people on welfare against capitalized urbanism for the affluent.

Blackwell himself was homeless when he installed Model for a Public Space. He had been living in a former factory located at 9 Hanna Avenue in which occupants built their own studio units, complete with plumbing and other amenities. A Fiber-Optics company had bought the building site and on March 31st, the occupants were given 30 days notice to get out.

9 Hanna was more than a home. The makeshift interior included an immense central area that had been used for a host of activist projects over the years, including banner-making. The studios housed many artists, and the creative work that had gone into them was extensive. “What I loved about 9 Hanna,” Blackwell recalls, “is that you could make things in it. It had two features that made it ideal: affordable, well-lit [studio] units and large open spaces inside the building where it was possible to make a mess and build larger things. It was a functional utopian space” (2005: 88).[1] The building was political and it was social. It was functional and it was unique. It deserved to be commemorated.

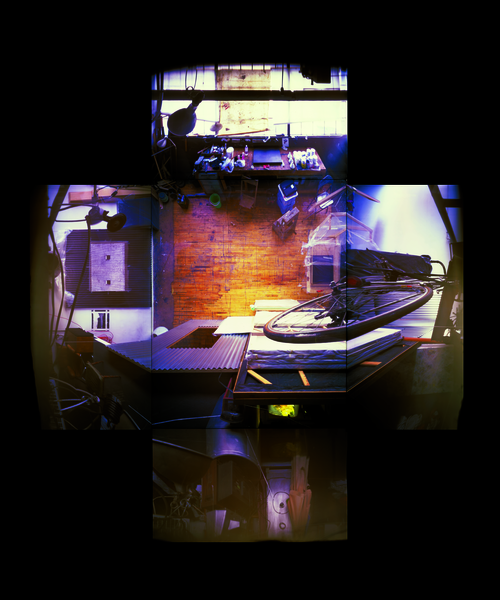

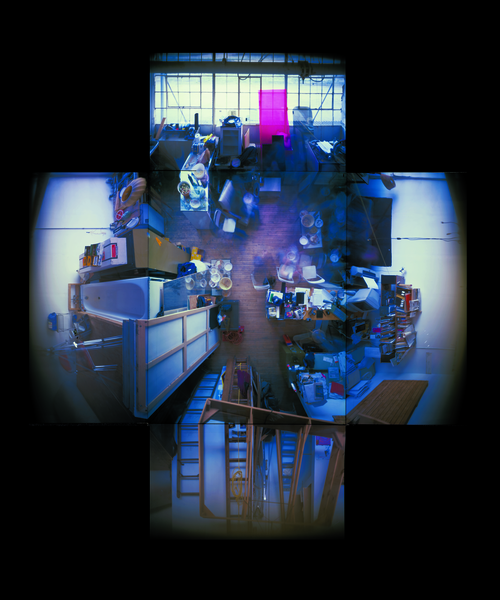

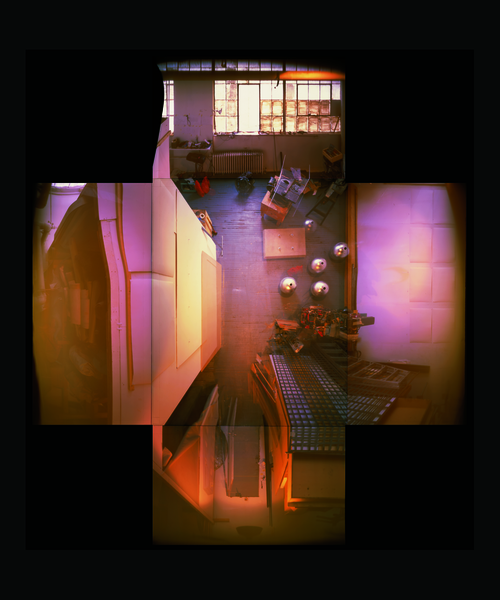

With eviction pending, Blackwell documented thirteen artists’ studios using a pinhole camera. Each photograph in the series, titled Evicted May 1st, 2000 9 Hanna, records the individualized features of these spaces. The units had been built and adapted to suit the needs of those who lived and worked in them. No studio was exactly the same as the next and they varied in size according to the amount of floor space occupied. Blackwell has argued such “ideal generic spaces” are antithetical to the money-making conceptions of condo developers, who destroy the possibility of “autonomous creative production” every time they shut down a low-rent building to make way for upscale lifestyle living (ibid., 88–9). His series reclaims the activism of these spaces, where modes of living were freely configured to serve the desires of the inhabitants. These open architectural creations, photographically aestheticized, project an anarchic oppositional power, a threat by example that could not be left alone, targeted and Evicted by the economics of capitalism. The radically reflexive art of Blackwell attacks, in the first instance, forces that undermine the possibility of a better, more humane world. His work configures anarchist aesthetics as an exercise in immanence by appealing to us as potential accomplices in the social tensions that anarchy in art cultivates through its refusal to closet itself within the confines of capitalism’s cultural institutions. This aesthetic of tension is constantly searching for avenues that break out of alienation, transparencies that bridge the gap between artist and audience, ruptures that draw us into contested social ground, where we discover our own freedom.

References

Anonymous. (2008) “Letter from Younge-Dundas Square: Designing for the Public,” National Post (May 6). As Retrieved on March 2nd, 2009 from network.nationalpost.com

Blackwell, Adrian. (2006) “The Gentrification of Gentrification and other Strategies of Toronto’s Creative Class,” Fuse (29)1.

— . (2005) “Lecture: October 21, 2002,” Unboxed: Engagements in Social Space (Jen Budney & Adrian Blackwell, Eds.). Ottawa: Gallery 103.

— . (2003a) “Public Water Closet,” Only a Beginning: An Anarchist Anthology (Allan Antliff, Ed.). Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

— . (2003b) “Model for a Public Space,” Only a Beginning: An Anarchist Anthology (Allan Antliff, Ed.). Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press.

— . (1998a) “Unofficial Entry to the Dundas Square Competition,” panel two.

— . (1998b) “Unofficial Entry to the Dundas Square Competition,” panel three.

Ferrell, Jeff. (2001) Tearing Down the Streets: Adventures in Urban Anarchy. New York: Palgrave.

Osborne, Catherine. (2000) “Silicon Alley North/Liberty Street Village in the Year 2005,” Mix (2)26.

[1] He continues, “By contrast, the condominium loft is primarily concerned with consumption. It short-circuits all the productive possibilities embedded in the studio. For that reason I see the condo craze in Toronto and the gentrification of low rent studio buildings as an attack on the possibility of producing a world of autonomous creative producers.”