RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"Clementina," Methuen & Co., London, 1901

The landlord, the lady, and Mr. Charles Wogan were all three, it seemed, in luck's way that September morning of the year 1719. Wogan was not surprised, his luck for the moment was altogether in, so that even when his horse stumbled and went lame at a desolate part of the road from Florence to Bologna, he had no doubt but that somehow fortune would serve him. His horse stepped gingerly on for a few yards, stopped, and looked round at his master. Wogan and his horse were on the best of terms. "Is it so bad as that?" said he, and dismounting he gently felt the strained leg. Then he took the bridle in his hand and walked forward, whistling as he walked.

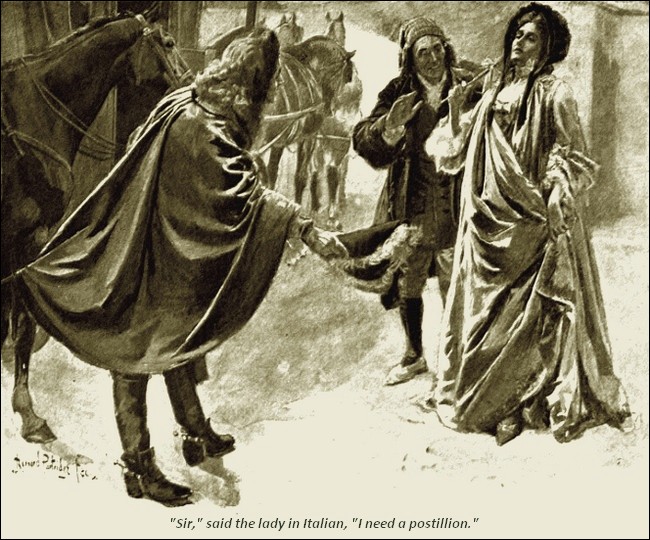

Yet the place and the hour were most unlikely to give him succour. It was early morning, and he walked across an empty basin of the hills. The sun was not visible, though the upper air was golden and the green peaks of the hills rosy. The basin itself was filled with a broad uncoloured light, and lay naked to it and extraordinarily still. There were as yet no shadows; the road rose and dipped across low ridges of turf, a ribbon of dead and unillumined white; and the grass at any distance from the road had the darkness of peat. He led his horse forward for perhaps a mile, and then turning a corner by a knot of trees came unexpectedly upon a wayside inn. In front of the inn stood a travelling carriage with its team of horses. The backs of the horses smoked, and the candles of the lamps were still burning in the broad daylight. Mr. Wogan quickened his pace. He would beg a seat on the box to the next posting stage. Fortune had served him. As he came near he heard from the interior of the inn a woman's voice, not unmusical so much as shrill with impatience, which perpetually ordered and protested. As he came nearer he heard a man's voice obsequiously answering the protests, and as the sound of his footsteps rang in front of the inn both voices immediately stopped. The door was flung hastily open, and the landlord and the lady ran out onto the road.

"Sir," said the lady in Italian, "I need a postillion."

To Wogan's thinking she needed much more than a postillion. She needed certainly a retinue of servants. He was not quite sure that she did not need a nurse, for she was a creature of an exquisite fragility, with the pouting face of a child, and the childishness was exaggerated by a great muslin bow she wore"Sir," said the lady in Italian, "I need a postillion." at her throat. Her pale hair, where it showed beneath her hood, was fine as silk and as glossy; her eyes had the colour of an Italian sky at noon, and her cheeks the delicate tinge of a carnation. The many laces and ribbons, knotted about her dress in a manner most mysterious to Wogan, added to her gossamer appearance; and, in a word, she seemed to him something too flowerlike for the world's rough usage.

"I must have a postillion," she continued.

"Presently, madam," said the landlord, smiling with all a Tuscan peasant's desire to please. "In a minute. In less than a minute."

He looked complacently about him as though at any moment now a crop of postillions might be expected to flower by the roadside. The lady turned from him with a stamp of the foot and saw that Wogan was curiously regarding her carriage. A boy stood at the horses' heads, but his dress and sleepy face showed that he had not been half an hour out of bed, and there was no one else. Wogan was wondering how in the world she had travelled as far as this inn. The lady explained.

"The postillion who drove me from Florence was drunk—oh, but drunk! He rolled off his horse just here, opposite the door. See, I beat him," and she raised the beribboned handle of a toy- like cane. "But it was no use. I broke my cane over his back, but he would not get up. He crawled into the passage where he lies."

Wogan had some ado not to smile. Neither the cane nor the hand which wielded it would be likely to interfere even with a sober man's slumbers.

"And I must reach Bologna to-day," she cried in an extreme agitation. "It is of the last importance."

"Fortune is kind to us both, madam," said Wogan, with a bow. "My horse is lamed, as you see. I will be your charioteer, for I too am in a desperate hurry to reach Bologna."

Immediately the lady drew back.

"Oh!" she said with a start, looking at Wogan.

Wogan looked at her.

"Ah!" said he, thoughtfully.

They eyed each other for a moment, each silently speculating what the other was doing alone at this hour and in such a haste to reach Bologna.

"You are English?" she said with a great deal of unconcern, and she asked in English. That she was English, Wogan already knew from her accent. His Italian, however, was more than passable, and he was a wary man by nature as well as by some ten years' training in a service where wariness was the first need, though it was seldom acquired. He could have answered "No" quite truthfully, being Irish. He preferred to answer her in Italian as though he had not understood.

"I beg your pardon. Yes, I will drive you to Bologna if the landlord will swear to look after my horse." And he was very precise in his directions.

The landlord swore very readily. His anxiety to be rid of his vociferous guest and to get back to bed was extreme. Wogan climbed into the postillion's saddle, describing the while such remedies as he desired to be applied to the sprained leg.

"The horse is a favourite?" asked the lady.

"Madam," said Wogan, with a laugh, "I would not lose that horse for all the world, for the woman I shall marry will ride on it into my city of dreams."

The lady stared, as she well might. She hesitated with her foot upon the step.

"Is he sober?" she asked of the landlord.

"Madam," said the landlord, unabashed, "in this district he is nicknamed the water drinker."

"You know him, then? He is Italian?"

"He is more. He is of Tuscany."

The landlord had never seen Wogan in his life before, but the lady seemed to wish some assurance on the point, so he gave it. He shut the carriage door, and Wogan cracked his whip.

The postillion's desires were of a piece with the lady's. They raced across the valley, and as they climbed the slope beyond, the sun came over the crests. One moment the dew upon the grass was like raindrops, the next it shone like polished jewels. The postillion shouted a welcome to the sun, and the lady proceeded to breakfast in her carriage. Wogan had to snatch a meal as best he could while the horses were changed at the posting stage. The lady would not wait, and Wogan for his part was used to a light fare. He drove into Bologna that afternoon.

The lady put her head from the window and called out the name of a street. Her postillion, however, paid no heed: he seemed suddenly to have grown deaf; he whipped up his horses, shouted encouragements to them and warnings to the pedestrians on the roads. The carriage rocked round corners and bounced over the uneven stones. Wogan had clean forgotten the fragility of the traveller within. He saw men going busily about, talking in groups and standing alone, and all with consternation upon their faces. The quiet streets were alive with them. Something had happened that day in Bologna,—some catastrophe. Or news had come that day,—bad news. Wogan did not stop to inquire. He drove at a gallop straight to a long white house which fronted the street. The green latticed shutters were closed against the sun, but there were servants about the doorway, and in their aspect, too, there was something of disorder. Wogan called to one of them, jumped down from his saddle, and ran through the open doorway into a great hall with frescoed walls all ruined by neglect. At the back of the hall a marble staircase, guarded by a pair of marble lions, ran up to a landing and divided. Wogan set foot on the staircase and heard an exclamation of surprise. He looked up. A burly, good-humoured man in the gay embroideries of a courtier was descending towards him.

"You?" cried the courtier. "Already?" and then laughed. He was the only man whom Wogan had seen laugh since he drove into Bologna, and he drew a great breath of hope.

"Then nothing has happened, Whittington? There is no bad news?"

"There is news so bad, my friend, that you might have jogged here on a mule and still have lost no time. Your hurry is clean wasted," answered Whittington.

Wogan ran past him up the stairs, and so left the hall and the open doorway clear. Whittington looked now straight through the doorway, and saw the carriage and the lady on the point of stepping down onto the kerb. His face assumed a look of extreme surprise. Then he glanced up the staircase after Wogan and laughed as though the conjunction of the lady and Mr. Wogan was a rare piece of amusement. Mr. Wogan did not hear the laugh, but the lady did. She raised her head, and at the same moment the courtier came across the hall to meet her. As soon as he had come close, "Harry," said she, and gave him her hand.

He bent over it and kissed it, and there was more than courtesy in the warmth of the kiss.

"But I'm glad you've come. I did not look for you for another week," he said in a low voice. He did not, however, offer to help her to alight.

"This is your lodging?" she asked.

"No," said he, "the King's;" and the woman shrank suddenly back amongst her cushions. In a moment, however, her face was again at the door.

"Then who was he,—my postillion?"

"Your postillion?" asked Whittington, glancing at the servant who held the horses.

"Yes, the tall man who looked as if he should have been a scholar and had twisted himself all awry into a soldier. You must have passed him in the hall."

Whittington stared at her. Then he burst again into a laugh.

"Your postillion, was he? That's the oddest thing," and he lowered his voice. "Your postillion was Mr. Charles Wogan, who comes from Rome post-haste with the Pope's procuration for the marriage. You have helped him on his way, it seems. Here's a good beginning, to be sure."

The lady uttered a little cry of anger, and her face hardened out of all its softness. She clenched her fists viciously, and her blue eyes grew cold and dangerous as steel. At this moment she hardly looked the delicate flower she had appeared to Wogan's fancy.

"But you need not blame yourself," said Whittington, and he lowered his head to a level with hers. "All the procurations in Christendom will not marry James Stuart to Clementina Sobieski."

"She has not come, then?"

"No, nor will she come. There is news to-day. Lean back from the window, and I will tell you. She has been arrested at Innsbruck."

The lady could not repress a crow of delight.

"Hush," said Whittington. Then he withdrew his head and resumed in his ordinary voice, "I have hired a house for your Ladyship, which I trust will be found convenient. My servant will drive you thither."

He summoned his servant from the group of footmen about the entrance, gave him his orders, bowed to the ground, and twisting his cane sauntered idly down the street.

Wogan mounted the stairs, not daring to speculate upon the nature of the bad news. But his face was pale beneath its sunburn, and his hand trembled on the balustrade; for he knew—in his heart he knew. There could be only one piece of news which would make his haste or tardiness matters of no account.

Both branches of the stairs ran up to a common landing, and in the wall facing him, midway between the two stairheads, was a great door of tulip wood. An usher stood by the door, and at Wogan's approach opened it. Wogan, however, signed to him to be silent. He wished to hear, not to speak, and so he slipped into the room unannounced. The door was closed silently behind him, and at once he was surprised by the remarkable silence, almost a cessation of life it seemed, in a room which was quite full. Wherever the broad bars of sunshine fell, as they slanted dusty with motes through the open lattices of the shutters, they striped a woman's dress or a man's velvet coat. Yet if anyone shuffled a foot or allowed a petticoat to rustle, that person glanced on each side guiltily. A group of people were gathered in front of the doorway. Their backs were towards Wogan, and they were looking towards the centre of the room. Wogan raised himself on his toes and looked that way too. Having looked he sank down again, aware at once that he had travelled of late a long way in a little time, and that he was intolerably tired. For that one glance was enough to deprive him of his last possibility of doubt. He had seen the Chevalier de St. George, his King, sitting apart in a little open space, and over against him a short squarish man, dusty as Wogan himself, who stood and sullenly waited. It was Sir John Hay, the man who had been sent to fetch the Princess Clementina privately to Bologna, and here he now was back at Bologna and alone.

Wogan had counted much upon this marriage, more indeed than any of his comrades. It was to be the first step of the pedestal in the building up of a throne. It was to establish in Europe a party for James Stuart as strong as the party of Hanover. But so much was known to everyone in that room; to Wogan the marriage meant more. For even while he found himself muttering over and over with dry lips, as white and exhausted he leaned against the door, Clementina's qualifications,—"Daughter of the King of Poland, cousin to the Emperor and to the King of Portugal, niece to the Electors of Trèves,* Bavaria, and Palatine,"—the image of the girl herself rose up before his eyes and struck her titles from his thoughts. She was the chosen woman, chosen by him out of all Europe—and lost by John Hay!

[* Trèves: now Trier, Germany. ]

He remembered very clearly at that moment his first meeting with her. He had travelled from court to court in search of the fitting wife, and had come at last to the palace at Ohlau* in Silesia. It was in the dusk of the evening, and as he was ushered into the great stone hall, hung about and carpeted with barbaric skins, he had seen standing by the blazing wood fire in the huge chimney a girl in a riding dress. She raised her head, and the firelight struck upwards on her face, adding a warmth to its bright colours and a dancing light to the depths of her dark eyes. Her hair was drawn backwards from her forehead, and the frank, sweet face revealed to him from the broad forehead to the rounded chin told him that here was one who joined to a royal dignity the simple nature of a peasant girl who works in the fields and knows more of animals than of mankind. Wogan was back again in that stone hall when the voice of the Chevalier with its strong French accent broke in upon his vision.

[* Ohlau: now Olawa, Poland. ]

"Well, we will hear the story. Well, you left Ohlau with the Princess and her mother and a mile-long train of servants in spite of my commands of secrecy."

There was more anger and less despondency than was often heard in his voice. Wogan raised himself again on tiptoes and noticed that the Chevalier's face was flushed and his eyes bright with wrath.

"Sir," pleaded Hay, "the Princess's mother would not abate a man."

"Well, you reached Ratisbon.* And there?"

[* Ratisbon: now Regensburg. ]

"There the English minister came forward from the town to flout us with an address of welcome in which he used not our incognitos but our true names."

"From Ratisbon then no doubt you hurried? Since you were discovered, you shed your retinue and hurried?"

"Sir, we hurried—to Augsburg," faltered Hay. He stopped, and then in a burst of desperation he said, "At Augsburg we stayed eight days."

"Eight days?"

There was a stir throughout the room; a murmur began and ceased. Wogan wiped his forehead and crushed his handkerchief into a hard ball in his palm. It seemed to him that here in this room he could see the Princess Clementina's face flushed with the humiliation of that loitering.

"And why eight days in Augsburg?"

"The Princess's mother would have her jewels reset. Augsburg is famous for its jewellers," stammered Hay.

The murmur rose again; it became almost a cry of stupefaction. The Chevalier sprang from his chair. "Her jewels reset!" he said. He repeated the words in bewilderment. "Her jewels reset!" Then he dropped again into his seat.

"I lose a wife, gentlemen, and very likely a kingdom too, so that a lady may have her jewels reset at Augsburg, where, to be sure, there are famous jewellers."

His glance, wandering in a dazed way about the room, settled again on Hay. He stamped his foot on the ground in a feverish irritation.

"And those eight days gave just the time for a courier from the Emperor at Vienna to pass you on the road and not press his horse. One should be glad of that. It would have been a pity had the courier killed his horse. Oh, I can fashion the rest of the story for myself. You trailed on to Innsbruck, where the Governor marched out with a troop and herded you in. They let you go, however. No doubt they bade you hurry back to me."

"Sir, I did hurry," said Hay, who was now in a pitiable confusion. "I travelled hither without rest."

The anger waned in the Chevalier's eyes as he heard the plea, and a great dejection crept over his face.

"Yes, you would do that," said he. "That would be the time for you to hurry with a pigeon's swiftness so that your King might taste his bitter news not a minute later than need be. And what said she upon her arrest?"

"The Princess's mother?" asked Hay, barely aware of what he said.

"No. Her Highness, the Princess Clementina. What said she?"

"Sir, she covered her face with her hands for perhaps the space of a minute. Then she leaned forward to the Governor, who stood by her carriage, and cried, 'Shut four walls about me quick! I could sink into the earth for shame.'"

Wogan in those words heard her voice as clearly as he saw her face and the dry lips between which the voice passed. He had it in his heart to cry aloud, to send the words ringing through that hushed room, "She would have tramped here barefoot had she had one guide with a spirit to match hers." For a moment he almost fancied that he had spoken them, and that he heard the echo of his voice vibrating down to silence. But he had not, and as he realised that he had not, a new thought occurred to him. No one had remarked his entrance into the room. The group in front still stood with their backs towards him. Since his entrance no one had remarked his presence. At once he turned and opened the door so gently that there was not so much as a click of the latch. He opened it just wide enough for himself to slip through, and he closed it behind him with the same caution. On the landing there was only the usher. Wogan looked over the balustrade; there was no one in the hall below.

"You can keep a silent tongue," he said to the usher. "There's profit in it;" and Wogan put his hand into his pocket. "You have not seen me if any ask."

"Sir," said the man, "any bright object disturbs my vision."

"You can see a crown, though," said Wogan.

"Through a breeches pocket. But if I held it in my hand —"

"It would dazzle you."

"So much that I should be blind to the giver."

The crown was offered and taken.

Wogan went quietly down the stairs into the hall. There were a few lackeys at the door, but they would not concern themselves at all because Mr. Wogan had returned to Bologna. He looked carefully out into the street, chose a moment when it was empty, and hurried across it. He dived into the first dark alley that he came to, and following the wynds and byways of the town made his way quickly to his lodging. He had the key to his door in his pocket, and he now kept it ready in his hand. From the shelter of a corner he watched again till the road was clear; he even examined the windows of the neighbouring houses lest somewhere a pair of eyes might happen to be alert. Then he made a run for his door, opened it without noise, and crept secretly as a thief up the stairs to his rooms, where he had the good fortune to find his servant. Wogan had no need to sign to him to be silent. The man was a veteran corporal of French Guards who after many seasons of campaigning in Spain and the Low Countries had now for five years served Mr. Wogan. He looked at his master and without a word went off to make his bed.

Wogan sat down and went carefully over in his mind every minute of the time since he had entered Bologna. No one had noticed him when he rode in as the lady's postillion,—no one. He was sure of that. The lady herself did not know him from Adam, and fancied him an Italian into the bargain —of that, too, he had no doubt. The handful of lackeys at the door of the King's house need not be taken into account. They might gossip among themselves, but Wogan's appearances and disappearances were so ordinary a matter, even that was unlikely. The usher's silence he had already secured. There was only one acquaintance who had met and spoken with him, and that by the best of good fortune was Harry Whittington,—the idler who took his banishment and his King's misfortunes with an equally light heart, and gave never a thought at all to anything weightier than a gamecock.

Wogan's spirits revived. He had not yet come to the end of his luck. He sat down and wrote a short letter and sealed it up.

"Marnier," he called out in a low voice, and his servant came from the adjoining room, "take this to Mr. Edgar, the King's secretary, as soon as it grows dusk. Have a care that no one sees you deliver it. Lock the parlour door when you go, and take the key. I am not yet back from Rome." With that Wogan remembered that he had not slept for forty-eight hours. Within two minutes he was between the sheets; within five he was asleep.

Wogan waked up in the dark and was seized with a fear that he had slept too long. He jumped out of bed and pushed open the door of his parlour. There was a lighted lamp in the room, and Marnier was quietly laying his master's supper.

"At what hour?" asked Wogan.

"Ten o'clock, monsieur, at the little postern in the garden wall."

"And the time now?"

"Nine."

Wogan dressed with some ceremony, supped, and at eight minutes to ten slipped down the stairs and out of doors. He had crushed his hat down upon his forehead and he carried his handkerchief at his face. But the streets were dark and few people were abroad. At a little distance to his left he saw above the housetops a glow of light in the air which marked the Opera-House. Wogan avoided it; he kept again to the alleys and emerged before the Chevalier's lodging. This he passed, but a hundred yards farther on he turned down a side street and doubled back upon his steps along a little byway between small houses. The line of houses, however, at one point was broken by a garden wall. Under this wall Wogan waited until a clock struck ten, and while the clock was still striking he heard on the other side of the wall the brushing of footsteps amongst leaves and grass. Wogan tapped gently on a little door in the wall. It was opened no less gently, and Edgar the secretary admitted him, led him across the garden and up a narrow flight of stairs into a small lighted cabinet. Two men were waiting in that room. One of them wore the scarlet robe, an old man with white hair and a broad bucolic face, whom Wogan knew for the Pope's Legate, Cardinal Origo. The slender figure of the other, clad all in black but for the blue ribbon of the Garter across his breast, brought Wogan to his knee.

Wogan held out the Pope's procuration to the Chevalier, who took it and devoutly kissed the signature. Then he gave his hand to Wogan with a smile of friendliness.

"You have outsped your time by two days, Mr. Wogan. That is unwise, since it may lead us to expect again the impossible of you. But here, alas, your speed for once brings us no profit. You have heard, no doubt. Her Highness the Princess Clementina is held at Innsbruck in prison."

Wogan rose to his feet.

"Prisons, sir," he said quietly, "have been broken before to- day. I myself was once put to that necessity." The words took the Chevalier completely by surprise. He leaned back in his chair and stared at Wogan.

"An army could not rescue her," he said.

"No, but one man might."

"You?" he exclaimed. He pressed down the shade of the lamp to throw the light fully upon Wogan's face. "It is impossible!"

"Then I beg your Majesty to expect the impossible again."

The Chevalier drew his hand across his eyes and stared afresh at Wogan. The audacity of the exploit and the imperturbable manner of its proposal caught his breath away. He rose from his chair and took a turn or two across the room.

Wogan watched his every gesture. It would be difficult he knew to wring the permission he needed from his dejected master, and his unruffled demeanour was a calculated means of persuasion. An air of confidence was the first requisite. In reality, however, Wogan was not troubled at this moment by any thought of failure. It was not that he had any plan in his head; but he was fired with a conviction that somehow this chosen woman was not to be wasted, that some day, released by some means in spite of all the pressure English Ministers could bring upon the Emperor, she would come riding into Bologna.

The Chevalier paused in his walk and looked towards the Cardinal.

"What does your Eminence say?"

"That to the old the impulsiveness of youth is eternally charming," said the Cardinal, with a foppish delicacy of speaking in an odd contrast to his person.

Mr. Wogan understood that he had a second antagonist.

"I am not a youth, your Eminence," he exclaimed with all the indignation of twenty-seven years. "I am a man."

"But an Irishman, and that spells youth. You write poetry too, I believe, Mr. Wogan. It is a heady practice."

Wogan made no answer, though the words stung. An argument with the Cardinal would be sure to ruin his chance of obtaining the Chevalier's consent. He merely bowed to the Cardinal and waited for the Chevalier to speak.

"Look you, Mr. Wogan; while the Emperor's at war with Spain, while England's fleet could strip him of Sicily, he's England's henchman. He dare not let the Princess go. We know it. General Heister, the Governor of Innsbruck, is under pain of death to hold her safe."

"But, sir, would the world stop if General Heister died?"

"A German scaffold if you fail."

"In the matter of scaffolds I have no leaning towards any one nationality."

The Cardinal smiled. He liked a man of spirit, though he might think him absurd. The Chevalier resumed his restless pacing to and fro.

"It is impossible."

But he seemed to utter the phrase with less decision this second time. Wogan pressed his advantage at the expense of his modesty.

"Sir, will you allow me to tell you a story,—a story of an impossible escape from Newgate in the heart of London by a man in fetters? There were nine grenadiers with loaded muskets standing over him. There were two courtyards to cross, two walls to climb, and beyond the walls the unfriendly streets. The man hoodwinked his sentries, climbed his two walls, crossed the unfriendly streets, and took refuge in a cellar, where he was discovered. From the cellar in broad daylight he fought his way to the roofs, and on the roofs he played such a game of hide-and- seek among the chimney-tops —" Wogan broke off from his story with a clear thrill of laughter; it was a laugh of enjoyment at a pleasing recollection. Then he suddenly flung himself down on his knee at the feet of his sovereign. "Give me leave, your Majesty," he cried passionately. "Let me go upon this errand. If I fail, if the scaffold's dressed for me, why where's the harm? Your Majesty loses one servant out of his many. Whereas, if I win —" and he drew a long breath. "Aye, and I shall win! There's the Princess, too, a prisoner. Sir, she has ventured much. I beg you give me leave."

The Chevalier laid his hand gently upon Wogan's shoulder, but he did not assent. He looked again doubtfully to the Cardinal, who said with his pleasant smile, "I will wager Mr. Wogan a box at the Opera on the first night that he returns, that he will return empty-handed."

Wogan rose to his feet and replied good-humouredly, "It's a wager I take the more readily in that your Eminence cannot win, though you may lose. For if I return empty-handed, upon my honour I'll not return at all."

The Cardinal condescended to laugh. Mr. Wogan laughed too. He had good reason, for here was his Eminence in a kindly temper and the Chevalier warming out of his melancholy. And, indeed, while he was still laughing the Chevalier caught him by the arm as a friend might do, and in an outburst of confidence, very rare with him, he said, "I would that I could laugh so. You and Whittington, I do envy you. An honest laugh, there's the purge for melancholy. But I cannot compass it," and he turned away.

"Sure, sir, you'll put us all to shame when I bring her Royal Highness out of Innsbruck."

"Oh, that!" said the Chevalier, as though for the moment he had forgotten. "It is impossible," and the phrase was spoken now in an accent of hesitation. Moreover, he sat down at a table, and drawing a sheet of paper written over with memoranda, he began to read aloud with a glance towards Wogan at the end of each sentence.

"The house stands in the faubourgs of Innsbruck. There is an avenue of trees in front of the house; on the opposite side of the avenue there is a tavern with the sign of 'The White Chamois.'"

Wogan committed the words to memory.

"The Princess and her mother," continued the Chevalier, "are imprisoned in the east side of the house."

"And how guarded, sir?" asked Wogan.

The Chevalier read again from his paper.

"A sentry at each door, a third beneath the prisoners' windows. They keep watch night and day. Besides, twice a day the magistrate visits the house."

"At what hours?"

"At ten in the morning. The same hour at night."

"And on each visit the magistrate sees the Princess?"

"Yes, though she lies abed."

Wogan stroked his chin. The Cardinal regarded him quizzically.

"I trust, Mr. Wogan, that we shall hear Farini. There is talk of his coming to Bologna."

Wogan did not answer. He was silent; he saw the three sentinels standing watchfully about the house; he heard them calling "All's well" each to the other. Then he asked, "Has the Princess her own servants to attend her?"

"Only M. Chateaudoux, her chamberlain."

"Ah!"

Wogan leaned forward with a question on his tongue he hardly dared to ask. So much hung upon the answer.

"And M. Chateaudoux is allowed to come and go?"

"In the daylight."

Wogan turned to the Cardinal. "The box will be the best box in the house," Wogan suggested.

"Oh, sir," replied the Cardinal, "on the first tier, to be sure."

Wogan turned back to the Chevalier.

"All that I need now is a letter from your Majesty to the King of Poland and a few rascally guineas. I can leave Bologna before a soul's astir in the morning. No one but Whittington saw me to- day, and a word will keep him silent. There will be secrecy —" but the Chevalier suddenly cut him short.

"No," said he, bringing the palm of his hand down upon the table. "Here's a blow that we must bend to! It's a dream, this plan of yours."

"But a dream I'll dream so hard, sir, that I'll dream it true," cried Wogan, in despair.

"No, no," said the Chevalier. "We'll talk no more of it. There's God's will evident in this arrest, and we must bend to it;" and at once Wogan remembered his one crowning argument. It was so familiar to his thoughts, it had lain so close at his heart, that he had left it unspoken, taking it as it were for granted that others were as familiar with it as he.

"Sir," said he, eagerly, "I have never told you, but the Princess Clementina when a child amongst her playmates had a favourite game. They called it kings and queens. And in that game the Princess was always chosen Queen of England."

The Chevalier started.

"Is that so?" and he gazed into Wogan's eyes, making sure that he spoke the truth.

"In very truth it is," and the two men stood looking each at the other and quite silent.

It was the truth, a mere coincidence if you will, but to both these men omens and auguries were the gravest matters.

"There indeed is God's finger pointing," cried Wogan. "Sir, give me leave to follow it."

The Chevalier still stood looking at him in silence. Then he said suddenly, "Go, then, and God speed you! You are a gallant gentleman."

He sat down thereupon and wrote a letter to the King of Poland, asking him to entrust the rescue of his daughter into Wogan's hands. This letter Wogan took and money for his journey.

"You will have preparations to make," said the Chevalier. "I will not keep you. You have horses?"

Mr. Wogan had two in a stable at Bologna. "But," he added, "there is a horse I left this morning six miles this side of Fiesole, a black horse, and I would not lose it."

"Nor shall you," said the Chevalier.

Wogan crept back to his lodging as cautiously as he had left it. There was no light in any window but in his own, where his servant, Marnier, awaited him. Wogan opened the door softly and found the porter asleep in his chair. He stole upstairs and made his preparations. These, however, were of the simplest kind, and consisted of half-a-dozen orders to Marnier and the getting into bed. In the morning he woke before daybreak and found Marnier already up. They went silently out of the house as the dawn was breaking. Marnier had the key to the stables, and they saddled the two horses and rode through the blind and silent streets with their faces muffled in their cloaks.

They met no one, however, until they were come to the outskirts of the town. But then as they passed the mouth of an alley a man came suddenly out and as suddenly drew back. The morning was chill, and the man was closely wrapped.

Wogan could not distinguish his face or person, and looking down the alley he saw at the end of it only a garden wall, and over the top of the wall a thicket of trees and the chimney-tops of a low house embosomed amongst them. He rode on, secure in the secrecy of his desperate adventure. But that same morning Mr. Whittington paid a visit to Wogan's lodging and asked to be admitted. He was told that Mr. Wogan had not yet returned to Bologna.

"So, indeed, I thought," said he; and he sauntered carelessly along, not to his own house, but to one smaller, situated at the bottom of a cul-de-sac and secluded amongst trees. At the door he asked whether her Ladyship was yet visible, and was at once shown into a room with long windows which stood open to the garden. Her Ladyship lay upon a sofa sipping her coffee and teasing a spaniel with the toe of her slipper.

"You are early," she said with some surprise.

"And yet no earlier than your Ladyship," said Whittington.

"I have to make my obeisance to my King," said she, stifling a yawn. "Could one, I ask you, sleep on so important a day?"

Mr. Whittington laughed genially. Then he opened the door and glanced along the passage. When he turned back into the room her Ladyship had kicked the spaniel from the sofa and was sitting bolt upright with all her languor gone.

"Well?" she asked quickly.

Whittington took a seat on the sofa by her side.

"Charles Wogan left Bologna at daybreak. Moreover, I have had a message from the Chevalier bidding me not to mention that I saw him in Bologna yesterday. One could hazard a guess at the goal of so secret a journey."

"Ohlau!" exclaimed the lady, in a whisper. Then she nestled back upon the sofa and bit the fragment of lace she called her handkerchief.

"So there's an end of Mr. Wogan," she said pleasantly.

Whittington made no answer.

"For there's no chance that he'll succeed," she continued with a touch of anxiety in her voice.

Whittington neither agreed nor contradicted. He asked a question instead.

"What is the sharpest spur a man can know? What is it that gives a man audacity to attempt and wit to accomplish the impossible?"

The lady smiled.

"The poets tell us love," said she, demurely.

Whittington nodded his head.

"Wogan speaks very warmly of the Princess Clementina."

Her Ladyship's red lips lost their curve. Her eyes became thoughtful, apprehensive.

"I wonder," she said slowly.

"Yes, I too wonder," said Whittington.

Outside the branches of the trees rustled in the wind and flung shadows, swift as ripples, across the sunlit grass. But within the little room there was a long silence.

M. Chateaudoux, the chamberlain, was a little portly person with a round, red face like a cherub's. He was a creature of the house, one that walked with delicate steps, a conductor of ceremonies, an expert in the subtleties of etiquette; and once he held his wand of office in his hand, there was nowhere to be found a being so precise and consequential. But out of doors he had the timidity of a cat. He lived, however, by rule and rote, and since it had always been his habit to take the air between three and four of the afternoon, he was to be seen between those hours at Innsbruck on any fine day mincing along the avenue of trees before the villa in which his mistress was held prisoner.

On one afternoon during the month of October he passed a hawker, who, tired with his day's tramp, was resting on a bench in the avenue, and who carried upon his arm a half-empty basket of cheap wares. The man was ragged; his toes were thrusting through his shoes; it was evident that he wore no linen, and a week's growth of beard dirtily stubbled his chin,—in a word, he was a man from whom M. Chateaudoux's prim soul positively shrank. M. Chateaudoux went quickly by, fearing to be pestered for alms. The hawker, however, remained seated upon the bench, drawing idle patterns upon the gravel with a hazel stick stolen from a hedgerow.

The next afternoon the hawker was in the avenue again, only this time on a bench at the opposite end; and again he paid no heed to M. Chateaudoux, but sat moodily scraping the gravel with his stick.

On the third afternoon M. Chateaudoux found the hawker seated in the middle of the avenue and over against the door of the guarded villa. M. Chateaudoux, when his timidity slept, was capable of good nature. There was a soldier with a loaded musket in full view. The hawker, besides, had not pestered him. He determined to buy some small thing,—a mirror, perhaps, which was always useful,—and he approached the hawker, who for his part wearily flicked the gravel with his stick and drew a curve here and a line there until, as M. Chateaudoux stopped before the bench, there lay sketched at his feet the rude semblance of a crown. The stick swept over it the next instant and left the gravel smooth.

But M. Chateaudoux had seen, and his heart fluttered and sank. For here were plots, possibly dangers, most certainly trepidations. He turned his back as though he had seen nothing, and constraining himself to a slow pace walked towards the door of the villa. But the hawker was now at his side, whining in execrable German and a strong French accent the remarkable value of his wares. There were samplers most exquisitely worked, jewels for the most noble gentleman's honoured sweetheart, and purses which emperors would give a deal to buy. Chateaudoux was urged to take notice that emperors would give sums to lay a hand on the hawker's purses.

M. Chateaudoux pretended not to hear.

"I want nothing," he said, "nothing in the world;" and he repeated the statement in order to drown the other's voice.

"A purse, good gentleman," persisted the hawker, and he dangled one before Chateaudoux's eyes. Not for anything would Chateaudoux take that purse.

"Go away," he cried; "I have a sufficiency of purses, and I will not be plagued by you."

They were now at the steps of the villa, and the sentry, lifting the butt of his musket, roughly thrust the hawker back.

"What have you there? Bring your basket here," said he; and to Chateaudoux's consternation the hawker immediately offered the purse to the sentinel.

"It is only the poor who have kind hearts," he said; "here's the proper purse for a soldier. It is so hard to get the money out that a man is saved an ocean of drink."

The hawker's readiness destroyed any suspicions the sentinel may have felt.

"Go away," he said, "quick!"

"You will buy the purse?"

The sentinel raised his musket again.

"Then the kind gentleman will," said the hawker, and he thrust the purse into M. Chateaudoux's reluctant hand. Chateaudoux could feel within the purse a folded paper. He was committed now without a doubt, and in an extreme alarm he flung a coin into the roadway and got him into the house. The sentinel carelessly dropped the butt of his musket on the coin.

"Go," said he, and with a sudden kick he lifted the hawker half across the road. The hawker happened to be Charles Wogan, who took a little matter like that with the necessary philosophy. He picked himself up and limped off.

Now the next day a remarkable thing happened. M. Chateaudoux swerved from the regularity of his habits. He walked along the avenue, it is true; but at the end of it he tripped down a street and turned out of that into another which brought him to the arcades. He did not appear to enjoy his walk; indeed, any hurrying footsteps behind startled him exceedingly and made his face turn white and red, and his body hot and cold. However, he proceeded along the arcades to the cathedral, which he entered; and just as the clock struck half-past three, in a dark corner opposite to the third of the great statues he drew his handkerchief from his pocket.

The handkerchief flipped out a letter which fell onto the ground. In the gloom it was barely visible; and M. Chateaudoux walked on, apparently unconscious of his loss. But a comfortable citizen in a snuff-coloured suit picked it up and walked straight out of the cathedral to the Golden Fleece Inn in the Hochstrasse, where he lodged. He went up into his room and examined the letter. It was superscribed "To M. Chateaudoux," and the seal was broken. Nevertheless, the finder did not scruple to read it. It was a love-letter to the little gentleman from one Friederika.

"I am heart-broken," wrote Friederika, "but my fidelity to my Chateaudoux has not faltered, nor will not, whatever I may be called upon to endure. I cannot, however, be so undutiful as to accept my Chateaudoux's addresses without my father's consent; and my mother, who is of the same mind with me, insists that even with that consent a runaway marriage is not to be thought of unless my Chateaudoux can provide me with a suitable woman for an attendant."

These conditions fulfilled, Friederika was willing to follow her Chateaudoux to the world's end. The comfortable citizen in the snuff-coloured suit sat for some while over that letter with a strange light upon his face and a smile of great happiness. The comfortable citizen was Charles Wogan, and he could dissociate the obstructions of the mother from the willingness of the girl.

The October evening wove its veils from the mountain crests across the valleys; the sun and the daylight had gone from the room before Wogan tore that letter up and wrote another to the Chevalier at Bologna, telling him that the Princess Clementina would venture herself gladly if he could secure the consent of Prince Sobieski, her father. And the next morning he drove out in a carriage towards Ohlau in Silesia.

It was as the Chevalier Warner that he had first journeyed thither to solicit for his King the Princess Clementina's hand. Consequently he used the name again. Winter came upon him as he went; the snow gathered thick upon the hills and crept down into the valleys, encumbering his path. The cold nipped his bones; he drove beneath great clouds and through a stinging air, but of these discomforts he was not sensible. For the mission he was set upon filled his thoughts and ran like a fever in his blood. He lay awake at nights inventing schemes of evasion, and each morning showed a flaw, and the schemes crumbled. Not that his faith faltered. At some one moment he felt sure the perfect plan, swift and secret, would be revealed to him, and he lived to seize the moment. The people with whom he spoke became as shadows; the inns where he rested were confused into a common semblance. He was like a man in a trance, seeing ever before his eyes the guarded villa at Innsbruck, and behind the walls, patient and watchful, the face of the chosen woman; so that it was almost with surprise that he looked down one afternoon from the brim of a pass in the hills and saw beneath him, hooded with snow, the roofs and towers of Ohlau.

At Ohlau Wogan came to the end of his luck. From the moment when he presented his letter he was aware of it. The Prince was broken by his humiliation and the sufferings of his wife and daughter. He was even inclined to resent them at the expense of the Chevalier, for in his welcome to Wogan there was a measure of embarrassment. His shoulders, which had before been erect, now stooped, his eyes were veiled, the fire had burnt out in him; he was an old man visibly ageing to his grave. He read the letter and re-read it.

"No," said he, impatiently; "I must now think of my daughter. Her dignity and her birth forbid that she should run like a criminal in fear of capture, and at the peril very likely of her life, to a king who, after all, is as yet without a crown." And then seeing Wogan flush at the words, he softened them. "I frankly say to you, Mr. Warner, that I know no one to whom I would sooner entrust my daughter than yourself, were I persuaded to this project. But it is doomed to fail. It would make us the laughing-stock of Europe, and I ask you to forget it. Do you fancy the Emperor guards my daughter so ill that you, single- handed, can take her from beneath his hand?"

"Your Highness, I shall choose some tried friends to help me."

"There is no single chance of success. I ask you to forget it and to pass your Christmas here as my very good friend. The sight is longer in age, Mr. Warner, than in youth, and I see far enough now to know that the days of Don Quixote are dead. Here is a matter where all Europe is ranged and alert on one side or the other. You cannot practise secrecy. At Ohlau your face is known, your incognito too. Mr. Warner came to Ohlau once before, and the business on which he came is common knowledge. The motive of your visit now, which I tell you openly is very grateful to me, will surely be suspected."

Wogan had reason that night to acknowledge the justice of the Prince's argument. He accepted his hospitality, thinking that with time he would persuade him to allow the attempt; and after supper, while making riddles in verse to amuse some of the ladies of the court, one of them, the Countess of Berg, came forward from a corner where she had been busy with pencil and paper and said, "It is our turn now. Here, Mr. Warner, is an acrostic which I ask you to solve for me." And with a smile which held a spice of malice she handed him the paper. Upon it there were ten rhymed couplets. Wogan solved the first four, and found that the initial letters of the words were C, L, E, M. The answer to the acrostic was "Clementina." Wogan gave the paper back.

"I can make neither head nor tail of it," said he. "The attempt is beyond my powers."

"Ah," said she, drily, "you own as much? I would never have believed you would have owned it."

"But what is the answer?" asked a voice at which Wogan started.

"The answer," replied the Countess, "is Mary, Queen of Scots, who was most unjustly imprisoned in Fotheringay," and she tore the paper into tiny pieces.

Wogan turned towards the voice which had so startled him and saw the gossamer lady whom he had befriended on the road from Florence. At once he rose and bowed to her.

"I should have presented you before to my friend, Lady Featherstone," said the Countess, "but it seems you are already acquainted."

"Indeed, Mr. Warner did me a great service at a pinch," said Lady Featherstone. "He was my postillion, though I never paid him, as I do now in thanks."

"Your postillion!" cried one or two of the ladies, and they gathered about the great stove as Lady Featherstone told the story of Wogan's charioting.

"I bade him hurry," said she, "and he outsped my bidding. Never was there a postillion so considerately inconsiderate. I was tossed like a tennis ball, I was one black bruise, I bounced from cushion to cushion; and then he drew up with a jerk, sprang off his horse, vanished into a house and left me, panting and dishevelled, a twist of torn ribbons and lace, alone in my carriage in the streets of Bologna."

"Bologna. Ah!" said the Countess, with a smile of significance at Wogan.

Wogan was looking at Lady Featherstone. His curiosity, thrust into the back of his mind by the more important matter of his mission now revived. What had been this lady's business who travelled alone to Bologna and in such desperate haste?

"Your Ladyship, I remember," he said, "gave me to understand that you were sorely put to it to reach Bologna."

Her Ladyship turned her blue eyes frankly upon Wogan. Then she lowered them.

"My brother," she explained, "lay at death's door in Venice. I had just landed at Leghorn, where I left my maid to recover from the sea, and hurrying across Italy as I did, I still feared that I should not see him alive."

The explanation was made readily in a low voice natural to one remembering a great distress, but without any affectation of gesture or so much as a glance sideways to note whether Wogan received it trustfully or not. Wogan, indeed, was reassured in a great measure. True, the Countess of Berg was now his declared enemy, but he need not join all her friends in that hostility.

"I was able, most happily," continued Lady Featherstone, "to send my brother homewards in a ship a fortnight back, and so to stay with my friend here on my way to Vienna, for we English are all bitten with the madness of travel. Mr. Warner will bear me out?"

"To be sure I will," said Wogan, stoutly. "For here am I in the depths of winter journeying to the carnival in Italy."

The Countess smiled, all disbelief and amusement, and Lady Featherstone turned quickly towards him.

"For my frankness I claim a like frankness in return," said she, with a pretty imperiousness.

Wogan was a little startled. He suddenly remembered that he had pretended to know no English on the road to Bologna, nor had he given any reason for his haste. But it was upon neither of these matters that she desired to question him.

"You spoke in parables," said she, "which are detestable things. You said you would not lose your black horse for the world because the lady you were to marry would ride upon it into your city of dreams. There's a saying that has a provoking prettiness. I claim a frank answer."

Wogan was silent, and his face took on the look of a dreamer.

"Come," said one. It was the Princess Charlotte, the second daughter of the Prince Sobieski, who spoke. "We shall not let you off," said she.

Wogan knew that she would not. She was a girl who was never checked by any inconvenience her speech might cause. Her tongue was a watchman's rattle, and she never spoke but she laughed to point the speech.

"Be frank," said the Countess; "it is a matter of the heart, and so proper food for women."

"True," answered Wogan, lightly, "it is a matter of the heart, and in such matters can one be frank—even to oneself?"

Wogan was immediately puzzled by the curious look Lady Featherstone gave him. The words were a mere excuse, yet she seemed to take them very seriously. Her eyes sounded him.

"Yes," she said slowly; "are you frank, even to yourself?" and she spoke as though a knowledge of the answer would make a task easier to her.

Wogan's speculations, however, were interrupted by the entrance of Princess Casimira, Sobieski's eldest daughter. Wogan welcomed her coming for the first time in all his life, for she was a kill-joy, a person of an extraordinary decorum. According to Wogan, she was "that black care upon the horseman's back which the poets write about." Her first question if she was spoken to was whether the speaker was from top to toe fitly attired; her second, whether the words spoken were well-bred. At this moment, however, her mere presence put an end to the demands for an explanation of Wogan's saying about his horse, and in a grateful mood to her he slipped from the room.

This evening was but one of many during that Christmastide. Wogan must wear an easy countenance, though his heart grew heavy as lead. The Countess of Berg was the Prince Constantine's favourite; and Wogan was not slow to discover that her smiling face and quiet eyes hid the most masterful woman at that court. He made himself her assiduous servant, whether in hunting amid the snow or in the entertainments at the palace, but a quizzical deliberate word would now and again show him that she was still his enemy. With the Princess Casimira he was a profound critic of observances: he invented a new cravat and was most careful that there should never be a wrinkle in his stockings; with the Princess Charlotte he laughed till his head sang. He played all manner of parts; the palace might have been the stage of a pantomime and himself the harlequin. But for all his efforts it did not seem that he advanced his cause; and if he made headway one evening with the Prince, the next morning he had lost it, and so Christmas came and passed.

But two days after Christmas a courier brought a letter to the castle. He came in the evening, and the letter was carried to Wogan while he was at table. He noticed at once that it was in his King's hand, and he slipped it quickly into his pocket. It may have been something precipitate in his manner, or it may have been merely that all were on the alert to mark his actions, but at once curiosity was aroused. No plain words were said; but here and there heads nodded together and whispered, and while some eyed Wogan suspiciously, a few women whose hearts were tuned to a sympathy with the Princess in her imprisonment, or touched with the notion of a romantic attachment, smiled upon him their encouragement. The Countess of Berg for once was unobservant, however.

Wogan made his escape from the company as soon as he could, and going up to his apartments read the letter. The moon was at its full, and what with the clear, frosty air, and the snow stretched over the world like a white counterpane, he was able to read the letter by the window without the light of a candle. It was written in the Chevalier's own cipher and hand; it asked anxiously for news and gave some. Wogan had had occasion before to learn that cipher by heart. He stood by the window and spelled the meaning. Then he turned to go down; but at the door his foot slipped upon the polished boards, and he stumbled onto his knee. He picked himself up, and thinking no more of the matter rejoined the company in a room where the Countess of Berg was playing upon a harp.

"The King," said Wogan, drawing the Prince apart, "leaves Bologna for Rome."

"So the letter came from him?" asked the Prince, with an eagerness which could not but seem hopeful to his companion.

"And in his own hand," replied Wogan.

The Prince shuffled and hesitated as though he was curious to hear particulars. Wogan thought it wise to provoke his curiosity by disregarding it. It seemed that there was wisdom in his reticence, for a little later the Prince took him aside while the Countess of Berg was still playing upon her harp, and said, —

"Single-handed you could do nothing. You would need friends."

Wogan took a slip of paper from his pocket and gave it to the Prince.

"On that slip," said he, "I wrote down the names of all the friends whom I could trust, and by the side of the names the places where I could lay my hands upon them. One after the other I erased the names until only three remained."

The Prince nodded and read out the names.

"Gaydon, Misset, O'Toole. They are good men?"

"The flower of Ireland. Those three names have been my comfort these last three weeks."

"And all the three at Schlestadt. How comes that about?"

"Your Highness, they are all three officers in Dillon's Irish regiment, and so have that further advantage."

"Advantage?"

"Your Highness," said Wogan, "Schlestadt is near to Strasbourg, which again is not far from Innsbruck, and being in French territory would be the most convenient place to set off from."

There was a sound of a door shutting; the Prince started, looked at Wogan, and laughed. He had been upon the verge of yielding; but for that door Wogan felt sure he would have yielded. Now, however, he merely walked away to the Countess of Berg, and sitting beside her asked her to play a particular tune. But he still held the slip of paper in his hand and paid but a scanty heed to the music, now and then looking doubtfully towards Wogan, now and then scanning that long list of names. His lips, too, moved as though he was framing the three selected names, Gaydon, Misset, O'Toole, and "Schlestadt" as a bracket uniting them. Then he suddenly rose up and crossed the room to Wogan.

"My daughter wrote that a woman must attend her. It is a necessary provision."

"Your Highness, Misset has a wife, and the wife matches him."

"They are warned to be ready?"

"At your Highness's first word that slip of paper travels to Schlestadt. It is unsigned, it imperils no one, it betrays nothing. But it will tell its story none the less surely to those three men, for Gaydon knows my hand."

The Prince smiled in approval.

"You have prudence, Mr. Warner, as well as audacity," said he. He gave the paper back, listened for a little to the Countess, who was bending over her harp-strings, and then remarked, "The Prince's letter was in his own hand too?"

"But in cipher."

"Ah!"

The Prince was silent for a while. He balanced himself first on one foot, then on the other.

"Ciphers," said he, "are curious things, compelling to the imagination and a provocation to the intellect."

Mr. Wogan kept a grave face and he replied with unconcern, though his heart beat quick; for if the Prince had so much desire to see the Chevalier's letter, he must be well upon his way to consenting to Wogan's plan.

"If your Highness will do me the honour to look at this cipher. It has baffled the most expert."

His Highness condescended to be pleased with Wogan's suggestion. Wogan crossed the room towards the door; but before he reached it, the Countess of Berg suddenly took her fingers from her harp-strings with a gesture of annoyance.

"Mr. Warner," she said, "will you do me the favour to screw this wire tighter?" And once or twice she struck it with her fingers.

"May I claim that privilege?" said the Prince.

"Your Highness does me too much honour," said the Countess, but the Prince was already at her side. At once she pointed out to him the particular string. Wogan went from the room and up the great staircase. He was lodged in a wing of the palace. From the head of the staircase he proceeded down a long passage. Towards the end of this passage another short passage branched off at a right angle on the left-hand side. At the corner of the two passages stood a table with a lamp and some candlesticks. This time Wogan took a candle, and lighting it at the lamp turned into the short passage. It was dark but for the light of Wogan's candle, and at the end of it facing him were two doors side by side. Both doors were closed, and of these the one on the left gave onto his room.

Wogan had walked perhaps halfway from the corner to his door before he stopped. He stopped suddenly and held his breath. Then he shaded his candle with the palm of his hand and looked forward. Immediately he turned, and walking on tiptoe came silently back into the big passage. Even this was not well lighted; it stretched away upon his right and left, full of shadows. But it was silent. The only sounds which reached Wogan as he stood there and listened were the sounds of people moving and speaking at a great distance. He blew out his candle, cautiously replaced it on the table, and crept down again towards his room. There was no window in this small passage, there was no light there at all except a gleam of silver in front of him and close to the ground. That gleam of silver was the moonlight shining between the bottom of one of the doors and the boards of the passage. And that door was not the door of Wogan's room, but the room beside it. Where his door stood, there might have been no door at all.

Yet the moon which shone through the windows of one room must needs also shine into the other, unless, indeed, the curtains were drawn. But earlier in the evening Wogan had read a letter by the moonlight at his window; the curtains were not drawn. There was, therefore, a rug, an obstruction of some sort against the bottom of the door. But earlier in the evening Wogan's foot had slipped upon the polished boards; there had been no mat or skin at all. It had been pushed there since. Wogan could not doubt for what reason. It was to conceal the light of a lamp or candle within the room. Someone, in a word, was prying in Wogan's room, and Wogan began to consider who. It was not the Countess, who was engaged upon her harp, but the Countess had tried to detain him. Wogan was startled as he understood the reason of her harp becoming so suddenly untuned. She had spoken to him with so natural a spontaneity, she had accepted the Prince's aid with so complete an absence of embarrassment; but none the less Wogan was sure that she knew. Moreover, a door had shut —yes, while he was speaking to the Prince a door had shut.

So far Wogan's speculations had travelled when the moonlight streamed out beneath his door too. It made now a silver line across the passage broken at the middle by the wall between the rooms. The mat had been removed, the candle put out, the prying was at an end; in another moment the door would surely open. Now Wogan, however anxious to discover who it was that spied, was yet more anxious that the spy should not discover that the spying was detected. He himself knew, and so was armed; he did not wish to arm his enemies with a like knowledge. There was no corner in the passage to conceal him; there was no other door behind which he could slip. When the spy came out, Wogan would inevitably be discovered. He made up his mind on the instant. He crept back quickly and silently out of the mouth of the passage, then he made a noise with his feet, turned again into the passage, and walked loudly towards his door. Even so he was only just in time. Had he waited a moment longer, he would have been detected. For even as he turned the corner there was already a vertical line of silver on the passage wall; the door had been already opened. But as his footsteps sounded on the boards, that line disappeared.

He walked slowly, giving his spy time to replace the letter, time to hide. He purposely carried no candle, he reached his door and opened it. The room to all seeming was empty. Wogan crossed to a table, looking neither to the right nor the left, above all not looking towards the bed hangings. He found the letter upon the table just as he had left it. It could convey no knowledge of his mission, he was sure. It had not even the appearance of a letter in cipher; it might have been a mere expression of Christmas good wishes from one friend to another. But to make his certainty more sure, and at the same time to show that he had no suspicion anyone was hiding in the room, he carried the letter over to the window, and at once he was aware of the spy's hiding- place. It was not the bed hangings, but close at his side the heavy window curtain bulged. The spy was at his very elbow; he had but to lift his arm—and of a sudden the letter slipped from his hand to the floor. He did not drop it on purpose, he was fairly surprised; for looking down to read the letter he had seen protruding from the curtain a jewelled shoe buckle, and the foot which the buckle adorned seemed too small and slender for a man's.

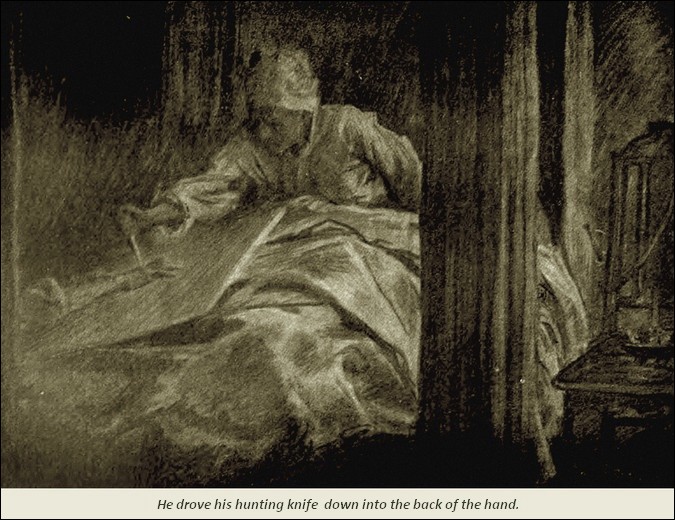

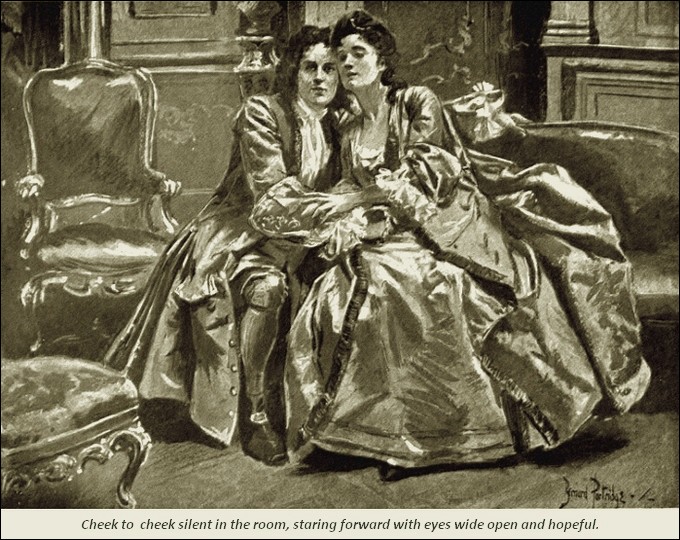

Wogan had an opportunity to make certain. He knelt down and picked up the letter; the foot was a woman's. As he rose up again, the curtain ever so slightly stirred. Wogan pretended to have remarked nothing; he stood easily by the window with his eyes upon his letter and his mind busy with guessing what woman his spy might be. And he remained on purpose for some while in this attitude, designing it as a punishment. So long as he stood by the window that unknown woman cheek by jowl with him must hold her breath, must never stir, must silently endure an agony of fear at each movement that he made.

At last he moved, and as he turned away he saw something so unexpected that it startled him. Indeed, for the moment it did more than startle him, it chilled him. He understood that slight stirring of the curtain. The woman now held a dagger in her hand, and the point of the blade stuck out and shone in the moonlight like a flame.

Wogan became angry. It was all very well for the woman to come spying into his room; but to take a dagger to him, to think a dagger in a woman's hand could cope with him,—that was too preposterous. Wogan felt very much inclined to sweep that curtain aside and tell his visitor how he had escaped from Newgate and played hide-and-seek amongst the chimney-pots. And although he restrained himself from that, he allowed his anger to get the better of his prudence. Under the impulse of his anger he acted. It was a whimsical thing that he did, and though he suffered for it he could never afterwards bring himself to regret it. He deliberately knelt down and kissed the instep of the foot which protruded from the curtain. He felt the muscles of the foot tighten, but the foot was not withdrawn. The curtain shivered and shook, but no cry came from behind it, and again the curtain hung motionless. Wogan went out of the room and carried the letter to the Prince. The Countess of Berg was still playing upon her harp, and she gave no sign that she remarked his entrance. She did not so much as shoot one glance of curiosity towards him. The Prince carried the letter off to his cabinet, while Wogan sat down beside the Countess and looked about the room.

"I have not seen Lady Featherstone this evening," said he.

"Have you not?" asked the Countess, easily.

"Not so much as her foot," replied Wogan.

The conviction came upon him suddenly. Her hurried journey to Bologna and her presence at Ohlau were explained to him now by her absence from the room. His own arrival at Bologna had not remained so secret as he had imagined. The fragile and gossamer lady, too flowerlike for the world's rough usage, was the woman who had spied in his room and who had possessed the courage to stand silent and motionless behind the curtain after her presence there had been discovered. Wogan had a picture before his eyes of the dagger she had held. It was plain that she would stop at nothing to hinder this marriage, to prevent the success of his design; and somehow the contrast between her appearance and her actions had something uncanny about it. Wogan was inclined to shiver as he sat chatting with the Countess. He was not reassured when Lady Featherstone boldly entered the room; she meant to face him out. He remarked, however, with a trifle of satisfaction that for the first time she wore rouge upon her cheeks.

Wogan, however, was not immediately benefited by his discovery. He knew that if a single whisper of it reached the Prince's ear there would be at once an end to his small chances. The old man would take alarm; he might punish the offender, but he would none the less surely refuse his consent to Wogan's project. Wogan must keep his lips quite closed and let his antagonists do boldly what they would.

And that they were active he found a way to discover. The Countess from this time plied him with kindness. He must play cards with her and Prince Constantine in the evening; he must take his coffee in her private apartments in the morning. So upon one of these occasions he spoke of his departure from Ohlau.

"I shall go by way of Prague;" and he stopped in confusion and corrected himself quickly. "At least, I am not sure. There are other ways into Italy."

The Countess showed no more concern than she had shown over her harp-string. She talked indifferently of other matters as though she had barely heard his remark; but she fell into the trap. Wogan was aware that the Governor of Prague was her kinsman; and that afternoon he left the castle alone, and taking the road to Vienna, turned as soon as he was out of sight and hurried round the town until he came out upon the road to Prague. He hid himself behind a hedge a mile from Ohlau, and had not waited half an hour before a man came riding by in hot haste. The man wore the Countess's livery of green and scarlet; Wogan decided not to travel by way of Prague, and returned to the castle content with his afternoon's work. He had indeed more reason to be content with it than he knew, for he happened to have remarked the servant's face as well as his livery, and so at a later time was able to recognise it again. He had no longer any doubt that a servant in the same livery was well upon his way to Vienna. The roads were bad, it was true, and the journey long; but Wogan had not the Prince's consent, and could not tell when he would obtain it. The servant might return with the Emperor's order for his arrest before he had obtained it. Wogan was powerless. He sent his list of names to Gaydon in Schlestadt, but that was the only precaution he could take. The days passed; Wogan spent them in unavailing persuasions, and New Year's Day came and found him still at Ohlau and in a great agitation and distress.

Upon that morning, however, while he was dressing, there came a rap upon his door, and when he opened it he saw the Prince's treasurer, a foppish gentleman, very dainty in his words.

"Mr. Warner," said the treasurer, "his Highness has hinted to me his desires; he has moulded them into the shape of a prayer or a request."

"In a word, he has bidden you," said Wogan.

"Fie, sir! There's a barbarous and improper word, an ill- sounding word; upon my honour, a word without dignity or merit and banishable from polite speech. His Highness did most prettily entreat me with a fine gentleness of condescension befitting a Sunday or a New Year's Day to bring and present and communicate from hand to hand a gift,—a most incomparable proper gift, the mirror and image of his most incomparable proper friendship."

Wogan bowed, and requested the treasurer to enter and be seated the while he recovered his breath.

"Nay, Mr. Warner, I must be concise, puritanical, and unadorned in my language as any raw-head or bloody-bones. The cruel, irrevocable moments pass. I could consume an hour, sir, before I touched as I may say the hem of the reason of my coming."

"Sir, I do not doubt it," said Wogan.

"But I will not hinder you from forthwith immediately and at once incorporating with your most particular and inestimable treasures this jewel, this turquoise of heaven's own charming blue, encased and decorated with gold."

The treasurer drew the turquoise from his pocket. It was of the size of an egg. He placed it in Wogan's hand, who gently returned it.

"I cannot take it," said he.

"Gemini!" cried the treasurer. "But it is more than a turquoise, Mr. Warner. Jewellers have delved in it. It has become subservient to man's necessities. It is a snuff-box."

"I cannot take it."

"King John of Poland, he whom the vulgar call Glorious John, did rescue and enlarge it from its slavery to the Grand Vizier of Turkey at the great battle of Vienna. There is no other in the world —"

Wogan cut the treasurer short.

"You will take it again to his Highness. You will express to him my gratitude for his kindness, and you will say furthermore these words: 'Mr. Warner cannot carry back into Italy a present for himself and a refusal for his Prince.'"

Wogan spoke with so much dignity that the treasurer had no words to answer him. He stood utterly bewildered; he stared at the jewel.

"Here is a quandary!" he exclaimed. "I do declare every circumstance of me trembles," and shaking his head he went away. But in a little he came again.

"His Highness distinguishes you, Mr. Warner, with imperishable honours. His Highness solicits your company to a solitary dinner. You shall dine with him alone. His presence and unfettered conversation shall season your soup and be the condiments of your meat."

Wogan's heart jumped. There could be only one reason for so unusual an invitation on such a day, and he was not mistaken; for as soon as the Prince was served in a little room, he dismissed the lackeys and presented again the turquoise snuff-box with his own hands.

"See, Mr. Wogan, your persuasions and your conduct have gained me over," said he. "Your refusal of this bagatelle assures me of your honour. I trust myself entirely to your discretion; I confide my beloved daughter to your care. Take from my hands the gift you refused this morning, and be assured that no prince ever gave to any man such full powers as I will give to you to- night."

Wogan's gratitude well-nigh overcame him. The thing that he had worked for and almost despaired of had come to pass. For a while he could not speak; he flung himself upon his knees and kissed the Prince's hand. That very night he received the letter giving him full powers, and the next morning he drove off in a carriage of his Highness drawn by six Polish horses towards the town of Strahlen on the road to Prague. At Strahlen he stayed a day, feigning a malady, and sent the carriage back. The following day, however, he took horse, and riding along by-roads and lanes avoided Prague and hurried towards Schlestadt.

He rode watchfully, avoiding towns, and with an eye alert for every passer-by. That he was ahead of any courier from the Emperor at Vienna he did not doubt, but, on the other hand, the Countess of Berg and Lady Featherstone had the advantage of him by some four days. There would be no lack of money to hinder him; there would be no scruple as to the means. Wogan remembered the moment in his bedroom when he had seen the dagger bright in the moon's rays. If he could not be arrested, there were other ways to stop him. Accidents may happen to any man.

However, he rode unhindered with the Prince's commission safe against his breast. He felt the paper a hundred times a day to make sure that it was not stolen nor lost, nor reduced to powder by a miracle. Day by day his fears diminished, since day by day he drew a day's journey nearer to Schlestadt. The paper became a talisman in his thoughts,—a thing endowed with magic properties to make him invisible like the cloak or cap of the fairy tales. Those few lines in writing not a week back had seemed an unattainable prize, yet he had them; and so now they promised him that other unattainable thing, the enlargement of the Princess. It was in his nature, too, to grow buoyant in proportion to the difficulties of his task. He rode forward, therefore, with a good heart, and one sombre evening of rain came to a village some miles beyond Augsburg.

The village was a straggling half-mile of low cottages, lost as it were on the level of a wide plain. Across this plain, bare but for a few lines of poplars and stunted willow-trees, Wogan had ridden all the afternoon; and so little did the thatched cottages break the monotony of the plain's appearance, that though he had had the village within his vision all that while, he came upon it unawares. The dusk was gathering, and already through the tiny windows the meagre lights gleamed upon the road and gave to the falling raindrops the look of steel beads. Four days would now bring Wogan to Schlestadt. The road was bad and full of holes. He determined to go no farther that night if he could find a lodging in the village, and coming upon a man who stood in his path he stopped his horse.

"Is there an inn where a traveller may sleep?" he asked.

"Assuredly," replied the man, "and find forage for his horse. The last house—but I will myself show your Honour the way."

"There is no need, my friend, that you should take a colic," said Wogan.

"I shall earn enough drink to correct the colic," said the man. He had a sack over his head and shoulders to protect him from the rain, and stepped out in front of Wogan's horse. They came to the end of the street and passed on into the open darkness. About twenty yards farther a house stood by itself at the roadside, but there were only lights in one or two of the upper windows, and it held out no promise of hospitality. In front of it, however, the man stopped; he opened the door and halloaed into the passage. Wogan stopped too, and above his head something creaked and groaned like a gibbet in the wind. He looked up and saw a sign-board glimmering in the dusk with a new coat of white paint. He had undoubtedly come to the inn, and he dismounted.

The landlord advanced at that moment to the door.

"My man," said he, "will take your horse to the stable;" and the fellow who had guided Wogan led the horse off.

"Oh, is he your man?" said Wogan. "Ah!" And he followed the landlord into the house.

It was not only the sign-board which had been newly painted, for in the narrow passage the landlord stopped Wogan.

"Have a care, sir," said he; "the walls are wet. It will be best if you stand still while I go forward and bring a light."

He went forward in the dark and opened a door at the end of the passage. A glow of ruddy light came through the doorway, and Wogan caught a glimpse of a brick-floored kitchen and a great open chimney and one or two men on a bench before the fire. Then the door was again closed. The closing of the door seemed to Wogan a churlish act.

"The hospitality," said he to himself, "which plants a man in the road so that a traveller on a rainy night may not miss his bed should at least leave the kitchen door open. Why should I stay here in the dark?"