RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Shafts from an Eastern Quiver, George Newnes, 1893, with:

"The Daughter of Lovetski the Lost"

THESE stories ... introduce the lover of sensations to a new writer, who is not at all unworthy to be placed upon the same shelf with Mr. Conan Doyle. He certainly contrives to give the three heroes of this book—the two Englishmen, Frank Denviers and Harold Derwent, and their marvellous Arab servant and good genius Hassan—as many hairbreadth escapes and other adventures by sea and land as can well be packed into a volume of less than three hundred pages.

Mr. Mansford appears to be most at home in Persia, Afghanistan, and India. But he does not confine his literary attentions to the more strictly Eastern countries; on the contrary, one of his most thrilling stories tells of the experiences of the fortunate three among Papuan wreckers, and another relates the escape of an exile from Siberia.

Undoubtedly Mr. Mansford has the gift of the story-teller, and besides, he uniformly writes like a scholar. The illustrations of the book, though small and unpretentious, are admirably executed, and enhance the piquancy—though that was hardly needed—of the letterpress.

The Spectator, 1 December 1894

"OUR journey seems to have no end, Harold," remarked Denviers, as he lashed the horses which drew our sledge over the dreary plain; "for a week we have been pressing on, night and day almost, in the hope of coming across the hut near the road over which the exiles pass. If that mujik told us the truth, we certainly ought to have seen it by this time."

"We have had a long, desolate ride since we parted with him," I assented; "yet the snow lies in such drifts at times that we can hardly be surprised to find ourselves still driving onwards."

A desolate ride.

"See, sahibs!" exclaimed Hassan, as he pointed to where the snow-clad plain was at last broken by a distant forest of stunted pines. "There is surely the landmark of which the mujik spoke, and the peasant woman's dwelling cannot be far off."

After wandering through the outlying provinces of China, we determined to visit the vast plains beyond, being anxious to see a Russian mine. To all our requests for such permission we met with refusals, until Denviers pressed a number of roubles into the hand of an official, who eventually helped us to effect our purpose, after evincing some reluctance. Staying a few days after this at a peasant's hut, we had been fortunate enough to win his goodwill, and it was in consequence of what he told us that we promised to undertake our present expedition.

No sooner did the keen eyes of Hassan discover the forest far ahead than we dashed onwards quicker than ever, as our exhaled breath froze in icy particles and the biting wind struck right through the heavy sheep-skin wraps which we had purchased on entering Russia. Away across the snow our foam-flecked horses sped, until we saw the blue smoke curling upward in the frosty air from a low log hut, situated so that the pine forest sheltered it somewhat from the icy winds.

"Someone evidently lives here," said Denviers, as he beat with the handle of his whip against the low door. We heard a footstep cross the floor, then the noise of a bar being removed as a woman opened the door cautiously and peered into our faces. Bent as she was with age, with hair that hung in white masses about her shoulders, there was an unsubdued look which rested upon us from her dark eyes that contrasted forcibly with the dull, patient glance of the average Russian peasant.

"Who is it crossing the plains? Are you servants of the Czar?" she asked, in a tone of hesitation at our unexpected appearance, and glancing strangely at Hassan, who had secured our steeds and joined us.

"We are travellers crossing the Siberian wastes with our guide, and come to you for shelter," I answered, although we had a deeper purpose in visiting her.

Siberia!

"It is yours," the woman replied, and having shaken our sheepskin wraps, we entered the hut and accepted the invitation to gather about the pine-wood fire which burnt in one corner of the rude dwelling.

"You are not a Russian peasant?" remarked Denviers, in a tone of inquiry, for the woman spoke English with some fluency.

"I am not, for my people are the Lost Ones, of whom you may have heard," she answered, with a dreary smile.

"We do not understand you," Denviers responded, as we waited for her explanation.

"If you were men of this country my words would be lucid enough. Among all those who were overcome in the many Polish struggles for liberty, none have ever returned who once trod the road by which the exiles passed to join those whom we call Our Lost."

"You have a motive for living here?" I remarked quietly, watching attentively to see what effect my words would have upon her.

"I am friendless and alone, choosing rather to dwell here within sight of the way to Tomsk, than in the great city from which I came. The Czar is merciful, and permits this."

"Then the mujik who directed us here was mistaken," I persisted. "He related strange stories to us of fugitives, whom the peasants whisper—"

"Hush!" she cried, looking nervously round. "What was the mujik's name?"

For reply I placed in her hand a scrap of paper, upon which the man had scrawled a message. She glanced keenly at us after reading the missive, then answered:—

"He may be mistaken in you, for you are Englishmen, and do not understand these things. A piece of black bread—what is it that it should be denied to an enemy, even of the Czar, who has escaped from the mines and wanders for refuge over these frozen wastes?"

"You may trust us fully in this matter," said Denviers. "We have given our word to the mujik to render all the help we can."

"It is a terrible day to traverse the plain," the woman replied, as she rose and threw open the rough door to the icy blast, which was only imperfectly kept out before. We followed to where she stood, then watched as she raised her hand and pointed at a distant object.

"See!" the woman cried, bitterly; "yonder pine cross marks the spot where a brave man fell, he who was the lover of the daughter of Lovetski, one of our Lost Ones. By it, before the day is ended, will pass the long train of exiles guarded by the soldiery and headed by the one who hates to see that monument of his own misdeeds, but fears to remove it, for, persecuting the living, he dreads the dead." She closed and barred the door again; then, after some hesitation, spoke of the one to help whom we had gone so far.

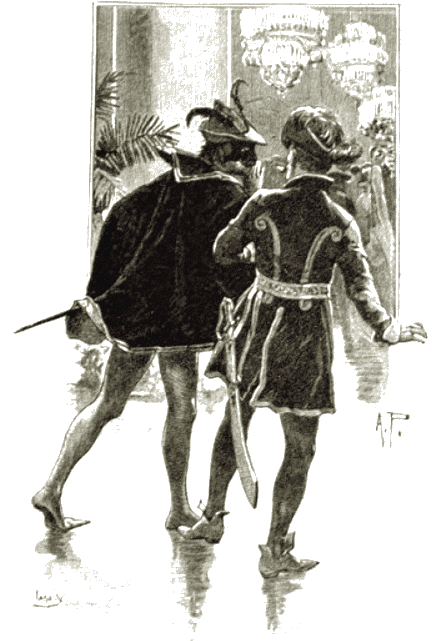

"It was the night of a masquerade at the Winter Palace, long to be remembered by many, for on the following day another rising of the Poles had been planned to take place. A number of the leading citizens of St. Petersburg were involved in it, but so well apparently was their secret kept, that they ventured to accept the invitations issued to them. Amid the mad revel the plotters moved, making occasionally a furtive sign of recognition to each other, or venturing at times to whisper as they passed the single word which told of all their hopes and fears—'To-morrow!' Chief among them was Count Lovetski, who murmured the watchword more hopefully than any of those concerned whenever his keen eyes searched out those sworn to take part in the revolt so near at hand.

"For three hours the gay crowd moved through the salons, then Lovetski, as he leant against a carved pillar, saw one of the revellers who was clad in strange attire approach several of the masqueraders and smilingly whisper something in their ears. At last the Count saw the stranger move close to himself, and a moment after he heard a mocking laugh from behind the black mask, as the unknown one stooped and uttered the preconcerted word. Lovetski looked doubtfully at the man's sombre garb, for the glance from his eyes was by no means reassuring.

"'To-morrow!' repeated the masker. 'Count Lovetski, you do not respond. Have you forgotten?'

"'Lower your voice, or we shall be heard by others,' said the Count, with a warning gesture. 'Who are you?'

"'One of the three hundred citizens who are sworn to revolt to-morrow. The appointed day is fast drawing near, for in ten minutes the great clock will chime the midnight hour, and then, Count Lovetski—Siberia!'

"His listener stared in blank amazement, then, regaining his composure, he replied:—

"'So the plot is discovered? I am no coward. When is it settled for me to set out?'

"'At the last stroke of the hour a drosky will await you at the main entrance. The palace is guarded by the soldiery. The others do not start immediately; you are the leader, and will be ready, doubtless.'

"'Quite,' answered Lovetski, for he knew resistance would be useless. He quietly passed his sword to the masker, who took it, smiled again, and disappeared in the crowd. One by one the followers of the Count were singled out by the strange messenger of the Czar, and when the masquerade was over three hundred exiles followed the track of the sledge in which their leader had been hurried away a couple of hours before them on the long, dreary journey to Tomsk.

"Lovetski was refused the privilege of communicating his whereabouts to his wife, who shortly after this event died, leaving their daughter to the care of strangers. Before long a rumour reached the capital that the Count had been shot while attempting to escape in disguise, and this was eventually found to be true.

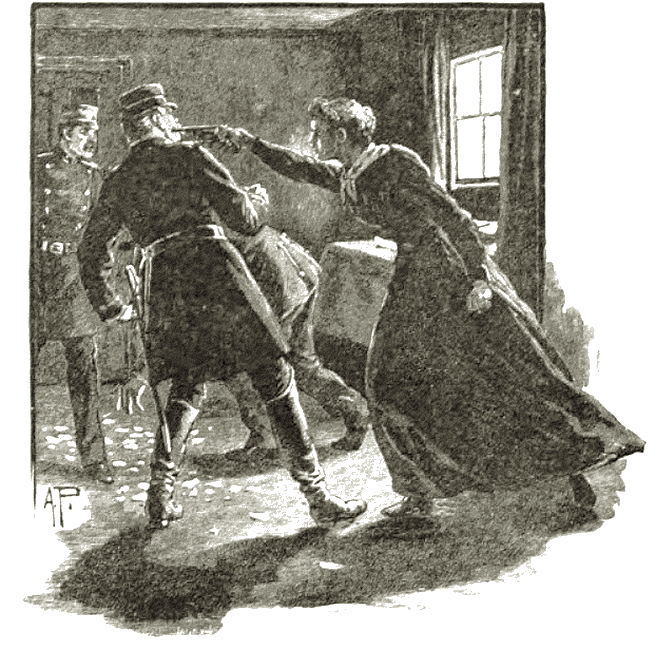

"Scarcely had Marie Lovetski reached womanhood when she joined a political movement, fired with a mad resolve to avenge her father's death, and within a year her name appeared among those on the list of suspects, whose every action was closely observed. A Russian officer of high rank, Paul Somaloff, who had more than once made her an offer of marriage, begged her to remember the fate which overtook Count Lovetski, but the bare mention of it only made the woman more inexorable. The end which everyone foretold soon came, for, seated one day in the midst of treasonable correspondence, Marie Lovetski was surprised by three gendarmes, who burst into her apartment. She tore the letter into fragments before they could stop her, then scattered the pieces over the floor. One of the gendarmes, motioning to his companions to pick them up, moved towards her and attempted her arrest. For one moment the woman stood at bay, then thrust the cold barrel of a pistol into the gendarme's ear.

She thrust the cold barrel of a pistol into the gendarme's ear.

"'Raise but a hand or move an inch nearer and I will shoot you!' she cried, warningly. Her would-be captor shrunk back, and before he had recovered from his surprise Marie Lovetski darted past him towards the door. She seized the handle to wrench it open, then saw that all was lost. The door was locked and the gendarme had removed the key. There was a fierce struggle, in which one of the officers was dangerously wounded, but eventually they secured her, and within two months Marie Lovetski set out to traverse the same dreary road over which the Count had gone long before when she was a mere child.

"Ivan Rachieff, the masquerader who had whispered into Count Lovetski's ear the fate to which he was consigned, was at that time a young attaché at the Court of the Czar. The zeal which he displayed in hunting down the autocrat's enemies rapidly brought promotion, so that when Marie Lovetski was exiled he had risen to be a general of the Russ army, and specially chosen for the duty of heading the Cossacks who conducted the exiles over the Siberian wastes, while among his subordinates was Paul Somaloff, who held a position scarcely inferior to his own.

"Convicted of a double offence, Marie Lovetski was condemned to walk the whole of that wearisome distance among criminals bound for the mines, while the political exiles were somewhat less harshly treated. General Rachieff had been warned that a band of discontents had threatened to attempt the rescue of the prisoners, and special powers of life and death were granted to him. By long forced marches he hurried the exiles on, scarcely giving them a few hours' rest each night when they arrived at their halting-places on the route.

"It was with a deep feeling of sorrow at his inability to lessen her sufferings that Paul Somaloff glanced many times on the way at Marie Lovetski. In spite of the strange position in which he found himself, his love for the woman was by no means lessened, but increased each day as he saw to his dismay how plainly her strength was failing as he looked upon the woman's haggard countenance, who was wearily dragging her limbs forward over the frozen wastes. One day Marie Lovetski's condition became so serious that Somaloff begged General Rachieff to order the fetters which bound her wrists to be removed, receiving in reply a refusal as contemptuous as it was decisive. All that day the exile's secret lover walked moodily on, racking his brains for some method by which to save the woman from dying before even the terrible journey was ended.

"Not far from the hut in which you are now resting, the weary exiles were halted that night, and soon sank down in the log building into an exhausted sleep. After a severe conflict between his love and his allegiance to the Czar, Paul Somaloff rose, and, stealing carefully among the unconscious ones, he bent at last over the form of Marie Lovetski, stretched upon a straw pallet.

"'Marie,' he whispered softly, as he cautiously awakened her. 'Tis I, Paul Somaloff—I come to save you.'

"He remained by the woman's side till he had deftly removed the manacles from her wrists, then stole to the entrance as she silently followed him. Once he was outside the log building, Somaloff made for where his general's horse was stabled, and quickly untethering it led it forth. For one brief moment he clasped the exile to his breast, then lifted her into the saddle and placed the reins in her hand with a few hurried words as to the best course to pursue to avoid pursuit.

"Suddenly Paul Somaloff felt a heavy hand grip him by the shoulder, and turning round he found himself face to face with Ivan Rachieff, his general! At the same time the woman was dragged from the horse and held by three of the Cossacks.

"'Your traitorous plan was well thought out,' said Rachieff, as he smiled in derision at its failure. 'Paul Somaloff, you have broken your oath to the Czar, and I swear you shall die for this.'

"'You may do your worst,' replied the young officer. 'You would not listen to my repeated appeals for a slight act of clemency for Marie Lovetski, and so have turned a loyal subject of the Czar into a traitor.'

"'Insolent!' cried General Rachieff. 'At sunrise you shall be knouted to death.'

"'Coward that you are,' retorted Somaloff, 'that is a punishment you dare not inflict upon one who wears a decoration given to him by the august Czar. I am a soldier, General, and, at the hands of my comrades, will die a soldier's death.'

"'So be it,' answered Rachieff, calmly; 'you shall be shot at sunrise,' and he motioned to the soldiers who had gathered about him to take Somaloff into their charge, then turned on his heel and strode away, humming an idle air.

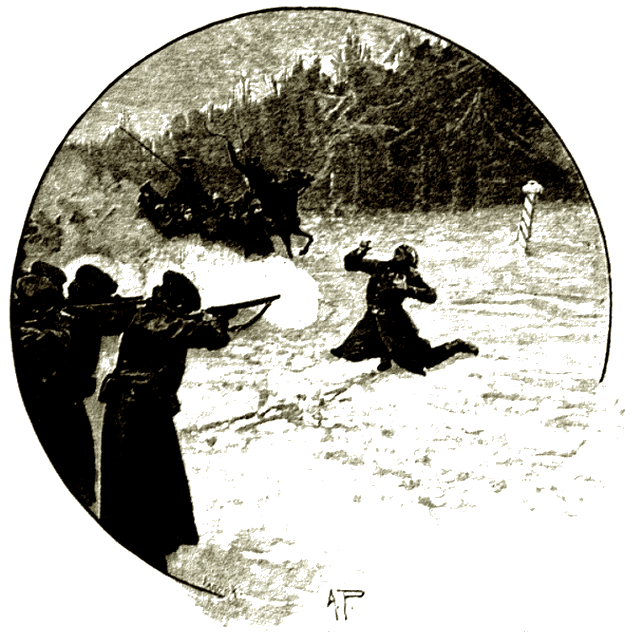

"The grey morning had scarcely dawned when brave young Somaloff was blindfolded and led forth to be shot in sight of the exiles, while the woman whom he had failed to save looked helplessly on.

"A few minutes afterwards, Paul Somaloff knelt on the snow- covered plain, the report of a dozen rifles rang out on the morning air, and the exiles saw his arms raised as he clutched convulsively at his breast, then he fell forward, dead!

He fell forward, dead!

"The wild, despairing cries of the exiles were quelled with threats of the knout, and then the prisoners were hurried on, as they had been for so many days and weeks past. Ten days later a large number of Polish insurrectionists, ill-armed, and accompanied by a throng of even worse accoutred peasants carrying a red banner, flung themselves upon the line of march, and made a futile effort to break through the soldiers who guarded the exiles. The trained troopers of the Czar thrust them back and, as they broke and fled into the forest, chased and cut them down like sheep, till the snow turned to a crimson hue with their hearts' blood.

"The exiles made desperate efforts to avail themselves of the opportunity to escape which the confusion presented. Those who were unbound fought with branches, which they tore from the stunted trees, while the others madly thrust the shackles upon their wrists into the faces of the brutal soldiery, who knouted or cut down men and women indiscriminately. Long will that massacre be remembered, and the dreadful sufferings which the survivors endured at the command of Ivan Rachieff. When at last Tomsk was reached, only a handful of decrepit exiles passed into the city out of all those who started on the long journey."

"And Marie Lovetski?" I interrupted, "did she live to complete the distance, or what was her fate?"

"It was reported that she was cut -down during the massacre," the woman replied, slowly; "for nothing has been heard of her since by General Rachieff, although her body could not be found among the slain."

I glanced at the woman thoughtfully as she concluded her story, and Denviers, who had listened in silence throughout, asked:—

"Where is Marie Lovetski? You are aware that she is alive—nay, more, you know her place of concealment."

Surprised at the directness of the question, the woman involuntarily rose, and then, seeing that we suspected the fugitive was hidden in the log hut, she answered:—

"Marie Lovetski is not here, yet if the mujik has rightly judged your courage, within a week he will see your sledge return with one more occupant than when it started. Once she is carried there her escape is assured, for—" She stopped suddenly and pointed to the door. We listened attentively as the sound of footsteps drew near, then a heavy blow smote the barred entrance and a voice exclaimed:—

"Open, in the Czar's name!" The woman's face turned ashy pale as she muttered faintly:—

"That is the voice of Ivan Rachieff, who is again in command of the exiles," and she drew away the heavy bar to admit him. We rose to our feet in an instant as the door was flung open and General Rachieff entered and stood before us.

FOR A moment the Russian officer stared at us without speaking, then throwing back his heavy sealskin cloak and revealing the military garb which he wore beneath, he asked the woman, sternly:—

"What does the presence of these men in your hut mean?"

"We are travellers, who have asked for shelter. Our guide is an Arab; we are Englishmen," responded Denviers, quietly but decisively.

"Spies, I do not doubt," said Rachieff, as he bit his heavy moustache.

"My word is accustomed to be believed," replied my companion, sharply. "If you doubt what I have said, read that," and he flung a package containing our passports upon the table as he spoke.

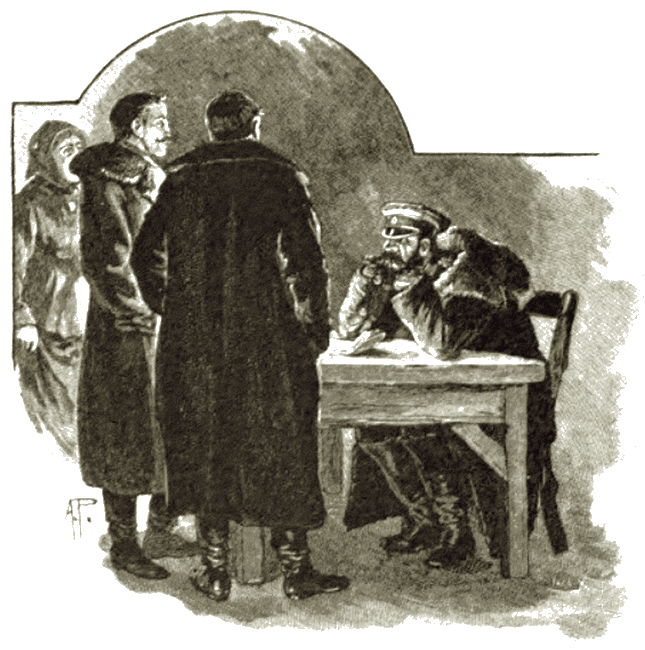

The officer took out our passports, which we had been careful to obtain. He glanced through them, then tossed the papers on to the table again as he remarked, in a morose tone:—

"You would not be the first Englishmen who have made their way into the Czar's territory only to discredit it."

"You have chosen a curious method of displaying your pleasantry," retorted Denviers, glancing sternly at the heavy- bearded Russian who had so wantonly insulted us. Rachieff drew a chair to the table, and, sitting down, leant his head upon his hands, narrowly scrutinizing our features.

Narrowly scrutinizing our features.

"I saw some horses and a sledge in the shed without," he continued; "are they yours?"

"They are, answered my companion, laconically.

"Where was your last stopping-place before you reached here?" Rachieff asked, as if he were examining some prisoners.

"We are neither Russian subjects nor refugees," Denviers replied. "You may save your inquiries for others, since we have no intention of satisfying your ill-timed curiosity."

My companion turned his back to Rachieff, and raising a blazing piece of pine-wood which had fallen, tossed it again among the glowing embers, taking no more notice of the discomfited officer. Rachieff was nonplussed; he frowned heavily, then rising, moved to the door. He turned as he held it partly open, saying:—

"If you were a Russian gentleman instead of an English spy, I would call you out for your insolence to an officer in the Czar's service."

I saw the blood mount to Denviers's forehead as he snatched the driving whip which Hassan held and, striding forward, struck the Russian a blow across his face with it.

"If I were an exile, no doubt you would knout me for that," he said, quietly. "You can do nothing as it is, since our papers are in order, except fight me."

"I am in command of the exiles," answered Rachieff. "They are now passing yonder; when the halting-place is reached to-night I will leave my subordinate in charge of them and return here with an officer as my second. If you are not a coward you will be here awaiting me at mid-day."

"I shall be here," replied Denviers. "Choose your own weapons; you have brought this meeting about entirely unprovoked, and to- morrow you or I will fall."

"Adieu till then!" cried Rachieff, with a bitter smile of hatred, then he turned his face away, upon which was a long livid mark where the whip had fallen, and we saw him stride towards the exiles passing over the plain before us.

"Ivan Rachieff is one of the most skillful duellists with sword or pistol in the Czar's army," said the woman, who had been an attentive observer of all that passed between the two men. "He will kill you with as little remorse as he ordered Paul Somaloff to be shot by the soldiers."

"Paul Somaloff!" exclaimed Denviers. "Ah! I had forgotten his fate for a moment; but to-morrow, when Rachieff and I stand face to face, I will surely remember it."

"Allah and Mahomet help the sahib," cried Hassan. "If the bearded Russ should chance to win, he shall fight the Arab afterwards."

"Never mind Rachieff, Hassan," said Denviers; "we must at once make our plans for the purpose of helping Marie Lovetski to escape from Siberia. Whatever happens to me, she must be saved at all hazards."

"Where is the woman concealed?" I asked the one who was our hostess.

She rose and questioned us:—

"Will you swear by the memorial which I have raised over Paul Somaloff's resting-place never to speak of what you may see in the strange hiding-place to which I may conduct you?"

"We will," I answered briefly, as Denviers joined in assenting.

We lost little time after Rachieff's departure, but drew together and discussed the probabilities of various plans succeeding, and at last decided on that which seemed to promise success. The dusk rapidly closed in upon us as we sat in thoughtful conversation, after which the woman rose, and, having scanned the plain near the hut as well as she could in the gloom, motioned to us to follow her.

Hassan remained in the hut while we set out, and making our way through a part of the pines and firs close to the dwelling in which we had sought shelter, we found ourselves groping blindly along, following each other like phantoms in the darkness which enveloped us. So far there was little need for the woman to have sworn us to secrecy, for neither going nor returning did we get a glimpse of anything likely to indicate the spot to us again at any future time. At last we felt what appeared to be a rough flight of stone steps beneath our feet, then our guide lit a pine-wood torch which she carried.

Holding up the flickering light before us, the woman led us into what we conjectured to be one of the catacombs of an ancient city. On both sides of us as we moved along the red flare of the pine-wood revealed many bodies of the dead, each stretched in a niche cut for it in the red rock, while at intervals between these we saw the resting places of others distinguished by various strange emblems. One of these niches was silently guarded by two carved figures of horsemen with their white steeds caparisoned, and each of the riders held in his uplifted hand a sword such as the Damascenes use.

"A strange resting-place that," I remarked to Denviers, as it stood out weird and ghastly in the light of the torch. "No Russian soldiery ever wear such accoutrements as are depicted there, I am certain."

"They wear the garb of boyars of the time of Ivan the Terrible," our guide said, as she pointed to the mounted horsemen. "Where the pine forest about us is now there stood more than four hundred years ago one of the many cities built by that extraordinary monarch, but it has long been blotted out, and the Russ have forgotten its very existence. None now know of its catacombs save those of us who form a secret band, and whose object is to help the exiles who may escape and seek shelter and a safe hiding-place. Even now it would be impossible for you to find the one you seek, and if you wish to go farther it must be done blindfolded, or I will not lead you."

We stood by the strangely carved horse-men, and having consented to the woman's request, allowed her to fasten our sashes securely over our eyes; then, led by her, we slowly advanced through what appeared to be a labyrinth of ways until we were stopped by someone who spoke to the woman in a calm, grave tone. There was a whispered conversation between the two, directly following which our eyes were uncovered, and we found ourselves facing a strangely-robed hermit. His long white beard fell almost to his waist, contrasting forcibly with the black garment which covered him, while his high forehead and the steadfast look directed towards us seemed to be in keeping with the hermit's strange surroundings. A heap of blazing pine-wood lit up his retreat and served to lessen the intense coldness of the air.

We found ourselves facing a strangely-robed hermit.

"You are Englishmen, and have promised to help Marie Lovetski to escape from here to our next station of refuge," he said. "Since the day when she fled she has been hidden in various of our secret places. Six months ago she was brought here, yet so dangerous is the risk that we have waited for the mujik's messengers, telling us that all is safe for her to be conveyed there. He says in his message that you can be trusted, and doubtless your passports will help you to accomplish the task more easily than Russ or Pole could do. We trust, then, in your honour, that once Marie Lovetski is in your keeping, you will die in her defence rather than surrender her to the horrors of a mine."

We explained to the hermit the difficulty which the approaching duel between Denviers and Rachieff might cause, and discussed with him the possibility of overcoming it. Denviers was emphatic in his determination to meet the Russian on the morrow, and so it was arranged that at a certain hour Marie Lovetski should leave the catacombs and secretly watch the result of the duel. If Denviers escaped uninjured we were to mount our sledge and make for the spot where she would be stationed, and hiding her beneath the wraps, to start on our long journey back to the mujik who had intrusted us with the task of saving her.

"You will, of course, allow us to see this exile?" Denviers remarked, as soon as everything was arranged. "It was for that purpose that we were brought here tonight."

"Then your visit has been made in vain," was the unexpected reply. "It will be time enough for you to do so if your duel with Rachieff is successful."

We endeavoured to overcome the hermit's objection, but, although the woman who had guided us there spoke strenuously on our behalf, the strange guardian of Marie Lovetski was not to be persuaded from following his own cautious plan. Finding our protests useless, we consented to be blindfolded once more, and were led back through the catacombs into the forest, and before long we had entered the log hut again. There we threw ourselves on our sheepskin wraps in front of the pine-wood fire, and laid down upon them to sleep; then, when daylight came, the woman awoke us and we passed the morning vaguely wondering what the result of the duel would be.

Denviers urged upon our guide, Hassan, and myself the necessity of attempting to save the woman so long shut up in the dismal catacombs, and at last I gave a reluctant consent to do so if he fell, instead of making an attempt to avenge him. The Arab stolidly refused to do this, and justified his position by numerous quotations from the Koran, while declaring that Mahomet would certainly come to my companion's assistance, which, in spite of the gravity of his position, provoked a smiling retort from Denviers. Little did we know what the termination of the fight would be, or the strange part in it which Marie Lovetski was to have.

"HARK, sahibs!" exclaimed Hassan. "Although noon has not yet come, the Russian is approaching to keep his promise to fight."

We threw open the door of the hut and distinguished the ringing sound of the bells of a distant sledge. A few minutes after this the cracking of a whip and the neighing of horses were heard, and finally we saw the sledge appear before us. There were three occupants, and as it drew near we distinguished among them General Rachieff as the one who was urging on the horses. The conveyance dashed up to the hut; then one of the officers sprang out and restrained the animals, while a second, who carried a couple of swords, followed close behind Rachieff, with whom Denviers was soon to try conclusions.

"The weapons are here," said General Rachieff, frigidly, as Denviers approached and bowed slightly. "There is no time to lose: we fight with swords as you see. Choose!" and he motioned to his second, who held them out. Following out the plan which we had determined to adopt, Hassan quickly placed our horses in our own sledge and drew them a little ahead, so that the conveyance should be ready for us to enter when the duel was ended, if my companion did not fall in the encounter.

"We fight there," said Denviers calmly, as he motioned to the part of the plain to the right of where Hassan had already stationed our sledge.

"As you will," responded Rachieff indifferently, and, accompanied by his second, he moved to the spot Denviers pointed out. There the usual formalities were settled by the other officer and myself, whereupon the two duellists made ready and waited for the signal to begin, which fell to my lot to give.

I fluttered a handkerchief in the biting air for a moment, dropped it, and the swords were rapidly crossed. The reputation which Rachieff had won as a duellist was certainly well deserved, since his feints and thrusts were admirable, while Denviers, whose coolness in critical circumstances never deserted him, acted mainly on the defensive, parrying his enemy's lunges with remarkable skill.

More than once the duellists stopped as if by mutual consent, to regain breath, then quickly facing each other again, fought more determinedly than ever. Rachieff saw that for once he had apparently met his match with the sword, and grew by degrees more cautious than he had been when the fight began; yet repeatedly he failed to completely ward off the quick lunges from my companion's weapon, and I saw the crimson stains of blood which marked where the sword point had touched him. Then he rained in his blows with lightning speed, pressing hard upon Denviers several times, and glaring furiously at him, while his distorted features showed plainly enough the mark of the blow he had received from the whip the day previous.

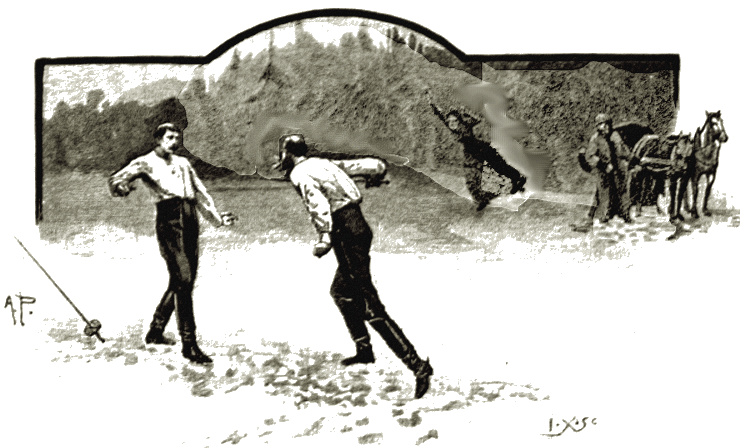

"Rachieff wins!" cried the Russian's second, and I saw, to my dismay, Denviers's weapon suddenly twisted from his hand and flung into the air, while an exultant exclamation burst from Rachieff's lips as he rushed upon his defenceless opponent! Before he could make use of the advantage which he had unexpectedly gained, Marie Lovetski uttered a wild, mournful cry, and started forward from the pine forest, standing pale with momentary fear before him!

He rushed upon his defenceless opponent!

The superstitious Russian stared incredulously, his sword-arm dropped to his side, while he gasped out:—

"Lovetski's daughter, and yet she is surely dead!"

Taking full advantage of the Russian's dismay, Denviers instantly flung himself upon his foe, dashing him backwards to the ground. Kneeling upon his enemy's chest and gripping him by the throat, as he held the sword he had seized before the startled Russian, my companion hissed in his ear:—

"Yield, or you are a dead man!"

The Russian's face turned to a purple hue as he almost choked for breath, then he muttered brokenly the exiled woman's name.

"She is living!" cried Denviers, as he lowered the point of the sword till it touched the Russian's breast. "Swear that you will not attempt to hinder her flight, and I will release your throat."

General Rachieff raised his hand in sign of assent, for his voice had failed him. Denviers rose, whereupon the Russian staggered to his feet, then, mad at his defeat, moved over to where his sledge was.

"Get the woman into our sledge," cried Denviers to me. I started forward to where Hassan was; we snatched up the exile and immediately drove off.

"After them, men!" cried Rachieff, caring nothing for his promise. "We will take Marie Lovetski, or shoot her down!"

"Never trust a Russ, sahibs!" exclaimed Hassan, as he lashed our horses on, while our enemies followed furiously behind. "The only way to secure his silence would have been a sword thrust through the false one's heart."

Away our sledge was whirled across the plain, faster and faster still, yet Rachieff, whose horses were more numerous than our own, drew gradually nearer. Marie Lovetski, who had forgotten her alarm now that Denviers was safe, turned her pale-set countenance towards our pursuers, and, as she did so, the report of a pistol rang out, while a bullet whizzed past her head! I saw Rachieff holding the smoking weapon in his hand as Denviers cried to me:—

"If he fires again, I will shoot him like the dog that he is!"

"No," cried Marie Lovetski, snatching a pistol from my sash before I could prevent her. "Rachieff slew Somaloff, my lover, and I will avenge him." She pointed the weapon full at the Russian, and I barely had time to brush her arm aside before the frenzied exile fired. Fortunately, the shot was deflected, and Rachieff was saved from the fate that he certainly deserved.

"Shoot their horses!" exclaimed Denviers, and as our own dashed along he leant over towards the pursuing sledge and fired at the foremost of them. The animal reared for a moment, then fell dead, throwing the rest into confusion. Out the Russians sprang, and cut the traces through, and having in this way speedily managed to disencumber their steeds of the dead one, they immediately began the pursuit again. We waited for them to get near again, then fired in quick succession and brought down their other horses, in spite of the bullets which the Russians rained upon us, and which, fortunately, struck none who were in the sledge. Baffled in their pursuit, we saw our enemies standing knee-deep in the snow watching us as we dashed along.

"Well," remarked Denviers, as we slackened our speed at last, "we have had a strange running fight, such as I least of all expected."

"The sahibs have saved the woman," said our guide. "Their slave the Arab believes that even the Great Prophet would approve of what they have done. The promise to convey Marie Lovetski to the mujik's hut will now surely be kept."

And so it came about, for the daughter of Lovetski the Lost lived to find freedom hers on another soil and under another flag.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.