RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

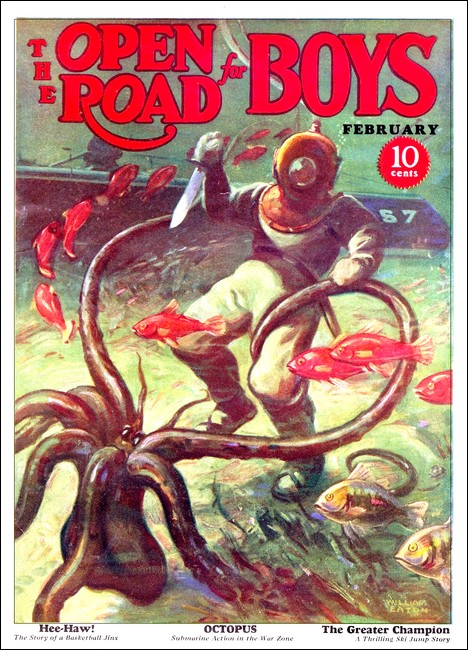

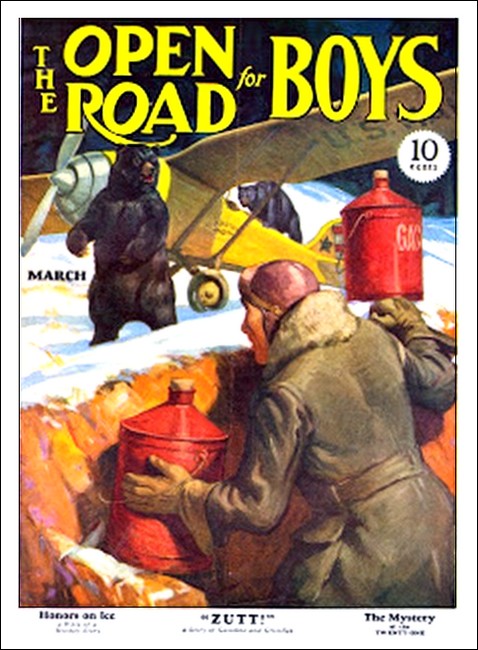

The Open Road for Boys, October 1931, with

first part of "The Incas' Treasure House"

THEY were lost! For some time both boys had felt sure of it, and could no longer conceal their helplessness, or their realization of the dangers they faced. They gazed at each other wide-eyed, without speaking, for each dreaded to voice his fears.

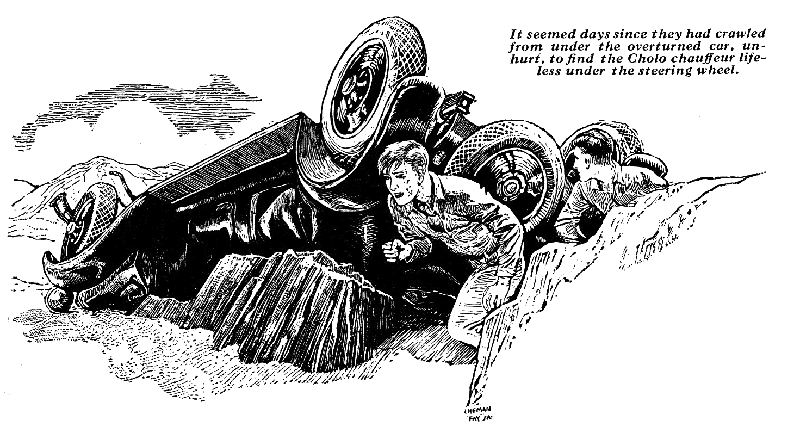

It seemed days since they had crawled from under the overturned car, unhurt, to find the Cholo chauffeur crumpled lifeless under the steering wheel; yet Pancho's watch told them it had been only eight hours since they had been laughing and chatting in the car as it bumped across the desert toward La Raya mining camp where the boys had planned to pass their vacation with Bob Stillwell's father, the manager.

For months they had looked forward to the trip, ever since Bob had received a letter from his father telling of the wonders of Peru and suggesting that he bring a friend with him. Of course Bob had chosen Pancho McLean, his most intimate chum, who, having lived for several years in Mexico, spoke Spanish fluently. Bob's father had sent word that he could not meet the boys as he had planned, but one of the officials of the La Raya Company had greeted them aboard ship at Callao, and had seen them safely started on their way to the mines in one of the company's cars. The accident happened suddenly, unexpectedly. One instant they were speeding across seemingly trackless desert, the next instant the car had skidded, crashed into one of the countless outcrops of jagged rock that dotted the waste, and overturned. Shaken and terrified, Bob and Pancho cut through the wrecked top. With trembling hands they tried to drag the chauffeur free, but after one horrified glance at the fellow's battered face and crushed head they hastily retreated.

"Let's take food and the water bottles and get going," said Bob. "That poor chap is beyond help, and there's no use staying here."

"How about the guns?" asked Pancho, as they prepared to burrow beneath the car in search of food and the thermos bottles.

"What's the use," said Bob. "There's nothing to shoot in this desert, and we'll have to get someone to bring in the rest of the stuff. We can get the guns then. I'm not going to lug a gun across this desert. It'll be bad enough hiking as it is."

"I don't know," muttered Pancho. "I'll feel safer with my rifle."

"All right, take it if you want to," said Bob, "but mine stays right here."

It was not a pleasant job, salvaging the precious water bottles, the lunches provided for their journey, and the few other necessities while the dead man lay so close beside them; and it was a still more unpleasant duty to cover the body with the cushions and ripped top in order to protect it from the black vultures which already were gathering. At last it was done and the boys breathed sighs of relief.

"Now which way do we go?" asked Pancho, glancing at the glaring desert and distant mountains.

"Follow the road, of course," replied Bob.

"Yes, if there were a road to follow, but I don't see any."

The boys gazed about in bewilderment. Beyond the spot where the car had skidded, there was no sign of road, nothing to distinguish one part of the rock-strewn waste from another.

"I never noticed we weren't following a road," muttered Bob. "There was one back a ways. I wonder how far." Suddenly Pancho laughed. "We are boobs!" he exclaimed. "Even if there's no road, we can follow the wheel marks back the way we came."

"Yes and walk fifty miles before we get anywhere," said Bob. "We passed the last village a little after eight and it's now eleven.'"

"The Cholo said we'd be at a place called Palitos in time for lunch," Pancho declared. "So it can't be more than twenty-five miles away, but it might as well be a hundred if we don't know the road. I wonder how long we'd have to wait here before someone comes along?"

"We'd die of thirst," declared Bob. "This isn't the regular route to La Raya, you know. They generally go down to the coast and take a steamer at Lobos. Dad had us come this way because there won't be a ship for ten days. What's twenty-five miles? All we've got to do is to head for the hills, if Palitos is there."

"Fine!" Pancho exclaimed sarcastically. "There are thousands of hills. Count 'em."

"Well, the car was heading northeast so we can hike that way," declared Bob "Come on, feller, move your feet."

THE walking was not hard, and though the sun beat down mercilessly and the desert quivered with heat, the boys trudged doggedly on. But they had not learned that mirages in the Peruvian deserts can play tricks, that the hill they had selected as a guide to their objective did not exist—at least in that spot—but was really ten miles further than it appeared. Tired and hot they threw themselves down to rest at the foot of a billowy sand dune. They ate greedily, and washed the dry food down their parched throats with copious draughts from the thermos bottles.

"I guess we must be pretty near there," remarked Bob when, refreshed and with appetite satisfied, he rose and looked about. "I hate to think of climbing over these dunes."

"No reason why we should," said Pancho. "The car couldn't have done it so there must be a way around them."

They soon found that there were a dozen ways around——or rather between the sand hills. Moreover, they were criss-crossed with innumerable narrow trails.

"That looks like an old river bed to me," observed Pancho, as they pushed wearily onward. "I don't see how a car could ever get up here."

"Oh those Fords can go anywhere," grunted Bob. "Anyhow, this is a sort of pass and the trail still leads up it, so there must be someone in here."

Presently the trail swung around a jutting shoulder of the mountains, leaving the stony area behind, and zig-zagged up the steep slope.

The boys halted undecided. Should they follow the wash or keep to the trail? Finally, deciding that the trail was probably a short cut, and that from a height they could obtain a view of their surroundings, they turned up the narrow pathway. Up and up they climbed, until at last they came to a wide stretch of hard rocky puna, or upland desert.

"It doesn't look as if anyone ever lived here!" cried Bob. "Whew! I hope we don't have to go all the way back."

"I don't know," said Pancho, who was studying the surroundings carefully. "It looks as if there were a valley over between the hills to the left, and there's some green among the rocks. That means water and most likely the village is in the valley. Let's go on and see."

"There's green all right," declared Bob, a few minutes later. "Perhaps you're right, Gee Whittaker! I'd like to lie down and rest!"

"There's a house!" Pancho shouted suddenly.

Elated at thought of finding a village, they rushed forward. Clinging to the hillside was green vegetation, and, at the edge of the stunted growth, a hut; but the boys' faces fell as they reached it. The rude shelter of sticks and dry wild cane was empty; it had been deserted for months, as even their inexperienced eyes told them. And the vegetation consisted of only a scanty growth of wild cane, of giant prickly-pears and scraggly, dwarfed algorobo trees that clustered about a tiny fissure in the rocks where a trickle of moisture showed. Worst of all, there was no valley—only a dark, yawning canyon surrounded by forbidding cliffs.

UTTERLY spent, Bob and Pancho flung their tired bodies to the ground in the shadow of the abandoned hut. The sun was already dipping toward the west and the mountains cast long purple shadows across the rocky puna. Their tramp had been for nothing and night was fast approaching. Still the two did not realize the predicament they were in. They were confident that had they kept on up the pass, instead of striding off on the trail, they would by now have been in the village they sought.

"My feet are two big blisters," Bob groaned. "But, if we've got to go we might as well be on our way," he sighed resignedly. "I'd be too stiff to move if I stayed here much longer." For several minutes they tramped with heavy feet across the puna, then came to an abrupt halt. The trail led up, not down, the hillside. Silently the two boys, now inwardly fearing the worst, turned in the opposite direction only to find that the trail described a wide loop and again led up hill. "How are we going to get out of here?" Bob looked around helplessly. "Why didn't we notice some landmark?"

"Because we felt too cocksure there were people here," replied Pancho.

Suddenly he laughed. "There are your people!" he exclaimed.

"They're goats, and these paths are only goat trails!"

Pancho dropped to one knee and cocked his rifle. "Going to have fresh meat for dinner," he declared. The goats had approached within easy gun shot. A half-grown kid dropped in its tracks and the others scampered off.

There was plenty of fuel in the little thicket, a fire was soon blazing, and a hearty meal of broiled kid worked wonders in restoring the boys' spirits. To be sure, the sip of water they permitted themselves seemed only to increase their thirst, but they were too tired and sleepy to worry over it much. Stretching themselves on the warm sand, they were soon sleeping soundly.

SUNLIGHT streaming on their faces awakened them. "I've been thinking," observed Pancho, as they ate breakfast, "that the best plan is to climb one of these hills before it gets too hot. Then perhaps we can spot a valley where there's water or a village or something."

"All right," assented Bob, "but I hate to think of climbing up there and then being no better off."

"We can't be any worse off," Pancho reminded him. "We've either got to find a village or a stream or we'll be up against it, Bob. There's no use kidding ourselves. As it is we're lost and we haven't a decent drink of water left."

It was a terrible climb up the steep slope. Loose rocks rolled beneath their feet, the razor-edged outcrops cut their hands and shoes, and their thirst became an almost unbearable torture. At last they reached the summit and gazed about. Far below them was the little hidden desert surrounded by its rim of rocky ridges. Beyond the western hills lay the hazy expanse of the big desert, a shimmering sea of sand.

Their eyes swung hopefully, expectantly around the horizon, and they shouted triumphantly. Almost at their feet a deep valley lay between the hills, and in the bottom of the cleft was rich green vegetation and a sparkle of running water!

Promptly they drained the last of the precious fluid in their thermos bottles. No need to save those few drops now. Then, stopping only long enough to pick out a descent that seemed passable, they hurried downward towards the valley.

How they managed to reach the bottom without breaking their necks neither boy ever knew. They got there somehow, and threw themselves down beside the little stream.

"I never knew water could taste so good," exclaimed Bob, when at last he raised his dripping face. "I'm going to stay right here till we're rescued."

"I'm not," declared Pancho. "But just the same that water's the best thing I ever tasted."

Refreshed, and having bathed their dust-covered bodies and blistered feet in the cool water, they discussed their next move.

"I'll bet there are people not far away," declared Bob. "This is the only place we could see from the hill that had water."

"We'd better keep on up this valley," declared Pancho. "I'm for sticking to the water as long as we can. We won't die of thirst, and there should be game in these thickets."

As they walked up the valley, Pancho held his rifle ready. He had begun to fear that they would either have to go hungry or depend upon small birds for their lunch, when he saw something moving among the rocks and called his companion's attention to it.

"Looks like a rabbit to me," said Bob.

"Or a woodchuck," added Pancho. "Anyway, it may be good to eat, whatever it is."

The creature was now standing erect on its haunches watching the boys in the ravine below. It was an easy shot, and at the report of the rifle the beast tumbled and slid down the hillside.

"Maybe it's a chinchilla," suggested Pancho, as they examined their kill. "They live in Peru and their fur is valuable. We'd better save the skin, Bob."

"Do you suppose it's good to eat?" asked Bob.

"Guess it depends on how hungry we are," replied Pancho. "We'd better wait a while; it's not lunch time yet."

AS they continued up the valley they shot two more of the viscachas, as the gopher-like animals are called in Peru, and at Bob's suggestion that it would be easier to carry them in their stomachs than in their hands, they found a shady spot, built a fire and proceeded to broil their game. With their appetites whetted by their tramp, the tender white meat tasted most delicious even without salt or seasoning.

They were just finishing when, with a whirring of wings a large, brownish bird sprang from the ground almost at their feet and dropped into a tangle of vines across the little valley.

"Partridge!" exclaimed Pancho.

"Well, he'll be good for dinner," declared Bob. "Let's see if we can get him."

Cautiously the boys crept forward, but the vines and weeds were so thick that they couldn't detect the mountain partridge, or perdis. Not until they were within a few feet of it did it take flight with a roar that startled them. With only a rifle and a limited supply of ammunition their only hope was to get a fair shot at it when it alighted, but the bird, whose plumage blended perfectly with the sand and rocks, appeared to vanish as it dropped to the hillside.

Oblivious of all else, the boys crept, crawled and stalked the elusive perdiz, until at last Pancho brought it down with a lucky shot.

"Here 'tis!" cried Bob, dashing forward and holding it up in triumph. "Now we'll have a good dinner."

"And here's the end of the valley," exclaimed Pancho. "And not a sign of a house or a human being."

It was true. The valley narrowed into a mere rift in the mountains with almost perpendicular walls.

"How are we going to get out of here?" queried Bob.

For some time they examined the rocks, searching for a way up, but in vain. Then Bob discovered some ancient, crumbling masonry, and the two examined it with intense interest.

"It looks like a regular flight of steps leading out of here," declared Bob.

"No—I don't think so," said Pancho. "It curves the wrong way. Say! I know what it is—look, you can see it sticking to the rocks up there—it's part of an old bridge or viaduct that has fallen to pieces. There must have been a road up there, crossing this ravine."

"Maybe it's the old Inca road that Mr. Griswold told about!" cried Bob. "If so, we can follow it to some place. And I'll bet we can climb up here."

Carefully, for a slip meant a nasty fall and possibly broken bones, the two began clambering up the steep side of the little canyon, aided by the bits of masonry still adhering to the cliff. It was a hard climb, but at last it was accomplished and they stood safely on the summit above the canyon. Then, for the first time, they remembered about water and food.

"Whew!" ejaculated Bob. "We forgot to get water and the bottles are empty!"

"We are a couple of boobs," declared Pancho. "Well, we've simply got to climb down again."

"We might explore around a bit before trying to go down," said Bob hopefully. "Say, look here! We're on a road!"

UNQUESTIONABLY, a shelf of rock on the mountain side had been cut by hand. It was too even and level for a natural formation, and the remains of a stone pavement were visible amid the rocks and sand that had slid down the mountain through long centuries.

"It's a road all right," agreed Pancho. "Maybe the old Inca road. See, there's more of it across the canyon. It must have crossed over by a bridge once. I wonder where it leads."

"That's what we'll find out," said Bob positively. "We'll just hike along till we get somewhere."

Luck this time was with them. A few hundred yards beyond the ravine a stream trickled down the mountain, and the two drank all they could hold and filled the bottles. Then they walked steadily on, gradually ascending, until by the time they began to think of preparing to pass another night in the open they were thousands of feet above the desert where their car had been wrecked. On every side was a wilderness of peaks, ridges and purple canyons. In the distance, snow clad peaks gleamed against the sky.

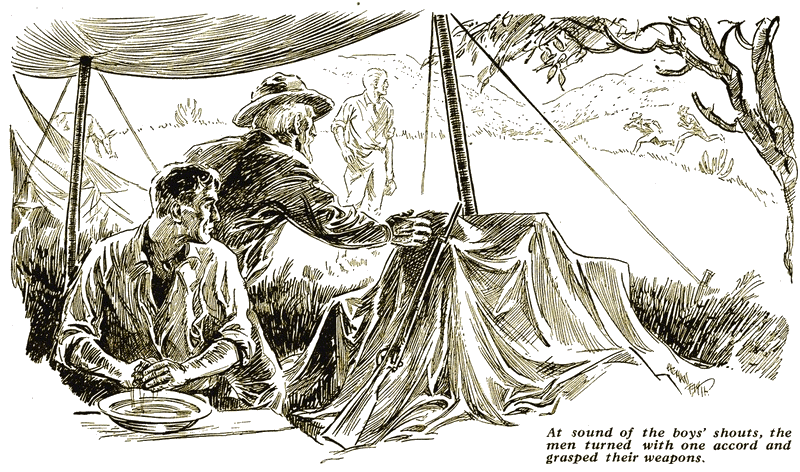

"We're on top of the world!" cried Bob as they gazed about. The boys decided to spend the night where they were, and as they searched for dry agave stalks and twigs for fuel they discovered the half ruined walls of a stone building.

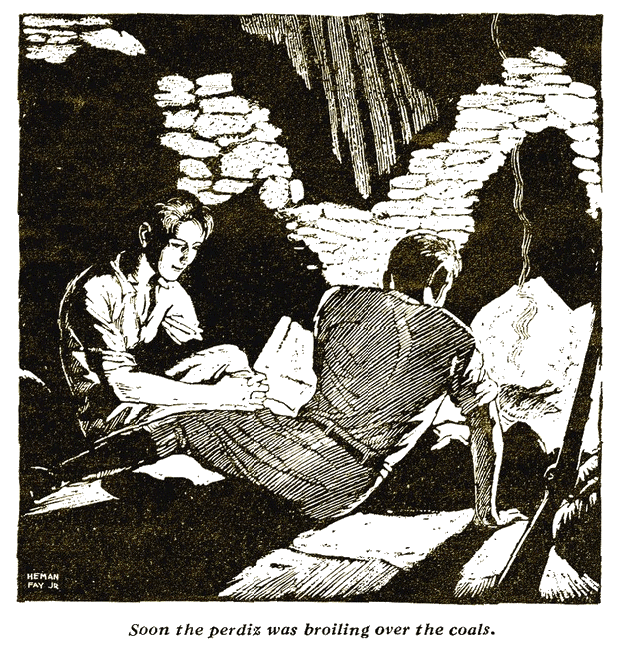

"Someone lived here once," declared Pancho. "Let's clean it out and camp inside; it's a lot better than staying out in the open." Very soon a fire was blazing in the ruins, and the perdiz was broiling over a bed of coals. Outside, the chill mountain wind whistled, but the boys were comfortable and warm. They laughed and chatted as they picked the bones of the big partridge, apparently as light-hearted and free from worry as if they had been on a week-end camping trip instead of lost among the Andes.

The fact that they had come upon the old road, that they were enjoying the shelter of what had once been a building, convinced both that they would soon reach a settlement. That the road had not been in use since the mail-clad soldiers of Pizarro traversed it more than four centuries before, that the stone walls that sheltered them from the biting wind were the remains of an Incan tambo or rest-house and had not been occupied since the days of Atahualpa, never occurred to them. Unaware of these facts, never dreaming that every mile they traveled along the ancient highway was taking them farther from La Raya, Palitos and all other outposts of civilization, the boys slept soundly, to awaken shivering in the chill morning air and with ravenous appetites.

"I wish we'd saved some of that bird for breakfast!" lamented Bob, as he crouched over the smouldering ashes of the fire.

"You're always wishing," Pancho reminded him. "I could wish a lot better than that. I could wish we had a heaping dish of hot buckwheat cakes and maple syrup and fried sausages or—"

"Oh, shut up!" cried Bob. "I wish we had some of that coca that the Indians chew to keep from being hungry."

"No use wishing for anything," said Pancho philosophically. "Come on, let's be on our way. Maybe we'll find something to shoot, even if it's only a buzzard!"

HALF an hour after leaving the ruined tambo they came in sight of a gravelly slope, and instantly dodged back. Less than a hundred yards distant they had seen several animals grazing.

"Deer!" whispered Pancho, cocking his rifle and cautiously wriggling forward.

As his shot rang out he sprang to his feet. "Got him!" he cried. "Golly, Bob! Look at those fellows go!"

"Whee! I've never seen anything step on it so fast!" exclaimed Bob, as the frightened creatures vanished in the distance.

"Well, we got one and now we can have breakfast," Pancho reminded him.

"It's not a deer," Bob said as they approached the dead animal.

"Looks more like llama," said Pancho.

"I know what it is! We saw one in the zoo at Lima. It's a vicuña!"

"Guess you're right. Anyhow, I suppose he's edible so let's find a place where we can build a fire and eat."

"We can't cook him whole," Bob observed. "We've got to skin him and dress him and wait till he's cold, you know."

"Seems to me it would be a lot easier and quicker to cut off his legs and leave the rest," declared Pancho. "We couldn't carry the whole thing along with us anyway."

Even to cut off the vicuña's hind quarters with only their pocket knives was no easy job, and the boys were tired, bloody and heartily sick of their amateur butchering before it was finally accomplished. Each carrying a haunch of the vicuña, they left the carcass to the buzzards and made their way to a little stream where they washed the blood from their hands and the meat. Soon two steaks were sizzling over a fire. Blackened, smoky, half-cooked as it was, the meat tasted delicious. As they were eating, they made a surprising discovery. They had built their fire against a big grayish-green object that Bob had thought was a moss-covered rock. Now as he gnawed at a slice of the meat and glanced at the dying fire, his jaws stopped working and he stared incredulously. The supposed rock was burning!

"Look! Look there!" he cried, seizing his companion's arm. "That rock's on fire!"

Pancho exclaimed in amazement. He picked up a heavy stone and threw it at the glowing mass. A shower of sparks flew up, there was a dull thud, and a piece of the burning object broke off.

"It's not a stone," he declared. "It's some sort of wood. Say, Bob, we're in luck! I've seen lots like it and now we know they'll burn, we won't have any more trouble over fuel."

"Say, that's a lucky break," declared Bob. "Let's build a big fire and roast this meat now. Then it won't spoil and we can eat it any time."

At once the boys began to gather a great pile of the strange woody masses, which were really yaretta plants, the customary fuel of the denizens of the higher Andes. Then, after roasting the vicuña, they started along the road. Back and forth around the mountain sides, along narrow ridges, zigzagging up the precipitous slopes, winding along the edges of mile-deep canyons, the ancient road led, until the boys were hopelessly confused. Seemingly near at hand, an immense snowcapped peak thrust its dazzling summit far above the surrounding mountains.

"I'll bet we're not far from La Raya," declared Bob. "Dad said the camp was on a mountain within sight of a glacier, and that's the only mountain with a glacier we've seen. My guess is that the mine's right on the other side of it, so all we have to do is to walk half-way around it."

"Sounds easy," Pancho replied, "but there may be canyons and all sorts of obstacles in the way. Anyhow, it's miles to that mountain, and a lot more miles around it. "

"You don't seem very worried over it," commented Bob, "and somehow I can't get terribly scared myself. But I am troubled about Dad. He must be worrying, and wondering what's happened."

"We were fools to have left the car," said Pancho. "If we'd only stayed there they'd have found us. It's too late now. Come on, the sooner we get started the sooner we'll get somewhere."

PRESENTLY, they realized that they were no longer climbing upward. Glancing back, Bob saw that they had already descended several hundred feet.

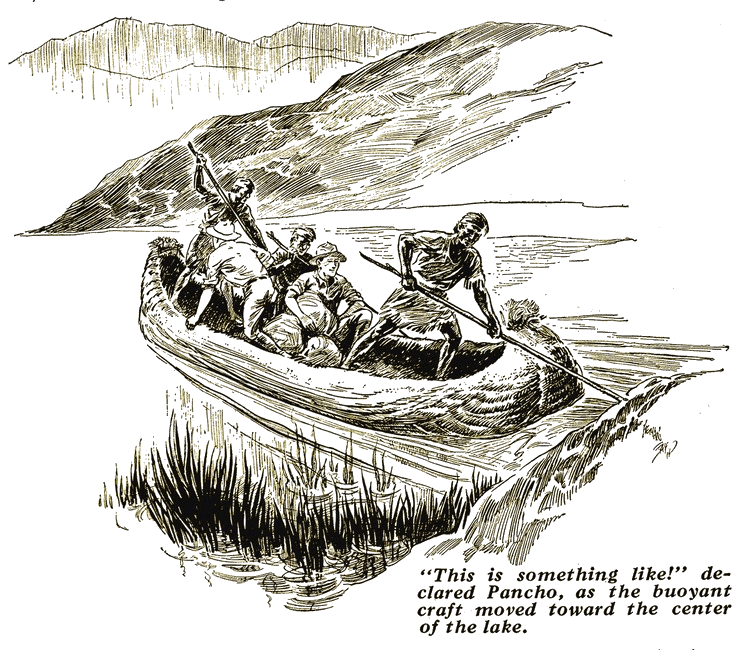

"We're going down hill!" he cried, "Probably this old road leads into some valley where there are people."

"We're going down, all right," agreed Pancho, "but likely as not we'll be climbing again in ten minutes. The fellows that built this road just went wherever they felt like it. You're right, though, Bob! There's a valley down there and green stuff!" Far below them opened a deep valley richly green.

Feeling sure they were nearing inhabited country, the boys hurried forward. Sliding and slipping, barking knees and shins, yelping with pain as they bumped into clumps of cacti, they at last reached the bottom of the slope in a cloud of dust and a small avalanche of dislodged gravel and stones.

"Well here we are, but where are we?" remarked Pancho.

"How should I know?" grinned Bob. "There are trees down farther, and water. Let's have a bath and wash some of this mountain off of us."

Refreshed by their bath in the cold water, they started down the valley.

"There's one thing sure," announced Pancho presently. "If we can follow this stream it's bound to lead to a river, and as people nearly always live near rivers we're certain to find someone in time. And if there's any game anywhere it will be where there are water and trees.

"The vicuña wasn't," Bob reminded him.

"No, but we might hunt for a month and not see any more of them," declared Pancho. "I'll—Gosh, Bob! What was that!"

They halted in their tracks, listening intently. From somewhere ahead sounded a piercing scream followed by snarling growls, groans and the crashing of brush!

The Open Road for Boys, November 1931, with

second part of "The Incas' Treasure House"

A. Hyatt Verrill in Indian costume.

WE want you to meet Mr. A. Hyatt Verrill, author of The Incas' Treasure House. Here he is dressed in his Indian costume, as Chief Cuviboranandi of the Guaymi Indians, a wild Panama tribe. When you are reading this story, you may feel sure that the author "knows his stuff," for he is an explorer of wide renown. He has penetrated distant Central and South American jungles, climbed perilous mountain peaks, mingled with wild Indian tribes and won their confidence, to the extent of being adopted into a tribe. He is the only white man who has seen the fabulously rich gold mine of Tisingal, in Costa Rica, and lived to tell of it, since the Indians killed the Spanish miners long ago, and swore death to any white man who should ever seek to lay eyes on the treasure again. And it was all because he cured the chief's young daughter of an illness that this honor was bestowed on him. His own experiences are as interesting as any story that he could write, and that's saying a good deal.

BOB STILLWELL and Pancho McLean, who has lived in Mexico and speaks Spanish, are on their way to La Raya mining camp in Peru, where Bob's father is manager and where they are to spend their summer vacation. On the last lap of their journey they are met by one of the company's cars and are speeding over barren wastes toward their distant goal when the car overturns killing the native chauffeur. Bob and Pancho hike off in what they think is the direction of La Raya, but they soon become hopelessly lost and, following an ancient abandoned road, wander farther and farther into the fastness of the Andes. They manage to find water and kill enough game for their needs. As this installment opens they have just been started by a piercing scream, followed by groans and crashing of brush near at hand.

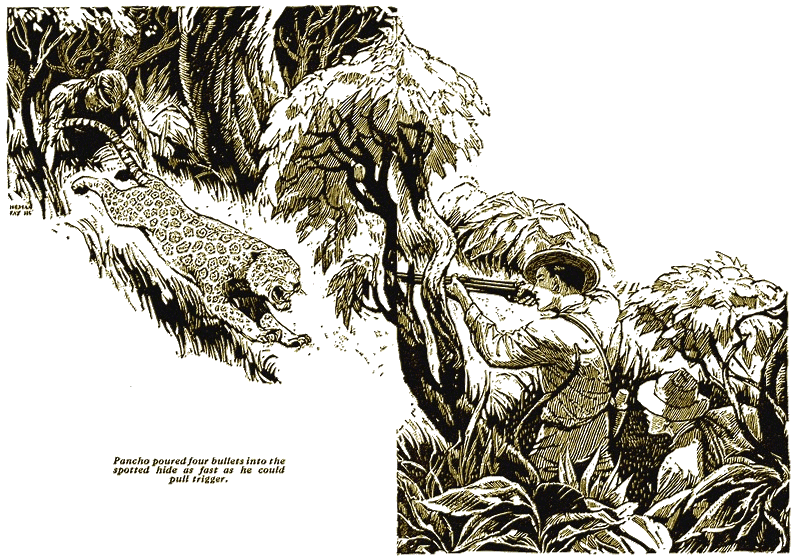

STARTLED by the piercing scream, the two boys dashed into the thicket toward the sound. Bursting through a dense tangle, they came suddenly upon an open space in which an Indian was battling for his life with a tawny spotted creature—a huge jaguar. His poncho was torn and bloodstained, one arm hung limp at his side, and though he struggled frantically to rise to his feet, an injured leg refused to support him. His only weapon, a heavy club, provided little defense against the great cat. Rearing on its hind legs, striking viciously and with lightning speed, green eyes blazing and gleaming teeth bared in a snarl, the creature seemed to be certain of its prey.

All this Bob and Pancho took in at a single glance. To their terrified eyes the jaguar appeared as huge as a lion, but in their pity for the helpless Indian they gave no thought to their own danger. Springing to within a few feet of the jaguar, Pancho poured four bullets into the spotted hide as fast as he could pull the trigger. With a savage roar the creature turned and leaped toward its new enemy with jaws open and great claws wide- spread.

For a moment Pancho's bullets seemed to have no effect and he could almost feel the ripping blow of those terrible claws, the agony of those crushing, gleaming fangs. Bob's excited yells and the snarling growls of the jaguar rang in his ears. He felt certain they were the last sounds he would ever hear.

Staggering back, he swung his empty rifle upward, but before he could strike, the spotted fiend half turned in the air, bit savagely at its flank and collapsed in a lifeless heap.

Pancho tripped and fell but was up in an instant, hurrying with Bob to the side of the Indian who was stretched unconscious on the ground. Wide-eyed, the two boys gazed at the man's ghastly wounds. Scarcely an inch of his skin was left un-scored by the jaguar's claws. The left wrist was broken and the flesh torn from the shoulder exposing the bone. One leg had been bitten through. He still breathed, but it seemed as if death would come at any moment. Despite the seeming hopelessness of the task, the boys started at once to do what they could for the injured native.

"I'm mighty glad we brought our first-aid kits along," said Pancho. "Fill your hat with water from the brook, Bob. We'll need lots of it."

WITH shaking hands they bathed the worst wounds, applied antiseptics and exhausted the supply of bandages. Quickly they tore their shirts into strips, sprinkled them with the remaining disinfectants and placed tourniquets about the torn arm and leg to stop the flow of blood. Fortunately the leg bone was not broken, but the fractured wrist was bad.

"We'll never be able to fix that!" declared Pancho, turning white as he examined the injury. "I know you're supposed to pull a broken bone into place, but—I—I'm afraid to pull this. It looks as if the least pull would tear the hand from the arm. It's terrible!"

Bob, too, was pale and his stomach was giving him most uncomfortable sensations. "Maybe if we shut our eyes and felt of it we could tell where the bones belonged, and sort of push 'em back."

Never had they faced a more trying job, but at last it was done and the two breathed sighs of relief. There were still the deep wounds to be attended to. The tourniquets had practically stopped the flow of blood but they could not be left in place indefinitely. So, mustering their courage once more, the boys carefully examined the raw flesh, washing away the blood, and tentatively loosened the ligatures. To their joy they found the bleeding had almost stopped, and feeling sure no arteries had been severed, they removed the tourniquets and bound up the wounds.

As they finished, they suddenly became aware that the Indian had regained consciousness. His eyes were open, but no murmur or groan came from his lips.

"Gee, he is stoical!" exclaimed Bob. "And he must want a drink."

As he spoke Bob placed a water bottle to the man's lips. He drank greedily, and then, mumbling unintelligible words, reached weakly with his uninjured hand toward a small leather wallet at his belt. Wondering what the contents, might be, Bob opened it and guided the trembling fingers to it. Within were a number of dried leaves and a small lump of what looked like gray chalk. "What do you suppose those are?" asked Bob, as the groping fingers withdrew a few leaves and the little chalky lump.

"I know!" exclaimed Pancho. "It's coca—don't you remember your father writing about the way the Indians chew coca leaves and can go all day without food or rest because of them?"

"Yes, I guess that's it," agreed Bob. "Say, I wouldn't mind having some myself right now, I'm weak as a cat."

"Don't talk about cats being weak," said Pancho. "There's one right over there that was anything but weak."

"What'll we do next," demanded Bob. "Here we are with this half-dead Indian on our hands and nowhere to take him. He won't be able to walk for weeks, even if he gets better."

"I guess we'll have to camp here till he walks—or dies," said Pancho resignedly. "We can't go off and leave him alone. And I guess we can find game. Anyhow, we can eat that jaguar if worse comes to worst."

"Not I," declared Bob. "I'd just as soon eat buzzards."

"It's a shame to lose his skin," observed Pancho with regret. "I may never kill another jaguar. And—"

He was interrupted by the Indian who was trying to speak. They caught the words, "Tonak," "huauki," "uturunku," "kispishkuni," and others, but they meant nothing for the man was speaking in his native Quichua.

The boys shook their heads, and Pancho spoke to him slowly in Spanish, telling him they did not understand. The man nodded, was silent for a moment, apparently puzzling over something, and then in halting, broken Spanish, he mumbled, "You are my brothers. You have killed the great tiger. I, Tonak, am your brother and your slave."

"That's all right," commented Bob. "We'd have done as much for anyone. But I'd rather find a village than have a slave. Ask him where he lives and if it's far."

But the Indian appeared to have lapsed into unconsciousness again.

"He's a queer looking chap," observed Pancho. "Doesn't look like any of the other Indians we've seen."

NOW that they began to notice the man's appearance, the boys discovered a number of strange facts. As Pancho had said, the man was quite different. His skin was a clear golden-yellow in color, his nose large, thin and aquiline, and his long hair was held in place by a narrow band of silver. Even his clothes seemed unlike those of other Indians they had seen. His tunic-like blouse and knee-long trousers were richly decorated with designs in brilliant colors, while about his neck hung a colored cord supporting a carved stone llama and a lapis-lazuli charm.

"I wonder what he was doing here," mused Bob. "Funny he had nothing but a club. I should think—Hello! Look there, Pancho! He had a spear, too."

Not far away lay a broken javelin with the point missing, and the boys also found a powerful bow and two broken arrows. "Looks as if he was hunting," observed Pancho. "Probably the beast came on him unexpectedly. Say, what do you suppose this is?"

He had picked up a peculiar object, a slender hardwood stick about fifteen inches long, with a curved bone grip at one end and a small silver hook at the other.

"Looks like a magician's wand to me," declared Bob, "but I don't see what the hook and handle are for."

Suddenly Pancho whistled. "I know what 'tis!" he exclaimed. "I remember seeing them—or something like them—in Mexico when I was a kid. The Indian boys at Tlaclan used them. They called them atlatls and they used them for throwing spears."

"I don't see how any one could throw a spear with that thing," Bob interrupted.

"I'll show you," replied Pancho. Picking up one of the arrows he grasped the atlatl in his right hand, rested the arrow on his doubled fingers, holding it in place with the first finger, and with its butt against the silver hook. Then, with a sweep of his right arm, he sent the shaft flying across the clearing.

"Say, that goes all right!" cried Bob. "But—look, the old chap's waked up."

The boys hurried to the side of the wounded Indian. He asked for water and when this had been given him he again closed his eyes.

"He's in bad shape," muttered Pancho. "I don't believe he'll live until morning, but we'll make him as comfortable as we can."

By means of canes and palm leaves they managed to rig up a shelter over the injured man, and gathering a supply of brush and dead limbs they prepared a camp-fire near-by. As the sun sank behind the western ranges, the two boys prepared their evening meal, cutting slices of the partly roasted haunch of vicuña and toasting them over a small fire. As they worked the Indian watched with half closed eyes and expressionless face.

"I wonder if he's hungry," said Bob. "Maybe he could eat a slice of meat."

"I don't know," replied Pancho. "If I were as badly hurt I wouldn't have any appetite. I guess Indians must be tougher than white men, though. If we had a cup or something we might make him a sort of broth."

"Can't we use the tops of the thermos bottles?" suggested Bob.

"Fine!" cried Pancho. "They're small but he probably won't want much."

Shredding some of the juiciest of the meat, the boys simmered it over the coals in the metal covers of the bottles. The result, despite the cinders and bits of ashes it contained, was nourishing, and the Indian gulped it down ravenously and asked for more.

"Poor chap!" muttered Pancho. "I'll bet he's suffering terribly but he's not even groaned since we began fixing him up. I'm beginning to think he may pull through yet."

"I'm sorry for him of course," Bob replied, "but it does seem mighty bad luck that the first man we've met should be torn to pieces and half dead, forcing us to stick here when we might be on our way to La Raya."

"Yet, that's so," Pancho agreed. "Just, the same it's got to be done unless the old chap can tell us how to reach a village and one of us goes there and gets help. Anyhow there's no use worrying over it tonight. Things may be different in the morning."

NEXT morning, the Indian appeared to be more comfortable and stronger. "He surely is a tough old bird," commented Bob. "Now I suppose we ought to change the dressings on his wounds."

"Yes, I know we should," agreed Pancho, "but we can't. If we tear up any more of our clothes we'll be pretty near naked, and we're just about out of antiseptics anyway. We'll have to let it go for another day and trust to luck."

"We might wash out the bandages and use 'em over again," suggested Bob. "If we boiled them it would sterilize them."

"Yes, I guess that's so," assented Pancho.

"I hadn't thought of that. I—"

The Indian's voice interrupted him. He was speaking Spanish slowly, in almost inaudible tones. "An hour towards the rising sun—village of my people. The way lies down the valley to a great black rock and the trail is clear. That my people may know you are my brothers and that you come from me, take with you this." As he spoke, he reached uncertain fingers to the charm hanging about his neck.

Pancho stooped and lifted the cord over the Indian's head. The injured man smiled wanly and after a moment's silence, spoke again. "Fear not to enter my village. Cry aloud these words: 'Ama-Yulya-Ama, Sua-Ama-Kuo-lya.'" (No enemy, no thief. The ancient Incan salutation of the Quichuas.)

"That's easy," declared Pancho as he repeated the six words.

"Your people—they know Spanish?"

The Indian nodded. "There are some who do," he replied. "Kespi, Wini, Kenko and others who have dwelt among the white skins."

"One of us must stay here," Bob declared. "If we left this man alone a jaguar or some beast might attack him and— well, there are those vultures up there—" he looked up at the sky where broad winged buzzards swung in great circles.

"I'll go and you stay here," said Pancho. "My Spanish is better. I can talk with the villagers."

"All right," Bob replied. "Hurry all you can."

The trail offered little difficulty to Pancho. At the end of an hour he came to the ruins of a great stone bridge. From there on the jungle had been cleared and the hillsides were covered with small terraced gardens in which grew maize, barley, peas, sweet potatoes, peanuts and various other vegetables, while here and there were fruit trees. Picking up some ripe duraznos (a kind of peach) that had fallen, Pancho almost ran down the winding pathway until suddenly he saw the village just ahead. Evidently, the Indians at once caught sight of him for he heard cries of alarm, and saw hurrying figures vanishing into doorways and children scurrying to cover like frightened partridges.

Not until then did he remember the Indian's six words. He shouted them at the top of his lungs, then moving slowly forward, repeated them. For a time there was no response, but presently the people timidly appeared, ready to turn and run at any moment. The instant he held up the cord with the carved stone llama, however, their manner completely changed. Chattering, exclaiming, they pressed about Pancho as he tried to describe what had happened.

TWO young Indians now stepped forward and the elder spoke to Pancho in fairly good Spanish. "I am Kespi," he said, "the nephew of Tonak, and this is my brother, Kenko. We are your brothers and your slaves, for you have saved the life of our curaca (chief or governor). We will prepare a litter to bring Tonak to his village. But you are weary. Eat and drink that you may be strong for the journey before us."

As the two brothers led him through a narrow street between low stone houses Pancho looked about with intense interest. Everywhere were Indians, but they were not at all as he had imagined they would be. As a youngster, he had seen plenty of wild Indians in Mexico, and somehow he had imagined the Indians of these remote Peruvian mountains as more like the North American redmen—naked, painted, feather-bedecked. Instead he found them far more civilized than the denizens of the smaller Peruvian towns, and their streets, houses, garments and persons all seemed far neater and cleaner than those of the white or cholo villagers. He knew that the Peruvians at the time of the Spanish conquest had been highly civilized under the Incas, but he had never dreamed that any of them had retained their ancient civilization or habits.

Had Pancho been an ethnologist or an archeologist he would have been most amazed and excited, for though he did not realize it, he was among Huancas, so remote from contact with white men that they had retained practically all the customs, the religion, the costumes and the culture of the Incas. Though several of them had visited the outside world, this tribe was unknown even to the Peruvian authorities. It had literally been lost for centuries in its mountain fastnesses. Tonak—and his fathers before him—had taken every care that the people should remain isolated. They had frowned upon the introduction of anything savoring of the white men, the despoilers of their race. No modern inventions were permitted in the village, although steel machetes, axes, knives, needles and similar tools and implements were used.

They lived just as their ancestors had lived before the days of Pizarro. With snares, traps, bows and arrows, throwing spears and slings they secured all the game they needed; there were plenty of fish in the streams; they raised their own cotton, had their llamas, and alpacas, wove the finest of cloths on hand- looms, and were expert potters and basket makers. From the beds of the rivers they washed what gold they required for making ornaments; copper was abundant in the hills as well as pockets of silver.

Of course Pancho did not learn all this at once, but as he ate his breakfast of mote (hulled corn), purutu (beans) and charki (dried meat) and drank the sweet ciderlike aka (corn chicha) and revelled in the luscious duraznos (peaches) and cherimoyas (custard apples), Kespi and Kenko asked innumerable questions and told him something about their village and their people. By the time the litter and the men were ready to start for the distant glade where the wounded curaca lay awaiting them, Pancho had begun to realize that he had suddenly stepped back four centuries or more.

THE litter proved to be a hammocklike affair of llama wool ropes woven into a coarse net and filled with soft woolen robes. Four stalwart men went along as carriers, together with two others armed with heavy spears, slings, bows and arrows and atlatls, and finally Kespi, Kenko and Pancho.

The return journey seemed very short. Almost before Pancho realized it, they came in sight of the little glade and the rude shelter over the wounded chief.

Bob sprang to his feet as the party appeared. "Looks like you've brought a regular army along!" he cried. "Seems as if you'd been gone a week. Say! Do you know who our Indian is? He's—"

"King of the place—" supplied Pancho with a grin. "How is he feeling?"

The Indians had gathered about their chief, prostrating themselves beside him, lifting his uninjured hand to their foreheads and moaning with pity and sorrow at sight of his injuries. Presently one of the warriors hurried to where the dead jaguar lay and began to talk to it.

"Look at him!" exclaimed Bob. "What do you suppose he's doing?" Pancho shook his head. "I'll ask Kespi and Kenko," he said. To his questions the Indian boys replied that the man was asking the spirit of the creature to forgive them for having killed it.

"But why?" asked Pancho. "Why should he ask forgiveness when the beast nearly killed your curaca?"

Then, somewhat hesitatingly, Kespi explained that as the Huancas regarded a jaguar as sacred, and as the abiding place of a very powerful divinity, they felt that whenever it was necessary to take a jaguar's life they must try and propitiate the offended spirit.

"Well, if that doesn't beat anything!" said Bob.

Pancho grinned. "You don't know the half of it, Bob. Wait till you get into their village. Talk about the Yankee at the court of King Arthur! Why, that fellow wasn't in it with us. We're at the court of an Inca! What do you know about that?"

Bob laughed derisively. "Go on, you can't kid me that way!" he declared. "The last Inca died over four hundred years ago."

"So they say," admitted Pancho, as the little group with the wounded curaca in his improvised litter left the glade, "but I'm not kidding you, Bob. From what Kespi and Kenko tell me I shouldn't be a bit surprised if their uncle Tonak is an Inca. Inca merely means a king."

IN due time they reached the village. Apparently Tonak was none the worse for his journey, and with a plentiful supply of clean cloths at their disposal the boys dressed his wounds and were relieved to find that there was no infection and that the cuts were beginning to heal.

"Who'll say we're not heap big doctors?" laughed Bob. "Let's hang out a sign and start a hospital! I'll bet we'd get all the patients we could handle, and more too."

Pancho grinned. "I'll bet we would," he agreed. But they soon discovered there was no chance to start a medical career in the village. A wrinkled, bent old woman arrived on the scene with a supply of herbs, roots and powders, and took complete charge of Tonak's case. Though she grumblingly condescended to let the boys attend to the broken wrist and allowed them to do the bandaging, she replaced their antiseptics with bruised leaves and strange looking unguents, then she dosed the curaca with weird brews. To the boys' surprise, the treatment had an almost magical effect.

"No hocus-pocus about her," declared Bob. "She knows her job all right. I wonder what the things are that she uses. If a fellow could find out he could make a fortune putting them on the market. Funny these Indians should know about medicine."

"Why?" demanded Pancho. "These Peruvian Indians used quinine ages before white men ever heard about it. They had sarsaparilla, ipecac, rhubarb, cascara and castor oil, so why shouldn't they know about a lot of medicines?"

"Listen to the professor!" laughed Bob. "Where did you learn all that, Pancho?"

"Out of a book, dumbbell," grinned Pancho. "I read all I could find about Peru before we came down here."

"So did I," replied Bob, "but I've forgotten nearly all I read. Say, why can't we be on our way to La Raya or somewhere, now the chief has a nurse to look after him?"

"I suppose we can," said Pancho. "I'll ask Kespi and Kenko about getting some one to guide us."

To the boys' astonishment, Kespi insisted that there was no one in the village who could guide them to La Raya or even to Palitos. Tonak, he declared, was the only person who knew the route to the northern settlements. Moreover the journey would be most difficult and dangerous. He advised them to wait until Tonak had recovered.

"I'll bet the old chief won't be able to walk for two weeks," lamented Bob. "It'll be twice as long before he'll be strong enough to take such a trip."

"If he ever is," supplemented Pancho. "With that injury to his leg I don't see how he ever will be able to do much. Seems to me there's something queer about the matter. You can't tell me these people don't know the way to every place in Peru. I don't believe we're so awfully far from La Raya at that. Now why don't they want to take us there?"

"How should I know," muttered Bob, "unless they want to hold us for ransom."

Pancho laughed heartily. "If we were in China or Greece or some other wild place where there are brigands, or even in Mexico for that matter, I might think it possible. But not here with these Indians, Bob. In the first place old Tonak owes his life to us and Indians remember a kindness just as much as they remember an injury. No, old timer, it's something else, but—"

"Well, whatever 'tis we're stuck," declared Bob gloomily.

"Not by a long shot!" said Pancho. "We're safe, we have plenty to eat and drink, and if you weren't worrying about your father, you'd think it a swell adventure."

"Maybe you're right—in a way," admitted Bob. "I can't help thinking how Dad must feel, not knowing what's become of us. If I could only let him know, it would be different."

"Being gloomy won't help him any," Pancho said. "I don't believe he does think anything serious has happened to us. Probably he has men trailing us through the mountains right now. Shouldn't be a bit surprised to see them appear any time."

"Well—" Bob sighed—"I guess you're right. Let's see how old Tonak's getting on, and then go fishing or hunting."

TONAK was doing wonderfully well. Thanks to his rugged constitution and the native doctor's medicines, his wounds were healing rapidly. He smiled as the boys approached his doorway where he was basking in the sun and asked if they were comfortable. Again and again he declared that they were his sons and brothers and that he and all his people were their slaves.

"I wish they were," muttered Bob. "Then I'd order them to take us out of here. Why don't we ask him what the trouble is?"

The old chief nodded as Pancho told him of their desires and asked why the men seemed unwilling to guide them to a settlement or the mine. Then for a space he sat silent, apparently deep in thought.

"My people obey the orders of their curaca," he said at last in his slow, halting Spanish. "I have told them not to take you through the mountains. Ill might befall you and then I, Tonak, would be sad. Few know the way, and it is my wish to go with you. That your father may not be worried I have sent a messenger to carry word that you are safe and will return soon. I and my people owe what we can never repay, but white men, my sons, love riches, and riches we can give you. Wait but a little time and all will be well."

"I guess that's final," observed Pancho. "I was wrong about there being some mystery. Tonak's just afraid something might happen to us."

"I like his nerve!" exclaimed Bob angrily. "Why didn't he tell us a messenger was going to La Raya? Then I could have sent a letter to Dad. And what does he mean about giving us riches?"

Pancho shook his head. "Probably some sort of present," he said. "He used the word ricos which is poor Spanish and means rich people. But I suppose he meant riquezas. Maybe it's ponchos or robes or some gold and silver. I admit it's queer about his not sending a messenger to La Raya and not letting us know. Well, what's the good of worrying? Let's enjoy ourselves the best we can. Hello, here come our three friends. Now let's see how much Quichua we've learned."

KESPI, Kenko and Wini were returning from their hillside gardens and the two boys hurried to meet them. Ever since they had reached the village Bob and Pancho had been picking up the native language. They had found the words easy to pronounce and could "get along," as Bob put it, with the Indian youths by padding out with Spanish.

"Alli-punchantin!" cried Pancho in greeting. "Maipi—er—"

"Maipita-rinqui?" supplied Bob, "only—" he added, "I don't believe that's right. It means where are you going, and I suppose you wanted to ask where they'd been."

The three Indians were grinning. "Alla-right!" said Wini suddenly. The two boys looked at him in surprise.

"Say," exclaimed Pancho, "Where'd you learn that?"

His question was beyond Wini's comprehension. "Na macunipac huasita" (now to my house to eat), he replied in answer to the boys' first question.

"Chaupi punchau huaska chitanipac" (after noon we go for a hunt), added Kespi. "Rini-munani?" (Want to go?)

The boys grinned. "Too much for me," declared Pancho in Spanish. "I get the house and eating part and the 'want to go' but what's the rest?"

"Something about hunting," put in Bob.

Kenko translated. "Kespi says after noon we go to hunt. You like to come?"

"You bet!" replied the boys in chorus.

"Chu-pet!" repeated Wini with a broad grin. "What that mean?"

Unable to explain in Quichua the boys told him in Spanish, and added the words "your life" to the Indian's vocabulary.

Kespi had been mumbling something to himself. "What it mean—Karsh?" he asked.

The boys laughed. "Gosh!" Bob corrected him. It means—well, it means about the same as caramba."

Kespi grinned from ear to ear. "Karsh-chu-petchu-life-alla- right!" he cried delightedly.

Pancho slapped him on the back. "Fine!" he exclaimed.

"Maybe the boys back home wouldn't be surprised if they could look in and see us here!" said Bob, as he helped himself to a calabash of boiled corn and beans, that noon. "Eating lunch with a couple of Incan Indians up here on the back side of the Andes!"

Pancho, who was gnawing at an ear of sweet corn, nodded. "I'll bet if anyone asked them they'd say we'd have to eat monkey or raw fish or bugs or lizards or something," he said. "And here we are eating just as good food as we would back home—corn and beans, baked potatoes, squash and wheat cakes—"

"Barley cakes," Bob corrected.

"Well, barley then, and honey and crawfish and peaches and—"

"If you eat all that you'll die," laughed Bob.

"Well, it's here to eat if we want it," argued Pancho. "Say, it's not so bad being a wild Indian after all. I—"

"Well, cut it out," Bob admonished him. "You've eaten twice as much as any of the rest now, and they're all waiting for you. You forget we're going on a vicuña hunt."

"I'D LIKE to know how they expect to get vicuñas with those things," observed Bob, as the boys watched their Indian friends preparing for the hunt. "From what I saw of the vicuñas we met, a fellow needs a good rifle and has to be some shot to get them. These chaps have only spears and clubs."

As they saw Kespi drop two great balls of fine cord into a bag slung over his shoulder they were even more puzzled.

"Now what do you suppose they're going to use that for?" exclaimed Pancho. "It's too fine to use in tying anything and what do they want string for anyway?"

"Look!" cried Bob. "They're taking a drum and one of those flute things they call quenas, and a horn trumpet. Anyone would think we were going to a dance instead of a hunt, and what on earth are they carrying that bundle of sticks for?"

"Maybe they charm the beasts," laughed Pancho. "I know Dad used to tell about attracting antelopes within range by making queer noises or waving a rag or something of the sort. Maybe vicuñas can be attracted by Indian music."

"After seeing that chap begging the dead jaguar's pardon because we killed him I can believe most anything," declared Bob. "Anyhow, I'm going to ask about it."

The Indians either would not or could not explain. They grinned, and Kespi declared: "All things for make get vicuñas. Pretty soon you see."

It was a long tramp from the village to the puna beyond the mountain summit, and they panted, puffed and perspired as they toiled up the steep, narrow pathway.

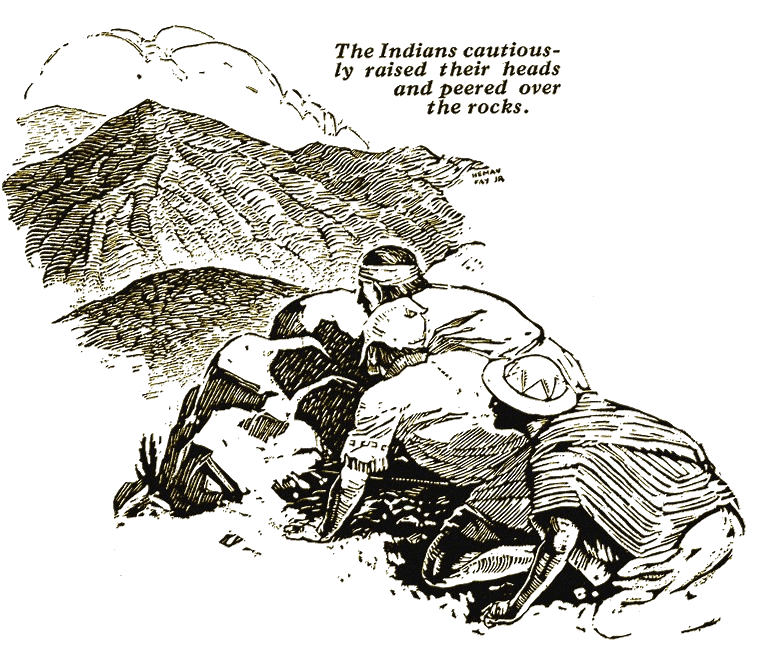

As they neared the top of the ridge, the Indians gestured for silence, and crawling forward on hands and knees, cautiously raised their heads and peered over the rocks. Bob and Pancho did the same. Before them appeared a wide, almost level expanse of puna, and about five hundred yards from where the hunting party crouched was a herd of at least fifty of the graceful, slender-limbed, buff and white vicuñas. Wholly unaware that enemies were near, they played and gambolled about, while the boys watched them fascinated.

Never had they imagined that any living creatures could move so rapidly. Running in circles so swiftly that they appeared but blurs, the creatures would suddenly leap upward as if impelled by springs, and wheeling in mid-air, would resume their mad race in the opposite direction. Others would bound from the earth like rubber balls, and turning complete somersaults, would be off like the wind as their hoofs touched the ground, moving so swiftly that, as Bob put it, you couldn't see anything but their dust.

"It seems a shame to kill them," whispered Pancho.

"Well, I don't see how we're going to get any nearer," said Bob. "The minute they see us they'll be off like a shot." There isn't enough cover to hide a rat between here and where they are."

THE Indians evidently had no intention of approaching closer to the vicuñas. Two of them, crouching, hurried off to the left while Kespi and Kenko, motioning the boys to follow, went to the right.

For fully a quarter of a mile the Indians led the way around the ridge, always keeping below the summit. Then once more they crept up and peered over. The vicuñas were now scarcely visible, and their position was betrayed only by the cloud of dust they stirred up in their frolics.

Rising, the Indians climbed over the intervening rocks with Bob and Pancho at their heels. Then to the boys' surprise, Kespi took a stick from the bundle he carried and planted it firmly in the sand. One end of a ball of twine was fastened to the upright stick, and unwinding it as he proceeded, Kenko walked rapidly forward across the desert for several hundred feet. Then another stick was erected, the twine attached, and again Kenko hurried forward.

"Now what do you know about that!" exclaimed Bob. "Are these fellows going to build a fence or are they stringing that twine so we can find our way back? I—"

"Look there!" cried Pancho, pointing to the north. "Those other two are doing the same thing. It's the strangest stunt I've ever seen."

"Even if it were wire it wouldn't make a fence," Bob remarked.

"They must be crazy," Pancho announced when Kespi had replied to his questions. “They say they are preventing the vicuñas from getting away!"

"Oh, they're just jollying us," declared Bob. "Hello! Those other fellows are close to us."

For the first time Bob and Pancho realized that the two lines of posts and strings were converging. Presently Kespi and his brother were side by side with the two others. Placing two of the strongest sticks about three feet apart they fastened the strings to them and dropped the remainder of the balls of twine on the ground.

Close to where they stood was a low ridge of outcropping rock, and beckoning to the boys, Kespi and Kenko, armed with spears and clubs, seated themselves behind the little rise while the other Indians, one carrying the drum and quena, the other with the horn trumpet and a brilliant red poncho, turned and started back across the puna, following the lines of string.

"I'd like to know when the hunt's going to begin," said Pancho. He turned and put the query to the Indians.

THE two Huancas looked astonished. Then, with a broad grin, Kenko told them the hunt already had begun. Seeing the white boys were still mystified the Indians began to explain. Vicuñas, they said, were strange creatures. Though very wary and fleet of foot they were very stupid beasts and could be easily killed. One way was to find the places where they slept, and while the vicuñas were away during the day build little stone shelters or blinds close to the beds. Then at night the hunters could lie behind these and shoot down the creatures when they came to rest.

At such times, Kespi stated, several of the vicuñas could be taken before the others ran off, and no matter how many were killed they would return to the spot night after night until all had been destroyed. Another way was much quicker and easier. Vicuñas, he informed the boys, would never dare to cross a barrier in the shape of a string. Even if it were a mere thread they would keep clear and follow it along, seeking some place where they might escape through an opening. So, by stretching converging lines of string and then driving the herd between them, the stupid beasts would rush along, until at the narrow opening at the end, they could readily be clubbed or speared. In a few moments, he added, they would see the creatures coming towards them, frightened by the noise of the drum and horn.

"Well, if those vicuñas do come running along here as if those strings were twenty foot walls, I'll swallow anything they tell me hereafter," said Bob, "but the queerest thing yet is the way that chap begged the jaguar's forgiveness."

"I don't know about that," stated Pancho. "Isn't it queer to find Indians living just the way their ancestors did five hundred years ago? Isn't it queer to find Indians like these speaking Spanish?"

"Oh rats!" exclaimed Bob. "What's queer about a bunch of Indians living up here and speaking Spanish? And who says they're living the way they did hundreds of years ago? And how do you get that way about old Tonak being an Inca? Be yourself, Pancho, you're too darned romantic and imaginative."

"And you're too blind and stupid to see what's right in front of your nose," Pancho retorted. "These Indians wear just the same sort of clothes and use the same weapons that are shown in the old pictures of the Incas. They don't use anything modern except knives and hatchets and such things, and I heard one of the men talking to Tonak and he addressed him as 'Inca.' And if you noticed, you'll remember that whenever that old doctor comes in, or anyone else visits Tonak, they always are carrying something on their backs. Well, I read in a book that in the old days they always did that same thing when approaching an Inca. Besides they still worship the sun. You know that half-ruined stone building back of the village?"

Bob nodded. "Yes, I thought of going up there, but Kespi said there was nothing to see."

Pancho grinned. "He would," he declared. "But there's a lot to see. I went over there yesterday when you were off with that little sister of Wini's gathering peaches—and it's all fixed up inside with rugs and hangings and an altar and idols and a big plate with a face on it that looks like gold."

Bob's eyes widened. "Gold!" he exclaimed. "How big is it?"

"It must be as big as an automobile wheel," replied Pancho. "If it is gold it must be worth a fortune. And these people have gold ornaments so why—"

His words were interrupted by the distant sounds of shouts, blasts of a horn and a queer low rumbling noise. The Indians grasped their weapons and rose to a stooping posture, tense, expectant.

NOT more than two hundred yards distant, a herd of vicuñas was dashing towards the spot where Bob and Pancho with the two Indians, Kespi and Kenko, were hidden. And behind the terrified creatures, shouting, beating their drum, blowing on the horn, and waving the red poncho, raced the other Indians in a cloud of dust.

The vicuñas seemed to have lost their heads completely. Every moment or two those in the lead would swing towards the slender lines of twine as if about to break through, only to halt abruptly, snort with terror, and come dashing onward, seeking for some spot not closed by the flimsy barrier.

The boys could scarcely believe their eyes. That such strong, active creatures could be kept within bounds by mere strings, breakable almost at a touch, seemed incredible. But there was little time for wonder. The converging lines soon forced the vicuñas into a struggling mass. They saw the narrow opening ahead and paid no heed to anything else. Behind them were enemies and a terrifying noise; on either side were the fearsome white strings; but before them was an opening, and their one thought was to reach it. Even when the waiting Indians leaped up and took positions on cither side of the opening, the creatures did not turn back. A moment more and the first vicuña leaped between the two last posts, only to be struck down by a club in Kespi's hand. Quickly the Indian stooped, seized the fallen creature by the legs and dragged it aside as a second animal plunged through the opening to be pierced by Kenko's spear.

Bob and Pancho gazed upon the strange scene speechless with wonder. Paying no heed to their dead, the vicuñas continued to spring through the opening and to be killed, until nearly a dozen had fallen. Then, with a shout, the two Indians dropped their weapons and jerked up the posts. The strings fell, and instantly, like a released torrent, the remainder of the herd bolted in every direction.

"More like butchering cattie than hunting," commented Pancho, "but I suppose you can't blame the Indians. It's the only way they can get the beasts, and they need skins and meat."

"How on earth do four Indians expect to carry all these vicuñas to the village?"

Pancho chuckled. "Perhaps they expect us to carry some of them," he said.

Neither boy realized the carrying ability of the Indians. The best portions of the meat, with the livers and hearts, were wrapped in the hides and lashed into four compact bundles by means of woollen ropes. With each Indian carrying a bundle on his back, supported by a band around his forehead, they started back across the puna, gathering up the string and sticks as they proceeded, and seemingly oblivious of their hundred-and-fifty- pound loads.

When they came to the precipitous descent leading down the mountain, the boys shuddered to think what a false step might mean, but the Indians went down at a dog-trot, laughing and chatting as gaily as if the thousand feet of almost perpendicular rock were merely a gentle slope.

Although Bob and Pancho resented the fact that a messenger had been sent to La Raya without their knowledge, the thought that their friends would soon learn of their safety relieved them a great deal. They ceased to bemoan the necessity of waiting until Tonak could make the journey to La Raya with them, and took great interest in their strange surroundings.

Bob was eager to see the interior of the old temple

Pancho had described, and by choosing a time when the men were busy in their fields and gardens, the two managed to reach the place unobserved. Why they assumed that the Indians would object to the visit, neither boy could have explained, yet they both felt that there was some mystery about the place and that their visit must be in secret, and they both felt excited and keyed up when at last they reached the temple and approached the entrance.

"Say," whispered Bob, "suppose some one's in there. What do you think they'd do if they caught us here?"

"I don't know," replied Pancho, also in a whisper. "I'd hate to be caught sneaking about in here—it's a sacred place to them, you know. I don't believe anyone is here now. Come on, let's go in."

On tiptoe they crept forward with fast-beating hearts, and reaching the low doorway with its inward-sloping sides, they peered inside.

"Look!" cried Pancho. "See that big plate on the wall? Isn't that gold?"

"Gosh!It does look like it," said Bob. "Let's go in and have a better look. The place is empty."

Emboldened by the fact that the temple was deserted, and with a final glance about to assure themselves no

Indians were in sight, the boys dodged inside the doorway, where they stood silent, awed, gazing about at the interior of the temple. The walls, of massive blocks of stone marvellously fitted together without mortar or cement, were stuccoed and covered with elaborate frescoes in bright colours showing innumerable figures of men, beasts, birds, plants, geometrical designs, and weird monsters. Many of these were meaningless to the boys, but others were so excellently done that they left no room for doubt.

"That chap seated on the throne looks just like Tonak himself," whispered Bob, pointing to a figure covering half of one wall.

"He certainly does," agreed Pancho, "only he's all dolled up with a crown and everything. Guess he's some old Inca. See how all the others are running towards him carrying presents? And look at that picture over there with all those Indians dancing. And every one is dressed like these Indians in the village. Didn't I say these people are living as they have for ages?"

"Of course the pictures show the same kind of clothes," said Bob. "They were painted by these people. I don't see how that proves anything."

“These people never painted them," retorted

Pancho. "I'll bet these pictures were made hundreds of years ago."

"Well, these rugs on the floor weren't," declared Bob. "And say, isn't that the skin of the jaguar you killed?"

Before them, beneath the great golden sun-disk, was an altar- like affair of dark red stone, and placed upon it was the jaguar skin that had attracted Bob's attention.

Glancing nervously about and moving silently, for the boys felt awed and fearful in the mysterious place, they stepped forward and examined the hide.

"No doubt of it," said Pancho. "It's got four bullet-holes through it and it's a fresh skin. What do you suppose it's doing here?"

"You know how that fellow begged the beast's forgiveness," Bob replied. "I expect they put the hide here to show the creature's spirit they respected it."

"Guess you're right," the other agreed. "Look, see the rainbow over there. It's made of metal, but isn't it natural?"

"Yes, but see here!" cried Bob, who had stepped behind the altar. "Here's a suit of old armour and a sword! Now where did they get those?"

Pancho shook his head. "Must have found them somewhere," he said. "Indians always keep anything that's strange. In Mexico they keep all the burned-out electric light bulbs and almost worship them. They— Holy cats! There's a mummy in it!"

Bob started and jumped back. "Let's get out of here!" he cried.

Pancho laughed. "He's been dead a long time," he said, "nothing much more than a skeleton—like those mummies from Incan graves we saw in the Lima museum. I'll bet he's some old Spaniard the Indians killed in the days of Pizarro. There's no need to be afraid of it."

"Who's afraid?" demanded Bob. "You just startled me for a minute. Hello! What are those things over there along that wall? They look like big rag dolls."

Pancho turned in the direction the other indicated. Resting in niches in the wall were half a dozen bulky, shapeless figures wrapped in bright-coloured cloth, decked with woven bags, ornaments, and feathers. Each was furnished with a crude, artificial head covered with a mask-like face of yellow metal surmounted by a gorgeous feather crown held in place by a gold fillet and topped by a golden ornament.

For an instant Pancho stared at the queer things. Then: "They are mummies!" he exclaimed in a hoarse whisper, "and covered with gold and jewels! They—they must be mummies of kings—of Incas! Gosh! We'd better get out of here."

Bob had not waited for the other to finish. He was already half-way to the door, and the next moment both boys were in the open air.

"Now, who was afraid of mummies?" demanded Bob.

"You were," Pancho told him. "You turned and ran the minute I said they were mummies."

"I did not, I walked," Bob insisted. "It was you who ran after me."

"Well, why did you walk so fast?" persisted Pancho. "You didn't even wait for me to finish speaking."

"I heard what you said — that we'd better get out," declared Bob. "I'll bet you don't dare go back in there."

"I didn't mean we'd better clear out just because of those old mummies," Pancho explained. "But if it's the private burial-place of these Indians' kings, we've no right to be poking about in there. And I'm not afraid to go back. Mummies can't hurt anyone."

"I know that," said Bob. "All the same, it was kind of spooky with that skeleton in armour and all those dead Indians staring at us with their yellow faces."

"Gold!" Pancho corrected him. "Do you know, Bob, very nearly everything in there is gold. There must be a fortune in that temple. I'll bet that's the reason Tonak didn't tell us about sending a man to La Raya, and why he won't let us go back until he's quite ready."

"I don't see what that has to do with it," said Bob.

"Everything," declared the other. "If they had let us send a note we might have told our friends about the place and the gold, and then men would come here and rob the temple in no time. It's the same about going out. Tonak wants to make sure we couldn't find our way back. These Indians are wise birds. If they admitted they knew the way to La Raya they know we'd insist on going, and because they owe the chief's life to us they'd hate to be unfriendly and refuse. So the easiest way for them is to pretend they don't know the way. If they don't, how is that messenger going to get there?"

"Gosh! I never thought of that," Bob admitted. “And—and if they really are afraid that we'll tell about this place, then they'll never let us go."

"I don't know about that," said Pancho. "If they actually sent a man to La Raya they must expect to send us back some time. But just the same, I shouldn't blame them much if they did keep us here. If I were Tonak I'd never take the chance of having a lot of white men come in here and loot my temple and my ancestors' bodies."

"Perhaps he never sent the messenger," suggested Bob. "And why couldn't the men from La Raya follow him back here if he was sent?"

"He'd lose them easily enough if they tried that," Pancho declared. "I can understand now why Tonak was anxious to send word we were all right. He's afraid that if our people don't know, they'll hunt for us and might find this place. But if they know we're safe and sound, and the messenger tells them we'll be back soon, they'll stop searching."

"Yes, I can see that, too," said Bob. "But what I can't see is why the old chief should ever let us go. We might get a lot of men and come back and take away the gold for all he knows."

Pancho laughed. "Don't kid yourself he's such a fool," he said. "He'll probably blindfold us or something. But he can't keep us prisoners here after we saved his life. If you knew Indians, you'd realize that as long as they're in your debt, they're bound to treat you right."

"I wouldn't trust an Indian," declared Bob. "They're all treacherous and tricky, and they hate white people."

"Wild West stuff!" cried Pancho. "You've been reading cheap novels. A lot of Indians always have been friends of the whites, and have helped them fight other Indians. How about Uncus, for example? And in Mexico the babies' nurses are Indians, and the nicest, gentlest, most trustworthy people you ever saw. Besides, even the worst Indians have a sense of humour and remember a friend. Once Dad and some other men were captured by Yaquis—they're like the Apaches, you know—when the tribe was at war with Mexico and they were killing every white man they met. One of them recognized Dad as the man who had cured an Indian kid of a snake-bite, and just because of that the chief freed Dad and the others and guided them to the railway at risk of his life. If a Yaqui will do that, you can bet on Tonak doing as much for us."

"Maybe," assented Bob," but I won't bet on it, all the same."

"Let's forget about what's in the temple," suggested Pancho. "I wonder why white men always seem to think an Indian hasn't any right to his own gold and other valuables. I'll bet we wouldn't like it if some other race came along and helped themselves to everything we owned."

"I'll keep mum," said Bob, "that is, I may tell Dad, but I know he won't tell anyone else if I ask him not to. Come on, let's go down the valley and see if we can find some sort of game."

AS the Indians depended largely on vegetables for food, and secured what meat they required by drying the flesh of deer and vicuñas, the smaller game was seldom disturbed and afforded excellent sport. To be sure, the Indians trapped quail, partridges, and wild pigeons, as well as a variety of wild guinea-pig of which they were very fond. But as they did not possess firearms and their native weapons were not suited to bringing down game on the wing, the big pheasant-like perdiz, the wild ducks and geese, and the smaller mammals were all unsuspicious. Had the boys possessed a shot-gun they could readily have secured all the game they wished. Pancho's supply of ammunition was limited, however. He could not afford to risk wasting cartridges by firing at flying birds or running quadrupeds with the rifle, and even with game as abundant as it was it required no little skill and a great deal of patience to stalk it and bring it down with a rifle-bullet. On this occasion the boys had secured two big partridges, and were stealthily creeping towards a little pond where they had seen a flock of ducks alight, when a peculiar noise in a thicket of brush and small trees attracted their attention.

"What's that?" whispered Bob. "It sounded like a pig grunting."

"Perhaps there are wild pigs here," whispered Pancho. "Listen! There 'tis again."

Peculiar low grunting noises, and the sounds of a creature of some sort scratching or tearing at something, came from the miniature jungle.

"Sounds like something pretty big," said Bob. "Maybe it's another jaguar."

"Let's sneak over and see," suggested Pancho. "I wouldn't mind getting a jaguar's skin."

Silently the boys crept towards the spot from which the sounds continued to come. The brush was so dense that they could see nothing, and when they tried to force a way in they made considerable noise. But the animal, whatever it might be, seemed oblivious of their approach, for the grunts and ripping sounds continued. A moment later the boys were through the thick fringe of brush and were standing in an open wood. The sounds had now ceased, and the two peered about, searching for the creature they had heard. For a moment or two they saw nothing. Suddenly Bob gave an involuntary exclamation. "Look! What in the world is it?" he asked in a hoarse whisper.

Pancho saw it at the same instant. "Gosh! I don't know!" he replied.

Staring at them from behind a tree trunk was a terrifying face. Semi-human it seemed, with small, wicked eyes surrounded by light-coloured circles that looked as if they had been painted upon the dark brown features.