RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

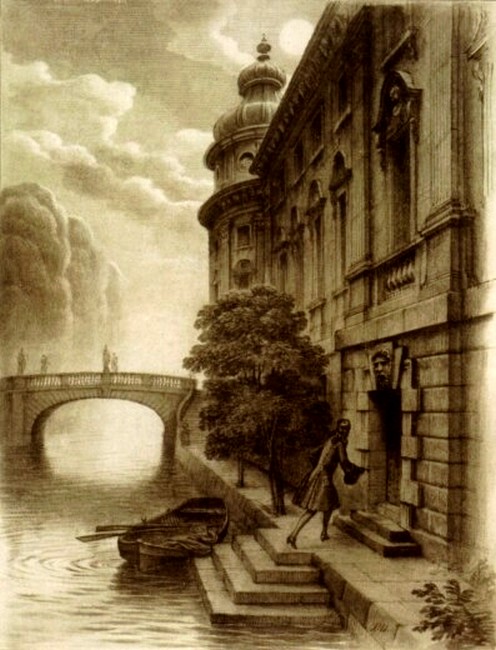

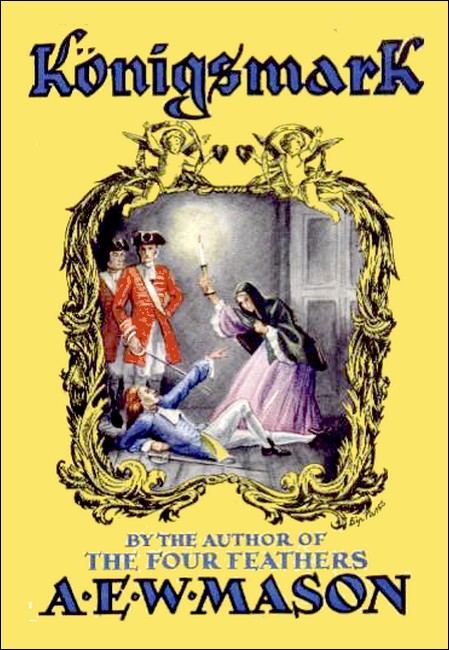

"Königsmark," Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1938

Title page by Rex Whistler

Philipp Christoph von Königsmark (1665-1694)

and Sophia Dorothea von Celle (1666-1726)

Chancellor Schultz leaned comfortably back in his cushioned chair and crossed his fat little legs. He laid his fat little hands side by side and palms downwards on the big mahogany table in front of him. He slid them apart over the polished surface to the full reach of his arms. Not a paper remained to reproach him. It was half-past eleven by the gilded clock against the wall. In a few minutes Duke George William, with his huntsmen and his dogs and his horns, would come clattering back from the moorlands. The day's work was over and, for Chancellor Schultz, his life's work too. The tablets of his service were clean now, and he was pleased to think that, though much written upon during twenty years, they had never been smudged.

He took a pinch of snuff, inhaled it slowly and struck a bell upon the table.

"Theodore," he said to the footman who answered it, "will you please tell Councillor Bernstorff that I shall be happy if he will spare me a few minutes."

But he wouldn't be happy. Chancellor Schultz was never even comfortable with Councillor Bernstorff. Councillor Bernstorff was suave but secret. He wanted to jostle and push. He pined for things to happen. Now for Chancellor Schultz the flash of those pigeons burnished by the sunlight as they swooped down from the cupolas above the Castle's yellow walls to the alley of lime- trees beyond the rusty old bridge over the moat—that was all that he wanted to see happening in the Duchy of Celle. However, Bernstorff was clever—and there was no one else. Only—and a little spasm of doubt shook the Chancellor, not for the first time, in the wisdom of his choice of a successor—there was the shape of the ferret in Councillor Bernstorff's face, a sharpness to the cheek-bones, a needle-point to the nose, which his experience had taught him to link with a passion for land. Never had Councillor Bernstorff breathed a word to justify the Chancellor's suspicion. He was, in every detail of his conduct, the mere industrious servant of the Chancery, modest in his outlook, frugal in his life. Yet Schultz nursed that suspicion and shook his head over it. A landless man hungry for land—who else in the world was so liable to the bribe? And what bribe could equal the feel of your very own clods of solid earth beneath the sole of your foot? But—but—there was no one else.

Chancellor Schultz heard the light tread of Bernstorff in the corridor and hurriedly adjusted his heavy peruke upon his bald head. This was an important moment in the simple history of Celle—though how important neither he nor anyone else could on that summer day foresee—and Councillor Bernstorff was a stickler for ceremony.

Bernstorff entered discreetly, a thin, tall young man in his twenty-eighth year, austere and correct from his top-knot to his heels. He bowed to his chief.

"Sit down, Bernstorff." The Chancellor pointed to a chair and Bernstorff sat on the edge of it. "What devilish thin knees the fellow has!" Schultz reflected discontentedly. "But there's no one else."

Aloud he said: "This afternoon His Highness will hand over to you the seals of the Duchy."

For a few moments Bernstorff stared at the Chancellor with incredulous eyes. Then the blood mounted slowly up his long neck into his cheeks.

"Your Excellency resigns?" he asked, subduing his voice to the hush which fits calamities. Inwardly he was saying to himself, "So the old fool's going at last and high time too!" And he himself was going to move from his dark little office in the Court, overshadowed by the big lime-tree, into this spacious room which, across alleys of cedars and lawns smooth as emeralds, commended and surveyed the town.

"I shall make some changes in the furniture," Councillor Bernstorff let his thoughts run on. "I'll have that fine table against the window, so that the light may fall over my left shoulder. Not that I mean to write much more than my name in the future. But I don't like doors behind me. And I'll have the great clock opposite so that I can't but see it when I raise my head and know if I'm wasting a minute."

There would be corresponding changes outside the great window. To use a phrase not coined in the year 1680, Councillor Bernstorff meant to put the Duchy of Celle on the map, and himself with it. In the great carpet of Germany, as it was patterned then, Celle never caught the eye, so quiet was its colour. Other principalities, Brandenburg, Saxony, Hanover—yes, even Hanover, Celle's little next-door neighbour—claimed all the attention. They glittered with jewels and fine clothes, even if the villages were dark and the villagers hungry. They were noisy with entertainment and, by the way, loud eating. They had country palaces and parks laid out on the model of Versailles. Had not Herrenhausen the highest fountain in Europe which flung a jet of water one hundred and forty feet high into the air? They sparkled, these Duchies, and if from time to time the sheen wore thin and offered a glimpse of dark passions and secret crimes—why, an astute Chancellor might easily turn such things to his profit. Whilst here, on the edge of these excitements and possibilities, Celle slept—placed, patriarchal, an everlasting Sunday afternoon!

At this point in his reflections Councillor Bernstorff was startled and alarmed. Schultz was talking: and after all he still had the seals of his office in his keeping. It would not be that the old fool was reading his thoughts as if they were printed in an open book. Yet he was saying: "Celle was not always this quiet and contented little Paradise. When I first became Chancellor, there were speeches at the street corners, deputations to the Palace, refusals to pay taxes, plots of revolution, such a pother and uproar as no man can imagine today. His Highness was squandering the revenues with Madame Buccolini in Venice. He could make the money fly in those days, I can tell you! Talk of the Doge marrying the Adriatic once a year. The Duke and his young brother, Ernest Augustus, the Bishop, married all Venice twice a night and with something more than a golden ring."

Councillor Bernstorff sat back in his chair. Chancellor Schultz was only musing contentedly over the twenty-five years of his service. Duke George William had yielded to the remonstrances of his people He had returned and had dutifully offered his hand to Sophia of Bohemia and, unable to face so incongruous a match, had passed her on to his brother at a price.

"We were well quit of that good woman," said Schultz.

"She is the granddaughter of an English King," Bernstorff returned, shocked at so disparaging a phrase.

"And always aware of it," said Schultz drily.

"She is a philosopher, learned, and the friend of philosophers," declared Bernstorff.

"She has also the tongue of a fishwife," said Schultz.

"Certainly she has used harsh phrases," Bernstorff admitted reluctantly. "But it would have humiliated even a lady of less degree than the Duchess Sophia to be handed from brother to brother with a handsome gift as the price of taking her."

Councillor Bernstorff was on delicate ground, for the harsh phrases by which term he mitigated the lady's Billingsgate, were all directed at the household of Celle.

"It was too big a price besides," Bernstorff added regretfully. For himself he would have liked to see the ceremonious and arrogant Sophia, the friend of Descartes and Leibnitz, and a possible Queen of England, Duchess of Celle instead of Duchess of Hanover. "First a promise by Duke George William that he would never marry..."

"Ah! That promise was broken," said Schultz with a smile.

"At a big price too," Bernstorff retorted.

"One gets nothing from Hanover, my friend, except at a big price. You will do well to remember that," Schultz replied.

He was smiling. To his thinking the price had been well worthwhile. His musing had taken him back to the happy hour at Breda when the brown curls and flashing beauty of Eleonore d'Olbreuse, the young French Lady-in-Waiting to the Princess of Tarente, had netted the susceptible heart of George William, Duke of Celle, for good and all. A morganatic marriage had followed, a year later the beautiful Sophia Dorothea was born and Schultz's fifteen years' fight for the legitimisation of the mother and the daughter had begun. He was hampered by the opposition of Hanover, the greed of its Duke and the hatred of Duchess Sophia. But step by step he had won his way. Eleonore d'Olbreuse became Madame de Harburg, Madame de Harburg became Countess of Wilhelmsburg, and Sophia Dorothea, when she married, would have the right to emblazon her note-paper with the Royal Arms of Brunswick. Finally, a delay in the supply of troops to the Emperor Leopold brought that hesitating man to a decision, and just four years before this day when Chancellor Schultz surrendered his office, the Emperor's Envoy had attended the ceremonious re-marriage of Duke George William with his wife, had greeted her as Your Highness, and Sophia Dorothea, then a girl of ten years, as Princess. So Chancellor Schultz pleasantly recollected and still Councillor Bernstorff protested: "But the price was too high. Her Highness cannot inherit—no, neither she nor the Princess. When the Duke dies, the Duchy is joined with Hanover."

"Yes," Schultz agreed. "Yet there has been some advantage in that hard bargain. His Highness set himself to save. There has been no French company of players sucking the blood of Celle, no Italian Opera, no carnivals, no masked balls, no mistresses sparkling with other women's tears. A careful husbandry, instead, my friend Bernstorff. A home-spun prosperity in which all Celle has shared. And meanwhile a great fortune has been built up for Her Highness and her daughter. The Princess Sophia Dorothea! There's not a Prince from one end of Germany to another but would think himself blessed if her pretty hand would rest in his."

The Chancellor had thus good reason for his complacency. He was looking backward. Bernstorff on the other hand was looking ahead.

"And which of them will it be?" he asked with every appearance of nonchalance.

Schultz shrugged his shoulders.

"She will choose for herself. You are shocked, my friend? Then you will find much to shock you in the pleasant State of Celle. A husband who loves his wife. A wife who is content with her home. A daughter who at fourteen is still a child, with a child's longings and a child's pleasures. In God's good time she will make her choice. It may be young Augustus William of Wolfenbüttel. Let us hope that it will be."

August Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel (1662-1731)

Bernstorff shook his head doubtfully over that prospect and Schultz rallied him with a laugh.

"What, you too? Because the elder brother, betrothed too soon, dies in battle, the younger must not take his place? Superstition, Bernstorff. Beware of it! However, there is time and to spare. Let nature have her way!"

"Nature?" Bernstorff repeated. "At fourteen women are ripe for marriage."

"And at fifteen they are ripe for death. Let the Princess Sophia Dorothea play for a little while longer with her dolls."

"And amongst them," said Bernstorff slowly, "with Philip Christopher von Königsmark?"

The Chancellor sat upright in his chair. He stared at his companion.

"Philip Christopher Königsmark?" he repeated. "The page?"

"The page," said Bernstorff, nodding his head.

After that there fell a silence upon the room. That Bernstorff had some show of reason for what he said, Schultz could not doubt. All his complacency ebbed away from him. So much forethought he had taken to safeguard the little realm to which he had given every beat of his loyal heart, to stop every crevice through which an untimely wind could creep. And here suddenly was a danger which he had never taken into account.

IT was the custom in those days for the cadets of noble families to complete their education as pages in Ducal or Imperial Courts. In neighbouring Sweden, no family shone with a brighter lustre than that of old John Christopher Königsmark who had captured Prague in 1648 and recovered the famous Silver Book of Bishop Ulphilas. His descendants had stamped their names on every battlefield in Europe and left some fragrance of their passage in every boudoir. Great soldiers and great lovers, remarkable for the beauty of their features and the rare distinction of their manners, they would have been fabulous if they had not been real. Homeric stories were told of them and the stories were true. Charles John, swimming with his sword between his teeth, had captured a Turkish galley single-handed. He was the only Protestant who had ever been made a Knight of Malta. A girl of high family in England fled from her home and camped with him as his page from Vienna to the gates of Constantinople. Wherever there were battles to be fought, or women to be loved, one of that family ran, bright and ruinous like a flame through standing corn.

And here was a sprig of that breed in the quiet Court of Celle, where the greatest heiress of the day twisted her father round her child's finger and delighted her adoring mother by the quickness of her wits and the liveliness of her spirit. He, Schultz, should have known the danger and prevented it. He sat blaming himself: and the brightness of the day was dimmed. The very silence of the room became an oppression. It seemed to him that shadows were gathering in the corners, taking unto themselves life, an evil life, which spread like a miasma through the kindly Palace, setting it out as a scene fit for darkness and unknown horrors.

Chancellor Schultz shook his shoulders violently. He got up from his chair and walked quickly across the room. As he gazed out through the open window, the wide, orderly space of lawn and alley, sleeping in the sunlight, calmed the trouble of his spirit. From the market-place beyond the church a drowsy peaceful hum reached to his ears, and away upon his right hand, he could hear the river Aller singing pleasantly over its stones at the bottom of the French garden. He grumbled at the ease with which he had let these dark and foolish fancies capture him.

"It's high time I went," he said to himself. "I'm getting old, and old men make catastrophes out of cobwebs. A page? A page can be sent away and the State still stand upright." He laughed and returned to his seat.

"Let me hear this desperate story of the page and the Princess, my good Bernstorff."

"There is to be an entertainment in the theatre on the occasion of Her Highness' birthday," said Bernstorff. "There will be interludes, recitations, songs by the citizens of Celle for the citizens of Celle."

Bernstorff could not check the sniff of disdain. In the Castle of Celle, high up on the top floor, was the most adorable little theatre in the world, a place of white and gold, lit by candles in glass candelabra—the daintiest little band-box of a theatre, perfect for a witty comedy played by that French company at Hanover or for a charming operetta sung by that Italian troupe at Hanover. Here the burghers of the town, stiff in their best clothes, were to profane its daintiness with their uncouth gestures and clumsy speech. Of all the dreary entertainments conceivable, nothing to Bernstorff's thinking could equal the amateurish efforts of bumpkins dressed in clothes of their own making. And there would be three hours of it—three, eternal, tedious hours. Bernstorff grew so hot in his anticipation of them that he forgot his reason for mentioning them.

Chancellor Schultz brought him back to it.

"After all I am still Chancellor," he reflected. "I must make sure that there is some body in this story. If there is none, Bernstorff must whistle for his appointment. Shall I tell him about Stechinelli?"

Aloud he said: "There is nothing new in such entertainments."

"There is to be an item which is new," Bernstorff returned.

"It will be the less popular," said Schultz.

Bernstorff leaned forward, nodding his head to underline his words.

"There is to be a scene out of a new play."

"Excellent!" said Schultz.

"The play is by Racine."

"I have never heard of him," remarked Schultz.

Bernstorff sat up in his chair and observed coldly: "He is held in great esteem by King Louis of France."

"That is probably why," said Schultz.

There were moments when Bernstorff was profoundly shocked by the Boeotian contentment of his superior Minister. Louis was an enemy no doubt, but he was by universal recognition the arbiter of taste and patron of letters. However, with ignorance so abysmal, there could be no argument.

"The scene is to be acted by the Princess Sophia Dorothea and Philip Königsmark, a page."

"But not a lackey," answered Schultz. "We will not forget that in the veins of the Königsmarks flows the royal blood of Pfalz and Nassau."

Bernstorff went about on another tack.

"It is a passionate love scene."

"To be played by babies," said Schultz. "It should be amusing."

"It is being rehearsed daily with fervour," objected Bernstorff. "I have stood once or twice under the gallery at the back of the theatre and listened."

Schultz was now a little more impressed than he wished to be or cared to show.

"Moreover the play's motive is the old fable of Iphigenia. Iphigenia is to be sacrificed with the acquiescence of her father. The scene is the one in which Achilles-Königsmark or shall we say Königsmark-Achilles seeks to dissuade the Princess Sophia-Iphigenia from her proper obedience."

Schultz twisted uncomfortable in his chair.

"But no doubt Her Highness supervises these rehearsals," he argued.

"She does."

"In that case the fervour you condemn will be no more than the scene requires."

Bernstorff smiled.

"And in fact the dialogue is declamatory," he admitted.

"Well then?

Chancellor Schultz spread out his hands. The choice of the scene may have been unfortunate. But if there was no paddling of hands, no faces cheek to cheek, no knee pressing amorously against knee, there was no great harm done—nothing at all events to make all this pother about.

But Bernstorff had not finished.

"The rehearsals are discreet. But they have brought two young people, both of unusual beauty, into a close acquaintanceship. The rehearsals under supervision have inspired a desire for meetings under no supervision at all."

"And such meetings take place?"

"Every day," said Bernstorff.

Schultz drew a long breath.

"I should have been told of this," he said, but he had no doubt why he had not been told. Bernstorff would wish to make his assumption of high office memorable by some lightning stroke which would set his master in his debt.

"One of these days," he added thoughtfully, "I shall have to tell you about Stechinelli. Meanwhile, where do these meetings take place?"

"In the chapel of the Palace," Bernstorff replied. He explained with a note of acrimony in his voice: "A lime-tree grows in front of my office window. It darkens the room, which is inconvenient, but it makes a screen through which no one outside can look. Across the Court is the chapel and the entrance to the chapel is from the Court."

"Well?" said Schultz.

"At six o'clock in the afternoon Philip Königsmark comes alone to the courtyard. He comes carelessly, sauntering, with an eye upon the windows. As soon as he thinks that no one is overlooking him, he slips into the chapel. And there he waits. He waits in His Highness' gallery with the latticed windows. If you followed him in, a trifle surprised at so much devotion in a boy so modish, as I once did, you would see no one, you would hear no one. You would believe the chapel to be empty.

"And it is empty," Schultz insisted.

"Until the Princess comes. She may come soon. She may not come for an hour. But in the end—yes, the Princess brings the sins of her fourteen years to the same throne of grace," and Bernstorff laughed with satisfaction in the neatness of his phrases.

Schultz did not laugh. He was as glum as a man could be.

"And they stay long?" he asked.

"Half-past-seven is the hour for supper, as Your Excellency knows," Bernstorff replied, "and young Königsmark must stand upon his duties behind His Highness' great chair. But he comes to the chapel already dressed."

"And doubtless," Schultz continued—and the irony had passed now from Bernstorff's voice into his, "you have been able, from that dark room which you are to exchange for mine, to hear something of their talk, perhaps to observe something of their conduct."

Bernstorff's sallow face flushed a dark red.

"My duty," he began, "bade me forget my dignity."

"You hid yourself," Chancellor Schultz translated bluntly.

"In the pulpit," Bernstorff admitted. "The young couple sat said by side on the chairs beneath me. It was—inconvenient. I suffered sharply from the cramp."

Chancellor Schultz was not sorry to hear that. He permitted himself even to utter a little grunt of pleasure. It was indeed the only tiny morsel of pleasure to be extracted from the whole of this untimely episode.

"You heard them then?"

"Yes, I heard them," said Bernstorff and he tittered at the absurdity of the conversation to which, with the cramp in his calves and the cold stone of the pulpit bruising his knees, he had been compelled to listen for a good half-hour.

"They talked like children, if indeed ever were children so serious. They were going to break down the barriers—he of course with a flashing sword whilst she waited. Together they were going to do noble things—they were not quite sure what—but things which would make a lovelier world for other people—"

"Yes, yes, yes," Schultz interrupted roughly. Young people had dreams and were all the better for them. He felt uneasy, and a little ashamed at hearing their dreams profaned, ridiculed, made silly. He shook himself as if his clothes hung uncomfortably upon his limbs. Let the children laugh at their fine imaginings when they had grown up—but no one else, certainly not Chancellor Schultz who had many faults to reproach himself with, and certainly not Councillor Bernstorff who had more. They were sacred—the dreams of children—however quickly they might tarnish and fade. "And that was all?"

Bernstorff smiled.

"They were all soul," he said summing up the conversations, "waiting unconsciously for the spark which would reveal to them that they were also—all body."

And again Schultz was silent. The sentence was like a blow between the eyes. There was too much force and truth in it for argument. Yes, the moment would come, the spark would kindle and pass from one to the other. He looked at Bernstorff and nodded his head. It was a gesture of surrender.

"We are in time," he said drawing a breath of relief. "We are in time."

At that moment with a blare of horns, a great barking of dogs and a clatter of hoofs, Duke George William and his huntsmen swirled joyously into the courtyard.

Her Serene Highness, the Duchess of Celle, began to doubt her wisdom in selecting a scene from the Tragedy of Iphigenia at just the same time as did Chancellor Schultz. She was sitting in a small three-cornered room at the top of the Castle's southern tower. The ceiling and walls were heavily decorated with golden images of the acanthus flower, but it had the homely and comfortable look of a parlour much in use. One of its windows commanded the park with its smooth beech trees and its grass as smooth; the other looked down a slope to the French garden of trim yew shrubs and glowing beds of flowers and horn- beam hedges, with a round pond in the middle, which shone in the sunlight like a mirror. Perronet had laid out that garden for her so that she might have at her elbow a piece of her native Poitou, but she had no eyes for it this morning. Neither for the garden nor the strip of embroidery which lay upon her knee.

She was forty-one years old in this summer; and whilst the beauty which had long ago captured Duke George William had ripened, she had gradually added to it a serene dignity exactly fitted to her new title and advancement. To Duchess Sophia over at Hanover she was "a little clot of dirt"—to her own people of Celle she was a Queen in the right of her devotion to their prosperity and happiness. However, there was very little of stateliness in her look at this moment. She was watching her young daughter with a loving amusement which waited only for an exclamation to break into a laugh.

"In trouble, darling?" she asked.

Sophia Dorothea, her feet drawn back under her chair, was bending over a copy-book and breathing heavily. Her dark brows were drawn together in a frown. She put down a word and crossed it out again and sucked her pencil and looked at the printed copy of Iphigenia, which lay beside the copy-book and finally threw the pencil down and sat up in her chair.

"Mother, let's talk treason. German—is—a—barbarous language." Her young voice rang out clear as the sound of a bell. She challenged the world to contradict her.

Duchess Eleonore stifled a laugh—a laugh which condoned the treason and was rather inclined to admit the pronouncement.

"Sh! Sophia, my angel. German is the language of philosophy. It is the language of sentiment. It is the language of romance. Fourthly and lastly, as our dear rector says in the pulpit, it is the language of your father. Continue to translate."

"Mother, I can't do it," and suddenly the girl threw back her head and began to recite her lines in French. It was while she recited that Eleonore began to wonder whether she had been wise. Sophia Dorothea was fourteen years old and a lovely child. A mass of black burnished hair, with here and there the dark blue tint of a wild-duck's wing, rippled in curls about a face delicate in its features and joyous in its expression. She was a creature of flame, alert in a world of delight and responsive on the instant to every flicker of sunlight, to the perfume of every flower. An Ariel with a sense of fun. A spirit with a ripple of laughter.

But now she recited:

"Partez; ŕ vos honneurs j'apporte trop

d'obstacles.

Vous-męme dégagez la foi de vos oracles

Signalez ce héros ŕ la Grčce promis;

Tournez votre douleur

contre ses ennemis.

Déjŕ Priam pálit; déjŕ Troie en

alarmes

Redoute mon bűcher, et frémit de vos larmes.

Allez; et, dans ces murs vides de citoyens,

Faites pleurer ma

mort aux veuves des Troyens.

Je meurs, dans cet espir,

satisfaite et tranquille.

Si je n'ai pas vécu la compagne

d'Achille,

J'espčre que du moins un heureux avenir

A vos

faits immortels joindra mon souvenir;

Et qu'un jour mon

trépas, source de votre gloire,

Ouvrira le récit d'une si

belle histoire."

As the child's fresh voice died away leaving its music lingering for a moment in the air, her dark eyes rested upon a very troubled face. Sophia Dorothea was not asking for applause, nor did she ask why her mother was so moved. For though she could not put it into words, she understood. And for the first time that she could remember, there had risen an embarrassment between them which held them both speechless. The embarrassment deepened when the mother dropped her face in her hands and a little dry sob burst from her lips. Eleonore had expected something rhythmical, a piece of elocution, a just emphasis; and she had heard the hard glitter of Racine softened, its rhetoric made human and touched with tenderness and sorrow. Iphigenia facing death that her father might not be ruined and shamed. Iphigenia bidding farewell to her lover and praying for his triumph, and whispering her longing that, though she were dead, her name might be linked eternally with his—Iphigenia was here, in this little room above the park and the French garden of Celle Castle. Eleonore was shocked as she listened. It was not only Sophia Dorothea's voice which tore at the strings of her heart. It was the quiver of her face and the look of submission in her great dark eyes, as of one who had dropped her plummet into life and found it salt with tears.

"My darling," she said, and she was answered by a smile, wistful and tremulous.

For a moment Eleonore dreamed that a changeling had taken the place of that daughter whose every thought she had shared—Sophia Dorothea of the light heart and the light foot, for whom the world was a playground—what had she to do with this—stranger, with passion in the mystery of her eyes, and immolation throbbing desolately in the clear notes of her young voice?

"Sophia, you mustn't take the play as real," she said, stretching out her arm until her hand rested on the girl's. "It's only a fable you know. A fable of old times."

But Sophia Dorothea did not answer the pressure of her mother's hand. Nor did she return it. She sat quite still, the wistful smile touching her lips to tenderness, and vanishing and shining again.

"But it has lived for a thousand years, my mother," she said gently.

"No doubt. Pretty fables do," said the mother unhappily; and now the daughter really smiled. Eleonore had a picture of someone almost drowning and now climbing back on to dry land.

"And after a thousand years Monsieur Racine has made a play of it?"

"Yes," said Eleonore. "And a play which all the world admires."

"Then I think—" Sophia Dorothea did not so much break off as just cease to speak; and seeing the strange look begin to creep back again into her daughter's eyes, Eleonore cried urgently.

"But, darling, what do you think?"

"That since the fable has persisted so long, there must be truth in it."

And so the Duke George William and his huntsmen trampled lustily into the great space before the Castle and the blare of his horns was tossed about the walls. No sound was ever more welcome to Duchess Eleonore. Old heads on young shoulders she distrusted and disliked and pitied; and it was her continuous prayer that this pair of young shoulders in front of her should feel no extra load a moment before the inevitable time. Sophia Dorothea shook back her curls, as she heard the horns, and forgot all her problems.

"Papa!" she cried. She clapped her hands. She was her fourteen years again. "Well, my papa, at all events, won't want to cut my heart out on an altar to make himself more glorious like Agamemnon. I'm sure of that."

It was their custom to join the cavalcade at the Castle door, and to go with Duke George William into his library. There he drank a big stoup of Rhenish wine, before he went off to change his clothes, whilst Sophia Dorothea perched on the arm of his chair: and in the intervals of drinking he described to his enthralled audience the behaviour of his dogs, the line which the quarry had taken, and the special incidents of the morning. Thus half an hour was passed, on which all three of them had come to count.

Eleonore was surprised therefore, on reaching the great door, to find that the Duke had already dismounted and disappeared.

"Is he hurt?" she asked anxiously of a huntsman.

"No, Your Highness. The Chancellor—" but Eleonore did not wait to hear more. She hurried with Sophia Dorothea up the great stone staircase to the first floor and along a corridor to the library. She broke into the room and saw Schultz and Bernstorff standing side by side with grave faces, and the Duke, a little way off, leaning with his elbow on the mantelshelf, and slapping his boot discontentedly with his hunting crop. His lower lip was thrust forward and his red good-humoured face, now growing a little heavy, was dark with annoyance. For a second or two he looked at the newcomers without speaking. Then he crossed the room and took his daughter by the hand.

"Sophia, my dear, there's a stupid piece of business you needn't be bothered with. I'll tell you at dinner about the boar we killed." And he led her out of the room and shut the door. He turned back to his wife.

"Eleonore, Bernstorff, you know, is succeeding our very good Schultz today, and he begins his duties with an awkward little silly occurrence which wants careful handling..."

The Duke was an easy-going soul who loathed any interference with the order of his day. It should run smoothly from its beginning to its close according to its plan. And if any unexpected anxiety dislocated it, he was accustomed like many another man to resent, even more than the anxiety itself, the man who brought it to his attention. But at all events he was not going to be done out of his long drink of Rhenish wine. He struck a bell and only when his goblet was on the table at his side, with the yellow wine sparkling to the rim of it, would he allow the subject to be pursued.

"If only people would be sensible," he grumbled, flinging himself pettishly into his chair. "It's young Königsmark, my dear, and our little Sophia."

"Oh!" cried Eleonore with her hand at her heart. Was this the explanation of the change in her daughter? She could hear that young voice now with its ring of passion and its despairing patience. "Philip and our Sophia?"

"So Bernstorff says. Come, out with your story, Bernstorff."

The new Chancellor told it again, and Eleonore listened with paling cheeks, torn between anger against young Königsmark and sorrow for her girl.

She crossed over to her husband's chair when the story was finished and stood beside it, her hands trembling and the tears drowning her eyes. Duke William patted her hand.

"We mustn't make too much of it. Children playing at grown- ups! But it's got to stop of course. Sophia, with the wealth that we've piled up for her, can nowadays look as high as she likes for a husband. And anyway we have other views for her when her time comes."

Eleonore, with the picture of Sophia's rapt face before her eyes, could not take this mischief as lightly as her husband took it. Yes, it had got to be stopped, but Sophia Dorothea was going to suffer, and with much more than a child's sharp short suffering. Philip was a traitor. He had been welcome as much for the sweetness of his temper as for his good looks. They had treated him as one of their own family, supervised his instruction as much, and for a reward he had opened the gates of pain for their darling to pass through.

"Philip must go home, of course, at once," cried the Duke. "But he must be sent off quietly. There mustn't be talk. I don't want my stiff-backed sister-in-law in Hanover to get her venomous tongue round this story. A fine piece of embroidery she'd make of it. She'd write to the King of England and to her tittle-tattling niece, the Duchess of Orleans, and in a month they'd know all about it with additions from Constantinople to the Hague. There's work for you, Bernstorff"—and Bernstorff started violently at the abrupt address. A look of real fear flashed over his face.

"But of course, Your Highness, I am the first to agree. There must be silence the most complete."

"That's what I'm saying," replied the Duke easily enough. "You must see to it that there's silence."

Bernstorff drew a quiet breath of relief. He had no doubt that he could see to it, and without causing the least inconvenience to His Highness's comfort.

"If Her Highness will keep the Princess at her side for the rest of the day," he said "and the life of the Castle goes on as usual, the affair will be closed by tomorrow morning."

Duke George William was very content to leave the troublesome business to his Chancellor, but Eleonore was a little disturbed. She was indignant with Philip Christopher Königsmark, righteously and justly indignant. He had been disloyal and false. But after all he was only a boy, and boy without malice or unkindness. There was a note in Bernstorff's voice which alarmed her. It was too sinister. It was inhuman. With all their outward sheen, these Duchies were cruel places; and though Celle, under Duke George William and herself held cruelty in horror, was Bernstorff of the same mind she asked herself? He had a kinsman in office in Saxony. Eleonore looked at him closely, and did not like his ferrety sharp face. She moved her eyes to her very good friend Schultz.

"Do you approve?" he asked urgently.

She did not notice Bernstorff pinching his thin lips tightly together, nor the gleam of stark fury in his eyes. But with that one indiscreet question she set alight in him that personal enmity which, marching in a step so exact with his policy, was to destroy her happiness and the work of her life.

Schultz bowed to her with a trifle more of formality than he ordinarily used.

"I have no doubt, Your Highness, of my successor's efficiency."

Of what Bernstorff planned to do, Schultz had no idea, but he had listened to him in the Chancellor's office and for a second time in His Serene Highness's library, and he did not doubt that that subtle man had some scheme worked out to the last detail which would at once solve this difficult little problem and hide it away for good. For himself he had finished. He would dine once more at His Highness's high table in the feudal homely style of Celle and then he would betake himself to the small house which he had prepared on a bank of the Aller, at the edge of the town. A little music, a little reading, a little gossip with old friends in the cafés of the town, and then a quiet passage to whatever Valhalla of the second class was reserved for faithful servants.

But ex-Chancellor Schultz dined at the high table of Duke George William and, much to his confusion, had to listen to a speech made by the Duke extolling his high services during his twenty-five years of office. He had to sit quiet whilst his health was drunk and could not but remark the lofty condescension with which Chancellor Bernstorff raised his glass to his predecessor.

"I really must tell that man about Stechinelli," he said to himself.

Worse still, he had to make a reply without too much pride and too much emotion, and commend his successor to the high consideration of Their Highnesses.

Yet the chief recollection which he retained of that dinner was not of the speech which the Duke delivered, nor of the reply which he himself made, nor of the friendliness of everyone except Bernstorff, nor of Bernstorff's disdain. It was of the boy of fifteen who stood behind the Duke's chair in the Duke's livery. Philip Christopher, Count Königsmark, was for this week on duty during the hour of dinner: and no hint had been given to him that this was his last day of service. No doubt Schultz had seen the lad before. But immersed in his State work, with his dinner eaten often enough from a tray at his elbow in his office, he had not once regarded him. He made up for that lack now, and setting in his thoughts Sophia Dorothea by the side of the boy, he could not but say to himself ruefully: "But for my twenty-five years' work, never were a couple so matched by nature since the Garden of Eden closed its gates."

A mass of brown hair, which was to grow darker with the years, clustered about an open fresh face and curled down to his shoulders. Perukes were never in fashion with any of the Königsmarks. His eyes were dark and, between long black eyelashes, looked out with fire upon the world and found it very good. His red lips and white teeth advertised his health and he had the smile and the laugh of frank enjoyment which would win the good will of a curmudgeon. Philip Königsmark was of the middle height, but slender in figure and supple of movements. He had long legs and the slim hands and feet of a girl. And the Court livery which he wore might have been designed to make the best of him. A velvet coat of an almond green colour piped with a gold cord and ornamented with wide cuffs of black velvet fitted his shoulders and waist like a glove and from the waist spread out in a short square skirt. A cravat of muslin and lace was tied in a great bow round his neck. His waistcoat, breeches and stockings were of white silk and his shoes were of fine black leather with scarlet heels and flashing broad-rimmed buckles of silver. He was, Schultz noticed, certainly dressed with the care and precision which befitted a page or—the thought passed through Schultz's mind—a lover in the presence of his mistress. But as there was nothing of furtiveness or secrecy in his looks, so there was nothing of the petit-maítre nor of the fop in the elegance of his dress. And he was happy. Schultz could not doubt it. Happiness radiated from him like warmth from a fire; and if one or twice in the course of his service, his eyes met those of Sophia Dorothea, there was neither fear nor anxiety in the message they sent.

"However he surely must take his good looks away from Celle," Schultz concluded and he fell to wondering what lot the future held in its secret casket for his beloved Sophia Dorothea. Had he been able to guess, there would have been a very unhappy man sitting for the last time at the Duke's table in the Castle of Celle.

"Young Augustus William of Wolfenbüttel no doubt will marry her," he reflected. "The Duke is a little superstitious, but he will get over his superstition."

There had been a foolish betrothal between Sophia Dorothea and William's elder brother Frederick, when Sophia Dorothea was only ten years old. Frederick had been killed while still in his teens at the siege of Phillipsburg.

"Wolfenbüttel and Celle will be an alliance of old friends, and though Celle must belong to Hanover in the end, Wolfenbüttel, with the Princess's wealth to sustain and develop it, will hold its own."

Thus ex-Chancellor Schultz prosed away to himself, sitting above the salt at His Highness's table and dinner being over, he betook himself to his books and his music in his little house across the Aller.

At half-past five on that same afternoon, Bernstorff was seated in his old office, withdrawn a few paces from the window. The great lime-tree, with its wealth of bough and green leaf darkening the room, hid him securely. For the first time he was glad of it. For he could see the mouth of the passage which led into the Court from Their Highnesses' living quarters as well as the three steps which led up to the chapel door. And yet no one, though his eyes were sharp as a hawk's, could be aware of the still watchman behind the small diamond window-panes.

It was very quiet at this hour in the inner Court of Celle; so quiet, that the flutter of a pigeon's wings in the lime-tree was as startling as a rattle of musketry. There were shadows already upon the walls of the Castle. Bernstorff watched them darken from a film of grey into a solid black; and still no footstep rang upon the pavement. He was seized with a panic. Every afternoon, he had declared, the tryst was kept. Suppose that on this afternoon it was broken, that some vague suspicion had crept into the minds of the culprits, that they were now exchanging their dreams between the horn-beam hedges of the French garden! Bernstorff jumped with indignation at the thought that such a thing could be. They had outwitted him—not a doubt of it, that cunning pair. It was long after six o'clock, he was certain. It must be close upon seven. Why, it was as if young Philip Königsmark had broken a definite promise to him, the Chancellor of the Duchy of Celle—a promise to come and be caught, like a bird in a net. Bernstroff was by now in a fume of anger and apprehension. With what face could he meet his master and say, on the first day of his appointment to his office, "I promised Your Highness a proof. I have none?" He would be set down as a slanderer, a rogue ready to blacken even the young Princess, if, by so doing, he could give himself importance. Suddenly his fears died away. So great was his relief that the Court swam for a moment before his eyes, and he doubted their good news. But what he had seen was there, in the same place, still to see—a flash of green and the flame of a silver buckle on a shoe. For a little while they remained, and then assured that the Court was empty, Philip Königsmark flitted into the open, took the steps of the chapel at a leap, and was gone. His bird with its jewelled plumage was in the net. Bernstorff restrained his impatience now.

"I must give him time," he argued. "An interval between the first arrival and the second is part of the plan. I must find him in his secret place."

In a little while he went to his door. Two soldiers of the Duke's guard were waiting outside it.

"Ludwig Holtz," said Bernstorff.

"Here, Excellency."

"Heinrich Muller."

"Here, Excellency."

Bernstorff looked them over and was satisfied. Both men were middle-aged, strong, loyal, stupid.

"What you see and what you hear tonight, you must have forgotten tomorrow. You must never speak a word of it to your wives nor to your children," he said.

"It is understood," both men replied.

"Good! Now follow me quietly."

He led them by corridors round the Court to that passage from which his green bird had flitted.

"Now quickly and quietly," he said and a moment afterwards they were within the chapel door, the three of them. Bernstorff closed the door with his own hands. There was not the whine of a hinge, not a rattle of the latch. He whispered to Ludwig Holtz:

"Stand on guard here! Let no one enter or go out, whosoever it may be. On your life be it!"

Straight in front of him a flight of steps rose to a narrow gallery behind the Duke's private pew. To his right an arch led on to the floor of the chapel.

Bernstorff with a gesture ordered Muller to wait where he stood and crept on tiptoe under the arch. He was looking now into a small sanctuary as exquisite as a gem chiselled by a Cellini. Its vaulted roof was starred with gold, and the artists of the Netherlands in the meridian of their splendour had decorated its walls. Imaginary portraits at half-length of the Saviour and his Disciples, the Apostles and the Prophets were carved in stone under the galleries and, separating each portrait from its neighbour, were angels playing upon different instruments of music. Below them again were pictures painted upon wood in glowing colours of green and grey, blue and gold, of scenes from the Testaments, the Flood, the struggle of the church to live, the Sins and Virtues, the Last Judgment.

Over the communion table—the doctrine of Celle was Lutheran—hung a great triptych by Merten de Vos representing the Crucifixion in the centre piece, and Duke William the Younger with Celle as the background in one panel and his wife Dorothea of Denmark with the Castle of Copenhagen behind her in the other. Placed high up in the left hand corner so as not to break the symmetry of the building was the organ and on the right-hand side in a diagonal line with Bernstorff stood the pulpit, a work of the early Renaissance, all of it from the scroll work of leaves about the rostrum to the Renaissance Masks on its single pillar carved out of one block of white stone. It was in this pulpit that Bernstorff had suffered so dismally from the cramp in his legs when he was listening to the ingenuous dreams of the young lovers.

There was no sign, however, of either of them in the chapel this evening. But Bernstorff only smiled. The Duke's private pew was to the left above his head—a great opera box rather than a pew, shut apart by a row of small latticed casements from the rest of the chapel. Two or three of these casements stood open, but no one at that vantage could see the arch under which Bernstorff stood, without leaning out, and no one was leaning out.

But he had his green bird safe in his net. There was not a mesh which would let him through again, until the fowler so willed it. He crept back to the main door where the narrow staircase mounted to a corridor behind the Duke's box. Beckoning Muller to follow him, Bernstorff went up the stairs as silently as a cat. He stationed Muller at the head of the staircase and stole along by himself to the door. He opened it quickly but without violence, and tasted at once a keen new pleasure.

Philip Königsmark started forward, his lips parted, his heart in his eyes, his hands stretched eagerly out. But at the sight of Bernstorff he stopped with a gasp. The joy died out of him, and then slowly there spread over his face a look of terror, and his knees shook. Never in his life before had Bernstorff seen anyone afraid of him. His pleasure was sharp, and all the sharper because the one afraid was this gay young spark with the fine clothes and the great name and the delicate breeding.

Bernstorff passed his tongue over his lips.

"I am not the friend whom Count Königsmark expected," he said smoothly, but the boy had recovered his poise.

"I expected no friend, Your Excellency," he said in a quiet grave voice.

"Indeed?" cried Bernstorff ironically. "I interrupt your devotions, then? So much piety in so pretty a youth—admirable—admirable." He paused, but no reply came, no, not so much as a look of disdain for the clumsiness of his pleasantry.

"At the same time, modesty should go with worship. You choose for your orisons that part of the church which is reserved for His Highness and His Highness's family. What have you to say to that, my young gentleman?"

Again the sarcasm broke in fragments against the wall of the boy's quiet gravity.

"I have no right to be here, sir," Philip Königsmark agreed.

Bernstorff was making no progress in this style of attack. Even to himself the banter sounded crude, unworthy of his office and quite unhelpful into the bargain. He was all the more wrathful with the boy who withstood him.

"Let us have done with this quibbling," he cried in a rage, though who was quibbling except himself, not his greatest sycophant could have discovered. "Every night you come secretly to this chapel at six o'clock. Every night you wait hidden in this little room for half an hour—"

Did he see the boy flinch? The shadows were gathering in the shrine of grey and green and gold beyond the casements. Within the casements twilight had already fallen.

"And after half an hour—" Bernstorff continued only to be interrupted by a loud passionate cry.

"No! No!"

"And after half an hour, another step falls ever so lightly on the stone floor below, and the tryst is kept," the Chancellor insisted.

Königsmark's hands fell to his side. He had been watched, then! These secret meetings, so treasured, so sacred, which made a long summer's day no more than an attribute of one wondrous hour, had been spied upon, talked of! He had a feeling that some very precious and delicate thing had been soiled by a touch from which it would never get clean.

"Whatever blame there is, is mine alone—" Philip began, and Bernstorff broke in upon him, savagely: "Whatever blame!"

For a moment there was silence, and then Philip resumed.

"I do not wish to make light of it. I only claim that from beginning to end it is mine."

Philip Königsmark spoke quite simply, meaning each word. He was a year older than Sophia Dorothea. If he could not stifle the passion which the sight of her, the sound of her lovely voice, the chance touch of her hand, the mockery of her high spirits and quick wit awakened in him, he should at all events have been able to conceal it. He reasoned like the boy he was, but very solemnly and seriously. He was by a year the elder of the two, and the year condemned him. But in truth neither of the two could have fixed on the moment when the barriers fell down. Neither could have told who spoke the first trembling word, and who the second. A miracle happened. The world turned gold. They fell into step upon a magic path.

"The crime is treason," said Bernstorff bluntly; and in spite of his efforts to hold himself with dignity, the boy in front of him shivered.

"Treason?" he asked, with a quick indraw of his breath.

"Of course," said Bernstorff, with a testy impatience that anyone could be so stupid as to doubt a fact so evident. The blood of reigning Dukes was sacred, a fountain to be guarded like the spring of Egeria with rites and punishments. Treason it was for any youth of lesser rank to profane it; and the penalties of treason were savage and secret.

"You will not be seen again in Celle," Bernstorff continued. "When the Castle is all asleep you will be—removed. Until then you will remain a prisoner here."

What did they mean to do with him? They were sinister and alarming words which the Chancellor had used. He, Philip Christopher Königsmark, was not to be seen again in Celle. Or—anywhere else? He asked himself. He was to be removed in the dead of night. To a prison? Philip saw his life dragging hopelessly along in some dark cell until his name was forgotten even by his gaolers. But he managed to answer, though his lips were dry and his voice quavered as he answered: "I shall not try to escape."

Gottlieb Bernstorff laughed harshly and suddenly.

"I prefer to make sure of that."

Philip had been standing before the Chancellor with his eyes upon the floor of the gallery. But the utter contempt with which the words were spoken stung him to anger. His cheeks flamed. He looked up with a passionate reply upon his lips. But the reply was not delivered. As his eyes rested on Bernstorff's hand, he stood for a moment paralysed and dumb. Then he gave a cry of utter terror and his hand flew up to his throat.

"You can't mean that!" he whispered. "His Highness has never ordered it. Take me to him! It can't be."

As if to answer him, the door was thrown open and the soldier Muller strode into the room.

"I am wanted?" he asked.

Bernstorff did not for a second take his eyes from Philip Königsmark. "Wait!" he said, and the soldier stood at attention by the doorway, mute, the most frightening thing in the world, a living machine, stupid, powerful, and ready without a question to obey.

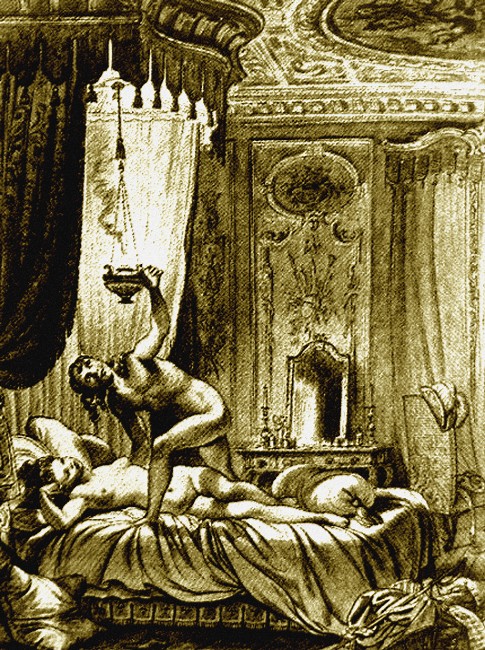

Bernstorff, with a smile upon his lips, was holding in his hands a thin strong cord with a slipknot at one end of it. Whilst he watched Philip, he passed the one end through the knot at the other end and, holding it up, but not too obviously and rather as though he sought to assure himself that the loop would easily slip down, and the circle of cord tighten and contract about a slim young neck, he let the slipknot fall down the cord. Bernstorff was not as yet very clever as a master of irony. His sarcasm was crude as yet—uncouth, he admitted it. But he could at all events frighten a boy. And tomorrow he would learn to frighten a man. And from that fear would spring authority, power and, at the end of it, land—acres of it, great possessions, and titles to match. Meanwhile here was the frightened boy to be still more frightened. Amusing!

He saw Philip Königsmark's eyes following the downward slip of the looped end and the contraction of the cord. Oh yes, the old secret punishment learnt from the seraglios of Constantinople—not at all unknown in the prisons of Europe when importunate offenders must be suppressed. Bernstorff let the loop slide very slowly down. Philip might clutch at his throat and feel the blood of his arteries pulsing there strongly, but his eyes followed the descending loop, full of terror, full of horror. He might try to comfort himself with the feel of the great bow of his cravat. But through cambric and lace, the cord would bite, the eyes would start from the head, the tongue, bitten through in agony, would project beyond the lips, the face would lose its beauty, would become black, ugly, horrible. Bernstorff had this much sense of power, at the moment. He knew that the boy before him was not only watching with staring eyes the contraction of the cord. He was feeling just what Bernstorff was projecting into his mind. He was taking into his consciousness the pictures of sheer physical pain which Bernstorff was imagining. Philip was being strangled, all alone here, helpless as a child—and suddenly Philip's legs gave way beneath him and he fell forward on his knees.

Sheer weakness? Or a boy's cowardice? An equal share of both perhaps, but Philip winced ever afterwards to remember the degradation of that moment. He tried to pretend that he had come to his knees through a mere slip or stumble and that once upon them the very subservience of his position had somehow outwitted him into accepting it, so that he remained on his knees. But in that attitude he had pleaded—oh most humbly—for his life, in words which were broken with sobs and the taste of them was years afterwards bitter in his mouth. The recollection of them would come back to him at odd moments when he waked in the night or sat idly by his fire. He heard them, he saw himself in his fine dress and ignoble pose and writhed in shame and raged against the world. But the words were spoken in a stumbling haste.

"I am too young!... I've hardly lived... I have done nothing which death should punish... A few foolish pledges made, a few foolish dreams exchanged... A few half hours side by side, here, in this quiet chapel... The string about the throat for that... You can't be so cruel."

It was all heady wine to Bernstorff, the unconsidered Councillor of yesterday. No one had ever been afraid of him. He had wielded no authority. What had he been? A clerk—at the best for a few hours a deputy. He felt his heart warm and his blood flow dancing through his veins. He could have listened for an hour, but all joys must end, and there was still work to do that night. As Philip stretched out his hands in a despairing appeal, he slipped the noose over them. The boy recoiled as though a snake had stung him, and Bernstorff's voice rang out above his head.

"Keep still!"

And Philip Königsmark dared not move again. Bernstorff turned back with a delicate slow deliberation the lace ruffles which edged the sleeves of the green coat and, drawing the loop tight till the thin cord sank into the flesh of Philip's wrists, he bound the hands palm to palm so that they were the hands of a Saint in prayer.

"Now stand up!"

Philip rose unsteadily and stood swaying. If any thought of resistance had lingered in his mind, it had gone from him now. He was as helpless as a sheep. Bernstorff took the lad by the elbow and led him a few paces to a chair. Philip did not struggle. He was a little dazed. Terror had so numbed him that he was obedient to a touch. Bernstorff pushed him down upon a chair. He took a second cord from his pocket. He stooped, crossed the boy's ankles and tied them together and then bound them securely back to the cross-bar of the chair.

"So!" he said, panting a little with the violence of his actions, as he straightened his back, "we have our fine young peregrine upon the jess; though upon my word, the peregrine has no more spirit than a pigeon. There and thus you will stay, Philip Christopher, Count Königsmark, until such time as those great ones whom you have wronged have decided on your punishment."

He knew—none better knew—the plain and simple way which the easy-going George William had chosen to end this embarrassment. But, to his thinking, there was no reason why Philip Christopher should know it before he must. Nay, an extra twinge or two would be no more than he deserved. "I leave you to your devotions," he added. "You have great need of them. But I warn you. If you raise a cry, no one except ourselves will hear you. But we shall. Come Muller!"

He led the way out of that enclosed and private gallery. He shut the door upon his prisoner and turned the key in the lock. Philip heard the feet of Bernstorff and the soldier trample on the stone steps of the stair. In a moment the clang of the outer door range through the chapel and in that lock too, the great key rattled as it turned. What did it matter, he wondered, whether they locked the door or not? He could not move and no one in all Celle would come to ease his plight. The chapel was a silent as a tomb. The shadows were gathering over the chancel floor like a congregation of ghosts. In the enclosed gallery with its leaded casements it was already night.

Philip sat in his chair, his shoulders drooping, his head bowed and the heavy curls of his hair tumbling about his face. He was to vanish from Celle. He was to be disposed of when the Castle was asleep. How? He could hear Bernstorff's icy voice framing that enigmatic and appalling phrase. Disposed of! One disposed of things—not living people. Dead bodies were things—and Philip shivered.

He had been wrong, of course, in believing that Bernstorff and his man-at-arms were to execute judgment upon him, then and there. "They wouldn't strangle me in the Castle Chapel," he whispered to himself. But there was little comfort in that assurance. Terror was still at his elbow. He had only anticipated his punishment, dying twice, in the way of cowards.

"Bernstorff was playing with me, cat and mouse," he continued. "But the mouse dies in the end—and perhaps more easily than I shall," and his heart melted within him, and the very spasm of death keeked aloud in his throat. At the sound he raised his head with a jerk.

"I shall kill myself with fear," he thought, and he called upon his recollections of his strength, his memories of the ardent vitality, which only this morning—was it possible?—throbbed within his young body from his head to his feet.

"It will only be prison—prison for perhaps a little while," he argued and, while he argued, he girded at the slavish contentment which the argument brought to him. But to such a pass he had come that he could not banish the contentment.

"I want to live," he said. "I want to go on living—even in prison, if that's the price of living." He tried to evoke before his eyes a portrait of the Duke, kindly, easy-going, indulgent—as he had known him through his few months of service. But he couldn't. His wits were all astray. He could only see a red, gross, swollen face glowering at him, dark with a mortal hurt to his pride of birth. And if he sought hope in an image of Duchess Eleonore, he found it an image of stone with a pair of living eyes in which hatred burned. The very tenderness with which they had dwelt upon her daughter, smiled upon her joys and softened with her sorrows, was a measure to Philip now of the horror and bitter enmity in which she must hold him.

He made a despairing movement and a little cry of sheer pain broke from him. The thin cords round his wrists and ankles so wrenched and tortured him that he almost swooned.

"I must keep still," he warned himself distractedly, "quite, quite still." But his feet were so forced back against the bar of the chair that his knees were horribly cramped, and he must ease them if he could. And with that there rushed upon him, triumphing over his pain, a full consciousness of the ignominy to which he had been subjected.

He, Philip Christopher, Count Königsmark, grandson of old John Christopher who had captured Prague, nephew of Otto William, the Marshal of Louis XIV, son of Conrad Christopher, the Master of all the Swedish Artillery, who had been killed at the siege of Bonn, brother of that Karl John whose exploits were today in all men's mouths—he, Philip, had been mishandled and disgraced by a man who yesterday was no more than a clerk with his pen behind his ear.

"And I suffered it without resistance." He upbraided himself bitterly. "I held out my hands to the cord, glad that it was not tightening round my throat. I let him bind me in a chair—oh, shame!" And he was suddenly amazed at the temerity with which so decadent a bantling as he, had prated of his dreams and of his heart to the lovely Princess of Celle. He had snatched at a planet as though it were no more than an apple on a tree.

Hadn't he deserved all that had befallen him, he asked in his abasement? And all that was to befall him? This contemptuous treatment, the rings of fire about wrists and ankles, the cramped joints, the sharp stabs of exquisite pain which travelled along the nerves of his limbs in flashes of lightning. Thus his thoughts wove backwards and forwards, if thoughts they could be called, clacking shuttles in the loom of a young overwrought brain. And they wove but two webs in the end, a sense of littleness and a sense of pain. And by the time when night had come, pain had overmastered all.

It was pitch dark in the Duke's gallery, but a faint glimmer from the outer windows made a ghostly twilight in the body of the chapel. Philip raised his head and looked through one of the three casements which stood open.

"The dawn is near," he assured himself, but without any confidence. There were indeed many hours to creep by before the dawn shot with its colours that summer sky. They would have been more endurable no doubt to an older man. But Philip was a boy of fifteen and he was hungry and athirst. The hunger weakened him, but he could brave it out. His thirst, however, was torture.

"Water! Water!" he found himself muttering in a foolish repetition. Even if there were water within reach, he could not reach it, and even if he reached it, he would need a cupbearer to lift it to his lips, and there was no one within his call, even if he had dared to call. This chapel was a House of the Dead; and as he framed the words in his thoughts, a tinkling as of tiny bells made a silvery noise in that silent place.

There was no fairy work in those chimes. From the arches of the roof gilded chains hung down with finely carved thin disks of copper dangling at the end of them. Any visitor to Celle may see them hanging down to this day, and wonder at the fancy which conceived so odd a decoration. But Philip Königsmark had never seen them, since his gaze in that chapel never soared above the face of Sophia Dorothea and the flowers in her hair. So when a faint waft of air from an open window set a few of the medallions swinging and chiming, they chimed also with a queer conceit which the stillness of the night and the desolation of his mind had evoked in the boy.

"This is the House of the Dead," he had said, and the clear tiny clinking of these ornaments sounded in his ears as a summons to take his place amongst them. He was too overwrought by thirst and hunger and pain to reason lucidly. He was only aware that a new fear and one more immediate and even more real was being added to those which already tormented him. He sat up and crouched forward, making himself small and praying with all his distracted soul that the utter darkness of this gallery would hide him from the dead. For he heard them now gathering in the chancel, with little whispers as of filmy, trailing garments. So many who had kneeled here and died thereafter! If he could look down from one of these casements, he would see them—he was sure of it!—and more and more of them crowding in from graveyard and tomb. And all of them waiting for the Duke's page in his Court livery to join them. For a moment he was glad that he was bound tightly there hand and foot. And for another moment he rejoiced that the Dead have no eyes. But they were seeking for him, asking where he hid. The whispering of robes had changed now into the whispering of voices, tiny voices, no louder than a breath, but urgent. And then one of them was speaking at his side. They had found him. What the words were, he could not distinguish. But they were spoken quite close to him, and they were quite clear indistinguishable words, the words of a nightmare. Philip flinched away from them and, to cap his terror, once more the flow of wind crept through the open window, and once more the medallions tinkled. He had heard just that same sound in the streets of Catholic towns, when the priest in his robes, and his acolyte with the little tinkling bell, went on their way to the bedside of the dying.

"No! No! I won't come with you. I won't," he cried aloud and he wrenched at ankle and wrist in a panic until the torture stopped him and the tears poured down his face.

Some centuries later, it seemed to him, heavy footsteps resounded in the little corridor behind the gallery, the key grated in the lock and the door was thrown open. Bernstorff, carrying a great lantern, was followed in by the soldier, Muller.

"It is time," said Bernstorff, but he received no answer.

He lifted the lantern high and saw Philip staring at him like someone daft and horribly frightened. To tell the truth, Bernstorff was a little frightened himself. When he had received no answer, and saw only a crouched figure with a head fallen forward on its breast, he had feared that his prisoner was dead. Now he feared that the long ordeal borne by a sensitive boy had driven him out of his wits. He turned quickly to the soldier.

"Set him up on his feet!"

Muller kneeled down and cut the cord from the boy's ankles, and Bernstorff watched Philip stretch out and bring back one leg after the other and flex the muscles.

"Oh! Oh!"

Philip moaned. But the moan of pain changed into a gasp of relief.

"You can stand?" Bernstorff asked.

Philip tried to lift himself up and sank back. He shook his head.

"Not yet."

"Help him, Muller."

The soldier set an arm about Königsmark and raised him up.

"Perhaps now," said Philip, and he stamped feebly upon the floor of the gallery.

But even then Muller rather carried than supported him, along the corridor, down the steps to the door, through the passage and up the great stone stairway to the first floor of the Castle. They turned into the passage on the right which led to the private apartments of the Duke.

"I can walk by myself now," said Philip, and the soldier let him go and fell in behind him.

For a second or two Philip tottered and stumbled, but he recovered his bracing and bracing himself walked forward between the Chancellor and the man-at-arms. The Castle was silent, its doors all shut and only a lamp or two burning at intervals on the walls of the passages. An usher was yawning at the door of the Duke's library.

"One moment, Your Excellency," he said as the party of three approached him. He knocked upon the panel and went in.

His Excellency looked round at Philip Königsmark and smiled. But for the colour of Philip's coat, it would have needed a sharp eye to recognise in this forlorn and dishevelled scrub the pretty stripling with the bright eyes and the kindly laugh. The new Chancellor had been paying himself back that night at Philip's cost for the little office darkened by the line-tree, for his years of insignificance. He had rubbed the gloss off this modish young Adonis. The jewelled green bird had lost all the sheen of his plumage, and Bernstorff was well content.

The usher came out from the library and held the door open. Bernstorff took Philip by the elbow and led him into the room. The usher followed them and closed the door. The room was brightly lit by oil lamps and wax candles in sconces. Königsmark, coming into it from the dark chapel and the dimly lit corridors, was for the first few moments blinded. As his vision cleared, he saw that the Duke was seated at a great table and engaged in affixing his seal to a folded letter. A big goblet and a jug of Rhenish wine stood at his elbow. Behind him, in a shallow recess by the fire, the Duchess was sitting with her eyes upon the burning logs. Neither of them threw a glance at Philip.

Bernstorff placed Philip opposite to the Duke on the other side of the table and himself stood away. Even then neither the Duke nor his wife had a look to spare for the prisoner. The one was busy, or, rather was making business with his seals. The other, by the fireplace, might have been reading her future in the kaleidoscope of the flaming logs, so completely was her face averted.

"To them both," he thought bitterly, "I am a pariah brought up for judgment."

But he was in no state after his grim vigil to observe acutely. George William didn't look at him because he hated from the bottom of his indolent soul the business which it lay before him to do. He was annoyed by it. It was an interruption of the proper placidity of the day. He had now to rearrange his household and very possibly that work might stop him hunting in the morning. He was almost as much annoyed with Philip for causing him all this vexation as for making calf-love to his daughter.

"A couple of babies," he said to himself, pushing his sealed letter peevishly away with a finger.

Besides, he loathed delivering judgment and homilies. He was indeed uncomfortable, like the culprit in front of him, whom he wasn't going to look at. He'd be hanged if he would! He took a gulp of his strong yellow wine. Since the thing had to be done, he had better get it over.

"Philip Christopher, Count Königsmark," he began in a gruff voice with his head bent, like a judge reading his notes, "you will leave Celle and my Duchy tonight, and if you ever push your head into it again, I'll clap you into prison and keep you there. But for certain kindnesses shown to me at Breda by your mother in other days, I should do it now. I shall send a guard with you and he will not lose sight of you till he leaves you at your mother's house. Do you understand?

"Yes, Your Highness," said Philip in a low voice.

"Now for the homily," said George William to himself. But he was a simple country gentleman to whom homilies were parsons' work. He took another drink of his Steinberger.

"I must say finally and lastly," he began and stammered and broke out with an oath, "I'm ashamed to you, Philip. Yes, that's what I wanted to say. A couple of babies holding hands in the moonlight. I'm ashamed of you. There! Take this letter which I have written to your mother and give it to her!"

He pushed the letter across the table.

"Take it and go!"

"I can't, sir," said Philip quietly.

"Can't? Can't?" bellowed Duke George William.

"No, sir!"

Bernstorff made a swift movement towards the table. George William was puzzled. The letter was no business of Bernstorff's. He held up his hand with a peremptory gesture and Bernstorff stopped. Then Duke George William for the first time looked across the table at Philip, and flung himself back in his chair, gasping. He took the whole picture in no doubt, but he was aware chiefly of two enormous dark tormented eyes burning in a face like a white mask.

"Great God!" he bawled, banging his fist on the table so that the wine shook in his goblet and the jug rattled on the wood. "You, Hugo, untie that boy's hands at once."

The usher stepped forward, but the knots were not so easily untied, and he must take a knife to it in the end. Meanwhile Duke George William sat in a rage, glaring at Bernstorff one moment, and at the usher the next.

But even when his wrists were free, there was for a time no diminution of Philip's distress. A spasm convulsed his face and he stood, his hands dangling at his sides like the hands of a puppet, and the room revolving in circles before his eyes.

"Here!" said George William, and he filled his goblet to the brim, splashing the table in his haste. The boy was going to fall. In another moment he would be down on the floor in a swoon. "Drink this! You, Hugo, hold it to his mouth," and he pushed the big glass across the table.

Philip had no more wish to make a scene than Duke William had to witness one. His lips curved in the ghost of a smile and "I thank Your Highness. I can hold the glass now," he said in the ghost of a voice.

The blood was beginning to run back into his numbed fingers. He took unsteadily the glass from Hugo's hand and drank. To his parched throat and overtired heart, the strong wine was the very elixir of life. He drank slowly and a little colour returned to his cheeks, and with a long sigh of pleasure he drew his breath deeply in. he was for setting down the glass still half-full. But George William rapped fiercely on the table.

"All of it! To the last drop!"

"I shall be drunk, sir," Philip pleaded.

"Well then, be drunk and be damned!" cried the Duke, and he sat and watched until the glass was empty.

"This is your doing," he said, turning upon his Chancellor. And that ambitious man saw all his new authority and his future honours crumbling away into dust.

"Your Highness so insisted upon secrecy," he stammered. "I was perhaps over-zealous," and he shot a venomous glance at young Königsmark. He had despised the boy before; he had looked upon him as a footstool for his own ascendancy; but the scorn had become hatred now, and a hatred which was going to increase and feed upon itself until one monstrous night years afterwards glutted it.

Philip picked up the letter and bowed low.

"I shall obey Your Highness's orders," he said.

So that's over, thought Duke George William, and he wiped his forehead with his handkerchief in relief. Philip hadn't swooned, and would be away from Celle in half an hour, and he himself could go hunting tomorrow.

But it was not all over. Philip, with a natural and pretty gesture, walked across the room to the ingle-corner where the Duchess Eleonore was seated. He dropped upon his knee at her side and, lifting the border of her dress, kissed it. But she only shook her head and still gazed into the fire.

"You cannot forgive me," he said. "It is my sorrow. For I am Your Highness's debtor for much kindness."

Philip was as wrong in the reason he gave for her aversion as he had been in judging the husband George William. Eleonore had set her heart, as women will, upon a great marriage for her daughter with young Augustus William, the heir of Wolfenbüttel. It would give Sophia Dorothea the high position in the world which her wealth and her beauty demanded; and in addition it would be a very tough nut for Duchess Sophia of Hanover to crack. But none the less once or twice during this afternoon and night certain doubts, even certain pangs of remorse, had troubled her. When George William had come to Breda, wooing the penniless lady- in-waiting, Eleonore d'Olbreuse, no one had given such valuable countenance to the lovers as Philip's mother, Amalia Magdalena, Countess Königsmark. What sort of return was that same Eleonore d'Olbreuse now making, she asked herself? And she was trying to stifle the shaming question by a show of extreme displeasure.