RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

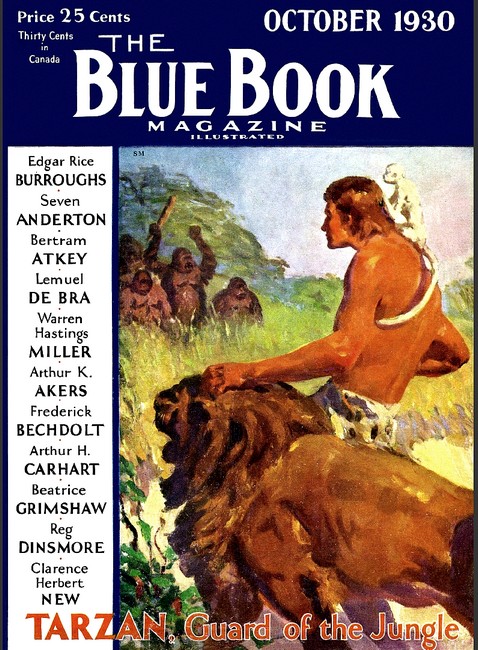

The Blue Book Magazine, October 1930, with "The Fifth of November"

Wherein a modern gentleman miraculously leaps back

across the ages to become none other than—Guy Fawkes!

WHILE traveling in India Mr. Hobart Honey of London happened to save the life of an important Tibetan lama; and in gratitude the reverend gentleman bestowed upon him a remarkable gift—namely, a bottle, itself a rare and most valuable example of Chinese glassware, containing certain pellets possessing the singular power of temporarily reinstating the swallower of any one of them in one of his previous existences.

Mr. Honey—unmarried, middle-aged—had taken some months to screw himself up to the point of an experiment. Nothing but an insatiable curiosity and a very good opinion of himself would have driven him to it. If he could swallow a pill and be certain of finding himself back in the days when he was, possibly, King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the First, or some such notable man, that would be quite satisfactory. But there seemed to be a certain risk that he might select a pill which would land him back on some prehistoric prairie in the form of a two-toed jackass, or on the keel of an ancient galley in the form of a barnacle, or something wet and uncomfortable of that kind.

At length Mr. Honey made the experiment—and found himself the court chiropodist to Queen Semiramis! He had a hard time in Babylon, and rejoiced when it was over; but curiosity drove him to further ventures—in which he found himself, successively, a singularly miserable cave-man, an unsuccessful and sorely bedeviled pirate, an anthropoid ape condemned to fight a lion in a Roman amphitheater, a charcoal-burner who happened to save the life of William the Conqueror, and the private assassin in the service of Queen Cleopatra.

MR. HOBART HONEY had made an alarming discovery. Namely, that he was a pill-slave, or a pill-fiend—a victim, that is to say, of the vice of taking pills. Not, of course, the usual variety, but those extraordinary pellets presented to him by the lama.

He made his discovery some three days after his arrival at Rye, whither, it will be remembered, he had rushed for a month's golf, in hope that the trench-digging involved thereby would help to efface the bitter memory of his impalement by order of the Roman noble Tullius Superbus, at the request of Cleopatra's Antony. Hitherto his experience had been that golf was the grand panacea for all ills, whether mental or physical. But on the evening of his third day at Rye he felt that Rye was dull, and golf still duller. There was no vim, no snap in life at Rye. It was too tame, insipid, dead-and-alive. There had been a time when to do one of the short holes in a scrambling three had raised his spirits to the zenith of human delight, and had caused him to feel for the remainder of the day so light-hearted and happy that he might have been wearing upon his neck a new-laid balloon filled with laughing-gas, instead of an ordinary bone head.

But that was a thing of the past. What conceivable pleasure could holing in three strokes a small warty ball of foolish, expressionless appearance possess for a man who had once been private assassin to Queen Cleopatra? None, obviously.

Mr. Honey was quite frank with himself. His craving for further adventures in the guilfs of the by-gone was not to be slaked with mere golf. And he did not attempt so to slake it. He had something like two hundred and forty pills left, and in his heart he knew now that he would never be satisfied until he had used the last of those pills.

He did not hesitate; he merely packed his bag, paid his bill, and when the next up-train to town pulled out of the station Hobart Honey was aboard it, looking forward to his next pill with something of the rabid eagerness of a "coke-sniffer" looking forward to his next sniff.

By nine o'clock that evening Mr. Honey was sitting comfortably in his study with the pill-bottle in his hand a glass of sherry at his elbow, and Peter, his white-eared black cat, on the hearth-rug before him.

The author did not linger. There was nothing to linger for, and he would not be delaying his work, for in any case he would lose no time. That was the one great advantage the pills possessed. If he swallowed one and "went off" at nine, he "came to" again at nine. The time used up on any adventure in any reincarnation was time which belonged to the period of that adventure, and consequently was time which Mr. Honey could very well spare. It belonged to some other existence. This was very satisfactory.

Rather wistfully expressing a sotto-voce desire to awake as a person of some importance, Mr. Honey swallowed a pill, and as usual, leaned restfully back. He had an odd fancy as he leaned back that the electric light on his table suddenly went out—probably the filament had parted, he thought—so, not wishing to find himself in the dark when he returned to the Twentieth Century, he rose with the intention of switching on one of the others.

HE barked his shin rather abruptly against something that felt like the edge of a cask, and then perceived that he need not bother any more about the electric light. He seemed to be getting on very nicely with a lanthorn which he appeared to be holding.

He glanced round, still a little dizzy from the swift transition from one existence to another[*], and perceived that he was standing in a cellar. It was in complete darkness save for the feeble light of his lanthorn, which nevertheless was sufficient to give him an excellent idea of the contents of the cellar—mostly casks and dry wood.

[* The pills were very quick in their work. Mr. Honey never got used to the swift change. It always made him feel rather like a conjurer's rabbit. —Author.]

"Clearly," mused Mr. Honey, "I am in some one's beer and firewood cellar! I wonder whom it belongs to?"

He had not to wonder very long. Almost immediately he experienced that curious mental handspring which invariably followed each of his transitions. The Twentieth Century, as usual, slid away into the mists of the future, leaving him with merely a dim memory of it, and at the same instant he knew who he was.

He had hoped to prove a person of some importance. Although he was hardly that, certainly he had become a gentleman who was hoping to make some little noise in the world, being indeed none other than Mr. Guido Faukes—or, as we of today prefer it, Guy Fawkes, recently of the Spanish Army in Flanders, but now engaged in carrying out a contract which he had recently made with a gentleman named Mr. Robert Catesby.

Resting tranquilly upon a barrel containing perhaps as much as a couple of hundredweight or so of gunpowder, he was quietly thinking things over. He had been very highly recommended to Mr. Catesby and that individual's friends, and he was anxious not to disappoint them, especially as he knew that practically all Mr. Catesby's future domestic happiness depended upon him. Puffing reflectively at his pipe—a clay churchwarden, broken off short—Mr. Honey, or perhaps one should say Mr. Fawkes, allowed his mind to roam back to his original interview with Catesby.

"Let me put the thing to you quite clearly, Mr. Fawkes," Catesby had said frankly—though in rather more out-of-date phraseology. "I have heard, upon good authority, that under your military exterior you are a very sentimental man, and it is for that reason that I have urged my fellow-conspirators to acquiesce in the selection of yourself as the ideal man to carry out our little—er—enterprise. Briefly, then, the situation is as follows: I am deeply in love with a lady whose name you, as a gentleman, will not expect me—also a gentleman, Mr. Fawkes—to mention. Suffice it to say that she is very rich, and that the portrait of her, recently painted by a rising painter, depicts a by no means bad-looking woman, broadly speaking. I have asked her hand in marriage, Mr. Fawkes, and she has been so gracious as to bestow it upon me, upon one condition—upon one condition."

"What is the condition?" asked the sentimental Mr. Fawkes.

"Briefly, my dear sir, it is that I must become a member of Parliament. She has a passion for members of Parliament. Odd, isn't it?"

"Very," agreed Mr. Fawkes, who, like the large majority of military men, had no use whatever for members of Parliament.

"The position is a little difficult," resumed Catesby. "You see, there are no vacancies in Parliament at the moment."

"They can, however, be created, I imagine," suggested Guy Fawkes. Catesby smiled.

"Yes, indeed; we are coming to that in a moment," he replied. "There are at present no vacancies, nor does any member seem likely to relinquish his seat; nor—the present Government being apparently screwed down—are there any signs of there being a general election. So you see the difficulty I am in?"

"Yes," said Guy Fawkes, "I do. The Government won't rise."

"Well, yes—in a way, that is it," said Catesby. Guy stroked his chin.

"And you want me to give them a rise, Mr. Catesby? Is that the idea?" he inquired. "Exactly."

"Nothing easier," said Mr. Fawkes, "to an old soldier. Now, about the price—It will be an expensive matter to do it really well."

Catesby held up his hand.

"Don't let money hinder you, my dear Guy—for so, I trust I may call you. Don't give the expense a thought. My friend Sir Thomas Percy has already rented a house adjoining the Parliament House, and I have plenty of other rich friends, though personally I happen to be a little—er—short. But the money is there. Let me see, now—"

And the conversation had become strictly businesslike.

IT was of these things that Mr. Honey, as Guy Fawkes, found himself thinking as he quietly puffed his pipe in the cool seclusion of the cellar. He sympathized heartily with Catesby—the more so since his own love-affairs were in a somewhat similar state as those of his principal.

He too loved a lady—a buxom and experienced widow, named Maynechants—who though she had by no means declined him, had made it a condition of her acceptance of him that he should be, if not rich, at least well-to-do.

She liked him very much, she had said, but she was a practical woman, and she had conveyed to him that she had another offer under consideration. This offer was from no less a person than the editor of a weekly newspaper, the Sunday News-Wallet, which had recently been established and was about to "turn the corner."

"He will then be a wealthy man, Mr. Fawkes," she had said. "And though I confess to you that he has not so high a place in my affections as yourself, at the same time a woman, in these parlous times, must be practical."

With a sigh, Guy had admitted that she was right, and merely asking her to wait a little before deciding, had thrown himself heart and soul into the task of giving the limpet-like Government such a "rise" as would assure ample room for a seat in the next Parliament, and cause him, in common decency, to add a handsome douceur to the arranged fee. He was determined to stand at nothing in his effort to win the hand of Mrs. Maynechants. He had very little fear in the rivalry of Master James Pincheparr, the editor; for, like many a dashing old soldier, Guy firmly believed that buxom widows with comfortable incomes were meant by Nature for the military, not for the press. Nevertheless, he cherished a hope that Pincheparr might be in the reporters' gallery at about six-thirty two evenings hence....

His reflections were disturbed by the entry of a stout, anxious-looking man bowed down under the weight of a small sack of gunpowder. This was a person named Thomas Bates, a manservant of Mr. Catesby, lent for the occasion to Guy Fawkes.

"Ha, Thomas, my lad, there you are!" said Guy. "What's that—the last sack?"

"There's one more to come, sir," said Bates.

Fawkes nodded cheerfully.

"Good lad! Prithee, clip into it and bring it down—and then we'll close up for tonight."

"Very good, sir," replied the perspiring Bates; and hurried out, while Mr. Honey carefully put away his pipe, and inserting a big funnel in the bung-hole of the cask on which he had been sitting, proceeded to pour the sack of powder into the cask.

He then sounded it with a cane.

"It will just about take one more sack, and leave a fistful over for the touch-hole," he said, and yawned. "I'll lay the trains tomorrow, I think. We've had 3 busy day, and I consider that we've well earned an honest stoup or two of ale."

Bates reappeared with the last sack, which he deposited for Guy's handling, and was given a few hours off, which he promptly took. He was not so keen on handling gunpowder as the more experienced Fawkes.

Unlike the agitated Bates, Mr. Honey lingered, putting a few last loving touches to his preparations, and it was while he lingered that the incident occurred which set in train the series of events which undoubtedly saved Parliament—or at any rate, a goodly portion thereof.

He was taking a last look round, when suddenly an extraordinary scrambling, thudding sound—as of a person falling or sliding down the steps leading to the cellar—broke upon the silence.

Mr. Honey looked up with a startled oath, just in time to witness the arrival at the bottom of the steps of an individual, who struck the floor on an elbow, an ear, and the small of his back. Evidently he had fallen.

"How now?" snarled Guy, hastily snatching up a bung-starter.

"How do?" croaked the person feebly—or words to that effect—sitting up and staring rather dazedly about him. He seemed to have broken no bones, for he rose laboriously to his feet.

Mr. Honey held his lanthorn high, so that its light fell full upon the man, revealing a very threadbare, wild-haired, slightly intoxicated person, who looked as though he might be a newspaper reporter "on space."[*]

[* "On space," a technical term which, loosely, may be interpreted as meaning that a reporter is not paid a regular salary, but—like a short-story writer—is paid only for such of his work as is used by his editor. Plenty of mediocre reporters have starved "on space." Plenty more will. It has its advantages, nevertheless, one of which is that these reporters are very rarely bothered by the necessity of superintending their investments.—Author.]

The newcomer was a palish, haggard person, but not without a gleam of humor in his somewhat hard-boiled eye.

"Who are you?" snapped Mr. Guy Honey-Fawkes. "What do you want? How came you here?" He menaced the man with the bung-starter. "Very simmle—simple—matter," replied the reporter. "Qui' easy to explain—one gentleman to'nother. Simmle matter—hic."

He smiled wanly and swiftly added "jacet" to the hiccough. "Hic jacet—practically speaking! Good idea, sir—to add a little Latin to a little hiccup—prevents misunderstanding. Lemme—let me, that is—explain." He appeared to pull himself together. "I am a reporter—er—unattached—but with the prospect of a salaried opening on that great weekly the Sunday News-Wallet. On my way to the offices of that paper this evening I suddenly discovered that I was being pursued by bailiffs representing several of my more importunate creditors. I began to run, but was being rapidly overhauled, when, passing this house, I perceived a person—a manservant, I imagine—in the act of leaving the house.

"He perceived me running furiously: 'What's the matter?' he asked in a rather agitated manner. 'They're coming!' I gasped; and to my amazement the fellow, with an ejaculation of terror, promptly took to his heels and vanished at a gallop down the street, leaving the door open.

I nipped inside, in the hope that the bailiffs would pursue the man instead of myself. Groping in the darkness of the ground floor, I tripped over a rug and crashed against a door, which yielded, precipitating me swiftly down a flight of steps ending near the entry to this cellar. That, sir, is the true circumstantial account of the misfortunes which led to my somewhat abrupt appearance before you."

He finished, smiling, and permitted himself to glance at the contents of the cellar, with the gaze of a reporter who is keenly on the lookout for anything worth having. Unseen by Mr. Honey, a sudden change flitted over his face as his eyes fell upon the gunpowder piled round the bung-hole of the cask nearest to him, but he made no remark upon what he saw.

"And now, sir, if you will pardon an intrusion which nothing but the direst need could have induced me to inflict upon you, I will proceed upon my way."

Mr. Honey-Fawkes hesitated. Should he let the man go or should he bung-start him? If he had guessed the contents of the cellar the risk of letting him go free was tremendous. On the other hand, if he felled him, and failed to make a clean job of it, there would certainly follow such an outcry as might attract the attention of those in the House of Parliament, immediately overhead, and lead to investigation. That, of course, would mean instant ruin.

Mr. Honey made up his mind.

"Very well; you may go," he said. "I am glad to have been of service, though you have seriously inconvenienced me in my task of taking an inventory of the wine in this cellar. But I understand. Say no more, my dear sir, say no more."

And taking the reporter by the arm, he guided him upstairs and out into the street, returning to curse the bolting Bates.

"The dolt might have ruined the whole affair," he snarled, fetching himself a stoup of ale, and filling his pipe as he settled down to muse over how the affair was progressing. "I wonder if that half-soused ruffian noticed anything? I think not—though it makes one uneasy!"

But he would have been considerably uneasier if he could have seen whither, and to whom, the reporter, now quite sober and with rather startled eyes, promptly made his way upon leaving the house. For it was straight to the office of the Sunday News-Wallet and the editor thereof, Master James Pincheparr, that the space-man went.

"Chief," said he, in thrilling tones, "do you want the biggest scoop in the whole history of the press? Because if you do, I've got it!"

"Bah!" snarled Master Pincheparr, who was experienced in scoops and rumors of scoops. "What is it?"

There was weary disbelief in his voice; nevertheless, he cocked an inquiring eye at the space-man, for it had not escaped his attention that the fellow was unusually sober.

The reporter, with his eyes starting out of his head, slipped a clove into his mouth, leaned forward, and began to whisper to the editor.

An hour later the sentimental Mr. Guy Fawkes-Honey, sitting cozily over his third stoup, dreaming of the attractive Mrs. Maynechants, was disturbed by a violent knocking upon the front door.

The agile and speedy Bates not having returned, and there being, for obvious reasons, no other servants in the house, Guy finished his stoup, slung his sword round into a handy position, loosened his dagger, slipped a pistol in his pocket, and proceeded truculently to the door.

"What d'ye want?" he demanded of the heavily cloaked, slouch-hatted person waiting on the doorstep.

"A word with you, Mr. Fawkes." was the muffled reply.

Guy peered under the slouch hat.

"Why, Master Pincheparr!" he exclaimed in surprise; for his rival was quite the last man he expected to call.

Affecting a friendliness he was very far from feeling, he invited the editor in. He decided Pincheparr could only wish to discuss matters touching upon Mrs. Maynechants, and was curious to know what the editor had to say.

"Surely, surely! Enter and drink a stoup or two, good Master Pincheparr," he continued, with a cordiality he was far from feeling. "Mayhap it will enliven the leading article in the News-Wallet somewhat," he added jokingly.

Pincheparr, a smallish person with wiry red whiskers, a tenacious chin, and sharp eyes, did so—looking curiously meanwhile at Mr. Honey.

"Hah! Say you so, good Master Fawkes? Believe me, I am anticipating shortly a big jump in circulation, to say naught of the increased advertisement revenue which will accrue therefrom," replied the editor as he followed Fawkes into the dining-room.

For a few moments he chatted on unimportant matters, then abruptly came to the point.

"Tell me, good Master Fawkes, how fares your suit for the hand of that sweet lady, Mrs. Maynechants?" he asked rather anxiously.

"Right willingly," said Guy, only too glad to seize this chance of convincing his rival that he—Pincheparr—was quite hopelessly out of the running. "Right willingly. The lady has accepted me, and in three days' time the news will be published, though not in the News-Wallet, I'll warrant. I ought not to reveal our sweet secret, but I never cared to see anyone suffer, for I am a very tender-hearted man—and it seems to me to be kindest to put you out of your misery, good Master Pincheparr. Mayhap you will be my best man."

It was quite untrue—lamentably so—but this was much too good an opportunity of discouraging the matrimonial ambitions of Pincheparr to be neglected for sake of a falsehood or so.

But the statement had an effect upon Mr. Pincheparr which was somewhat different from that which the tenderhearted gunpowder expert had anticipated. The editor, it is true, seemed to believe it. But also he unmistakably resented it.

He flushed so darkly that his red whiskers seemed almost pink against the flamed background of his face.

"Hah!" he gasped. "Say you so, you Flanders cut-purse!" He was shaking with rage. "Well, let me tell you that you talk too soon! Best man, eh? By Caxton, you've over-reached yourself this time, Mr. Guy Fawkes! You've fallen foul of the wrong man! Listen to me!"

Mr. Honey hitched his dagger into a slightly more convenient position. "I am listening," he said. "Read that," said Pincheparr. "And sign it."

Guy read it. It was a formal renunciation of the hand of Mrs. Maynechants, and an admission that he already possessed a wife in Flanders.

"You see, I've been making a few inquiries about you," sneered Pincheparr. "How many wives d'ye want, anyway?"

"That is a lie!" said Guy coolly. "I am not a married man, and I refuse emphatically to sign."

Mr. Pincheparr nodded, and took out a larger sheet of paper with the air—very natural in a newspaper editor—of one whose proved and trustworthy weapons are pieces of paper. He unfolded it, and it proved to be an enormous poster, upon which the ink was still clammy.

"Refuse, eh?" he said sardonically. "Well, read that—it is the poster for next Sunday's issue."

Guy Fawkes-Honey read. And the whole of his complex internal mechanism seemed to throw a somersault as he read as follows:

TERRIBLE PLOT TO BLOW UP PARLIAMENT

Assassin Found in Cellar Under Palace of

Westminster, Surrounded by Tons or Gunpowder

AMAZING CRIME! HORRIBLE DETAILS

Full Exclusive Story Illustrated with Special Woodcuts in

THE SUNDAY NEWS-WALLET.

"How's that?" hissed Master Pincheparr to the completely dumbfounded Fawkes. "D'ye deny that? That bill is going to give the bill-posters a full sixteen-hour day tomorrow!"

Guy believed him, but he was too petrified to say so. So stunned was he at the unexpectedness of it, that it never occurred to him to question why Pincheparr bad troubled to come round and interview him when it would have been simpler, and would have cleared his way to winning Mrs. Maynechants equally well, to have quietly informed the authorities.

Had Mr. Honey been in a state to think it over quietly for a moment, he would have realized that Pincheparr was "bluffing" him, that the editor had not really credited the reporter's story of his chance discovery, but had had the poster set up especially with a view to startling his rival into making an admission which would help corroborate the reporter's incredible story.

And he had nearly succeeded—indeed, he might have quite succeeded, had not Fawkes swiftly pulled himself together, leaped to his feet, and with extraordinary deftness daggered the editor as he sat.

Master Pincheparr slid gently out of his chair without even a groan.

For a moment Mr. Honey surveyed his handiwork. Then, with furious energy, he fell to work to conceal all traces of it. He lifted the body, and disappeared down the steps leading to the cellar, where he purposed hiding it.

As he disappeared a face peered out from behind a huge carved oak settle in the hall; it was the face of the reporter, who evidently had followed Mr. Pincheparr into the house, and remained hidden in the hall within call of his chief—uselessly, as far as the unfortunate Pincheparr was concerned.

For a moment the reporter stared white-faced, down the flight of cellar steps; then he turned and left the house as swiftly as his feet could carry him.

He hung in an agony of indecision outside the door for a few seconds. Should he inform the watch, or should he hasten with news of the now augmented "scoop" to the editor of a rival newspaper from whom he occasionally obtained an assignment or order?

Then his better nature reasserted itself, and he hurried away to give the alarm first.

Well, within the next twenty minutes Guy Fawkes-Honey, having carefully deposited the body of Pincheparr in the cellar among the powder-casks and collected his papers, walked swiftly from the house—whither he purposed never to return.

But he was too late. He walked straight into the arms of a powerful body of men awaiting him.

"Ha! Well met—and well taken!" the leader snapped, one Sir Thomas Knyvet. "To the Tower, with him! Instantly!"

Mr. Honey, gripped by a dozen hands, perceived that the game was decidedly up.

"This comes of mixing love-affairs with politics," he snarled. "I wish you had arrested me downstairs!"

"Why so, ruffian?" demanded the commander.

"Why? Why?" growled the gunpowder expert sourly. "Because I would have touched her off, and lifted you and me—and the Government too—pretty well up to the Milky Way, that's why!"[*]

[* "When Fawkes saw his treason discovered" (says Slow), "be instantly confessed his own guiltiness, saying: If he had been within the house when they first layed hands upon him he would have blown up them, himself and ail..." It will be seen that Stow was about right.—Author.]

Two hours later he was on the rack, with the Captain of the Tower and others standing by ready to take down the list of names of his fellow-conspirators.

"For the last time, fellow, name these men!" demanded the captain.

Guy shook his head, and the captain signaled to the torturers, who threw themselves on their levers.

A SUDDEN dire pain shot into Mr. Honey's knees; he came to with a frantic start, to find himself again in his Twentieth Century flat, with Peter, the white-eared black cat, clawing furiously at his master's knees in an endeavor to keep his balance. Evidently Peter, leaping possibly at a venturesome mouse, had misjudged his distance. But Mr. Honey did not mind. He was too much relieved to be home again. He had had enough of the Seventeenth Century—enough and to spare. Once again the power of the pill had waned only just in time to save him from an experience which he had not the least desire to undergo. For a time he sat glowering at the fire; then finally he rose, shaking his head, and put the pills away.

"Awful, awful!" he said sadly. "What a past! Shocking! I should never have suspected it. If this continues, I shall be ashamed to look myself in the face!"

Then he made himself a stiff whisky-and-soda, and resolutely set himself to think of cheerier things. It required all his resolution.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.