RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

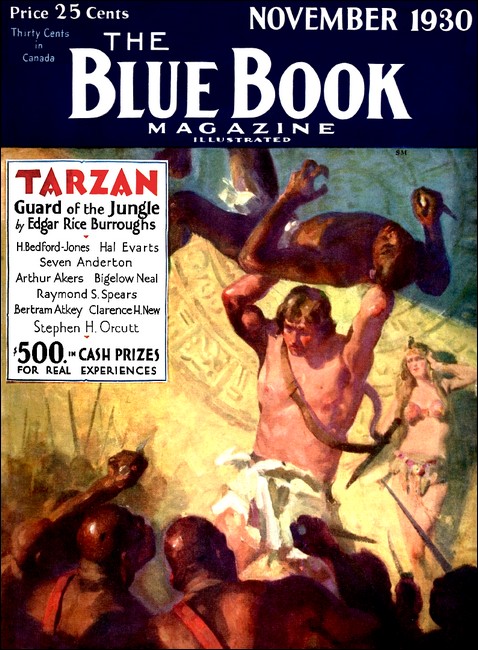

The Blue Book Magazine, Nov 1930, with "The Misunderstanding with Louis XIV"

In doubling on the trail of a former existence a

man may find himself a hero—or quite the opposite.

WHILE traveling in India Mr. Hobart Honey of London happened to save the life of an important Tibetan lama; and in gratitude the reverend gentleman bestowed upon him a remarkable gift—namely, a bottle, itself a rare and most valuable example of Chinese glassware, containing certain pellets possessing the singular power of temporarily reinstating the swallower of any one of them in one of his previous existences.

Mr. Honey—unmarried, middle-aged—had taken some months to screw himself up to the point of an experiment. Nothing but an insatiable curiosity and a very good opinion of himself would have driven him to it. If he could swallow a pill and be certain of finding himself back in the days when he was, possibly, King Solomon, Julius Caesar, Richard the First, or some such notable man, that would be quite satisfactory. But there seemed to be a certain risk that he might select a pill which would land him back on some prehistoric prairie in the form of a two-toed jackass, or something of that kind.

At length Mr. Honey made the experiment—and found himself the court chiropodist to Queen Semiramis! He had a difficult time in Babylon, and rejoiced when it was over: but curiosity drove him to further ventures—in which he found himself, successively, a singularly miserable cave-man, an unsuccessful and sorely bedeviled pirate, an anthropoid ape condemned to fight a lion in a Roman amphitheater, a charcoal-burner who happened to save the life of William the Conqueror, and an assassin in the service of Queen Cleopatra. Disheartened but persevering.

Mr. Honey tried again, to find himself a character better known, though far from praiseworthy —none other, indeed than the notorious Guy Fawkes. It was without enthusiasm that Mr. Hobart Honey, sitting comfortably in his study in company with Peter, his pale-eared black cat, removed the stopper of his pill-bottle preparatory to swallowing his ninth pill. Rather was it with the grim determination of a man who has embarked upon an unpleasant undertaking, but nevertheless is determined to see it through to the bitter end.

Gone was the delightful feeling of curiosity and expectation which at first had preceded his experiments with the pills; and the pleasing anticipation of discovering himself transplanted, so to speak, from a Baker Street flat to the glories of an ancient throne was no longer with him. He had realized that—to use an Americanism—there were "no thrones in his." The only sensation of which Mr. Honey was now aware was one of horrid doubt as to what particular kind of rogue or villain he would find himself to be when the pill had done its fell work. To such an extent had the pills lowered his self-esteem.

BUT for all that the author proposed doggedly to persevere, for he could not altogether abandon a lingering hope that he might yet find himself deposited, as it were, in an incarnation in which life was worth living. Perhaps he might find himself to be a knight, or even a humble archer; surely that was a sufficiently modest ambition! At a pinch he would not object to being Simon the Cellarer. After all, it was a respectable way of earning a living, and might conceivably give him a very valuable knowledge of the drinks of those days, which would be something gained, if not much.

So, with a rather forced and slightly reckless laugh, which did not deceive Peter for an instant, Mr. Honey swallowed Pill Number Nine, and left it to do its worst—which it did promptly and efficaciously.

Mr. Honey "awoke" to find himself in Paris. Not, of course, the Paris of these days, but the Paris of the days of the grand monarch Louis XIV.

The view-point from which Mr. Honey was first regarding Paris was somewhat restricted—in fact, from a bed of straw in a stable in one of the lowest quarters of the city. He was sharing this bed with an ass, and one of the ass' hoofs was resting upon his chest in the friendliest way—almost, indeed, as though the ass had thrown a protecting near foreleg over Mr. Honey. It was a one-stall stable, and there were no other occupants, except an elderly he-goat of completely disreputable appearance, who desisted occasionally from his efforts to devour portions of the ass' harness, hanging close by, in order to survey the pair on the straw with an extremely sardonic expression.

Mr. Honey, with a gesture of profound annoyance, violently threw off the embracing hoof of the ass—causing the animal to bray briefly but discordantly in its sleep—and sat up abruptly.

It was significant that his first thought, in spite of his drowsiness, was for the long Italian rapier at his side. This slender but markedly businesslike weapon he proceeded to draw from an extraordinarily shabby sheath, and lovingly polished it upon his rather short and shabby breeches.

He handled the sinister instrument of dispatch as though he loved it—as indeed he did—not merely because it was a remarkably good rapier, but because it was absolutely the only article of value which he possessed, except perhaps a tolerably nifty little dagger which he wore at his belt. Further, it was his sole means of livelihood.

For Mr. Honey was now about to reexperience a few brief hours of life as it was in the days when he had been—and now again really was—Signor Hoba Hona, a bravo of Italy in, be it added, somewhat reduced circumstances.

It was mainly upon his reduced circumstances that he reflected as he mechanically polished and repolished his pliant stock-in-trade.

"Was it, then, for this that I adventured from the sunny South to this town of Paris?" he muttered in the excellent

French which he had learned from his mother, a Frenchwoman. "To forgather with asses and goats in their unsavory kennels because I lack the price of a bed and breakfast? Hah! I do not think so—decidedly not!"

He executed a brilliant lunge at the interested goat, handling the glittering blade with the deftness of a master.

"Hah, there, goat!" he observed, suppling his wrist with his customary swift and intricate morning exercise.

The gleaming point quivered and flashed within an inch of the hide of the sardonic-looking goat. "Would thou wert a fat bourgeois stuffed with gold, and in a dark alley, goat," said Mr. Honey, lunging elaborately—a little too elaborately, indeed, for his foot slipped, carrying him irresistibly forward stiff-armed, so that without in the least intending to do so, he ran the goat through as though it were merely blotting-paper.

"Bah!" went the goat hurriedly, and died abruptly.

The bravo withdrew his point with a startled oath, and examined it carefully, for it had jarred against the brick wall on the far side of the goat.

"An accident, ass," he said uneasily. "I swear it. I might have ruined the rapier as well as the goat."

But the ass merely looked disgusted, as did a man who had appeared at the doorway at the moment of the fatal stroke, and who now entered the stable, even as Mr. Honey wiped the rapier.

The newcomer evidently a low-class innkeeper, saw instantly what had happened, and burst forthwith into a torrent of French.

Three times Mr. Honey endeavored desperately to explain, and three times he failed.

The voice of the innkeeper began to rise, and the bravo perceived that it was time to be leaving. So, with an extraordinarily quick twisting movement, he transferred his grip from the hilt to halfway down the round blade of the rapier, and struck the innkeeper violently over the ear.

The innkeeper ceased his lamentations, and dropped quietly down upon the still recumbent ass.

Mr. Honey examined him swiftly.

"'Tis but a bruise; he will recover himself in time," he muttered presently. He sheathed his weapon, searched the innkeeper, found a purse, requisitioned it, and swiftly departed from that place.

Such were the events which ushered in Mr. Honeys first dawn in Paris. It was not a very brilliant start for an ambitious bravo, who, finding business impossibly slack in Italy, had migrated to Paris in search of advancement—but he hoped to do better. There were plenty of openings for a steady and industrious bravo whose prices were reasonable just along then, and Signor Hoba Hona knew it.

Louis XIV was at his zenith, and things were going with a whirl in the French capital. Money was being spent very freely by those who had it to spend. Love-affairs were extremely plentiful, intrigues, private enmities, and jealousies even more so, and, despite his somewhat squalid start in Paris, Hoba Hona, having transferred the contents of the innkeeper's purse to his own, felt his sunny Southern nature expand and warm as he walked along searching for a hostelry wherein to breakfast and think of his future.

"It is impossible that a man like me can fail to get on here," he mused. "What? As good a swordsman as ever came out of Italy, and twice as handy with the dagger as any man I ever met I Let me but get one order from a nobleman to remove some objectionable person or other, and the rest will follow. It won't be long before Mother will get some remittances which will surprise her."

He twirled his mustache and swaggered into a good-looking inn, where he proceeded with the chill arrogance of a man who lived on his blade, to rap out orders for a very extensive meal indeed.

They made haste to attend to his requirements. It was too early in the morning for many customers to be abroad; indeed, Mr. Honey was the only customer in the dining-room except one—a thin, elderly person with rather weasel-like features, dressed well, but quietly. He looked as though he might be a politician, or somebody connected with such law as there was in Paris in those days. He was breakfasting at a table in the window, and Hoba Hona who like most un-studious men liked company, civilly requested permission to share the table.

The political-looking person acquiesced readily; he went so far, indeed, as to state that it would be a great pleasure to him, running his eye over Mr. Honey as he spoke, in a needle-pointed gaze that left very little of the bravo's outward appearance unnoted.

Both men were evidently hungry, and little beyond ordinary civilities was said for about three-quarters of an hour. Then, engulfing the quart of wine he had ordered, and calling for a further quart, Mr. Honey leaned back with a sigh of content.

Twirling his gigantic black, mustache, he gazed across at his tablemate.

"A fair city, sir," he said conversationally. The political-looking man reflected for a moment.

"It is alleged to be, sir," he said cautiously. Then, expanding a little, he added: "It is fair to those who can pay their way."

"Ha, ha!" went Mr. Honey, with a somewhat forced laugh. "You are of a practical turn of mind, I perceive. And how fares it with those who cannot pay their way, sir?"

"Meagerly, my friend, meagerly," responded the politician. "They die considerably."

"Ha! Is that so?" The bravo frowned. "And how fares it with a man who is prepared to carve his way, good sir? What does Paris hold for a man of gentle birth who is a past-master of the rapier, whose dagger-work is perfection, whose wits are keen, whose brains are super-excellent, and whose person is highly presentable? How fares it in Paris with such a man?

"That would largely depend upon his courage and industry. Do you know of such a man?" inquired the politician, gazing at Mr. Honey through half-closed lids.

"He sits before you," said the bravo complacently.

"Indeed?" murmured the other, with but mild interest.

"Fresh from Rome," added Mr. Honey.

"Ah!"

"With the best blade in all Italy to keep him company." The bravo tapped his rapier.

"Could you not find service in the South?" asked the politician.

"I refused orders from one king, two princes, several cardinals, and a large number of noblemen," lied Hoba robustly. "Why, you will ask. Because I was afflicted with an itch to see Paris again—I am half-French—I declined them all. I said: 'When I return, gentles, we will talk together, but—for the nonce there is nothing—er—doing. Let me alone. I am for Paris!' And I came away. Here I am—a good man, a rare man, a godsend to anyone in need of a bravo! Have you such a need, sir, or do you know anyone who has? I am open to accept contracts for a week or so paltry terms. Later, up goes the price. Anything, anywhere, any time. I will run your man through in fair fight or in foul, according to price. I will pull him down and release him from the cares and anxieties of this life, in the open or up an alley, as per orders. I use daggers, rapiers, broadswords, pistols, sandbags, mallets, crowbars, saws, razors, hammers, any weapon you choose to name, all equally well. My motto, sir, is 'Business'. If you want anyone pinked in the mazzard, let me know, and I will quote you. If you prefer to have him shoved over a cliff, call on me and name your figure. My name, sir, is Hoba Hona. Mother hush their children with the sound of it in Italy, and men step off the sidewalk when they see me coming. And my terms are low, but for quick cash; no credit given in any circumstances whatever. Are you on?"

The political man surveyed him in silence for a moment, then suddenly slid across the table a bulging purse.

"Take that, friend, as a precursor of many larger ones to come, and at the hour of three be at—"

He dropped his voice to a whisper, naming an address, rose abruptly, and without waiting an instant save to glean that Mr. Honey understood, he slid out of the room. . . .

The political man slid across the table a bulging

purse. "Take that, friend; and at the hour of three

be at—" He dropped his voice to a whisper.

At three o'clock Mr. Honey was at the appointed place—to wit, a side-door of a mysterious-looking house in a side courtyard in a side-street. It was, indeed, a very side-long affair altogether. The political man, looking more political than ever, received him silently at the door, and steered him to a small apartment furnished with excessive plainness.

"Here," said the man, locking, bolting, and barring the door, "we shall be unheard and unseen." Mr. Honey sighed gustily and sat down. "Dry work, talking!" he said. "However, let's get on with it. What do you want done? And whom? And how much?"

The political person leaned across the table, and gimleting Mr. Honey with his eyes, began to whisper. He whispered long and earnestly, the bravo nodding his complete comprehension.

Presently he finished, with a final question as to what Mr. Honey would charge.

"Charge? Let me see," said the bravo musingly. "You want me to go tonight to one of the pavilions of the king near Versailles and await the arrival of a gentleman in a crimson cloak, who will reach there to dine with Madame la Marquise de Montespan at eight o'clock precisely. I am to obliterate him and return here to report. Well, it will cost you a thousand pistoles net cash. Killing people round kings' pavilions comes high, you know."

The political-looking person pushed a bulging leather bag across the table without hesitation.

"There are twelve hundred pistoles there," he said. "Do your work; then remain at the inn, living quietly, until you hear from or see me again."

"Very good, sir," replied Mr. Honey, with a new respect in his voice.

He had expected to be offered a hundred pistoles, and would have taken ten rather than lose the contract.

At seven-thirty that evening the bravo might have been seen standing behind a tall thick shrub at the side of a path, some twenty yards from a beautiful little pavilion in the woods, not far from the palace at Versailles. He held his naked rapier in his hand, and was peering steadily up the path.

He looked much like a beast of prey crouching for his spring. There was in his pose a sinister and tense alertness that augured ill indeed for the gentleman who was coming to dine at the pavilion with Madame de Montespan, king's favorite, that evening.

Mr. Honey intended to make no mistakes. This was his chance in life, he argued; for while he had not the very faintest notion as to whom the political-looking person was, he knew that the man was a somebody, and he intended to please him.

So he crouched, waiting and staring.

Then suddenly a big black hound came running silently along the path toward the pavilion.

"Hah!" breathed Mr. Honey.

The hound saw him when he was about three yards away, and without hesitation, leaped at him, like a dog that had been trained to leap at strangers on sight.

The bravo's wrist moved slightly, and the hound seemed to transfix itself upon the ever-ready blade. The thing was magically swift. Within a space of seconds, the hound was dead and dragged into the brushwood.

Then a man came strolling along the path at a leisured pace, humming an air, all unsuspecting.

The bravo, who had dismissed the affair of the hound much as one brushes off a fly from one's cheek, balanced himself, and just as the newcomer came level with the bush, he stepped swiftly out.

Even as he did so a woman's voice rang out warningly from the pavilion.

"Take care, Louis! An assassin!"

Louis!

Too late to stop the deadly thrust, Mr. Honey realized whom he was killing. The King! The man lie had fondly believed he was serving through the political-looking person

But the rapier, striking true to a hair over the king's heart, bent like a bow and completely failed to penetrate.

The king, wisely, was wearing a chain-mail shirt—and a good one.

But the rapier bent like a bow. The king,

wisely, was wearing a chain-mail shirt.

This would not have saved him, however, had Mr. Honey not discovered in the nick of time with whom he was dealing—for the bravo knew all about chain mail, and his long slender dagger was in his left hand ready to perforate the king where he did not wear mail. But he did not use it. Instead, he dropped on his knees and apologized.

The king looked him over thoughtfully: a very beautiful woman came down the path from the pavilion.

"Shall I signal for the guards, Sire, and have him thrown into prison, pending his torture and execution at dawn?" she said.

Louis XIV shook his head.

"Not immediately, I think, dear madame. I am curious about the rascal. Who are you, fellow, and why do you wish to kill me?"

"Pardon, Sire," said Mr. Honey hurriedly; "it was a case of mistaken identity. I am a bravo, fresh from Italy, and I believed that I was employed to kill an enemy of Your Majesty."

"Employed by whom?"

Without hesitation Mr. Honey described the person of political appearance, and briefly gave the details of the contract. The king's interest deepened. But with a meaning glance at Mr. Honey, which the bravo rightly interpreted as a warning to say no more for a space, the monarch turned to the lady and, with a tender firmness which for all its tenderness brooked no denial, escorted her back to the pavilion.

"It is not seemly that these little ears should hear the base and sordid details of the low intrigue which I must have from the bravo," said Louis fondly, and returned to Mr. Honey.

"Now, ruffian, speak plainly!" he ordered. "You were hired to kill a gentleman in a crimson cloak who was to dine with Madame the Marquise and you believed that you would be serving me by doing so? That is your story? It never occurred to you, dolt, that the gentleman in the crimson cloak might be the King of France, eh? And you believed, ass, that the King of France found it necessary to hire a bravo from Italy to clear a rival out of his way? Fah, you are a fool, I perceive! A million blades are at my disposal, lout, for any purpose."

Humbly, Mr. Honey said that he realized that now. It had escaped his attention before, he added.

"It is merely another plot against my life, clown," said Louis serenely. "And I know perfectly the spinner of it. He shall provide us a little diversion this evening. Remain there, oaf!"

The king blew a shrill call upon a little gold whistle, and within five seconds armed men were racing down the path.

"D'Artagnan," said the king to the foremost of the men, a tough-looking individual in the uniform of the King's Guard. "Dismiss your men—save for Messieurs Porthos, Athos, and Aramis."

The person called D'Artagnan did so.

"It is done, Sire." he announced, rather unnecessarily, as all the men disappeared save himself and three—none other than the famous three musketeers Porthos, Athos, and Aramis.

The king waved an airy hand toward Mr. Honey.

"This black-avised grotesque has attempted to assassinate us. D'Artagnan," said the king.

"Ah!" went the quartette, and turned to the unfortunate bravo. But Mr. Honey was not daunted.

"So be it—four to one!" he said, the point of his rapier flickering like the tongue of a snake. "Mark me, my birds—oaf and lout I may be, but I know my job. Come on!"

But the king intervened to spoil what promised to be a very gory little affair. He ordered the musketeers to put up their steel, and gave a few low-voiced instructions to D'Artagnan. Presently the four men hurried away, and the king turned to Mr. Honey.

"I have sent for the person who employed you to assassinate me," he said. "Doubtless, believing that his plot has miscarried, he will hasten hither. He will come by this path—for all others will be barred to him. Now, I have often felt curious to see a genuine bravo engaged upon his business. Therefore, take your stand and dispatch me this traitor in the correct style of the best bravo. If the work pleases me I may give you your life!"

Mr. Honey did not hesitate. Bowing deeply, he turned away, and made his simple preparations.

"I will show the king how a real bravo gets his daily bread, or I'm a Dutchman," mused Mr. Honey. "And when it is over, if he doesn't feel that, as a matter of common-sense, he ought to import a few more of us—under my command—it will because he doesn't know real talent when he sees it."

The minutes passed, and, just as the light began to fade, a step sounded from down the path, and the political-looking person came hurrying into view. Mr. Honey, his own life at stake, watched him from behind his bush like a cat.

He worked so swiftly and silently that his victim never realized that he was in grave trouble. Like a cat Mr. Honey watched; like a cat he sprang. This man also was wearing a mail shirt, but it only prolonged his life by three-sixteenths of a second. The bravo seemed almost to sense the mail; he used the dagger, and the hirer of assassins perished without a sound.

THE king paled slightly as he saw that it was not the mail shirt which had saved him. Mr. Honey turned from his victim, bowing deeply, as the king came across and peered down at the dead man.

"Always a viper, traitor, and ingrate!" he murmured. "Well, you have a traitor's reward."

"Always a traitor and ingrate!" murmured

the king. "You have a traitor's reward."

He mentioned no names, and Mr. Honey never knew who the man was. It never occurred to him to inquire—for it was all in the day's work.

The king turned to the bravo.

"A foul trade, bravo!" he said. "I would love to break you on the wheel. But I promised you your life. Begone! If you are in Paris at noon tomorrow you are a dead man!"

Mr. Honey took this as a hint that he need not remain—and he went away. "And that's gratitude!" he said sourly, as he passed out of the wood.

A sudden figure barred his way.

"Monsieur the bravo, I think?"

"Yes. What of it?"

"I am D'Artagnan, and I do not like your face. It is so offensively ugly that it causes me to feel giddy. I wish to fight you because of your face. My friends also"—three more figures loomed through the dusk—"find your features extremely nauseating. They too desire to fight you."

Mr. Honey understood that D'Artagnan was deliberately insulting him to provoke a quarrel. They could not fight him on the grounds of what had occurred that evening, for the king's word protected him.

But if a new quarrel cropped up it simplified things.

"Well, you wart, you and your friends have come to the right man!" Mr. Honey snarled, and his blade came sweeping out. "How will you have it? Here and now and one by one—or would you prefer to fight me together? Just as you wish!"

"This is not the hour—we must attend the king!" snapped D'Artagnan. "But tomorrow at dawn, behind the Luxemburg. Does that suit you?"

"It does! I will settle your affair there, pale pups!" said Mr. Honey.

"At dawn then, monsieur, behind the Luxembourg." they said simultaneously. "I shall be there!" said Mr. Honey.

BUT he was not; by no means was he there. He was, instead, in his flat in London—for even as D'Artagnan and his trio vanished in the direction of the pavilion, the power of the pill waned, and Mr. Honey found himself transferred without warning back to the Twentieth Century.

And, curiously enough, when one considers what an extremely mild-mannered and law-abiding man he was in his modern incarnation, Mr. Honey found himself, for the first time, well satisfied with his adventure. As he said to Peter the cat, prior to settling down to work: "I may have been a ruffian—probably I was—but, at any rate, I was a skillful and courageous ruffian, in my way. It isn't everyone who would have taken on D'Artagnan, Porthos, Athos and Aramis as readily as I did—or, at least as I should have done, if I had had time. That is something, at all events. How say you. Peter?"

But Peter had nothing to say. Evidently he did not approve of bravos. Nor, actually, did Mr. Honey—when his enthusiasm cooled down; at any rate, he kept his experience to himself.

This was just as well, for nobody would have believed him had he told them of it They would have attributed it to dreaming or drink—probably the latter. Already several of his friends had recently told Mr. Honey that he seemed to be changing—becoming harder, harsher, colder. So the burglar who broke into Mr. Honey's flat that night, and took away, among other things, the Chinese glassware bottle containing the marvelous pills, probably did the author a far better turn than he did himself.

After the first shock, Mr. Honey bore his loss with remarkable fortitude—indeed, with cheeriness—though be often wondered whether that misguided burglar ever chanced to swallow one of the pills—and what happened to the man if he did.

But naturally he never found out.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.