RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, February 1928, with "A Man of Ambition"

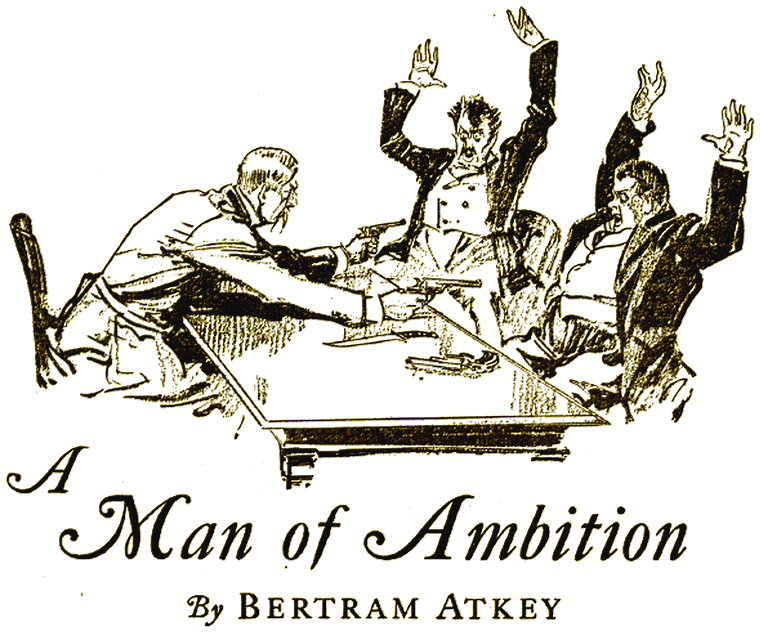

"Gentlemen," I said, "let us not be rough. Much may be lost by violence."

This fine large adventure in rascality is blithely

confessed by that candid scoundrel Captain Lester Cormorant.

There's a Spanish word which, literally translated, means

"hangworthy". It would accurately describe the central

figure in this story—but you'll find him none the less

amusing.

"DRAW your chair nearer to mine, dear heart, for I like to have you close by me, — close enough to touch your beautiful hand, and to see you plainly in the soft twilight, — make me another of these miraculous brandy, hock and raspberry syrup drinks, and let us enjoy the evening together," said Captain Lester Cormorant (late Bolivian Light Horse, and later, the 429th Mud Wallopers in Flanders).

Smiling fondly upon the six feet four inches of wiry masculinity which was reclining so gracefully in a cane chair on the veranda of the country house they were renting for the summer, the doting wife drew her chair nearer, as requested, and proceeded carefully to construct the attractive refreshment which her husband happened to be enthusiastic about at that moment.

He watched her reflectively through his cigar-smoke.

"What are you thinking of, Lester dear?" she asked, observing his close regard for her.

"Of you, darling," he replied promptly.

"What were you thinking of me, Lester?" she continued archly.

"I was admiring, love, the infinite goodness of a Providence which guided me safely across the desolate, hurricane-haunted seas of life into the placid and perfect harbor of your great heart and abounding love, and anchored me there, so to speak, safe and sound behind the breakwater of your very adequate income. Totally devoid of morals, good or bad, though the gods have made me, Heaven help me, there are moments when I cease to lament even that great affliction — so sweet in all other respects do you make them, sweetheart. This," he continued, taking the long tumbler, with its pretty pinkish contents, clinking with ice lumps, from her hands, "this is one of those moments."

He raised the glass.

"All my homage, dear heart!" he said, and drank deep, as a man drinks when seriously dry.

He put the glass on a low table within easy reach, and waved his cigar to the chair at his side.

"Come, sit by me, my wife, and we will watch the evening shadows steal across the lawn," he said poetically.

"Yes, Lester," replied the happy wife.

For a little they sat in silence — a silence which was broken by the lady.

"So you feel, dear, that I make a nice, safe harbor for you?" she asked.

"Eh?" The Captain emerged from a reverie relating mainly to the chances of that aristocratically bred race-horse, Lady Quince, winning the Beeches ... "Pardon, my heart—I was dreaming. A harbor, you say, Louise? Ah, yes. A haven of infinite tranquillity and plenty—I might even say profusion —from which I can, as it were, gaze over what I have called the breakwater of your three thousand a year—less income-tax—and see swimming far below me in the sea of life all those perils from which you have saved me—the shark called poverty, grimly eying me; the octopus called debt, from which I am now safe; the savage, inexorable swordfish called the law, with which I need no longer collide; in short, all the grisly denizens of life's deeps. Can you, then, wonder, pearl of mine, that the seed of love which the Fates planted on the night I stole your motorcar, not knowing you were in it, and subsequently proposed to you in the dark, has grown into an unbreakable vine which binds both our hearts together— eternally and inseparably? Have I your permission, dear one, to place my feet upon the veranda-rail? It is inelegant, but the new tennis shoes you bought me, perfect though they will be in a day or so, pinch a little, and by raising the feet one gains a certain ease. Thank you, life."

He cradled his feet upon the rail and continued:

"It would be an affectation to deny that it has been my good fortune to win the love of many women. I have had a full and varied life, on account of my grievous infirmity—I would not wish my worst enemy to be born without morals of any description—and the love of women has, I confess, figured in it. But compared with your love for me and mine for you, all other loves in my life have been no more than the merest passing, ephemeral, transient episodes. Yes, indeed. There has been a woman here and there, in past years, who has succeeded in constructing for me with her love a species of harbor, and even has break-watered it with mighty income, yet at the first shock of the seas of adversity it has all crumbled and fallen away, leaving me, so to speak, high and dry upon the beach—in fact, I may say, upon the rocks."

He smiled, settling deeply in his chair.

"Unhappy, moral-less wretch that I am!" he added lightly.

Louise Cormorant seemed interested.

"Have richer women than I loved you in the past, Lester?" she asked.

"Richer in the sense that they possessed a greater number of those mere tokens called money, yes," he said; "but they were poorer in all else."

"Who was the richest woman that ever has loved you, darling?" inquired Louise curiously.

The Captain thought.

"I will tell you, dear heart," he said. "I will tell you the whole story."

IT was, perhaps, twelve years ago (began the Captain) that, driven by an adverse breeze, amounting to a positive cyclone, of unpopularity which had suddenly sprung up about me, I was compelled to evacuate, in some haste, the town of Buenos Aires.

The root cause, my dear, of my excessively abrupt quittance of that wealthy South American city was the total inability of the general public to understand that I was unlike all other men, and that those who had dealings with me must bring to the transaction a much greater degree of broad-mindedness than they usually found necessary to employ in dealing with their fellow men.

I refer, of course, Louise, to the tragic omission of morals from my psychology—at birth—and in spite of the great expense to which my good parents had gone for tutors, pastors and so forth, my disastrous inability to acquire a moral of any description.

It is at all times a disconcerting and very painful experience to have to whip out of a town at short notice for safety's sake —although it has often happened to me, I have never really become inured to either the process or the sensation. On this occasion it was really annoying.

I had been conducting a profitable and rather well-thought-out business—a form of lottery, invented by myself, the great charm of which, I may explain, briefly, without puzzling your head with a mass of detail, was that only the proprietor of the lottery could win the prize and that the subscribers thereto had really as much chance of drawing the winning numbers as — as you have ever had of being forgotten by the income-tax sleuths.

I was, then, prospering until, by sheer bad luck, a clerk in a shipping-office discovered what I may term the joker in my system. He called upon me demanding an impossible figure for his silence, lost his temper, and precipitately made public what he chose to term the "fraud."

However, my natural quickness of wit stood me in good stead, and by the time a crowd of regular ticket-holders had subscribed the cost of a good hemp rope, charged their revolvers and reached my office, I am glad to say that I was a good many miles north of the town, and was still progressing at a hand-gallop.

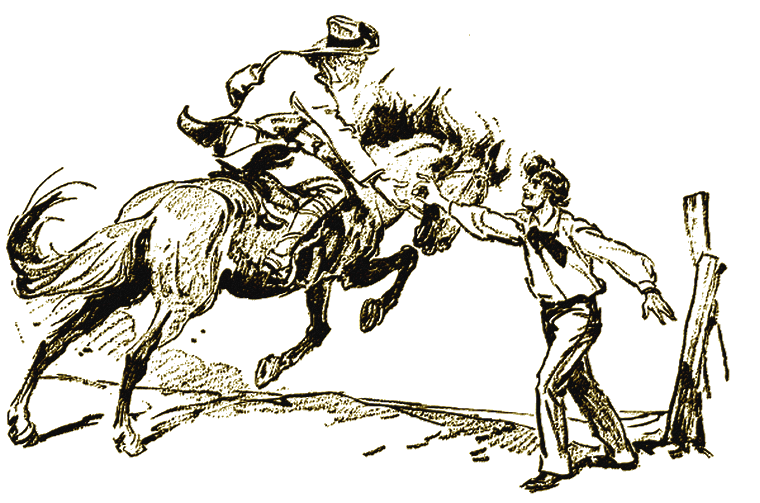

By the time the crowd had charged their revolvers, I was miles north of the town.

I do not disguise from you, Louise, that that departure ushered in for me a protracted period of considerable stress and discomfort. In spite of a very fair knowledge of the species of Spanish used by the inhabitants, things went wrong. I wanted little, but that little was extremely hard to get. My mule —I had taken the precaution to secure the first mule I passed on my way out of Buenos Aires—deserted me. At least he disappeared one night, and it was hopeless to hunt for him in the great plains of Uruguay, in which country I was then wandering.

But, not to harry your gentle heart with a detailed account of my sufferings, dearest Louise, let it suffice to say that in due course I arrived at the borders of the vast estate belonging to a Spanish lady, the Countess Tortilla Maria de Frijole y Bragoso- Zaraganza, a widow lady who, I shortly gathered, was one of the richest women in Uruguay. She was usually spoken of as the Countess Maria.

BY means of a few of those polite fictions without which

good society in all parts of the world would invariably collapse,

I conveyed a general impression that I was an Englishman of rank,

lost while returning from an exploring expedition which had

tracked the Paraná River to its source, failed to discover the

giant stuntosaurus which was said to lurk in the Paraguayan

forests, and other little matters of that kind.

Englishmen of alleged rank were not so common out there at that period as they are now, Louise of my life, and it goes without saying that the hospitality of the Countess was instantly extended to me.

Although I did not meet the lady until the next day, it was at once apparent that I had drifted into contact with one who was quite formidably wealthy. Her house was huge—and, for Uruguay, well-built—and I forget now precisely how many hundreds of thousands of acres of rich pasture she owned. But it was many. The place swarmed with servants and retainers, and there were a few guests.

At least, that is what some three or four gentlemen who took meals with me said they were, though they resembled card-sharps, and behaved—that evening—as such. Naturally their most strenuous endeavors to turn a dishonest dollar out of me over a friendly game brought them nothing but disappointment, loss, and at last a bitter acceptance of the fact that in Sir Gervase Jarman—for so, temporarily borrowing my good old father's name, I was calling myself—they were dealing with a man whose science with the pasteboards was considerably more modern than theirs. We spent an amusing and, for me, not unprofitable evening.

At breakfast the company had dwindled to four of us, namely, the two card-loving visitors, whom I gathered to be politicians —one from Montevideo, Uruguay, who called himself, possibly correctly, Don Vincente Morientes, the other from Asuncion, Paraguay, who referred to himself, perhaps truthfully, as Don José Salammbo.

The remaining member of the party was an extremely handsome boy of about eighteen, who said his name was Sonora — Sonora the violinist, who lived in South America. "My home is South America," he would say, smiling through his cigarette- smoke, "and my wife is my violin." He played the violin very well. This youth, I learned afterward, had wandered all over South America, living at the houses of anyone who would have him, and moving on when they wouldn't have him any longer. He was now attached, in an indefinite way, to the household of the Countess, who liked to hear him play.

His wild, passionate music reminded her of things, she was wont to say. I liked the lad. He was bright, and as much at home there or anywhere else as a swallow on the wing. He gave me some useful information about the country. It was from him that I learned something of the vast possessions of the Countess. She owned, it seemed, so many myriads of cattle and sheep that, said Sonora, the food-value of beef and mutton were as meaningless to her as the beverage value of salt water is to a cod.

"There is a good deal of jasper and porphyry exported from this country, señor ," said Sonora. "But do not mention it to the Countess—she owns practically all the quarries in the country, and it bores her. Of gold and silver mines she owns only two, but they are very rich. Also twenty per cent of the rent paid in Montevideo, as well as thirty per cent of the rent owed is hers, for she owns about half the town. Guano, she thinks nothing of—she owns a deposit on an island off the coast which, in spite of its gradual shrinkage owing to rain, alone would make her an immensely rich woman. Yes," said the lad, reaching for his violin, "this lady, your hostess, my kind patroness, is in no danger of starvation, I believe."

SHE appeared at lunch-time, and she did it well. It was

like a queen who is anxious to keep up her position making her

appearance, heart of mine. Extremely well dressed, in the Spanish

style, she was a woman of perhaps forty. She still possessed the

last remnants of what had once been almost beauty, but in spite

of the extraordinary distinction which characterized her, frankly

she had passed the stage at which she would have had a hundred to

eight chance of winning a "golden apple." At least, for beauty,

though she might have scrambled in to the first three past the

post on the grounds of talent—for she was a very talented

woman.

She was very, very tall, six feet three, I should say — little Sonora looked like a tomtit as he bowed to her.

Our eyes met, some feet above the head of Sonora, Louise.

Some feet above the head of little Sonora our eyes met... Hers fell.

She was six three, I six four—both of us lonely, both past the age of illusion, both, I believe I may say, the only ones of really distinguished appearance there. Our eyes met —clung. Hers fell.

I heard Don José grind his teeth on my left, as I bowed, and on my right a low gnashing sound from Don Vincente. I understood then, why these politicians were hanging about that great house, instead of getting on with their politics, and I swore an oath that come what might, I would save the lady and her income from these fortune-hunting hounds. If necessary I would marry her and personally administer her income for her, myself. I had long felt that I could do exceptional administrative work of that kind.

We went to the meal. The Countess made me sit on her right hand and asked me, graciously, for particulars of my explorations of the Paraná River. Moral-less outcast as I am, Lord help me, I gave her particulars—very interesting they were, and, the Countess said, clever.

The political dons did their best to produce conversation which would mark them as men worthwhile—a difficult matter, and they failed. The lady was gracefully uninterested.

After lunch, Sonora played—a wild passionate thing, of his own composition, which he said was entitled "Love Tryst of the Black Jaguars."

Our eyes met. The violin sobbed.

"When I am President of Paraguay," said Don José, "with your permission, Countess, I will make Sonora leader of the orchestra at the Asuncion Opera House."

"Pardon me," interrupted Don Vincente, "I have already arranged—subject to the gracious approval of the Countess Maria—that Sonora comes to the Montevideo Opera House, when I take over the Presidency of Uruguay."

They gazed dagger-wise at each other.

"Sonora will therefore be in the fortunate position of having two more strings to his bow," I said lightly.

"Rather let us say a string and a half," said Don Vincente. "Don José will agree that, rising little country though Paraguay is, many centuries must elapse before it can compare with Uruguay."

"On the contrary," replied Don José, with the smile of a he- wildcat in pain, "the natural resources of Paraguay are so vast that nothing can prevent its very amazing leap into the extreme forefront of civilized countries, when I am President."

"And how long do you gentlemen anticipate remaining presidents of the countries in question?" I inquired, knowing how exceedingly brief the term of the presidential office used to be in those South American republics.

"For just as long as it takes me to abolish the Republican party and establish a monarchy," said both, "and," they added, "for as long as our plans receive the support of the Countess Maria."

She smiled absently at them both. I saw then the reason why the future kings were hanging on at this place. It was, indeed, quite simple.

They were endeavoring to get sufficient financial support from the lady to enable them to carry out their plans. Each hoped to marry her. By achieving this they would obtain command of so vast a private revenue, that there was indeed a sporting chance of their being able to establish and maintain a monarchy. The quid pro quo to the Countess was, obviously, a half share of the throne either of Paraguay or Uruguay. Do you see, Louise, my love?

I thought rapidly. It would seem that I had been precipitated into a position pregnant with possibility for a man of talent, even though, alas! he were without morals.

I do not conceal from you, dear heart, that I was then a man of ambition. From my earliest youth I had felt peculiarly fitted to occupy either a throne, a presidential chair, or a position as husband to a millionairess. I was younger then—and you had not yet dawned on my life with love in one hand and an adequate income in the other.

Very little thought brought me to a decision. I must marry the Countess, and use the rival dons as my puppets. Later she and I could chat over the question of which country we preferred to rule as king and queen. I had no doubt she would prefer to be Queen of Uruguay. Personally I had a fancy for Paraguay.

"His Majesty King Lester the First of Paraguay" sounded rather better, I thought, than "His Majesty King Lester the First of Uruguay." "Para" sounds less rheumatic than "Uru," I think. An idle fancy, perhaps, and in any case I was not disposed to be stubborn on the point. Besides, it might be arranged—with a little tact—that we could unite the two. "Their Majesties King Lester and Queen Maria of Paraguay and Uruguay" made an extremely attractive remark, or so it seemed to me in those days. I am wiser now, thanks to you, moon of my darkness.

THAT, then, was the position. All that remained was to

extract the utmost benefit possible from it. I am a man who

rarely has found it difficult to get ideas—and I decided

promptly to think things out.

The Countess desired to ride that afternoon, and, escorted by the four of us, she did so. Her mount was an imported Arab mare a magnificent creature—so, I observed, was mine.

The mounts of the dons were less magnificent. Sonora, being whimsical, was riding a milk-white jackass with a red saddle, which the Countess had given him one evening when he had pleased her with a composition which he called "The Firefly's Bride."

Need I say, Louise, that before we had ridden far across the illimitable pampas-like pastures the Countess and I had far outstripped our companions. We arrived at a clump of trees forming a glade, and there we rested the horses. We were at least a quarter of an hour ahead of the others, the Countess said.

I looked at her, smiling.

Her eyes fell.

I took her in my arms.

Her head fell—on my shoulder.

There were few words. She was six three, I was six four. It was a match—I thought at the time. That was before I had met you, I say again, dear heart.

Presently the dons came up, galloping, glaring at each other and at me. Far behind, little Sonora ambled, playing his violin —a new composition called "Lament of the Pampas Satyr" —I don't know why.

I think the dons realized at once that they now figured among the also-rans. They had been uneasy from the moment they saw the eyes of the Countess fall before mine. But they were intelligent enough to say nothing. Perhaps they still had hopes. But what hopes!

We rode homeward—a new respect, darkly tinged with hatred, had come into the manner of the future kings of Paraguay and Uruguay toward me. Maria and I took very little notice of them. Now and then we threw them a word.

I dined alone with Maria that evening. It was very pleasant —not to be compared with the incomparable little tête-à-tête dinners which you and I so frequently enjoy, heart, but not bad for Uruguay.

We had Sonora in with the coffee to play to us, but the dons had to do the best they could by themselves. They did tolerably well, judging from the number of empty bottles I saw in their vicinity, when, after a tender good-night, the Countess and I separated.

I THINK José and Vincente expected me. Sonora had

wandered away somewhere or other in that huge house to find the

major-domo's daughter, whom he was teaching to play the violin.

He was generous with his genius at all times, that boy.

The dons received me with great warmth and remarkable courtesy, and very shortly I was in the thick of what remains in my mind, dearest Louise, as an experience which I regard as unique.

In the course of my career I have often been offered bribes, and, being what I am, Heaven help me, I have always accepted them. But I have never before or since been offered such spectacular bribes as those two rather dingy politicians proceeded to offer me—one bidding, as it were, against the other. It began in this way.

"I believe I do not commit the fault of precipitancy if I venture to offer the Señor Jarman my felicitations," said José.

"To which I am overjoyed to add mine," observed Vincente.

I thanked them both, and said that I believed that I was entitled to congratulation upon my forthcoming marriage with the richest woman in Uruguay, if not South America.

They glared like jaguars with smiles on their lips — very odd it looked, I assure you, Louise.

Simultaneously, eyeing each other, they placed upon the table before them two revolvers and a knife apiece.

"To prevent misunderstanding, señor ," said José to Vincente, with a bow, indicating his battery.

"And to render confusion impossible," said Vincente to José, touching his guns.

They were extraordinarily polite to each other, but a child could have seen that either would have loved to release the other from the cares and sorrows of this life.

"The Señor is probably aware that I am practically in a position to assure him that I hold the presidency of Paraguay in the hollow of my hand?" said José.

"And that I have the presidency of Uruguay, so to speak, under my thumb?" added Vincente.

"I have heard something of the kind," I agreed.

"The rebel army of Paraguay only awaits two things—the order to strike for me, and some pay," went on José.

Vincente said that the rebel army of Uruguay were similarly situated.

Then José informed me that he was visiting the Countess with two objects in view—one being to unite to himself in the bonds of holy matrimony the heart, hand, and means of the lady, and, failing that, to negotiate a sufficiently massive loan from her to pay the rebel army of Paraguay a trifle on account.

"If," said Vincente quickly, when José ran down, "if Don José had been describing my purposes here instead of his own he could not have put the matter more clearly, señor ."

I REFLECTED. I do not conceal from you, Louise, the fact

that, charming though the Countess seemed on such short

acquaintance to be, and wealthy though she certainly was, I did

not look forward with any great enthusiasm to spending the rest

of my life in Uruguay, whereas, I had learned from Sonora, the

Countess loved the place. She was practically a queen there,

whereas in London, Paris, or New York, she would be merely a rich

woman and those places were already so full of rich women, also

women who were not rich but looked it, that she would be lost in

the crowd. I reflected, therefore, wondering if the dons could

raise enough money to buy me out.

"It is self-evident, gentlemen," I said at last, "that the idea of any matrimonial alliance between the Countess and either of you has ceased to possess any value as an idea. In short, I have completely scotched that idea. That is the fact, and, in these matters, one loses nothing by looking a fact full in the face."

They bowed, smiling like wounded pumas. "May we ask what are your views concerning the projected loan—to the new Uruguayan state?" inquired Vincente.

"We seek, dear señor, some indication of the advice you propose to offer the Countess Maria concerning the loan of the pending new Paraguayan régime," added José. I yawned.

"I will give the matter my consideration," I said, "in the course of the next few months. The Countess and I are naturally averse to allowing any question of £. s. d. to rear its sordid head in our present Garden of Eden."

Their jaws fell, and they turned white.

"A noble and delicate sentiment, and one for which—in ordinary circumstances—I have nothing but admiration," said José, Vincente nodding vigorously in agreement. "But alas, señor, an army must be paid! Do you think—you will allow me to mention money for a moment—that you could advise the Countess to lend me five hundred thousand dollars with which to carry out my revolution? I will pay her one million when I am president of Paraguay."

"For myself," murmured Vincente, "a loan of four hundred thousand would suffice—one million to be repaid on or about the day I take the chair as president of Uruguay."

"I do not think so," I said.

"There would be a—Dr—brokerage—a form of brokerage—upon the Paraguayan money amounting to one hundred thousand." said José, "payable to the negotiator of the loan "

"The Uruguayan brokerage would amount to one hundred and fifty thousand dollars," murmured Vincente.

"I spoke hastily," snarled José. "The Paraguayan brokerage would be two hundred thousand dollars, naturally."

"Haste is a deplorable mistake which we are all prone to make," cooed Vincente, but his eyes were going bloodshot as he glared at José. "I too was hasty. The commission on the Uruguayan loan would be at least two-fifty thousand dollars."

"Bah!" snapped José. "Señor, arrange me a loan of five hundred thousand, and we'll halve it like brothers."

"For myself," murmured Vincente, "I am not a hard man. Arrange me a loan, señor, and I give you two-thirds and a charge upon the Uruguayan treasury for a further hundred thousand, payable in three months."

José said nothing—merely because he was speechless with rage.

"The amounts are large," I said in a general sort of way.

So they came at me from a different angle.

"True," said Vincente. "I see that, now that you mention it, señor . Therefore I will endeavor to make shift with a loan of a hundred thousand dollars, of which sixty per cent, as brokerage, will naturally come to you."

José had had enough. He was a man of shorter temper than Vincente.

"Señor ," he said, "this is folly. It is like a circus — a going round and around. Let us be frank. Lend me, as one nobleman dealing with another, lend me twenty thousand dollars, and I will put you in the presidential chair of Paraguay — from which it is but a step to the throne."

Vincente smiled coldly.

"Paraguay? What is Paraguay?" he sneered. "A village in the north, somewhere, I believe. The Señor would not care to pay twenty thousand dollars for the presidency of Paraguay, when for half that sum I am prepared to guarantee to make him king of Uruguay within six weeks—he paying out-of-pocket expenses."

"What is that to offer the Señor ?" screamed José. "King of Uruguay! That goes well! Hah! Emperor of Cowpastureland!" He wheeled to me.

"Señor, my last word. Lend me five hundred dollars, and I —José Salammbo—will positively guarantee to make you King of both Paraguay and Uruguay."

"I will do it for two-fifty!" snarled Vincente; and simultaneously they snatched their guns.

Do not start, Louise, my love. I may say that I was quicker than either. They never raised the pistols more than two-thirds of an inch from the table, for I had a revolver-muzzle trained upon the upper abdomen of each. One who has suffered the buffetings at the hands of Fate which I have, learns to be quick at the draw.

"Gentlemen," I said, "let us not be rough. Much may be lost by violence, nothing can be gained. It is evident to me that you are simple adventurers—very simple and not too adventurous."

BUT here Sonora entered with two men, at the sight of

whom José and Vincente paled.

"Are these the gentlemen you seek?" asked Sonora.

The men—obviously police—smiled.

"Oh, yes!" And one approached José.

"You are arrested by order of his Excellency the President of Paraguay," he said pleasantly.

"Upon what charge?" hissed José.

"Conspiring against the welfare of the state."

He slid a pair of handcuffs on José.

And the second man, on behalf of the President of Uruguay, collected Vincente on much the same grounds.

"You may clear them away," said Sonora; and it was done.

"A very good riddance to some extremely poor rubbish," I said, smiling.

"You think so?" replied Sonora.

"They were mere fortune-hunters," I explained.

"Yes," said Sonora; and he passed me a small handbill. "Are you interested in handbills?"

"Not very," I replied, but glanced at it and perceived that my reply had been incorrect.

I was interested, for that handbill contained a most libelous picture, and a detailed description of myself—yes, my heart—with a list of the peccadillos I was said to have committed in Buenos Aires, and a handsome reward was offered for my arrest—dead or alive. The barbarity of it!

"This," I said, "is a mistake."

Sonora smiled. "I am sure of it. There is a detective on his way from Buenos Aires; he may be here at any moment. You will be able to explain it to him."

I put on my hat.

"It is important that I meet this detective person and explain at once," I said.

Sonora nodded.

"I knew that you would be anxious to do so, and I ordered a horse to be saddled and brought round."

Outside, a horse's hoofs were pounding as a peon led it to the house.

"That was considerate of you, Sonora," I said. "I will gallop to meet the detective." I swung myself into the saddle.

"Yes. He is coming from the south. You cannot miss him if you ride steadily south."

"Thank you," I said, and faced north.

"I like you, señor ," said the youth; "but I like the Countess better. All's fair in love—h'm?"

"Oh, decidedly! I bear no malice."

He passed me something that glittered.

"Good luck, señor," he said. "Remember, the detective is coming from the south. Here is a compass. It is but an old, worn one; all the points are illegible but one—the one which indicates north."

"Good luck, señor," he said. "The detective is coming

from the south. Here is a compass; all the points are

illegible but one—the one which indicates north."

"That is all I shall require," I said; and drove my heels into the horse's ribs.

A month later I left South America, dear heart. It palled upon me. And shortly after my arrival in England I learned that the Countess and Sonora had been married.

THE Captain sighed a little, remembered himself and

converted the sigh into a cough. "A narrow escape, was it not?

Had I remained to marry the Countess, I should not have met

you."

He drained his glass.

"Let me make you another, Lester," said Louise.

"You are most considerate, my love."

"Did the Countess ever make you something to drink, Lester?"

"Never, my love, not once. One had to help oneself at that house."

"Did she ever give you any presents?"

"Not a present."

"And did you love her, Lester?"

The old adventurer rose slowly from his chair, like a jointed ladder, rising to his full height. He bent over the little woman who adored him, and slid an arm around her waist.

"Sweetheart," he lied nobly, "to tell you the truth, I couldn't stand the sight of the woman. Gently with the soda, darling; the brandy's the thing."

The sizzling of the siphon died out as the Captain, reaching over her shoulder, kissed her twice.

"Two for yourself, my pearl," he said, and added a little one on the cheek.

"And one for your income—which makes our happiness possible."

"Oh, Lester!" sighed Louise.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.