RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, April 1931, with "Treasure in Jaloon"

This fine large adventure in rascality is blithely con-

fessed by that candid scoundrel Captain Lester Cormorant.

IT was the custom of Captain Cormorant to stay at home throughout the whole evening on every occasion of his wealthy and adoring wife's birthday, having first kindly helped her to plan an extraordinarily attractive meal—he, personally, taking great trouble to select a wine sufficiently worthy for him to toast her in. Later he would cheer her over another of the annual milestones with jests, idle fancies, fervencies and above all, those stories of his tolerably hectic past which she loved so well.

"No, heart of my life," he was saying to Louise on the night of her wrfrstieth [sic] birthday, "I never yet have claimed to be a good man—but I have never ceased to combat the statement, formerly made far too freely, that I am a bad man. I am neither. I am merely a sorely afflicted man—one who unhappily was born into this world totally devoid of morals. Not an immoral man,—far from that,—but undeniably an un- moral man, Lord help me! My life,—up till that lucky evening when non-morally endeavoring to steal (in a way) your car, I inadvertently stole you in it,—my life has been a Forty Years' War against those who seemed banded together to achieve the downfall of an afflicted man! Myself!"

"Thank goodness, you beat them all, Lester! You swept them out of your path—your path toward me and my income that is so nice for us to have!" said Mrs. Cormorant warmly.

"Yes, I swept them—sometimes!" admitted the Captain, reaching over to press her hand. "But also there were occasions when I was swept!"

"I can't think how any man could ever have the courage to sweep you out of his path, Lester," said Louise. "And I shouldn't think a single woman in the world could have the heart to do it."

"They did—both married and single," declared the Captain. "Why, I suppose the most unmistakable reverse I ever suffered—my bitterest humiliation—was inflicted on me by a woman!"

"Oh, tell me about her, please?"

"With pleasure, my soul," agreed the Captain.

DURING one of my periods of what I may term partial

eclipse (began Captain Cormorant, not without a certain

relish)—or a total eclipse, indeed, it was—as far as

this country is concerned. There had been misunderstandings at

home, due wholly to the denseness, lack of vision and

unsympathetic attitude of a number of people in

England—some of them relatives of mine—who failed to

understand that on account of my moral-less condition, it was

necessary to deal with me just a shade more resiliently than with

most other men. As a result of their stupidity I had left the

country with some abruptness.

It so befell that I took with me on that occasion quite a portly sum of money—fortune having favored my misunderstood enterprise to that extent, at any rate. In due course I stayed my outward-bound career at a remote trading station on the African coast called, I believe, Fujuju, or a word to that effect. It was a place of unparalleled obscurity, and there was but one white resident, the trader, at that place. He was, I recall, a person of small blandishment or charm. His name was Gash.

And it was on an evening when we had been sitting late over our bottle of gin—that the man Gash first mentioned to me the unknown territory—unknown in those far-off days—of Jaloon. This was a region some sixty miles or so up the river Gumbooza, the mouth of which, enshrouded in a haze of miasmic mist swarming with fever mosquitoes, was not far north of Fujuju.

From the confidential conversation of the man Gash I learned that Jaloon was a region immensely rich in those natural resources which have always appealed strongly to me. Diamonds, for example—emeralds, rubies—natural resources of that nature. Gold-dust, nuggets—there were large quantities of the genuine stuff available to any bold, enterprising and unmoral adventurer. It is true that the denizens of Jaloon were fierce to the point of fury, and warlike to the stage of homicidal mania. But in all other respects they were as simple- minded as monkeys.

"If a man could get into their territory and survive long enough to get them savages interested in some toy or other, he'd make a fortune," said Gash, in a species of English. "But y'understand, Burleigh-Howard" (the name I was unmorally using at that time) "y'understand that the man who goes into Jaloon backs his trade goods with his life, no less. Mere damned beads are no good, y'understand. There was a trader once went in there with half a dozen barrels of colored glass beads. He never came out.... No, beads don't saw no wood with the Jaloons! But just as soon as I hit on what I call a good idea for an attractive import, not too dear at cost price, I'm going to take a whirl at the natural resources of Jaloon, Burleigh-Howard!" declared Gash rather muzzily.

TO cut a long story short, dear Louise, less than a month had

passed before I had left Fujuju, gone some hundreds of miles

south to Lokoko, a much larger port, where I purchased from a

German trader certain merchandise and a cutter, and set sail

steadily north to Jaloon. What merchandise, you ask, dear

heart—as well you may.

Well, my cargo comprised simply a secondhand, two-pull beer- pump, a crate of cheap electric torches, and six crates of refills—batteries.

You ask what is a beer-engine, my love. Naturally. How should you know—you, whose life has been spent in an environment far too refined to allow the intrusion of even the merest mention of the ordinary, everyday commercial beer-engine beloved by the common man?

Briefly, soul of mine, a beer-engine is merely a particularly attractive form of pump or liquid elevator. Picture to yourself a shining mahogany counter, from the inner edge of which projects upward a handsome polished, porcelain lever, shaped rather like a medium-sized club, butt upward. The base of this attractive club- shaped lever or handle connects with pipes that in turn are connected with the barrels in the cellar below—connected in such a way that, if one pulls the lever forward with a firm, confident action, the beer gushes gayly forth through a shapely, polished outlet into the glass which is held invitingly under the tap. That is a beer-engine, Louise, my love; and upon such a device I had staked my life.

I crossed the bar of the Gumbooza and slowly worked my way up the turbid river. On the fifth day of the river voyage I was awakened in early morning by a thud close to my left ear.

I opened my eyes to perceive a poisoned arrow sticking into the deck within an inch or two of my head.

I sprang up and began to call loudly—in the dialect—to a number of Jaloon warriors on the bank of the river who had opened, so to put it, fire on me. By the simple process of exploding a few fireworks—a job lot I had picked up at Lokoko—I contrived to engage the friendly and curious interest of those poor but bloodthirsty heathen.

Even as I landed my wares on the river bank, I began to chant the praises of beer-engines and flashlights. There were some among those hideously over-armed warriors who scoffed at first, persisting in advancing their view that I be promptly perforated by their large spears. But the older—and wiser—men, attracted by my beer-engine, shook their heads.

"Nay," they said. "Let the stranger hold forth."

Quick to take a hint, my love, I held forth.

"Look well upon me, O ye warriors of Jaloon—look well and listen better! What is—has been—the drinking of beer hitherto but a mere ladling up of a liquid both flat and uninspiring in a large wooden dipper? Behold, I come among you with a device which shall transform your natural ale into nectar—cool, foaming, enlivening, appetizing and with a tang in it! Therefore be patient—wait and see. Take me unto the king— and handle me reverently, lest anon ye feel the weight of the king's hand!"

It was a queen they had, I learned later, but she was heavy- handed, at that. They understood—and proceeded to handle both me and the beer-engine more—Dr—reverently, as requested.

But still, some of the younger, more inexperienced warriors murmured, dear heart. And so, in self-defence, I became more severe. I halted, producing from my pocket one of the flash- lights.

"Listen and take heed, O Jaloons!" I declaimed loudly. "There are bogies abiding in the backwoods—there are jinn in the jungle! Mark me well, who speaks, and who cannot lie! There are goblins in the glens; there are demons in the dark; and the glades are a-glimmer with the ghosts." Pretty good for non-moral extempore stuff, I think you will agree, pearl o' mine.

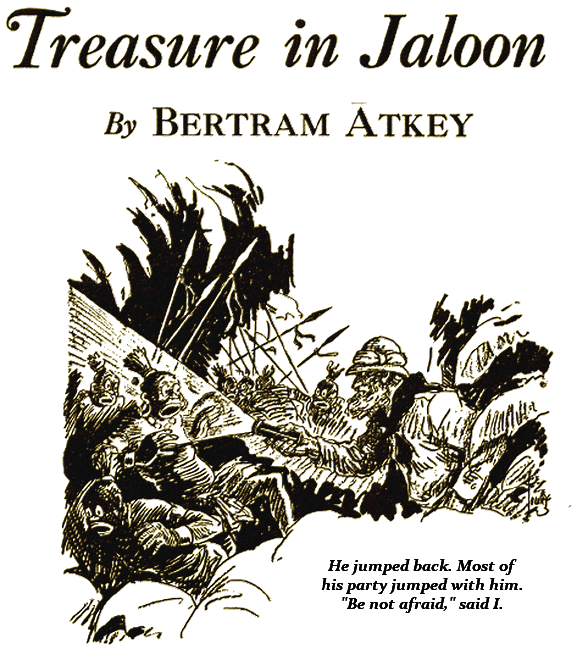

It was gloomy enough under the trees to give them at least an idea of electric light, and I produced a torch, aimed it at the old savage who seemed to be head of the party, and switched it on.

He jumped back from the ray ten feet if he jumped an inch. Most of his party jumped with him.

"Be not afraid," I said, and switched off. "The magic ray is not hostile to mankind. But against the demons of the words it is invincible. There is no demon yet invented that dares to face the White Ray, lest he be forever destroyed ... Enough! Lead me to the palace!"

They did it, Louise, as smartly and deferentially as if I had been their queen's betrothed—a fate which I narrowly escaped during the next week.

She was magnificently handsome, the queen, judged by Jaloon standards. But judged by any other standards she was less so—being peremptory in her manner, herculean in her physique, and severe in her tastes. Her scepter was a large battle-ax—which she handled with the absent-minded ease of a civilized woman handling a fan. She had killed lions with that ax, Louise. But as I pointed out to her,—civilly,—the finest axmanship in the world is vain against the jinn and afreets of the jungle. Magic was needed for these. She agreed.

I explained the virtues of the torches and begged to be permitted to present her with a large one. She graciously accepted it and bestowed on me a magnificent elephant tusk—not a bad beginning, you see, dear heart.

Next, I presented the chief witch-doctor with a small torch—a shilling one. He was so grateful that, in return, he presented me with his most treasured charm—a bladder made of snakeskin, containing a few dried peas, with a handle fashioned out of a foot or so of vertebrae—ordinary backbone, that is to say.

The ceremony of the Giving of Presents over, I begged permission to give Her Majesty just a rough notion of the principle and practice of the beer-engine. Beer, I explained, would be necessary. Thrilling with curiosity, she commanded practically the whole tribe to fall instantly to brewing ...

THREE days later I had everything ready for a

demonstration—an exhibition run—of the engine. A very

large number of gallons were in a large wooden tank in a species

of cellar below; the pipes were connected; and a rather charming

little counter had been erected over the cellar and under the

shade of a sheltering palm. I stood behind the counter, spruced

up for the occasion, and over my head waved the Union Jack. A

throne for Her Majesty had been erected close to the counter. The

natives were in gala attire—where attired at all—and

my friend the witch-doctor had got a sort of band of tom-tom

players working pretty hard close by.

The Queen herself headed the procession from the palace—so to call it—across the courtyard to the beer-engine, put her ax on the counter, and took her seat on the throne.

I raised my hand for silence, took a horn tankard, held it under the tap, and impressively, even flourishingly, pulled the handle.

The beer gushed forth, sparkling in the sunshine.

"Wah?" An exclamation of awe, wonder and thirst burst from the multitude.

Bowing gracefully, I proffered the tankard to Her Majesty. She emptied it, and passed it back for refilling.

"A better tankard of beer I never wish to taste," she said flatly, in the vernacular, and she believed every word she said. It was, of course, the usual native beer, but I had slicked it up a little with trade gin, and of course it had passed through the magic engine, which to the ignorant minds of the heathen Jaloons had transformed it—as I had stated to them it would—into nectar.

"Better beer I never wish to taste," she said in the vernacular.

The Queen had a few, presented me with two tusks of ivory and then retired to the palace to rest for a little while.

I drew a couple for the witch-doctor, and then he announced the opening of the business to the tribe. We had arranged his speech overnight. He kept it short. In effect it ran as follows:

"Tribesmen, the illustrious white wonder-worker desires me to announce that from this hour he is prepared to do business—for cash—at this spot which he has named the Old Flag Hotel. All beer supplied will pass through the Magic Engine. Customers will bring their own tankards. No credit will be given in any circumstances whatever. Ivory, gold-dust or nuggets, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, bricks of silver, and a limited number of well-cured skins will be accepted over the counter in payment. Nothing else goes. I declare the Old Flag Hotel open. Friends, Jaloons and fellow-citizens, go to it! Good health, all!"

They went to it, Louise ...

THE thing was a success from the start. Where they dug up the

stuff to pay for their drinks only an old African expert like

myself could guess. They were the richest lot of

natives—rich in goods that were of no use to them, such as

precious stones, I mean—I have ever come across; and I do

not exaggerate, dear soul, when I say I've come across a few.

In a word, Louise, they lapped like lions—for cold cash. But mark you, my dear, I would allow no intemperance at the Old Flag, for I was determined to keep the thing as sweet and healthy as an unfortunately non-moral man could. I made it an inflexible rule that if any man exceeded his capacity, he should at once be carried to his hut by a couple of friends and there sleep until he could come again.

They literally could not tire of watching me make a magic pass, give the magic handle a magic pull, and bring the beer magically flowing forth.

At the end of the first day I had half a gallon of gold-dust, a quart of quite decent stones, several hundredweight of ivory, some fine skins, and a first-class rhinoceros horn for which I had let a poor hard-up devil have a half-pint.

Next day the Queen put a fatigue party on to brewing in order to keep the vat full. You perceive from that, my love, the true beauty of my scheme. They provided the beer ; I provided the beer-engine and the bar. They paid for the use of the engine, and of course they got their beer free—gratis, so to express it. And everybody was charmed.

Late that night, just before closing time, my old friend the witch-doctor came swaggering through the gang which was chatting round the bar, with his electric torch full on, and said casually that he had been out in the jungle for a bit of a stroll. While out there, he said, he had met a party of ring-tailed demons with fiery eyes led by a six-horned double-tailed faceless jinni! They pursued him the instant they caught sight of him, as was their habit.

The merry, care-free crowd were silent in a second, Louise; and the glances of terror which they began to cast into the surrounding darkness would have touched a harder heart than mine. They listened with all their ears, too. He told a good story, the doctor—full of movement, action and human interest. He worked it up to the point where, footing it for dear life, with that ravening herd of supernatural false-alarms gnashing their teeth at his heels, it suddenly occurred to him: "Why run—with one of the illustrious wonder-worker's white-ray throwers in my pouch?"

He told them how he took it out, stopped, turned and flashed it on his fearful pursuers. He paused there— dramatically, as I thought, beloved.

He turned and flashed it on his fearful pursuers. They fled.

"What happened?" bawled the wrought-up tribe simultaneously. All of them had had similar experiences —or thought they had. It comes of looking too frequently over your shoulder in the dark.

"They fled, howling with fear," with a contemptuous laugh.

The silence of amazement that followed was broken by the sound of my opening a case of the torches.

I do not seriously exaggerate, when I say that in ten minutes, Louise, I had practically sold out—for a fortune. For the beginnings of a fortune.

THE tribe going home to their huts that night looked like a

swarm of large fireflies. He was a sound fellow, the old witch-

doctor. I did not grudge him his commission—a pair of

braces with metal fittings. He wore them forked down over his

head, passing behind his ears, and tied under his chin in a bow,

with two ends sticking up from the top of his head like horns.

They were of more use to him that way, he maintained... .

Well, there I was—owner of a business that promised to make me a millionaire in three months—the fruits of a little real enterprise.

But it was not to be, dearest of all. The Fates had a string tied to it—as I might have known. So far I had swept all obstacles out of my path. Now I was to be swept—and right swiftly at that.

Naturally, I slept late after my Titanic labors of the opening day. Who, may I ask, would not, beloved?

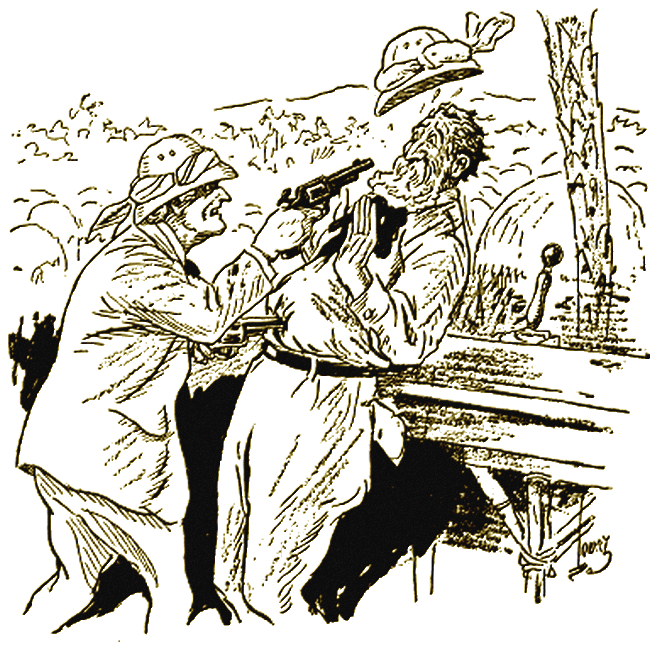

And when at last I did wake, and crawled out from under the bar—naturally, I slept with my priceless beer-engine under my pillow, so to describe it—I found myself face to face with a white woman whose aspect was of a severity calculated to turn one's blood sour in one's veins. She was dressed like a man, and she carried man-sized revolvers, one of which she thrust into my face.

"What are you doing here with my natives, you human bean- pole?" she demanded.

"What are you doing here with my natives, you human bean-pole?" she demanded.

I think I kept my nerve, Louise. It is my custom so to do—for my life has so often depended on it.

"Pardon me, madam—your natives? I venture to suggest to you, with great emphasis, that I found them first!"

She sneered, Louise—sneered at me.

"You! Found them first! Why, you extension ladder, you couldn't find the Atlantic Ocean if you were drowning in it! I tell you, Mister, these natives were first found by me a month ago. I left them temporarily, in their innocence, while I went back to get stocked up with goods suitable for trading with them. I come back here with a cargo of first-class trade-goods for them, and here I find you littering up the place. Keep still, or I'll shoot you clean out of sight! ... What's all this?"

She rapped her revolver on the bar.

"This is the Old Flag Hotel, madam," I said, I think with dignity. "And this," I added satirically, "is a beer- engine—the only one on the Coast."

"Huh, I see it."

She was as quick as she was unbeautiful. She saw the possibilities of the beer-engine in a flash. She thought hard for a moment; then she lowered her revolver.

"Yes, I see. It's a good idea, Walter." Why she called me Walter, I have never yet been able to understand—never, love.

She thought for a moment longer, then strode off to the palace.

I drew myself a pint to steady my shaken nerves and then hurried across to the witch-doctor's hut. I woke him and explained.

"Get busy, Doctor—there is competition threatening us. She's gone to see the Queen."

HE was quick on the uptake for a witch-doctor, and slipping on

his full-dress necklace of knuckle-bones and other badges of

office, he nipped across to the palace—so to describe it.

He was back in twenty minutes with the news that the lady of the

revolvers was leaving Jaloon forthwith. He was what they call a

fast little worker, and naturally I was charmed at this quick

sweeping-out of the severe newcomer. I took the witch-doctor to

the bar and was hospitable to him. We saw the lady trader leave

the palace and hurry back to her boat. She did not even look in

the direction of the Old Flag Hotel.

The witch-doctor and I celebrated her departure in the customary way. The tribe began to wake up and drop in at the hotel; the sun rose; the birds sang; the beer- engine worked; and the cash came in, Everything went well, day and the tribe, freed at last from their superstitious night-terrors, was like a happy family.

So, my love, it went for the next ten days, when I noticed that the receipts were falling slightly but surely, and the general enthusiasm for me seemed a little to be abating. I mentioned it to my friend the witch-doctor.

"Yes, I've noticed it myself," he said. "It's due to their natural laziness. They are getting tired of hunting for the jewels and gold-dust. There's a nasty spirit growing up among them. I mentioned it only last night to the Queen. 'There is quite a number of them,' I told her, 'whose one ambition seems to be free beer! And it's a fallacy, Your Majesty. There never has been free beer and there never will be. If the tribe insists on drinking like fishes, they must expect to pay for it!' Her Majesty agreed."

I was glad to know that the Government, so to express it, had its finger on the pulse of the situation.

SOME two or three days later I had a slight touch of

fever which laid me up for a day or so. I got a few drugs from my

friend the witch-doctor—good strong drugs that put me to

sleep for twenty-four hours. I was awakened from that healing

slumber at about half-past three in the morning by the sound of a

motor engine running somewhere over by the palace. It was so

unusual—so unexpected—that I leaped from my bed under

the bar with my revolver ready for instant use.

But I was too late—I had been double-crossed. That woman had returned, and had all the trumps in her hand. At that hour it should have been pitch-dark, and all the Jaloons should have been indoors and asleep with their flash-lights ready to hand in case of devils coming out of the jungle. But it was not so. I give you my word, Louise, the place was lit up like a civilized town. From a tall pole erected by the palace hung an arc-light like a full moon. It lit up the village like a theater. Not far off between two poles hung one of those wine-merchants' occulting electric signs that continually flashed on and off the following gap-toothed advertisements:

GU NNESS

BASS

WO TH NGTON

JOHN IE W LK R

and near to that, hung on to a eucalyptus tree,

was a smaller sign which intermittently flashed out in bilious,

green letters—

TAKE BE CH M'S P LLS

WORTH A GUINEA A BOX

In the glare of these lights—obviously a lot of

junk picked up cheap with a small engine and dynamo, at some

trading-station along the coast—I saw standing at a huge

trestle table the lady of the revolvers, and two of the toughest-

looking white ruffians I had ever seen.

On the table and all about them were—what do you think, Louise? Soda siphons!

Even as I stared, the woman began to address the tribe in quite good Jaloon.

"Your Majesty, ladies and gentlemen," she bawled raucously, in effect, "you are now witnessing in full working order an installation of the most modern and up-to-date devil-scaring apparatus ever invented! It will be apparent to the meanest intelligence that compared with this installation the pitiful, futile and shamefully expensive little portable demon-scarers planted on you by the dissolute confidence-trickster over at his miserable public bar are worse than useless. You have been paying about five thousand per cent too high for your protection, friends. No longer will it be necessary to hand that lank-legged four-flusher at the hotel twenty ounces of gold-dust for a rotten little half-expired refill. For with the Government's permission, I and my two miracle-men propose to put this installation at the service of the community free of individual charge in return for an annual rate to be levied on the community. You can judge for yourselves whether the installation is likely to scare off the pluckiest demon in the district! In any case, we personally guarantee it. The annual rate will be low—a bushel of diamonds, emeralds and rubies, and say, half a ton of gold-dust per annum paid in advance! Is that agreed ?"

The tribe yelled themselves hoarse accepting.

"And now," continued the creature, "for another announcement: Why continue to pay half a pint of jewels for a quart of your own beer? Why be gypped out of your money for sake of seeing your own beer shot through a cheap beer-engine picked up at some junk dealer's down the coast? Why not own your own beer- engine—dainty, compact, portable, efficient and cheap?"

She lifted one of the siphons—they were quite obviously a cheap lot of soda-making machines, no doubt exported by some Continental firm—filled it with beer, screwed on the small cylinder containing the gas, punctured it, and a second later she was squirting aerated beer into a glass for the Queen. Probably it was awful to drink—native beer is awful anyway. But I confess that it looked very effective, my love.

The poor mutts went mad about it. Everybody wanted one—but all were short of ready money. I had that.

She announced the price of the gasogenes—and noticing that the figure rather daunted them, she made a suggestion so mean, so low, so intolerably vulgar and unsporting that I could have blushed for her.

"If you are short," she said, "why don't you go and take back the money which has been extorted from you by that Shylock-souled fire-escape at the Old Flag? Her Majesty will approve!"

The Queen nodded, and I woke from the spell which the strange scene had cast upon me. I heard the woman's raucous yell of triumph, and her cry to her partner:

"Fine! Switch on the red sign in honor of the Queen, Jim!"

Instantly there flashed out on the African night the following sign:

EMERGENCY EXIT

It was like a hint from above.

I made the swiftest emergency exit on record, Louise. I reached my boat about six jumps ahead of the ungrateful hounds, cut the rope and was whirled into safety and darkness by the rushing current in an instant. But alas, my treasure was back at the Old Flag. The only thing I saved was myself.

APPARENTLY overcome by the sad memory of his defeat,

Captain Cormorant drooped his head in an unconscious attitude of

dejection so profound that his wife was alarmed. She rose and

firmly rang for another bottle of champagne. The Captain looked

up. He straightened his shoulders, beaming at her.

"Yes, best beloved, as I say, the only thing I saved was myself. For a long time I wondered whether even that was worth while."

He reached for the cigar-box. Little Mrs. Louise looked at him eagerly. "And was it, Lester?"

The Captain rose.

"Can you ask, dear heart? Can you ask a man in my circumstances such a question? A million times over it was worth it!"

He knelt down on the hearth-rug beside her, slipped an arm round her, and drew her unresisting form to him.

"God forgive me—moral-less, friendless (except for one great-souled little lady) bit of flotsam that I am, I am the happiest husband in the world."

He snapped his fingers at that far-off treasure in Jaloon.

"And I am the happiest wife, Lester ... And I just adore your stories."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.