RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Administered by Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Shafts from an Eastern Quiver, George Newnes, 1893, with:

"Margarita, the Bond Queen of the Wandering Dhahs"

THESE stories ... introduce the lover of sensations to a new writer, who is not at all unworthy to be placed upon the same shelf with Mr. Conan Doyle. He certainly contrives to give the three heroes of this book—the two Englishmen, Frank Denviers and Harold Derwent, and their marvellous Arab servant and good genius Hassan—as many hairbreadth escapes and other adventures by sea and land as can well be packed into a volume of less than three hundred pages.

Mr. Mansford appears to be most at home in Persia, Afghanistan, and India. But he does not confine his literary attentions to the more strictly Eastern countries; on the contrary, one of his most thrilling stories tells of the experiences of the fortunate three among Papuan wreckers, and another relates the escape of an exile from Siberia.

Undoubtedly Mr. Mansford has the gift of the story-teller, and besides, he uniformly writes like a scholar. The illustrations of the book, though small and unpretentious, are admirably executed, and enhance the piquancy—though that was hardly needed—of the letterpress.

The Spectator, 1 December 1894

"THE Cingalese declare that the Queen of the Dhahs is a Sahibmem," said Hassan—meaning by this expression an Englishwoman.

"I don't think that can be true," responded Denviers; "it is hardly possible that any civilized human being would care to reign over such a queer race as those just described appear to be—"

"The Englishman is wrong in what he says," interrupted an indolent-looking native, "for I once saw her myself!"

"You!" I exclaimed, "then tell us what you know about this queen." The native was however, by no means disposed to conversation, or indeed to do anything that disturbed his serenity.

From Southern India we had crossed over to Ceylon, and after a somewhat prolonged stay at Colombo, struck into the interior of the island. We visited Kandi, and having travelled for some days in the hilly district which surrounds it, arrived at the palm- covered hut of a Cingalese labourer, where, in spite of his protests, we stayed for a day to rest ourselves. Round the stems of the palms about us we saw, high up, that dead brushwood had been placed, by the rustling of which at night our unwilling host could tell if his few neighbours contemplated robbing him of the fruits of his toil. The only work, however, which he seemed to do was to stand at the door of his hut and gaze vacantly at the plantation of palm trees which he owned, and to shake his head—usually in the negative—whenever we attempted to entice him into a conversation.

"Well," said Denviers, looking with annoyance at our host, "if this Cingalese is too idle to tell us the full facts, L suppose we had better find them out for ourselves." Then turning to the man he asked:—

"How far is the district over which these strange Dhahs are said to wander?" The native pointed slowly to the north and then answered:—

The native pointed to the north.

"The Dhahs were wandering afar in the forest when last I saw them, which was fully a day's journey from here, but the sun was hot and I grew tried."

His remark certainly did not convey much information to us, but before an hour had elapsed we set out, guided only by the forest, which could be seen far away in the distance. Hour after hour passed until at last evening came, and even then we were only entering upon the fringe of the great forest which rose before us, and seemed to shut out the sky as we wandered into the thickness of the undergrowth and gazed up at the lofty tops of the trees, which bent each other's branches as they interlaced one with another.

We stopped at last to rest and to refresh ourselves, after which we reclined upon the ground, facing a wide clearing in the forest, where we laid talking idly for some time, until the voice of Hassan warned us that someone was approaching. We listened attentively for a minute, but no sound could be heard by us save that of the fluttering of the wings of some bird among the branches above.

"You heard nothing, Hassan," said Denviers, "or else you mistook the rustling above for someone wandering in the forest glade."

The Arab turned to my companion and then responded:—

"Hassan has long been accustomed to distinguish different sounds from a distance; the one which was heard a minute ago was caused by a human foot." He pointed to a tangled clump a little to the right of us. as he continued:—

"Listen, sahibs, for the sound of footsteps is surely drawing near. From yonder thicket the wanderer will doubtless emerge."

Presently a sound fell upon our ears, and a moment afterwards we heard the crackling of dead twigs as if someone was passing over them.

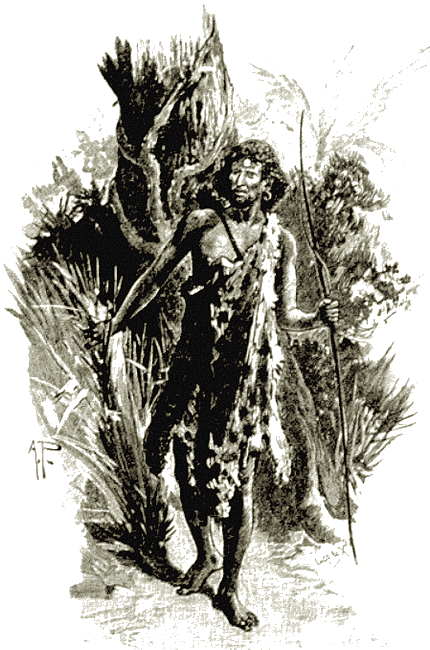

"The feet of the one who is approaching us are uncovered," volunteered our guide, whose keen sense of hearing was vastly superior to our own, and its accuracy was again proved fully, for, pushing aside the undergrowth which hindered his path, there stepped out upon the level track before us a singularly well- formed being, whose whole appearance was that of a man in his primitive, savage state. He was fully six feet in height, and wonderfully erect, his nut-brown skin forming a warm setting for the rich, dark eyes which so distinguish Eastern races. His black hair clustered thickly above his forehead, on which we observed a circular spot, crimson in colour, and much resembling the pottu which Shiva women daily paint above their brows as a religious emblem. As Hassan had already said, the man's feet were bare of covering, while the single garment which he wore was a brightly-spotted panther skin, which passed over the left shoulder to the right side, and then hung down carelessly to the knees. In one hand he carried a stout bow, and the band which crossed his body over the right shoulder supported a quiver which hung gracefully behind. A savage, and in such a rude garb, the man seemed almost grand in his very simplicity.

"A Dhah!" exclaimed Hassan, quietly. "We have, indeed, met with good fortune."

"A Dhah!"

Again we heard the brushwood crackle, and a second man, resembling the first in appearance and dress, came forward, and together they held a conversation, interspersed largely with the gestures which play so prominent a part in the language of barbaric tribes.

"What can they be searching for?" Denviers asked Hassan, as the men seemed to be closely examining the trunks of several of the palm trees.

"1 cannot tell, sahib," responded the Arab. Then he continued with a warning movement:—

"Hist! there are others coming, and they are bearing loads with them."

Through the brushwood we next saw several Dhahs advance, each carrying upon his head a huge bundle of some twining plant belonging to a species which we had not observed hitherto during our wanderings in Ceylon. From its appearance we likened it to a giant convolvulus, for, while the pliant stem was as thick as a man's arm, there hung from it huge leaves and petals resembling that flower in shape. We moved cautiously into the undergrowth behind, thus getting a little farther away from the Dhahs, and, lying with our bodies stretched upon the ground at full length, we supported our heads upon our hands and.narrowly watched the scene before us.

Following the commands of the Dhah whom we had first seen, one of the others deftly threw upwards a long coil of the climbing plant, which, on reaching a part of the trunk of one of the palm trees some distance above his head, twined round the stem. The rope-like plant was then fastened to another palm tree some little distance in front of the first, and lower down. Continuing this process in all directions we saw them construct before our astonished eyes a wonderful tent, the leafy green roof and sides of which glowed with a massy setting of white and crimson flowers. The front almost faced us, so that the interior of the tent was disclosed to our view, and then this strange tribe next placed within the tent a number of rich skins of various animals killed in the chase, the whole effect being viewed with satisfaction by the Dhahs when at last their labour was finished.

"What a curious tent!" Denviers exclaimed. "These Dhahs are indeed a strange people."

Just as he spoke a messenger came to them through the brushwood, whereupon the men who had constructed the tent threw themselves down on either side of it Within a few minutes we heard the sound of a number of footsteps approaching, and then a band of Dhahs stepped out from the brushwood through which the first had come, and joined those resting by the tent. Following these, we next saw a number of others, who ranged themselves before the men in a standing posture, and as they did so we judged from their attire that they were women.

Their raven hair was loosely twisted and threaded with pearls, while pendants of the latter hung from their ears. The garb which covered their forms was made of similar skins to those which the men wore, but more elaborately wrought, in addition to being gathered at the waist by a glittering belt made of the plumage of beautiful birds Here and there a dark-eyed and lightly-clad child could be seen standing among the women. From time to time the glances of the Dhahs were turned in the direction whence they had entered the forest clearing, and the sound of their voices then ceased. They were evidently expecting someone, and we, remembering the strange rumour as to the nationality of their queen, began to watch the brushwood with considerable interest, being anxious to see her as soon as she emerged. That some event of unusual moment was about to take place upon her arrival we felt sure, from the disappointed looks which overspread the Dhahs' faces each time that their expectation of her coming was not realized.

"What do you think is about to happen?" I whispered to Denviers, as we kept quite still, fearing lest our presence should be discovered.

"Something strange, no doubt," he responded, "for I notice that the crimson mark which we saw upon the men's foreheads also adorns those of the women, and seems to have been recently placed there."

Here Hassan interposed, in his usually clear, grave tone:—

"It is very rarely, indeed, sahibs, that the Dhahs have been seen wandering on the borders of the forest, for they usually keep within the wild and pathless interior; so, at least, your slave heard in Kandi."

"Well," I added, "we certainly have much to be thankful for, since there is every chance of our remaining here unobserved, and witnessing whatever ceremony is about to take place. The sun has not long set, and yet the moon is up already. The network of branches above us keeps out its light to some extent; still we shall be able to see clearly what transpires."

"It will be unlucky for us if these Dhahs happen to discover our whereabouts," said Denviers, "for a shower of arrows shot from their stout bows towards us would make our present position anything but a pleasant one."

"They will not see us, sahib," continued Hassan, "unless we incautiously make some noise if anything unusual happens. They are not likely to cast many searching glances into the shadows which the trees cast, for they are apparently preoccupied, if we may judge from the excitement which they are evidently trying to suppress. We certainly must remain perfectly still when the queen appears, for thus only shall we see without being seen ourselves."

"That is easy enough to say, Hassan," I replied; "but in such a moment as that which faces us, we may easily forget to be cautious."

"Don't you think it would be a good plan if we were to separate a little from each other?" asked Denviers. Our guide seemed strongly in favour of this plan, and while I remained in the position which had been occupied hitherto, Denviers moved a few yards to the right, and Hassan about the same distance to the left of me. The latter, however, found his new position would readily expose him to observation, and when he had communicated this fact to me by signs, I beckoned to him to return to my side, which he did. Denviers, however, remained where he had gone, and this circumstance, slight as it was, led a little later on to a most unexpected result. The silence which just before we had observed among the Dhahs occurred again, and watching narrowly the brushwood, we saw emerge from it the one whom they were eagerly expecting. As our eyes rested upon this last comer we were indeed startled, for before us was the Queen of the Dhahs, and we recognised in that moment that the rumour concerning her was true!

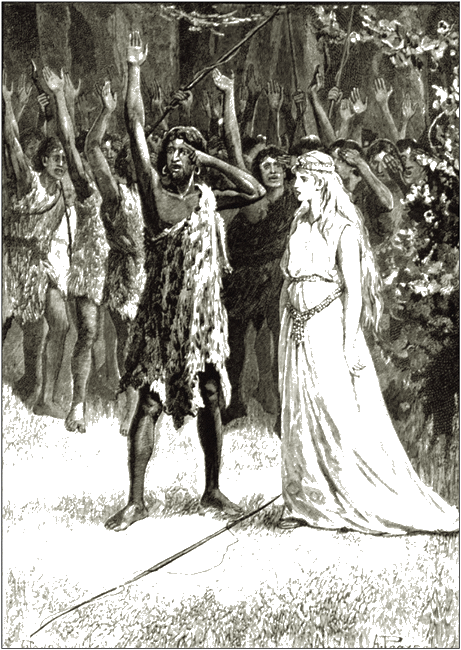

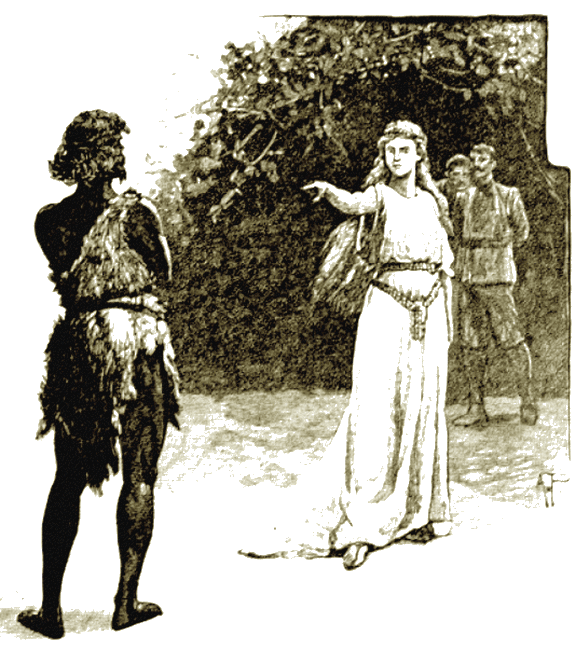

"SHE comes! Margarita!" burst from the lips of every assembled Dhah, as the queen slowly advanced and passed between her subjects, who lined the path leading to the tent. As she moved amid them they bent low, while here and there a warrior Dhah pressed with his lips her trailing garment as she passed. Reaching the tent, the queen turned and faced the excited throng of subjects grouped round it, and then we saw more distinctly her features and the attire which she wore.

The age of the queen was apparently less than twenty, her clear, fair skin forcibly contrasting with the dark complexion of her subjects, whom she alone resembled in the colour of the soft, full eyes with which she glanced upon them. A look almost of sadness overshadowed her face, which all the adulation which she received from her subjects could not entirely banish. Her form, which was above the medium height, was clad in a flowing robe of a wonderfully soft and silky-looking material, woven possibly, we thought, from the inner bark of some tree. Its loose folds were bare of ornament, save that the queen wore a girdle over it thickly interwoven with pearls as white as those of Manaar, of which a profuse number also braided her light flowing hair, meshes of which partly concealed her forehead. When the queen stood in silence before her subjects, after the greeting which they had given her subsided, there issued from among the Dhahs that one whom first we saw in the forest. Prostrating himself before her he afterwards rose, and, having bent low his head, began:—

"Margarita, white queen of the dusky race whose habitation is the pathless forest, hail! Here, upon the border which limits thy domains, we pledge anew to thee the promise of fealty, of which the crimson star upon our foreheads is the token. By it we swear to thee that thy foes shall be our foes, and that over us, thy slaves, shalt thou have the power of life and death." Then, turning to the Dhahs, who throughout this speech had maintained a death-like silence, he asked:—

"Swear ye this by the crimson star of blood which is placed upon your brows?"

The last word had scarcely left his lips when the subject Dhahs rose and, placing upon their foreheads their left hands, held aloft the right above their heads as they cried:—

"By the crimson tide, which rules the life of man, we swear!"

"We swear!"

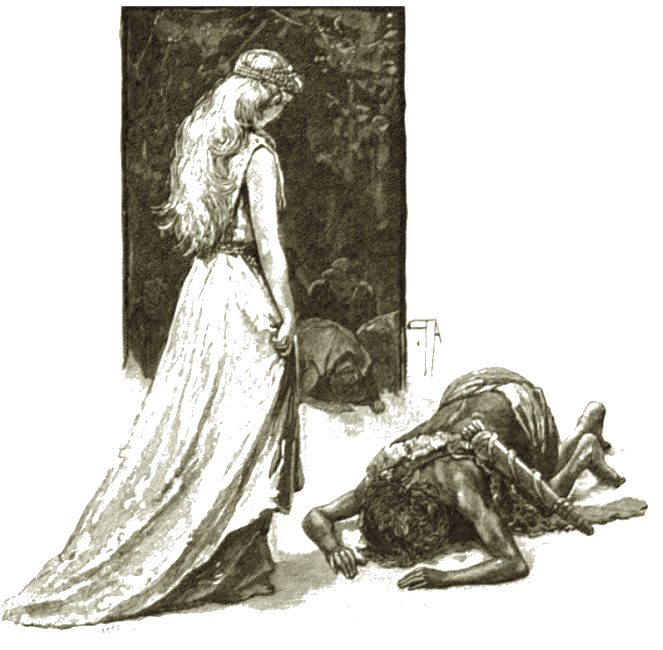

We watched the strange scene intently as each of the Dhahs, in turn, came forward and fell prostrate before the queen, then gave place to those who followed. The Dhah who had administered the oath remained near the queen until the ceremony was concluded, and seemed to number the subjects as they came forward. Then he fell before her and, for a second time, kissed the hem of her robe.

Prostrating himself before her.

Smiling gravely upon him, the queen extended to him her hand. Pressing his lips fervently upon it he rose, then, turning to those around, he exclaimed:—

"All have not sworn fealty. One among us has not taken the oath, and at sundown he did not bear upon his forehead the sacred mark!"

There was an ominous frown apparent upon the brows of the Dhahs as these words were uttered, and when he added:— "Ye know the penalty which such transgression deserves; how then judge ye?"

Each man's hand gripped his bow in a threatening manner, while even the faces of the women grew terribly stern. By one of those assembled was uttered a cry which leapt from lip to lip, for it was immediately caught up by all:—

"Death to the false one! Death when the day shall dawn!"

A gleam of satisfaction, one almost of savage joy, passed over the face of the Dhah who stood beside the queen as he added:—

"The sentence upon the traitor is a just one; do thou then confirm it!" He turned as if about to seek himself for the one who was the cause of the tumult, when the momentary silence was strangely broken. Upon our ears was borne the sharp whizz of an arrow shot true from a tightly-strung bow; then the Dhah who had just finished speaking, with a wild cry that pierced the forest, threw his arms up as if grasping the empty air, and fell dead at the queen's feet!

The Dhah fell dead.

"Look yonder, sahib!" whispered Hassan, who was still beside me, "there is the one who sent forth the deadly shaft!"

I turned my gaze hastily in the direction which the Arab indicated, and saw Denviers struggling with a fierce Dhah from whose hands he was trying to wrest a bow, and who had hidden in the brushwood near him without being observed hitherto! They were seen in a moment by the assembled Dhahs, and, with a wild rush, the latter poured down upon the combatants, seizing them as they still grasped the bow.

"Hassan," I cried to our guide, "come on, we must get Denviers out of the hands of this horde somehow!" We dashed across the intervening space, and made a brief but desperate attempt to release our companion. It was as useless as it was rash, for we were directly afterwards dragged, in spite of our struggles—as well as Denviers and his opponent—into the open glade, close to the dead body of the man lying there.

"We are betrayed!" cried one of the Dhahs. "The white spies have been led hither by the traitor among us that they may learn our strength, and then return with a force to destroy us! One of our number has already fallen; shall we not slay the captives over his dead body?"

A fierce cry of assent rose from the others, as they fitted each a shaft to their bows and took deliberate aim at us as we were held fast by our captors. I saw the face of the queen grow pale as she rested her eyes, first upon the fallen Dhah and then upon us. Had men of her own race come that they might destroy the tribe which obeyed her slightest word? She made an imperative gesture, which caused the Dhahs to hold their arrows undischarged, though they still kept their bows bent, waiting eagerly for her to utter the word of command to slay us.

"Stop!" she cried, in a commanding tone. "Upon your foreheads ye wear still the pledge of obedience to me, with whom rests alone the power of life and death. Ye shall have justice to the full: I will hear what they can say in their defence, but if wantonly they have caused life to be taken, white though they be, I swear unto ye that they shall surely die."

The Dhahs shifted their arrows from the bowstrings and seemed reluctant to give us even this short respite. I looked into the queen's face and read there that her threat against us was no idle one. She commanded the women and most of the men to retire—leaving us still held fast by our captors.

"We are not cowards," said Denviers, calmly, to her. "Hear what we have to say, and then decide our fate. Bid these savages release us from their grasp—we shall make no attempt to escape, I pledge my word." The queen glanced coldly at him as she responded:—

"Be it as ye say." Then, turning to the Dhahs, she continued: "Take them within the tent, and then retire. Remain within an arrow-shot from here, and if ye see one of the prisoners attempt to escape, slay him and spare not" We were conducted into the queen's tent, and there released. As the Dhahs withdrew Denviers turned to Hassan, and said:—

"Bid this savage who shot the arrow explain that we know nothing of him." The queen looked sharply at us, and then pointing to Hassan, asked:—

"Who is this whom ye have brought into the forest?"

I answered for us, saying:— "He is our guide, with whom we have been wandering for some time. Why do you mistrust us, since you have ample proof that the fallen Dhah was shot by your own subject there?" and I pointed to the man, who, for a moment, had thrown himself down in the tent.

"Speak!" she commanded him. "Why did you shoot forth the winged messenger of death?"

To our surprise the man rose and confronted her boldly, as he answered:—

"Am I not a warrior? Can I not bend the bow and endure hardships better than anyone among the tribe over which thou rulest? Was not I prince of these Dhahs until the day when thou tookest possession of my right? Thou hast despised me and looked kindly upon another, wherefore have I sworn to refuse to take the pledge of fealty to thee when the time came round, and to stretch him dead at thy feet. Deliver me into the hands of the tribe if thou wilt, but thou art powerless to bring back life to thy favourite!" He stopped and drew himself up defiantly before her. The eyes of the imperious queen shone brightly with the fierce resentment which the Dhah's words roused in her.

"Darest thou then to confront thy queen so?" she asked, scornfully. "May not I choose whom I will upon whom to bestow my favours? Coward that thou art to shoot the shaft secretly, because thou darest not face thine enemy as a brave Dhah ever does! Thy crime has nearly cost these other prisoners dear; and I, ruling as I do this tribe without the exterminating feuds which distinguished it under thy misgovernment, doom thee to death. At sundown to-morrow shalt thou die; till then thou shalt live, scorned by the race upon which thou hast brought this stain." She moved to the front of the tent, and then we saw the Dhah dragged away by those whom the queen quickly summoned.

"To-morrow shalt thou die!"

We were bidden to rest ourselves upon the piles of soft, rich skins which were spread there, and having promised to secure our safety, the queen, whose anger gradually subsided, observing the inquiring glances which we turned towards her, said, in a low tone:—

"The deed which ye have seen enacted to-night has smitten me sorely. For ten years have I lived among these Dhahs, for to-day is the anniversary of that upon which I came to them, and so it is that ye chance to see their promise to obey me renewed. To- morrow it is expected that I, too, will take in turn the oath, by which yearly I have sworn to them to remain in this forest until the seasons change and change again. At midnight to-night my last promise expires, and for a few brief hours I shall not be their bond queen. By your glances I judge that ye would learn my history. Strange as it is, I must narrate it briefly, for, because of the death which ye have witnessed, I now have a request to make which may sound unusual upon your ears."

THE dark eyes of the queen glanced at us as she began her story, the sequel to which we did not at all anticipate:—

"I was a mere child when it chanced that I strayed from the hut which my English parents inhabited on the borders of this forest. Of them I know nothing. I remember the cry of surprise which came from the lips of a Dhah woman when she found me, and then carried me among her tribeswomen to show to them. It is forbidden among us for a Dhah to ever pass beyond the limits of this forest, and so it transpired that, knowing nothing of other races, they were astonished at my strange whiteness. I have heard that at first they contemplated my death, thinking that my presence would bring dire misfortune upon them. The woman who found me averred, on the contrary, that my appearance betokened great advantages to the tribe, as I was sent to dwell in the forest as a goddess. Afterwards, believing this, they paid me the most abject worship for years. When I grew older I longed to escape, but they were determined that I should not do so, and compelled me to take an oath to stay with them for a year, which I have renewed as often as the promise expired. Finding that I disliked the adoration which they paid to me, they deposed their prince—he whose hand shot the fatal arrow, as, alas! ye saw—and although for a time I refused to accept the position, I was eventually made their queen—even as I am now.

"Many times I desired to leave them, but of late that wish has grown feeble, for he, whom ye know now lies lifeless before the tent, bent his dark eyes, and looked into mine, which returned his glances. One day I thought to raise him even as a prince to my side, for all the tribe trusted in him as much as they disliked the one deposed. Now that he is slain, the wish to depart has again re-entered my breast, and ye, who are of the same kindred as I, surely ye will aid me? How came ye hither, on foot or otherwise?"

"We left our horses on the edge of the forest," said Denviers, "but we did not expect to be so long absent from them. How wilt thou depart from these Dhahs? Surely they will avenge themselves upon us, for they will assuredly think that we have influenced you to desert them."

The queen paused for a minute, then answered:—

"I could not bear to leave them openly, for I have grown to be almost one of themselves, and they are dear indeed to me. I will accompany ye to where your horses are tethered; and waiting there for me I will come to ye again upon the steed which has never known saddle."

The plan of escape seemed simple enough, but the slightest mishap might bring us into conflict with the whole tribe of the Dhahs, who would doubtless be infuriated if they thought that their queen was lost to them through us, as Dcnviers had suggested. It seemed to us a strange termination to our adventure, but in obedience to a gesture from the queen we rose, and, accompanied by her, passed the guards in safety. As she emerged from the tent, the queen bade us wait for her for a minute, and stopping, we saw the woman bend down sadly over the silent form lying there under the trees, which half shut out the midnight sky. Her hand touched the arrow and gently drew it forth—tipped with blood! Then placing it within the upper folds of her dress she passed silently on through the clearing, and so accompanied us to the spot where our horses were, whence she departed.

Her hand touched the arrow.

"I am afraid that this affair may yet turn out badly for us," I remarked to Denviers, as we untethered our steeds and waited for the queen's return. "Where shall we make for when we start?"

"For the hut of the Cingalese, which we left some time ago," he responded. "It will afford her some shelter, and we can keep watch outside."

He had scarcely finished speaking when we saw the queen riding towards us upon a snow-white steed. As the moonlight touched her spotless robe and her floating hair, with the pearls which adorned it, she seemed to us to be more like some vision than a living reality. I had just time to notice that she now carried the weapon of the tribe over which she had so long ruled—a bow—and that across her fair shoulders was slung a quiver of arrows, when a sudden cry rose from the forest, and at the same moment Hassan exclaimed:—

"Quick, sahibs! The Dhahs are upon us!"

We leapt upon our horses and dashed away from the forest just as a heavy shower of arrows narrowly missed us. Hassan went on in front, while Denviers and I galloped on either side of the queen. Glancing back at the Dhahs I observed that they were massed already upon the margin of the forest, the flight of their queen having become rapidly known. The women raised a mournful and appealing cry of entreaty to her to go back to them, and, glancing at the queen, I saw that her face was wet with tears. We heard the hoarse shouts of the warrior Dhahs when they found that their arrows fell short, but they did not dare to pass the limits of the forest beyond which their strange law forbade them to go.

We rode on for some hours at a rapid rate, then, on nearing the hut of the Cingalese, Denviers leapt down and succeeded in awaking its sole occupant, who was induced to vacate it. The queen dismounted and entered the hut wearied, as we thought, with the long ride, for the dawn had come before we finished our journey. Hassan secured the horses, and soon after we were all lying at a little distance from the hut fast asleep in the shade of some giant ferns.

The morning was far advanced when we awoke, but hour after hour passed and the door of the hut remained closed. Becoming uneasy, at last I ventured to open it The queen had disappeared!

"Denviers!" I shouted. "Come here a minute!"

My companion hastened towards the hut, and was considerably surprised to find it empty. Glancing round it we saw against one of its thin palm leaf sides an arrow projecting. Going close to it we found roughly scratched beneath it a message to us, which said simply:—

"The Queen of the Dhahs could not rest away from her people and the forest where lies her dead lover!"

We stared at the writing incredulously for a minute or two, then a sudden thought occurred to me:—

"Hassan!" I shouted, "see to the horses." The Arab went slowly to the spot where he had secured them, but hastily returned saying, in an animated tone, somewhat unusual for him unless when excited:—

"Sahibs, the white steed is no longer there!" and he looked gravely at us as he spoke.

"Well," said Denviers, as Hassan finished speaking, "this has been a strange adventure from beginning to end. How could such a woman care to spend her existence with those Dhahs? It seemed curious to me at the first, but after seeing her and observing the contrast between her and her subjects, I am still more surprised."

"The Dhahs are known throughout Ceylon," interposed Hassan, "for the honour which they pay to their queen, and that may influence her to remain with them; besides, they are a handsome race, very different to such as this man," and he pointed to the Cingalese, who was again vacantly staring at his plantation of palm trees.

"What do you think will become of the man who shot the Dhah, sahib?" asked Hassan, as he turned to Denviers. My companion was silent for a moment, then responded:—

"I really cannot say. He is doomed to die at sundown to-day, but I daresay someone will intercede for him with the queen." Then, holding out towards the Arab the arrow which we had found within the hut, he continued:—

"Take care of that, Hassan, for if we are able I should like to keep it as a memento of this event."

The Arab examined it closely to see what constituted its value, and Denviers, thinking that it might disappear like sundry other lost treasures of ours, added: "It is a poisoned arrow, and if put in that sash of yours might prove very dangerous." Hassan understood the hint, as subsequent events proved, and, calling upon Mahomet as a witness to his integrity under such trying circumstances, carried it cautiously away and placed it among our baggage.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Administered by Matthias Kaether and Roy Glashan

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.