RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

"YOU will call at the Villa Pontignard at noon to-morrow. The Duchess will herself receive you," said the butler, with a superb condescension, and he paced away up the narrow winding streets of Roquebrune, wondering, with perhaps a little contempt for the incomprehensible eccentricities of rank, what in the world the Duchess of Pontignard could have in common with a little village schoolmaster that she should be at the pains to command his presence.

The schoolmaster, however, had no doubts as to the reason of the summons. He leaned over the parapet of the tiny square before the schoolhouse, and from head to foot he tingled and glowed. It was his brochure upon the history of the village—written with what timidity, printed at what cost to his meagre purse!—which had brought him this recognition from the great lady of the villa upon the spur of the hill. Turning about, he could just see, as he looked upwards, the white walls of that villa glimmering through the dusk, he could imagine its garden of trim lawns and oleanders and dark cypresses falling back from bank to bank in ordered tiers down the hill-side.

He had no doubts as to the reason of the summons.

"To-morrow at noon," he repeated, and he turned back again with a shiver of fear at the thought of mistakes in behaviour which he was likely to make. How did one meet a Duchess? Did one bow or did one kiss her hand? What if she asked him to breakfast? There would be unfamiliar dishes to be eaten with particular forks. Sometimes a knife should be used, sometimes not. He looked down the steep slope of the rock, on the summit of which the village was perched, and again anticipation got the better of fear. A long lane of steps led winding down, and his eyes followed its descent, as his feet had often done, to the little railway station by the sea, through which people journeyed to and fro between the great cities. His eyes followed the signal lights towards another station of many lamps far away to the right; and, as he looked, there blazed out suddenly, just above that station, other lights of a great size, and an extraordinary glowing brilliancy, lights which had the look of amazing jewels. They were the lights on the terrace at Monte Carlo. The schoolmaster had walked there on his rare mornings of leisure, had sat unnoticed on the benches, devouring with his eyes the passers-by, all worship of the women in their elegant frocks, all envy of the men for their composure of manner and indifference to scrutiny or remark—wonderful beings, with one of whom he was to speak, actually to speak, at noon to-morrow.

The schoolmaster was not a snob. The visit which he was bidden to pay was to him not so much a step upwards as outwards. In this little village set apart on its mountainside, built into it—for everywhere in the streets the rock cropped up between the houses, and the streets themselves climbed through tunnels of rock—he was tormented with visions of great cities and thoroughfares ablaze, he longed for the jostle of men striving one against the other, he craved for companionship as a fainting man craves for air. "To-morrow at noon," he said to himself. The stars came out above his head; they had never shone brighter; the Mediterranean, dark and noiseless, swept out at his feet beyond the woods of Cap Martin. But his eyes turned constantly to the glowing terrace of Monte Carlo, or were bent directly downwards to the little station and its signal lights.

The Duchess, an elderly lady, who had long since retired from the world, received him the next morning with a simplicity which put him at his ease. She held his brochure in her hand, and she bowed to him. There was a look of relief on the schoolmaster's face as he returned the bow. She had not held out her hand.

"You are a native of Roquebrune, Monsieur?" said she.

"No, Madame," he answered, "my father was a peasant at Aigues- Mortes. I was born there."

The Duchess nodded in approval of the simplicity of his reply.

"Yet you write, if one who is unlettered may say it without presumption, with the love of a native for his village."

The flattery unlocked, at it was intended to do, the schoolmaster's heart. The Duchess made him sit down, and he found himself, to his intense astonishment, confiding to this gracious old lady truths about himself without any feeling of confusion or timidity.

"It was not love for Roquebrune which led me to write the little book," said he. "But I have always had, I think, longings almost too vague for me to express even to myself. When I came here upon my appointment as schoolmaster, I was not content with the children's lessons for my working hours, and the two wine- shops for my leisure. I was not content. I took long walks over Cap Martin to Mentone, along the Corniche road to La Turbie, up the hillside towards Mount Agel. But still, as Madame will understand, I had my thoughts, my longings as continual companions; and at last, since everywhere I saw traces of antiquity, and heard something of the attacks by Algerian pirates, I thought to write this history as a relief. Once I had begun it, I found that so many mistakes were current, I took a pleasure in putting them right. There are so many. For instance, the belief that the old Roman road is the present Corniche, whereas——"

"Whereas," the Duchess interrupted gently, "the readers of your brochure know that that is not so."

She had no wish whatever to hear details about the level of the old Roman road over the Alps. She deftly brought the schoolmaster back to discourse about himself, and in the end was satisfied. Therefore she told the reason for which she had summoned him.

"My daughter, Monsieur, is now 17. It will be my duty soon to present her to the world, but I would have her educated first as completely as possible. It is not easy to obtain a governess proficient in every branch, and I will not part with her. I thought, therefore, that I might be able to arrange with you to read history with her during your spare hours."

The schoolmaster felt his head turning. That he was the recipient of the great lady's charity he was not for an instant aware, and, indeed, it was intended that he should not be. The Duchess had noticed this poor solitary youth, had pitied him on account of his poverty, and had thus found her way in some measure to relieve it. She had the firmest faith in her instincts, she had sounded the man, she believed him trustworthy, and by offering him this work she would be augmenting his pittance and not diminishing, but, on the contrary, increasing, his self respect.

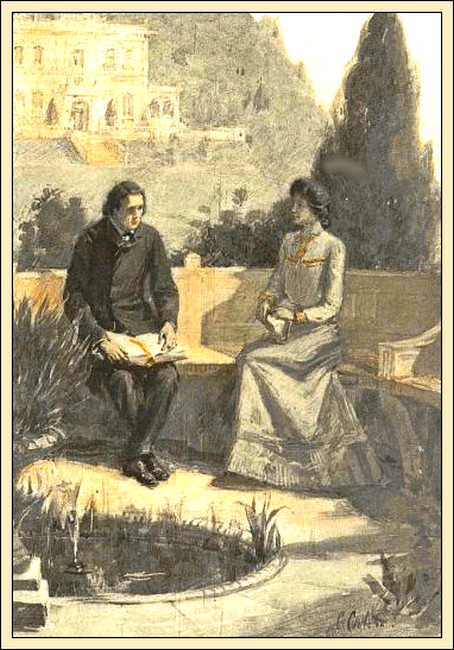

From that time, therefore, on three afternoons a week, the schoolmaster climbed up to the villa. And if he taught the daughter Felicia a little, a very little history, he got from her much more instruction than he gave. For in the intervals of their reading they talked, and generally upon the one point they had in common, their curiosity as to the life of the world beyond their village. Felicia knew no more of that world really than he did, her ideas of it were as visionary and as dream-like as his, but they were not his, as he was quick to recognise. The instincts of her class, her traditions, the influence of her mother were all audible in her words.

One day she said to him: "You let me always talk now. Why have you grown silent, Monsieur?"

"You know more than I do."

"I?" she exclaimed, and then she laughed. "Really we both know nothing. We only guess, and guess. But it is pleasant work guessing, isn't it? Then why have you stopped?"

It is pleasant work guessing, isn't it?

"I will tell you, Mademoiselle. It is because I have come to guess through your eyes. I see the world through them."

Felicia looked out for a little while over the Mediterranean. They were sitting on a terrace of the garden among the cypresses, and the whistle of a "Rapide" mounted through the still air to their ears.

"Well," said Felicia, with a sigh of impatience, "we shall both know the truth sometime, and soon."

It was understood, of course, that this undisciplined village schoolmaster was to leave Roquebrune and carve out a career. When and by what means were questions which had not been considered. The schoolmaster himself might have considered them, might have doubted, but, as he had said, he looked out at the world through Felicia's eyes. And she had no doubts. With a girl's oblivion of obstacles she was convinced that somehow the thing would happen. Meanwhile the schoolmaster's longings, fostered in this way three times a week, grew and consumed him.

Then he came one afternoon to the terrace with his eyes fevered and his face drawn.

"You are ill," said Felicia. "We will not work to-day."

"It is nothing," he replied. "Two travellers came up to Roquebrune yesterday. I met them walking by the church. I spoke to them, and showed them the village, and took them by that short cut of the steps down to the railway station. They were from Paris. They talked of Paris. I have not slept all night," and he clasped and unclasped his hands.

Felicia looked down at her history, and said: "Hannibal crossed the Alps. You must go to Paris. Why not become a Deputy?" and she clapped her hands as the idea occurred to her.

"A Deputy?" exclaimed the schoolmaster, flashing with pride.

"Of course," said Felicia, utterly amazed that she had not thought of so simple a solution before. Hannibal's passage of the Alps was forgotten for that afternoon, and Felicia's project was developed instead. The ways and means of becoming a Deputy were of course left out of the question. The schoolmaster was to become a Deputy. Therefore he was as good as a Deputy already. They started with the premise that he was a Deputy, and the Deputy's future was mapped out. Felicia was to marry, someone of course who loved her very dearly, but the someone was to be, at the same time, a person of great importance. Felicia would have a salon with weekly reunions of distinguished people, where the rising young politician, who had once been a State schoolmaster at Roquebrune, was to be introduced to proper notice. Felicia saw no difficulties. He must have a dress-suit, that was all. She even got so far as describing, from hearsay, the imposing public funeral of a President of the Republic. And the schoolmaster still saw the world through her eyes.

But the time came when the history books were shut, and Felicia prepared for her first season in Paris. Frocks and hats drove the fortunes of the schoolmaster from her thoughts, and it was with a feeling of remorse that she met him one afternoon in the street of Roquebrune, and received his wishes for a safe journey and a time of much enjoyment.

"But I shall miss our quiet afternoons on the terrace," she said, speaking out of her friendliness rather than out of her convictions. "Besides, I shall come back to Roquebrune," she added quickly, "and you are to come to Paris too. That is arranged, is it not?"

And so Felicia went to Paris, and the schoolmaster lost his one glimpse of the outer world. But he lived upon the recollections of it. He took again to his long walks on the Corniche road, sustained by Felicia's conviction that some day, it might be on this very evening, the miraculous opportunity would be discovered, and he would find himself transported to Paris. The summer came, and he heard that Felicia was at Dieppe. During the autumn he caught sight of her name now and then in one of the Riviera newspapers, as a guest at this or that country house. Finally, in December, he was told that she was returning to her mother at the Villa Pontignard. There was to be a house party to welcome her return. From the moment when he learnt that, the schoolmaster became an assiduous frequenter of the platform at the station.

No Rapide passed from France through the station on its way to Italy during his leisure hours but he was there to watch its passengers. It was not merely his friend who was returning, but his instructor, and with new and wonderful knowledge added to the old. So he watched with a thrill half of longing, half of fear. And at last he saw her descend with her maid from her carriage. He experienced the relief of a man who has regained his eyesight; she was his window on the outer world. He followed her, he spoke to her, and she turned towards him. She gave him her hand, she said easily some simple words of friendliness, and at once he was aware of the vast gulf between them. With a woman's inimitable quickness she had acquired in these few months the ease, the polish, the armour of a woman of the world. She was of the world now, the great outside world; he was still the village schoolmaster, and he stood confused before her. She spoke again, asking after his school. He could barely answer her.

"But you must come up to the villa," she said. "We have much to talk over. I have much to tell you," and so she stepped lightly into her carriage, and was driven up the road.

But she had nothing to tell him. The schoolmaster stood upon the platform and knew. The afternoons upon the terrace, the speculations, the encouragements, these things were of the past. His window was darkened, he would never find his way out of the room, he felt it very surely. But none the less he went up to the villa that evening. He did not go to the house, he crept through the garden to the terrace, and sat there in the shadow of a cypress. He could hear music within the house, and the sound of laughter, and all at once he heard voices speaking in the night air, and drawing nearer to where he sat. He had not time to slip away, and he sat in the shade of the cypress while Felicia and a youth walked down upon the terrace. The youth wore one of those dress-suits, which the schoolmaster must procure before he could figure in Felicia's salon as a rising politician, but he wore it with a grace which the schoolmaster knew, did he live to be a hundred, he could never counterfeit.

"My cousin," said Felicia, "I have spent many hours upon this terrace."

"Of all those hours," replied the cousin, "I am very jealous, and the more jealous because you speak of them with regret."

"Regret, not on my own account," replied Felicia.

She was silent for a little while, and the schoolmaster could see the feathers of her fan waving to and fro in the starlight. He sat still as a mouse, for he saw the world through Felicia's eyes. He had the more reason to see it now after her sojourn there. She continued:

"The schoolmaster came up from the village to read history with me here. It was a plan of mother's. He was poor, lonely, and she pitied him. He became my friend. We both knew nothing, and so we were less hampered in making plans. He was to become a Deputy. How, the good God most decide. I was to marry—oh! not him, there was no thought of that, but some great person, and hold salons at which my Deputy would figure——"

"What nonsense!" interrupted the cousin in a voice of irritation.

"No doubt, no doubt," said Felicia, with just a hint of sadness, "but it was rather pretty nonsense."

The schoolmaster climbed down to Roquebrune as soon as the terrace was empty.

He still saw the world through Felicia's eyes, but now he saw through the same eyes—himself, the poor, half-educated peasant, feeding upon vain dreams, and accepting the Duchess's charity as a recognition of merit. He leaned over the parapet of the little square before the school-house, and thought of the singing drone of the children whom he taught. His eyes wandered away to the glowing terrace of Monte Carlo, and came back to the little station and its signal-lights at his feet, although the Mediterranean slept about the pines of Cap Martin, and the stars above his head had never shone brighter.