RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

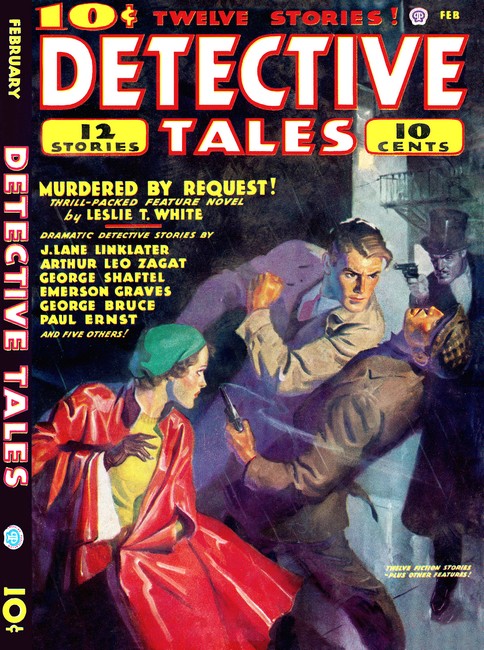

Detective Tales, February 1936, with "Hot Lead Pension"

The kid's knife slashed through the ropes.

Honest Ken Moore pounded pavements long after smarter, weaker men wore unmerited gold shields. But he still played the game square, still was more eager to help his wretched wards than to send them to the pen, still thought self-respect and kindly justice made a cop's life worthwhile.

PATROLMAN Ken Moore's flat feet thumped wearily on the hard pavement and his slow brain struggled with unaccustomed arithmetic. How many store doors had he tried in his twenty-three years of midnight tours? How many...? A half-million, at least. Twenty-three years! Another door, another, and another. There was only one on this block, that of Giuseppe Pallucci's grocery just ahead, down those three steps dipping into blackness. His gnarled fingers clutched his nightstick a little tighter as he went down into the lightless pool.

Ken Moore was not feeling sorry for himself. The figuring was to keep him from getting jittery—from shying away, like a rookie, from every shadow, from every blind, unlighted window along his beat. Out of any one of these a tongue of orange fire might suddenly lick to sear him with the ripping explosion of murderous lead. The word was out to burn him down. It must be. Locked in his old brain was knowledge that "One-Eye" Luccio would never permit him to speak from the witness stand. And he was to testify tomorrow.

If he lived till the morning he.... Hell! Pallucci's door yielded to his testing hand, swung inward an inch before he could check it.

Someone was inside there!

"Put 'em up!" he barked. "I've got you covered."

He crouched in the cloudy shadow of a showcase, waiting, watching. The darkness held a whimpering gasp. Moore slipped his left hand through the leather thong of his club, fished out his flashlight. Its beam bored a white tunnel through the gloom, straight to the source of that sound.

An unpainted, drab counter leaped into existence. A wizened, shabby figure was haunched before it, dilated eyes staring out of an emaciated, pallid face. The intruder was a starved-looking boy, frozen by fright. Frayed sleeves fell back, wrinkling soggily, from uplifted, pipe-stem wrists; from clawed, bony, trembling hands.

A gourd of Gorgonzola cheese was at the youngster's feet, a paper bag from which corrugated strips of vermicelli spilled; a white-powdered round bread. "D-don't shoot, mister," the lad chattered. "D-d-on't shoot. I give up."

Moore's gun was steady; his face grim, appalling. "You're starting early, Ted West. And caught early, too. You know what this means, don't you?"

"Y-yes—I know—the pen."

"No, Ted. Not the pen. They don't send kids to the pen for six months. They send them to the reformatory till they're twenty-one. Let's see, you're how old?"

"Six—sixteen."

"THAT'S five years, Ted. Five years in that place, where they

beat you if you so much as look cross-eyed. Five years, where

they work you limp all day and hound you to sleep as soon as it's

dark. But you don't sleep. You lie awake and you listen to the

other kids whispering out of the sides of their mouths. You hear

them whisper filthy things. And after a while, you whisper them

yourself. And you learn things there, too, from the bigger boys:

How to pick pockets. How to crack a crib. How to fool the cops.

You come out a wise guy after five years, don't you?"

"N-no sir."

"Damn right you don't. But you think you're one, and you're sour on the world. And then you go crib-crazy, Ted. You bang your head against steel walls that going to be around you till you die, and you scream curses nobody pays any attention to, and the spit drools from the corners of your mouth, and—"

"No! Oh God! No!" Terror stared from Ted's big eyes. His scrawny arms came down, quivered in front of him, half-bent, as if to ward off an attack. "No!"

"Yes, Ted. That's what's going to happen to you just because your papers didn't sell so good today and your mother and kid sister were hungry, and you thought Pallucci wouldn't miss a couple of things because he has so much. And what's going to happen to your ma and to little Mary while you're away? D'you think your old man's going to come back—he who went up the river before Mary was born—to take care of them? I never saw him, but I can tell you what he looks like. I've told you already. What he looks like now, you're going to look like when you're as old as he is—and like him, you're not going to give a damn about ma and Mary—if they haven't starved to death by that time because you weren't around to help them. Or worse. Or worse, Ted...."

The boy was down on his knees, now. His hands were stretched out towards Moore, prayer-like, and he was shaking all over as with the ague. "Please!" he whimpered. "I'll never do it again. It's the first time and the last time. Please don't take me in. Please!"

"No, Ted, I'm not going to take you in. I couldn't do that to you, or to your ma, who's scrubbed her fingers to the bone raising you, or to Mary. But the next time..."

"There ain't going to be any next time."

"There'd better not be. Beat it. Go on. Beat it home before I change my mind."

The boy was gone. The old cop scratched his head. This was a nice mess. He'd have to report the break now. He couldn't cover up the marks of Ted's entrance. Nothing was stolen, but there would be a demerit against him on the books. Maybe a fine, for improper patrol.

"HEY cop!" An urgent whisper reached Ken Moore. "C'm here!"

Moore's eyes slid to the figure in the unlighted embrasure of a

closed shoe-store, slitted and wary. At two o'clock, there were

still a few citizens hurrying along Morris Street, some who

shambled leisurely with no reason to hurry. But he wasn't taking

any chances. He didn't know the fellow who furtively beckoned

him, but he knew what he was. His undersized, slight frame,

wrapped in a wasp-waisted overcoat whose too-long skirts almost

touched cocoa-brown suede shoe-tips—his lashless, predatory

eyes glittering out of brim-shadow of a pulled-down derby; his

pasty, ageless face, gashed by a ruler-straight, lipless

mouth—were a dead giveaway.

The fellow's arms angled stiffly out, drawing his pallid, long-fingered hands well away from his pockets, from a grab at a possible armpit holster. If the rat's game was to blast him down, he would have done it from there without warning. One-Eye Luccio's snakes never rattled before they struck.

"Come on over here. I ain't got all night."

Moore sidled guardedly to the show-window, looked into it as he growled, "What the hell do you want?" The plate glass made a perfect mirror. He could see in it the sidewalk behind him and the cobbled, debris-strewn gutter roofed by the sprawling structure of the "El." No one could sneak up on him without his knowing it; no killer-car could roll up, silent and unseen, till it exploded in a lethal spray of Tommy-gun lead.

"You ain't on no spot, Moore." The low, almost inaudible voice slid out from between unmoving lips. "Not yet. Not unless you're dumb enough to turn down the grand in One-Eye's safe that's got your name written on it."

The policeman's weather-worn face was bleak, masked, but a muscle twitched in one grizzled cheek. So they were going to try this way first! "Who are you?" he stalled. "How do I know you come from Luccio?"

"I'm just out of—from out of town. Call me Farrell. You don't know me, but I'm talking for One-Eye all right. How about that grand?"

"That's a lot of dough. What do I do to get it?"

"Talk right on the stand tomorrow. That's all."

"As how?"

"You didn't see Abe Katz bendin' over Sol Levi's corpse. You copped him around the corner as you run up an' you ain't sure which way he was goin'. Maybe he heard the gat-bark same as you did and was comin' to see what was up."

"What good will that do? The bullet in Solo's skull matched Katz's gun."

"Sure. But the bullet's gone now. Sergeant Corbin can't make out how it could have got out of the ballistics room, but it ain't there. Funny how them things happen." Farrell chuckled humorlessly. "An' funnier still—the deputy commish lettin' Corbin off with a reprimand!"

TINY light-worms crawled in the depths of Moore's eyes. "Which

means it's up to me alone whether Katz goes to the chair—or

whether he cops a plea by squealing on the mob. I get it. But why

the sudden generosity? Wouldn't burning me down come a lot

cheaper?"

Farrell shrugged. "Maybe cop-killin' ain't so easy to cover up. Maybe Luccio can use you. I dunno. I'm just sayin' what I been told to say."

"One-Eye can use me! Hmm! I never thought of that."

"Cripes! It's about time you did. Be your age, Moore. Here you been a cop since Broadway was a pup, and you're still poundin' concrete while guys that were still wet behind the ears when you started is sportin' gold shields. They call you Honest Ken an' pat you on the shoulder with one hand while the other's behind their back grabbin' Luccio's dough. What's it got you? You're retirin' in a couple years. You know damn' well who One-Eye is frontin' for. Play along with the Big Fellow, and your pension'll be half a lieutenant's pay. What do you say?"

"What do I say?" Moore murmured, slowly, musingly. Maybe he was a fool. Maybe the thousands of other honest cops were fools. The crooks were the ones who got the promotions, the easy jobs. The straight bulls got lead in their breadbasket. If he said no, that's what he could expect, a bullet in his belly.

"What do I say?" he repeated, and his left hand lashed out, caught and clenched Farrell's coat collar, held it with a grip of steel. "Listen, you mug. What would I say if you came to me and offered me a thousand bucks for my wife? I ain't got no wife. I ain't got no kith or kin. Only the force. Twenty-eight years the force has been my wife, my daughter. The force, not a few slimy grafters that get into it now and then. Sell it? Sell the force? What do I say? This!"

Farrell's head went back to the impact of a gnarled, case-hardened fist on its jaw. The blow lifted him, slammed him down, pounded him into the pavement. He rolled there. And suddenly blued steel glinted in his hand. The stubby nose of an automatic snouted at Moore—spun clattering into the gutter as the cop's heavy toe crashed into the gunman's ribs. He squealed with pain.

"Not this time, Farrell. Not so easy! You'll have to do better than that to get me. But I'm not going to take you in. I'm going to let you go back to your boss and tell him he can't buy me."

A well-aimed kick sent Farrell's gun into a gaping sewer-hole. Moore strode stiff-legged away, shouldering through running, curious wanderers of the sunless slum. A jeweller's street clock caught his eye. Two-thirty. Five and a half hours yet to go. Five and a half hours to patrol the old, familiar course of his beat that now was a path through a night-shrouded jungle in whose every covert death waited, grim and certain, to ambush him.

KEN MOORE'S apprehension, the tense watchfulness with which he

scanned every paint-peeled tenement vestibule, every veiled,

black shadow, could not keep the creeping chill out of his old

bones, the clammy, breathless cold of that four o'clock hour when

the tide of life ebbs lowest and the blood runs sluggish in

mankind's veins.

He halted suddenly, the nape of his neck prickling. Had he caught a flicker of orange out of the corner of his eye? There it was again! A small red glow in a tenement doorway angling across the street, gone as soon as he glimpsed it. Fire! Fire in a slum hallway, getting a grip on tinder-dry wood to roar, in minutes, in seconds, up a stairwell that would be at once fuel and flue for flames. To cut off all escape in terrible, brief instants.

Moore plunged across the street. If he were in time—if he were only in time to stamp it out, to extinguish it before it got a start. Folly to send in an alarm, for by the time the engines came it would be too late for any help. He fairly threw himself up the high stoop, into the lurid vestibule. Dark silhouettes were all about him. An arm rose against the light of a blazing newspaper, swooped down. Rockets burst inside his skull, blinked out into inrushing blackness, into oblivion....

HOT liquid seared Ken Moore's throat, burned down into his

gullet. He soared up out of weltering darkness, choked,

spluttered. The stink of rot-gut whiskey was in his nostrils, his

mouth was full of it. Glass clinked against his teeth. He

swallowed spasmodically, lifted a hand to bat away the bottle.

Tried to lift a hand, and couldn't. His arms were bound to

his sides, ropes cut into his ankles. Someone was bending over

him, shadowy in the blackness.

"Come alive, huh?" Farrell's voice whined in his ears. "But I guess you got enough."

Water lapped greasily, somewhere near by, and a part of the night was angularly solid. "What—what—?" Moore spluttered, choked. Garbage smell, the stench of putrid wood, told him he was up against a stringpiece of the Street Cleaning Department's pier at the foot of Hogbund Place. Queer....

"Them ropes is pasted together an' they'll come loose after you're in the water a while. But you won't know it, Moore. They'll drag you up out o' the mud. You'll be in uniform; your gat'll be in your pocket, an' your belly'll be full o' hootch. Sneakin' down to the pier to booze, they'll say—got soused an' tumbled in! Honest Ken, foolin' us all the time! An' Luccio'll be in the clear. What d' you think o' that, wise guy?"

THE alcohol fumes were a sick whirl in Moore's brain, his

stomach retched. What did he think of that? His name struck from

the rolls of the force in disgrace, his memory an abomination to

the bulls who had been his friends—the honest bulls who did

their duty in spite of all temptation. Katz going free and One-Eye

Luccio triumphant. What should he think of it? It wasn't the

imminence of death in the filthy river that wrenched a groan from

him.

"Over you go!" Hands tugged at his body, lifting him, rolling him up on the stringpiece. If only he could have gone out fighting.... A muffled thud at the pier's land end stopped Farrell's grunting effort.

"Hell!" he splurted. "Them guys was supposed to be watching." He held Moore poised on the brink of death, listening tensely. "If they run out on me...." The sound came again, like a footfall. Moore's throat tightened to cry out, and Farrell rammed a rag into it, gagging him.

"I got to go see." the killer muttered. "You'll keep a minute." He was gone, a slinking shadow merging with the pier's foul shadows. Moore writhed, tugged at his lashings. They gave, slightly. He could get loose of them if he had time to work. If he had time! He fought frantically for freedom, for life itself.

The runted silhouette showed briefly against the pale front of the timekeeper's shack, down there, and turned. He was coming back! He was coming back and Moore was still bound, still helpless. The last flickering hope was gone.

Then suddenly he wasn't tied any more! Rolling over, coming up to his knees, reaching for his gun, the cop was vaguely aware of someone at his side who had come over the stringpiece, of someone in whose hand glittered the knife that had sliced the ropes from him. But his gun-butt was jerking in his hands, orange-blue flame was belching from the pistol's muzzle, was spitting death-hail into the shadows, into the one slinking shadow that was Farrell, killer.

"You got him," his rescuer screeched. "You burned him down!" Moore's gun was empty and his fingers couldn't hold it any longer. It thumped from his hand and he toppled sidewise. "You ain't hurt," Ted West squealed. "You ain't hurt, mister." The kid's wizened face hung above Moore, pale, eyes shining. He clawed the rag out of the cop's mouth.

"No," Moore managed to whisper. "But how—who—?"

"I threw stones, an' he thought it was someone comin'. That gimme a chance to cut you loose."

"Good—kid!" A drop splashed on the old cop's cheek. Another. A sob gulped from the youngster's throat. "Why," Moore said, wonderingly. "You're crying. Why are you...?"

But Ted's face wasn't over him any more. It was gone. The policeman rolled painfully, to see the lad drop to his knees beside the sprawled body of the killer, to see him lift the lax shoulders and press them to his pinched, shaking breast.

Wondering, Moore pushed feeble palms down on the splintered wharf floor, shoved himself up. Just then, a launch headlight scythed the river night, flicked momentarily across the two faces....

KEN MOORE gasped. Death's hand, merciful for once, had

softened the thug's visage, had smoothed away the deep-graven

traces of crime and sinful living. Line for line, feature for

feature, the boy's tear-wet countenance and the wax-white one

pressed close against it were alike. Alike as only the faces of

brothers could be, or the faces of—father and son!

Moore got to his feet, reeled to them, bent to put a comforting, tender arm around the youth's shaking shoulders.

"I killed him," the little fellow sobbed, as though that touch had released pent-up words. "I killed my own father. Ma saw him out the window; she couldn't sleep for worryin', an' she sent me down to call him. An' there he was in the hall with them other guys, an' I saw 'em snatch you. I had to help you, didn't I? I had to watch my chance an' help you. But I killed him doin' it. My father!"

"Ted...." the cop managed to get past the lump in his throat, and stopped. What could he say?

The youngster said it for him. "Looka!" There was the shock of a sudden realization in his voice, and the hush of a great awe. "Maybe—it was meant. Maybe—it's the best thing I coulda done for him. 'Cause now he'll never go back—up the river—to stay for good. He'll never be—like you said in Pallucci's—crib-crazy."

"Never, Ted...." The wetness on the grizzled, weather-beaten face of the veteran cop couldn't have come from under his eyelids. It must have started to rain....

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.