RGL e-Book Cover©

RGL e-Book Cover©

Astounding Stories, August 1934, with "Beyond the Spectrum"

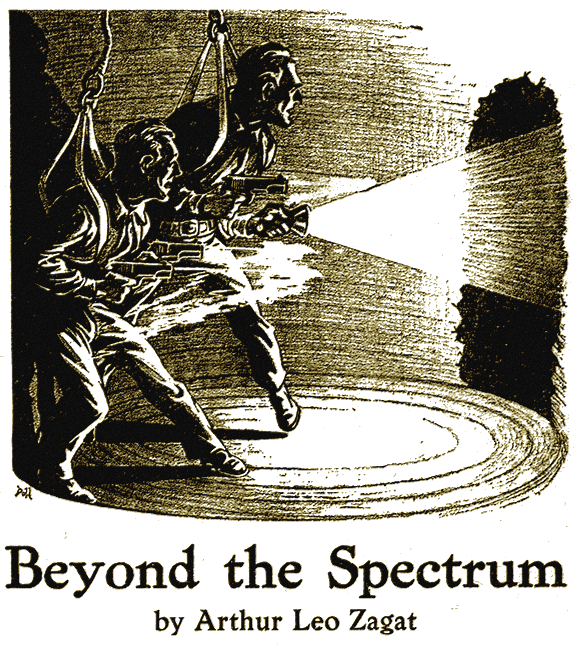

Straining, sweating, we poured lead into that awful hole.

"TANASOTA! Tanasota! All out for Tanasota!" The welcome cry of the brake-man signaled the end of my trip. The "all" meant me, I noted; no one else escaped from the sooty discomfort of the decrepit accommodation local.

The old depot platform of the little Florida town was deserted. Strangely so, for the well-kept shops, the trim streets radiating from the station park would seem to indicate that this was a bustling, modern, ultra-American settlement. A tan and blue signboard caught my eye:

WELCOME TO TANASOTA

POPULATION 5,000

HELP US GROW

TANASOTA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

Henry Maury, President

But the blazing sun had park and streets to itself; no

line of autos banked the high curbs of the gleaming sidewalks,

not even a dog moved.

Far up the main street of the town a cloud of dust appeared, darting toward me. It solidified into an automobile approaching at breakneck speed. In moments it was skidding to a stop at the platform—and Tom Denton was jumping from it.

I was thunderstruck at the change two weeks had made in him. His face was gray and lined, his smile of greeting palpably forced. And the laughing humor of his eyes had given place to—was it grief, fear, that peered at me from those burnt-out orbs?

"Ed, old man! Thank God you've come!" The hand that seized mine was trembling. "Quick! Hop in and we'll get away from here!"

There was an urgency, a driving haste in his voice that choked back my questions. Before I quite realized what was happening, he had me in his car, was hunched over the wheel, was hurling the machine furiously in the direction from which he had just come.

"What the hell is going on here?" I shouted against the wind that whipped the sounds away from me.

"Wait! Can't talk now. Got to go like the devil, or—" The rest was lost in the noise of our passage.

The town whizzed by in a blur and we were out in the open. I caught glimpses of tall palms lining the road, of green lawns and white-sanded driveways curving up to vine-clad houses. I had a feeling there was something wrong about those houses. I strained through the tears evoked by the rush of air and realized that, hot as the day was, every door was tight shut, every window closed and blinded by shades. Nor was there anyone to be seen on road or lawn.

Definitely a pall of fear lay heavy over the neighborhood. What was its cause, I wondered. One thing was certain. I had been right in my interpretation of the queer telegram that had plucked me from my quiet lab at Kings University in New York and had brought me post-haste to this beleagured southern town.

I knew it by heart, that message; had reread it a hundred times on the dragging journey:

TANASOTA FLA

PROF EDGAR THOMASSON PHYSICS DEPT

KINGS UNIVERSITY NEW YORK

DO NOT NEED YOU STOP NO TROUBLE STOP ON NO ACCOUNT TAKE SIX FORTY ONE FROM NEW YORK TO-DAY—NOTNED MOT

I must have looked a goggle-eyed ass as I stared stupidly at the yellow slip. It hadn't made sense. Going to Florida had been as far from my mind as going to the moon. And I knew no one with that queer name.

Then a thought struck me. Tanasota! Wasn't that where the Dentons had gone two weeks before? The odd signature leaped out at me. Notned Mot. Tom Denton, of course, written backward. Then—suddenly it was clear as crystal—the message too was to be read backward, its meaning reversed! With growing excitement I translated the cryptic words: "Need you. Trouble. Be sure to take the six forty-one from New York to-day."

I HAD just time to make that train. It wasn't till I had

sunk panting into my seat in the Pullman that I had time to

wonder what it was all about. The Dentons were my best friends:

tall, broad-shouldered Tom with his laughing eyes and endearing

smile, and Mary, whose shimmering brown hair came to the middle

of her husband's barrel chest. Tom and I had been room-mates at

Kings, and although he had gone into geology and I into pure

physics, nothing had ever broken our comradeship. And

Mary—well, it wasn't my fault that her name wasn't Mary

Thomasson.

Tom had done some rather good work at his specialty, the finding of subterranean water in hitherto dry locations, but hadn't made much money. So we had had a big celebration when the offer came from Tanasota. A typical boosters' town, with a super-active chamber of commerce, we gathered. They had concocted a scheme for making the region a tourists' paradise: hotel, casino, swimming pool, tennis courts, links, and all the rest of it.

All contracts had been let and work was about to start when the artesian wells suddenly failed. Catastrophe, ruin, stared them in the face. In this emergency they had heard of Denton. The generous proposition they made included the rent-free use of a bungalow, and the couple had departed, jubilant.

WE rounded a curve and I saw a low white house, a flutter

of white skirts at the just-opening door. Brakes screeched, the

car skidded through dust, slewed half around. There was a crash,

and the machine lurched sickeningly. The hood sank to the right

and didn't rise. I was surprised to find I was still in my

seat—uninjured.

Tom paid no attention to the wheel that had smashed against a roadside boulder. With a laconic, "Come on. Quick!" he seized my bag and ran up the path.

"All right, Mary?"

"Safe, dear. And you?"

"Not a sign of them."

A sigh of relief trembled on her lips. Tom picked up a stout iron bar and set it across the locked door in sockets that had been provided for it. Mary turned to me.

"Ed! I knew you would understand and come." Her face was lined with worry and sleeplessness. And in her eyes was the same haunting fear that had startled me in Tom's. I kissed her, and her lips were icy-cold under mine.

"Are you two going to have mercy on a fellow and tell him what this is all about?"

Tom's mouth twisted in a pathetic attempt at his familiar smile. "All hell's broke loose, Ed. Literally, I think. But sit down; it's a long story."

THE cozy living room showed Mary's genius for home-making. But, although the mid-day sun was blazing outside, the

chamber was illuminated only by shaded electric bulbs. The two

large windows were tightly closed, dark blinds were pulled down

to the very sill, and a network of steel wire mesh had been

nailed over all.

The place was a fortress!

"You know what brought me down here," Tom began. "After my first inspection, I was puzzled, still am. From surface indications there should be no difficulty in finding water in this region. The wells that failed run from seven hundred to a thousand feet deep. I decided to extend one lying about a quarter mile south of here, one about nine hundred feet.

"I had my drill set up. At the bottom of the hole we found a stratum of hard Archaeozoic Gneiss, the earliest formed of all rocks, certainly no younger than eighty millions of years. Ordinarily I should have given up all hope of finding water in that spot as soon as I discovered this formation. But it was my theory that some minor earthquake had opened a rift through which the underground stream had dropped to a lower level. So I continued drilling.

"We hadn't gone down fifty feet when the lower section of the drill dropped down into nothingness! I had what was left of the drill raised, and since it was growing dark, stopped operations for the day, leaving old Tim Rooney to watch over the material.

"In the morning I went out bright and early. I expected to find Tim asleep—there wasn't any real need for leaving him out there, but I was put out to discover that he was nowhere in sight.

"The next minute I forgot all about the old codger's dereliction. For, Ed, that hole, which the night before had been only four inches in diameter—had widened to a span of three feet! Not only right at the top—just as far down as I could see--and the focusing searchlight I flashed down there sent its beam for at least four hundred feet! There isn't a boring machine on earth that could do a job like that in the twelve hours since I had left the spot! It was downright impossible!

"My first thought was to get hold of Rooney and find out what had happened. I sent a youngster chasing to his home.

"My messenger returned. Tim's wife hadn't seen him since he had left to take up his vigil the night before. I cast about. I found his tracks, where he had walked about for a while. Then—one spot—they vanished. But there was a long furrow in the loam, as if a heavy body had been dragged along the ground. And that furrow led straight to the opening—ended there.

"No. Old Tim's wife hadn't seen him. Nor has anybody else since! He was the first."

He whispered the last sentence. Then a wave of emotion seemed to overwhelm him, to make it impossible for him to go on. He looked off into the distance, dumb misery on his face. His wife put out her hand and stroked his.

"It isn't your fault, Tom; it isn't your fault, no matter what they say."

Apparently he did not hear. Again he was whispering, to himself, not to us. "He was the first—but not the last. And the end is not yet."

In the silence that followed I became aware of a sound—it seemed to be at the window. Very faint it was—a sucking, sliding noise as if someone were drawing a wet rubber sponge across the pane. I thought I imagined it, till I saw the others staring at the window. Mary's hand was at her breast. From somewhere Tom had produced a squat, ugly revolver.

Then the sound stopped. Without explanation, Tom plunged back into his story.

"I tried not to believe the evidence of the furrow I had found. I organized searching parties, sent them out in all directions. But toward evening I was convinced at last that old Tim was gone.

"Of course, he might have fallen down the hole by accident. But something told me this was not so. I telegraphed for a windlass that would enable me to go down the shaft. It would arrive the next morning. Meantime I decided I would watch the opening during the night. I couldn't rest. I must do something to solve the mystery.

"Jim Phelps, a splendid young chap who had been acting as my assistant, insisted on sharing my vigil. There was no moon, that night, and the sky was overcast. We built a little fire for light. The flip of a coin decided that the first watch was to be Jim's. I stretched out on the ground.

"I had thought I would be unable to sleep, but the strain of the day and the warm balmy air had their effect. How long I slept I do not know. But I was snapped awake by a shriek. In the dim light of the dying fire, I saw Jim at the very edge of the shaft, his whole body contorted in a terrific struggle against—nothing. There was nothing there—I swear it—but the boy was fighting, lashing out. His heels, planted deep, were being dragged through the ground against the utmost efforts of his tensed body!

"I had almost reached him when he suddenly collapsed. He rose a foot in the air—and disappeared down that infernal hole. My grasping hand just touched his hair as he descended.

"At my feet lay the searchlight. I snatched it up and pressed the button.

I saw him, twenty-five feet below. He wasn't falling; he was drifting down, as if something were carrying him! I watched his limp body descending, vivid in the bright light. I could pick out every line of his white face, every striation in the smooth side of the vertical tunnel. There was nothing there, yet something was carrying him down.

"God knows I'm no coward, but I turned and ran from that accursed spot, ran with the horrible fear of the Unknown tearing at my brain; ran until, after countless years of running, I saw the door of this cottage."

Mary broke in:

"I was awakened by a choked cry outside, and the thud of something falling against the door. It took me an hour to revive him. And then, when he gasped out what he had seen, I thought with a chill at my heart that he had gone stark, raving crazy."

"The chief of police and the village president were quite sure of it the next morning," Tom resumed. "In fact, they were convinced that I myself had thrown both men down the hole in a maniacal seizure. They were leading me out to take me to the county hospital, when something occurred that changed their minds.

"There are no other dwellings between this house and that—that place. There we were—I was just stepping into the chief's car. Mary, in tears, was pleading with him not to take me. Suddenly someone pointed. A wild figure was coming down the road, reeling from the fence on one side to the rails on the other, tossing its arms in the air. It stumbled and fell, but kept on crawling toward us.

"I was the first to run up the road, the others close behind. It was Jim! I called to him, and he lifted his face to me. Where the eyes should have been were two empty holes—two deep, red pits—staring out at me from the mask of white dust! He lifted that awful face to me, and laughed.

"Out of poor Jim's babblings and gibberings we could strain not one morsel of information as to what lay at the bottom of that infernal bore. But when the doctor examined those scarred eye sockets, he turned to us with sheer unbelief.

"'I can't understand this, gentlemen,' he said. 'There is every evidence here that a marvelous piece of surgery has been performed. Not only the eyeballs themselves have been excised; but the optic nerves, in their entirety, and all the complex system of muscles that enable the eyes to do their work properly. There are only one or two surgeons in the world who could perform such an operation!'

"Do you realize what that meant, the astounding implication of Dr. Wells' finding? This thing that came from below, this invisible thing, had intelligence, knowledge, skill, equal to our own. Think of it!

"There was no longer any question of my sanity. The town authorities, in the persons of the president and the police chief, were now convinced that a blacker menace confronted them than the mere presence of a homicidal maniac. They held a whispered consultation in the corner of the hospital reception room where we had received Dr. Wells' report. Then they called me over.

"President Maury did the talking. 'Listen, doc,' he began. 'We've got to keep this thing damn quiet, or—'

"'Quiet!' I exploded. 'Hell, man, what we've got to do is telegraph the governor for the State police, and the university for the best men they've got on paleontology and physics, and get busy trying to find out just what there is down there, and how to fight it!'

"'Yeah, and have the papers get hold of it. Nothing doing! By the time it was all over, Tanasota would be ruined forever as a resort. People would never forget it.'

"I was astounded. 'How on earth can you be thinking of money when there may be thousands of those invisible things, whatever they are, ready to pour out and carry off everybody around here?'

"'Might as well be killed by them as starve to death. There ain't nobody for fifteen miles around who ain't stuck all they've got, includin' what they could raise by mortgages on their houses and land, into this development. The contracts are all signed. If we stop now, all Tanasota township will be ruined. Nope, Tanasota's got to handle this itself; and, by jingo, Tanasota kin do it!'

"WE set to work at once. Steel rails were crisscrossed

over the opening, and a six-foot-high mound of re-enforced

concrete erected on this armored base. By evening the concrete

had set. Thomas was almost cheerful.

"It was dark when I got home? Janey Ruxton, a sweet kid just home from Miami University, was here, chattering away to Mary. We played three-handed bridge till a little after nine. Then Janey left. She wouldn't let me take her home; it was just a bit up the road and nothing could possibly happen to her. Shortly after Mary thought she heard a scream, but I laughed at her. It was just the screech-owl that had startled our city ears several times before.

"The next morning the phone rang at about ten. It was Mrs. Ruxton. When was Janey coming home?

"The receiver shook in my hand. 'Why, Mrs. Ruxton, didn't she get home last night?'

"'No! She said when she went out that she might possibly sleep there. Mrs. Denton thought you might be detained at your work till late. Don't tell me she isn't there!'

"I mumbled something about having come in late and having just waked up. I'd ask Mary and call her back. I had to think. Could it be that—Just as I hung up, Mary called to me that Thomas and Maury were coming up the path.

"'They seem excited! I wonder what's happened?' she said.

"There was something ludicrous in the way they trotted their pendulous paunches up the path. But the stricken look on Thomas' face held no humor. He called to me almost before I had the door open.

"'Doc, doc, have you seen anything of Jimmy?'

"Jimmy was his sixteen-year-old son.

"'No, I haven't—why do you ask?'

"'Got to find him, got to find him!'

"That's all I could get out of the father. But the village president explained. Young Jimmy had gone out before dawn; he was to join some of the other boys fishing. A half hour before, one of his chums, having returned, had phoned to inquire why he had not met the crowd.

"The same thought was in all our minds, I think. 'Wait here,' I snapped, 'I've got a hunch.' Before there could be a reply, I was down the path and in my car.

"I shot the machine out into the field and straight up to the solid cairn we had made the day before. I almost crashed into the stone. For—it hit me in the face like a physical blow—straight through the top of that huge boulder of concrete and steel a circular cavity-yawned—three feet across! When I could tear my staring eyes away from that black hole I saw, at the foot of the mound, the crumpled and broken fragments of a fishing rod!

"I couldn't have been away long, for when I got back here Thomas and Maury were just starting to follow me. I gasped out my discovery—careless how I hurt these men whose obstinacy I blamed.

"'It's your own damn fault,' I blazed, alternately hot with anger and chilled with horror. 'If it hadn't been for your being stubborn, this wouldn't have happened! Now will you let me call for help?'

"Thomas held himself erect by one shaking hand on the lintel. His white face turned in piteous appeal toward Maury. But, though his eyes bulged with horror from a face that was green and gray by turns, the other could not be moved from the stand he had taken. He thundered an emphatic 'No' to my demand, and Thomas' silent entreaty.

"I stormed and raved, and Mary added her pleading, but Maury was obdurate. From somewhere the stricken father summoned strength enough to second his superior's fiat.

"'Whatever you say, Hen,' he mumbled brokenly. 'Whatever you say, I'll stick to. You know best.'

"In answer to my threat to take matters in my own hands, Maury laid down the edict flatly:

"'No telephone from you goes out of the local exchange, nor no letter nor telegram that I don't O.K. And you'd better not try to leave the township, 'cause you won't get far.'

"I gave up. But Mary broke in. 'Tom,' she said, 'Edgar Thomasson was to leave to-day for his visit to us. We'd better telegraph him not to come, or Mr. Maury will think we tricked him.' She was writing as she talked. 'Here, will this do?' I wondered what she was driving at, but played along.

"She handed what she had written to the president. He spelled out the message. 'Looks all right,' he said at last; 'but what's this here name signed at the bottom?'

"'Only Tom's name spelled backward. The boys have always signed their letters to one another that way. They won't tell me why; some secret society hocus pocus, I suppose.'

"Maury could understand that. The vast expanse of his vest was the background for a half-dozen varied fraternal emblems. 'O.K. You kin send it. Here, I'll take it in to the depot myself.' He stuffed the paper into a pocket. 'I'll get John home now, and then get busy on the phone tellin' everybody to look out. Meantime, doc, see what you kin figger out. Don't worry about expense; I'll see that you get all the money and help you need.'

"They went out, Thomas walking like a man in a dream.

"That's about all. They haven't done a damn thing since except get an armored car somewhere and patrol the roads with it. Lot of good that does! And they've got all the houses for miles around locked up like this one. There the stubborn fools sit in the dark, while those things prowl around, groping, groping, at the doors and windows. Sooner or later they will find a way to break through our defenses. And then—"

TOM buried his face in his hands. "It's my fault," I

heard him mutter; "it's my fault."

I wanted to argue with him about it, but somehow I couldn't say anything. For long minutes there was silence, flat, imponderable. Finally he looked up with a twisted smile.

"I'm all right now. Sorry I'm putting on such a baby act, but it's got me, Ed. You've heard the story now; what do you think of it?"

"I don't know what to think of it, Tom. One thing, though, I've been wondering about. I take it that there's been no further attempt at confining these mysterious visitants. How is it then that they have not reached other communities?"

Denton shrugged. "They do not seem to wander far from the shaft. Perhaps something in conditions on the surface reacts on them unfavorably and limits the time they can stay above ground. Their tracks do not appear further than a mile away."

"Their tracks? Then they leave a definite impression on the ground?"

He rose. "Come; I'll show you."

I followed him to the nearer window. He listened tensely, ear close against the mesh. Mary went to the other window and listened too. Again I remarked the ravages the horror through which she was living had made on her winsome face.

"Hear anything, dear?" Tom called.

"Nothing, Tom; I guess it's safe." But the girl remained crouched taut against the mesh.

"Look here, Ed." Tom poked a long paper cutter through the screen and pushed aside an edge of the blind. His gun was in his other hand. I bent over and peered through the opening.

I could see just a small patch of bare, soft soil. But all over that patch was the spoor of the monster—six thin lines radiating from a small round depression—footprints the like of which the upper world had never seen. Twelve inches from end to end, and four across. Somehow those molded markings in the ground made the horror real to me, more real than all Tom's vivid tale.

Then that occurred that bristled the hairs at the nape of my neck with ancestral fear, that drove the blood from my face, but held my staring eyes riveted to the little strip of loam. One by one new tracks appeared, forming whole in the matrix of that soil.

Something was walking across the front of the house—something that I could not see!

My throat was dry—so dry that I could not cry out. That weirdly-forming progression of telltale marks passed beyond the range of vision, but another set of prints began to form. Another set that marched straight toward me!

Suddenly an eye was looking into mine through the glass—a blue eye that did not wink! An eye, and nothing more! Tom must have seen it too, for the black shade dropped between me and the eye. Then, right there in front of me, I heard again that sucking, sliding noise. From left to right across the pane it moved, and the blood froze in my veins.

A crash of smashing glass!

The black shade before me bellied inward, flattened against the wire mesh and was held there by the force of something that crushed against it.

"Shoot, Tom, shoot! It's coming in!"

That cry seemed to tear from out my very vitals. At top and side the screen was tearing away from the stout nails that held it! Tom's gun roared—I felt the scorch of its flame on my arm as I thrust at the screen, fighting to hold back the thing that was pushing in, the thing whose power made nothing of my puny strength. Again the gun roared. I felt the invader flinch. White rents appeared in the shade, rents through which the unobstructed sun leered in. A form was outlined against the bulging cloth—Tom fired again!

I felt the thing falter and fall away.

I fell back, wilting from the terrible exertion. Suddenly the room was flooded with light—sunlight! As I whirled about, a scream ripped through me. Mary's scream!

The other window was stripped bare of shade and screen. In the center of the room, struggling against—blankness—was my chum's wife. Her hair had fallen about her shoulders, her eyes were staring from a terror-distorted face, her mouth was open to scream again. Her little fists were flailing at the vacancy before her, her legs, lifted from the ground, were driving against the nothingness that held her, the unseen thing that was carrying her inexorably toward the gaping window!

We dove together to her aid—Mary's form shielded her captor from Tom's gun. I reached her. Something twisted around my waist and lifted me from my feet. My hands tore at the cold, hard, invisible thing that writhed but held me fast. I thought I saw brown eyes gleaming in midair. Then I was hurtling across the room, to thud crushingly against the wall. Tom, caught in the invisible grip, fought for a second, then he too was sliding helpless along the floor. With a last moaning scream, Mary soared through the shattered window and disappeared.

BRUISED, dazed, horror-filled, I dragged myself up,

reeled across toward the jagged opening. Tom was before me. He

scrambled through, reckless of the broken glass, the tearing

wire, and I after him.

Already a hundred feet away, floating, apparently unsupported, some three feet above a flat field, I saw Mary. She had fainted, mercifully. She rose over a fence, flew southward up the road. I realized that I was running, giving everything that was in me to a burst of speed greater than I believed myself capable of. Tom was ahead of me. His gun was still in his hand, but there was nothing at which to shoot save the figure of his wife.

We leaped the fence, were dashing up the road. I cast one despairing glance back at the car—if only that wheel were not smashed we might have a chance. As it was, though, I ran on after Tom's speeding figure—reckless of the agony that burned my lungs. Despair flooded me. The thing we pursued sped faster than our uttermost efforts could drive us.

Little spurts of dust showed in the road, the only evidence that the unconscious girl was not being borne away from us by some wind that we could not feel. They ceased, but the tall grass in a field at the left swayed and was trampled down under the weight of an invisible runner. Ahead I could see a rounded gray hump, knew it for the futile barrier that had been erected against the incredible menace from below. Dimly I was aware of a clatter from somewhere ahead on the highway, the barking exhaust of a gasoline motor. But I was rushing through the field now, my straining eyes fixed on Tom's running form, and on Mary ahead.

She rose to the mound—dipped within. Tom reached it in a final spurt. I was only moments behind him. He beat furiously with his hand and his gun against the hard rock. As I seized and dragged him away his hand was a torn and bleeding lump. "They've got her, they've got her!" His voice was a high-pitched shrill monotone. "Oh, damn them, damn them! Let me go!"

He was fighting against me—I couldn't hold him against his maniacal strength. He broke away and was scrambling up the stone.

"I'm going down for her!"

"Wait, you fool!" I had hold of his kicking foot. "Wait! I'll go with you—wait just a moment." Somebody was beside me, an arm reached past me, a hand clamped around Tom's ankle. Together we pulled him back.

Four men were crowded around us, their canvas belts heavy with holstered revolvers and studded with cartridges. Behind them bulked the gray-painted, awkward shape of an armored car.

Tom was quieter now, but he still muttered in a nerve-racking monotone: "I've got to go down and save her eyes; I've got to go down and save her eyes."

"Tom!" I shouted as if he were deaf. "Tom, stop that damn muttering and listen to me!"

But he looked at me wildly and mumbled: "I've got to go down and save her eyes."

Time for heroic measures. I gritted my teeth and slapped him stingingly on the cheek. He rubbed the red mark my hand had left, and sanity came back to him.

"Oh, Ed," he said brokenly, and the agony in his tones wrung me. "They've got her down there! I must go down to save her. Please don't hold me back!"

"Of course we're going down." I fought to keep the hysteria out of my own voice. "But jumping down a thousand-foot hole and getting smeared all over the bottom isn't going to do Mary any good. Now, is it?"

"No, Ed, you're right. I—I don't know what I was thinking of. But when I saw her go down there and remembered the empty sockets in Jim Phelps' face and the way he laughed—"

One of the men from the armored car was speaking.

"Gee, doc, it sure is tough! We saw her swinging along the road and you guys after her. But we couldn't do nothing—if we'd let loose with the machine gun we'd have cut her to pieces."

"Maybe—maybe it would have been better if you had. But it's all right, boys. I know you would have helped her if you could. I told Chief Thomas this patrol of yours was no earthly good."

DURING this interchange my mind was racing. What were

these monsters, these invisible things of horror? Were they

elementals, imponderable phantasms, myths come true?

No! Unseeable they were, but material. Their tread left prints in the mud; grass bent beneath their passage. That had been a very real bulk against which I had struggled at the window. Tom's bullets plunging into it had killed it.

They were not invulnerable.

I twisted to the haggard-faced, quivering Tom, grabbed his arm and dug my fingers into it in my excitement.

"Listen! We've got to get ropes, a searchlight, guns!"

He stared at me wide-eyed, then snapped: "Come on!"

We piled pell-mell into the steel-clad truck, shot all out along the road, our siren rising and falling in howls of warning to a non-existent traffic. Not ten minutes after we were back at the hive-shaped stone.

Were we too late? Even as I snapped my instructions to the hard-faced men of the patrol, the question burned through my mind. In seconds the end of the windlass rope—luckily the reel still stood at the head of the shaft—had been fastened about me in a rude harness. Tom too was looped into the cable, four feet further along. About our waists hung borrowed cartridge belts, each with two holstered automatics.

"Those are explosive bullets," the patrol leader volunteered. "Get one o' them in you and they'll be picking up the pieces for a week."

From my belt swung also a large mirror I had snatched up somewhere, to which I had attached a long cord. In my hand was a powerful flashlight that also could be hooked into my belt at need.

Trailing the long rope, we mounted the concrete. A dizzy look down the long bore. A farewell glance at the sunlit scene, the familiar world I might never see again. No prepossessing sight was this bare field, with its rank, lush grass. Yet at that moment it was very beautiful. Weasel thoughts of fear came flooding in. Almost I turned back, but I saw Tom watching me, saw the look in his eyes. I stepped over the edge and felt the rope harness constrict about me as it took my weight.

"Lower away!" I called.

DOWN, down we went. Light faded and Stygian darkness

wrapped round us. I seemed to have passed beyond the boundaries

of time and space, seemed doomed to swing forever in this

darkness, this otherwhere. Down.

From above came an urgent whisper. "The light, Ed; the light!" I remembered the torch in my hand, pressed the contact. For an instant the sudden glare dazzled me. Then I saw, not six feet below, the bottom of the long shaft. "Hold it, Tom!" I felt the rope vibrate to the double tug of his signal. The wall stopped moving upward.

Just under my feet there was an opening in the side of the vertical tunnel, dark, foreboding. Otherwise my light revealed nothing as it glinted back from wet rock. I unfastened the mirror and lowered it by its cord till the bottom edge rested on the stone floor. It had twisted as it dropped so that it faced the blank wall of the bore. I raised it a bit, twirled the cord in my fingers. Slowly the silvered glass swung around. When it faced the opening, a quick dip of my hand stopped it so. I paid out a little more cord—now it was just right, its surface canted at a forty-five degree angle to the plane of the ground.

The shining rectangle caught the vertical beam from the torch, flashed it out through the arched gap. Mirrored in the glass I saw a long, low gallery, sliced through age-old rock, a gallery that widened and heightened as it swept away from the shaft. The ancient stone was rotted and crumbling, and still wet from the flood that, draining away, had left the well bone-dry. I could make out dark patches that must be openings to caves or other corridors. Nothing moved in the dim subterranean passage, nothing that I could see. But I could hear faint scutterings, a low murmuring that should not have been in that vacant pit.

The mirror leaped inward, as if something had grasped it! The cord was jerked from my grasp. The next instant there was something snakelike about my ankle, something that tugged downward—something horribly cold. I grabbed for a gun from my belt, fired down past my feet. In the confined space the roar of the discharge nearly deafened, but there was a muffled explosion below, and the invisible thing around my ankle fell away.

"Down! Down!" I shouted. In a moment my feet skidded on some slimy substance, gripped the ground. I could not see it, but I knew I was standing on the fragments of the thing my explosive bullet had spattered into destruction. First blood to us!

I hooked the torch into my belt, had the other gun in my hand. Just in time! An unseen tentacle coiled around my shoulders. I fired blindly, and it was gone. Tom's two weapons were roaring at my side, spitting lead into vacancy, into emptiness that yet was filled with a vast whisper of alien sound, menacing, horrible. My ears told me there was a ravening horde out there, a throng of strange things gathered to repel our invasion of their immemorial domain. But my eyes saw only blank walls and untenanted space.

We backed against the rock behind us and poured the contents of our weapons into the invisible host. I glimpsed Tom's face—his glittering, half-mad eyes, his lip curled in a snarl. From ahead came a rushing tumult, a hurricane sound as of a torrent flooding up to overwhelm us. My guns were hot in my grasp, my arms weary with firing. But the herd came on. I could hear them, closer, closer. I could see the debris on the labyrinth floor flatten under the masses of unseen feet—the front of that pressed-down space nearer and nearer—fifteen feet—ten feet away. A moment more and we should be overwhelmed, crushed under their thousands. The fire from my guns ebbed—they were empty—no time to reload. Tom's last shot blazed out—and the mad rush halted!

I saw the stigmata of the things' presence retreat.

As we reloaded feverishly, not knowing how soon again the things would sweep to the attack, a voice came out of the black silence beyond my torchbeam! A human voice!

"Help! Help! Oh, help!"

A woman's voice! Mary's voice! Echoing.

"Help!"

A great shout from Tom. "Coming! Where are you?"

More faintly. "Here, Tom, here." Somewhere far ahead.

There was a sob in Tom's voice and an exultation as he cried: "She's alive, Ed, she's alive!" A giant fury surged through me, and I roared in response:

"She's alive! Give 'em hell!"

We started out, step by step, into the nothingness that was filled from wall to wall with the monsters we fought. We did not need to see them—we blazed straight ahead and knew we could not miss. The thunder of our firing was continuous now as, wordlessly, we gained a certain rhythm so that one fired as the other loaded, loaded as the other fired.

Slowly we forged forward, fighting in a red madness. Beneath our feet we felt the slippery life-fluid of the things we destroyed. Their shattered bodies tripped us, writhing tentacles whipped around us and were torn away as we pressed forward, always forward. And ever the rustle and the murmur of that obscene throng fell back before us, and ever as on one side or other we reached an opening in the wall we paused a moment to listen, and ever Mary's voice came from ahead.

"Here. Here we are. Hurry! Hurry!" That weak voice, guiding.

"Tom, Ed. Come quickly!"

We dared not hurry lest we slip and fall into that shambles underfoot. We dared not hurry lest the dragging rope behind us catch in some projection and tangle us helpless while the things rushed back and swamped us beneath their teeming numbers. Our guns roared and thundered, roared and thundered as we harried them before us. An insane, nightmare battle there in earth's bowels, a thousand feet beneath sunshine and green grass!

A nightmare fight, but even nightmares have an end. We came abreast of a portal in the wall, and in the pause Mary's voice came loud and clear.

"Here! In here! Ed, Tom. Here!"

It choked.

"Hold them, Tom!" I swung round, threw my light into the cave. Three human forms outstretched on platforms of bare rock. Two quiet—limply recumbent. One struggling, fighting against something unseen that held her down. Mary!

Something glittered in the gleam of my torch. A scalpel! Descending toward her face, her eyes! My gun butt jumped in my hand—the scalpel clattered to the ground. Mary's arching body slumped, relaxed, quivered and was still.

"Hold them, Tom!" The rolling crash of his guns told me he was holding them. I plunged in, got to her stony couch. Her face was death-white, her eyelids closed. I bent to her—fearing. Before I could find, grasp her pulse, she stirred, and a long breath whispered from her ashen lips. Her lids quivered. What would I see when they opened? I never knew eternity could be compressed into a half second!

They were open! Her brave eyes looked square into mine!

Oh, thank God! Thank God!

"Ed—I knew you'd come!" Then a sudden fear flared in the eyes I had thought we were too late to save. "Tom! I heard his voice. Is he—"

"Safe. Right outside, fighting like mad. Come; we've got to get out of here." She struggled to rise. I looked at the other two, fearfully quiet. How manage all three? One of us must be free to hold back the things.

Brave girl! She saw, understood.

"Take the others. I'm sure they're still alive. Give me your guns and the light."

I swung them to my shoulders and we started back. How we got to the foot of the shaft I can't remember. Guns blasting behind me, writhing horror underfoot. At the last it was a mad rush as a shouted something from Tom warned of some new danger. I had to tug only once at the rope; those waiting above must have been tensed to the breaking point. The burdens on my shoulders bumped crazily against the sides of the bore.

I rolled down the concrete mound. From a great distance I heard voices, cheering.

Then—oblivion.

THERE isnt much more to tell. Visitors who flocked to

Tanasota's famous resort wonder why that field on its outskirts

is sunk so far beneath the surrounding terrain, but no one will

tell them. A half ton of TNT did that, dropped down the shaft to

hell and exploded there.

We found the body of the thing Tom had killed at the bungalow. In my laboratory at Kings I made certain tests, confirming the theory I had formed concerning the nature of the monsters.

The secret of their invisibility lay in their epidermis, corresponding to our skin. This refracted all the light between ultra-violet and infra-red, the spectrum by which we humans see; carried it clear around them so that to our eyes they appeared perfectly transparent. I have done the same thing with a set of refracting prisms.

My assistant, Jim Thorne, was puzzled. "How then do they see? If light passes around them, none reaches their brains."

I smiled. "They are, of course, absolutely blind to our light. But remember sunlight never reaches them in their underground home. It is ultra-violet light, and other vibrations beyond our spectrum, emitted by radio-active substances in the rotting rock that pervade that region. Utterly black to us, they see by it as perfectly as we do by the light of the sun."

Thorne got it. "Then that is why they cut out Phelps' eyes, and the others?"

"Right! They were blind, or almost so, in our world, which they sensed was a so much better abode than their own. They wanted human eyes to see things here above. It must have been poor Jim's optics that glared at me through the window, his eyes in the head of one of the monsters."

WHENCE came those strange beings of an inner world?

Perhaps they had their genesis in the very dawn of time, when old

earth was still a molten ball and life itself existent only in

resistant spores. Perhaps some of these spores, these life seeds,

were enclosed in the vast bubbles that formed, and burst, and

formed again, or were caught in some huge folding of more solid

rock, and so were imprisoned within earth's crust. Then, through

the slow aeons, these primal cells may have evolved in their own

far different way as their luckier brother seeds that were our

far ancestors evolved on the surface. Perhaps—

God grant that never again will they find a way to the light.