RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Shafts from an Eastern Quiver, George Newnes, 1893, with:

"In Quest of the Lost Galleon"

THESE stories ... introduce the lover of sensations to a new writer, who is not at all unworthy to be placed upon the same shelf with Mr. Conan Doyle. He certainly contrives to give the three heroes of this book—the two Englishmen, Frank Denviers and Harold Derwent, and their marvellous Arab servant and good genius Hassan—as many hairbreadth escapes and other adventures by sea and land as can well be packed into a volume of less than three hundred pages.

Mr. Mansford appears to be most at home in Persia, Afghanistan, and India. But he does not confine his literary attentions to the more strictly Eastern countries; on the contrary, one of his most thrilling stories tells of the experiences of the fortunate three among Papuan wreckers, and another relates the escape of an exile from Siberia.

Undoubtedly Mr. Mansford has the gift of the story-teller, and besides, he uniformly writes like a scholar. The illustrations of the book, though small and unpretentious, are admirably executed, and enhance the piquancy—though that was hardly needed—of the letterpress.

The Spectator, 1 December 1894

"HASSAN," I said to our guide as he rested before us in the shade of the tent, "what was it those coolies lying under the trees yonder told you about Formosa?"

"The sahib shall hear," replied the Arab. "They wish to persuade the Englishmen to hire their junk to visit the island, for they learnt from me that we have met with many strange experiences during our wanderings. They declare that what may be seen in one part of it is almost beyond belief."

"Never mind what they say," I expostulated, "go on and tell us about the island. There ought to be some story concerning it to interest us, considering that the Spaniards, the Dutch, and the Chinese have all possessed it in turn. It is quite notorious for the shipwrecks on its coast, not to mention the pirates who have held it at different times, and the savage tribes said to inhabit its wildest parts."

"Ye shall hear the story, strange indeed as it is," responded the Arab; "and, besides, it partly concerns a Feringhee sailor."

"Well, go on with your yarn, Hassan," said Denviers. "What a nigger you are for trying to excite our interest before you really tell us anything."

"The sahib does not give his slave a chance to continue, but makes always a most indifferent listener," replied the Arab gravely; "and yet the great Mahomet has said that he who is impatient—"

"The story!" I interposed. "Go on, Hassan, you can tell us about Mahomet some other day." Thus abjured, the Arab, after being silent for a few minutes, related to us the strange events which followed the quest of the lost galleon.

Soon after our adventure with the Hunted Tribe of Three Hundred Peaks we left Siam, and sailing through the China Sea made for Hong Kong. Thence we set out to traverse a part of the coast of China, and at this time our tent was pitched not far from Swatow. There Hassan held a conversation with some coolies, when, from the various excited exclamations and gestures both of them and the Arab, my interest was roused sufficiently to question our guide, as narrated. As it afterwards transpired, the coolies had moved away a little only to await our decision, and were resting patiently meanwhile under the shade of a huge umbrella in addition to that afforded by the pine clump.

"Many years ago," began Hassan, "when the far-off people of Spain ruled a great continent, a galleon laden heavily with treasure wrung from the natives set out to return with its great store under the command of Don Luego, a grandee, whose name was a terror to all those who came under the Spaniard's sway. The riches which the vessel carried were almost incredible, yet Don Luego had no word of praise or thanks for the sailors who toiled to convey it home across the stormy seas.

"More than one brave sailor was hung at the yard-arm for venturing to utter incautious expressions against the Spaniard's despotic rule, but at last some of the crew grew strangely silent, and took to watching Luego and conspiring together under the hatches. Among these men was one who had been put in chains several times, and whom the constant fear of death nerved on to lead his disaffected comrades against the commander.

"One morning all hands were piped on deck to witness the execution of a seaman, and Josť, the leader of the discontented part of the crew, was told off to assist. With a stern-set countenance he stepped forward, pulled the rope from his comrade's neck, and struck the fell Spaniard full in the face with it.

"'Mutiny!' gasped the astonished Don Luego; then, turning to the other seamen, he cried, 'Seize him and swing the two together from the yard-arm!'

"A number of the sailors ran forward, eager to gain favour with their commander by obeying his orders, while the rest hurriedly gathered round the doomed men, and, drawing their keen knives, prepared to defend them. Don Luego unsheathed his sword and rushed forward with a fierce cry, while the mutineers fought hand-to-hand with the other seamen. It was a desperate fray, for the men who had revolted knew their fate if once they became overpowered. On the mutineers pressed over the slippery decks, until at last their disheartened opponents ceased fighting and surrendered.

"Deserted by his men, Don Luego stood alone with his blood-red sword still gripped in his hand, for he expected no mercy from the sailors whom he had driven into rebellion. The chief mutineers gathered in a group and eagerly discussed the fate to be awarded to their defeated commander. Most of them were in favour of putting him to death in the same manner in which he had doomed his seamen; but Josť, who now headed them, proposed another plan, which eventually was agreed upon. A quantity of provisions and water were got ready, and then Don Luego was seized and disarmed in spite of his struggles. The seamen lowered him in a boat over the side of the galleon, and then, cutting the ropes, cast the fierce commander adrift at the mercy of wind and wave. They watched him as the boat was seen to rise at times on the crest of a huge wave, and saw that he shook at them threateningly his disarmed hand. At last they lost sight of him, and gathered together once more to consider their own plans and what to do with the treasure of the galleon.

"Josť, who seemed to be above the lust for gold which sprang up in the hearts of the other sailors, assumed the command, and bade the men prepare to return to Spain. He thought it best to throw himself and his crew on the mercy of the King, and, delivering up the treasure, to tell of the cruelties of Don Luego. With some reluctance the seamen agreed, and so they took their course homeward. Three days afterwards a sailor on the look-out descried several Spanish caracks to leeward, to which they signalled, and having joined company sailed on together. All the vessels carried bombards and cannons, yet within a week the whole of them, save one, had struck their colours, and nailed to the mast of each was the flag of the capturing enemy, who belonged to the sahibs' nation. The single vessel not taken was the galleon which Josť commanded, and after it, as it fled through the waves with every stitch of canvas spread, went one of the Feringhee ships.

"It was a long stern chase, for the enemy was determined to capture the galleon, yet so well were the vessels matched in speed that they swept on without any perceptible difference being made in the distance which separated them. Through all their course nothing seemed to hinder the relentless pursuit of the treasure-ship. Many times Josť cried out to his men to turn the vessel about to grapple with the other for the mastery, but they would not obey, for the Spaniards knew too well how the Feringhees could fight. A violent storm came on in which both ships were partly disabled, but still they went on as best they could before a driving wind, until they were carried from west to east and then driven north into a sea which none of them had seen before.

"Then the Spanish galleon began to slacken and the English ship to draw nearer and nearer by degrees, until one stormy evening the towering crests of the volcanic range which runs through Formosa were visible, although the sailors knew not what the land was named.

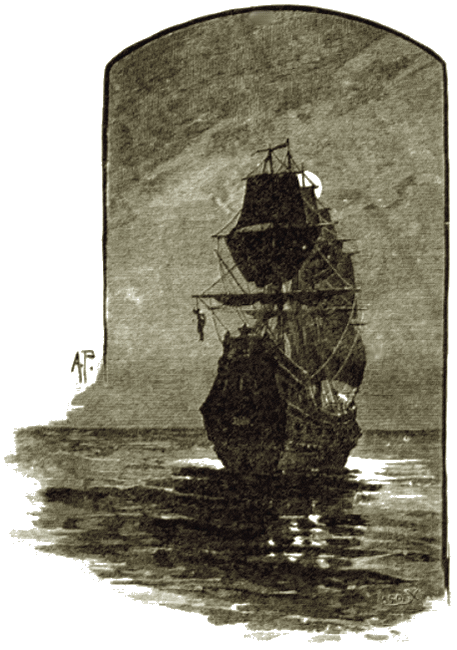

The Spanish galleon.

"Josť called upon his men to run the vessel towards it, and as the pursuers drew still closer in the gloom he determined to be revenged, even at the cost of every Spaniard's life, for the dogged way in which the enemy had hunted him down. He chose, as well as he could distinguish it, that part of the coast which seemed the most rock-bound, and then, slackening his vessel's speed, lured on the other for a time, then suddenly sped ahead as though making for a known harbour. Deceived by this, the ship which chased him followed on, and before even Jose himself was aware of the outlying reefs of coral, they struck almost together. The next minute Spaniard and Feringhee were struggling for their lives, while tremendous seas were sweeping over the two ill-fated vessels.

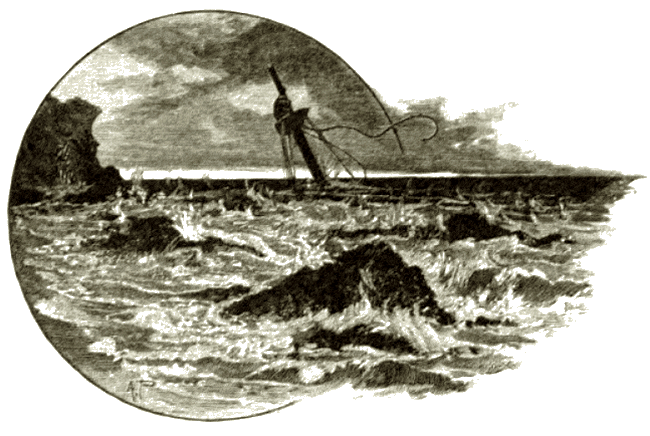

"The English ship went down, leaving only part of her mast to be seen, to which for a time a few seamen clung until one by one the waves swept them off, and out of the entire crew only a solitary sailor was left there. The Spanish galleon struck nearer to the coast, and at low water its hull could long afterwards be seen, but not a man aboard was saved. The Feringhee sailor clung to the mast all through that dreary night. Next morning, seizing a floating spar, he struck out for the shore and battled with the seething waters until, almost unconscious, he was flung high on the coral beach. Towards sunset the seaman rose, and struggling forward to the entrance of one of the caves before him, he flung himself down to sleep.

Only a solitary sailor was left.

"The coolies say that the sailor afterwards explored a part of the coast and then set about making his presence known to any vessel which might chance to pass the island. Getting possession of part of the broken mast of one of the ships, he raised it on the beach, and hoisted to the top of it the tattered flag of the English vessel, which chanced to be flung up by the waves. For weeks and months his signal passed unnoticed; and meanwhile the sailor made a raft, and at low water reached the hulk of the Spanish ship several times, from which by degrees he carried away the treasure. This he hid in the cave which he occupied, hoping that one day he would be rescued. He found arms and ammunition in the galleon in abundance, and well it was for him that he secured them and made them serviceable in case of need.

"Lying before the cave one day he saw the dusky forms of several savages appear, at which the sailor immediately seized the nearest Spanish musket and prepared to defend himself. In a moment they discovered him and cast a shower of spears towards the entrance of the cave. The Feringhee shouldered his loaded muskets in turn and picked the savages off one at a time in quick succession, and despite their onsets he managed for a time to keep them at bay. At last they gathered together and made a desperate attack upon the cave, while the undaunted sailor clubbed them with the butt of a musket as fast as they came upon him. Then they withdrew and left him to pass the night watching and waiting for the assault to be renewed, but this was not attempted. Next day one of the savages appeared alone and unarmed, making signs which indicated that the tribe desired peace.

"Not only was this goodwill maintained, but the chief of the fierce islanders, full of admiration for the sailor's bravery, treated him with marked respect, and when more than a year had passed, during which no vessel apparently sighted the fluttering flag at the top of the broken mast, the seaman became almost reconciled to his strange fate, and took the chief's daughter as his wife. Watching from the beach one day, long after this, the sailor saw a vessel, and climbing up the mast seized the flag and raised frantic cries for rescue; for on seeing a ship once more his old longing to leave the island at once returned. Anxiously he watched, and then saw a flag run up to the mast of the ship, which told him that his signal had been observed—then the dull roar of cannon rang out over the waters. The vessel tacked and soon bore down towards the island, the sailor madly waving the tattered flag and uttering exclamations of delight, for he was almost beside himself at the near prospect of rescue.

"The vessel was brought to at some little distance from the island and a boat sent out, which was carefully steered through the breakers. Forgetting the treasure which he had concealed in the cave, and the friendly treatment which he had so long received from the tribe who knew of its whereabouts, the sailor rushed into the surf, and throwing himself into the boat bade the men pull back to the ship. When he was standing on the deck of the latter he recognised fully his own position. Above him floated the Spanish flag, fierce glances of hatred from all the crew were turned upon him, and to complete his discomfiture the commander who came forward to meet him was none other than Don Luego, of whom every Feringhee sailor had heard.

"Cast adrift by the crew of the galleon which he had commanded, Don Luego had been rescued and carried to Spain by a trading vessel, by which he chanced to be observed after suffering terrible privations at sea. He made his way into the King's presence, told his own tale of the mutiny of his sailors, and persuaded the monarch to put him in command of a fast vessel with which to return and, hunting them down, to restore the great treasure to the Spanish coffers. Strange rumours were heard by him when again in the southern seas of the galleon having been seen flying before the wind with another vessel pursuing it. After cruising about for a considerable time he had quite unknowingly come within sight of the island where the English vessel and the Spanish galleon had both been wrecked.

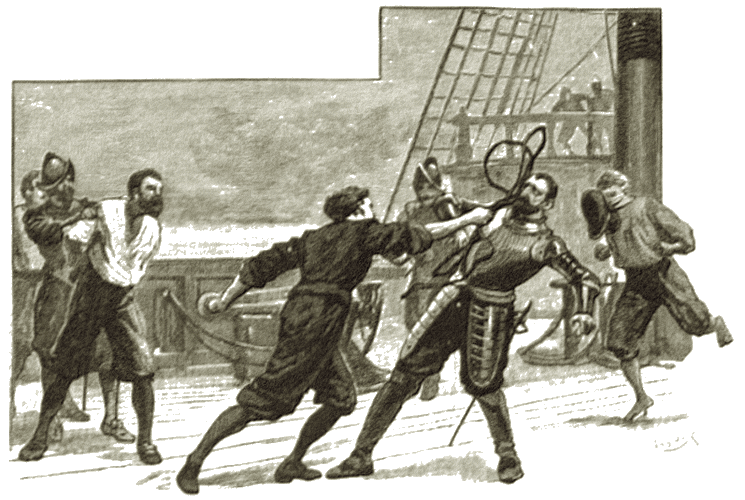

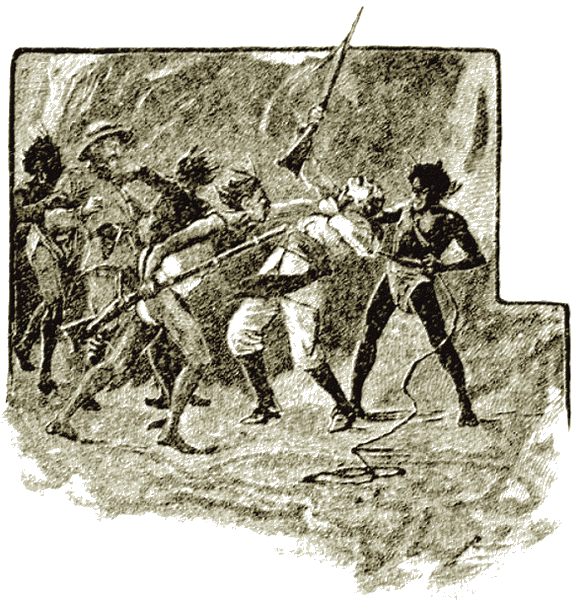

Mutiny!

"Pretending that hostilities had long ceased between the two nations, Don Luego endeavoured to get the rescued man to relate the story of his shipwreck; but the seaman, conscious of his danger, gave evasive answers, and asked to be landed upon the island once more. The Spaniard's suspicions were aroused, and he determined to keep the sailor on board as his prisoner while a number of men were sent ashore to see if anything could be discovered. They soon come back and reported that upon the beach they had seen portions of wreckage which had evidently formed part of a Spanish galleon. The Feringhee seaman was strictly questioned by the commander, but at first would say nothing. Stung at length by Don Luego's taunts, he pointed towards the tattered flag which still floated from the broken mast, and declared that it waved over a treasure belonging no longer to Spain but to him.

"Don Luego responded by threatening the hardy sailor with death unless he pointed out where the contents of the lost galleon were concealed. The seaman suddenly sprang for-ward, wrenched the sword from his interrogator's hand, and, cutting a way through the surprised Spaniards, flung himself headlong from the vessel's side, and struck out for the shore.

Cutting a way through the Spaniards.

"'Shoot him, men!' cried Don Luego, as the sailor's head emerged for a minute from the water, and instantly a volley from a hundred muskets whistled round the swimmer's head. He dived at once and swam under water, only coming up to take breath occasionally. A second and a third time the muskets were discharged, and then the savages —who had meanwhile gathered in a threatening band at the water's edge, on hearing the strange reports ring out—saw the sailor flung upon the coral beach. They bent over him, then raised a wild cry for vengeance, for the waves had cast at their feet the bloodstained body of the lifeless seaman.

"Landing from their boats, the Spaniards tried to force the natives from the shore, but were driven back time after time at the point of the savages' spears, till disheartened they leapt into their boats again and made for the vessel. Foremost among the wild horde which fought so desperately to avenge the murdered sailor was the daughter of the chief—for among this tribe the women fight in battle no less than the men. Her spear it was which pierced the traitorous Don Luego through as he led on the Spaniards.

"Soon after the ship sailed away the savages took up their dead, and carrying the sailor's body away they placed it in some secret spot, whither also they conveyed the treasure which he had hidden near the shore. There it is said to remain still, for though many daring explorers have set out to find it, none have ever returned to speak of their success, so the coolies say. Yet they would gladly convey the sahibs to the island and help them to overcome the savage tribe still living there, for they are bold seamen, and do not fear fighting whatever enemies may appear."

"I daresay," commented Denviers, with a glance of amusement at the coolies still shading themselves with the umbrella, "they would willingly go with us until the first savage appeared, then they would jump into the junk and make off, leaving us to defend ourselves as best we knew how. I have not the slightest objection to setting out for Formosa, but we will see to the craft ourselves and not trust to them. What is your opinion, Harold?"

"Let us go, by all means," I answered. "Between us we can manage the junk very well, and if we act cautiously we may come across this strangely hidden treasure; at all events, we might try."

Hassan was accordingly dispatched to the coolies to tell them what course we had decided to follow, and after some bargaining the junk was placed at our disposal. Before many hours had passed we were on our way to Formosa, little knowing what a strange adventure was in store for us, or how perilous a task we had so lightly undertaken. Before commencing our journey we carefully questioned the coolies as to where it was rumoured the treasure had been secreted, and, learning this, provided ourselves with everything we thought necessary for the enterprise. Our tent and possessions were left in charge of a wealthy mandarin, whom we fortunately met at Swatow, while we looked to the state of our weapons, for we fully expected to need them in the adventure before us.

"I THINK these Formosans are altogether too friendly, Harold," said Denviers, as we eventually reached the rough coast to which we had been directed, and our boat was being dragged through the blinding surf by a dozen fierce-looking savages.

"The sahibs need not fear," interposed Hassan, as he overheard this remark; "it is necessary that we should be led by them, for not otherwise could we see Wimpai, who is their head-man, so the coolies told me."

"I expect we could have managed very well without seeing him," I replied. "Would it not have been possible to have found the sailor's treasure, wherever it is hidden, without landing at a spot where these savages were evidently on the look-out?"

"Not so, by Mahomet!" answered the Arab. "The sahibs would certainly be slain if they attempted to do so without Wimpai permitted them."

"Well, come on then," said Denviers, as he made his way through the wreckage and huge fragments of coral lying on the beach: "I daresay we shall get out of this adventure as safely as we have others. Our new acquaintances are certainly making themselves quite at home with our possessions, before being invited even," he added, as four of them placed on their heads some pieces of cloth and a native basket filled with handsome beads, which Hassan had advised us to bring in order to propitiate Wimpai.

"They seem to consider us their prisoners," I remarked, as the savages marched on the right and left of us, while we strode on with our rifles shouldered.

"I don't relish the look of their knives," commented Denviers; "they are likely to do us far more harm with them than with the clumsy matchlocks which they now carry instead of spears. What a splendid set of fellows they are!"

The savages who inhabited this part of Formosa, so much avoided on account of its dangerous coral reefs, wore only a blue loincloth. Their hair was adorned with a number of brightly- coloured feathers, while across the shoulder of each passed a strip of scarlet cloth, reaching to the waist, supporting a plaited loop, into which was thrust the long-bladed knife which my companion mentioned.

For some time the tangled pathway which we traversed wound up the steep side of a mountain spur, running almost down to the edge of the raised coral beach. Forcing our way through the screw-pine, which obstructed us, we were soon passing under the shade of some bamboos and banyans, when Denviers motioned to some trees a little way ahead, and suddenly exclaimed:—

"Look out, Harold! These savage niggers mean mischief!"

I glanced carefully to where my companion directed me, and saw a number of match-locks pointed at us, while the heads of those who held them peered cautiously forth. We raised our rifles to defend ourselves, for we were completely covered by the shining barrels of the enemy, and for a moment fully expected that the lighted port-fires would be applied to their old-fashioned weapons. Seeing that we were closely guarded by the others from any attempt to escape, the savages came out from their lurking- places and advanced to meet us.

"It looks as if Hassan's incredible yarn is going to turn out true after all," said Denviers to me, aside; "at all events, there are several women carrying arms among those in front."

Upon getting close to us the savages passed on one side, and giving a fierce yell of triumph as they did so, turned and followed behind, while our guides or captors still inclosed us, except one of them who led the way. The burden-bearers soon after this disappeared, and we saw no more of the presents which we had brought.

"I expect we are in for it," said Denviers, as the savage led us towards a narrow gap in the heart of the mountain up which we had been toiling. Through this a number of the men passed in single file, and we were bidden to follow them. We halted irresolutely and turned round, only to see the wild horde pressing on behind, impatient at our delay.

"We must go on," said Denviers, "for we are completely surrounded."

The Arab pressed forward, anxious to be the first to test whatever danger confronted us, but my companion prevented this, and Hassan was compelled to take second place, while I followed him. We were absolutely in the dark before we had proceeded a dozen yards through the cleft in the mountain side, and then our worst fears were realized.

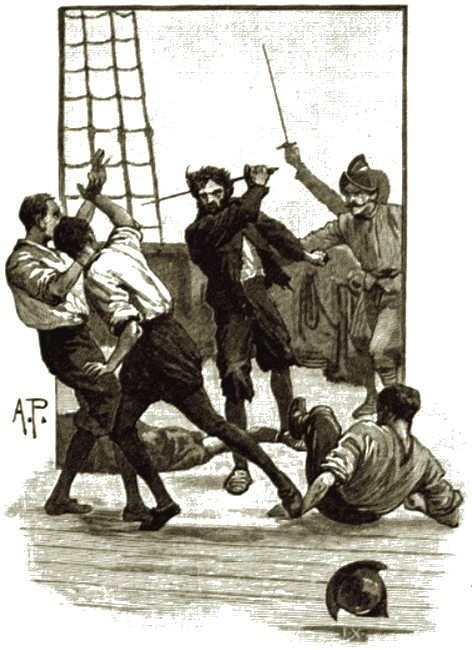

I heard a warning cry from Denviers, followed by Hassan's fierce answer, as the savages gathered closely about us where the passage or cave must have widened out, and then I felt the grip of a hand upon my throat and saw even in the gloom the fierce glitter of my enemy's eyes. With a thud I brought my rifle down, and the blow evidently told, for my throat was released, while the one who had attacked me fell heavily to the ground.

I felt the grip of a hand upon my throat.

Of all the adventures which we had met with, that one, during those few minutes of desperate fighting for our lives in the blackness about us, seemed the most weird and exciting. Once I heard the ring of the Arab's sword as it struck against the side of the rocky excavation, and a call to Mahomet for help came from his lips, while through it all Denviers was cheering us madly on in the blind conflict with our foes. I felt my rifle wrenched at last from my hands, and drawing a pistol from my belt thrust it between the glaring eyes of a savage and fired, sending him down at my feet. In a second that weapon too was snatched from me, and feeling hastily for the other I found it gone! Still another savage faced me, and I struck blindly at him with my fist, dealing a stunning blow which sent him spinning and laid my knuckles bare. With all my might I struggled to keep off the rope or thong which I felt was being bound about me, but the odds were too great, and with my arms lashed tightly to my sides I was dragged forward, wondering what fate was in store and why the savages did not kill us outright with their knives.

Evidently that was not their purpose, for as soon as I was helplessly bound no more blows were rained upon me, nor did my captors attempt to inflict further injuries.

How long I was hauled through the gloomy passage in the mountain would be difficult to conjecture, but eventually a stifling heat seemed to penetrate to where I was being hurried along, and a dull red glow appeared ahead which lit up the scene, showing what had happened and where we were.

Denviers and Hassan were both bound, the latter having one of his arms left loose, from which circumstance I concluded that it was broken, and this was subsequently found to be true.

The glowing mass ahead increased in its intensity, and cast strange shadows of the savages upon the jagged walls of rock which inclosed us on each side and rose to a height of more than twenty feet at the point we had then reached. We drew near to each other as we emerged into the lighter part of the mountain passage, and the savages ceased to drag us along, since they could watch our movements.

"We ought to be glad these niggers didn't try conclusions with their knives in that fight in the dark," said Denviers, as I got close to him and the Arab. Then, observing the latter's injured arm, he added: "You seem to have got the worst of the encounter with one of them, Hassan."

"Not so, by the Koran!" answered the Arab, promptly. "He who dealt that blow felt the edge of my sword, and lived but a second after he did it."

"Where are we being taken to, do you think, Hassan?" I asked, looking in surprise at the changing colours of the walls of the passage, which just there were tinted a bluish-grey, then crimsoned a little further on, until the long cave seemed to terminate in an enormous hollow surrounded by blood-red rocks which rose precipitously upwards.

"The sahib will soon see for himself," answered the Arab. "The savage tribe has chosen a safe retreat where none would expect to find living people, for, see! before us is the jagged side of a crater!"

We emerged from the cave to observe in front of us the cause of the intense heat which had been so oppressive while we were in it. A white cloud of smoke rose from the funnel-like hollow, and occasionally flickering red flames shot up and turned this to the same hue, while at times the cloud wore a blue colour, matching the changing tints of the lake of fire below. Round the interior of the great crater in which we were ran a rugged path of broken masses of rock, between which streams of lava lay, and over them we had to pass. Even as we went along, scarcely able to breathe, we saw a huge fragment of rock crash down into the depths below. This was followed by a grinding sound and a rumble like thunder; then high above us shot a shower of red-hot lava and stones, while we crouched under a projecting shelf of black basalt, and forgot that we were prisoners in the midst of such an impressive scene. When the stream of fire which darted upwards had somewhat subsided, our captives urged us forward, and on we went, tumbling and slipping over the dangerous rocks, which threatened every instant to give way beneath our feet. Even the savages became exceedingly cautious as we wound our way around the crater, and seemed to be getting nearer and nearer still to the molten fire below.

As he turned round for a moment to see if we were following, the foremost of our captors missed his footing, and, bound as we were, none of us could make an attempt to save him. Uttering an appalling cry of horror, he fell head first into the roaring furnace! We flung ourselves upon our faces and tried to shut out that weird scream of terror; then Denviers, prone as he was, worked his body forward upon a loose, overhanging rock, and stared down into the red sea of fire below.

He fell head first into the roaring furnace!

"The sahib is mad! Come back, come back!" cried Hassan, excitedly; whereupon the savages, looking more like demons than men, as their faces were lighted up by the glow of the lambent flames, seized hold of my companion and dragged him from threatening death.

"He has not fallen right in," said Denviers to me, calmly, as though his own danger had been a mere nothing; "the man is clinging to a projecting crag just above the flames. Hassan," he cried to our guide, "tell these savages if they will unbind me I think I can save him."

Half stupefied with fear and horror, our captors unbound the long rope which held my companion's arms to his sides, and at once he made a loop at one end of it and advanced again upon the projecting rock. Quickly the rope was lowered and, leaning right over, Denviers managed to reach the almost senseless man, for we saw him hauling the rope slowly in, and finally the head of the savage appeared before us, while the loose rock which upheld rescuer and rescued swayed ominously upon the solid mass which supported it. Scarcely were the two of them dragged back from the rock when over it went, and again a fierce shower of fire shot up, from which with much difficulty we protected ourselves.

The savage lay scorched and motionless for several minutes, then, struggling to his feet, he took one of the knives which another proffered and cut Hassan's bonds as well as my own. Again we moved forward and, conscious that this unexpected rescue of their companion had won for us the goodwill of all, we passed on, hoping that when we faced Wimpai, their chief, it would be turned to good account. Freed from our bonds so unexpectedly, we went on with more confidence than before, and at last saw another huge cavern facing us, upon entering which we found ourselves in the presence of the savage chief.

WE were not able to observe what the entire number of the savages was, since the cave into which we went led to several others where we caught glimpses of many of the wild tribe. We estimated that those among whom we were amounted to about five hundred, more than a half of whom were female warriors. Our appearance was the signal for the savages to raise excited cries, which continued till we stood before Wimpai, who was partly surrounded by a number of his armed women. The chief of our captors, who had received several severe burns and injuries through his fall, pressed forward, and telling first of our fight in the rocky passage, afterwards spoke of his own rescue by Denviers, so we learnt from Hassan. Wimpai rose and leaned upon his spear when the savage had concluded his account, and was evidently perplexed as to what course to pursue.

Hassan managed to explain our purpose in visiting the chief, and with an immobile countenance asked for us to be shown the hidden treasure, a request which brought forth a shrill laugh from those around. We could not understand what passed between Wimpai and the Arab, but the latter succeeded in producing a favourable effect by his persuasive words, for he turned to us eventually, saying:—

"Wimpai declares that between his tribe and those who carry the dragon banner to war there has been of late much fighting, which is the reason his people have sought this strange shelter."

"I should have thought these niggers could tell the difference between us and Chinamen," interposed Denviers.

"That is so," responded the Arab; "but the sahib forgets that in the memory of every wild tribe those who have injured them are never forgotten. Finding that we were not like the people with whom they have recently been fighting, those who took us prisoners thought we were the descendants of the fell Spaniards whom their traditions recall. I have told Wimpai that ye are of the same nation as the Feringhee sailor who married the daughter of one of their chiefs so long ago, and he promises that we shall see the treasure, and may take as much of it as we can bear away. Even now a boat is being got ready for us to enter, and a warrior woman is to accompany us down the strange stream which leads to the place where the contents of the galleon have long been hidden."

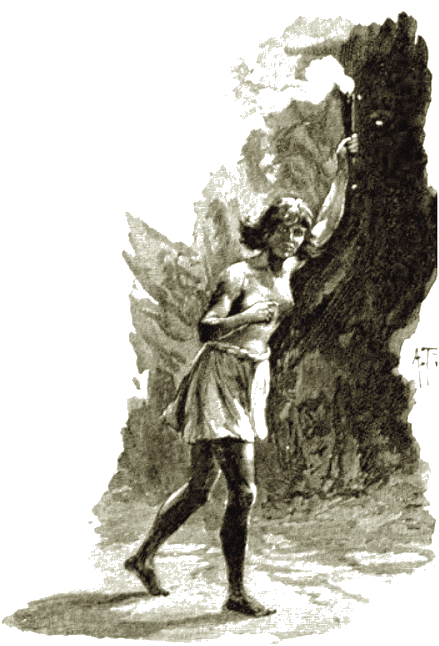

As the Arab finished speaking, we saw a woman approach, bearing a torch. Obedient to Wimpai's command, she moved towards one of the rocky passages, and motioned to us to follow. We advanced in single file behind our strange guide, and soon found ourselves in another of the great fissures, which seemed to traverse the heart of the volcano in all directions. Before us, by the light of the flaring torch, we saw a wide stream flowing between lava walls, the lofty top of these meeting far above our heads, and supporting long crystal prisms of a yellowish hue, which hung down in thousands.

We saw a woman approach.

The woman who was appointed to guide us pointed to where the native boat had been placed, and into it we leapt, eager to see the treasure taken from the lost galleon. Although there were two pairs of oars of peeled wood ready to hand, we had no occasion to use them, for the underground river carried us along with its steady current. We each held aloft a blazing torch, which the female warrior had thrust into our hands before she took her seat in the prow of the boat, where she sat facing us.

For more than an hour we passed on, watching the shifting lights of that wonderful scene, and the grey mist that stole upwards from the hot spring down which our little craft was floating fast.

At last we saw several narrow channels into which the stream was divided by its rocky bed, and down one of these we passed in devious turns until our new-found guide rose again in the boat and pointed to a jagged fissure which faced us. Denviers seized a pair of the rude oars and pulled the boat towards it, then leaping out he secured our frail conveyance, after which the woman handed to him a fresh torch, and we all advanced into the cave before us, vaguely wondering what treasure would be revealed to us.

All doubts as to the truth of the wreck of the richly-laden galleon off the coast about which Hassan had told us vanished as soon as ever we entered there. The various things which had formed the cargo of the vessel lay strewed in confused heaps about us. There were wedges of gold and bars of silver, discoloured by the fumes from the crater and the mists from the hot stream, while Spanish muskets, strange-looking pistols, and swords with richly-chased handles, and rust-incrusted barrels and blades lay about in piles. Among these weapons I observed a pair of pistols with gems studding their handles, and thrust them into my sash, besides a splendid sword, which proved very serviceable when polished up, especially as my own defensive arms had been taken away.

Hassan and Denviers followed my example, and then the latter remarked:—

"We may as well make the most of Wimpai's permission to enrich ourselves," and he raised several wedges of gold, which he proceeded to carry towards the entrance of the cave. Hassan and I assisted to load the boat, then we threw in a few more weapons which we thought might prove useful to us, and with a look of regret at the wealth we were forced to leave behind us we turned to leave the place. Just then Hassan moved away from us to another part of the cave, and a moment afterwards he called out to us. Going over to him, we found the Arab and the tribeswoman both looking intently at something lying upon the rocky floor.

"Every word of Hassan's singular story is undoubtedly true," I said to Denviers, in sheer amazement, as we stooped over the object and observed it in the torch-light. The wild tribe had carried and placed the slain sailor by the spoils of the galleon which he had claimed for his own in the very face of Don Luego, the Spanish commander.

There, before our eyes, was stretched the outline of a human form, above which was spread all that remained of the tattered flag that once had fluttered from the masthead of the ship which chased the Spanish galleon, and went down with it on the coral reefs of the Formosan shore!

Slowly we moved away from the spot towards where our boat was, and re-entered it. The task which we had undertaken, however— that of pulling against the stream, with such a weight of treasure as we had obtained—proved a most difficult one. Indeed, Denviers and I exerted ourselves to little purpose for some time, then found that the boat was slowly making headway. We reached the spot where the underground stream divided into its several channels, and then, by an unlucky accident, the prow of our craft was dashed against one of the many rocks which lay between. For a minute we entirely lost control of it, and back it drifted down one of the other channels. At this the female warrior rose, and thrusting the head of her long spear against the rock tried to assist us to get the boat back into the main stream before us. Our efforts were made in vain, for the bed of the narrow channel into which we had got sloped rapidly down, and its waters hurried us along at a speed which defied all our attempts to force the boat back. The woman had dropped her torch when she came to our assistance, and in the light of the solitary one still flaring as Hassan held it, I saw a look upon her face which startled me. She pointed before us, uttering a wild, despairing cry, which was drowned a moment after in a dull roar which struck upon our ears.

"Pull, sahibs; in Allah's name, pull!" cried Hassan, who was looking ahead at the danger which we faced. "If the boat cannot be stopped from drifting on before a few more hundred yards are gone over, we are lost!"

We gripped the rude oars again, and strained till our arms ached, but still the relentless current bore us on. I gave another glance at the danger ahead, then Hassan wildly exclaimed:—

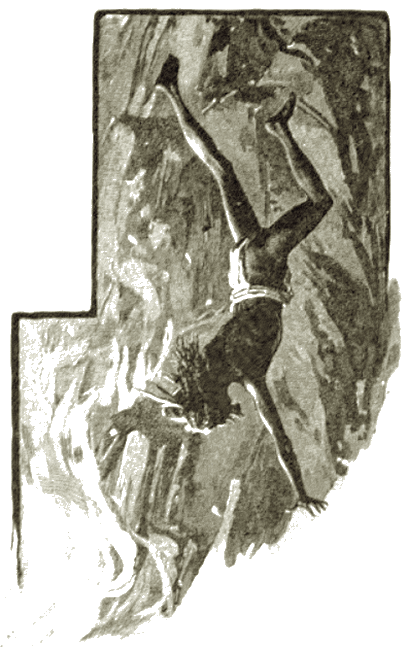

"Allah and Mahomet help us! We are on the verge of a cataract!"

On the verge of a cataract!

"Throw the treasure overboard!" cried Denviers, and each of us worked desperately to free the boat of what we had been so eager to obtain. Into the stream we cast the wedges of gold and Spanish arms, and scarcely had our purpose been accomplished, when the boat, lightened of its heavy cargo, was caught up by the rushing stream, swirled round, and then borne madly forward at a rate which brought another despairing cry from the woman's lips.

"Pull with all your might with the stream, Harold!" said Denviers to me, as we drew close to where the roaring waters were leaping down. "Pull, pull, it is our last chance!"

We both knew that if we failed to shoot the rapid ahead we should be sucked down and drowned. We tugged at the oars together, then amid a cloud of blinding spray our boat seemed to hover for a moment over the tumbling waters, then shot forward and left the danger behind.

"We are saved, thank Allah!" cried Hassan, and as we ventured to look round we saw the wonderful escape which had been ours. Swiftly we were carried along by the stream, which began to widen out as it passed between the precipitous sides of a vast ravine.

"Daylight at last!" I exclaimed, with a feeling of relief. "I wonder where we are now being hurried towards."

For a considerable time the stream kept on its rapid course, then grew less violent, and we floated down it gently at last, until we were carried to where we saw the river flowing into the sea, when we at once sprang out upon the rough coral beach.

The Formosan woman hastened away along the shore, making for the distant cave by which we first entered into the strange haunt of her tribe, while we followed slowly after her, having, drawn the rude boat high up on the beach.

"Well!" said Denviers, when at last we found our junk, after walking several miles along the coast, and prepared to launch it into the sea in order to leave the island. "We lost the treasure after all, but still we have something left to recall this strange adventure at times," and he drew from his sash the Spanish sword which he had thrust there. After examining it I passed to him the arms which I had taken from the cave. The pistols, although proving useless, were fine specimens of workmanship, and as richly chased as the jewel-studded hilt of the sword which I had also obtained.

"Mahomet has well rewarded the sahibs with such treasures," interposed Hassan, gravely, "and has not forgotten their slave." We glanced towards his waist as he spoke, and saw that the Arab had certainly taken care to arm himself well from the treasures of the lost galleon, for he bristled with swords and poniards like a small armoury.

"Come on, Hassan," said Denviers, with an amused smile at the Arab's weapons, "Mahomet evidently looks with high favour upon you."

We pushed the junk through the surf, then entering it, put out for the distant coast of the mainland, which we reached in safety.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.