RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Blue Book Magazine, May 1943, with "Mr. Honey Takes a Flyer in Chivalry"

Our London author with the sweet pen-name takes another magic

transmigration pill—and finds himself in trouble with the ladies again.

Whenever they saw a party coming they pulled

themselves together. Sir Baldur rode with hand

on sword-hilt. Merlin flaunted the great shield.

MR. HOBART HONEY left the office late on the fourth Christmas Eve of the War—so late that he invigorated himself all the black-out way home with the thought that he deserved all he could get during the rest of the eve in question. It was a mild spell after a snowfall (what is sometimes called a "green" Christmas), the streets were full of slush, and the air was full of fog—as was Mr. Honey by the time he reached home.

He had that day been censoring the outgoing American mail and had run into a bunch of contracts addressed to film producers in Hollywood. These mainly concerned the sale of certain film rights of the plays of a famous English playwright. Judging from the grim legal safeguards of every known variety verbosely introduced into the enormous documents, the English playwright and his merry legal men appeared to labor under the impression that the celluloid moguls of Hollywood were a kind of cross between playwright-eaters, tanks out of control, and devilfish. Hollywood's legal representatives for their part, seemed to be absolutely certain that the playwright was partly a ravening cannibal, partly a half-starved vampire, probably a born thief, and in his spare time doubtless a mad high-binder. So they protected themselves against each other accordingly—and Mr. Honey had been reading scores of pages of such protection all day, just to make sure that the whole thing was not some new and deadly form of Nazi threat against the United Nations.

It is understandable that he waded home through the slush and fog as fast as he could, ate his dinner, visited the port decanter enthusiastically and, well-established in his armchair before his fire, swallowed one of the Lama's pills as quickly as possible. He was in just the mood to return for a spell to one or other of his earlier incarnations.

His mind cleared rapidly. Whether it was because he was becoming more susceptible to the influence of the pills or whether it was just the way things were destined to be, Mr. Honey never discovered, but nowadays he slipped from his life in the Twentieth Century to that in any other incarnation with the smooth easiness of a wet eel swimming down a fast river.

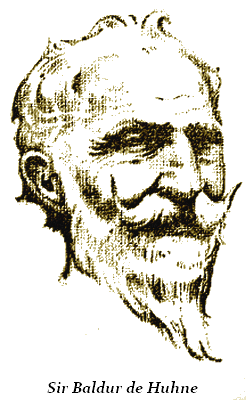

In a few seconds he was no longer the Londoner who wrote under the pen-name of Hobart Honey. On the contrary, he was revisiting an incarnation in which he was Sir Baldur de Huhne, formerly knight of the Court of the great King Arthur. He had never actually been a member of the goodly company of the Round Table—but he had been on the waiting-list. Actually he had sat at the next best—the Oval Table which was as far above the Square Table as the Round was above the Oval.

(Knights not entitled to any of these, sat on the Royal Floor.)

Sir Baldur de Huhne had long outlived these glorious days. He had been but a dashing and unprincipled youth in Arthur's day—but now Arthur and most of his knights had moved on into later, and probably better, incarnations, leaving Sir Baldur and a few others in the rear. If not an old man he was far from young, and now that knighting had largely died out as a profession he was, like the few knights remaining, finding it hard to make a living.

He was sitting in the practically unfurnished hall of his practically demolished castle, with a quart vessel of hard cider in his hand, staring thoughtfully at a few sticks smoldering in the practically burnt-out fireplace. He was incompletely sober—but the knights of his period usually were. He was not wearing his armor at the moment—that was standing in a corner supported by a post. Its mouth or visor was open, and it, too, looked incompletely sober and seemed to be leering at him in a coarsely confidential sort of way.

Sitting on his haunches before the fire was Sir Baldur's gaze-hound, Six-Leopards, gazing at his master.

But Sir Baldur de Huhne did not notice his armor or the gaze-hound. He was busy doing his accounts—in his head, for he could not write.

His calculations were not accelerated by the presence of a lady of certain age though with the remnants of great but slightly acid beauty, who sat in a ramshackle chair on the other side of the fire. She was asleep—but she was talking in her sleep. Talking pretty frankly. And when she was not talking she was constantly grinding her teeth.

Sir Baldur did not pay any attention to the sleep-talk of the lady—he got all of her conversation that he needed when she was awake. Nor did the grinding of her teeth distract him—he was always ready to admit that she had, on the whole, excellent reasons to grind them.

She was the Lady Yeolande Blanchemains Iseult Lynette de Luxe de Laine de Ruffe. She did not actually look all that but appearances are deceptive. Once she had been a Maid of Honor to Queen Guinevere but that had been a long time before. She was now chatelaine and cook-housekeeper to Sir Baldur de Huhne. She had eloped with Sir Baldur at about the time Guinevere had eloped with Lancelot—the day after Sir Baldur had all but jousted the head off Sir Roderic de Ruffe. It was at the period when King Arthur's Court was in sore need of the overhaul which it never received and it is a noticeably small exaggeration to say that knights and dames and demoiselles were eloping all over the landscape in all directions.

Several time since then the Lady Yeolande had drifted apart and drifted together again. They had stayed put this time—neither had the money to leave the other, though each had the inclination. The vast possessions once owned by Sir Baldur's ancestors had shrunk now to a few acres of poorish land and the huge castle had long been in ruins. It consisted now mainly of holes and corners. For forty years Sir Baldur had suffered from squander-mania—though he was now cured. He had nothing left to squander. The farm was not very productive, for it was badly tilled and understaffed. It was worked by two idle serfs—who were paid by results. They had produced no results recently on account of not having been paid for some earlier results.

So that the knight and his chatelaine would have been deeply ditched but for the spasmodic efforts of their servitors—an elderly person called Merlin who was outside splitting firewood while Sir Baldur was drawing up has balance sheet. Merlin also was a come-down. He dated back to the heyday of Sir Baldur and the Lady Yeolande at the Court of King Arthur. He had slithered up to the castle of the King one day, arrayed in a black bombazine dressing-gown with silver moons, stars, crescents, triangles, circles, bars and ordinary blobs all over it, red shoes curled up at the toes, and a long black beard, and announced that he was the Foremost Magician in the world.

Most people believed everything they were told in those days. The awed sentries called the captain of the guard, a fat and purple man o' the world, overfull of wine, mead, beer and ignorance, to whom the magician repeated his story. It failed utterly to impress the captain of the guard—and he said so loudly, so loudly indeed that the guard turned out (after a fashion), a crowd of troops gathered, and quite a little bevy of lovely ladies craned their charming necks over the battlements to see what was happening. Among these was Queen Guinevere who was taking a stroll up there with the King and her boyfriend Sir Lancelot.

Presumably the quick eye of the old soldier took in his august audience and he repeated his challenge to the strange self-styled magician, very noisily indeed. He evidently saw himself promoted to major before long.

"No man, magician or devil approaches the King's Grace till I am well-assured of his quality!" he declared excitedly. "Give me, therefore, a taste of this magic!"

(Afterward, it was freely acknowledged that the man was foolish to talk in this way—everybody, in those days, knew that magicians were to be treated with the utmost respect.)

Merlin faced the captain. Then he raised his right hand and drew off the glove. He pointed his finger at the captain of the guard, intending to perform some minor conjuring trick, no more. In those days the simplest conjuring trick of today was a major operation.

Merlin pointed his forefinger at the captain—and the man dropped as dead as a snipe before the gun of a good snipe-shot. Apoplexy. It had been coming to him for years.

It was Merlin's luck that it happened at that moment. He moved his arm involuntarily and half a regiment ducked out of the line of his forefinger. Pale with fear of the consequences, he threw up his arm, intending to swear that he had meant no harm to the man—and all the ladies dived back from the battlements into the arms of their lovers. Those who had no lovers just dived backward. Queen Guinevere had to put up with Lancelot's arms, as the King had tripped and missed her.

Merlin, a quick-witted bluffer (considering the times) saw how it was; he slowly pulled on his glove and concealed his fatal forefinger in the bosom of his dressing-gown.

Then he walked round the body into the castle. Every time he moved as much as his right elbow, folk ducked.

The King fortified himself with a quart of old mead and gave him a gracious reception.

His reputation was established for the next twenty years. He was made Court Magician for life—on the understanding that he kept his right forefinger unloaded in the presence of the King and Queen—and Lancelot.

But the years passed, times changed, and people got wise to Merlin...

In the end, they pitched him out. He had constantly given himself a hearty welcome and had not saved a cent. He took up the patent medicine racket and travelled the country with his celebrated cures for rheumatism and more intimate complaints in people, glanders in horses, hydrophobia in dogs, and despair in jackasses. But he was getting old and we are told that an old man's business never prospers. His didn't, anyway. In the end he was glad to take the post of odd-job man about the palace at Baliheu Castle, the residence of Sir Baldur de Huhne.

He was out in the yard while Sir Baldur figured, Lady Yeolande ground her teeth and the gaze-hound, Six-Leopards, gazed. Six-Leopards was claimed by the knight to be quite comfortably the best gaze-hound in Wessex. In a way, this was true—though good judges were in the habit of maintaining that the technique of Six-Leopards was faulty, the gaze-hound proper, they insisted, should always be on the watch or look out or, in fact, on the gaze for deer.

Six-Leopards, they agreed, gazed well but never for deer. Some said he gazed for food, some said he gazed for affection. He got very little of either, but he still went on gazing his blank, mournful, completely unintelligent gaze, usually at his master, sometimes at Sir Baldur's old falcon which, as a rule, sat on a broken spear over the mantelpiece. It was moulting. Sir Baldur never went hawking nowadays and the falcon had long ago forgotten how to hawk, anyway. It seemed to be always moulting. Once Merlin had undertaken to re-awaken the spirit of enterprise in the hawk and had taken the bird to the fields in order to let it stoop at a few fat partridges. The gaze-hound had gone with them.

But it had been failure. A covey of partridges had risen and Merlin had shouted "Heu! Heu!" and lifted the hawk high in the air so that it could stoop at them.

But the bird merely started moulting on him. Six-Leopards had gazed sadly at the hawk, the hawker and the horizon—and they had all returned to the castle, short of partridge. Perhaps it was because of a tendency of these old sporting memories to intrude on his mind that Sir Baldur's figures did not work out to show any result but sheer insolvency.

But more probably it was because with a startling suddenness the Lady Yeolande shouted in her sleep: "He shall make an honest woman of me yet!"

She made the statement so loudly and violently that she woke herself up, and drew the gazes of the startled knight, and his gaze-hound, and his moult-hawk instantly upon her.

Her rather bitter eyes fixed themselves on Sir Baldur.

"You, I meant!" she said. Evidently her dream had been vivid.

"Why, yes—if possible," he agreed. "But Yeolande, permit me to ask when I have made a dishonest woman of you? Was it in the late days of the Round Table? When you were wife to the good Irish knight Sir Roderic de Ruffe—whom I slew? Was it when you whipped me away with you into a region which you called Wonderland? I have wondered mightily about that for years—in Wonderland. I have put the question to myself these many times. I have said, 'It is for her to make an honest man of me—if she can. But she cannot!"

He utilized the cider vessel again.

"Wit ye well, Yeolande, you cannot make an honest man of me, I cannot make an honest woman of you; for we are both naturally dishonest. There was a time when I grieved for this. But I observed that my grief did not change the facts. Therefore I ceased to grieve—and concerning—"

He was rambling on when Merlin entered without any ceremony whatsoever.

"The pig is dead; the horse refuses to work; there is disease in the bee-hives, and I am well convinced that the serfs have stolen most of the oats. Thus, fair sir, there will be neither bacon nor ham, nor honey from the hives, nor a sufficiency of porridge for our winter provender!"

"The Lady Yeolande uttered a sharp exclamation of sheer dismay.

"The pig dead? What has caused him to die? What have you being doing to him? This is ruin!"

Merlin stared at her with a water-eyed dignity.

"Doing to him? Doing to him? Forsooth! What should I be doing to my winter meat but waiting upon him hand and foot these months past! But pigs do not thrive on air and water alone, and little of that! The creature died of sheer lack of enthusiasm for a life in which there was not half enough, nay, nor quarter enough, to eat!"

"Why did you not cast a spell or an enchantment upon him, so that he took a happier outlook on life?"

"Good lack, lady, I have long forgotten the difficult art of casting spells, and enchantments do not serve as a substitute for barley-meal!" said Merlin sourly. "I am no longer a working magician—I am a retired one!"

The Lady Yeolande was agitated.

"But, pardie, I cannot provide the meals in this establishment unless I get the raw material therefore. I am utterly undone!"

"Probably it is not the first time you have been utterly undone—nor I—nor Merlin. Yet we survive!" said Sir Baldur, a little muzzily.

He stared at them. "It comes to this," he stated. "I must make a foray! Other knights do!"

"A foray! 'Swounds, what kind of a foray do you think you are capable of making?" snapped Yeolande.

"I shall show you!"

He turned to Merlin. "Fill my tankard—and fill one for the Lady Yeolande—and one for yourself while you are at it!" he commanded.

"One sees why the cider sinks low in the barrel ere ever the winter is upon us!" said Yeolande sourly—but she did not refuse.

"Nay, nay, but we are in evil plight. It is no time for parsimony. We go now into conference—thou, fair Yeolande, Merlin, and I. And it is necessary to well-stimulate our brains. Therefore let us not be niggard of a couple of gallons of the acrid and belly-gripping fluid which we call cider, God wot!"

Merlin, nothing loath, forayed himself to the cellar, muttering. On the broken spear the hawk its head so sunk in between its shoulders that it looked neckless, moulted silently; the suit of rusty armor looked more intoxicated than ever; and Six-Leopards gazed vacantly at Sir Baldur.

The hound irritated the Lady Yeolande.

"Oh, sally forth into the fields and catch yourself a rabbit, imbecile!" she said.

But Six-Leopards merely twitched a shapeless, pendulous ear and shrugged a loose-jointed shoulder. He knew better than Yeolande that there was naught in the fields to eat but grass—and not much of that. The serfs had long ago devoured all the rabbits.

Sir Baldur got up and went over to look at his armor.

"Humph! Merlin must polish it—if he has any polish," he said.

"Yes, and oil the joints—if he has any oil," sneered Yeolande.

"Also, he must mend the spear! And sharpen the battle-ax!"

He stared around the room.

"Where is the battle-ax?"

"In the woodshed—where it hath served for many years!"

"Hah! It is time and overpast that we had an alteration here," said Sir Baldur.

"That is right sooth and I recommend you to make the same, for albeit so late in the day—" Yeolande began; but broke off as Merlin tottered in with a very large quantity of cider indeed.

When their brains were well stimulated, Sir Baldur spoke briskly:

"First, the horses!"

"Horses—why horses?" inquired the Lady Yeolande. "Is it your design to take Merlin?"

"I deny not that the times are woundily scant but there are some appurtenances which no knight can dispense with. A Squire to ride behind me I must have!"

"The horse will refuse to carry both you and Merlin!" said Yeolande, deliberately. "Probably he will refuse to carry even one of you—for he is becoming fanciful, querulous and crabbed in his old age."

"I will deal with the horse," said Sir Baldur. "And as for my Squire we must contrive."

He took a long soop at his cider. Then his eyes brightened.

He took a long soop at his cider.

"I have it. You shall borrow from our neighbor, Sir Maravaine le Gros, his great mule. He will deny you nothing, Yeolande—and the loan for his mule will not totally wreck his fortunes, strained, like mine, though they may be!"

"Oh, I doubt not I may contrive that!" said Yeolande carelessly. "But ere you equip the foray would it not be the better strategy to decide whither you purpose foraying—and what for?"

"That is well spoken, madam," said Merlin, wiping his beard with the back of his hand. "For wit ye well, fair sir, what shall it profit you to mount the horse and me the mule and ride forth trusting to chance? It needs a goal, a destination!"

"True, true!" Sir Baldur nodded rather irritably. "So think of a goal, an object, Merlin! I cannot think of everything!"

Merlin took it slowly—by degrees.

"This is a desperate venture," he said. "And much consideration must be given unto it. Let us begin at the beginning—only thus shall we fare smoothly unto the end. Our object, fair sir, is money."

"That is well put, Merlin," agreed Sir Baldur. "Money. Whither shall we wend to acquire it?"

"First we must ascertain where is money or treasure—and go thither."

"Right again, Merlin."

"There is the root of the problem! Point One—where is money—or treasure to be found?"

Sir Baldur nodded.

"I begin to see your line of reasoning," he said sagely. "First find out where money is—Point One. And having found out where it is then—Point Two—how shall we get it?" he proceeded.

"That is Point Three of the problem—and must be dealt with when we arrive at the place where the money is!" explained Yeolande gravely.

The Lady Yeolande drained her tankard and put it down with a crash.

"If it is your desire to see a good woman go raving mad before your eyes," she cried out, "keep on talking for a few more seconds just exactly as you are talking now! Pardie, you are like two talking crows on the bough of a dead tree in a black frost, discussing the worms asleep out of reach under a foot of frozen soil! Look you, this is no case for a flux of words—this is a case for action! I will speak plainly for time is short and the need is desperate! Upon this foray, so-called, depends the continuance of my presence here. Succeed quickly and I remain—fail and I go to a place where a good chatelaine will be appreciated at her worth—Sir Maravaine le Gros has long desired such a chatelaine to control his establishment—and I doubt it not that he will be overjoyed to—"

"You are like two crows on the bough

of a dead tree," cried Lady Yeolande.

A sudden exclamation from Merlin stopped her.

"By Excalibur, I have it! The treasure of Sir Bustyr de Fysshe!" he cried.

They stared at him.

"If, by good hap, we may once lay hands upon this treasure, then shall our griefs and troubles vanish like the morning vapors that dissolve under the rays of the rising sun!"

"I have not heard of that treasure," said Sir Baldur. "Where is it to be found and, by good fortune, won by the victor in a trial of arms? Sir Bustyr de Fysshe—de Fysshe!" he mused. "Yes, I have heard of him these many years past. Tell me Merlin, is he not a short, thick swarthy man of mine own age who bears upon his shield three dogfish argent, a catfish azure, a lobster gules and a couple of cod hooks sinister? Methinks that many years ago I ran a course with him in a tournament at Camelot and jousted him into hospital for several months!"

"That is verily the selfsame knight!" said Merlin.

Sir Baldur stood up and stretched, accompanying himself with a hiccup or two.

"Should be easy to pick a quarrel with him, as between two knights, and joust him into hospital again. Have done it once—should be able to do it again."

"You are not so young as you were nor so sober," Yeolande warned him, "—sometimes!"

He stared. "Not so sober—sometimes!" he echoed. "I can amend it! 'Swounds, unless I come down upon this man's treasure and that right soon, meseemeth I am doomed to be sober for all my days hereafter!"

He sat down again and fixed a rather wandering and watery eye on Merlin.

"Tell me more of the treasure of Sir Bustyr. Where doth he keep it? Is it locked away in deep cellar? In steel-barred cell? How is it guarded? Is it much? How do we come at it?"

But Merlin shook his head, clawing at his grizzled beard.

"Nay, fair sir, I know not. No more I know than that it hath come back to me, a memory of the past days when all the secret news of the kingdom trickled through to the King's Own Magician. The treasure of Sir Bustyr Fysshe: I seem to hear again the words in these ancient ears. By your good leave, Sir Baldur, it is in my mind that we fare forth nigh unto the City of Sarum, outside of which, I mind me, is the domain of the Fysshes. There we may abide making patient and subtle enquiry concerning the treasure. Then, when we have discovered where he keeps it hidden away—"

The Lady Yeolande broke in.

"Tarry awhile, Merlin, and make clear to my mind the following—is this an adventure of knight-errantry or is it to be an ordinary burglary?"

"Burglary!" snorted Sir Baldur. "Not so! Am I not a knight? Is it not the correct, nay, the only decent thing for me to challenge Sir Bustyr to attempt some small deed of arms upon me and when I have vanquished him to require his treasure for ransom? That is the rule to which all knights are bound, and may dogs howl on the cowardly hound that shrinks therefrom!"

Six-Leopards threw up his head and howled like a wolf till Sir Baldur smote him sore and silenced him.

"He though I was talking about him, the intelligent animal! he is very quick—he shall accompany us on this desperate adventure!"

Six-Leopards heard and crawled behind the arras—evidently not an enthusiast about desperate adventures.

For many hours and more tankards they discussed it.

In the end the knight and Merlin fell asleep.

The Lady Yeolande stood up and looked them over.

"Knight and Squire! Huh!" she said and ground her teeth a little. "Unless my mind most woundily miscarrieth I see my finish! Chatelaine to Sir Maravaine the Fat! Bah!"

She looked to see if there was any cider left, found there was not and so went to bed.

Ten days later the foray started in earnest. Compared to what a foray by Sir Baldur de Huhne had been twenty-five years before, this was little better than a fragment.

First rode Sir Baldur on the horse—an elderly, sneering, grouchy cart-horse, of no beauty whatever, whose distinguishing characteristics were bone-idleness and low cunning. Sir Baldur was wearing several parts of his armor—all of it that was not rusted out or broken. His visor would not shut but that only made him look as if he were having a hearty laugh at things in general. The feathers at the top of his mild-steel bonnet drooped a little but that was the fault of the moths. It would not be seemly to blame a knight for what the moths had done to his feathers. He rattled as he rode a good deal, but after all, armor that did not rattle was like spurs that did not jingle—frightened nobody.

The knight's personal outfit was, then, shabby but genteel—shabby-genteel, call it. He would have looked better if Merlin had used a little more metal polish on him. But they had run out of polish. Still, Sir Baldur had been a pretty hot knight in his day, and like a retired professional time-serving soldier of these days, he had not lost the hallmarks. One could tell that, though he was out of practice, well past his prime, and definitely on the down grade, he was, in a way, the genuine article. He sat upright and kept one hand quite imposingly on the sword-hilt at the top of the scabbard clanking by his side. It would have been a good guesser who guessed that there was no blade left under the hilt. The battle-ax wasn't bad considering its years of honorable service in the woodshed.

Six-Leopards, the spotted old gaze-hound, shambled alongside, looking sick of the foray already and sicker still of himself.

Riding behind, on Sir Maravaine le Gros' mule, was Merlin, looking like a fool—as he himself grumbled. He had dug up out of an amazing collection of junk which he had amassed for himself in one of the bat-haunted, belfry-like upper attics, an armoring consisting of what looked more like a tattered chain-mail shirt with the tail missing—a 'model' which had once been very popular among knights who wanted something a little more flexible than the heavier, showier, jointed and riveted armor. It did not suit the ex-magician very well, but, in a limited sort of way, it protected him from the ears down.

He carried Sir Baldur's spear and shield—the latter a triangular affair upon which was pointed a yellow bee-hive with blue bees carrying honey to it from all directions and the motto "Huhne non jam"—a bit of hideously inaccurate and ignorant Latin which obviously was intended to express the slogan "Honey, not jam!" Behind him, various more useful but less decorative articles were slung—a kettle, a pot, a stone jar and some parcels of victuals. By and large, a good big load. The mule did not seem any too satisfied about it. But then that mule never was and never had been satisfied about anything whatsoever. He was what a mule-and-ass psychiatrist would have classed as a frustrated mule—and this in spite of the fact that he usually got his way in most things for he was also a fighting mule. Also a kicking and biting one. He was a blackish-brown brindle with a totally hairless tail that looked like India-rubber. His name was Rosamund—which means Rose of the World.* By any other name he would have smelled as fragrant.

* In those days of romance they were oddly careless about the gender of the creatures they christened. —Bertram.

Sir Maravaine le Gros, who came over to see them off, and was standing at the door with the Lady Yeolande, bethought himself of an omission just as they started.

"Hey!" he shouted. "The Squire has forgotten Thunderbolt the falcon. For his dignity's sake Sir Baldur must have his falcon, man!"

"Thunderbolt cannot come upon the foray," bawled Merlin.

"Why not?"

"He's moulting!"

"Oh!" said Sir Maravaine, and said no more till they were out of sight. Then he turned—all the eighteen stone of him—to Yeolande.

"Whither go they—and why?" he asked.

"Alack, Sir Knight, the treasury of the good Sir Baldur hath dwindled low. Now he sallies forth to challenge Sir Bustyr de Fysshe to knightly combat. If it befall that he knocketh out Sir Bustyr then naught shall serve for ransom but the whole of the treasure of Sir Bustyr—of which doubtless thou hast heard rumor these many times!"

The fat knight thought.

"Yea, fair Yeolande, I have heard rumor of the treasure of Sir Bustyr. But it never occurred to me to sidle along to Sarum and take a flyer at it. Am somewhat too big-about these days, alack!"

"Yes," said Yeolande, eyeing him thoughtfully. "Indeed I fear that your embonpoint would get somewhat in the way!"

At this they both sighed.

"The times are very hard upon we knights of old!" he complained. "But there is still to be found a cup of cider—no?"

"Yes," said Yeolande, and led him to it. She glanced at him sidelong as they went.

"And wit ye well, Sir Maravaine," she said. "I, speaking for myself, I am not averse to a reasonable embonpoint in a knight. Seen in silhouette meseemeth it stabilises a man!"

For a long time the foray progressed in austere silence through a cold, heavy rain which began to fall when they were rather too far from Baliheu Castle to make it worth while turning back. Moreover it was the horse and Rose-of-the-World who felt the impact of the climate most severely. Sir Baldur was, in a sense, indoors out of the weather—so, of course, was Merlin, except that there were more leaks in Merlin's chain-mail than in Sir Baldur's armor. Both were turning bright red with rust—but neither cared. Six-Leopards walked under the horse, gazing at the mud.

But with Rosamund it was much otherwise. He mooched along under Merlin, seeming as meek and resigned as an aged cow. But he was not so. Slowly, and very gradually, as the muddy miles passed, his enormous ears left their usual angle and shaped themselves to the fiddle skull of the animal. Merlin noticed this. He also noticed that between his shanks the mule seemed to be swelling up, becoming more and more electric—like a battery on a charging bench.

"There is evil toward. It accumulates—like lightning!" muttered Merlin apprehensively—not quite knowing from whence or whereunto it was accumulating. But some subtle instinct informed him that evil was in his immediate neighbourhood.

But, in spite of these things, the general reception accorded to the foray by such of the public as were abroad in that inclement weather did much to raise the morale of the Knight (and Squire) of Baliheu.

Whenever they saw a party coming they pulled themselves together. Sir Baldur hauled on the horse's jaw till the unfortunate animal's neck curved like that of a Greek war-horse, and himself sat up in the saddle straight and stiff and rode sternly by with his hand on the sword-hilt; Merlin held the great spear pointing straight up to the sky and flaunted the great shield well to the fore—with a Huhne non jam, take-it-or-leave-it, air.

The met parties usually took one glance and hastily removed their hats (if they had any) and bowed to the ground nearly humbly enough to satisfy a stockbroker. Or else they got off the road into the ditch and bowed there. Or, if they were young and nimble, they hopped over the hedge and departed from the neighborhood at a right smart clip. Knighting—for poor knights—may have been out of fashion but there was still a great number of people who remembered the customs of the knights of King Arthur's day. After all, it was not considered servile or cowardly or wretched or small or lousy to duck into the ditch or kneel down in the mud with your hat off and apology for living written plain all over you when an iron-clad knight, probably as lousy as yourself, passed by with a battle-ax in one hand, his other hand on his sword-hilt, and a Squire with a horseload of further implements, tools and weapons behind him. It was generally held to indicate that, on the whole, you were publicly expressing your personal preference to continue living all in one piece.

This was the Age of Romance—and one had to pay close regard to one's step in those days.

They came to an inn—a humble affair, built of mud and wattle with some pigsties built of wattle and mud at the back.

Sir Baldur pulled up and read the signboard—which merely announced to all comers that the proprietor was Gulph and that he was licensed to sell "Beers, Wines and Spirits."

Sir Baldur broke a window* and the innkeeper ejected himself from the inn, bowing about two-thirds flat to the ground.

* Not glass, in those days, of course, but the thin skin of some creature's intestines stretched to the point of transparency. We use it for sausages nowadays.—Bertram.

"Varlet, what hast thou in thine hovel fit to serve to the most goodly knight in all Christendom—none less, God wot, than the great Sir Baldur of Baliheu!"

"Beers, wines and spirits, may it please Your Grace!" babbled the innkeeper, apparently half paralysed.

"Set them forth, set them forth—one double order of beers, wine and spirits!" bawled Merlin, as good a Squire as one could require. "And haste thee, haste thee, varlet, lest a goodly knight, weary from sore conflict with the cannibal infidel on thy sotted behoof, should parch him this day!"

"Now, Heaven forbid!" croaked the innkeeper—and set them forth.

The beers were flat; the wines were acid; and the spirits were low to the point of melancholia. The foray consumed them, discussing their plans, and rode on. Nobody hit the innkeeper. This appeared to be regarded by all, including the innkeeper, as payment generous to the point of over-tipping.

The next people they met (in a way) were two small-business thieves. They saw the thieves lurking in the rain by a gallows-tree about two hundred yards ahead.

When they reached the gallows-tree there were no thieves there. There were two black dots far across the fields that looked like two crows flying rather rapidly over the furrows...

Next they ran full tilt into a knight in black armor, evidently out on strict business.

Six-Leopards left them temporarily—he was rather afraid of dark knights.

They halted face-on and studied the heraldry on each other's shields as these were advanced by the Squires.

Sir Baldur did not know the first three letters of the alphabet but he understood heraldry. The dark knight's shield was jet black and upon it was painted two wickets silver, three skillets blue, four mullets red, five gullets pink and a watermelon gold, the whole surrounded by a fesse dancette.

"It is not possible!" said Sir Baldur. "This knight is an illusion!" He passed on.

"No, sah! I's no illusion—but Ah suah am glad to be on mah way!" said the dark knight, and passed on also. Foreigner, evidently.

Both seemed glad to pass.

Six-Leopards rejoined them—hind foremost out of a drain into which he had taken a look.

Then, gradually leaving behind them the wolf-haunted wastelands, the dark forests wherein things rustled and squealed and outlaws prowled like leopards, they passed through a region where the slovenly fields showed signs of a rude tillage, improving as they progressed.

The farther they went, the greater the improvement, till suddenly, when the afternoon was well-advanced, they perceived that they were in a fair land.

At the top of a steep hill, Sir Baldur suddenly stopped the horse and gazed out over a region of corn and cows, of sheep and fat hogs rooting, lost in genuine admiration.

"Now, by Excalibur, here is a land of which these eyes have never seen the like!" he exclaimed.

Merlin muttered agreement.

"We draw nigh unto Sarum," he said. "This is that land enriched by the Treasure of Sir Bustyr de Fysshe. No man but a master of treasure unlimited could so conquer and subdue the savage soil of our land, Sir Knight!"

The rain swept clear across the land, the last great shadows of the cloud swung off the corn as they stared, and the sun illumined the whole lovely green and golden countryside.

Sir Baldur, thinking of his own starved acres, sighed.

"Yes—treasure is needed for this!" he said. "Capital—no man may so transform the face of this uncouth earth, lacking capital!"

They turned into a track which took them along the side of a field in which a serf was working. This person, peremptorily questioned, told Sir Baldur that he was indeed upon the lands of Sir Bustyr de Fysshe, and with a boldness very unusual in a serf, added in a very obsequious tone indeed, that Sir Bustyr was a very great knight with but once slight prejudice—namely, a dislike amounting almost to a horror of having strangers riding over his land.

"That might be well for the common folk," said Merlin haughtily. "It is not intended to apply to so mighty a Knight as my master!"

A vast voice from behind promptly corrected him.

"Art wrong!" it bawled. "The prejudice is especially directed against such as thou and the Knight thou art squiring from the back of thine evil-smelling mule. We want no strange Knights and Squires hanging around the fields. Quit them therefore and that right soon, lest an ill thing befall thee!"

It was a short, broad swarthy man with a rather uneasily hectoring manner. There was a curious quality of sham or imitation fury about the general delivery of this abrupt invitation to quit. It was almost as if his wife were listening to him, having first set him at strangers.

"That, fair sir, is but a churlish fashion of address to the noble and distinguished Knight—" began Merlin. But he was promptly interrupted.

"Knight! Knight! We need no Knights loose in this parish—especially so-called noble and distinguished ones. Better the crows—they come less expensive about the place. This is a farm and a good and a great one and we have no time for foolery. Therefore, get off the farm!"

The foray hesitated.

"Knight! Knight!" continued the man. "They are behind and far behind the times! Good lack, these useless iron-clads but encumber the face of the fair earth. I, too, was once a Knight in the days ere I was instructed in the error of my ways. Hast never heard of the great Sir Bustyr de Fysshe—he who overthrew and brake and smote forty-seven knights on an afternoon at the tourna—"

But here he seemed to catch a sound from the little wood behind him, and changed his tone abruptly.

"Get off this land. I charge thee—and now—forthwith! Thou, in the ancient iron suit—and particularly thou on the mule!"

He rushed forward raising his agricultural-style cudgel, a severe-ish looking bat to use for the simple purpose of mule-starting. He brought the cudgel into contact with the mule in no half-hearted fashion—an error in tactics.

All day long Rosamund, notoriously the most evil-tempered mule in Wessex, had been stewing and steaming up his amperage, and he was just about fully charged when Sir Bustyr, the knight turned farmer, made contact with his club.

It was all over in a matter of seconds. Rosamund slewed half round in a peculiar, writhing motion, and Merlin departed from the saddle in an involuntary hurry. Then, freed of his load, the mule whirled on Sir Bustyr, and with uncanny speed and absolutely fatal precision kicked the blustering farmer clean out of this incarnation before the man could possibly have realized that he had cudgeled the most dangerous member of the foray he could have selected. He had intended to start Rosamund off his land—instead he had automatically started himself on a new incarnation.

The serf rushed up with a spade, but Rosamund whirled on one hind-leg to face him and the serf halted his direction, changed gear up and headed for the horizon, leaping everything that got in his way.

Sir Baldur clanked off the horse and helped Merlin up. Then he took a look at Sir Bustyr.

Merlin shook his head.

"Fair sir, he hath been in Valhalla these five minutes!"

He was pale.

"Little I dreamed what I have this day bestridden. I have been riding a catastrophe—not a mule! Thus ends our quest for the treasure of the late Sir Bustyr even ere it be well-started!"

"Be not so sure thou speakest that which is sooth!" said a grim voice behind them. They turned quickly to see, striding from the little path beside the wood, a lady.

She was of middle-age and she looked, talked and acted like a strong and steely man.

She stood there studying them for many minutes. Her hard eyes took them in from head to foot and back again.

"Yes, it is even as the innkeeper sent word! 'Fore God, ye are, of all the knights and squires in Christendom, the very lousiest I have set eyes upon. Thou, Sir Knight, art the rustiest thing in armor I have seen these many years—come out of it ere thou rustest completely up!" her glare swept on to Merlin. "And as for thee, thou poor depraved wretch, thou hast no tail to thy shirt! ... Nay, bandy no words with me, nor proffer me lies. I have had word of ye and of the purpose for which ye came. Ye spoke too freely of your evil plans at the inn and all your works have been reported to me, the mistress of these fertile domains. Deny it not—ye came here to win away the treasure of Sir Bustyr de Fysshe! Look around these fat and profitable lands, upon the flocks and herds, the corn! And know that I, the chatelaine of Sir Bustyr,—who, poor man, was as ignorant of the art of husbandry as doubtless thou art,—I transformed his starved and untilled lands into this. I—the Lady Violente la Sterne—I, who for that reason and for none other, am known far and wide as the Treasure of Sir Bustyr de Fysshe! And I am not yet buried treasure, wit ye well, Sir Knight!"

"Thou hast no tail to thy shirt!"

She laughed harshly.

"Now Sir Bustyr has left me lone—aye, I saw it all. An accident—no need to protest—I saw all. Had he but been a better judge of a mule he would never have approached that wild animal. Yet it is thy fault, Sir Knight, that I am bereft of an obedient and docile friend for whom I have managed these many years, and whose estate I now inherit. Now, I am minded to hand ye both over to the king's troops who are encamped beyond yonder hill under command of mine own blood cousin—short shrift for treasure stealers have they—if suitably rewarded! ... But I am a merciful woman—I will first see thee, Sir Knight."

She turned to Merlin.

"Get him out of that armor and right quickly!"

There was a rasp in her voice that made Merlin jump. Reluctantly, Sir Baldur moved to comply—albeit rather stiffly—and after sore trouble Merlin got most of his metal off him.

The Treasure of Sir Bustyr looked him well over.

He was not so young as he had been but, for his age, he was not a bad-looking old blackguard.

Her hard face softened just a shade as she studied him.

He twirled his mustache at her.

"Thy name, Sir Knight?"

"Sir Baldur de Huhne of Baliheu!"

"Art wed, Sir Baldur?"

He bowed deeply. "Nay—a single man, oh, Lady Violente!"

"Hast means, Sir Baldur?"

"No means, madam, beyond my horse, my hound, my hawk and a ruined castle! I stand alone!"

"I, too," she said. "Thy coming has bereft me of mine only friend!"

He stared.

"Well?" the Lady Violente asked impatiently. "Art thou a chivalrous knight—or not... Am I, the Treasure of Sir Bustyr, to live the rest of my life alone? Why camest thou here? Art not so bright as I thought thee, Sir Baldur! In plain English, what art thou going to do about it?"

"Well?" the Lady Violente asked impatiently. "Art thou a

chivalrous knight—or not... Why camest thou here, Sir Baldur?"

He looked at her, thought of the troops over the hill, and reflected swiftly. He had forayed all the way from Baliheu for the Treasure—here she was before him. A little masterful and undoubtedly a strict, even severe lady. A knight would have to watch his step—there would be only one boss about the place if he stepped into the shoes of the unfortunate Sir Bustyr—and it would not be Baldur.

Still—she was inviting him to marry her—a woman of quick decisions and one who knew her own mind.

He did not hesitate. There was no way out even if he did hesitate.

"Nay, but it were over-bold, Violente—" he began.

"I like a man to be bold—sometimes," she said. "At other times he need be but obedient and docile and interfere not with the farm—Baldur!"

He dropped on his knees and proposed to the Treasure in true knightly style.

He was accepted. (Just as well for him—for, he learned later, the Lady Yeolande had already left Baliheu for good with Sir Maravaine.)

"Thy Squire—dost need him, Baldur? I like him not—he hath a hang-dog look," remarked the Treasure.

"Wilt abide with me, Merlin—or wouldst prefer that I give thee Baliheu and all within it? I do not return—nor do I need it now!" said Sir Baldur, who already had a shrewd idea that Yeolande had taken care of herself.

Merlin did not take long to make up his mind. He had made but a very moderate hit with the Lady Violente and knew it.

"A knightly gift, fair Sir Baldur—accepted in the spirit in which it is proffered. Doubtless I can make me a living out of it!"

"Mayest have the horse also, Merlin!"

"Now God be praised for that, Sir Baldur—I had walked back else, for never will I again bestride yonder catastrophe."

"Well said! So ends as goodly a venture as ever knight launched upon. Farewell, Merlin!" said Sir Baldur, and turned to the new life—and his new wife.

"Short and sharp—but that is the way of it nowadays, my love," said Violente, who had been issuing orders to a gathering of serfs concerning the late Sir Bustyr. "Come then—home!"

She spoke truly, for a few seconds later Mr. Honey was back at home—but in his London flat. Once more the Lama's pill had shorted on him just when a new life loomed before him.

He took off a port, thoughtfully.

"Not quite the quality of knight I might have been," he said at last. "But doubtless there were worse ones."

He refilled his glass.

"If possible," he added.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.