RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Collier's, 15 May 1937, with "The Last Salute"

I WAS never familiar with the technique of the bull ring. I could, however, appreciate the perfect balance with which a great matador like El Gallo on his day or Juan Belmonte on all his days could twirl round with his feet together within a circle the circumference of a saucer. And I knew enough to be aware that the one and only place where the complete emotional content of a bullfight was capable of being absorbed was the barrera—that first row of seats which runs round the ring just above the alleyway. From that close vantage one was less aware of the spectacle but more conscious that a man was staking his life upon his craftsmanship and the swift obedience of his co-ordinated muscles. One could hear his taunts and curses, and the low answering fury of the bull. One could see him entering within the crescent of the beast's great horns to deliver his final thrust.

But it was none of these reasons which drew me for a season to every feria within reach during the summer months. I went for the fanfare and the parade, the stately march of the matadors and their quadrilles in their gay dresses, across the sand to the Alcalde's box; for the arena so sharply divided between its sun- drenched blazing half and its cool brown half in the shade; for the flicker of fans and the music of the Sevillana; and above all for the cold-blooded passion with which the corrida was followed by the spectators.

THAT was all my interest until this the afternoon of

which I am writing. It was late in July and at Alicante. I

lunched with José Romirez, a shipowner from Valencia, in the club

looking onto the palm trees and the harbor.

"This is Alicante's great week," he said.

"No doubt," said I.

I was not very responsive. José Romirez was a fan among fans, but the day had a blistering heat. The sunlight turned the roadway into glistening brass and the pools of shadow at the feet of the palm trees were black as night.

"There will be Joselito and Gallo and Domingo Plata," José continued. "I have our seats. I will call here for you at a quarter to four."

But the thought of those heavily padded and heavily ornamented velvet coats in which the bullfighters would race about for two hours made me feel sticky and hot.

"Joselito," I argued, "will be as usual faultily faultless, a picture of unimaginative perfection. El Divino Calvo is as likely as not on a day like this to see his dead mother looking at him from the eyes of the bull and to run away like a rabbit; whilst as for your Domingo Plata, I never heard of him."

"I know," said José, softly. "That is why you should come. He is of Valencia, my own town. I can guarantee you an interesting afternoon. I shall call for you here at a quarter to four," he insisted.

He was stubborn. I was languid. I gave way.

"All right! Have it your own way, José."

At four, then, we were in our seats watching the procession move across the arena toward the Alcalde's box above our heads; Joselito on the left hand, tall, slight, exquisitely proportioned; his elder brother, El Gallo, in the middle, his gypsy face anxious, a queer look of the automaton about the movement of his legs; and on the right Domingo Plata, the man from Valencia whom I had never seen. It seemed to me, even at that first moment, that his gait was slovenly, that his face twitched, that, to use the jargon of the day, he was conscious in the presence of these two famous spadas of an inferiority complex.

I looked at José Romirez. He was passing the tip of his tongue between his lips from one corner of his mouth to the other. But his eyes were fixed on Domingo Plata. I looked up suddenly at the crowded seats. Perhaps it was an illusion—I can't tell. But it seemed to me that all eyes were fixed upon Domingo Plata, that all the owners of those eyes were, with an instinctive movement, moistening their lips with the tips of their tongues.

And the seats about the ring were crowded up to the very highest rows. Now Alicante is, to be sure, the playground of Madrid. During the summer season, the trains disgorge battalions of clerks and typists and shop assistants onto the long line of beaches and bathing establishments to the left of the harbor. It was inevitable that the bull ring should be well attended. But a lleno completo like this was out of the common, would have been out of the common even on a Sunday in Madrid, with Ortega, say, instead of Plata to complete the trio of matadors. However, here were the three of them, with their hats doffed, bowing to the President's box. Joselito, dignified, a friend of kings, conferring a favor, El Gallo's bald scalp glistening like a very white unripe melon, and Plata's reddish brown head bowed, as though he said, "We who are about to die, salute thee—"

THEN they ranged themselves about the arena, a door was

thrown open and the bull was in the open. It was a big black

beast of the Santaguena breed, and the Santaguena bulls had been

very deadly that year to matadors. I looked at the program. Yes,

the six bulls of the afternoon were all from that estate.

But Santaguena or not, it was all one to Joselito. The massive beast could not turn within its own length, and Joselito so forced it to wrench its body and tire out the great muscles of its neck in the effort to do so that it was ripe for the sword well inside of the twenty minutes beyond which no wise matador will allow a bull to live. Rafael Gallo, too, had neither seen his dead mother in the eyes of his victim, nor passed a funeral on the way to the ring, nor suffered any of those portents which turned his superstitious heart to water. He was in his most elfish mood, a bald-headed schoolboy on his holiday, conceding to himself all those little jocosities and funniments of which the ritualists of the bull ring disapprove. However, there were not many of the ritualists present that afternoon, and hats and cigars rained down into the arena.

"Now!" said José Romirez, shrugging himself together on his seat, and "now!" it seemed to me that everyone to the topmost benches, man, woman and child, was saying in an excited undertone:

"Now!"

And the truth of this corrida was brought unmistakably home to me by that unspoken message which passes like a spark from mind to mind in a crowd. They were all present, man, woman and child, from the barrera to the loftiest seat on the rim of the building, to see Domingo Plata killed. It was he, rather than Joselito; he, rather than the divine bald man, who had packed the Alicante bull ring on this hot afternoon of July.

Domingo Plata was a little man with a scholarly, nervous face, and without doubt the worst bullfighter I ever saw. He made a few preliminary passes—veronicas, I believe is the proper term—with his quadrille spread behind him ready to draw the bull away—the ABC of the matador's art. But as soon as the horses were out of the ring came the first real test of proficiency. It is the fashion, though not the law, that the killer shall himself plant the first two banderillas in the bull's back, those long sticks with the steel arrowheads which weaken the animal and prepare it for death. He must stand forth alone, invite the charge and, running swiftly forward across the line of it, turn as the bull's horns flick past his chest and, lifting high his arms, drive the banderillas deep into the bull's neck.

DOMINGO PLATA was brave, that was clear, and he had a

turn of speed. But he had no eye to measure his distances. The

curve of his run was wide. He drove his sticks into the beast's

shoulder, and with a roar of fury and a great bound, it shook

them both out onto the sand. A yell of derisive laughter broke

from the spectators, and his quartet of banderilleros took

up the work and showed him how it ought to be done. I could feel

the relaxation of the spectators and their nerves tighten up

again when the last stage of the fight, the faena, was

timed to begin.

Domingo, with the sword in his right hand and the scarlet cloth in his left, went forward to meet the great Santaguena bull alone. He was brave enough. He marched on a straight line toward the muzzle of the beast.

José, watching him, said—and I certainly heard a tiny note of distinct regret in his voice:

"The bull, too, is brave and noble. It will have no cunning."

He saw that, with no tricks on either side, brave man facing brave bull, the man might win. For my part, looking at that great lump of muscle on the bull's neck, as firm as when, fifteen minutes back, it had rushed into the ring, I couldn't for the life of me see what chance Domingo Plata had, and I said so.

But José Romirez had no ears wherewith to listen to me. His eyes, his every sense, were concentrated on the matador and the bull. I looked about me. The same tense expression was visible on every face. I couldn't doubt that some very important and critical phase in this deadly tournament was being decided. All, however, that I could see at the time was the plain fact that Domingo, with little twitches of his red cloth and little abrupt steps backward, was trying to entice the bull into the center of the arena and that the bull wouldn't budge.

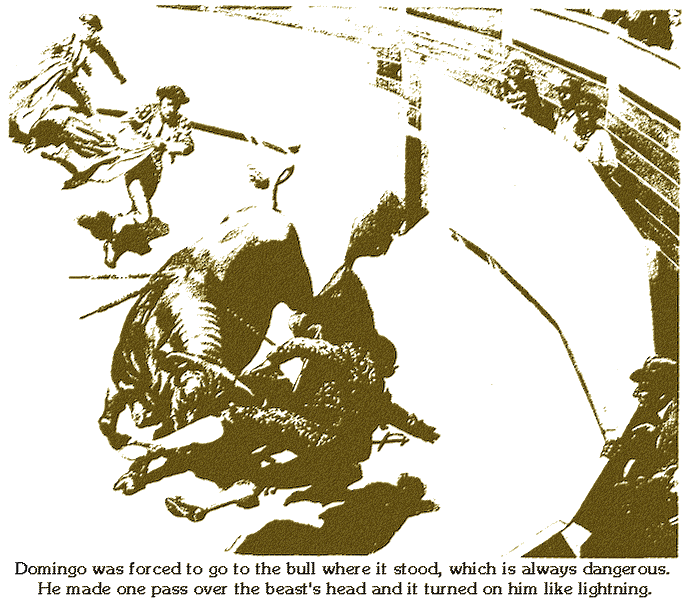

AGAIN and again Domingo tried to lure the great brute

into the open. The expectation of the spectators was dissolved in

jeers. A cushion flew through the air. Domingo was forced to go

in and try to kill the bull where it stood—and that is

always dangerous. He made one pass with the red cloth over the

beast's head. It turned on him like lightning and the next moment

he was flung in his embroidered uniform like a doll against the

palisade. The crash was heard loud over the arena, and as the

other matadors and the banderilleros dashed forward to

draw the bull away, I saw Domingo with a leg of his breeches

ripped at the thigh and the blood spurting out in a fountain. A

cry rang out from a thousand throats, but not a cry of pity. It

was "Ohé!" rather than "Oh!" It was the "Habet!" of

the old Colosseum, and as Domingo Plata, with his thigh tightly

bandaged, was carried out the band blared out a Sevillana.

"Wait here," said José, "I'll find out how he is."

He went round to the surgery and came back with a smile of relief upon his face. Now that the fight was over, Domingo Plata was once more a friend of his.

"He has had the luck of the devil," said José. "I was afraid that his thigh was smashed, but the bone was never touched. He has lost a lot of blood, of course, for an artery was severed, but he'll get well."

"No blood-poisoning?"

José Romirez was not afraid of it.

"They are fairly tough, these matadors, and at this time of the year, of course, as hard as nails. Besides, our surgeons know their job."

We watched Joselito kill his second bull with the same graceful and uninspiring precision, but my thoughts were not upon him at all. I said to José Romirez:

"What on earth made that man think he was a bullfighter, and how on earth does he secure an engagement?"

"That," said José, "he shall explain to you himself."

And certainly it was as odd a story as I have ever heard.

FOUR days afterward I was taken by José to the hospital,

where Domingo Plata in a separate room lay surrounded in the

Spanish style by a congregation of relatives, with every window

closed. José dealt with them magisterially. He flung up the two

windows to begin with. A tumult of shrill feminine expostulations

deafened us both. The poor one would catch pneumonia for a

certainty. How could he get well? It was a cruelty.

"How could he get well anyhow," cried José, "with a crowd of foolish women babbling over him in an air that's mephitic? Go out! I have brought a man of sense to talk with him."

He persuaded and cajoled and bullied all of them out of the room, except Domingo's wife, Pilar, and a cousin of his, a big braggadocio fellow with a heavy mustache and an atmosphere of garlic. Pilar was a good-looking woman, dressed rather extravagantly in some delicate white material like a great lady of Madrid. She was of Domingo's age, but she looked worn, as indeed, considering the risks of her husband's life, she might well be.

"You are going home today, Pilar?" said Domingo, smiling very happily upon her. "The good Enrique will look after you."

"To be sure," said Enrique, stroking his mustache.

"Give my love to the children! In a fortnight I shall be home."

Pilar nodded her head and, bending down, whispered in his ear,

"Yes, yes, all that shall be seen to," Domingo replied. "I shall talk with José."

They were got out of the bedroom at last and José Romirez turned sharply on the patient:

"It was about money, of course—all that whispering?"

Domingo Plata smiled, deprecating his friend's indignation.

"But, José, you must really learn something of the world," he said. "Pilar, the darling, is a woman, and women want money." He looked from José to me. "You are the English gentleman of whom José spoke to me?"

José answered for me.

"Yes. I shall leave him with you for a little while, Domingo," and he added to me, "it is good for Domingo to talk. You shall hear the story of a hero," and he left us together.

Domingo laughed outright as soon as we were alone.

"You are curious about me?" he said. "But there is no mystery."

And indeed, as he lay there on his bed, pale and with that spirituality of look which comes from the endurance of much pain, he seemed to me an open, cheerful, trustful person, who had made up his mind after long thought to adopt his hazardous career and was quite unconscious of any heroism.

"I am really a schoolmaster," he began, and I was not surprised to hear it. "I was a government schoolmaster at Valencia and my salary was exactly one thousand pesetas a year, which amounts at the normal exchange to forty pounds sterling. I married—" he shrugged his shoulders to signify that this was the sort of natural thing that one inevitably did. "Marriage has its drawbacks, of course. We could afford no holidays, for instance. But there were other people no better off. We managed—until the children came, first one, a boy, Juan, and then a girl, Marita."

HIS face lit up like the morning, with such pride and

pleasure and love that I who looked on was warmed and moved by

it.

"You shall see them," he cried eagerly, offering me a treat which I was to recognize as rarely conceded to human beings. "Juan, he is ten. Marita—" and he laughed from joy and then was twisted with the pain of his wound—"Marita," he continued in a subdued voice, "she is eight. But forty pounds a year, eh? I could save nothing for a dowry for Marita and nothing for an apprenticeship for Juan, and nothing for a new dress for Pilar, my wife. And when I was old there would be no pension. No good, eh?"

"Not good at all," I answered.

"So we had to think, my poor wife and I. And after we had thought of everything I began to wonder. In the village where I lived as a boy, we had an old bull, and on feast days we made the little village square into an arena with hurdles, and had a bullfight. The bull, of course, was never killed, for we could not afford another, and he was not very angry and all the village fought him at once. Every now and then someone was wounded, and there was a story that once when the bull was young, a boy had been killed."

IN THESE village corridas it appeared that young

Domingo Plata had outshone his rivals. After he became a

schoolmaster, José Romirez took him at times to one of the big

festivities at some great breeder's estate on the Guadalquivir,

and he was allowed to try his luck with other amateurs on the

young bulls.

"As an amateur," continued Domingo, "I could hold my own. I talked to José. He was discouraging, but one day in the summer— it was five years ago—a matador fell ill who was engaged for a corrida at Castellon. Do you know Castellon? It is a secondary town fairly near Valencia, and the bullfight was quite a secondary affair. The management was at a loss for a substitute. It was the time of the year when any matador of any quality was engaged. José secured the opening for me. The bulls wore poor and cowardly." Domingo smiled as he added: "You will be surprised to hear that I wasn't hurt, and surprised too, perhaps, that for that one afternoon I was paid four years' salary as a schoolmaster."

It had seemed to Pilar, to his cousin, Enrique, and to himself that the good God had demonstrated with an unmistakable clarity how Domingo Plata was to provide a future for his children. He had resigned his schoolmastership. He had secured a few engagements. He had been derided, gored, tossed—and gradually there had spread the great news that at some corrida— probably the next—Domingo Plata was certain to be killed.

"From that moment I prospered. I fought, say, four times each season. If I was lucky, five. During the rest of the time I have been in hospital. But on those four or five times I fill the seats. They come to see, in my case, blood—yes, that's it, blood. And upon the whole they get their money's worth."

HE GAZED at me with a curious smile of triumph on his

face. I really did not know what to say to him, and no doubt I

looked sufficiently uncomfortable. For he took up my unspoken

thought.

"The blood lust, eh? Yes, as a race we have it. Even José"— and he broke into a laugh which was actually tender as well as cheerful—"even José, who is my very good friend, when he is on the barrera, at your side, say, he licks his lips a little when I lead my quadrille into the arena."

He lay back upon his pillow and in a moment or two said softly:

"Well, I shall fight again in my own town, Valencia, at the end of August; and that will be my last fight."

I was startled. There was no fear in his voice, no superstition, no foreboding. Domingo spoke with absolute certainty. The thing was settled.

"But the bulls will be no more dangerous than the bulls you met here at Alicante." I stammered.

"They will be Veragua bulls, the best in Spain."

"But not more dangerous," I repeated.

"No! Yet it will be my last corrida, one way or another," he said.

He beckoned to me to come closer.

"I shall tell you something which only José and I know," he continued in a low voice. "With the money I shall earn at Valencia, I shall have eight thousand pounds. Think of it! Oh, it is not one of the great fortunes like Belmonte's! But for me, who had forty pounds a year and no pension? Good, eh?"

"Very good," I answered.

"My wife—she is a darling, but she would like to spend it. It is natural. She has lived hard. But I thought of Juan and Marita. It is their money. So I have kept the secret. Oh, we were more comfortable, of course, these last four years, but still we have been poor people in a small street. I have given everything except what, as poor people, we needed, to José, and he has invested it, some in his ships, some in America, some in England. I have four hundred pounds a year," and he chuckled.

The wounds, the pain of them, the long weeks in hospital were a trifling memory compared with this prodigious fact. A little dowry for Marita, a sum to start Juan on a career, and for Pilar a pleasant competence. For himself, too, if only the good God was kind at Valencia and the Veragua bulls were not too quick and crafty.

"It is amusing that if I had been a better matador I should have done much worse. But I was sure to be killed and it is a miracle that I am not. But each time it would happen, so each time the seats were filled and each time I was paid good money. But after the corrida at Valencia, I shall tell Pilar. I can see myself running home to her. 'Pilar, it is over! We will take the niños to the best restaurant and make a feast. We have four hundred pounds a year—each year until we die.'"

He stopped at that word "die," not with any shiver of apprehension. He had looked death straight in the eyes too often, and had suffered too many of its pangs to make demonstrations about it. But his face became grave.

"If I cannot run home at Valencia, José will see to it. There is a little trust. Pilar—I love her very dearly, but she does not understand money. She will be safe all her life, she and the children."

He nodded his head with a quite ineffable look of happiness in his face.

José Romirez came back into the room as he finished and looked at his wounded friend with contentment.

"Domingo had to tell someone," he said, "and what audience could he choose better than a friend of mine who can hold his tongue. But that is enough for today."

Outside the hospital, I took José Romirez by the arm, an act which astonished him, for he had the proper illusion that all Englishmen were of an adamantine insensibility.

"It would be a tragedy," I cried, "if that man were killed at Valencia."

José Romirez walked on for a little way without any sign of agreement. Then he said: "Perhaps." He took half a dozen steps and added: "But perhaps not."

I stopped and stared at José. But he was more serious and troubled than I had ever known him to be.

"What do you mean?" I asked.

"That there may be a worse tragedy in store for Domingo," he said at length. "Pilar and that great hulking butcher of a cousin, Enrique, are lovers. They want him to die. They want his money to spend. Whilst he is fighting in the arena, they sit in his house, hoping and hoping and hoping that there will come a knock upon the door and a message that somewhere in Spain Domingo is on a slab in a mortuary."

IT HAPPENS, of course, infrequently. A third-rate athlete

makes history. A jumper above his form soars to a world's record.

An author writes forty unconsidered books and then one which will

be remembered. So it was with Domingo Plata on the afternoon of

his last corrida. He was in the town in which he lived,

amongst the people whom he knew, and he longed to leave a name

there, which should be something more than a synonym for

derision. Besides, if he could only reach seven o'clock alive,

his passage was booked for the Fortunate Isles. It was Domingo's

last throw and he was inspired. For two hours he matched the best

of the matadors.

"Ohé!" yelled José Romirez at my side, as Domingo played with that last Veragua bull, while the shadow stole farther and farther across the arena. "Ohé!" I tell you! Domingo too has seen someone in the eyes of the bull, but it was not his dead mother. It was Juan in one eye and Marita in the other; and he sprang from his seat with another "Ohé, Domingo!" as Domingo, having brought the bull in four successive charges past him, with no more than an inch of daylight between his breast and the horn, finished with a swift swirl of the cape, left the bull standing, and walked indolently away. He had the great beast dominated, obedient. He worked it down to our end of the ring, and then turning his back, skipped like a dancer the whole length of the arena, with the bull at his heels. He never even troubled to look over his shoulder. He was at the mercy of the beast if it caught him up. But every fifth or sixth step he changed his feet, and to our amazement the bull copied him. There was such a tornado of applause when Domingo reached the other end and slipped away as I have never heard even with Belmonte at his best. I asked Domingo afterward:

"Had you planned that dance?"

And he answered:

"No! It came to me at the moment. I had no fear, no anxiety. I had a divine sense of mastery. I was so in harmony with that bull, I knew that he would think as I wanted him to think and do after me what I did."

He completed his faena with a magisterial killing. He had the bull's forefeet exactly level, its head lowered to the exact degree. He went in with the scarlet cape held right across his body with his left hand. With a tiny flick he turned the bull's head away and the sword slid down through the neck to the heart, so that the beast stood dead upon its feet for a second and then fell in a mass upon its side. Hats spun down into the arena. Domingo walked round to the front of the Alcalde's box in a rain of cigars. From every side a great shout went up:

"La Oreja! La Oreja!"

The bull's ear! The reward of great skill, the tribute to a matador on his day of triumph, was demanded for Domingo. The President with a wave of the hand conceded it. Domingo walked again round the ring and sent the hats spinning back to their owners, bowed and smiled and flourished his hat and, once the ear was handed to him, ran at his fastest pace into the patio de cabellos as though he had more important business on hand.

"We must catch Domingo before he goes. Hurry!"

BUT hurry as we did, Domingo had got away. He had run

through the patio de cabellos to the entrance. He had

flung himself into a taxi.

"Did you hear where he went?" cried José, and half a dozen loiterers in the entrance answered him:

"He went home."

José swore loudly and hailed his own car. He gave Domingo's address and pushed me through the doorway.

"He has a good way to go. We may catch him up. Drive fast! Drive for your life!" he shouted to his chauffeur and then sat silent with an odd look of fatalism on his face.

"What are you afraid of?" I asked, and he stared at me.

"You and Domingo talked of the blood lust, didn't you? Of the sharp tang it gives to pleasure. You don't have to be in the bull ring to feel it. Those two are at his house—Pilar and Enrique."

"They weren't watching him!"

"No! Ask yourself why! They were better engaged, those two."

DOMINGO'S house lay in a small mean street near to the

port. I expected to see it crowded with his friends. But we had

outdistanced everyone except Domingo himself—perhaps

Domingo too.

José sprang out of the car and opened the house door. We were in a passage with a straight flight of stairs running up in front of us. José uttered an oath. In a room above a woman was crying and a man, who was not Domingo, was bleating excuses.

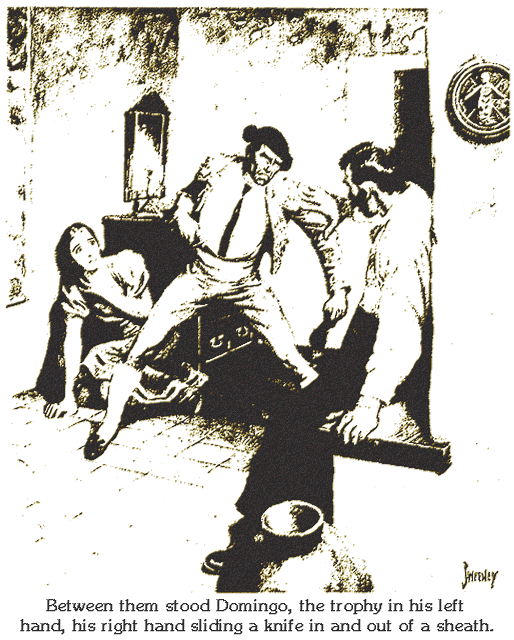

We ran up the stairs and broke into the room. Pilar was in one corner with her hands over her face, Enrique Villa in another, his gross face quivering with terror; culprits who had put the room between them. And between them stood Domingo, the bleeding trophy of the bull's ear dangling in his left hand and his right hand sliding a knife in and out of a sheath at his belt. He said never a word. He was watching Enrique with his head a little lowered, just as a bull will do before he selects from among the banderilleros and the matadors whom he will charge. I have never seen a murderer, but I saw a murderer's nearest relation at that moment.

José broke the spell. He took Domingo's right arm and Domingo stared at him in perplexity as though he had never seen him in his life before. José removed the knife altogether from its sheath and Domingo let him do it, watching his hands with an odd kind of distant curiosity, as if he were wondering why this stranger wanted his knife.

"You are coming with us," said José. It was a simple statement, not a question. "And now. In five minutes you'll have a crowd outside clamoring to see the bull's ear."

"Oh, yes, the ear," said Domingo.

He looked down at it as though he had only just become aware that he was carrying it. He spoke so gently that Pilar was quite misled. She crept a little way toward him. It was all a mistake, she said. He was her "querido Domingo." He had been happy with her, hadn't he? All these years of poverty! She wrung her hands. The tears were streaming down her face and now she was nearer still to him. But Domingo was only interested in that beastly grayish trophy which dangled from his hand and dripped— dripped upon the floor.

"It was Enrique," Pilar said in a wheedling voice, summoning her smiles to match her voice. "Enrique pestered me—" and at last Domingo interrupted her.

"Madre de Dios!" he said in the low gentle voice which he had previously used. "Madre de Dios!" and then raising his left arm slowly he slapped the ear violently across her face, and let the ugly thing fall to the ground. Pilar shrank back with a cry, her mouth open, her white face laced with stripes of blood.

Domingo neither looked at her nor made any sign that he had heard her cry. He went out of the room and down the stairs with José Romirez. In a little room at the back of the house he stripped himself of his bullfighter's finery and put on his ordinary clothes. He folded up the embroidered velvet jacket and breeches, the long roll of scarlet silk which he had worn about his waist, the silk stockings, and put them away in a cupboard, just as if they were still his stock in trade and he would be needing them again. When he had finished, he turned to José:

"The children?"

José nodded his head.

"I shall take them to my house. They shall sleep there. You too."

Domingo held out his hand and shook José's. Then he stared for a few moments at the floor.

"But for you two I should have killed them both." He glanced at me with now a touch of amusement in his bitterness. "Yes, we all have it, you see," he said, recalling our conversation in the hospital. "I should have killed; I felt my knife sliding into Enrique's fat body, and there would have been Juan and Marita disgraced forever."

"That'll do, Domingo," said José and he pushed him gently toward me.

"Take Domingo to my house. Then send the car back for me. The children will have to pack up some clothes. I'll join you with them."

Domingo obediently left the house with me. But as he was on the point of stepping into the car he swung his arms out wide, and with all the braggadocio of a matador dedicating the bull he is about to kill, he cried aloud:

"I dedicate this house to you, Pilar, and to you, Enrique Villa."

We jumped into the car and drove off just as a crowd of cheering enthusiasts appeared at the other end of the street.

THE end of the story? Well, I have told you that Domingo

was a schoolmaster. He carried out the plan which he had in his

mind, minus Pilar, his wife, and Enrique, his parasite. If you

ever cross by the ferry from Algeciras to Gibraltar at nine

o'clock in the morning, you will be as likely as not to see a

smiling little unobtrusive man. If you climb behind him up a

staircase to the first floor of a house in the main street, you

will come to a door with a plate, on which is engraved:

DOMINGO PLATA

Lessons in Spanish

Hours 10

A.M. to 1

And if the room is empty, you will infer from Domingo's manner that he really does not mind very much whether he has pupils or not. In any case you will certainly not imagine that Domingo Plata had ever been granted the ear in a bullfight, or guess what he had done with it after he had received it.