RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Sign of the Spider,"

Methuen & Co., London, 1896

"The Sign of the Spider,"

Dodd Mead & Co., New York, 1897

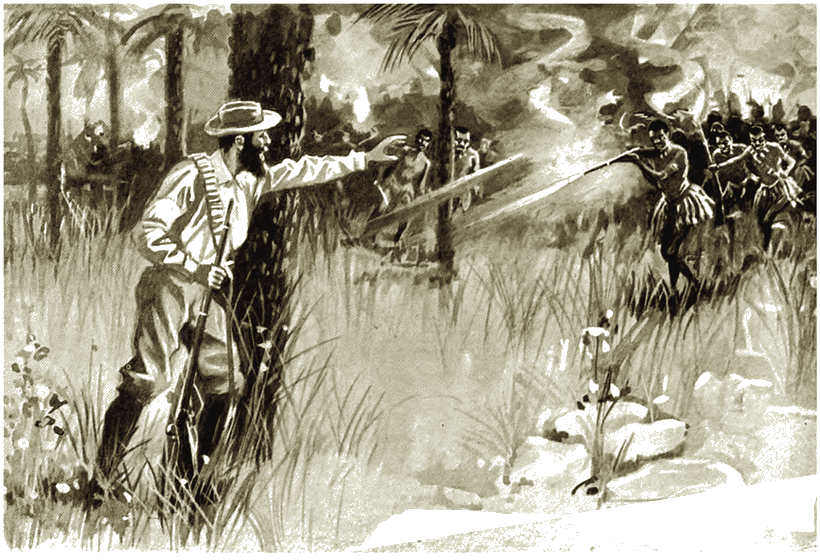

"Don't fire this way... keep the fools in hand."

SHE was talking at him.

This was a thing she frequently did, and she had two ways of doing it. One was to talk at him through a third party when they two were not alone together; the other to convey moralizings and innuendo for his edification when they were—as in the present case.

Just now she was extolling the superabundant virtues of somebody else's husband, with a tone and meaning which were intended to convey to Laurence Stanninghame that she wished to Heaven one-twentieth part of them was vested in hers.

He was accustomed to being thus talked at. He ought to be, seeing he had known about thirteen years of it, on and off. But he did not like it any the better from force of habit. We doubt if anybody ever does. However, he had long ceased to take any notice, in the way of retort, no matter how acrid the tone, how biting the innuendo. Now, pushing back his chair from the breakfast-table, he got up, and, turning to the mantelpiece, proceeded to fill a pipe. His spouse, exasperated by his silence, continued to talk at—his back.

The sickly rays of the autumn sun struggled feebly through the murk of the suburban atmosphere, creeping half-ashamedly over the well-worn carpet, then up to the dingy wall-paper, whose dinginess had this redeeming point, that it toned down what otherwise would have been staring, crude, hideous. The furniture was battered and worn, and there was an atmosphere of dustiness, thick-laid, grimy, which seemed inseparable from the place. In the street a piano-organ, engineered by a brace of sham Italians, was rapping out the latest music-hall abomination. Laurence Stanninghame turned again to his wife, who was still seated at the table.

"Continue," he said. "It is a great art knowing when to make the most of one's opportunities, which, for present purposes, may be taken to mean that you had better let off all the steam you can, for you have only two days more to do it in—only two whole days."

"Going away again?" (staccato).

Laurence nodded, and emitted a cloud or two of smoke.

There rumbled forth a cannonade of words, which did not precisely express approval. Then, staccato:

"Where are you going to this time?"

"Johannesburg."

"What? But it's nonsense."

"It's fact."

"Well—of course you can't go."

"Who says so?"

"Of course you can't go, and leave us here all alone," she replied, speaking quickly. "Why, it's too preposterous! I've been treated shamefully enough all these years, but this puts the crowning straw on to it," she went on, beginning to mix her metaphor, as angry people—and especially angry women—will. "Of course you can't go!"

To one statement, as made above, he was at no pains to reply. He had heard it so often that it had long since passed into the category of "not new, not true, and doesn't matter." To the other he answered:

"I've an idea that the term 'of course' makes the other way; I can go, and I am going—in fact, I have already booked my passage by the Persian, sailing from Southampton the day after to-morrow. Look! will that convince you?" holding out the passage ticket.

Then there was a scene—an awful racket. It was infamous. She would not put up with such treatment. It amounted to desertion, and so forth. Yes, it was a "scene," indeed. But force of habit had utterly dulled its effectiveness as a weapon. Indeed, the only effect it might have been calculated to produce in the mind of the offending party had he not already secured his berth, would be that of moving him to sally forth and carry out that operation on the spot.

"Look here!" he said, when failure of breath and vocabulary had perforce effected a lull. "I've had about enough of this awful life, and so I'm going to try if I can't do something to set things right again, before it's too late. Now, the Johannesburg 'boom' is the thing to do it, if anything will. It's kill or cure."

"And what if it's kill?"

"What if it's kill? Then, one may as well take it fighting. Better, anyway, than scattering one's brains on that hearth-rug some morning in the small hours out of sheer disgust with the dead hopelessness of life. That's what it is coming to as things now are."

"All very well. But, in that case, what is to become of me—of us?"

A very hard look came into the man's face at the question.

"In that case—draw on the other side of the house. There's plenty there," he answered shortly, re-lighting his pipe, which had gone out in mid-blast.

The reply seemed to fan up her wrath anew, and she started in to talk at him again. Under which circumstances, perhaps it was just as well that a couple of heavy bangs overhead and a series of appalling yells, betokening a nursery catastrophe, should cut short her eloquence, and start her off, panic-stricken, to investigate.

Left alone, still standing with his back to the mantelpiece, Laurence Stanninghame put forth a hand. It shook—was, in fact, all of a tremble.

"Look at that!" he said to himself. "The squalid racket of this rough-and-tumble life is playing the devil with my nerves. I believe I couldn't drink a wineglassful of grog at this moment without spilling half of it on the floor. I'll try, anyhow."

He unlocked a chiffonier, produced a whisky bottle, and, having poured some into a wineglass, not filling it, tossed off the "nip."

"That's better," he said. Then mechanically he moved to the window and stood looking out, though in reality seeing nothing. He was thinking—thinking hard. The course he had decided to adopt was the right thing—as to that he had no sort of doubt. He had no regular income, and such remnant of capital as he still possessed was dwindling alarmingly. Men had made fortunes at places like Johannesburg, starting with almost literally the traditional half-crown, why should not he? Not that he expected to make a fortune; a fair competence would satisfy him, a sufficiency. The thought of no longer being obliged to hold an inquest on every sixpence; of bidding farewell forever to this life of pinching and screwing; of dwelling decently instead of pigging it in a cramped and jerry-built semi-detached; of enjoying once more some of life's brightnesses—sport, for instance, of which he was passionately fond; of the means to wander, when disposed, through earth's fairest places—these reflections would have fired his soul as he stood there, but that the flame of hopefulness had long since died within him and gone out. Now they only evoked bitterness by their tantalizing allurement.

Other men had made their pile, why should not he? Rainsford, for instance, who had been, if possible, more down on his luck than himself—Rainsford had gone out to the new gold town while it was yet very new and had made a good thing of it. Two or three other acquaintances of his had gone there and had made very much more than a good thing of it. Why should not he?

Laurence Stanninghame was just touching middle age. As he stood at the window, the murky September sun seemed to bring out the lines and wrinkles of his clear-cut face, which was distinctly the face of a man who has not made a good thing of life, and who can never for a moment lose sight of that fact. There were lines above the eyes, clear, blue, and somewhat sunken eyes, which denoted the habit of the brows to contract on very slight provocation, and far oftener than was good for their owner's peace of mind, and the bronze underlying the clear skin told of a former life in the open—possibly under a warmer sun than that now playing upon it. As to its features, it was a strong face, but there was a certain indefinable something about it when off its guard, which would have told a close physiognomist of the possession of latent instincts, unknown to their possessor, instincts which, if stifled, choked, were not dead, and which, if ever their depths were stirred, would yield forth strange and dangerous possibilities.

He was of fine constitution, active and wiry; but the cramped life and squalid worry of a year-in year-out, semi-detached, suburban existence had, as he told himself, played the mischief with his nerves, and now to this was added the ghastly vista of impending actual beggary. Whatever he did and wherever he went this thought would not be quenched. It was ever with him, gnawing like an aching tooth. Lying awake at night it would glare at him with spectral eyes in the darkness; then, unless he could force himself by all manner of strange and artificial means, such as repeating favourite verse, and so forth, to throw it off, good-bye to sleep—result, nerves yet further shaken, a succession of brooding days, and system thrown off its balance by domestic friction and strife. Many a man has sought a remedy for far less ill in the bottle, whether of grog or laudanum; but this one's character was in its strength proof against the first, while for the latter, that might come, but only as a very last extremity. Meanwhile ofttimes he wondered how that blank, hopeless feeling of having completely done with life could be his, seeing that he was still in his prime. Formerly eager, sanguine, warm-hearted, glowing with good impulses; now indifferent, sceptical, with a heart of stone and the chronic sneer of a cynic.

He was one of those men who seem born never to succeed. With everything in his favour apparently, Laurence Stanninghame never did succeed. Everything he touched seemed to go wrong. If he speculated, whether it was a half-crown bet or a thousand-pound investment, smash went the concern. He was of an inventive turn and had patented—of course at considerable expenditure—a thing or two; but by some crafty twist of the law's subtle rascalities, others had managed to reap the benefit. He had tried his hand at writing, but press and publisher alike shied at him. He was too bitter, too bold, too sweeping, too thorough. So he threw that, as he had thrown other things, in sheer disgust and hopelessness.

Now he was going to cast in the net for a final effort, and already his spirits began to revive at the thought. Any faint spark of lingering sentiment, if any there were, was quenched in the thought that the turn of the wheel might bring good luck, but it was impossible it could strand him in worse case. For the sentimental side of it—separation, long absence—well, the droop of the cynical corners of the mouth became more emphasized at the recollection of that faded old figment, "home, sweet home," and glowing aspirations after the so-called holy and pure joys of the family circle; whereas the reality, a sort of Punch and Judy show at best. No, there was no sentimental side to this undertaking.

Yet Laurence Stanninghame's partner in life was by no means a bad sort of a woman. She had plenty of redeeming qualities, in that she was good-hearted at bottom and well-meaning, and withal a most devoted mother. But she had a tongue and a temper, together with an exceedingly injudicious, not to say foolish twist of mind; and this combination, other good points notwithstanding, the quality which should avail to redeem has hitherto remained undiscoverable in any live human being. Furthermore, she owned a will. When two wills come into contact the weakest goes under, and that soon. Then there may be peace. In this case neither went under, because, presumably, evenly balanced. Result—warfare, incessant, chronic.

Having finished his pipe, Laurence Stanninghame got out a hat and an umbrella, and set to work to brush the former and furl the latter prior to going out. The hat was not of that uniform and glossy smoothness which one could see into to shave, and the umbrella was weather-beaten of aspect. The morning coat, though well cut, was shiny at the seams. Yet, in spite of the wear and tear of his outer gear, with so unmistakably thoroughbred a look was their wearer stamped that it seemed he might have worn anything. Many a man would have looked and felt shabby in this long service get-up; this one never gave it a thought, or, if he did, it was only to wonder whether he should ever again, after this time, put on that venerable "stove-pipe," and if so, what sort of experiences would have been his in the interim.

Now there was a patter of feet in the passage, the door-handle turned softly, and a little girl came in. She was a sweetly-pretty child, with that rare combination of dark-lashed brown eyes and golden hair. Here, if anywhere, was Laurence Stanninghame's soft place. His other progeny was represented by two sturdy boys, combative of instinct and firm of tread, and whose gambols, whether pacific or bellicose, were apt to shake the rattletrap old semi-detached and the parental nerves in about equal proportions; constituting, furthermore, a standing bone of parental contention. This little one, however, having turned ten, was of a companionable age; and to the male understanding the baby stage does not, as a rule, commend itself.

She was full of the racket which had just taken place overhead; but to this Laurence hardly listened. There was always a racket overhead, a fight or a fall or a bumping. One more or less hardly mattered. He was thinking of his own weakness. Would she feel parting with him? Children as a rule were easily consoled. A new and gaudy toy would make them forget anything. And appositely to this thought, the little one's mind was also full of a marvellous engine she had seen the last time she had been taken into London—one which wound up with a key and ran a great distance without stopping.

Being alone—for by this time he had come to regard all display of affection before others as a weakness—Laurence drew the child to him and kissed her tenderly.

"And supposing that engine were some day to come puffing in, Fay; to-morrow or the day after?" he said.

The little one's eyes danced. The toy was an expensive one, quite out of reach for her, she knew. If only it were not! And now her delighted look and her reply made him smile with a strange mixture of sadness and cynicism. And as approaching footsteps heralded further invasion, he put the child from him hurriedly, and went out. Hailing a tram car, he made his way up to town to carry out the remainder of his sudden, though not very extensive, preparations.

Now on the following evening arrived a package of toys, of a splendour hitherto unparalleled within that dingy suburban semi-detached, and there was a great banging of gorgeous drums and a tootling of glittering trumpets, and little Fay was round-eyed with delight in the acquisition of the wondrous locomotive, ultimately declining to go to sleep save with one tiny fist shut tight round the chimney thereof. That would counteract any passing effect that might be inspired by a vacant chair, thought Laurence Stanninghame, amid the roar of the mail train speeding through the raw haze of the early morning. Sentiment? feelings? What had he to do with such? They were luxuries, and as such only for those who could afford to indulge in them. He could not.

THE R. M. S. Persian was cleaving her southward way through the smooth translucence of the tropical sea.

It was the middle of the morning. Her passengers, scattered around her quarter-deck in the coolness of the sheltering awning, were amusing themselves after their kind; some gregarious and chatting in groups, others singly, or in pairs, reading. The men were mostly in flannels and blazers, and deck-shoes; the women affected light array of a cool nature; and all looked as though it were too much trouble to move or even to speak, though here and there an individual more enterprising than his or her fellows would make a spasmodic attempt at a constitutional, said attempt usually resolving itself into five and a half feeble turns, up and down the clear part of the deck, to culminate in abrupt collapse; for it is warm in the tropical seas.

"What a lazy Johnnie you are, Stanninghame! Now, what the deuce are you thinking about all this time, I wonder?"

He addressed, who had been gazing out upon the sea and sky-line, plunged in dreamy thought, did not even turn his head.

"Get into this chair, Holmes, if you want to talk," he said. "A fellow can't wring his own neck and emit articulate sound at the same time. What?"

The other, who had come up behind, laughed, and dropped into the empty deck-chair beside Laurence. He was the latter's cabin chum, and the two had become rather friendly.

"Nothing to do and plenty of time to do it in," he went on, stretching himself and yawning. "I'm jolly sick of this voyage already."

"And we're scarcely half through with it? It's a fact, Holmes, but I'm not sick of it a bit."

"Eh?" and the other stared. "That's odd, Stanninghame. You, I should have thought, if anyone, would be just dog-gone tired of it by now. Why, you never even cut into any of the fun that's going—such as it is."

"You may well put that in, Holmes. As, for instance—listen!"

For the whanging of the piano in the saloon beneath had attained to an even greater pitch of discord than was normally the case. To it was added the excruciating rasp of a fiddle.

"Heavens! Are they immolating a stowaway cat down there?" murmured Laurence, with a little shudder. "It would have been more humane to have put the misguided brute to a painless end."

Holmes spluttered.

"It reminds me," he said, "of one voyage I made by this line. Some of the passengers got up what they called an 'Amusement Committee.'"

"A fearful and wonderful monster!"

"Just so. It's mission was to worry the soul out of each and all of us, in search of some nefarious gift. Oh, and we mustered plenty, from the 'cello to the 'bones.' Well, what is going on down there now is sheer delight in comparison. Imagine the present performance heaped up—only relieved by caterwauls of about equal quality—and that from 6 A. M. until 'lights out.'"

"I don't want to imagine it, thank you, Holmes; so spare what little of that faculty I still retain. But, say now, when was this eventful voyage?"

"In the summer of '84."

"Precisely. I remember now. It was in the newspapers at the time that in more than one ship's log were entered strange reports of gruesome and wholly indefinable noises heard at night in certain latitudes. Some of the crews mutinied, and there was an instance on record of more than one hand, bursting with superstition, going mad and jumping overboard. So, you see, Holmes, your 'Amusement Committee' doubly deserved hanging."

The delicious readiness of this "lie" so fetched Holmes that he opened his head and emitted a howl of laughter. He made such a row, in fact, that neither of them heard the convulsively half-repressed splutter which burst forth somewhere behind them.

"Well, you were going to explain how it is you haven't got sick of the voyage yet," said Holmes, when his roar had subsided.

"Was I? I didn't say so. What a chap you are for returning to worry a point, Holmes. However, I don't mind telling you. The fact is, I enjoy this voyage because it is so thoroughly and delightfully restful. You are not only allowed to do nothing, but are actually expected to perform that easy and congenial feat. There is nothing to worry you—absolutely nothing—not even a baby in the next cabin."

"I don't mind a little worry now and then," objected the other, in the tone and with the look of one who was ignorant of the real meaning of the word. "It shakes one up a bit, don't you know—relieves the monotony of life."

"Oh, does it? Look here, Holmes; I don't say it in an 'assert-my-superiority' sense, but I believe I'm a little older than you. Now, I've had a trifle too much of the commodity under discussion. In fact, I would take my chances of the monotony in order to dispense with any more of the other thing."

Holmes cast a furtive and curious glance at his companion, but made no immediate reply. He was an average, good-looking, well-built specimen of Young England, and his healthy sun-burnt countenance showed, in its cheery serenity, that, as the other had hinted, he was not speaking from knowledge. At any rate, it was a marked contrast to the rather lined and prematurely careworn countenance of Laurence Stanninghame, even as his frank, jolly laugh was to the half-stifled grin which would lurk around the satirical corners of the latter's mouth when anything amused him.

"What a row those women are making over there!" remarked Laurence, as peal after peal of feminine laughter went up from one of the groups above referred to.

"That ass Swaynston, I suppose," growled the other. "Don't know what anybody can see funny about the fellow; he makes me sick. By the way, I haven't seen Miss Ormskirk on deck this morning."

"That'll make Swaynston sick, won't it? Isn't he one of her poodles?"

"Eh? Her what?"

"Fetch and carry; stand up on his hind legs and beg. There—good dog! and all that sort of thing, you know; go to heel, too, when ordered."

Holmes laughed again, this time in rather a shamefaced way, for he was conscious of having filled the rôle whose subserviency was thus pungently characterized by his cynical companion.

"Oh, dash it all, Stanninghame, don't be such an old bear!" he burst forth. "A fellow can't help doing things for a devilish pretty girl, eh?"

"A good many fellows can't, apparently, for this one. Directly she appears on the scene they go at her like flies at a honey pot. There's the doctor, and the fourth brass-button man—er, I beg his pardon, the fourth 'officer,'—and Swaynston, and yourself, and Heaven knows how many more. And one gets hold of a cushion—which she doesn't want; another a wrap—of which the same holds good; two of you strive to rend a deck-chair limb from limb in your eagerness to dump it down on the very last spot in the ship where she desires to sit, what time you are all scowling at each other as though there was not room for any given two of you in the same world. I don't want to hurt your feelings, Holmes, but, upon my word, it's the most d—— ridiculous spectacle on earth."

"I don't see why it should be," was the half-snuffy rejoinder. "There's nothing ridiculous in common civility."

"No, only to see you all treading on each other's heels to do konza to a woman who's nearly losing her life trying not to laugh at the crowd of you."

"Hallo! what's this?" sung out Holmes, not sorry for an excuse to change the subject. "Why, you used a Zulu word, Stanninghame, and yet you say you never were in South Africa before."

"Well, and then? I've once or twice known fellows use a Greek word who had never been near the land of Socrates in their lives."

"Still, that's different. Every fellow learns Greek at school, but no fellow learns Zulu, eh?"

"You can't swear to that. Well, never mind. Perhaps I have been mugging it up as a preliminary to coming out here. Note, however, Holmes, that I used the word advisedly. Konza does not mean to show civility, but to do homage, and that of a tolerably abject kind—in fact, to knuckle under."

"All the same, I believe you have been out here before," went on Holmes, staring at him with a new interest. "Only you're such a mysterious chap that you won't let on."

"Have it so, if you will. Only, aren't you rather drawing a red herring across the trail, Holmes? We were talking about Miss Ormskirk."

"Um—yes, so we were. But, have you talked to her at all, Stanninghame? I believe even you would be fetched if you did."

"H'm—well, I'd better leave it alone then, hadn't I, seeing that I undertook this voyage not for love, but for money? What's her name, by the way?"

Holmes stared. "Her name," he began—— "Oh—er—I see; her other name? By Jove! it's an odd one. Lilith."

"An old one too; the oldest she-name on record, bar none."

"What? How does that come in?"

"Tradition hath it that Lilith was Adam's first wife. That makes it the oldest she-name on record, doesn't it?"

"Of course. What a rum chap you are, Stanninghame! Now, I wonder how many fellows could have told one that?"

"Well, I am a 'know-a-little-of-everything,' they tell me," said Laurence, without a shade of self-complacency. "But, I say, what do these two want bothering around? Not another subscription already?"

Two individuals, armed with mysterious pencil and paper, were moving from group to group, with a word to each. The hawk-like profile of the one bespoke his nationality if not his tribe, even as the pug-nosed, squab-faced figure-head of the other spoke to his.

"It's the 'sweep,'" said Holmes, with kindling interest. "They're going to draw it in the smoke-room. Come along and see it. It'll be something to do."

"But I don't want something to do. I want to do nothing, as I told you just now, and—— Hallo! By George, he's gone!"

One glance at the retreating Holmes, who was making all sail for the smoke-room, and Laurence tranquilly resumed his former occupation—gazing out over the blue-green surface, to wit. Not long, however, was he to be left to the enjoyment of the same.

"Can I have this chair? Is it anybody's?"

He turned, but did not start at the voice, which was soft and well modulated. The two deck-chairs had been backed against the companion, in whose doorway now stood framed the form of the speaker.

Rather tall, of exquisite proportions, billowing in splendid curves from the perfectly round waist, the form was about as complete an example of female anatomy as humanity could show of whatever race or clime. The head, well set, was carried rather proudly, the cut of the cool, light blouse displaying a pillar-like throat. Hazel eyes, melting, dark fringed; brows strongly marked, enough to show plenty of character, without being heavy; hair abundant, curled in a fringe upon the forehead, and drawn back from the head in sheeny, dark brown waves. Such was the vision which Laurence Stanninghame beheld, as he turned at the sound of the voice. Well, what then? He had seen it before.

"It isn't anybody's chair," he replied, rising.

"Oh, thank you," she said, stepping forth. "No, don't trouble; I can carry it myself," she added.

"Where do you want it taken to?" he said, ignoring her protest, and thinking, with grim amusement, how he was about to fulfil the very rôle he had been satirizing his younger friend about, namely, fetch and carry for the spoilt beauty of the quarter-deck.

"Oh, thanks; anywhere that's cool."

"Then you can't do better than leave it where it is," he rejoined, with a quiet smile, setting down the chair again and resuming his own.

Lilith Ormskirk smiled too, but she made no objection, sliding comfortably into the chair, and gazing meditatively at the point of the neat and shapely deck-shoe just peeping forth from beneath her skirt.

"What are they doing over there?" she began; "drawing the 'sweep,' are they not? How is it you are not there too, Mr. Stanninghame? Even those of the men who won't help us in getting up any fun are always ready enough for anything of that kind. Well, I suppose it gives them something to do."

Something to do! that eternal "something to do!"

"But that's just what I don't want—not on board this ship, at any rate," he retorted. "It's a grand opportunity for lazing, an opportunity that can't occur often in life, and I want to make the most of it."

She glanced furtively at his face. It was a face that interested her, had done so since she first beheld it. A very out-of-the-common face, she had decided; and the careless reserve, the very indifference of its owner's habit of speech, had powerfully added to her interest. They had met before, had exchanged a few words now and again, but had never conversed.

"A thing that is a standing puzzle to me," he went on—"would be, rather, if I knew a little less of human nature—is the alacrity with which people waste their precious time in order to make a few shillings. It isn't a craving after profit either, for there can't be much profit about it. Yet Myers there, the Hebraic instinct ever to the fore, must needs throw away the splendid recuperative opportunities afforded by a sea voyage, must needs spend the whole of each and every morning getting up that miserable 'sweep.' It must be the sheer Hebraic instinct of delighting to handle coin—the ecstasy of contact with it even."

"And the other—the one who helps him? He's not Hebraic?"

"No, he's English. Therefore he must be forever 'getting up' something. We pride ourselves upon our solid deliberation, yet we are about the fussiest and most interfering race on the face of the globe."

"Then you don't have anything to do with the popular midday delight?"

"Oh, yes. I hand them my shilling every morning when they come round, and pouch tranquilly later on what they see fit to restore to me as the result of that modest investment."

She laughed, and as she did so Laurence looked her full in the face. He wanted to find out again what there could be in this girl that reduced everybody to subjection so utter and complete. Was it in the swift flash of the fringed eyes, in the sensuous attractiveness of a certain swarthy, golden, mantling shade of colour which harmonized so well with the bright clearness of the eyes, with the smooth serenity of the brow? He could not determine; yet in that brief fraction of a moment, as he looked, he was uneasily conscious of a certain magnetic thrill communicating itself even to him.

"You are stronger-minded than I am," she said. "I'm afraid I bet shockingly at times."

"Well, whenever I do I invariably lose, which is a first rate curative to any temptation towards that especial form of dissipation."

"Look now, Mr. Stanninghame, I'm going to take you to task," she went on. "Why won't you ever help us in getting up anything?"

"But I do help you."

"You do? Why, there was that concert the other night—you refused when you were asked to take part in it."

"But I did take part in it—as audience. You must have an audience, you know. It's essential to the performance."

"Don't be provoking, now," she said, with a laugh which belied the rebuke, for this sort of fencing delighted her. "You never take part in our dances."

"Dances? Did you ever happen to notice the top of my head?"

"I don't think so," she replied, with a splutter of mirth, wondering what whimsicality was coming next. "Why?"

"Only that its covering is getting rather thin, as no self-respecting haircutter ever loses the opportunity of reminding me."

"That's nothing. Look at Mr. Dyson, for instance. Now he might say that. Yet he is a most indefatigable dancer."

"Yes, and that ostrich-egg of his bobbing up and down above the gay and giddy rout is one of the most ridiculous sights on earth. Are you urging me to furnish a similar absurdity?"

"But you might do something to help amuse us. In fact, it is only your duty."

"Hallo! Excuse me, Miss Ormskirk, but that's exactly what that fellow Mac—Mac—something—I never can remember his name—the doctor, you know—was trying to drive into me the other night. I told him I didn't come on board this ship for the purpose of amusing my fellow-creatures—not any—but with the object of being transported to Cape Town with all possible despatch."

"Then you leave the ship at Cape Town? Are you, too, going on to Johannesburg?"

"Not being dead, yes."

"Not being dead? Why, what in the world do you mean?"

"Oh, only that Holmes was asking after all his old friends one night in the smoke-room, and all who were not dead had gone to Johannesburg. Others I've heard talking the same way. So I've got into the habit of thinking there are but two states—death and Johannesburg."

"Tell me, Mr. Stanninghame," said Lilith, struggling with a laugh, "are you ever by any chance serious?"

"Oh, yes; I'm never anything else."

She hardly felt inclined to laugh now. There was a subtle something in the tone—a something underlying the whimsicality of the words, that seemed to quell her rising mirth. Again she glanced at his face, and felt her interest deepen tenfold.

"We may meet again then," she said, her tone unconsciously softening; "I am going to Johannesburg soon."

Meet again? Why, they had only just met; and what was it to him? Yet still more was he conscious of a thrill as of latent witchery thrown over him, as he lounged there in the warm luxuriousness of the tropical noontide, with which this beautiful creature at his side, in her careless attitude, all symmetry and grace, seemed so wholly in keeping.

"What a strange name that is of yours," he said, in the abrupt, unthought-out way which was so characteristic of him.

She started slightly at its very abruptness, then smiled.

"Is it?" she said; "well, your own is not a very common one."

"No, it isn't; which is a bore at times, because people will persist in spelling it wrong. It might have been worse, though. They went in for giving us all more or less cloth-of-gold sort of names, though mine smacks rather of the cloister than of the lists. One of my brothers they dubbed Aylmer. He was in a regiment, and the mess would persist in calling him Jack, for short. He resented it at first—afterwards came to prefer it. Said it was more convenient. Well, it was."

"Mine is older than that. The very oldest feminine name on record," she said, with just a spice of quiet mischief. "Lilith was Adam's first wife."

If she thought the other was going to look foolish at hearing his own words thus reproduced in such literal fashion, she never made a greater mistake in her life.

"So tradition hath it," he rejoined, with perfect unconcern. "It's a queer out-of-the-way sort of name—I'm not sure I don't rather like it. There's a creeping suggestion of witchery about it, too, which is on the whole attractive."

He was looking at her straight in the eyes, for they had both risen, the luncheon-bell having rung. She unflinchingly returned the glance, which on both sides was that of two adversaries mentally appraising each other prior to a rapier-bout.

"Then beware such unholy spells," she replied, with a light but enigmatical laugh. And turning, she left him.

"Beware of such unholy spells," she replied.

Now Holmes, who, bursting with astonishment and trepidation as he beheld how his friend was engaged, came bustling up, with a scared and furtive demeanour.

"By the Lord, old man, we just have put our foot in it," he sputtered. "All the time we were sitting here, Miss Ormskirk was just inside the companion. She must have heard every word we said."

"Don't care a hang if she did."

"Man alive, but we were talking about her! About her, and she heard it! Don't you understand?"

"Perfectly; still I don't care a hang. A hang? No, nor the rope, nor the drop, nor the whole jolly gallows do I care. Will that do?"

Holmes gasped. This fellow Stanninghame was a lunatic. Mad, by Jove! Still gasping as he thought of the enormity of the situation, he left without another word, diving below to try and drown his confusion in a whisky and soda, iced.

But the other, still lingering on the now deserted deck, was conscious of a very unwonted sensation. The spell which he had derided so bitterly when beholding others drawn within its toils had begun to weave itself around him. This vague stirring of his mental pulses, what did it mean? Heavens! it was horrible. It brought back old memories, whose tin-pot unreality was never recalled save as subject matter for bitter gibe and mockery. He could not have believed it possible.

"It's the nerves," he told himself. "These years of squalid worry have done it. My nerves are shaken to bits. Well, I must pull them together again. But oh, the bosh of it! the utter bosh of it!"

THE sway of Lilith Ormskirk over the saloon and quarter-deck of the Persian was as complete as any woman's sway ever is. From the grizzled captain—nominally under whose charge she was making the voyage—down to the newly emancipated schoolboy going out to seek employment, the male element was, with scarcely an exception, her collective slave. Among the women, of course, her rule was less complete; those who were furthest from all possibility of rivalling her in attractiveness of person or charm of manner being, of course, the most virulent in their jealousy and the expression thereof. Lilith, however, cared nothing for this, or, if she did, gave no sign. She was never bitter, even towards those whom she knew to be among her worst detractors, never spiteful. She was not faultless, not by any means, but her failings did not lie in the direction of littleness. But she always seemed bright and happy, and full of life—too much so, thought more than one of her perfervid adorers, who would fain have monopolized her.

She was in the mid-twenties—that age when the egotism and rather narrow enthusiasms and prejudices of the girl shade off into the graciousness and savoir-vivre of womanhood. She could look back on more than one foolishness, from whose results she had providentially escaped, with an uneasy shudder, followed by a heartfelt thankfulness, and a sense of having not only learnt but profited by experience, which sense enlarged her mind and her sympathies, and imparted to her demeanour a self-possession and serenity beyond her years.

We said the male element, with scarce an exception, was her collective slave. Such an exception was Laurence Stanninghame.

Without being a misogynist, he had no great opinion of women. He owned they might be delightful—frequently were—up to a certain point, and this was the point at which you began to take them seriously. But to treat any one of them as though the sun had ceased to shine because her presence was withdrawn, struck him as sheer insanity. It might be all right for youngsters like Holmes or Swaynston, the licensed fool of the smoking room, or Dyson, to whose senile enthusiasm for the mazy rout we have heard allusion made—the latter on the principle of "no fool like an old fool"; but not for him—not for a man in the matured vigour of his physical and mental powers. Wherefore, when forced himself to acknowledge the spell which Lilith had begun to weave around him, he unhesitatingly set it down to impaired nerves.

As a direct result, he avoided the cause. It was a cowardly course of action, he told himself. He was afraid of her. If she could throw the magic of her sorcery over him during a brief ten minutes of conversation, what the very deuce would happen if he allowed himself to be drawn into anything approaching the easy-going shipboard intimacy—deck-walking by moonlight, chairs drawn up in a snug corner during the heat of the day, and so forth! Who knew what latent capacities for being made an ass of might not develop themselves within him. He felt really alarmed.

Let it not be supposed that any scruple on the ground of conventionality, obligation, what not, entered into his misgivings. For Laurence Stanninghame had been clean disillusioned all along the line. He hadn't the shred of an illusion left. He had started life with a fair stock-in-trade of good intentions and straight ideas, and, indeed, had acted up to them honestly, and in good faith. But now?—"I've had a h——l of a time!" he would exclaim to himself, during one of those meditative gazes out seaward, for which we heard his younger friend taking him to task. "Yes—just that." And now, only touching middle life, he believed in nothing and nobody. He had become a cold, keen, strong-headed, selfish cynic. If ever his mind reverted to the fresher and more generous impulses or actions of his younger days, it was with a contemptuous self-pity. His view of the morality of life now was just the amount of success, of advantage, of gratification to be got out of it. He thoroughly indorsed the principle of the old roué's advice to his grandson: "Be good, and you may be happy—but you'll have d——d little fun," taking care to italicise the word "may." For he had found that the first clause of the saw had brought him neither happiness nor fun.

With his fellow-passengers on board the Persian he was neither popular nor the reverse. Among the men, some liked him, others didn't. He was genial enough, and good company in the smoking room, but wouldn't do anything in the way of promoting the general amusement—and that voyage was a particularly lively one in the matter of getting things up. The fair section of the saloon was puzzled, and could not make up its mind whether to dislike him or not. For the first, he consistently, though not ostentatiously, avoided it, instead of laying himself out to make himself agreeable—though indications were not wanting that he could so make himself if he chose. For the second, the fact that he remained an unknown quantity was in his favour, if only that the unfamiliarity of reserve—mystery—never fails to appeal strongly to the minds of women—and savages.

It was not so difficult for him to avoid Lilith Ormskirk, if only that until that morning he had hardly exchanged a hundred words with her at a time. Wherefore the upshot of his resolve was noticeable neither by its object nor by the passengers at large. Holmes, indeed, who, having recovered from his consternation, had been secretly watching his friend, was anticipating the fun of seeing the latter fall headlong into the pit whose brink he had so boldly skirted, so openly derided. But he was disappointed. Laurence, if he referred to Lilith again, did so in the same casual, indifferent way as before, nor did he ever terminate any of his dreamy and seaward-gazing meditations in order to open converse with her, even with such inducement as solitary propinquity on more than one occasion.

"By Jove! the fellow is a cross between an icicle and a stone," quoth Holmes to himself, in mingled wonder and disgust.

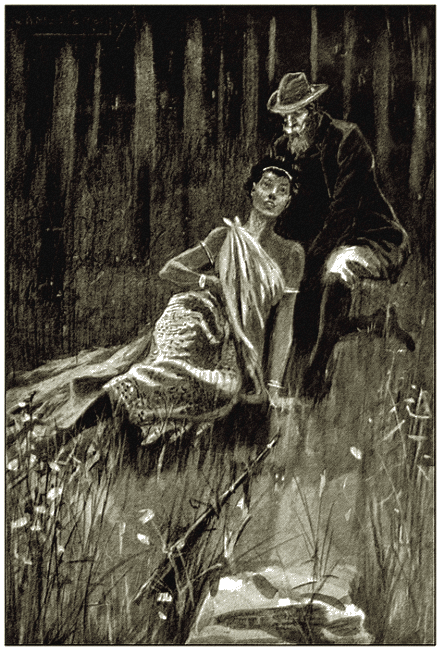

It was night—warm, sensuous, tropical night. There was dancing in the saloon, and the glare from the skylight and the banging of the piano and chatter of voices gave forth strange contrast to the awesome stillness of the great liquid plain, the dewy richness of the air, the stars hanging in golden clusters from a black vault, the fiery eye of some larger planet rolling and flashing among them as the revolving beacon of a lighthouse. Here the muffled throb of the propeller, and the rushing hiss of water as the prow of the great steamer sheared through the placid surface, furrowing up on either side a long line of phosphorescent wave. Such a contrast he who stood alone in the darkness, leaning over the taffrail, could appreciate nicely.

There were quick, light footsteps. Somebody else was walking the deck. Well, whoever it was, he himself was screened by the stem of one of the ship's boats swung in and resting on chocks. They would not see him, which was all right, for he was in a queer mood and not inclined to talk. After a turn or two, the footsteps paused, then something brushed his elbow in the darkness, as suddenly starting away, while a half-frightened voice exclaimed:

"Oh, I beg your pardon. I couldn't see anything in the dark, just coming up out of the light of the saloon, too. Why, it's Mr. Stanninghame!"

To one who had been out of doors even a few minutes it was not very dark, for the stars were shining with vivid brilliancy. It needed not the sense of sight, that of hearing was enough. Nay, more, a subtile sixth sense, whatever it might be, had warned Laurence Stanninghame of the identity of the intruder.

"No case of mistaken identity here," he said. "But how is it you are all by yourself?"

"Oh, I got tired of all the whirl and chatter. I craved for some fresh air, and so I stole away," said Lilith. "Why, how heavy the dew is here in these tropical seas!" she added, withdrawing her arm from the taffrail upon which she had begun to lean.

The man, watching her furtively, said nothing for a moment. That same chord within him thrilled to her voice, her propinquity. Doubtless his nerves, high strung with recent worry, were playing the fool with him. He was conscious of a kind of envenomed resentment, almost aversion; yet his chief misgiving at that moment, which he recognized with added wrath, was lest she should leave him as quickly as she had come.

"All by yourself as usual!" she went on, flashing at him a bright smile. "Thinking, I suppose?"

"I don't know that I was. I believe I was trying to realize the immensity and silence of the midnight ocean, as far as that tin-pot racket down there would allow one to realize anything. Then it occurred to me how long it would take for the intense solitude to drive a man mad if he were cast away alone in it."

"Not long, I should think," answered Lilith, gazing seriously out over the smooth, oily sea. "The horror of it would soon do that for me."

"And yet why should it have such an effect at all?" he went on. "The grandeur of the situation ought to counterpoise any such weakness. Given enough to support life without undue stinting, with a certainty of rescue at the end, and, I think, a fortnight as castaway in these waveless seas would be an uncommonly interesting experience."

"What? A fortnight? A whole fortnight in ghastly solitude! Silence only broken by the splash or snort of Heaven knows what horrible sea monster! Any consideration of peril apart, I am sure that one night of it would turn me into a raving, gibbering lunatic."

"Perhaps. People are differently built. For my part, discounting the 'sea monster,' I am certain I should enjoy the experience. For one thing, there would be no post."

"But no more there is here on board," she said, struggling with the laugh which the dry irrelevancy had brought to her lips.

"No—but there's—Swaynston."

This time the laugh came rippling outright, and through it came the sound of footsteps.

"Oh, here you are, Miss Ormskirk. I've been looking for you everywhere. This is our dance."

Lilith, catching the satirical twinkle in the other's eyes in the starlight, did not know which way to turn to control an overmastering impulse to laugh uninterruptedly for about five minutes, the cruel part of it being that the interrupter was Swaynston himself.

The latter, a pursy individual, was holding out an arm somewhat in the attitude of a seal's flipper; but Lilith did not take it.

"Do be very good-natured and excuse me," she said. "I don't want to dance any more to-night; the noise and heat have made my head ache."

"Really, really? I'll find you a chair then, in some quiet corner," fussed Swaynston. But Lilith seemed not enthusiastic over that allurement, and finally, with some difficulty, she got rid of him; he grinning "from the teeth outwards," but consumed with fury nevertheless.

So that was why she had stolen away from them all, to slip up and talk in a quiet corner with that fellow Stanninghame, who was probably some absconding swindler, with a couple of detectives and a warrant waiting for him in Table Bay? Thus Swaynston.

Nor would it have tended to allay his irritation could he have heard the object of it after his departure.

"So you think he is worse than the post?" she said, with a laugh in her eyes. "Yet he is one of the most devoted of my—poodles."

The demure malice of her tone no more disconcerted the other than that former endeavour to show him she had overheard his remarks by quoting his own words.

"Oh, yes," was the unconcerned reply. "He sits up on his hind legs a little better than any of them."

For a few moments she said nothing, seeming to have become infected with her companion's dreamy meditativeness. Then:

"And you are not tired of the voyage yet? You were saying the other day that its monotony was enjoyable."

"I say so still. Look!" he broke off, pointing to the sea.

A commotion was going on beneath its surface. Their grisly shapes vivid in the disturbed phosphorescence, drawing a wake of flame behind them, rushed two great sharks. Hither and thither they darted, every detail of their ugly forms discernible on the framing of the phosphorescent blaze, even the set glare of the cruel eye; and, no less nimble in swift doubling flashes, several smaller fish were trying to evade the laws of nature—the absorption of the weakest, to wit. There was something indescribably horrible in the fiery rush of the sea-demons beneath the oily blackness of the tropical waters.

"How awful! how truly awful!" murmured Lilith, with a strong shudder of repulsion, yet gazing as one fascinated at the weird sight.

"Yet it is the perfection of an object lesson, one that comes in just in time to point the moral to my answer," he said. "If those fish, now in process of being eaten, were caught and kept in an aquarium tank, it might be more monotonous for them than furnishing fun and food to the first comer in the way of bigger fish. Possibly they might yearn for the excitement of being harried, though I doubt it. That sort of philosophy is reserved for us humans. If we knock our heads against a brick wall we howl; if we haven't got a brick wall to knock them against we howl louder."

"And the moral is?"

"Dona nobis pacem."

"I see," she said at last, for it took her a little while to thoroughly grasp the application, partly distracted as her thinking powers were in trying to find a deeper meaning than the one intended. "Yet peace is a thing that no one can enjoy in this world. How should they when the law of life is struggle—struggle and strife?"

"Precisely. That, however, is due to the faultiness of human nature. The philosophy of the matter is the same. Its soundness remains untouched."

"Yet you are not consistent. You were implying just now that, failing a brick wall to knock our heads against, we started in search of one. Now does not that apply to those who go out into the world—to the other end of the world—instead of remaining peacefully at home?" she added, a sly sort of "I-have-you-there" inflection in her tone.

"Pardon me. My consistency is all right. Begging a question will not shatter it."

"Begging a question?"

"Of course. For present purposes the said begging is comprised in the word 'peacefully.' See?"

"Ah!"

Again she was silent. The other, watching the flash of the starlight on the meditative upturned eyes, the clearly marked brows, the firm setting of the lips, was more conscious than ever of the latent witchery in the sweet, serene face. He would not flee from its spells now, he decided. He would meet them boldly, and throw them off, coil for coil, however subtilely, however dexterously they were wound about him. Meanwhile, two things had not escaped him: She had yielded the point gracefully, and convinced, instead of launching out into a voluble farrago of irrelevant rubbish, as ninety-nine women out of a hundred would have done in order to have "the last word." That argued sense, judgment, tact. Further, she had avoided that vulgar commonplace, instinctive to the crude and unthinking mind, of whatever sex, of importing a personal application into an abstract discussion. This, too, argued tact and mental refinement, both qualities of rarer distribution among her sex than is commonly supposed—qualities, however, which Laurence Stanninghame was peculiarly able to appreciate.

Then she talked about other things, and he let her talk, just throwing in a word here and there to stimulate the expansion of her ideas. And they were good ideas, too, he decided, listening keenly, and balancing her every point, whether he agreed with it or not. He was interested, more vividly interested than he would fain admit! This girl with the enthralling face and noble beauty of form, had a mind as well. All the slavish adoration she received had not robbed her of that. It was an experience to him, as they lounged there on the taffrail together in the gold-spangled velvet hush of the tropical night. How delightfully companionable she could be, he thought; so responsive, so discriminating and unargumentative. Argumentativeness in women was a detestable vice, in his opinion, for it meant everything but what the word itself etymologically did. Craftily he drew her out, cunningly he touched up every fallacy or crudeness in her ideas, in such wise that she unconsciously adopted his amendments, under the impression that they were all her own.

"But—I have been boring you all this time," she broke off at last. "Confess now, you who are nothing if not candid. I have been boring your life out?"

"Then, on your own showing, I am nothing, for I am not candid," he answered. "On the contrary, it is an unadvisable virtue, and one calculated to corner you without loophole. And you certainly have not been boring me."

He thought, sardonically, what any one of those whom he had caustically defined as her "poodles" would give for an hour or so of similar boredom, if it involved Lilith all to himself. Some of this must have been reflected in his eyes, for Lilith broke in quickly:

"No, you are not candid. I accept the amendment. I can see the sarcasm in your face."

"But not on that account," he rejoined tranquilly, and at the same time dropping his hand on to hers as it rested on the taffrail. The act—an instinctive one—was a dumb protest against the movement she had made to withdraw. And as such Lilith read it; more potent in its impulsiveness than any words could have been. "Listen!" he went on. "I suppose there is a sort of imp of scepticism sitting ever upon one shoulder, and that is what you saw. Something in my thoughts suggested a droll contrast, that was all. So far from boring me, you have afforded me an intensely agreeable surprise."

"Now you are sneering again. I will not talk any more."

He recognized in her tone a quick sensitiveness—not temper. Accordingly his own took on an unconscious softness, a phenomenally unwonted softness.

"Don't be foolish, child. You know I was doing nothing of the sort. Go on with what you were saying at once."

"What was I saying? Oh, I remember. That idea that board-ship life shows people in their real character. Do you believe in it?"

"Only in the case of those who have no real character to show. Wherein is a paradox. Those who have got any—well, don't show it, either on board ship or on shore."

"I believe you are right. Now, my own character, do you think it shows out more readable on board than it would on shore."

"Do you think you have me so transparently as that? What was I saying just now on that head?"

"I see. Really, though, I had no ulterior motive. I asked the question in perfect good faith. Tell me—if anyone can, you can. Tell me. Shall I make a success—a good thing of life? I often wonder."

She threw up her head with a quick movement, and the wide, serious eyes, fixed full upon his, seemed to flash in the starlight. He met the glance with one as earnest and unswerving as her own.

"You rate my powers of vaticination too high," he said slowly, "and—you are groping after an ideal."

"Perhaps. Tell me, though, what you think, character-reader as you are. Shall I make a success of life?"

"I should think the chances were pretty evenly balanced either way, inclining, if anything, to the reverse."

"Thanks. I shall remember that."

"But you are not obliged to believe it."

"No. I shall remember it. And now I must go below; it is nearly time for putting out the saloon lights. Good-night. I have enjoyed our talk so much."

She had extended her hand, and as he took it, the sympathetic—was it magnetic?—pressure was mutual, almost lingering.

"Good-night," he said. "The enjoyment has not been all on one side."

Left alone, he returned to his solitary musings—tried to, rather, for there was no "return" about the matter, because now they took an entirely new line. His late companion would intrude upon them—nay, monopolized them. She had appealed powerfully to his senses, to his mind, how long would it be before she did so to his heart? He had avoided her—he alone—up till then, and yet now, after this first conversation, he was convinced that of all gathered there he alone knew the real Lilith Ormskirk as distinct from the superficial one known to the residue. And to his mind recurred her former warning, laughingly uttered: "Beware such unholy spells!" With a strange intoxicating recollection did that warning recur, together with the consciousness that more than ever was it needed now. But as against this was the protecting strength of a triple chain armour. Life was only rendered interesting by such interesting character studies as this. Oh, yes; that was the solution—that, and nothing more.

This was by no means the last talk they had—they two alone together. But it seemed to Laurence Stanninghame that a warning note had been sounded, and one of no uncertain nature. His tone became more acrid, his sarcasm more biting, more envenomed. One day Lilith said:

"Why do you dislike me so?"

He started at the question, thrown momentarily off his guard.

"I don't dislike you," he answered shortly.

"Then why have you such a very poor opinion of me? You never lose an opportunity of letting me see that you have. What have I done? What have I said that you should think so poorly of me?"

There was no spice of temper, of resentment, in the tone. It was soft, and rather pleading. The serious eyes were sweet and wistful. As his own met their steady gaze, it seemed that a current of magnetic thought flashed from mind to mind.

"I hold no such opinion," he said, after a few moments of silence. "Perhaps I dread those 'unholy spells,' thou sorceress. Ah! there goes the second dinner-bell. Run away now, and make yourself more beautiful than ever—if possible."

A bright laugh flashed in the hazel eyes, and the white teeth showed in a smile.

"I'll try—since you wish it," she said over her shoulder, as she turned away.

THE throb of the propeller has almost ceased; faint, too, is the vibration of the slowed-down engines. The Persian is gliding with well-nigh imperceptible motion through the smooth waters of Table Bay.

It is a perfect morning, cloudless in its dazzling splendour. In front, the huge Table Mountain rears its massive wall, dwarfing the mud-town lying at its base and the bristling masts of shipping, its great line mirrored in the sheeny surface. Away in the distance, the purple cones of the Hottentots Holland mountains loom thirstily through a glimmer of summer haze. A fair scene indeed after three weeks of endless sea and sky.

"And what are your first impressions of my native land?"

Laurence turned.

"I was thinking less of the said land than of myself," he answered. "I was thinking what potentialities would lie between my first impressions of it and my last."

Just a suspicion of gravity came over Lilith Ormskirk's face at the remark.

"And are you glad the voyage is at an end, now that it is?" she went on.

"You know I am not. It was such a rest."

"Which I was everlastingly disturbing."

"By wreathing those unholy spells. Lilith, thou sorceress, how long will it be before those talks of ours are forgotten? A week, perhaps?"

"They will never be forgotten," she answered, her eyes dreamy and serious. "But now, I must go below and finish doing up my things. We shall be in dock directly."

A great crowd is collected on the quay as the steamer warps up, above which rise sunshades coloured and coquettish, pith helmets and sweeping puggarees, and more orthodox white "stove-pipes." Then in the background, yellow-skinned Malays in gaudy Oriental attire, parchment-faced Hottentots, Mozambique blacks, and lighter-hued Kaffirs from the Eastern frontier. The docks are piled with luggage, for the privilege of carrying which and its multifold owners Malay cab-drivers are uttering shrill and competing yells. On board, people are bidding each other good-bye or greeting those who have come to meet them; and flitting among such groups, a mingled expression of alertness and anxiety on his countenance, is here and there a steward, bent upon sounding up a possibly elusive "tip," or refreshing an inconveniently short memory.

Near the gangway Lilith Ormskirk was holding quite a farewell court. Her "poodles," as Laurence had satirically defined them, were crowding around—Swaynston at their head—for a farewell pat. The last, in the shape of Holmes and another, had taken their sorrowful departure, and now a quick, furtive look seemed to cross the smiling serenity of her face, a shade of wistfulness, of disappointment. Thus one in the hurrying throng at the other side of the deck read it.

"What a tail-wagging!" almost immediately spake a voice at her side.

She turned. Decidedly the expression was one of brightening.

"I thought you had gone—had forgotten to say good-bye," she said.

"I was waiting until the poodles had finally cleared. Now, however, I have come to utter that not always hateful word."

"Not in this instance?"

"Yes, distinctly. I have just heard there is to be a special train made up—we are in too late for the regular mail-train, you know. So I shall leave for Kimberley in about two or three hours' time."

Lilith looked disappointed.

"I thought you would have stayed here at least a few days," she said. And then the friends who had met her on board returned, and Laurence found himself introduced to three pretty girls—fair-haired, blue-eyed, well-dressed—eke to a man—tall, brown-faced, loosely hung, apparently about thirty years of age—none of whose names he could quite succeed in catching, save that the latter was apostrophized as "George." Then, after a commonplace or two, good-byes were uttered and they separated—Lilith and her party to catch the train for Mowbray, her late fellow-passenger to arrange for his own much longer journey.

Having the compartment to themselves, one of the blue-eyed girls opened fire thus:

"Lilith, who is he?"

"Who?"

"He."

"Bless the child," laughed Lilith, "there were about half a hundred he's."

"No, there was only one. Who is he? What is he?"

"I don't know," replied Lilith, affecting ignorance no longer.

"You don't know? After three weeks on board ship together? Three whole weeks of ship life, and you have the face to tell me you don't know anything about him. After the way in which you said good-bye to each other, too? Oh, I saw."

"Well, I don't know."

"Or care?"

"Chaff away, if it's any fun to you," answered Lilith quite serenely, as the trio rippled into peals of laughter.

"I liked the man, liked to talk to him on board—you are welcome to the admission—but all I know is that he is going to Johannesburg. We may never see each other again."

"These English Johnnies who come out here, and whom one knows nothing about, are now and again slippery fish," gruffly spoke the brown-faced one. "Watch it, Lilith."

"I thought this one looked as if he might be interesting," said another of the blue-eyed girls. "Pity he wasn't staying a day or two. We might have got him out to the house and seen what he was made of."

"Watch it," repeated George sententiously. "Watch it, Lilith."

Meanwhile, the object of this discussion—and warning—having resignedly "passed" the Customs at the dock gates, was spinning townwards in one of the innumerable hansoms. Sizing up the South African metropolis, it gave him the idea of a mud city, just dumped down wet and left to dry in the sun. Its general aspect suggested the vagaries of some sportive Titan, who, from the summit of the lofty rock wall behind it, had amused himself, out of office hours, by chucking down chunks of clay of all sorts and sizes, trying how near he could "lob" them into the position of streets and squares.

At that time the railway line ended at Kimberley—the distance thence to Johannesburg, close upon three hundred miles, had to be done by stage. It occurred to Laurence that, having a couple of hours to spare, he had better look up the coach-agent and secure a seat by wire.

The agent was not in his office. Laurence Stanninghame, however, who knew the ways of similar countries, albeit a new arrival in this, inquired for that functionary's favourite bar. The reply was prompt and accurate withal. In a few minutes, seated on stools facing each other, he and the object of his search were transacting business.

The latter did not seem entirely satisfactory. The agent could not say when the earliest chance might occur by regular coach. He might have to wait at Kimberley—well, it might be for days, or it might be for ever. On the other hand, he might not even have to wait at all. He could not tell. Even the people at the other end could not say for certain. Laurence began to lose patience.

"See here," he said somewhat testily. "I haven't been long in your country, but that's about the only reply I've been able to meet with to any question yet. Tell me, as a matter of curiosity, is there any one thing you are ever certain of out here? Just one."

The agent looked at him with faint amazement.

"There is one," he said; "just one."

"Well—and that?"

"Death. That's always a dead cert. Let's liquor. Put a name to it, skipper."

The special train consisted of a mail van and a first-class carriage. There being only three or four other travellers each had a compartment to himself, an arrangement which met with Laurence Stanninghame's unfeigned approval. He did not want to talk—especially in a clattering, dusty railway carriage. At intervals the passengers foregathered for meals at some wayside buffet or accommodation house,—meals whose quality was in inverse ratio to the exuberance of the prices charged therefor,—then each would return to his own box and smoke and read and sleep away the little matter of seven hundred miles.

On they sped for hours and hours—on through sleepy Dutch villages, whose gardens and cultivation made an oasis on the surrounding flats—on, winding in a slow ascent through the gloomy grandeur of the Hex River Poort, with its iron-bound heights rearing in mighty masses from the level valley bottom. Then it grew dark, and, the dim oil lamp being inadequate for reading purposes, Laurence went to sleep.

"Afar in the desert I love to ride,"

sang Pringle, the South African bard.

"Pringle was a liar, or a lunatic," quoth Laurence Stanninghame, to whom the passage was familiar, on opening his eyes next morning and looking around. For the train was speeding—when not slowing—through the identical desert of which Pringle sang; that heart-breaking, dead-level, waterless, treeless belt known as the Karroo. Not a human habitation in sight, for hours at a stretch—the same low table-topped mountains rising hours ahead, and which never seemed to get any closer, looking, moreover, in the distant, mirage-effects, like vast slabs poised in mid-air and resting on nothing. At long intervals a group of foul and tumble-down Hottentot huts, with their squalid inhabitants—lean curs and ape-like men; their raison d'être, in the shape of a flock of prematurely aged and disappointed-looking goats, trying all they are worth to extract sustenance from the red shaly earth and its sparse growth of coarse bush-like herbage. Looking out on this horrible desert, the eye and the mind alike grow weary, and the latter starts speculating in a shuddering sort of a way as to how the deuce anything human can find it in its heart to exist in such a place. Yet though an awful desert in time of drought it is not always so.

But gazing forth upon the surrounding waste, Laurence was able to read into it a certain charm—the charm of freedom, of boundlessness, so vividly standing out in contrast to his own cramped, narrow, shut-in life. All the changed conditions—the wildness, the solitude, the flaming and unclouded sun—were as a new awakening to life. The current of a certain joy of living, long since sluggish, congealed, now coursed swiftly and without hinderance through his being.

Now through all those hours of tedious travelling—in the flaming glow of day, or in the still, cool watches of the night, he had with him a recollection—Lilith Ormskirk's face haunted him. Those eyes seemed to follow him—sweet, serious; or again mirthful, flashing from out their dark fringe of lashes, but ever entrancing, ever inviting. Her whole personality, in fact, seemed to pervade his mind, warring for sole possession, to the exclusion of all other thought, all other consideration. Into the conflict his own mind entered with a zest. It was a psychological struggle which appealed to him, and that thoroughly. She should not, by her witchery, take entire possession. Yet the recollection of her was so potent that at length he ceased to strive against it. He gave way,—abandoned himself contentedly, voluptuously to its sway,—even aiding it in the pictures it conjured up. Now he saw her, as he had first passed her, day after day on board ship, with indifference, with faintly ironical curiosity; again, as when they had first begun to talk together; and yet again, when he had found himself resorting to all manner of cowardly mental expedients to persuade himself that he did not revel in her dangerously winning attractiveness, and sweet sympathetic converse. In the monotonous three-four time beat of the wheels he could conjure up her voice—even the colonial trick of clipping the final "r" in words ending with that letter—as to which he had often rallied her, while secretly liking it—for this, like a touch of the brogue, can be winsome enough when uttered by pretty lips. Now all these reflections could not but be profitless, possibly dangerous, yet they had this advantage—they helped to kill time, and that during a thirty-odd-hour journey across the Karroo. Well, it is an advantage!

On through the long, hot day, and still that memory was with him. The solitude, the stillness, the mile after mile over the desolate and barren waste, the novelty of the scene, the monotonous rattle of the wheels—all went to perpetuate it. Then the sun drew down to the horizon, and the departing glow, striking upon the red soil, painted the latter the colour of blood, making up an extraordinarily vivid study in red and blue. Overhead a cloudless sky, the horizon all aflame, and the whole earth, far as the eye could reach, steeped in the richest purple red. Laurence fell fast asleep.

He dreamed they were steaming into Charing Cross Station. Lilith was waiting to meet him. He swore, in his dream, because they had halted on the railway bridge too long to take the tickets. Then he awoke. They were steaming slowly into a terminus, amid the familiar flashing of lamps and the rumbling of porters' trucks. But it was not Charing Cross, it was Kimberley.

Not long did it take him to collect his scanty baggage and fling it into a "cab," otherwise an open, two-seated Cape cart. Hardly had he taken his seat than the driver uttered a war-whoop, and, with a jerk that nearly sent its passenger somersaulting into the road, the concern started off as hard as its eight legs and two wheels could carry it.

The night was dark, the streets guiltless of lighting. As the trap zigzagged furiously from one side of the way to the other, now poised on one wheel, now leaping bodily into the air as it charged through a deep hole or rut, it was a comfort to the said passenger to reflect that the road being feet deep in sand one was bound to fall soft anyhow. Yet, candidly, he rather enjoyed it. After thirty-three hours in a South African "Flying Watkin" even this spurious excitement was welcome.

They shaved corners, always on one wheel, sometimes even scraping the corners of houses, and causing those pedestrians in their line of flight to skip like young unicorns. Then, recovering, the startled wayfarers would hurl their choicest blessings after the cab. To these, the madcap driver would reply with a shrill and fiendish yell, belabouring his frantic cattle with a view to attempting fresh feats. They succeeded. It only wanted a bullock-waggon coming down the street to afford them the opportunity. The bullock-waggon came. Then a dead, dull scrunch—an awful shock—and the cab was at a standstill. The waggon people opened their safety-valves and let off a fearful blast of profanity; the cab-driver replied in suitable and feeling terms, then backed clear of the wreck and whipped on.

Vastly amused by this lively experience, Laurence still ventured to expostulate, mildly, and as a matter of form. But he got no more change out of his present Jehu than Horace Greeley did of Hank Monk. The reply, accompanied by a jovial guffaw, was:

"All right, mister. You sit tight, and I'll fetch you through. Which hotel did you say?"

Laurence refreshed his memory—and swaying, jerking, pounding, into ruts and holes, the chariot drew up like a hurricane blast before quite an imposing-looking building at the corner of the Market Square. Having paid off the lunatic of the whip and stood him a drink, Laurence engaged a room, and wondered what the deuce he should do with himself if delayed here any time. For the glimpse he had obtained of the place seemed not inviting. The same crowded bars, the same roaring racket, the same dust—yea, even the same thirst. He had seen it all before in other parts of the world.

He was destined to wonder still more, and wearily, what he should do with himself; for nearly a week went by before he could secure a seat in the coach. A great depression came upon him, begotten of the heat and the drowsiness and the dust, as day after day seemed to bring with it no emancipation from the wind-swept, tin-built town, dumped down on its surrounding flat and sad-looking desert waste. Yet nothing akin to homesickness was there in his depression. He wanted to get onward, not to return. He was bored and in the blues. Yet, as he looked back, the feeling which predominated was that of freedom—of having a certain measure of life and its prospects before him. Stay, though. His thoughts would, at times, travel backward, and that in spite of himself, and they would land him with a lingering, though unacknowledged, regretfulness, on the deck of the Persian. Well, that was only an episode. It had passed away out of his life, and it was as well that it had.

But—had it?

At last, to our wayfarer's unspeakable joy, deliverance came. It had been Laurence's lot to travel in far worse conveyances than the regular coaches which at that time performed the journey between Kimberley and Johannesburg, a distance of close upon three hundred miles; consequently, although not among the fortunate ones who had secured a corner seat, he managed to make himself as comfortable as any traveller in comparatively outlandish regions has a right to expect. His fellow-passengers consisted, for the most part, of mechanics of the better sort and a loquacious Jew—not at all a bad sort of fellow—in conversation with whom he would now and then beguile the weariness of the route. And it was weary. The flat sameness of the treeless plains, as mile after mile brought no change; the same stony kopjes; the same deserted and tumble-down mining structures; the same God-forsaken-looking Dutch homesteads, whose owners had apparently taken on the triste hopelessness of their surroundings; the same miserable wayside inns, where leathery goat-flesh and bones and rice, painted yellow, were dispensed under the title of breakfast and dinner, what time the coach halted to change horses, and even then only served up when the driver was frantically vociferating, "All aboard!" Thus they journeyed day and night, allowing, perhaps, three hours, or four at the outside, for sleep—on a bed. But the latter proved an institution of dubious beneficence, because of its far from dubious animation; the said "animation" scorning blithely and imperviously accumulations of insect powder, reaching back into the dim past, left there and added to by a countless procession of tortured travellers. Howbeit, of these and like discomforts are such journeyings productive, wherefore they are scarcely to be reckoned as worthy of note.

"HALLO, Stanninghame! And so, here you are?"

"Here I am, Rainsford, as you say; and from what I have heard in process of getting here, I'm afraid I have got here a day too late."

The other laughed, as they shook hands. He was a man of Laurence's own age, straight and active, and his bronzed face wore that alert, eager look which was noticeable upon the faces of most of the fortune-seekers, for of such was the bulk of the inhabitants of Johannesburg at that time.

"You never can tell," he rejoined. "Things are a bit slack now, because of this infernal drought; but a good sousing rain, or a few smart thunder showers, would fill all the dams and set the batteries working again harder than ever. It's the rainy time of year, too."

It was the morning after Laurence's arrival in Johannesburg, and, while sallying forth to find Rainsford, the two had met on Commissioner Street. The brand-new gold-town looked anything but what it was. It did not look new. In spite of the general unfinishedness of the streets and sidewalks, the latter largely conspicuous by their absence; in spite of the predominance of scaffolding poles and half-reared structures of red brick; in spite of the countless tenements of corrugated iron, and the tall chimneys of mining works which came in here where steeples would have arisen in an ordinary town; in spite of all this there was a battered and weather-beaten aspect about the place which made it look centuries old. Great pillars of dust towered skywards, then dispersing, whirled in mighty wreaths over the shining iron roofs, to fall hissing back into the red-powdery streets whence they arose, choking with pungent particles the throats, eyes, and ears of the eager, busy, speculative, acquisitive crowd, who had flocked hither like wasps to a jar of beer and honey. And to many, indeed, it was destined to prove just such a trap.

"Well, what do you advise, Rainsford?" said Laurence, after some more talk about the Rand and its prospects.