RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

The Saturday Evening Post, 28 August 1909, with "In the Wireless Room")

THE night was black and hot, as only an equatorial night can be. It was so black and hot that the low- swung stars seemed a stippling of fire on the arching crownsheet of an illimitable furnace-box. The sea itself, unwrinkled as an inkwell, was of an equal blackness. A gentle shower of cinders rained on the canvas awnings that roofed the bridge deck. Electric fans droned from open doorways, purring plaintively through the gloom where the deck lights had long since gone out, for it was well past midnight.

A sense of ease and indolence hung over the ship, with her muffled engine pulse and her quiet and orderly decks. The heat drove all thought of cabin berths out of our heads. So the four of us sat and smoked in the new wireless room that backed the captain's quarters and still smelt of white-lead paint. Four tall glasses stood on the apparatus table where the green-shaded Lamp swung low over its frustum of light. Sometimes we talked, and sometimes we sat there in silent and Buddhistic vacuity. Through the outer gloom of this chamber, during our more cataleptic periods, showed the intermittent cherry glow of cigar ends. Sometimes a match flare would pick out the machinery of the wireless, polished like surgical instruments, in a momentary scattering of high lights. Sometimes it showed a beaded human face, mournfully thoughtful and placid, and poignantly isolated in its momentary irradiation.

Beckmire, the ship's doctor, self-contained, incredibly thin and prematurely gray, sat in the open door with his hands linked above his head. I sat next to him. The wireless operator, Wister, lounged against his work-table in the full current of the electric fan. Opposite him again sat the captain, leaning bulkily back until his head rested against the cabin wall, listening to the operator's account of a Scotch skipper who after his tenth glass mistook an iceberg for a Flying Dutchman. Then a step hurried lightly across the deck, and I noticed Beckmire's startled movement as a figure appeared in the door beside him. We looked at this figure resentfully; it was very late, but we preferred losing our beauty sleep in peace.

"Did you ring, sir?" asked the figure. We all knew, the next moment, that it was nothing more than the captain's steward.

"I did not ring, William," promptly answered the captain. The steward murmured "Very well, sir," and withdrew. We turned back to our talk and cigars and tail glasses. Whereupon the captain himself told the story of a signal-box which had rung of itself—and eviscerated the situation by explaining just how the wires had been crossed. We were leaning back in silent and leisured resentment of this undramatic disembowelment when, for the second time, the captain's steward came to the door. "You rang, sir?" he said.

"No one rang," retorted the captain. Then he turned and called the departing steward back. "What made you think I rang?" he demanded. The thing was becoming a little creepy. I began to see what Beckmire had meant when he said no one was immovably sane after midnight.

"I heard the bell, sir, I thought," the steward answered. I imagined he was a bit flustered, by the tone of his voice.

"And you still think so?" asked the captain.

"Yes, sir; I still think so," maintained the steward, after a moment or two of silence.

"But there are four people here who know that no one so much as touched a bell," argued the captain.

"I'm sorry, sir," said the steward. And again he left us, and again we sat and talked and watched the night grow old.

Each of us, I think, swung about a little uneasily when, ten minutes later, a figure in white passed the open door. It was the captain's steward once more. This time, however, he did not venture to come in. He circled off from us, like a colt shying at a paper. He would have retreated resignedly and discreetly below- deck, I suppose, but the ship's master called him back sharply.

"Give us some more light there," said the captain to the wireless operator. Then he turned to the steward as the unshaded electrics flooded the room. "And so you think you heard that bell ring again?" he asked.

"Yes, sir," said the steward with conviction. "And you consulted the indicator?"

"Yes, sir. It showed this cabin, sir, the same as before."

The captain looked at us appealingly. Some one stirred uneasily. I think it was Beckmire, the ship's doctor.

"But not one of us so much as went near a bell," I corroborated.

"You being the only one up on the ship," began the steward.

"Where is the bell in this cabin?" demanded the practical-minded captain. The steward crossed the room until he stood directly behind the commanding officer's chair, where a wall map hung. He lifted the map and showed an electric push- button.

The captain laughed, and a moment later we all joined him. It was very simple. His head had rested on the push-button hidden by the map each time he had leaned back in his chair. "And there's another mystery gone," he derided, with a glance at Beckmire. "And gone the way most of them go."

"Yes, most of them!" Beckmire said under his breath as the captain ordered more Scotch and ice, and we all sat down again. The night was still hot and soundless, yet for all its heat there was something feminine and melting and softly mysterious in that tepid sea air of the tropics that fanned our faces. Through it I could sniff stray fumes of ammonia gas from the ice-plant below- decks. The operator sighed audibly as he got up to adjust his light shades. A vague melancholy, a new and disquieting loneliness of spirit, seemed to settle about him, about each man in that little group. A bell sounded out of the ship's bow, slow- noted and mournful, and was answered by another bell farther aft. It was then that the wireless operator turned to the ship's doctor.

"Do you believe in ghosts?" he asked.

"I've got a Bolivian with D.T.'s down below who'll answer that for me," was the doctor's quiet retort. "He's seeing 'em now by the dozens!"

"But actual ghosts—er—objective ghosts?" I foolishly inquired.

The doctor continued to smoke for a minute or two.

"Isn't that word rather a stupid one?" he said at last. "Rather too generic, I mean, for times when we talk with stuff like this!" And he waved a hand indolently toward the apparatus table.

"But don't you somehow believe in the persistence of personality after what we call death?" I had the effrontery to ask, for something about that veiled and nomadic face, with its cavernous shadows in the half-light, made me feel his answer would be worth while.

"Yes," he said; "I do. I've lived long enough, I think, to believe in anything."

"Just cross your wires," ejaculated the captain, "and you'll always get your ghosts!"

"Yes," conceded Beckmire a little wearily, "you've got to tune up to them, as the wireless people put it; you've got to get in tune-accord with, well, let's call it the Exceptional, or you'll never get anything out of the jumble that's about us."

"Tuning up, I s'pose, means either turning on the hysteria or piling on the drugs until you get the right pitch of pure delirium?" inquired the captain.

"Sometimes," acquiesced the doctor. "At other times it's only eyes and stomach. And at still other times it's something you can't understand any more than Columbus could understand this wireless apparatus."

"Have you ever found anything that was more than eyes and stomach when you got to the bottom of it?" the captain demanded.

"But we can't always get to the bottom of it," was Beckmire's quiet reply.

"You know what I mean. Have you steered into anything that you couldn't explain as a physiologist, on the one hand, or as a psychologist, on the other?"

"Yes," said Beckmire, "I have." And that was how he came to tell his story.

IT happened in the midwinter of 1907, on the old A Aurian liner Clotilda, began the doctor in that quiet and matter-of-fact tone which of itself seemed to translate everything he said into a world of unquestioned actuality. We made the run from Rio to New York, swinging in to Cartagena and Limón and Kingston for fruit, on company orders. The Clotilda had been a handsome ship in her day, but I'd heard something about her grounding on the Irish coast in a fog, three or four years before. Then she was renamed and put on the southern run, and I was assigned to her under Captain Goodyear, the Goodyear who died of apoplexy at Port Antonio last winter.

We were bound north, and were well up over the Line at the time I speak of. I remember I was down in my cabin that first night, and should have been asleep; but the heat was terrific. I can even recall quite distinctly how I was lying propped up on my two pillows, in the gaudiest Chinese-silk pajamas you ever clapped eyes on. On one side of me, I remember. I had the electric fan going. On the other I had my swivel reading light switched on. I'd been trying to forget the heat by a couple of hours' dip into a paper-covered copy of Huysman's À Rebours—on the idea, I suppose, that mental discomfiture can sometimes discount that of the body.

Then I heard my name called sharply. It startled me a little, it was so unexpected. When I looked up I saw Stobart, the wireless operator, at my door. He was standing there looking in at me. I swung my reading light round on him. His face wasn't any paler than usual. But I noticed that the arm he leaned against the doorjamb with was shaking a little.

"Can you come upstairs?" he said. He spoke so quietly and yet so imperatively that I at once rolled out of the bunk and stuck my toes into a pair of matting slippers.

"What's wrong?" I asked, as I pulled on a pair of ducks. This wasn't the first time he'd startled me. Our old operator, Tucker, had deserted in Rio, and we'd come north without wireless until we picked Stobart up in the roadstead off Pernambuco. He'd been operating for a couple of years in some Brazilian swamp district, and I never saw a man so hungry to get back to the frost belt. But he'd come aboard with what I'd sized up as rice malaria—hemorrhagic malaria is what a hospital intern would call it—and when he looked me up the second or third day out and asked if I could do anything to help his eyes, and I saw his yellow skin and that jaundiced-looking conjunctiva, why, my heart came right up in my throat and I said: "Yellow Jack, or Cuban dengue at the least!" Dengue is mild yellow fever, usually ambulant. And I saw a sweet time ahead of that ship, and a month or two of quarantine when it was all over. You'll say these are side issues, of course; yet they're not without interest. For his conjunctivitis, in the first place, was caused by nothing more than the wireless spark. And his chills and fever and yellowness and all that came from malaria truly enough, as the Plasmodium malaria in the blood showed me later on. A pair of blue glasses, to guard his eyes against the ultra-violet rays when he was at work, soon fixed his conjunctivitis. But he was so full of swamp malaria that I used to give him as much as thirty grains of quinine, hypodermically, to keep him up and going. And I had to fight with him about taking it, the same as I have to with that D. T. patient of mine downstairs. The quinine, you see, made his ears ring—practically deafened him.

That, of course, cut out his chances of communication. He couldn't hear the receiver phones when they were clamped right against his ears; he couldn't even hear "static" with a hornet's nest like that in his head. And Captain Goodyear was waiting for company orders before swinging up into the Caribbean, and that new operator, naturally, wanted to make good on the Clotilda. So he'd cut out the quinine when I didn't watch him. You can imagine, accordingly, what he'd suffer during one of his bad spells. "I've gone to the blackest pit and back ten times over," was the way he expressed it to me. He couldn't even crawl out of the berth, sometimes, to get to his tuner and starting lever. Sometimes, too, when he knew he'd got his call, he couldn't read the Morse because of that quinine. We carried an outfit in those days without tape, inker or bell alarm. But, as I've said before, I thought he'd been having another of his bad nights when he came down to my door that way.

"Are you sick?" I asked him, and I remember he didn't even blink when I poked my light in his face. I saw no signs of collapse or high fever. His eyes were clear enough, but something about the enlarged and iridescent pupils disturbed me.

"Come upstairs," was all he said. Then he passed one hand over his forehead—he might have had a headache or he might have been brushing a cobweb off his face. But I could never forget that gesture. It spelled utter and helpless bewilderment to me.

"Anything happened?" I asked as I followed him along a sultry alleyway of closed doors. The warm air sucked through that alleyway like the back draft from a furnace. "Yes," was all he said.

"What is it?" I demanded again. You know the tricks that equatorial heat, just plain heat, will play on you sometimes. I didn't care to paper-chase round a boat with a paranoiac on a night like that. So I asked him again what it was.

"That's what I've got to find out," he answered me as he groped his way above-deck. He was very quiet about it.

Half way up the steps that led to the bridge deck, however, he came to a stop. He stood there guardedly, with his head just above the level of the deck boards, looking carefully about. What he was looking for I couldn't in the least surmise. But I heard him take a deep breath, as though relieved, and then go quietly up the rest of the steps.

It was really a wonderful night, hot and black as velvet—you know the kind, when the stars seem so close you get to thinking you can climb to a masthead and pick 'em like oranges. And off our port bow I could see the lights of a big Royal Mailer, southward bound. And everything was as still as this deck is now. But these things didn't interest me much at the time. I was too busy resenting that nautical steeplechase young Stobart was leading me into. And I told him so, as I groped and shuffled after him along the upper deck. The lights had been doused, of course, for the sake of the man at the wheel.

I could just make out Stobart's figure as he felt his way to the wireless room. The door to this room was closed and locked. I wondered at this, just as I wondered why his station itself was unlighted. I noticed, too, that he waited for me to catch up with him before he stepped in across the narrow little coppered doorsill. I also noticed that he did not turn on his lights. I began to express my impatience at the whole proceedings, and to express it in no uncertain language.

"Wait!" he said in little more than a whisper. Then he quietly closed the cabin door and padded about in the darkness with his hands. I heard him pull what I took to be a deck chair across the boards.

"Sit down," he whispered, with a tug at my pajama sleeve. I sat down. He himself took another chair not two feet away from me.

"Well?" I inquired, wondering if the heat had gone to his head.

"I want you to wait and listen," he said in my ear so quietly that I scarcely caught the words.

"For what?" I demanded, feeling that he was making a fool of me, yet infected, in spite of myself, by the atmosphere of the place.

"That's what I want you to tell me," was Stobart's answer. I could feel his ringers on my arm. I think he meant them as a signal for quietness, as a warning to wait.

We sat there, minute after minute, listening. What we were listening for Heaven only knows, it was more than I could even guess at. I could hear the other man's breathing. It was quick and short, and not the sort a visiting physician would find especially reassuring. Then the closeness of the room and the idiocy of our postures began to get on my nerves. I felt that I'd had about enough of it.

"Turn on that fan!" I cried out irritably. Instead of answering me he caught at my arm—almost imploringly, I thought at the time. I shook his hand off with some impatience.

"Wait!" he whispered; and I can remember how his fingers tightened on my arm again. Then I leaned forward a little, close beside him, and listened. My ear, I suppose, had not been so well trained as his with its years of active work over microphonic apparatus. But I leaned forward and listened. I was charminigly well primed to scoff at anything that might happen. But I can still recall the uneasy sinking I suddenly and involuntarily felt somewhere about the pit of my stomach. For beyond the closed door, from some remoter part of the quiet deck, I felt sure I heard a sound. It was quite faint and far away, at first. But as I listened it seemed to approach us.

It was, I felt, nothing more than the sound of footsteps; but coming as it did, and at that time of night, and after the seance Stobart had put roe through, it didn't exactly seem the sound a fireman coming to shift a ventilator would make. It couldn't have been an officer turning out for his watch. Those steps seemed very methodic and unhurried. I knew they were crossing the deck, coming slowly in our direction, as we listened. I could hear them draw closer and closer. I knew they were there, just through that half inch of painted pine, as plainly as I knew the wireless operator was clutching at my arm. There was no mistake about it; no room for illusion. I could hear them. They came toward us, and then they came to a stop directly outside the closed door of the wireless room.

"There's some one there," I told him as I sat listening for the knock. But no knock came. I started to my feet.

"Wait!" Stobart was imploring almost in my ear. Still no sound came from outside. And, oddly enough, I hadn't detected any sign of passing steps, to show our visitor had turned away.

"It won't come back again." Stobart was saying. "It heard you."

"What heard me?" I asked him.

"It would have turned the knob and tried to get in," was all he answered.

"That's what knobs are for!" I blandly retorted.

"But you heard It," he said with a gasp of relief. I remember how thin his voice was and the note of triumph that rang in it.

"Of course I heard it," I told him. "What about it?" Yet I must confess that my impatience was now three parts pretense.

"But you didn't hear It go away," he maintained mysteriously.

"Then it's still there!" I proclaimed with a bit of a sneer, I'm afraid.

"Wait!" he was still whispering. I heard him take a step or two in the darkness somewhere behind me. Then he spoke again.

"Open the door quick as I turn on the light!" I heard him say. I jumped for the door the moment I heard the snap of his switch. I was only too glad to let the nervous tension explode into some sudden activity like that. In the same breath that the white light flooded the cabin I had the door open.

No one was there. I can't explain to you how much I had counted on surprising a skulking deckhand or a listening steward or even a somnambulistic passenger from below. But the deck was empty; there was nothing in sight. A breath of cooler air blew in on my face, bringing with it a disagreeable sensation of dampness. But that was all.

"What's all this rot about, anyway?" I remember suddenly calling out. I felt the need of focusing my anger on something, for I began to see the absurdity of the entire situation. "What does it mean?" I demanded.

"What's all this rot about, anyway?"

"I don't know what it means," Stobart answered very slowly and very quietly, as he stood looking through the open door. Something about his utter calmness took the wind out of my sails. I couldn't exactly call it calmness, though, for the next moment he turned and looked at me with his wistful and hungry and half- hopeless stare. Then I laughed outright at him.

"That particular deck was made for the particular purpose of walking on," I pointed out to him. "So, why sit up and worry about that particular individual who has to go about his own particular business on it? There's lots of people aboard to walk a deck. Let 'em walk—let 'em come and go until the heavenly cows come home."

"But It never goes," the other man answered.

"It must go," I told him.

"No, It comes to my door," he said. "Then It stops."

"What do you mean by 'It'?" I demanded. He did not answer my question.

"It will come again," he said, staring past me out into the darkness. "Then the knob will turn."

"And it'll go away again," I derided, "the same as it did five minutes ago. And probably go down to its berth and take off its clothes and go to bed, the same as you and I should be doing."

"But It never goes away," he whispered. Something in his voice, as he whispered those words, sent a tittle spreading chill needling up and down my back. I experienced a distinct horripilation, in spite of myself.

"But what do you mean by 'It'?" I persisted.

"I don't know," he said with his helpless stare. "Look here—this is rampant theatricality," I told him, and I said it with considerable vigor. "This is pure hysteria. You're getting worked up over nothing. You're worse than a juba-patter at a camp meeting. You're getting worse than a darky in a graveyard. But you can't get me that way."

He didn't so much as give me a look.

"It will come back," he mumbled. "It keeps coming back, as though It wanted something."

I forced a laugh at that. Then I made him sit down in one of the empty chairs.

"It's you that want something," I warned him. "Your wires are getting crossed. And this is no time to untangle them. But it's either heat and worry, or temperature and too much quinine. If it's not that, then it's stomach or eyes."

He turned round again and looked at me. I can see that haggard and mournful face even now. I can still see the look of plaintive indifference in his deep-sunken eyes, as though he'd realized I was out of touch with him, hopelessly out of touch with all his world.

"You're not getting enough air in here," I told him. "You keep this cabin like a bake-oven."

"It's not that," he wearily protested.

"And, I suppose, you shut this door every night?" I gibed.

"Yes," he told me quite shamelessly. I demanded to know why.

He looked at me again with those calm and indifferent eyes of his. Then he glanced out across the gloomy deck.

"I have to keep It locked out," was his answer.

"You've been dreaming," I told him.

"No," he persisted. "I have to lock It out every night. It wants to get in. It comes and turns the knob. It keeps trying to get inside."

This was a little too much. "You've been dreaming," I reiterated disgustedly.

"No," he persisted, "I haven't been dreaming. And my wires haven't got crossed. I can go through any test you put me to. I'm as calm and sane as you are. But, I tell you, I can't stand having It come to my door that way, night after night."

"My boy, you're malarial, and you've been having the nightmare of your life," I tried to assure him. "What you want is sleep and cooler weather and something to whip those nerves of yours into shape. And the first thing to do is to get to bed and forget all this. Then, I'll see you in the morning and we'll talk things over in sane, sensible daylight, when things don't get twisted and we don't hear crooked and see double."

"You'll keep It away from me? You'll clear it all up?" he asked in that plaintive and fretful tone of his. And I quite cheerfully assured him that I'd take "It" away from him. I was a little condescending about it, I fancy, the same as you'd be with a peevish child. Then we had a smoke together, and I tried to quiet him down by talking over such commonplaces as the new Broadway musical comedies and what Coney Island had grown into since he went south. Then I gave him a bromide, said good-night, and took a turn or two on deck, watching the stars and wondering first at the loneliness of the ship in particular and then at the loneliness of all life in general. Then I went down to that Dutch-oven of a cabin of mine and tried to go to sleep.

I'M afraid I didn't sleep any too well that night. I tried to tell myself it was the heat, but I kept thinking about Stobart and his delusions a great deal. The next day, too, his appearance rather disturbed me. I made it a pretext to look him over when the chance came. And I pounded him about and put him through a catechism that'd make a Bertillon chart look like a chalk sketch. But I found him normal enough, outside the malaria and the cabin-door matter.

The only way to straighten out that mental kink of his, I decided, was to get to the bottom of the whole tu'penny mystery, to translate the entire business into its obvious materialities. Did you ever stop to watch a child engineering mill races on the seashore, and then with a sort of malicious good nature divert his whole river bed, knowing all along you could return it to its old channel with one side scoop of a foot through the sand? Well, that's how I felt about Stobart. I thought myself a bit of a psychologist, and I'd bumped into psychoneurosis enough to feel at home with an illusion like this. So I told myself that I could afford to be both patient and generous with him. In fact, we sat down and talked the whole thing over together very quietly and reasonably, though never once would Stobart admit the possibility of sense error or the contingency of a ship's motion occasionally flinging open a door which was not any too securely latched. He was quite fixed in his belief that some agency, not natural and normal, had repeatedly come to his door and tried to open it.

It ended in my agreeing to sit up and watch with him. And that midnight found me up in the wireless room, with a goodly supply of tobacco, a storage flashlight and a singularly open and disengaged mind. Stobart's plaintively superior manner, as he glanced down at my flashlight, rather irritated me.

"This may look foolish," I told him as I sent the flash fingering like a searchlight into his darkest cabin corner, "but I'm going to get a glimpse of those mysterious feet or know the reason why."

"I've been over all that ground," he answered a little wearily.

"Then you haven't been over it in the right way," I promptly informed him, "or there'd be no need of me here. This is no voodoo and black-cat business. We're not plantation negroes, you know. You can't carry a banshee and a wireless outfit on the same steamer."

"Then, what is it?" he demanded.

"It's several things," I told him. "But, most of all, it's mere neuropyra, and I'm going to show you why. You're a sick man—you're simply a victim of your own worn-out nerves." And I lit up and sat down and talked to him on abnormal psychology and what I remembered of it, explaining as well as I could the inferential construction of sense perceptions as related to illusions proper, in contradistinction to hallucination. He laughed a little, I remember, at some of my phrases, like intraorganic stimuli and associative law of preference and acatateptic imagination. But, naturally, you can't expect to make much headway on such subjects as the objectification of thought and the influences of expectant attention when your listener hasn't even heard of Rabier. "I'm not much of a Weir Mitchell," I know, I wound up with, "but I'm going to cure you of this bug."

That word "bug" was something he could grasp. But he only smiled a little. "It's no use," he said in his tired and wistful way. "It's not a bug."

"It is a bug, and you've got to smash it," I had the brutality to tell him, "or it's going to smash you." He got up with a shrug and crossed the cabin and closed the door. I looked at my watch. It was almost two in the morning, and nothing had happened.

Something about his isolated figure enlisted my sympathy against my will. I even tried to extenuate things for him as we sat there, explaining how everything in his case tended to pile up the mystery; how mysterious was any ship at sea, with an equatorial midnight about her; how mysterious the apparatus with which he worked was, with its ghostlike calling and receiving across such spaces of silence; how mysterious even trivial mental illusions were, once they were played upon by the converging lines of association. Then, oppressed by his haggard and hopeless eyes, I asked him to tell me how the whole thing had started.

He sat back and began talking. He spoke without excitement or emotion, watching his apparatus as he talked.

"I was sitting here, the second night out, just as we're doing now," he said. "I'd been trying to tune up to a Navy message I hadn't quite caught. Then, all of a sudden, I lost them altogether. It was very quiet in here except when 11 called.' Then, of course, it was nothing but crash and rattle, with my spark going. I was waiting and listening very intently when I What are you looking at?" he suddenly broke out with, for he must have turned, at that minute, and caught sight of my face. As a matter of fact. I wasn't looking at anything. I was listening—and listening with every nerve of my body.

For, across the quietness of the deck outside, I knew I'd heard a sound. It was a sound of footsteps. They were very faint at first; they seemed coming from an indescribable distance; but I could hear them coming closer and closer. They seemed as unhurried as the steps of a mourner at a funeral.

"It's coming!" Stobart whispered, and, before I could stop him, he'd switched out the light. I knew by this time there was no mistake about my hearing those steps. They were so distinct that I remember the feeling of disappointment that swept through me—I felt so sure our visitor would turn out to be an officer, who'd have the laugh on us for eavesdropping at that time of night. Yet the steps, all the while, kept coming closer and closer.

I remember Stobart's clutch at my arm as they came to a stop at his door. Yes, they were clearly and unmistakably at his door. I already had my hand on the knob, padding it with my moist palm, so that I could both detect any movement that took place in it and at the same time open the door without a second's delay.

But I knew the knob had not turned. I also knew the intruder was still there. I kept my attention fixed on him there, listening for the slightest movement, as I brought my flashlight up in front of me. I did not wait for any word or sign from Stobart. I simply opened the door like a flash. At the same moment I threw on my electric, giving it a sweeping, semicircular movement. If it had been a machine gun it would have mowed down everything on the deck. But it would have mowed down nothing mortal. There was not a living soul in sight. The deck was empty, as empty as a church!

THAT empty deck was more of a shock to me than I had allowed for. It upset me considerably more than I had counted on. It gave me that sick feeling, that indescribable, nauseous sinking of the diaphragm which comes to a man when he feels his first earthquake under his heels. It seemed to take the bottom out of everything. Then, in some way, the whole thing angered me, made me as mad as a hatter. Nothing could dethrone Nature and Reason. As a man of science I wasn't going to stand for either hysteria or nautical table-rapping. I decided then and there to get to the bottom of the thing, to shake the nonsense out of it, if I had to sit up for a month to do it.

Stobart himself wasn't acting in a way to soothe anybody's ruffled nerves. "What does it mean?" he kept whimpering. "What does it mean?"

"Keep cool, man; keep cool!" I told him for the second time. Then it suddenly came home to me how hot that little cabin was. My ducks were wet through.

"Now you understand!" Stobart was exulting as he mopped his face and dodged back and forth like a hyena in a cage. I got the impression that the whole world was going mad and being coffined up in four stifling cabin walls.

"Come outside," I told him. "Get outside in the air and we'll talk this thing over." I didn't want him to think that I'd come a cropper myself. And I remember almost dragging him out of that cabin the same as you'd drag a man from a quicksand. We got to the rail and stood there for a while, looking about us. Then we walked up and down the quiet deck. I can remember how homely and consoling and regular the throb of the screw sounded. Even the scrape of the stokers' shovels from the engine-room fiddle was good to hear.

When Stobart spoke up and said, "There's something wrong with this ship!" I remember the feeling that crept over me, the passion to smash his sneaking thing of mystery, just as you'd want to smash a rat that kept raiding your pantry or vermin that were fouling your linen. I still clung to the belief that it was some trick, some foolish hoax, which any moment of calm study might suddenly show up, like a searchlight, in all its hilarious and laughable simplicity. I kept asking myself if it mightn't be an echo of some sort, a series of sounds oddly reflected from a remoter part of the ship, a sort of ventriloquism of wood and iron, which might be projecting certain footsteps from the bridge or from a lower deck into this upper area of audition. I even experimented among the lifeboats, using them for sounding-boards; but nothing came of it. Then I turned back to question Stobart. to make sure he had no enemies on the Clotilda, to cross- examine him as to what friends he'd made and what visitors he'd had. This, too, came to nothing; he didn't know a soul on board. Every possible avenue of escape seemed to lead straight back to that old, blind wall of enigma. So it wasn't merely sympathy for Stobart that left me more than ever determined to get to the root of the whole matter. I felt oddly and keenly sorry for him. It seemed to have left him so helpless and childlike. Indeed, if he'd been an imaginative man it would never have knocked him off his feet the way it did. Hut he was all sober, calm, common- sense, as we call it. What he saw, he saw. Truth, outside of actual experience, was to him what you might describe as a metaphysical absurdity. The corollary of this was equally obvious. Experience, outside established truth, was just as much an absurdity. So it cut the world from under his feet. It left his mind staggering feverishly through a dozen inchoate hells of doubt and disorder. It flung him back into a black chaos of unbelief, a chaos that a whole lifetime of careful sorting and pigeonholing of experience had been shutting away from him—the same way, I suppose, that Dutch gardeners shut away the sea with a dyke.

But it wasn't for Stobart's sake that I intended to stick to the thing. It was no longer curiosity; I'd passed the off-handed dilettante stage. My own experience had bumped into something it couldn't swallow, and I had to Fletcherize the whole lump into a pulp of common-sense or leave reason to choke to death on the irrational. But I preferred making my investigations by myself. I didn't care for any more outside infection of emotionalism. So I asked Stobart if he wouldn't go down and get a few hours' sleep in the infirmary or even in my cabin. He refused, however; he had to stick to his wireless. He wanted to be fair to the ship, he said; and I began to feel that, after all, there wasn't so much of the coward about him. But he finally agreed to take a deck chair somewhere amidships between the lifeboats, where it was cool and where he'd be within reach of his room. Then I could call him, he said, if anything happened.

MY first move, when Stobart had taken himself off, was to examine his room. Outside the apparatus table and the Leyden jars and condenser above the narrow sleeping-berth the room held nothing of interest. There were no dark comers, no draperies, no hidden openings, nothing in any way ambiguous, nothing capable of harboring mystery. The only thing that caught my eye with any sense of shock was a large-caliber revolver lying in between Stobart's helix case and his Leyden jars, directly above his berth. But even that I could account for when I remembered the uncertainty under which he'd been sleeping there. Indeed, I found something reassuring about that gun, as though it stood for a determination to combat only material enemies.

I was glad enough to take my hint from that, finding something rather consolatory in making those preparations which you'd make only against flesh and blood, which you'd make only when you're trying to trap something material and ponderable. This feeling prompted me to slip down to my own room and catch up a fresh supply of tobacco, a couple of suture needles and a spool of silk, and then a phial of quinine sulphate. The latter was some old stock which had failed to produce the quinine reaction— time and careless handling had apparently converted it into one of its isomers. But I'm afraid I'm making that rather technical. What I'm getting at is that the stuff was air-drawn, and I took it only because it supplied me with a white powder. I mention these details simply because I want you to understand I was thinking normally, that I was clearheaded enough to appreciate even the smaller points as I went along. I remember, in fact, the sense of confidence that came to me when I got those familiar suture needles in my hand, as though they were instruments that wouldn't even fail me in drawing together the ends of a psychic mystery, as though they could sew up even the sort of mental gash I've been trying to tell you about.

I also brought up with me a bunchlight, a cluster of six electrics under a glazed reflector, such as they swing over a landing ladder at night. I dug out enough of Stobart's insulated wire to connect this bunchlight with the ship's ordinary circuit, and swung it directly over Stobart's door, so that the turn of a switch from inside the cabin would make the deck as light as day. Then I threaded my two suture needles with silk and pressed them down into the deck boards about three feet out from the doorsill. Then I showered the deck with my quinine sulphate. No one would be likely to reach that wireless mom, I knew, without breaking my slender hurdle of silk. And no one could approach the door, I felt equally satisfied, without leaving a pretty clear impression of his steps. And when I had the size and shape of those steps I knew I'd have something to work on. I even remember my impulse to connect the brass doorknob with Stobart's dynamo, so that my evasive visitor, the moment his hand touched the metal, would get a shock that'd knock the sleepwalking out of him for a week or two. But that, I decided, as I stepped inside the wireless room again, would be both foolish and dangerous. Instead. I looked over the cabin for the second time very carefully and found everything as I had expected. Then I lit a pipe, lowered my collapsible deck chair a few notches, switched off the light, and quietly opened and hooked back the cabin door. Then I waited for something to happen.

I was comfortable enough, except for the heat. I remember putting down my pipe —tobacco had no taste in the dark — and I also recall shifting my chair along the cant of the deck so I could get my feet up on the berth edge. I remember thinking, for the second time, what mystery hung over all ships at night, and warning myself that it was in air like this, velvety-hot and steamily-distorting and humidly-melting all at once, that systems and theories went wrong in the hardest of human heads.

There must have been something hypnotic in the drone of the fan over my head, in the steady throb of the screw, in the slow rise and dip of the ship, in the soft swish of the water along her side plates. I suppose, too. I was a bit tired after my second night of broken sleep. But I went off, without knowing it. against my intentions.

I'd no idea how long I slept there. But I woke up with that sense of depression, of bewilderment, which comes over you when you wake up in a strange room. That's what I tried to tell myself, at least, as I lay back in my chair. Then a keener impression came to me, a vaguue sense of evil which I can't even describe. But the totality of that impression, whatever it was, caused a sort of mental gasp. If I'd translated it into actual words it would have amounted to the exclamation: "There's Something in this room!"

My shift of position had rather turned my face away from the operating table. But a sixth sense, intuition, anything you like, kept telling me that Something was stirring and moving behind me, almost at my side. I felt a draft of cooler and damper air from the deck outside. I remember wondering if the grayness of the light could mean that morning was coming. But I felt that Presence there until I could stand it no longer. I couldn't forget that this Thing, whatever it was, stood between me and the door; I couldn't forget that it was there between me and my freedom. And I knew I had to face it.

I turned my head very slowly, inch by inch, until my glance was able to take in the entire wireless room. And I merely saw a man in a double-breasted blue uniform. He stood at the operating table, bent over the responder as though some detail of its mechanism puzzled him.

Something in his attitude as he stood there struck me as indescribably sorrowful. I don't think I ever saw greater pathos, a more poignant suggestion of tragic misery, than I caught from the bending profile of that lean and hungry-looking face. The eyes were hooded by the bulging frontal bone until they were in deep shadow, until they were cavernous, like that figure of Abbey's Hosea, isn't it? I couldn't actually see them, but, hidden as they were, they seemed to hold the most unsatisfied and wistful look I ever saw on a human face. This pathos extended even to his figure, which was lean and stooping and seemed to have fallen in on itself. His whole attitude seemed one of an anxiety and anguish and frustration that was unfathomable. And, in spite of myself. I felt that sudden horripilation which comes with most sudden shocks to the nerve centers. I could feel my hair rise and then that tingle of fear—you know it, like mice going up and down your backbone! For I felt there was something— well, something abnormal about it all. Yet it was merely the figure of a man, understand—there was nothing phantasmal or sepulchral about it—no ghost nonsense with a mist or an aura of light about it. It was just a man, a plain, clear-cut, distinctly-outlined, extremely-attenuated man in a double-breasted blue cloth coat with two rows of brass buttons running down the front of it. But here was the disturbing part of it: I know every man and officer aboard the Clotilda. And this man in the double-breasted uniform coat was not one of them.

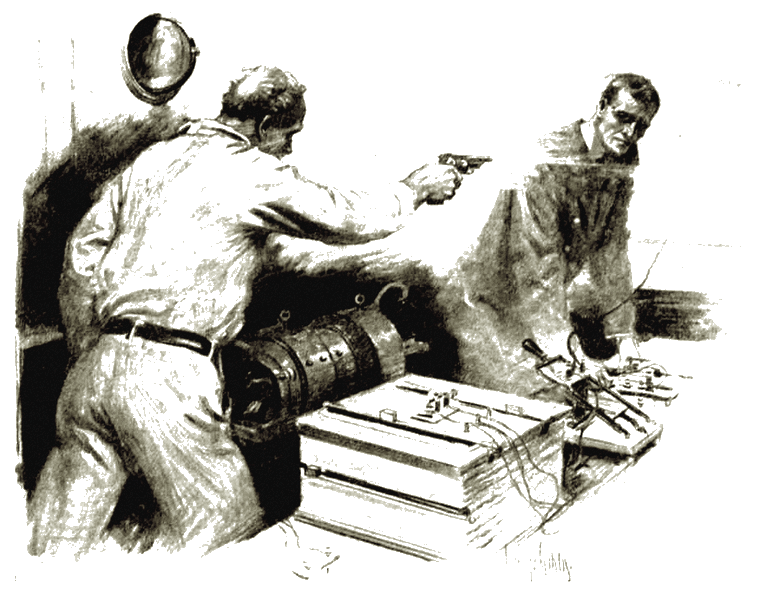

I remember, as I sat back, peering up at him, how I still refused to believe what I saw. I even remember thinking that a coat like that, in such heat, couldn't be altogether comfortable. I tried to tell myself that I was still half ski-ping. But I reason couldn't swallow that. Then I tried to persuade myself that the figure was that of some ovsriapplns dream projecting itself into the area of waking consciousness. Perhaps it was a sort of dream, and nothing more. But I know that, the next moment. I did one of the most foolish things of my life. I jumped to my feet and shouted out loud. It wasn't for help. It wasn't even to give an alarm. It was more the involuntary and inevitable expression of overpent feeling flowering into action. And as I shouted I sprang for Stobart's big nickel-plated revolver next to the helix case. I don't remember taking aim or firing. But I remember my surprise on hearing the sound, and my sudden horror as it came home to me that this man who had come into the cabin was merely a stowaway, and that I was murdering him. The shots rang out clear and quick—you can imagine the noise, at such a time, along a quiet deck!

I don't remember taking aim or firing.

When they came running into the wireless room they found it full of smoke and the splash of six lead bullets on the painted wall. But that wasn't bothering me. What appalled and stupefied me was that every bullet had gone through that stooping body as easily as hailstones drop through a cloud. I think he turned and looked at me, but I'm not sure. Then he passed through the cabin door and walked away, not exactly reproachfully, and not exactly angrily. But I watched him as he turned and strode across the deck. I watched him as he went through my silk thread without breaking it and the fall of a folded newspaper would have | snapped it and strode out over my I powdered boards without leaving so much as a mark. I stood leaning against the open door, watching him as he crossed I that empty deck and walked out through the ship's rail, out through three iron bars and six inches of solid oak into space, like a puff of smoke.

Then I knew that the uproar had brought the men from the bridge and Stobart from amidships and Captain Goodyear himself from his stateroom not thirty feet away. I could see the startled amazement on the men's faces. On the captain's. I remember, was anger. On Stobart's was something that seamed to be triumph, almost exultation.

I remember they all stood about, questioning me, and the captain's sagacious side look as he took the revolver from my fingers and craftily pocketed it. He was one of those oldish types of skipper, thickset, hairy, full-bearded, with an ear-tuft of hair on each side of his face, for all the world like a lynx's. I also remember the sudden reticence that had come over me after one look into that face. No, it wasn't reticence; it was merely a realization of the uselessness, of the hopelessness, of ever trying to explain. A minute before I'd been consumed with a passion to tell some one, any one, what had happened; to take outsiders into my confidence; to unload on them, in one avalanche of words; to electrify them with my discovery; to stagger them with the weight of this new mystery that had come into the world —and then to flail it about until we'd shaken out its last pod of truth!

But as I stood and faced them there I realized how utterly incommunicable it all was, how impossible it would be to translate it into the phraseology of every-day speech. I was a Cassandra with messages no one wanted and no one would understand. I was like a drunken musician with a thousand concertos reeling and ramping through my brain. I remember hearing Stobart lie for me—and it angered me inwardly to think he'd stepped into the role of guardian for me saying that sneak thieves had been trying to get into his cabin and I'd promised to sit up with him. I remember hearing Captain Goodyear telling me to go down and take a bracer and a bath and to come to him after breakfast. I remember Stobart trailing after me and asking what I'd seen. I remember turning and petulantly lying to him, saying I'd seen nothing, that I'd fallen asleep and had a nightmare and made a fool of myself.... But, most of all, I remember that strange and wistful figure I'd seen leaning over the wireless responder, and the hunger that seemed to hang on the gray and colorless face.

I was late in getting up to Captain Goodyear's quarters, for I had my rounds to make and a stoker with heat apoplexy to look after. But I found him in the chart room, with a pair of dividers in his red and stubby fingers. There was something about Captain Goodyear's fingers that intimidated me. They were thick and square-ended and brownish-red and scarred. They weren't the sort of fingers to talk psychology to.

There's no use relating just what he said. He was one of the older school, you know; and, I'm afraid, there was a good deal of profanity. But it amounted to the fact that he was going to have order on his ship. He wasn't going to have it made into a private shooting gallery. And, for two pins, he'd lock the wireless room up and put the operator to scrubbing decks. With that, he turned away to his charts, giving me the full breadth of his back.

The incident would have been closed, only I still had a hankering to justify myself. I wanted to make myself leas of a fool in his eyes. "But Stobart's a sick man," I tried to explain. "He's got to be looked after."

That brought the captain round on me in a flash. "A sick man!" he cried. "They're all sick men! They get full o' dynamo and go dippy! Look at Chrysler, deserting at Kingston, two trips back, without so much as taking his clothes! Look at young Tucker, coming whining to me that ne can't sleep in that cabin, and then sneaking off the ship at Rio without a word of excuse. And it's always been that way, putting a lot of land-bred nincompoops into that wireless room to hand me out my orders!"

I tried to speak up for Stobart, but he cut me short.

"Don't argue about it, sir; don't you dare to argue about it! Wasn't it one o' those nincompoops who sent this ship to the bottom? And let her take twenty lives with her when she went?"

This brought me up with a start. "An operator sunk this ship?" I remember gasping out at him. He looked me up and down with his slow and resentful little eyes.

"Yes, a lying, land-bred, underhand sneak who went deaf on his run and wasn't man enough to say so!"

"Went deaf on his run?" I echoed foolishly, for every word was like a battery shock, and the whole thing was so unexpected.

"Went deaf as a post and all the time pretended to be getting his messages," scoffed Captain Goodyear. "And a land station could hear their foghorn when they came for the Irish coast, and kept warning him back. And so they went down on St. Withel's Rock, and there was the devil to pay!"

"What happened?" I gasped. Something in my face made that skipper stop and look at me.

"Happened?" he grunted. "They went down in five fathoms of water before they'd got their last twenty souls off. Ana it took thirteen thousand sterling to raise her and patch her up. And it was that one man who sent her down, that one nincompoop in the wireless room!"

I remember sticking there to the captain's side in spite of his gesture of dismissal. "But how did they know?" I demanded. "How did they know he went deaf?"

He didn't look at me as he answered. He was busy making his dividers walk over a chart, like a boy on stilts, stiff-legged, step by step.

"Shut himself up in his operating-room when she struck, and blew his brains out. Then they found letters he'd written, when they raised her letters to his wife telling what happened. And I'm here to navigate this ship, sir, and not rehash admiralty court inquiries."

"Then it's true!" I cried, and I stumbled out of the chart room, I don't remember how. But I remember wandering to the rail and leaning there, limp and weak as a seasick passenger in a side roll.

At last, I deliberately and vindictively made up my mind to see the thing through to a finish. I decided to go to Stobart at once and have it out with him, the whole cursed business. And I didn't give that feeling time to cool. I started for his door without waiting to think the thing over.

I say I started for his door but that was all. Did you ever see a house dog diving for a bone and suddenly finding a tomcat guarding it? Well, that's precisely the way I brought up, of a sudden, as I started toward that wireless room. For there, directly in front of me, in the deep shadow of the awning above the open door, stood the figure in the double-breasted blue coat with the two rows of metal buttons down the front. It wasn't looking at me, at first. It was looking up at the sky. at one of those wide, tropical skies with whipped-cream cumulus clouds in it, like an azure dish-cover with tufts of cotton wool stuck about its edges. I never saw a man look so wistfully at a stretch of blue sky before. Then he stepped slowly back into the wireless room and, as he stepped back, he looked at me steadily and quietly. It wasn't until he turned half away, and the stronger sidelight fell on his lean and melancholy face, that I noticed the mark on his temple, between the ear and the end of the eyebrow. I'm not maintaining it was a perforation, or even a scar. Only, I saw it unmistakably, quite small and clear-cut, as though the cork of an ink-bottle had been pressed against it.

IT was Stobart himself, with a jug of ice water in his hand, who found me standing there, staring in through that open door. I didn't move or look round when he spoke. I wanted to assure myself that the Thing was still there, that it didn't escape.

"What is it?" Stobart cried out. I suppose I wasn't an altogether healthy color.

"There's some one in there!" I told him. He turned and looked into my face instead of looking into the room. It wasn't apprehension I saw in his eyes; it was rather incredulity, almost pity, I thought.

"But it's impossible," he declared, "here in open daylight. You imagine this. It's only in your own head." I remember something strangely like a note of relief in his voice, something that was almost joy on his yellow-skinned face.

"There's somebody in that room," I repeated with the calmness of utter conviction. Stobart started to say something to me. Then he came to a sudden stop. It was a new sound that arrested him, a sound which we each knew and recognized at the same instant. For what we heard was the familiar crescendo drone of the wireless starting-lever as it crossed on the contact-points and threw the current from the engine-room into the dynamo directly under the apparatus table.

I Called out sharply to Stobart to wait, for I could see that he was making a dive for the door. "Not on your life!" was all he answered as he pushed me aside and Hung the door open.

It was a moment or two, of course, before I could swing about and follow after him. I heard his laugh, a little high-pitched and hysterical, and then his self-assured exclamation, "It's empty!"

He laughed again as I stepped into the cabin. I suppose my face was something to laugh at, as I stood there trying to reframe my whole universe into some semblance of reason. I can't describe my feelings to you. But I began to feel that I'd been duped, that I'd been thimble-rigged and victimized.

"You look like a sick man," Stobart had the cheek to tell me.

"Who wouldn't look like a sick man," I retorted, "without four hours' sleep in two whole nights?"

I remember his answer, his complete change of voice. "I don't think I've had an hour's sleep honest sleep on this ship!" He said it wistfully, as though he were very tired. Then he cried out with sudden and vehement passion, "I'd be all right if I only could sleep! I've got to sleep!"

I relented at that, and tried to tell him he'd be better in a day or two, now we were steaming up into cooler weather.

"If I could only sleep!" he kept repeating, and the red rims of his shrunken eyes made me think of a hound's eyes. "All hell can walk that deck out there, now, if it wants to," he declared. "I'll lock it out. But I've got to sleep."

I couldn't stand for any more of that outbreak. My nerves were too shattered. I felt that a black plague of lunacy was crashing and tumbling like a wave over all the ship. I was glad to get away, flinging Stobart a promise over my shoulder that I'd do what I could for him, mix him up something to quiet him down. It was a relief to get below-deck to my dispensary, even to pretend to busy myself with every-day things, to make little tasks for myself, so I wouldn't have time to think. And, late that afternoon, I took Stobart up a phial of chloral hydrate, telling him what it was and advising him to follow the directions I'd written out on the bottle.

He showed little interest in the narcotic by this time, and seemed eager to talk. A strange spirit of elation had crept over him. He appeared pathetically anxious to impart some portion of this to me. But I told him I was tired out and had ten hours' sleep to catch up. I'm afraid I was curt with him. But he followed me to the door, in a way I afterward remembered, and looked after me as I crossed the deck. I caught sight of his wistful, yellow face as I went below, still looking up at the sky as the other figure had done. But I thought nothing of it at the time. I took an opiate and tumbled into my berth, for I wanted sleep before I got to thinking again—I wanted eight or nine hours of revitalizing, reorganizing sleep before I started back to that problem of mine. We'd be at Kingston by morning. I remembered. Once there I could slip away from the ship, out to Constant Spring for half a day, and get a new perspective and a new grasp on things. So I went to bed and slept, if you can call the nightmare of febrile torpor that comes from any of the opiatic derivatives real sleep.

I WAKENED suddenly, about four in the morning, I think it was. The moment I wakened, I remember, a sense of uneasiness, of impending evil, flashed over me. I tried to fight it oft, but it goaded me into my clothes and drove me up on the bridge deck—though, every step, I kept telling myself that the whole thing was asinine.

It was still dark, pitch dark, and the Clotilda was rolling heavily. I crossed to the wireless room as best I could. I found the door unlocked. I went inside and switched on the lights.

Stobart was there, huddled down and back in his chair, with one hand flung out and half covering his transcription pad. On this pad he'd written just five words:

Relay all ships northbound Jamaica...

Relay all ships northbound Jamaica...

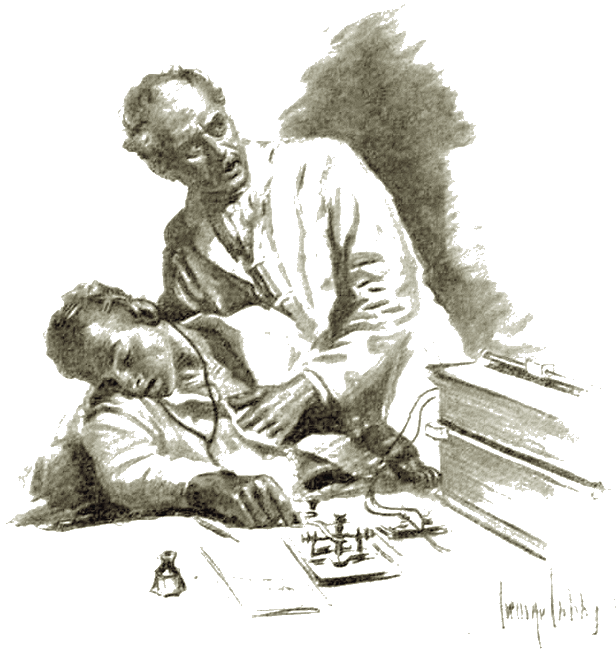

I had my hand on Stobart's shoulder, shaking him, before I really saw his face. Then I stopped, for I knew he was dead. He'd been dead for some time. It took me only a minute or two to make sure of that.

I'd seen Death too often to be disturbed by it. I remember that I was quite calm as I picked up the empty chloral bottle and put it beside his tuner. I even felt it would be more fitting to place the poor chap's body on its berth, to lift it out of that huddled and wistful posture in which I'd found it.

It took me some time to do this decently. Then I hooked back his chair, which kept rolling from side to side, closed ana locked the door, and went at once to the captain's quarters to report. I waited for a moment before his stateroom, wondering how I'd word my message. I clung to a handrail, hesitating over how I ought to tell him. Then a sound came to my ears as I stood there. It sent a chill eddying up and down my back. For as plain as you hear my voice now I heard the spit and crackle of the wireless spark at the masthead above me. Some one or Something, in the room where the dead man had been locked, was operating the wireless apparatus. I pounded on the captain's door, like a frightened child knocking for its nurse—no, more like a lost soul beating on the bars of hell. For I was quivering and shaking when Captain Goodyear came out—or, rather, round from the bridge steps, for we were supposed to be fingering up along the southern coast of Jamaica.

"Stobart's dead, sir," I told him. "Come at once!"

He turned on me slowly, ponderously, like a liner swinging round in a roadstead. "Stobart's dead?" he repeated. "What makes you think he's dead?"

His question, coming after all the nonsense of the night before, rather flurried me. "He died as he was operating," I tried to explain. "I wish you'd come, sir, at once."

He cut me short, turning into the chart-room as he spoke. "Go and make sure you haven't been having another nightmare. Then come back and report!" And I heard him mutter in his beard over his chart, "This is the night we need his damned wireless!" He suddenly stood upright and stepped out on the deck again, peering up through the darkness. Then he turned on me in a towering rage. "Sir, you're making a fool of yourself and this ship!" he cried out. "He's there! He's there operating! Look at his spark, you fool, against the masthead!"

I looked up. I could see the small blue spark come and go at the insulation-points of the antennae. I saw it, and I didn't much care whether Captain Goodyear thought I was as mad as a March hare or not. But I at least knew what rigor mortis was; I knew a dead man when I lifted one.

"Go and see!" I almost screamed at my I commanding officer. And something in my face made him first stare and blink and then swing about and start for the wireless room on the run. I ran after him, remembering I'd the door-key in my hand. He took it from me and flung the door open.

"Where's your dead man?" he cried as he faced the full glare of the electrics. His scoffing didn't last long. I remember the change that swept over his face as the empty cabin and the figure on the berth hit home. Then his eyes moved on to the apparatus table. My own gaze followed his as he turned to the inscription pad. He touched it. "Why, it's not dry! The ink's not dry!" he said. Then we read through the words together:

%% LETTER Relay all ships northbound Jamaica south coast lights gone.... Stand by till morning....

I kept peering down at that message. I didn't hear the captain leave the wireless room. I didn't even know he'd left until I heard the tinkle of the engine-room signals, and then the bark and bellow of voices on the bridge. Then I felt the shake of the Clotilda's deck as the screws reversed and she swung and backed sullenly about in the cross seas. Then I heard more voices, and then the rattle of the anchor cables.

Of a sudden, the ship seemed startlingly quiet. Only the engines had been stopped, but all the world seemed to be at a standstill. I started for the rail to see what had happened. Then I stopped, for I saw a figure leaning over it, over the rail opposite the wireless room. The figure I saw was incredibly thin and wore a double-breasted blue coat. From somewhere out of the darkness, as I stood there, T heard a dog's bark, and then the sound of a gun. very faint, repeated three times. But all I saw was the figure in the uniform coat, as it stood there, peering ahead, with one lean hand over its eyes. It sounds all wrong, I know, but I've always thought I heard that figure say very quietly, "Thank God!" before it slipped away, though I had no sensuous evidence of its slipping away. All I can say is that one moment it was there, and the next moment it was not to be seen.

The lifting weather had already shown a scattered light or two. We'd anchored within rifle-shot of land. Then morning came. Jamaica lay in front of us, close enough to hear our siren. Port Royal stretched before us—a ruined Port Royal, slipped half-way into the sea. It was the second day after the Jamaica earthquake— the earthquake that ruined Kingston and wiped out every light on the south coast of the island, the earthquake that sent the Hamburg-American liner Waldemar ashore beside the ill-fated Princess Victoria Louise. And there was the Clotilda, rocking at anchor, with her forefoot almost pawing the shore gravel! Our ship had been saved.... We took refugees and wounded from Kingston aboard. That gave me work night and day, and I was glad of it. I had a busy week northbound to New York. In fact, I broke down under it and had seven weeks of it in Roosevelt Hospital with what my old friend Bromig mildly described as a case of neuritis. They were all very kind and fed me like a king, and I came away fat and hearty... and hungering for the sea again.