RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

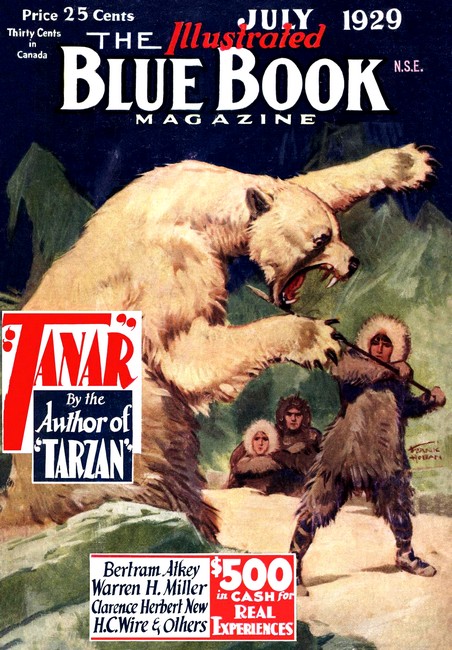

The Blue Book Magazine, July 1929, with "Hercules in Hell"

There was nothing much the matter with Herc.

Wherein the private life and public exploits of a great hero are

gayly recorded by the author of the Easy Street Experts stories.

IF one is to judge by the writings about Hercules one can hardly fail to arrive at the conclusion that this popular hero was a young man of practically no character and of pronouncedly dissipated habits. It is the intention of the present writer to prove that these historians were in error.

The Atkeys are descended in a more or less direct line from the great Greek hero, and thanks to a recent discovery, Bertram of the clan is able to throw a good deal of new light upon the life and labors of Hercules.

Some years ago Bertram's great-aunt, when making her will, remarked with a tolerant smile: "It is quite useless to leave poor Bertram any money, as he is a literary person—the only one, thank goodness, in the family—and I understand that literary people have no idea of the value of money. But he must not be forgotten. Let me see; he is fond of reading, is he not? Very well, then. Let him be put down in my will for that great chest full of old volumes, in the attic."

For some time the chest of ancient, moldy, moth-eaten books reposed unopened in the writer's chambers, and it was only when, entirely running out of coal one bitter winter's evening (says Mr. Atkey), he opened the chest in search of a little fuel, that he discovered among the volumes a very old book, written in ancient Greek, which a moment's study showed him was nothing more nor less than a close account of the famous labors of Hercules, and which must have been written either by Hercules himself or some close relative.

Spellbound, Bertram flashed through the faded parchment pages. And in the transcription from them which follows, he is able to straighten out the whole affair.

There was nothing much the matter with Herc. He was, of course, a little thoughtless and rather apt to leap before he looked; he was inclined to be extravagant; he was susceptible to feminine charm; and it is not to be denied that he was a little quick-tempered. But these are faults which are characteristic of youth of all nations and all ages. On the other hand Herc was bold and high-spirited; he was an out-and-out sportsman; he was no slacker; he kept himself fit; and he was generous to a fault. So let us not fall into the mistake of judging him by what Homer says about him. Herc was a regular fellow. Homer was a—well, a poet.

The facts in the case of Hercules are as follows: His godfather, a very influential party named Zeus, apparently being under some obligation, of which no record is left, to the father of His Majesty, King Eurystheus of Mycenae, entered into a contract that the boy Hercules when he grew up should enter Eurystheus' service for a period of twelve years.

There appears to have been no legal reason why, when he grew up, the lad should have troubled himself about the matter. But Herc was straight. He went of his own free will to King Eurystheus and placed himself at the King's disposal. Hardly the act of a crook, that! He became the best of friends with Eurystheus, and the following stories give a fairly exact account of the various little services which Hercules rendered the King. In conclusion of this note, the present writer would say that if there is one statement in these stories which is not true, let Homer disprove it. But he won't! And why? Because he can't!

—Bertram Atkey

IT was early summer in Greece when young Hercules, in accordance with his godfather's command, presented himself before the Oracle Madame Pythia and thrust a palm the size of a soup-plate before her. After a brief survey of the big, badly calloused member, she pronounced:

"What do I see in this hand? I see a busy future and a deplorable past. The owner of this hand is a violent man when roused. He is fond of the ladies. He should beware of a dark lady whose name begins with a D. He will go upon a journey very shortly. I see in this hand a signal from the Fates—an order—that the owner hereof must journey to the home of Eurystheus, King of Mycenae, and offer his services to that gentleman in accordance with a contract made years ago when the owner of this hand was a child. That contract was to the effect that for a space of twelve years Alcmene's son should work for King Eurystheus. The contract is binding and completely in order."

She dropped the great hand and glided away into the temple.

SOME days after his consultation with the oracle, Hercules

arrived at Tiryns, and engaging a chariot, drove out to call upon

King Eurystheus, who was staying at his country-place some miles

outside the town.

Arrived at the palace, Hercules tossed the charioteer a coin, and telling him he need not wait, was about to enter the house when he was called back by the charioteer, who with an expression of extraordinary bitterness on his face was staring at the coin which lay in his open palm and muttering to himself.

"Here, what d'you think this is?" he said insolently as Hercules returned.

"Your fare, laddie—what do you think it is—a medal?" replied Hercules, good-humoredly.

"It aint right—it aint enough," insisted the charioteer. "Lumme, what's it coming to?" he continued sourly. "Toffs come here and expect you to give 'em free rides into the country—"

Hercules hitched his club into a more convenient position.

"That's your legal fare—and a trifle over," he said, quietly. "So take it and,"—his unfortunate temper suddenly flared up,—"and shut your unshaven jaw! You've got vine leaves in your hair!"

The charioteer flushed darkly. He did not appear to be very good-tempered himself, and undoubtedly he had, as Hercules suggested, been gazing upon the wine when it was red.

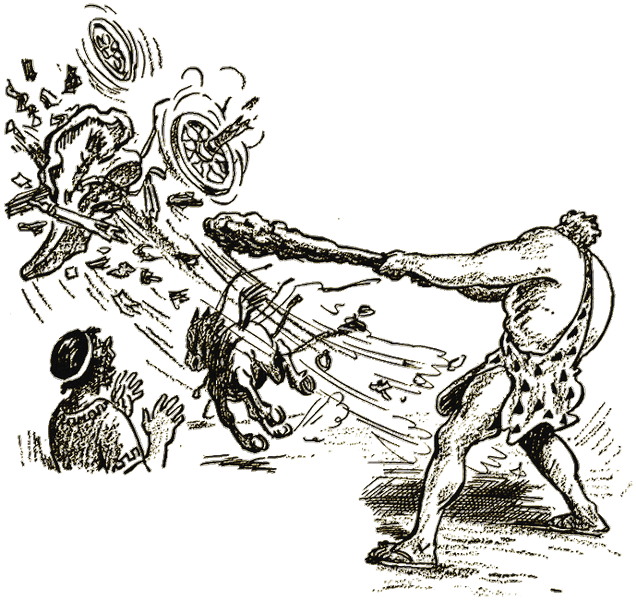

"Who? Me? Me got the vine leaves in my—hic—hair? You'll have to prove that! I don't let no bilker tick me off—not if he's the size of a house!" He began to get off, but Hercules' patience was already exhausted. He swung in a curious underhand shot with his club at the chariot. There did not appear to be much force in the quick, easy-actioned stroke, but it was beautifully timed; it wrecked that chariot as few chariots have been wrecked before or since.

Hercules' patience was exhausted... The quick strokes

wrecked that chariot as few chariots have been wrecked!

The dour charioteer, suddenly sobered, gasped, gazed at Hercules a moment, and then turning abruptly, tore away down the drive after his horse, which had promptly bolted.

Hercules stared after them for a moment, and then with a smile bade a gaping chamberlain announce him.

KING EURYSTHEUS was in his library alone,—when at his

country-place the King lived the life of a simple country

gentleman,—and received him with complete cordiality.

"Well, my boy, so you have come to carry out that little arrangement made by Zeus so long ago?" he said. He was a mild, rather subdued-looking individual.

"Sit down, my boy, sit down," he said, cordially. "I must say that this is a very pleasant surprise—very pleasant indeed. It isn't every young fellow who would cheerfully come along to give twelve years' labor to another man in this way, and I appreciate it. It's honest—and honesty is getting rarer in Greece every day. But mind you, Hercules, it's no more than I expected of you. I've heard a good deal about you, one way and another, and I must say that I expected you. I'm sorry the Queen isn't at home—she has been looking forward to meeting you; but there will be plenty of opportunities of making her acquaintance later on."

He paused a moment, raking absently at his beard.

Presently, with a rather nervous laugh, he spoke again.

"Now, I don't want you to think that I'm rushing you away to your work in a hurry," he said, "but the fact is you've come at a very opportune moment, and there happens to be a very great favor which you can do me almost at once. It is the Queen's birthday next month, and she's set her heart upon a new set of skins. There seems to be a craze this year for lion-skin, and of course the wife, being the Queen, wants a set of the very best. In fact—between ourselves—she's simply crazy on getting the skin of that lion down in the Nemean valley. You've heard of it, I dare say?"

Hercules signified that he had.

"Well, foolishly enough, I've promised her that she should have it—you know how it is: they wheedle these promises out of you before you know where you are. I sent a party of hunters after this lion last month, but they didn't do any good. Got devoured, most of 'em, in fact. And it's put me in rather an awkward position. If you could do the business for me you would be doing me a very great service and you would start right with her. As you're going to be more or less living with us for the next twelve years it would be the tactful thing to do, too. Mind you, Hercules my boy, I haven't got a word to say against her. She's been a good wife to me—one of the best; but—er—well, you see how it is. Tact, my boy—tact—a little tact goes a very long way. To go and kill this lion and bring her back the skin would be a very tactful start."

He looked anxiously at Hercules, who smiled.

"Oh, if that's all," he said buoyantly, "don't worry."

Eurystheus' face brightened up, then clouded over.

"It's not an easy matter, I tell you frankly. This lion is not merely a man-eater—it is said to be about the biggest brute ever known, and as intelligent as a human being. Don't underrate the beast. Are you pretty skillful with your weapons?"

"Oh, not too bad," said Hercules modestly. "I've done a bit of wrestling with Autolycus—he held the heavyweight championship of Parnassus for ten years, and taught me quite a decent bit. I learned my archery from Eurytus, and my heavy-armor fighting from Castor. But my club work I taught myself. You can't beat a good club for infighting. Don't worry about me."

Eurystheus nodded.

"Well, my boy, you know best. But be careful. And that settles that. Will you have anything?"

Hercules rose.

"No, thanks. I think I'll get that skin as soon as possible, if you don't mind. I'm rather keen on starting well with Her Majesty," he explained.

Nodding approval, Eurystheus rose also. "Very well, my boy." He shook hands. "Have you everything you want—money?"

"Yes, thanks—quite all right," replied Hercules gayly. "Expect me back before long—with the skin, what? Good-bye."

TWO mornings later Hercules might have been seen standing by a cave at the entrance to the Nemean valley, engaged, not in searching for the lion, but in exchanging badinage with an attractive peasant maid.

"Yes, my child," he was saying, as he passed an amorous arm round her lissome form, "yes, my child, I purpose camping in or about this valley until I run across this lion everybody seems to be talking about, what? And naturally I shall want some one to bring me milk and eggs from the nearest farm—which appears to be your papa's farm, little one. Why shouldn't it be you, child?"

He patted her pretty cheek.

"Do you like me, little one?" he inquired.

"Very much," she said, softly.

"And I like you," said Hercules. "What is your name, my little pigeon?"

"Those that like me call me Dodo!" she whispered shyly.

"That," said Hercules firmly, "is my favorite name. Well, Dodo, darling, I—"

He broke off abruptly as a noise resembling distant thunder rumbled somewhere far up the valley. Dodo started. "The lion!" she said. "I want to go home, please," she added, sensibly. Hercules looked at her reproachfully.

"Oh, I say, Dodo, don't say that, what?" he exclaimed. "Surely you aren't afraid of a mere moth-eaten lion when you have your Hercules here to take care of you!"

But apparently Dodo was. She slipped out of the lion-hunter's grasp with a deftness which to a less unsuspecting man might have hinted at a certain amount of practice.

"I've stayed too long already," she said. "Mother will be wondering. When are you going to begin hunting the lion?"

"Oh, after lunch, perhaps. Any time," he said carelessly. "The first thing I must do is to find a decent cave to sleep in, what? Sort of headquarters. Do you know of a good cave anywhere about here, Dodo?"

Dodo appeared to reflect.

"Yes," she said at last, "the very place. It's a lovely cave—we used to have picnics in it before the lion came. It is about a mile up the valley just past a clump of cypress trees on the right. It is rather dark right at the back, but it has a sandy floor and it's awfully comfortable."

"The very place," said Hercules. "Will you bring the eggs and milk there, dear little Dodo, or are you afraid of the lion?"

She glanced at him under her long lashes.

"I will bring them in the moonlight," she said. "The lion never hunts in the moonlight. Will that do?"

"Will it do?" echoed Hercules. "I should think it will do, darling. It's most frightfully sporting of you, Dodo. And you really-truly will come at moonlight for a little chat with your Herky-boy?"

"Yes," said Dodo, and blowing him a kiss, tripped away.

HE watched her until she turned a rocky corner. Then, with a

sigh, he shouldered his kit-bag, picked up his club and headed up

the Nemean valley.

"What a positive little peach!" he said to himself as he went. "The sweetest little thing that ever happened! And her darling little name is Dodo! Dodo! And how fresh and pretty and healthy! How different from our set. What a jaded lot they seem beside Dodo. And how ingenuous and innocent!"

Thus communing with himself, he proceeded at a leisurely pace up the valley. He would perhaps have somewhat modified his opinion of Dodo's ingenuous and innocent nature had he been able to see her then. No sooner had she turned the rocky corner which hid her from Hercules' sight than she came face to face with another individual—a tall young man, tastefully arrayed in a leopard-skin and a bangle. He was not by any means the physical equal of Hercules, being at least twenty-five per cent smaller, but he was not at all unhandsome (for those days) though he had a rather shifty eye, and a hardish jaw.

He took Dodo in his arms and kissed her.

"Well, kiddy, and what did the great stiff have to say for himself?" he asked, jerking his thumb up the valley.

"He's going to hunt the lion for the sake of its skin," said Dodo. "He's going to camp in the valley till he kills it!"

The gentleman in the leopard-skin frowned.

"Oh, is he? Did you explain to him that I'm out to get that lion alive, that I've come here specially from Rome, and have been here for the last month, kid?" he inquired.

"Yes, Max, dear!" said Dodo, using an affectionate diminutive of Maximus, which was the name of the young Roman who was her lover.

"What did he say, honey?"

"He was rather gentlemanly about it," said the little traitress, "but very firm. He said he was 'awf'ly sorry and all that,' but he'd practically promised the skin of the lion to a lady, and that, being a Greek gentleman, he simply had to keep his word. He said—don't be angry, Max, darling—he said he couldn't possibly allow any dago circus-proprietor to have his lion. It wasn't his way, he said. And he looked fearfully determined when he said it!"

Max ground his teeth.

"Dago circus-proprietor, eh, kid? He called me that, did he—me, the biggest wild-beast importer in Rome! The hulking Greek gink! They look down on Rome, these guys over here do. I know it—but Rome's a growing little burg, believe me, kiddo, and it won't be long before we get these measly Greeks guessing! Dago circus-proprietor, hey? I'll tell you what it is, hon, that great muscle-bound Olympian gorilla is scheduled for some rough work if he don't beat it out of this locality."

Dodo nestled close to the exasperated importer of wild animals, and soothingly patted his cheek.

"I don't think I should worry, Max darling," she said. "I think perhaps I have been able to help you. Of course I'm only a weak girl, I know, but every little helps."

"Why, kid, what have you done?" demanded Max, holding her at arm's length, staring hard at her.

"Well, he asked me if I knew of a good cave to take up his quarters in," she said softly.

"Yes, hon—go on!"

"And I told him of a beauty—one about a mile up the valley just past three cypress trees on the right. And he's going there!"

A look of admiration dawned slowly on the face of the hard-looking Max.

"Why, Dodo—that cave is the favorite den of the Nemean lion!" he exclaimed.

"Yes, Max," said Dodo meekly.

"Gee!" shouted Max, and pulling her to him, embraced her with extreme liberality. "Why—why, the great gink will walk bing into the lion's jaws!"

"Yes, Max!"

"Oh, you Dodo! You little genius!"

He kissed her enthusiastically.

"Why, within the next hour he'll be eaten! We'll give him time, and then we'll quietly scout up the valley and see what's happened," proposed Max. Dodo agreed.

IN the meantime, Hercules, heavily laden with his weapons,

his kit-bag, his cooking utensils and luggage generally, was

innocently approaching the cave, his mind so occupied with the

delightful Dodo that he had temporarily clean forgotten the lion.

He went dreamily on, dragging his club at the trail, until he saw

the cypress trees and just beyond them the dark mouth of a large

cave.

"Ah, that's the place that dear little thing meant," he murmured. "Good! Not at all a bad little cave, either."

He turned toward it, and humming a snatch of the latest song, entered. A few feet inside it curved rather abruptly to the left, and Hercules walking round the turn nearly fell over a sleeping lion which, in the subdued light, seemed as big as a rhinoceros.

"Great Zeus!" he gasped, and as the big beast scrambled violently to its feet, with a horrible and blood-curdling snarl, Hercules dropped his luggage and shot out of the cave with a rapidity that was remarkable in one so big and burly. But the Nemean lion was what Max would probably have described as "no slouch." The big brute was not more than a few yards behind Hercules as he tore frantically toward the nearest tree, and brave man though Hercules undeniably was, the growls of the man-eater made his blood run so cold that he would not have perspired had he run ten miles at the same pace.

He was not afraid of the lion. He feared the big beast no more than a fly, for he was one of those men who have not an atom of fear in his body. In fact, he did not know what fear was. He would have faced half a dozen such lions, any day—provided he was ready.

The reason he was going to climb a tree was not because he was afraid of a Nemean lion or any other kind of a lion, but because he wished to find a place where he could think out a plan of action without being disturbed. He would have turned on the brute like a flash, as he explained later on to Eurystheus, but he—well, he wasn't ready.

He feared the big beast no more than a fly—but

he wished to find a place where he could think disturbed.

He reached the tree first, with perhaps four yards to spare, and he went up it like a squirrel. The claws of the lion tore a shower of chips from the bark about an inch below his foot as he jerked it up into safety.

He worked his way out upon a bough, and sitting comfortably in a fork, surveyed the raging man-eater below with complete coolness.

"Well, old top," he said cheerfully, "you made a close finish of that little sprint, what?"

"Oo-wough!" went the lion, leaping for him, but springing at least six feet short.

"Oh, don't get stuffy about it," said Hercules. "You've had your chance—thanks to that little dev—that little vixen Dodo, and you've missed it. It's my turn next, old son."

For some minutes the two stared at each other; and then the lion, apparently realizing that it was wasting its time, strode away, growling sulkily. It did not return to the cave, but passed it and turned into a little ravine which opened into the valley some ten yards past the cave.

Hercules watched the beast go and then devoted a few minutes to reflection.

"Now, let me see—if I were a lion with a reputation for great intelligence, what should I do? That's the way to work these things out. Well, it's easy. I should hide round the corner of that ravine until my dinner climbed down. And that's what the brute is doing, if I am any judge. I'll take a bit of a rest, I think."

And having come to this wise conclusion, he settled back to doze.

IT was beautifully warm and sunny in the valley, and save for

the lazy chirping of birds, it was drowsily quiet. A rabbit of

youthful and inexperienced appearance presently issued forth from

its hole and played about a little. Presently it hopped into the

ravine. It did not return.

Hercules smiled slightly and shouted. But the rabbit did not come racing back to its hole. Evidently something had detained it.

Hercules nodded and settled back again.

Presently a stray tortoise-shell cat came strolling up the valley, apparently looking for either a rabbit or a good place in which to bask in the sun. This creature also turned into the ravine, Hercules watching it alertly.

He saw an extraordinary thing occur.

The cat reached the corner of the rock round which the rabbit had wandered, and then suddenly went straight up into the air, with a frantic yell of surprise. It landed again a good ten feet farther back from the ravine, and then only for an infinitesimal fraction of a second. It went bounding away down the valley as though pursued by a pack of starving wolves.

Hercules smiled again. He had seen the vicious sweep of a great hooked paw as it flashed like lightning over the spot the cat had just left when she first went up.

"What a brainy old beast it is!" he mused,

Then, chancing to look down the valley, he saw approaching slowly and cautiously two figures—one of them Dodo!

He started a little, frowning. This complicated things.

"I can't allow that pretty little thing to walk into danger like this," he said to himself. "True, she allowed me to—but after all women nowadays have to fight with what weapons they can get. We're not really civilized yet. Later on, in the twentieth century or thereabouts, it will be different, no doubt. Women won't send men to the dogs—or lions—in those days. I must warn her and her friend in the leopard-skin."

He stood up and measured the distance from the tree to the cave in which his weapons lay.

"Might just do it," he said. "But it will be a close thing. I don't care about it. I may, in fact, get a fairly thorough mauling. But there's nothing else to do! If I shout to warn them it will probably bring the beast out, and he'd catch them before they'd gone a hundred yards!"

He took off his wallet. It was a big wallet, as wallets go, being about the size of a satchel, and judging the distance carefully, threw it about forty yards up the ravine. He heard it fall with a soft thud.

"If the brute goes to investigate that it's odds on me!" he muttered, waited ten seconds, then dropped to the ground and raced for the cave.

He heard a grunting "Whoof-whoof!" from the ravine as he went, and out of the tail of his eye had a glimpse of huge, dun-colored body all eyes and mane and teeth charging out of the ravine. But he won. He had just time to snatch up his club and dart back into the open, when the Nemean lion, the terror of the district, was on him.

But this time Hercules was ready. He met the man-eater with a full, butt-ended shot that connected with its frontispiece like a sledge-hammer on an anvil. It made the club, tough hickory wood though it was, groan. But it made the lion groan louder.

"Come on, then, you Nemean burlesque!" shouted Hercules. "You a man-eater! How's that?" He slid in a lateral clip to the animal's ear with the knotty side of the club, which rolled it over like a rabbit.

But it was full of fight and as strong as an elephant. It came on for Hercules' throat like a wildcat. Hercules dodged neatly and steered one to its slats as it swung past, a blow that made it boom like a drum. Hercules began to shout his war-cry—a habit of his when excited.

"I learned my wrestling from Autolycus, heavy champion of Parnassus!" He deflected another charge by the maddened lion with a sparkling whang to the jaw.

"And Eurytus taught me my archery!" Here the crispest of side-swings closed one of the man-eater's eyes.

"What I know about armor fighting I picked up from Castor—"

Here he missed a vicious drive and lost a good two pounds of flesh from his thigh to a steel-hooked claw as he whirled clear of the charge.

"But my club-work is my own idea—ah!" he roared, furious with pain, and deposited a pile-driver on the lion's intellect-plate which made the very ground shake and must have jarred the beast clear back to the tassel on its tail.

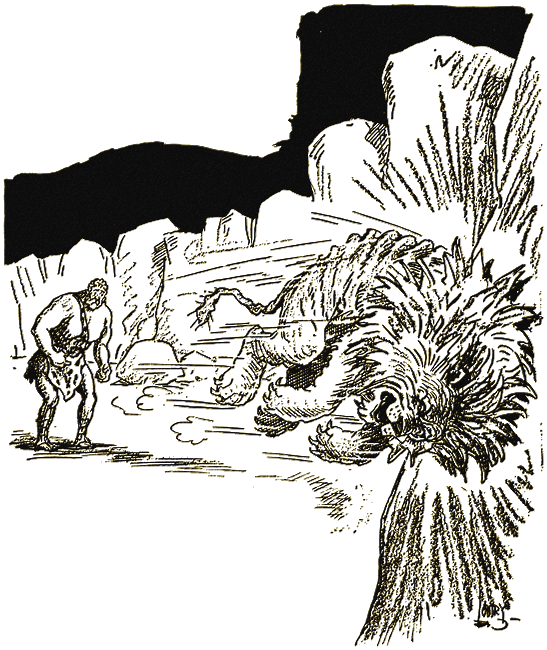

The animal went down as though struck by lightning, but it was up again before Hercules could repeat the frontal slam. ... Some hundred yards away Max and Dodo stared in fascinated wonder.

The lion doubled itself up and leaped again. But it was tiring slightly, and Hercules, seeing his chance, stepped in with his left foot and handed out a dazzling shot which would have sent a lighter lion clean to the mat.

"Club-work!" roared Hercules. "Some club-work, too! What?"

Wearily the man-eater rose again, and again precipitated itself at its enemy. But its chance—if indeed it had ever had one—was gone. For Hercules was roused.

With a yell he dropped the club, and ignoring the claws, met the lion as it came. He grabbed its right foreleg, and twisting sharply so that his right shoulder came well under the man-eater's right chest, lurched forward with all his weight and strength.

Even Max, telling some friends about it later on, one morning in Rome, said that, although he, personally, disliked Hercules immensely, he could honestly say that he had never seen a better flying mare executed by any wrestler before or since.

For thirty-three clear yards the Nemean lion traveled through the air like a projectile, and even then was only stopped by a large granite boulder, weighing some fifty tons, which obstructed its flight. The big beast arrived with such a fearful impact that it split the boulder, practically wrecking it, and as Hercules afterward discovered, breaking its own neck in six places and in six different positions.

The lion traveled through the air like a projectile,

and was only stopped by a granite boulder.

IT was at this moment that Max threw off his fascination. He

turned to Dodo and jerked a thumb over-shoulder at Hercules.

"Kid!" he said solemnly, "he wins it! I'm no coward—but

what's the use, anyway? I'm not a bad little old workman on the

wrestling mat myself, but gee, honey, that Greek guy's out of my

class altogether. I own it—I admit it. Do you want your

little Max to commit suicide, kid? No? Well, let's beat it while

the going's good! It's up an alley for ours, eh, Dodo?"

Dodo agreed without hesitation—and so by the time Hercules had calmed down a little and approached the lion, the couple were well out of sight and still hurrying.

Hercules wasted no time. In spite of his victory he had taken quite a dislike to the Nemean valley. He had been looking forward to a charming idyll interspersed with an occasional day's hunting. But Dodo's default had wrecked his dreams as completely as he had wrecked the lion's future.

So, having bound up his wounds, he proceeded promptly to skin the dead man-eater, roll up the great hide, and collecting the remainder of his gear, start for home.

He was in an excellent humor. True, he had one or two nasty wounds, but if ever a person was used to nasty wounds it was Hercules.

He called in at the farmhouse of Dodo's parents on the way back, but Dodo, they said, was out.

"Oh, well," said Hercules, shrugging his shoulders. "With the gentleman in the leopard-skin, I presume."

He drank a bowl of wine, and reshouldered his gear.

"You might tell Dodo I looked in to say good-bye," he said to the farmer, "—to say good-bye and to thank her for telling me of a good cave," he said sarcastically. "You might add that Hercules said that if she ever feels a longing for another picnic in that cave it will be quite all right. There's nothing left in the Nemean valley more ferocious than a stray tortoise-shell cat—and I doubt if that's feeling very ferocious after this afternoon, what? Adieu!"

And so saying, he turned away, and headed steadily for home.

IT was perhaps three weeks after Hercules had settled the affair of the Nemean lion and he was sitting one evening, after a busy day's hunting, enjoying a small tank of wine (as was the custom in those days) with the King.

They were putting in the week-end at Eurystheus' country place near Tiryns—a retreat to which the King was ever ready to flee for a few days' rest from the social whirl of the town, and it is necessary to add, from the keen and lengthy criticisms of his wife and daughters, with whom, it may be said, Hercules had made but a very moderate hit. They considered Hercules 'coarse'—for so, in comparison with the curled, perfumed and somewhat undersized exquisites of the court, he appeared to them.

But Hercules, who was no very pronounced admirer of Eurystheus' family, was bearing up under their coolness very well, and like His Majesty was glad to get away from the court whenever possible.

"They may say what they like, my boy," remarked Eurystheus, dipping his crystal pitcher into the wine tank, "but they will never convince me that this isn't the correct way to spend a week-end. What is there to do in town, after all? A banquet with a crowd of people you don't know and wouldn't like if you did know, and a lot of dancing or gambling after it. That's the Queen's idea of an evening. And what is there to do in the daytime? Nothing—absolutely nothing that one hasn't done a thousand times before. Laying foundation-stones, receiving ministers and things like that. Attending bazaars, eh? Absolutely treadmill work, Hercules. Hey, boy?"

Hercules nodded.

"You are right—as usual," he replied. "There never yet was a bazaar in Tiryns, or anywhere else, which was worth a run like we had today, what!" He too refilled his pitcher.

"Hounds went well," he continued. "Never known 'em go better. They're coming on—we're getting 'em together."

Eurystheus agreed.

"It was a rare good scent, my boy—but you're right for all that. They're a very even lot of hounds and as stanch as gladiators. I was afraid the fox was going to reach the rocks—another five hundred yards and we should have had to whip 'em off. It's a bit of bad country there. There's a kind of sharp-edged shale stuff very plentiful there, and it's lamed me many a good hound." He emptied his pitcher thoughtfully.

"I thought old Pegasus seemed to be going well with you today," he said.

Hercules' eyes brightened.

"He was. That's a rare good horse, Eurystheus, an uncommon good horse. I used to think that he wasn't quite up to my weight, but he is. I don't mind owning that—"

But whatever Hercules was willing to own did not immediately appear, for at that moment a page entered with a pink envelope on a salver—an express letter.

"This has just arrived by special runner from Tiryns, Your Majesty," said the boy.

Eurystheus took it, eyeing it uneasily—the more so as he observed that it was addressed in the handwriting of the Queen's secretary.

"What's wrong now?" he mumbled, as he dismissed the page, and opening the envelope hastily, read the letter. Then he handed it over to Hercules.

"Damned nonsense!" muttered Eurystheus under his breath. "What on earth does any sensible woman want with a crawling little insect of a pet dog? If it were a decent setter or retriever or a good little terrier, I could understand it—but these fancy, curly-haired freaks raise my very gorge! What do you think, Hercules?" He clapped his hands as he spoke, summoning the page.

"Send in the kennel-man, boy," he ordered.

Hercules looked up from the letter.

"I'm afraid Her Majesty is not going to be satisfied with an ordinary dog," he said. "It will have to be something rather special." He began to read aloud from the letter:

"The craze for pet dogs is extraordinary, and as a matter of policy I have ordered a dog-show to be held in a fortnight. I am determined that it shall be the best and biggest ever yet held in Greece, and I have decided to exhibit a dog myself. Kindly procure one for me. Please understand that this is an important matter, and that I am not to be fobbed off with a decrepit fox-hound, cast out of your pack—as your eldest daughter was, last year, when she was sanguine to ask you to give her a dog. Though you frequently appear to forget that you are the King of Mycenae, I will permit no one to forget that I am the Queen, and I insist upon a dog being procured which is not only worthy of exhibition by the Queen, but which, naturally, will sweep the board. I assume that you can spare a day to see to this matter!"

HERCULES finished, and for a moment the pair gazed at each

other in silence. Then, automatically, they refilled their

pitchers. Before they had time to discuss the somewhat acidulated

request of the Queen, the kennel-man entered—an ancient,

weather-beaten person of remotely horsey appearance.

"Ah, Taxi, come hither," commanded Eurystheus, who, humble though he was in the presence of his wife, was decidedly capable of keeping his end up with other men.

Taxi went thither, touching his forehead as he pulled up before the two.

"What have you got knocking about in the shape of a good dog, Taxi?" asked Eurystheus. "Not hounds, you understand— dogs!"

Taxi looked thoughtful.

"Well, Y'r Majesty, there's nothing much besides Y'r Majesty's setters, and spani'ls and retrievers," he said. "There's a sheep-dog or two down at the farms, and mebbe a few tarriers—but nothing much good, Y'r Majesty."

The King nodded, as though he had expected the answer.

"Well, they won't do," he said, half to Hercules, half to himself. "Do you happen to know of a good dog for sale anywhere, Taxi? A well-bred one, you understand—a show dog, in fact."

Again the ancient reflected. Finally he shook his head.

"No, Y'r Majesty," he replied, "not at the minute, I don't. But I'll inquire round about."

"Do, Taxi, do," said Eurystheus kindly, and dismissed him.

As the old man left the apartment Hercules suddenly laughed.

"What's the joke?" asked Eurystheus.

"Why, I've just thought of a dog that would sweep the board at that dog-show," answered Hercules. "A better dog than any dog in Tiryns, or Greece, for that matter, or anywhere else."

Eurystheus brightened. "Oh, what dog is it? Is he for sale?" he inquired.

"Cerberus!" said Hercules, laughing rather excitedly as he refilled his pitcher.

Eurystheus stared.

"Cerberus!" he gasped. He sat for a moment, taking in the idea. Then he said wistfully:

"Yes—Cerberus would sweep the board at any dog-show. But—who is going to get him for me?"

Hercules emptied his pitcher.

"I will," said he.

Eurystheus made a gesture of unbelief.

"You've had too much wine, my boy," he said. "I know you're a strong man—and we all know you've got pluck, but— well, talk sense, my boy, talk sense. You wouldn't have any more chance in Hades than a—snowball!"

Hercules rose. It was only when he stood up that one was able to get a fair idea of his immense size. He looked what he was—gigantic.

"By Zeus, Hercules, what a hefty great chap you are!" ejaculated the King.

Hercules laughed.

"Look here, Eurystheus, if I get Cerberus for the Queen will you give me that grand old weight-carrier Pegasus? I've taken a fancy to the horse—I did the moment I saw him. He's too big for you, anyway."

Eurystheus stood up. "I will," he said eagerly. "Is it a bargain?"

Hercules silently extended his hand, and they sealed the compact.

But Eurystheus added a condition.

"Of course there's no necessity to—er—steal the dog, you know, if you can get him any other way. We don't want Pluto sending his folk up here after him again—as he would. We should have half Hades about our ears before long. Try to fix up an arrangement to borrow the dog until after the show. It would make it much easier for you—and the Queen won't want him long after the show. She never really cared for dogs—cats are more in her line," he added feelingly. "When shall you start?"

Hercules pondered.

"Let's look—hounds meet at the crossroads tomorrow, don't they? Yes. Well, I'll hunt tomorrow. After all, there's just a chance it may be the last time I shall ride to hounds this side of the Styx. I'll start on Monday."

"Good man!" said Eurystheus approvingly, and they refilled their pitchers to the brim. "Well—here's to fox-huntin'," said Hercules gayly.

"And dog-stealin'," facetiously added Eurystheus.

Then they went to bed.

IT was just a week later when Hercules, who as usual had taken things comfortably, arrived in the neighborhood of Hades, the subterranean kingdom of Pluto. Although by no means so emphatically disconcerting a district as we of these days would expect to find, nevertheless it was a decidedly depressing locality and contained nothing whatever calculated to allure the wayfarer into lingering there.

The scenery for the greater part consisted of rocks—hard-looking, jagged, black rocks, very untidily distributed. Here and there pine trees stood about in a discouraged sort of way, and a clump or two of brilliantly hued toadstools endeavored, without much success, to lend a touch of color to the scene. The fauna of the place seemed to consist mainly of an occasional lizard of extremely impoverished appearance, a very shabby and depressed snake or so, and sitting upon a bough on one of the pine trees, a pair of bedraggled ravens of cynical and extraordinarily demoralized aspect. None of these took the least notice of Hercules as, perceiving a gigantic cavern-mouth in a huge wall of rock just before him, he halted and took a leisurely survey of his surroundings. He shrugged his mighty shoulders.

"Dull," he said. "Very dull, what?"

Then, without more ado, he hitched his club into a convenient position and passed through the gloomy portals of the cavern.

KEEPING, as was but natural, a sharp look-out, Hercules

pushed along down the rather abrupt slope. The way twisted and

turned quite a lot, and a number of side-roads seemed to branch

off from the main road. There were no signposts, and Hercules

stuck to the main road.

He had been walking for perhaps ten minutes when, turning a corner, he came abruptly upon a river.

"Ah, here we are," he said relievedly. "The Styx, what!"

Some forty yards to the left he saw a notice-board upon which was painted the following legend:

FERRY.

BOATS FOR HIRE.

PUNTS. BAIT SUPPLIED. GEO. CHARON, PROP.

In a ramshackle boat moored to the post of the notice-board sat an elderly, bearded person of remotely nautical appearance, fast asleep.

Hercules shook him, and he woke with a start. "Sorry, sir," he muttered. "Going over?"

"I am. You don't imagine I have come here merely to admire the scenery, do you?" said Hercules. "Put me across as quick as you can."

"Very good, sir," mumbled the old fellow. "Though you're the first gentleman I ever knew to be in such a hurry."

He rowed across in silence. The river was very calm and reasonably slow, and to Hercules it looked a likely trout-stream.

"Some pretty good trouting about here, what?" he said.

Charon nodded.

"There's plenty of fish—good fish, sir; but there's precious few anglers," he replied meaningly.

Hercules laughed.

"The people here evidently don't know when they're well off," he suggested.

"That," said Charon as he ran the boat alongside, "is what I'm always telling 'em."

Hercules got ashore, and leaving a coin and a pleasant word with the old ferry-man, headed down a long, rock-bordered chasm which evidently was intended to fulfill the functions of a carriage-drive. Presently the chasm widened suddenly into an enormous basalt-walled square, at the far side of which rose the main front of a big, but very gloomily designed palace.

"Well, here we are," he said to himself, and began to cross the square. Evidently it was night time in Hades, for the square was entirely deserted. There was not even a policeman or sentry at the gates. For a moment the intrepid Hercules was astonished, but a moment's reflection brought home to him the fact that there was little need for any such guardians here. It was highly improbable that the boldest of burglars would ever venture to exercise his nocturnal art in this locality.

Besides—as a sudden growl from the big doorway which he was approaching reminded him—there was always that champion house-dog Cerberus to be considered.

Hercules stopped a few yards from the great main door and groping in the haversack he carried drew therefrom a large piece of that delicacy which never fails to appeal to a dog—cold boiled liver, slightly sprinkled with anise.

Then, with the liver in one hand and his club very much at the ready in the other, he mounted the steps.

He had not set foot on the topmost of the steps when, with a blood-curdling snarl, Cerberus bounded into view from out of a big stone kennel in the middle of the hall.

FOR a moment he and Hercules surveyed each other. Neither had

ever before seen anything quite like the other, and consequently

both were interested. Cerberus was, indeed, as unique a dog as

Hercules had always been given to understand; he had three heads,

one of which—the middle—was pure bulldog, massy,

heavy-jawed and extraordinarily wrinkled. The left or near head

was distinctly that of a well-bred old English bob-tailed sheep

dog; and the head on the right was exactly that of a good

foxhound. The body, too, was that of a very large foxhound, with

plenty of good bone, and the tail was barbed.

All the heads were growling savagely—two at Hercules and the left at the fox-hound head. There seemed to be very little love lost between the two outside heads. Hercules noted this and consequently threw the piece of liver to the sheep-dog, which deftly caught it as it fell.

Instantly there was a dog-fight of a richness and variety which Hercules had never before dreamed was possible. He stared, lost in wonder and amazement. Almost before the sheep-dog head had seized the liver he was pinned by the ear by the bulldog. With a frantic yelp of rage the sheep-dog dropped the liver, which was promptly snatched up by the hound, with the result that he immediately found himself called upon to fight for his life against the joint heads of the sheep-dog and the bull. Grinning with fury, he turned upon his two companions and "mixed it" right royally with them until by accident the sheep-dog gave the bull a nasty nip among his wrinkles, thus drawing the attentions of both bull and foxhound upon himself.

Grinning with rage, the hound-dog head turned

upon his two companions and "mixed it" with them.

The clamor of them was deafening. It was superlatively civil war—precisely as Hercules had planned it. Cerberus had long ago ceased to notice Hercules—he was much too insistently engaged on his own affairs. And so, after watching the fight until he felt himself becoming dizzy, Hercules, perceiving that the position of each head rendered it impossible for one seriously to injure either of the others, turned away from the unique spectacle and crossed the great hall to a door in which was a pigeonhole labeled "Inquiries."

HE rapped peremptorily on the panel which closed the

pigeonhole, and after a little delay it was slid back and a

heavy-eyed porter with abundant whiskers looked out.

"What is it?" he asked sourly.

"An envoy from Eurystheus, King of Mycenae, to Pluto, King of Hades!" replied Hercules sharply.

"Envoy! What's an envoy?" grumbled the man. "Envoys cut no ice here!"

"Naturally!" replied Hercules, with a chuckle. "Not bad that, what!"

He grew stern again, and laid the end of his club on the ledge under the porter's face.

"Perhaps that does," he rapped out.

Evidently it did, for the porter became a trifle more respectful.

"What's the good of coming to Hades at five o'clock in the morning?" he demanded. "The King isn't up—nor aint likely to be for another four hours."

Hercules pondered, and as he pondered it dawned on him that he was hungry.

"Very well, I'll wait. Just turn out a cook or a butler or something and give me some breakfast, will you? Unless," he added blandly, seeing that the man hesitated, "you particularly desire me to report adversely to the King upon the inhospitable character of my reception here!"

The porter suddenly was galvanized into activity.

"Pardon, my lord," he said. "I am but just awake from dead sleep. You are the first who has ever got past the dog—"

"That's all right, my man," replied Hercules. "The dog was too busy settling a little difference of opinion with himself and his friends to trouble about me."

The porter threw back the door.

"Enter, my lord," he said, and in accordance with what Hercules afterward learned was the custom, added sonorously:

"Abandon hope, all ye who enter here!"

Hercules stared at him.

"Not at all. Why should I? You appear to be a bit of a pessimist, what! Do hurry up that breakfast."

And so passed in.

WITHIN the next two hours Hercules had eaten an unexpectedly good breakfast, enjoyed a hot—very hot—bath, and had made himself much more solid with Cerberus by the simple process of taking each head a big bone.

Then he had returned to the apartment in which he had breakfasted and adjourned to a big couch in a corner to rest for an hour or two. For some moments he had pondered whether it would be worth his while to hunt up a rod from somewhere and have an hour with the trout in that likely-looking stream, the Styx, but finally he had decided against it.

He wrapped his big lion-skin well round him, turned the lamp low, and dropped off to sleep almost immediately.

It seemed to him that he had not been sleeping more than perhaps five minutes—though in reality it was well over an hour—when he was roused by the sound of whispering. He was wide awake in an instant—a very necessary habit to a man of his type in those days—and without moving, listened.

Evidently the whisperers were in the room, for he could hear every word distinctly. And it was equally evident that their business was secret, by reason of the fact that they did not turn up the light.

"We—the court—shall be ready within a week," whispered one of the newcomers—a woman. "There are only just the four to win over—and I can answer for three of them. How are you progressing with the people and the troops?"

"Fine, fine," came the whispered reply—a man this time. "The Trade Unions are practically solid for me—or at least they will be in a week's time, when my big remittances arrive. And the reports about the troops are most promising. The Hades Hussars are with us to a man. It is just a question of the Household troops—the Bodyguard. I understand that they've had no pay for weeks. Work on that, my dear. It should just do the business. We must have the Bodyguard with us before we can dream of a coup d'état! Never mind about the politicals now—though do what you can, of course. Concentrate on the officers and N.C.O.'s of the Household troops. Be secret, but be bold. You are not on such dangerous grounds as you think. All Hades is tired of Pluto—it is only a question of months before he is flung out even without us. With us it should be a matter of days only!"

"And the Queen is mine—you understand that clearly. I am to do as I like about Persephone."

"How you hate her!" whispered the man. "But yes—certainly, Mintha. You shall have absolute power to decide the fate of Persephone!"

"Good!" came the sibilant whisper of the woman. "That's all, I think?"

"For the present, yes. Good-bye, Mintha, dear! You still love me?"

"Need you ask, Jakae? Good-bye! I must fly!"

THE conspirators rustled stealthily out of the room, and

Hercules sat up.

"It seems to me that I have been overhearing secrets, what!" he mused. "Jakae—whoever he may be—and Mintha are evidently engaged in what looks like being a successful little revolution in Hades."

He reflected.

"Mintha's fearfully bitter against Queen Persephone." He shook his head. "That won't do," he added. "It doesn't seem quite cricket to stand by and see her thrown into the clutches of that Mintha, who certainly sounded rather a terror, what! Of course it's no affair of mine if they're getting up a revolution in Hades, but—well, dash it all, a man has got to be on one side or the other, and I'm a royalist. Always have been, anyway, what! I must go into this at the first opportunity," he decided.

He had not long to wait, for at that moment a chamberlain came in announcing that Pluto had been informed of his visit, and, having now breakfasted, was ready to give him an audience.

"Thanks very much," said Hercules, rising and taking his club from the settee.

"You won't need that," said the courtier, with a slightly superior smile.

"Possibly not," replied Hercules blandly, "but I'll take it along. Always feel such an ass without it, what!"

"As you wish, of course," said the courtier. "This way."

HERCULES followed him through innumerable corridors to the

great hall in which the king of Hades usually gave audience.

Evidently Hercules' reputation had reached as far as Hades, for

the crowd of courtiers and hangers-on of royalty generally, with

which the hall was filled, very respectfully made way for him as

he followed the chamberlain up to the throne upon which sat Pluto

and Persephone, awaiting him. There were many whisperings.

"That's he, eh? ... Who? ... Yes, Hercules—the Terrible Greek. Enormous—gigantic! Notice the club ... Famous big-game man. Oh, yes—killed Nemean lion—might have been a kitten. Remarkable person, very—fearless chap Oh, quite—lives Mycenae—great friend Eurystheus ... Grand wrestler—rather! Challenge him best two falls out of three ... Graeco ... You wrestle him? Don't be foolish. Ha, ha, very probable! One does not think so ... Ssh! He's greeting Pluto—stout fellow, what?" ran the confused comments as Hercules bowed before Pluto and the Queen. He noted, as he did so, that Cerberus, newly groomed, was crouching at Pluto's feet.

"Welcome to Hades, Hercules," said Pluto—a tall, stout, bearded, rather untidy person, with a cold eye and an egg-stain on his beard. The Queen bowed with a slight smile.

"Thanks very much, Your Majesties," said Hercules easily.

"This is your first visit here?" continued the King, motioning to an attendant to place a seat for Hercules.

"Yes," said Hercules, sitting.

"And what do you think of Hades?" inquired the Queen, smiling. She was a somewhat passé, rather acidulated-looking lady, clearly verging on middle age.

"Well, Your Majesty, I have seen very little of it yet, but what I have seen I like. The Styx looks like an ideal trout-stream, and I should say it's a very fine hunting country once you get clear of the rocks," replied Hercules diplomatically. "Have you plenty of foxes?"

The court looked at each other with puzzled eyes.

"I'm afraid we don't understand much about hunting here," said Pluto.

Hercules looked astonished.

"Don't understand hunting!" he echoed. "Why, what do you do, sir?"

Pluto smiled frostily.

"Oh, we have our—er—diversions!" he said. "We are rarely dull here."

"That I can very easily believe," replied Hercules. "But I assure Your Majesties you ought to start a pack here—with yourself as M.F.H., I suggest, sir. Life without fox-hunting is like—er—well, thirst without drinks! Look here, sir," he went on enthusiastically, "I've no doubt King Eurystheus would be very glad to send you down a few couples of hounds to start, and I could make you up a fair pack by getting in more couples from friends of mine in different parts of the country!"

PLUTO pondered. It was apparent that the suggestion that he

should be M.F.H. tickled his vanity, though he hardly looked

like a riding man.

"Thank you, Hercules," he said. "I will turn the matter over in my mind."

"Do, Your Majesty, do; you will never regret it! By the way, sir, you have a grand beginning of a pack at your feet—Cerberus. That off head of his is about the most perfect foxhound head I've ever seen. Grand dog, sir!"

"Yes," said Pluto. "We flatter ourselves that we know a good dog in Hades when we see one!"

"It was really about Cerberus that King Eurystheus commanded me to call upon you," said Hercules, seeing a favorable opening.

"Indeed!"

"Yes. You see, Your Majesty, there is going to be held shortly at Tiryns the biggest and smartest dog-show ever known—" And Hercules rapidly explained matters.

"And as it was essential that the Queen should exhibit something very special, something that would amaze society, the King bade me wait upon you in the hope that you would allow the Queen to enter Cerberus for exhibition," he concluded rather anxiously.

"I never lend my dog," said Pluto coldly. "I do not believe in making a fool of a dog. One master is enough for any dog. I wouldn't give that!"—he snapped his fingers—"for a dog that would follow anybody."

A murmur of approval ran round the court. The Queen nodded, and even Hercules felt that Pluto was right.

"Quite right, Your Majesty," he said. "Eurystheus would be the first to agree. But he thought that, the circumstances being exceptional—"

"Oh, but that's the Queen's own fault—" began Persephone. Pluto silenced her with a look.

"I don't see it," he said. "It isn't our dog-show. We don't have dog-shows here. Don't believe in 'em. I've got the best dog in Hades, and everybody knows it. What's the good of having dog-shows when things are like that? No," he continued, "I don't see it. I hope I know what is due from one king to another, but I think that to ask a man to lend his dog to another man's wife for exhibition at a dog-show is stretching things too far. I'm sorry, but I can't do it. No. I refuse. Certainly not. It's impossible, quite."

Persephone murmured something in the king's ear.

"Besides, it's illegal—even for me. I made the law myself. The fact is, there used to be too much lending out of things from Hades, and I had to put a stop to it. Things never used to be returned. The law is that nothing shall go out of Hades without something of proportionate value coming in—unless, of course," he added sarcastically, "it is taken out by force."

Hercules suddenly remembered the whispers, Jakae and Mintha, who had become rather a trump card now, he reflected, and he rose and came close to Pluto.

"Suppose I could tell Your Majesty of a plot against your life and throne—and name the chief conspirators!" he said softly. "Would you regard that as 'proportionate value' for the loan of Cerberus?"

Pluto smiled unpleasantly.

"If you refer to the conspiracy of Jakae, the court bandmaster, and Mintha, the toe-dancer, to enlist the aid of the Trades Unions and the Household Cavalry in an effort to carry out a coup d'état," said he, "you are considerably too late. The silly plot was discovered an hour ago, and the conspirators have been—er—attended to. We have a quick way with plotters in Hades!"

"In that case, then, I can only obtain the loan of Cerberus by force," said Hercules gently.

THERE was a roar of laughter. The idea of anyone being able

to capture and subdue Cerberus seemed to strike the court as too

humorous.

"Certainly," said Pluto, laughing immoderately. "If you can get him to come with you I will cheerfully allow you both to go without hindrance."

"You mean that, Your Majesty?" said Hercules.

"I do, indeed."

"Very good—and thanks very much."

Hercules stepped back and swung his club round to warn the court to keep a clear space. They watched in silence while he drew a long rope, thin but very strong, from his haversack. At one end of this he made a noose. The other end he threw over a hook in the ceiling, from which ordinarily hung a chandelier that, probably, had been removed for cleaning or repairing.

The courtiers looked on, giggling. Persephone was smiling her faded, rather contemptuous smile, and Pluto also was frankly scornful. Nevertheless he was the first to guess what Hercules' tactics were to be, for the latter turned to Cerberus, his club under his arm, a noose dangling from the other.

"Sss! At him, boy! Tear 'em!" hissed Pluto, and Cerberus leaped at Hercules like three raving tigers. But Hercules was ready. He stepped lightly aside as the great beast shot past, and plastered the bait against the face of the bob-tailed sheep-dog's head as he dodged.

Once more the heads clean forgot Hercules in their frantic lust for liver. Canine civil war again raged in Hades—but not for long. Moving with extraordinary quickness, Hercules wheeled, and dropping his noose over the fiercely wagging tail of the dog, swiftly drew it tight and rushed to the loosely hanging end of the rope, which he hauled in desperately, hand over hand.

Almost instantly the rope tightened. The noose slipped bit by bit, but was suddenly brought up by the big barb in Cerberus' tail.

And then Hercules hauled on the rope like lightning. Long before the heads of the great dog realized that something was seriously wrong its hind-quarters were raised off the ground. For a second its forefeet scrabbled furiously upon the polished floor as it tried to get a grip, but it was too late. Hercules, excitedly bawling a chanty which he had evidently heard sailors singing when hauling up their sails, pulled on his rope as only Hercules could pull.

There could only be one end to it.

In five seconds Cerberus was well off the ground, and suspended from the chandelier hook was swinging gently to and fro, spinning as he swung, and yelling imprecations in three different dialects and keys—viz., hound, bulldog and bob-tail or barb-tail, as one chooses.

HASTILY fastening his end of the rope to the leg of a grand

piano close by, Hercules took three muzzles from his haversack

and, with the deftness of a man used to dogs, swiftly muzzled the

outside heads first, and lastly the bulldog. Then he tied the

forelegs, and next the hind-legs. Finally he turned to Pluto,

with a slight bow.

"My game, I think, sir!" he said politely.

Mortified, disgusted, annoyed, discomfited, humiliated, and disconcerted though Pluto was, he was also a gentleman.

"Oh, quite! I congratulate you," he said, with not too palpable an effort. The Queen said nothing. She was too vexed to pretend to be anything but vexed. There was an ominous silence—and as he noted the silence an ominous shifting to a comfortable grip of Hercules' clubs. But Pluto was a king—though perhaps his kingdom was not much envied him—and knew how to behave. He rose, and in a voice trembling with rage, said:

"I must terminate the—er—audience now. There are important—ah—affairs of State. Treat the dog well—he is a good dog. And—er—consider all Hades at your disposal during your stay."

And without another word he and the Queen, followed by a goodly proportion of the courtiers, left the hall.

A LITTLE uncomfortable, Hercules was hesitating quite how to

proceed, when an elderly old beau of very worldly appearance

approached him, and whispered:

"Take the advice of an old habitué of Hades, Hercules, and get the beastly brute out of it as soon as possible. The King's bitterly angry about it."

Hercules smiled.

"Sound scheme, that," he said. "I will. You don't seem to care for Cerberus, sir," he added.

The old beau shuddered.

"I don't," he said. "The brute once bit me—with all three of his mouths!" And he hurried away.

Like most men who can be brave in cold blood, Hercules knew when a quick retreat was good strategy.

He lost no time.

Bluntly declining a cup of wine sent him with Queen Persephone's compliments (and which the delighted lackey took behind a curtain to drink himself—an unfortunate decision, for the wine contained enough aconite to poison a goat), he hoisted Cerberus on his shoulders and started ....

It was five in the morning when he had reached Hades. By eleven he was on the right side of the Styx—extremely good work when one considers the weight of the dog. And it was not until he was a good twenty miles clear of the entrance of the carriage-drive that he began to drop into the steady, comfortable stride that within the course of the next few days would land him comfortably home—just in time, he estimated, for the week-end meet at the crossroads, to which, he knew, the gallant old weight-carrier, Pegasus, (now his own), was looking forward as keenly as he and Eurystheus.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.