RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

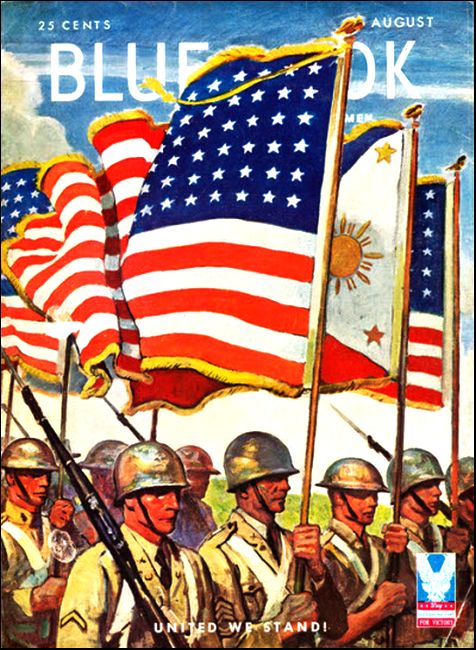

The Blue Book Magazine, May 1943, with "A Parrot in Paradise"

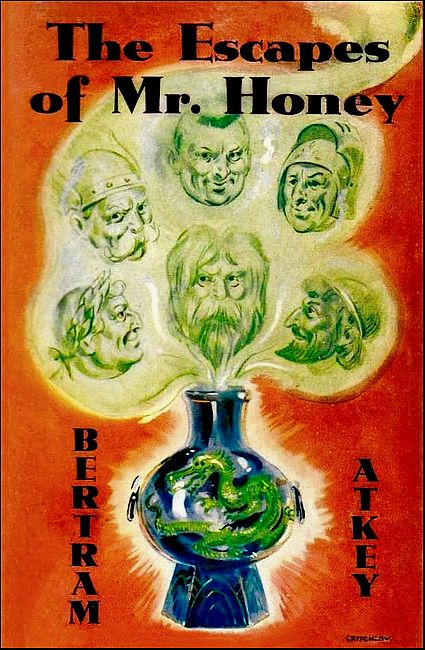

"The Escapes of Mr. Honey," MacDonald & Co., London, 1944,

with "The Garden of Eden" ("A Parrot in Paradise")

HIS rapidly increasing experience of the staggering possibilities of the Lama's pills had led Mr Hobart Honey to the conclusion that the chances of any one pill landing him back into an incarnation in which he really had been a great man were not so good.

He was not proud of this—but, against that, he was getting out of the habit of being ashamed of it. As he put it to himself one evening:

"After all, I believe I've got a right to consider myself an averagely decent, civilised sort of citizen in this life, so why worry about what sort of person I was in a life I lived a few hundred or, for that matter, a few thousand years ago. Nothing can be done about it, anyway. It appears that I was the man who shot King Rufus in the year 1100. All right. What are they going to do about it? It seems that I was the eunuch that embezzled a few dozen of the wives of Prince Demetrius and sold 'em to Ptolemy, King of Egypt. Well, what if I did? They can't arrest me for it—303 B.C. was a long time ago—and the prehistoric considerably longer. And the experiences were interesting—well worth reliving. I think I'll take another trip into the Bygone this evening."

He settled himself comfortably in his easy chair and fortifying himself with a glass or two of wine swallowed one of the pills with a practised ease.

It took him back to an incarnation in which he was an elderly carrion-eating condor who spent the whole time between rare feasts of carrion in circling round and around somewhere up in the stratosphere over the Andes reflecting on modern carrion, its scarcity and poor quality compared with the carrion of his youth.

A dull life, and of no value to an author of the twentieth century like Mr Honey—unless a precise knowledge of what it feels like to be one of the world's leading epicures of carrion, is valuable.

An evening wasted as far as Mr Honey was concerned.

He shrugged his shoulders, took a little more wine and selected another pill.

He was conscious of a curious feeling, as the little pellet passed his glottis, that there was Something Coming this time—that he was bound for a life in which he was going to meet Folks that really were Folks. He had often enough had this feeling before, but never quite so pronouncedly. Even as he blacked out he was muttering to himself about it...

HE woke slowly, and, as was usual, a little confused—with

the familiar confusion of feeling that he was really Hobart

Honey, of London, but knowing that he was by no means so; feeling

that he had only left London a few seconds before, yet knowing

that the first foundation stone of London would not be laid for a

good many years to come—that the site of London, in fact,

still lay a few miles under the sea.

He felt himself cautiously, before he opened his eyes, and found himself to be highly hairy all over.

Then he scratched himself a little, and felt all the more comfortable for it.

For a few minutes he lay, pleasantly warm under the sun, breathing deeply the marvellous scents of what could only be a miraculous wealth of flowers. He listened dreamily to the soft sigh of perfumed zephyrs wandering around and about, and he knew that life was very good indeed. He scratched himself a little more, and was distantly conscious of a faint unease, which he characterised as the merest hint of hunger. Still, for a little, he lay blandly relaxed, listening to a melody of birds singing softly in the perfumed and spicy little winds about him. At last he realised where and what he was. He was Nn the Near-Man—that is to say, the nearest creature to Man that a creature could possibly be without actually being Man himself.

He was the personal servant of the First Man of His Period—or, for that matter, of any other Period either.

Nn was very proud of this. He lay there, lost in his delicious languor like a man in a bath of warm, perfumed oil. He knew it was well past dawn, but he knew there was no need to hurry. His parrot, roosting in the fig tree under which Nn had slept, would tell him when the Boss was on the point of waking up.

And even then, life would be as lovely. There would be no complications. Breakfast was ready. By the side of the Boss were heaps of everything good—he only had to reach out his hand—needn't even open his eyes—just only reach out and take what he touched—shaddocks, mango, durians, dates, persimmons, peaches, pomegranates, pears, grapes, plums, nectarines, oranges, figs, fruit, in fact. Fruit of every known variety and dozens of varieties not known nor ever likely to be. And nuts—more kinds of nuts than the modern mind ever conceived—nuts that tasted like everything, from a coconut to a ham-sandwich or a chocolate sundae.

For this was the Garden of Eden, and Nn's boss was Adam...

He lay there dreamily, thinking of this truly noble First Man whom he was privileged to serve and to adore; and of the old days, when he had left the wandering tribe of Near-Men, to which he belonged, to journey on through the tree-tops in which they spent roughly ninety-five percent of their valueless time—wisely, for the country was unlimited of lions and teemed with tigers and similar meat-eating creatures.

"How fortunate I was," mused Nn, "to have been found by him when I was!"

That was entirely true, for Nn was in somewhat of a jam when he first set eyes on Adam.

He had come down out of the tree-tops, at the edge of the forest where it joined the desert, to get a drink of water at a pool surrounded by tall rocks. He stepped round the tallest rocks and found that he was not the only denizen of the district who liked a little water now and then. Eleven maneless lions, six tigers, quite a number of leopards, several black panthers, four rhinoceroses, six bull elephants, nine cow ones, and about a couple of dozen big buffaloes were around the pool also.

Nn took a look at them all and turned a double backward somersault—into the rock, due to a sort of over-anxiety, very natural in one so solitary and unarmed.

They, in their turn, took a look at the Near-Man. He was one of these scrawny, scraggy Near-Men and quite a few of the menagerie were uninterested in him. But not all of them—six lions, three tigers, most of the leopards, and all the black panthers started for him, and he had already said farewell to his native tree-tops when, suddenly, there strolled round another rock a being whose appearance on the scene short-circuited all local activities like a flash of lightning.

All the animals rose, politely, and those that were bounding towards the Near-Man suddenly ceased bounding. They slewed round, trying sheepishly to look as if they had only been hurrying to the Near-Man to gambol with him a little.

They wagged their tails apologetically, then placed them between their legs, as they stared past—not into the eyes—of the new-comer, who shook his head, then laughed quietly and spoke briefly. Evidently it was a word of friendly advice to go while going was possible, for they went like guilty things glad of a chance to go. The elephants, rhinoceroses and buffaloes did not go, but stood about in attitudes of respect and deference.

Yet the superb new-comer, noted the Near-Man, was not merely unarmed—he was undressed—well, nude. It was something in his eyes that quelled the animals—Nn took a look in the eyes and felt quelled himself—quelled but adoring. He was still quaking from the shock of the great beasts, and as he stared dumbly at the magnificent apparition who had saved him he trembled at some other cause that was not fear. Gratitude—admiration—something of that sort, no doubt.

HE saw a tall creature—like a god, he would have

thought, if he had ever heard of a god—immensely tall,

almost gigantic by modern standards, but symmetrical to the last

decimal of an inch. Under his golden skin, smooth muscle rippled

and played at every movement; under a close helmet of

crisply-curled gold hair, and a broad, smooth brow, shone, with

an electric intensity a pair of blue eyes that—by the

Near-Man, at any rate—could not long be looked into. The

head was noble—set high on a muscular neck that was as

graceful, swift and flexible as that of a cobra. On the clean,

clear, curved lips was the friendliest smile that the Near-Man

had ever known or dreamed of—and over all the glowing

strength and beauty, and in spite of the unbearable brilliance of

those piercing eyes, there was, the Near-Man sensed, a monumental

and virginal innocence.

Nn suddenly bowed down, his face in the sand, trembling... He did not know it yet, but he had been looking at Man—at Adam, the First Man—and he was not accustomed to that sort of thing. The Founder of the race of Man was, rather obviously, something special—well, look at us!...

A golden voice, strong as sunlight, gentle as dusk, came to the Near-Man as he abased himself.

"Be not afraid!"

Then, as he quaked, hiding his face in the hot sands, the trembling Near-Man felt an arm, strong as steel, yet gentle as compassion, pass round him.

"Why, thou poor thing, be not afraid, I say. Thou art with me and henceforward thou shalt be under my protection—and I am Man!"

He lifted the scrawny wretch, like a rag, from the sand.

"Courage!" he said, and looked at Nn with smiling, brilliant eyes.

"Art thou hungry? Nay? Art thou thirsty? Yea, I see—thou camest here for that? Drink, then, and come with me."

"Yes, sir!" said Nn the Near-Man humbly.

He had drunk his fill while Adam waited. Then they had turned their backs on the pool and strolled together across the desert to the Garden of Eden—having established, though, in their innocence, neither knew it, the first social distinction known on earth...

IT was upon this event that Nn pondered dreamily as he lay,

still half-asleep, that morning. He smiled—a trick he had

learned from Adam—as he remembered it all.

Then a small cloud passed over the sun of his personal content as he remembered something else. They had been happy enough, he and his master, for months after he had secured the situation. But it had been a sinecure, judged by modern standards. That is to say, one cannot be a valet to a gentleman who does not wear clothes, nor can one be a cook to an employer who lives on an exclusive diet of fruit and nuts. One can, of course, crack his nuts for him, but why painfully crack nuts between two rocks for an easy Hercules who can crack his own between finger and thumb?

No—Nn was not overworked.

Perhaps that was why he became so observant of Adam.

Latterly he had begun to suspect that Adam was bored and lonely. He, Nn, thought of the word as "lonely," though he hardly knew what it meant. But he knew this, that the manner of his master was more and more frequently distrait; that he turned at eventide away from his lookings, his expectancies, as if he were sad and, in a vital way, distressed...

THEN, one morning, Nn's parrot, Irony (so called because Nn

thought it was a pretty sound), a beautiful sketch in scarlet,

green, gold, blue and pale pink, which had been nattering to

itself for a long time—rather like a well-satisfied person

talking in its sleep—uttered a sudden ear-piercing

whistle.

It was, as both Nn and Irony—the only living thing after Adam, Nn loved—understood it, an alarm.

Nn woke suddenly as the bird, abandoning the alarm, began to talk.

"Somebody hath come here in the night! Nn—somebody hath come in the night!"

Nn sat up.

"It is well," he said. "I will see to it. Meantime, wake not the Chief with thy whistlings! Where is the person who hath come in the night? Quietly!"

Nn got up.

"Show me," he commanded.

"This way," said the parrot.

Nn followed a flutter of scarlet wings...

She was lying, fast asleep, under a fig tree not far from Adam.

Nn took a look, caught his breath, and decided, without any difficulty at all, that he had never seen anything remotely resembling it in his life.

Beauty? Why she dimmed the sunrise!

Nn stared—beauty stricken.

Irony fluttered down to perch on his shoulder, took a long, long look, and screwed its scrawny neck to look up at Nn.

"Hast thou ever observed the like in the whole period of thy natural life?" it asked.

"Nay, bird, not so. I have not seen," muttered Nn. "It dimmeth mine eyes!"

He spoke the bare truth. The little, deep-sunken eyes of the Near-Man were full of inexplicable tears.

"She is lovely past understanding," said the parrot.

"Why dost thou say she?" asked Nn, puzzled. "She? She? That is a word I have not heard!"

The parrot chuckled—much as present-day parrots chuckle.

"I invented it! I, the parrot! It is a good word and it will frequently be heard when the world grows older."

"I think so, too!" said Nn. Still staring through his unconscious tears, he continued. "Bird, thou art wise, well experienced and far-travelled. Thinkest thou that She will permit such as I to serve her, to attend her, to follow humbly in her shadow, ever-obedient, ever-attentive to her least wish?"

"Yea—and even so," said Irony. "She will permit! Thou shalt never lack somewhat to perform in her service, Nn! As I believe it to be!"

He fluttered a scarlet wing and scratched a purple poll.

"She is the first thing of any importance to take place in the history of the Garden," he said. "And I, the parrot, Irony, the wise bird, advise thee that thou shouldest notify the Boss without loss of time!"

"Yes, that I will!" said Nn—and lingered still. "I mind me now how he hath gazed so wistfully down the vistas! Thinkest thou, bird, that he hath gazed for such as She?"

"I am incurably convinced of it," said the parrot. "How could it be otherwise? Look at her!"

Nn looked some more. He had been looking all the time they had been talking, but his eyes were not weary.

Yet he dared not linger.

"Watch well over She while She sleeps!" he said. "I will now notify the Boss!"

He crept away, looking over his shoulder. He flattened an ear against a coconut palm as he walked sideways and so, abruptly, looked to his front...

ADAM was awake, eating fruit.

He smiled on Nn as the Near-Man crept up.

"Sir," said Nn, a little hysterically, "She hath arrived in the night!"

Adam bounded to his feet, like a deer.

"She... That is a word which I have not heard!" he said.

"Yet it will never again be unknown—said the parrot, sir!" said Nn, inventing boldly, though he was abasing himself to the ground.

"Thou art strangely humble, Nn!" observed Adam.

"Sir, I have seen that to render me humble!" said Nn—which was pretty fair for a Near-Man.

"Take me there," said Adam smiling, "and let us see if it can humble me!"

So Nn took him,—and left him there.

Even if he had looked over his shoulder—as he did—Nn would have seen no more than a superb example of Love at First Sight...

TO say that Eve was the loveliest woman that Adam had ever

seen would, of course, be equivalent to saying precisely nothing.

He had never seen a woman before. (There were, he understood, a

number of near-women, relatives of Nn, haunting about in the

tree-tops of the forests, but these he classed, rightly, with the

orangs and chimps.) Eve was something new—too new to be

true. For a full hour he gazed upon her, thrilled and

fascinated.

"She is utterly beautiful, yet She is different from me. She is round in places where I am flat. Yet I am beautiful, too!" he said, naively but quite truthfully. "So I suppose flat is beautiful and round is also beautiful. How nice. I wonder if she would mind if I touch her—it would be wonderful to touch. And, after all, she is mine—everything in the garden is mine. It must be. Besides, it cannot be intended that I should stand here and stare at her forever. She cannot have come here just to be stared at in her sleep. She must have been sent into the world for some good purpose, though what on earth I am going to do with her I do not know. Perhaps she would know—I will awaken her and see."

Some dim instinct checked his outstretched hand—a faint, far consciousness that perhaps it would be just as well to provide something for her before he woke her—a little breakfast, a selection of mixed fruit or something of that sort. He thought hard. Yes, definitely the tactful, propitiating thing to do, he decided.

It was an important decision—probably the most important decision ever made in the world—for it started a fashion which has persisted to this day—if that instinct to propitiate and please womenkind which is inextricably a part of mankind's make-up can properly be called a fashion.

He arranged the fruit as attractively as he could within easy reach, then very gently smoothed her cheek with the backs of his curved fingers.

"O, lovely one!" he whispered. "Wilt thou not wake up now, please?"

Her eyes opened so instantly that—as it occurred to Adam long afterwards—she might almost have been already awake. For a long time the deep amethyst eyes countered the electric gaze of Adam—then, surprisingly, they fell. For a few seconds only.

Then she raised a slim hand to hold Adam's, still caressing her cheek.

"Oh—Oh—Oh—but I have dreamed of thee this whole night long," she said in a voice so magic and so musical that Adam thrilled like a plucked harp-string.

"Sayest thou, O Splendour of the Dawn!" replied Adam, trembling. "And I have sought throughout Eden and far across the deserts beyond it these many days and desperately dreamed these many nights for what it was I knew not, but which I now know is that which I have found. It was for thee I looked and longed!"

They stared at each other. Again her eyes fell.

"Mine eyes are dazzled," she cooed.

"But mine are enriched!" said Adam, and took her in his arms.

"But nay—nay! It is so public here!" she demurred.

"Not so," said Adam. "This is private property—private as far as the eye can reach, and beyond and beyond that again."

"But whose?" murmured Eve.

"Mine! Save only for one small, gnarled and writhen tree!"

Eve took him in her arms.

"Ours," she sighed.

"Nay, thine!" said Adam, generous as he was beautiful. "With this—all this—forever I endow thee—for thy sweet beauty's sake!"

That, too, in its way, was another important decision.

She kissed him, murmuring and fond...

This, being the record of Mr Hobart Honey's experience in the incarnation of Nn the Near-Man, is not the proper place in which to follow in any sort of detail the lovely life of Adam and Eve during their first few months in the Garden of Eden.*

[* Should any frenzied Public Demand for such a record of Life in the Garden of Eden arise, no doubt it can be furnished upon receipt of the usual fees by... Bertram.]

Probably the most beautiful, possibly the noblest, certainly the first Love Story in the world, it went, in its superior way, pretty well like all subsequent genuine love affairs. It had its ups and downs, of course,—and Nn was mainly concerned with its downs. Few lovers require the attendance of either a Near-Man or a parrot when their affairs are going well, so Nn and his parrot were thrown pretty much on their own resources for a long time after the arrival of Eve.

They managed.

THEN, one day, Nn, strolling about the Garden with nothing to

do, paused in surprise before the tree which Adam had always

firmly instructed him was not, in any circumstances whatever, to

be touched.

"Nor, mark ye well, Nn, is fruit to be plucked from it—never—in no circumstances whatever," Adam adjured him.

"No, sir!" he had promised, never believing that such an ugly, gnarled, knotty, twisted, inexplicable-looking tree would ever bear any fruit.

Now, to his amazement, the tree was brilliant with the most exquisitely-shaped and coloured fruit the Near-Man had ever seen—and he had seen considerable fruit in his time.

He hung about for a while, admiring it. Naturally, it never occurred to him to touch it after Adam's prohibition. But it was otherwise with Irony, the parrot, which flew across before Nn could forbid it, and tried the fruit.

"It's good—of its kind," said the bird. "It kind of stimulates your mind—though, for flavour, I prefer a good pomegranate!"

Nn, startled at the freedom of the rainbow-hued bird on his shoulder, was about to move on when a being moved out from behind the twisted trunk of the tree—a tall, dark, handsome brute in man's shape who would have reminded Nn of Mephistopheles if he had ever heard of Mephistopheles.

This one had fixed the startled Near-Man with a pair of glittering eyes.

"Leave those apples alone!" he commanded.

"Yes, sir!" said Nn hurriedly, shuddering under the glare of those mesmeric eyes.

"Return whence thou camest and tell the Lady of Eden—that lovely Human called by the First Man Eve, that the fruit of the tree has ripened and is ready. Tell her no more—nor less—than I have said."

"Yes, sir," said Nn, humbly. "What name shall I say, sir?"

"Name? Name?"

The Dark One smoothed his gleaming, pointed beard, reflectively.

"Name? Say The Snake"—his eye fell on a patch of tall, gently wind-waved grass beyond the Tree—"Say The-Snake-in-the-Grass sent word."

He laughed. It was a silently suggestive sound, like the flicker of forked lightning seen afar off.

"No. Say A. Snake, Esq. sent word. She will know! Mention it not to Adam! Dost thou understand?"

The Near-Man hung fire.

"Sir," he quavered, "to my Lord Adam, who saved me from the great beasts, I mention all things."

"Fool," said the parrot, who had partaken of the fruit.

"Well said, bird or evil spirit, I know not—nor care," said Snake. "Mark it well, Near-Man, that if the Lady of Eden thinks it fitting that her Lord should know then she will tell him—not such as thou art, Near-Man."

"Yes, sir—no, sir," said Nn.

"Get gone!" said Snake dangerously.

Nn got went...*

[* Origin of the word 'slunk'. When we say in a person 'slunk'—we mean he 'got went away hurriedly'... In a way —Bertram.]

HER laugh, when Nn passed on his message, sounded as innocent

and as charming as the laugh of a child about to engage on a

trifling mischief.

And, indeed, it was no more to her than a trifling mischief. She had only deceived Adam once before—that time when he was calling her and it had seemed to her to be just a playful little amusing thing to hide behind some bushes as if she were far away. She had come out at once when he sounded forlorn and frightened. They had cried a little about that—it was a new thing—but in the end they had laughed.*

[* The birth of a new joke was always difficult and painful. Hiding from your husband is an old joke nowadays. Eve first thought of it. —Bertram.]

Nn did as he was told next morning when Adam had gone, for

once alone, to bathe.

"Yes—I understand," said Eve, distantly. Later, lurking in the brushwood, Nn saw her pick up a woven basket and go out in the direction of the forbidden tree.

"Oh, she is wrong!" lamented Nn, in a dumb, instinctive way.

"Fool, she is utterly right," said the parrot—not so polite as formerly. The fruit of the Tree of Knowledge was toughening its psychology, if any.

"I must follow her and report to the Lord Adam," said Nn.

"You must mind your own business!" said the parrot, acidly. "That's common sense—if not more."

"You're telling me," said Nn, "what I suppose I ought to know for myself—only I don't! Yet, I know, somehow I feel it in my spirit, she will return a different woman."

The parrot chuckled.

"This time you're telling me," said the bird cryptically. "Madam is not one to stand still and congeal. Madam is a lady who progresses fast!"

"Why do you call her 'Madam'? That is a new word," said Nn.

"And a good one. It is a word which will endure in no uncertain fashion for All Time, brother!" prophesied the sagacious bird—correctly...

SHE came back, flushed, excited, and too lovely to be true. In

her hand she carried a little basket of fruit.

Even Adam, getting more used to her than he had once been, noticed the change.

"O, Glory of The Garden, what hath come unto thee this day? Thine eyes are stars—thou art all my dreams come utterly true."

He slipped his arm around her.

But Eve only laughed.

"I have had an adventure. Come, eat the fruit which I have gathered for thee, and I will tell thee as thou eatest!"

Hungry from his swim, and attracted by the fruit, Adam did as he was told. He was halfway through the basketful by the time A. Snake, Esq., was first mentioned. Then Eve told him all that he wanted to hear—and more—about the dark, handsome stranger with the queer name who had so unexpectedly come into her life.

"He was a very interesting man—though of course compared with thee he was but as a remote star is to the sun! Oh yes, I met him quite by chance—though Nn first told me of him—and he gave me this new fruit. Dost thou like it, dear heart?"

Adam reflected.

"In a way it is good, but only—in a way. Darling, it is bitter-sweet on my tongue, and my senses swim as though of some strange poison I have eaten."

He shook his beautiful head, passing his hand across his eyes.

"I have not felt like this before," he said—naturally enough, for he had eaten heartily of the Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge—and that is a strange and sharp and heady fruit.

"Moreover, Light of Mine Eyes, I like not the sound of thy new playmate, Snake!"—here Eve saw the first frown in the history of life on his brow—"and it is in my mind that I will make a great club of hard wood and go forth and beat the life out of him ere ever this day's sun shall set. I am full of foreboding."

Somebody chuckled behind him—but it was only the parrot.

Eve's glorious eyes were round and startled.

"Adam! To beat the life out of him!" she said, shocked. "Darest thou talk so! Thou—thou—so gentle! Thou who hast ever loved and befriended all things—from the great beasts of the desert to the tiny humming birds that flit like jewels..."

She began to cry.

"Nay, nay, Dear heart, do not weep. It was but a swift, passing anger..."

"Anger! What is anger?—that is a word I have not known..."

"It will be heard again," said Adam dryly. "And other words that have but newly come crowding into my mind. Anger! Hate! Suspicion! Envy! Greed! Famine! Pestilence! And War!"

"I do not know those words—nor what they mean!" Eve was crying bitterly now.

"War! Separation! Heartbreak! Aie! Darling, they swarm about me like evil, stinging things. Yet shall we be always together in our hearts..." He broke off, staring at the fruit, struck by a new thought.

"Whence came this fruit? Came it from a gnarled and malignly-shaped, twisted and ugly tree?"

Eve nodded.

"That was the Forbidden Tree—of Knowledge. That is why I have become aware of all those new and bitter words! And of these bitter forebodings. We shall be sent forth from the Garden!"

He seized her and held her with both hands.

"Look thou into mine eyes, Eve!" he said urgently. "Thou! Hast thou, too, eaten of the fruit?"

She shook her head.

"I saved them all for thee, I love thee so!" she said.

But she was quick-witted. Before Adam could move, she snatched a handful of the fruit and crammed it into her mouth, and stood up at her full height with her arms flung wide.

Adam gaped as he stared, and another new word for his wife came into his mind.

"Perfection!"

"Now she, too, hath sinned and must suffer with me. Yet she remaineth most perfect in mine eyes!"

And, indeed, she was.

"Now I, too, have eaten of this bitter-sweet fruit, my Lord!" she cried. "And whatsoever it hath done unto thee so, too, let it do unto me! Together and alike we have dwelt in this Paradise—together and alike for good or ill we cleave and cling each to each, forever—and wheresoever!"

Nn, watching from a highly respectful distance, saw that the times were changing fast. He, of course, was only a Near-Man, and so knew all about that dull, grey feeling we call Misery. He was using a good deal of Misery just then.

He sat there anxiously watching the noble creatures he adored, and his spirits rose as he saw that Eve had stopped crying and, within Adam's arm, was smiling upon him as, unconsciously, they moved in the same direction as that in which went two huge, misty Forms which just then silently passed them all.

They carried between them, these gigantic Forms, a huge notice board upon which appeared, in enormous quite unmistakable letters, the following words—

TO THE EXIT

Slowly, reluctantly, Nn—who knew something about the Outside World—rose from his scrawny haunches to follow them. Near-Man though he was, he—like his employers—could take a hint when he got one—in thirty-six-inch letters. He heard the whistle and fluster of the parrot coming up fast behind him.

"No hurry—no hurry! Why hustle things this way!" said the parrot. "We're leaving an awful lot of good fruit behind! After all, if it's Knowledge we need why not clear the tree while we are at it? May as well hang for a bushel as a peck!"

He took another large peck.

But nobody paid any attention to him!...

Adam and Eve hesitated for just a moment—looking a while wistfully back at a very lovely scene...

"Lord, ain't they a beautiful couple?" said the parrot, impulsively. "They will be always be looking back like this—these couples! Come on, Nn!"

Near the Exit Adam and Eve checked again, looking out to the arid and rocky desert.

"Oh, how harsh and terrible!" cried Eve.

Adam laughed low.

"It might be worse! Come, Dear Heart!"

Only Nn, scuffling along behind them, heard her answer.

"With thee—anywhere!"

The parrot hung over them all, working its wings like a kind of mill.

Suddenly it squawked.

"There he is behind the banyan—seeing us off! Sir! If thou dost really desire to club him, now is the time!"

"Not that it would do any good!" muttered the uncanny fowl to itself. "This is the work of a gang, if I miss not my guess!"

Adam and Eve looked back. The creature calling himself A. Snake, Esq., was, as the parrot said, watching them from behind a big banyan tree. But even as Adam flushed and started for him, Snake vanished before their eyes.

Eve caught Adam's hand, and they turned again to the Exit, towards which the Forms were impatiently and peremptorily beckoning them.

"Place is full of strangers and illusionists," muttered the parrot.

"Art thou coming, Nn?" called Adam.

"Yes, sir!" said Nn, humbly, hurrying up.

Adam looked up, his blue eyes gleaming.

"And thou?" he asked the parrot.

"Sir," said the gaudy one, "thou can'st never make the grade without me—for I am what the new world will some day call a Sense of Humour!"

Adam laughed,

"So be it," he said.

His arm tightened around Eve.

"Come, then," he said. "Let's face it!"

But, of them all, it was only Nn who did not face it—for it was at the very moment that they all went forward into the desert that he awoke in his London flat, once more Mr Hobart Honey.

HE sat a long time quite still, thinking very deeply. He was

not proud that this sample of the Lama's pills had shown him

personally as only a Near-Man—but, against the debit of

that he could set the credit of having been the personal servant

of the unique specimen of mankind that, rather obviously, Adam

was.

And yet, after a while, it was upon Eve that his mind closed most tenderly—Eve, Mother of All...

He reached for a large glass of port with a pang of regret that the power of the pill had waned so soon. He would liked to have been in the forefront of the Battle of Life just a bit longer. That they had won it was, of course, obvious—the fact that he, Hobart Honey (not to mention a worldful of other descendants), existed proved that.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.