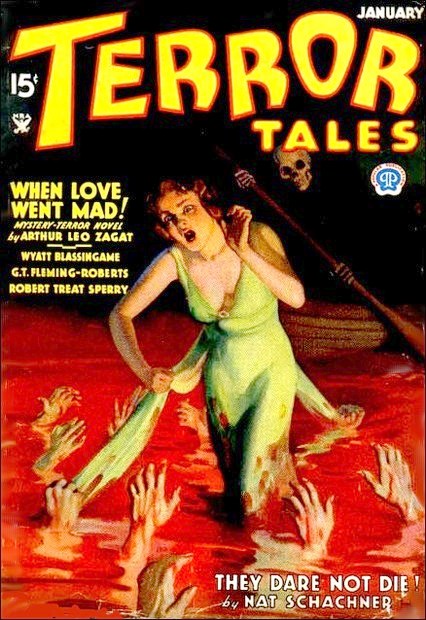

Terror Tales, January 1935

Within the dank parlor of that empty, country house lay a corpse that had come up from the grave itself. While Emma Wayne watched helpless from the dirt-smeared windows of that darkened, tragic dwelling, fleshless grey Things crept relentlessly upon the man she loved, waylaid by horror on the night-shrouded slope of Big Tom Mountain...

EMMA WAYNE'S small hand shook a little as she fumbled her key into the grey door of the ancient Sprool house, and she was shivering inside her thin suit-coat. But it was not only the sharp chill of dusk that had set her quivering. The old dread lay like a leaden lump in her breast, the dread that, as far back as memory went, inevitably had come when the sun's last red rim vanished behind the jagged ridge of Big Tom and night began to fill the valley's bowl.

As in the old days, the circumscribing mountains were tightening the ominous loom of their ring with the withdrawing light, were becoming formless, vast bulks of blue-grey menace; and, beneath the haze blurring their slopes, crawling, eerie things of the night stirred to unholy being—or so whispered the legends of the countryside. To Emma the very hills were endowed with uncanny, motionless life as they thrust gigantic shoulders against the darkling sky like quiescent monsters waiting in silent, age-long patience; waiting till at last their appointed time should come to crush, with one temptuous gesture, the puny human lives scuttering in the valley.

The girl's mouth twisted bitterly. Here she was just as Kurt Tradin had predicted two years ago, returned to the mountains and their gloomy forebodings... The borrowed horse she had tied to the gate down there whinnied, the sound edged with shrill fear. Startled, Emma whirled to it, peered fearfully into the gathering shadows. What on earth was the animal afraid of? Why had it cried out as if it sensed some threat in the unkempt, overgrown garden? Why was Emma herself afraid, not knowing of what? Perhaps because the place was so uncared-for, so desolate. Gram shouldn't have—

But of course, grandmother was dead. That was why Emma had come back, why Milton, the husband she had found in the city that had been otherwise so cruel, was joining her here. The little old lady whose bleared and rheumy eyes had pleaded with her not to go, was dead—and buried. Kurt's letter had brought the tidings when it finally had reached her, its painfully addressed envelope scrawled with the postman's notations that explained its week's lateness. Gram was in the little cemetery above, where the village was hidden by Big Tom's jutting spur, and the old house was empty...

Something slithered along the door, thumped softly. Emma's breath caught in her throat. Tensely, she listened to the thud of her own blood in her ears and—silence. Silence that lay on the hills like a grey shroud, that was a living, tangible thing within the house. Silence that in itself was fear.

The girl bit her lip. "It's nothing," she assured herself. "Nothing at all." She did not realize that she was speaking aloud. "Just—just my imagination." And indeed there was now no sound, inside or out, save for the pud, pud of the restive horse still straining to break free the rein that held him. "I'm a fool to be scared." But why did the brute whinny again, then snort at something she could not see?

This was silly, unutterably silly! Milton would laugh at her when he got here and she told him how afraid she had been to enter the house where she was born. The lock grated protestingly, clicked over. Lucky she had kept that key all these months.

The door opened under the push of her icy hand. Except for a filming of dust the hall was just as she remembered it with its antlered hat rack and the slender, graceful curve of the banisters where the stairs lifted to obscurity above. Light still filtered in dimly through the arched opening from the parlor, spreading ebony shadows on worn Brussels carpeting. Queer shadows! That one for instance, long and angular as if it were thrown by a horizontal box resting on trestles...

Grisly fingers squeezed Emma's heart. Three years ago just such a shadow lay here, and in the parlor Granddad Sprool had been stiff in the coffin by which it was cast. This was the shadow of a coffin—and the sickeningly sweet odor of funeral flowers was heavy in her nostrils!

No! Gram was buried, buried! They wouldn't have kept her here, untended, for the two weeks since she had died! It was just a trick of light and her own taut nerves?

That dark silhouette tapered slightly, just as Granddad's casket had, but it was smaller. Gram had always been shorter than Granddad and the years had shrunk her. Emma licked dry lips, and knew that she must get to the parlor door, that she must look to see what made that shadow. But her legs wouldn't move...

She got them going at last... It was as if the dusty air had suddenly grown thick, viscous, so that she had to push through it with all her strength. She reached the threshold at last, held onto the lintel and pulled herself into the musty parlor. The windows were grey rectangles in the faded wall; under her feet the floor seemed to heave, like the swelling sea. Emma whimpered, far back in her throat. The coffin was there—an ominous bulk in the gloom...

ONCE started toward it she could not stop. She was close to the thing. She was looking down into it, where the half-lid had been removed—looking down at Gram's closed eyes and the almost transparent hands crossed on a bosom of black silk that was terribly still. The old woman's skin was drawn tight over her fleshless bones, so tight that a skull seemed to answer Emma's gaze... They had edged the corpse-dress with a white neck-ruching. And that brown streak across its starched stiffness was the trail of a slimy, crawling thing...

The girl swayed, grabbed at the casket-edge to keep herself from falling. Something gritty crumbled under her hand—earth! Mud had caked the sides and top of the black box, had dried there. And here were the gouged places where the ropes had rubbed that had let the coffin down into a grave where it had not stayed...

A scream sliced through the walls of the house! Another, compact with ineffable terror. Outside, wood splintered, crashed. Across a window's oblong reared the head and shoulders of Emma's horse. A gate-picket dangled from its bridle and banged crazily against flailing forelegs. The brute screamed once more, plunged down and out of view. Galloping hoofs pounded away.

Not knowing she had moved, the girl was across the room, was staring out. A dust cloud thundered down the road, stopped suddenly. The horse reared out of it, whirled in a strange dervish dance. In the eerie half-light a grey, shapeless something clung to the beast's belly, reached grey tendrils for its foam-flecked, out-straining throat. Then the frantic animal was gone around a bend. Only the diminuendo of its pudding hoofs and the shrill panic of its almost human screams were left, coming back to Emma through quivering, affrighted dusk...

Moments later, as night welled up the towering slopes, the girl still stood motionless, flattened against the window as that last awful glimpse had left her. She was poignantly conscious of the preternaturally disinterred corpse behind her, but nightmare paralysis held her rigid and her larynx was sore, rasped by unuttered screams. The faceless Things of the hills had come down into the valley at last, into the precincts of her ancestral home. The drear dread of the mountains was a living, tangible presence in this house where she and the man she loved had hoped to find refuge from a world that had denied them. It was here, here in this room. She felt its chill fingers stroking her spine, its icy breath on her neck. Something was here, something that had brought Gram back from the grave, something that itself had come from that mountainside burial ground!

The vague clatter of hoof-beats impinged on her consciousness. Emma lifted burning eyes to Big Tom's rocky summit across the valley, to the pale ribbon glimmering along his darkening flank. That was the new highway, she remembered, the recently opened macadam trail Milt had pointed out on the map as the way he would come when he had finished the business that delayed him. And on it, miles away, the failing light picked out a tiny moving horse—her horse. Somehow, even across the space between, the girl sensed the incarnate terror flogging that anguished beast, flogging him to insane flight from the horror that clung beneath his belly and fled with him.

The distance-dwarfed steed staggered, fell. A final shrill neigh split the awed hush of the mountain-encompassed hollow. Horrible movement animated the prostrate beast; greyness flowed over it, merged it with the grey road. The pallid mound heaved, sickeningly, for long moments. Then the ash-tinted destroyer ebbed slowly from its victim, slithered into bordering trees. A tawny shape was very still as the up-surge of night's sightlessness engulfed it, and the highway, and the trees into which horror had seethed.

It was as if Satan had set a vaulted black lid over the valley to hide it from God's sight. There was no light in the sky, utterly no light in the broad sweep of the dale. No sound except a faint rustle of wind in the forest cloaking the mountain-sides.

Or was it the wind in the leaves? Grisly fingers plucked Emma's quivering nerves to new apprehension. Was it not rather the slithering advance of the wan hosts that so long had danced as pale, mist-like wraiths on the twilight slopes, unleashed at last to their long-deferred invasion of the lowlands? Loosed by Gram's passing, perhaps; by the death of the pioneer's spouse who first had intruded into this valley and driven them back into the hills... Was that why Faith Sprool had been brought back here from the sanctuary of consecrated ground, that in death they might wreak on her a weird vengeance for the thralldom to which her life had condemned them?...

Oh God! Oh good God! Emma's fingers twisted, interlacing, and her slender frame was a shell brimful with terror. The advancing sound was no longer a dim, just hearable rustle. It was a thrum pulsing toward her, a swift-coming burr momentarily louder. They were coming fast now. Faster. They were coming for her!

Of course for her! She was a Sprool, the last of the Sprools, and she did not know the secret Granddad and Gram had had that held Them back. She had always suspected there was a secret Granddad knew, the haughty patrician in whose leathery visage steely eyes brooded and who held himself and his family so high above the valley-folk. But she had never dreamed that this was it. Why hadn't they told her how to drive back the eerie company sweeping down on her?

A green light-beam scythed the darkness out there, struck the road into livid relief. Vague forms seemed to dart for concealment in the thick bushes of the garden... A gigantic grey shape roared around the road-bend, skidded to a halt. The menacing thrum throttled down to the familiar throb of a motor, and a remembered profile was limned by dim dash-lights.

"Kurt," Emma called. "Kurt!" The name was a sob in her throat as she shot into the hall. She was across the verandah, and running through the garden. "Kurt Tradin!" Briars snatched at her, murky foliage; a low-hanging tendril whipped stingingly across her cheek and some furtive thing scuttered out of her path. "Don't go away, Kurt. Don't."

SHE had reached the car, was clutching its sill with both hands. Gaunt-visaged, somehow older than when he had laid suit to her in the shy manner of a country swain, Kurt Tradin peered at her. His slow smile was tinged with some strange apprehension. "Em. Emma Sprool! Be you all right?"

"Yes—Kurt, why isn't Gram buried?"

"Why what? He half-rose from his seat, shoving toward her. "She was! I see her laid to rest myself, in the graveyard."

Emma's last faint hope vanished. Her nails dug into the auto's steel, her throat worked. Then—"But she isn't. She's in there, in the parlor."

Kurt's lips were ashen. From above the lumping of his high cheekbones wormlike lights crawled in the depths of his shy eyes. "In—the parlor," he husked. "Almighty Godfrey! They knew ye was a-comin', then! Christopher, I'm glad I come out to see if you was here, like I done every dusk the past week."

"In God's name! Kurt! What is going on here?" Kurt's stalwart frame, his big-boned, handsome countenance, wavered in Emma's vision as though a heat-haze screened them. "Who—what knew I was coming?"

The young farmer seemed to have difficulty in forming words; his gnarled hand was trembling. "We—don't know. Whut-ever it is thet's been prowlin' the nights since yer gran-maw was buried. Grey things in the hills thet ain't shaped like man nor beast."

"Grey things!" Emma thought of the anguished horse and the thing that, hanging beneath its belly, had reached gruesome tentacles for its throat. "I saw one! It killed my horse, out here?"

"Yer hoss!" He rapped the syllables out, and a little muscle twitched, once, in his cheek. "They've killed more nor hosses—Gaffer Wilson, an' Ely Trenholm's Iry an' Alice, an' Spad Perkins' hull family when they tried ter get out along Big Tom Highway. Thet's why I bin watchin' fer you to warn you not to stir out o' the house after sundown."

Emma did not hear that last sentence. "Big-Tom Highway—Kurt! Are they—is there any danger on that road?"

He laughed shortly, without humor. "Danger! Thet's whar they was first seen—an' thar ain't ary one got through thar by night fer three days. Spad's outfit was the last ter try. Jed Harker an' me found what was left o' them." Horror flaring in his eyes spoke volumes. "The car wasn't hurt aytall 'cept'n the gas tank was ripped open? We buried 'em quick, an'—" Once more a hesitant, quivering pause. "An' found their graves open the next mornin', open an' empty."

The girl swayed. Her lips parted, but no word came from them. Kurt's smoldering gaze was fixed on her, and his voice was a hoarse croak. "No one's come in or out of Ekwanok by night, since then. Not by night... Though by day thar's been plenty agoin' till thar ain't but a half-dozen families left in the valley... Whoa up, Emmy!" He seemed to notice the girl's state for the first time, grabbed for her wrist just in time to keep her from sliding to the ground as her knees gave way. "What...?"

Emma squeezed speech through her tight throat. "That's the way Milton is coming—maybe tonight."

"Milton?"

"My husband." She recalled that his letter had been addressed to Emma Sprool. "I'm married. Kurt. We had given up our room, had the car packed and ready to start for here, when someone sent for him to audit an account. It meant twenty dollars, the first in months; he couldn't turn it down. It was cheaper than a hotel for me to come by rail to Kingville. No one would drive me here, but I borrowed a horse. Milt said he would leave as soon as he finished—perhaps tonight. Tonight! And he is coming by Big Tom Highway!"

"Your—husband..." The syllables dripped from Tradin's twisting mouth; evidently he had heard nothing else. "Husband." Life drained from his broad-sculptured visage; his eyes were dead things, and his upper lip trembled like a hurt child's. His shoulders slumped. There was something abject about his big frame. Emma had seen him thus once before, when old Jeremiah, her grandfather, had flayed with cutting words the yokel who had aspired to mate with a daughter of the Sprools. "I—Great Jumpin' Godfrey!

Someone had screamed, far down the road. Some thing—for there had been nothing' human about that high-pitched wail of agony. The girl twisted to it, her heart pounding to the anguish, the utter terror in that cry—and it came again. Tradin's hand was on her shoulder, was shoving her away. "Git in th' house, Emmy. Git inside an' keep the door locked."

She jerked away. "But you, Kurt. You..." His face was set, his sleepless eyes ablaze, "Come with me and—"

"Can't," he snapped through tight, white lips. "I—maybe I'll get 'em this time. All week I've been too late. But thet warn't fur away..." Motor roar drowned his voice—faded to let him shout, "Quick, Em. Git inside an' let me go"

His urgency got her started; panic spurred her, and she was hurtling through tangled brush that ripped and fought to hold her back. Her feet thumped on the creaking porch. As the door pushed open before her frantic rush she heard the farmer's car dart away. She slammed the portal. Musty dark swallowed her as she fumbled for, and found, the great bolt and shot it rattling into its socket.

THE mutter of the speeding car died in the distance. Emma moaned. A pulse throbbed in her temple and a steel band constricted her chest. She was alone in the blackness. Outside an unnamable doom prowled, and here within was the cadaver that earth and the worms had rejected. She was not alone! Livid, marrow-melting fear companioned her, breathed on her its icy breath. To stay in this house were to face a hell of terror, to flee into that outer dark peopled by the grey menace a prospect unthinkable. A spasm twisted her slender body and her small fists beat against the door-panel in frantic protest. Why had he let her come here alone? Why had Milton...

New terror clamped grisly fingers at her throat. Milton might even now be climbing the pass, might be entering unwarned the macadam snaking along Big Tom's flank where the grey Things waited. "No! He's still working. Oh, God! Please make him still be working. Please let me phone him not to come." Phone! The telephone was in the parlor; she would have to brush close by the gaunt, terrible casket to get to it!

The girl whimpered as she pushed herself away from the wall. To save her own life she could not have entered that sepulchral chamber, but for Milton—for the man she loved!...

Straight through sightless blackness Emma strode, across the hall, into that fearsome chamber so strangely a sepulcher. Unseen, unseeable entities slid soundlessly from her advance, gathered behind in watching balefulness. The coffin-edge scraped her side to ripple her flesh with crawling revulsion. She sensed the wall before her, groped for the box of the rural phone, the tiny handle of the magneto. Gasped as the wire-whine in her ear told her the line had not yet been disconnected.

A startled man's voice grated in the receiver. "Almighty Godfrey, Mariar. Et's the Sprool house—" The Ekwanok exchange was in Elmer Barmes' kitchen. Then, "Who is—" A click snapped short Elmer's question, clogged the line-sound in Emma's ear...

"Hello," she panted. "Hello..." And knew that she was not heard. In that moment, in that very moment the wire had snapped, somewhere—or malevolently been broken! "Elmer!" the girl screamed, despairingly. "Elmer!..."

The receiver dropped from Emma's flaccid hand. She heard it thump against the wall, dully, heard the tiny rattle of dislodged plaster behind the laths. Her lips formed words they did not utter. "God—help me." God had turned his face from the valley, from her. But—but perhaps Milton would not come tonight. Perhaps his work would keep him so late that he would wait till morning.

She grasped at the faint hope, even knowing that his longing to rejoin her would drive him to complete with all possible speed the task that held him from her. This was their first separation since they had become man and wife—sometimes the fierceness of their love frightened her—and he would be eager to end it... No, at whatever hour he was free he would start out.

Maybe he had started, maybe he was there now, high up on Big Tom. Why had the phone connection been broken except to stop her very warning? But they wouldn't know about telephones, the pallid killers prowling the highway. Of course not. She laughed, but the short sound of her laugh was not pleasant. How silly she was. How silly. The rural wires often went out of commission...

A dim vibration crept to her ears through the darkness, a far-off thrum, the infinitely distant, sound of a coming car. Help was coming—Kurt was coming back to help her! He would take her to the village, to another telephone. Without seeming volition she was again at the window from which she had first glimpsed horror. She peered out, up the road toward Kingville whither Tradin's car had catapulted on its wild chase. Nothing save impenetrable dark.

But that vague burr of a speeding motor still sounded. It pulled her eyes up, up along what she could not see but knew was the slope of Big Tom, up to where the road must be where the horse had screamed and died. A star showed—but that tiny light was too low to be a star—and it was moving! It must be an auto headlight then, the light of an auto coming along Big Tom Highway...

The staring girl's hands closed on the window-sash at either side, while thought stopped and her skull was a void seared by the query she dared not think. Whose car? Oh dear Lord! Who drove that car?

The light split to two tiny specks. Some curve in that far-flung, high road sliced their beams to double dashes of yellow against the dark billow of foliage, one luminant streak canted upward and distinct from the other. Emma's hands clawed, raked down old wood, paint flaking and stabbing into the quick of nails that scraped it. She was answered. Oh merciless God, she was answered!

Those were the lights of Milton's roadster. Unmistakably. He had tugged at that up-bent lamp, trying to straighten it, only this morning...

"Milt!" she screamed. "Go back, Milt! Go back! If you love me, Milt, go back!" He could not hear, of course he could not hear. "Milt!" Why could he not hear? Why could he not sense her anguished soul shrieking its warning to him across the miles? "Milton!"

Steadily the twin beams moved across the vast screen of blackness. They seemed to be drifting infinitely slow, but Emma knew the speed at which they moved. A flash of inner vision showed her Milt's ascetic, dear face bent slightly forward over the wheel, the wind of his passage sweeping his hair back from his high, clear forehead, his brown eyes eager. He would be calculating the minutes still between them. His arms would be aching for the feel of her in their embrace. Her own breasts ached in answer... Dear Mother of Mercy, protect him!

His love was hurtling him on to doom!

Across the vast night that had engulfed the world those tiny lights floated with even pace. Hours seemed to pass and some dim hope stirred in Emma's aching bosom. Kurt was wrong. Perhaps Kurt was wrong. Perhaps the Things in their descent on the valley had relaxed their watch of the highway. Milton was getting through. He must get through. He would.

In minutes now he would reach the place where the horse had died—right there—he would reach and pass it. Of course he would pass it. That would be the test. If Milt passed that spot he would be all right. He would surge down the hill, down into this connecting road that ribboned before the house, would honk his horn for her and she would be at the gate, on his running-board, in his embrace. In seconds now she would know. In seconds. He was almost there. He was there. He would pass—

His lights were gone! In that instant, in that very instant when he had reached the spot where instinct had told her the greatest danger lurked, his motor had sputtered, stopped—and his headlights had blinked out as if a black shroud had dropped over them! As if a shroud—his shroud... The Things had him! The grey Things had swarmed over her husband, her lover...

It was then that madness first probed gruesome lingers into the girl's brain. Glass crashed as she smashed the window before her with flailing, frantic fists. Keen, jagged shards gashed her jacket, her arm, as she clambered through. She was out in the garden, was smashing through tangled, wild shrubbery she felt but could not see. She was across the road, had plunged into thick woods that lifted under her feet, lifted and became the high slope of Big Tom.

She was climbing that slope, blindly, climbing to the highway above. Climbing to Milton, to help him against the grey death. To die with him if he were dead. To die whatever horrible death he suffered. Or save him. That was it, she would save him. She would drive the grey Things away from her lover with the very fury of her love.

The sound of her wild passage was a tumult in the silent forest. She caromed off a black tree trunk, plunged on. A trailing vine coiled around her ankle, tripped her. She slammed down. In the moment she lay gasping something rustled the carpeting of dead leaves, close by. She pulled herself erect, staggered on. The woods tore at her, would not let her pass. Snarling, like some creature of the wild, she fought it, fought through.

The way grew steeper, sapped her strength. She was moving more slowly now, but would not stop. Rock-face rose sheer above her: she found hand-holds, niches for straining toes, inched upward. Her labored breathing, the scrape of her toes against the stone, were the only sounds she made.

But there was another sound in the woods, though she did not hear it. The stealthy sound of a furtive something that slithered through the underbrush...

Her reaching hand found dank earth at the brow of the cliff she climbed. She was up and over, lay panting on its very brink, face down over its edge where the air her laboring lungs needed was unimpeded. She pulled dampness into her aching thorax, fungus-smell, odor of rotting leaves. And another stench—alien, shuddersome—like nothing she had ever smelled. Infinitely menacing.

A patch in the blackness below was queerly lighter, somehow—a patch that moved to the base of the rock she had climbed. It was a pallid, formless shape that moved oddly, flowing like—like the greyness that had ebbed from a tawny still heap that had been a horse, like the grey horror-thing that had seeped into the woods—to wait for Milton. It was climbing now, climbing to reach her, grey-black tendrils reaching for her... Her breathing stopped and an abortive scream retched her throat, was a soundless gust...

She surged to her feet, and was blundering again through tight-laced undergrowth, through ripping brambles and whipping thin branches that lashed at her. Moist mold was slick under her feet: stones rolled, twisting her ankles. The forest was on the side of the noisomeness it had borne, was striving to hold her for that which pursued. God was against her—no, God had forgotten her, had forgotten Milton. God had abandoned them to Satan's spawn.

Emma crashed against an invisible tree-trunk, clung to it, momentarily stunned, saw the weird evil that followed her closer now. It seemed to move so slowly, yet it was closer. Terribly close. She was running again, fleeing the terror. Her clothing was in tatters, her white skin ripped and bleeding. Her body was an intolerable ache, her veins an icy network. But she climbed, climbed endlessly toward where the highway cut through primeval, lush timber, toward where Milton needed her. Milton! Good God! She was leading another of the creatures to him, she was bringing him not help but sure destruction!

The thought halted her, jerked her around to face that which she fled. If it took her, if she gave herself to it, would it be sated? Feeding on her would it be kept from joining the attack on Milt? There it was, an inexorable billow of menace, eddying effortlessly through the tangle that it had cost her so much to penetrate—coming for her with a strange quietude, certain of overtaking her, certain of its prey...

The darkness here was absolute, yet she could see it, see its vague greyness, like a faintly luminous small whirl of mist emanating from the very ground. Against its vague light gaunt boles were silhouetted, trunks springing straight to the sky or twisted by some injury to a frail seedling. By all that was holy, she recognized the grotesque knotting of one gnarled oak! She remembered wandering here in the woods as a child, finding an abandoned loggers' cabin near that U-shaped trunk... A cabin! Was it still there?

Emma twisted, sped away. Ten, a dozen steps and she saw it, a dark, welcome bulk, slab-sided. Saw it and felt a clammy cold touch on her back where jacket and blouse had been stripped away! Her body exploded into a long, terror-winged leap into the musty closeness of the long deserted shelter. Miraculously she found a door and slammed it shut against a soft, squashy bulk.

She heard the soft slither of groping tendrils against the wood, dug heels into the earthen floor and shoved aching, bare shoulders against the barrier to hold it against the sleazy surge of that which sought entrance. She felt the dig of a bar into her back, fumbled behind her and shoved it into a stout, angle iron riveted through the jamb. Then she slid, utterly spent, down along the splintered panel—lay, limp and gasping, at its base.

The fetor of the Thing threaded through still space, a putrescence of something rotting that initially was foul. The sound of its groping was doughy, horribly without stiffness. Clammy-cold as the slimy touch she still felt on her back where momentarily it had contacted her. Somehow blind—as though the sense by which it had trailed her had been not sight but an uncanny attribute of an entity from beyond the Pale. Sliding sound whispering of evil incarnate; livid, quivering evil.

What was that?

Dully, almost beneath the level of hearing, another sound had come out of the forest night, like the shout of a human voice, far off. The Thing must have heard it too, for now it was quiescent, suddenly unmoving. Utter stillness fell—to be shredded by a high, shrill wail that clawed Emma's quivering nerves with gelid talons of new and supernal terror.

The fearsome ululation rose, and died away. And then—realization pulled the girl up to a sitting posture, her icy hand at her frozen lips—that which had groped for entrance against the saving door of her refuge was gliding away. She could hear it—the rustle of its ungainly weight out there—then it was gone.

It was gone and she was safe. But who was it that had shouted, briefly? Who could it be but Milton? No other human was near enough to be heard. He was alive, still alive, crying for help! And the Thing had abandoned its efforts to get at her in response to the weird call of its mate! It was hastening, even now, to join in the attack on Milton.

Awful certainty pulled the staggering, half-naked girl to her feet... Somewhere out there in the gruesome night, her husband was in deadly peril. Somewhere out there—but where? Oh God! Where? The answer flashed on her. She had seen the cabin, where all else had been darkness, had seen it silhouetted against a narrow paling of the blackness. That lighter strip against the gloom could be only Big Tom Highway, the turnpike along which, she had seen Milton's lights drift and blink out, the road from which his cry for help had come. He was near—very near?

It was not Emma Wayne whose slow hand sought the great bar that locked that door against terror and shoved it back. It was the frenetic errantry of a woman whose loved one was in peril, the incomprehensible devotion of the female who would defy Lucifer himself for her mate...

Cold air was about her as the portal creaked open, the dank chill of the night still tainted by the fetor of corruption. She was out in the open, in an oppressive silence that held in its jetty womb muted sounds of a struggle: the heavy breathing of a strangling man; the thumping of tossed, heavy bodies, boneless and horrible.

Emma turned her head against neck-muscles that were taut, resistant bands, saw the pale glimmer of the road, yards away through the trees. Saw the familiar outlines of a cheap roadster against the wan light—and beside it, an amorphous mass that heaved sickeningly, heaved up, settled again!

"Milton!" she shrieked. "Milton!"

The formless, grey-luminant mound seemed to swirl, to break apart. A shape flicked into being at its center, an upsurging figure of a man. Emma glimpsed the pale oval of a face, heard the guttural mutter of a cry in what might have been Milton's voice. Then he was down again under the upheaval of the attackers...

Briars tore at her, unseen branches lashed at her. She was on the road, was leaping toward the struggling mass. She had reached it, was tearing at it with desperate hands, was tearing away handfuls of viscid, doughy stuff that stunk to high heaven. The stuff clung to her fingers, clogged them. Beneath the mound Milton choked and struggled.

A thick, gluey tentacle rose toward her, coiled around her waist. It was dragging her down, irresistibly down into that corruption. She beat at it and her fists smacked into wet, cold softness that gave like wet and sticky clay. She sank into the noisome mound. Its foulness was in her mouth, was clammy against her nostrils. She could not breathe...

Within the maelstrom that was her ego she whispered, "Milton. With you. In death as in life..."

Something screamed through the darkness that swept into her brain...

IT ISN'T right, Emma thought petulantly. When you're dead you ought to stop hurting. It was as if she were still in that body of hers that glass and the forest brambles had sliced. Pain seared her everywhere, and her chest was an aching hollow.

"Emma! Darling!" Milton's voice cried from out the depths. "Emma!"

It was all right then; he was in the same place to which she had gone. They would be together through eternity. Something stroked her forehead—it was his trembling hands. Even here they thrilled her. Would the sight of him thrill her too? Emma dared to look.

A green light bathed him, and his face was contorted, anxious. "Milt, dear," she said weakly. "Don't look so worried. Nothing can happen any more."

"Oh God! Oh thank God! You're alive! I thought..."

The girl's lips moved weakly. "Alive? Oh Milt?"

His kisses were cold on her mouth, icy cold. The grey stuff streaking his cheeks was clammy against her.

Another voice said gruffly, from somewhere in the eerie light, "Come on. Let's get out of here 'fore them Things come back."

Past Milton's shoulder she saw Kurt Tradin standing over them, ashen-visaged, gun in hand, looking fearfully into tall shadows enclosing his headlight beam. And Milt had a gun. Matters became real again. She was alive. She was lying in the dust of Big Tom Highway, and her husband was kneeling beside her, holding her in his arms, kissing her.

She pulled away from him. "What—what happened?"

"God, Em, I'm not sure I know. I was pounding along, saw a dead horse right across the road. Braked and got out to pull it out of the way—then my car lights went out and something jumped me from the trees." He pulled an arm across his sweat-wet, white brow, and shuddered. "Something out of a nightmare. It had me down, was smothering me, but I got my senses back in time to fight it off. To try to fight it off. I couldn't get away from it. But it couldn't quite down me either. I think I fought it for hours.

"Suddenly it yelled and another like it lumbered out of the woods. The two ganged up on me and had me down. I was all through when I heard you scream. That was like a jab from a red-hot iron. I pulled away from them for a second, saw you coming, and then they flooded over me again. But I knew I had to lick them then.

"For some reason one of them let go. I pounded at the other. I must have found some vital spot, for the Thing screamed, squirmed away from me. I got to my car, grabbed a gun from the side-pocket, and turned to see both of them vanishing into the woods. You were lying here, more dead than alive. I started for you when there was the screech of a horn, and this gentleman came ripping around the curve."

"This is Kurt Tradin, Milt," Emma said then, dazedly. "I've told you about him. This is my husband, Kurt."

Tradin was strangely expressionless as he turned to her. "Reckoned so. You two agoin' to stay here till the critters come back? Ain't you had enough?" His tone was flat, dead, but little lights crawled in his eyes. Was it fear?

"Right you are." Milt lifted Emma, carrying her up with him in his strong arms. "Let's get going, friend."

He started with her toward the battered flivver.

"Better if we stick together," Kurt rumbled, not looking at them. "Take mine, it's faster. We'll come back an' get your'n in the mornin'—if we live to see the sun again."

Milt hesitated. "What do you mean?" he said sharply. "Why shouldn't we live?..."

The farmer whirled to him, his face livid. "Jumpin' Jehoshaphat, ain't you seen enough to know the hand of Beelzebub is heavy on the valley? We're marked for damnation, all of us." His voice broke to shrillness. "An' only the Lord's miracle kin save us. Get her in my car, if you love her. Quick!" His arm jerked so that his revolver was pointblank at Milt's midriff. "Quick! I ain't agoin' to risk my neck for your foolishness."

Wayne shrugged and slid his wife into the back of Tradin's grey limousine, came in alongside her. Kurt leaped for the front, was under the steering wheel. His motor roared, gears clashed, and the forest's dark loom whizzed by.

A vast weariness gripped Emma. She snuggled close against her husband, immersed herself in his strength, the comforting aura of his protection. She had him back. That was all that mattered. She had him safe and with tomorrow's light they would leave here, leave Ekwanok and its valley of dread...

Out there was still the night to get through. The dreadful night. "Where are we going, Kurt? Where are you taking us?"

"To yer own house, quick's we kin get there."

Emma pushed up. "No, Kurt," she groaned. "No!" She was quivering once more with the fear that first had found her there. "That's where the Things..."

"Safest place in the valley," he growled, cutting her short. "Worse in the village."

"But—"

"But nothin'. You'll see." Grimly. "We go through the village."

"What's the matter with the Sprool house, Emma?" Milton interrupted, curiously. "I thought—"

"It's horrible, Milt. Gram's—"

"God! Look at that! The place is on fire!"

The road had dipped, suddenly, and debouched between dark, shuttered houses that were gaunt against a lurid glow from which dancing sparks flew straight upward.

"No," Kurt grunted. "Not th' place." And they were darting through the green Emma remembered as bordered by the staid facades of churches, the white columns of the town hall. But the open space was staid no longer. Great leaping red tongues of a huge bonfire soared avidly from its very center, and, limned grotesquely against it, a ring of prancing, black figures hopped, and gibbered, and howled in wild antics. She quivered in revulsion at what a tall, bearded man was doing. Distracted momentarily by their passing, he turned—and wild eyes glared at them from a face she knew. The incredible scene whipped behind them...

"Kurt," she gulped. "Kurt. That wasn't Dr. Potter. He couldn't—"

"Yep," laconically. "Preacher o' th' First Presbyterian. That's Ekwanok, Em, all that's left. Want to stay there tonight?"

She shuddered. "No. Mother to mercy, no!"

They curved around the jut of Big Tom; the village of the mad was behind. A bridge rattled under their pounding wheels. The car swayed, jounced as the macadam ended. Kurt's green headlight stabbed through darkness again, darkness that blanketed grey terror, but Emma welcomed it. Even the horror of the skulking Things were better than that which she had just glimpsed.

"All them that's sane has went, a week ago," he said.

"All but you, Kurt. Why did you stay?"

"I was waitin' for you," he answered simply. "For you." There was bitter despair in his tone. "You forgot what I promised, but I didn't"

"Oh Kurt!" Emma remembered now the one stolen moment she had given him to say good-bye, their one brief talk after grandfather had forbidden them to see one another. "You'll come back, Emmy," he had said. "Sure's shootin'. An' I'll be awaitin' for you." How could she have forgotten the dreary hopelessness with which he had thrown out his hands, and the dogged determination in his hurt eyes.

"I'm sorry, Kurt," she said. She had really thought herself in love with him, till she had met Milton and learned what love was.

"You shouldn't have risked it," she added.

"Risked!" Still that dulled bitterness. "I belong with them."

"Isn't that the place?" Milton broke in. "There to the left?"

Breath popped from Tradin's tight lips. "Yes." He braked, swerved. His radiator crashed through the broken fence, the car skidded through the garden, nosed the porch and stopped. "Git out an' into the house. Hurry!"

Kurt's urgency lifted them out of their seats, out of the car, and to the door. Milt shoved it open, but Emma turned.

"Kurt," she called. "Kurt! Aren't you coming in?"

"No." He was already in reverse, was surging backward. "Git inside for God's sake."

He was in the road—was gone. Milton's grip was on her wrist, pulling her inside. The door banged shut, and a flashlight beam sprayed the gloom. But for an instant, the girl's mind was tangled with a strange gesture the farmer had just made, a gesture as of final farewell.

"Creepy old place—no wonder you left it." Her husband's voice was unaccustomedly loud and harsh. She jerked to him, reproach on her lips. "Remember where there's a lamp? We've got to have light."

She saw his face dimly. It was infinitely weary, haggard. There were black rings under his eyes. She choked back what she had been about to say realizing the tension he was under. He was as afraid as she, was dissembling, trying to be natural, in order to quiet her. His hand, behind him, had already slipped the door bolt into its socket, and the long whiteness of his flash-beam flickered everywhere, probing the shadows. "There should be one on a table behind the stairs." The light darted there. "Yes—and it's filled."

"Here's some matches. I don't know how to work the thing." He poked the paper folder at her, fumbled it into her hand. But he kept close beside her as blue flame ran around the lampwick, guttered, lifted to a steady glow within the replaced chimney. Yellow luminance shoved back the shadows, Milt clicked off his flashlight, managed a wan grin. "That's better. So this is the Sprool mansion!"

Looking with his eyes Emma saw the curious old-fashionedness of the house, even here in the hall, its threadbare assumption of a dignity it had long lost. In Ekwanok they had always called it The Mansion, had kowtowed to its inmates, even when the patriarch had gone. Kurt had been no exception. His love-making had been a shy, timorous, hopeless yearning for something above him.

"This is the Sprool homestead," Emma assented gravely, while her glance slid to the parlor archway, tried to penetrate its blackness, "where your wife was born and bred."

"What is it?" His exclamation was like ripping silk. "What are you scared of, in there?" He had seen her look, had interpreted it with the sureness of their intimacy. "What's in there?"

"Nothing. Nothing that I'm afraid of." Two could play at that game. "Gram's in there, in her coffin. They—they didn't bury her."

"Good Lord! What were they waiting for? I never heard of—" He started toward the doorway. Emma got her hand on his arm, stopped him.

"Wait," she said. "Time enough in the morning. She—I—don't go in there. Don't!"

He gripped her shoulder, turned her to him, gently, but she winced as pain stabbed down her arm. "Em. You're trembling all over. You are afraid of something in there."

She made her eyes meet his, forced false frankness into them. "There's nothing in the parlor except Gram's Coffin, with her in it. I—I don't want you to go in there because I couldn't go with you. I couldn't bear it, and I am afraid to be alone. Hasn't there been enough to make me tremble, tonight?"

"Poor kid! I'll say there has." The harshness of his tone mellowed, she was close against him and his mouth had found hers. The rasp of his tightening arms on her lacerated, bare shoulders was somehow sweet and she felt his fear-cold lips grow warm, then burn, as the tight embrace fanned the spark of their love to consuming flame. Terror was forgotten in that long moment, fear ceased to brood. There was only the ecstasy of their oneness...

A soft thud behind froze her, the drag of a jell-like mass across wood! Milt pushed her away, crouched, his eyes on the murky entrance into the parlor, his automatic tight-gripped, snouting. Syllables slid from his mouth that was suddenly a straight gash across a humid mask. "Watch it, Em! There's someone in there and I'm going in after him."

THE slow slither within the parlor that was a cavern of dread stopped, but Emma's spine prickled to the sensation of a baleful glare from the room's mystery, of fearful eyes glaring as the new menace crouched to match Milt's taut crouch and waited in ambush for his coming.

"No," she squeezed through the invisible fingers of fear clamping her throat. "No. There can't be. There can't..."

Then she remembered the window she had smashed, the gap in their defenses! "Don't Milt. Don't go in there. Please, Milt, don't!"

His eyes flicked to her, flicked back to stare ahead, but she had seen into their lurid depths and was aghast. Milt! No! It couldn't be her Milt's eyes into which she had looked in that revealing instant! His upper lip lifted in a vulpine snarl. He shrugged closer to the ground, lunged into the blackness, leaving behind a low growl, the growl of an enraged dog. Leaving behind a woman whose world had smashed about her bloody head, a woman shaken to the very foundations of her being, utterly alone.

Shot-crash pounded dully to Emma's clogged ears; her dizzy sight was aware only of an orange-red flash that illumined nothing. Muted sounds of a terrific struggle were suddenly cut short, were succeeded by an awesome silence, a silence pregnant with queasy dread. There were furtive noises, sluggish movement, a whispering frou-frou of satin. And again the slow dragging of something that was neither human nor beast. Then stillness again, a stillness as ebony dark as the blackness veiling whatever horror had come to pass in there.

The girl came gradually to awareness that she was clinging to the banisters, waist-high just there, that grave-chill stiffened her limbs and corpse-smell was foul in her nostrils.

"No." she whispered. "Dear God. No."

There was no sound, sepulchrally no sound from the murk ahead. She was mistaken in what she had read in Milton's final flickering glace. She must have been mistaken. Of course she had been. The hands she unclasped from the slender round of the banister-rods seemed to creak, their joints paining. She must go in there. She must go in there to see what had happened to him. What had the Thing done to Milton, to her lover?

Her lover! She recalled the look in his eyes, and shuddered. Was she going mad or...? But she must stop thinking. She had stopped thinking, except just enough to pick up the lamp and make her legs take her toward that parlor door.

The lamplight seemed tangibly to push back a wall of darkness that resisted it. To push back something hidden by the darkness, hidden by and eerily part of it. She was through the archway and the lamp's luminance filled the room, thrusting the darkness out through the gaping, jagged-edge window into the night from which it came. Thrusting the Thing the darkness hid—not thrusting all of it! In mid-air a shadow floated, unmoving...

It was no shadow, it was the coffin, the black casket so weirdly exhumed. The macabre object pulled Emma's look to it, pulled with a shuddersome fascination she could not resist. It seemed to have a message for her, a message of doom.

She fought the gruesome drag, drove searching eyes about the musty chamber, over age-patinaed furnishings long-familiar yet uncannily strange, into far corners, along the scrub-whitened floor islanded by the faded rag rugs Gram's fragile hands had worked. Stiff and decorous the parlor was as ever—empty, stark, staringly empty. Glass splinters still in the broken window were edged with grey stuff. But where was Milton? Oh God! Oh merciless God! Where was Milton?

Was that the message Gram had for her? Would she tell, her old grandmother, stiff and dead in the casket They had not let rest? Gram would help her in her agony. Gram, always so fluttering-kind despite her tight-lipped grimness. She would go and ask Gram where Milton was.

Emma's feet whispered across the floor, and her light grew stronger on the casket, grew stronger and yet somehow was swallowed by the dull black of its grave-smeared sides. Emma was at the coffin side, but her eyes had jerked themselves closed as she reached it. Why did she fear to look into the box where lay all that was mortal of Faith Sprool? Why did she fear to look, save for dread of the message she was strangely aware it held for her?

She—must—know! Still with shut eyes the girl lifted the lamp, so that its rays would strike down, would strike surely down into the uncovered coffin. So. Now she could take one swift look and turn away. Now!

The face that stared sightlessly up at her from the coffin pillow was not Gram's face. Not Gram's! Emma was a statue of stone, gazing down at a drawn, thin-visage, well-conned but somehow utterly strange. It was Milton, Milton whose corpse-hued countenance lay on the white satin. Milton!

Numbed, unbelieving minutes passed. Then the full horror reached her brain, and a scream ripped from her inmost being, shuddered out of that ghastly room, shrieked across the valley and was lost among the night-shrouded trees. Another.

The echoes of those screams were mangled by the mountain-side, were metamorphosed into a shrill laugh. The mountains were laughing at her, the mountains whose lifelong threat had come at length to full fruition. Big Tom was laughing at her...

Emma was laughing too. Shrilly, unendingly. Laughing from a wide-open mouth that drooled, from a body contorted into a backward, spasm-twisted arc. Laughing while icy tears rolled down her face that was a network of tiny, quivering muscles, splashed from a little chin blurred by its tremors, wet a blood-wealed bosom racked by awful sobbing.

Even the stars might have pitied her, in that moment, had they not been shut out from the valley by the lid Lucifer had clamped over it. Even the madmen who danced about the red bonfire in the hidden village, had they heard her.

But there was none here to pity her. None in the desolate house save he who lay so ghastly still, cramped in a box for the dead that was too small for him, and could not hear her laughter or her sobbing for him, for her lover?

Suddenly Emma's crazed laughter shut off, and her sobbing. Quite suddenly as if some grisly hand had twisted a streaming faucet shut. A crafty light crept into her eyes, and the tense rigidity that gripped her body relaxed. The glance she shot around that room was furtive; her free hand came up to her mouth and her forefinger pressed against her lips with sly cunning. She tiptoed out of the parlor, reached the hall, turned to the left where the light of her lamp fell on another door. She was through that door. It closed soundlessly and she was slinking with grotesque noiselessness through a huge room walled with dark oak. A massive table gleamed dully. Round plates were parti-colored circles on Dutch shelving high up. The slinking girl mumbled something inaudible, crossed to the gloomy loom of a carved buffet. The slide of drawer was a barely audible hiss as she pulled it out and fumbled within...

She was returning now, and there was a knife in her hand—a long carving knife whose steel flashed brightly, whose edge was razor-keen. She reached the door, paused irresolutely, looked helplessly from her hand that held the lamp to that which gripped the knife, mumbled again. How to turn the doorknob? She nodded as the solution came to her, set the lamp down on the floor.

They built well in the old days, and Jeremiah Sprool was exacting. No gleam came through the door Emma had closed behind her to shut off light from the forgotten lamp, no gleam at all. Utter, darkness was around her as she moved with the silent sure-footedness of long usage. Utter darkness—in the hall, in the parlor—and in her mind.

After a while there was no sound, no slightest movement in the ancient structure that once was so proud to house the Sprools.

On the porch running across the front of the Sprool Mansion a board creaked to the pressure of a cautious foot. A figure, silhouetted against the one bright window, froze to immobility. Nothing but that oblong of light indicated that the house was anything but a shell enclosing only death. The prowler moved again. Faint clink of metal against metal was quickly hushed, well-oiled hinges made no sound, and the porch was once more vacant.

In the foyer of the years-worn dwelling the tomb-like odor of rotted flowers lay heavily, brooding its conquest. But another scent trailed across that corruption, the warm, charnel taint of fresh blood. The intruder sighed, and infinite weariness was in the brief, quivering exhalation.

"Em," he called in a hushed tone. "Emmy. Whar are ye?" A pause, broken by no answering voice. Then, more sharply, "Emmy Sprool. Don't be afraid. Et's Kurt. Kurt Tradin."

Still no response. Breath hissed from between tightened teeth. Groping feet shuffled, the knob of the dining-room door rattled sharply to the touch of a seeking hand, rattled again as it turned. A vertical bar of light leaped into being, blotted by the farmer's stalwart form. Alarm was in his voice now. "Em—Jehoshaphat!"

The exclamation was wrenched from him as movement thudded, from behind him, from the vaulted dark of the parlor. He whirled—to see a white figure leaping at him, to see a face distorted, glaring eyes, gleaming blade of a knife arcing at him. His arm jerked up before his face, took the slash of the blow, spurted blood. The girl avoided the clutch of his other hand, slashed again. Missed. Laughed shrilly, so that Kurt's flesh crawled. Bored in again.

His teeth gritted. God! He struck at her. She was a wraith, flitting away, out of the beam slitting through the dining-room door. She was somewhere in the dark; the sound of her mad laughter came from everywhere, from nowhere. She leaped at him from the dark, her knife sliced his cheek. He flailed at her, his fist found its mark of soft flesh. And she laughed again. Horribly.

She was gone again in blackness. He followed, reaching out for her, trying to find her. "Emmy. Girl. Whar are ye?"

Cold wind swept in, chilling him. And the great door slammed. Tradin was at it, was wrenching it open. Somewhere out there she crashed through brush, laughing.

"Emmy! Et's out thar! Come back. For God's sake, come back!"

Emma Wayne was crashing through underbrush that ripped her, tore her almost nude body. There was something in her hand—a knife it felt like—a knife whose hilt was slippery with—Oh God!—with viscid, warm blood. An instant ago she had been standing over Gram's coffin, looking down into it, seeing Milt's dead and ghastly face where Gram's should have been.

How had she come here? Why was she running? From what? Why was she laughing—merciful Heavens—why was she laughing so shrilly? Her hand went to her throat, pressed. Pressed the laughter to an end. But she was still running, blindly. There! Now she was standing still, in the dark that was so black it oppressed her, standing still in the frightening night.

Fear was back on her like a flood. Fear of herself, of the creature that dimly she knew she had been—for how long? Fear of the dark. Fear of the madness that stalked the dark. Fear of the Things, the grey and grisly Things to whom the night belonged!

They were here, out here somewhere, and she was out with them! In the house, at least, they could not get at her. Could they not? What was it then that Milton had fought in the lightless parlor? What was it that had killed him, had crammed him into the casket? That had been her fault. Hers. Because she had forgotten the smashed window. But she had waited for It to come back, had—Now what made her think that? The bloody knife? Whose blood was it?

"Emmy." A far-off voice was calling her. "Come back. Emmy."

She turned to the call. She was high up on the mountain-side. Down there, where the voice came from, a dimly yellow rectangle must be the door of the house. It framed a dark, familiar figure. Kurt's. Kurt—dear Kurt had come back to help her, was looking for her. She must go back to him. Quickly.

But she couldn't go quickly. The brambles were thick here, would not let her pass. She was sheathed in pain, every flick of a leaf against her torn flesh was agony. The scrape of rough bark, the tearing of thorns were sheer, exquisite torture. She whimpered with pain, with grief, with the fear that was growing on her again after the momentary relief that had come to her with her glimpse of Kurt Tradin's stalwart form. Every lumping of shadow in the blackness about her was a new threat, every minuscule rustle a new terror. She was on the hillside sloping down from Big Tom's mighty flank, in the thicket where the Things roamed. The grey and grisly Things whose touch was fearful death.

Why didn't Kurt come for her? Why did he stand there, motionless, peering into the night?—But he didn't know she was there, she hadn't answered his call. Her larynx swelled to cry out, her throat rasped with the coming sound.

And clamped on it, choking it back, as there arose before her, right before her, the same shrill, unearthly wail that had summoned the Thing from her cabin refuge to join in the lethal attack on Milt. High, and higher; knife-edged with appalling menace; glutinous somehow despite its shrillness, as though the ululation were being forced through some awful viscidness; it soared—and checked. Checked as earth pounded, as underbrush surged away and monstrous greyness lunged at her out of the night.

EMMA screamed, slashed at the Thing with her knife. Instinctively. The blade felt something, something that took its stroke with a queasy softness like no animal, no human flesh; only barely resisting the plunge of the steel. The girl's arm jerked hack for another blow, the knife soughed as it came out of its unreal billet. She slashed again. The Thing towered above her. It was falling on her reckless of her desperate stabs, was overwhelming her with its doughy, putrid mass. She went down under its nauseating bulk. Its noisome lump flowed shudderingly over her, pressing clammy, wet coldness into her nostrils, her mouth, into the hollow between her breasts.

This foulness wasn't real, couldn't be real. She couldn't breathe, couldn't see, but primal instinct—for life, primal clinging to existence, sparked her muscles with a furious supernatural energy. She heaved herself up against the noisomeness, drove her fists and her knees into it. It gave. Horribly it gave and as her back arched in a spasmodic attempt to throw it off it flowed underneath, so that its damp and gruesome chill slimed every inch of her frantic body. Even in that moment, even in the red fury of her hopeless battle, her skin crawled with revulsion and her stomach retched.

The boneless, formless Thing held her clamped in its foul embrace, investing her with its corruption, making her a part of its putrescence. Her lungs pulled, pulled, and could get no air. Searing pain racked her chest. The clayey mass that had swallowed her tightened, tightened an inexorable, crushing band about her threshing body. Anguish burst in her darkened brain, exploded into a blaze of coruscating flame. Yellow pinwheels whirled against velvety black, green meteors darted across their swirl, purple rockets burst and blazed. Burst...

The Thing shrieked, and suddenly let go its hold, so that she slid down, down, into swirling oblivion. Somewhere in vast blackness a tiny glow was an infinitely distant pinpoint. It grew, and as it grew its hard glow faded till it was the phantasmal, pallid, sleeping face of her lost mate. Of Milton! Its eyes opened, and Emma shrieked soundlessly as she saw in those eyes that look, that darting, awful look with which he had left her, to die. Her scream changed the bodiless head so that it wore Kurt's face, drawn, haggard, with bloodshot, sleepless eyes deep-sunk in chasms of weariness. She could not see his body, but she could feel his toil-roughened hand on her shoulder, dragging her out of the fathomless pit into which she had fallen. She could hear his voice too, his muffled voice, calling her.

"Emmy. Emmy. Come back."

Why—didn't he leave her alone—in death? She had been safe then. She had been rid of horror, of nameless terror, of pain. Of PAIN. Of the agony that now scraped her skin with fire; clawed her chest, her entrails. Of anguished knowledge that Milton was jammed, wax-envisaged, into a coffin too small for him. Of the memory of what she had seen in her lover's eyes. Now it was all back. All! God! Why wasn't she dead? Why didn't he let her die?

"Emmy. Wake up."

Her eyes opened. Milton—no, Kurt. Kurt Tradin said, "Thank God!" His bleak face was grey, but not as the Thing had been grey, somehow not. His eyes were tired, so tired, and a muscle twitched at the base of his broad nose. His sleeve was gashed, soaked with clotted blood, and his gun was again in his hand. He was already bending to her, he stooped nearer and his arms slid under her. His strong arms closed about her, lifted her, and as she swung effortlessly up she saw a grey, foul mass, motionless on the ground.

"You killed it," she mumbled.

"Yes," he responded, and his accents were oddly thick. "Yes, I killed it"

She understood now. Kurt had killed the Thing and saved her. Kurt had saved Milton and her before, up there on the Highway. All night, many nights, Kurt had been patrolling the roads, fighting the grey horror, fighting the madness that the Things had brought to the valley, to the village, to Milton. Fighting alone, always alone. Why had not Kurt run away? Why had he stayed here to fight his lonely battle?

He was climbing down, holding her, pushing through the brambles, but he answered her, as though he had read her thoughts. "I love you, Emmy." His tired voice was thick, broken. "I have waited for you so long. So long."

"Hush," Emma said. "You—mustn't." She closed her eyes to shut out the dreariness that made his lined face even more bleak. "Not—yet"

The memory of Milton was too warm, too dear as yet. Even with what she had read in his eyes between them. But later... Kurt's arm cradled her so powerfully, so gently. She was so safe... so... Emma sighed, slid into exhausted sleep.

Kurt drifted through her dreams, padding barefoot along the dusty road from school, carrying her books. Kurt, standing, a dark and somehow lonesome figure at the gate, watching her window whose curtain he could not know veiled her responsive watching. Speaking his love, haltingly, in a quiet dusk that for once was not gloomy with dread. Kurt, in that last scene, that last but one, his ungainly figure bowed, cringing beneath the awful blast of Jeremiah Sprool's wrath. "Marry Emma," the old man roared. "Marry my granddaughter! Put the taint of your blood into the veins o' the Sprools! We're clean, Tradin. We're clean. By Jehovah, you're as mad as the rest o' the valley. Mad as..."

The look on the young man's face had stopped grandfather there. The lifeless look and the blaze in his dark eyes, the lurid, flaming blaze whose agony had stilled even the ancient's unruly tongue. But Kurt turned, blundered blindly out of the house. And the dream ended with grandfather's gigantic figure in the doorway, his voice recovered, shouting out into the night. "Mad, damn you. Crazy. Crazy as a bat."

Emma had not been much frightened by Jeremiah's apoplectic rage; his fits of uncontrolled temper were all too frequent. She had waited for Kurt to return, had sent him messages despite the old man's prohibition. But she had never spoken to Tradin again till he had appeared, unexpectedly, at the station in Kingville, had husked his promise to wait for her, and vanished before she could respond. That incident too, was repeated in her dreams, and then her sleep deepened to a dreamless torpor.

And she woke with a start. Bemused by her dreams and her sleep, she could not for a moment tell the source of the welling tide of fear that seemed to sweep up and over her in that instant of waking. But fear lay on her breast like a leaden, oppressive hand, and the shadows on the papered ceiling at which she stared were dark shapes of brooding menace. She was on the old sofa in the parlor, Gram would scold...

Memory seeped back, distorted, but full-panoplied with horror. Gram was dead. Milton was dead, they were in the same coffin and that coffin was in this room. Kurt...

Kurt was bending over her, it was his hand that was heavy on her breast. Yellow lamplight, glancing at some odd angle across his face made of it a shadowy chiaroscuro that was somehow demoniac. His lips were too full, creepingly sensuous; his nostrils pinched, quivering; tiny lights crawled wormlike in the abysmal depths of his eyes. Emma fought down fright that plugged speech, husked something. "Don't," she meant it to be. "Don't."

Tradin moved, and the girl came fully awake. It must have been a trick of light and shade, the appalling mask his face had been, for it was not like that any more. Contorted by emotion, though—that it was, and ashen with fatigue. But his hand was on her uncovered breast. "Don't," Emma repeated and pushed at it feebly. It fell away. Released, she sat up, became aware that he was kneeling beside her, that he was quivering. That his lips were moving, were dripping passion-slowed words.

"Em. Em darling. I couldn't help it. I love you so."

Weakly, she swayed toward him, toward his reaching arms, though deep within her a warning bell rang shrilly. With Milton so newly dead! She was mad, mad. Her eyes slid over Kurt's shoulder, across the room, appealing to the coffin where Milton lay for help against this madness that ran riot in her veins. Queerly it seemed to rock, to sway on its trestles.

Pale fingers came up out of the grim casket and gripped its edge. A torso jerked upright, rising grotesquely from its ebon depths and Milton's pallid, reproachful face turned toward her. His arm lifted—the arm of a dead man—and his long, bloodless hand clenched, opened, pointed at her in ghastly accusation!

"Milton," she heard herself gasp. "Milton! I?"

Kurt exploded to his feet, blotting the grisly sight from her. "You!" he screamed. "You!" and lunged toward the awakened dead, his great fist lifting, knotting in the lamplight. "Damn you!" That rocklike fist swept down...

Some power outside herself hurled Emma from the sofa, catapulted her from its springs in a catlike leap to the enraged farmer's back. Her shriek was a feline mewl as she raked Tradin's face with the nails of her one hand and swiped at his descending arm with the other—swiped aside that crushing blow to make it land on wood instead of Milton's skull that it would have crushed.

Tradin was thrown against the coffin under the fury of her onslaught, toppled it. It crashed thunderously, wood split. Emma ripped nails again through flesh, gouged for eyes like the wild thing she had become. Kurt ducked forward, suddenly. She flew over his head, crashed among the splintered fragments of the casket. The jagged wood of the smashed coffin ripped her, but its cushions of funereal satin pillowed her fall. Her leg signaled excruciating pain, and she could not move it. She squirmed over to the stamping of feet, to the snarl of battling beasts.

A heaving mass reeled about the room, the two men locked in tearing, primeval combat. Two men—oh God! Kurt was a man, but the other—Milton. What was he?

His slender form was so frail, so weak, against the other's bulk. Ordinarily Tradin could split him in two, tear him apart with those great paws of his that had wrestled so long with the soil. Not now. Not that vibrant, terrible being who had returned from death. Now that creature who bit, and tore, and kicked, was an overpowering, black whirlwind that drove Kurt back, drove him back, across the floor. No human being could stand against that snarling, growling, squealing fury come back from the grave.

The whirlwind of combat struck the wall. Milton—whatever it was that Milton had become—swarmed all over Tradin. But the farmer, at bay, crouched and lashed out with his giant fists. Lashed and landed. Milton was thrown back, was staggered. Suddenly his figure was red with the tint of hell-fire, was wreathed in black smoke, and he hurtled in again, hurtled at the embattled rustic. Resistlessly the revenant drove Kurt along the wall as the long, fluttering shadows of battle were lurid-edged. Emma watching, was rigid with awed horror, with a fear that came from beyond earth. The jagged void of the broken window gaped behind Tradin; in the instant the girl realized that it had been his goal he hurled himself backward through it, was gone.

Milton screeched blasphemy, vanished. Emma was not sure, not quite sure, that he had gone through the window after his victim. But gruesome thumpings came from outside, were succeeded by sudden silence.

By silence that was broken by a strange crackling, here within, by an ominous hiss. Milton had vanished, but a red glare still danced in this parlor where horror had flared to unbelievable life, and edged billows of greasy, black smoke. The stench of burning was acrid in her nose, stung her throat. Good Lord! The place was ablaze! Sometime in the whirlwind, eerie battle the table had been overturned on which Kurt had set the lamp, and spilled oil on dried old wood fed flames like kindling.

Emma sprang to her feet, toppled as agony stabbed her thigh, crashed down to the floor. God! Oh God! Her leg was broken. She could not stand. Could not run to escape the flames!

The fire spread rapidly now, having gained strength while she watched the gruesome fight. The floor was a sea of wavering, leaping orange, and red, and curling, spitting blue. The door was cut off, by which she might have crawled to the foyer and out to safety. Rivulets of flame ran between her and the window. A curtain caught and flared.

Pungent smoke tore at her lungs with its black knives. Heat beat at her, stinging. Long fingers of flame reached out across the floor for her. She beat at them, beat them out with scorched, blistering hands.

But the forefront of the main blaze roared closer, ever closer. And she could not beat that back.

ALL across the side and the front of the room, the flames soared, incandescent, their glare blinding. The roar of the fire was a vast surf, the surge of heat from its blaze was a great wave overwhelming the helpless girl. A black pall of smoke eddied along the ceiling, billowed, billowed lower and lower to engulf her, to throttle her. Emma smelled burning hair—a viscous insect stung her scalp—she snatched at the ember—tore it from her head with a handful of her hair. She rolled away from the flames, agonizing to the grating of fractured bone surfaces one on the other—rolled against the furthest wall. Groveled there, mewling, as inescapable destruction crept nearer with cruel tongues.

Emma's skin crisped to the furnace blast beating on her doomed body. She writhed in the searing heat, as a worm will writhe in flame, and her arm flung over, thumped on the hot floor, thumped against something that clinked metallically. She glared at what she had touched, saw that it was the knife she had clutched out there when Kurt had saved her from a more merciful death, red-shining now, reflecting the blaze.

She snatched at the blade, seized it, clutching. The razor edge slashed her palm, reddened with her blood, but she did not feel its pain. It offered a better, more merciful death than the immolation inevitable now in seconds. She pulled the knife toward her, dropped it momentarily to gain a grip on its hilt, jerked the sharp point to her breast. Poised it an instant while she muttered a prayer, for the peace of her soul and of Milton's. Of Milton's that had been brought back to his dead body to save her from unpardonable sin. Then Emma's muscles tensed for the death stroke, and she shut her eyes to take it.

The knife came alive, jerked from her grip. Unbelievably there was someone in the room, bending over her. Someone! Oh God! Horror was bending over her, horror worse than the knife or the flame. A Thing bulky and formless, its grey orange-margined now by the luminance of the roaring blaze.

It had come for her, come to take her for its own hideous purpose, and it was not a being of this earth. No living thing could have come through that holocaust alive? A lumping tendril slapped across her face, a hot crust on it broke, and wet viscidness squashed over her mouth, her nose and her eyes. She felt another tentacle seethe under her, felt herself lifted, as she writhed, feebly protestant, and her broken leg dangled to stab agony up her thigh, her flank. She was crushed into the noisome, viscid humidity of its foul mass. The stuff flowed over her, swallowed her.

The Thing was moving, was carrying her off. Uttermost terror shrieked in every cell of her anguished frame. Better the fire, oh God, better the fire than this! It was carrying her through the flame. She felt the vile stuff enveloping her grow hot to the fire, heard the sizzle of steam. She could not breathe—could not—

The matrix in which she was contained crawled, and somehow her mouth was free, so that air reached her lungs; dank, cold air freighted with corpse-smell. They were out of the fire then, incredibly out, and the Thing was lumbering with her to its lair. Somewhere in the mass a pulse beat, as if it had a heart. A heart that pounded with some strange excitement, pounded with a rhythm of grotesque life. The pud, pud in her ears was the muted beat of a drum of doom.

The ungainly heaving that told her her captor still moved ceased. She sensed that it had come to its journey's end, that it had brought her to its lurking place, was about to work its will with her. Fear ran icy in her blood stream, sapped all vitality from her battered body as with a sucking plop she came free of the Thing's foul substance and knew dimly that it had laid her down on some hard, unyielding surface. Only pain kept consciousness in her: the jabbing torture of her ruptured tibia: the agony of her lacerated, scorched flesh. The thick stuff still adhering blinded and deafened her. She lay unmoving where the Thing had laid her, waiting. Waiting for the ultimate horror.

And a tenuous hope trailed across the quivering blank of her beleaguered brain. Not for herself. For Milton, for her husband who had died and yet was not dead. A hope that his reanimated body had lost the hideous mockery of life with which she had last seen it inflamed. That it was at rest, the body that had been so warm, so near, so dear to her...

Nothing was happening, nothing at all. What was it waiting for, the Thing that had relentlessly pursued her, harried her, that had come through flames to take her? The agony of suspense expanded like a black bubble, bursting her aching skull, till desperation seized her and she drove a fist across her eyes, wiping away the blinding mess.

Above her, redness glowed through a shimmering network interlaced by things twisted, grotesque, reptilian. Bastions lifted darkly about her to support that eerie roof. Where was she? In some black chapel of the damned? In some Luciferean cloister through whose pierced ceiling the reflection of hell's lurid fires flickered restlessly in their eternal dance? Wherever she was, the dull realization penetrated, whatever place this was, she was alone in it. That which had brought her here had departed, on some obscure, revolting errand of its own. She would stay here, it could be sure of that, she would stay here till it returned.

Stay here? Grim humor twisted Emma's dry, cracked lips. Not she. She couldn't walk with this poor shattered leg of hers that hurt so damnably; but she could crawl. On hands and one knee she could crawl. The Thing wouldn't find her here when it came.

Hurry! It may be coming back now, right now. Hurry! Turn over. Bite your lips against the screams that tear at your throat as pain runs like liquid fire through every quivering inch of you, and turn. So. That was the hardest part. Now start crawling. Lift yourself on your pushing-down arms, get your one good leg under you and a start. Never mind that other leg—it isn't any good to you. Leave it. Leave it to mock the Thing. Hurry! That far-off thud may be its gooey footfall as it returns. But make no noise. Be silent as the grave. Stifle those shrieks—they won't ease the pain and may warn the Thing that you are escaping it. Ohhhhh. That was a bad one! Hurry!

Something is dragging behind! Your other leg? Well, you haven't time to pull it off, let it drag. You haven't time, the grey horror will catch you if you stop for that. Hurry! Stop that whimpering—crying won't help you. Stop it. You've gone a yard now, a whole yard. Keep going. Keep going! how long?—Never mind how long it has taken you to crawl that yard, keep going. Hurry!

No, that isn't Gram lying there, ahead, grinning at you. It can't be Gram, she's dead? So are you dead? Don't fool yourself, you wish you were. You couldn't hurt so if you were dead. You wouldn't have to crawl through Hell if you were dead. But hurry!

Maybe Milton will be waiting for you when you are really dead. In Hell? Perhaps. Hell itself burned in his eyes when he looked at you before he lunged into the parlor and died. Stop thinking—and crawl. Hurry! You have forgotten why you were crawling, why you must hurry? Never mind, keep going. Don't turn aside. Don't turn to get past the dark, low, mound across whose end the red light flickers and makes you think its Gram's skull-like face grinning at you. You've reached it now. Climb over it. Climb! Put your hand on it and push over. It's cold, clammy. It has the feel of cold, dead flesh! The brittle bones of its shoulder crunch under your weight and its hand, its dead hand, jerks up and slaps you stingingly across the face...

It is Gram! Oh God! Oh dear God! It is Gram!