RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Shafts from an Eastern Quiver, George Newnes, 1893, with:

"The Hunted Tribe of Three Hundred Peaks"

THESE stories ... introduce the lover of sensations to a new writer, who is not at all unworthy to be placed upon the same shelf with Mr. Conan Doyle. He certainly contrives to give the three heroes of this book—the two Englishmen, Frank Denviers and Harold Derwent, and their marvellous Arab servant and good genius Hassan—as many hairbreadth escapes and other adventures by sea and land as can well be packed into a volume of less than three hundred pages.

Mr. Mansford appears to be most at home in Persia, Afghanistan, and India. But he does not confine his literary attentions to the more strictly Eastern countries; on the contrary, one of his most thrilling stories tells of the experiences of the fortunate three among Papuan wreckers, and another relates the escape of an exile from Siberia.

Undoubtedly Mr. Mansford has the gift of the story-teller, and besides, he uniformly writes like a scholar. The illustrations of the book, though small and unpretentious, are admirably executed, and enhance the piquancy—though that was hardly needed—of the letterpress.

The Spectator, 1 December 1894

"ARE you awake, sahibs?" questioned Hassan, our guide, as he eagerly roused us from sleep one night. "The Hunted Tribe of Three Hundred Peaks is about its deadly work! Listen!"

"Listen!"

We sat up and leant forward as he spoke, straining our ears to catch the slightest sound. Across the plain which stretched before us came at intervals a faint cry, which sounded like the hoot of a night bird.

"That is their strange signal," continued the Arab.

We rose, and, going to the door of the tent, scanned the wide plain, but could see no human being crossing it.

"You are mistaken this time, Hassan," said Denviers. "What you heard was an owl hooting."

"The sahib it is who misjudges," answered the Arab, calmly. "I have heard the warning note of the tribe before."

"It seems to come from the direction of Ayuthia," I interposed, pointing to where the faint outlines of the spires of its pagodas rose like shadows under the starlit sky.

"It comes from beyond Ayuthia," responded Hassan, whose keen sense of hearing was so remarkable; "and is as far away as the strange city built on the banks round a sunken ship, which we saw as we floated down the Meinam. Hist! I hear the signal again!"

Once more we listened, but that time the cry came to us from a different direction.

"It is only an owl hooting," repeated Denviers, "which has now flown to some other part of the plain and is hidden from us by one of the ruined palaces, which seem to rise up like ghosts in the moonlight. If Hassan means to wake us up every time he hears a bird screech we shall get little enough rest. I'm going to lie down again."

He entered the tent, followed by us, and stretching himself wearily was asleep a few minutes after this, while Hassan and I sat conversing together, for the strange, bird-like cry prevented me from following Denviers' example.

"Coot! Coot!" came the signal again, and in spite of my companion's opinion I felt forced to agree with the Arab that there was something more than a bird hooting, for at times I plainly heard an answering cry.

After our adventure in the northern part of Burmah we had travelled south into the heart of Siam, where we parted with our elephant, and passed down the Meinam in one of the barges scooped out of a tree trunk, such as are commonly used to navigate this river. Disembarking at Ayuthia we had visited the ruins of the ancient city, and afterwards continued on our way towards the mouth of the river. While examining the colossal images which lie amid the other relics of the city's past greatness, Hassan had told us a weird story, to which, however, at that time we paid but scant attention.

On the night when our Arab guide had roused us so suddenly, our tent was pitched at some distance from the bank of the river, where a fantastic natural bridge of jagged white limestone spanned the seething waters of the tumbling rapids below, and united the two parts of the great plain. Sitting close to the entrance of the tent with Hassan, I could see far away to the west the tops of the great range of the Three Hundred Peaks beyond the plain. Recollecting that Hassan had mentioned them in his story, I was just on the point of asking him to repeat it when I heard the strange cry once more. A moment after the Arab seized me by the arm and pointed towards the plain before us.

I looked in the direction which Hassan indicated, and my eyes rested on the dismantled wall of a ruined palace. I observed nothing further for a few minutes, then a dusky form seemed to be hiding in the shadow of the wall.

"Coot!" came the signal again, striking upon the air softly as if the one who uttered it feared to be discovered. The cry had apparently been uttered by someone beyond the river bank, for the man lurking in the shadow of the ruin stepped boldly out from it into the moonlit plain. He stood there silent for a moment, then dropped into the high grass, above which we saw him raise his head and cautiously return the signal.

"What do you think he is doing there, Hassan?" I asked the Arab, in a whisper, as I saw his hand wander to the hilt of his sword.

"The hill-men have seen our tent while out on one of their expeditions," he responded, softly. "I think they are going to attempt to take us by surprise, but by the aid of the Prophet we will outwit them."

I felt no particular inclination to place much trust in Mahomet's help, as the danger which confronted us dawned fully upon my mind, so instead I moved quickly over to Denviers, and awoke him.

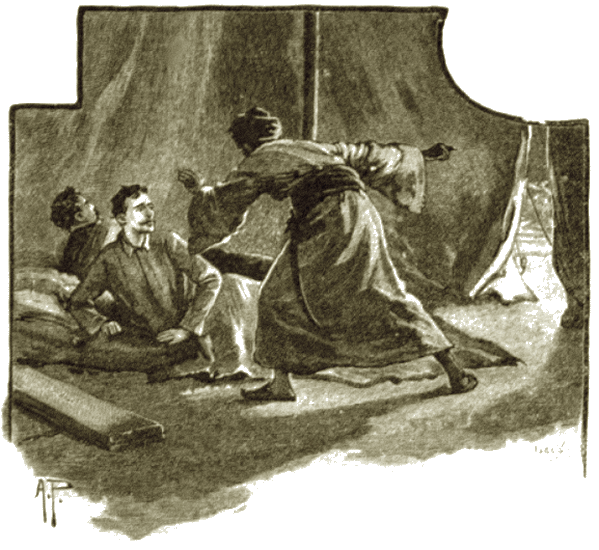

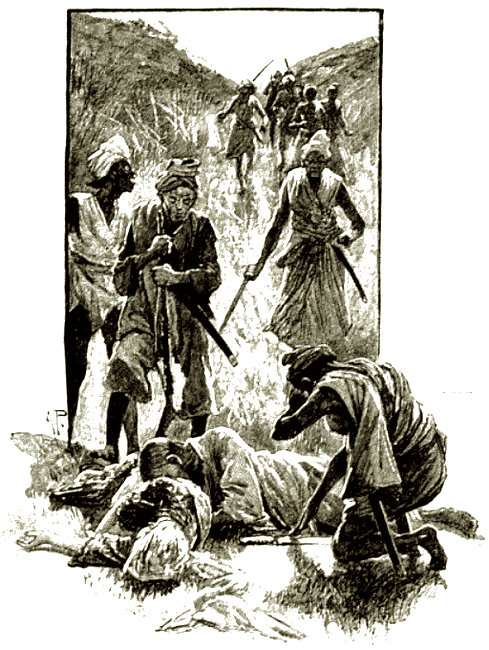

"Is it the owl again?" he asked, as I motioned to him to look through the opening of the tent. Immediately he did so, and saw the swarthy face of a turbaned hill-man raised above the rank grass, as its owner made slowly but steadily towards our tent, worming along like a snake, and leaving a thin line of beaten- down herbage to show where his body had passed. Denviers drew from his belt one of the pistols thrust there, for we had taken the precaution at Rangoon to get a couple each, since our own were lost in our adventure off Ceylon. I quietly imitated his example, and, drawing well away from the entrance of the tent, so that our watchfulness might not be observed, we waited for the hill-man to approach. Halfway between the ruined palace wall and our tent he stopped, and then I felt Hassan's hand upon my arm again as, with the other, he pointed towards the river bank.

The swarthy face of a turbaned hill-man.

We saw the grass moving there, and through it came a second hill-man, who gradually drew near to the first. On reaching him the second comer also became motionless, while we next saw four other trails of beaten-down grass, marking the advance of further foes. How many more were coming on behind we could only surmise, as we watched the six hill-men who headed them get into a line one before the other, and then advance, keeping about five yards apart as they came on. From the position in which our tent was pitched it was impossible for an attack to be made upon us in the rear, and this circumstance fortunately allowed of undivided attention to the movements of the hill-men whom we saw creeping silently forward.

"Wait till the first one of them gets to the opening of our tent," whispered Denviers to me; "and while I deal with him shoot down the second. Keep cool and take a steady aim as he rises from the grass, and whatever you do, don't miss him."

I held my pistol ready as we waited for them to come on, and each second measured with our eyes the distance which still separated us. Twenty yards from the tent the foremost of the hill-men took the kris or bent poniard with which he was armed from between his teeth, and held it aloft in his right hand as he came warily crawling on a foot at a time followed by the others, each with his weapon raised as though already about to plunge it into our throats. It was not a very cheering spectacle, but we held our weapons ready and watched their advance through the grass, determined to thrust them back.

I felt my breath come fast as the first hill-man stopped when within half-a-dozen yards of the tent and listened carefully. I could have easily shot him down as he half rose to his feet, and his fierce eyes glittered in his swarthy face. Almost mechanically I noticed the loose shirt and trousers which he wore, and saw the white turban lighting up his bronzed features as he crept right up to our tent and thrust his head in, confident that those within it were asleep. The next instant he was down, with Denviers' hand on his throat and a pistol thrust into his astonished face, as my companion exclaimed:—

"Drop your weapon or I'll shoot you!"

The hill-man glared like a tiger for a moment, then he saw the advantage of following Denviers' suggestion. He sullenly flung his poniard down, gasping for breath, just as I covered the second of our enemies with my pistol and fired. The hill-man raised his arms convulsively in the air, gave a wild cry, and fell forward upon his face, dead!

He sullenly flung his poniard down.

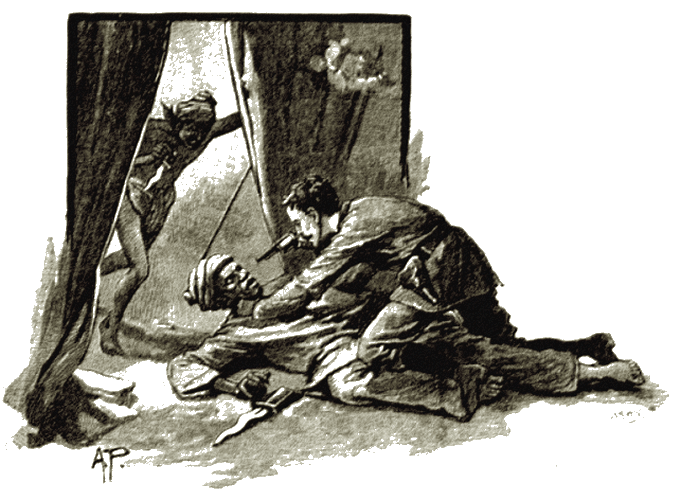

The third of those attacking us dashed forward, undaunted at the fate of the one he saw shot down, only to be flung headlong on the grass the next instant before the tent, with Hassan kneeling on his chest and the point of the Arab's sword at his throat. The rest of the enemy did not wait to continue the combat, but rose from the grass and dispersed precipitately over the plain, making for the limestone bridge across the river.

I rushed forward to Hassan's assistance, and bound the captive's arms, while the Arab held him down as I knotted tightly the sash I had taken from my waist.

Then I made for the tent, to find that Denviers had already secured the first prisoner by lashing about him a stout piece of tent rope. My companion forced his captive from the tent into the open plain, where we held a whispered conversation as to whether the two prisoners should live or die. The safer plan was undoubtedly to shoot them, for we both agreed that at any moment our own position might become a critical one if the rest of the horde made another attempt upon us, as we fully expected would be done.

However, we finally decided to spare their lives, for a time at all events, and while Hassan and Denviers led the captives across the plain, I brought from the tent part of a long coil of rope which we had and followed them. As soon as we neared the river bank we selected two suitable trees from a clump growing there and lashed the prisoners securely to them, threatening instant death if they attempted to signal their whereabouts to any of the hill-men who might be lurking about.

"Get our rifles and ammunition, Hassan," said Denviers to the Arab. Then turning to me, he continued: "We shall have some tough fighting I expect when those niggers return, but we are able to hold our own better out of the tent than in it."

Hassan brought our weapons, saying as he handed them to us:—

"The sahibs are wise to prepare for another attack, since the enemy must return this way. They have not gone off towards the far mountain peaks, but crossed yonder limestone bridge instead."

"What do you understand from that movement?" Denviers asked Hassan.

"The sound which we heard at first came from the strange city of which I spoke," he replied. "Some of the fierce hill-men have made a night attack upon it, and will soon return this way. Those we have beaten off have gone to meet them and to speak of the failure to surprise us. What they are doing in the city round the sunken ship will shortly be apparent. The whole band is a terrible scourge to the cities of the Meinam, for, by Allah, as I told the sahibs at Ayuthia, the Hunted Tribe has a weird history indeed."

Trailing our rifles, we walked through the rank grass, then resting upon a fallen column, where the shadow of the ruined palace wall concealed us from the view of the enemy if they crossed the bridge, we listened to Hassan's story. At the same time we kept a careful watch upon the jagged limestone spanning the river, ready at a moment's notice to renew the struggle, and it was well for us that we did so.

"IT is A strange, wild story which the sahibs shall again hear of the Hunted Tribe and of its leader," began Hassan, as he rested at our feet with his sword gripped in his hand ready to wield it in our service at any moment; "and thus ye will know why the band is out to-night on its fell errand. Years ago, before the Burmese had overrun Siam, and while Ayuthia was its capital, so famous for its pagodas and palaces, Yu Chan became head of the bonzes or priests of the royal monastery.

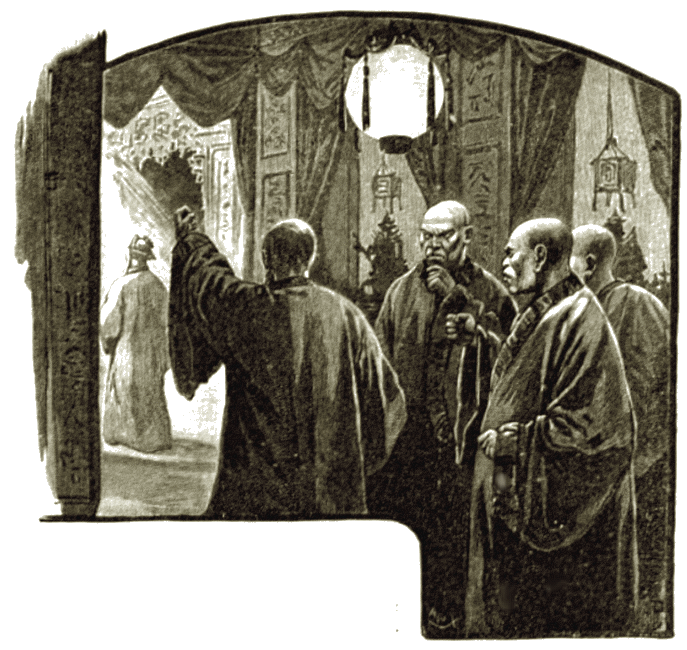

"Who the great bonze was by birth none knew, although it was whispered through the kingdom that he sprang from a certain illustrious family which urged his claim to the position to which the ruler reluctantly appointed him. The subject bonzes looked darkly upon him, for he was but young, while many of them were bowed with age and aspired to hold the high office to which Yu Chan had been appointed. Oft they drew together in the gloomy cloisters, and when he swept past in silence, raised their hands threateningly at his disappearing form, though before his lofty, stern-set face they bowed in seeming humility as they kissed the hem of his magnificent robe.

They raised their hands threateningly at his disappearing form.

"Among these bonzes was one who especially resented Yu Chan's rule over him, for he was more learned in the subtile crafts of the East than the rest, and the potency of his spells was known and feared throughout Siam. An unbending ascetic, indeed, was the grey-bearded Klan Hua, and the ruler of the country had already promised to him that he should become the head of the bonzes whenever the office was vacated. So much was this ruler influenced by Klan Hua that he built a covered way from his palace by which he might pass at night into the bonze's rude cell to hear the interpretation of his dreams, or learn the coming events of his destiny. Yet, in spite of all this, when the chief bonze died, the ruler of Siam, after much hesitation, gave the coveted office to Yu Chan. Judge, then, of the fierce hatred which this roused in Klan Hua's breast, and ye will understand the reason of the plot which he formed against the one who held the position he so much desired."

"Never mind about the quarrels of these estimable bonzes, Hassan," interrupted Denviers. "Go on and tell us of these hill- men, or you won't get that yarn finished before they return, in which case we may never have the chance to hear the end of it."

"The sahib is always impatient," answered the Arab gravely; then he continued, quite heedless of Denviers' suggestion: "On the nights when the ruler went not to Klan Hua's cell, the latter gathered there several of the other bonzes, and they sat darkly plotting till morning came. Then they crept stealthily back to their own cells, to shift their eyes nervously each time that the stern glance of Yu Chan fell upon them, as he seemed to read there their guilty secret.

"They planned to poison him, but he left the tampered food untasted. Then they drew lots to assassinate him as he slept, but the one whose tablet was marked with a poniard was found lifeless the next day, with his weapon still clutched in his stiffened fingers, and none knew how he died. That day the eyes of Yu Chan grew sterner set than ever, as he gazed searchingly into the face of each bonze as they passed in a long procession before him, while the conspirators grew livid with fear and baffled rage at the cold smile with which he seemed to mock at the failure of their schemes. Then they made one last effort a few days after, and ye shall hear how it ended.

"The stately Meinam, which glitters before us under the midnight sky, yearly overflows and renders the earth about it productive. Far as the history of Siam is recorded in the traditions of the race, it has been the custom to perform a strange ceremony, intended to impress the common people with awe for the ruler. Even now the King of Siam, he who sends the silver tree to China in token of subjection, still adheres to it, and on the day when the waters of the Meinam have reached their highest point he sends a royal barge down the swollen waters manned by a hundred bonzes, who command the turbid stream to rise no higher. So then it happened that the rise of the river took place, and Klan Hua, who was learned in such things, counted to the hour when the barge should be launched, even as he had done for many years. When the ruler visited him one eventful night he declared that the turbid waters would be at their full on the morrow, and so the command to them to cease rising could then safely be given.

"Accordingly the royal barge was launched, amid the cries of the people, whereupon the ruler soon entered it and, fanned by a female slave, leant back upon the sumptuous cushions under a canopy of crimson silk, while by his side was the chief bonze—Yu Chan. Near the ruler was the grey-bearded Klan Hua, with an evil smile upon his face as he saw his rival resting on the cushions in the place which he had hoped so long to fill.

"Out into the middle of the swollen river the royal barge went; then half way between bank and bank the rhythmic music of the oars as they dipped together into the water ceased, and the rowers rested. From his seat Yu Chan arose, and uttered in the priestly tongue the words which laid a spell upon the stream and bade it cease to rise. Scarcely had he done so and sunk back again upon the cushions when Klan Hua threw himself at the monarch's feet and petitioned to utter a few words to him. The ruler raised the bonze, and bade him speak. Holding one hand aloft, the plotting Klan Hua pointed with the other towards the astonished Yu Chan, as he fiercely cried:—

"'Thou false-tongued traitor, thou hast insulted thy monarch to his face!'

"The ruler bent forward from his cushions and looked in surprise from the accuser to the accused.

"'Speak!' he cried to Klan Hua; 'make good thy unseemly charge, or, old as thou art, thy head shall roll from thy shoulders!'

"'Great Ruler of Siam and Lord of the White Elephant,' exclaimed the accuser, giving the monarch his strange but august title, 'I declare to thee that the chief bonze has doomed the country to destruction. Taking advantage of the language in which the exorcism is pronounced, he has done what never the greatest prince under thee would dare to do. This man, the head of our order, has spoken words which will make the people scorn thee and this ceremony, if his command comes to pass. Yu Chan, the traitor, has bidden the waters to rise.'

"The monarch crimsoned with anger, as he turned to Yu Chan, who had already regained his composure, and sat with crossed arms, smiling scornfully at his accuser, and then asked:—

"'Hast thou so misused thy power? Speak!'

"'How can'st thou doubt me, knowing my great descent?' cried Yu Chan, bitterly. 'Even at thy bidding I will not answer a question which casts so much shame upon me.'

"'Thou can'st not deny this charge!' exclaimed the infuriated monarch.

"'Not so,' replied the chief bonze, 'I will not! If thou carest to believe the slanderous words which Klan Hua has uttered, and such that not one in this barge will dare to repeat, so be it!'

"Yu Chan withdrew from his seat at the monarch's side, and taking his rival's place pointed to the one he had himself vacated.

"'There rest thyself, and be at last content,' he said, scornfully: 'thou false bonze, whisper thence more of thy malicious words into the ears of the great ruler of Siam!'

"The monarch was disconcerted for a moment, then motioning one of the other bonzes forward, he exclaimed:—

"'Yu Chan declares that no one in this barge will support his accuser's words. Thou who wert near, tell me, what am I to believe?'

"'Alas!' answered the bonze, with simulated grief, 'Klan Hua spoke truly, great monarch; thy trust in Yu Chan has been sorely abused.'

"One after another the bonzes near came before the monarch and gave the same testimony, for the crafty Klan Hua had so placed the plotters for the furtherance of their subtle scheme. The ruler gazed angrily at Yu Chan, then summoning his rival to his side, bade him rest there.

"'Henceforth thou art chief bonze,' he said: then added threateningly to the fallen one: 'Thou shalt be exiled from this hour, and if the waters rise to-morrow, as thou hast bidden them, I will have thee hunted down, hide where thou mayest, and thy head shall fall.'

"The barge reached the shore, and the people drew back amazed to see the monarch pass on, attended closely by Klan Hua, while he who was as they thought chief bonze flung off his great robe of purple-embroidered silk, and idly watched the bonzes disembark, then moved slowly away across the great plain.

"Two days afterwards Klan Hua was found dead in his cell, covered with the robes of his newly-acquired office, and the ruler of Siam had dispatched a body of soldiers to hunt down Yu Chan and to take him alive or dead to Ayuthia. The Meinam had risen still higher the day after the ceremony, not, as the startled monarch thought, because of the deposed one's power, but owing to Klan Hua's deception in regard to the real time when he knew the water would reach its limit.

Klan Hua was found dead in his cell.

"Then began the strange events which made the name of Yu Chan so memorable. For some years a band of marauders had taken possession of the far range known as the Three Hundred Peaks, but hitherto their raids in Burmah and Siam had attracted scant attention, while in Ayuthia few knew of their existence. To them the bonze went, and when the half-savage troops sent in search of him were encamped on the edge of the plain the mountaineers unexpectedly swooped down upon them. The remnant which escaped hastened back to the monarch with strange stories of the prowess of the enemy, and especially of Yu Chan, the exile, whom they averred led on the foe to victory. The ruler of Siam, deeply chagrined at their non-success, ordered the vanquished ones to be decapitated for their failure to bring back the bonze or his lifeless body.

"A second expedition was sent against them, but the mountaineers held their fastnesses so well that, in despair of conquering them, the few who survived their second onslaught slew themselves rather than return to Ayuthia to suffer a like fate to that which the monarch had awarded the others. Maddened at these repeated defeats, the ruler himself headed a large army and invested the passes, cutting off the supplies of the mountaineers, in the hope of starving them into subjection. So deeply was he roused against Yu Chan that he offered to pardon the rebels on condition that they betrayed their leader.

"They scornfully rejected such terms, and withdrew to the heart of the mountains to endure all the horrors of famine with a courage which was heroic. At times the brave band made desperate efforts to break through the wall of men which girded them about, and each onset, in which they were beaten back, inspired them to try yet again.

"The Malay who told me their story declared they were reduced to such straits at last that for one dreadful month they lived upon their dead. Never once did they waver from their allegiance to Yu Chan, whose stern-set face inspired them to resist to the last, for well he knew that the monarch's promise could not be trusted, and that surrender for them meant death. Often would they be repulsed at sunset in an attempt to break through the cordon which held them, and yet before nightfall, at the entrance of some precipitous pass, far remote from that spot, swift and sudden the gaunt and haggard band appeared, led on by Yu Chan, sword in hand, as he hewed down those who dared to face him.

"Just when they were most oppressed relief came to the band of a quite unexpected kind, for the Burmese on the border overran Siam, and the soldiers were withdrawn to meet the new enemy. So, for a time, the band was left unmolested; but still none, save their leader, ventured to leave their wild haunts. Before he had been appointed chief of the bonzes who brought about his exile, Yu Chan had been the lover of a maiden of Ayuthia, but the high office which had been bestowed on him kept them apart. No sooner had the robes which he wore as a bonze been exchanged for those of a mountaineer than Yu Chan determined to see this maiden again. On the departure of their enemies he prepared to visit Ayuthia, although strongly counselled not to do so by his devoted band. He was, however, obdurate, and set forth on his perilous enterprise alone.

"Yu Chan crossed the great plain of Siam, and then, resting in a thatched hut upon the bank of the Meinam, dispatched a Malay, who chanced to dwell there, with a message to his beloved to visit him, for he thought it useless to attempt to enter Ayuthia if he wished to live. At nightfall the Malay returned from the island in the middle of the bend of the Meinam, whereon ye know the city is built. He thrust a tablet into Yu Chan's hand, whereon was a desire that the latter would wait the maiden's coming at a part of the bank where often the boat of the lovers had touched at before. Soon the exile beheld the slight craft making for the shore, manned by six rowers muffled in their cloaks, for the night was cold. Happy indeed would it have been for the lovers if the maiden had scanned closely the features of those who ferried her across the river, for the treacherous Malay had recognised Yu Chan, and six of the monarch's soldiers were the supposed boatmen, hurriedly gathered to take the exile or to slay him.

"The maiden stepped from the boat, and, with a glad cry, flung her arms about Yu Chan, who had passed down the narrow path to meet her. Together they climbed up the steep way that led to the plain above the high bank, followed by the muffled soldiers, who lurked cautiously in the shadows of the limestone, through which wound the toilsome path. Once, as they passed along, a slight sound behind them arrested the footsteps of the lovers, and Yu Chan turned and glanced back searchingly, then on they went again. For an hour or more they wandered together over the plain, then, with many a sigh, turned to descend the path once more. Again they heard a sound, and that time on looking round quickly Yu Chan saw the boatmen, whom he had thought awaited the maiden's return by the river brink, stealing closely after him, their faces shrouded in their black cloaks.

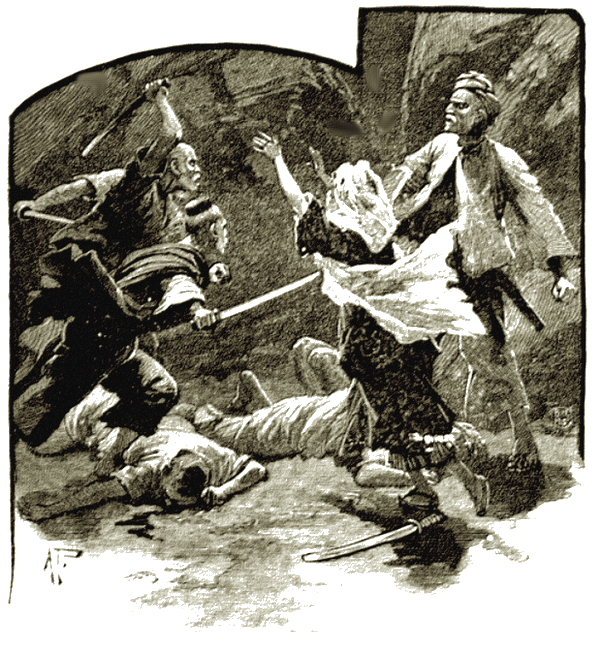

"At once his suspicions were aroused, and hastily unsheathing his sword he confronted them just as they flung off their cloaks and the fierce faces of six of the half-savage soldiery of the monarch were revealed to Yu Chan. Slowly the latter retreated till he was a little way down the path with his back to the protecting limestone, then stood at bay to defend the maiden and himself from the advancing foes. Warily they came on, for well they knew the deadly thrusts which he could deal with his keen sword. Yu Chan in fighting at such desperate odds more than once failed to beat down the weapons lunged at him, but though severely wounded he did not flinch from the combat. Three of his assailants lay dead at his feet, when the leader of the monarch's soldiery twisted the sword from Yu Chan's hand, and then the three surviving foes rushed upon the defenceless man. With a cry that pierced the air the maiden flung herself before her lover—to fall dead as her body was thrust through and through by the weapons intended for the heart of Yu Chan!

The maiden flung herself before her lover.

"Like a boarhound the mountain chief leapt upon his nearest assailant, wrenched the sword dripping with the maiden's blood from his hand, and almost cleaved him in half with one resistless stroke. He turned next upon the remaining two, but they fled headlong down the path, Yu Chan following with a fierce cry at their heels. Into the boat they leapt, nor dared to look behind till they were out in mid-stream; then they saw the wounded chief slowly dragging himself back to where the maiden lay lifeless.

"Yu Chan bent despairingly over her as he saw the fatal stains which dyed her garments and reddened some of the fragrant white flowers fallen from her hair, which lay in masses framing her white, still face. Taking up his own sword, he sheathed it; then he raised the maiden gently in his arms, and, covered himself with gaping wounds, he set out to cross the great plain to the Three Hundred Peaks, where his followers awaited his return. On he struggled for two weary days with his lifeless burden; then at last he reached the end of his journey, and as the mountaineers gathered hastily about him and shuddered to see the ghastly face of their chief, Yu Chan tottered and fell dead in their midst!

"Round the two lifeless forms the hunted tribe gathered, and, looking upon them, knew that they had been slain by their remorseless foes. One by one the mountaineers pressed forward, and amid the deathly silence of the others, each in turn touched the sword of their slain chief and sternly swore the blood- revenge. Fierce, indeed, as are such outbreaks in many eastern lands, that day marked the beginning of dark deeds of requitement that have made all others as nothing in comparison to them. The Burmese came down upon Siam and swept over fair Ayuthia, leaving nothing but the ruins of the city; yet, even in that national calamity, the fierce instinct of murder so fatally roused in the breasts of the mountaineers never paused nor seemed dulled. While the magnificent city lay despoiled, the once hunted tribe fell upon the others about the Meinam, and long after peace reigned throughout the country, still their deeds of pillage and massacre went on, as they do even to this day, so remote from the one when their leader was slain.

They swore the blood-revenge..

"For months the tribe will be unheard of, and lulled by a false sense of security the inhabitants of one of these cities will make preparations for one of their recurring festivals. Even in the midst of such the strange cry of the hunted tribe will be heard, and the coming day will reveal to the awestruck people the evidence of a night attack, in which men and women have been slain or carried off suddenly to the Three Hundred Peaks."

"The present descendants of the avengers of Yu Chan's death are a cowardly lot, at all events," commented Denviers, as the Arab finished his recital: "they attacked us without reason, and have consequently got their deserts. If they come upon us again—"

"Hist, sahib," Hassan whispered cautiously, as he pointed with his sword towards the fantastic bridge of limestone; "the hunted tribe is returning from its raid, see!"

We looked in the direction in which he motioned us, and saw that the mountaineers bore a captive in their midst! Immediately one of the prisoners lashed to the trees gave a warning cry, regardless of the threats which Denviers had uttered. Hassan sprang to his feet, and stood by my side as we raised our rifles, still hidden as we were in the shadow of the ruined palace wall.

"HASSAN," whispered my companion to the Arab; "go over to the prisoners there, and if they cry out again shoot them. I don't think that first cry has been heard by the others." As he spoke Denviers thrust a pistol into Hassan's hand and motioned to him to move through the grass towards them. We watched our guide as he neared them and raised the pistol threateningly—a silent admonition which they understood, and became quiet accordingly.

From our position in the shadow of the ruined palace wall we saw a number of the hunted tribe slowly wind over the bridge with their captive, and noticed that in addition they had plenty of plunder with them. Noiselessly they moved towards our tent, and completely surrounded it, only to find it empty. They were evidently at a loss what to do, when one of their number stumbled over the dead mountaineer whom I had shot down as he joined in the attack upon us. A fierce exclamation quickly caused the rest to gather about him, and for some minutes they held a brief consultation. We judged from their subsequent actions that they considered we had made good our escape from the plain, for they made no further search for us, but apparently determined to avenge their comrade's death by slaying their captive. While the rest of the band moved away over the plain, two of their number returned towards the limestone bridge spanning the river. Guessing their fell purpose, Denviers and I crept through the tall grass, and under cover of the trees by the bank moved cautiously towards them.

From tree to tree we advanced with our rifles in our hands, then just when within twenty yards of them we stopped aghast at the movements of the two mountaineers, who were forcing their struggling captive slowly towards the edge of the jagged limestone bridge!

We looked down at the angry waters of the rapid, swirling twenty feet below in the deep bed of the river, which was slowly rising each day, for the time of its inundation was near at hand. For a moment I saw a woman's horror-stricken face in the moonlight and heard her agonizing cry, then the sharp crack of Denviers' rifle rang out, and one of her assailants relaxed his grasp. Before Denviers could take a shot at the second mountaineer, he seized the captive woman and deliberately thrust her over the rocky bridge!

Over the rocky bridge!

"Quick! To the river!" exclaimed Denviers, as we heard the sound of her body striking the waters below. Down the steep bank we scrambled, steadying ourselves by grasping the lithe and dwarfed trees which grew in its rocky crevices. For one brief moment we scanned the seething torrent, and then, right in its midst, we saw the face and floating hair of the woman as she was tossed to and fro in the rapid, while she vainly tried to cling to the huge boulders rising high in the stream through which her fragile form was hurried.

"Jump into the boat and wait for me to be carried down to you!" cried Denviers, and before I fully realized what he was about to do, he flung his rifle down and plunged headlong into the foaming waters. I saw him battling against the fierce current with all his might, for the rocks in mid-stream prevented the woman from being floated down to us and threatened to beat out her life, as she was borne violently against them. I ran madly towards where our boat had been drawn up, and pushing it into the river strained my eyes eagerly in the wild hope of seeing Denviers alive when his body should be floated down towards me.

I pulled hard against the stream and managed to keep the rude craft from being carried away with the current. A few minutes afterwards I saw that my companion had succeeded in dragging the woman from the grinding channels between the rocks, and was being swept on to where I anxiously awaited him with his burden. The water dashed violently against the boat as I put it across the middle of the rushing stream, then dropped the oars as he was flung towards me. I stretched out my arms over the side in order to relieve him of his burden, and, although he was exhausted, Denviers made one last effort and thrust the woman towards me. I dragged her into the boat just as her rescuer sank back. With a quick but steady grip I caught my companion and hauled him in too, and before long had the happiness to see both become conscious once more.

Leaving the boat to float down the stream, I merely steered it clear of the rocky sides of the river channel, then, seeing some distance ahead a favourable place to land, drew in to the shore with a few swift strokes from the oars. Denviers remained with the woman he had rescued, while I climbed the steep bank again and found that the mountaineers had, fortunately, not returned, although we had fully expected the report of Denviers' rifle to cause them to do so. I thereupon signalled to my companion below that all was safe, and he toiled up to the plain supporting the woman, who was a Laos, judging from her garments and slight, graceful form.

Spreading for her a couch of skins, we left her reclining wearily in the tent, to which Denviers conducted her, then hastened towards Hassan, whom we found still keeping guard over our two captives. The Arab, when he heard of the hazardous venture which Denviers had made, stoutly urged us to put our prisoners to death, as a warning to the hunted tribe that their misdeeds could not always be carried on with impunity. For reply Denviers quietly took the pistol from the Arab's hand, and then we returned towards the tent, outside which we rested till day dawned.

The woman within the tent then arose and came towards us, thanking Denviers profusely for saving her from such a death as had confronted her. She told us that her betrothal to a neighbouring prince had taken place only a few days before, but although every precaution had been taken to keep the affair secret, the news was conveyed to the hunted tribe by some one of the many supporters of the mountaineers. As she was a woman of high rank, this seemed to them a suitable opportunity to strike further terror into the hearts of the people inhabiting the cities about the Meinam. Their plans had been thoroughly successful, for they had despoiled several of the richest citizens, slaying those who opposed them, then snatching the woman up, began to carry her off to live among their tribeswomen, and to become one of them, when we fortunately saved her from that fate. We promised to conduct her to the city whence she had been stolen, which we eventually did, but before setting out for that purpose we visited our prisoners again.

"Hassan," said Denviers, "release the men from the trees."

The Arab most reluctantly did so, stoutly maintaining that after Mahomet had helped us so strangely and successfully, we would be wiser either to shoot them or leave them bound till someone discovered and dealt with our prisoners as they deserved.

The ropes were accordingly unbound which fastened them to the trees; then Denviers pointed to the distant range of the Three Hundred Peaks and bade them begone. The two prisoners set forward at a run, being not a little surprised at our clemency. When they had at last disappeared in the distance, we moved towards the city beyond Ayuthia to restore the princess to her people, who had, by our means, been snatched from the power of the hunted tribe.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.