RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage poster (ca. 1920)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a vintage poster (ca. 1920)

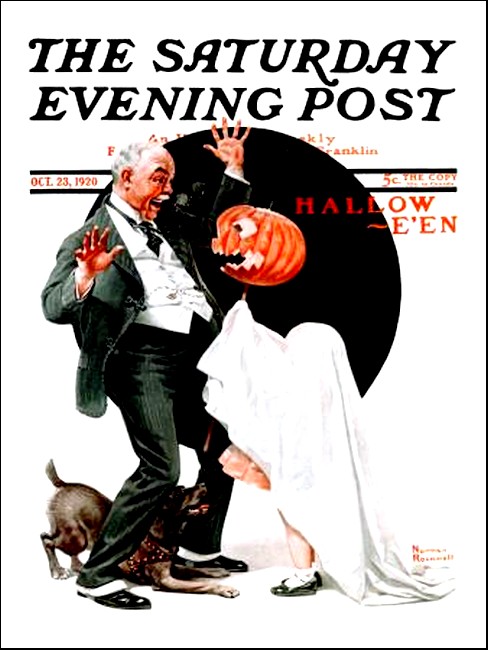

The Saturday Evening Post,

23 Oct 1920,

with the story "Winnie O'Wynn and the Wolves"

THE book Winnie and the Wolves is a novelisation of a sub-set of a series of stories about an impoverished but quick-witted and enterprising young country-girl who seeks fortune and happiness in London. A second novelisation was published in 1925 under the title Winnie O'Wynn and the Dark Horses. The original Winnie O'Wynn stories appeared under the following titles:

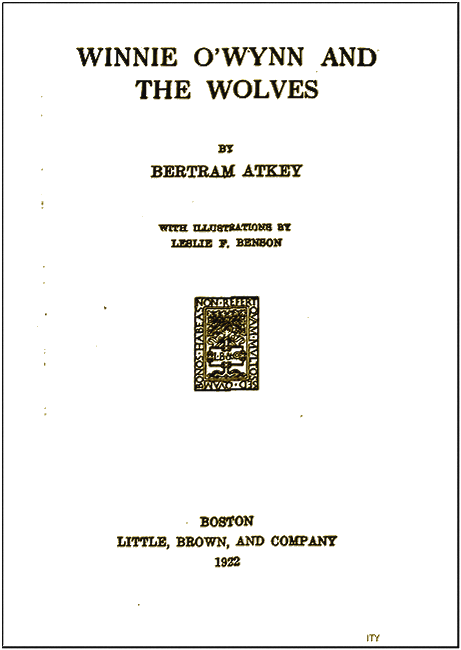

The book Winnie and the Wolves contains four illustrations by Leslie L. Benson (1885-1972). These are not in the public domain in countres with the "Life+70" copyright rule and have been omitted from the RGL edition.

—Roy Glashan, 19 April 2022

"Winnie O'Wynn and the Wolves,"

Little, Brown, and Company, Boston 1922

In which Miss Winnie O'Wynn Picks Peas in the garden, gracefully gathers in a sweet little Posy of Pinmoney, remembers the advice of her Papa and goes all alone to the Great Big Town where Wolves Prowl.

In which Winnie is fain for Millinery, is invited out to Tea by a Grandfatherly Gentleman, and meets with a Young and Innocent Wolf who is permitted to provide Her with a Pretty Hat.

In which Winnie makes the Acquaintance of Mr. George H. Jay, accepts a Position which is guaranteed to be Honourable and arranges to equip Herself for the same.

Wherein It would appear that Winnie somewhat exceeded the Estimate of Mr. Jay, who introduces Her to Mr. Canis Lupus Carter and begs for Information regarding the Old Ivy-clad Rectory which is in His Mind.

In which a Youthful Gentleman basks in the Smiles of Winnie, and Winnie suns Herself in the Golden Beams of Lady Fasterton.

Wherein Winnie tries very hard and rather expensively to do exactly as Mr. Jay wishes, and Lady Fasterton is by no means divorced.

In which Winnie is interested in the Quickness of the Quick Mr. Jay and again ventures recklessly within range of His Carnivorous Activities.

Wherein Winnie is introduced by Mr. "Wolf" Jay to Mr. "Rattlesnake" Slite, is offered a Situation and having adopted a Little Lonely Money, accepts the same.

Wherein Winnie is tried in the Balance, is not found wanting, makes a Friend and hears of the Rust-Red Blonde called "Tiger-Cat."

In which Winnie is positively forced to accept a Matter of a Couple of Thousand Pounds.

In which the Silent Player makes His Move, and a Great Fortune passes so close to Winnie that she hears the rustle of its Pinions as it soars out of Her Reach.

In which Winnie pauses on Her Primrose Path in order to notify Lord Fasterton that She will be Nineteen To-morrow.

In which Winnie introduces a Bookmaker to the Higher Mathematics, instructs Him in the Art of Generosity, and accepts an Invitation to meet a Lady.

In which Winnie finds Her Way to the Heart of a Lady with je ne sais quoi, takes Coffee with Lady Fasterton and the Hon. Gerald Peel, and first hears of Rex the Remarkable.

In which Winnie leaves it, by permission, to Lady Fasterton, is pounced upon by Rex the Remarkable, is tempted by the Steed called Amaranth, learns of the Three Little Maids, Daisy, Lucille and Sara, and calls upon Mr. George H. Jay.

In which Winnie, supported by Her Guardian, faces a Painful Task, performs an Act of Renunciation, gives to Mr. Jay a succession of Shocks and to Bookmaker Ripon Severe Palpitation in his Bank Balance.

In which Winnie holds a Little Seance in Lullabyland with Sir Cyril Fitzmedley and becomes the Owner of a Pet with Possibilities.

In which Winnie goes riding on Newmarket Heath in the Dawn, meets a Tiger-Man, firmly refuses to accept the Handsomest Horse on the Turf and disposes of an Option.

In which Winnie makes Her Debut as Darling of the Maison Mountarden.

In which Winnie takes Tea at the Astoritz, suffers the Babblings of Sir Cyril, readjusts His Outlook and reflects upon the Habits of the Decoy Duck in Its Natural Haunts.

In which Winnie again calls upon the Reliable Mr. Jay, prattles prettily to Felis Tigris Mountarden concerning the Queer Side of Things, and wafts Herself gently home.

Wherein Winnie takes Luncheon with the Hon. Gerald Peel, reminds Mr. Benson Boldre of Queen Anne Boleyn and goes to the Aid of the Ultra- Superba Film Company.

In which Winnie introduces Mr. Boldre to the Ancient Custom of sacrificing to the Gods of Good Luck, and rings up Mr. George H. Jay.

In which Winnie inadvertently intrudes upon a Lady indulging in "a Good Cry", dries those Tears, and sweetly depresses Mr. Sus Porcus Archer's Financial Temperature to Five Hundred Below Zero.

Wherein Winnie, having dined with a Lady who would fain become a Wise Woman, dons a New Pink Silk "Thinking" Kimono.

In which Winnie is asked in Marriage, postpones Her Answer, permits Mr. Boldre to purchase a Jewel Case, and grieves Mr. George Careful Jay.

Wherein Winnie, in Self-defence, surprises Sus Porcus Archer, saddens Mr. Boldre, amazes Lady Fasterton, gratifies Miss Allen and shocks and amuses Mr. Jay.

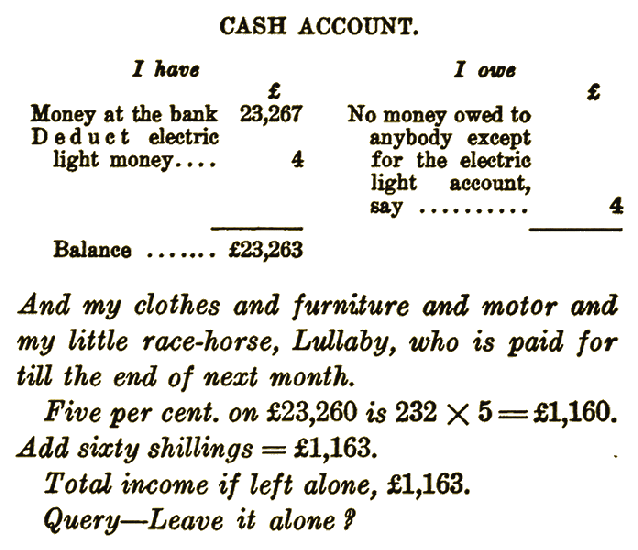

Wherein Winnie gives her Celebrated Imitation of the King in His Counting House and takes a Rest.

In which Miss Winnie O'Wynn, Picks Peas in the garden, gracefully gathers in a sweet little Posy of Pinmoney, remembers the advice of her Papa and goes all alone to the Great Big Town where Wolves Prowl.

WINNIE was picking peas in the garden just beyond the strawberry bed and she looked so sweet and dainty in the old sun-hat that even the blackbirds would have faltered in the havoc which they were industriously working among the late berries had they not had other things to think about.

The doctor came absent-mindedly down the garden path, lost no doubt in grave reflection upon the best method of prolonging Lord Alquoholl's highly remunerative gout, and saw Winnie there. For a moment he watched her pretty hands flit pinkly among the pods, then he glanced, by no means absently, at the house.

The glance was necessary, for his wife was in the morning room counting up her "accounts rendered."

The doctor stepped into the pea-tangled green corridor and smiled at Winnie.

"You look charming, Miss O'Wynn—pos-i-tive-ly delicious. Let me help you pick the peas."

His method of helping her pick peas was quaint. It began, apparently, by the quick passing of his arm around Winnie's waist, the bending of his brown, handsome face to hers, and a smiling whisper:

"I love you, Winnie. Be mine, sweet maid, and let who will be clever."

"Sir!" said Winnie, and pushed him. He lost his balance and fell among the peas. But he regained his feet without difficulty, and he still smiled.

"How unkind you are to me, Winnie. Have you forgotten how well I cured your influenza?" he reproached her. "I can't help loving you, child."

But Winnie was not responsive.

"Your wife is looking out of the window of the morning room," she said. "Why do you insult me when I come into the garden? I shall leave." Her glance did not waver; she looked like a flower that had inadvertently grown among the peas instead of the pansies, fair and cool as a slender pink-tinted blossom. "Your wife is looking out of the window, Dr. Fennel, and if you do not lend me twenty pounds I shall tell her of this insult."

The jaw of the frolicsome young doctor fell and his eyes rolled a little.

"I—I beg your pardon, Miss Winnie—what was that?"

"Twenty pounds. A loan. If you do not lend it to me I will go to Mrs. Fennel and tell her that I am compelled to leave her because the garden is not safe—on account of your unwelcome but persistent advances."

The doctor gasped.

"But it's blackmail, child—you can't do this sort of thing. It was a joke."

"I have eighty pounds," said Winnie, "and of course I want to make it into a hundred. Wouldn't you want to if you had eighty pounds?"

Her blue eyes were like forget-me-nots, thought Fennel, sadly realizing that he would forget them not for a long time to come, and her face was as tranquil and innocent-looking as that of a small child.

"It's ridiculous—impossible, Winnie," he protested.

Winnie's clear, silvery voice rose from among the pea-sticks. "Mrs. Fennel!"

"No—shut up, child—for God's sake," hissed the doctor.

"—Dr. Fennel says that—"

"Be quiet, you little fool—I'll let you have the money—"

"—that the peas are small and few in the pod. Shall I go on picking?"

Mrs. Fennel glanced up from her "accounts rendered."

"Try to find enough for lunch," she called pleasantly, then, perceiving the proximity of her husband to Winnie—her nineteen-year-old lady-help-guest-maid-kept-companion —added, less pleasantly, "Jack! I want you."

"Jack" moved out of the pea patch and went slowly up the garden path, fighting a losing battle against some deep strong instinct which seemed to tell him that twenty pounds would shortly pass into his pass book—debit side.

Winnie O'Wynn went on picking peas. She smiled softly as she picked, and presently she began to sing, an airy trifle of Swinburne's all about some butterflies somewhere—

"Fly, butterflies, out to sea...

Frail, pale

wings for the winds to try...

Fly, butterflies, fly."

It came sweetly in through the window of the morning room, and both Fennel and his wife listened.

"Pretty, happy little thing," said Mrs. Fennel, with a sigh. "She sings prettily. 'Fly, butterflies, frail, pale wings.' Don't you see them, Jack, flying out to sea?" (Mrs. Fennel was literary and very artistic.)

"Eh—oh, yes—I see them, certainly," said Jack Fennel. But they were no butterflies which he saw—flying out to sea. They were Treasury notes—a perfect flock of them—and, frail and pale though they might be, they were strong enough to fly for ever out of his reach into that of Miss Winnie O'Wynn.

Jack Fennel was very much deceived in Winnie, but he really matters very little, for Miss O'Wynn, having satisfactorily achieved the hundred pounds which she had long been aiming for, left the village a few days later and settled down in that Mecca of her dreams,—London.

For some months past Winnie had worked steadily towards that glittering destination.

For she was possessed of an instinct that London was really the only place where one can get on quickly, and in addition to her instinct she possessed also a very clear memory of the advice which her late father had left her—almost the only thing he had left her—when, apparently utterly discouraged by the very worst flat-racing season he had ever experienced, and with the valves of his heart gone almost completely out of action, he turned his face to the wall and left the flat-racing to other gay plungers. He had been a younger son, cut off on his marriage to the nursery governess of whom Winnie was an exquisite replica, and though he disliked the thought of leaving Winnie to look after herself, nevertheless that pang of regret was blunted by the knowledge that few girls were better capable of taking care of themselves. He had treated her very much as a "pal" since the death of her mother and during the few years preceding his own, and though he suffered from a strange and fatal incapacity to pick winners, he was a shrewd, experienced and broad-minded man of the world.

"Remember, Win, old man," he had said during their last talk, "if ever you find yourself really seriously up against it, go to my people—the Quennings. They're not much of a crowd, but they have plenty of money and they can't do less than see you through. We've had a pretty good time, Win, during the last few years, but it's cost money and I don't think there's much left. Everything is more or less mortgaged, so take what you want while you can. The money-lenders will be down on the place like wolves any day—and the creditors will make a fuss for they will have a nasty shock. Your mother's jewellery is intact. Take that and—anything else you can get. I've no anxiety about your future. You're shrewd and you're extraordinarily pretty—your mother over again. Never lose your head, and remember that to a pretty woman wine is the most treacherous friend in the world. Remember that, Win. I've taught you that: never forget it. I'm leaving you to face a social system that isn't worth a fraction of what it used up in the making. You'll find that most people have hearts but are afraid to use 'em—which means that they might as well be without. Be careful of all men. They're wolfish—some because they can't help it, more because they don't want to help it. Be on your guard, therefore, against all men. Trust no woman. You will, of course. You're bound to. But she'll probably let you down. You will be able to stand that, however—if you have not trusted any man...."

He had paused, reflecting.

"Yes, I think you'll be all right, child. Don't forget what I've said. Ca' canny with wine, men and women. Trust nobody but yourself—until you have proved them. But be sure you have proved them. You will be pursued—with that face—but I think you know how to handle pursuers. Be ruthless with them—they would be ruthless with you. And remember that my people, the Quennings, hate publicity above all things. That's your last weapon, Win, but you will probably never need it. If you do, use it for all it's worth. Be as merciless to them as they were to your mother."

Then keen pains had racked him and he had turned wearily.

"Now, kiss me, little woman—and I'll join your mother."

He spoke as though the mother were in the next room, and an hour later he had joined her.

Winnie had never forgotten his advice.

Pelham O'Wynn had left even less behind him than he thought. And the money-lenders had been so quick and capable that Winnie had barely time to get everything really valuable out of their reach before they pounced. Had it not been for a neighbouring young farmer who was a very willing slave to her, she might have lost practically everything. But his horses were strong and instantly available, and there was room in his barns for much.

So that when presently Winnie, with her hundred pounds in cash, and her five hundred or so in jewels, found a cosy unfurnished flat in the neighbourhood of Russell Square it needed only a line to the agriculturalist aforesaid to bring her furniture to her.

He proposed to her, of course, was kindly refused, patted on the head and sent home to his mother.

And Winnie was alone in London.

She had worked busily all that day and was tired. So she cooked herself a small grey mullet, made tea, cut bread and butter, opened a tin of peaches and dined in her kimono. Then she took a cigarette to the couch and, lying comfortably, reviewed her situation.

She considered it from all angles and was satisfied with it.

She was going to get on. How was not instantly apparent. She had the usual accomplishments but no special training. She was qualified for no particular work. She had a gift for dressing, and she was very pretty. But there are thousands of girls who have those advantages,—which by many are considered highly risky advantages.

But Winnie O'Wynn had two other assets which modified the risk. One was a clear-cut, cool, quiet courage that rendered her impervious to any kind of fear; the other was the possession of plenty of brains and few scruples.

That, she decided, was what it all amounted to,—her beauty and her brains versus The World.

She dropped her cigarette end into an ash tray and, smiling, loosened a strand of her heavy, reddish-gold hair.

"Winnie O'Wynn versus The Earth!" she said. "Why, it's what poor daddy used to call a 'one-horse snip!'"

Then she spent half an hour over her hair, and having looked with a leisured, lingering delight at the beautiful little nightdress—a scrap of a thing in pale turquoise georgette—oh, yes, very attractive—with the purchase of which she had celebrated her arrival in town, she slipped it on, and so to bed, to sleep instantly.

She looked like a child as she slept her dreamless sleep.

In which Winnie is fain for Millinery, is invited out to Tea by a Grandfatherly Gentleman, and meets with a Young and Innocent Wolf who is permitted to provide Her with a Pretty Hat.

ONE of the first things Winnie did was to see what London had to offer her in the way of millinery.

She needed a hat—several hats—quite a lot of hats, she felt, but she also felt that she did not care to deplete her store of money by paying for hats. And that being so, it naturally follows that she saw a very charming hat at the first milliner's before whose display she lingered, a dream in an odd, new, dark green. Very simple—the price four and a half simple guineas.

She studied it.

Once she interrupted herself in order to drive away a well-dressed man who stopped at her side, peered at her face and suggested that it would be an act of grace on her part if she would deign to bestow upon him the boon of her company at tea.

She looked at him, her eyes wide with wonder.

"No, thank you," she said, smiling. "You are very kind, but you are so old and you look so jaded and worn. I am so sorry for you, and I think you ought to be resting quietly at home. I am going to dinner with my grandpapa—you are so like him, you know, that it would be rather tiring to take two meals with grandpapas. Besides—do forgive me, but I don't like the way you are dressed nor the scent you use, nor the pointed toes of your boots and the shape of your hat. I am very sorry—and I hope you will find a nice old lady to be your companion for tea."

He appeared slightly disconcerted, stared at the flower-like face under the trim little hat, frowned, hesitated, and went away. She was a novelty to him, but not the kind of novelty he wished to cultivate.

Another man went past, with a peculiar sidelong look,—a younger, very well-groomed lounger, with bold eyes, and clothed in beautifully cut navy blue. His pace slackened suddenly.

Winnie's face hardened ever so little.

"Daddy was right," she said. "What wolves they are. One has to defend oneself incessantly."

She stopped a crawling taxi.

"I engage you," she said, with a look and smile and a gentle caressing touch of the arm that melted the black-a-vized tough at the wheel into a surprised grin. "You will wait here, won't you? I shall send out a parcel by the assistant to be put into your car, and I want you to take it at once to Miss O'Wynn, 28, Ady Street. You need not wait for me. Here are five shillings. If she is out leave it with the caretaker, Mrs. Bean."

"Eight, miss," replied the petrol pirate.

She turned, resuming her study of the hat.

"Such a sweet thing, isn't it?" came a trickle of honey over her shoulder.

"Oh, perfect—but so expensive," she said absently.

"How kind it would be of you to accept it from me as a little souvenir," continued the even, persuasive voice.

She turned. It was the beautifully dressed lounger in navy blue.

"A little souvenir," she said, smiling. "Very well. But it is you who are kind—to give me so nice a present."

His eyes gleamed as they went into the shop, tried on and bought the hat.

"Will you put it into my taxi, please," said Winnie to the assistant who brought it to her, packed.

"Certainly, moddam."

The assistant disappeared while the benevolent gentleman handed over the necessary notes to pay.

When they left the shop the taxi had gone. Winnie glanced around swiftly, frowned for a second like one who makes a swift mental effort, then smiled full upon a big man who stood halfway across the street upon a traffic island,—a big man, in City clothes, with a red, gloomy face.

He received her smile with a look of sheer amazement.

"Go—go!" whispered Winnie, urgently to the hat buyer. "My husband—he would misunderstand and make a violent scene."

"But where—where can I see you?"

"I will telephone—quick—what is your number?"

"Ninety-nine Leeward—ask for Captain Dunnwell—dear!"

He moved away, raising his hat as the big man came up. But Winnie was smiling across the street at some one behind the big man. He perceived it, and a look of extraordinary sheepishness appeared upon his face. But he persevered feebly.

"Did you want me, madame—you—er—smiled."

"Sir!" said Winnie.

The red-faced man wilted like a dying dahlia. He was too far West to feel confident. Throgmorton Avenue was his favourite environment.

Winnie gave a faint shrug, and called a taxi.

"What wolves men are," she said, and had herself driven away with speed from such a highly objectionable place.

"One must fight them with their own weapons," she said, as she opened her cigarette case. And the sweetness of the hat drove the telephone number out of the pretty head quite satisfactorily.

In which Winnie makes the Acquaintance of Mr. George H. Jay, accepts a Position which is guaranteed to be Honourable and arranges to equip Herself for the same.

FROM all of which may be gleaned a tolerably clear idea of the lines along which Miss O'Wynn proposed to succeed in life. She was quickwitted. If the big, red-visaged man had not been in evidence she would have thought of something else. She used the big man because he was obviously usable. She used the navy-blue clad man about town because he had insulted her. She retaliated his insult by fining him a four and a half guinea hat. And, as she told herself, smiling angelically at the mirror, he was a wolf, ready and willing to eat her up with one bite. It served him right.

"How cruel and merciless men are," she said to herself, as she turned to survey the hat from another angle. "They pounce on one like great, fierce hawks. Daddy was right. A lonely little girl like me has to be so careful—like a mouse hiding among the cornstalks away from the owls.... Ye-es, it goes well with my hair! Awfully well."

That evening she gave up to a long and careful consideration of her plans. Her original idea, when planning her future while "lady-helping" Mrs. Fennel, had been to seek a position as typist in an office or pianist in a cinema cellar and so settle down to save money. This idea, since the wolf-like conduct of Doctor Fennel, had been gracefully but swiftly receding into the never-never.

Winnie did not care for work for work's sake, and she felt that pounding the keys of either a typewriter or a piano was not a swift method of increasing her hundred, to a thousand, which gentle project was looming large in the exceedingly active mind that worked under her great pile of beautiful hair.

Nevertheless she glanced through the Evening View advertisements rather idly, as she sipped a cup of chocolate, in case any demented millionaire wanted a typist or secretary at about a thousand a year, and so came upon the following advertisement:

### Quote

"Wanted, young lady for confidential work requiring no special training. Must be fair-haired, blue-eyed, not over five feet four inches, good complexion. High salary. Call 11 a.m. George H. Jay, 9, Finch Court, Southampton Bow, W.C."

Winnie smiled. She fitted that advertisement so well that it might have been written round her. She decided to accept the position. It did not appear to occur to her that she might not get it offered to her,—for Winnie was no pessimist.

At eleven o'clock next morning Finch Court was practically full of petite, fair-haired ladies with good or pretty good complexions. They were from six feet to four feet tall; evidently some were as poor judges of height as they were good applicants for high salaries. Their hair ranged from grey to orange,—fair, that is.

Winnie, strolling up at about eleven-twenty, turned into Finch Court and stopped abruptly. She perceived at a glance that this business was going to be a scramble, and as she did not care for scrambles she smiled and turned abruptly—into the arms of a fat man in a racy silk hat and grey frock-coat suit. He had a good-humoured, jolly sort of face, though his eyes were hard and glassy.

He started a little as Winnie collided with him.

"I beg pardon—" he began in tones of surprise, then checked himself.

"Are you calling in reply to the advertisement?"

"Oh, yes," smiled Winnie. "But it is so crowded, and as I really don't mind whether I have the position or not, I was coming away."

"Don't do that, miss. It's yours. You've got it. You 're engaged. I'm a quick man. I'm Jay. George Jay. If I interviewed a thousand ladies I should never find any one more suitable than you."

He took out a handkerchief, removed his hat, mopped his forehead and laughed very loudly indeed.

"I knew I should be lucky. Saw a black cat last week. Ran over it, in fact," he bellowed. "Come into the office."

He made his way up the court and called loudly to the fair-haired bevy.

"Sorry, ladies. The position is filled."

They began to pour out of the court instantly, and the fat man turned into an office, the windows of which were inscribed "Geo. H. Jay. Agent." No information was supplied concerning the person or persons, thing or things, for whom or which Mr. Jay acted as agent.

"This way, my de—miss."

Winnie entered a comfortably furnished office on the first floor and took the chair which George H. Jay offered her. She wondered whether he, too, was a wolf. She fancied he was not; but with jolly-faced fat men one never knew.

He looked at her closely and a great satisfaction dawned in his eyes. He beamed.

"Do you mind if I ask you what is the salary, please?" inquired Winnie, her innocent, lovely eyes very wide and anxious.

"Oh, very good—very good indeed, Miss— Miss—"

"I am Winnie—Winnie O'Wynn, you know."

"Dear me, that's a very pretty name, Miss O'Wynn. The salary is—er—ten pounds and all expenses."

"Are there any duties, please?" asked Winnie naively.

George H. Jay blinked slightly.

"Well, sure! That is—they're very light."

"Are they honourable, please? Do forgive me for asking you that, Mr. Jay—but a lonely and unprotected girl has to be so careful."

Mr. Jay stared intently at the lovely child-face turned so eagerly towards him and he winced a little.

"I will tell you the duties and you shall judge for yourself, Miss O'Wynn," he said, and added quickly, "If I were a married man and had a daughter, no doubt she would be about your age, and one thinks of these things, of course, of course."

It did not sound translucently clear, but that wincing, flinching look of discomfort had not escaped those blue, blue eyes. Winnie mentally filed it for future reference.

"You will be required to occupy a room in an hotel at Brighton on the night after next. That is all. I myself will escort you there and call for you in the morning. You may choose your room, examine it, lock it and keep the key. I will guarantee that you will sleep as safe and sound there as in your own home. Nobody will interfere with you, annoy you, or even attempt to speak to you from the moment you arrive till the moment you leave. That's a guarantee. If it is not kept to the strict letter you are free to call the police or any one you like to care for you. The fee which will be paid to you for this simple service is—come now—ten—no, say twelve pounds—call it guineas."

"Oh, but that is awfully easy. Shall I be taken down in a motor?"

"Certainly," said George H. Jay, smiling.

The sweet lips drooped.

"Oh, but I haven't a motor coat, or bonnet, or anything. It will be very expensive."

"That will come under expenses," said Mr. Jay, laughing extremely loudly.

Winnie smiled.

"How pleasant it will be to work for you," she said impulsively.

"Well, I'm not mean—no, you won't find us—me—mean."

Her face fell.

"What is it—what's the matter?"

Winnie's eyes were downcast.

"I'm so afraid that you will be ashamed of my dressing-case. It's rather shabby. You see, I am not very well off and I am saving up for a new one, but I haven't got very far yet. Do you think if I were to put a little money towards it the rest could come under expenses, too? You see, it would be an expense."

Mr. Jay's good humour and generosity seemed unbounded.

"Dressing-case, dressing-case. Oh, that'll be all right. Can't go with a shabby dressing-case, certainly not," he said in his noisy, open, breezy way.

He pondered, staring at her. His gaze was very keen and penetrating. But it fell off like a blunted arrow from a shield from the impenetrable innocence of Winnie.

"Certainly have a dressing-case, child. In fact, it's necessary," he said, "and we won't call upon your pennies for it, either. Look here, go and buy one now—a nice one. Ten pounds, hey? Ought to get a nice one for ten pounds."

"Before the war my father bought me a beauty for fifteen pounds, but everything is so dear now," said Winnie.

A certain sadness crept into Mr. Jay's eyes—a kind of weariness.

"Well, well, choose for yourself and bring the bill to me." He laughed louder than the waves breaking on the shore, but there was not much amusement in his mirth.

"Come and see me to-morrow when you have got suitable things. Anything in reason that is necessary for a lady staying one night at a good hotel you can have. And if you have, or can get, a smart violet evening dress to dine in—why, do so. I will attend to the bill."

He drew a sharp breath.

"Only be human—I mean, be reasonable—what I mean is, don't spend for the sake of spending."

Winnie's eyes widened.

"Oh, that would be wicked. I think that is quite a detestable thing to do. I will be very economical," she promised.

"I'm sure you will, Miss Winnie. That's a good girl." He rose and, excusing himself for a moment, left the room. He closed the door behind him, but the catch failed and it hung slightly ajar.

Winnie rose, widened the gap, and resumed her seat.

In a moment she heard faintly the voice of Mr. Jay speaking upon the telephone. He had subdued his lusty voice, and she only caught a word here and there. But they were useful words—"wonderful likeness... amazing luck, my lord... expense... quite so... yes, my lord... ha, ha... carte blanche... instructions... very good..."

The voice ceased and Winnie got up, closed the door and sat down again, her eyes fixed thoughtfully on the telephone on Mr. Jay's table. Why did he not use his own telephone instead of going into another room? Filed for reference.

Mr. Jay entered, apologizing for his temporary absence.

"Well, my dear Miss O'Wynn, I think everything is clear. Fit yourself up properly—I see you're a lady and know how to dress, and so on. Let the few little things you find it necessary to buy be of good quality—suitable for a lady." He sighed.

"But, as I say, be human about it. Don't spend more than is absolutely necessary. Hard times, you know."

Winnie reassured him, and having promised to return on the following day, she smilingly tripped away.

Mr. Jay resumed his chair and for some moments stared before him, frowning slightly. Once he half rose, then relapsed into his chair again.

"She's as innocent as a child. But I hope she's not as careless.... I ought to have fixed a limit. Thirty pounds—something like that. If she's careless—she might easily spend nearer fifty. That's the worst of these pretty little things—either they're carelessly extravagant—or else they're as rapacious as vampires. And I guess I can provide all the rapacity required in this business."

He grinned.

"However, she's too timid to do much damage. But, all the same, I should have mentioned a limit."

He was right; he should have done so.

It would have been unlike Winnie had she failed to realize that in some mysterious way the Wolves were after her once more. The man Jay, acting no doubt for others, needed her badly, so badly that he was evidently prepared to pay for the privilege.

She called in at the nearest Fuller's, ordered a cup of chocolate and thought it out.

The duty required of her was so exceedingly simple and the pay so high that it would have frightened many girls.

Why was Mr. Jay prepared to lay out quite a large sum of money just to get a fair-haired, blue-eyed girl of five feet four to occupy a room for one night only in a Brighton hotel, and why need she wear a violet dress to dine in?

It was apparent to her that there was nothing to fear. She need only take a good novel, a box of chocolates, keep the light burning all night, see to the lock and key, if necessary pay a fee for a detective to stand on duty all night outside or below her open window, and so, safe, spend a few hours reading.

It was very mysterious. But it was also very easy. No doubt Mr. Jay expected to reap some wolfy advantage out of it; Winnie did not mistake him for a philanthropist. But what advantage it was difficult to see.

And it did not greatly matter.

Winnie glanced at her watch and smiled quietly. She had a great deal of shopping to do and very little time to do it in. She left the shop and took a taxi.

"Please drive me to Regent Street," she said in her caressing way.

Wherein It would appear that Winnie somewhat exceeded the Estimate of Mr. Jay, who introduces Her to Mr. Canis Lupus Carter and begs for Information regarding the Old Ivy-clad Rectory which is in His Mind.

MR. GEORGE H. JAY was not alone when she called at his office on the following morning. Sitting by the window was a tall, excessively slender, well-dressed man of middle age.

He rose as Winnie entered. It was an effective entrance, for she was wearing a thirty-guinea grey costume—new; a three and a half guinea pair of grey suede shoes—also new; grey silk stockings—new, thirty-seven and six; and, of course, the hat which had been so kindly presented to her by the Wolf of yestereve. She carried a grey, gold-mounted soft alligator bag—new; and in the bag were a small bundle of receipted bills and a very much larger bundle of unreceipted bills.

"Let me introduce Mr. Carter, Miss O'Wynn," said the man Jay.

Mr. Carter bowed, smiling.

Winnie decided that had it not been for a certain semi-boiled appearance of his eyes, the pallid hue of his rather weak face, and his air of being out of condition, he would have been tolerably good-looking. As it was, he was far, very far, therefrom.

"And now, with your permission, to business," said Mr. Jay, adding, "Mr. Carter is my sleeping partner, my dear Miss O'Wynn, and entirely in my confidence."

Winnie nodded.

"How nice," she said, and Mr. Carter smiled pleasantly, nodding his head with a mechanical motion that might have been inspired by a couple at the sideboard for breakfast.

"Have you arranged for the few little things you required?" asked Mr. Jay.

"Oh, yes, quite, thank you. Some I paid for myself—and the others will be sent when you have paid for them. I have brought you the bills."

"Ah, yes, you are a business-like young lady, I see. What was the total?"

"It seems to be a hundred and seventy-eight pounds," said Winnie composedly.

Mr. Jay gripped the sides of his chair. His lips seemed feebly to shape the words "Be human," and he gulped very loudly.

"You see, I didn't buy any jewellery," said Winnie. "It seemed top expensive. Besides, I have some of my own." She was taking the bills from her bag. "Those are the receipted ones—will you please pay me now for those?—sixty-two pounds—as I spent all my own money on them. And those are the unpaid ones for you to pay."

Mechanically Mr. Jay took the bills. His eyes were fixed on Mr. Carter. But Mr. Carter's eyes were on the angelic face of Winnie.

Mr. Jay cleared his throat.

"Do you approve, my—Mr. Carter?" he asked, it seemed nervously.

Mr. Carter nodded.

"Oh, quite, quite. Make out the cheques, Jay."

"Certainly, Mr. Carter. At once."

Mr. Jay excused himself for a moment and went out to instruct a clerk to make out the cheques.

"You know, dear Miss O'Wynn, that your little adventure will be quite free from any complication. It will be exactly as Mr. Jay has explained, I assure you of that. I could not sanction it were it in the least likely to cause you any inconvenience," said Mr. Carter.

"I am quite sure that you would not, Mr. Carter," replied Winnie admiringly. "I felt very relieved when I saw you. I could see that you were chivalrous."

Mr. Carter looked surprised but pleased.

"And noble-minded and with great delicacy, honour and generosity. You don't mind my saying so, do you?"

"Not at all, I assure you."

"Some men are like wolves, I think, don't you?"

"Oh, lamentably—I have frequently noticed it."

"And some are just the opposite. They are like shepherds—protectors of the lambs against the wolves, aren't they? Don't you think so, Mr. Carter? I think you are one of the shepherd kind—you would protect any one, I am sure."

Mr. Carter seemed so surprised that he was almost embarrassed.

"Yes, indeed," he said. "If ever you need a protector come straight to me."

"Thank you, Mr. Carter, I will," said Winnie, so innocently that he fully believed the double entente had sailed harmlessly over her head.

But it had not. Things of that kind never sailed over Winnie's head; they sailed instead into her mental notebook, which automatically entered the man who said it as a very wolfy specimen of Canis Lupus.

Her feminine intuition and habit of keen observation through those baby blue eyes had some minutes before summed up Mr. Carter as that "my lord" to whom Mr. Jay had telephoned on the previous day, and who probably was behind the mysterious "duty" for which she was being so well paid.

So she stood up and impulsively offered her hand.

"Shall we be friends, we two?" she cried softly. "Just we two."

"Indeed, yes," said Mr. Carter. "The very best of friends." He seemed quite enthusiastic.

"But, I say, what about that jewellery? You positively must have a trinket or two for the visit. Naturally, what? You must let me arrange that for you. Where do you live, Miss O'Wy—" he broke off as Mr. Jay reentered, apparently much to Mr. Carter's annoyance.

"Well, Jay, well—what is it, now?" he said irritably.

Jay stared.

"Why, my lo—Mr. Carter—the cheques are being written."

"Yes." Mr. Carter remembered himself. "Naturally, what? Well, I'll be cantering along. Remember, Jay, its carte blanche. You will leave your address with Mr. Jay, won't you, Miss O'Wynn, in case we have anything to send—a message, for instance."

He made a rather vague exit, and Mr. Jay settled down to business.

"Tell me, my dear Miss O'Wynn," he inquired, "before we go any further—are you really up from the old, ivy-clad rectory or are you barbed? What I mean is: are you really an ingénue, or is this innocence just your special—er—spiel?"

"Daddy wasn't a rector," said Winnie, rather blankly. Mr. Jay, whose sharp eyes had been piercing her, suddenly laughed his loudest, breeziest laugh, the suspicion clearing from his eyes.

"I see you don't follow me, my dear. That's all right. Forgive me. Keep your ingenuousness as long as you can. It's grand currency, anyway.... But that hundred and seventy odd? Gee! You got to have a natural nerve to hit it up like that—innocent or not innocent. I meant about thirty pounds, you know. However, it's all right."

That was quite true. He had meant her to spend about thirty. But he had meant, also, to charge his client, Mr. Carter (for so Lord Fasterton had chosen to call himself that morning), about a hundred, under the heading of "outfit and preliminary expenses." Still, Mr. Jay did not lack nerve himself, and he had no doubt that he could make up his "loss" by some other gentle little charge.

Winnie had guessed all that from the almost careless way in which he had discussed her pay and expenses during the first interview, and like the gardener who decided to learn the toad to be a toad naturally, she had promptly decided to learn Mr. Jay to be a wolf.

"Yes, keep your pretty innocence as long as you can, my dear child," said Mr. Jay innocently. "It's better than nerve. No crook would have had the nerve to hit it up like that. They're human, some of 'em."

"I don't understand, please," said Winnie.

"That's all right. Now to business."

He gave her the cheques and bills, advised her (quite superfluously) to collect the things as quickly as possible, and then plunged into detailed instructions. They were neither long nor complicated; and within ten minutes everything was arranged and Winnie tripped out.

The clerk who had brought the cheques—a dark-eyed youth, good-looking in the nut or bean style, with be-plastered hair—leaped to open the door for her.

"Thank you so much," said Winnie in her most caressing voice. "You are so kind." She stabbed him to the heart with her blue eyes—for she had an idea that he might be useful—and departed, leaving him convinced that he had made a conquest. He, too, was much more innocent than he knew.

All went with the silken and dream-like smoothness which usually characterized the operations of the shady though breezy Mr. Jay.

He motored her down to Brighton, arriving there in time for her to change her six-guinea dream in motor bonnets, her motor coat (lightly fur lined), and similar sundries, for a really entrancing evening gown in violet, hastily and expensively fitted by Jaquin—the celebrated imitator of Rakuin—from Laquin's. The hotel was small, but smart—entitled The Bijouette—run by a ladylike woman who seemed unnecessarily deferential to Mr. Jay. As Winnie left Mr. Jay to go to her room a telegram was handed her. It contained a profound apology from Mr. Carter for his failure to provide the "trinkets." Insurmountable difficulties had prevented him, but she would find on her return to town that the omission had been rectified.

She dined with Mr. Jay and in due course retired to her room. She had intended to read through the night, but the motor run seemed to have tired her. So she locked her door, went to bed and slept dreamlessly till nine o'clock on the following morning. She breakfasted t with Mr. Jay at leisure and presently drove back to London.

It was about as thrilling as eating mashed potato.

Mr. Jay dropped her at her flat, gave her a ten-pound note, two pound notes and twelve shillings, thanked her, shook her hand warmly, hoped to have the pleasure of putting fresh "business" in her way, and drove off, with a vague appearance of relief.

Winnie took the couch and settled down to think it out. Few people knew better than she that men are not in the habit of spending something like two hundred pounds for nothing.

But it was difficult to see what Mr. Carter and Mr. Jay were getting for their good money.

Winnie made herself a cup of her favourite chocolate and lapsed into reverie, which speedily produced a decision to cultivate the smitten clerk of Mr. Jay.

For, as Winnie told herself rather plaintively: "Those men have taken advantage of me in some way, though I don't quite know how. But I won't be wolfed by any of them—and I must defend myself with the kind of weapons they chose."

In which a Youthful Gentleman basks in the Smiles of Winnie, and Winnie suns Herself in the Golden Beams of Lady Fasterton.

ONE brief tea at a tea-shop, resulting from a chance (he thought) encounter near Finch Court did the business of Mr. Gus Golding, the clerk.

Winnie O'Wynn was an almost irresistible siren at her very worst; but at her best, and when in form, she could have charmed the man in the moon to earth and have persuaded him to take out his British naturalization papers.

And as the adoration of Gus Golding was unhampered by any sort of loyalty to the loud-laughing Mr. Jay, whom the youth tersely described as a "man-eating lobster," it took Winnie perhaps ten minutes to acquire all the information Gus had to give, which was very little, but included the interesting fact that at first sight he, Gus, had mistaken Miss O'Wynn for Lady Fasterton.

"Am I like her, then, Mr. Golding?" purred Winifred.

"Ten years ago she might have held a candle to you, Miss O'Wynn—but not now. She's your style, but she's got to make up pretty much to come anywhere near you now."

Winnie gave him a smile—not for the compliment, which was ordinary—but for the information which, to her quick wits, was extraordinary.

Light began to show dimly at the end of the tunnel of mystery into which she was peering. She gathered that Mr. Golding had very little information to add to the facts that Lady Fasterton (whom he had seen only once) resembled Miss O'Wynn, that Mr. Carter was indeed Lord Fasterton, and that he was wont to employ Mr. Jay upon occasional commissions of the type which would not commend themselves to the family solicitors. Beyond this, Gus knew nothing. So she gently disengaged herself from his conversation and company and sent him back to the office. He had not appeared to possess an inkling of why Mr. Jay or Lord Fasterton had needed the services of Winnie.

But, innocently, he had dropped a scrap of information which, upon consideration, began to grow in Winnie's mind. It was to the effect that Lord Fasterton had recently purchased the Bijouette Hotel at Brighton (through Mr. Jay), thus causing an increase in the office work, which was the only aspect of the matter which interested Gus.

Winnie filed it away in her mind and spent all the following day in making a few inquiries. During her absence Lord Fasterton called at her flat twice. On the second occasion he left a packet. It contained a very sweet microscopic bracelet watch, in gold, with a diamond or two set about it, together with an affectionate little note.

But, save to mark this further evidence of the wolfishness of Lord Fasterton, Winnie was too busy spurring on a private inquiry agent in whom she had invested a few guineas. Lord Fasterton could wait until she was ready to deal with him.

Her diligence and intelligence brought speedy results, and when, some four days after the Brighton trip, she put on the pink kimono (she always thought best in the pink) and, with a vast supply of cushions, made herself comfortable on the huge old couch which was one of the things the money-lenders by appointment to her father had found "magicked" away, she had gleaned sufficient information to give her quite one of the jolliest evenings any lonely, unprotected girl has ever had since jigsaw was invented.

So deftly, indeed, did she fit together the particular jigsaw puzzle of Mr. Jay and the Bijouette that when, on the following morning, she slipped on the Fasterton wrist-watch prior to going out, she regarded it with the almost contemptuous look which one might bestow upon a stone presented to one who is fully entitled to ask for a complete bakery.

She took a taxi to Grosvenor Square and asked for Lady Fasterton.

It was nearly twelve and Lady Fasterton had been up for some time, almost half an hour. Having nothing better to do she received Winnie, who thrilled at her first glance at Lord Fasterton's wife. She was fair-haired, blue-eyed, and five feet four,—very pretty, very much like Winnie, but looking a little more the victim of the strenuous life. At the time Fasterton had married her—off the stage—she must have been a veritable twin sister to Miss O'Wynn.

But she lacked the young girl's vivacity. She was as languid as a slowly drifting curl of mist, or a lily lying upon a still pool.

"Good morning, Miss O'Wynn," she said, smiling faintly. "For a moment I fancied I was looking into a mirror, but I see now that you are younger, fresher, and prettier than I am. But I was like you once." She sighed and leaned back as if exhausted by this long speech.

"You only say that because you are so kind, Lady Fasterton," smiled Winnie, and drew a chair close to the settee. "But I shall try hard to believe it, though I don't think I shall succeed.... No doubt you wonder why I have come to see you. It is because I have discovered a conspiracy against you."

"A conspiracy?" asked Lady Fasterton wearily. "Oh, let them conspire."

"A very serious one," pressed Winnie. "I would not distress you with the particulars, only they have tried to make use of me to aid them."

"They? Whom?"

"Your husband and Mr. Jay."

Lady Fasterton rose. "One moment, dear Miss O'Wynn," she said, and crossed the apartment and opened a drawer from which she took a small gold box. She moved her hands, her back to Winnie, and the girl heard a little inhalation, a sniff.

The drawer closed and the lady returned.

Her languor had gone, temporarily drug-driven away.

"Now tell me, my dear," she said. "Tell me everything and don't mind my feelings."

And Winnie told her in detail all that had happened to her.

Lady Fasterton listened to the end. But her temporary keenness had died out long before Winnie finished, and the story conveyed nothing to her.

"It's all very mysterious. What does it mean—and why do you tell me all this, my dear girl?" she asked.

"Do you want me to speak freely, Lady Fasterton?" asked Winnie. The innocence that characterized her manner with men was not now apparent.

"Certainly."

"Very well; I believe that if the register of the Bijouette Hotel were available to us instead of to Lord Fasterton only, we should find an entry, dated last Monday, which would show that Mr. and Mrs. Jay stayed there on Monday night, and, no doubt, there are several people who would swear to that, and, confronted with you, would swear that you were the lady who stayed there!"

Winnie paused.

"Go on," said Lady Fasterton.

"Have you witnesses—could you prove—where you were on last Monday night?" asked Winnie.

"Cer—" began Lady Fasterton and stopped sharply. A change passed over her face and an odd look flashed into her eyes.

"Ah—I see. I see," she said, half to herself, and faced Winnie.

"No," she said. "I could not."

She leaned forward suddenly.

"Don't misunderstand me," she said, rather harshly. "Let me explain. The state of my health—my nerves—renders it necessary that I should take certain drugs," she laughed. "Oh, call me a drug-fiend if you like—we're always misunderstood. On Monday I was at a place where drugs are obtainable. I was there practically all night. Fasterton knew—or guessed—if he were sober, which is improbable. He slept at his club. But of all the party that was at the place, the drug place, on Monday, there is not one who would admit it, much less swear it in a law court. You see, it's illegal—and scandalous."

Winnie nodded.

"So that if people swore that they saw you at the Bijouette on Monday last, you could only deny it; you could not prove that you were elsewhere!"

Lady Fasterton shrugged her shoulders, "I could not. No, my dear; I'm so sure of the people I spoke of that if Fasterton were to start divorce proceedings—which is the sole reason of this plot—it would not be worth my while to defend it," Winnie thought.

"But you, Lady Fasterton; do you want a divorce?"

"I? Heavens, child, no. Fasterton is one of the richest men in the country. He and I each go our own way. We dislike each other—but that's nothing. Probably Jay suggested this scheme to him—because Fasterton would like to marry Feline—that's the girl who does the weird leopard dance at the Paliseum. He'll be tired of her in a month."

She stared at Winnie.

"But now Fasterton is powerless—as far as this particular scheme is concerned. It's tremendously generous of you to tell me all this, my dear. You see, your evidence would quite ruin their plan. You would give evidence for me, wouldn't you?"

"Of course, dear Lady Fasterton. Would it be very expensive?"

"Expensive, child?" A light dawned on the lady's face. "Oh, I forgot. You are so ladylike that I quite forgot that you have to earn your living. Do forgive me. But that can be put right."

She went to a desk and drew out a cheque book.

"When I married a millionaire I took care of myself, my dear," she said, reverting for a moment to the old stage-days manner. "Mind you do the f$me. Don't trust any man to love you more than a year or two. Tie him down while he's mad for you—in black and white."

She scrawled gigantically across the fair pink face of a cheque.

"There, my dear. It's five hundred. And remember you've a friend in me. You've done me a good turn—I don't want the trouble of being divorced by Fasterton. I've given him no cause, at least, not as much as he's given me, and it would take me a long time to find another husband as well off. Keep this quiet, my dear, and don't forget I'm your friend. Apart from my settlements my allowance is five thousand a year, and your being so much like me might be useful—to us both."

She kissed Winnie.

"Only you're prettier and sweeter and younger, Winnie," she said ruefully.

"Oh, no, dear Lady Fasterton," said Winnie politely.

Wherein Winnie tries very hard and rather expensively to do exactly as Mr. Jay wishes, and Lady Fasterton is by no means divorced.

WINNIE then called on Mr. Jay, for no particular reason than to ask him if he had any more work for her in immediate view, as, if not, she was going to enjoy a week's holiday at Brighton, staying at the Bijouette Hotel, which she liked very much, she said. She met him on the way to lunch, and joined him.

Innocent—nay, even trifling though the item of news appeared to be—it smote the smile off Mr. Jay's mouth like the blow of an axe. Nothing could be more fatal to the gentle plan of Lord Fasterton and himself than for Winnie to become well known to the staff of the Bijouette.

"Oh, I shouldn't go to Brighton, my dear Miss O'Wynn—I heard only this morning that they're expecting an outbreak of influenza there. Why not make it—er—Bournemouth? Fine place, Bournemouth."

"Yes, isn't it?" said Winnie. "But so expensive."

"Expensive—eh? Why, so it is." r. Jay appeared to ponder. Then, with a smile on his lips, but with a sob in his eyes (so to speak) he made a very pleasing proposition.

"I've been thinking during the last day or so, my dear young lady, and, to be truthful, I confess that I paid you too little for that matter you attended to for me. So, if you would prefer Bournemouth—and I advise it—I will foot the bill for you."

Winnie's blue eyes opened.

"But it will cost nearly fifty pounds—to have a really nice holiday there. Daddy stayed there once, and he said how dear it was."

Mr. Jay gasped. He looked as if he wanted to say, "Be human." But he refrained.

"Well, well, I dare say that can be managed," he said, staring at the sweet face before him.

He took out a note-case and counted over five ten-pound notes.

"There you are, my dear young lady," he said. "You needn't mind taking them. You earned them. But it's Bournemouth, not Brighton. That's a promise, eh?"

Winnie put away the notes in her little alligator bag.

"Of course it is, Mr. Jay. Thank you ever so much. I will persuade the friend who is coming with me that I have decided to go to Bournemouth."

"That's right—that's fine," purred Mr. Jay. "A lady friend?" he inquired.

"An old school friend," said Winnie quietly. "Lady Fasterton. Do you know her? I am going to call and see her this afternoon to renew our old friendship, and to try to persuade her to come with me."

The hair of George H. Jay stood straight up on end.

"Who?" he said, his eyes starting.

"Lady Fasterton, Mr. Jay," repeated Winnie, her eyes wide with wonder. "Is anything the matter?"

"You were going to stay at the Bijouette, Brighton, with Lady Fasterton?" croaked Mr. Jay.

"At Bournemouth, now, if she is willing after I have renewed our schoolgirl friendship," Winnie explained soothingly.

"But—you can't, my dear—you simply can't! It's impossible! There are lots of reasons why you shouldn't call on Lady Fasterton."

"But why, Mr. Jay!"

"Oh—excuse me a minute. I've got to telephone. I won't be a minute."

He hurried away.

Winnie smiled and turned to deal prettily with an ice which the waiter had just brought. She guessed without difficulty that Mr. Jay was desperately ringing up Lord Fasterton.

"Such wolves!" she murmured. "How they try to pounce upon one."

"Beg pardon, miss!" It was the elderly waiter.

"I only said what wolves men were," smiled Winnie. "I didn't mean you, of course—it was the others I meant."

"Yes, miss, certainly," said the fatherly waiter rather hazily.

Mr. Jay returned, looking worried.

He sat down.

"Very fortunate business, Miss O'Wynn," he said.

"What do you mean, Mr. Jay?"

"It's too long—and too complicated—a story to explain, my dear little lady. But, strangely enough, I have another commission for you, if you are free. It would be honourable and well paid."

"What do you want me to do?"

"Quite easy. I want some one to go to Cardiff for a month and make a list of all the Evans living there. It's in connexion with a legacy. Could you do that? Only, unfortunately, for certain reasons you would have to give an undertaking not to see or communicate with Lady Fasterton for three months!"

He paused, looking anxiously at Winnie.

"Oh, dear!" A look of pain darkened the blue eyes. "I don't think I would like to promise not to see May Fasterton for so long," demurred Winnie.

"But it's business—business—most serious, my dear child. And well paid."

"How much would you pay me, please?"

A look of sheer agony appeared on Mr. Jay's red face.

"A hundred pounds."

"Oh, I'm so sorry, Mr. Jay. I really couldn't give up my friendship with May Fasterton for the sake of a hundred pounds. It would seem like selling her."

Mr. Jay groaned audibly.

"No, no, Miss Winnie—not at all. It's Business." He drew a deep breath. After all, it was Fasterton's money: he was prepared to spend well for the sake of his divorce. The whole plot depended upon it. If Winnie and Lady Fasterton met it was only a question of time before Winnie spoke of her Brighton trip.

"Look here, what will you do it for?" said Mr. Jay anxiously.

"I don't want to do it, please."

"Do it for two hundred."

"Oh, no, no, please not," implored Winnie.

Mr. Jay ground his teeth.

"Four hundred! Think of it—four hundred pounds!"

"Oh, you tempt me so. I don't want to," sighe'd Winnie.

Beads of perspiration broke out upon Mr. Jay's brow.

"My last word, Miss O'Wynn. I'll give you five hundred not to see or communicate with Lady Fasterton for three months, and to go to Wales for that time."

"I can't—I can't resist five hundred guineas—but I don't want to do it," said Winnie. "You promise?"

"Yes—if I must. I promise."

Mr. Jay drew out a cheque-book and a fountain pen and wrote the cheque forthwith.

Winnie took it and looked at it with aversion, "What a lot of money," she said. "Will they pay me that over the counter, please?" Mr. Jay took the cheque and made it payable to bearer.

"Now they will," he said, with the air of a sorely stricken man.

Winnie began to gather up her things.

"I will go to the bank and get it. Does that seem very greedy, Mr. Jay?"

"Oh, no, not at all," said Mr. Jay with a tortured smile.

He saw her into a taxi.

"Good-bye, and thank you, Mr. Jay," she said. "How complicated everything seems, doesn't it?"

"Yes, very," agreed Mr. Jay shortly.

The following morning Winnie called at Finch Court for instructions about proceeding to Cardiff.

It needed only a glance at Mr. Jay to perceive that Lady Fasterton had acted promptly. He was very subdued.

"Tell me, Miss O'Wynn, did you see Lady Fasterton yesterday?" he asked.

"Oh, yes," smiled Winnie.

"Before you gave your promise, of course?"

"Oh, yes—before lunch."

"Did you tell her about your Brighton adventure?"

"Yes—she was very interested. Why? Was I wrong to tell her? I did not understand that it was to be a secret. You said it was quite open and honourable."

Mr. Jay smiled like a man who has been run over and has just regained consciousness.

"Yes, my dear," he said wearily. "It's all right. Er—did you cash your cheque yesterday?"

"Oh, yes. They paid me without a word."

"Hum! Well, you needn't go to Cardiff after all. That matter is settled now."

"And can I see Lady Fasterton, too, please? Is the promise still binding?"

Mr. Jay hesitated, then with an effort decided to be generous.

"No. Do as you like!"

He waved his hands.

"Everything has fallen through," he said. "Nobody has got a penny out of it all but you. It's too long a story to tell you—but, believe me, your innocence, your pretty prattling ways, have paid you about forty thousand per cent. Keep your innocence as long as you can, my dear—for it looks to me like Good Business."

She shook her head with a puzzled smile.

"I don't understand," she said, rising; "but I'm very happy. And thank you very much, Mr. Jay, for all your kindness to me."

He came to the door with her. He seemed to be struggling internally with something. It came out with a rush as he shook hands.

"Tell me—honest now," he burst out, his eyes searching her very soul. "Are you really Baby Blue-eyes—or are you the cutest little kidder in town?"

But Winnie shook her pretty head.

"Oh, Mr. Jay," she said, most exquisitely confused, "I don't understand," and so was gone.

Mr. Jay watched her trip down the court. Then, shaking his head sadly, he retired into his office, took paper and pencil, and began painfully to figure out what she had cost him, representing Lord Fasterton.

It was a dull way of spending a morning, but it was weighing upon him rather, and he was glad to get it off his mind.

But Winnie O 'Wynn smiled all the way home,—very much as little Bed Biding Hood smiled when the woodman had axed the wolf.

In which Winnie is interested in the Quickness of the Quick Mr. Jay and again ventures recklessly within range of His Carnivorous Activities.

BREEZY Mr. Jay was a gentleman of resilient temperament, and there were few business men in either of the hemispheres who could bear up more philosophically and courageously under other people's losses. Particularly was this the case when the loser was a person so well able to endure a considerable puncture in his revenues as Lord Fasterton.

If Lord Fasterton had failed to divorce his beautiful and good-natured wife, clearly it was his lordship's melancholy privilege to officiate as chief mourner at the obsequies of his stratagems, sleights and devices.

Certainly Mr. Jay did not attach to himself nor Winnie any blame whatsoever for the very disconcerting miscarriage of a carefully worked-out plan.

Nor, indeed, did Winnie imagine that he would. Therefore, it was without any amazement that, a few days later, the child opened a letter from him in which he managed to convey that he would be almost painfully grateful if Winnie could call upon him next morning. He was, he added, in need of just such assistance as his—he hoped he might say "friend "—Miss O'Wynn could give him. It was quite a simple matter, would be well paid, and he would send a taxi for her at ten o'clock.

Winnie put down the letter with a pensive smile.

"Dear Mr. Jay—he always makes the mistake of being too anxious. But then he is a quick man—he said so. I think he wants something else from me. It is a pity, from his point of view, to let it be so obvious. But I suppose that it is because he is so quick."

She laughed—a low musical sound, harmonizing exquisitely with her baby blue eyes—and settled down for a little quiet reflection upon nature and nature study, the wolf department thereof.

For, although she had not been in London a month she had found, as she had expected, that the city was full of those whom it amused her to term "wolves." And now that she was a minor capitalist she was aware of an instinct that it would not be only her slim, wild-flower loveliness which attracted the roving eyes of some of the "wolves." There were, she felt, plenty of them not above closing their teeth upon her capital.

This instinct may have been due to her recollection of certain wise words of that worldly-wise man, her late father.

"Remember, when I am gone, Win, old man," he had once said, "that few men under the age of about fifty can withstand that siren song of which the refrain is 'Something for nothing.' Lots can give the impression that the idea doesn't appeal to them, but you will find them on the telephone next morning, pretty early. That is what they call The Nature of Man. There are others, of course. You can easily sum them up. We'll run through the list. There are:

"1. The men who want something for nothing and usually get it on the reverse gear.

"2. The men who will give something to get a good deal more. (Watch these, Win. Never take your eyes off them.)

"3. The men who are satisfied with what they have. (You won't be troubled much by these, for they are mainly in institutions suitable for them.)

"4. The men who throw away what they have never earned, because they don't know the value of it. (It goes to those who do.)

"5. The men who have nothing, have had it all their lives, and will always have it.

"That about covers the main headings, Win. Classify them as you come across them and treat them accordingly!"

Winnie was doing so diligently.

On the whole she put Mr. Jay in Class 2—the class that had to be watched—though, strictly, he was also fifteen per cent. Class 1.

And nothing happened on the following morning to justify her taking him out of it.

She found him as breezy and decisive as ever. His laugh was as loud and his way was as candid. There was admiration in his hardish eyes as he shook hands and placed a chair for her.

"Good morning, my dear little lady," he called to her across the three feet between them. "I am glad—very glad—to see that London agrees with you so well. You are like a rose in the city, you really are. It is a pleasure to me to see you looking so bonny. Like a rose"—he let his voice die away—"as bonny as a rose—a rose...."

He settled in his chair.

"Now, I wonder whether you have accepted a permanent post, Miss O'Wynn," he continued.

"Oh, no. I am afraid I haven't enough experience, Mr. Jay."

"Well, well, never mind. It will come. After all, you did pretty well out of our last little transaction, eh? Haha! Tide you over for a little, eh? Haha!"

Winnie sighed, her eyes downcast.

"I hope so, dear Mr. Jay."

He smiled.

"Well, well. Now to business. It seems that a great friend of mine is in need of the services of just such a little gentlewoman as yourself. Nothing much—merely to do a little light reading for an invalid. But the lady must be a lady, you understand. Such as yourself. Natural—reliable—charming—young. As I say, such as yourself. He does not want one of those keen, worldly, witty ladies with their future somewhere back in the past, but just a nice, sweet, fresh, innocent little country girl." Here the telephone spurted a metallic jet of sound at him and he turned. "Ah, there's my friend Slite—just a moment. I will tell him you are here."

He did so, briefly, and rang off.

"He's coming around, Miss O'Wynn."

"Thank you," said Winnie. She smiled upon Mr. Jay.

"You are very kind to a lonely little person new to London and a tiny bit afraid of it," she continued. "You know, men are so big and clever and quick, and sometimes they seem so—so fierce that they are almost like wolves, aren't they, Mr. Jay? Don't you find it so, too?"

Mr. Jay screwed up his eyes.

"Wolves—wolves, do you say, my dear little lady?" he said. "Believe me, there are men in this city that would make a respectable God-fearin' wolf lie down and howl. That's so." He spoke warmly, so warmly that Winnie silently wondered what particular wolf was gnawing at his bank account just then.

"But never mind—they needn't worry you, my dear. Keep clear of them—have nothing to do with any of them. It's fierce the wolves there are in this town," urged Mr. Jay.

"I, have anything to do with them? Oh, Mr. Jay!" Winnie shivered.

He nodded.

"I see you haven't changed. Still the same sweet, unspoiled—er—fresh outlook on life. That's fine, very fine. It's nice to meet somebody who isn't mistrustful— watchful—suspicious of their best friends. You want to keep that way."

There were quick footsteps in the outer office and Mr. Jay arose.

"Here's Mr. Slite, my friend. You will like him—very nice—polished man of the world. Not wolfy, haha! Certainly not. Charming man!"

Wherein Winnie is introduced by Mr. "Wolf" Jay to Mr. "Rattlesnake" Slite, is offered a Situation and having adopted a Little Lonely Money, accepts the same.

MR. SLITE entered, a dark, thin person, with extremely bright, cold eyes. He was very pale and might have been anything from thirty-five to fifty. Very well preserved, and most neatly clad in a dark grey lounge suit.

Mr. Jay introduced Winnie, and he smiled pleasantly as he surveyed her. But his eyes remained cold as ever, and though his glance seemed no more than to waver, to flicker, Winnie knew that he had seen her and appraised her in that one flicker from the crown of her pretty hat to the tip of her trim shoes.

He was quick, she saw. Whether he was accurate remained to be seen.

But Winnie had never been slow.

Behind the impenetrable innocence of her blue eyes, the dainty ingenuousness of her sweet, childlike face, her matchless wits had nstantly and unerringly switched Mr. Slite into his correct category.

"Here," flickered the swift intuition of the girl, "here is no wolf. Mr. Slite is not a member of the great Canis Lupus family. By no means. Put him among the rattlesnakes! It's where he belongs. Crotalus horridus—and he's lost his rattle."

She shook hands and fixed upon Mr. Slite the expectant and slightly admiring gaze which the circumstances seemed to her to call for.

"Mr. Jay has been telling me of the poor invalid for whom you wish to engage a reader, Mr. Slite," said she.

Mr. Slite smiled with his lips.

"And do you think that you would care to accept the position, Miss O'Wynn?" asked he in his slow, soft voice.

Winnie hesitated.

"You see, I don't know very much about it yet. I oughtn't to promise until I know, ought I, do you think?"

"No, indeed—haha! That wouldn't be very business-like, would it, Slite?" said breezy Mr. Jay.

"Indeed, no," agreed Crotalus. "I will explain the position. It is quite simple. A client of mine—a valued client—is now growing old and suffers increasingly from failing sight. He has been a great reader, and now that he is no longer able to follow the print for himself he is anxious to engage a sympathetic young lady to read to him. The engagement may be only temporary, as my friend—for so I think I may term him—might go abroad shortly. If you will permit me to say so, dear Miss O'Wynn, you are rather young—"

Winnie's face fell.

"—but fortunately," he hastened to add, "my friend stipulates for a young lady. He lives not far from London, in a quiet way, and he would not demand more than, let me say, an average of three or four hours' reading a day. For the rest you would be free to do as you choose—to play golf, to ride, to motor with his secretary—what you choose. Indeed, it is, in many respects, an enviable post. Have you many relatives? Friends whose advice you could ask?"

"I am quite alone in the world," sighed Winnie.

"Ah! Then I will take it upon myself to advise you, my dear young lady. Accept the position. It is a good one. The salary will be five pounds a week and—everything found. It is a generous salary."

Winnie did not appear to hear the last sentence.

"Please, what is his name?"

"Mr. Cairns Bradburn, of Bradburn Manor, near Woking."

Winnie saw that both men were watching her closely, as though for any indication that the name was familiar. Not a shadow, not a flicker of change appeared on the fair, flower-like face, and the big blue eyes were as steady and calm as the unclouded sky outside. But Winnie's mind had registered the name. She had watched the financial columns of her newspapers pretty carefully ever since she had decided to become a capitalist herself, and she remembered a paragraph to the effect that Mr. Cairns Bradburn, of the Northern High Speed Tool Steel Company, of the Bradburn Shipbuilding Company (1915), Limited, and many other similar comfortable-sounding concerns, had recently retired from active participation in business on account of failing health.

She looked at Mr. Slite.

"I would try very hard to please Mr. Bradburn," she said. "But please, I would like to ask if the proposal is quite honourable, open and aboveboard. Don't be angry with me, Mr. Slite, for asking that. You see, I am a novice in these matters, and I—well, I have to ask that, don't I?"

Mr. Slite's thin lips registered his medium smile.

"A very sensible and intelligent question to ask, my dear young lady," he said. "I like frankness. I believe in it. I am a frank man myself, and so, you see, I can appreciate it in others. Well, you may accept the position without trepidation or anxiety. It is an honourable and straightforward business throughout—I guarantee that."

"And I will add My Own Personal Assurance to Mr. Slite's guarantee, haha!" said Mr. Jay, laughing boisterous approval of Winnie's caution.

Winnie smiled her relief.

"I am so glad."

Mr. Slite cleared his throat.

"I am very glad you asked that question, Miss O'Wynn," he said. "Very glad indeed. For I have yet to inform you that there is a curious condition attaching to the post. Nothing that you need mind—but, to my mind, curious."

Winnie waited. She had long ago guessed that there was a string attached to this attractive position. Mr. Slite was about to produce one end of it.

"It is really very simple—merely that you agree never, in any circumstances, to discuss with any one at Bradburn Manor your parents or your past life. There, that's not a difficult or dishonourable condition, is it?"

She fixed her wide eyes on him.

"Why, no, of course not. In any case, I should not discuss my parents, and my past life has been so unexciting that I don't think any one could possibly be interested in it. I agree, naturally."

Messrs. Slite and Jay did not trouble to conceal their satisfaction.

"You are a very sensible, level-headed young lady," declared Mr. Slite.

Mr. Jay smiled like a proud uncle.

"I told you she was," he said.

"And may I have some, of my salary in advance, please?" said Winnie.

Mr. Jay's smile suddenly vanished. There was, it seemed to him, an odd, familiar sound in that simple little request.

"Why, surely. I think that could be arranged quite well," said Mr. Slite. "How much would you like?"

He took out his note-case.

"Please, I would like six months' salary in advance," cooed Winnie.

A cold surprise gleamed in the watchful eyes of Mr. Slite.

"But, my dear little lady, the engagement may not last for six months!" he explained.

Winnie laughed—the sweetest, naivest, most innocent laugh in the world. It was like the tinkle of a far-off sheep-bell, wafted musically on a gentle wind across a pasture knee-deep in wild flowers.

"Why, that is just exactly why I asked for six months' salary. Just to make the engagement last that long. Don't you see? You see, don't you, Mr. Jay?"

"Oh, yes, I see—haha! Certainly I see," said Mr. Jay rather hollowly.

The two gentlemen exchanged glances.

What Mr. Slite read in his friend's was evident, for he dug reluctant fingers into his notecase.

"Well, well, I will do it. I feel, after our talk, that you will keep the post for that length of time quite easily."

He counted out a hundred and twenty-five pounds, with an air of melancholy, and handed them to the girl.

"There you are then. Forgive me if I suggest that you take care of all that money. Put it in the bank, my dear Miss O'Wynn. You may not know it, but there are men in this city who would not hesitate to rob you of that if they could!"

"Oh, how wicked!" cried Winnie.

Mr. Slite then arranged to call for her on the following morning, and personally to escort her to Bradburn Manor, and, having thanked both men with a very pretty air of profound and even slightly excited gratitude, Winnie went—bankwards.

"Will you please let them put this money with my other money," she purred to the cashier in a voice that penetrated through all the layers of horn and thick armour-like callosities which his work had built up round his heart, clear down to his Inmost Being.

He smiled at the lovely face that had blossomed so suddenly before him.

"Why, of course, Miss O'Wynn."

"Thank you so much. You are so kind."

One of the rosebuds she was wearing broke off and fell on the counter.

She pushed it across to him, with a delicious faint flush.

"Would you like it?" she said. "It's for being kind to a little girl who doesn't understand very well about money matters."

He took it, almost simpering, and slipped it into his buttonhole.

After all, he needn't wear it home, where, if his wife did not notice it, one of his six children certainly would.

Winnie had made another friend for life....

She spent the greater part of the afternoon in her pink kimono, thinking things over.

"Well, it is perfectly clear that Mr. Jay and Mr. Slite need me very badly," she mused gaily. "Or they would never have agreed to pay so well and so heavily in advance. They are such wolves and so clever. I'm sure they mean to take some advantage of me."