RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

RGL e-Book Cover 2014©

"Chronicles of Martin Hewitt," D. Appleton & Co., New York, 1896

This special RGL/PGA edition of Chronicles of Martin Hewitt includes 42 illustrations that D. Murray Smith drew for The Windsor Magazine and six illustrations by William Kirkpatrick from the edition of the book published by L.C. Page Co., Boston, in 1907.

The L.C. Page edition prefaced the book with the following publisher's note:

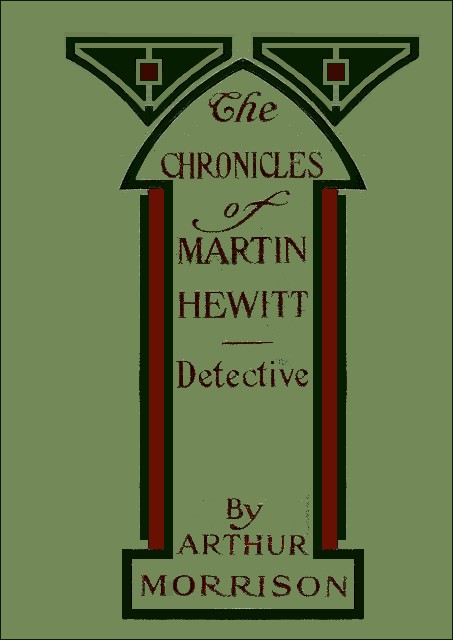

"The success of Mr. Arthur Morrison's recent books, The Green Diamond and The Red Triangle, has made the demand for the reissue of the present edition of his first (sic) success, The Chronicles of Martin Hewitt, Detective, imperative. This book relates the earlier adventures of the keen-witted investigator, whose solution of the mystery of the Red Triangle is well remembered by the readers of that clever detective story. The value and interest of the new edition is enhanced by six spirited illustrations drawn by Mr. William Kirkpatrick."

The editor who wrote this seems unaware of the fact that Morrison's first big success in the detective genre was Martin Hewitt, Investigator. Indeed, the very title of the L.C. Page edition, The Chronicles of Martin Hewitt, Detective, appears to be a modified portmanteau of the titles of the first and second book in the series, for the original title of the present volume was simply Chronicles of Martin Hewitt. — RG.

"Chronicles of Martin Hewitt," L.C. Page Co., Boston, 1907

Note: Illustrations 1A, 8A, 15A, 22A, 23A, and 37A were drawn by William Kirkpatrick, the others by D. Murray Smith

I HAD been working double tides for a month: at night on my morning paper, as usual; and in the morning on an evening paper as locum tenens for another man who was taking a holiday. This was an exhausting plan of work, although it only actually involved some six hours' attendance a day, or less, at the two offices. I turned up at the headquarters of my own paper at ten in the evening, and by the time I had seen the editor, selected a subject, written my leader, corrected the slips, chatted, smoked, and so on, and cleared off, it was very usually one o'clock. This meant bed at two, or even three, after supper at the club.

This was all very well at ordinary periods, when any time in the morning would do for rising, but when I had to be up again soon after seven, and round at the evening paper office by eight, I naturally felt a little worn and disgusted with things by midday, after a sharp couple of hours' leaderette scribbling and paragraphing, with attendant sundries.

But the strain was over, and on the first day of comparative comfort I indulged in a midday breakfast and the first undisgusted glance at a morning paper for a month. I felt rather interested in an inquest, begun the day before, on the body of a man whom I had known very slightly before I took to living in chambers.

His name was Gavin Kingscote, and he was an artist of a casual and desultory sort, having, I believe, some small private means of his own. As a matter of fact, he had boarded in the same house in which I had lodged myself for a while, but as I was at the time a late homer and a fairly early riser, taking no regular board in the house, we never became much acquainted. He had since, I understood, made some judicious Stock Exchange speculations, and had set up house in Finchley.

Now the news was that he had been found one morning murdered in his smoking-room, while the room itself, with others, was in a state of confusion. His pockets had been rifled, and his watch and chain were gone, with one or two other small articles of value. On the night of the tragedy a friend had sat smoking with him in the room where the murder took place, and he had been the last person to see Mr Kingscote alive. A jobbing gardener, who kept the garden in order by casual work from time to time, had been arrested in consequence of footprints, exactly corresponding with his boots, having been found on the garden beds near the French window of the smoking-room.

I finished my breakfast and my paper, and Mrs Clayton, the housekeeper, came to clear my table. She was sister of my late landlady of the house where Kingscote had lodged, and it was by this connection that I had found my chambers. I had not seen the housekeeper since the crime was first reported, so I now said:

"This is shocking news of Mr Kingscote, Mrs Clayton. Did you know him yourself?"

She had apparently only been waiting for some such remark to burst out with whatever information she possessed.

"Yes, sir," she exclaimed: "shocking indeed. Pore young feller! I see him often when I was at my sister's, and he was always a nice, quiet gentleman, so different from some. My sister, she's awful cut up, sir, I assure you. And what d'you think 'appened, sir, only last Tuesday? You remember Mr Kingscote's room where he painted the woodwork so beautiful with gold flowers, and blue, and pink? He used to tell my sister she'd always have something to remember him by. Well, two young fellers, gentlemen I can't call them, come and took that room (it being to let), and went and scratched off all the paint in mere wicked mischief, and then chopped up all the panels into sticks and bits! Nice sort o' gentlemen them! And then they bolted in the morning, being afraid, I s'pose, of being made to pay after treating a pore widder's property like that. That was only Tuesday, and the very next day the pore young gentleman himself's dead, murdered in his own 'ouse, and him goin' to be married an' all! Dear, dear! I remember once he said—"

Mrs Clayton was a good soul, but once she began to talk some one else had to stop her. I let her run on for a reasonable time, and then rose and prepared to go out. I remembered very well the panels that had been so mischievously destroyed. They made the room the showroom of the house, which was an old one. They were indeed less than half finished when I came away, and Mrs Lamb, the landlady, had shown them to me one day when Kingscote was out. All the walls of the room were panelled and painted white, and Kingscote had put upon them an eccentric but charming decoration, obviously suggested by some of the work of Mr Whistler. Tendrils, flowers, and butterflies in a quaint convention wandered thinly from panel to panel, giving the otherwise rather uninteresting room an unwonted atmosphere of richness and elegance. The lamentable jackasses who had destroyed this had certainly selected the best feature of the room whereon to inflict their senseless mischief.

I strolled idly downstairs, with no particular plan for the afternoon in my mind, and looked in at Hewitt's offices. Hewitt was reading a note, and after a little chat he informed me that it had been left an hour ago, in his absence, by the brother of the man I had just been speaking of.

"He isn't quite satisfied," Hewitt said, "with the way the police are investigating the case, and asks me to run down to Finchley and look round. Yesterday I should have refused, because I have five cases in progress already, but today I find that circumstances have given me a day or two. Didn't you say you knew the man?"

"Scarcely more than by sight. He was a boarder in the house at Chelsea where I stayed before I started chambers."

"Ah, well; I think I shall look into the thing. Do you feel particularly interested in the case? I mean, if you've nothing better to do, would you come with me?"

"I shall be very glad," I said. "I was in some doubt what to do with myself. Shall you start at once?"

"I think so. Kerrett, just call a cab. By the way, Brett, which paper has the fullest report of the inquest yesterday? I'll run over it as we go down."

As I had only seen one paper that morning, I could not answer Hewitt's question. So we bought various papers as we went along in the cab, and I found the reports while Martin Hewitt studied them. Summarized, this was the evidence given:

Sarah Dodson, general servant, deposed that she had been in service at Ivy Cottage, the residence of the deceased, for five months, the only other regular servant being the housekeeper and cook. On the evening of the previous Tuesday both servants retired a little before eleven, leaving Mr Kingscote with a friend in the smoking or sitting room. She never saw her master again alive. On coining downstairs the following morning and going to open the smoking-room windows, she was horrified to discover the body of Mr Kingscote lying on the floor of the room with blood about the head. She at once raised an alarm, and, on the instructions of the housekeeper, fetched a doctor, and gave information to the police. In answer to questions, witness stated she had heard no noise of any sort during the night, nor had anything suspicious occurred.

Hannah Carr, housekeeper and cook, deposed that she had been in the late Mr Kingscote's service since he had first taken Ivy Cottage—a period of rather more than a year. She had last seen the deceased alive on the evening of the previous Tuesday, at half-past ten, when she knocked at the door of the smoking-room, where Mr Kingscote was sitting with a friend, to ask if he would require anything more. Nothing was required, so witness shortly after went to bed. In the morning she was called by the previous witness, who had just gone downstairs, and found the body of deceased lying as described. Deceased's watch and chain were gone, as also was a ring he usually wore, and his pockets appeared to have been turned out. All the ground floor of the house was in confusion, and a bureau, a writing-table, and various drawers were open—a bunch of keys usually carried by deceased being left hanging at one keyhole. Deceased had drawn some money from the bank on the Tuesday, for current expenses; how much she did not know. She had not heard or seen anything suspicious during the night. Besides Dodson and herself, there were no regular servants; there was a charwoman, who came occasionally, and a jobbing gardener, living near, who was called in as required.

Mr James Vidler, surgeon, had been called by the first witness between seven and eight on Wednesday morning. He found the deceased lying on his face on the floor of the smoking-room, his feet being about eighteen inches from the window, and his head lying in the direction of the fireplace. He found three large contused wounds on the head, any one of which would probably have caused death. The wounds had all been inflicted, apparently, with the same blunt instrument—probably a club or life preserver, or other similar weapon. They could not have been done with the poker. Death was due to concussion of the brain, and deceased had probably been dead seven or eight hours when witness saw him. He had since examined the body more closely, but found no marks at all indicative of a struggle having taken place; indeed, from the position of the wounds and their severity, he should judge that the deceased had been attacked unawares from behind, and had died at once. The body appeared to be perfectly healthy.

Then there was police evidence, which showed that all the doors and windows were found shut and completely fastened, except the front door, which, although shut, was not bolted. There were shutters behind the French windows in the smoking-room, and these were found fastened. No money was found in the bureau, nor in any of the opened drawers, so that if any had been there, it had been stolen. The pockets were entirely empty, except for a small pair of nail scissors, and there was no watch upon the body, nor a ring. Certain footprints were found on the garden beds, which had led the police to take certain steps. No footprints were to be seen on the garden path, which was hard gravel.

Mr Alexander Campbell, stockbroker, stated that he had known deceased for some few years, and had done business for him. He and Mr Kingscote frequently called on one another, and on Tuesday evening they dined together at Ivy Cottage. They sat smoking and chatting till nearly twelve o'clock, when Mr Kingscote himself let him out, the servants having gone to bed. Here the witness proceeded rather excitedly: "That is all I know of this horrible business, and I can say nothing else. What the police mean by following and watching me—"

The Coroner: "Pray be calm, Mr Campbell. The police must do what seems best to them in a case of this sort. I am sure you would not have them neglect any means of getting at the truth."

Witness: "Certainly not. But if they suspect me, why don't they say so? It is intolerable that I should be—"

The Coroner: "Order, order, Mr Campbell. You are here to give evidence."

The witness then, in answer to questions, stated that the French windows of the smoking-room had been left open during the evening, the weather being very warm. He could not recollect whether or not deceased closed them before he left, but he certainly did not close the shutters. Witness saw nobody near the house when he left.

Mr Douglas Kingscote, architect, said deceased was his brother. He had not seen him for some months, living as he did in another part of the country. He believed his brother was fairly well off, and he knew that he had made a good amount by speculation in the last year or two. Knew of no person who would be likely to owe his brother a grudge, and could suggest no motive for the crime except ordinary robbery. His brother was to have been married in a few weeks. Questioned further on this point, witness said that the marriage was to have taken place a year ago, and it was with that view that Ivy Cottage, deceased's residence, was taken. The lady, however, sustained a domestic bereavement, and afterwards went abroad with her family: she was, witness believed, shortly expected back to England.

William Bates, jobbing gardener, who was brought up in custody, was cautioned, but elected to give evidence. Witness, who appeared to be much agitated, admitted having been in the garden of Ivy Cottage at four in the morning, but said that he had only gone to attend to certain plants, and knew absolutely nothing of the murder. He however admitted that he had no order for work beyond what he had done the day before. Being further pressed, witness made various contradictory statements, and finally said that he had gone to take certain plants away.

The inquest was then adjourned.

This was the cast as it stood—apparently not a case presenting any very striking feature, although there seemed to me to be doubtful peculiarities in many parts of it. I asked Hewitt what he thought.

"Quite impossible to think anything, my boy, just yet; wait till we see the place. There are any number of possibilities. Kingscote's friend, Campbell, may have come in again, you know, by way of the window—or he may not. Campbell may have owed him money or something—or he may not. The anticipated wedding may have something to do with it—or, again, that may not. There is no limit to the possibilities, as far as we see from this report—a mere dry husk of the affair. When we get closer we shall examine the possibilities by the light of more detailed information. One probability is that the wretched gardener is innocent. It seems to me that his was only a comparatively blameless manoeuvre not unheard of at other times in his trade. He came at four in the morning to steal away the flowers he had planted the day before, and felt rather bashful when questioned on the point. Why should he trample on the beds, else? I wonder if the police thought to examine the beds for traces of rooting up, or questioned the housekeeper as to any plants being missing? But we shall see."

We chatted at random as the train drew near Finchley, and I mentioned inter alia the wanton piece of destruction perpetrated at Kingscote's late lodgings. Hewitt was interested.

"That was curious," he said, "very curious. Was anything else damaged? Furniture and so forth?"

"I don't know. Mrs Clayton said nothing of it, and I didn't ask her. But it was quite bad enough as it was. The decoration was really good, and I can't conceive a meaner piece of tomfoolery than such an attack on a decent woman's property."

Then Hewitt talked of other cases of similar stupid damage by creatures inspired by a defective sense of humour, or mere love of mischief. He had several curious and sometimes funny anecdotes of such affairs at museums and picture exhibitions, where the damage had been so great as to induce the authorities to call him in to discover the offender. The work was not always easy, chiefly from the mere absence of intelligible motive; not, indeed, always successful. One of the anecdotes related to a case of malicious damage to a picture—the outcome of blind artistic jealousy—a case which had been hushed up by a large expenditure in compensation. It would considerably startle most people, could it be printed here, with the actual names of the parties concerned.

Ivy Cottage, Finchley, was a compact little house, standing in a compact little square of garden, little more than a third of an acre, or perhaps no more at all. The front door was but a dozen yards or so back from the road, but the intervening space was well treed and shrubbed. Mr Douglas Kingscote had not yet returned from town, but the housekeeper, an intelligent, matronly woman, who knew of his intention to call in Martin Hewitt, was ready to show us the house.

"First," Hewitt said, when we stood in the smoking-room, "I observe that somebody has shut the drawers and the bureau. That is unfortunate. Also, the floor has been washed and the carpet taken up, which is much worse. That, I suppose, was because the police had finished their examination, but it doesn't help me to make one at all. Has anything—anything at all—been left as it was on Tuesday morning?"

"Well, sir, you see everything was in such a muddle," the housekeeper began, "and when the police had done—"

"Just so. I know. You 'set it to rights', eh? Oh, that setting to rights! It has lost me a fortune at one time and another. As to the other rooms, now, have they been set to rights?"

"Such as was disturbed have been put right, sir, of course."

"Which were disturbed? Let me see them. But wait a moment."

He opened the French windows, and closely examined the catch and bolts. He knelt and inspected the holes whereinto the bolts fell, and then glanced casually at the folding shutters. He opened a drawer or two, and tried the working of the locks with the keys the housekeeper carried. They were, the housekeeper explained, Mr Kingscote's own keys. All through the lower floors Hewitt examined some things attentively and closely, and others with scarcely a glance, on a system unaccountable to me. Presently, he asked to be shown Mr Kingscote's bedroom, which had not been disturbed, "set to rights," or slept in since the crime. Here, the housekeeper said, all drawers were kept unlocked but two—one in the wardrobe and one in the dressing-table, which Mr Kingscote had always been careful to keep locked. Hewitt immediately pulled both drawers open without difficulty. Within, in addition to a few odds and ends, were papers. All the contents of these drawers had been turned over confusedly, while those of the unlocked drawers were in perfect order.

"The police," Hewitt remarked, "may not have observed these matters. Any more than such an ordinary thing as this," he added, picking up a bent nail lying at the edge of a rug.

The housekeeper doubtless took the remark as a reference to the entire unimportance of a bent nail, but I noticed that Hewitt dropped the article quietly into his pocket.

We came away. At the front gate we met Mr Douglas Kingscote, who had just returned from town. He introduced himself, and expressed surprise at our promptitude both of coming and going.

"You can't have got anything like a clue in this short time, Mr Hewitt?" he asked.

"Well, no," Hewitt replied, with a certain dryness, "perhaps not. But I doubt whether a month's visit would have helped me to get anything very striking out of a washed floor and a houseful of carefully cleaned-up and 'set-to-rights' rooms. Candidly, I don't think you can reasonably expect much of me. The police have a much better chance—they had the scene of the crime to examine. I have seen just such a few rooms as anyone might see in the first well-furnished house he might enter. The trail of the housemaid has overlaid all the others."

"I'm very sorry for that; the fact was, I expected rather more of the police; and, indeed, I wasn't here in time entirely to prevent the clearing up. But still, I thought your well-known powers—"

"My dear sir, my 'well-known powers' are nothing but common sense assiduously applied and made quick by habit. That won't enable me to see the invisible."

"But can't we have the rooms put back into something of the state they were in? The cook will remember—"

"No, no. That would be worse and worse: that would only be the housemaid's trail in turn overlaid by the cook's. You must leave things with me for a little, I think."

"Then you don't give the case up?" Mr Kingscote asked anxiously.

"Oh, no! I don't give it up just yet. Do you know anything of your brother's private papers—as they were before his death?"

"I never knew anything till after that. I have gone over them, but they are all very ordinary letters. Do you suspect a theft of papers?"

Martin Hewitt, with his hands on his stick behind him, looked sharply at the other, and shook his head. "No," he said, "I can't quite say that."

We bade Mr Douglas Kingscote good-day, and walked towards the station. "Great nuisance, that setting to rights," Hewitt observed, on the way. "If the place had been left alone, the job might have been settled one way or another by this time. As it is, we shall have to run over to your old lodgings."

"My old lodgings?" I repeated, amazed. "Why my old lodgings?"

Hewitt turned to me with a chuckle and a wide smile. "Because we can't see the broken panel-work anywhere else," he said. "Let's see—Chelsea, isn't it?"

"Yes, Chelsea. But why—you don't suppose the people who defaced the panels also murdered the man who painted them?"

"Well," Hewitt replied, with another smile, "that would be carrying a practical joke rather far, wouldn't it? Even for the ordinary picture damager."

"You mean you don't think they did it, then? But what do you mean?"

"My dear fellow, I don't mean anything but what I say. Come now, this is rather an interesting case despite appearances, and it has interested me: so much, in fact, that I really think I forgot to offer Mr Douglas Kingscote my condolence on his bereavement. You see a problem is a problem, whether of theft, assassination, intrigue, or anything else, and I only think of it as one. The work very often makes me forget merely human sympathies. Now, you have often been good enough to express a very flattering interest in my work, and you shall have an opportunity of exercising your own common sense in the way I am always having to exercise mine. You shall see all my evidence (if I'm lucky enough to get any) as I collect it, and you shall make your own inferences. That will be a little exercise for you; the sort of exercise I should give a pupil if I had one. But I will give you what information I have, and you shall start fairly from this moment. You know the inquest evidence such as it was, and you saw everything I did in Ivy Cottage?"

"Yes; I think so. But I'm not much the wiser."

"Very well. Now I will tell you. What does the whole case look like? How would you class the crime?"

"I suppose as the police do. An ordinary case of murder with the object of robbery."

"It is not an ordinary case. If it were, I shouldn't know as much as I do, little as that is; the ordinary cases are always difficult. The assailant did not come to commit a burglary, although he was a skilled burglar, or one of them was, if more than one were concerned. The affair has, I think, nothing to do with the expected wedding, nor had Mr Campbell anything to do in it—at any rate, personally—nor the gardener. The criminal (or one of them) was known personally to the dead man, and was well-dressed: he (or again one of them, and I think there were two) even had a chat with Mr Kingscote before the murder took place. He came to ask for something which Mr Kingscote was unwilling to part with,—perhaps hadn't got. It was not a bulky thing. Now you have all my materials before you."

"But all this doesn't look like the result of the blind spite that would ruin a man's work first and attack him bodily afterwards."

"Spite isn't always blind, and there are other blind things besides spite; people with good eyes in their heads are blind sometimes, even detectives."

"But where did you get all this information? What makes you suppose that this was a burglar who didn't want to burgle, and a well-dressed man, and so on?"

Hewitt chuckled and smiled again.

"I saw it—saw it, my boy, that's all," he said "But here comes the train."

On the way back to town, after I had rather minutely described Kingscote's work on the boarding-house panels, Hewitt asked me for the names and professions of such fellow lodgers in that house as I might remember. "When did you leave yourself?" he ended.

"Three years ago, or rather more. I can remember Kingscote himself; Turner, a medical student—James Turner, I think; Harvey Challitt, diamond merchant's articled pupil—he was a bad egg entirely, he's doing five years for forgery now; by the bye he had the room we are going to see till he was marched off, and Kingscote took it—a year before I left; there was Norton—don't know what he was 'something in the City', I think; and Carter Paget, in the Admiralty Office. I don't remember any more at this moment; there were pretty frequent changes. But you can get it all from Mrs Lamb, of course."

"Of course; and Mrs Lamb's exact address is—what?"

I gave him the address, and the conversation became disjointed. At Farringdon station, where we alighted, Hewitt called two hansoms. Preparing to enter one, he motioned me to the other, saying, "You get straight away to Mrs Lamb's at once. She may be going to burn that splintered wood, or to set things to rights, after the manner of her kind, and you can stop her. I must make one or two small inquiries, but I shall be there half an hour after you."

"Shall I tell her our object?"

"Only that I may be able to catch her mischievous lodgers—nothing else yet." He jumped into the hansom and was gone.

I found Mrs Lamb still in a state of indignant perturbation over the trick served her four days before. Fortunately, she had left everything in the panelled room exactly as she had found it, with an idea of being better able to demand or enforce reparation should her lodgers return. "The room's theirs, you see, sir," she said, "till the end of the week, since they paid in advance, and they may come back and offer to make amends, although I doubt it. As pleasant-spoken a young chap as you might wish, he seemed, him as come to take the rooms. 'My cousin,' says he, 'is rather an invalid, havin' only just got over congestion of the lungs, and he won't be in London till this evening late. He's comin' up from Birmingham,' he ses, 'and I hope he won't catch a fresh cold on the way, although of course we've got him muffled up plenty.' He took the rooms, sir, like a gentleman, and mentioned several gentlemen's names I knew well, as had lodged here before; and then he put down on that there very table, sir"—Mrs Lamb indicated the exact spot with her hand, as though that made the whole thing much more wonderful—"he put down on that very table a week's rent in advance, and ses, 'That's always the best sort of reference, Mrs Lamb, I think,' as kind-mannered as anything—and never 'aggled about the amount nor nothing. He only had a little black bag, but he said his cousin had all the luggage coming in the train, and as there was so much, p'r'aps they wouldn't get it here till next day. Then he went out and came in with his cousin at eleven that night—Sarah let 'em in her own self—and in the morning they was gone—and this!" Poor Mrs Lamb, plaintively indignant, stretched her arm towards the wrecked panels.

"If the gentleman as you say is comin' on, sir," she pursued, "can do anything to find 'em, I'll prosecute 'em, that I will, if it costs me ten pound. I spoke to the constable on the beat, but he only looked like a fool, and said if I knew where they were I might charge 'em with wilful damage, or county court 'em. Of course I know I can do that if I knew where they were, but how can I find 'em? Mr Jones he said his name was; but how many Joneses is there in London, sir?"

I couldn't imagine any answer to a question like this, but I condoled with Mrs Lamb as well as I could. She afterwards went on to express herself much as her sister had done with regard to Kingscote's death, only as the destruction of her panels loomed larger in her mind, she dwelt primarily on that. "It might almost seem," she said, "that somebody had a deadly spite on the pore young gentleman, and went breakin' up his paintin' one night, and murderin' him the next!"

I examined the broken panels with some care, having half a notion to attempt to deduce something from them myself, if possible. But I could deduce nothing. The beading had been taken out, and the panels, which were thick in the centre but bevelled at the edges, had been removed and split up literally into thin firewood, which lay in a tumbled heap on the hearth and about the floor. Every panel in the room had been treated in the same way, and the result was a pretty large heap of sticks, with nothing whatever about them to distinguish them from other sticks, except the paint on one face, which I observed in many places had been scratched and scraped away. The rug was drawn half across the hearth, and had evidently been used to deaden the sound of chopping. But mischief—wanton and stupid mischief—was all I could deduce from it all.

Mr Jones's cousin, it seemed, only Sarah had seen, as she admitted him in the evening, and then he was so heavily muffled that she could not distinguish his features, and would never be able to identify him. But as for the other one, Mrs Lamb was ready to swear to him anywhere.

Hewitt was long in coming, and internal symptoms of the approach of dinner-time (we had had no lunch) had made themselves felt before a sharp ring at the door-bell foretold his arrival. "I have had to wait for answers to a telegram," he said in explanation, "but at any rate I have the information I wanted. And these are the mysterious panels, are they?"

Mrs Lamb's true opinion of Martin Hewitt's behaviour as it proceeded would have been amusing to know. She watched in amazement the antics of a man who purposed finding out who had been splitting sticks by dint of picking up each separate stick and staring at it. In the end he collected a small handful of sticks by themselves and handed them to me, saying. "Just put these together on the table, Brett, and see what you make of them."

I turned the pieces painted side up, and fitted them together into a complete panel, joining up the painted design accurately. "It is an entire panel," I said.

"Good. Now look at the sticks a little more closely, and tell me if you notice anything peculiar about them—any particular in which they? differ from all the others."

I looked. "Two adjoining sticks," I said, "have each a small semi-circular cavity stuffed with what seems to be putty. Put together it would mean a small circular hole, perhaps a knot-hole, half an inch or so in diameter, in the panel, filled in with putty, or whatever it is."

"A knot-hole?" Hewitt asked, with particular emphasis.

"Well, no, not a knot-hole, of course, because that would go right through, and this doesn't. It is probably less than half an inch deep from the front surface."

"Anything else? Look at the whole appearance of the wood itself. Colour, for instance."

"It is certainly darker than the rest."

"So it is," He took the two pieces carrying the puttied hole, threw the rest on the heap, and addressed the landlady. "The Mr Harvey Challitt who occupied this room before Mr Kingscote, and who got into trouble for forgery, was the Mr Harvey Challitt who was himself robbed of diamonds a few months before on a staircase, wasn't he?"

"Yes, sir," Mrs Lamb replied in some bewilderment. "He certainly was that, on his own office stairs, chloroformed."

"Just so, and when they marched him away because of the forgery, Mr Kingscote changed into his rooms?"

"Yes, and very glad I was. It was bad enough to have the disgrace brought into the house, without the trouble of trying to get people to take his very rooms, and I thought—"

"Yes, yes, very awkward, very awkward!" Hewitt interrupted rather impatiently. "The man who took the rooms on Monday, now—you'd never seen him before, had you?"

"No, sir."

"Then is that anything like him?" Hewitt held a cabinet photograph before her.

"Why—why—law, yes, that's him!"

Hewitt dropped the photograph back into his breast pocket with a contented "Um," and picked up his hat. "I think we may soon be able to find that young gentleman for you, Mrs Lamb. He is not a very respectable young gentleman, and perhaps you are well rid of him, even as it is. Come, Brett," he added, "the day hasn't been wasted, after all."

We made towards the nearest telegraph office. On the way I said, "That puttied-up hole in the piece of wood seems to have influenced you. Is it an important link?"

"Well—yes," Hewitt answered, "it is. But all those other pieces are important, too."

"But why?"

"Because there are no holes in them." He looked quizzically at my wondering face, and laughed aloud. "Come," he said, "I won't puzzle you much longer. Here is the post-office. I'll send my wire, and then we'll go and dine at Luzatti's."

He sent his telegram, and we cabbed it to Luzatti's. Among actors, journalists, and others who know town and like a good dinner, Luzatti's is well known. We went upstairs for the sake of quietness, and took a table standing alone in a recess just inside the door. We ordered our dinner, and then Hewitt began:

"Now tell me what your conclusion is in this matter of the Ivy Cottage murder."

"Mine? I haven't one. I'm sorry I'm so very dull, but I really haven't."

"Come, I'll give you a point. Here is the newspaper account (torn sacrilegiously from my scrap-book for your benefit) of the robbery perpetrated on Harvey Challitt a few months before his forgery. Read it."

"Oh, but I remember the circumstances very well. He was carrying two packets of diamonds belonging to his firm downstairs to the office of another firm of diamond merchants on the ground-floor. It was a quiet time in the day, and halfway down he was seized on a dark landing, made insensible by chloroform, and robbed of the diamonds—five or six thousand pounds' worth altogether, of stones of various smallish individual values up to thirty pounds or so. He lay unconscious on the landing till one of the partners, noticing that he had been rather long gone, followed and found him. That's all, I think."

"Yes, that's all. Well, what do you make of it?"

"I'm afraid I don't quite see the connection with this case."

"Well, then, I'll give you another point. The telegram I've just sent releases information to the police, in consequence of which they will probably apprehend Harvey Challitt and his confederate Henry Gillard, alias Jones, for the murder of Gavin Kingscote. Now, then."

"Challitt! But he's in gaol already."

"Tut, tut, consider. Five years' penal was his dose, although for the first offence, because the forgery was of an extremely dangerous sort. You left Chelsea over three years ago yourself, and you told me that his difficulty occurred a year before. That makes four years, at least. Good conduct in prison brings a man out of a five year's sentence in that time or a little less, and, as a matter of fact, Challitt was released rather more than a week ago."

"Still, I'm afraid I don't see what you are driving at."

"Whose story is this about the diamond robbery from Harvey Challitt?"

"His own."

"Exactly. His own. Does his subsequent record make him look like a person whose stories are to be accepted without doubt or question?"

"Why, no. I think I see—no, I don't. You mean he stole them himself? I've a sort of dim perception of your drift now, but still I can't fix it. The whole thing's too complicated."

"It is a little complicated for a first effort, I admit, so I will tell you. This is the story. Harvey Challitt is an artful young man, and decides on a theft of his firm's diamonds. He first prepares a hiding-place somewhere near the stairs of his office, and when the opportunity arrives he puts the stones away, spills his chloroform, and makes a smell—possibly sniffs some, and actually goes off on the stairs, and the whole thing's done. He is carried into the office—the diamonds are gone. He tells of the attack on the stairs, as we have heard, and he is believed. At a suitable opportunity he takes his plunder from the hiding-place, and goes home to his lodgings. What is he to do with those diamonds? He can't sell them yet, because the robbery is publicly notorious, and all the regular jewel buyers know him.

"Being a criminal novice, he doesn't know any regular receiver of stolen goods, and if he did would prefer to wait and get full value by an ordinary sale. There will always be a danger of detection so long as the stones are not securely hidden, so he proceeds to hide them. He knows that if any suspicion were aroused his rooms would be searched in every likely place, so he looks for an unlikely place. Of course, he thinks of taking out a panel and hiding them behind that. But the idea is so obvious that it won't do; the police would certainly take those panels out to look behind them. Therefore he determines to hide them in the panels. See here"—he took the two pieces of wood with the filled hole from his tail pocket and opened his penknife—the putty near the surface is softer than that near the bottom of the hole; two different lots of putty, differently mixed, perhaps, have been used, therefore, presumably, at different times.

"But to return to Challitt. He makes holes with a centre-bit in different places on the panels, and in each hole he places a diamond, embedding it carefully in putty. He smooths the surface carefully flush with the wood, and then very carefully paints the place over, shading off the paint at the edges so as to leave no signs of a patch. He doesn't do the whole job at once, creating a noise and a smell of paint, but keeps on steadily, a few holes at a time, till in a little while the whole wainscoting is set with hidden diamonds, and every panel is apparently sound and whole."

"But, then—there was only one such hole in the whole lot."

Just so, and that very circumstance tells us the whole truth. Let me tell the story first—I'll explain the clue after. The diamonds lie hidden for a few months—he grows impatient. He wants the money, and he can't see a way of getting it. At last he determines to make a bolt and go abroad to sell his plunder. He knows he will want money for expenses, and that he may not be able to get rid of his diamonds at once. He also expects that his suddenly going abroad while the robbery is still in people's minds will bring suspicion on him in any case, so, in for a penny in for a pound, he commits a bold forgery, which, had it been successful, would have put him in funds and enabled him to leave the country with the stones. But the forgery is detected, and he is haled to prison, leaving the diamonds in their wainscot setting.

"Now we come to Gavin Kingscote. He must have been a shrewd fellow—the sort of man that good detectives are made of. Also he must have been pretty unscrupulous. He had his suspicions about the genuineness of the diamond robbery, and kept his eyes open. What indications he had to guide him we don't know, but living in the same house a sharp fellow on the look—out would probably see enough. At any rate, they led him to the belief that the diamonds were in the thief's rooms, but not among his movables, or they would have been found after the arrest. Here was his chance. Challitt was out of the way for years, and there was plenty of time to take the house to pieces if it were necessary. So he changed into Challitt's rooms.

"How long it took him to find the stones we shall never know. He probably tried many other places first, and, I expect, found the diamonds at last by pricking over the panels with a needle. Then came the problem of getting them out without attracting attention. He decided not to trust to the needle, which might possibly leave a stone or two undiscovered, but to split up each panel carefully into splinters so as to leave no part unexamined. Therefore he took measurements, and had a number of panels made by a joiner of the exact size and pattern of those in the room, and announced to his landlady his intention of painting her panels with a pretty design. This to account for the wet paint, and even for the fact of a panel being out of the wall, should she chance to bounce into the room at an awkward moment. All very clever, eh?"

"Very."

"Ah, he was a smart man, no doubt. Well, he went to work, taking out a panel, substituting a new one, painting it over, and chopping up the old one on the quiet, getting rid of the splinters out of doors when the booty had been extracted. The decoration progressed and the little heap of diamonds grew. Finally, he came to the last panel, but found that he had used all his new panels and hadn't one left for a substitute. It must have been at some time when it was difficult to get hold of the joiner—Bank Holiday, perhaps, or Sunday, and he was impatient. So he scraped the paint off, and went carefully over every part of the surface—experience had taught him by this that all the holes were of the same sort—and found one diamond. He took it out, refilled the hole with putty, painted the old panel and put it back. These are pieces of that old panel—the only old one of the lot.

"Nine men out of ten would have got out of the house as soon as possible after the thing was done, but he was a cool hand and stayed. That made the whole thing look a deal more genuine than if he had unaccountably cleared out as soon as he had got his room nicely decorated. I expect the original capital for those Stock Exchange operations we heard of came out of those diamonds. He stayed as long as suited him, and left when he set up housekeeping with a view to his wedding. The rest of the story is pretty plain. You guess it, of course?"

"Yes," I said, "I think I can guess the rest, in a general sort of way—except as to one or two points."

"It's all plain—perfectly. See here! Challitt, in gaol, determines to get those diamonds when he comes out. To do that without being suspected it will be necessary to hire the room. But he knows that he won't be able to do that himself, because the landlady, of course, knows him, and won't have an ex-convict in the house. There is no help for it; he must have a confederate, and share the spoil. So he makes the acquaintance of another convict, who seems a likely man for the job, and whose sentence expires about the same time as his own. When they come out, he arranges the matter with this confederate, who is a well-mannered (and pretty well-known) housebreaker, and the latter calls at Mrs Lamb's house to look for rooms. The very room itself happens to be to let, and of course it is taken, and Challitt (who is the invalid cousin) comes in at night muffled and unrecognizable.

"The decoration on the panel does not alarm them, because, of course, they suppose it to have been done on the old panels and over the old paint. Challitt tries the spots where diamonds were left—there are none—there is no putty even. Perhaps, think they, the panels have been shifted and interchanged in the painting, so they set to work and split them all up as we have seen, getting more desperate as they go on. Finally they realize that they are done, and clear out, leaving Mrs Lamb to mourn over their mischief.

"They know that Kingscote is the man who has forestalled them, because Gillard (or Jones), in his chat with the landlady, has heard all about him and his painting of the panels. So the next night they set off for Finchley. They get into Kingscote's garden and watch him let Campbell out. While he is gone, Challitt quietly steps through the French window into the smoking-room, and waits for him, Gillard remaining outside.

"Kingscote returns, and Challitt accuses him of taking the stones. Kingscote is contemptuous—doesn't care for Challitt, because he knows he is powerless, being the original thief himself; besides, knows there is no evidence, since the diamonds are sold and dispersed long ago. Challitt offers to divide the plunder with him—Kingscote laughs and tells him to go; probably threatens to throw him out, Challitt being the smaller man. Gillard, at the open window, hears this, steps in behind, and quietly knocks him on the head. The rest follows as a matter of course. They fasten the window and shutters, to exclude observation; turn over all the drawers, etc., in case the jewels are there; go to the best bedroom and try there, and so on. Failing (and possibly being disturbed after a few hours' search by the noise of the acquisitive gardener), Gillard, with the instinct of an old thief, determines they shan't go away with nothing, so empties Kingscote's pockets and takes his watch and chain and so on. They go out by the front door and shut it after them. Voilà tout."

I was filled with wonder at the prompt ingenuity of the man who in these few hours of hurried inquiry could piece together so accurately all the materials of an intricate and mysterious affair such as this; but more, I wondered where and how he had collected those materials.

"There is no doubt, Hewitt," I said, "that the accurate and minute application of what you are pleased to call your common sense has become something very like an instinct with you. What did you deduce from? You told me your conclusions from the examination of Ivy Cottage, but not how you arrived at them."

"They didn't leave me much material downstairs, did they? But in the bedroom, the two drawers which the thieves found locked were ransacked—opened probably with keys taken from the dead man. On the floor I saw a bent French nail; here it is. You see, it is twice bent at right angles, near the head and near the point, and there is the faint mark of the pliers that were used to bend it. It is a very usual burglars' tool, and handy in experienced hands to open ordinary drawer locks. Therefore, I knew that a professional burglar had been at work. He had probably fiddled at the drawers with the nail first, and then had thrown it down to try the dead man's keys.

"But I knew this professional burglar didn't come for a burglary, from several indications. There was no attempt to take plate, the first thing a burglar looks for. Valuable clocks were left on mantelpieces, and other things that usually go in an ordinary burglary were not disturbed. Notably, it was to be observed that no doors or windows were broken, or had been forcibly opened; therefore, it was plain that the thieves had come in by the French window of the smoking-room, the only entrance left open at the last thing. Therefore, they came in, or one did, knowing that Mr Kingscote was up, and being quite willing—presumably anxious—to see him. Ordinary burglars would have waited till he had retired, and then could have got through the closed French window as easily almost as if it were open, notwithstanding the thin wooden shutters, which would never stop a burglar for more than five minutes. Being anxious to see him, they—or again, one of them—presumably knew him. That they had come to get something was plain, from the ransacking. As, in the end, they did steal his money and watch, but did not take larger valuables, it was plain that they had no bag with them—which proves not only that they had not come to burgle, for every burglar takes his bag, but that the thing they came to get was not bulky. Still, they could easily have removed plate or clocks by rolling them up in a table-cover or other wrapper, but such a bundle, carried by well—dressed men, would attract attention—therefore it was probable that they were well dressed. Do I make it clear?"

"Quite—nothing seems simpler now it is explained—that's the way with difficult puzzles."

"There was nothing more to be got at the house. I had already in my mind the curious coincidence that the panels at Chelsea had been broken the very night before that of the murder, and determined to look at them in any case. I got from you the name of the man who had lived in the panelled room before Kingscote, and at once remembered it (although I said nothing about it) as that of the young man who had been chloroformed for his employer's diamonds. I keep things of that sort in my mind, you see—and, indeed, in my scrap-book. You told me yourself about his imprisonment, and there I was with what seemed now a hopeful case getting into a promising shape.

"You went on to prevent any setting to rights at Chelsea, and I made enquiries as to Challitt. I found he had been released only a few days before all this trouble arose, and I also found the name of another man who was released from the same establishment only a few days earlier. I knew this man (Gillard) well, and knew that nobody was a more likely rascal for such a crime as that at Finchley. On my way to Chelsea I called at my office, gave my clerk certain instructions, and looked up my scrap-book. I found the newspaper account of the chloroform business, and also a photograph of Gillard—I keep as many of these things as I can collect. What I did at Chelsea you know. I saw that one panel was of old wood and the rest new. I saw the hole in the old panel, and I asked one or two questions. The case was complete."

We proceeded with our dinner. Presently I said: "It all rests with the police now, of course?"

"Of course. I should think it very probable that Challitt and Gillard will be caught. Gillard, at any rate, is pretty well known. It will be rather hard on the surviving Kingscote, after engaging me, to have his dead brother's diamond transactions publicly exposed as a result, won't it? But it can't be helped. Fiat justitia, of course."

"How will the police feel over this?" I asked. "You've rather cut them out, eh?"

"Oh, the police are all right. They had not the information I had, you see; they knew nothing of the panel business. If Mrs Lamb had gone to Scotland Yard instead of to the policeman on the beat, perhaps I should never have been sent for."

The same quality that caused Martin Hewitt to rank as mere "common-sense" his extraordinary power of almost instinctive deduction, kept his respect for the abilities of the police at perhaps a higher level than some might have considered justified.

We sat some little while over our dessert, talking as we sat, when there occurred one of those curious conjunctions of circumstances that we notice again and again in ordinary life, and forget as often, unless the importance of the occasion fixes the matter in the memory. A young man had entered the dining-room, and had taken his seat at a corner table near the back window. He had been sitting there for some little time before I particularly observed him. At last he happened to turn his thin, pale face in my direction, and our eyes met. It was Challitt—the man we had been talking of!

I sprang to my feet in some excitement.

"That's the man!" I cried. "Challitt!"

Hewitt rose at my words, and at first attempted to pull me back. Challitt, in guilty terror, saw that we were between him and the door, and turning, leaped upon the sill of the open window, and dropped out. There was a fearful crash of broken glass below, and everybody rushed to the window.

Hewitt drew me through the door, and we ran downstairs. "Pity you let out like that," he said, as he went. "If you'd kept quiet we could have sent out for the police with no trouble. Never mind—can't help it."

Below, Challitt was lying in a broken heap in the midst of a crowd of waiters. He had crashed through a thick glass skylight and fallen, back downward, across the back of a lounge. He was taken away on a stretcher unconscious, and, in fact, died in a week in hospital from injuries to the spine.

During his periods of consciousness he made a detailed statement, bearing out the conclusions of Martin Hewitt with the most surprising exactness, down to the smallest particulars. He and Gillard had parted immediately after the crime, judging it safer not to be seen together. He had, he affirmed, endured agonies of fear and remorse in the few days since the fatal night at Finchley, and had even once or twice thought of giving himself up. When I so excitedly pointed him out, he knew at once that the game was up, and took the one desperate chance of escape that offered. But to the end he persistently denied that he had himself committed the murder, or had even thought of it till he saw it accomplished. That had been wholly the work of Gillard, who, listening at the window and perceiving the drift of the conversation, suddenly beat down Kingscote from behind with a life-preserver.

And so Harvey Challitt ended his life at the age of twenty-six.

Gillard was never taken. He doubtless left the country, and has probably since that time become "known to the police" under another name abroad. Perhaps he has even been hanged, and if he has been, there was no miscarriage of justice, no matter what the charge against him may have been.

THE whole voyage was an unpleasant one, and Captain Mackrie, of the Anglo-Malay Company's steamship Nicobar, had at last some excuse for the ill-temper that had made him notorious and unpopular in the company's marine staff. Although the fourth and fifth mates in the seclusion of their berth ventured deeper in their search for motives, and opined that the "old man" had made a deal less out of this voyage than usual; the company having lately taken to providing its own stores; so that "makings" were gone clean and "cumshaw" (which means commission in the trading lingo of the China seas) had shrunk small indeed. In confirmation they adduced the uncommonly long face of the steward (the only man in the ship satisfied with the skipper), whom the new regulations hit with the same blow. But indeed the steward's dolor might well be credited to the short passenger list, and the unpromising aspect of the few passengers in the eyes of a man accustomed to gauge one's tip-yielding capacity a month in advance. For the steward it was altogether the wrong time of year, the wrong sort of voyage, and certainly the wrong sort of passengers. So that doubtless the confidential talk of the fourth and fifth officers was mere youthful scandal. At any rate, the captain had prospect of a good deal in private trade home, for he had been taking curiosities and Japanese oddments aboard (plainly for sale in London) in a way that a third steward would have been ashamed of, and which, for a captain, was a scandal and an ignominy; and he had taken pains to insure well for the lot. These things the fourth and fifth mates often spoke of, and more than once made a winking allusion to, in the presence of the third mate and the chief engineer, who laughed and winked too, and sometimes said as much to the second mate, who winked without laughing; for of such is the tittle-tattle of shipboard.

The Nicobar was bound home with few passengers, as I have said, a small general cargo, and gold bullion to the value of £200,000—the bullion to be landed at Plymouth, as usual. The presence of this bullion was a source of much conspicuous worry on the part of the second officer, who had charge of the bullion-room. For this was his first voyage on his promotion from third officer, and the charge of £200,000 worth of gold bars was a thing he had not been accustomed to. The placid first officer pointed out to him that this wasn't the first shipment of bullion the world had ever known, by a long way, nor the largest. Also that every usual precaution was taken, and the keys were in the captain's cabin; so that he might reasonably be as easy in his mind as the few thousand other second officers who had had charge of hatches and special cargo since the world began. But this did not comfort Brasyer. He fidgeted about when off watch, considering and puzzling out the various means by which the bullion-room might be got at, and fidgeted more when on watch, lest somebody might be at that moment putting into practice the ingenious dodges he had thought of. And he didn't keep his fears and speculations to himself. He bothered the first officer with them, and when the first officer escaped he explained the whole thing at length to the third officer.

"Can't think what the company's about," he said on one such occasion to the first mate, "calling a tin-pot bunker like that a bullion-room."

"Skittles!" responded the first mate, and went on smoking.

"Oh, that's all very well for you who aren't responsible," Brasyer went on, "but I'm pretty sure something will happen some day; if not on this voyage on some other. Talk about a strong room! Why, what's it made of?"

"Three-eighths boiler plate."

"Yes, three-eighths boilerplate—about as good as a sixpenny tin money box. Why, I'd get through that with my grandmother's scissors!"

"All right; borrow 'em and get through. I would if I had a grandmother."

"There it is down below there out of sight and hearing, nice and handy for anybody who likes to put in a quiet hour at plate cutting from the coal bunker next door—always empty, because it's only a seven-ton bunker, not worth trimming. And the other side's against the steward's pantry. What's to prevent a man shipping as steward, getting quietly through while he's supposed to be bucketing about among his slops and his crockery, and strolling away with the plunder at the next port? And then there's the carpenter. He's always messing about somewhere below, with a bag full of tools. Nothing easier than for him to make a job in a quiet corner, and get through the plates."

"But then what's he to do with the stuff when he's got it? You can't take gold ashore by the hundredweight in your boots."

"Do with it. Why, dump it, of course. Dump it overboard in a quiet port and mark the spot. Come to that, he could desert clean at Port Said—what easier place?—and take all he wanted. You know what Port Said's like. Then there are the firemen—oh, anybody can do it!" And Brasyer moved off to take another peep under the hatchway.

The door of the bullion-room was fastened by one central patent lock and two padlocks, one above and one below the other lock. A day or two after the conversation recorded above, Brasyer was carefully examining and trying the lower of the padlocks with a key, when a voice immediately behind him asked sharply, "Well, sir, and what are you up to with that padlock?"

Brasyer started violently and looked round. It was Captain Mackrie.

"There's—that is—I'm afraid these are the same sort of padlocks as those in the carpenter's stores," the second mate replied, in a hurry of explanation. "I—I was just trying, that's all; I'm afraid the keys fit."

"Just you let the carpenter take care of his own stores, will you, Mr. Brasyer? There's a Chubb's lock there as well as the padlocks, and the key of that's in my cabin, and I'll take care doesn't go out of it without my knowledge. So perhaps you'd best leave off experiments till you're asked to make 'em, for your own sake. That's enough now," the captain added, as Brasyer appeared to be ready to reply; and he turned on his heel and made for the steward's quarters.

Brasyer stared after him ragefully. "Wonder what you want down here," he muttered under his breath. "Seems to me one doesn't often see a skipper as thick with the steward as that." And he turned off growling towards the deck above.

"Hanged if I like that steward's pantry stuck against the side of the bullion-room," he said later in the day to the first officer. "And what does a steward want with a lot of boiler-maker's tools aboard? You know he's got them."

"In the name of the prophet, rats!" answered the first mate, who was of a less fussy disposition. "What a fatiguing creature you are, Brasyer! Don't you know the man's a boiler-maker by regular trade, and has only taken to stewardship for the last year or two? That sort of man doesn't like parting with his tools, and as he's a widower, with no home ashore, of course he has to carry all his traps aboard. Do shut up, and take your proper rest like a Christian. Here, I'll give you a cigar; it's all right—Burman; stick it in your mouth, and keep your jaw tight on it."

But there was no soothing the second officer. Still he prowled about the after orlop deck, and talked at large of his anxiety for the contents of the bullion-room. Once again, a few days later, as he approached the iron door, he was startled by the appearance of the captain coming, this time, from the steward's pantry. He fancied he had heard tapping, Brasyer explained, and had come to investigate. But the captain turned him back with even less ceremony than before, swearing he would give charge of the bullion-room to another officer if Brasyer persisted in his eccentricities. On the first deck the second officer was met by the carpenter, a quiet, sleek, soft-spoken man, who asked him for the padlock and key he had borrowed from the stores during the week. But Brasyer put him off, promising to send it back later. And the carpenter trotted away to a job he happened to have, singularly enough, in the hold, just under the after orlop deck, and below the floor of the bullion-room.

As I have said, the voyage was in no way a pleasant one. Everywhere the weather was at its worst, and scarce was Gibraltar passed before the Lascars were shivering in their cotton trousers, and the Seedee boys were buttoning tight such old tweed jackets as they might muster from their scanty kits. It was January. In the Bay the weather was tremendous, and the Nicobar banged and shook and pitched distractedly across in a howling world of thunderous green sea, washed within and without, above and below. Then, in the Chops, as night fell, something went, and there was no more steerageway, nor, indeed, anything else but an aimless wallowing. The screw had broken.

The high sea had abated in some degree, but it was still bad. Such sail as the steamer carried, inadequate enough, was set, and shift was made somehow to worry along to Plymouth—or to Falmouth if occasion better served—by that means. And so the Nicobar beat across the Channel on a rather better, though anything but smooth, sea, in a black night, made thicker by a storm of sleet, which turned gradually to snow as the hours advanced.

The ship laboured slowly ahead, through a universal blackness that seemed to stifle. Nothing but a black void above, below, and around, and the sound of wind and sea; so that one coming before a deck-light was startled by the quiet advent of the large snowflakes that came like moths as it seemed from nowhere. At four bells—two in the morning—a foggy light appeared away on the starboard bow—it was the Eddystone light—and an hour or two later, the exact whereabouts of the ship being a thing of much uncertainty, it was judged best to lay her to till daylight. No order had yet been given, however, when suddenly there were dim lights over the port quarter, with a more solid blackness beneath them. Then a shout and a thunderous crash, and the whole ship shuddered, and in ten seconds had belched up every living soul from below. The Nicobar's voyage was over—it was a collision.

The stranger backed off into the dark, and the two vessels drifted apart, though not till some from the Nicobar had jumped aboard the other. Captain Mackrie's presence of mind was wonderful, and never for a moment did he lose absolute command of every soul on board. The ship had already begun to settle down by the stern and list to port. Life-belts were served out promptly. Fortunately there were but two women among the passengers, and no children. The boats were lowered without a mishap, and presently two strange boats came as near as they dare from the ship (a large coasting steamer, it afterwards appeared) that had cut into the Nicobar. The last of the passengers were being got off safely, when Brayser, running anxiously to the captain, said:—

"Can't do anything with that bullion, can we, sir? Perhaps a box or two—"

"Oh, damn the bullion!" shouted Captain Mackrie. "Look after the boat, sir, and get the passengers off. The insurance companies can find the bullion for themselves."

But Brasyer had vanished at the skipper's first sentence. The skipper turned aside to the steward as the crew and engine-room staff made for the remaining boats, and the two spoke quietly together. Presently the steward turned away as if to execute an order, and the skipper continued in a louder tone:—

"They're the likeliest stuff, and we can but drop 'em, at worst. But be slippy—she won't last ten minutes."

She lasted nearly a quarter of an hour. By that time, however, everybody was clear of her, and the captain in the last boat was only just near enough to see the last of her lights as she went down.

THE day broke in a sulky grey, and there lay the Nicobar, in ten fathoms, not a mile from the shore, her topmasts forlornly visible above the boisterous water. The sea was rough all that day, but the snow had ceased, and during the night the weather calmed considerably. Next day Lloyd's agent was steaming about in a launch from Plymouth, and soon a salvage company's tug came up and lay to by the emerging masts. There was every chance of raising the ship as far as could be seen, and a diver went down from the salvage tug to measure the breach made in the Nicobar's side, in order that the necessary oak planking or sheeting might be got ready for covering the hole, preparatory to pumping and raising. This was done in a very short time, and the necessary telegrams having been sent, the tug remained in its place through the night, and prepared for the sending down of several divers on the morrow to get out the bullion as a commencement.

Just at this time Martin Hewitt happened to be engaged on a case of some importance and delicacy on behalf of Lloyd's Committee, and was staying for a few days at Plymouth. He heard the story of the wreck, of course, and speaking casually with Lloyd's agent as to the salvage work just beginning, he was told the name of the salvage company's representative on the tug, Mr. Percy Merrick—a name he immediately recognised as that of an old acquaintance of his own. So that on the day when the divers were at work in the bullion-room of the sunken Nicobar, Hewitt gave himself a holiday, and went aboard the tug about noon.

Here he found Merrick, a big, pleasant man of thirty-eight or so. He was very glad to see Hewitt, but was a great deal puzzled as to the results of the morning's work on the wreck. Two cases of gold bars were missing.

"There was £200,000 worth of bullion on board," he said, "that's plain and certain. It was packed in forty cases, each of £5,000 value. But now there are only thirty-eight cases! Two are gone clearly. I wonder what's happened?"

"I suppose your men don't know anything about it?" asked Hewitt.

"No, they're all right. You see, it's impossible for them to bring anything up without its being observed, especially as they have to be unscrewed from their diving-dresses here on deck. Besides, bless you, I was down with them."

"Oh! Do you dive yourself, then?"

"Well, I put the dress on sometimes, you know, for any such special occasion as this. I went down this morning. There was no difficulty in getting about on the vessel below, and I found the keys of the bullion-room just where the captain said I would, in his cabin. But the locks were useless, of course, after being a couple of days in salt water. So we just burgled the door with crowbars, and then we saw that we might have done it a bit more easily from outside. For that coasting-steamer cut clean into the bunker next the bullion-room, and ripped open the sheet of boiler-plate dividing them."

"The two missing cases couldn't have dropped out that way, of course?"

"Oh, no. We looked, of course, but it would have been impossible. The vessel has a list the other way—to starboard—and the piled cases didn't reach as high as the torn part. Well, as I said, we burgled the door, and there they were, thirty-eight sealed bullion cases, neither more nor less, and they're down below in the after-cabin at this moment. Come and see."

Thirty-eight they were; pine cases bound with hoop-iron and sealed at every joint, each case about eighteen inches by a foot, and six inches deep. They were corded together, two and two, apparently for convenience of transport.

"Did you cord them like this yourself?" asked Hewitt.

"No, that's how we found 'em. We just hooked 'em on a block and tackle, the pair at a time, and they hauled 'em up here aboard the tug."

"What have you done about the missing two—anything?"

"Wired off to headquarters, of course, at once. And I've sent for Captain Mackrie—he's still in the neighbourhood, I believe—and Brasyer, the second officer, who had charge of the bullion-room. They may possibly know something. Anyway, one thing's plain. There were forty cases at the beginning of the voyage, and now there are only thirty-eight."

There was a pause; and then Merrick added, "By the bye, Hewitt, this is rather your line, isn't it? You ought to look up these two cases."

Hewitt laughed. "All right," he said; "I'll begin this minute if you'll commission me."

"Well," Merrick replied slowly, "of course I can't do that without authority from headquarters. But if you've nothing to do for an hour or so there is no harm in putting on your considering cap, is there? Although, of course, there's nothing to go upon as yet. But you might listen to what Mackrie and Brasyer have to say. Of course I don't know, but as it's a £10,000 question probably it might pay you, and if you do see your way to anything I'd wire and get you Commissioned at once."

There was a tap at the door and Captain Mackrie entered. "Mr. Merrick?" he said interrogatively, looking from one to another.

"That's myself, sir," answered Merrick.

"I'm Captain Mackrie, of the Nicobar. You sent for me, I believe. Something wrong with the bullion I'm told, isn't it?"

Merrick explained matters fully. "I thought perhaps you might be able to help us, Captain Mackrie. Perhaps I have been wrongly informed as to the number of cases that should have been there?"

"No; there were forty right enough. I think though—perhaps I might be able to give you a sort of hint "—and Captain Mackrie looked hard at Hewitt.

"This is Mr. Hewitt, Captain Mackrie," Merrick interposed. "You may speak as freely as you please before him. In fact, he's sort of working on the business, so to speak."

"Well," Mackrie said, "if that's so, speaking between ourselves, I should advise you to turn your attention to Brasyer. He was my second officer, you know, and had charge of the stuff."

"Do you mean," Hewitt asked, "that Mr. Brasyer might give us some useful information?"

Mackrie gave an ugly grin. "Very likely he might," he said, "if he were fool enough. But I don't think you'd get much out of him direct. I meant you might watch him."

"What, do you suppose he was concerned in any way with the disappearance of this gold?"

"I should think—speaking, as I said before, in confidence and between ourselves—that it's very likely indeed. I didn't like his manner all through the voyage."

"Why?"

"Well, he was so eternally cracking on about his responsibility, and pretending to suspect the stokers and the carpenter, and one person and another, of trying to get at the bullion cases—that that alone was almost enough to make one suspicious. He protested so much, you see. He was so conscientious and diligent himself, and all the rest of it, and everybody else was such a desperate thief, and he was so sure there would be some of that bullion missing some day that—that—well, I don't know if I express his manner clearly, but I tell you I didn't like it a bit. But there was something more than that. He was eternally smelling about the place, and peeping in at the steward's pantry—which adjoins the bullion-room on one side, you know—and nosing about in the bunker on the other side. And once I actually caught him fitting keys to the padlocks—keys he'd borrowed from the carpenter's stores. And every time his excuse was that he fancied he heard somebody else trying to get in to the gold, or something of that sort; every time I caught him below on the orlop deck that was his excuse—happened to have heard something or suspected something or somebody every time. Whether or not I succeed in conveying my impressions to you, gentlemen, I can assure you that I regarded his whole manner and actions as very suspicious throughout the voyage, and I made up my mind I wouldn't forget it if by chance anything did turn out wrong. Well, it has, and now I've told you what I've observed. It's for you to see if it will lead you anywhere."

"Just so," Hewitt answered. "But let me fully understand. Captain Mackrie. You say that Mr. Brasyer had charge of the bullion-room, but that he was trying keys on it from the carpenter's stores. Where were the legitimate keys then?"

"In my cabin. They were only handed out when I knew what they were wanted for. There was a Chubb's lock between the two padlocks, but a duplicate wouldn't have been hard for Brasyer to get. He could easily have taken a wax impression of my key when he used it at the port where we took the bullion aboard."

"Well, and suppose he had taken these boxes, where do you think he would keep them?"

Mackrie shrugged his shoulders and smiled. "Impossible to say," he replied. "He might have hidden 'em somewhere on board, though I don't think that's likely. He'd have had a deuce of a job to land them at Plymouth, and would have had to leave them somewhere while he came on to London. Bullion is always landed at Plymouth, you know, and if any were found to be missing, then the ship would be overhauled at once, every inch of her; so that he'd have to get his plunder ashore somehow before the rest of the gold was unloaded—almost impossible. Of course, if he's done that it's somewhere below there now, but that isn't likely. He'd be much more likely to have 'dumped' it—dropped it overboard at some well-known spot in a foreign port, where he could go later on and get it. So that you've a deal of scope for search, you see. Anywhere under water from here to Yokohama;" and Captain Mackrie laughed.

Soon afterward he left, and as he was leaving a man knocked at the cabin door and looked in to say that Mr. Brasyer was on board. "You'll be able to have a go at him now," said the captain. "Good-day."

"There's the steward of the Nicobar there too, sir," said the man after the captain had gone, "and the carpenter."

"Very well, we'll see Mr. Brasyer first," said Merrick, and the man vanished. "It seems to have got about a bit," Merrick went on to Hewitt. "I only sent for Brasyer, but as these others have come, perhaps they've got something to tell us."

Brasyer made his appearance, overflowing with information. He required little assurance to encourage him to speak openly before Hewitt, and he said again all he had so often said before on board the Nicobar. The bullion-room was a mere tin box, the whole thing was as easy to get at as anything could be, he didn't wonder in the least at the loss—he had prophesied it all along.

The men whose movements should be carefully watched, he said, were the captain and the steward. "Nobody ever heard of a captain and a steward being so thick together before," he said. "The steward's pantry was next against the bullion-room, you know, with nothing but that wretched bit of three-eighths boiler plate between. You wouldn't often expect to find the captain down in the steward's pantry, would you, thick as they might be. Well, that's where I used to find him, time and again. And the steward kept boiler-makers' tools there! That I can swear to. And he's been a boiler-maker, so that, likely as not, he could open a joint somewhere and patch it up again neatly so that it wouldn't be noticed. He was always messing about down there in his pantry, and once I distinctly heard knocking there, and when I went down to see, whom should I meet? Why, the skipper, coming away from the place himself, and he bully-ragged me for being there and sent me on deck. But before that he bully-ragged me because I had found out that there were other keys knocking about the place that fitted the padlocks on the bullion-room door. Why should he slang and threaten me for looking after these things and keeping my eye on the bullion-room, as was my duty? But that was the very thing that he didn't like. It was enough for him to see me anxious about the gold to make him furious. Of course his character for meanness and greed is known all through the company's service—he'll do anything to make a bit."

"But have you any positive idea as to what has become of the gold?"

"Well," Brasyer replied, with a rather knowing air, "I don't think they've dumped it."

"Do you mean you think it's still in the vessel—hidden somewhere?"

"No, I don't. I believe the captain and the steward took it ashore, one case each, when we came off in the boats."

"But wouldn't that be noticed?"