RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

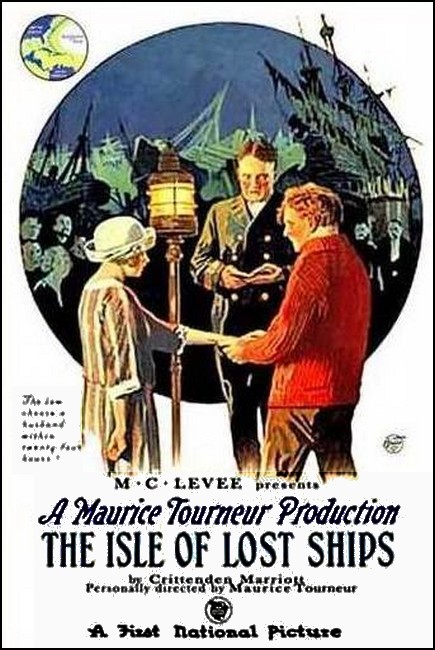

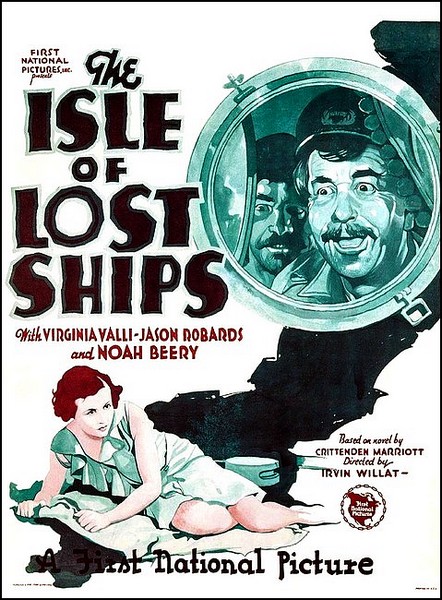

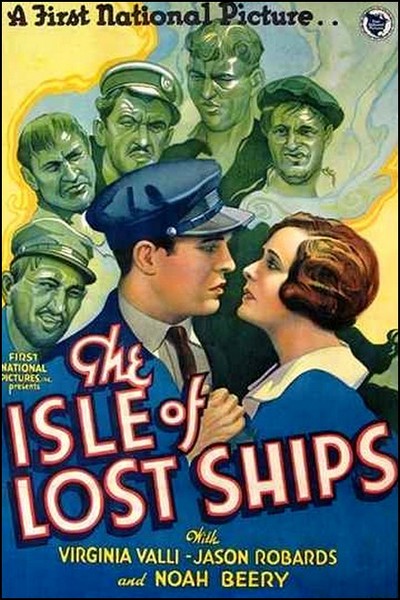

The Scrap Book, January 1909,

with the first part of "The Isle of Dead Ships"

"The Isle of Dead Ships,"

J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia & London, 1909

Title Page of "The Isle of Dead Ships,"

J.B. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia & London, 1909

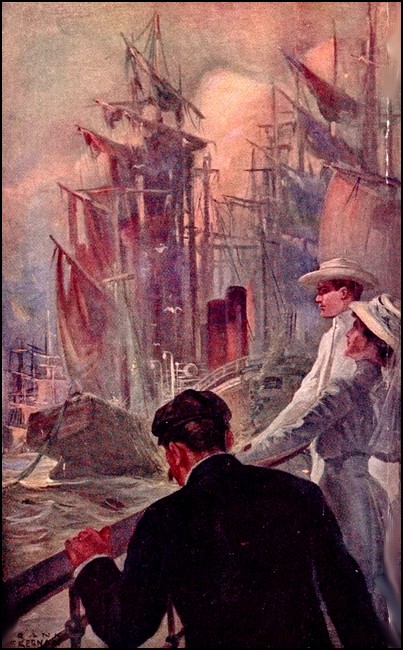

Frontispiece

"No, he murmured sadly, "it is not land. It us wreckage."

THERE is a floating island in the sea where no explorer has set foot, or, setting foot, has returned to tell of what he saw. Lying at our very doors, in the direct path of every steamer from the Gulf of Mexico to Europe, it is less known than is the frozen pole. Encyclopedias pass over it lightly; atlases dismiss it with but a slight mention; maps do not attempt to portray its ever-shifting outlines; even the Sunday newspapers, so keen to grasp everything of interest, ignore it.

But on the decks of great ships in the long watches of the night, when the trade-wind snores through the rigging and the waves purr about the bows, the sailor tells strange tales of the spot where ruined ships, raked derelict from all the square miles of ocean, form a great island, ever changing, ever wasting, yet ever lasting; where, in the ballroom of the Atlantic, draped round with encircling weed, they drone away their lives, balancing slowly in a mighty tour-billion to the rhythm of the Gulf Stream.

Fanciful? Sailors' tales? Stories fit only for the marines! Perhaps! Yet be not too sure! Jack Tar, slow of speech, fearful of ridicule, knows more of the sea than he will tell to the newspapers. Perhaps more than one has drifted to the isle of dead ships, and escaped only to be disbelieved in the maelstroms that await him in all the seaports of the world.

Facts are facts, none the less because passed on only by word of mouth, and this tale, based on matter gleaned beneath the tropic stars, may be truer than men are wont to think. Remember Longfellow's words:

"Wouldst thou," thus the steersman answered,

"Learn the secret of the sea?

Only those that brave its dangers

Comprehend its mystery."

AS the prisoner and Officer Jackson, handcuffed together, came up the gang-plank, Renfrew, the attorney, standing on the promenade deck above, turned from his contemplation of the city of San Juan as it lay green and white in the afternoon sun, and bent forward.

"By George," he cried, exultingly, "that's Frank Howard! He's caught! Caught here, of all places in the world!"

With hands tight gripped on the rail he watched the two men until they disappeared below; then, eager to share his discovery of the ending of a quest that had extended over two continents, he turned and hurried along the deck to where two ladies stood leaning against the taffrail.

"Yes, my dear," the elder was saying, "Porto Rico is pretty enough for any one. It looked pretty when I came, and it looks prettier as I go. But when you say it's pretty, you exhaust its excellences. I, for one, shall he glad to see the last of it. And, considering the errand that takes you home, I imagine that you don't regret leaving, either."

"The errand! I don't understand, Mrs. Renfrew."

"Why! Your—but here comes Philip, evidently with something on his mind. Do listen to him patiently, if you can, my dear. He hasn't had a jury at his mercy for a month. Unless somebody lets him talk, I'm afraid his bottled-up eloquence will strike in and prove fatal. Well, Philip!"

Mr. Renfrew was close at hand.

"Miss Fairfax! Maria!" he cried. "Who do you think is on board, a prisoner? Frank Howard! I just saw him brought over the gang-plank. He escaped two months ago, and the police have been looking for him ever since. They must have just caught him, or I should have heard of it. Who in the world can I ask?"

He gazed around questioningly.

"Now, Philip, wait a moment. Who is Frank Howard? and what has the poor man done?"

Mr. Renfrew snorted.

"The poor man, Maria," he retorted, "is one of the biggest scoundrels unhung. As state's attorney it was my duty to prosecute him, and I may say that I have seldom taken more pleasure in any task. I have spoken to you of the case often enough, Maria, for you to know something about it. I should really be glad if you would take some interest in your husband's affairs."

Mrs. Renfrew clapped her hands.

"Of course! I remember now," she said, soothingly. "It was only his name I forgot. Mr. Howard is that swindler who robbed so many poor people, isn't he, Philip?"

"Nothing of the sort, madam," thundered the lawyer. "Frank Howard was an officer of the United States Navy. While stationed at this very island of Porto Rico he secretly married an ignorant but very beautiful girl, and then deserted her. She followed him to New York, and wrote him a letter telling him where she was. He went to her address and murdered her—strangled her with his own hands. He was caught red-handed, convicted, and would have been put to death before now if he hadn't escaped.

"I am telling this for your benefit, Miss Fairfax. There is no use in talking to Mrs. Renfrew; details of my affairs go in one of her ears and out the other."

"That may not be as uncommon as you think, Mr. Renfrew," consoled the girl, laughing. "But, as it happens, I am especially interested in the Howard case. I am very well acquainted with one of the officers who was on his ship when he met the girl."

Mrs. Renfrew clapped her hands.

"Oh! of course," she bubbled. "Of course! I remember all about it now. It was Mr. Loving, of course! I had forgotten that he was on the same ship. Philip, you didn't know that Miss Fairfax was going to marry Lieutenant Loving, did you?"

Mr. Renfrew turned his eye-glasses on the girl, who flushed with mingled anger and amusement.

"Are you a seventh daughter of a seventh daughter, Mrs. Renfrew," she inquired, "that you can read the future? I assure you that I have had no advance information on the matter. Mr. Loving hasn't even asked me yet. But, of course, if you know—"

"Good gracious! Isn't it true? Why, I got a paper from New York to-day that spoke of it as all settled. The paper is in my state-room now. If you'd like to see it, we'll go down. Philip, find out all you can about Mr. Howard, and tell us just as soon as you can."

Mr. Renfrew nodded.

"I'll go and ask the captain," he promised, as the two ladies turned away.

The captain, however, proved not to be communicative. Not only was he too busy with the preparations for departure, but he was nettled because the presence of the convict on board had become known. Convicts are not welcome passengers on ships, like the Queen, whose chief office is to carry presumably timid pleasure passengers, and their presence is always carefully concealed.

"I know nothing at all about it, Mr. Renfrew," he asserted, gruffly. "You had better ask the purser."

The purser was no more pleased at the inquiry than his chief had been, but he hid his vexation better.

"Yes," he admitted, with apparent readiness, "Mr. Howard is on board. He was caught here last week. He was up at a village called Lagonitas—"

"That's where his wife lived—the one he murdered."

"Is it! I didn't know. Well, they caught him. He surrendered quietly—didn't try to fight or run. He hadn't anywhere to run to, you know."

"And where is he confined!"

"Amidships—in one of the second-class cabins. We have plenty vacant this trip. Officer Jackson is with him, where he can keep close watch. You tell your ladies not to be uneasy. He can't possibly get out. Jackson has got a hundred weight of iron, more or less, on him."

"Jackson, is it! I thought I recognized him. One of those bulldog fellows that never lets go. I'm interested in Howard because it was I who conducted the prosecution at his trial."

"Gee! Is that so! It must have been exciting. He confessed, didn't he!"

"Confessed! Not he! Took the stand as brazen as you please, and swore he had never seen the woman before he went to her room that day in response to a letter and found her dead. It was nothing less than barefaced impudence, you know. The proof against him was simply overwhelming."

"He denied having married her, then?"

"He denied everything. Swore it was a case of mistaken identity. I demolished that quickly enough. Dozens of people had seen him up at Lagonitas with the girl. We even sent for the minister who performed the marriage ceremony, but he never arrived—lost at sea on the way to New York. But there was plenty of proof, anyway. The jury found him guilty without leaving their seats."

WHEN Dorothy Fairfax came on deck again the sun was dropping fast toward the horizon. A gusty breeze was blowing and the steamer was pitching slightly in the short, choppy seas that characterize West Indian waters. Movement had become unpleasant to those inclined to seasickness and this, combined with the comparative lightness of the passenger list, caused the deck of the Queen to be nearly deserted.

Dorothy was glad of it. She wanted solitude in order to think in peace, and there was seldom solitude for her when young men—or old men, for that matter—were near. They seemed to gravitate naturally to her side.

Mrs. Renfrew's words, and especially the paragraph in the New York paper, were troubling her. She could see the words now, published under a San Juan date-line:

"Miss Dorothy Fairfax, daughter of the multimillionaire railroader, John Fairfax, will sail next week for New York to order her trousseau for her coming marriage with Lieutenant Loving, U. S. N. Mr. Fairfax, who is financing the railroad here, will follow in about three weeks."

That was all; the whole thing taken for granted! Evidently the writer had supposed that the engagement had been already announced, or he would either have made some inquiry or—supposing that he was determined to publish—would have "spread" himself on the subject. Miss Fairfax had been written up enough to know that her engagement would be worth at least a column to the society editors of the New York papers. Yes, she concluded, the item must have emanated from some chance correspondent who had picked up a stray bit of gossip.

She had known Mr. Loving for two years or more, and had liked him. Three months before, at the close of the Howard trial, she had become convinced that he intended to ask her to marry him, and she had slipped away to join her father in Porto Rico in order to gain time to think before deciding on her answer. And here she was, returning home, no more resolved than when she had left.

It was odd that her ship should also bear Lieutenant Howard, of whom Mr. Loving had been so fond, standing by him all through his trial when everybody else fell away. She had had a glimpse of Mr. Howard once, and vaguely recalled him, wondering what combination of desperate circumstances could have brought a man like him to the commission of such a crime.

The judge, she remembered, in sentencing him to death had declared that no mercy should be shown to one who, with everything to keep him in the straight path, had deliberately gone wrong.

The soft pad of footsteps on the deck roused her from her musings, and she turned to see the purser drawing near.

"Ah! Good evening, Miss Fairfax!" he ventured. "We missed you at tea. Feeling the motion a bit? It is a little rough, ain't it?"

Miss Fairfax did not like the purser, but she found it difficult to snub any one. Therefore she answered the man pleasantly, though not with any especial enthusiasm.

"Why! no, Mr. Sprigg. I don't consider this rough; I'm rather a good sailor, you know. I simply wasn't hungry at tea-time."

Mr. Sprigg came closer.

"By the way, Miss Fairfax," he insinuated. "You know Lieutenant Howard is on board. If you'd like to have a peep at him, just say the word and I'll manage. Oh!" he added, hastily, as a slight frown marred Miss Fairfax's pretty brows, "I know you must be interested in his case. He's a friend of Lieutenant Loving, and I read the notice in the paper to-day, you know."

The look the girl gave him drove the smirk in haste from his face.

"The notice in the paper was entirely without foundation, Mr. Sprigg," she declared, coldly. "As for seeing Mr. Howard, I'm afraid my tastes do not run in that direction. Besides, he probably would not like to be stared at. He was a gentleman once, you know."

She turned impatiently away and looked eastward. Then she uttered an exclamation.

"Why! Whatever's happened to the water?" she cried.

The question was not surprising. In the last hour the sea had changed. From a smiling playfellow, lightly buffeting the ship, it had grown cold and sullen. The sparkles had died from the waves, giving place to a metallic lustre. Long, slow undulations swelled out of the southeast, chasing each other sluggishly up in the wake of the ship.

It did not need a sailor's eye to tell that something was brewing. Miss Fairfax shivered slightly and drew her light wrap closer around her.

"Makes you feel cold, don't it!" asked Mr. Sprigg cheerfully. "Lord bless you, that's nothing to the way you'll feel before it's over. Funny the weather bureau didn't give us any storm warnings before we sailed."

The weather bureau had, but the warnings had been thrown away, unposted, by a sapient native official of San Juan, who considered the efforts of the Americans to foretell the weather to be immoral.

"Will there be any danger!"

"Danger? Naw! Not a bit of it. If you stay below, you won't even know that there's been anything doing. Even if we run into a hurricane, which ain't likely, we'll be just as safe as if we were ashore. The Queen don't need to worry about anything short of an island or a derelict."

"A derelict!"

"Sure. A ship that has been abandoned at sea for some reason or other, but that ain't been broken up or sunk. Derelicts are real terrors, all right."

"Some of 'em float high; they ain't so bad, because you can usually see 'em in time to dodge, and because they ain't likely to be solid enough to do you much damage even if you do run into them. But some of 'em float low—just awash—and they're just—Well, they're mighty bad. They ain't really ships any more; they're solid bulks of wood."

"I suppose they are all destroyed sooner or later?"

The little purser unconsciously struck an attitude. "A good deal later, sometimes," he qualified. "Derelicts have been known to float for three years in the Atlantic, and to travel for thousands of miles. Generally, however, in the North Atlantic, they either break up in a storm within a few months, or else they drift into the Sargasso Sea and stay there till they sink."

"The Sargasso Sea? Where is that? I suppose I used to know when I went to school, but I've forgotten."

Mr. Sprigg waved his hand toward the east and north. "Yonder," he generalized vaguely. "We are on the western edge of it now. See the weed floating in the water there? Farther north and east it gets thicker until it collects into a solid mass that stretches five hundred miles in every direction.

"Nobody knows just what it looks like in the middle, for nobody has ever been there; or, rather, nobody has ever been there and come back to tell about it. Old sailors say that there's thousands of derelicts collected there."

"The Gulf Stream encircles the whole ocean in a mighty whirlpool, you know, and sooner or later everything floating in the North Atlantic is caught in it. They may be carried away up to the North Pole, but they're bound to come south again with the icebergs and back into the main stream, and some day they get into the west-wind drift and are carried down the Canary current, until the north equatorial current catches them, and sweeps them into the sea over yonder."

"For four hundred years and more—ever since Columbus—derelicts must have been gathering there. Millions of them must have sunk, but thousands must have been washed into the center. Once there, they must float for a long time. There are storms there, of course, but they're only wind-storms—there can't be any waves; the weed is too thick."

"I guess there are ships still afloat there that were built hundreds of years ago. Maybe Columbus's lost caravels are there; maybe people are imprisoned there! Gee! but it's fascinating."

Miss Fairfax stared at the little man in amazement. He was the last person she would ever have suspected of imagination or romance; and here he was, with flushed cheeks and sparkling eyes, declaiming away like one inspired. Most men can talk well on some one subject, and this subject was Mr. Sprigg's own. For years he had been reading and talking and thinking about it.

Miss Fairfax rose from her steamer-chair and looked around her, then paused, awestruck. Down in the southeast a mass of black clouds darkened the day as they spread. Puffs of wind ran before them, each carrying sheets of spray torn from the tops of the waves; one stronger than the rest dashed its burden into Miss Fairfax's face with little stinging cuts. The cry of the stewards, "All passengers below!" was not needed to tell her that the deck was rapidly becoming no place for women.

AN hour later the deck had grown dangerous, even for men. The Queen drove diagonally through the waves, rolling far to right and to left; and at each roll a miniature torrent swept aboard her, hammered on her tightly-fastened doors, and passed, cataract-wise, back into the deep. Scarcely could the officers, high on the bridge, clinging to stanchions and shielded by strong sheets of canvas, keep their footing. Overhead hooted the gale.

It grew dark. To the gloom of the storm had been added the blackness of the night. Literally, no man could see his hand before his face; even the white foam that broke upon the decks or against the sides passed invisibly.

Still, the ship drove on, held relentlessly to her course. For it was necessary to pass the western line of the weed-bound sea before turning to the north; and, until this was done, the Queen could not turn tail to the storm.

Toward morning Captain Bostwick struggled to the chart-house and, for the twentieth time, bent over the sheet, figuring and measuring. Then, with careful precision, he punched a dot in the surface and drew a long breath.

"We are all right now," he announced. "We can bear away north with safety. Nothing can harm us, unless—"

He opened the last chart of the Hydrographic Office and noted some lines drawn in red. His brow grew anxious again and he drew his breath.

"Confound that derelict!" he muttered. "Allowing for drift, she should be close to this very spot. If we should strike her—"

The sentence was never finished. With a shivering shock like that of a railroad train in a head-on collision, the Queen stopped dead, hurling the captain violently over the rail to the deck below.

The first officer was clutching the rope of the siren when the crash came. The slight support it afforded before it gave way saved him from following his commander, and at the same time sent a raucous warning through the ship to close the collision bulkheads.

As he clung desperately to the rail, the Queen rose in the air and came down with another crash; then went forward over something that grated and tore at her hull as she passed. But her bows were buried in the waves, while her screw lashed the air madly.

Had not the involuntary warning of the siren sounded, and had it not been obeyed instantly, the Queen would have plunged in that heart-breaking moment to the bottom. As it was, her shrift seemed short.

The force of her impact on the lumber-laden, water-logged derelict had shattered her bows, and only the forward bulkhead, strained, split, gaping in a hundred seams where the rivets had been wrenched loose, kept out the sea. A hurried inspection showed that even that frail protection would probably not long suffice.

"It's only an hour to dawn," gasped the first officer. "If she can last till then—"

She lasted, but dawn showed a desperate state of affairs. The Queen had swung round, until her submerged bow pointed to windward and her high stern, catching the gale, plunged dully northward. The seas, rushing up from the southeast, broke on the shelving deck like rollers on a beach, and sent the salt spume writhing up the planks and into the deck state-rooms.

The engine and all the forward part of the ship were drowned, but the great dining-saloon and the staircase leading to the social hall above were still comparatively dry. In the latter and on the deck just outside of it the passengers were huddled. The captain had disappeared, licked away by the first tongue of sea that had followed the collision.

With the earliest streak of light the first officer decided to take to the boats. Only three remained, and these had already been fitted out with provisions.

As the crew and passengers filed into the first, Officer Jackson, who had several times come on deck, only to wander restlessly below again, once more plunged down into the darkness.

Rapidly yet cautiously he lowered himself down the sloping passageway, clutching at the jambs of empty state-rooms to keep himself from sliding down against the bulkhead, on the other side of which the sea muttered angrily. At last he gained the door he sought, and clung to it while he fitted a key into the lock.

The electric lights had gone out when the engine stopped, and not a thing could be seen in the blackness, but a stir within told that the room was tenanted. Some one was there, staring toward the door.

Jackson lost no time.

"Here you!" he blustered, in a voice into which there crept a quiver in spite of him. "Last call! The ship's sinking and they're taking to the boats. You gotter decide mighty quick if you're going to come. Just gimme your parole and I'll turn you loose to fight for your life."

A voice answered promptly:

"I'll give no parole. I'd a deal sooner drown here than hang on shore. You can do just as you please about releasing me. It's a matter of indifference to me."

The officer tried to protest.

"I don't want your death on my shoulders, Mr. Howard," he muttered. "Don't put me to it."

Howard laughed sardonically.

"What the devil do I care about your shoulders!" he demanded. "Turn me loose, quick, or get out. Your company isn't exhilarating, my good Jackson."

Both men had raised their voices so as to be heard above the boom of the storm. As Howard ceased, there came an impact heavier than before, followed by faint, despairing shrieks.

With an oath, Jackson felt his way to the voice and bent over the berth in which his prisoner was lying. "Curse you!" he snarled. "For two cents I'd take you at your word and let you drown. But I can't. Here!"

The clink of a key and the rattle of metal told that the handcuffs fell away.

"You're loose now," continued the officer. "But, by Heaven, if you try to escape, I'll see that you don't miss the death you say is welcome. Come on."

Howard swung his legs over the edge of the berth.

"That's fair," he said. "Go ahead. I'll follow."

Hastily, Jackson led the way up the slanting passage to the topsy-turvy stairway, and so to the deck. A single glance about him and he turned on the other in fury. "Curse you," he roared, "you've drowned us both with your infernal palavering!"

The decks were deserted; not a human being remained on them. Tossing on the waves, just visible in the glowing light, were two of the ship's boats, crowded with passengers. The nearest was already a hundred yards away, and rapidly increasing its distance. The guard stared at it hungrily.

"There goes our last chance!" he muttered.

Howard eyed the tiny craft dispassionately.

"Oh! I don't know," he said. "If that boat was your best chance, it was a slim one. Never mind, Jackson; take comfort from me. Nobody doomed to hang was ever drowned. I'll send you home to your wife and babies yet—I suppose you have a wife and babies; people like you always do."

"Here! Don't you take my wife's name on your lips!"

"Look! I thought so."

The boat, poised for an instant on the crest of a great wave, suddenly lunged forward, raced madly down a watery slope, and thrust its nose deep into an opposite swelling wave. It did not come up. Long did the two men on the steamer watch, but nothing, living or dead, appeared amid the heaving waves.

At last Howard's tense features relaxed.

"Well," he remarked, carelessly. "That's a mark to my credit, anyhow. I've saved your life, Jackson. Please see that you do me no discredit in the ten minutes that you will retain it."

The other glared at him stupidly.

"Susan didn't want me to come," he mumbled. "She said I'd never come back—"

His voice died away into incoherent murmurs.

Howard looked at the man, and his lip curled contemptuously. He said nothing, however, but turned in silence toward where the boat had sunk.

The next instant he started and glanced swiftly around him. His eyes fell on a life-preserver lodged in the broken doorway by the last wave that had retreated from his feet. He snatched it up and buckled it round him; then fastened one end of a rope beneath his arms and thrust the other into the hands of the stupefied officer.

"There! Wake up, man!" he ordered. "Wake up and stand by!"

Jackson stared at him. "Where? What? How?" he mumbled.

"Wake up, man! Don't you see it's a woman!"

As he saw the returning intelligence dawn in Jackson's eyes, Howard slipped to the toppling brink of the bulwarks and stood watching for the next heave of the sea. As it came, with a white rag sopping foolishly on its crest, he waved his hand to the other.

"Give my love to Susan!" he cried, and plunged downward.

Chaos! The sea into which he dived was without form and void. Like a grain of corn in a popper, he was tossed hither and thither, twisted, wrenched at—all sense of direction stripped from him.

There was not one chance in a thousand that he would reach the woman; not one in a million that he could give her the least help if he did reach her; the very attempt became preposterous the moment he touched the water. Only blind chance could avail.

The incredible happened. His arm, striking out, caught the girl fairly round the waist and fastened there. He did not try to get back to the ship; he made no reasoned effort at all; reason was impossible in that turmoil.

He struggled, no doubt, but the struggle was unconscious—a mere automatic battle for life. But he clung to the woman, gasping, with oblivion pressing hard upon his reeling brain.

Something seemed to grasp him around the waist and drag him backward, and unconsciously he tightened his arm on the waist he held, meeting the wrench as the sea withdrew its support.

Crash! Something had struck him cruelly, but struck realization back into his brain. Before he could act, the sea swelled around him again; but when it withdrew once more, he knew what had happened. Jackson was dragging him back to the wreck, and he had struck against its side or on its submerged deck.

It was the deck! By favor of Providence it was the deck! Aided by the drag of the rope, the last wave washed Howard and his prize almost to the feet of the police officer, who braced himself to withstand the back-tow as the water retreated; then reached down and dragged both up to momentary safety.

Howard opened his eyes for one instant.

"Didn't I tell you I would have a drier death on shore?" he gasped before unconsciousness claimed him.

CONSCIOUSNESS came slowly back to Frank Howard. He raised his head, but otherwise lay still, painfully reconstructing the world around him. So tightly was he wedged between a broken ventilator and a skylight coamings that it was only with considerable difficulty that he finally managed to lift himself to a sitting position and stare dizzily around.

He was alone on the deck, which had become much steeper than he remembered it in the gray dawn. Evidently another bulkhead forward had given way, allowing another compartment to become filled with water and causing the bow of the steamer to sink deeper.

In compensation the stern had risen somewhat higher, so that the waves broke against the deck, but no longer rushed violently up it. The sea, too, had gone down, curbed perhaps by the thick mantle of yellow weed that floated all about.

With much difficulty he scrambled to his feet, clinging desperately the while to the ventilator.

"Steady! Steady!" he muttered. "If I tobogganed down into that water I shouldn't get up again in a hurry." He held out his hand and noted its tremulousness. "By Jove! I'm weak as a cat."

Rapidly his brain grew clearer. Ship and sea and sky ceased their momentary whirlings and settled into their proper places. He looked up at the zenith, to which the sun, though still veiled, had indubitably climbed.

"Six hours at least," he soliloquized. "Heavens, I must have been pounded hard to lie unconscious for that long! If the old tub has floated six hours she may float indefinitely. But—"

He stared curiously around him. As far as his eye could reach stretched the yellow gulf-weed, blanketing the blue of the sea. So thick was it that it held the Queen comparatively stationary, despite the strong breeze that pressed against her.

Howard uttered a cry of dismay.

"The Sargasso Sea," he groaned. "We're inside it—far inside it. Great Scott!" His brain reeled again. "Where the deuce is Jackson?" he muttered irritably. "And where's that woman?"

Pat to the moment, Jackson thrust his head out of the doorway of the social hall. His dark face was pallid now, and he glared around him wildly. When he saw Howard standing, his expression brightened.

"So you're alive," he rumbled, surlily. "It takes a devil of a lot to kill some people."

Howard stared at the man curiously. It was hardly the way he had expected to be greeted.

"Yes," he answered, slowly, "it takes a good deal—sometimes. It didn't take much for those poor devils in that boat you wanted to go in. Where's the girl?"

Jackson jerked his hand over his right shoulder.

"She's in there," he responded. Then he hesitated for an instant. "It was a brave thing you did," he finished, grudgingly.

Howard shrugged his shoulders.

"Merely a choice of deaths," he answered. "I expected the ship to sink any minute, and, personally, I preferred to die fighting. How is she?"

"She's breathing, but that's all. She hasn't moved since I got her aboard."

"No wonder. She really hasn't any right to be alive after what she went through. Have you done anything for her?"

"I didn't know what to do. I took her into the social hall and laid her on the sofa and got some whiskey for her, but I couldn't get her to take it, and she looked so horrible and—" He paused, evidently shaken.

Howard stretched up his hand.

"I must see her," he declared. "I'm pretty shaky still, but if you'll give me a lift I'll try to scramble up beside you and then we'll see what we can do." He took the hand that Jackson offered. "Now brace yourself," he warned. "All set?"

Jackson nodded, and Howard, after an experimental tug or two, put forth all his strength and drew himself up to the other's side.

"That's good," he remarked. "I guess we're both worth a dozen dead men yet. By the way, how did you get the girl up here?"

Jackson showed more animation than he had yet done.

"The deck wasn't so steep when I moved her," he explained. "It tilted worse just as I got her inside. I thought at first we were going down, but we didn't."

Howard stepped inside the social hall—which had never before so belied its name—and looked around him. After the bright light of the deck, the room seemed dark, and for a moment he could see nothing. Then he caught a glimpse of something lying on the big athwart-ship sofa, and scrambled over to it.

A girl lay there in a crumpled heap. In her rich golden brown hair alone was any touch of color. Her eyes were closed and her lips blue. Her cheeks were so bloodless that it seemed impossible that she still lived.

Once she might have been pretty—even beautiful—but the sea had robbed her of all charm, leaving only the pitifulness of youth and womanhood. Howard drew a long breath as he looked at her, and a sudden rage rose within him. She should not die! He had torn her from the sea. She should not die!

Fragmentary ideas as to the proper thing to do came back to him. He bent down, chafing her wrists and temples; and then, raising her head, touched Jackson's bottle to her lips. A long, shuddering sigh shook the girl's body, and Howard saw a pair of brown eyes open and stare up at him; then close wearily. Again he raised her head. "Drink," he commanded, as he poured the spirit between her parted lips.

As the strangling liquor went down, the eyes flashed open again, and the girl shook from head to foot with a coughing—so violent and so prolonged that Howard feared that he had overdone his task.

But it soon passed, leaving her conscious.

For a moment she lay still, vaguely puzzling over her situation. Then recollection returned with a jerk, and she sat up.

"I remember," she gasped. "Oh, that dreadful wave! To see it come down, down, down—Where am I!"

"You're back on the Queen. It's all right. Try to keep cool. You'll be better in a moment."

The wonder grew in the girl's eyes. "The Queen!" she murmured. "The—Queen! How did I get back?"

"The waves washed you back and we managed to pull you on board. You had better rest a while. You have been unconscious a long time."

The girl looked from one to the other.

"Thank you! Thank you both," she murmured. "I can't find words now, but—the others! Were any of them—?"

Her lips moved, but no sound followed.

Howard bowed his head, but he answered unflinchingly—better the clean, sharp cut of certainty than dragging suspense.

"You were the only one in your boat who was saved," he answered quietly. "I know nothing of the other boats."

The girl covered her face with her hands. "Oh, poor people!" she moaned. "Poor, poor people!" Then she dashed the tears from her eyes and dragged herself to her feet, holding fast to the back of the sofa.

"I am Miss Dorothy Fairfax," she said, with a pretty access of dignity. "And you?" Her eye traveled from one man to the other.

If Howard hesitated, it was for so short a time that it passed unobserved.

"This is Detective Jackson, of the New York police," he answered steadily, "and I am Frank Howard, his prisoner."

"Frank Howard! Not—not—"

"Yes."

"My God!" For the first time in her life, Dorothy Fairfax fainted dead away.

AS Dorothy fell Howard caught her in his arms and laid her upon the sofa. Then he faced Jackson.

"Nice thing, this!" he remarked, grimly. "A very nice thing, considering the state of affairs. No!" he interjected, as he saw Jackson's eyes wander to the girl. "Don't worry about her just now. She's exhausted, anyway, and she'll sleep it off and be all the better when she rouses. Meanwhile, there's work for us. We all need food, and it's imperative that we should find some at once. Come."

The angle of the ship's deck made examination both difficult and dangerous; but when, by the exercise of care, it had been safely carried out, it was evident that the voyagers need not fear either starvation or thirst for a long time to come. The store-rooms of the Queen were above, though only just above, the new waterline, and in them there was food for months to come.

It was good food, too, intended for the consumption of passengers who paid well. In addition to canned goods, of which the stock was large and varied, there was a quantity of ice and fresh meat, fresh vegetables, flour, biscuits, sauces, breakfast foods, and so forth, to say nothing of wines, liquors, and tobacco.

With water the ship was equally well supplied. Not only was the saloon scuttle-butt full, but, after some search, Howard found two large tanks whose contents had not even been touched. In the pantry, just forward of the saloon, was a refrigerator with cooked food enough for two or three days.

All these things were not found in an instant. As it chanced, the pantry came last; and the moment the cooked food was discovered, further investigation was promptly suspended and preparations made to comfort the inner man. A plentiful supply was quickly transferred to the big saloon-table, where it was held in place by the fiddles, which had been put on the night before at dinner and had not been removed.

Leaving Jackson to brew the coffee, an art in which he asserted that he was proficient, Howard went to see after Miss Fairfax.

As he had expected, he found her sleeping, her swoon having quietly passed into slumber. A little color had come back to her cheeks and to her lips, and her breathing was regular.

For several moments he stood looking down at her, noting the sweep of her long lashes on her cheeks, the delicate penciling of her eyebrows, and the pure curve of her parted lips. She was of his own class in life and—He checked his thoughts shortly.

From this girl and all connected with her he had been cut off by his trial and his sentence. Had it not been for the storm and the wreck, he would never have spoken to one of her kind again.

Suddenly he realized that her eyes were open and that she was regarding him curiously. The next instant she blushed furiously and struggled to her feet. Howard did not offer to help her; he did not dare to.

"Oh!" she begged. "Please forgive me."

Howard mumbled something indistinct. He was too much surprised to speak clearly. Miss Fairfax, however, did not accept his presumably polite disclaimer.

"No, but really," she reiterated, "I owe you an apology. It was very silly of me to faint. I was exhausted, and the discovery—"

"The discovery that you were alone at sea with a detective and a convicted murderer appalled you—as well it might. Do not blame yourself, Miss Fairfax, and do not think that I am sensitive. No man can go through an experience such as mine and fail to have his cuticle thickened. Give yourself no uneasiness about me."

Dorothy began to reply, when suddenly the dinner-gong rang out imperatively.

"What's that?" she gasped.

Howard smiled. "That's Jackson," he explained, "and he's hungry. Will you come to dinner?"

But Dorothy did not come to dinner at once. When she did, ten minutes later, after a visit to her stateroom, which luckily was far aft and consequently above water, Howard noted with amused surprise that in those few minutes she had managed to bind up her tangled hair and change her dress for another. She glanced at the table as she approached and flushed at Jackson's glum looks.

"Oh!" she cried. "Why did you wait? I told you not to." She slipped into her seat. "I'm so hungry!" she sighed.

The hot coffee and the abundant meal lightened the spirits of the trio in spite of the predicament in which they found themselves. With a ship, albeit a crippled one, under their feet and with plenty of food and water at hand, it was not in human nature to despair, especially as the sea had gone down so much that it no longer threatened them.

To both Jackson and Miss Fairfax the worst seemed to be over; in a day or two some one would pick them up, they thought, and all would be well. Howard alone, wiser in the ways of the sea, doubted. He listened to the others' hopeful prognostications, but said little.

"I must study the situation before I can say anything," was as far as he would commit himself, even in answer to a direct question.

When they had finished their meal, Dorothy rose.

"I'll clear away these dishes," she announced. "I'm sure you two have more important things to attend to. Later, when Mr. Howard has studied the situation, as he wishes, we will hold a council of war."

Howard bowed and went on deck. His first glance assured him that his worst fears were true. The Queen was evidently far within the Sargasso Sea, and under the impulse of a strong breeze from the west was steadily driving eastward, into ever-thickening fields of weeds.

Wreckage was floating here and there, mute evidence of disasters that had occurred, perhaps close at hand, perhaps thousands of miles away. The passages of open water that had trellised the sea an hour before had disappeared, and with them had gone whatever faint hope Howard might have had of rescue.

No skipper would venture into that tangle; no boat could move through it; almost it seemed that one could walk on it; yet Howard knew that any one trusting to that deceptive firmness would drown, and drown without even a chance to swim. The weeds would coil round him, soft, slimy, but strong, and drag him down.

Like all who have sailed these waters, Howard had heard many tales of the great Sargasso Sea, and had whiled away many an hour listening to the sailors' yarns of the haven of dead ships buried far within those tangled confines—a haven in the middle of the ocean, a haven without a harbor, a haven where the ships, dropping to pieces at last by slow decay, must sink for two miles or more before they reached the floor of the ocean.

And into this haven the Queen was drifting, slowly but surely. Nothing but sinking could prevent her from moving onward till she reached the innermost haven.

What would it be like? he wondered. Would the wrecks really be crowded together so that one could pass from one to the other? That there had been plenty of them borne in to make a very continent of ships he did not doubt, but had they floated long enough to accumulate to any great extent?

The sailors declared that the sea was as large as Europe; that the weed was impenetrable over an area larger than France; that there might well be an area of massed wreckage two or three hundred miles in diameter. But these were sailors' tales. Would they prove true?

"Well?"

Howard turned around. Dorothy and Jackson had come up behind him and were staring curiously over the weedy sea. "Well?" reiterated the latter.

Howard hesitated.

"I fear it is not well," he answered at last. "Our chances of escape for the present seem practically nil."

Miss Fairfax paled, but Jackson flushed darkly.

"What are you givin' us?" he demanded, roughly. "The ship ain't going to sink, is she?"

"No. That is not the danger. Look around you." He waved his hand to the weed-strewn horizon.

Jackson looked again. "Well! What of it?" he demanded.

"This! You see how thick the weed is—thicker even than it was an hour ago. I've sailed these seas long enough to know what that means. It means that we have been blown a long way inside the Sargasso Sea."

"No ships come here; sailing ships would lose nearly all their speed, and steamers would lose all of it, for their screws would soon be hopelessly fouled. No vessel will come to rescue us. If we are ever to leave the Queen, it must be by our own efforts."

"What can we do?" asked Dorothy, quietly.

"That is it exactly. What can we do? Frankly, I don't see that we can do anything at present. We have no boats, and nothing but a boat, and a sharp-edged one at that, could make any way through this morass. And every minute we are getting deeper in. The current below catches our sunken bow, and the wind above catches our uplifted stern, and both sweep us eastward—toward the center of the weed. If we took to a raft we would move much more slowly—but we would starve much more quickly—and our chances of being picked up would not be improved."

"But what will become of us?"

"I don't know. It seems likely that we will be swept into the center of the sea, where there are supposed to be thousands of derelicts, the combings of the North Atlantic for four hundred years—I say 'supposed' because nobody has ever seen them, but there isn't much doubt about it."

Jackson laughed scornfully.

"What are you givin' us?" he demanded incredulously.

Dorothy turned to him.

"It's all true," she corroborated, with a catch in her voice. "Only yesterday Mr. Sprigg told me about it. He was wishing for a chance to explore the place, poor fellow. And now—" She broke off and turned to Howard. "Isn't there any chance at all of our being picked up?" she asked.

Howard shook his head.

"None, I fear," he answered, gently. "I am sorry, Miss Fairfax, more sorry than I can say; but I fear we shall be on this wreck or on another for weeks and months to come. So far as I can see now we can do nothing till we reach the central wreckage. There we may find a boat or the tools to build one—ours are far under water—or some other way to escape."

"It will be desperately hard to wait; to drift deeper and deeper into this tangle day after day, hoping that things will change when they come to the worst; but it's all we can do. Meanwhile we can thank God that we have food, drink, and comfortable shelter, and we are on our way to see what no one has ever seen before and returned to tell it. Let's make the best of it."

"The best of it!" Jackson's face was flushed and his eyes distended. "The best of it!" he vociferated. "By Heaven, it's well for you to yap! You're all right here. You're safe from the electric chair here. You can afford to wait and wait. But how about us? How about me? How about my wife and children?"

"It's hard," Howard assented. "It's bitter hard, but—"

"Bah! You're lying to us! You're a sailor and can get us out of this, if you will. You don't want to get out. You hope that you'll get a chance to escape, but, by Heaven, you shan't! I'll kill you first! By God, I will!"

"It's your duty to do so!" Howard spoke quietly, but a spot of red glowed on each cheek. "It is your duty to kill me rather than let me escape. But it is not your duty to insult me. I permit no man to do that, and I warn you not to repeat your offense.

"For the rest, Miss Fairfax, there is some reason in what this man says. The catastrophe which has brought death to so many, and suffering, both past and future, to you, has saved me. I am safe from the electric chair. Anywhere else in the wide world I would have to shrink from every casual glance; would have to lie in answer to every wanton question. But no extradition runs to the heart of the Sargasso Sea. So it might seem natural that I should wish to stay here. In so far, our excitable friend is right. But I give you my word of honor, not as a jailbird, but as the gentleman I once was, that I am even more anxious to get out of here than yourself. I have still a task to do in the world; my view is not entirely bounded by the electric chair. If any faintest chance offers for us to escape, be sure that I will seize it. But I am helpless until we reach the central wrecks and see what aid they have to offer. Then I will do what a man may."

"I do not promise to go on to New York with Jackson, but I do promise to get you and him safely out of this place, if it is within my power to do so—and I believe it will be. Say that you believe me."

It was impossible not to believe this clear-eyed, straight-spoken gentleman, convicted murderer though he were. Dorothy held out her hand.

"I believe you," she said, "and I trust you."

Howard looked at the hand doubtfully.

"That is not nominated in the bond," he suggested.

"Then we'll put it in," returned the girl. "As for what you have done in the past—I have forgotten it. We will all forget it—till then."

"So be it—till then!"

The hands of the two met. But Jackson, standing aside, grunted scornfully.

"I'll not forget it," he growled. "Not for a single minute; not till I get you to New York. I've known your smooth-spoken sort before."

TWO weeks passed without change in the situation, except that their end saw the Queen still deeper in the tangle. The breeze from the west had continued, but day by day had grown fainter, until at last it barely cooled the faces of the weary passengers. Day by day, too, the weed and the wreckage in the tangle grew thicker. Here and there floated broken spars, fragments of shattered deck-houses, moss-grown planks, Jacob's-ladders, and all the fugitive spoil of the sea. Broken boats, bottom upward; rafts with tumbled fragments of canvas screening perhaps some terrible burden; a red buoy wrenched from some coast harbor; a bottle with a little flag bobbing above it—these appeared, grew nearer, and dropped astern, sometimes just out of reach of the Queen.

Several times abandoned ships appeared; one with a patch of sail gave Jackson some agonizing alternations of hope and despair before its final nearness forced him to admit that it, like their own vessel, was a derelict, bound for the port of dead ships. None of this wreckage, however, kept pace with the Queen. The tallest caught the wind and the deepest caught the current, but the Queen caught both, and moved ahead accordingly.

The marvel of it all affected the voyagers according to their several natures. Jackson took it hardest. Used to the roar of New York and to the electric contagion of great crowds, and without resources within himself, the comparative solitude and the uncertainty drove him frantic. Had he been alone, he would never have lived so long; despair would have robbed him of his wits altogether and have driven him to end it all by a plunge over the side. Even as it was, his state caused his companions grave alarm. Howard took care never to let him be very long out of his sight by day. Fortunately, he slept like a log at night, and Howard was able to lock him in his room late and release him early without his ever discovering that he had been confined.

This state of affairs, however, could not continue. Day by day the detective grew more and more surly, until Howard began to long for the open conflict that was sure to come. Had they two been alone together, he would have speedily brought affairs to a crisis, but the misery of Dorothy's position should anything happen to himself made him hold off, hoping that Jackson's mood might pass. The worst of it all was the man had a revolver—the only one on board.

For the rest, Howard seemed to be not at all troubled. In fact, so far as Jackson knew, the situation worried him not at all. Only Dorothy, who, light-footed, had once come upon him unheard and found him on his knees with bowed head and shaking shoulders, suspected that his lightheartedness was assumed. On that occasion she had stolen away as silently as she had come.

As a matter of fact, Howard, though wild to get back to the task of which he had spoken to the others, was yet not anxious to go to execution. Moreover, the wonder of the situation appealed to him mightily, and he tried to be content to grasp the hours as they came, and not to worry over the future. After he had thoroughly explored the reachable portions of the vessel and had worked out their position as well as it was possible with such makeshift instruments as he could devise, he had devoted himself to the study of the myriad life that swarmed among the weeds. A scoop, trailed overboard for a few minutes, invariably brought aboard hundreds of living forms.

Something of a naturalist already, he took delight in studying the sea creatures, and in noting the marvellous protective resemblances by which they hid from foes or crept upon enemies, themselves similarly equipped.

In this study he was enthusiastically joined by Dorothy. No past record of crime could prevent the intimacy that sprang up between these two, so like in tastes and training, thus thrown upon each other for human companionship. Again and again Dorothy told herself that she ought to shrink from Howard and confine their intercourse to the needs of bare civility, and, accordingly, for a time she would devote herself to Jackson and let Howard go. But Jackson, blameless police-officer as he was, had no resources within himself to long content an educated girl like Dorothy, and soon she would drift back to Howard's side—much, it must be owned, to Jackson's relief.

Curiously enough, the girl was not unhappy. The situation, as yet, was too novel for that. The fact that she could see no possible means for rescue did not greatly trouble her. With the natural resilience of youth, she threw off her anxiety; with the natural trust of woman in man, she was content to leave everything to Howard, and to put implicit faith in his promise, vague and unsubstantial though it was, to do what he could to save her. This was the more surprising as he had as yet had no chance to prove himself capable. Nevertheless, Dorothy threw all responsibility on his shoulders and concerned herself no more about the outcome. If sometimes uneasy questions assailed her, she drove them away. There was nothing to do but to trust him. After she had attended to the meals—a duty which she insisted upon taking on herself after the first day—she would join him at his nets, and together they would pass away the hours. They grew very friendly in those days, especially in the long silences of sympathetic understanding that ever bind heart to heart.

One day, the fifteenth since the storm, after one of these silences, Dorothy turned to the man impulsively. "Mr. Howard," she exploded. "You say you are not thin-skinned. Won't you tell me something about your case?"

Howard flushed. "To what end, Miss Fairfax?" he asked quietly. "I can say that I am innocent, of course; but that is what every convict in the land says. I could not convince the jury. Is it not better that I keep silence till I can get the proof?"

"Nevertheless, tell me."

"Certainly; if you really wish it." Howard's tones were coolly impersonal. "On May 8 of last year, I received a letter in a woman's writing. It was short and I remember every word of it. 'Dear Frank,' it said, 'I am here. Come to see me at once. Dolores.' Then followed the address. Perhaps I was foolish to go, but I did go—to a cheap lodging-house, where the landlady told me to 'go right up' to the third floor and knock on the door marked 8. The door was ajar, however, and as I got no answer to my knock, I pushed it open and looked in. A woman's body was lying on the floor. Again I was foolish. I should have summoned aid at once. Instead, I went in, and stooped over the body. Immediately I saw that the woman was dead; strangled apparently. As I rose to call for help, the landlady appeared at the door. Probably the inference she drew was justified; at any rate, she tried to blackmail me, and when I refused to submit she shrieked and summoned assistance. She declared that she had seen me choking the woman, and I was arrested. Later it developed that some one passing under my name had married the girl—for she was nothing more—in a little village near San Juan at the very time my ship was stationed there."

"That, of course, furnished the motive for the crime. I had, so it was charged, married the girl and deserted her. Later, when she followed me to New York, I had sought her out and murdered her. There were plenty of people to swear to the marriage and to send in affidavits identifying my photograph as that of the bridegroom—though, as it seems, none of them had seen very much of him. Only the minister who performed the ceremony was doubtful, and him my lawyers arranged to bring to New York. He started, but his ship was wrecked and he was drowned on the way. All I could say was that I had never seen the girl until I looked on her dead body, and that went for little."

"Evidently, the girl thought that she had married Frank Howard. Perhaps she did marry a Frank Howard; the name is not uncommon. Perhaps she married some one deliberately masquerading under my name. I do not know. At all events, the case was complete against me, and the jury found me guilty without leaving their seats. I escaped and went to Porto Rico to look for evidence, but I was captured before I could find it. That is all, Miss Fairfax. I cannot blame you if you agree with the jury."

"But I don't—"

The sentence was never finished. Jackson, who for two hours had been standing by the rail, staring northward, suddenly whirled around and came toward the two, pistol in hand.

"Put your fists up," he ordered Howard tensely. "Up! Quick! Hang you!"

Taken by surprise, Howard could do nothing but obey.

Jackson laughed madly. "You've run things just about long enough," he grated. "We've been driftin' in this wreck for two weeks now and I'm dog tired of it. I ain't no sailor, but I know when a man's givin' me the double cross, and you're doin' it. You've got to get us out of this."

Howard's face grew dark. "Kindly specify?" he said. The other glared at him. "Don't you try to bluff me with your big words," he shouted. "I won't have it. You've been lettin' on that you wanted to get us out of this and all the time you've been lettin' us drift deeper in. You don't want us to get away at all, for all your smooth talk."

"I told you that I was helpless until we reached the central mass of wrecks and—"

"Yah! You and your mass of wrecks! I ain't no come-on. You can't work no con game on me. I never took no stock in those fairy tales, but I thought I'd let you play your game out. Now I'm tired of it, and it's up to you to do something quick!"

Howard shrugged his shoulders. "With pleasure," he agreed, "if you'll kindly tell me what to do."

"How do I know? I ain't no sailor. You are! And you're going straight back to your state-room and stay there till you study out some plan to get us out of this. You belong in quod, anyway, and you're going to stay there—with the bracelets on, too, until you get us out of this. March, now."

But Howard shook his head. "I'll never wear irons again," he declared. "Never! You're armed and I'm not. You can kill me, but you can't jail me. Make up your mind to that. As for the central mass of wrecks, it must exist; it's impossible that it should not exist. The only question is as to the area it covers. If you can—By Jove!"

His eyes left the detective's face and travelled into space. "Fool," he cried, "look yonder."

Jackson laughed scornfully. "Not good enough," he cried. "You can't fool—"

But Dorothy broke in. "Land! Land!" she cried.

In spite of himself the detective looked around. Through the haze before them loomed what seemed to be the bulk of an island, set with lofty tiers and dark beaches on which white houses gleamed in the setting sun. So real it seemed that the happy tears streamed from Dorothy's eyes. "Oh!" she sobbed, "it's land! land! land!"

Howard's voice came to her from afar off. "No," he murmured, sadly. "It is not land. It is wreckage. We have reached our destination."

Moved by a slight breeze, the haze shredded away and there, on the waters before them, stretching away to right and to left, lay an interminable mass of wrecks of every shape and description, banked together so thickly that they seemed to touch—and did touch—each other. Dead! all of them. Some newly dead; others long dead; but all unburied, waiting in the haven of dead ships for the long-deferred end. The trees were not trees, but masts hung with ravelled cordage; the beaches were the black hulls of ships; and the white houses were deck-houses or patches of canvas.

For a moment no one spoke. Dorothy stood staring, every muscle tense, while the tears dripped slowly from her distended eyes. Jackson's mouth fell open; his pistol hand fell nerveless to his side. For the first time he realized the situation.

As they gazed, the sun with tropic suddenness dropped below the horizon and hid the scene.

Howard's voice broke the silence. "Now," he encouraged, "we can get to work."

IT was late that night before the voyagers dropped into uneasy slumber. The wonder of their situation, suddenly brought home to them, had roused them all to unusual volubility. In the excitement consequent on the discovery of the massed wrecks even Jackson forgot his suspicions, and the three talked together freely. Howard had promised that they should join the wrecks, and they had done so. Now he would have a chance to keep his other promise to get them out; in the first flush of arrival they did not doubt that he would do so.

But Jackson, at least, changed his opinion the next morning when he came on deck and viewed the scene before him.

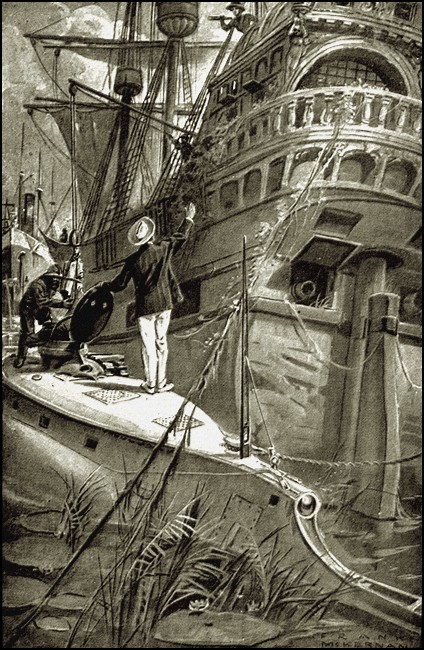

During the night the Queen, drawn by the same natural attraction that holds the planets in their sphere and brings floating chips together in a basin, had taken its place with the dead ships. Under her counter lay a water-logged schooner; beside her rubbed a dismasted sailing ship; over her submerged bow hung a tramp steamer, whose blackened masts, bare of cordage, gave evidence of the flames that had ravaged her. Beyond, stretched a mass of wreckage, ship pressing upon ship, in an endless iteration of ruin. Only to the west the view was open, and there stretched the weed in slimy convolutions.

Over all screamed the sea-birds.

Each of these countless wrecks had once sailed the sea, new and strong, and each had come here at last to slumber peacefully until the deep should open and receive it. No more would they ride out the hurricane or take with frolic welcome the buffetings of the waves; no more would they visit the great ports of men and groan beneath the heavy cargoes placed upon them. Their days of turmoil were over. Here, in this quiet haven, in the great calm of the tropics, with only the faintest breezes to whisper into their ears tales of the open sea, and with the birds to nest in their deserted rigging, they dreamed their old age away.

To Dorothy the sight was solemn, but not sad; to Howard it was amazing; to Jackson it was maddening.

Less than ever did he believe that he was hopelessly trapped far out on the ocean; more than ever was he convinced that Howard was deceiving him for his own ends. He saw the ships rocking gently on the swells, noted white patches of sails showing here and there, heard the cries of the gulls, and told himself afresh that he could easily walk ashore if he only knew how; and when a flock of parrots lighted in the rigging and demanded crackers, and a monkey poised on the end of a near-by mast and gibbered, he was convinced beyond peradventure that Howard had lied to them and was only watching his chance to desert them. He did not even listen to that officer when he explained that both birds and beasts must have drifted in on wrecks and had probably thriven.

"The birds will feed on the roaches on the old rattle-trap wrecks," he explained, "and the monkeys will live on the birds' eggs. Perhaps, too, both catch shell-fish in the weeds."

Breakfast was a silent meal. Dorothy was awed and frightened by the sight of the wrecks, and Jackson was glum. In vain Howard strove to rouse them. Finally he gave up and finished his breakfast in silence. Then he pushed away his plate.

"Listen to me, please," he said coldly. "We have arrived at our destination and must now take steps to help ourselves. Two things are necessary: first, to explore the ships around us; second, not to get lost. Make no mistake; the danger of this last is very great. These ships will not look the same as we leave them and as we return to them; where we climb down a ship's side in going away, we must climb up it in coming back, and vice versa. Often this may be difficult; sometimes it may be impossible. Yet, if we try to vary our route, we may lose ourselves; and once lost the chances are a thousand to one against our ever finding our way back to the Queen again. Not that we shall stay by the Queen long; probably we shall soon find some ship better suited for a base of operations. But we must remember that this continent of ships is a desert except around its edges. New wrecks arriving will bring food and water, but a few hundred yards inside the borders neither can remain. It may seem to you that it would be easy to get back to the border again, but I assure you that it would not be. Without a compass, we would not know which way to go, and might easily be plunging deeper and deeper into the mass."

He paused, waiting for comment, but none was made. He was leader, however grudgingly so, and it was for him to map out their course of action. No one dreamed of disputing it—Jackson, no less than Dorothy, realized his helplessness and his ignorance.

"I beg you, therefore, to be very careful," resumed Howard, seeing that the others waited. "I am particularly insistent, because we must explore first of all. To-day the danger is not great, because we are not likely to get far away, but we might as well start right. First, we must run up all the signal-flags we can find; they will be conspicuous for a long ways off. Next, we must light a fire in the galley range; its smoke will be visible still farther away. Third, we must never go out of sight of our base—the Queen, at present—under any circumstances; when we climb to each new ship we must look back and make sure that we can still see the flags or the smoke. Fourth, we must each carry a hatchet and mark our way just as a woodman blazes a path through a forest; the hatchet will come in handy, anyhow. Later, if we do not find what we want, we can shift our base to some other vessel along the 'coast,' and explore farther with that as a new center. Do I make myself clear?"

Dorothy nodded. "Shall we all go together?" she asked.

Howard shook his head. "No, I think not," he answered gently. "I hope you will be willing to stay here for the present and keep the galley fire alight; I'll show you how to make it smoke. Jackson and I will do the exploring for to-day, anyway. He can go to the north along the coast, and I will go to the south, and—"

"Not much!" The policeman was shaking his head doggedly. "Not much, you don't. I don't leave you out of my sight. I've got my orders from headquarters and—"

Howard stifled an exclamation. "Very well," he said coldly. "As you please! Perhaps it is better anyway. Two can do things that one could not. Come! Let's get ready."

"But—" Dorothy looked very dubious.

Howard turned to her. "I know what you would say, Miss Fairfax. You would like to go, of course. But, believe me, it is best not. Moving about these wrecks will be difficult and even dangerous for any one hampered by skirts. You would be exhausted very soon. Besides, we may meet unpleasant sights. Later, when we know our ground better, we will take you for a sight-seeing tour. You will be perfectly safe on the Queen. You are not afraid to be left alone, are you?"

"Oh! No! It will be lonely, of course, but isn't there some way that I can signal to you if anything should happen?" Howard considered a while; then plunged down into the vitals of the Queen, returning shortly with a double armful of straw dug from a hogshead once filled with crockery.

"There," he said, dropping it at the entrance of the galley. "If anything happens, wet some of that and put it on the fire; it will make a thick black smoke. By alternately closing and opening the draft, you can let it go up and cut it off altogether. We'll watch for it."

Howard and Jackson climbed down the Jacob's-ladder that still swung at the Queen's counter, and dropped lightly to the deck of the water-logged schooner that lay there. Of this, nothing but a few inches of the deck and the stumps of the masts were above water; whatever deck-houses there might have been had been carried away, together with the entire rail. Consequently there was nothing to investigate, nothing that could help the castaways in their efforts to escape, and the two men crossed over her with merely a glance, using her as a bridge to reach a ship floating high in the water just beyond.

The second vessel had a gangway lowered down her side, evidently to help her passengers to reach the boats. Her masts were gone, but otherwise she seemed intact.

"Crew and passengers taken off by another ship," explained Howard, "probably in fair weather after a storm. Most likely another storm was brewing and the crew expected their own vessel to sink."

A rapid search showed that the ship had nothing of value to offer. Her boats were gone; her compasses, charts, chronometers, and sextants all were gone. Some tools remained, but were so rusted as to be of little value. Howard soon led the way to her taffrail, whence he could clutch the shrouds of a full-rigged ship which had evidently been in a collision.

As he stepped on the deck of this craft, there was a scurry of feet, and a dozen huge rats bolted across the deck and disappeared under the poop.

"Confound the brutes," he muttered. "I hate them! Wonder what they have been eating."

The answer was not far to seek. Close beside the davits of the quarter-boat lay two skeletons; one with a smooth, round hole drilled through the fleshless skull, the other with a broken backbone. Howard looked at them and nodded.

"Probably the crew made a rush for the boats," he suggested. "Somebody—one of the officers, I suppose—tried to stop them. He shot one, but the others ran over him and broke his back. Then came the rats. Well, it was a man's death. If you can find a couple of bags, Jackson, we will commit the bones to the sea."

From the ship the two men descended to a steamer, much down by the stern, with a gaping hole in her port counter, where something must have driven deep into her vitals. From this they climbed upon a small yacht, floating just awash. ("Held up by water-tight compartments," explained Howard.) Thence they passed to another vessel, and to another, and another, each bearing mute record to the manner of its ruin.

But on none did the explorers find what they sought. The boats were invariably gone; the tools were always rusty; the compasses had all been snatched from the binnacle and from the cabin; the charts had mostly been torn from the racks and tables, often so roughly that the thumb-tacks that had held their corners were left in the board, each holding a triangular scrap of torn paper. In the few instances where any did remain, they were rotten with mildew, and charted regions far distant from the Sargasso Sea.

It was noon when Howard gave the word to return to the Queen. "Don't be downcast, Jackson," he consoled. "What we have found to-day is only what we had to expect. The boats would, of course, be taken, even if everything else was left. The compasses, and charts, and sextants, and so on, would naturally be taken next, for those who went in the boats would need them to shape their course. The tools and engines would have almost invariably been left exposed to the weather and would be badly rusted. It would have been by mere chance had we found what we wanted on the very first day. At least we have learned that there is plenty of food and water and clothing and coal to be had for the taking. To-morrow we will search in another direction. Now, let's go home."

But return was not so easy as the two men expected. As Howard had foretold, there was an important difference between climbing up and climbing down, and this difference was accentuated by the fact that in leaving the Queen they had chosen the easiest route. When they could have gone from one ship to any one of two or three others, they had naturally moved to the one that appeared the least difficult of access.

Taking the route in reverse, this small detail of choice often meant that they must return to the one that was the most difficult to board.

To this expected obstacle was added another that was unexpected. In more than one instance they found that their morning route, as shown by their blazed marks, was absolutely impracticable. The ships had moved, slightly perhaps, but yet enough to bar their passage, ten feet of water being often as impassable as ten hundred. Howard struck his brow with his hand when he realized this.

"I was a fool not to foresee this!" he exclaimed. "Of course, these ships are not absolutely stationary. Even far inside they must be somewhat subject to currents and to winds, and must move slightly, while here, on the outskirts, they must move considerably. As a matter of fact, the whole mass must be swinging around and around in a vast circle, moved by the same current that brought them here in the first place. Well, we must simply abandon our blazes, and go home by the flags and the smoke."

Jackson peered into the distance. "I can't see no flags," he objected.

"Can't you? I can, but they are undoubtedly hard to make out in this mass of frayed cordage and flapping streamers. However, we can see the smoke clearly enough, and must set our course by it."

Ten minutes later the first accident of the day occurred. In stepping from one ship to another, Jackson missed his footing, caught wildly at a ratline, which broke in his grasp, and shot downward with a veil into the water.

By the time he had risen to the surface, Howard, who had been a little in advance, was back, peering down at him.

"Can you climb out?" he demanded. "No! I guess you can't without help. Hook your fingers into that port-hole—there, just behind you. That's right! Can you hang on for a while? It may take some time to find a rope sound enough to bear your weight."

Jackson clawed the weed from off his face. "Yes! I can hang on all right," he returned, savagely. Evidently his involuntary bath had ruffled his temper. "I can swim, too," he added.

Howard disappeared, and the policeman settled himself to wait. He had learned to swim in the North River, and had no difficulty in keeping afloat, even without the adventitious aid of the bull's-eye in the steamer's side just above him. If he had fallen in almost anywhere else he could have gotten out himself, but, as it chanced, this particular bit of water was shut in by the sides of three ships, none of which offered a foothold by which to climb. The bull's-eye by which he hung was the only orifice that broke the smoothness of the overhanging sides.

Time passed, however, and Howard did not return, and a vague uneasiness began to work in the policeman's mind. There were ropes everywhere. Surely, it did not take so long to find one. He called, but received no answer. Could Howard have lost the place? Or could some accident have befallen him? Or, could—good God! Did the man mean to leave him to drown?

The suggestion, once offered, would not down. It was, he told himself, the very thing to be expected. With him out of the way, Howard would be freed from the shadow of the gallows. He alone—except Miss Fairfax, and what was a girl's life—he alone knew that Howard had survived the wreck of the Queen. With him dead, Howard—supposing that he could regain dry land—could live out his life in safety. And what was a policeman's life to one whose hands were already stained with the blood of his own wife?

Jackson drew a long breath as conviction forced itself upon him. It was characteristic of the man that he did not whimper. He had been dealing with criminals for twenty years, and conceded them the right to fight for their own hand. He had always declared that he would take his dose when it came without doing the baby act; and, by George, he would keep his word.

Hope had vanished when Howard reappeared. In his hand was a boat's tackle, which he proceeded to hitch to a davit that projected over Jackson's head. But, instead of dropping down the other end, he quietly seated himself on the bulwarks and stared thoughtfully at the man below.

"Well, Jackson," he remarked, deliberately, "our positions seem to be reversed."

The policeman scowled. "Damn you, yes," he responded, truculently.

An expression of admiration floated over Howard's face. "By Jove, Jackson!" he cried. "You're all right. I didn't think you had the nerve to speak up like that under the circumstances. 'What dam of lances brought you forth to jest at the dawn with death?' That's from Kipling, Jackson, if you do not recognize it."

"G'wan. If you're goin' to murder me, do it. You've had experience, all right."

"Fie! fie! Jackson! Call things by their proper names. This wouldn't be any murder. But, there"—Howard's voice grew stern—" enough of this. I see you realize the situation. All I have to do is to leave you where you are, and to-morrow I will be a free man. But I am not going to do it; I am going to pull you up in a minute. But I want you to realize that I have deliberately put aside the best chance possible to free myself from your surveillance, and I want you to cease dogging my footsteps and watching me everywhere I go. I don't ask you to let me escape or anything like that, but I do ask you to act on my suggestions without any talk of not letting me out of your sight. Our escape from this wreckage may any day depend on your prompt obedience, and I want you to obey. In return, I reiterate my assertion—which you did not believe—that I am even more anxious than you are to get back to dry land; and in addition I promise you, on the word of an officer and a gentleman, that if I do get back, you and Miss Fairfax shall go, too. I will not desert you, even though I know you will arrest me the moment you have force enough at hand to do it. Now, put your foot in the hook on this block, and I'll haul you up."

Jackson caught the block that Howard dropped, and put his foot in it mechanically. He was a slow thinker, and Howard's words bewildered him for the moment; later he would realize their import. Anyhow, now was the time to act; the time to think would come later. So he grasped the rope and waited while his former prisoner hoisted him up to the deck.

Once there he turned to Howard and opened his month. But that individual checked him with a smile.

"After a while! After a while!" he counselled. "Let's get back to the Queen now. Where's that smoke?"

He turned and gazed around the horizon; then he started.

"Something's wrong on the Queen," he cried. "Miss Fairfax is signalling for us!"