RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

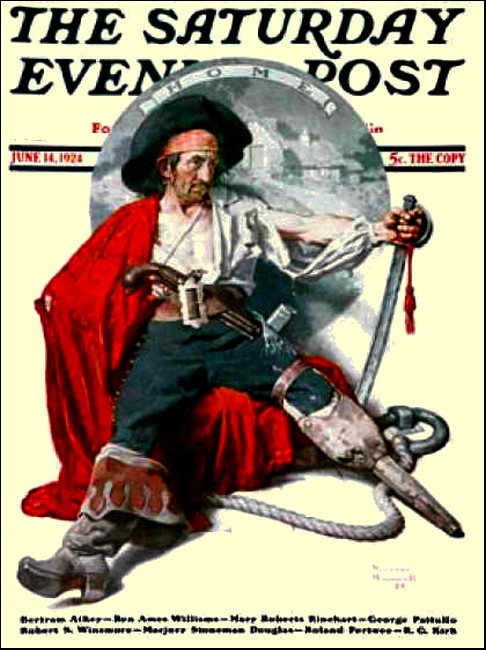

The Saturday Evening Post, 14 Jun 1924,

with first part of "The Pyramid of Lead"

"The Pyramid of Lead,"

D. Appleton & Company, New York, 1925

The policeman, a heavy-faced man of middle age, studied his

questioner for a second or two. "The coroner's jury is about

to inspect the scene of the recent tragedy," he said

importantly.

THE bare-headed individual in grey flannels, grey woollen sweater and travel-stained gym shoes, who, in the company of a small, silver-grey donkey of extremely gentle and sedate appearance, and a very brisk three-legged semi-terrier, had encamped for the night in the old, sun-baked gravel pit which they were now preparing to leave, cast one swift, comprehensive glance around the site of the camp and addressed his companions.

"All is well, my littles," he airily observed, rolling a cigarette as he spoke. "We have left behind us neither orange peel nor broken beer bottles and there are no greasy paper bags, bits of old newspaper, crusts of bread, ham bones, pieces of fat or apple cores to render uninviting this very attractive and homey little gravel pit. That is as it should be."

He moved to the grey donkey, and put a few finishing touches to the arrangement and fastenings of the pack she carried, comprising a very small tent, some jointed bamboo poles and cords, a few light aluminium utensils, a roll of blankets with clothing inside, a fishing rod and various light sundries likely to be required by a gentleman on a sleeping-out tour.

Then he led the way to the exit from the gravel pit, the small grey donkey trotting close behind him.

At the roadside he paused, considering his route.

"Southwards, I think, Patience, for I have an instinct that to the south lies adventure, and adventure is what we seek. Ten days now have we wandered the by-ways but nothing has occurred. We have encountered no ladies in distress, nor have we found villains engaged in villainy, conspirators occupied with conspiracy, plotters plotting, or planners planning. The world grows good and the countryside even more tranquil and peaceable, Patience mine...."

Thus airily prattling, the gentleman in the grey jersey headed, at an extremely leisurely gait, along the lane leading south, one hand resting affectionately on his donkey's neck.

Those with whom he had come into sufficiently close contact during the past few days to render an exchange of names necessary had learned that this friendly-eyed, easy-mannered, youthful-looking person, whose speech seemed ever to be a curious blend of whimsical jest, mild paradox, and kindly intent, was named Prosper Fair and that he was spending a few of the sunny summer weeks wandering about on tour.

Save to the thick-witted, Prosper Fair was very obviously a young man of good breeding, serene and equable temperament, whimsical nature, compassionate, charitable, sympathetic and courageous withal; trusted by his small donkey, who was not such an ass as she looked, and quite obviously adored by his triple-limbed terrier, terrifyingly named Plutus.

Many a time had these wandered far afield in company, and various were the adventures which had befallen them. But this present tour had been in the nature of a failure in so far as adventures were concerned. All had been peaceful in all places and at all times, and though the tour had been joyous, it had also been without thrills—save for the thrill which mealtimes bring to the outdoor wanderer....

"A quiet tour, Patience mine," mused Prosper aloud as they passed at an extremely leisurely pace down the lane, "but, deep down within me, quadruped, I feel stirring an instinct, a premonition of adventure. I have had many premonitions in my life, Patience—most of them wrong—but never one quite so intense or convincing as this of which I am now conscious."

He never spoke a truer word, for it was hardly half an hour later that, on the point of crossing a main road en route to a lane on the other side, Prosper observed the little crowd of carefully-dressed men—for the greater part in decent Sunday black—approaching the lane opening for which he himself was heading.

His gay blue eyes grew a little more intent as he studied the company which in groups of threes and fours followed a man of military appearance who, with two others, was in the van of the straggling procession. Two policemen accompanied the party.

"Left incline a trifle, Patience," murmured Prosper. "Yes, left incline."

The trio moved to the left a little, then halted, and Mr. Fair appeared to busy himself with the rolling of a cigarette—under cover of which operation he contrived to take an extremely comprehensive view of the passers.

When, in a moment, the leaders left the main road and headed down the lane, Prosper stepped forward to the policeman who was bringing up the rear.

"Pardon an intrusion inspired solely by a very human curiosity, officer," he said easily. "Is it permitted to enquire what is taking place?"

The policeman, a heavy-faced man of middle age, studied his questioner for a second or two. Apparently satisfied with his inspection he spoke briefly.

"The coroner's jury are about to inspect the scene of the recent tragedy," he said importantly and moved on.

Mr. Prosper Fair no longer smiled.

"Tragedy—" he repeated quietly, reflected a moment, then glanced about him. A little distance along the road he observed what he evidently sought—a gate leading into a field. He went quickly to this and took his companions into the field, passing round to the back of a haystack near the gate.

"Do you abide patiently in this place, my littles," he said, deftly relieving Patience of her pack. "Wait here in peace— behaving perfectly—while in company with the jury I, too, inspect the scene of the tragedy which has thrust itself upon this pleasant countryside."

As though she understood every word—as, indeed, she did sufficiently well—the little grey ass settled down in the shade of the haystack at once.

Plutus the dog gaped wistfully at his proprietor for a moment, then realised that orders were orders, and he too settled down to a systematic investigation of certain inviting holes at the base of the stack.

"Good—very good. In due course there shall be rewards—eatable ones," said the whimsical Mr. Fair. "Trust Prosper. All in due course. It is irksome, Plutus, yes, but duty was ever irksome. Trust Prosper and all will be well—all will be very well."

He smiled indulgently upon them and strolled away, following the policeman that followed the stragglers that followed the leaders.

In a moment or two he had merged himself into the little company and a few yards farther on found him strolling by the side of the two serious-looking men, both bearded, of small stature, one of whom was quite evidently the local Wesleyan minister and the other probably the village schoolmaster. He saluted these with his accustomed easy punctiliousness which, for all its ease, conveyed perfectly the fact that he recognised them at once as men of worth and intelligence. "A sad occasion, gentlemen," he observed. "Very. Poor soul..." agreed the minister. "Sudden tragedy, even in remote and lawless places is always shocking," continued Prosper. "But to encounter it here on this benign and beautiful countryside is more than shocking."

"You are right," agreed the schoolmaster, a remote irascibility in his deep voice. "And when it repeats itself—when it occurs a second time—it becomes a matter of extreme importance to take steps to prevent a third tragedy."

"Pardon me—did you say the second time?"

"Yes, indeed," corroborated the minister. "You have forgotten, or, being a stranger to the village, you may be unaware of the first case. I mean, of course, the discovery of the body of Mr. Larry Calhoun, the racehorse trainer, dead at the base of the pyramid of lead, in the sunk garden of Kern a year ago."

"Yes, yes, yes!"—the schoolmaster broke in with that vague, distant suggestion of irritability which marked every word he used. "Mr. Calhoun, stone dead on the south side of the pyramid last year. That was the first. And now there is this nameless lady with all those emerald rings—also, mark you, found at the south base of the pyramid. The south base. It is entirely clear to me that the danger—whatever it might be, comes from the south side of that monstrous structure!"

"Monstrous, Hardy?" demurred the minister. They were evidently old cronies.

"Well, unfitting. Yes, 'unfitting' is the better word. I agree. Whoever heard of a pyramid in an old English garden—and a pyramid of lead at that. No. It is an ill thing, my friends—ill-starred, conceived in fantasy, erected in mystery, haunted. I may claim that I am not a superstitious man, but I can almost find it in me to believe that the garden of the pyramid of lead is haunted."

"It sounds ominous, indeed," said Prosper quietly. "May I ask where is this pyramid of lead?"

"In the sunk garden of Kern—Kern Castle, once the residence of the notorious Lord Kern. We are going to it now," said the schoolmaster, crisply.

"The sunk garden of Kern!"

Prosper Fair knitted his brows slightly as he repeated the phrase over to himself—like a man trying hard to fix some half-forgotten and elusive memory. He must have succeeded for his face cleared almost at once.

"But—fantastic! I cannot recall that Lord Kern was fantastic," he said, presently.

"He was undoubtedly eccentric," suggested the minister, mildly.

"Eccentric to the point of fantasy," developed the schoolmaster, eyeing Prosper severely. Mr. Fair promptly disclaimed any but newspaper knowledge of Lord Kern.

He was anxious to gather all that he could concerning this inexplicable pyramid of lead, and though he knew—or was in a position shortly to discover—perhaps a good deal more about the eccentric Lord Kern than either of the cronies could hope to know, it was, he conceived, politic to let them talk, even to encourage their conversation ....

"I spoke from hearsay only," he said.

The minister shook his head.

"Lord Kern was an unusual and to most people, I fear, a formidable character," he said. "I confess that I cannot dwell upon the memory of the few occasions on which I met him with any pleasure. I believe that I am not without some right to claim that I am a charitable-minded man. But I found—it seemed to me—that Lord Kern was hard and secretive. I may say he was—"

"Oh, everybody knows it," said the schoolmaster, rather harshly. "Secretive is a mild word to use in connection with Lord Kern. I am a blunt man. I have always been of the opinion that he was of unbalanced mind. Who but a man of unbalanced mind would erect a pyramid of lead in an old world rose garden of what was once the—the show place of this lovely little corner of the world. A pyramid of lead in Kern village!"

Clearly the schoolmaster had a grievance.

"Yes—one sees that," agreed Prosper, feeling his way. "And moreover, a pyramid that obviously is not safe."

"After dark," supplemented the schoolmaster. "Think! Two people—Mr. Calhoun and this nameless lady have died in the shadow of it with never a mark—or wound or sign of one—to show what caused their deaths! The place is evil, I insist—haunted, sinister—Ah! here we are!"

He broke off as they followed the others through a pair of huge, black iron gates, swung to vast stone pillars each surmounted by a fabulous stone-hewn beast, half lion, half dragon. But big as the gates and pillars were they were dwarfed by the colossal and crowding elms, towering over them, their sprawling upper boughs so interlaced and locked that the moss-grown carriage drive under them was dank and chill and gloomy in spite of the brilliant sun high overhead.

The little procession passed down a long and winding drive, heavily shadowed for almost its whole length, their footfalls soundless on the thick, moist moss. Clearly this roadway had once been a wide and noble approach to Kern Castle—but now the huge, ragged banks of sombre laurel bordering it on either hand had been allowed to encroach and crowd in so greedily that the road was reduced to probably less than half its original width.

"Truly a sombre place," said Prosper, glancing about him.

The minister nodded without speaking. His lips were set. Perhaps he was thinking of those meetings with the owner of this estate at which he had hinted.

"Yes. But at least it is a fitting approach to the castle—as it has become," said the schoolmaster, his voice slightly, and probably unconsciously, subdued.

There was that in the progress of the sombre-clad jurymen upon their melancholy mission through this dark and overgrown alleyway, to chill the spirit of almost any man, and the schoolmaster's hint at the appearance of the castle itself did nothing to minimise or counteract the stealing depression with which the approach was liable to afflict one.

Prosper Fair nodded slightly and dropped a pace or so behind, glancing over his shoulder.

"We shall see the castle as we round the second turning after this," announced the schoolmaster.

"In the sunlight probably it will not look quite so-ruinous," suggested the minister. "I confess that this approach lays a cold hand upon my heart. Do you not feel it, sir?"

He turned, as he addressed Prosper, then stopped suddenly with an exclamation.

Mr. Fair had disappeared.

It was quite a simple disappearance. A moment after dropping behind the two cronies, he had paused, allowing them to round a curve. Then, glancing about him and noting that for the space of a second or so, placed as he was between two bends of the narrowed drive, he was unobserved, he stepped lightly aside, swiftly parted the crowded growth at the left side of the drive, and vanished among the tall, dense shrubs.

The minister was so surprised that he stopped short.

"That's curious, Hardy—our hatless friend has—disappeared, you know."

He pulled at his lip, perplexed. Both of them were staring back.

But a sharp voice a little way ahead recalled their attention and they went on quickly.

At the spot where the carriage drive debouched into the open space before the front of the enormous pile of the castle, which, densely cloaked with an almost incredibly thick mass of ivy, loomed gigantically over the nettle- and weed-grown area that once had been lawn, the jurymen had halted, and one of the leaders, the chief constable of the county, a high-coloured, hot-eyed, elderly man, clearly an old soldier, was peremptorily giving orders to the two policemen.

"Send all these people away at once. Nobody has any duty or business here other than the jury and the officials in charge of the proceedings. This is not a—a show. I will not have the proceedings treated as a spectacle and the coroner hampered by a crowd of morbid sight-seers running all over the place. See to it at once. Send them away and one of you—you, Streeter—post yourself at the entrance gates and keep everybody out!"

He tugged at his stiff, grey moustache.

"If they are so keen to feast their eyes on this—this pyramid—let them come here at night, by Jove, if they have the courage—not shelter themselves behind a body of men anxious to carry out a painful and distressing duty as expeditiously as possible!"

The schoolmaster glanced at the minister—who, though not on the jury, was clearly not included by the chief constable among those he denounced—and concealed a very slight smile.

"I fancy our young friend was quick witted enough to guess that this would probably happen," he whispered.

He was right. Mr. Prosper Fair was a gentleman who for all his suave and gentle manner possessed the art of foresight in rather an unusual degree.

ALTHOUGH Kern Castle was not yet quite so decrepit as justly to be termed a ruin, nevertheless it was far on the way to becoming so. The great building, itself a huddled conglomeration of additions I to the original plain L-shaped castle, was so densely smothered in rank ivy that little more than a rough idea of its general outline was obtainable. Weeds were growing vigorously everywhere about it, weeds and nettles and docks, a few stubborn survivors of long neglected perennial flowers, seedling trees, creepers and such indomitable vegetation.

Many of the windows visible through the tiny spaces not yet filled by the tenacious and unconquerable ivy lacked panes and resembled dark recesses, cowled in heavy greenish drapings, rather than windows. The great main doors were closed, the broad, shallow stone steps leading to them were carpeted with mossy grass, and the columns of the great portico were hidden entirely by a straggling mass of ivy-strangled roses without bloom. At the apex of the great place a flagpole spired high into the air—but it was broken, snapped off midway, and served only to emphasise the general air of ruin and desolation.

The jurymen, shepherded by the peremptory chief constable, the coroner, a quiet man with an impassive face and very steady eyes, and a third person, ruddy, breezy, well-dressed, whom the others addressed as "doctor," did not linger at the main entrance front of the castle.

They passed quickly around, making their way over a wide, overgrown terrace walk, to the south side.

Here, at the end of a winding path between two huge, unkempt yew edges, very old and enormously thick, they came presently to a small opening or exit from the yew walk, which brought them out at the sunken, stone-flagged garden which they sought. There was an involuntary pause on the part of most of these men—mainly respectable villagers, each with sufficient knowledge of gardening to realise what a place of sheer beauty this spot must once have been and, with a little skill and care, could be again.

"The sunk garden of Kern, Mr. Coroner and gentlemen of the jury," said the chief constable, his voice dropping a little, "some of you may have seen it in its happier days—years ago. It was unique, then—could be so again."

He was the possessor of a fine and fastidiously cared for property himself, and he shook his head rather sadly as he gazed about him, tugging at his close cut moustache.

Two tragedies had happened in that place during the past year and now, in its deserted, lonely and neglected condition, it looked indeed a fit setting for tragedy.

It was in the form of a great rectangle, fully two hundred yards long, by fifty wide. This space was hemmed in on every side by massive hedges of ancient yew, nowhere less than twelve feet high, which once had been almost mathematically squared and trimmed, but which now were in the same neglected and riotously overgrown condition as the rest of the garden.

From a wide flower border at the base of the yew hedges, running parallel with the hedges, were broad stone-flagged walks extending in width to, and their inner edge forming the brink of, a sunken stone-paved rectangle, perhaps three feet below the level of the walks. At both ends and at several places along the sides, wide, irregular steps gave access to the "floor" of this garden. Everywhere, in every cranny and crevice, still clung the survivors of an amazing variety of rock plants, but the weeds were slowly conquering all these, as they had long ago conquered and killed the plants that once, in the flower borders, had made a radiant glory of colour against the sombre background of the dark hedges. There had been many roses there years ago, but these had long run to riot, and where peacocks had strutted on the stone walks there was now only a tangle of weeds and briars.

Down in the sunk garden itself, the fountains, the sundial, the urns, lead figures and stone benches that long ago had made it beautiful still remained but the shadow of desolation and decay was on these too. Some had fallen and lay where and how they had fallen, but one hardly noticed these, for, dominating the whole of the garden, squatting, ugly, bizarre and foreign, in the exact centre of the garden was the pyramid of lead. Dull grey in the sunlight, wrecking the symmetry of the entire place, the mass of metal rose upon a quadrangular base that reached more than two-thirds of the way across the garden. In height it rose considerably above the topmost level of the yew edges, but because of the breadth of its base it gave only an impression of squatness, as it might have been a low, grey, ugly, polyhedral excrescence upon the stone floor of the garden—a fantastic tombstone designed for the grave of some not less fantastic giant. No entrances were visible and the faces of the pyramid were perfectly smooth, save only for four inscriptions, one upon each face.

The schoolmaster had been right in his description. It was a monstrous thing to put in such a place—hideous, remotely eerie, chilling and utterly destructive of all beauty there. It was like coming suddenly upon the grey side of a battleship at the end of a rose walk.

Such was the structure erected for no reason known either to his few friends or his enemies by the seventeenth Baron Kern some years before his strange disappearance from England in the early part of the year 1914.

The jury walked slowly round it, reading the inscriptions deeply incised upon the dull grey faces of the polyhedron. They were simple quotations from the Bible, full of meaning in themselves though their connection with, or relation to, the pyramid itself was as darkly obscure and inexplicable as the reasons which had inspired the eccentric peer to erect it in his garden.

That upon the north side ran:—

AND THOU EVEN THYSELF

SHALT DISCONTINUE FROM

THY HERITAGE

THAT I

GAVE THEE

On the south side was this:—

THEY THAT MAKE A GRAVEN

IMAGE ARE ALL OF

THEM VANITY; AND

THEIR DELECTABLE

THINGS SHALL

NOT PROFIT

The eastern face bore these words:—

I WAS A DERISION

And, lastly, on the west side:—

A GOOD NAME IS RATHER TO BE

CHOSEN THAN GREAT RICHES

AND LOVING FAVOUR

RATHER THAN

SILVER AND

GOLD

It was on the south side that presently the jurymen were marshalled to stare at a place on the stone flags which the chief constable pointed out, and to listen again to the coroner's brief résumé of the subject of their enquiry. With a certain skill, the result of grim practice, he made all clear.

The body of a well-dressed woman, something under middle age, had been discovered lying there by two boys who had ventured into the sunk garden bird's-nesting three days before. The medical evidence proved that she must have been dead for at least twenty-four hours but it could provide no reason as to the cause of death. Externally there were no signs nor had a post-mortem revealed anything beyond a slightly unsatisfactory condition of the lungs.

Beyond a few pound notes and a few odds and ends—none of which gave any indication of the identity of the dead lady— nothing of interest was found in her handbag. The coroner referred to the unusual number of rings which she was wearing—all being set with large and perfect emeralds of very considerable value. Her clothing was of extremely good quality, but bore no markings likely to aid any one seeking to discover her name. One curious point of which the coroner spoke at some length was the existence of a wound in the palm of her hand—a sharply cut incision about three quarters of an inch in length. It was inconceivable that this wound could have caused her death--but the fact that the weapon or instrument which caused it had passed first through her glove, rendered it conceivable that she had received the wound either in the sunk garden or close to it. Otherwise, he suggested, the wound would almost certainly have been bound.

But no weapon had been found by the police....

The jury listened in silence, their eyes for the most part on the inscription on the south face of the pyramid.

Presently, satisfied with their inspection, they left the garden to return to the village hall in which the inquest was being held.

Deserted, desolate, ruined, the sunk garden lay hushed within its gloomy walls of yew, the great pyramid looming over all.

Here and there a bird flickered across the wilderness of weeds, a few small lizards crept out to bask again in the sunshine, and, in one place, sinister, venomous and ugly, a large red adder wound slowly from a crevice to coil on the hot stones.

The tall foxgloves and nettles stood motionless in the still air and it was as though that place had been forever abandoned to the sun-drenched solitude that possessed it.

But presently the solitude was invaded. Within ten minutes of the departure of the jurymen a slender, wiry, grey figure appeared silently at one of the overgrown, masked and almost obliterated arches in the great yew hedge.

It was Mr. Prosper Fair.

He came quietly out, passed across the stone walk and went lightly down the steps, moving towards the pyramid of lead. He walked slowly round the dull grey mass of metal, reading the inscriptions, noting them in a little book, and, having circled the pyramid, stepped a few paces back, and sat upon the low stone wall.

Without taking his eyes from it, he made himself a cigarette, lit it, and seemed to lapse into a curious trance-like study of the pyramid.

Fair's face was very serious.

"Two people—first Mr. Larry Calhoun, a trainer of racehorses, next a Nameless Lady with emerald rings and a wounded palm," he said softly. "If it had been one only, one could attribute it to misadventure. I can believe that this place is not without a fascination for a would-be suicide—lonely, remote, shunned. But two is—one too many."

He drew a deep breath of smoke and expelled it, absently watching the grey plume fade in the warm, still air.

"They came here with a purpose—a motive. It should be possible to discover that motive... one would imagine that there would be indications of some kind—"

His eye caught a pin-point glitter from under the gay spire of a foxglove that had established itself at a spot a few feet back from the centre of the south base of the pyramid of lead.

He rose, went across, and stooped. The glitter of reflected sunlight resolved itself into a tiny fragment of curved glass—nothing more. He picked it up, noted where he had found it, put it carefully away in a matchbox, and began a slow, systematic walk round the sunk garden, his eyes on the ground.

Presently he stopped, studying one of the flights of broad, stone steps leading down into the garden from the flagged walk under the yew hedge.

"For example, why do the weeds grow less thickly over these steps than over the others," he asked himself.

He bent over the steps.

"Here we have a few tufts of dead weeds—no, rock plant. Some one seems to have pulled them from their crevices about the middle of the tread and thrown them aside. Why? If I were desirous of sitting down on these steps in the sunlight, is it conceivable that I should remove the greenery from the place where I intended to sit?... Only if I were arrayed in white flannels, I think—or if I were a lady, in a white summer frock."

He bent lower over the steps, examining them closely.

In a few moments he began to pick out from among these creeping rock plants several minute objects, which he presently held out in the palm of his left hand and studied attentively. They were tiny bits—shavings—of slightly curled wood.

"Some one has sharpened a pencil here within the last few days—a pencil coloured with dark blue varnish," he murmured.

"Indications, possibly," he said to an inquisitive robin surveying him from the edge of a low stone vase close by. "But it would be simpler if you could speak, my friend. You have the air of one familiar with this garden—you look a frequenter—possibly even a resident of this place. Who has been sitting on these steps in fresh, clean white clothing, and sharpening pencils here?"

He stooped sharply, and picked carefully from a crevice a bronzed hairpin.

"One would assume that it was a lady," he continued. "This becomes interesting," he said, glanced at the watch on his wrist, thought for a moment, then nodded to the robin.

"I shall return, redbreast," he informed the bird and turned away towards the arch by which he had entered the garden.

He paused an instant as he passed the eastern side of the pyramid.

"'I was a derision,'" he read aloud. "That, at least, is an unexpected confession for the last of the Kerns to make—if all that one heard of him is true...."

He moved on, thinking.

"It is quite conceivable that the key to the mystery of these two deaths is to be found in those inscriptions," he told himself as he passed out of the garden and disappeared into the jungle of shrubs and tall trees beyond the yew hedges.

Perhaps it was as well that he left the garden when he did, for within five minutes of his departure two men came through the larger entrance which the jurymen had used.

One of these, a tall individual of perhaps thirty-eight with a dark, keen, intellectual face, was wearing a well-cut suit of golf clothes. He appeared to be acting as a guide to the second man—a hard-looking person, years older than the man in the golfing suit, with the odd, reserved, watchful air of the professional plainclothes detective the world over.

"It is many years now since I had any right to come to this place," said the man who looked like a barrister on a golfing holiday. "But if my knowledge of it is as it used to be in the days when Lord Kern lived here—or, for that matter, of Lord Kern himself, is likely to be of any use to you, I shall be very glad to answer any questions you like to ask."

The detective nodded, his hard eyes roaming about the garden.

"Thanks, Mr. Barisford," he said. "In a case like this anything we can ascertain about the people concerned is bound to be useful."

His glance had come to rest on the pyramid.

"Lord Kern was said to be extremely wealthy, wasn't he?"

Barisford smiled slightly. His eyes were never quite free from a deep, lurking humour.

"Oh, yes. It is no secret that his fortune amounted to something in the neighbourhood of a million and a half."

"And yet they say he was most miserly, the most miserly peer in the country," continued the detective.

The other agreed with an appearance of some reluctance.

"He was ludicrously parsimonious, yes."

"But, nevertheless, with lead worth—how much?—twenty pounds, perhaps?—a ton, he built that thing! There must be tons of it there—tons. It must have cost thousands. Did you ever get a glimmer of an idea why he built it?"

Barisford shook his head.

"Not the least. I was his secretary for four years—living mainly at his town house—but at the end of that four years I knew no more of him—of his private thoughts, or ideas, of his real personality, than I knew at the beginning. Lord Kern was the most intensely secretive man I have ever met. But that's notorious, of course—his parsimony and his secretiveness."

"Yes—almost everybody had heard of that even before he disappeared," agreed the detective, moving to go down into the garden. "It's a pity. If you could have told me why he squandered his precious money on that big block of metal it might have simplified things right away."

"Yes, I see that. I wish I knew. But I don't. I've conjectured—puzzled—for hours about that. Like thousands of others. But I've got no nearer the solution than anybody else—though I agree with you that when we know the reason why Lord Kern erected this pyramid and disappeared, I believe we shall not be far from discovering the cause of the deaths of those two unfortunate people—if, indeed, they died from abnormal causes."

The man from Scotland Yard nodded.

"I'll take a look round now," he said, and passed down the steps.

The man who had once been secretary to Lord Kern took a cigarette from a silver case, sat on the steps and watched him idly, his eyes full of that curious, attractive good humour which gave him an appearance of always being about to smile.

IT was high noon before Prosper Fair rejoined his little comrades at the back of the haystack, for since he left the place of the pyramid of lead he had contrived to attend the closing stages of the inquest and even had obtained a view of the body of the Nameless Lady. His face was grave and his eyes were blank and preoccupied as he rounded the haystack. All his life long Prosper had been tender and gently disposed towards women because he believed that life was more difficult for them than for men. Much trouble, time and money had this tendency cost him but he regarded all that as well spent.

"It has been my good fortune to help make many women a little happier and I shall always be very glad of that," he would say sometimes to Patience. "And I believe—though I would say this to nobody but you who can keep a secret so well—that women like me and trust me. That is not so bad, Patience—not so bad, though sometimes it can wring one's heart...."

He would stop there, his clean-cut mouth a little wry and uncertain, for it was not more than three years since the day he had knelt beside the bed of the dearest woman of all to him, his face buried in his hands—though neither she, his wife, nor the small son she had seemed to hold so closely to her, had known that he was there....

Something pitiful, some vague, haunting suggestion of wistful protest that he had fancied he could see on the face of the Nameless Lady had moved him very much. And this, together with the voiceless challenge of the great pile of grey metal to solve the mystery of its existence, the puzzle of its strange inscriptions, had impelled him to match his intelligence, his courage, and his tenacity against this hitherto unsolved problem.

It was not with any expectation of such grim adventure that he ever set out from his home upon his wanderings in the prosecution of what he was wont gaily to term his ceaseless "study of humanity." Far less serious adventures had contented him hitherto.

But never among these lesser matters had he encountered one which called so insistently or urgently for his wholehearted intervention as this mystery of the pyramid of lead....

He stood for a moment surveying his comrades with absent eyes.

"There is no puzzle without a solution—for if there were no solution there could be no puzzle," he said. "Do you see that, Patience?... For myself, I see no reason why there should not be a perfectly simple, though possibly sinister, explanation of these tragedies—provided one erects one's fabric of reasoning upon a sufficiently accurate basis. I shall try to do that."

Thoughtfully he moved out of the field, across the main road and into the by-road which ran past Kern Castle.

He turned off into the woods just beyond the entrance gates and worked his way round to the south front.

Here in a little clearing on the edge of the ancient woods bounding the belt of wild growth between the south yew hedge of the sunk garden and the woods, he pitched his camp, fed his comrades, and ate his own midday meal.

This done he drew from his haversack and carefully spread out before him on a handkerchief his little array of trifles found in the garden that morning.

"Let us begin at the beginning," he told himself. "Which, at present, seems to me to be some years before the departure of Lord Kern from England in the year nineteen hundred and fourteen." He shut his eyes, frowning as he concentrated on the effort clearly to remember all that he had ever read or heard of the eccentric nobleman. Prosper, as may in due course be seen, had encountered in his career many opportunities of knowledge—intimate knowledge—concerning the aristocracy denied to the average man. Gradually many details came back.

"If everything one read and heard is to be believed the passion of Lord Kern's life was money—a miser's passion, not a gambler's. I remember that it was said that he had sold practically all his property except Kern Castle, its big park and grounds, and his town-house, in order to possess his great fortune in liquid or at least easily secured cash. For years he lived that way—mean, lonely and unmarried, the last of his house."

Prosper nodded.

"Then suddenly he seemed to change. He launched out into a brief career as a man about town—a decidedly middle-aged one. He was seen at theatres, races, dinners, dances, smart restaurants, and some of the clubs. His town house was redecorated and he began to entertain on a lavish scale—when abruptly he seemed to repent sharply of the new life, and instantly reverted to what he had been before—a grim, hard and bitter miser...."

Sitting staring blankly before him Prosper distilled that ancient gossip from his brain bit by bit.

He nodded again, as though to encourage himself.

"What came next?" he muttered. "If I remember correctly it was published some time after that he had retired from his social interlude to Kern Castle, lived there for two years or so, quietly and obscurely, during which time he built the pyramid of lead. Then he suddenly left England and went to America—or was it Australia?"

He scowled in his intense effort to remember.

"America, I believe. And he never returned—obviously. From the day of his disappearance to this, nothing more has been heard of him—by the general public, that is. But one may presume that he is still alive. There must be solicitors, agents, or somebody watching his interests. I shall have to find that out,"—here he made a note. "But judging by the condition of this place the powers of these solicitors must be strictly limited, for it is clear that nothing is ever done to check the slow decay, the inexorable ruin that presses day by day more heavily, more darkly upon this noble inheritance—"

Prosper stopped suddenly, like one who hears a distant sound, and slowly repeated his last sentence—

"...to check the slow decay, the inexorable ruin that presses day by day more heavily, more darkly upon this noble heritage of Kern—

"It is very evident that, wherever he may be, Lord Kern is no longer interested in a place which must have been perfect when he first possessed it—'this noble heritage of Kern'"—he quoted himself.

The word vibrated a string in his consciousness.

"Heritage! Heritage," he murmured and glanced at his notebook, reading aloud.

"And thou, even thyself, shalt discontinue from thy heritage which I gave thee!" Word for word he repeated the inscription on the north face of the pyramid of lead.

"But that's curious," said Prosper. "It is apt—as far as discontinuing to enjoy the castle he inherited is concerned. It seems as if this slow decay, this abandonment of Kern to ruin, is deliberate."

He reflected.

"I believe that I have gained a little point—captured a very small pawn," he said. "I will assume for a little that Lord Kern is deliberately letting this place fall to ruin...."

He considered that for a moment, but, at present, it led him nowhere. He put it aside, and tried another tack.

"The sunk garden of Kern has an evil reputation and few, if any, of the villagers—including, after this last tragedy, even bird's-nesting boys—will go near it alone in broad daylight, and certainly not at night. Yet some woman goes there, sits upon those steps and lingers there—at leisure, for no woman in a hurry chooses that moment as a time for sharpening a pencil. It will be necessary to discover who she is, why she goes there, and why the pyramid of lead does not awe or appall her as it does the villagers of Kern."

He put away the shavings and the hairpin and studied the curved fragment of glass. The shape of this puzzled him. It was obviously not a fragment of sheet glass, nor of a broken bottle, nor was it part of a tube or lens. It was too thin for any of those things.

He came at last to the conclusion that it might be part of an electric light bulb, though how it came to be in the sunk garden he could neither judge nor guess. He decided to ascertain if the castle was provided with an electric plant.

"It may be from an electric torch bulb—but with so wide a curve it would have to be a very large torch indeed," he said and restored it to its matchbox. He rose, then closed the flap of the little tent and notifying the electric Plutus that he must remain behind, he began to make his way through the jungle of undergrowth and bramble-choked shrubbery dividing the woods from the south yew hedge of the great sunk garden.

He purposed passing through this on a short cut to the village.

His progress was slow and tormented with snaky briars, tough as wire cables. It took him half an hour to make the rudiments of a path through. In the south yew hedge, the one to which he was making his laborious way under the hot sunlight, were two arched entrances cut one at each end. Mainly because the village beyond the castle lay somewhat to the left, Prosper headed for the left entrance, intending to cut diagonally across the western end of the garden.

As he neared the entrance he went more cautiously and silently—not that he considered it really necessary but simply because it was just conceivable that the lady of the steps might be there on this gloriously sunny afternoon. He believed it improbable—but the fascination of the problem was enmeshing him closely now, and his mind was not of a quality which rendered him liable to carelessness or incapable of estimating possibilities.

His precaution was surprisingly well repaid.

As he came to the hedge he paused, glancing through the unpruned, growth-narrowed entrance towards the steps which had caught his attention. These were quite close—no more than the width of the stone-flagged walk separated them from the hedge.

He drew back instantly.

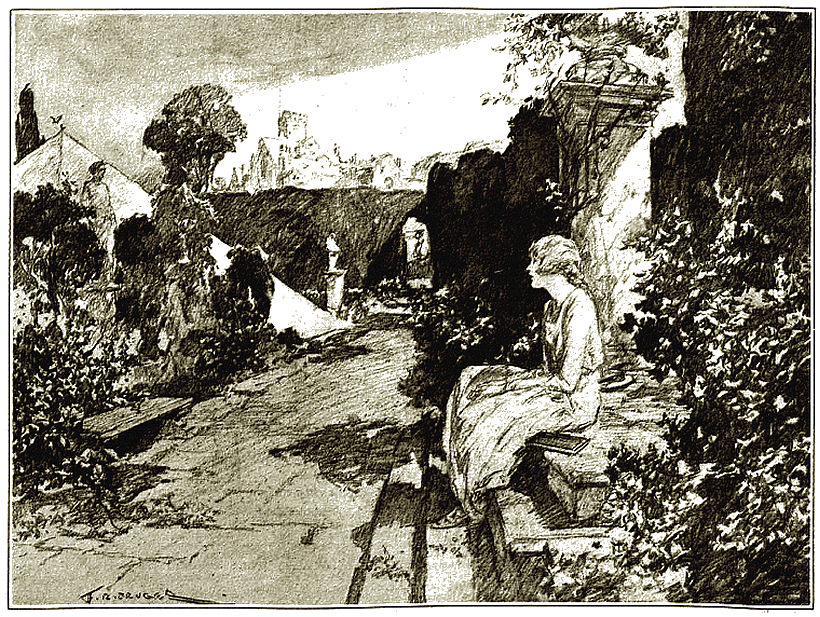

A girl was sitting on those steps, gazing dreamily before her. By her side was a sketch book, but she was not using it. She was sitting at such an angle that she could see the pyramid of lead, squatting heavy and grey and monstrous away to the right.

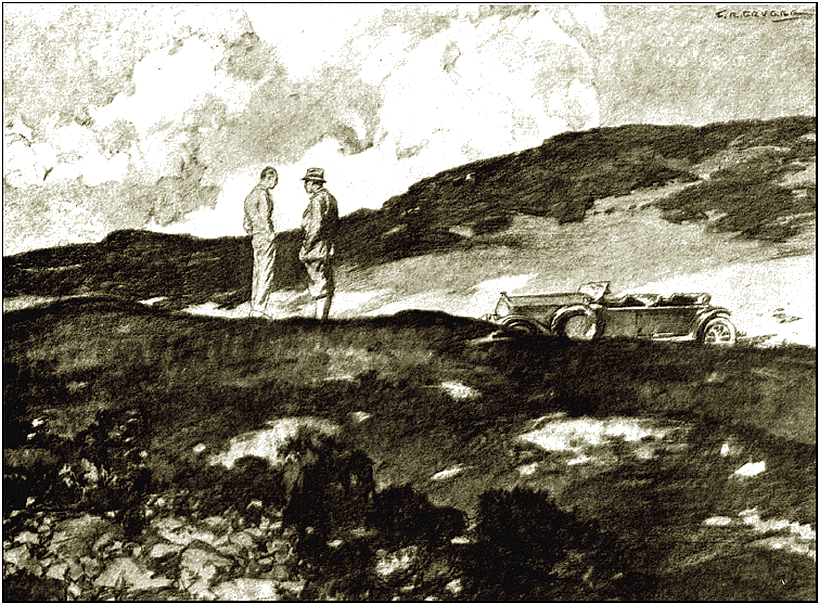

A girl was sitting on those steps, gazing dreamily before

her. She could see the pyramid of lead, squatting heavy and

grey and monstrous away to the right.

Very carefully Prosper looked in again.

A big garden hat lay near her on the steps, though she sat full in the sunshine. He could see only her profile, but that was enough to acquaint him instantly with her beauty. She was fair, very fair, with pale gleaming hair and even had he not known her to be young by reason of the careless, silky plait into which her hair had been gathered, he could not have missed the sheer youth in the unconsciously graceful pose of her slim body; and there was youth as well as loveliness in the delicate outline of her perfectly balanced chin and lips, nose and forehead. She was dressed in a white garden frock with a touch of blue here and there, and she was looking up, her lips slightly parted—as though studying the top of the pyramid. Prosper glanced at that monument and saw that she was watching two thrushes that had alighted on the pyramid—a hen and a late fledgeling on its first flight. Then, even as he looked, a shadow slid across the garden. The girl saw it and glanced up. A big kestrel had drifted on still vans over the pyramid. She stood up quickly, fluttering her hands.

"Oh, fly away!" she called in an urgent but most musical voice. The thrushes, alarmed, fled into the yew hedges even as the kestrel stooped for the fledgeling like a falling bolt of red steel, curving up with an angry scream of disappointment just as it seemed about to smash itself on the metal summit.

The girl laughed aloud with pleasure and sat down again. Prosper thought her exquisite.

And she must be courageous too—for it was very evident that she was wholly without fear or nervousness alone in this place. He scowled unconsciously as it came to him that she might be in real danger. Two victims already the pyramid had taken—what was there to save this lovely child from becoming the third?

"She may be day-dreaming in the shadow of death," he said to himself.

He watched her like a charmed thing.

"She must know that this place is—is perilous—" he began, and was on the point of rising from his ambush when a footstep on the stone walk caught both the girl's and Prosper's attention simultaneously.

He saw her look quickly down the garden. She did not rise and she showed neither alarm nor surprise.

A moment later the newcomer paused by the steps, slightly raising his soft felt hat. Prosper, watching intently, saw that he was a short, powerful man in a dark grey tweed suit. He was clean shaven with a rather heavy jaw, tight lips and hard, piercing, light grey eyes. He was scrutinising the girl intently.

"You'll excuse my venturing to interrupt you in your sketching, Miss," he said, in a flat metallic voice.

"But as you're probably a stranger about here, I think it's my duty to warn you that this is—not the best of places for a young lady to come to alone for an afternoon's sketching." Behind the friendly tone was a hint of both warning and authority. But the girl only smiled.

"Oh, thank you for warning me, but, you see, I know this place very well indeed. I live quite close. And I know about the—sad things that have happened here, too. But I have been used to coming here for years and I am not afraid or nervous. I have no enemies, you see, and I don't get into mischief," she laughed softly—"and so no one is likely to want to hurt me."

A certain admiration made itself apparent on the hard face of the man from Scotland Yard—for this was he—but he shook his head.

"Well, although I don't want to spoil your pleasure, Miss—Miss—"

"My name is Merlehurst," she said, smiling, "and I live quite close—midway between the castle and the village."

The detective nodded but persisted.

"There are still some people about who are enemies of all the world, Miss Merlehurst," he reminded her. "Do your friends—your parents—know that you come here alone? You need not mind my asking—I have a kind of right—"

"Oh, yes, they know. And I, too, know that you have a right to warn me—you are the detective from Scotland Yard who is enquiring into the mystery of those poor people who—who—died here." Her voice sank and was troubled as she spoke. He stared.

"How did you know that?" She laughed again.

"Oh, but don't you understand what country villages are like? Every one knows already that you are Inspector Garrishe of Scotland Yard."

"Oh, do they?... But that doesn't make it any safer here for you alone, Miss Merlehurst. And—forgive me—have you any real right to be here? That has to be considered, too, you know."

The lovely laughing face became more serious.

"I have more right to be here than perhaps you think, Inspector Garrishe," she said.

"May I ask what that right is?"

"Oh, yes. Everybody in Kern knows it. You see—if Lord Kern does not return here within ten years from July nineteen hundred and fourteen, Kern Castle and everything Lord Kern possessed becomes my property."

The detective gave no sign of surprise. He seemed to know something of that already. But it was with some interest that he answered.

"Oh, so you are the young lady referred to in that celebrated deed of gift."

She nodded.

"I thought you would be more surprised," she said naively. "You have heard of that before?"

"Yes—a good many people have heard rumours of it who have never met the fortunate young lady who will benefit by it. So that is why you are not afraid to come here."

She considered.

"Perhaps it is. I don't know quite. But somehow I don't think this beautiful old garden is unfriendly to me. I love it and I always feel that there is nothing in it that wants to hurt me."

The detective said nothing for a moment. He seemed to be thinking.

Then, like a man who has come to an abrupt decision, he asked:

"Will you answer a question that perhaps you may feel I have no business to ask you, Miss Merlehurst? I assure you that I ask it in the interests of the law, and for the sake of those poor souls who died here—as well as, in a way, for your own sake."

She looked at him, her blue eyes wide and steady.

"Ought I to promise to answer?" she said. "I don't think I should promise—but I will try to answer it. What do you wish to ask me, please?"

"Why did Lord Kern name you as the one to inherit this place in the event of his never returning? You must have been quite a child when he disappeared."

She answered that at once, frankly and openly as a child.

"Truly, I don't know. I have often been asked that. I was only a little girl when Lord Kern disappeared and I have never seen him in my life."

The detective reflected.

"How old are you now?" he asked abruptly. "I am eighteen."

"That would make you about nine when Lord Kern disappeared."

"Yes."

"May I ask your full name?"

"Oh, yes. Marjorie May Merlehurst. Do you like that?" she asked with a little laugh, half shy, half mischievous.

"Like it—why, of course he likes it. It's music," said Prosper under his breath. He was enchanted with the girl—but still not so enchanted that he failed to notice the entry into the garden of another man—a tall person, in golf clothes.

"Here is Mr. Barisford, a friend of mine, who used to be secretary to Lord Kern," said the girl. "Perhaps he could help you, inspector."

But it proved that Mr. Barisford could by no means help the detective with any information concerning the reason why Lord Kern had named Miss Merlehurst conditionally as his successor.

"The thing is as wholly a mystery to me as to Miss Merlehurst, or her relatives or anybody else, inspector. If you can find out his reasons for doing that, there are quite a number of people who will be grateful to you."

"And I shall be one of them," chimed Marjorie May in her clear, sweet musical voice.

"Well, there must be a reason," said the inspector thoughtfully. "But I shall have to hunt for that another day," he added. "Just at present I am going to be busy in the castle if you are ready to show me over it, Mr. Barisford."

"Perfectly ready," declared Barisford. "But as I stated when I promised to act as guide I can accept no responsibility for—er—'forcing an entry,' don't you call it."

The detective chuckled.

"Ah, I'll be responsible for that," he said. "I understand the law about 'forcing entries.'—"

"Oh, please—" began the girl, but broke off.

"Yes, Miss Merlehurst?" encouraged Inspector Garrishe.

"I was wondering whether it was possible for you to permit me to come, too. I have never yet been inside the castle."

The detective agreed readily enough—so readily that he might almost have had some motive. But if he had he certainly gave no sign of it, and presently they all moved away down the garden towards an exit leading to the castle.

For a few minutes Mr. Prosper Fair stood, thinking deeply.

But his thinking brought him only to the conclusion that the sooner he gleaned the very fullest information available about Lord Kern the better.

He returned quickly to his camp, retracing his trail with the quick-eyed confidence of a man at home in the wilderness.

Here he settled himself, with writing pad and pencil, leaning against a big tree trunk and wrote diligently for some minutes.

He re-read what he had written, then turned to his companions, Patience and Plutus, and addressed them:

"If you were able to read these letters, my littles, it is just possible that you would agree that the uncomradely act which I am on the verge of committing is justified.... My dears, I am going to send you home, and to work singlehanded. There is that suggesting itself in this matter of the pyramid of lead which is ominous and dark and sinister. And it is no desire of mine that you should share such danger as seems to me to lurk like a deadly, silent, merciless and inexorable thing in ambush about this ill-starred garden of Kern—the stark spirit of murder, backed by infinite stealth and cunning, inspired by some strong and ruthless and pressing motive... which I have to discover. So by reason of the danger—and other reasons—we shall part for a little. We have had a generous share of light-hearted adventure at various times—but there is nothing light-hearted in this adventure. So a brief parting will be arranged just as soon as I can send a telegram. Trust Prosper—and all will be well."

He rose again and headed definitely for the village, making a wide detour of the castle and its grounds.

His face was grave—even a little grim—as he walked through the wood. All that he had said—ostensibly to Patience the donkey and Plutus Three-Legs, as was his custom but, actually, by way of self-communion—he believed.

He had first come to see the pyramid of lead with an open mind, in a spirit of enterprising curiosity, but already he was far from that point.

Here, in a space of a few hours, he had sensed that there was indeed a mystery—and a dangerous mystery—about the great, grey, forbidding pyramid dominating the sunk garden. Somewhere in the opaque fog of that mystery moved an intelligence, swift, tenacious, formidable—an intelligence that could discriminate.

"Yes, that is so," he told himself. "There is purpose driving the hidden intelligence that lurks within the veils of the mystery—and power to discriminate between persons—to select victims. Why is it that beautiful, graceful child is safe in the garden—and seems to be very well aware of it—whereas Calhoun and the Nameless Lady were—fair game?"

He was asking himself this question, without guessing, even dimly, at a feasible answer until he reached the post office.

It was here, in the centre of the village street, that he first saw the person of whom ever afterwards he thought as the Iron-Grey Man.

This one rounded the corner on which the post office stood and halted just as Prosper was about to enter the little building.

"Forgive me," he said, in the voice of one well-bred, "I am sorry to delay you but I should be grateful if you will tell me the way to Kern Castle."

"To Kern Castle? With pleasure. Let me see now—um!"

Prosper reflected, studying the man. He was not less than six feet two inches tall, desperately lean, very upright, and his height was accentuated by the long, faded, grey frock coat tightly buttoned round his frame. He was clad wholly in shabby grey. His boots, long, narrow, and badly cracked, which once had been of black patent leather, were greyish white with dust; he wore a stained top hat which had once been grey; and his hollow-cheeked and haggard face was grey, though with an ugly flush on each of the jutting cheek-tones. His hair was iron-grey, his moustache of the same hue, and his eyes were pale grey also.

He waited patiently for Prosper to speak and it seemed that he swayed a little as he stood there. Clearly a tramp—it needed no more than a glance at his ruined clothes to glean that—but the sort of tramp who has once been a gentleman. For a moment Prosper could not quite "place" him. Then, suddenly, he realised that this weird wanderer looked precisely as a man might look who, dressed in the height of fashion for a day's racing at Ascot some years before, had left some smart coach on the race-course and taken to the road forthwith—even as he stood. Since then the sun, the wind and the rain had been corroding what once must have been an appearance of extreme "smartness" to its present condition.

"Kern Castle is empty—untenanted, you know. I believe that it has been unoccupied for years," said Prosper, watching the Iron-Grey Man.

"Quite so—I understand that, thanks." Suddenly he closed his eyes tightly and kept them closed.

"Forgive me if these closed eyes give you an impression of—queerness It is a habit I have when I am fatigued."

"—and hungry and thirsty," mentally added Prosper to that.

"I shall be able to open them in a few moments, you understand—feeling refreshed. Strange, that—isn't it?" continued the Iron-Grey Man in a voice of inexpressible weariness. "It was always so with me. I am sorry."

Prosper took one of the bony claw-like hands and forced into it a tightly folded wad of crinkly paper.

"It is probably something to do with the nerve centres," he said casually, and added quietly:

"The entrance to Kern Castle lies half way down a lane which is the second turning to the right.... But the entrance to the local inn is three doors along on the left. My friend, if you do not go to that inn first and eat and drink and rest, it is questionable whether you will ever reach Kern Castle.... Give a man well acquainted with the trials and vicissitudes of the road an opportunity of repaying many kindnesses he has experienced also on the road. If you are willing I will join you there within the space of a few minutes."

The Iron-Grey Man swayed.

"Sir, you are incredibly kind," he said. His lids opened suddenly.

"Let it be as you wish," he said and moved on towards the inn.

They were slow at the post office and it took Prosper a full ten minutes to get his telegram off.

Then he hurried to the inn to improve his acquaintance with the iron-grey apparition.

But he was not there—nor had he been there. Prosper was astonished to discover that this information seemed most unaccountably to disturb him.

"But he was quite staringly in the last stage of exhaustion!" he said to himself and went out, oddly worried.

There was no sign of the Iron-Grey Man anywhere along the empty deserted village street.

But an enquiry put to a placid woman standing in the doorway of a little general shop opposite made things plainer.

"Yes, I saw him. He was standing outside the Kern Arms when the baker's van stopped with the bread. I thought he was a funny-looking sort of a tramp. He bought a loaf off the baker's boy and I suppose he asked for a lift. Leastways, he drove off with the boy."

"He wanted to go past Kern Castle," said Prosper.

The woman nodded.

"The baker's van goes round by that way this afternoon," she explained.

Prosper thanked her and headed for Kern himself.

PROSPER was busy at his camp for an hour or so, then, leaving all snug, he set out with Patience and Plutus for a spot some two miles west of Kern village. No doubt he had ample reason for wishing to separate from them quietly, unobtrusively and without witnesses, for that certainly was how the parting was achieved. The only witness was the very smart driver of the closed motor shooting-brake which drove up to the spot whereat Prosper and his humble friends waited, some two hours after he sent off his telegram.

Clearly, Mr. Fair was a gentleman with greater resources at his command than one might have expected from the circumstances in which he had entered the village of Kern.

It took some time to accomplish the parting with Plutus the three-legged, though Patience took it with the wistful and philosophic resignation which one would expect to find in a well-behaved donkey.

But at last it was achieved, and taking a suit case which the chauffeur had brought, Prosper bade him return whence he came, and prepared to do the same himself.

"You will miss them, my friend," he told himself a quarter of a mile on. "Particularly that three-legged electric spark of a terrier."

He need not have worried. A little further on he chanced to look round.

The "electric spark" was trotting three-leggedly along at a discreet distance in the rear—one eye on Prosper for caution—one eye on the hedgerow for sport. How he had got out of the car Prosper never knew. Like those of small boys, the movements of small terriers are mysterious and unexpected.

Prosper shook a friendly fist at him, but Plutus merely insisted on regarding that as an approval of his manoeuvre.

He rejoined his master forthwith.

"Very well, old Indomitable. But you have doomed yourself to a silent few weeks, young fellow. There will be no barking—do you understand that? No barking whatever."

"Certainly not," wagged Plutus....

Prosper might have done worse—for it was the low uneasy growl of the terrier which at midnight recalled him from the brink of sleep.

"What is it, Plutus?"

The dog was staring through the chink left at the tent opening for ventilation.

Prosper left his blankets and looked out listening. There was no wind, and the whole world was uncannily still.

A reddish moon hung low over Kern Castle. Prosper watched Plutus who, with a furiously twitching nose, and stiffly erected shoulder bristles was sniffing incessantly and glaring in the direction of the sunk garden of Kern.

"Ah, so thus it is, my son, is it?" said Prosper tensely, and took from under his pillow a thing which glittered bluely in a stray moon-beam—an automatic pistol.

He passed out into the chequered maze of moonlight and shadow that enmeshed the wilderness in which he had made his track to the garden that afternoon.

Plutus was left behind, duly warned to silence.

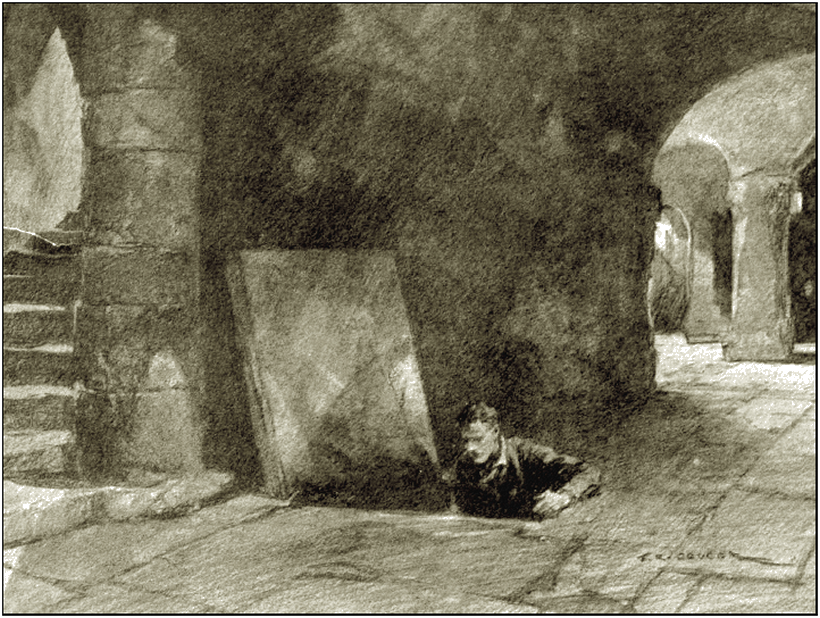

Very cautiously and slowly Prosper made his way to the sunk garden.

Plutus was everything but a liar, and Prosper knew that. And the small dog was extraordinarily experienced. It was no such light matter as a prowling fox, a stealing rabbit, or a gliding weasel which would so excite Plutus at midnight following a brisk day.

There was a more formidable thing abroad to-night than any common or customary prowler.

Prosper had reason to congratulate himself on the care with which he had broken his trail that afternoon. Had he not done so he could never have made his way direct to it in the dull moonlight. Even as it was he could not avoid the thorns and brambles which gripped him as though with invisible hooked ghostly hands, holding him back at every few yards. There, too, were owls, floating on down-muffled, utterly silent wings, who screamed discordantly overhead—long the nocturnal owners of this desolate spot; and once a lithe thing, probably a grass-snake, squirmed under his foot as he walked thigh-deep in dense shadow.

It was eerie there and the odour of the vegetation which he crushed underfoot was peculiarly pronounced—acrid, rank and poisonous.

But presently he moved clear of that belt of woodland and came, light footed as a cat, to the arched entrance to the sunk garden. For a few cautious moments he paused there, looking in, reconnoitring. He was prepared to take no chances, to run no unnecessary risks. Under its towering black walls of yew the sunk garden lay, soundless, serene, tranquil in the moonlight, and the bulk of the pyramid of lead, looming squat and heavy in the centre of the garden, seemed merely unattractive rather than dangerous in the sense that any one need hesitate to approach it.

But two people had been found dead in its shadow already without any signs of what had caused their deaths—and Prosper Fair was not desirous of becoming the third victim for lack of a little caution.

His eyes grew more used to the curious chequered light in the garden, as he stood in the archway watching and listening. He saw nothing, heard nothing. Had not the sharp-sensed little Plutus distinctly given it as his opinion that there was something queer—unusual—taking place in the direction of the garden, Prosper, after his inspection, would unhesitatingly have declared that the place was deserted.

He moved quietly out from his archway, and keeping well in the black shadow of the yew hedge he went silently along the flagged walk towards the pyramid.

The theory of the schoolmaster that it was the south side of the pyramid which was the most dangerous recurred to his taut mind, and he approached it from the north side.

Once in its shadow he waited again to listen.

But the jarring, rattling cry of the owl from over the belt of wilderness was all he heard, and that was absorbed by the night instantly, as blotting paper absorbs a spot of ink.

Then Prosper walked along the west face of the pyramid and, checking at the corner, peered round to the fatal south side.

Even as he looked some keen uncanny intuition warned him what he would find. He had felt for the past half hour that, moving silent, malign, grim and terrible, the spirit of murder which haunted this deserted place was abroad to-night.

Now he knew.

Lying at the base of the pyramid of lead was the body of a man.

Prosper was by his side in an instant. Carefully shielding the light with both hands cupped round the bulb, he flashed a small pocket torch into the still face.

It was that of the Iron-Grey Man.

He was quite dead, though his body was still warm. A quarter of an hour before he must have been living.

Prosper switched off his torch and stood up, thinking swiftly. It was impossible that the killer could have got far away—if indeed he had left the garden at all. Even now he might still be lurking in the myriad shadows, watching, listening, planning to add yet another to his already terrifying list of victims.

Prosper drew in a long deep breath and with a sheer effort of will-power caught up and re-strung his relaxing nerves.

Then even as he slipped his pistol free and, gripping it in his right hand, began to back round out of the perilous zone under the south face of the pyramid, a sharp, ringing report hammered the silence to shreds.

Between the garden and the castle some one had fired a revolver.

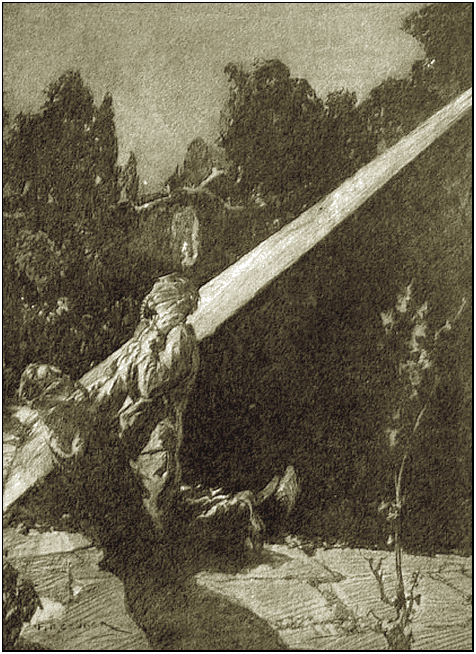

Prosper did not hesitate. He ran silently towards the exit nearest the sound, passed through and found himself in the darkness of a densely overgrown yew alley. On the mossy walk his rubber soles were noiseless.

A few yards further on he stopped short—like a pointer.

On the other side of the hedge a man was crouching. Prosper had caught the rustle of leaves and twigs as this one moved.

But Prosper was not the only one who had heard that movement, for as he paused, listening, swift feet thudded twice on the turf at the other side of the hedge, like those of a man rushing, striding swiftly, and a low tense voice in the darkness.

"Now, you!"

It was the voice of the man from Scotland Yard—and it was instantly evident to Prosper that the detective and another man were engaged in a hand-to-hand struggle beyond the hedge. He could hear the short, strained pantings, the scuffle and thud of their feet.

Then came swiftly the peculiar, flat, wholly unmistakable sound of the impact of metal or hard wood against thinly covered bone, and a low groan.

"Now, will you take it quietly—eh? eh?—keep still—"

There was a tiny ominous clink of steel, and Prosper heard the detective say in a voice of complete triumph and satisfaction:

"That will do you, I think. Get up. You've paid your last visit to this place—killed your last victim here."

"Killed a victim! Why, you fool, I'm hunting for the man who killed Larry Calhoun here. You call yourself a detective! Why, you fool, I'm Fred Oxton—I was partner with Calhoun. Everybody in the village knows me. You've spoiled everything. Why, he was about to-night—the murderer—he was about, I tell you—I thought it was him I shot at—"

"That'll do, now. You can tell me all that tomorrow," snapped the inspector. "I'll take care of you till then."

"Do what you like—what the devil d'you think I care? You've ruined the best chance we'll ever have of getting the right man. You'll see. He's about. He's on the job to-night. Mark my words—you'll hear of him before morning. I tell you, I wouldn't swear that he's not close by now—in the dark—listening.... Come on, now, I'll make you an offer. Let's go to the pyramid and look—you can keep these handcuffs on me all the time—"

But the detective was satisfied.

"No, no—I'm not looking any farther for my man to-night." He chuckled rather grimly. "One murderer a night will do for me. Come on."

Prosper heard them move away, blundering through the shadows, the man in handcuffs cursing furiously.

For a moment he hesitated. He had caught in the voice of the man Oxton what the inspector seemed to have missed—a certain ring of truth.

Then he turned and made his way with infinite care back to the pyramid of lead.

An icy thrill of surprise touched his veins as he rounded the pyramid.

The body of the Iron-Grey Man had disappeared.

Fred Oxton was—must be—right. The killer was abroad that night—and close at hand.

For a moment Prosper was undecided, listening tensely. He was appallingly at a disadvantage—and was well aware of it. It was extremely likely that the killer crouched in dark ambush quite close—almost at arm's length—watching him, ready to deal with him with the same mysterious but deadly effective weapon or means he had already employed against three victims.

But Prosper, like many another airy, irresponsible-seeming, modern young gentlemen, had nerves which difficult situations only strung to the tautness of steel wires.

He remained where he was and looked about him in a long deliberate scrutiny, straining his eyes at every nearby shadow or dark patch. But none of these moved, made any sound, or seemed in any way suspicious and his stare moved round the garden—to become instantly fixed, as it touched a flight of steps at the end of the garden.

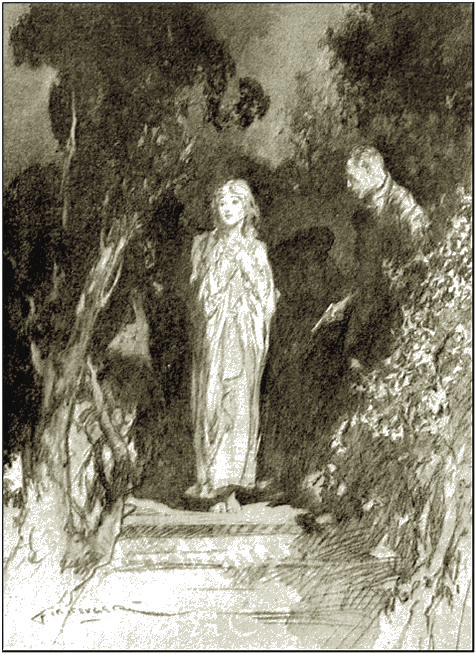

A figure was standing there—pale, silent, almost spectral in the light of the moon.

A chill hand gripped his heart for an instant at sight of this ghost-like apparition. Then he shook himself free from his momentary agitation, and moved swiftly and silently on his rubber soles towards it.

His pistol hand was raised and ready, the wrist pressing lightly against his right side. He could have fired in a fraction of a second.

But the figure made no sign of offence.

Prosper drew near.

"Who are you? What are you doing here? Be careful—I am armed," he said, quietly. The figure made no answer.

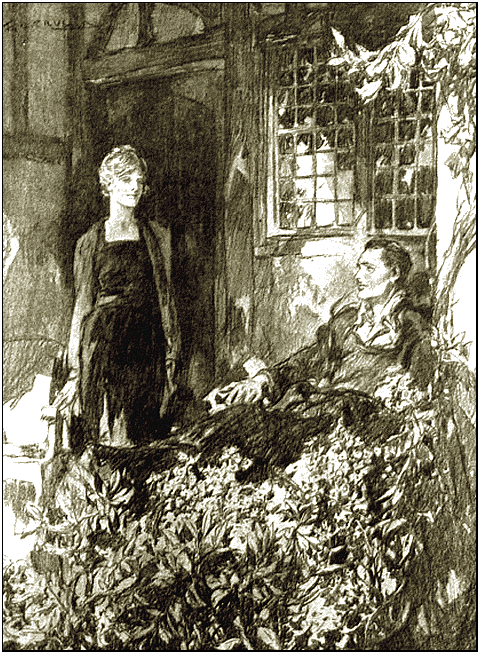

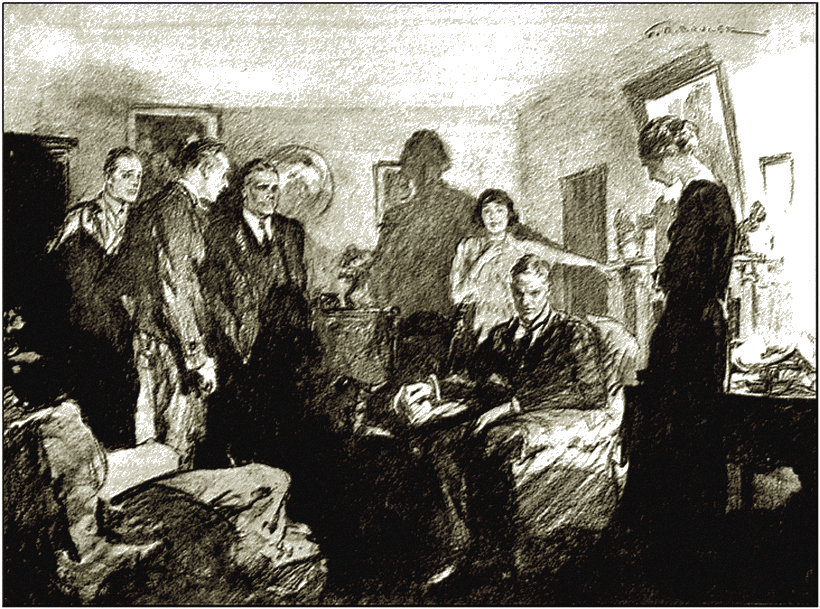

Prosper stepped closer yet and his pistol hand fell. It was Marjorie Merlehurst.

"Miss Merlehurst—"

He was within a foot of her now.

And then he caught his breath.

The girl was fast asleep. It was not from the expression on her face or her eyes, for these Prosper could see but dimly in that shadowy moonlight, that he realised this startling situation. It was because she appeared to be wearing only a light silk kimono or wrap over her nightdress. Her hair was loose—and her feet were bare. Prosper felt a little chill wave at that, for vipers lived in the crevices of the stonework of the garden—he had seen two that afternoon—sunning themselves.

Suddenly she spoke in a strange, dreamy, hesitant voice.

"He went into the dark shadows under the yews—carrying something. I saw—oh, I am sure it was he—I recognised him—it was—"

"He went into the dark shadows under the yews—carrying

something.

I saw—oh, I am sure it was he—I recognised

him—it was—"

She broke off abruptly with a little moan, very pitiful to hear. She was silent then for a moment. Prosper, watching her, was conscious of a shadow that moved behind her—a dark blur moving against the dark background. Some one there, or was it just a trick of the light?

His pistol hand swung up again, and his swift wits, strung to an uncanny keenness, pounced on the truth.

This girl, consciously or unconsciously, must have seen the man—without doubt the killer—who had taken away, for his own reasons, the body of his last victim. She knew him—had recognised him—was on the very brink of uttering his name. By some trick, some freak of the mind in her state of somnambulism, she had yet realised—or, more probably "sensed" in some profound, inexplicable way, his identity. She might say aloud his name at any moment... and Prosper fully believed that close behind her, a shadow masked by shadow, he lurked, armed and ready, listening—listening.

If she spoke a syllable of his name she would die swiftly—Prosper was sure of that. But not until she spoke it, for the killer knew that Prosper, armed and ready would avenge her instantly. It was impossible for the man to kill two people simultaneously. Prospers eyes strained over her shoulder into the shadows. Had he seen a movement, a ghost of a movement, or heard a sound, a thread of sound, he would have fired at once, and risked the shock to the startled little sleepwalker.

But the darkness that shielded the lurking death was blank and blind, as silent and still as it was perilous.

Keyed up, every muscle taut and strung to its extremity, every sense alert to the point of torment, Prosper waited, aiming into the shadows.

The girl's strange floating voice rose again, sweet and faint on the silence.

"I—recognise him—I—"

Another voice broke in—low, of a pleasant timbre, but full of anxiety—calling softly from somewhere behind the yew hedge.

"Marjorie! Marjorie!"

A pause.

Then, a little nearer.

"Marjorie! Are you there? Don't be afraid. I'm coming to be with you. Are you awake?... Marjorie!"

It was like the voice of some kind and friendly ghost calling softly out of the gloom—coming nearer.

Prosper recognised the voice at once as that of the man he had seen in golf clothes—Mr. Barisford, who had been secretary to Lord Kern.

Evidently the girl had been missed—and Barisford was coming in search of her. Aware of the danger of waking a somnambulist too abruptly, he was calling softly somewhere out there in the gloom as he approached the girl's favourite haunt in the sunk garden.

But Prosper did not take his eyes from the shadows.

There was no danger from Barisford—what of danger came would come from the shadows....

"Marjorie! Marjorie.... Can you hear me?"

At last the pleasant voice penetrated to her tranced mind.

Prosper heard her sigh deeply—the sound of one at the very point of waking—and a second later, her confused little cry:

"Oh-h! Where...."

"It is all right, Marjorie—all right," said Prosper gently but very quickly. "Nothing to be afraid of—nothing at all."

He stepped aside and the ray of his electric torch darted on to and dispersed the shadows.

The black muzzle of the pistol in his right hand seemed like a dark, sinister, basilisk eye following intently the white rod of light from the torch.

SO convinced was Prosper that the deep shadow behind Marjorie Merlehurst harboured or ambushed some imminent and formidable danger that it was with a sense of shock he realised that nothing—neither man nor beast—was there. Only the dark mass of yew like a low cliff of greenish-black rock.

A few seconds later, indeed, somebody appeared, but this was one whose voice Prosper had recognised, and whose arrival he was unfeignedly glad to see—Raymond Barisford. He came swiftly through the archway in the hedge, his keen, handsome face white and anxious and the girl went to him with a low cry of relief. Her first waking stare at Prosper had been that of one dazed, but now the soft shackles of sleep had fallen from her mind.

"Oh, I woke suddenly and I found myself in the dark... until that ray leaped out like a great eye... and some one was staring—"

She was looking at Prosper, one hand trembling on Barisford's sleeve.

"Yes, yes—but it's all right now, Marjorie—all right," Barisford soothed her.

"I have been walking in my sleep again—I was thinking of the sunk garden when I went to bed. I seemed to dream ... a dark dream with shadowy men moving through it—like men moving through smoke—vapour—"

She was silent suddenly, staring blankly ahead, her pretty brows drawn together like those of one trying to recall a dim memory.

"Men—moving dim in the fogs—" she murmured.

"Never mind the men, the dream, now, Marjorie—it's all right. I am going to take you home safe and sound again—"

He slipped an arm round the slender figure and stared intently at Prosper.

"Who are you?" he demanded. "What are you doing here?" His voice was sharp with suspicion. "You do not belong to this—district."

Prosper smiled into the glare of the other's electric torch.

"I? Oh, a nobody, a wandering artist—a vagabond painter—a sleeper-out—a walking tourist. My name is Prosper Fair and I have a camp in the woods close by. I wandered here to paint the famous sunk garden of Kern and its pyramid—and I came out to see it in the moonlight. Call on me to-morrow, and let me prove to you that I am—perfectly respectable."

It was impossible to misinterpret the cool, cultivated voice. Barisford's tone was moderated as he spoke again.

"A strange place to visit in the moonlight, Mr. Fair," he said. "And—why did you frighten the lady?"

Prosper's voice was tranquil as he answered.

"I should not easily forgive myself if in any circumstances I frightened a lady. I am sure she will let me detain her just long enough to explain that as I moved from the pyramid to investigate more closely the little apparition which proved to be herself, I believed, no, I am quite sure, I saw someone—something—move in the darkness behind her. Already I have learned enough to know that it is not good for one, awake or asleep, man or woman, to turn one's back upon moving shadows in this garden—at this hour of the night. So I conceived it wise to risk the danger of waking Miss Marjorie abruptly, in order to satisfy myself about what might have been a greater danger."

The girl glanced over her shoulder.

"Yes, yes—that is true—and thank you, Mr. Fair," she said quickly.

Barisford nodded slowly, studying Prosper.

"There was nothing?"

"Nothing at all. I must have been mistaken," said Prosper gravely.

He flashed his ray on Barisford's heavy golf shoes, then stooped and swiftly took off his own light canvas gym shoes.

"These are lighter than golf shoes, Miss Marjorie. Won't you wear them home as a sign of forgiveness?"

The girl had wholly recovered herself now.