RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

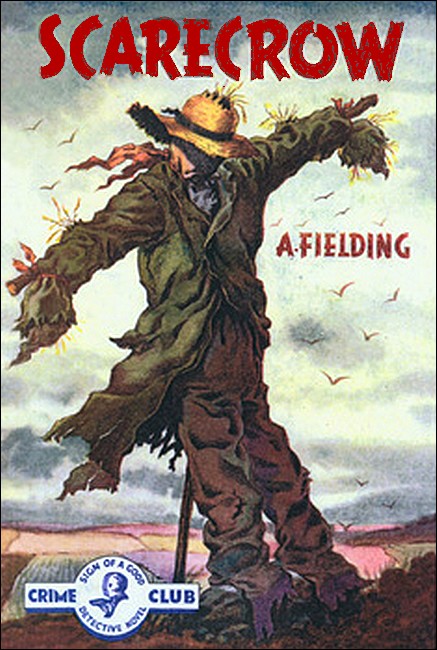

Dust Jacket, "Scarecrow,"

The Crime Club, Collins & Sons, London, 1937

Cover, "Scarecrow,"

H.C. Kinsey & Co., New York, 1937

"JACK you're infernally lazy." Florence Rackstraw, hands on narrow hips, looked at Inskipp with an air of impatience. "Come along. The walk back will do you good."

It was now nearly five o'clock.

"I don't need to be done good to," murmured Inskipp, his felt hat tilted over his eyes. "I'm perfect."

"Same here," said Elsie Cameron drowsily. She was seated on the rocks beside him. "Don't let us keep you, Florence."

Florence shot Inskipp an angry look. He caught it and closed his eyes promptly. Her brother joined the little group of three on the Menton promenade.

"Well, haven't we dallied long enough in Babylon?" he asked, shifting a handful of stones to another pocket.

"In Bosio, you mean," chaffed Elsie. Honoré Bosio keeps the best cake shop in Menton, and the Rackstraws loved a good feed.

"Shake a leg, Inskipp," adjured Rackstraw. "I want to discuss an episode in Haroun with you."

Inskipp yawned. The two were writing a scenario. They were to share the profits of the film between them, and each talked as though they had a gold mine under their hats.

"Haroun is tired," announced Inskipp firmly. "Very tired. He won't be at home to visitors until to-morrow. Besides, Elsie and I are going to drive up to the farm with Norbury."

"You are an idler," said Florence with a nip-in of her thin lips, as, with a wave of the hand that looked angry instead of friendly, she led the way at a good pace along the Promenade du Midi to where the road started that would bring them after a three hours' ramble to Norbury's farm, La Chèvre d'Or, high up in the hills behind Menton. The four were his paying guests.

Elsie and Inskipp watched them disappear.

"There, but for the grace of God—" murmured Inskipp unctuously.

"I don't think any one should be as ugly as those two are," said Elsie. She spoke meditatively, objectively. She was an artist, and, incidentally, a very pretty girl.

And as though to give her another look at them, the brother and sister suddenly reappeared, walking briskly towards them. As usual, Florence Rackstraw was in the lead. She was very tall. Her head was too large for her bony body, and seemed to be all face, a face the colour of mottled mahogany. Her hair, straight as that of a mouse, was looped in two curtains over her ears and gathered into a tight little bun on her long, scraggy neck. Her eyes protruded. Her chin retreated. Her nose was hooked. Her mouth consisted of two thin, pale lines that slanted up to one side.

Her brother resembled her closely, with rougher features, and a still harsher voice. He, too, had her air of absolute self-satisfaction.

"As you're driving with Norbury, take these up for us, will you." The coats were tossed at the two before they could reply. Then the Rackstraws wheeled and strode off once more.

"You're treading on dangerous ground when you talk of ugliness to me," said Inskipp meaningly. And he certainly could not be considered handsome.

"But you're honest," objected Elsie at once. "You're straight, You can't be ugly when you look that. That's what I'm trying to get at, I think, that it doesn't matter if you look ugly, as long as you don't look as though you really were ugly—you yourself—in yourself."

"That's a bit difficult to grasp," said Inskipp with a grin that showed his strong teeth. "That's too much in Laroche's line for me." Laroche was a Frenchman, a writer of psychological studies, who was also staying at the Golden Goat.

"What I mean is that I think only ugly thoughts can make faces so plain. The Rackstraws look mean and malicious—and I think they are both those things."

She spoke with her eyes on the incredible blue of the sea in front of her. Inskipp altered his position to face her more directly. He was a young man, and Florence Rackstraw' had made a dead set at him when he had first come to the farm two months ago. He had drifted into a quasi intimacy with her before he saw his danger and struck out for safety.

"They're very intelligent," said Inskipp a trifle awkwardly. "Very clever."

"They are," agreed Elsie in a tone that said that that quality counted for little. "But they could be very dangerous, both of them."

"In what way?" he asked.

"I haven't the faintest idea," was the prompt reply. "I don't reason about people. I feel them. And never, never make a mistake," he finished with mock solemnity.

"Never when I dislike people. It sounds cynical, but it's true. It's only when I like people that I may be all wrong."

They were lounging on the Promenade du Midi, that broad walk that runs along the sea at Menton, sometimes with neither parapet nor railing to protect it from the water. A grand walk when the sea is rough, and the green waves come roaring in over the foundations of the wall. White wings were wheeling and circling over their heads. One gull, more adventurous than his mates, nipped the bread from Inskipp's fingers in his swift glide past, banked—a lovely flash of silver—and came back for more. The hot sun flooded everything. The air was cool and fresh. The sea ran in broad washes of deep blue and bright green. The sky was the true sky of Menton, high, and blue, and soft, and deep. The donkey and ponies, kept at a corner of the casino for children to ride, stamped a little. They were as bored as Inskipp felt. A few notes from the orchestra playing outside the casino reached them. It was all like a scene at a theatre, Inskipp thought, something which he watched, but in which he had no part. As for Elsie, she was at grips with a curious, a quite contrary feeling to his. It was as though something were trying to rouse her to a sense of the moment's importance. She got up, ostensibly the better to watch the gulls whirl overhead, in reality to give herself room. What was this sudden impulse which was sweeping through her as the gulls swept through the air around her—an impulse to fight and win the man beside her, a sudden awareness of powers within her which, if used—of qualities which, if shown—would draw John Inskipp to her side and keep him there. He was a lonely man. She knew herself to be his complement. Should she make him realise this? She could. She knew that she could. What she did not know was that the fate of Inskipp depended on that moment—that Atropos with her shears paused for a second to wait for her. Had she obeyed her innermost craving Inskipp would have been saved. But, unfortunately, Elsie came of a race of women who were won, not who did the winning. She told herself the truth, that she cared for him much more than he did for her. She flung off the odd feeling that the moment held some opportunity which would never come again—and turned to see a man hurrying towards them along the promenade.

"Here's Du-Métri," she said in a welcoming voice.

"Two-Yards" was the nickname of the Norburys' factotum. A tall wiry figure, he came swinging along the Promenade from the nearby Halles. "Ohé!" he hailed, and waved a long, lean arm. Elsie liked the man. Two-Yards was a character. She sat smiling as he strode up and made a jerky little bow. "Il padrone sends this message," he said, drawing himself erect. "Not to wait for him here, as he must go to Gorbio. He will have to pick you up at the old Carnoles Olive Mill."

Two-Yards looked as though carved from pliable teak, his features were so salient, his colouring so uniform and dark a brown. His lean, clean-shaven face was good looking, with regular features, and dark eyes that were at once keen and veiled. He knew every star that hung in the Menton heavens, and he knew their courses, the hour of their rising and the time of their setting. He knew all the flowers of the fields, and the birds in the woods, as he knew his own herds. Born in the hills behind Hyères, Two-Yards was steeped in Provençal legends and folk-lore. It was from him that Inskipp had first heard the legend of Haroun, the Moslem Corsair who had turned Christian for love of a captive maid.

"Are you coming up to the Mill, too?" Inskipp asked.

Two-Yards threw up his chin in sign of negation. He had still some purchases to make for the farm, and would follow later in the day in the farm cart. His eyes on the horizon, he stood a minute looking out to sea.

Leaning far out of a boat painted green and yellow, a fisherman was beating the waves with all his strength, and at the full stretch of his long arms.

"To drive the fish into the net," Two-Yards said in reply to Elsie's inquiring look.

"Is there anything you don't know, Du-Métri?" she asked him.

"Yes. I don't know who gives my Sabé her silk handkerchiefs," he said suddenly.

Sabé—short for Isabella—was his daughter. She was a flirt, and Du-Mari was a Spartan parent.

"Well, I must be off." And he took his cap off again, while Elsie laughed silently.

The two caught the next Gorbio bus and were whirled along to the old mill at its opening.

Green and cool and very lovely, the road wound past gardens where geraniums hung in thick mounds the size of cartwheels on the stone walls, or climbed half-way up the trunks of the palms, where roses and carnations filled the air with fragrance, where the bougainvillea covered walls and roofs with its magnificent purple. They got out at the Old Mill and sat down to wait for Norbury on the rocks which dot the entrance to the little hamlet. The ruined Maulesséna Castle was to one side, the great new sanatorium was hidden by a group of olive trees fifty feet high. Where they were sitting, they had pines on one side and palms on the other. It was typical of this corner of the world. The rustle of the palm fronds sounded like heavy rain in the breeze. Below them lay Menton looking what architecturally, as well as historically, it was—pure Italian, as it curved around the Gulf of Peace, a horseshoe of emerald and cobalt. Eastward, two lines of lavender and violet mountains carried the eye to Bordighera, whose houses glittered like dice on the farthermost spur of land. Up here, one even caught a glimpse of the Gulf of Genoa on the other side of the first line of purple hills, like a stroke of sapphire. To the west, the green ridge of Cap Martin ran an arm into the sea with one white hotel catching the light.

Elsie drew a deep breath. Things must surely come right between her and Inskipp in such a world. And if that was not to be, then beauty such as this can fill the heart like love. The sunshine flooded all her being, luminous and strong and vital.

She crumbled some of the earth between her fingers. "It's wonderful soil. You've heard, of course, of the man who, by an oversight, left his umbrella sticking in the ground hereabouts. When he went to look for it a week later, he found it a small tree in full bloom."

Inskipp laughed outright.

"Did Two-Yards tell you that one?"

"No. Mr. Norbury." Getting to her feet, she looked about her, her felt hat in her hand.

"I don't think there's anything in the world more beautiful, in its own way, than is this region." Her eyes were shining, her whole little face alight and glowing. It was a whimsical, irregular face under a mop of tawny hair that had streaks of red, like flames, in it.

"I suppose not." After a pause Inskipp added. "But it doesn't mean anything to me. Does it to you?"

"Mean." She was puzzled, and her transparent, candid face showed it.

He made a vague gesture. "It's lovely—as a set scene at a theatre is lovely. But it's not real—to me. Palms—they can't take the place of beeches. I'd rather look at an oak than an olive, any day—"

"And you'd rather watch rain than sunshine—is that it." she laughed. "Nothing like patriotism!"

But he was not laughing.

Inskipp's sallow face was a melancholy one. Something about it suggested the seeker who had never yet even caught sight of anything worthy of his search, the visionary who had never yet had a vision. In age, he was under thirty.

His brow was narrow and low, not the brow of a clever, or even of a well-read, man. His dark, deep-set eyes were his best feature; they were unsatisfied looking, but well cut and well opened. His nose was thin, with generous nostrils, his mouth also suggested generosity as well as firmness, his chin was dogged and masterful. Elsie's quick eyes had put it down correctly as the face of a dreamer; but Inskipp did not look at all like a dreamer who could not be wakened. You might fool him without any great difficulty, possibly, but most assuredly you would have to pay for it afterwards if he learnt the truth. He was under medium height and slenderly built, with a narrow chest which was the reason for his being out of England. A bad attack of pneumonia had sent him to Menton, and a chance stroll up among the hills had suddenly brought him, some eight weeks ago, to a low Provençal farmhouse. Twin cedars stood at the gateway—one standing for Prosperity, one for Peace. Its roof was of the red, fluted Provençal tiles, its garden hedges were of rosemary and juniper and lavender.

Inskipp had spelled out the farm's name on the gate, and wondered at it: >La Domaine de la Chèvre d'Or. Two-Yards had seen him, and promptly asked him to hold the gate open for a pig which was intent on double-crossing him. In the pig-hunt which followed, Inskipp, Two-Yards, the pig, and a tall, rangy man of middle age who swore heartily in English, all got thoroughly well mixed up. When the pig was back where he belonged, instead of where he wanted to be, the Englishman introduced himself as the owner of the farm, and asked Inskipp in to taste some of his new wine. Inskipp met the other guests who were staying at the place, and had promptly arranged with Two-Yards to fetch his things from below. He had not regretted it. The farm was simple, but it was cheap, and the scenery was magnificent.

Inskipp liked Mrs. Norbury, too. So did Elsie Cameron, who had been at the farm since early spring. She, also, had to spend the winter in warm and sheltered nooks, and the farm was securely tucked away alike from Bise or Mistral.

Norbury's yodel came ringing down the green valley above them. Inskipp answered with one of Two-Yards' strange shouts. Such a shout as the Provençal herdsmen give at dawn and at nightfall. A shout which has come down from the Phoenicians, said Laroche. It stirs the hearer strangely. Some old tumult of the blood beyond our present-day reason or understanding answers it. Elsie never listened to it without a feeling that the enemy tribes were at the stockade, that javelins were flying around her.

Norbury drew up his Ford close to them.

He was a big, sunburnt man in the early forties, with a pleasant enough but very non-committal face, out of which would come at times a glance, chill and keen as a north-easter.

They clambered in over bags of flour, sugar and salt. Then they were off.

"How's the marketing been?" asked Inskipp as they had to slow down for a herd of cows.

"So-so," was the reply. "They say the weather is going to break. Hope it won't, or it'll be a bad look-out for my oranges."

Norbury had not many oranges on his farm, but he overlooked no source of profit, and an orange-tree bears easily three thousand oranges in twelve months, and choice ones yield four times that.

It did not take long to reach his Domaine, or farm, and for a moment the three of them looked down at a sea of grey-green olives which hid the lemons and vines planted below them.

Norbury's chief source of income was from his lemon-trees. The Mentonais claim that Eve's last act when leaving Paradise was to pick a lemon to carry with her. She decided to give it to the most beautiful country which she and Adam should find on their wanderings. When she came to Menton, she flung it on a terrace, telling it to grow and multiply and turn the land into another Garden of Eden, which—according to the legend—it promptly proceeded to do.

Norbury called for a couple of the farm hands to help him unload the car, while Elsie and Inskipp walked round a corner to the house. As they did so, a good-looking young couple came sauntering up to the open door. The woman in front, with something very graceful, though weary, in her gait. Edna Blythe always walked like that, though she never seemed to go farther than the nearest sunny corner. She was a tall, slender woman, not pretty, exactly, but with something about her rather sad, very bored-looking face that suggested that she could be pretty if she chose. She was fair, with fine brown eyes, and a low forehead. Her features were well cut. A straight nose, a small, curiously tight mouth which yet looked as though when relaxed it could be very sweet, an obstinate little chin, and a firm jaw. Her hands were nervous and suggested illness.

Her brother, who followed her in, was tall and fair, too. Otherwise there was no resemblance between them.

Mrs. Norbury joined them with one of her ginger cakes which she wanted to put out of doors to dry off. She rated Norbury sharply for letting the car cut across the grass. Inskipp sometimes fancied that her big burly husband was a little afraid of his dot of a wife, and indeed Mrs. Norbury could be very forthright and unbending at times. There had been that affair of the Italian count and the lady he called his wife just after Inskipp's own arrival. Mrs. Norbury had learnt from the young man himself that he and his companion were not yet married, though they intended to have this done soon. The car took the two down to Menton the same day, Mrs. Norbury driving, and looking calm and unflustered, in spite of the fact that the count and future countess on the back seat seemed to have turned into two geysers.

"If you tolerate a thing, you aid it," was her only comment on the matter, in answer to a chaffing remark of Rackstraw's, who thought her attitude distinctly comic.

She asked Inskipp and Elsie about Menton as she carefully set the cake level.

"It was very close," said Inskipp, "and very enervating."

"As always—" threw in Elsie.

"And as always," he went on, "full of Voronoff's patients, or would-be patients."

"We women score when it comes to old age," said Mrs. Norbury meditatively. "We accept it more placidly."

"Not while there's a paint-pot to be had!" retorted Elsie, laughing.

"A woman has to accept so much," Mrs. Norbury maintained, "that old age seems a trifle." She spoke bitterly. Her voice was bitter, too. But, then, Mrs. Norbury did not have a pleasant voice at any time. Over the telephone, that tester of tone, it sounded very hard always, and could sound distinctly grating.

FOR Inskipp, the next fortnight was one of outward peace and inward battle. He won. At the end of the time Florence Rackstraw treated him as a very unpleasant insect, and Inskipp was glad. He had found it harder than he thought to get out of the atmosphere of the suitor in which Florence had very subtly wrapped him and all his words. He had had to be really rude at the last to cut the cord which, she insisted, linked them. Elsie had watched his struggles with approval, but with no overt help. She told herself that, as he had got himself into the false position, he must get out of it by himself, too. But when he was out, he was no nearer to Elsie.

One night, when the other men were off helping to drive some young bulls to Castellar, whence they were going to be sent to Arles and Nimes for the bull fights, he and Mrs. Rackstraw had sat talking on the verandah. Oddly enough, Mrs. Rackstraw had been Inskipp's secret ally in the struggle with her daughter. Inskipp had thought more than once that she had no love for either of her children. Had he known the story of her life with their father, and how much these two resembled that unpleasant gentleman, now dead and buried, he would not have been astonished. As it was, after Inskipp, beguiled by the singing of the nightjar in a nearby tree, and by Mrs. Rackstraw's words on companionship had drifted into what was practically a description of his ideal woman, Mrs. Rackstraw had said significantly:

"I know a girl who fits that description of yours, Mr. Inskipp. All but the loveliness, which you think means a beautiful soul—and that's Elsie Cameron."

Florence Rackstraw, who had slipped unnoticed into a chair in the corner, sat very still.

Inskipp was amused. How little people understood, he thought. Here had he been indiscreet enough to give a glimpse of his heart's ideal, and what he showed had been identified with Elsie Cameron Elsie was a nice girl, a very nice girl. He would be a lucky chap who would win her one day for his wife; but as to her resembling the dream creature he had described—Inskipp gave a suppressed smile, then he made for his own room. He wanted to jot down his impressions of the herd of bulls this evening as they had gone roaring, stamping, snorting down the valley. Just such an incident could have happened at the castle of Anna's father—Anna was the Christian maid who had converted Haroun to Christianity, said the tale. Inskipp had never up till now written anything, but he was bored at the farm, and boredom is the best incentive to writing.

He had worked for about an hour, when a knock came at his door.

In answer to his curt "Entrez," Florence Rackstraw came in.

"I've got something that would fit wonderfully into your film," said Florence. "It's in a book on Provence castles—an old French book that I picked up in Menton last time we were there. I've been reading it."

A week ago Inskipp would have made an excuse but she had altered—she had retired defeated, and he followed her without another thought to the large room which the Rackstraws used as a sitting-room.

"Light your pipe, and I'll get it," said Florence as she stepped on to her own bedroom. "Matches are on the mantel—" she called back. Her tone was friendly, though detached.

Inskipp strolled to the fireplace, where some logs of olive wood were still smouldering.

He suddenly picked up a photograph standing by the clock. He had never seen it there before. He had never seen it anywhere before. This lovely oval. This beautiful small head set so proudly on its slender shoulders.

He still had it in his hand when Florence came back.

"Isn't she beautiful? She's my greatest pal! And she wants to go into a convent when she has secured her divorce!"

"It's the loveliest face I have ever seen," he said slowly.

"And as good as she is beautiful," Florence said warmly. "I want her to come here. It would do Mireille good to have to interest herself in the affairs of this life for a while. She is too unworldly."

"Mireille." Inskipp repeated questioningly. What a charming name, he thought.

"Yes. Mireille de Pra is her name. Madame de Pra. She was married some three years ago, but she never lived with her husband. He had a fit as they were walking down the aisle after the wedding; he rolled right off the steps, they say—I wasn't there—and for a while they thought he was dead. But unfortunately he wasn't. For when he came round finally he was raving mad, and has remained mad ever since. Isn't it terrible!"

"It's a crime—marriage such as that." Inskipp was fairly stuttering.

"I have another photograph of her. Would you like to see it?"

Florence felt in a drawer and handed him a portrait as lovely as the other, if not more so, for it showed a figure as beautiful as was the face. It showed the same girl—she looked barely nineteen—in what seemed to be a convent garden bending over a great spread of Madonna lilies. Inskipp's heart contracted, and expanded, and did all sorts of queer things inside him.

He said nothing, only looked at the two photographs.

"She has to stay in the convent in Brittany for the present," Florence went on. "But, then, frankly I'm not keen on Harry meeting her. He isn't her sort at all, and it might spoil our friendship. I usually keep these photographs safely tucked away for that reason. He doesn't know about her, and—well, I don't see why he should. He may have left here before she comes."

She put the photographs carefully into a drawer. Then she showed him the book with the descriptions of the old castle that had interested her. Inskipp barely understood what she was saying, but he thanked her effusively, and, taking the book, went out of the room, his head in a whirl. He felt like a man who has most unexpectedly stumbled on a treasure. A sense of excitement filled him, an impatience for the weeks to pass till that wonderful creature should stand before him in the flesh as she stood in the photograph. He felt as though the world were a marvellous place, as though to each of us had been offered a ticket in a wonderful lottery. The feeling stayed with him next morning when he woke up. But as he dressed, and when he sat down to his writing, doubts began to rise. He told himself not to be a fool. Girls such as that one in the photographs would not give him a second glance. Or even one. He laughed aloud in scorn at his ugly, dull self.

"Glad you're in such a cheerful mood, Inskipp," said a voice behind him. "The fact is, I was wondering whether you would help me out again—just for the next few days. I don't like to keep the Norburys waiting."

Rackstraw had come in through a side door.

Inskipp took out his pocket-book. A bit over two hundred francs should settle Rackstraw's debt to the Norburys. Inskipp was anything but a wealthy man, but he had set aside a thousand pounds for odds and ends when he had invested the remainder of his money. So far, he had spent very little of it. Money could not buy happiness—could not prevent acute loneliness, for bought companionship is no companionship. Inskipp had tried that out thoroughly already.

"I'd ask the Norburys to let it run on for a bit," Rackstraw said, "but they're having a hard time to make ends meet, let alone lap."

Inskipp said that this was news to him.

Rackstraw made a little face.

"It wouldn't be if you slept in my room. Mrs. Norbury wants the money back that she put into the farm, and Norbury can't run to it."

Inskipp handed over the notes now, but he had an uncomfortable feeling that Rackstraw was meditating a further request for a loan. Something biggish. He fancied that Rackstraw had been trying to get up his courage for it for some days.

He slipped away out of doors. The orange trees were too compact and tidy for his taste. Inskipp preferred lemon trees. By the back door was a charming specimen. A sudden desire to paint it came over him. He could sketch in an amateurish way in water-colours, and he went indoors now for his sketching-block, and box of colours. He chose his pencil carefully, and set to work.

Not for him was the one-line of the real artist, but by patient work he achieved a very accurate drawing of the little tree. Its beauty grew on him as he studied it. Its airy grace, the delicate spacing of its fine leaves which decorate but never hide branch or fruit. Its shape as it grows older is much like that of a pear tree, but the abundant, daffodil yellow fruit hangs so clear of branch or leaf, that it, seems to be backed only by the bright blue of the sky, and against that sky the effect is enchanting.

Inskipp enjoyed the work. Unlike the writer, the artist, however poor, finds that if he is patient he enters into a life within life, a world within the world. Colours become more than something seen by the eye—they have a meaning—they have a magic—

Inskipp decided to put in the kitchen door, the maize field with its tassels and the scarecrow that stood in one corner, and a tiny lemon sapling which grew at the base of the second lemon tree, with its little fruit the size of an acorn, but perfect in colour and shape, dotted like fairy lamps all over the slender branches.

"Tiens! You sketch? Well, perhaps?" It was Monsieur Laroche, sipping a glass of Chateauneuf du Pape. As for the local stuff, Laroche maintained that it was not wine at all, but merely vinegar in the making.

Monsieur Laroche repeated his remark. His mother had been Irish, and he spoke English as though born in Dublin.

"Why should I not sketch?" Inskipp asked, putting his drawing away.

Laroche had a way of making him feel as though he were under a microscope, than which there is no sensation more distasteful to a Briton.

"I agree that it is in character." Ah, there he was again! Laroche could talk by the hour on what was in a man's character and what was not.

Miss Blythe came towards them.

"Has the noon-gun gone yet?" she asked. They all set their watches by the cannon fired from Menton fort.

Inskipp thought she had a pretty but rather vacant face. She was very dull to talk to, very heavy in conversation, and she had a habit, which embarrassed him, of listening with her eyes rivetted intently on the speaker, as though she would never see him again, and the memory of each feature and of each expression might make all the difference to her own future.

The gun boomed. Miss Blythe set her watch, and passed on.

"What's her character?" he asked Laroche under his breath as the Frenchman stared meditatively after her.

"Ah!" said Laroche between his teeth. "That is the thing she hides with all her skill. But I have my ideas!"

Inskipp was amused. Poor quiet, dull Miss Blythe!

"I can't think what you see of interest in her," he said truthfully.

"I see a most uncommon sight," said Laroche almost sadly. "I see a person afraid of themselves. Yes, just that. Not, as I thought, merely afraid to show herself to others, but afraid of some weakness—or some impulse—in herself. I suspect drink," he said finally.

"Mind you," said the writer apologetically, "that is only a guess. Chiefly because of the choice of this farm. No temptations here. Mr. Norbury keeps no cellar. His eau de vie is only useful as an embrocation. The farm had its own still, a perfectly respectable farmhouse appurtenance in France, where every windfall finds its way ultimately into it. "I wish I could dear her up," he added, "but it might take years."

"How about asking her brother?" suggested Inskipp.

The Frenchman considered a moment, then he shook his head. "I think not. He is born a bully under his varnish of the public school. And, by the way, how he avoids saying what school he was at."

A sound of voices made them look up. Rackstraw and Du-Métri were walking together towards them. Mrs. Norbury was behind them.

"Another painter! Here's Du-Métri with a pot." Laroche stepped aside to avoid its swing.

"For the Golden Goat," said Two-Yards, with a gleam of his strong teeth, making for the gate, where he began to repaint the name. As he did so, he started one of his songs of which the refrain was:

Apres aco, su anac. (After which I left.)

Laroche listened to it with delight. He wondered what Mrs. Norbury would say if she could understand the words of the Rabelaisian old ditty.

Mrs. Norbury, as it happened, was thinking of the painting that was being done, not of the song.

"I do so dislike the farm's name." She looked at the gate frowningly. "I wanted to change it to Lou Lavandou, or Las Mimosas. Provençal names, too, both of them, but you can't change things in Provence. Not even though the last owner was gored to death in a field over there by one of his bulls."

"But the name wouldn't alter the luck, surely." Inskipp's voice was amused.

"It's supposed to be unlucky," said Mrs. Norbury shortly, turning back into the house, "but my husband doesn't believe in luck."

"I thought La Chèvre d'Or is a beneficent creature who guards the hidden treasures left by the Saracens," said Elsie, who, together with Rackstraw, had come out after Mrs. Norbury.

"And I thought he was the defender of Provençal relics, butting away the archaeologist who got too close to anything interesting," said Rackstraw.

"One of its duties, certainly," allowed Laroche. "That Chèvre d'Or is evidently in the pay of the Department of Public Works. But he has another side. A more mysterious side. He is also The Unattainable. The Impossible-to-realise. And to see that Chèvre d'Or is to die shortly afterwards."

"They would get that side of him from the Greeks, who settled all this part of the coast and built their temples and theatres here," said Rackstraw, who was an archaeologist.

"Yes, in many places he is Pan. But he is other things, too. A blending of many old superstitions." Laroche made a gesture as the luncheon bell sounded. "Unless you are a Provençal—and even then—it is better to leave the mysterious creature alone."

BY the end of the month Inskipp was corresponding with the beauty of the photograph. It came about through Florence having come down one morning with her hand and arm in a sling. A bad attack of neuritis, she called it. She sought him out later in his room, and explained that she was sending some flowers to her friend Mireille de Pra, and now could not write the letter for her birthday that should go with them. She did not care to ask her mother to do it for her, for, as Inskipp knew, she did not want Harry to get to know Mireille, and she could not ask her mother to keep the letter a secret.

"He would fall in love with her. She would loathe him. And our friendship would never be the same again," she said for the second time. "Would you write a letter to my dictation?" she asked, and Inskipp, trying not to flush with pleasure, said he would be happy to do so.

"It must go by the afternoon's post," she told him, and suggested three o'clock for the work, but at two she looked in to his room to say that she had a raging toothache, and was going to drive down to Menton to have the tooth out. Would he write instead, and explain that she—Florence—had a bad attack of neuritis Mireille knew that she was subject to them.

Inskipp had spent a whole afternoon over the letter until it was a monument of the stilted and the stiff.

He received a charming reply, but all too short.

As a reply to this reply, Inskipp ventured to send a basket of mimosa, accompanied by a little very carefully written note entirely about Florence and the farm.

He received another charming letter, and a very delightful correspondence started, though on Madame de Pra's part the letters were all too brief, and not very frequent. Yet, even so, they brought an unaccustomed look of happiness to Inskipp's face.

In the first ones, Madame de Pra had written as to an elderly man—an invalid—and Inskipp had hardly dared speak of his real age, but he had done so. The interval that followed this had been longer than the first one, and the next letter from Mrs. de Pra was very short and stiff, but that coolness was now wearing off, and when they met it would be without awkward explanations. As to when that meeting would be, Mireille said that when she had finally obtained her divorce she wanted a long change up on the hills that she knew so well. Florence had told Inskipp that Mireille was born in the Esterels, the daughter of a small proprietor named Briancard, a scholarly man, who had paid too much attention to his books and too little to his land. His wife, an Englishwoman, had died a year after the marriage of Mireille, their only child, and Madame de Pra was now an orphan.

Florence made no secret of her hope that Mireille could eventually come to the farm, and Inskipp made no secret of his sharing that hope. He wondered how he could ever have disliked Florence as he had just before his break with her. Evidently he had taken her far too seriously. Evidently it had just been a whim of hers—passing—quickly forgotten—to try to make a fool of him.

Even at the time of his break with her he had thought that it was love of domination rather than affection. He was sure of it now. Yet there was another side to Florence, and this morning it was very charmingly in evidence. She had used some phrase that had startled him, for it was word for word what Mireille had written him in his last letter. Seeing his start, Florence had at once explained that she had heard the sentence from Mireille herself apropos of the bond between a writer and his pen. Arid from that she had gone on to talk of Mireille in a way that enchanted him. He diffidently told her what her friend's letters meant to him, what character, what heart they revealed. Florence listened with a very soft loop on her face—a look that touched him.

"I believe you would have fallen in love with her from her letters, even if you had never seen her picture," she said finally, turning away to choose her gloves.

"No," Inskipp said honestly, for the vision of that lovely face was ever with him. And on that he now ventured to ask her if he might have one of the photographs of Madame de Pra which she had. Florence refused absolutely and curtly. Inskipp told himself that he had roused her jealousy as a friend. But Florence explained that she would feel it to be treachery to Mireille to hand on her picture to any one else. "But if you ask her, she might send you one. Perhaps a later one still," Florence said, turning at the door. And Inskipp realised afresh how ugly she was.

He thought of what Elsie had said. Theoretically he, too, held that faces are records of thoughts and emotions, but poor Florence's face was surely just a freak of nature.

"Upon my word, Inskipp," said Laroche, as he and Rackstraw came on him a moment later. "I think you have had a glimpse of golden hoofs and horns, eh? You look as though you had. If so, beware!"

Inskipp flushed.

"I think he has seen Mireille," suggested Rackstraw with a grin. "I don't mean the film of that name I meant the damsel herself."

"Then you have met her." Inskipp said instantly.

The two men roared their amusement in great peals. As for Elsie, she had gone on into the house.

"Touché!" Laroche ejaculated, laughing afresh. "Ah, Miréio! If a lady is the reason, then indeed—!" And he threw up his hands.

"What are you two talking about?" Inskipp was vexed. "You mention a lady's name whom I don't think you know." He looked at Rackstraw questioningly. "And you and Laroche seem to think I've made a special-sized joke."

Rackstraw hastened to apologise. "Sorry, my dear chap, sorry! I don't know the lady. I merely mentioned the name of Mistral's famous heroine as a chance explanation for your look of general content these days. I've evidently hit some mark."

"Mistral? That's the damned wind that gives every one the pip, surely?"

"It's also the name of the great Provençal poet—Frédéric Mistral. Or was," Laroche explained. "His Miréio is a Provençal epic. Though personally I prefer Calandau. But Miréio is Provençal for Mireille, the name of his heroine, a name used long before his day for any pretty girl."

"I only meant that you must have met some village charmer—no offence, Inskipp." Rackstraw was feeling very amiable this morning.

Inskipp was already appeased. He Was glad to be assured that Harry Rackstraw had never met his sister's lovely friend, and he hummed to himself as he too went indoors.

These were the days of the grape harvest. The weather was ideal. The sunshine poured down on the vineyards, the countryside rang with the singing and laughing of the grape gatherers; yet Norbury looked very glum, and said openly that but for his guests he would not have been able to carry on. Only Mrs. Norbury, apparently unruffled as ever, cheery as ever, saw to the housekeeping with undiminished efficiency.

"If Mrs. Norbury feels so cheerful, I needn't be in a hurry to pay last month's accounts," Rackstraw said to his sister.

"Mother left you the money to settle for her," said Florence with a sudden frown. "Where's the receipt? I'm writing to her. I'll enclose it."

Mrs. Rackstraw had decided to go to a married daughter in Rhodesia who had had a bad accident and was stranded with no one but a couple of children to help her. It was not money but physical help that was needed. The mother had left over a week ago. Florence had refused to accompany her. She had a tiny income of her own, and the expenses here at the farm were low enough to let her live on it without working. She was by profession a librarian, and had worked as such in South Africa, where she was born.

"I'm writing to her, too. I'll send it." Her brother spoke shortly.

"I don't believe you've paid up yet. Mother ought to have given the money to me," Florence said in her most superior tone.

"You'd have forgotten to settle, in your new campaign against Inskipp," he retorted.

"My new campaign?" she asked loftily, arranging her hair.

"My dear girl, I've known you for over thirty years, remember! Those letters to that old witch in Rennes, Mademoiselle—what was her name—the housekeeper who used to be at that awful boardinghouse in Paris when we were there. Don't you suppose I know you're up to something? And something which will pay Inskipp out?"

There was a short silence, while Florence chose a walking stick. She was off for a long scramble.

"Whatever you're at, has slowed up his output," Rackstraw said, lighting a cigarette.

She smiled a slow, very unpleasant smile. By Jove, Flo was plain, Rackstraw thought as he caught it. How on earth she ever expected to marry—

"He'll be writing better than ever soon," she promised in a curiously amused voice.

"I didn't say anything about its quality—quantity, too, counts. As a matter of fact, in the last scene of his he got the love-talk far better than in his opening one."

"Well, there you are!" said Florence, laughing a little under her breath.

"What can you have done that makes him look as though he had been left a million?" persisted her brother. "And who is this friend of his called Mireille?"

"How should I know? Mireille? Sounds a fancy name," she said innocently.

He gave her a suspicious look, but she began to sing in her hard, nasal voice, and led the way through the garden. She and Blythe were walking over to Castillon. Rackstraw was off for Menton, there to be rowed out to the Baoussé Roussé, the famous Red Cliffs just over the Italian border where fifty thousand years ago paleolithic man lived—in bodily shape very much like his descendants, where the women wore shell bracelet jewellery very much such as can be bought at the local fairs.

The other two might join him later on, and all three come home together, or they might not get so far. Rackstraw never waited for any one.

Since Inskipp's resolute withdrawal, Florence had turned her attention to Blythe, with what success it was hard to say. Certainly Edna Blythe seemed pleased. Edna was an indolent person who spent long hours extended in a deck chair in the garden.

Whenever visitors came in for a drink, and they were fairly frequent these fine days, and she was out in the garden, she would envelope herself in a Times until the visitors had been shown to their rooms. Once, Inskipp happened to pick up her paper after it had been serving her for some time as a screen, and was amused to find its centre neatly pierced by a large pinhole. So that wrapped-up aspect concealed quite a good observation hole; but he dropped the paper again without giving the matter a second thought.

Blythe could be heard now calling. "Miss Rackstraw! Miss Rackstraw!"

His sister looked up and chaffed them as they set out, lunch in their shoulder-bags, stout sticks in their hands. Florence laughed back at her, and waved her hand to Inskipp up in his window.

He promptly sat down and started a letter to Madame de Pra far away in Rennes. A very humble letter, asking her if she could let him have a photograph of herself. He did not say that he had seen those in Florence's possession, but he did say how much he would like to have a picture of the writer of the enchanting notes which were his greatest joy in life. It took him quite half an hour to write, and he posted it in the nearest letter-box to the farm.

It was while walking back that he caught sight of some one—a man—waving and shouting and running. Inskipp waited. A minute later he saw that the man was Blythe. He hurried to meet him.

"It's Miss Rackstraw!" called Blythe, as soon as he got within talking range. "We must get something to carry her on—"

"What's happened?"

Then as Blythe, who looked very pale, did not reply, Inskipp went on: "Has she hurt herself?"

"She's dead." Blythe spoke in a tone as though overwhelmed by the calamity. He looked ghastly. "I'll tell you all about it in a moment...As soon as I've seen Edna...When I get my breath...Back at the farm..." He seemed uncertain where to tell it.

The two, without another word, hurried to the house. There they met Norbury mending the front gate. Blythe grasped his arm.

"Get a stretcher of some sort. Miss Rackstraw slipped off a rock, and is lying dead in a valley near here. Where's Edna?"

"Hold on a moment," said Norbury. "One at a time. Miss Rackstraw slipped? Where? How? But you need a whisky and soda."

Blythe did. Drinking it, he pulled himself together. They were walking in single file, he said, Miss Rackstraw leading, along a narrow ledge of rock, when suddenly a huge roar sounded behind them—a roar like nothing on earth, said Blythe.

Startled, Miss Rackstraw missed her footing. She plunged over the ledge before Blythe or the man who was leading a baboon by a strap, and who had sat down to rest by the roadside, could put a hand out to grasp her. Blythe had clambered down after her and found her quite dead with a broken neck, as well as broken back.

"Good God!" muttered Norbury. "What a shocking accident. What became of the man and the beast?"

"I told him to wait by the body. The baboon was on its way to the Château Grimaldi, of course."

"I suppose you stopped at the Commissariat de Police to tell them about it? It was on your way here," Norbury said, hurrying back with them to the outbuildings.

Blythe had not. He seemed to have no idea where the Castellar police station was.

Norbury shook his head again, and said that they must go there at once. The police would attend to bringing up the body and getting into touch with the man who had the ape. "I suppose you can describe him?"

Blythe said that he was afraid not, beyond that he was middle aged, very dirty, dressed in innumerable garments all more or less ragged, and that the baboon was a big one.

Norbury pursed his lips over this, and again said that the only thing to do was to start at once for the police.

"I want a word with my sister first." Blythe made for the stairs.

"My dear fellow," said Norbury in his most peremptory manner, "you mustn't wait a moment! You must let the police know at once!"

"I must tell Edna!" said Blythe in a dogged tone. "She was a great friend of Miss Rackstraw. I want her to be prepared. The shock, you know—"

But Miss Blythe was not at the farm, and Norbury peremptorily refused to let Blythe try to find her outside. He dragged him almost by force to his car.

Inskipp was genuinely shocked at the news, but then came the thought that now the' two photographs of Mireille were ownerless. He knew the drawer where Florence kept them. As soon as Norbury and Blythe were off he would take them out into his own keeping.

But how dilatory Blythe was! When he finally got into the car he still looked strangely disturbed, Inskipp thought.

"Got your passport?" asked Norbury.

Blythe shook his head. "I haven't the faintest idea where it is. Besides, it's Miss Rackstraw, not me, who's been killed."

Norbury said no more; he drove away quickly. Inskipp slipped up to Florence's room and opened a certain drawer—it had no lock on it; nothing at the farm had a lock on it—and found the precious pictures. Slipping them into his pocket, he went on to his own room and put them safely away.

As Inskipp locked the portraits into his suitcase until such time as he could get frames worthy of them, he saw Edna Blythe coming through the gate, looking her usual indifferent self.

Inskipp hailed her and asked if he might have a word with her. She seemed startled, but she was easily startled, as he had noticed.

"It's about Miss Rackstraw," he called when she was inside, and Edna's face lost its look of interest.

"There's been an accident," Inskipp said. "Blythe wanted to find you, but Norbury thought the police should be told at once. Miss Rackstraw..." He told her what Blythe had told him. Blythe had spoken of the friendship between the two young women, a friendship of which Inskipp had seen no trace, but to his surprise Edna Blythe now turned an ashen face to his.

"My brother was with her." she said in a curious, toneless voice and sank into a chair. "You're quite sure he didn't make a mistake? I mean, I suppose she really was dead—not just stunned?"

"He said that there was no question but that she was killed outright, that neck and spine were both broken by her fall. There are some nasty places in the gorges around here," Inskipp added. Then he stopped, for Edna's face looked as though she were on the point of fainting. He started towards her, but she waved him back and ran up the stairs to her own rooms. The Blythes had a wing to themselves. Inskipp took a few turns outside on the cement path. He could not understand Edna Blythe's way of taking the accident to Florence Rackstraw. It looked, it really looked, as though she suspected that Florence had met her death in some other way than as Blythe reported it to have happened. It seemed a preposterous notion, but turning it over now in his mind, he recollected an occasion, a week or so back, when he had come on the two of them in a chestnut wood evidently disagreeing about something. Richard Blythe had moved away just as Inskipp saw the two, and for a second, as she looked after him before she caught sight of Inskipp, the latter had fancied that he had seen the look of a trapped animal on Edna Blythe's face. He had told himself at the time that the shadows of the shifting branches were responsible for the fancy. He was not so sure now. It was a horrid thought. Inskipp was far more than good natured, he had a really kind heart, and that odd impression of the woods, added to the way in which Edna Blythe had just taken the death of Florence while out with her brother, disturbed him. Her brother... Elsie Cameron had never liked Blythe...

She and Mrs. Norbury were both still out. Edna Blythe and he were alone in the farm for the moment. He went to the foot of the stairs leading to her balcony, but when she ran down to him, it was from the stairs leading to his and the Rackstraws' rooms that she came, her suitcase in her hand.

"I went into Florence's room just for a moment," she said, answering his look. Her face flushed. "Florence asked me to see to something for her in Nice. And it must be done at once." She spoke hurriedly, her words tumbling over each other. As a rule Edna had a drawl. She actually bit her lip for a second as she faced him.

"I wonder—" she began. "Mr. Inskipp, I wonder—" her face was scarlet by now—"I wonder if you could let me have as much as—say—five hundred francs. I have hardly any French money."

As it happened, Inskipp had brought from Mention the last time that he was there the equivalent of fifty pounds in francs.

"It's just for the moment—my brother, of course, will repay it at once. I shan't get to Nice till too late for the banks," she murmured.

Inskipp assured her that he would get her the money. She thanked him tremulously.

"And please telephone for me to the Castellar Inn. I'm so upset I can't seem to remember my French. I want a car to take me down—at once!" Her teeth were actually chattering.

Inskipp telephoned immediately. He was told that Miss Blythe could have the Ford, but that there was no one to drive her.

"I'll drive myself. I don't mind. I'll be there at once. Tell him to be sure that there's plenty of petrol."

Inskipp could not offer to take her, for, not much of a driver at any time, he could not drive a Ford at all.

He handed her the notes and received a very grateful stammered word of thanks. Then unexpectedly she sat down at a table and began to write a short note. To her brother, she said. Meanwhile he picked up her suitcase and carried it out to the farm gates. She followed in a moment. She struck him as hardly conscious of where she was going, so long as she was making for Nice—or was that but a pretext to get away from the farm? He thought the latter, as the two now hurried on to the inn together. Some terror seemed to be urging her.

When the Ford was ready she jumped into the driving-seat, told the inn-keeper that she would not forget about the rule of the road in France, hurriedly shook hands with Inskipp, and said that she had written a line to her brother about the five hundred francs, which would he please hand him. She produced an envelope with Richard Blythe scribbled in pencil on it.

"I'll leave it in his room," Inskipp promised.

She had her finger on the starter, but she took it away. "Not on any account!" she said earnestly, and again with that look of fear in her eyes. "I could have done that! Please hand it to him yourself."

She waited for his "Certainly, since you prefer it." before she set the car in motion.

With her eyes fixed on the road ahead of her, Miss Blythe was out of sight in a few minutes.

She left Inskipp thoroughly uneasy. Back at the farm, he met Mrs. Norbury and Elsie, who heard the news with shocked horror. They, at any rate, did not look or act as though the fact that Richard Blythe had been alone with the dead girl had any terrible significance. On the contrary, Mrs. Norbury spoke of how great a shock it must have been for him.

As for Mrs. Rackstraw, she dreaded to think, she said, what a blow Florence's death would be to her. And unfortunately the brother, being at the Red Caves, might not, she supposed, be home till late that night. "I suppose Mr. Blythe told his sister before my husband hurried him off?" she asked.

Inskipp said that Miss Blythe knew of the tragedy, and had at once gone to Nice on some errand of Florence Rackstraw's. He said nothing of the extraordinary emotion which she had shown.

Three hours passed before Norbury and Blythe returned. As Mrs. Norbury thought, the dead body of Florence had been taken to the village mortuary. She and Elsie went at once to the place to find it being transformed into a sort of chapel by the kindly people, who have that respect for death characteristic of their race, who see in it a promotion, rather than a mark of bondage.

"Luckily we belong to what is known as Friends of the Police," Norbury said with a grin. "It was my wife's doing that we joined, when we first took the farm. It's a small enough subscription when one finds what red tape it saves one from. I told you you ought to take your passport with you, Blythe!"

"But that would have meant a delay to find it," Blythe pointed out. "You went with me—that was enough."

"It wouldn't have been if we hadn't been Amicales," Norbury told him. "You've no idea how many forms have to be filled in in a matter of this kind."

"Were the police troublesome?" Inskipp asked.

"At first they were inclined to be a bit stuffy," Norbury replied. "But when they heard about the baboon, they knew that Professor Voronoff had a 'Permis' to have another taken to his Château, and Blythe's account of it tallied. Very luckily, too, the man and it were rounded up at Mortola within half an hour. Fortunately the day is dry and the road showed the ape's prints as well as the marks of poor Miss Rackstraw's shoes where they slipped over the edge, so that there was no mistaking what had happened. But now, about Rackstraw at the Red Caves, how on earth are we to reach him? The police have learnt that he has already left the place, so there's nothing for it but to tell him when he gets here."

The Norburys were called away, and Inskipp promptly seized the opportunity to hand Blythe the letter from his sister.

Blythe read the few lines with a frown on his face. He was still frowning as he thanked the other for lending his sister the money. He did not look pleased, Inskipp saw, and the fact added to those doubts roused by Edna's manner.

The telephone rang. It was from Nice. From Miss Blythe, who was asking for her brother.

After a few minutes' listening to what she had to say at her end of the wire, Blythe told her that there would be no autopsy—that the police considered the tragedy to be quite simple and straightforward. He went on to say that he had her letter, and would settle with Inskipp whom he had just thanked for his most opportune help. That done, he hung up, and went to change and have a bath, for the ravine had left its marks on him.

Norbury came in then. His wife had to hurry away on some household matter, but he poured out a glass of whisky and soda for himself. "Talking is thirsty work—especially talking to the police. Then, too, Blythe—" He paused to make sure that the door was shut before adding. "His nerves were in tatters. He took that poor girl's death uncommonly hard."

Quite unconsciously Norbury's tone suggested his surprise at such a display of emotion on Blythe's part.

"I was afraid at one time that the police might think he was taking it too hard, and once the French Johnnies get that idea in their heads they can be very tiresome. Fortunately for Blythe, the place bore out his story in every detail. Personally I hardly know Miss Rackstraw. You and she were rather by way of being friends, weren't you?"

"Yes, she had some sterling virtues," said Inskipp warmly. He did not add that having Mireille de Pra as a friend was the chief among them.

Norbury and he now went up to Rackstraw's room, and tried to find the mother's address. But apparently Rackstraw had no note of it, and finally Inskipp went on to his own room.

He was rather surprised when, sometime later, Blythe slipped in and closed the door carefully behind himself. First of all, Blythe returned to him the five hundred francs lent to Edna, and then he added, with a very poor attempt at casualness—

"By the way, Inskipp, do you mind my asking you not to do it again? I mean, lend my sister money. I'm no end grateful as things happened, but even so, I ask you not to do it a second time."

Inskipp stared.

"The fact is," said Blythe awkwardly, "the fact is, that Edna is rather addicted to gambling. That's between ourselves strictly, of course. She's doing her best not to play again, but that's why she never goes down to Menton with the rest of you, and for her sake I cut it out too. So—well—should she ever ask you to let her have any money again, just have a word with me first, will you?"

He waited till Inskipp, very startled, said that Blythe could rely on him not to lend money again to Miss Blythe, then he hurried off as the telephone bell began to ring down below.

So Edna Blythe was a gambler—or had been one of those unfortunate people. But nothing told him by Blythe just now would explain the real fear in her face and voice when she learnt that her brother had been alone with the girl who had met her death—Inskipp went over in his mind every detail of his talk with Edna when she asked him for the loan of the money—though it did explain her and her brother's prolonged stay at the farm, and their refusal ever to go down into Menton.

Going to the big sitting-room used by all the guests as a lounge, he learnt that Edna Blythe had telephoned to say that she had already started back for the farm. So she was not spending the evening at any casino. Curious...Blythe must have been very urgent on the matter. Or had her own good sense triumphed?

His thoughts turned to Mireille. She must be told, of course, but it would be a dreadful shock to her. By this time, he and she wrote to each other as implicit lovers. He had finally made no secret of his hope that, once her divorce was secured, they could stand affianced before their world; and Mireille had written him a most touching little note that never left him, confessing that she asked nothing better of life than that this should happen, that his letters had completely won her heart.

Miss Blythe got back late that night, and seemed delighted to be once more at the Chèvre d'Or. In reply to Mrs. Norbury's questions as to what commission of Florence Rackstraw's had taken her so hurriedly to Nice, she only shook her head, and said that she was pledged to secrecy.

The next day, Rackstraw was still absent, very much to Norbury's vexation, for a note had come from the police requesting some one from the farm to go down to the British Consulate at Nice, and there explain just what had happened. The police had sent in their report, but, if the Consul thought fit, he might want an independent investigation made.

Norbury could not possibly leave, and Blythe had, he said, developed a throat overnight which prevented his using his voice.

Inskipp volunteered to go down and see the Consul at Nice, for he wanted to buy the most gorgeous frames that he could find there for the two portraits of Mireille. Mrs. Norbury thought that since her husband could not go, she ought to. So finally it ended in Mrs. Norbury, Elsie, and Inskipp going down together, while Edna Blythe insisted on her brother going to bed and letting her stir him up a linseed poultice.

Mrs. Norbury had begged her husband at breakfast to look again for Mrs. Rackstraw's address. But it was not until the car was almost at the gate that Norbury came down, waving a letter in his hand.

"Here's a note I found on Miss Rackstraw's mantel. In it is her mother's address in Bulawayo, or just outside it."

A cable was immediately telephoned. A long cable breaking the dreadful news.

At the British Consulate in Nice, they found that the French report had been so detailed that, after a few signed statements, the matter was at an end, as far as inquiries went. But the Consul wanted Florence Rackstraw's passport to be returned for cancellation.

"I think she had it with her," Mrs. Norbury explained. "We can't find it anywhere among her things, I feel sure it must have slipped out of her bag when she fell, and is lost somewhere among the undergrowth, but I'll look again for it when I get back to the farm."

On their return, Blythe's tonsilitis attack seemed to be very much better, so much so that he would be up and about on the next day, his sister thought.

"Funny, the way it's taken him," said Norbury to his wife when they were alone. "I believe that throat of his was merely to get out of going with you."

Mrs. Norbury looked incredulous for a moment, then she said thoughtfully. "That seems rather far-fetched. I mean, that Miss Blythe would lend herself to any acting. But the Blythes are rather funny—don't you think so, Frank?"

He had picked up a pile of French notes from the dressing-table. "These are from the Blythes? Wonder why he never pays with a cheque? Is that what you mean by funny?"

"I was thinking of the fact that neither of them ever get any letters." His wife spoke under her breath.

"They go down to Menton for them, so he says, and get them from Cook's, or from Barclay's bank."

"There are never any envelopes thrown away in their paper basket by either of them. Even Sabé has spoken of it."

"They are our salvation this bad year," was Norbury's only answer.

"All her underwear and all her clothes were bought at Menton," went on Mrs. Norbury. "The last place where one would buy an outfit, if one could help oneself, with Nice so close to us." She stopped, for Norbury's face showed clearly that he did not want to hear any gossip about the Blythes, the most profitable guests at the farm.

RACKSTRAW arrived early next morning. He had been up in the hills, and so had missed the messages to him that the police had sent out.

In a couple of days it was, Inskipp thought, as though the sea had closed over the ugly, lanky figure of Florence Rackstraw, or as though she had never been, so little difference did her death seem to make in the life at the farm. He had to wait some time for a letter from Mireille; she wrote in great grief at the loss of her friend and then went on to tell him that she had been hurt in a car accident and that her arm had had to be set in plaster, though her fingers were free. She had no portrait to send him, she wrote, but would have one taken as soon as her arm was free again, and would send him a copy. The note was brief, as holding a pen under such circumstances was very difficult. She wrote that she hoped he could read her altered writing. But her next letter was typewritten. Mireille said that she had bought a typewriter, as the doctor told her that a compound fracture of the upper arm—which, it seemed, was what she had had—was often long in healing. Mireille wrote that she had told them to take all the time that was necessary, rather than let her arm be shortened, or stiffened. They had assured her that that could not happen, if she was patient. And again she spoke of what a loss the death of Florence was to her.

Inskipp was beside himself at the thought of her suffering, though she wrote that she was being wonderfully nursed by the nuns. As for her coming to the farm, she agreed that she could still come, but not for some time as the slightest jar might injure her arm beyond repair.

Inskipp forced himself to be content with her letters, and they were enchanting. Gay—sweet and humorous by turns. But he found it hard to wait. He thought of coming to Brittany himself, but when he suggested this to Mireille, she wrote very definitely against it. Gossip would at once learn of his presence and of their friendship—and their hopes. And the knowledge would be used by the de Pra family to put yet another obstacle in the path of the divorce, which they were contesting so obstinately.

Autumn turned to winter, Christmas came and went, a gay festival, with circular loaves carried like wreaths hanging on the arm to be blessed at midnight mass on Christmas Eve, with saucers of growing wheat set at the corners of the tables, which had been set to soak on the festival of St. Barbara and which were now hand-high little tufts of green tied about with scarlet ribbon. Rackstraw and Inskipp were deep in their work which was practically finished. Rackstraw was going home shortly to find a producer, but as yet he had made no move. The Blythes spoke of leaving about the same time, but they too lingered. As for the Norburys, they seemed to have turned the corner at last, and showed cheerful faces as they went about the place. So had Inskipp up to these last days, but now, every twenty-four hours marked an added gloom. Rackstraw happened to come on him pacing his room one afternoon.

"I wonder if you could let me have—" he began. Inskipp made a gesture of negation which for him, was quite violent.

"I shall be able to pay back every farthing when I get home, apart from my share of the film," began Rackstraw huffily, but again Inskipp did not let him finish.

"I'm afraid I must ask you to do it before you leave. I'm sorry, but are you aware, Rackstraw, that you've borrowed close on fifty pounds from first to last?"

"Have I really? Well as soon as I get home you shall have it back—and interest too, if you like."

"I'm in a hole myself," said Inskipp, "or I shouldn't have to hound you for the money. I invested pretty nearly everything I own in Waverly Shipping bonds. They've become unsaleable, since Lord Waverly committed suicide last week."

"Did you put everything into one basket? My dear chap, how foolish! You should never do that, you know. Spread your risks. That's the point in—"

"The point is, that I want that money returned to me before you leave here," said Inskipp firmly. "I'm sorry, but I must have it."

"Well, I'll see what I can do," promised Rackstraw graciously, as though he were helping the other out with a loan. "I'll see what I can do."

Inskipp with a nod, let the matter rest there for the moment. He was indeed hard pressed, and his face grew careworn as he stood turning over what he had best do. Some sort of reconstruction scheme would certainly be put forward by the Receiver, and in his opinion the shares had not been overvalued at the price at which he had bought them. Given time, he believed that a good deal, if not all, of his money might yet be saved. But what was he to do in the meantime? There was no help for it, he must call in every outstanding farthing belonging to him, and return to England.

The trouble was that in the middle of November, Mireille had written asking him for a loan to help her get her divorce. She had explained that under the will of a French aunt, she would inherit the equivalent of around three thousand pounds, but only when de Pra was dead, or divorced by her. The aunt in question had so much disliked the marriage. She had sent Inskipp a copy of her aunt's will, and the name of her solicitor who lived at Clermont Ferrand, and added that she would need about seven hundred pounds at least, that the solicitor in question had offered to lend her the money, but at such extortionate interest that she was very unwilling to accept his offer.

Inskipp had written to the man, and had had a letter from him. Inskipp had wanted to know whether there was any doubt about the divorce being ultimately obtainable. The reply had been entirely reassuring. The avocat had explained, however, that it might cost nearer a thousand than seven hundred pounds, as very expert medical opinions on the question of Mr. de Pra's sanity and impossibility of his condition improving would have to be obtained. He had lived a long time in Indo-China, this would mean extra expense. Maître François added that he could easily raise the sum, but that the client who was prepared to advance it insisted on the high interest to which Madame de Pra objected.

Inskipp thought of going to Clermont-Ferrand, but the journey from Menton was difficult and long, with many changes. Nor would he, a stranger, be able to rely on his judgment of the character of this Maître François. He must get some information about him from a reliable source. And then he remembered that at the Menton branch of the English Bank, the manager had once spoken of knowing Auvergne well. Clermont-Ferrand is the capital of Auvergne.

He went down to Menton, and cashed a note at the bank in question, waiting about until he caught sight of the manager. Then he stepped forward.

Could the manager spare him a few minutes in private? A most obliging man promptly took him into his own room and offered him a chair.

Inskipp explained that he had been given the name of a Maître François, as that of a good avocat of Clermont-Ferrand. Could the manager tell him what was his reputation.

The manager promptly told Inskipp that his affairs could be in no better hands, especially if they belonged to what he might call the family type. "I don't know him personally, but every one in Auvergne knows his name. He rather specialises in divorce cases, but by no means entirely. I hear he is being very much pressed to go into politics. You will be lucky if he takes on any new business."

"Is he well-to-do? Frankly, it's a question of a lady placing rather a large sum of money in his hands to be applied to—er—legal work."

"My dear sir, a Frenchman doesn't think of entering politics if he is not well-to-do! Maître François is considered a rich man, and comes of a very wealthy Clermont-Ferrand family. He belongs to what they call the noblesse de robe."

Inskipp thanked the manager and left. The next post carried a letter to Mireille saying that he could let her have the money without, of course, any interest. Should he send his cheque to her, or to Maître François He had made it out, he wrote, for a thousand pounds, the surplus to be retained temporarily by the solicitor for unexpected emergencies.

She had written him a most grateful note, asking him to send the money to Maître François who would draw up the proper papers for it to rank as a first charge on her legacy from her aunt. She did not want it sent by cheque, however, as it would so remain entered on his books. Under the circumstances, she thought the money had best be sent in 1,000-franc notes.

Inskipp thought it over, and decided that her caution was justified.

The pound was exactly a hundred francs at the moment, so that a very small packet of the thin, beautiful, French notes made up the equivalent of the sum wanted. Inskipp obtained them at the bank in Menton against his cheque, and, for additional safety in the post, had the manager make a note of their numbers.

Maître François duly acknowledged the notes, enclosed some papers for Inskipp to sign, and said that the figure set was an outside estimate which he hoped not to have to reach.

Mireille wrote to Inskipp scolding him tenderly for his generosity. She herself was living very cheaply at the convent, and would be at still less expense in the future, as the time had now come for her yearly round of inescapable family visits to begin. Inskipp was to continue to send all his letters as, at her request, he had done the last ones to her, care of Maître François. Otherwise, Mireille wrote, she and he could not correspond at all. The idea of her receiving a letter in an unknown handwriting—a man's too—without reading it aloud, was unthinkable to her family circle. As for her arm—it was healing very well, but she still could not hold anything small, such as a needle, or even a pen, in her fingers without her hand aching badly. Her relations always went to one or other of the many French spas and were already discussing which would be best for her arm. No, she could not get away to La Chèvre d'Or yet. But once her three months' duty round was over, she could come—and come without rousing comment, and be there for the spring parade of Provence.

When the blow of his almost unsaleable shares fell on him, Inskipp thought it over, thinking for two people, himself and his future wife, Mireille for they were by now definitely engaged—and it seemed to him that there was but one thing to do. Mireille must borrow from her solicitor the equivalent of the thousand pounds which he had lent her and he—Inskipp—would take back his own loan and pay the ten per cent interest asked by the solicitor's client. It could not be much longer now before the divorce went through—another three months at most, thought the Clermont man, and then the money could be repaid from the legacy coming to Mireille. As for himself, Inskipp believed that if he went and had a personal interview, his own old Stock Exchange firm, who happened to have just lost a partner, might let him come in again with his depreciated shares as his investment and, since he was returning to the House, he could arrange to be let off the purchase price of his seat, or at any rate have it lessened to a sum which he could raise. Meanwhile, with the return of the thousand by Mireille he could live, and as his income from the firm he intended to join would, after the first year, be quite adequate, he and Mireille could start life together in comfort if not in luxury. But he must first, for both their sakes, get back his loan—and he wrote a very businesslike note to Mireille, setting it all out clearly.

He had, in return, one of the most enchanting letters which he had yet had. Inskipp read it with tears in his eyes. His heart was very tender towards the lovely creature who had come into his life, "lovely within as without," he murmured, as he put the letter away. For the rest, he was glad that he had the photographs of her that she had given to Florence Rackstraw, for there were no photographers near the convent, and, though Mireille wrote every now and then that she would have her portrait taken, she had very little time for long outings. He had let her guess almost at once by some phrase of hers that he had, or had seen, her portrait, and she more than once wrote as though that should content him until they should meet. Inskipp with some misgivings, had finally sent her one of his that he had taken for the purpose in Menton, and she had said that he looked just as she had thought that he would look. A sentence which made him laugh a little wryly, and put aside in his memory as something with which to tease her, when they really should talk together...When he should hear her voice... Florence said that she had the most beautiful voice that she had ever heard, and Inskipp loved a sweet voice.

The reply from the solicitor at Clermont, as Inskipp called the town to himself, was slow in coming. Maître François pointed out that it might take him some time to find any one willing to lend the necessary amount needed by Madame de Pra, as the client who had proposed it before had been drowned in one of the recent floods which had turned the surrounding plains into lakes. He did not despair, he said, of ultimately finding a lender, but, just at the moment money was very tight. That he did not think the loan an impossibility, was the great thing, Inskipp decided, for François had struck him from his letters as a man who would be ultra cautious in money matters. He probably was equally cautious in his promises. But there would be no more loans to Rackstraw. Both he and Inskipp believed that they ought to sell the scenario for a good figure. Rackstraw, who had quite a fair knowledge of such things, talked of an out and out sale for four thousand pounds. Still, there must be no more loans...

Having given Rackstraw his ultimatum as it were, Inskipp went for a slow walk and on his return he looked around for Norbury. He might as well know that his—Inskipp's—stay was drawing to a close. He came on him sitting in the hot sunlight against an old wall entering the weights of basket of oranges as they were called after him.

Inskipp told him that he must shortly go home. At the moment he could not give the exact date.

"Any complaints?" Norbury asked.