RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

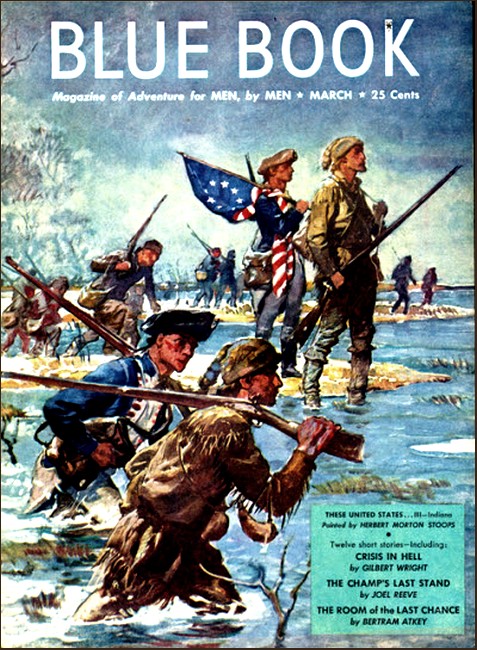

This story was illustrated by Charles Ransom Chickering

(1891-1970), whose works are not in the public domain.

Blue Book, March 1947, with "The Room of the Last Chance"

IT was toward the end of his tour in India in search of local color, that the celebrated novelist who wrote under the pen-name of Hobart Honey had with great presence of mind flung his heavy camera at a mad—or maddish—dog which was aiming itself at an elderly absent-minded Lama from Tibet. The camera had reached the back of the dog's brains-container corner-first, and the misguided animal forgot the Lama forthwith. It disappeared, semi-concussed, round a corner and up an alley, complaining bitterly of the tourists.

The Lama, who like many other people had a marked distaste for being bitten by mad dogs, was passionately grateful to Mr. Honey for his timely intervention. He proved to be one of these high-powered Lamas, so full of wisdom that he frequently strained himself holding it in. After a brief conversation, the novelist returned to his hotel. That evening he received from the Lama a large bottle, full of pills, and a long letter. It was not until he had read the letter twice that Honey realized that these were very special pills. They were not designed to correct any of those physical embarrassments which occasionally afflict the ordinary person and for which the ordinary pill of commerce is supposed to be the correct ticket. On the contrary, these were super-pills which could be relied upon to launch whosoever swallowed one, on a super-experience. The man who took one would, immediately after taking it, find himself temporarily relieved from the trials and troubles of his present life or incarnation and returned for a time to some incarnation which he had lived before.

The Lama, a naive old gentleman in many ways in spite of his terrific wisdom, had quite sincerely believed that he was giving Mr. Honey an extremely valuable present when he sent him the pills. On learning during their conversation that Honey was a writer he had expressed great astonishment that one so young and presumably inexperienced should attempt to earn a living with his pen and had decided that his gratitude could best be expressed by a gift which would furnish a writer with a few experiences that would widen his knowledge of the people of the world, past and present. Hence the big bottle of pills.

In the long letter which he sent with the gift the Lama said, among a good many other things:

When thou art in the mood for education, swallow one of the pills and await peacefully that which will at once take place. Thou wilt return to live again for a space of time to some one or another of the uncountable lives which thou hast lived before the one which thou art now living. Be not alarmed if thou shouldst awaken in the form of a wild swine of ancient days, a lizard of the rocks or an humble ape bescratching itself on the banyan bough—for thy days thereas will be but brief, and ere thou hast time to accommodate thyself to thy new surroundings, lo! the power of the pill shall have waned, and thou shalt find thyself again upon thy couch in these present days.

Fear not thou wilt ever be what thou hast not once been. If, in past ages, thou hast been a great king, a noble lawgiver, a mighty prophet, a glorious general, maybe the power of the pill will reinstate thee for a while in all thine ancient splendor; or if thou hast been before of a somewhat inferior quality, as it might even be no more than a jackass browsing upon a hillside or a rat journeying darkly through the runs and tunnels of his dismal abode, so mayst thou be again. But what-so-be-it befalleth thee, it is certain that thy knowledge of past things and places shall wax enormously, and thou shalt become exceeding wise—so that thy fellow scribes, scratching busily like fowls behind the granary, shall behold thy works with amazement.

So much for the Lama's letter. There was a good deal more of

it but the foregoing extract gives the idea of it well

enough.

When, next day, Mr. Honey called on the Lama to thank him, he found that the old gentleman, leaving no address, had wandered on to mix with the four hundred million or so of India's denizens, thus rendering himself pretty well anonymous.

On his return home, Hobart Honey proved himself not quite so youthfully inexperienced as the Lama appeared to believe him, for he promptly emptied the pills into another container and sold the bottle of wonderfully worked old Chinese glass, with amethyst-and-green dragons all over it, to a museum for twenty thousand dollars.

For a time he let the pills lie.

Then, one wet evening when he was feeling too bored to amuse himself and too lazy to go out and pay somebody else to amuse him, he decided to try one of the Lama's pills. He did so and got the shock of his lifetime. The power of the pill returned him to an incarnation that he had lived in ancient Babylon as a practising chiropodist in the reign of the great Queen Semiramis. He had the misfortune to offend the Queen and she had completed that incarnation for him by the simple process of having him thrown into the pit of the tigers—large and bad-tempered ones, specially kept at the back of the palace for the purpose of squaring the Queen's accounts with those who offended her.

But the Lama had told the truth about the pills, and Mr. Honey, though fired with such great suddenness out of his Babylonian incarnation, had wakened to find himself safely back in his present-day incarnation— but with his memory of Babylon and its people greatly refreshed.

SINCE then he had taken many pills with widely varying

results. He had been in many interesting situations in all

periods of human history; he had met a number of curious people,

some of whom he had killed and some of whom had killed him. He

had been hanged, shot, starved, impaled, drowned, tortured,

beheaded, outlawed, banished, bastinadoed and knouted; he had

been rich, poor and neither; he had loved ladies of all ages and

epochs; he had been to innumerable places—but few which he

would have cared to revisit. On the whole he had found life tough

in most of his past reincarnations; and he had not yet revisited

one in which he proved to be anybody of much importance.

But he could not shake off the notion that at some period he must in the nature of things have been one of the Great Ones, and he was determined to persevere with the pills until he discovered what it was like to be what the Lama had called a "great king or a glorious general," or someone of that caliber. It was with that hope in his mind that he settled down in his big easy-chair on the night before his fortieth birthday, took off a couple of glasses of port in quick succession, and trickled a pill out onto his palm. For a few minutes he stared at it, fascinated.

"Not everybody would take a chance with you," he said to it, "if they knew as much about their own past as I know about mine!"

He knew that it might land him for a time back in some incarnation in which he had figured without much success as a prehistoric man in difficulty with a giant cave bear, or a deer in front of a pack of wolves, or a bison of the Middle Ages about to be hamstrung by an Apache fond of bison-meat, or any one of a thousand things that had once lived. Against that, he might wake to find himself Julius Caesar, Jonah, Hamlet, or Noah on a cruise in his Ark; he might be Alexander the Great, Hercules or T'Chaka the Zulu king. He might even be Antony dallying with the lovely Cleopatra on the Nile, King Charles the Second calling on pretty Nell Gwyn, Henry the Eighth dancing with Anne Boleyn, Lancelot coquetting with Queen Guinevere, or Louis the Fourteenth of France taking Madame de Montespan to lunch at his private pavilion in the park. Anybody, in fact—anywhere—anywhen!

He gave himself another glass of port and sent the pill down in front of the wine, leaning comfortably back in his chair.

AS usual, he got quick action. It seemed to him he lost

consciousness almost instantly—as indeed he did. It was as

if he had dropped asleep, instantly to begin dreaming.

But this was no dream—the noise in which he seemed to wake was too vivid, the taste of wine on his tongue too sharp for any dream. As was the friendly blow, heavy enough to fell a bullock, he received on his shoulder just as his consciousness registered the fact that he was no longer Hobart Honey, the novelist of these days, but instead was Honibus the Gladiator—in the days of Nero, Emperor of Rome.

He had just entered the canteen back of the wild beasts' den in which a party of his fellow gladiators were drinking after their day's training, and it seemed that he was, as the saying goes, the center of attention, the cynosure of all eyes. And not very welcome attention at that, for they were laughing at him.

"Ho, Honibus, he will assuredly turn thee inside out!" roared a huge red-haired burly giant from Liguria. "Drink, man, drink with me whilst thou canst still hold wine!"

Honibus, a magnificently built Roman, turned on the Ligurian.

"Art turned simple in thy understanding, Superbus?" he said. "Who is this who will turn me inside out? By all the gods, the man is not yet born of woman who will achieve that!"

He glared round at the company.

A huge black-browed mongrel who looked like a cross between a giant Turk and an outsize, double-chested gorilla with a broken nose, emitted a roaring laugh.

"Nay, retiarius, there thou missest thy guess," he bawled, laughing again. He was half-drunk. "Give me wine, somebody, ere I wreck this desert-dry canteen!"

A thick-eared Greek boxer who was screwing up some nuts and bolts or similar whatnots on his iron and leather boxing-gloves*, put down his spanner and stared curiously at Honibus. He opened a gap-toothed mouth to speak, but whatever he said was drowned in a sudden inferno from the other side of the wall: The vicious, strangled snarl of tigers, mingled with the loud, chesty roar of lions, and the gruntings of what could only be gigantic bears. There was such a shocking note of bestial rage and ferocity in this sudden clamor that even the deliberately brutalized company of gladiators, well used to the sounds of the beasts, listened in silence for a second.

[* They appear to have liked a lot of good, honest metal—preferably iron—in the professionals' boxing-gloves of those days. See Ovid in "The Art of Love." —Bertram.]

"What aileth them?" said a frightful-looking male creature. Immensely heavy, this was Ultra, one of the Pintos. He looked like an artificially enlarged, double blacksmith, except for his shaven head which was but half head-size and as round as an unusually round grapefruit. No brains, evidently. He had run to muscle instead of gray matter—which probably was why he was a Pluto. His duty in the arena was not to fight but, armed with a sledge-hammer and in company with a few others like him, to finish off those unfortunate gladiators who were too seriously injured to be of any further value as gladiators.

There entered a fearfully scarred, oldish, and leathery-looking man who smelled like several leopards. This was an assistant bestiarius or, as we should say, menagerie attendant.

"What hath enraged thy great cats, that they burst so suddenly into harmony, Hotiron?" demanded Ultra with a staggering imprecation. "Can't hear myself drink!"

"Nay, they are excited. The black Carthaginian war-elephant Moloch hath just arrived and the beasts have scented him. By the gods, they may well howl, for if they ever have to face him in the arena they will— Ha! He announceth himself! Hearken! Never have I heard such a trumpeting—never have I seen so towering, so vast, an elephant. Nor one so vicious or of so bloodshotten a temper!"

HE was right. It was indeed an awesome din with which the

fabulously costly, newly imported fighting elephant promptly

answered the clamor of the man-eaters!

"Hah, my braves, that's a lad will provide sport for the populace at the Games on Sunday!" chuckled Hotiron, reaching for his wine. "I guarantee it! And if ye believe me not ask Honibus on Monday—if he's here to tell you!"

Honibus turned on the old bestiarius with a blood-curdling oath.

"Ask me, thou palsied old sot! Why ask me? What have I to do with your lousy war-elephant? I— a retiarius—a lighter with net and trident! Bah! Better ask the captives and slaves in the dungeons—or the rhinoceri in their stables!"

Hotiron gaped at the net-fighter. "Thou dost not know? Hast thou not seen the Amended Orders? Nay, I see how it is—thou hast been on pass this afternoon."

All the gladiators laughed—hoarse, growling laughter, for Honibus was far from popular. He was the idol of the Lady Delyria, a lovely patrician of great wealth, influence and nerve, who was—or had been—a kind of favorite of the Emperor Nero—and her bribes to the Master of the Gladiators for the pleasure of Honibus' company, as it were to tea, were so huge and frequent that the number of passes granted him were the cause of a dangerous amount of jealousy among his comrades—if one can call them comrades.

"Hey, Honibus, we were trying to tell thee, were we not?" shouted the Greek boxer. "Whilst thou wert coquetting with thy sweet Delyria—and we were sweating blood in the gymnasium—the Orders for the Sunday games were amended, by special command of Nero himself. And in the Amended Orders thou art billed to fight Moloch the new war-elephant! Habet, Honibus!"

Honibus felt a sudden icy chill, then threw it off as the manifest absurdity of the thing occurred to him.

He glared at the Greek.

"And, perhaps, thou Peloponnesian polecat, thou wilt enlighten my ignorance if I ask just precisely how the hell a retiarius is to fight an elephant?"

Old Hotiron chuckled.

"That is what Nero wisheth to know, I suppose!" he said. "And to see—on Sunday next!"

"But it is without sense. No man could carry a net that would entangle a damned great elephant—much less throw it!" snarled Honibus.

"True, O Honibus," sneered the Greek. "The Emperor probably overlooked a little thing like that."

Honibus was doomed and knew it. But he kept his head. He realized that if he was going to do anything about it he would have to get cracking, for he had much to do and very little time in which to do it.

He leaped to his feet and flung himself out of the canteen, followed by roars of savage laughter from the crowd of desperadoes that passed as his comrades. He did not blame them; the canteen of the gladiators was not a good place to seek sympathy. Their business was death and nobody knew better than they themselves that they were as certain of ultimate extinction in the arena as was Honibus. It was only a question of time—and not much of that ...

Delaying only long enough to take something that flashed greenly from his kit-bag, Honibus made for the quarters of Gargoyla, the Master of the Gladiators—a hard-boiled old scoundrel who, by industry, graft and complete callousness had worked his way up to his present altitude from a humble position of assistant executioner somewhere in the provinces.

"Hah!" he said as Honibus strode in. "It was in my mind that I should be seeing thee ere many hours had sped! What wantest thou, retiarius?"

"A midnight pass to the City," growled Honibus.

Gargoyla's laugh was like the rattling of a sheet of galvanized iron loose on a roof in a gale.

"Certainly—with greatest pleasure, Honibus. Any little thing like that— any time," he said satirically. Then his tone changed.

"Why, thou pinheaded orang, thou art billed to fight Moloch the war-elephant in the arena on Sunday! Dost think I would let thee out of my sight ere then? It is the order of Caesar himself! Dost think I hunger to be cast into the crocodile pool? A pass to the City? What city? Some city in remote Asia, maybe! I know thee too well to let thee loose, thou great, gangling oaf! I have never trusted thee, even before thou wert booked! And as for trusting thee now, I will do that only when I am consumed of a desire to see thee vanishing in a cloud of dust over the far horizon —and not before!"

Honibus scowled.

"Gargoyla," he said desperately, "I am a man of few words. I need half an hour—an hour; I go no farther than the villa of the Lady Delyria. That I must do. She is a favorite of Nero. How long, thinkest thou, will it take her to persuade him to cancel this mad amendment of the order for the Games? Look!"

He produced suddenly an emerald the size of a walnut, a priceless gaud, a gift from Delyria.

"Quick, Gargoyla, make up thy mind. This jewel for an hour's pass! Real? Is it real, askest thou? Only the best and biggest in the world! Didst ever know a Roman lady stint her well-beloved of a jewel or two?"

Gargoyla's hand came out and closed over the stone like a grapnel.

"An hour, then—no more, mark ye! I shall have thee shadowed. Four of the Thraces* shall dog thy steps. Try to evade them, retiarius, and they will bring thee back to me in four separate portions or divisions, and I will send thee to Nero on a large dish! Go then—what art waiting for?"

[* Gladiators who specialized in the use of short sword and buckler. Very competent; not parties to annoy. —Bertram.]

ONE of the loveliest patrician ladies of Rome and one of

the most unscrupulous, the Lady Delyria (widow of the richest man

in Rome, who had died of a surfeit of unidentified cold steel a

year or two before) was asleep when Honibus was conducted to her

by her confidential slave-maid. But she woke with astonishing

rapidity as soon as the gist of Honibus' story penetrated.

She leaned to him, speaking earnestly. Unlike many of the Roman ladies of the period, she was genuinely fond of her gladiator. That is to say, she had not yet grown tired of him.

"It is murder, of course, my little retiarius! But a trifle to Nero. He liketh thee not, little man!"

He was about twice her size, but it was her playful affectation to use these affectionate diminutives. Honibus glowered.

"He liketh me not! What doth he know of me, a common gladiator, that he should like me or like me not?"

She looked at him with a curious little secret smile.

"It may be that he knoweth more of thee than thou mayest suspect. Come, sit close by me, my littling, that I may whisper. The very walls of Rome have ears in such times as these!"

She pulled him down to sit beside her and drew his close-cropped head to her lips.

"Nero is jealous of thee!" she breathed, almost soundlessly.

Honibus looked incredulous.

"Jealous of me! Nero! Nay but that is not possible! An Emperor—Caesar!"

"Emperor for how long, Honi, think you?" came the subtle whisper. "Said I not that these are strange times? There are whispers everywhere of revolt! There are swords that no longer lie quiet. They are awake and moving—like bright, deadly snakes that no longer sleep! But the time is not yet ... Sh!"

She listened for a moment, then "If Nero had heard even that, he would have me beheaded!.... Listen to me, my little anaconda: We have been betrayed, thou and I. It was that Lacedemonian girl, Icene, who was my maid but a little time ago. I have had her whipped and whipped again. She shall end beneath the talons of the beasts in the arena, for she was criminal—a traitress and spy, an eavesdropper, a listener in the dark, a seller of secrets!"

Her eyes were blazing with sudden sheer ferocity. Even Honibus was a little startled.

But the wildcat glare died away as quickly as it flared up. She was pressing close to him, sensuously rubbing her beautiful head against his muscular arm, rather like one of the cats of which she had, for a flashing second, reminded him.

"Thou knowest, Honi, that I am—or was—a favorite of Nero—if to be one of the many he has cut down as a fool cuts down flowers with a cane is to be a favorite! And it is in my mind that the Orders for the Games were thus amended, in respect to thee, because of a comparison I made between thee and Nero. It was no more than a passing comment upon his qualities as a man, not an emperor—and thine as a man, not a gladiator. Talking with the Lady Poppelia, my half sister, I said that whereas, as a man, Nero was as it were a fat ignoble crayfish which had been out of the water too long, while thou wert a superb lion—and more, beloved octopus, and more! Poppelia agreed. But we were overheard by Icene and sold to those who conveyed it to Nero!"

"Gods! What said he?" ejaculated Honibus, enfolding her not unlike the beloved octopus she claimed him to be.

"He said, regarding thee, that he would be interested to see what such a superb lion would do in the arena against the Carthaginian war-elephant, if it arrived in time for the Games. Regarding me, he gave a secret order that I be poisoned after the Games and the rumor be spread that I had killed myself because thou hadst been trampled and torn by the elephant, and my wealth confiscated—one tenth thereof, and her freedom, to be bestowed upon that evil, treacherous slave-snake, Icene—with Poppelia to be secretly killed later!"

"So thou too art under sentence? By the gods, it is a venomous crayfish! Yet, what can we do?"

Delyria laughed like a tigress with her temper well under control. She had her failings but lack of courage was not one of them.

"Thou shalt see! I am not the richest woman in Rome for nothing! I have sent for one who can aid us— for smooth gold and smoother revenge!"

She clapped her hands and a slave-woman entered.

"Hath the learned Arcassia arrived? Then admit him to me. And send more wine and more wine and yet more wine to the Thraces without."

The slave disappeared and an aged, white-bearded, quiet man with one blank eye and a ghastly pitted face, entered. This was Arcassia, the so-called sorcerer. He had been one of those oil-soaked human torches with which Nero had once illuminated one of his garden parties, and had escaped only by chance, hideously burned.

"Hast achieved aught, Arcassia?" demanded the lady. "The gold of which I spoke awaits thee—if thou hast planned well."

She pointed carelessly to a silk sack by her couch.

"Feel it, Arcassia, feel it well. There is more gold than thou hast ever seen! More than thou wilt ever need for all thy designs against—him who blinded thee by fire."

The lean fire-scarred hands of the sorcerer ran over the sack like those of a musician over his instrument.

"Yes, it is enough," he muttered. "Listen! Oh, Delyria—oh, retiarius, this is the design I have planned. Listen with all thine ears! Thou wilt be last called into the arena at the Sunday games, Honibus. The war-elephant will be maddened by the odor of blood and the reek of the savage beasts and his own pain. For that is what renders him forever raging, unmanageable, and therefore useless to the Carthaginians—the pain: He hath one of his great tusks decayed at the base and his sufferings are unimaginable. That is why he is so terrible—he hates everything and knows not why. Nero meaneth him to destroy thee! He will be awaiting thee, furious and raging. What shall a man accomplish with a net and trident, against a mad elephant? But listen! At the instant thou enterest the arena there will arise such a cloud of black smoke that all things will be obscured. Nay, there is no magic; I have made the smoke! It will arise from the burning of certain things contained within little pots which will be thrown from all quarters into the arena by men I have paid and posted to their positions. Doubt not that they will succeed. They are chosen carefully and more gold awaits them when they have succeeded. They will raise a cry of 'Revolt!' But ignore it; it is a matter which concerns thee not.

"The elephant will panic in the smoke. Avoid him, for he will be maddened with fear and pain and anger. Avoid him, I say—I cannot help thee in that. Look well to thy net, lest it be rotten—having been secretly made useless. Cling to thy trident; examine it well before thou enterest the ring. If it hath been tampered with have ready another, a good one, wherewith to exchange thy spoiled one. Avoiding—if thou canst— the elephant (and thou art a dead man if thou failest), race for the wall of the arena exactly under the Emperor's seat. Carved there on the wall is a narrow decorated panel and at the height of thy head is a carved bunch of grapes that is a part of the decoration. Twist this bunch of grapes to the right (for it is the lever or handle of a secret door) and the marble decoration will swing inward like an opening door. Pass through and close the door behind thee. Though the arena be packed, none shall see thee, for be well assured that the arena shall be black and blind with smoke. Cling to thy trident—there may be tigers, or the lions may be loosed, or the great pythons, according to Nero's mood.

"Thou wilt find thyself within a little secret chamber. Abide there silently and await those who will come to thee in the night when the arena is deserted—men of mine whom thou canst trust. Nay, look not astounded! The secret room hath been there since the arena was built. Only the Emperor and a few others know it. All Rome knows that under the royal reserve there is at the foot of a flight of marble steps a retiring-room; but those who know of the secret cell behind the retiring-room are less than ten. It was so designed, and it hath two doors—one to the arena, one to a long passageway or tunnel to the outside of the arena. It is a device for the safety of the Caesars in an emergency—a revolt—any such an occasion! Now, repeat the things I have told thee."

He listened attentively as Honibus repeated very accurately and carefully his instructions.

"Yes, yes ... Again!"

Again Honibus went through it.

"Good! ... Beware the elephant—and the wild beasts! Be steady—be cool and watchful and thou art saved! Be careless in but one particular, and the gods themselves could not save thee—for Nero is set upon thy destruction in this fashion."

Lady Delyria's fingers closed on Honibus' arm as the four Thraces strode in—fearful-looking toughs, half-drunk, but not so drunk that they had forgotten their orders.

"Time, Honibus!" growled their leader.

The alleged sorcerer looked at them.

"Yea—time, Honibus!" he said.

The Lady Delyria saw how it was with the escort, knew that they were as inflexible, as implacable, as the certain death which awaited them it they failed to return with the net-and-trident fighter.

"Yes, it is time," she whispered. "Go with them. I will await thy return, little octopus!"

BY the time that the huge black war-elephant strode into

the arena, the place was vile, reeking of blood, of the stench of

the glutted beasts of prey, of the sweat of thousands of

spectators wrought up to a pitch of savage excitement. Though the

Pintos had dragged away the dead, though fresh sand had been

scattered, there was no cleanliness there. And the odor of burned

flesh still hung heavy and horrible on the still windless

stifling air, to bear witness to the savage zeal of the

Mercuries—men armed with long metal rods, the ends kept

red-hot in braziers, with which they tested the unconscious, the

dead, or those who feigned to be either. Some of the great beasts

had returned to their dens; some remained glutted and lazy,

sprawling on the sand. A huge python rasped his enormous body

ceaselessly round the foot of the walls, frightened and enraged

by the clamor into a sinewy menace ready to attack anything that

moved or that it encountered. Many people—criminals,

prisoners of war, slaves, Christians—had died terribly that

afternoon. Here and there the great beasts grunted and snarled

still over bones they were too satiated to touch.

"A retiarius in combat with an elephant!" Nero sneered.

Most of the gladiators were dead or maimed; Honibus had seen them die. The redheaded sword-fighter Superbus was dead, killed by the gorilla-like Turkish giant, who in turn was himself killed a few seconds later. The Greek boxer had been smashed like a shellfish by a vast Scythian boxer.

Nero, well aware of the threat of ultimate revolt against his evil reign, had spared nothing to give the blood-thirsty populace what it wanted, and now the moment had arrived when the Games would culminate in the incident which interested him most—the spectacular murder of Honibus.

He leaned back comfortably.

"We have wondered often how a retiarius would comport himself in combat with an elephant! Crayfish!" he sneered to a woman reclining at his side in the center of the brilliantly appareled crowd hived round about him under the great awning. She laughed a little uncertainly, not understanding the allusion to a crayfish.

But the Lady Delyria, sitting close by, understood. Her eyes gleamed and she paled a little in spite of her confidence in the one-eyed Arcassia. She had given him a fortune and she knew he would add to that all his brain could conjure to perfect his hatred of the royal animal that was Caesar.

The great elephant went raging past the royal enclosure, trumpeting insanely; he saw the python and made for it. An immense maneless lion swerved away from the vast beast, roaring ferociously as he went, but too heavy and sluggish to dispute the path of the monster. The great snake reared high with gaping jaws, formidable even though not venomous, striking desperately with its blunt hammer-head, writhing about the tusks and trunk of the elephant. But it was no match and the mighty pillar-like legs of the huge fighting beast began to pound the thick writhing coils to shapelessness.

IT was at this moment that Honibus entered the arena, the

great iron-barred gates crashing remorselessly shut behind

him.

He looked coolly about him—taking in every foot of the airless, sun-flooded, murder-sodden killing-ring. Though it seemed to the bloodthirsty crowd that he was utterly doomed, it was evident that he meant to throw away no slender chance. He carried an old net and an older trident. But he could rely upon these which he had secreted, for all his better and later nets had been tampered with.

He moved stealthily forward a yard or two, flashing a glance at Nero's box. He could see the panel which was his target.

Then from his right, a lean, flat-flanked tigress wheeled snarling and with amazing speed launched herself at him. Unlike many of the beasts, she had not eaten in the arena, for she was a killer first; later, in the gloom, she would glut herself at leisure—but not while she could kill. It was as if she knew that Honibus was her last chance to satisfy the strange and fearful lust that possessed her.

But this time it was no unarmed Christian upon whom she sprang; instead. this was a cool, highly trained, tremendously strong, and skillful and deadly dangerous expert at his strange art, fighting for his life and determined to sell it dearly.

"Come then, striped devil!" shouted Honibus, balancing himself for his cast. The tigress leaped. But she did not reach the man, for the net, perfectly cast, met her in mid-air and she dropped, flailing madly at the entangling meshes, imprisoning herself as a fly imprisons itself in the web of a spider. Crazed with fury, she rolled and Honibus was upon her in a flash. The blade-points of the trident glittered in the sun as they descended.

In a matter of seconds the striped killer was dead, killed with almost contemptuous ease by a master of the trident-fighter's craft.

ATTRACTED from his own slaughtering by the hideous uproar

of the tigress, the great war-elephant stared across and pivoted,

his trunk swung high over his head.

Nero leaned forward with a chuckle and two women—the ladies Delyria and Poppelia—sitting not far from the Emperor, gasped, though long since inured to the sights of the arena.

"Gods! He hath now to cross the whole arena!" gasped Delyria. "Now, sorcerer! Now, Arcassia—ere it is too late!"

Even as she breathed her appeal, an object like a small earthenware pot flew from the lower tier of the amphitheater to fall a few feet from the elephant; it broke silently as it fell, and emitted a dense stream of thick black smoke at the base of which flickered here and there tiny thorns of needle-like jets of flame.

Honibus tore his trident from the dead tigress, watching the startled elephant. Then another smoke-pot fell—and another—and another. The pots were flying fast now, for Arcassia had spent a fortune in bribes to skilled and desperate men.

The huge crowd began to scream furiously for the death of those who dared to interfere with the Games— but the flying pots were too many and with tremendous speed the smoke welled up in huge black billows of spreading flame-shot gloom.

Nero glared, shouting orders, unheard in the rising tumult, then fell back on his seat, biting his nails.

SUDDENLY the nerve of the great elephant went; he recoiled

from a pot that sent into his eyes a huge black gout of smoke, so

dense that he was blotted out of the view of many watching him.

Only his mighty trunk waving high above the rank rising cloud of

black could be seen as he backed away. Black fountains of the

heavy greasy smoke ascended now from many points of the arena,

and there sounded a note of distress and panic in the vast, wild

trumpeting of the enormous killer.

There were those who saw that the retiarius was crossing the arena, slowly, quietly, watchfully—weaving his way through the deepening gloom spreading from the smoke pillars. Then with a scream the elephant turned, racing clear of the smoke to the far end of the arena. Those who saw anything at all, saw his trunk describe a vicious scything swing at Honibus as the big beast thundered past him. But the gladiator evaded it by inches.

The din was fearful and to the shouting of the people was added the fearful uproar of the wild beasts as they came to the open mouths of their dens, smelled the smoke and recoiled far back to the blood-smeared recesses of their grated lairs.

Then a new cry, coming front many places, pierced the clamor:

"Revolt! Revolt! Revolt!"

A stampede began as people pressed out of the tiers of seats.

Nero leaped to his feet.

"What shout they?" he demanded, glaring about him.

"Revolt!"

It cut like a blade through the blaring of the crowd and of the beasts.

"They shout 'Revolt!' O Caesar!" said a painted favorite, fearfully.

Nero struck at him with a feeble fat hand, cursed him, and hurried to the marble stairs by the royal reserve.

And now Honibus had reached the decorated panel below the royal awning. The fear-maddened elephant went charging past him through the smoky gloom, so close that it seemed to the trident fighter as if he watched the black side of a great ship race past him within six inches.

He coughed in the strangling smoke-reek, his eyes streaming as he groped for the carved bunch of grapes of which Arcassia had told him. He could not find it. Here the smoke was at its thickest and most blinding.

He glanced behind him, but could see nothing but the black billowing fog of smoke. The elephant was trumpeting wildly on the other side of the arena, and it seemed now as if all Rome were howling in desperate, blood-freezing unison: "Revolt! Revolt! Revolt!"

Then his groping hand closed on the marble grape-bunch, and he wrenched it round. Well-oiled, it moved easily. He pushed and followed the narrow, inward-opening door, swiftly swinging it shut behind him.

He found himself in silence, in sweet air, and alone. It was a small room, carpeted with a Persian rug, and containing no more than a couch, a table, and a jar of wine. There were swords in a corner, and on the table were certain strange-shaped bottles that were full of colorless, heavy liquid.

"Poisons!" said Honibus. "Yea, the One-Eyed One spoke truth indeed. This is the Room of the Last Chance! For the gladiator as for the Emperor!"

He laughed softly in the quiet room, and reached for the wine-jar, then drew back his hand, his eyes on the array of poisons.

"Nay! Nay! Wine is good but not such wine as this may be!"

He looked at his stained trident.

"Well for me I kept this old, well-proven friend to my hand this day! Never lived there retiarius who made a swifter, cleaner kill! Well for me —that striped she-devil might have spoiled a perfect stratagem!"

Yet even he did not guess how perfect—until suddenly an unsuspected door facing him yawned open to admit a fat pasty painted man with curled hair, who darted in, looking over his shoulder, muttering. Even as the door swung shut behind this man, Honibus caught a far cry that seemed to follow him—

"Revolt!"

"Alone—and safe!" said the newcomer triumphantly, and turned to discover himself facing Honibus. Nero reeled under the shock of it, supporting himself against the table.

"Nero!" cried Honibus.

"Yea!" gasped the Emperor. "Bow down, retiarius!"

But Honibus smiled.

"The days of the bowing-down have run out, O Nero! Like sand within the hour-glass they have fallen to an end. 'Bow down', sayest thou to me? But I say 'Bow down' to thee, O Nero!"

And he drove his trident through the fat neck of the tyrant with such force that it was near to a decapitation.

"A good stroke!" he said complacently. "Never lived the gladiator who made a better!"

Coolly, he watched the man die: then, as coolly, sat down on the couch to wait—as he had been instructed to wait. He felt no uneasiness, for he was unshakably convinced that a plan such as this of Arcassia and the Lady Delyria must inevitably run true to the moment of its perfect culmination.

He pushed the body of the dead despot out of the way with his foot, made himself comfortable on the couch, and went to sleep.

He was awakened presently by the entry of several hard-featured, heavily armed men—strangers to him. They ignored him except for a few quick words from their leader.

"A good stroke, Honibus! But withhold thyself from this matter, for it concerneth thee not. It is a matter of high politics!"

"The gods forbid that I mix myself with high politics!" said Honibus emphatically. He closed his mouth, turned away, and kept it closed. When he looked round the strange men were gone, as was also the body of Nero.

He waited silently.

It seemed to him that he sat for a long, long time in that grim little room of the Last Chance—so long that it must have been the following dawn when he saw the door open and a narrow vertical crack of light widen down the side.

A woman's voice—surely Delyria's —spoke so softly that he only caught a word: "Honi ..."

IT was, however, the voice of Mr. Honey's housekeeper in

his Twentieth Century flat. She was coming in to take away his

coffee-tray—quietly, very quietly, in case he was

asleep.

"Is everything all right, Mr. Honey?" she asked doubtfully. "I—I thought I heard you say something about being 'delirious'."

"No, no—not 'delirious'—not now!" replied Mr. Honey oddly.

He was right. Everything was in order—under control again. Once more the power of the Lama's pill had run out—as usual at an inconvenient moment of that incarnation. That was all ... He had, in fact, "had it."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.