RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

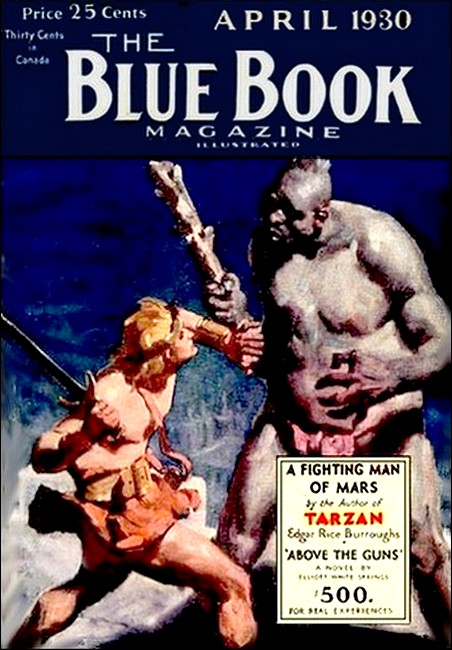

The Blue Book Magazine, April 1930, with "Back to Babylon"

"Thou art Obar-Unni, the corn-cutter of Paradise

Lane?" said the captain in a harsh military snarl.

The author of the famous "Easy Street Experts" here relates the

joyous adventure of a man enabled to revert to a previous incarnation.

"IF the lama told the truth, and the interpreter conveyed his meaning correctly," mused Mr. Hobart Honey, gazing curiously at a bottle on the Moorish coffee-table next to his armchair, "I am about to embark upon the most extraordinary series of adventures that the mind of man has ever conceived. Yes! It has, of course, been done in fiction--indeed, I have written things of the kind myself,"—(he was the Honey—the novelist and all-round fiction hack) "—but that I should ever actually experience—" He stopped abruptly. "The thing's impossible," he said flatly, "—quite! And yet the letter read like truth—as nearly as I could judge. The lama may have been an—Dr— liar—but he has a knack of making things look true. I wonder—"

Mr. Honey looked at his cat Peter—a black cat with one white ear, very quaint—who was regarding him reproachfully.

"If you could speak, Peter, it would be easy to ascertain the facts!" he said.

Mr. Honey leaned forward and turned the gas-fire a little lower. Then he got up and switched off two of the larger lamps, leaving only the table-lamp on his writing-desk burning. It was now pleasantly warm and religiously dim in the comfortable study, and Mr. Honey had given his man Trapp—who with Mrs. Trapp did the work of the bachelor flat which the novelist occupied—orders that he was not to be disturbed till twelve o'clock. It was now a few minutes to nine, and all was ready for the experiment which Mr. Honey was proposing to make—and which he had made, without communicable results, on Peter the cat, upon the previous night.

He filled a glass of sherry, took a bottle containing perhaps two hundred and fifty whitish-gray pellets or pills, of sizes varying from a pin's head to a pea, and began slowly to work out the cork.

He seemed a little nervous. But the astonishing thing was that he did not seem more so. For, as he had truly said, if a certain aged lama from Tibet had not lied, then Mr. Hobart Honey was about to engage in a very remarkable enterprise.

TO glance back for one moment— It was when Mr. Honey, touring in India to glean material and local color for his thirty-fourth book, was trotting through Benares, that he had seen a dog rush across the road evincing symptoms of desiring to bite some one abundantly. The dog did so desire. But it was not Mr. Honey whom the animal desired, at the moment, to mangle. It was a rather frowsy old gentleman walking just in front of the novelist, upon whom the dog rushed to bestow his attentions. Mr. Honey, however, thought that the creature was aiming at him, and with rare presence of mind, promptly flung his fully loaded half-plate camera at the dog. Immensely to the surprise of both the novelist and the target, the camera landed fairly upon the dog's skull, flooring it abruptly, and so completely and instantaneously dissolving its ferocity that within a second and a half it had vanished round a corner, complaining bitterly of the English.

But the old gentleman in front—who proved to be one of the most distinguished and competent lamas ever exported from Tibet—was under no delusion as to the original purpose of the dog. He knew the brute had proposed to enliven himself—not Mr. Honey. And since one of his weaknesses was a detestation of dogs—which his religion forbade him to put into practice—he was almost embarrassingly grateful to Mr. Honey, and upon subsequently learning that the Englishman was a writer of tales, had bestowed upon him a remarkable gift—namely, a bottle, itself a rare and most valuable example of Chinese glassware, containing the pellets aforesaid, which Mr. Honey learned—when, in due course, he found a man competent to translate the hieroglyphics inscribed upon an accompanying parchment—possessed the singular power of temporarily reinstating the swallower of any one of them in one of his previous existences.

Divested of the most of its flowery, picturesque, but irrelevant detail, the written message of the lama to Mr. Honey, when condensed was somewhat as follows:

"In the practice of thine art thy mind roameth afar but ever returneth unto thee heavily laden with the fruits of its wanderings. Then dost thou set thine ink-horn before thee. So it is understood by he who sendeth thee this. But it were better for thy disciples that thou shouldst know surely whereof thou writest. And how can this be if thy body accompanieth not thy wandering mind? So that thy screeds and inscriptions shall be informed with full knowledge, I send the means of sliding, as it were, thy body back through the ages, where with thine own eyes thou canst witness the things of those days as they verily were, and not as the peoples have come to imagine them to have been. Swallow the pills, which I have made with mine own hands, singly, and seek thy couch forthwith. Be not alarmed if thou shouldst awake in the form of a swine of ancient days, a lizard of the rocks, or a humble flea, for thy days thereas will be but brief, and ere thou hast time to accommodate thyself to thy new surroundings and therein take thine ease, lo! the power of the pill shall have waned and thou shalt find thyself again upon thy couch in these latter days. Fear not that thou wilt ever be what thou hast not once been. If thou hast been a great king heretofore, mayhap the power of the pill will again reinstate thee in thine ancient glory; or if thou hast been heretofore but an ass upon the hillside, a rat crawling darkly through her tunnels, or a grub, that enlargeth himself fatly and silently in the heart of the fruit—so, by my favor, thou mayest be again! And thy knowledge of things past shall wax to the uttermost limit of two hundred and fifty pills, and thou shalt be exceeding wise—so that thy fellow-scribes, scratching busily like fowls behind the granary, shall behold thy works with amazement."

SO much for the lama's letter. There was a good deal more, but not especially to the point. The extract conveys the idea tolerably well.

Mr. Honey—unmarried, middle-aged—had taken some months to screw himself up to the point of an experiment. Nothing but an insatiable curiosity and a very good opinion of himself would have driven him to it. If he could swallow a pill and be certain of finding himself back in the days when he was, possibly, King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the First, or some such notable man, that would be quite satisfactory. But there seemed to be a certain risk that he might select a pill which would land him back on some prehistoric prairie in the form of a two-toed jackass, or on the keel of an ancient galley in the form of a barnacle, or something wet and uncomfortable of that kind.

It was undoubtedly a risk. He wished the lama had been a little less sketchy and haphazard about things; at least, he might have dated and labeled the pills. It would have been quite simple—King; B.C. 992," for instance; or "Centurion; Early Roman." Or, if clammy incarnations had to be introduced: "Eel; 1181 A.D." or "Squid; Stone Age." Then he would know which pills to take himself, and which to set aside for editors and publishers.

However, there it was. He could take them or leave them. He might become King of Egypt for a week-end, or he might become a jellyfish for a brief period.

He took out a pill and looked at it. Was that little, ordinary-looking thing a free pass to the palaces of Cleopatra in the form of Antony, or was it the "open sesame" to a brief existence as a weevil in a ship's-biscuit on board the old Victory? Who knew?

He might find himself King John signing the Magna Charta, a galley-slave with cracked lips eating salt fish in a freezing northeasterly gale, or a sixth-century bullfrog baying the moon in an undiscovered Louisiana swamp.

He might find himself the Great Mogul or T'Chaka—Jonah, Shakespeare, Jack Sheppard, Adam, Oliver Cromwell, a dromedary, a polecat, a starving wolf, a skunk, or merely a house-fly in a spider's web.

He might even be Louis XIV, Francis Drake, William the Conqueror, Nero, or Robbie Burns— But at this stage he realized sharply the treasury of "local color" awaiting him, and without further consideration he took the pill in his mouth, washed it down with a gulp of sherry, and then, realizing what he had done—the awful risks he had taken—he tried to rise with the intention of hurrying to the nearest doctor. But a sudden dizzy faintness glued him to his chair. It was growing dark.

He heard the clock upon his mantelpiece as if far off—then all grew dark and still.

MR. HONEY woke, as it were, from deep sleep very abruptly. He was aware instantly that wherever he was, certainly it was not in his extravagantly easy-chair at home in his London flat—for he was lying at full length.

For some moments he dared not open his eyes to see whom or what he was. He could hear a faint murmur of voices, a splashing sound, and a curious bubbling. He pondered desperately, afraid to move a muscle. Was he a man or a mollusk—Charlemagne, for instance, or a mussel? It seemed to him that the air was intensely hot, and he decided, with a thrill of relief, that he was not under water, at any rate.

Was he the ass of whom the lama had spoken—browsing or basking in the sun upon a hillside? Or a swine of ancient days? Or a venomous serpent coiled in the sand of a desert? Mr. Honey shivered a little. But he did not feel coiled; on the contrary, he felt quite straight.

With a violent mental effort he shut out the crowding thoughts and apprehensions besieging his mind, cautiously raised his hand and felt himself. To his intense relief his hand closed upon a leg—his own leg, for he felt the touch of his hand.

He was a man, at any rate!

"Hooray!" gasped Mr. Honey, and opened his eyes. He shut them again instantly, dazzled, half-blinded for an instant, by the glare of the sun reflected from the sands of the desert in which he lay.

"Foreign country, evidently," muttered Mr. Honey to himself, rolled over, and opened his eyes again.

This time they fell upon a sight which explained the bubbling and splashing sounds. Some twenty yards or so away were a number of camels and of strange-looking men, all more or less busy round a pool of water which lay under a clump of palms.

"Hah! An oasis—certainly an oasis. Good!" mused Mr. Honey. "I am not a servant, at any rate, not a slave, whatever the place –and the date—may be, or I too should be cleaning camels. So far so good—"

And then his jaw dropped, as he remembered exactly what he was, where he was, and why he was there. London and the twentieth century receded in a bound to an age so monstrously, incredibly remote that Mr. Honey suddenly turned cold with terror.

Was it possible that he would ever see London again? London! Why, there wasn't any London—it wasn't built—it wasn't even thought of. Why, Babylon wasn't completed yet! Mr. Honey knew that for certain. Hadn't he just come from Babylon as fast as camels could carry him, and hadn't he noticed as he crossed the new Euphrates Bridge how well they were getting on with the work since they had discovered the new bitumen supply, and Queen Semiramis had caused her new system of bricklayers' and stonemasons' bonuses to be explained to the workers?

Yes, London was a long way off—in the future.

It was amazing to reflect that he, Hobart Honey, who lived in London and knew London by heart, should be lying here in an Assyrian oasis ages before London was thought of.

He shut his eyes again, and London—England, the twentieth century—slowly receded farther and farther from his mind, while his thoughts centered more and more upon his present position, which, contemplating it as an up-to-date Babylonian, he swiftly decided was the result of a mistake—a bad mistake. What on earth had possessed him to elope with the elderly ex-beauty, who, he knew, would arrive at the camp at any moment? He groaned slightly as he turned the thought over in his mind, and sitting up sharply, took a half-brick from his pocket and proceeded to re-read the message inscribed thereupon by the infatuated woman.

It was dated the evening before, and, as could be seen from the deeply engraved heading, was carved upon a slab of the palace stationery. The chisel of the writer had slipped in one or two places, but Mr. Honey was easily able to decipher the hieroglyphics. He read:

Behold, then, Dazzlet of Mine Eyes, this is the plan that I have designed, that we two shall fly on the wings of love unto Nineveh. I have sent forth to the Second Oasis four camels laden with my treasure, to the extent of one gold talent and a half, and my raiment also. Be thou there, Beloved, at the rising of the sun, when, while the Queen yet sleepeth, I will join thee, and so set forth together upon our journey.

Thy Rose and Perpetual Pomegranate.

—Immi.

P.S.—Please excuse scrawl, Sun of my Soul, but I am using a blunt chisel borrowed from one of the slaves, as all mine are packed.

Mr. Honey replaced the note in the pocket of his skirt, which already was sagging from the weight of a number of receipted accounts—he had settled all his bills, like an honest Babylonian, before leaving town—and gazed across the desert.

THERE was no sign of Immi yet; nor, to his relief, of any of the troops, which he knew, sooner or later, would be sent out by Queen Semiramis after them.

For as Immi was her favorite coiffeuse, or—since French was not invented then— her hairdresser, and Mr. Honey was merely a chiropodist in rather a small way in a shop in a back street behind the Temple of Belus, and consequently, by no means a suitable match for Immi, the lovers both were fully aware of the fact that long before they got even halfway to Nineveh, the Queen would have sent after them, and they would need all their luck and nerve if they were going to avoid her fleet horsemen.

Mr. Honey thought of these things seriously as befits a man contemplating death or matrimony, and he bitterly reproached himself for the ambition and avarice which had brought him to his present position. He ought to have been satisfied with the chiropody; the business had been doing moderately well, and the new sandals with brass filigree uppers, which were becoming so fashionable among the officers and Court dandies, were just the things to give a fillip to trade. He realized that now. It had been a mistake to stock the sideline in combs, brushes, chignons, curls, ringlets, and so on, which that commercial traveler from Nineveh had unloaded onto him. He ought to have kept things separate and stuck to his last; if he had not had that stock of curls on show, probably the Lady Immi would never have come into the shop in her life—she might never have set eyes on him at all.

As it was—

It was her money that had done it. A gold talent and a half was a lot of money—more than he, Obar-Unni the chiropodist, could ever hope to make. True, the lady was no longer beautiful, but she was said to have a beautiful disposition.

Immi had come into his shop to see if he had a bottle of Titian dye, a color to which the Queen had suddenly taken a violent fancy, and she had fallen in love with him at first sight. In the good old Babylonian way, she had said so frankly, freely, and without beating about the bush.

Dazzled by the notice of this Court lady, hypnotized by her gifts and the rumors of her wealth, Obar-Unni had meekly agreed with her plan of eloping to Nineveh. They would have preferred to settle down quietly in Babylon, but that was impossible. Obar-Unni was not in the same social "push" as the Lady Immi, and they knew that haughty and ambitious Queen Semiramis would never give her favorite hairdresser permission to marry a mere chiropodist who was barely able to pay his rates.

It was decided, therefore, to elope to Nineveh at Immi's expense, and there settle down quietly. In accordance with the scheme Obar-Unni had camped at the oasis overnight, and was now awaiting his betrothed.

He was not happy, and he heartily wished himself back in London or Babylon—London, for choice. For he had a presentiment that there was grave trouble coming.

However, he was too far gone to back out. Already a cloud of dust on the horizon hinted that his lady was not far. So, with a sigh, he rose, deciding to keep a stiff upper lip.

He clapped his hands sharply and an Ethiopian in white pants came running from the camels to him.

"Ho! Slave, bring me a sherbet!" he said robustly. "A good stiff one, mark ye!"

The slave cringed.

"It shall be done, Lord," he muttered; and went away toward a tent.

Mr. Honey perceived that the husband of Immi was not going to be denied his comforts and the prompt obedience of her slaves, and, with a slight access of cheeriness, turned again to watch the approaching dust-cloud on the horizon.

"After all, it mayn't be so bad if we can get well away," he mused.

"Lord!" said a low voice behind.

He turned. The slave was proffering a foaming goblet.

Mr. Honey took it and drained the goblet. His cheeriness increased as he realized that this was a very different vintage from that with which Obar-Unni was accustomed to quench his thirst..

He returned the goblet.

"Ill have another," he said in English.

"Pardon, Lord?"

"More sherbet, son of an ass!" snarled Obar-Unni, coming abruptly out of his reverie.

The slave understood that.

BUT Mr. Honey perceived that he would have to be very careful to keep his mind concentrated upon his singular position. Either he was a Babylonian or a Londoner; he could not be both. Nor would it add to his reputation for sanity if he allowed himself to behave alternately as an eloping Babylonian chiropodist and an English author.

"It must be one of the two," he said. "And as I'm in Assyria, I'd better do as the Assyrians do."

He sipped at his sherbet, and fingered the beard he wore—a square-cut, well-oiled, plaited beard that somehow struck him as being humorous.

The dust-cloud drew nearer, and Mr. Honey presently perceived that the cavalcade which raised the dust was composed entirely of horsemen plentifully bedizened with brass and amply supplied with weapons—bows and spears and swords.

There was nobody among them in the least resembling Immi, and with a thrill of apprehension, Obar-Unni recognized them as a half squadron of the Queen's Own Babylon Light Horse.*

[* Modern equivalents are used to describe the Assyrian soldiery in order to save time—the author's. —Author.]

They came down upon the oasis in the famous Assyrian "Wolf-on-the-fold" formation, and Mr. Honey had only just time to finish his sherbet before he found himself ringed round with fierce-looking, black-bearded troopers.

"Thou art Obar-Unni, the corn-cutter of Paradise Lane?" said the captain of the troop in a harsh military snarl.

Mr. Honey folded his arms, not without dignity.

"I am Obar-Unni, the chiropodist!" he said, with the accent on the last word.

The captain laughed sourly.

"Ha! Thou art my prisoner, chiropodist!" he said; and turned to a troop sergeant-major near him. "Ho, there! A horse for the prisoner!"

The sergeant saluted. "Very good, sir," he barked; and passed the order.

A led horse was brought, and Mr. Honey mounted. Two troopers ranged alongside, and the captain, having ordered two other troopers to escort the slaves and camels back, Mr. Honey and his guards set out for Babylon.

For a few moments Mr. Honey rode in silence, thinking; then, observing that his escort regarded him not unsympathetically, he asked where they were taking him.

"Where to, but before the Queen?" said one of the men. "And by the brazen gates of Babylon, corn-cutter, I do not envy thee this day!" he added.

Mr. Honey's heart sank into his sandals.

"What hath befallen the Lady Immi, who was to have come to meet me at the oasis?"

"She rode forth from the city an hour before dawn. But the Queen had slept ill by reason of an angry pain in her right foot, and she arose early. There came to her even as she arose—in but a dour mood, mark ye, corn-cutter—certain of the police crying that the bricklayers' laborers that work upon the new quays fronting the river had thrown down their tools, demanding more pay, and that they were powerfully supported by the populace. The Queen in her mercy forbore to loose us upon the mob, but instead she said that she would go forth into the city and herself do justice. She is a great Queen.

"So she prepared to issue forth—but lo! when the Lady Immi was sent for to tire the hair of the Queen she was found to be missing. So the Queen went forth with her hair undressed, and quelled the riot. Fifteen hundred bricklayers' laborers have been fed to the crocodiles this morn, corn-cutter! Great is the justice of the Queen!

"A slave of the Lady Immi, deftly tortured, confessed that his mistress had ridden forth from Babylon to meet her lover at yonder oasis and fly with him to Nineveh. So a troop was ordered forth to outride and retake her, and another troop to capture thee. So it was done. We go now to deliver thee to the justice of the Queen, and, by the foundation-stone of Babel, I do not envy thee this day, corn-cutter! How sayest thou, Bil?" he added to the trooper on the other side of Mr. Honey.

"It is even so, Nob-bi," replied Bil, briefly but significantly.

Obar-Unni was inclined to agree with them. He said no more. It was only too evident that unless what the lama had called the "power of the pill" waned very shortly, he was in for a rugged time.

TWO hours' fast riding brought them to the outskirts of the great city, which, under the hands of the vast army of workers, collected for the purpose from all parts of the empire by Queen Semiramis, seemed to be growing almost visibly.

Mr. Honey, however, was not so interested in the sight of the city as, had he been considering the matter in his London flat, he might have expected to be—for the simple reason that, as Obar-Unni, he was already quite familiar with Babylon and the stupendous building operations of the Queen, and in any case, he was not feeling interested in Babylon just then. He would have given all he possessed, and all Immi possessed as well, to be safely in Nineveh or Ascalon, or indeed, anywhere but Babylon.

The horsemen closed in about him as they thundered through the streets, and long before he had formulated any sort of scheme of defense, Mr. Honey found himself being hustled into the palace. There he was handed over to the Queen's bodyguard, two officers and four men of whom promptly conducted him towards the great hall in which the Queen was waiting to do justice upon him.

As they passed down a mighty corridor there stepped suddenly, from behind a great statue of Nimrod, a woman. She was veiled to the eyes, but Mr. Honey recognized her by a little habit of sniffing which she possessed. She was the Lady Immi.

For the first time since he had met her, thought Mr. Honey, she had something to sniff about. She glided forward and whispered swiftly to the officer in charge, who nodded.

The men, at a word, fell back a few paces, and Immi approached Mr. Honey.

"Hearken unto me, beloved," she said. "Our plans have gone astray, but there is no time to talk of that. Thou goest now before the Queen, and her mood is—not favorable unto thee. But there is hope for thee yet. The anger of the Queen is bred by the pain which she suffereth in her foot—a strange and stabbing pain. The physicians know not what causeth this pain—and they are divided in their counsels. One sayeth it is a sprain, another stated that it was a corn caused by the wearing of too tight sandals—the fool is meat for the crocodiles this half-hour! But none knoweth the true cause, pomegranate of mine eyes. I know that thou art learned in the feet, beloved—and I have come here unto thee by stealth to warn thee how thou mayest escape thy doom and come to high honor—yea, even to be Court chiropodist! Thou must inform the Queen that thou canst soothe and assuage the pain, send for thine instruments, and use all thine arts and skill to subdue the agony. That is all —forget not! I go now. Farewell, pineapple of my soul."

And she glided away.

The soldiers closed in again, and thrilling with a new hope, Mr. Honey was marched into the presence of Semiramis.

The Queen was reclining upon a great couch, strewn with tiger-skins. From the dark frown upon her brow, it was only too apparent that she was in a deadly temper, and she was of an age when bad temper was a more permanent affair than it had been in the days when King Ninus had wooed her in Ascalon. She was no longer an April-shower belle of the town—now she had developed into a January-blizzard Queen of Babylon with a touch of gout in her right foot—which, heavily swathed, rested upon a soft hassock at the side of the couch.

But nobody in that city had ever heard of gout, and naturally, therefore, nobody, not even Obar-Unni, had the remotest idea of how it should be treated. Indeed the unfortunate chiropodist had practically made up his mind that the Queen was suffering either from an ingrowing toe-nail or a sprained joint.

The sight of the Queen's frown had driven completely from his mind all recollection of his later existence in London. He was too busily concerned fighting for his existence in Babylon to worry about London just then.

HE dropped to his knees and crawled up to the Queen in his best Babylonian manner.

She surveyed him in disdainful silence for a moment; then she spoke.

"Dog, thou art doomed!" she observed tersely.

Obar-Unni made sorrowful gestures. He dared not speak, for it was not etiquette.

"I have gone forth into the city with undressed hair because of thee!" said Semiramis.

The courtiers made shocked noises, and the Queen turned on them with a snarl.

"Be silent, herd, lest I have thee baked in brass ovens!" she said.

The courtiers were extraordinarily silent.

Mr. Honey wriggled uncomfortably.

"Yet it is in my mind to spare thee, if thou are indeed so skilled in thine art of foot-healing as the Lady Immi hath claimed for thee! Arise!"

Mr. Honey arose.

"Canst thou cure angry pains in the feet?" continued Semiramis.

"It is even so, Splendor of Assyria," replied Mr. Honey humbly.

The Queen beckoned her physicians—three of them.

"Remove the swathings—tenderly, I warn thee!—that this wise man may banish my pain. And tenderly, I warn thee—lightly as down—or by the Winged Bulls of Nineveh, I will have thee flayed!"

They moved the bandages—tenderly—and Obar-Unni examined the foot. It was as complete a touch of gout as ever had visited anyone in the world.

"What sayest thou, healer?" inquired the Queen presently.

OBAR-UNNI abased himself. "The pain ariseth from the spraining of a small muscle of the toe, Brilliance of Babylon. It can be healed by mine art," he said.

The Queen's frown lightened.

"Heal, then," she said.

Obar-Unni sent for fine oil, strips of fine linen, and a vessel of the finest cold water.

He proposed first of all thoroughly to massage the foot, then rub it with oil, and finally to bind it in cold-water bandages.

He softened his hands with oil, and—first craving pardon for presuming to touch the foot—which Semiramis graciously granted—began briskly to massage the swelling!

The first rub the Queen endured, but at the second she went straight into the air with a shriek that startled half Babylon.

The first rub the Queen endured, but at the second

she went straight into the air with a shriek.

An old and diplomatic-looking physician pushed forward.

"I am assured that this is the wrong treatment!" he said firmly.

So was Queen Semiramis. Gasping for breath, she glared at the terrified chiropodist. As soon as she could speak—

"Cast me this witless mule to the crocodiles!" she hissed.

The captain of the guard came forward.

"Pardon thy slave. Queen of the World, but the crocodiles are full fed," he murmured.

"To the tigers, then!" snapped the Queen. "What matters the destination so that he reacheth it?"

Then things happened swiftly.

Mr. Honey felt himself whirled along corridors, round corners, down steps, and through tunnels, until finally a savage roaring broke upon his senses, and he perceived that he was standing at the brink of an enormous circular pit, built up of stone and iron bars.

In and about this pit prowled some fifty tigers. Evidently they knew what the arrival of the soldiers and Mr. Honey signified, for already some of them were bounding halfway up the steep sides of the pit— roaring until the slabs of stone under Mr. Honey's feet vibrated.

He felt busy hands removing his raiment, lest—he dimly heard some one say—"a good tiger be choked." And then he was urged forward.

His fascinated eyes fell upon one huge brute leaping high above the others—a colossal beast, almost black, with one white ear and a mouth that was incredibly huge.

His fascinated eyes fell upon one huge brute leaping high above the others.

It seemed to Mr. Honey that he would pitch clean into that fanged and gaping mouth—and he shut his eyes. He opened them the next instant—and found himself gazing straight at the red tongue of Peter the cat, yawning as though he would dislocate his jaw.

He opened them the next instant—and found himself gazing straight

at Peter the cat, yawning as though he would dislocate his jaw.

Mr. Honey listened. There was still a furious roaring close at hand; but it was only the sound of a passing motor-bus.

Trembling, Mr. Honey gazed about him.

Gone were the roofs and pillars and domes of Babylon, gone the towering bulk of the Temple of Belus; the soldiers and the pit of tigers were gone also. He was back in his flat in London—in the twentieth century. The "power of the pill," to quote the lama, had waned just in time to save him from the vengeance of Semiramis.

"Thank God!" muttered Mr. Honey, rising stiffly and switching on the lights. He glanced at the clock. It was striking the last chime of nine o'clock. He had been away perhaps a half second—the most crowded half-second he had ever known!

(But Mr. Honey was tempted again. Though he didn't know whether he would become a king or a crocodile, he tried another of those pellets—and the amazing result will be described in our next issue.)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.