RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

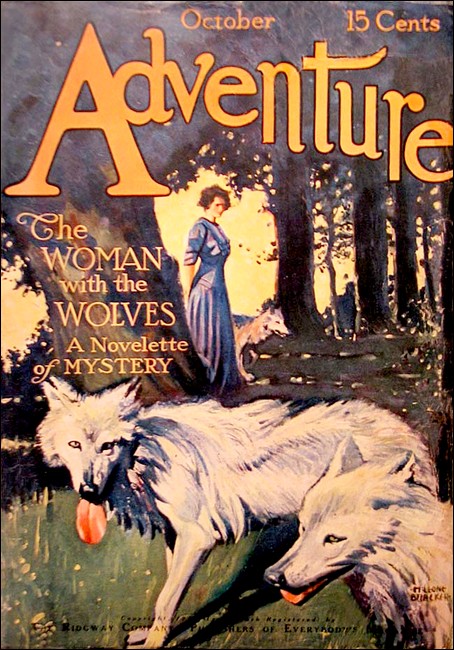

Adventure, October 1911, with "The Woman with the Wolves"

Headpiece from "Adventure," October 1911.

IF you go through the glades and green tree- tunnels round about that triangular iron monument erected to commemorate the spot in the New Forest where the Red King was killed by an arrow glancing from a tree, and from that place proceed westerly—leaning perhaps a little south—you will open up a region of wide bleak spaces, where there are no oak and beech and elm, but only sparse heather and fir, with patches of plentifully-spined gorse. It is desolate in that place and you may go many miles without encountering anything living other than forest ponies, a few yellowhammers, an occasional hurrying pigeon, here and there a lonely lark fleeing from under your feet, and, not infrequently, vipers in and about the marshy places.

In mid-Winter, when a black frost has glazed the snow, this part of the forest has something remotely Russian about it in a small but effective way.

It was in that neighborhood, then, that the affair I have made it my business to relate took place. My friend Torrance, who is an extremely out-door man, has a rather elaborate bungalow there and it was the third time I had come down to pass the beginning of a New Year with him.

He had not come personally to the little country station, just outside the Hampshire boundary of the forest, to meet me. His man—old Gregg—had driven in for me and, unemotional though Gregg knows how to be, I think that he was more than usually pleased to see me.

"Mr. Charles' cough is bad to-day," said Gregg, reaching for my bag. "It's the frost nips his chest."

I believe I heard a resentful mutter of "Cigarettes" as the huge old man turned, handling the big bag as though it were no more than a fan. Under the flickering oil lamps of the wayside station I fancied Gregg's face-looked hard and a little anxious.

We climbed into the little slipper-shaped car.

"I've got to get a few things in the village," said Gregg, as we dropped like a toboggan down the hill that leads sharply from the station. "Owbridge's lung tonic, cigarette-papers, ink, and salt butter," I heard him say to himself as we pulled up at the narrow-windowed, lamp-flickering general shop of the village.

Gregg never writes down a message or list of requirements—and never forgets them. But he forgets nothing—and, I sincerely believe, knows everything—worth knowing. Just as he can do everything—worth doing. Old Gregg is about the only man- servant of my acquaintance that I find myself able to like and respect at the same time.

A man with a piece of bacon under his arm came out of the shop as we slid to a standstill. He was talking over his shoulder and paused a second on the threshold.

"Heard tell of bloodhounds comin' over from Sal'sb'ry Plain to-morra," he said to some one inside the shop.

Old Gregg suddenly stiffened, half-turning his head to catch the reply. His face looked white and worried in the wavy, uncertain lamplight.

"Ah, be 'em, now," droned some one from behind the piled counter. "Take a main host of bloodhounds to find Major Stark, I'd reckon. Nivver heard much good of they things."

The man with the bacon guffawed, came noisily out of the shop, and swung off down the windy street.

"Only keep you a minute, sir," said old Gregg, and passed in under the jangling doorbell.

"Good evenin', Must' Gregg," came the drawl of the shopkeeper, again. "Main cold out to th' Forest, I reckon."

Gregg nodded and spoke quietly.

"And so you'm havin' the bloodhounds out your way to- morra,—they tell me," continued the other garrulously, reaching about his shelves. "Not that they'll do a lot of good. Reckon the Major knows the forest too well to lose his way out there—sober."

The shopkeeper—a little, bald, beady-eyed wisp of a man—shot a look of rustic cunning at tall hard-bitten old Gregg.

"We folk—butcher, baker, tinker and tailor—'ud do as well as bloodhounds to find 'im, I'd reckon, Mr. Gregg, and good cause most of 'em got." He leaned forward across his counter. "I've heard tell the Major owes a matter of three to four hundred pound in the village alone. Now he's gone. Take a main of bloodhounds to find he, Mr. Gregg."

The shopkeeper cackled cunningly as he passed over Gregg's change. I took it that a resident in the district was missing—some, apparently, believing that it was a case for bloodhounds, others that it was a case for creditors. I asked Gregg, as the little car began her climb up to the Forest level.

"It's a Major John Stark, sir," said Gregg, staring straight in front of him. "He disappeared a few days' ago. His horse was found on the road near Stony Cross Hotel—without a rider. They think he intended riding out to No-Man's Court. He was the owner. It is let now to a Russian lady—a Princess, I think. From what she has told the police, it looks as though Major Stark never reached the house that day. He had been there before, but not that day—she said."

Old Gregg turned, and I had an instinct that he had given a little, tight-lipped smile.

"It's a mystery, sir. Mr. Charles will know more about it than I do."

We had topped the long hill and the little car set her droning nose to the Forest. It was bitterly cold and now we seemed to be traveling along an illimitable white road flung across unfathomable canyons of darkness.

I sank down among the heavy furs Torrance had sent for me—although he is a dreamer, Torrance can be very practical—and listened to the strident wind. Our lights ate into the darkness like a white-hot graving-tool eating into soft black stuff; twice I saw little shadowy dark things flicker across the road—rabbits, I supposed they were; occasionally I caught, or imagined I caught, the smell of the busy motor in front, hot and oily; and once we passed a wee spot of light with a shadow behind it—a belated cyclist hurrying out from the desolation of the wind-haunted flats that we were now traversing.

The rush of keen, clean air was making me drowsy when a few yellow lights lifted suddenly away to the right, dodging, darting and flickering behind trees.

"No-Man's Court already?" I said. We had been coming quicker than I had known.

Gregg did not answer for a minute, for just then the little car seemed to falter, to hang in her stride, and Gregg's hand slipped from the wheel to a lever. The car stopped and the wind seemed to hush for a moment, holding its breath, as though to say "What's this?"

"Nothing much," said Gregg, and got out. He opened the bonnet of the car and put his hand into the nest of cylinders and things.

I turned to the lights of No-Man's Court. Even as I looked there came quavering up to me, riding uncertainly on the wind, as it were, a curiously startling sound. There was a sort of remote melody in it, but also there was pain, and desire, and hopelessness, and something very evil. It came again and quite suddenly my blood ran cold.

"Good Heavens! What's that, Gregg?" And I recognized a sort of entreaty for reassurance in my voice.

Gregg looked up. His face was as white in the lamp-glare as I knew mine to be. But before he replied, the sound floated up again—louder this time—and I knew.

It was the howling of wolves.

Wolves—in the New Forest! There was an explanation somewhere. Gregg climbed in again and I demanded that explanation.

It was quite simple—the Russian lady at No-Man's Court kept a dozen of them—pets, just as other women keep little dogs, or birds, monkeys or even lizards. Gregg professed to be quite used to hearing their eery serenades—which made it increasingly difficult to understand his sudden pallor.

Then away to the left the lights of Torrance's bungalow burned friendly through the dark and swung steadily toward us.

OLD Gregg had been pale and his hard face drawn, but his eyes had been cool and steady. Torrance, too, was pale, but his eyes were restless and bright—haunted. He was good- looking as ever, in his thin, aquiline, dark style, but he was changed in some vague, intangible way. All the old humor was gone. Perhaps that is what I missed.

Almost the first thing he told me was that he had not worked for months. I must explain that he is a poet and essayist—he is rich enough to afford the luxury of writing verse for its own sake; that he spends a little of each year in London, moving among people of all kinds from leader-writers to stevedores, cabinet ministers to Punch-and-Judy proprietors, Rabbis to racing-tipsters; that from London he drifts lazily abroad, perhaps to some corner of the Continent, perhaps farther afield; but always the late Autumn brings him, not less surely than it brings the first few woodcock and snipe, to his bungalow on the western moors of the New Forest.

There, with old Gregg, who served his father before him (in one of the Dragoon regiments), Torrance sorted, classified and, I suppose, pondered upon his experiences of the year, wrote, read and dreamed.

Women had never seemed to attract him. Like many dreamers, he had, I think, set up a quite impossible ideal and was content to await her coming.

He lost nothing but the streets and the people by wintering in the forest, for Gregg was a wonderful cook, and thanks to a huge, humming and immensely business-like oil engine carefully housed at the back of the bungalow, there were such aids to comfort as electric lights, hot water, perfect water supply and so forth.

Torrance was thirty, in perfect health, save for a trifling cigarette cough, tall as old Gregg—that is, a fraction over six feet—but shapelier, and until this New Year I had always considered him languidly happy. But now he sat at supper with me, eating nothing, smoking a great deal, and obviously nervous and uneasy to the point of irritability. Three times I looked up to find his eyes fixed in a sort of uncomfortable reverie upon a photograph on the mantel. The third time this happened I got up deliberately—I have known Torrance intimately for many years—crossed over and studied the picture. It was that of a woman. She looked to be about thirty years old, and was extraordinarily beautiful, a kind of keen, wild beauty that stung one into interest. The photograph had been taken in Petersburg, but there was nothing Russian in the woman's beauty.

I sat down again, saying nothing. There was a queer little smile on Torrance's lips, and he began to tell me of a strange custom he had discovered in the Spring of the Old Year among the French charcoal burners. (I believe it was the French charcoal burners, but I am not sure.) I was not listening. I was wondering whether the woman in the picture were the woman with the wolves and what she had to do with Torrance.

He saw that almost at once, for he drained his glass suddenly, drew in his breath, and spoke in quite a different voice.

"I'll tell you the story—part of it—after supper," he said, and his voice trembled. "I must tell some one." I heard the note of desperate impatience and finished my supper then and there.

"Come on, then," I said, took a cigar, and lay back in a chair before the big fire.

I heard old Gregg come silently in behind me and begin to clear the table. Torrance looked into the fire for a long time, thinking. He seemed to be seeking, the proper beginning of the story he was going to tell. Presently he laughed a little bitterly.

"I can only tell you about the affair from my own point of view," he said. "I am in it—in a sort of uninvited, superfluous way. But, really, I am little more than an onlooker."

He waited again. Old Gregg put a couple of decanters, cigarettes and a cigar-box on the table, and spoke quietly. It occurred to me that a tremor lay under his voice.

"Excuse me, Mr. Charles," he said.

Torrance turned.

"From what I heard in the village to night, they are bringing out some of Colonel Shafto's bloodhounds from Salisbury Plain to- morrow," said old Gregg, watching his master's face.

Torrance winced a little, and a slow flush crept up over his cheeks. He looked steadily at old Gregg and there was a queer silence for a few seconds. Then Torrance took a cigarette.

"Thank you, Gregg," he said, and turned to me. "Have you ever seen bloodhounds at work? If not, you'll be interested. There's a—"

Suddenly some one tapped at the casement door behind the heavy curtains—rattled would be a better word to describe the panic-stricken scrabble on the glass—and a quavering voice called from the darkness outside.

Gregg was at the casement in an instant. He shot back the bolts, turned the catch, and a man, panting like a hunted thing, fell into the room.

"They nearly got me—hairy, rank things—great eyes and teeth!" he sobbed. "Look at my coat!"

He stood in the lamp-light, his face gray with fear and exhaustion, his eyes wide with terror. I remember that his mouth hung half-open like that of a frightened child. His face was veiled, as it were, with a network of tiny red scratches—as though he had fallen again and again into gorse. One shoulder of his coat was ripped to ribbons—the fragments hung down over his shaking arm.

Torrance gave him half a tumbler of cognac, and the stark fear slowly faded out of his eyes. Then, all suddenly, he straightened himself and looked round the room with a quick, curiously official glance. I guessed then what he was. Detective-Inspector was stamped all over him—the hard, capable but blunt, rough-cut face, the close-clipped mustache, the short hair, the square shoulders, the quiet blue Melton overcoat.

Quite recovered from his panic, he gave a hard-lipped smile as Torrance laughed.

"I warned you, Inspector," said Torrance.

"And I wish I'd taken your warning, Mr. Torrance! That was the nearest squeak I've ever had."

"The wolves, I suppose?" asked Torrance casually. "You were a fool to risk it. I told you they might be loose."

The Inspector looked at Torrance rather queerly, I thought.

"I believe they were only loosed for my special benefit," he said dryly.

"Oh, that's impossible," said Torrance. "Tell me about it. Take another drink and sit down."

Before he sat down the Inspector went to the casement windows, pulling the curtains to behind him, and stared out for many minutes into the night. Then he came slowly back, shaking his head slightly.

"It's a queer place to get lost in—this New Forest is," he said.

Then he took something silver from his pocket and handed it to Torrance. It looked like a cigar-case. It had been flattened and was terribly dented—as though it had been stamped upon with heavy hobnailed boots.

"Why, what's this, Waynill?" asked Torrance in a tone of surprise.

The detective smiled.

"Major Stark's cigar-case," he said. "I found it out in the forest to-day."

Torrance laughed again, and, looking very steadily at the detective, shook his head in turn.

"I'm sorry to spoil your effect, Inspector," he said. "But it happens to be mine. I lost it a week or more ago. Some one seems to have trodden on it."

He noted the sudden doubt on the Inspector's face, and turned to Gregg, who had been hovering about the sideboard.

"Gregg—what cigar-case is this?"

The old man took it, looked well at it and handed it back.

"Yours, sir—the one you lost ten days ago." He looked at the Inspector, his old face grim and hard in the lamplight. "If there were any cigars in it when you found it, sir, they would be the same brand as these." He pushed the open box on the table to the Inspector, who took one out and looked carefully at the narrow green, red and gold band. He shrugged his broad shoulders with an air of good-humored resignation and took from an inside pocket an envelope containing four cigars, crushed almost to shreds. There were four bands on them—three ragged and one intact. He handed them over to Torrance—who lazily compared the bands with those on the cigars in the box.

"Yes, the same cigars of course,"

"Try one—out of the box, Inspector. We'll call it a reward, if you like."

The Inspector grinned ruefully.

"I'll take the reward," he said, reaching for it, "but you've spoiled a very good clue—between you. Can't you throw a wash in with the reward, Mr. Torrance?" he added.

"Why, of course. Gregg will show you the bathroom."

The Inspector followed the old man out.

I had remained very silent—knowing what I knew. For instance, I was aware that Torrance had always resolutely refused to carry a cigar-case. He objected to take them on account of their size. He rarely smoked cigars at all. But evidently the Inspector did not share my knowledge.

I leaned over to him. "Is that your cigar-case?" I whispered.

He shook his head furtively.

"Whose, then?" I insisted, impatient with curiosity.

Torrance put his lips to my ear.

"Stark's," he breathed, his eyes glittering through half- closed lids.

"But the cigars—did he smoke the same brand as yours?"

Torrance shook his head.

"No. The cigars Inspector Waynill found in the case were from my box. I gave them to him the morning he disappeared. No body seems to have seen him alive after he left here. At least nobody has come for ward yet."

"And he did leave here alive—you'll never persuade me otherwise, Torrance," I said uncomfortably. "Did he say where he was going?"

Torrance glanced at the photograph of the woman on the mantelpiece. If possible, he had become paler than ever.

"He was going to her—to No-Man's Court," he whispered dryly. There was horror in his eyes.

Then we heard the Inspector coming down the passage and Torrance began to describe the ingenuities of his willing domestic slave at the back—the oil-engine.

The Inspector was quite himself again now—stolid, heavily humorous, tenacious, but, I thought, not too intelligent. He lighted his postponed cigar, mixed himself a drink and told us the story of his day's work.

"THERE'S something queer about this disappearance," said the Inspector. "It might be anything from an ordinary 'flit' from a crowd of creditors to"—he hesitated for the fraction of a second—"murder. I'm not sure that I ought to be talking about it even to you, Mr. Torrance."

He chuckled rather heavily. "If I hadn't known you and your man in town for the last ten years, I'm not sure that I shouldn't ask you a lot of questions that would sound a bit suggestive."

Torrance laughed very naturally.

"My dear man, ask 'em now. I've always wanted to see how the police work," he said.

The detective's chuckle deepened.

"Well, to tell the truth, I've asked 'em already. What I haven't asked, you've volunteered one way or another," he answered.

"Oh!" Torrance looked a little blank.

And, privately, I withdrew a good deal of my opinion that this burly Scotland Yarder was not too intelligent. And I did so with some relief, for it was clear, in that case, that the detective did not associate Torrance with the disappearance of Major Stark. If he did, then I was very certain that he would not be sitting there telling us of his day's work.

"I don't know whether bloodhounds are much good at tracking a man on horseback," began the Inspector again, "but if they are, we might see something interesting to-morrow. There are one or two very queer things out there." He jerked his head, indicating the forest; then paused, staring with somber, thoughtful eyes into the fire as old Gregg entered, carefully bearing a wineglass filled with a brown, heavy-looking liquid.

"Your Owbridge's, Mr. Charles," he said gravely, handing the mixture to Torrance.

Gregg was a firm believer in the medicine and, I have no doubt, insisted on Torrance's taking a dose every time he dared to cough. And I am not sure that Gregg was very far wrong.

"What I want to find out," said Inspector Waynill, half to himself, "is the person who has been cutting turf out there at this time of the year and why he did it."

To this day I marvel that the Inspector did not notice the sudden start of old Gregg at these words. He was too rapt in thought, I suppose. For a second the old man be came flaccid. The wineglass slid out of his hand and cracked softly on the thick carpet. He recovered himself instantly, muttered an apology to Torrance's "Gregg! Gregg! You weren't looking, you know!" and went quietly out. But I saw the keen old eyes flash doubtfully at the broad back of the Inspector as Gregg left the room.

"That's it—whose been cutting turf and why? It's rotten bad turf, anyhow," repeated Waynill, looking up.

"The first thing I did this morning was to follow the tracks of Major Stark's horse from your gate, Mr. Torrance. It was comparatively soft weather four days ago—the day he disappeared, but it's been freezing ever since and in some places the horse tracks arc as clear as if they had been molded in plaster of Paris. It's a pity the ground was too hard that day to take boot-marks. Well, the hoofs led me straight to a spot about midway between here and that big house—No-Man's Court—over there. At this spot there's been a lot of turf cut and removed. The Major seems to have ridden up to the edge of the cut turf and then altered his mind and instead of going on turned off to the left at right angles."

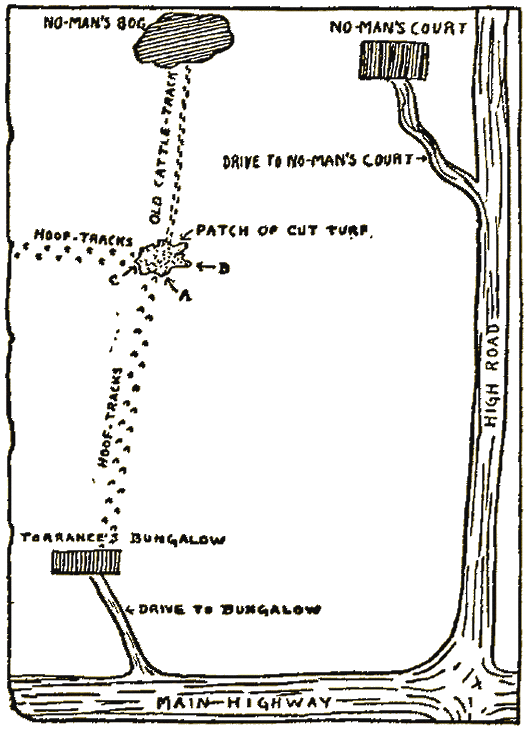

The Inspector took out a small note-book and showed us a rough plan.

"You'll see what I mean if you can follow that," he continued. "'B '—the shaded part—is the place from which the turf was cut—it's just a patch of peaty mold. 'A' is where the Major's horse came to it, and 'C' is where the horse left it. Now that turf was removed after the Major rode away from the place, because there are no hoof-marks on the mold."

"Perhaps the Major jumped over the mold patch," suggested Torrance.

The Inspector shook his head.

"No—I thought of that. If he had, the hoof-marks would have been deeper at 'C' where the horse would have landed, and for a few strides, at any rate, the direction of the hoof-marks would have been straight on—in the same line as at 'A'. But they aren't—they go off at 'C' from the edge of the cut turf at right angles. So, unless the horse turned in the air—which is unlikely—Major Stark did not jump the patch. And if he didn't jump it, the patch wasn't there. You follow that."

We nodded.

"Now at 'A' the horse was cantering. At 'C' he was galloping like the—!"

"What!" I think we spoke together.

The detective smiled and wagged his head.

"Any farmer's boy could see that from the hoof-marks. And that's another thing I want to know. Why did Major Stark canter up to Mark 'A,' turn suddenly at 'B,' and gallop off hell-for- leather at 'C'? And did any time elapse between the change from cantering to galloping? That's it, gentlemen—What happened at 'B'? Was anything spilt on the turf that made it necessary to remove it—blood, for in stance? Or was anything buried at that spot and the turf cut to hide the traces of digging?"

Waynill paused again, brooding. Mentally, I unreservedly withdrew the whole of my opinion as to the Inspector's intelligence.

"Well," he roused himself once more, "whatever happened, the horse galloped away either with or without his rider. So I followed his tracks—they were the only fresh tracks about the place—I had a thorough look round for them. But I only found your cigar-case, Mr. Torrance."

"Yes, it would be somewhere about there that I lost it," said Torrance composedly.

"Oh, it was a good three hundred yards farther on," corrected Waynill. "It was quite tarnished and discolored. Lying in the middle of a kind of rough cattle-track. Considering that we've had no rain for the last week you must have lost it at least ten days ago for it to have become so discolored."

There was a queer dryness in his tone and Torrance stared.

"I see," he said. "If it had been less tarnished and nearer the patch of cut turf, you would have—"

"Asked you a question or two which are not necessary now."

Torrance shrugged. "See how nearly I have approached a new experience, Herapath," he said, smiling across at me.

The detective slowly helped himself to another whisky and soda.

"The cigar-case was not the only thing I found before I followed up the tracks of the horse," he said, and dipped two fingers into a waistcoat pocket and brought out a tiny gold locket. We craned forward.

"It was under a little clump of heather near the edge of the cut turf," he said. "And it has not tarnished at all. That is another thing I want to know. Who is the owner of this locket?" He touched a spring and the little ornament opened. "And," he continued, his heavy face suddenly grim, "and just who these two young people are. You don't happen to know them, Mr. Torrance, I suppose?"

Torrance took the locket and looked at tentatively at the two people. Then he shook his head and passed it to me.

"I'm afraid I can't help you, Waynill," he said. "They look very young—but you have probably noticed that for yourself," half satirically. "I haven't the remotest idea as to who they may be."

I looked at the two faces. They were those of a young man of about twenty-five—handsome enough but arrogant looking, and of a girl, thin, dark-eyed, with wild hair. She looked to be about eighteen years old. The photographs were somewhat faded and seemed to have been cut from a rough snapshot and fitted to the locket. Curiously enough, there was something vaguely familiar to me in the face of the girl. It was as though I had seen a picture of her, in one of the illustrated weeklies, for instance, a week or so before. But I could not reproduce that picture quite perfectly in my mind.

"It is rather a queer thing," I said, "but I seem to know that girl's face. I haven't the least notion where or when or under what circumstances. It is more than likely that she remotely resembles some one I have interviewed, or whose picture I have seen in a periodical."

Waynill turned to me with a quick interest.

"That is exactly how I feel about it," he said.

I turned the locket over. There was no monogram, but round the upper rim was engraved, "To Mary from Jack." I read it aloud and returned the locket to the detective. Torrance had risen and was playing with the things on the mantelpiece. I chanced to look at the mantel, when presently he sat down—and the photo of the woman that was taken in Petersburg was gone.

"Of course, Major Stark's name is John. That would be 'Jack' to his girl," said the detective. "I thought of that this morning, out there. If this boy is Stark, it is Stark as he was ten years ago, judging from the latest photo of him. It struck me that I might do worse than hunt for 'Mary'—grown ten years or so older. Now this locket belonged to 'Mary' anyhow—men don't carry lockets much and it's inscribed to her, and it's not altogether crazy to assume that 'Mary' dropped the locket. At any rate there's a chance of it. Now, this isn't London where there's a hundred Marys to the acre. This is the New Forest, where there's about one to the square mile, and I fancy that one of these Marys could tell us a good bit about Major John Stark if we can find her.

"That's the conclusion I had come to by the time I had finished tracking that horse's hoofs from the patch of cut turf. It was easy enough to follow where he went, although it twisted and turned in the most aimless fashion. No horse with a rider on its back would have twisted about like it.

"I followed the track for about seven hours to-day and it brought me out to the highroad near the Stony Cross Hotel. It was the hostler of that hotel who found the horse without a rider. I went into the hotel and had something to eat and thought it over. Then I saw the hostler. Now, listen a moment, gentlemen!" The tone of the detective had taken on an edge, a keenness. He was speaking now quickly, tensely, as a man hot on the trail of another speaks. Torrance was watching him intently.

"Major Stark left here at eleven in the morning. He cantered straight toward the spot where the turf has been cut. He got there say at eleven-twenty. Then there's a blank—so much time unaccounted for. Presently his horse gallops away from the spot—gallops say three miles, and then drifts about, feeding here and there, just wandering; and eventually strikes the hard road. He drifts up to the hotel at about four o'clock, just as it was getting dark, the groom said. Nothing much seems to have been done to find out what became of the Major until next morning. Then the groom, starting at nine, followed up the tracks of the horse from his end and arrived at the cut patch of turf at about two o'clock, and from there came to this house.

"He didn't seem to learn much from the cut turf, but it helped me. For I had examined it, as you know, and, after my talk with the hostler to-day, I know that the turf was cut between eleven- thirty last Monday and two o'clock on Tuesday. Allowing four hours for cutting—it's a fair-sized patch—we find that the Major vanished between eleven-thirty Monday and ten o'clock Tuesday. It's not much to know, perhaps, but it's something. Particularly if 'Mary,' whenever we find her or any of her men folk has such a thing as a recently used turf spade."

The detective shook his head

"I wish I'd arrived at Stony Cross Hotel on Monday instead of Wednesday," he said. "If only I'd decided to see Rufus' Stone before Stonehenge, it would have made a difference."

I gathered that Waynill had been taking a bleak holiday seeing the sights of Wiltshire and Hampshire, when, arriving at Stony Cross Hotel (the hostelry near Rufus' Stone), he had chanced upon the mysterious disappearance of Major Stark.

"Well, the next thing was to see if I could find 'Mary,' or at any rate, the owner of the locket, and it seemed to me that I couldn't go far wrong if I started among the maids at the only house with women in it near the spot—No-Man's Court. As there's been enough time wasted in this case as it is, although it was nearly dark when I started, I set off to have a look at the household at No-Man's Court."

"I HAD been told about the wolves that the Princess keeps— queer pets, but I've heard of queerer," he continued, "and I don't mind admitting that if I'd brought a revolver I should have dropped it in my pocket before I started from the hotel. I'm not one of the brave ones where wild animals are concerned. I'm not ashamed to admit that bad-tempered big dogs worry me if I'm unarmed, and the fear of the wolf seems to me to be thoroughly implanted into every kiddie before he gets away from his mother's apron-strings. Red Riding Hood and all that stuff—I suppose it's something that's come down generation by generation from the time when mothers really did have to warn their youngsters against real wolves. Anyhow, they make me nervous. Still, I understood from the people at the hotel that they were tame enough and that the Princess always had 'em kept well under control, so I started off.

"It was pretty gloomy by the time I got there and an occasional howl—sort of sorrowful—that I heard as I approached the house along the private road didn't cheer me up. I remember I hoped I should get on well with the Princess. I felt that I wanted friends—you know how these great black spaces make a town-man feel, and the night, where there are no trees, is like a great black mouth and you're walking into it.

"Then you come to a lot of stark naked firs and, if there's any wind, they moan at you and the heather and bracken hisses and chuckles under your feet. It gives me the hump. I prefer a murder investigation in and about streets and houses to one in a forest round about a dark old haunted-looking mansion ten miles from anywhere and with a dozen wolves singing mournful lullabies to themselves round the back.

"I sent in my card, marked 'urgent,' and a string of reasonably humble verbal apologies. I don't know whether the butler offered up the apologies or not but he came back regretting that the Princess was 'indisposed and unable to see me.' I could see Madame Dolgourki however. I gathered that Madame was a kind of lady secretary to the Princess and I saw her. She was very amiable. She had known Major Stark, she said, and was very upset about his disappearance. I believe she was sincere. The Princess was very anxious that I should be given every assistance, she explained, and—what could she do for me?

"Well, I ran through a list of the maid servants, and Madame had them paraded before me one by one. I had the 'Mary' locket before me on the table. I saw them all, from a splendid old white-haired house keeper (she was like an elderly clergyman's wife) down to a strapping, big under housemaid. Not one of them could have been 'Mary.' You know there's a touch of blood about the girl in the locket. At least she looks different from the ordinary run of girls.

"Well, that finished my business at No-Man's Court. I wasn't badly disappointed, for I had not expected to find my lady of the locket right away, and, anyway, I couldn't quite see why I should connect Major Stark with one of the staff of a Russian princess who is visiting England for a year or so. It struck me as curious that with the exception of Madame Dolgourki and the Princess every woman in the house should be English. But, after all, that's their affair. I had noticed a big colored photograph on a table, and when we had finished the servant's parade I took a look at it, with Madame's permission. It was a portrait of the Princess in all her glory, crown or tiara, robes, ermine, jewels. She's wonderful. In my business we come across some beautiful women, but the Princess Komorzekovna, if that photo spoke the truth, is the most beautiful woman I ever remember seeing.

"I ventured to say as much to Madame. But, after all, the Princess wasn't 'Mary.' That child is unusual enough in her way, but she couldn't have grown into such a woman. So I thanked Madame and prepared to get out. My back was to the window and Madame was facing me. Just as she rose her face changed, the way a woman's face changes when she sees some one behind you she recognizes. I turned pretty quickly, just in time to see a whitish blue disappear from the window.

"'The man Lovell!' said Madame. 'Oh, but I recognized him. He was peering in.'

"It struck me as funny and I asked a few questions. Who was Lovell and why was he so anxious to see me? I knew, of course, that the servant's hall would be humming with gossip, but it did not strike me that any ordinary servant would be so keen to look at me as to climb a veranda and peer in through the window.

"Lovell, it seems, is the kennel-man and wolf-keeper at No- Man's Court. Madame does not like him. Once or twice, it appears, she has noticed him staring too familiarly at the Princess. She told me he was always quiet, willing, deferential, and very capable in his line. But Madame dislikes him. She thinks he's a Gipsy. Well, there wasn't much in that—women are curious about men staring; sometimes it's right, some times it's wrong—but I thought I'd take a look at Mr. Lovell on my way home.

"I bowed myself out and asked the butler where I could find Lovell. He told me to go to the kennel-house, and pointed to a light at the back of the house (we had come out of a side door) and left me to find my own way. I think his dignity was hurt at the idea of a detective running his eye over the maids.

"I went along down the dark side of the house to where the wolves are kept, and, passing through a shrubbery, came out all at once to a biggish building that had a wire run stretching away from it like a very long fowl-run. The wire seemed to me to be very little thicker than a telegraph wire. Half a dozen big, dark shapes—with eyes—were trotting up and down this run. Every now and then one or other of them would stop and stare at me and let out a little howl.

"There was a light in a doorway at the side and I went in. A man—Lovell—was sitting there in a sort of kennel- kitchen reading a paper by the light of a hurricane lamp. He was smoking and had his feet cocked up one each side of the fireplace. He stood up civilly enough when I came in. I noticed that he had a pair of heavy hobnailed country boots on. He was better dressed than the ordinary Gipsy, but any one could see at a glance that he was Gipsy to his finger-tips.

"'Sir?' says he, very quiet, putting down his pipe and paper.

"'Are you Lovell?' I asked.

"'Yes, sir.' For a Gipsy he had very steady eyes. He kept 'em fixed on me all the time, quite respectfully, you understand, but not the least bit nervous or afraid.

"'Why climb on the balcony, Lovell?' I said. 'It's not nice—Madame Dolgourki thinks it's impertinent. And, anyway, it's irregular.'

"'I beg pardon, sir—climb on the balconies, sir?' he asked. And he did it well—he's over intelligent for a kennel-man. His eyes led mine, in the most innocent way, to his heavy boots.

"'Quite so, Lovell,' I said. 'You don't understand what I mean, I know. You don't climb balconies—in hobnail boots. That's all right. Where have you put the rubber-soled shoes you used? Oh, it doesn't matter. Call it my joke.'

"His face hardened a bit at that.

"'Excuse me, sir,' he said. 'Have you had permission to come here?' He gave a sort of little click with his tongue when he said this. I didn't like his tone.

"'I have, my friend,' I said.

"'From Her Highness?' he clicked his tongue again.

"'From Madame Dolgourki, representing Her Highness..' I was mild enough, for I wanted to see how far he would go.

"'Where is your pass, sir? We have had accidents at the kennels'—'dens' was the word he used—'before, and it is a rule now that visitors have to get a pass.'

"'Pass, my man?' I said. 'My name and business is my pass, if necessary.' I think I was getting angry. He gave a sort of grim smile.

"'Scotland Yard, or Y. M. C. A—it's all one to the wolves,' says he and something in his eyes suggested to me that I should turn round. I did so quickly—and I'm bound to confess that a chill fluttered along my spine. Four great wolves were sitting quietly in a row against the wall behind me. They had, I suppose, come out of their 'dens' when he clicked his tongue. They sat there, quietly enough, like four big, grayish dogs, their eyes half-closed and their tongues hanging out.

"'It's all one to the wolves,' says Lovell. 'I'll tell them you're from Scotland Yard, sir, if you like.' He let out a gleam at me from his eyes.

"'I see that you are a wag, my Romeo,' I said, 'only take my advice and don't over do the wit. It's a bit of a boomerang some times.' It occurred to me that the reception he had given me spoke ill for his conscience and I decided to make a long shot.

"'Lovell,' I said, one eye on him and one on the four fiends by the wall, 'you're a Gipsy—and a man can't disappear in the forest under your very nose, so to speak, without your eyes and instincts showing you something about it. You've seen the spot where that turf is cut. What do you make of it? What do you know about it?'

"He signed to the wolves and they cleared off through an open hatchway in the wall. Then he looked at me.

"'I've seen nothing—and I know nothing,' he says. 'What do I care about Major Stark?' He moved across to the stove where he seemed to be boiling food for the Princess's pets.

"I got up.

"'Lovell, I believe you're lying,' I told him. 'If you are, look out! Do you think because you have a few circus friends there behind the wall you can play with the law? Listen to me, my man, if I don't learn a little more about the disappearance in a couple of days, I'll arrest you on suspicion. See?'

"It was a bit high-handed, I suppose, but the covert insolence of the man had riled me. I doubt really if he had anything to do with it at all, but he'll probably bolt. He's a Gipsy and no Gipsy will wait to face a thing, innocent or not, if there's a chance to bolt. It's in their blood—practically every time one of his race shifts camp he's bolting from some thing trifling, as a rule, but serious some times. I'm going to have him watched by some one in the house and if he gives one little sign of flitting I'll arrest him and chance it.

"Well, I left him with that. You needn't tell me I tackled the man the wrong way. I know it. But there's something superior about the fellow. Intelligent. He's not the sort of man to be deceived by the ordinary offhand, round-about-the-bush inquiries.

"I came back again past the house and struck the carriage- drive. You know, the drive there, a wide, gloomy place. No hedges—just a strip of turf each side with firs running up close to the edge. I came fairly quickly, thinking that I had not got a tremendous lot out of my day's work after all, when, about half-way down the drive I got a cold, beastly idea that I was being followed. It was brutally dark, and you can believe I turned round pretty smartly. Nothing there.

"'Wolves on the brain,' I told myself, and stepped out again. But I'd started looking behind. It's a rotten trick that. I went the next hundred yards with the skin of my back crawling. I nearly ran. I began to sweat and then all at once my fear took me by the throat and twisted me round. In the darkness behind, about two to three feet off the ground and twenty yards away, there were eight spots of light. They hung there, perfectly still.

"I went clammy. I've read about that sort of thing—but it was the first time I've experienced it and I'll see to it that it's the last.

"I hesitated and then moved on again, looking back. The spots of light moved on too, swinging up and down a little. I knew then they were eyes, all right. It occurred to me that Lovell was probably there with the wolves, too, but his eyes didn't show and it was just guesswork. I came on, sideways, like a crab, and the eyes came too. Only they seemed to me to come quicker—to be gaining. Well, I couldn't stand that. I knew I was very near the end of the drive and I ran. There are no gates, you remember—the drive turns in off the road; and even as I set foot on the highway one of the wolves jumped for me and 'chopped'—that's the only word, I swear—at my throat from behind.

"It missed, but I felt it rip the cloth of my coat. I heard a sort of angry shout behind. That was Lovell, I suppose, and then the light from your window beamed up across the flat. I headed for it in a bee-line. Scared cold I was. I fell a dozen times. I remember thinking vaguely that the wolves weren't following me beyond the road, but I didn't want to stop. I wanted to keep running, and I did, but I couldn't have gone another yard when I struck your casement—"

Waynill ceased, breathing rather quickly. That sudden wolf- leap and the slash of those long jaws were too vivid in his memory to allow him, as yet, to tell his tale without emotion. Then he looked at us with a pale glare in his eyes.

"I'll arrest Lovell to-morrow if I have to shoot every wolf the Princess owns!" he swore.

There was a momentary pause.

"But perhaps Lovell was not responsible," said Torrance, "I believe the wolves are as tame as dogs. It may have been an accident."

The Inspector smiled, rather grimly.

"Yes—the sort of accident men get penal servitude for not preventing!" he said, rising. "I must strike out for the hotel—it's getting late."

"I think you'd better spend the night here—there is plenty of room. Gregg will see to you," said Torrance cordially.

Waynill hesitated, and even as he considered the invitation, a long, low howl, inexpressibly eery, floated across the forest, filtering through the casement into the room.

"Yes," said Waynill, all the color suddenly stricken from his face, "I think I'd better stay—and I'll get to bed now. It's just possible that the bloodhounds will provide us a long day's work to-morrow."

Torrance agreed, rang for Gregg, and the Inspector said 'Good- night.'

TORRANCE closed the door carefully behind his guest and took a chair by my side.

"There you have the affair from the official standpoint," he said softly. "I have known Waynill for a long time or he would not have spoken so freely. He has told us something of what I intended to tell you, but his attitude toward the business is very different from mine."

He paused for a moment, thinking. Then, "I wonder what he would do if I told him exactly what happened at the place from which the turf was removed when Stark reached it on Monday morning; if I told him why Stark's horse galloped away, why the turf was cut and by whom; if I told him what happened to Stark, and where I suspect his body lies at this moment. And I could, I know. I saw all that took place at that spot which has interested the Inspector so much." His voice had dropped to an agitated whisper, and he stared before him like a man who sees some fearful vision.

"Herapath, you are my friend," he whispered, and then I realized what an effort of will he must have made to remain so calm, so carelessly interested, so undisturbed, during Waynill's story. "Herapath, you are my friend, but, as yet, I do not even dare to tell you the whole of the thing I saw that morning. It is incredible—unbelievable!" He looked at me with eyes that had become suddenly haggard and almost tragic.

"If I told you what I saw I might come to believe things which, for the sake of my whole happiness and peace I dare not believe."

He stared again into the fire, clenching his hands on the arms of his chair.

"Let the bloodhounds find what they can! Let Waynill find 'Mary' if he can! How can a man find a woman from the portrait of a child? And Lovell? Lovell will be at the other side of the Forest to-morrow."

Then he turned to me suddenly and took yet another photograph from his pocket, a common picture-postcard of the earlier kind.

"Do you observe anything worthy of comment about that picture, Herapath?" His voice was tense with anxiety.

I looked very carefully at the photograph. It portrayed a man past middle age, who stood holding out a handful of small snakes—dangling, distorted things—as though to exhibit them to an onlooker. Over one shoulder I saw slung a small canvas bag, over the other was a square tin box. In the left hand he held a long forked stick. His dress was rough, such as foresters wear. At the bottom of the card was an underline, "Morant, a New Forest Snake-catcher."

But it was the face of the snake-catcher that held my attention after the first comprehensive glance. The face—for vaguely, vaguely, behind, as it were, the keen, clear-cut, wild, aquiline features of the man lay a likeness. It may have been some little chance similarity of one line, one feature merely, or it may have been a resemblance of general effect, but, whatever it was, I knew I had seen quite recently a person or a picture of a person who resembled this snake-catcher. Then suddenly a name rose to my lips.

"Why, it's like 'Mary!'" I said.

"Her father. Anything more?" The anxiety had not gone from Torrance's voice.

I had felt that the resemblance of the old man to "Mary" was less than his resemblance to some one whom I could not name. I thought for a moment and my mind turned to the photograph Torrance had looked at so often during supper. I turned to the mantelpiece, but the photograph had gone. I felt myself entering a maze.

"What have you done with that photograph of the Princess that was on the mantel piece, Torrance?" I asked. "I'd like to see it for a moment."

He took it from behind a queer-shaped barbaric looking clock. "I slid it there when Waynill was wondering where he had seen some one resembling the girl of the locket," he said, and handed it to me.

Then I saw. The Princess resembled the old snake-catcher far more, in that vague, uncertain way, than she resembled "Mary." But now—now I saw how like she was to "Mary," also. I looked at Torrance.

"Then the Princess is the snake-catcher's daughter—and 'Mary' grown ten years older?" I asked.

"Yes," he said, and took the photographs again.

"In that case it was the Princess who dropped the locket —her locket?" I suggested.

Torrance hesitated.

"I do not say that," he answered curtly. I saw that he was overstrung. Plainly, he knew far more of the affair than he had told Waynill or me. It was obvious at any rate that he was shielding, or trying to shield, the Princess. From what? And equally plainly, he feared to tell what he knew until he knew all. I did not press him.

"Tell me what you know when you like—if you want to tell at all, Torrance. Or tell me nothing," I said. "I only stipulate that you use me if I can be useful."

Torrance's grip was very friendly when we said good-night.

"I hope to tell everything to-morrow," he said at my door. "I am only waiting for a certain letter."

TORRANCE and I breakfasted by electric light at half-past seven on the following morning. Early as we were, Waynill was earlier. He had left the bungalow at six o'clock, said old Gregg uneasily, as he brought coffee. He had asked Gregg where his master kept his revolver and had borrowed it.

Torrance looked over at me and smiled.

"He's gone after Lovell," he said, "but he might as well go after a hare or a grass-snake with a revolver and handcuffs. Lovell knows the Forest to an inch, and Waynill's a town- man."

He had no more than finished speaking when Waynill came in.

"He's gone of course," said Torrance. The detective nodded.

"Yes, gone from No-Man's Court. But he's still inside our wire fence," he replied. "Wire fence?"

"Telegraph wires—oh, I shall get him all right. It's 'Mary' of the locket I want to find." He drank off a cup of scalding hot coffee and became more human.

"It's beastly cold out here," he said. "I don't think Colonel Shafto's bloodhounds will do any good at all. It's frozen again and the ground's like iron. I hate the New Forest; it's the bleakest place in England." But, nevertheless, he began to eat expensively procured red mullet with an appetite that was a compliment to the forest air.

"You know, Waynill," said Torrance composedly, "speaking as a student of logic, or say a theoretical detective, in this case, it seems to me you are starting on the wrong side of the locket. You have two photos, one of which you have identified, one of which is entirely unknown. Surely the simple way would be to follow up the clue you have instead of hunting for the clue you merely suspect. Why don't you shelve the 'Mary' picture for a time and work back along Stark's history and among his friends, hunting for a reason why he should be killed or caused to disappear?"

To me, after the discovery of the previous night, Torrance's idea was obvious enough. He wanted to distract the detective's attention from the "Mary" picture at all costs. Sooner or later, he argued, the detective would see the Princess, dressed simply as a country lady, and might observe in her then the faint likeness to "Mary" that he could not see when looking at the Princess in her court dress.

Waynill nodded, rather eagerly.

"I believe you're right, Mr. Torrance," he said. "It struck me that way, just now. I'll think it over from that point of view—after breakfast. I wonder what time the hounds will be here."

WE HAD no more than lighted cigarettes after breakfast when old Gregg, coming in to switch off the electric light, announced that a motor had just turned in off the main road and was on the way to the bungalow.

Waynill stood up.

"Well, the Colonel evidently believes in an early start," he said, and began to study a little plan of the place where the turf had been cut.

But it was not Colonel Shafto and his bloodhounds that stepped out of the motor. It was another kind of bloodhound—a representative of the Daily Post, a lean, self- possessed, youngish individual, with quick eyes and a thin, clever face.

He knew Torrance, for he asked for a cup of coffee almost before he was in the room.

"The first of the vultures," he said, pleasantly enough for a "vulture." "Dropped down from town this morning; hired a car at Salisbury and came across these New Forest tundras to Stoney Cross Hotel, looking for you, Inspector." He seemed to know Waynill also.

He drank the coffee Gregg brought him, lighted a cigarette and produced a damp, smeary copy of the Daily Post for that day.

"There's a column about Major Stark on the fifth page," he said, handing it to the detective. "Column seven. I only got the stuff late last night. Perhaps it will be news to you?"

Waynill looked through the column and passed the paper on to Torrance.

"Is this right?" he asked the pressman.

"Quite; I got the story myself." There was a little pause before he added: "It's plain sailing, Waynill, after that, isn't it?"

Waynill did not reply. He was thinking now, I imagine, how his own clues could be explained away.

It was Torrance who spoke, handing me the paper.

"It is quite obvious to me that Major Stark has either committed suicide or quietly left the country," he said, with an extraordinary certainty in his voice.

The journalist nodded. "Perfectly," he said.

Waynill remained silent. I read the column. Concisely enough it explained that a representative of the Daily Post had learned from reliable sources that, less than a week before, Major Stark had been requested quietly, but very unmistakably, to resign from the two prominent clubs of which he had been a member. With the skillful veiling which decency and the English libel law, demanded, the writer of the column gave "financial affairs" as one of the reasons for the forced resignation. "Card troubles," apparently, constituted another reason.

The representative of the paper had also discovered that Major Stark was so heavily in debt to most of the big bookmakers that the best enclosures on any race-course were practically shut to him until he had settled his accounts. Next came a statement which had an even more ugly look about it—a point-blank paragraph to the effect that the disappearance of the Major coincided remarkably with certain steps which two money-lenders were taking in the matter of money lent to Major Stark on the strength of securities alleged to be forged.

Truly there were grounds for believing that the missing man had either committed suicide or absconded. The column concluded with a paragraph stating that, despite the lapse of time since the actual disappearance, Colonel Shafto's bloodhounds would be employed on the scene that day.

But Waynill looked unconvinced.

"Come, Waynill, who on earth would murder a man on the edge of ruin—and worse?" said the pressman lightly, his inquisitive eye on the detective's face. "I believe you've found a clue or two you hate to part with."

Waynill nodded, as another big motor drove up. It was a man from the Morning Herald. And from then on reporters dropped down thick and fast "precisely like vultures over an ox that the army has left behind."

They interviewed Waynill, they interviewed Torrance, they interviewed me, they interviewed old Gregg, they interviewed one another, some dashed off to interview the Princess, her household and her wolves, they interviewed Torrance's whisky and cigarettes, and one enterprising gentleman who broke into the scullery, for reasons known only to himself, I discovered wandering about the back interviewing (I verily believe) the oil- engine. Finally, Colonel Shafto, his brother, two helpers and three magnificent bloodhounds arrived and were interviewed before they set foot on the threshold.

BUT at about eleven a start was made. Two shoes had been taken from the horse Stark had ridden and sent over, together with a number of articles of clothing and a favorite pair of boots be longing to the missing man, from a relative's house at which he had been staying. Then Colonel Shafto, a gray, grim little man, very quick and erect, explained, not too politely, the rules necessary to be observed when working bloodhounds. Chiefly, the crowd was requested to keep well away behind the hounds and to be reasonably quiet.

I saw that the tense look had come again into Torrance's eyes as, just before the start was made, he watched Colonel Shafto and Waynill talking earnestly together over by the hounds. The detective appeared to be pressing some point, and presently the Colonel seemed to agree. He nodded and turned to his brother, the very counterpart of himself, who stood fondling a grand tawny brute nearly three feet high with a grave face, deep-set eyes and ears so long that one looking at the hound was reminded of a bewigged and aged judge. The Colonel mounted his horse and, riding some yards behind the hound which his brother held in leash, set out across the heather and gorse-patched turf.

We followed at a discreet distance.

"They're going to start at the place where the turf is cut," said Torrance softly in my ear, as we went. We were walking alone together; the pressmen had formed a little crowd of their own.

I felt a sudden surge of curiosity.

"Who cut the turf, Torrance?" I asked on the impulse.

"Gregg," he answered in no more than a whisper. "Gregg and I!"

I think he saw my bewilderment, for he smiled faintly.

"No more questions, Herapath, yet," he said. "You shall know what I know—when I know everything."

And we followed the big hound and his attendants in silence. Presently Colonel Shafto's arm went up and we all halted. They had arrived at the spot that mystified Waynill. The Colonel dismounted, a piece of clothing in his hand.

What followed then was strange and a little sinister. I think most of us then expected the hound to fail. The scent was four days old, at least, and the bloodhound is a very much more disappointing worker than those who have only read of the wonderful brutes in romances would imagine.

Certainly no one, the Colonel least of all, expected the hound to do his work with the extraordinary quickness and precision that he actually did. He nuzzled the boots and odd articles of clothing that Colonel Shafto offered him, put down his intelligent head, made a short eager cast round the patch of cut turf, hesitated for a second, and then, running perfectly mute, nose to the ground, padded swiftly away through the heather. Furiously waving us all back, the Colonel gave the hound some fifty yards start and then followed him at a canter.

For some distance the bloodhound traveled over level ground. He seemed to be going along a rough cattle-path and I felt a queer little kick of the heart as I remembered Waynill's remark that he had found the cigar-case at the edge of a cattle-track. Then the ground tilted, sloping down, and the bloodhound disappeared over the slope. Colonel Shafto followed, quickening his pace.

We had come nearly half a mile, running at the best pace most of us were capable of, and when we reached the beginning of the slope most of us stayed there, panting. Indeed, there was little to be gained by running farther, for the slope continued for nearly a quarter of a mile, dropping gently down to the floor of a wide, shallow valley, then tilted up again and, continuing up for another furlong, reached the level. It was like a very shallow, dry river-bed magnified several times over.

Those who waited where we were standing could see practically everything that occurred within a distance of nearly half a mile—if anything was going to occur. Not one of us, except Torrance, who stood there staring out across the forest, would have been astonished, I think, had the bloodhound suddenly come upon the dead body of Major Stark lying among the heather. All were tense with expectancy. But Colonel Shafto rode steadily on down the slope without a check.

THEN presently a small dark speck sped out from the heather at the bottom of the slope, nose to the ground, and ran silently straight across the bottom of the valley. It was the bloodhound, wonderfully following the four-day trail, and excited little murmurs broke from the knot of pressmen. Torrance was staring through a pair of binoculars and suddenly I heard him draw in his breath with a hiss. Almost at the same second the bloodhound stopped dead at the edge of an expanse of smooth level turf and, throwing up its head, uttered a series of short choky cries, very different from the deep bay my romance-readings had taught me to expect.

And there was no reason why the hound should stop that I could see. It stood at the beginning of about a half-acre of turf so smooth and clear of heather growth as to look lawn-like at that distance. There was a volley of quick questions and ejaculations from the journalists. Then Colonel Shafto rode out from the heather toward that level half-acre. But he also stopped suddenly, some eight yards behind the bloodhound, He slipped from his horse and, turning, began to beckon excitedly. I saw him turn again to the bloodhound, whose cries now had changed to a frenzied howl—a long agonized yell of terror. Colonel Shafto frantically tore off his riding coat, but even as his white sleeves flickered like a waved flag, the hound vanished.

"Good heavens!" I said. "Where's the bloodhound?" Only Torrance remained with me—the rest were running down the slope, shouting.

Torrance took the binoculars from his eyes and, white as paper, faced me.

"Where?" he said, in a sort of whispered scream. "Three feet deep in No-Man's Bog; the quickest and most dangerous quagmire in the forest! Although the bloodhound does not know it, he is following the trail of Major Stark to the very floors of the morass!" His eyes burned like jewels. "And if ever No-Man's Bog bursts and gives up its dead, the bloodhound will arise not far from the body of that card-cheat, roue, swindler and fortune- hunter, Major Stark—food for the bog this four days past!"

I stared, dazed and cold, at the string of reporters running, running eagerly down to that smooth, tempting, lawn-like death- trap at the foot of the hill.

"The end of the trail, indeed!" I said weakly, over and over again; "the end of the trail, indeed"—with a vapid and foolish laugh that I was helpless to check.

Presently they all turned, plodding up the slope toward us. Waynill's face was hard with disappointment, for the bogs hold their secrets inviolate from Scotland Yard as from the rest of the world. And the gray little brother of Colonel Shafto had tears in his eyes, for he had reared the big bloodhound from puppyhood; he had taught it almost all it had known; he had come to love the beautiful brute and at the end of it all he had laid it on the trail to its own death.

I THINK that day's happenings left no doubt in the minds of those who witnessed them that Stark had been engulfed in the quagmire by accident—save only Waynill, Torrance and myself.

Torrance put forward a plausible theory that Stark's horse had shied at the black patch of mold where the turf was cut, leaped over the patch, twisting as he landed—probably owing to a sudden jerk of the bridle—thrown Stark and bolted. Stark may have lain stunned for a time, and then, recovering consciousness, and, perhaps gravely injured, crawled away in the direction of No-Man's Court for help. Missing the way in his dazed state, he had blundered into the bog, not realizing where he was until the treacherous mire had gripped him fast. Colonel Shafto was very warm in support of the theory. Had Stark walked into the bog, it was in the highest degree improbable that the scent would have lain for over four days. But if he had crawled, the scent might have been heavy enough to justify the extreme certainty and confidence the bloodhound had exhibited.

The reporters, also, accepted the theory. It was certainly plausible and, further, lent itself to effective "writing-up" for next morning's paper. Only Waynill, walking restlessly round the room with a puzzled scowl on his face, ignored the theory. He was the last to go.

"Well, Mr. Torrance, I'll accept your theory when I've found 'Mary' and Lovell—if they do not provide me with a better one," he said, on parting. Torrance watched him from the window as he strode away toward Stony Cross.

"HE HATES the forest. It is strange country to him. He did well at the patch of cut turf for a town-bred man, but he will not get much farther. It would be child's play to a black tracker, but to any ordinary detective the secrets of the forest are not easily learned from the trails. And daily the signs that the black tracker would look for are disappearing. Every blade of grass, dead leaf or twisted heather sprig is gradually slipping back into its place. In two days' time any clue which the ground may offer now at that spot will be gone as though it had never existed. And Waynill must look elsewhere for clues."

Torrance came away from the window.

"Well, the letter I am waiting for has not arrived," he continued in a different tone, "and you must be content to wait for the truth until I get it."

I thought of the flamboyant and impulsive promise I had made to ask nothing on the previous evening and frankly regretted it. The ominous disappearance of Lovell, the unquieted suspicions of Waynill, reaching tentatively in all directions, the sinister- seeming descent of the "vultures" of the press, the evil fate of the bloodhound, and, not least of all, Torrance's obvious and desperate sheltering of the Princess, stirred my curiosity to an extremity.

"At least, Torrance, tell me, if you can, whom you are sheltering—and why," I blurted. "You know that I would do any thing possible to help."

Rather to my surprise Torrance smiled a little.

"Very well," said he. "If you will understand that I endeavor to shelter her not from the result of any ill-doing—of which she is incapable—but from official suspicion of ill- doing."

"That is understood, of course," I said.

"Then, unasked, I shelter from that suspicion the Princess Komorzekovna. Because I love her. Listen to me. Before Stark came I had almost won her. But with his coming she changed, withdrew, as it were, into an armor of reserve. She was never less cordial to me after Stark's appearance, but nevertheless she changed. We had been good comrades before; then, suddenly, the sense of comradeship, the camaraderie vanished like a quenched candle- flame. We had been accustomed to take together, with the wolves following, quite long explorations across the forest. The walks ceased. Stark came like a blight to flowers.

"She leased No-Man's Court from him, or rather, from those to whom it was mortgaged. She loves the forest and pays heavily for the house. The rent must have been enough to pay interest on other more doubtful loans than that on No-Man's Court. Stark was attracted to her by the heavy sum his agents had extorted from her for rent, I am sure of that, and he called ostensibly as landlord, enquiring as to her comfort in the place.

"He saw her, and, more important to Stark, he recognized the obvious signs of wealth with which she is surrounded. It was plain to me that, from the first, Stark laid siege not to her but to her wealth. To him, she was no more than an appanage to her wealth. He reversed the lover's order of attraction. He came as a fortune-hunter, nothing more.

"But she seemed not to observe it. She appeared to like the man, to welcome him. Against my will, and bitterly protesting in my spirit, I found myself in the background—more and more and more—until finally I kept away from the place. She seemed content to let me go—heaven knows there was never an overture to indicate that she missed or regretted the old days! And Stark came almost daily. They rode together, walked together, where once I had walked and ridden with her. Oh, yes, I had dropped out!

"Stark and I remained on terms. There was a pretense of friendship. I think Stark considered me too rich to lose touch with. That was all, up to last Monday. And now Stark is dead, and I have new hope." He paused. "Oh, not because he is dead—his death could not alter her feelings to me— but because of the manner of his dying. Herapath, I saw him die—and before he had ceased to breathe I knew that I could hope. Some day you will know why—soon, perhaps."

He picked up his stick. "Come for a walk," he said, in a new, restless tone. "We've got an hour of daylight yet."

HE PASSED out through the casement and I turned to get a cap and, incidentally, my automatic pistol. I had carried it all the morning; indeed, I usually carry it. One of my few hobbies is revolver-shooting, and I think I am entitled to say that it is one of the very few things I can do really well.

It was certain that the wolves of the Princess were given considerable freedom and, although they seemed to be unusually tame, nevertheless one of them at least had attacked Waynill. In any case, the pistol was not inconvenient to carry and there was a remote possibility that it might be useful. As things fell out, I can never be sufficiently grateful I took the weapon.

Torrance was waiting and we set off in silence. Our direction lay toward No-Man's Court. It seemed to me that Torrance's suggestion that we still had an hour of daylight was exaggerated. The light was failing even as we started. There was a somberness about the landscape, a graying pall that darkened slowly. The air was bleak and icy. One could not feel any breath of wind but nevertheless the sense of intense cold lapped about one. It was such an evening as ushers in a bitter black frost.

The rusty heather lay still and silent, there was no motion nor sound from the lonely clump of naked, bark-flaking firs, and the hardening turf rang under our boot-heels like iron.

"The forest in Winter," I said, "is uninteresting until one gets accustomed to it."

Torrance did not answer at first. He was staring intently at a small fir clump before us but slightly to our right. He swung round a little, heading for the trees.

"Yes," he said presently, in an absent voice, "but it has its charm also." He had quickened his pace.

"Gently, man," I said, as we came up to the edge of the firs. "Why are we racing?"

But I knew before I had finished.

A woman in furs was standing among the tree-trunks, gazing out toward No-Man's Bog. She turned suddenly as we came up, a pale, face, set with dark, splendid eyes that, against the cold ivory complexion, seemed huge.

But it was not by that white face I knew her, nor by the wonderful eyes. Her attendants introduced her to me as they rose with pricked ears from where they lay about her feet—four great, gray wolves, yawning elaborately, observing us with oblique, half-closed eyes, without fear as without dislike. A turn of her hand sent them padding a few paces behind her—one, the biggest, it seemed to me, jealously reluctant. But he went, looking sideways at us with eyes that for a moment I saw wide and lambent.

SHE gave Torrance her hand and there was a gladness in her voice as she greeted him.

"To meet you wandering again," she said, "is like opening a long-closed book."

"I had not dared to hope it would ever again be open for me," said Torrance, agitated. "The flowers we put among its pages I thought were dead."

She smiled—a little, tender smile—and looked at me. Torrance presented me and, with one eye for the wolves, I fear, I endeavored to express my sense of her amiability. I found it not easy under the slanting eyes of her gentlemen in waiting.

Torrance spoke again and I fell back a little, affecting—it was no true affectation—absorbing interest in the wolves. One rose suddenly, and its coarse, dark, mane-like neck- and shoulder-bristles stirred as though lifted a little by a puff of wind. The others turned their big heads, looking steadily at him. I gave them all my attention. The brutes fascinated me, and I think they knew it. Against my will I felt my forefinger stealthily pick back the safety-catch of the automatic pistol in my pocket.

It occurred to me that the Princess was talking more and more quickly with Torrance, more and more in earnest. I glanced at them. Their eyes clung to each other's; Torrance's lips were open slightly like those of a man on tiptoe to ask a question. They had forgotten my presence, I believe.

"Oh, men are blind—blind!" she was saying. I suppose Torrance had taken courage to reproach her. "They have no faith, no trust. 'Explain the smile for that man—the look for that,' they say. Ah, jealous! How jealous they are! It is cruel, because of the unhappiness for us. I know—do I not know if any woman ever knew! Have I not paid for my knowledge in the last few months?

"Why did you not wait—and trust, too? I prayed that you would not think ill, that you would be kind and patient. Why, it has been to me as if the sun had never shone since that man came!" Her arm swept out toward the valley of No-Man's Bog. "I can tell you now—now that it is too late. Years and years ago, so long it seems, when I was only Mary Morant, a little wild forest creature, I met another of the forest—a Gipsy, a boy. To me he was beautiful, wonderful, a companion sent me by the forest. And his people roamed the South of England, but I remained with my father always in the forest.

"My father was a snake-catcher. My companion was called Boy Lovell. He would not tell me his Romany name, for he said that as I was not Romany he would leave the tents for my sake when the time came. We were young; young and so happy. We planned our future. What did we know of the future? We loved each other, and we had the forest. I will not tell you of all that, so soon after that man—" again she pointed to the bog. "I could not bear it.

"I DO not know now whether I really loved my Gipsy companion. I remember him as always kind and tender and gay—so gay. And we were just two wild things of the forest. I believed I loved him. He would leave the tents, suddenly, at times, and hurry back to me and the forest from as far as Cornwall—alone, impulsive, hungry to see me, to surprise me:

"And then Stark came home to No-Man's Court—the Starks were richer then and lived there—and saw me. He was always wicked. He was wicked then although he was little more than a boy. He had just left the military college. He wanted to be my companion. I laughed at him. But I sometimes allowed him to walk across the heather with me. He had a camera and took my picture, and showed me how to take his. He put the two pictures into a little locket and gave it to me.

"But in the end—one day—he was insulting and my true companion came out from behind a heather clump like a swift snake and beat him. I had not known Boy Lovell to be in the forest at all. I thought him to be with the tents in Gloucester. He beat Stark terribly—as he deserved—when two foresters saw and came up. They held Boy Lovell and Stark looked at him like an animal before he spoke. Then he pointed to a pheasant which Boy Lovell had flung down when he came out from the heather and swore that, because he had discovered him taking a pheasant from a snare and had remonstrated, Boy Lovell had tried to murder him.

"They found snares on Boy Lovell, of course—a Gipsy must live—and took him to prison. Ah, but how Stark lied! His people were important and powerful in the forest then and Boy Lovell was only a Gipsy. They sent him to prison for five years, and because I and my father tried to help him, to speak well for him, my father was dismissed and a new snake-catcher came.

"So we left the forest and went into a town. I welcomed that, for to be in the forest when my boy was in prison hurt me so. He died soon. He loved the forest—he had never slept under a roof—he loved the forest and he loved me. But they did not understand his spirit. One week in prison was to him more than five years would be to many men. They kept him there inside the walls. He could not come to the forest and to me, and so he died—my boy, my companion of the forest, who had been so kind to me—who had been so gay!"

The Princess paused for a moment. The forest was all gray now, and under the firs it was full of shadow. The lights in the eyes of the wolves were plainer and all the brutes were standing up, their heads hung low. The Princess had forgotten them, I think.

"In the town we nearly starved until the snake-woman of a traveling menagerie was killed by a cobra from which the fangs had not been removed. I heard two men talking of it and I hurried to the menagerie, hungry, eager, poor little wretch that I must have been, and begged them to let me be snake-woman instead. I did not fear the snakes—a snake-catcher's daughter who had handled vipers. They listened, and so I be came the snake-girl, and wandered with the caravans.

"But I despised the snakes and learned to understand the animals—the wolves, the leopards, the lions, and presently became a 'Lion Queen.' Oh, but what a 'Queen'! And after a few years I grew famous in my way. It was because I was not afraid. I was never afraid after I knew my companion was dead.

"So I drifted to the Continent, in time to Vienna, performing with leopards and lions and my wolves. I kept the locket with the picture of the man who had killed Boy Lovell with lies. In Vienna Prince Komorzekovna saw me and fell in love with me. I do not think I loved him, but he was so kind and urged me so, and I married him. It made the Prince happy and I was not unhappy.

"At the end of three years he died, and I came home. I heard that the Starks had become poor, and I took No-Man's Court. I had never forgotten to hate Stark—he was a Major now—and I wanted to avenge Boy Lovell. My heart was quite empty then. I thought that if I could meet Stark again I could make him suffer. I hoped to lure him. I was rich and he was poor and greedy. Oh, I had agents who found out many things about him. I had grown beautiful, and he always pursued a beautiful woman. So I took his house—he did not know me, of course—and waited to see what would happen. Then you, my neighbor, came to see me—" her voice faltered and the wolves stirred uneasily "—and—and my heart was no longer empty."

I heard a muffled inarticulate cry from Torrance and he stepped forward to her. The wolves rumbled softly in their throats. The Princess signed to him to stand still and listen.

"I was happy with you in the forest. Then Stark came, and he loved me, he said. I think he believed he spoke the truth. At least he loved my money. He did not remember Mary Morant. I lured him—lured him—until he was certain that I would marry him. It was not easy for me—you did not understand; but I remembered poor Boy Lovell and I was firm.