RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

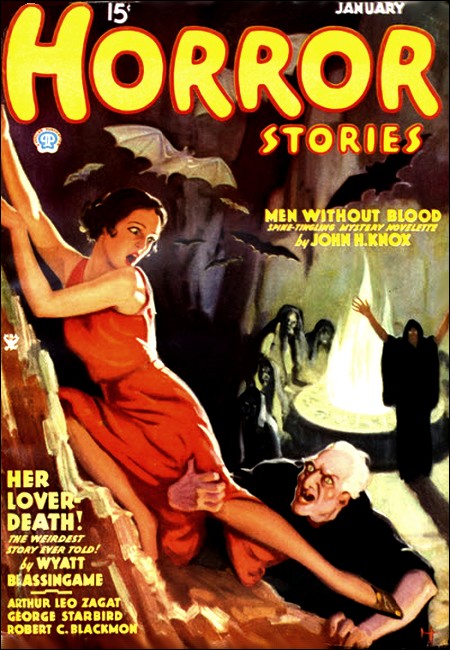

Horror Stories, January 1935, with "Mistress of the Beast"

Were all those mad happenings but a nightmare born of young Stan Dunn's fever-ridden brain? Or did the evil woman of the fog indeed come up from the greedy swamp—to trap him and his companions with their own lust, and drag them back to horror inconceivable?

THE four of us were specters stalking forever through the fog that rolled greyly over the endless swamp, hiding it but not concealing its terror. Now we were four—but we had been five, when dawn had waked us to the discovery that the Mihitchee's sluggish spread was overnight a raging torrent, our flatboats carried off, our only escape through the treacherous reaches of Tallahawn Swamp. Back there, somewhere, Mike Train—freckle-faced, grinning Mike—had slipped off the slimed causeway we followed. He had been the last in file and the first we had known of his misadventure had been his one choked cry. We had heard him splash into the heaving muck, had heard his futile struggles, his screams that at the last had been squeals blubbing through the muck. And we had stood helpless, utterly unable to aid him. Unable to see him, even, underneath the slimy roil of the fog.

We were four hopeless men slogging eternally through the blinding mist. Grief marched with us, and hunger, and fear.

Jim Bradford, our leader, had sworn that this path led through the swamp to safety. He should have known. All his life he had lived on its edge. But what little light there had been was draining out of the fog till it was dully leaden—and still the swamp was on either side of us, and still underfoot was the ooze, slippery, yielding, sucking at each step as though loath to release it.

Was the path circling, eternally circling, through the noisome morass? Were we doomed forever to plod through this unreal, woolly mist in which nameless things bulked, baleful, inimical... There was one now, a vast loom ahead, pouncing!

Jim Bradford shouted wordless warning. Then there was Doc Warner's thin pipe, "Thank God!"

The path lifted under my feet. Leaves rustled. Bill Curtin, shoving his fat bulk forward, pushed me ahead of him and my head came up out of the mist.

Cypresses towered, dark and forbidding, and long grey tendrils of Spanish Moss swung from live-oaks silhouetted against a drab sky fast darkening to night. My heart pounded as I stared around me wide eyed, and I choked back a sob. We were out of the swamp. We were on high, dry ground. There was no more fog. We were saved. Saved!

I wanted to shout in jubilation, but the others were strangely quiet. Bradford peered about, his forehead creased, and I caught a swift glance that passed between him and Doc, carrying a furtive message I could not quite intercept. Even in that moment Warner struck me as ludicrous, his pointed Vandyke bedraggled, dripping, his sharp face flabby, stripped completely of its pompous, little-man's dignity. He was ludicrous, till I saw the dread lurking in his little eyes.

"Where are we, Jim?" Bill Curtin asked. Some apprehension made his deep voice tight. His dew-lapped countenance was no longer red; the broad expanse of his leather jerkin was wetted almost black, and tiny drops powdered his bald spot that was like a monk's tonsure fringed by sparse, russet hair. "Where is this?"

"I'm not sure," came the slow, musing response. "I'm not quite sure. But I think it's what they call Dead Hog Hummock."

Dead Hog Hummock! Why did that name thud on my ears with odd menace? Hadn't Dad told me once...

"Good Lord!" Curtin groaned. "Then we aren't out of the swamp at all!"

"I'm afraid not. If I'm right, this is only a sort of island right at the center of Tallahawn. There's a path on the other side that will take us through to the shore of Lake Ocheebo and civilization, but—" He hesitated.

"But we'd be damn fools to try it in the dark," Bill finished for him. "Best thing we can do is camp here overnight and hope the fog will be gone in the morning."

"Camp here!" Doc twittered. "Here!" His slender hands fluttered as though he were pushing something away from him. "We daren't!"

Bill looked at him, disgust struggling with puzzlement on his round, fat-smothered face. "Why not? The ground's dry here, there's plenty of moss for beds, wood for a fire, and the red berries on that bush are edible in a pinch. What's the matter with camping here?"

"Don't you know? Good Lord, this—"

"Doc!" Bradford's interruption was low-voiced, emotionless. But it cut Warner's sentence off, pulled his eyes to the tall man's face with a curious expression that was almost cringing. "We're camping."

A muscle-spasm contorted Doc's face, and again there was that hysterical flutter of his white, surgeon's hands. I sensed some secret between those two, some knowledge Bradford was determined to conceal from Bill and myself. And an inexplicable antagonism.

"We'd better get busy," Doc Warner said, "making ourselves comfortable before the light goes."

EVEN in the few short minutes we had stood there it had

grown perceptibly darker. "I'll get some wood," I exclaimed,

eagerly. "There's a windrift over there, and the stuff's good

and dry." My skin was dry, my head spinning. But I was the kid

of the bunch. They were Dad's old gang, bluff, hearty bachelors.

He had promised me a duck hunt with them as a reward for winning

the intercollegiate high-hurdles. At the last minute he had been

unable to go, and like the good sports they were they had

insisted on my coming along anyhow. It would be hell if I fell

down on them now. "I'll have it together in a jiffy."

That made them all look at me. "Good boy—" Bill started, then, "Hey, you're green around the gills! Are you sick?"

"No. I'm all right." I jerked away to hide the quiver of my upper lip I could not stop, the hot red I felt flooding my cheeks.

The sudden movement seemed to rattle my brain in its case. The dark trees whirled dizzily and the ground surged up to me. I felt a hand clutch my arm, and for a moment everything went black...

It must have been more than a moment, though, for as sight and consciousness returned I was lying on something soft, and across a flickering little fire Jim and Doc squatted, eating something from their cupped hands. A palm was on my forehead, flabby and cool, and almost womanishly gentle. "Awake, Stan?" Curtin asked quietly. "How do you feel?"

"Pretty—good," I lied. My head was weightless, expanded like a balloon, and everything inside of me was cold although the fire's warmth folded gratefully about me. "I—I'm all right." I pushed to sit up, felt the soft rustle of piled moss under my hands. Curtin's light pressure did not relax and I fell back.

"Lie still. You've got a touch of swamp fever, Doc says, but you'll be all right by morning. Here. Swallow this tablet Doc gave me, and try to sleep."

Shame at my collapse flooded me. But I was too weak to argue. I gulped down the pill Bill thrust between my lips, spat bitterness.

Overhead the sky was a black, starless canopy. Light from our campfire danced orange-red across huge, vaulted tree-trunks, tangled in the long, shaggy grey loops arcing down from their boughs. Shadows moved in the deeper reaches of the dense growth. I started. For one dark shadow flitted in a direction opposite to that of the others!

Blood pounded in my temples, the nape of my neck bristled. Suddenly something sinister brooded over the little clearing, and a mysterious threat lurked in the cypresses. I tried to cry a warning, but could manage only a rasp, a meaningless rasp from my squeezed throat.

The murk into which I stared with burning eyes took on shape. Distinctly a figure moved in the gloom behind Warner and Bradford. Then I was glad I hadn't cried out. For, quite suddenly, a girl was standing at the edge of the light!

Doc grunted, scrambled to his feet. She was a slim wisp of a creature, but the sleazy, tattered stuff she wore hinted at the soft roundness of a body not immature. There was weariness in her poise, and a startled wild shyness, as if she were poised, ready to fly at any untoward move. Her head, somehow, was in shadow—I could not make out her face.

"Hello!" Warner tugged at his goatee, smoothing it. Pushed his other hand through his hair. Ludicrously, he was like a pouter pigeon preening, strutting. "Where did you come from, my dear?"

THE girl swayed toward him, sobbed.

His arm was around her. Natural enough, for she seemed about to faint, but I didn't like the smirk on the little man's mouth. Bradford's face, shadow chiseled, was a marble-hard mask as he watched.

"Lake Ocheebo." Her voice was scarcely more than a breath. "Huntin' terrapin aigs." She was close against Doc now and his arm tightened. Vague resentment stirred within me. "Fog come down an' I got lost."

"You're all right now, honey. We'll take care of you. Come, sit by the fire and get warm."

"Oh!" The exclamation was throaty, strangely seductive. "Thankee. But first I got ter git my bag uv aigs." She pulled away from him, glided off.

"Wait!" Before anyone could move Warner had plunged after her. "I'll go with you." There was an odd excitement in his voice—or was it so odd? Brush threshed as he pushed through. "Wait for me!" His cry was already far-off. Woods silence closed down.

"Fool!" The syllable slid from Bradford's tight mouth. Drowsiness was welling up in my skull; the scene blurred as I fought to keep my eyes open. Perhaps that was why I thought his mask broke for an instant to show leering triumph. Afterwards, I wondered... "He'll get what he deserves."

"What do you mean? What's all the mystery?" Bill's question impacted dully on my buzzing ears. He heaved, behind me, lumbered across and bulked above Bradford. "What's there about this knoll that you're both afraid of?"

God knows I wanted to hear the answer, but the drug took full possession of me, and everything became jumbled in a meaningless melange of rumbling voices, flickering light and shadow, moving forms. It all merged to the greyness of the daylong mist, and a hand beckoned to me from the void, a white, slender hand with tapering fingers. I fought against weakness to lift myself, to go to her, the woman of the fog. Her face formed in the haze—pallid, yearning, incredibly beautiful; and her red lips curved with promise of unimaginable delight. Desire ran like molten fire through my veins, my whole frame burned with it...

No, it was fever that burned me, I realized as the fog and the face gave way to the glow of the fire and the high loom of the ancient trees. I was shaking. My clothes were drenched with my own sweat.

"Bill," I muttered. "Bill."

"Bill isn't here." Bradford's hard, unemotional voice came from an immense height. "He's gone to look for Doc."

"How—how long..." What was it I feared? In God's name, why did fear's gelid fingers clutch my throat?

"Warner's been gone for an hour. Curtin just left. I didn't want him to go."

"Why?"

"Because there wasn't any use. Doc—" He broke off, his head canted as if he had heard something, something for which he had been waiting.

I heard it too. A thin, high-pitched grunting in the depths of the forest growth. Swish of underbrush as a heavy body pushed through it, rushed toward us. Whatever it was it was coming fast.

It burst out of the arboreal gloom, squealed as it saw us. It was a hog!

It was smaller than average, its head slanting forward to a sharp nose. This pig had never been ringed, that was certain... I felt on the instant that there was something grotesquely familiar about it. Good Lord! I caught sight of an odd excresence on its under lip, a triangular, dark flap for all the world like a miniature goatee! My skin was a sheath of ice as I realized that the mud-daubed, foul beast weirdly, incredibly resembled Doc Warner! Even the tiny hooves planted in the soft ground as it skidded to a stop were like his slim, effeminate hands. And the pig's squeal was like his high, thin voice!

Bradford must have recognized the gargoylesque caricature too, for as he stood statuesque and stared at it, I saw his lips move and soundlessly form a name. "Warner!" He didn't say it, but he thought it. I knew he thought it, and saw the color drain from under his bronze, saw a muscle twitch in his cheeks.

Nightmare horror held me rigid, clawed my larynx with an unuttered scream. The hog's head turned to face me, and I saw its eyes. Terror looked out from those eyes, and frantic appeal, and despair. Despair such as no brute beast could know. Those were human eyes! As God is my witness, they were human, human as my own. And a lost soul looked out from them!

THE pig grunted, squealed. It was as if Doc were trying to tell me something, to warn me. His head twisted to Bradford and he snarled. I know a hog cannot snarl, but that one did...

The same paralysis that gripped me must have held the tall man. Awkwardly twisted, he did not move, did not make a sound. But the awed, affrighted stillness was shattered by new sounds from the darkness of the woods, the thud of running feet, the crashing of disturbed brush—and by the hog's frightened squeal as he plunged suddenly into motion again, rushed past me and on.

My head rolled to follow the beast. I saw it hurtle down a steep bank into rolling mists, into the billowing fog hiding the swamp just behind me. Instantly it was a dark mass in the haze, had vanished from sight—from sight but not from hearing. Its screams, its shudderingly human screams, ripped the night with horror—high and thin at first, then blubbing through ooze, then—gurgling to silence...

"Jim! Stan!" a voice cried. "Where's Doc? Where did he go?"

I rolled back to look at Curtin, planted four-square in the clearing. Then he said, "What—what's happened, Jim? You look as if you'd seen a ghost, or the devil."

Bradford swallowed. "Did you—locate Warner?"

"Did I—Hell! Wasn't that him ahead of me, running towards the campfire? I thought—"

"No!" flatly. "No—that wasn't Doc."

"It wasn't? I could have sworn I heard his voice." Bill's glance slid to me, questioningly.

"It wasn't Doc, Bill," I answered. "It was a pig you must have scared up." But my words somehow didn't sound convincing...

"But damn it..." His big-thewed arms went out in a helpless gesture. "I've tramped the whole damn knoll, and there wasn't a smell of him. Nor of the girl. By the Great Horn Spoon, they've got to be somewhere."

Bradford seemed to have recovered somewhat. "Of course they're somewhere. Lying under some bush. Or—by George, I've got it! They've set out on the other path for Lake Ocheebo. She knew where the path came in, and Warner was too damn scared to stay here. He talked her into guiding him, the yellow-livered pup!"

At Bradford's words Curtin's countenance went suddenly livid. Two white spots showed either side his doughy nose, and his small eyes blazed. "You—" he choked. "You—" Stiff- legged, he stumped forward till the round of his belly crowded the other man's leanness. His jaw was thrust forward, bulldog fashion. "Look here, Bradford!" His rumbling growl dropped a note. I suppose he thought I could not hear, but fever had sharpened my senses. "I don't know what you're up to, but I'm telling you now, lay off the boy. Lay off him! I don't give a damn about what you've done to Doc, and I can take care of myself, but the kid's sick and he's Joe Dunn's son. Lay off him."

Bradford looked down at him, his face masklike. "Just what," he said, "do you think I've done to Warner?"

I could see Bill's cheeks quiver. "I don't know. If I did... But you hate him; you've hated him for months, since he beat your time with Lola Prentiss. And now he's gone. He's no more on the way to Ocheebo than we are.

"Damn it, Bradford—this is your country. You've hunted Tallahawn Swamp all your life, know every inch of it. But you pretended to be lost, brought us to this cursed hummock—and let Doc go off with that—that witch." He shrilled the last word, not loudly, but with a hysteric thinning that stabbed me with eerie terror.

BRADFORD'S grim mouth writhed and its corners lifted so

that an aborted smile was painted on his still visage, a smile

of cold contempt. His words slid through that smile, somehow,

without disturbing it. "I faked being lost, eh? Maybe you're

right. But did you ever try to stop Warner from chasing a

skirt, Curtin? Especially if it's a bit torn to show a white

leg, or tight against a small, round breast?"

If ever the lust to kill glared from a man's eyes, it did from Bill's in that moment. I saw his hamlike hands fist till their knuckles whitened, saw what he had of neck swell and cord. But Bradford stared down at him out of slitted lids through which blue steel peered knife-edged, infinitely menacing, and the tall man was encased in a diamond-hard armor of stillness—more ominous, more threatening than any noisy ranting, any blatant threats could have been.

Orange-red firelight carved a tight sphere of luminance out of the night's velvety blackness to contain that titanic conflict, poignant as it was silent and motionless. But intent as I was on the opposing, taut figures I had an eerie premonition that I was not the only spectator of that clash. Some presence lurked in the rolling fog behind me, or in the sinister, impenetrable gloom of the trees; some dreadful presence watched with me; and some inscrutable decision, far other than the issue between them, was weighed in the balance of their struggle.

And it weighed against Curtin! For abruptly the vitality seemed to drain from Bill's hulking frame. I saw the tenseness go out of it, saw his fist unclench. I saw his glare beaten down by Bradford's awful quiet. He shuddered, turned away, a defeated, flabby fat man.

But he halted with some last flare of defiance, twisting back. "By Heaven, Bradford! If anything happens to Stan, I—" He choked as the other's head lifted a little to bring him back into focus, choked as if a fist had been rammed down his throat.

"Leave the boy to me." The measured, slow speech was intoned as though some other than Bradford spoke it. "I'll keep my promise to his father. You said you could take care of yourself. Do so!"

"I will." Curtin said it bravely, but there was little conviction in his tone. And the gesture he made, the little, helpless, quite unconscious outfling of his arm, robbed it of whatever strength it might have had. He turned again, slunk away, squatted wearily at the edge of the fire's nimbus.

I was cold, suddenly cold with dread.

For momentarily, while Bill's back had been turned, a quiver had broken the stony surface of Bradford's face. Grey shadow had flickered over it, and I knew then that the man of steel also was afraid—with a fear the more terrible because of its repression.

The revealing instant was gone almost before it came. Stillness cloaked him again, and case-hardened strength. He moved toward the fire...

Then, in the darkness, someone moaned!... The sound came again, a tiny breaking of the funereal hush that lay on us like a pall. A tiny sound, but it was compact with suffering and with despair. A sound so low that the crackle of the fire must have drowned it to the others...

I tried to call to them, but my fever was in full flood once more and I lacked the strength for even one word. Lacked strength even to make some small movement that might have attracted their attention. When I attempted to throw out an arm the small exertion retched me with nausea, and the firelight hazed so that it was a shimmering circle on the ground.

Not a perfect circle, though. For off there, to the right of the squatting Curtin, its luminance was jogged by shadow. A shadow that had no right to be there, for it was cast against the light.

It was growing, was spreading out toward the hunched, head- bowed man!...

Now I saw that Bradford was watching it, covertly, from a corner of his eyes, while a tight muscle lumped along the ridge of his square, set jaw. The shadow, the blackness that was not a shadow, was within a foot of Bill, within six inches now. If it touched him...

THE moaning from the woods came louder. Bill stirred,

lifted his head.

Heaved to his feet just as the shadow reached him—or did it?...

"Bradford," he whispered. "Do you hear that?" The evasive, shadowy object seemed to slide back into the concealment that had projected it.

"Hear what?" I sensed an undertone of queer excitement in the tall man's low response. "What?" And I was sure that a veil dropped over his eyes, to hide—disappointment?

Curtin was peering into the woods, bent forward slightly as if concern urged him to go see who it was that groaned, but fear held him back. "Someone's in there, hurt. Maybe it's—Doc."

Bradford's head shook ever so slightly, in negation, but he said, "Maybe. We ought to—look..."

"Come on." Bill said it with an effort, and I saw his big frame quiver. "Come on."

Strange. Though the oven heat searing my every cell held me voiceless, motionless, I was seeing, thinking more clearly than ever in my life. An eerie clairvoyance seemed to animate me, and I knew, knew beyond doubt, that if Curtin stepped beyond the radius of the firelight he was doomed, utterly doomed. I read in Bradford's face, though not the slightest muscle moved, that he too knew it. Yet the horror of it was that I could utter not the least syllable to warn the man, and that Bradford did not. His lips moved once, as if to say the saving word—then they tightened. They opened again to say, "All right."

And side by side they strode out of the light into darkness, into black menace.

I was alone, my throat torn, clawed by the cry that would not come, my blazing body in the grip of alternate waves of utter cold and fiery heat, cold and heat. Was it fever or ineffable terror, or both, that shook me as a terrier shakes a captured rat?

It was terror!...

The weird, unnatural shadow was jogging the light again, was sliding across the illumined ground of the clearing. It was slithering slowly, inexorably, toward me!

And I could not move, could not cry out, could do nothing but lie there helpless and watch its infinitely slow, infinitely terrible, advance...

A cold hand seemed to touch my forehead. From somewhere came the thought that with that touch I was lost, damned to all eternity! And at last I shrieked aloud...!

"Stan!" It was Bill's voice, husky, quivering with emotion. "God, Stan, you haven't...?"

I looked up. Curtin was planted, rigid, at the wood's edge, and tightly in his arms was a limp, dark form. He was looking at me, and the vast expanse of his countenance was frozen, grey.

"Bill," I whispered. How was it I knew what he intended? "No. Not yet." I was weak, weak, but the grip of the fever was broken. "What—who...?"

"The girl Doc went off with. She's—hurt. Must have crawled towards our light, fainted." He moved, came forward to the fire, laid her down within its warmth and knelt to her. Fingers of red fireglow stroked her, outlining the long line of her flank, the swell of her bosom—stroked her white neck and tangled in the glossy black mass of her hair.

Bill was clumsily fumbling with her clothing, evidently loosening it. The greyness was fading from his face. A curious light began to shine in his small eyes that was not a reflection of the fire.

"Where's—Bradford?" I asked. He seemed not to hear me. "Where's Bradford?" I repeated, as sharply as I could.

It seemed an immense effort for him to look up, and little tremors of inexplicable fear ran through me as I saw his countenance more clearly. "Don't know," he muttered thickly. "Lost him in th' woods." His glance refused to meet mine, went back to the girl's flaccid form. His pendulous cheeks were flushed. He licked his thick lips...

THE moss on which I lay rustled. I rolled about.

Bradford loomed above me, on the side away from the fire. He was

watching Bill, and his mouth was twisted, as if in triumph; but

there was no triumph in his eyes. Dark anguish dwelt there and

gloom. Here was a soul in torment, I thought, and even as the

thought slid across my aching brain he knelt, close to me, and

his sinewy hand lay across my shoulder. I could feel it tremble

with his inward strife.

The dread that all day, and all the dreadful night, had lain leaden within me redoubled. Fearful forces beyond human experience vibrated about me, elemental forces from the dim reaches of man's ancestral memory. Uncannily, from within the brooding, inky gloom of funereal cypresses and bearded, hoary live-oaks, a baneful shadow seemed to have invested the clearing, so that the very light of the fire was a form of darkness. Dark as the lust that now quivered balefully in Bill Curtin's countenance, pursed his gross mouth, squinted his eyes till they were tiny black beads sunk deep within rolls of fat. Dark as the undulant wave writhing the frame of the girl, as the languid creep of her white arm up over his shoulder and around his neck.

A sob retched his big frame, and suddenly she was clutched within the circle of his arms, clutched tightly to him as his face was hidden by hers. I stared at that embrace, and as I stared I sensed the beat of black wings hovering just above the aura of the darkling fire, and dark, silent laughter shaking the upper, invisible boughs of the woods.

That laughter somehow snapped the nightmare paralysis binding me. Hateful as he was at the moment. I remembered Bill's kindness to me, his watchful solicitude. I jerked up. A cry of alarm, of warning, tore my throat, reached my lips...

The cry was never uttered! Bradford's hand clamped down over my mouth. His arm went around my chest, tightening like a steel band, holding me down, muffling me and clutching me in a rocklike grip.

"Quiet!" he whispered. "You can't help him. It's too late. Quiet, if you want to save yourself."

I struggled. God knows I struggled. I writhed about and beat at him with feeble, aching fists. I was weak, so weak, and at my best I could never have hoped to cope with his gigantic strength. But I fought...

I fought until a sound reached me that told me it was no longer any use to fight. Then I went limp.

My struggles had twisted me around, so that I was looking over Bradford's shoulder into the noisome fog billowing below me and hiding the swamp under its pall. From behind me had come the light trill of a girl's laughter, amused, triumphant, taunting. Then followed that other sound, the sound that stabbed terror through me, and despair. The bestial, snorting grunt of a hog.

BRADFORD'S grip on me relaxed. His palm slipped from my lips, and I was free to turn. Free—except that fear held me rigid, and a desperate, hopeless hope that I was mistaken, that the incredible, impossible thing had not occurred. As long as I averted my gaze I could not be certain. When I was certain I should go mad. But I had to turn. I had to see. Though terror clamored in my blood, and nausea sent bitterness up into my throat, I had to be sure! And so, slowly, slowly, I forced my head around against the rigidity of the muscles in my neck, against the black horror roiling within my skull. I fought around to the trilling laughter and the grunting, bestial rumble that weirdly had the very timber of Bill Curtin's belly voice.

I saw the flickering flames, the woman erect, her coverings awry now, flapping wide to reveal her body, the ripple of muscles across her lean abdomen, the fire-tipped globe of one firm, round breast. I saw the swine planted four-square before her, the huge hog whose glittering little eyes, deep sunk in fat rolls, were fastened balefully on her, whose tremendous flanks were a grisly grey shading to russet along its spine, over its creased neck and to the top of its head, where a disk of white showed to give the appearance of a monk's tonsure. I saw the girl, and the hog—and no one else. Bill Curtin was no longer there....

The laugh of the woman was thin blasphemy, going on and on through the lurid fireglow, through the dark, to the evil that beat its black wings somewhere in that dark. The laugh of the woman was the thin steel of a dagger plunging into my quivering brain, twisting, rending, tearing its pulp so that wild laughter heaved in my own breast like a living thing...

A quiver ran through the body of the beast and it surged toward her. It almost reached her, but not quite. Her laugh broke off abruptly. Her arm lifted, its fingers spread. She gestured—toward the swamp.

The hog squealed in agony, twisted. It plunged past her, past me, down into the fog, down into the swamp! The fog and the swamp took him, gurgling. But he did not squeal, did not fight his fate. Bill did not—

Oh, God! How could it be Bill? How could it?

But where was he then, where had he vanished?

A shadow fell across me, and I realized that Bradford was on his feet, was advancing toward the fire. His hands were clenched at his sides, his arms stiff. He walked like one in a dream, and his set face was the hue of death.

The woman turned to meet him. The smile quirking her red mouth was incarnate evil.

"Are you satisfied now?" His question fell flatly on the vibrant night, edged with agony. "Am I free?"

Deep-throated, vibrant, her voice as she answered—no longer held the shy breathlessness of the simple native girl. But longing was still in it, yearning that queerly, despite my horror of her, clutched my throat with desire. "Free?" She appeared to ponder. "You promised me four in lieu of yourself. It comes to me that you promised four."

Bradford's neck corded, and his whole frame tensed. "I could not get the fourth to come."

"But there is another. Of course there is another. The pretty boy. I like him."

"Yes." I could barely hear him. "Yes, there is another. But..."

"I want him."

Bradford, still moving forward, hid her from me now. And as though cords binding my body, my brain, had snapped, terror exploded in me, flung me to my feet. Almost before I knew I had moved, terror had flung me away from the circle of firelight, into the woods whose murk was not as fearsome by far as the light in her eyes as they dwelt on mine. It was I she wanted!

A scream sounded behind me, a man's scream, hideous. I pounded into an unseen trunk, caromed off, ran on through vines that whipped around my legs and tripped me, through brambles that tore at me, through slithering, dank shadows that were putrid with the odor of death. I ran on, and knew that something followed me, sliding through the tangle as though it were not there.

Some sixth sense told me of this, some sense inflamed by terror and the incredible things I had witnessed. For that which pursued me made utterly no sound. Not that there was not tumult enough in those lightless woods—the crash of my own frantic flight, the screams of awakened, terrified birds. And the beat of dark wings, ever the beat of dark wings close over my head.

I ran. But it seemed that my stumbling, boneless legs spurned only some treadmill that whirled by underneath and kept me in the same spot, no matter how fast I ran. Grotesque dark shapes that were twisted trees wheeled by, and came again, and wheeled by again. Knives stabbed my lungs; my throat clamped. I wheezed as I fought to breathe. I stumbled, fell; heaved up to run again. And terror ran with me, and terror was just ahead, and terror ineffable followed me, its hot breath on my neck.

A voice, throaty, vibrant, called to me. "Wait, pretty boy. Wait for me." A voice behind, always just behind no matter how fast I ran. "Pretty boy. Wait..."

A LIGHT flickered ahead, a lurid light against which

dark boles of ancient trees, twisted, grotesque, were

silhouetted as with mute horror. I burst through them, and

gasped, whimpered as I realized that the light was that of the

fire I had just quitted, that my mad flight had but brought me

in a great circle, brought me back again to the clearing where

Bill...

Across the clearing, down the bank, grey fog rolled lurid in the light of the fire. Beneath it, the swamp. Oh, God!

Better that than... I lunged across the bank again, toward that red-grey roiling.

As I reached the haze it seethed, lifted a grey tendril, shapeless—clotted. It was a slender lithesome figure standing above the fog, standing on nothingness, surging forward to meet me at the edge of the bank! It was the woman of the fog, her arms outstretched to me, her dark eyes fathomless with desire!

And suddenly, as I felt her warmth close, close to me, fear left me. My veins ran molten fire, and passion blazed in my brain. My own arms, aching with desire that matched hers, clasped the quivering ecstasy of her body, clasped it tightly against mine. So ardent was the flame of her, so ardent the flame that consumed me, that the dross of clothing between us seemed to be burned away, so that my flesh became one flesh with hers.

Yet all the time a hard crystal ball of horror and despair dwelt deep within me—as I knew, even in the transcendent ecstasy of that embrace, that the fate I had seen overtake Warner and Curtin was my own fate. Horror unspeakable, and incredible despair. And rage at him who had betrayed us to save himself.

The ball of horror grew now till almost it quenched the ecstasy. Intolerable itching rasped my skin, as if bristles prickled it from within. Yet still I held her close to me, draining to the uttermost the passion for which I was paying so dearly. Piercing agony ran through me...

In that instant a whirlwind struck me, burst us apart, flung me asprawl. I twisted. The woman of the fog was a white flame, radiant Bradford stood before her—his fists that had struck me, reft me from her, unclenching, his tall form aquiver. His eyes were on hers, and the hard contours of his visage were breaking, were blurring like wax in the heat, so that the horror that dwelt within him peered through, and the awful despair.

His throat worked, his lips moved, making no sound. Then his arms came up, not reaching to her but spread wide in a gesture of abnegation, of defeat.

"No," he husked. "Not the lad. Not the boy. You cannot have him."

"But that was the bargain you made. Four in your stead. Four! And I have had but three. Was not four the bargain?" Was it her eyes that said it, sliding to the swamp, and then to me, and back to him? Was it her eyes, or her lips? I do not know. Everything was blurring then, and I do not know. "You would not break our bargain, Jim?"

A long quiver went through him. A gasp burst from him, a gasp of sheer terror. But he spoke, squeezing speech through the fingers of awful fear clutching his throat. "You cannot have him."

A veil seemed to shimmer between me and those two, a grey haze, and darkness was welling up in my brain. But I could still see them, and hear them, hear her. "You said four, Jim, the night the fog reached your house on the edge of the swamp and I came to you. It had been long since my desire had been fed, men long had shunned the swamp and the fog, and I was direly athirst. But you bargained with me, and promised me four in your stead if I would let you go. And I agreed. And now—there is only one way you may break that bargain."

"Only one way." Had his voice dropped so low, or were my ears dulled? "I understand. And I choose that way."

"Jim!" Her cry pierced the haze between us, and it was a cry of triumph, of gloating gladness.

They were shadows now, wavering shadows in a pall of greyness through which I could barely see. But those shadows moved together, melted into one...

And the darkness within my skull welled up, swallowed my brain.

GRUFF voices beat dully to me, stirring me awake. I opened my

eyes to daylight and the sun. The gloomy cypresses, and the

live-oaks with their grey beards, were gaunt against the

blueness of a fresh-washed sky; but somehow they were no longer

sinister, no longer threatening. I was lying on a bed of moss

and I was weak, so weak that I could not raise my head.

Lord, I thought, what dreams the fever had given me. What awful dreams! But it was gone now, and the dreams with it.

"Bill." I called, feebly. "Bill, I'm thirsty. Is there any water?"

There was no answer, though the burr of voices still continued, from somewhere a little distant. My companions must still be asleep. But my mouth was full of cotton, my lips cracked, and my body, my legs, itched like all possessed. With the petulance of the convalescent, I called again. "Bill! Doc! Mr. Bradford! Mi—"

I caught myself. Mike was drowned in the swamp. Or was that, too, a part of my dream? "Bill!"

Grisly terror crept in on me once more, the terror of my weird delirium. I fought it off. They had risen early. I told myself, were prospecting for food, or for the path to Ocheebo, not disturbing me. It was their voices I had heard.

I sat up, swayed an instant, dizzily. Off there the black, heaving surface of the slough stretched, foetid, ominous. And far out, two figures were bent, working at something. Two figures, slattern, bedaubed. Not Bill or Doc or Bradford. Not any of my friends.

They must be on the other side of the hummock then. But the knoll was small. I should be able to hear them, they me. Good Lord, the fever had dried my skin so that it itched intolerably. I slid a hand inside my shirt to scratch.

Oh, God! Oh, good God! Stiff, short hairs prickled my fingertips, bristles that covered my chest, my belly.

An icy wind took me, and I was shuddering, shivering as with an ague. It couldn't be! Impossible that it could be! Those things that had happened last night, those incredible things, had been dreams, foul spawn of a brain racked by fever, delirium.

A spasm convulsed me, jerked me to my feet, set my arms waving over my head as I screamed, "Bill, Doc! Where are you? Where—" I swayed.

The strangers out in the swamp had seen me. They were yelling, running towards me. I toppled, crashed down. Why were my shoes so strangely loose on my feet, why did it seem as if I had no toes?...

Footfalls thudded, and two leathery-skinned faces bent over me. "Godfrey," someone said. "How in tarnation did ye git here?"

I looked up at them. The dull-eyed, moronic faces were handsome to me in that moment, for they were human. "Walked," I gasped. "Walked through the swamp. Slept here, last night."

Incredulity showed in the bleary eyes, and a curious withdrawal. "'Tain't possible," one said. "They ain't no 'un's passed th' night on Dead Hog Hummock an' lived ter tell th' tale."

"Four of us did." My speech was mushy, difficult.

"Four!" Their words slurred. "Where are th' others?"

"Somewhere," I gestured vaguely. "Somewhere on the hummock."

They looked—and shook their heads. Beside them and myself, Dead Hog Hummock was utterly uninhabited! Neither Bill, Doc nor Bradford was ever found, there or elsewhere. It is certain they lie somewhere in the black, heaving deeps of Tallahawn Swamp. But in what shape...?

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.