RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"In the Land of the Golden Plume,"

W. & R. Chambers Ltd, London & Edinburgh, 1894

"In the Land of the Golden Plume,"

Variant Cover

"In the Land of the Golden Plume," Title Page

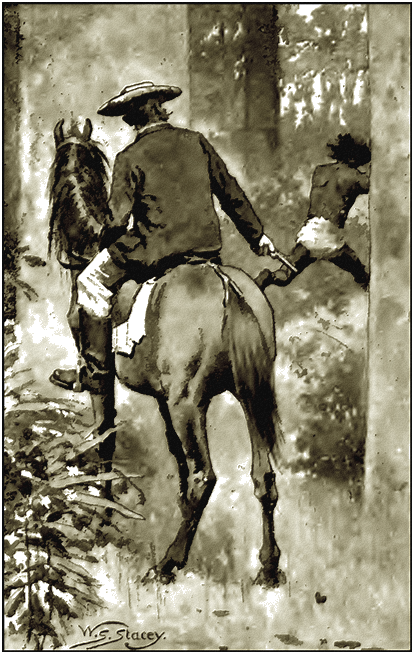

Frontispiece. The boys join their father.

IT is now several years since the natives around Hamilton Gap, North Queensland, made the last attempt to frighten their white supplanters. In those days there were two homesteads at Hamilton, which, lying at the base of a range of scrub-covered mountains, nearly two hundred miles up country, was (and, for that matter, still is) the outpost of civilisation in that direction. The principal run included the low ground on both banks of the Hamilton River, and belonged to a settler named Maitland; the other, greater in extent, but not so valuable, comprising as it did the slopes of the hills, to Mr Dennison. Little Ruth Maitland could remember the time—it was before the date of her father's misfortune—when there were but five white people in the district, of whom she was the youngest, but not the least important. Then came Mr Dennison, followed in a year from Sydney by his two boys, Walter and Frank: the first playfellows she had known. For three years they had grown up together, sharing in each other's lessons and scrapes, mastering the queer dialect of the tame blackboys (natives), and listening together to their stories of the customs and exploits of their forefathers before the coming of the English, and their warnings of what their wild brethren might still do if the intruders neglected the smallest precaution. It was not long before these warnings were justified by the event.

Although Walter Dennison, the eldest of the three, was not more than eleven when the incident happened which begins this story, he is not likely to forget it while he lives. It was his first excursion with his father into the mountains, whither Mr Dennison was in the habit of exploring in search of gold. Two of their own blacks were with them, and they were returning after three days' delightful but unsuccessful journeying—delightful to Walter, notwithstanding the absence of adventures with the bushmen such as his imagination had led him to expect. Just as dusk had fallen, the little party of four arrived at a point within sight of home, and drew up to breathe their horses before beginning the descent into the plain. Suddenly Walter, who had dropped behind with one of the natives, was startled by a loud shout from his father.

'Here, Walter! Jimmy! Quick!'

Hurriedly they galloped up, to find Mr Dennison gazing eagerly in the direction of home.

'Look, boy!' he cried, pointing with his hand. 'What do you see? There—straight in front!'

Walter's eyes had already sought the spot, and made out a luminous appearance in the sky. An exclamation of dismay escaped from him: it could mean only one thing.

'Oh! the house is on fire, sir!'

'It looks like it, but'—

Here one of the blacks said something in his own language to his companion. Mr Dennison caught a single word, but it was enough to rouse a vague feeling of apprehension. He turned sharply upon the speaker.

'What! Blackboys?'

The black nodded.

'You're sure?'

'Yohi' (yes).

'And we've four miles to cover,' said Mr Dennison, as if to himself. 'On, then!' No more; but Walter happened to catch a glimpse of his father's face, and saw that it was white and stern-set.

If the instinct of the black was right, it was no time for lingering. So, Mr Dennison leading, they raced madly downhill, escaping as by miracle a hundred dangers; and as they rode Walter thought of Frank, a year younger than himself, at the mercy perhaps of the wild, degraded, treacherous aborigines from the bush. The tribes around Hamilton had never taken kindly to the white man. They had shown this several times by slaughtering the sheep and cattle, and, more than once, by cowardly attacks upon one or other of the shepherds. Attempts had been made to conciliate them; they had met them all with treachery. But for their wholesome dread of firearms, they would doubtless have attacked the settlement itself long ago. And Walter, as he remembered stories of their cruelty to Englishmen who had fallen into their hands in other parts of Queensland, shuddered to think of poor Frank's probable fate. And the rest? There were two white men on the run—Brunton, his father's oversman, and a shepherd called Thomson. The boy had been left in charge of Brunton and several tame blacks of whose fidelity there could be no doubt; for the tame black, on the strength of a pair of shortened trousers and a few words of broken English, has the utmost contempt for his more savage fellows. There was one gleam of hope: the Maitlands' homestead was within a mile, on the other side of the river.

One mile—two miles—and the steepest and most dangerous part of the way had been traversed without mishap. Now and again, through the trees, they saw the gleam of the fire as they dashed along—Mr Dennison first, Walter close behind, the blacks at his heels. Then they emerged from the bush: in another minute they would pass the hut of the shepherd, Thomson.

'Stop!'

Walter pulled up by his father's side.

'We must see if Thomson is safe, Walter—if he is here,' said Mr Dennison.

The little cabin was just visible, looming blacker against the black of the night. As they approached the doorway, Mr Dennison called out softly. There was no answer. Then they noticed that the door was open—next moment, that a form as of a man was stretched across the threshold. Walter, scarcely realising, pressed forward.

'Is it—'

'Ah!' cried his father, quickly. Then, as he dismounted. 'Halt—no farther, Walter! Wait here.'

He took his father's bridle, and waited—watching him as he drew near, stooped over the body, and finally knelt down beside it and gently turned it over. Then he heard his summons:

'Come here, Walter!'

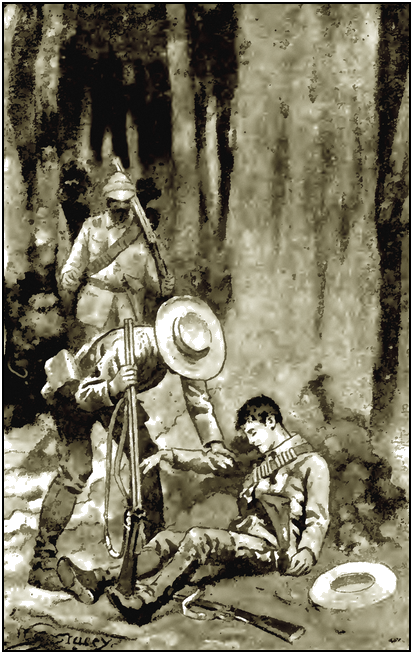

In a second he was off his horse and beside his father. And this is what he saw in the dim light: poor Thomson lying in his own doorway, his revolver by his side, his clothes saturated with blood from half-a-dozen ugly spear-wounds. The boy turned sick as he looked, and for a moment could grasp no more.

A touch of his father's hand on his shoulder recalled him to realities.

'Oh! is he dead?' he asked.

'Hours ago. Poor Thomson!'

In a whisper. 'By the blacks?'

'By the blacks. And foully murdered—see! the wounds are mostly behind.'

'And—and Frank?'

Mr Dennison did not reply, but went and picked up the dead man's revolver. It still contained five charges: only one had been spent.

'Here, Walter—you may have to use it soon enough,' said Mr Dennison, in a hard tone. Then he motioned to the boy to take poor Thomson's feet, and together they stumbled with the corpse into the hut and laid it on the bed. It was the least and, at the moment, the utmost they could do.

Outside, meanwhile, the two tame blackboys had been peering about in the manner of their race; and now a cry from Jimmy, the more intelligent of the pair, told Mr Dennison that the man had made a discovery. Running out, followed by Walter, he perceived him standing over the dead body of a native, in whose heart Thomson's bullet had found its billet. Walter scarcely glanced at it.

'And Frank?' he repeated, plucking at his father's sleeve. There was room in his head for but the one thought. 'Frank?' One instant first. Then—

Turning to the blacks, he addressed them in their broken dialect. They knew of the murder of the shepherd: he told them of the probable danger of those at the homestead, and that themselves were about to venture into the thick of the fighting. Could he depend upon them to help him against the enemy?

The answer was prompt.

'Me fight—me white man blackboy!' cried Jimmy, flourishing the dead native's spear.

'Yohi—me fight too!' cried his companion.

Then Mr Dennison, convinced by their tone of their sincerity, gave the word to continue the journey. Not more than four or five minutes had been spent at the hut, but the little party, haunted by the fear of what might await them, spurred on faster and yet faster. Fortunately there was now a well-defined track, familiar both to the horses and their riders; and they had also the reflection of the fire, flickering behind the rampart of trees which surrounded the house, to guide and hasten them, if that were possible, on their way. The bush was strangely silent. Strain their ears as they might, Walter and his father could distinguish no sound but the drum of their animals' hoofs and the panting of the blacks behind. This until they were within half a mile of their destination; and then, ringing out sharp and clear in the stillness, came the report of a couple of shots fired in quick succession. For the first time for half an hour they breathed freely: at the least, the besieged were still holding out.

'Thank God!' muttered Mr Dennison.

'Again!' cried Walter, as another volley rang out.

Five minutes later they drew up at the border of the fringe of trees surrounding the homestead, dismounted, and waited while Mr Dennison crept forward to reconnoitre. He was back before the blacks had finished hobbling the horses.

'They have only fired the outhouse yet; the house itself seems all right,' he reported.

'Are there many?'

'A good few, I think. They haven't heard us, so we must take them in flank and try a surprise. Don't fire until I do; then, as quickly as you can. And shout, make a noise—you, Jimmy, Tommy, as well. Do you understand?'

'Yes.'

'Then come.'

With that he led the way through the wood in a transverse direction, so as to get well in front of the house without being seen by the enemy. Walter and the blacks, imitating his caution, trod closely in his footsteps. The main buildings stood in the middle of a great clearing, marked out by the boundary-line of trees, and were enclosed by a low paling-fence; and outside the fence were the yards for penning the sheep, and the outhouse which the savages had fired. Although it was now burning low, it still threw a strong light across the space between it and the house—thus giving the defenders, concealed in the shadow of the veranda, an immense advantage over the assailants. But evidently the latter, strong as they were in numbers, dared not attempt to carry the place by storm.

Walter had time to notice this as he crept round, and to notice also the group of forty or fifty natives gathered just beyond gunshot of the homestead. At last his father stopped. He had reached a spot in a direct line with the blazing hut, which was between him and the house, and much nearer to the wood than to the latter. Not until then did the boy understand the bold game they must play for success.

Mr Dennison held up his hand. 'Are you ready, Walter?' he asked.

'Yes.'

'Do as I do, then. And mind! don't break cover until you see me doing it.'

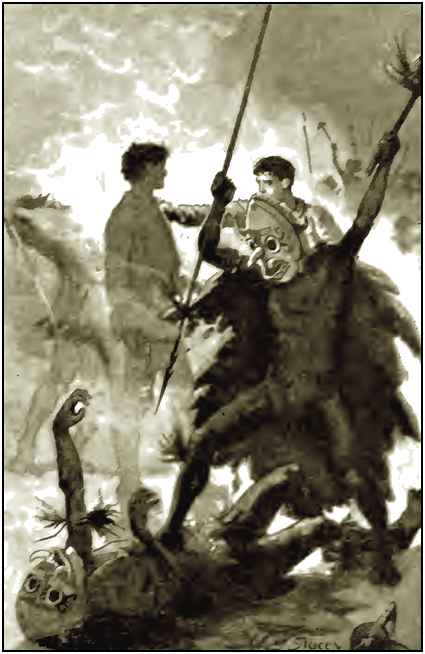

Next moment the struggle had begun. Mr Dennison fired; Walter, pointing his revolver at the group of blacks, did likewise; and Jimmy and the other native, unwilling to be mere spectators, contributed a most unearthly and awe-inspiring howl. Then, without waiting to see the result, Mr Dennison and Walter changed their position and again fired, rapidly but carefully; and did so—Jimmy and Tommy materially aiding to deceive—until it must have seemed to the surprised savages that a large party lay concealed in the wood. The issue was hardly doubtful for an instant. Those in the house, hearing the welcome shots, responded with a volley and a loud cheer. Taken by surprise, and conceiving themselves caught between two fires, the besiegers hesitated only a minute before they turned tail and fled,* followed by parting shots from Walter and his father as they scurried across the clearing to gain the shelter of the wood. It was a complete rout.

(* It should he repeated that the aboriginal inhabitants of Queensland, members of one of the most degraded of human races, had an almost superstitious dread of firearms. To this fact many a settler has owed his life.)

Mr Dennison and Walter, leaving the friendly blacks to see

after their dead and wounded kinsmen, hastened towards the house.

'It's us, Brunton—Walter and I,' shouted the former,

heedless of grammar. 'Are you all safe?'

The oversman appeared on the veranda steps. 'Ay, barring poor Thomson, Mr Dennison,' he answered.

'And Frank?'

'Here I am, father!' cried that young warrior, showing his flushed and eager face—and not forgetting, even in his excitement, to display a revolver with all the pride of one who has just used it to some purpose.

Another defender now came forward in the person of Sam Price, one of Mr Maitland's men from across the river, who had been sent by his master to help, and had managed to get into the house without the knowledge of the enemy. By him and the rest, including the half-dozen faithful natives, Mr Dennison's opportune arrival was warmly hailed. Brunton's story was soon told. The trouble, it appeared, originated the day after his employer's departure, when he had occasion to whip one of the blackboys—a lazy and evil-disposed rascal who had lately been taken on—for some slight act of theft. The man disappeared; but as this was quite a common effect of punishment, no more was thought of the matter. On the afternoon of that day, however, one of the other blacks appeared with the astounding intelligence that a large force of 'wild men' were in the vicinity, and had already speared Thomson. He had been a witness of the murder, had seen that the fugitive was of the party, and in great fear had run all the way to the homestead to give the alarm. Brunton's precautions were speedily taken. First he had sent a native to warn the Maitlands, whence he was to go on to Baronga, the nearest station of the black police,* twenty-five miles through the bush. Then the horses were stabled, and everybody was withdrawn into the house. When at last the bush men appeared, they were received so warmly that they made really no serious attempt to attack the homestead; and thereafter the defenders succeeded in keeping them at a safe distance by firing upon them as soon as they ventured within gunshot. In this they were assisted after dark by the light of the burning hut.

(* The black police, an efficient body of mounted natives, recruited from different tribes, and officered by white men.)

Jimmy now came in with the information that the bushmen had

left five of their number behind them—all dead, he added

significantly. Then the report of a distant shot was heard.

'They have attacked the Maitlands!' cried Mr Dennison. 'Quick! we must ride over to their help!'

'What if it's a trick?' asked Brunton, who was a cautious man.

'A trick! It isn't likely. And even if it is, there's poor Maitland to consider.' For Mr Maitland, you must know, had lately lost the use of his legs owing to an attack of paralysis: a misfortune which, little as he complained of it, rendered the prompt help of his neighbours all the more necessary. Brunton saw this, and changed his ground.

'And the lads?'

'They must come with us. Yes: take your rifles and revolvers. Are yours reloaded, boys? Mind and keep close to me. Ah! there are the horses. Are you ready? Now!'

Of the exciting events of the next half-hour the boys retain but a confused recollection: the swift ride down to the river, the faithful blacks following on foot—the fording of the water—the sight of the Maitlands' homestead in flames—the quick retreat of the cowardly bushmen on their approach, chased to cover by Brunton and Price—ending with the rescue of the Maitlands from the house, to which the natives, adding experience to cunning, had managed in some manner to set fire. They were not a minute too soon, for at least half of the building was blazing merrily. As the Dennisons galloped up, leaving it to Brunton and Price to prevent a return of the routed enemy, two of Maitland's men burst out with little Ruth.

'Just in time, sir!' cried one of them, gently seating the girl on the ground. 'We'd about given up hope when we heard your shots; guessed we had only the choice of being roasted or speared.'

'And Mr Maitland?'

'Waiting his turn, sir. Insisted that the missie should be taken first.'

Dismounting, Mr Dennison turned to his sons. 'I trust her to you, boys,' he said. 'I am going inside for Mr Maitland.'

Crossing the clearing with the two men, he plunged into the burning house; and Walter, as he watched the flames running along the veranda and up the walls until they licked the roof, wondered if he would ever reappear. Frank had no such doubts.

'Don't be afraid, Ruth,' he was saying with his bravest air to the little girl. 'You're all right now. Look! I've got a revolver.'

But Ruth, notwithstanding her implicit faith in Frank, refused to be comforted until presently her father was carried out, chair and all, by Mr Dennison and one of the men, the other following with the strong-box. Little else was saved except the firearms and some clothing, and these only at considerable risk.

'I'm sorry for your books, Maitland,' said Mr Dennison. 'It won't be easy to replace them.'

'I'm thankful we've saved our lives—or, rather, that you've saved them for us, my friend,' replied the other. 'I must say it's more than I expected at one time.—Ah! there goes the roof!'

Fiercely blazed the dry timber of the house, and each of the little group had his own thoughts as he stood there in the reflection waiting for the end. Mr Dennison recalled his first visit to the cosy homestead four years before, when, wearied and worn-out by a twelvemonth's 'prospecting' in the mountains, unsuccessful, deserted by his companions, he had lighted by chance upon the place, and discovered in its master a cultured gentleman and a friend. He had set out after his wife's death in search of gold, leaving his children in good hands at Sydney; and, unlucky and disheartened, he had closed readily with Maitland's proposal that he should take up a vacant run near him. Did he regret it? Well, for three years he had had the boys beside him—for Maitland, after his illness, had offered to undertake their education, and he, observing his friend's success with Ruth, had gratefully accepted—and that was something. But now and again the old fits of restlessness, the desire to wander, had attacked and in some cases, more particularly of late, almost overcome him. Could he resist them much longer?—So he deliberated, while meantime his neighbour was a grim witness of the destruction of his home.

Presently Brunton and Price rode up, bringing the news that the bushmen were in full retreat towards the mountains, tracked by several of the faithful blacks. Nothing more could he done, they said, until the arrival of the black police.

'Except make yourselves comfortable with me for the present,' said Mr Dennison.

'For an indefinite time, I'm afraid.'

'Oh! I don't know,' put in Brunton. 'We'll soon run up a new homestead for you, Mr Maitland, and take good care not to give the blackboys another chance. Trust the troopers for that.'

The troopers arrived next morning, and, to do them justice, did not belie the oversman's confidence. Accompanied by Mr Dennison and two of the men, they set out immediately to punish the savages for Thomson's murder and their other misdeeds. The track to the mountains was marked out by the carcasses of sheep and cattle wantonly butchered. On the second day the tribe was surprised in camp, and—to cut short a long story—received such a lesson that the survivors never afterwards ventured near the settlement of Hamilton Gap.

A week afterwards, when the detachment of police had returned to Baronga, Mr Dennison and his guest were seated in the veranda discussing the future. Maitland made some remark about the rebuilding of his house.

'Is it necessary?' asked Mr Dennison. 'The fact is, Maitland, I was just about to ask you to stay here for good. Wait a minute! What would you say if I told you that I had determined to go on the tramp again, and wanted to ask you to do me a favour? There's the run, but Brunton can manage that as well as myself. As for the boys, I thought that if you didn't mind they might stay here under your eyes—I should like nothing better. In that case, of course,' he added, 'there would be no necessity to build another house.'

Maitland thought for a minute or two. 'You mean to make a long journey, then?' he said.

'To New Guinea, no less.'

'New Guinea!'

'Yes. To tell the truth, Maitland, I have the fit very badly this time. You know the reason. I've told you already of the promise I made to my poor father just before he died. I've been trying to fulfill it ever since—it's twelve years ago now—and I'm as far from success as ever. I seem to have no luck in this country, and so I mean to try if I have any better in another.'

'And why have you chosen New Guinea?'

'Well, I hardly know. I have always had an interest in it, I think. For one thing, it's a new and unexplored country, lying just at our door, inviting us to walk in; for another, by all accounts there's gold in it. And, somehow, I have a presentiment that my luck will change. I might have gone long ago if it hadn't been for—well, for various things.'

Maitland nodded. He understood and appreciated his friend's delicacy in not referring to his misfortune.

'Now there's a favourable opportunity,' Dennison went on. 'The bushmen are disposed of for the next ten years at least, and the Gap's safe for the first time. And the boys are growing up to be of use.'

Maitland smiled. 'In a word, your mind is made up?' he said.

'Yes.'

'Then you must have your way, I suppose. I'm not surprised, for I've been expecting this for the last year.' He held out his hand. 'I won't say I'm glad, but I wish you luck with all my heart!'

'And you agree to my proposal?' asked Maitland, when they had shaken hands.

'I'll do more, old fellow. With Brunton's help I'll do the best I can to manage your run along with my own. When do you leave?'

'In about a fortnight.'

He left sixteen days later.

FIVE years passed, and the wanderer did not return. They heard from him once, about two years after his departure, when he had visited the coast to prepare for a new journey into the interior; and in the letter he had warned them not to be anxious if a long time elapsed without news of him. Anxious they were, however; and it was to relieve their anxiety that Captain Barkham came to Hamilton Gap, in the manner I have now to relate.

MORNING in North Queensland. In the middle of the bush a few acres of scrub had been cleared, the ground planted with various tropical fruits and vegetables, a house and a few rude huts erected, and the result was Baronga, the capital of a district as large as an English county. As yet the population consisted only of a lieutenant of the native troopers and a dozen men, with their wives and several children. Here it was that Captain Barkham, on his way from Cooktown to Hamilton Gap, had spent the night as the lieutenant's guest; and, having breakfasted, was now getting ready to resume his journey.

'How far by the road, did you say?' he asked.

'Close on forty miles. But it's roundabout.'

'And by the bush?'

'Not more than twenty-five.'

Captain Barkham considered. 'The Bingi may be trusted, you think?'

'The blackboy? I don't see why he shouldn't. You may depend upon it he'll play straight until he gets his money.'

'Then I guess I'll take the bush, lieutenant. This cruising about on horseback don't exactly suit me—too much of it, at least—and so the sooner I get to Hamilton Gap the better I'll be pleased. If the horse is ready?'—

The black face of a native corporal appeared in the doorway.

'Horse out, Joe?' inquired the lieutenant.

'Yohi.'

'Stonewall ready to start?'

'Sleepum very fast. Me kick um?'

The lieutenant nodded, knowing well that no gentler method was like to prove effectual, and with a grin of expectation his subordinate departed. A savage enjoys nothing more than to kick another savage.

The lieutenant and his guest followed him into the open air, where the whole population had turned out to witness the start, so seldom was it that Baronga had a white visitor. The captain mounted with some difficulty, being more familiar with the deck of a ship than the back of a horse, however quiet; and the troopers, faithful to discipline, refrained from smiling on seeing that their commander's face was solemn. Then Corporal Joe, having succeeded in rousing Stonewall, drove him forward with the butt-end of a carbine gently applied. Captain Barkham looked at the man rather doubtfully: he was undersized, as dirty and evil-looking as any of his fellows, and clad only in a loin-cloth. Perhaps he suffered by contrast with the trim policemen, in their uniforms of blue faced with red.

The lieutenant noticed the glance.

'Oh! don't judge the poor fellow by his looks,' he said, laughing. 'I daresay he's all right. All the same'—in a lower tone—'it may be wise to keep your hand on your revolver. They're curious cattle these half-wild beggars.'

'He knows his orders?'

The lieutenant repeated them to Stonewall, who nodded indifferently in response.

'And in case of accident,' the captain went on, 'I'm to head almost direct west, bearing latterly a little to the south?'

'Just a point.—Right?'

The captain seated himself squarely on his steed. 'Right!' he answered.

'Good-bye. Give my regards to Maitland and the boys.'

'Good-bye!'

Touching up his horse, he followed the guide, who looked neither to the right nor to the left, into the bush. The lieutenant watched them until they were out of sight, smiling a little at the rigid, awkward seat of the seaman: whereupon, emboldened by his example, the entire population showed its teeth in a general grin of amusement, and was happy.

For three hours or so Captain Barkham continued his journey through the bush without misadventure. Not an incident broke the monotony. The sky was without a cloud, but the heat was not oppressive to a man habituated to a tropical climate, and there was sufficient shade to make gratitude possible. The captain, being by nature unobservant, saw little of the beauty of the scene—trees festooned with vines, gorgeous orchids growing wild in the scrub, gigantic ferns of divers varieties, and here and there a little glade carpeted with the sweetest grass. Even to the parrots chattering in the tree-tops, or the groups of kangaroos and wallabies which fled at his approach, he paid little attention. He was thinking of his schooner lying in Cooktown harbour, and wishing with all his heart that his mission was successfully accomplished and he at sea again. For, truth to tell, the worthy captain was not at all comfortable in the saddle. Like most sailors, he was a timid rider, though, indeed, the horse was extremely docile; the route was of the roughest; and, above all, he was oppressed by a feeling of profound solitude. He had tried conversation with the black, but the result was not encouraging.

'Hey, Bingi—Stonewall—whatever you're called—how far now, eh?'

'Eh?—yup-yup—worru!'

'Hamilton, stoopid—how far?'

The black stared, wriggled his body, and politely returned the same answer.

'Don't you understand plain English, ebony-face? Here! Ham-il-ton'—pronouncing the words very slowly and distinctly—'Mister Maitland—how long to go yet? Three hours, eh?'

Stonewall rubbed his stomach reflectively. 'Yup—yup—bodgeree—wotsee?' he inquired.

'Then you don't understand English?'

'Yup—yup'—

The captain groaned. 'That will do,' he interrupted, and with sorrow gave up the attempt.

Grinning, the black went on. Paths and landmarks there were none—nothing but the flat, unending bush—but Stonewall found his way with the unerring instinct of his race. His movements were most erratic. Generally he kept well in front, throwing an occasional glance over his shoulder to see that his charge was safe. Sometimes he would stop to examine a gum-tree for fresh traces of the opossum, or with wonderful dexterity clear away the undergrowth in the horse's path with a few blows of his tomahawk: all in an agile manner pleasant to witness.

Captain Barkham's misfortunes began immediately after lunch, which was partaken of at noon by the side of a little spring. Although he shared with Stonewall the modest repast of sandwiches made up by his kind-hearted host of Baronga, the savage did not appear to be satisfied, for he resumed his search for a tender 'possum to eat as dessert. For a little, while he smoked a pipe, the captain lay on his back and watched him as he flitted from tree to tree and carefully inspected the trunks. At last he came upon one on which some of the scratches were fresher than others, and of the kind made by the animal when ascending rather than when descending—good evidence to the initiated that an opossum was concealed above. Half-turning, he shouted something.

'Eh? What's that? asked the captain.

'Potsum, missa! Sh!' he answered, and began to climb the tree.

The captain, no wiser than before, got up. As it happened, he was ready to go; and, being anxious to reach his destination, he saw no reason for putting off time while his guide, as he imagined, amused himself. So, having mounted, he halloed to the black to come down. Stonewall continued to ascend. He was twenty feet above the ground, and, whether he understood the captain or not, was evidently in no mind to give up his quest. Barkham repeated the order: Stonewall replied with some gibberish, but did not obey. For the captain, who was accustomed to prompt obedience, this was too much, especially from a naked savage. If words were ineffectual, he must try the effect of a threat. He drew his revolver.

'You've half a minute,' he said, pointing it at the fellow, 'and if you ain't down then'—a significant click ended the sentence.

Poor Stonewall may not have comprehended the speech, but the mere sight of the firearm was quite enough to drive all thoughts of the opossum, and much else, from his head. With a look of mortal dread on his countenance, he slid down the smooth trunk. The captain smiled to himself at the success of his ruse—and then, a moment later, the smile died away. For the black, apparently believing in the captain's sincerity, had no sooner touched ground than he had taken care to put the tree between him and the revolver, and was now to be seen making off into the bush. The threat had been just a little too effectual.

'Hey, there! Where on earth are you going?' cried Barkham.

Stonewall ran on.

'Here, come back! Come back, I say!'

'Here, come back! Come back, I say!'

Still the black ran on. Then, in desperation, the captain fired into the air. He hardly knew what he did, but assuredly it was the worst thing he could have done. Stonewall was already half-mad with terror: the report confirmed him in his suspicions, and completed the work begun by the sight of the pistol. In a minute he was out of view amongst the trees.

Gradually Barkham recovered, and faced the situation in which, through ignorance of native peculiarities, he had placed himself. Pursuit was hopeless. His guide had, beyond doubt, disappeared for good. And there he was in the heart of the bush, with only a general idea of the direction to his destination, and less notion of the distance. If he had not been a man of courage, with confidence in himself, he might well have been dismayed by the prospect. What he did was, mentally, to shake himself together. For, guide or no guide, there was no alternative but to go through with it, and that as speedily as possible.

His first step, after having come to this determination, was to shape his route by the aid of the sun, and set out towards the west. It was not long before he missed the help of his late companion, whose knowledge or instinct had led him to choose the more open parts of the bush. Being without either the knowledge or the instinct, the captain found himself plunging deeper and deeper into dense scrub, and that, too, when there was no tomahawk to clear a way for him. Progress was slow in the extreme, and became more difficult with every step; the feeling of solitude, heavy enough in the forenoon, burdened him now with tenfold force; and for the first hour the traveller needed all his doggedness and all his courage to keep his heart from sinking. Then there was a change—for the worse. The ground began to fall and the vegetation to vary, and quite suddenly the captain was made aware by the bogging of his horse that he had reached marshy ground.

'Guess I must get out of this,' he said to himself, as the animal floundered about.

It was no easy matter, however; and a wide circuit had to be made, and various small streams crossed, before dry ground was regained. Half an hour was spent in the effort, but it was to some advantage, for now there was less and thinner undergrowth.

The captain pulled rein to deliberate.

'Seems to me we're in a big mess, lad,' he confessed to the patient horse. 'Better have taken the road, forty miles and all, eh? As to what's to be done—But stop!' slapping his leg with vigour as an idea struck him. 'The very thing! Curious, now, I never thought of that before. Yes: I'll give you your head, my beauty; you should know the run of these parts better than me, and we'll see if we can't do without that blessed nigger after all. So on you go!'

For a time the plan seemed to work well. The horse, finding the reins loosened, walked on—leisurely, indeed, but apparently in the right direction. For the second time the captain congratulated himself on his idea, and for the second time somewhat prematurely. The animal jogged on just as far as it suited its own purposes. Coming at last to a little glade, it stopped to graze upon the sweet grass, and refused obedience to its master's gentle exhortations to proceed. From exhortations the captain fell back upon deeds, and—concerning the immediate sequel, and how it happened, he had afterwards the most hazy notion. But, somehow or other, he came to himself lying at the base of a giant eucalyptus, bruised and sore, while the steed was following the example of the errant Stonewall. When at length he managed to rise, it was nowhere to be seen.

At first Captain Barkham scarcely realised his position; he was more anxious regarding the extent of his injuries. Then, all at once, some idea of the truth burst upon him.

'Let us see,' he said aloud. 'Horse gone—nigger gone—no food—adrift in foreign parts without bearings or compass—the night coming on—worse and worse, by the Lord Harry! But it can't be far to Hamilton Gap now, surely. Stop! What if I've missed it?—West by south, was it?—Anyway, it's plain I can't stay here. Horse or no horse, nigger or no nigger, I must go on—till I drop.'

He was bruised on the side and shoulder, but the fact was forgotten in the greatness of his peril. Much as he realised, however, he did not realise all. He had heard many and gruesome stories of like adventures, which to a sailor had seemed to smack of exaggeration and want of verisimilitude; and even now, as he set his face to his journey, he was only beginning to have some idea of that which lay before him. Meanwhile, there was but the one thought in his mind: to go on and on. In the end he must reach Hamilton—or somewhere. So on and on he went, heeding nothing but the fact that he was covering ground and, as he imagined, drawing nearer and nearer to his destination. For two hours this continued. After the first, he failed to glance at the sun to see if he were going in the right direction; after the second, to notice whether the scrub underfoot was thick or the opposite. Gradually the feeling of fatigue mastered him, but there was no sign yet of any habitation. At last he was compelled to halt. He looked around him: the scene seemed familiar. The little glade—the great gum-tree at the foot of which he had fallen—neither admitted of any doubt. In a word: he was following his own track in a circle, and had returned to the spot from which he had started an hour ago!

He was bushed.

For five minutes he stood as if spell-bound, trying to understand it; and then, with a groan of despair, he threw himself upon the grass. So this was the end of all his exertions! Plainly, it was useless to continue the unequal struggle. He was both hungry and dead tired; and, to make matters worse—as if they were not bad enough already—his bruises began to smart most painfully.

Bushed! Again he called to memory the tales he had heard of men who had wandered into the bush, never to come back; of others who had lost their way, and strayed for days and days, living on roots and berries; even of some who had got out in the end, but only with the loss of reason. And more than ever he regretted the cabin of the Bird of Paradise, the little schooner which lay at that moment in the harbour of Cooktown, unloading her cargo of shells and copra. Should he ever see her again? To his mind, the chances were against it; but if he did, he was ready to make a vow that this first parting from her on a long journey into the interior should be the last. But the chances were indeed against it. Even the parrots, mocking him from their posts in the tree-tops, could have told him that.

Thus one thought chased another through Captain Barkham's head as he lay, and all of them were black. It was while they were blackest that he heard a familiar sound, coming apparently from no great distance, and incontinently jumped to his feet with every sign of being mad save that he listened intently. Again it came—a gun-shot, followed by a long, piercing cry which there was no mistaking.

'Coo—ey! Coo—oo—ey!'

The captain, scarcely daring to credit his good fortune, drew his breath hard before he gave back the shout: 'Coo—ey! Coo—ey!'

There was an interval of a minute: it seemed an hour to the impatient listener. Then he was answered.

ON the morning of the same day, while Captain Barkham was following Stonewall into the bush, Frank Dennison was hammering at the door of his brother's room in the homestead of Hamilton Gap with all the impetuous eagerness of his fifteen years. His brown, handsome face was flushed with the exercise; there was a mischievous look in his eyes; and, being full of important news which he was burning to impart, he spared neither knuckles nor feet in the attempt to gain entry. But the door remained locked, and at length Frank was forced to use his voice.

'Walt!'

There was no answer.

'Walter!'

Still no answer.

'Open the door, Walter! I've a message for you.'

This drew forth a response. 'What is it? Out with it!'

'Open the door, first.' Persuasively: 'It's too important to be shouted through the keyhole—really it is. Honour bright, Walt!'

Walter took no notice: it was for the purpose of avoiding the intrusion of his brother that, having work to do, he had locked the door. After a short interval the play of boot and knuckles began again. He bore it for five minutes.

'You may as well go away, young 'un,' he said, losing patience at last. 'You needn't try to get in—I can't go out with you this morning.'

'It isn't that. I met Brunton, and he says he has told Mr Maitland about last night.'

'If that's all'—

'It isn't. Mr Maitland wants to see you.'

'Oh!' There was a change in Walter's tone. 'Where is he?'

'In the veranda.'

'Tell him I'll be there in a minute. And don't be afraid, Frank; it's only another row, I'll be bound. Now be off, and let me get my work done.'

'How long will you be? Jimmy says he saw an emu not an hour ago.'

How, as it happened, the emu (or Australian ostrich) was rarely seen in the vicinity of Hamilton, and Walter had long wished to shoot one. He perceived the pitfall, and avoided it.

'Can't be helped!'

'But you know you've always wanted to see one,' insisted Frank.

'It must wait. Be off, or'—

He had no need to finish his sentence. Frank knew—none better—the capacity of his brother's patience, and thought it wise to obey. He went off whistling.

Walter leaned back in his chair to think. In personal appearance he was very like Frank; he had the same tangle of hair, the same blue eyes, the same mischief-loving twinkle; but he was taller and more firmly knit, and at times—but only at times—he had a graver demeanour. Between the two, so near in age, and brought up side by side far from other companionship, there was the closest bond of union. As Mr Maitland was wont to put it, smiling in his quiet way, they were always in hot water together. It was of one of these scrapes that Walter was now thinking, not without perturbation. Brunton had seen Mr Maitland—he knew the meaning of that. Mr Maitland wished to see him—he could guess the meaning of that. At the utmost it meant a lecture; but a lecture from their guardian was perhaps that of all things most dreaded by the boys.

'Best to have it over as soon as possible,' he said to himself, philosophically. 'But first I must get these beastly sums done. Here goes!'

With that he bent over the accounts he was comparing for Mr Maitland, and in the course of twenty minutes had finished the work. Then, gathering up the papers, he went forth to meet his doom.

He found Mr Maitland in his usual place in the veranda. Every morning after breakfast the chair was wheeled thither, and there the settler received his subordinates, issued his orders, and exercised his rule over the whole station. A mighty change had taken place during the five years which have elapsed since the outbreak of the blacks and Mr Dennison's departure. The homestead, larger itself, was now surrounded on three sides by a garden, while the outhouses and sheep-pens had been removed beyond the fringe of trees, towards the base of the hills. There Brunton, the oversman, had his house. But it was on the low-lying ground on both banks of the river that there was the greatest change. Instead of pasturage, you now saw vast plantations of the sugar-cane; the site of the old homestead was occupied by the manufactory; and the place of the blackboy had been taken by the gentler and more industrious labourer from Polynesia. For Mr Maitland had been quick to recognise the suitability of the land for sugar-growing, and one of the first to take advantage of the importation of Kanaka labour. The conversion of his own run was now complete; but under Brunton the Dennison run, which had been extended into the hills, was still devoted to the raising of sheep and cattle.

All this, of course, had happened while the boys were too young to bear a share of the work. Notwithstanding, Mr Maitland had found time to educate them and little Ruth—and to educate them well, as they were to discover in after years. Only from books had they any idea of the great world on the other side of the equator; and Walter, alone of the three, gave a passing thought of wonder that a man like his tutor should bury himself so far from his fellows, with no companion except his Shakespeare, and no communication except an occasional business letter from Sydney or Cooktown.

This morning he was bending over his writing-table, which was littered with papers. He looked up as Walter approached. 'Are they all right?' he asked.

'I think so, sir.'

'Thanks.' He signed to the boy to sit down. 'And what is this complaint of you I hear from Brunton, Walter?' he went on.

Walter, feeling that his hour was come, plunged into his justification. 'I'm very sorry, sir, but really it was too good a chance'—

'What was?' inquired his guardian, interrupting. 'You forget that I don't know the story.'

'Oh! I thought Brunton had told you. Well, it was in this way. Frank and I were passing Brunton's house last night on the way home from the hills—we were getting those specimens you wanted, you remember—and chanced to look in. You know Brunton's hammock, sir? It hangs in the veranda, pretty low down. Well, Brunton was lying in it asleep, and near at hand was his bath-tub full of water.' He broke off, and looked into Mr Maitland's face. 'Now, what would you have done, sir?' he asked innocently.

Mr Maitland smiled. 'I can guess what you did, at any rate,' he said.

'We couldn't resist it, sir. And he had no business having the tub there if he didn't want people to use it. So we quietly drew it under the head of the hammock, and untied the head-ropes. Then we let the thing down gently till Brunton's head was within a foot of the water, when'—He stopped again, as the memory of the prank proved too much for his gravity.

'Yes—when?'

'That was all. We let go, and hid ourselves under the veranda.'

'And what happened?'

'We heard a splash, and then Brunton got up and began to swear fearfully. Oh! it was an awful row, sir. This went on for a while, and after a bit we crept round to the corner of the house, and Frank shouted to him not to lose his temper. Then we bolted. But you would have laughed yourself to see him staring after us, with the water dripping from his beard, and not a word to say!—and,' he concluded, remembering his cue, 'I'm very sorry, sir.'

'Well, you must settle the matter with Brunton as best you can,' said Mr Maitland; and, much to Walter's relief, he did not seem very angry. 'I've given him full powers, and advised him not to be sparing in the use of them. But really, Walter'—laying his hand affectionately on the boy's shoulder—'isn't it about time you were thinking of giving up these tricks? You're almost a man, remember.'

'I'll try, sir,' replied Walter, penitently. It was not the first time he had promised the same thing.

'And speak to Frank—I'm afraid he's as bad as you.—But it wasn't that I wanted to talk to you about, Walter,' continued Mr Maitland, with a change of tone. 'The fact is, I have a letter here which should interest you. I got it this morning.'

'A letter, sir?'

'Yes. Where did I put it? Ah! here it is. It is from Her Majesty's Commissioner in New Guinea, in answer to one I wrote him a month or two ago.'

'About—about my father?' Walter was serious enough now, for this was the one subject which was never long absent from his thoughts. Ever since they received Mr Dennison's last letter, three years before, there had been anxiety, and always anxiety, at Hamilton Gap in regard to him. Walter himself was too young to take other than a hopeful view; but as for his tutor, little as he cared to disturb the boy's peace of mind, he had not (latterly, at least) been altogether able to conceal his misgivings.

'About your father,' he answered gravely. 'You remember our last talk, when you proposed to go in search of him?' Well, I wrote the very next day, for with you I thought it time that some inquiries were made. And this is the reply.'

Walter waited in suspense while he opened out and read the letter again.

'Is it good?' he could not refrain from asking.

'N-no. I can't say it is, Walter. Put shortly, it says that nothing whatever has been heard of your father—good or bad. One of the Deputy-commissioners had lately been at the village he started from three years ago, but at that time nothing was known of him. Mr Douglas adds that probably he or the Deputy will pay a second visit to the place in the course of a few months, when he promises to make full inquiry and let me know. Until then, Walter,' he said, folding up the letter, 'I fear we can do nothing.'

'Is that all, sir?' asked Walter. 'May I see the letter?'

Mr Maitland hesitated for a moment, and then handed it to him. 'There is only an expression of the Commissioner's opinion,' he said. 'Perhaps, after all, you had better read it for yourself.'

Walter did so. His guardian had given him the sense of the contents—with the exception of the last sentence, in which the writer expressed the fear that, considering the duration of Mr Dennison's absence, and the want even of rumours regarding him, he had fallen a victim either to the climate or to the enmity of hostile tribes in the interior. Walter became thoughtful.

'Well?' inquired Mr Maitland.

'I don't believe it, sir!' he cried.

'And what grounds have you for putting up your opinion against Her Majesty's Commissioner's, pray?'

'Somehow, I feel he's not dead—he can't be! So many other things may have happened to him, you know.'

'For instance?'

'Oh! he may be a prisoner, or be lying wounded or ill somewhere up country. Anyway, sir, I think we should try to make sure!'

Mr Maitland smiled at the boy's vehemence. 'That is, go in search of him, I suppose? And how do you propose to do it? New Guinea isn't one of the Fiji Islands, remember. In size it is almost a continent, and more unknown than the heart of Africa.'

'I know all that, sir. But where there's a will there's a way, and with your help,' he said, confidently, 'I'm sure we could find one.'

Here the conversation was interrupted by the sudden appearance in the paddock in front of the house of a horse at full gallop, bearing upon its back both Frank and Mr Maitland's little daughter. Her father did not fail to notice that Ruth, who was seated behind the boy, was holding him very securely by the waist, and to be somewhat amused thereat; nor could Walter, on his part, repress a start of amazement when presently he recognised the animal by head-mark.

'Surely there's a scarcity of horses somewhere,' remarked Mr Maitland, suspecting nothing, 'or perhaps it's only another of Master Frank's experiments.—As to what you say, Walter, I don't know that you're altogether wrong. But if you care to abide by my advice—

'You know I will, sir!' cried Walter.

'In that case, I think we should wait until the Commissioner has made the inquiry he promises.'

'And then?'

'Then we can discuss the matter with some certainty. At present, we can't. But here are the scapegraces—no more just now. I leave you to tell Frank as much of this as you please.'

By this time the horse had been pulled up in front of the veranda, and Walter ran down to help Ruth to alight. That done, Frank rode off on the animal to the stables, while his companion kissed her father and nestled down beside his chair. She was a pretty, golden-haired, happy-faced little maid of fourteen, and to-day there was an unwontedly serious look in her blue eyes as she raised them to Mr Maitland's face.

'Well, what is it, Miss Mazeppa?' he demanded, pinching her ear. 'Eager for school-time, eh?'

'Not to-day, papa,' she replied.

'Indeed! And why not?'

'Frank wants a holiday—for Walter and him. You know Jimmy saw some emus in the bush this morning, and Frank has promised to get me some feathers.' Coaxingly: 'You'll let him off for to-day, won't you?

'That's it, is it? And why can't Master Frank present his petitions in person?'

'Oh!'cause he's afraid you would refuse. He's been doing something naughty again, he says, and so he didn't like to ask.'

'He didn't like? So! And what do you say to this audacious proposal, Walter?'

'I should like nothing better, sir.'

'Then I suppose I must give in. But here comes the timorous wrong-doer to plead his own cause'—this as Frank strolled up, trying to look unconcerned. To him: 'So you think, sir, you deserve a holiday?'

Frank shook his head rather doubtfully.

'No? Then why ask one, pray?'

'It's all those emus, sir,' answered the boy. 'We mayn't have another chance for months, and'—ingenuously—'it would be a pity if Ruth was cheated out of her feathers through no fault of hers, wouldn't it? Besides, it's such a long time since we had a holiday.'

'I daresay it is—not for a fortnight at least, I should say,' retorted Mr Maitland. 'However, we must not rob Ruth of her feathers. In return, perhaps she'll make up some lunch for you. There—no thanks! And one word, Walter. Be careful of the guns, and don't go too far. You'll take Jimmy, of course? Now, away with you all, and leave me to get my work done, so that Ruth and I may have a long afternoon's reading.'

The young people went off together, but before they separated—Walter to get the guns, Frank and Ruth to see about the lunch—something seemed to strike the former.

'By the bye, does anybody know where Jimmy is?' he asked. 'I haven't seen him to-day.'

'Oh! I know,' said Frank.

Walter, reassured, disappeared into the house.

Within ten minutes thereafter everything was ready; and the two, their guns in hand and their bags over their shoulders, set out on their expedition. As soon as they were beyond earshot of the veranda, Walter turned upon his brother with a sudden question.

'Now, young 'un, I should like to know where you got that horse of Brunton's?' he demanded.

Frank looked at him with an expression of some anxiety. 'I hope Mr Maitland didn't know the beast, Walt,' he said. 'I thought you would.'

'Of course he didn't, or we shouldn't be here. But what have you been up to?'

Frank began to laugh, and laughed uproariously until his brother brought him to his senses by a punch in the ribs. Then he condescended to explain.

'It was Brunton's own fault. Why! you should have seen his face when I went off! I was down by the Long Plantation, and he was riding home for breakfast. After last night I didn't want to see him particularly, but he spotted me first, and headed me off before I had run fifty yards. Then I stopped—it was no use doing anything else—and said "Good-morning" quite politely. But I can tell you I was shaking, for I saw by his face that he meant mischief. Well, he got off the horse, and threw the reins over a stump. Says he, "You mayn't be aware, young man, that I have full powers from the boss?" I pretended not to understand, and asked as to what. "To settle accounts with you and the like o' you," he said, "and, what's more, I've one to settle now for last night!" Says I, "Oh! don't mention it, please; I only hoped you liked your bath!"'

'Which was cheeky,' remarked Walter.

'I couldn't help it, really. Then says he, "About as much as you'll like what you're about to get, young man," and I saw him hunting about along the edge of the plantation for something—a good stick, probably. Well, I had no fancy to be thrashed, and it was just then that the idea came into my head. I was nearer the horse than he was, and a second would do it. There was no time to think'—

'And of course you didn't?'

'No,' confessed Frank. 'Before he could stop me, I had the reins in my hand and was on the horse's back. He was about eight yards off, and I had just time to turn round, remind him that the account would have to be settled again, and say good-morning as politely as before. I left him staring—worse than last night, too. After that, I had the jolliest gallop down to the house, picking up Ruth by the way; and, thinking that it might be as well to be out of sight if Brunton took it into his head to follow on foot, I put her up to ask a holiday to go after the emus. I hadn't much fear.'

'All very well,' said Walter, grimly, 'but didn't it occur to you that it would be the worse in the long-run? Strikes me you're in a nice scrape, youngster.'

Frank admitted the truth of this, but seemed inclined to trust to his luck.

'And what about the horse? Walter went on. 'Did you leave it in the stables?'

'I wasn't such a fool. I got hold of Jimmy, and sent him up to Brunton's with it and a message that I hoped he had liked his walk. I calculated that the blackboy would catch him at breakfast.'

'Worse and worse!' groaned the elder.

'As well be hanged for a sheep at once!' calmly answered the younger. 'As to Jimmy, I told him to meet us at the bridge—very likely he's there now. I was sure of the holiday, you see. But say, Walter,' he cried, laughing gleefully, 'didn't it serve old Brunton right? The beggar hates to walk!'

Walter laughed too; and then, remembering his guardian's words, he shook his head sadly. There might be some hope for him, but his brother was incorrigible.

JIMMY was at the rendezvous. As we know from Frank, the blackboy had been ordered to repair to the wooden bridge which Mr Maitland had lately thrown across the river to facilitate communication with the manufactory. The way thither lay through the plantations of sugar-cane, and here and there the boys passed a group of brown-skinned Kanakas, dreaming as they wrought of their homes in some isle of the New Hebrides, and hearing even in the heart of Australia the Pacific surf breaking upon the coral. For a moment they roused themselves to answer the cheerful salutations of the Dennison lads, who, on the strength of a few words of their language and the memory of an occasional kindness, were huge favourites of theirs—and this not the less because themselves were the only folks around Hamilton free from the boys' pranks.

From the broad grin on Jimmy's face, it was evident that he had a story to tell.

'Well, Jimmy, did Mr Brunton say anything?' asked Frank.

The grin broadened. 'Yohi, Missa Flank,' he made reply. 'Him at bleakfass, and fust he chuck plate. Head too much hard—plate it breakum, and he swear. Then Missa Bluntum me call black scoun'rel, and he say, "Missa Flank him tell look out—he catch it hot, no gammon!" Me laugh, and he chuck more plate. That all.'

'But the plate didn't hit you, did it?'

Jimmy nodded.

'Oh! it did. Does it hurt?'

'No hurt, missa, but plate it breakum,' proudly answered the blackboy.

'In that case,' said Walter, laughing, 'you'd better take the bags and let us get on after the emus. How long should we be in making up on them?

Jimmy wasn't sure: they might not have strayed far, or they might be twenty miles away by that time. But the latter was the more probable, and so the black shouldered the lunch-bags with great good-will and set off, being fully as eager for a holiday as his young masters.

Ten minutes' walk took them across the cultivated patch to the border of the bush, and twenty minutes more to the spot whence the emus had been sighted in the early morning. For the next few hours they followed the track of the birds. Frank, eager to learn the secrets of woodcraft, kept for the most part by the side of the black, and the voluble chatter between the two never ceased. For, although each spoke in his own dialect, Jimmy had apparently as little difficulty in understanding the colloquialisms of the boy as the boy had in understanding his broken English. Walter held behind, but his thoughts, engrossing as they were, were not too engrossing to permit him to listen to the guide's explanations of what a broken twig here, and a feather there, might mean, or to admire the keen eyesight and unfailing instinct of the bushman. Jimmy in a state of nature was a different man from Jimmy in the process of being civilised.

Thus for a time they proceeded, in the interest of the chase giving little heed to the heat of the day, and making light of the incidental obstacles in their path. Once or twice a good shot at a kangaroo offered, but the boys refrained from shooting. About two hours after noon, they reached a dell where there was a spring of fresh water: an ideal spot for luncheon. So Walter called a halt, notwithstanding the fact that, according to Jimmy, the emu-tracks were so fresh that the birds could not be far in advance; but it was not the first time he had said so. The boys had their cold mutton and damper; and for behoof of the blackboy, who disdained such luxuries, a parrot was shot, which he ate after a mere pretence of cooking it.

The repast over, Frank proposed to hurry on. Walter, however, had been thinking, and demurred.

'But, look here, we'll lose the emus if we don't,' his brother pointed out.

'Go you and Jimmy, then—I don't feel inclined,' answered Walter, in whose mind the emus had altogether given place to New Guinea. He wished to think out what Mr Maitland had told him, and, boylike, to think it out alone.

'You're not tired, are you?'

'No; but I don't feel inclined,' repeated Walter, in the same tone.

Frank did not press him further, aware from his knowledge of his elder brother's nature that it would be useless. 'I'm going, anyway,' he said. 'I must get those feathers for Ruth, you know.'

'Of course. And blaze the trees as you go along, mind. I'll either follow, or you can pick me up on your way back. Don't go too far, though.'

'No fear of that—eh, Jimmy?'

'No fear, my word! Emu plenty near now—me smellum close up, Missa Flank. All right?'

They disappeared, and Walter was left to his thoughts and day-dreams. He lay on his back by the water-side, looking at the patchwork of sky seen through the foliage of the trees, and wondered if his father were dead after all, or if his own belief were in truth the right one. He tried to conjure up a picture of a Papuan village in the mountains of the interior—the mud hovels, the savage, man-eating natives, and, above all, the white man living amongst them, held sacred as a god perhaps, or perhaps kept close prisoner because of his medical skill. Then he saw himself setting forth in search of him, and followed in his mind's eye the weary marches from village to village, the hairbreadth adventures, the disappointments and hopes until finally he was successful. For years Walter had read everything about New Guinea that he could find, and he was not without imagination; but not in his wildest flights of fancy did he dream of perils such as those he was to undergo before he was many months older, just as little as he dreamed that at that moment, within a few miles of him, was the man who would be the immediate cause of his dearest expectations being realised.

This for about an hour; and then Walter's attention strayed somewhat, and presently he bethought him of the emus. He remembered that he had always desired to shoot one, and was wilfully throwing away the chance. Even yet, if he walked fast, it might not be too late to be in at the finish. Refreshed by the rest, he pushed on at a goodly speed, and found no difficulty in following the track of his companions, marked out as it was by Jimmy's hatchet on the bark of the trees. But the afternoon was sultry, and when he had covered two or three miles he began to feel the weight of his gun a burden.

'Surely they can't be far now,' he said to himself, forgetting that they had an hour's start. 'I wonder if they're within earshot? Guess it can't do any harm to find out, any way.'

The signal of the boys, arranged in view of excursions like the present, was two shots fired at an interval of a minute, and then a long 'cooey.' Walter gave it, and waited for a response. It came, but sooner than he expected, and in a different manner. It was a single cry, distinct enough to show that it was from the near vicinity, and, strangest of all, in the voice neither of Frank nor of the blackboy. By the intonation, indeed, it was evidently from somebody not a bushman.

Walter was too much surprised to conjecture what it might mean, for promiscuous visitors to Hamilton Gap were quite unknown. One thing was plain: he must get to the bottom of the mystery.

He shouted again:

'Cooey! Coo—ey! Coo—oo—ey!'

Again the cry was repeated, and Walter took note of the direction. Then he went forward, calling loudly, and being guided by the answering shouts of the stranger. In five minutes he was at the verge of the glade, and the cries sounded quite near; the next moment, breaking cover, he found himself in the strenuous embrace of Captain Barkham!

When at length the boy managed to free himself from the grip of the overjoyed sailor, he saw before him a man rather beyond middle age, squat and square-shouldered, with a broad, honest countenance, burnt brown by the sun, and a pair of shrewd eyes. Just now there was a look of the utmost delight in them, as if their owner was congratulating himself on his escape from a great danger. His dress was a compromise between sea-garb and the conventional dress of cities; he wore heavy sea-boots; his broad-brimmed felt hat lay on the ground a short distance off; and there were not wanting indications that his journey through the bush had not been devoid of incident and mishap.

The two regarded each other for a minute without speaking, and then a shade of doubt flitted across the worthy skipper's face. He gripped Walter again.

'Here! You don't mean to say you're lost too, do you?' he demanded eagerly.

'Lost? Not likely!' replied Walter, with some contempt. 'Why, I know the bush round here like the palm of my hand!'

The captain breathed a sigh of relief. 'You belong to these parts, then?'

'Rather!' Tentatively: 'You're a stranger hereabouts?'

'I wish I wasn't!' cried Barkham, the memory of his sufferings being still fresh. 'It's the first time I've seen the place, and I'd give a lot if 'twas the last. I slept at Baronga last night, and left it this morning'—

'Not as you are, surely?' interrupted Walter. 'Not on foot, I mean.'

'Not exactly—I guess I had a nigger and a horse when I started. The nigger was the first to go, just about noon observation. Then the horse threw me off, and went too. Since then I've been wandering about on the look-out for a house called Hamilton Gap, and very glad I am,' he said, with another cordial handshake, 'to see somebody who's likely to know the road. How far might it happen to be, now?

Walter gave a gasp. 'Hamilton Gap! Why, that's our house!' he exclaimed.

'Your house? Then'—

He got no further, and for the next few minutes was left to his own reflections. While he was speaking, Walter had heard a shot. How there was another and a 'cooey,' and the boy, rapidly reloading, replied to the signal.

'That's my brother Frank,' he explained to the captain. 'He must have heard the last signal as well as you. We're out after emus, you know.—Coo—ey!'

'Oh? that's it, is it?' said Barkham to himself, and a twinkle came into his eyes.

'He has a blackboy with him,' Walter went on, after some more shouting. 'I wonder if they've shot anything?—Coo—ey!—We might go and meet them, if you don't mind. It's on our way.'

The captain picked up his hat and followed, still nodding to himself as if well pleased. The responsive calls became louder and louder: the two parties were quickly approaching each other. When at last they came within sight, Walter was amazed to observe that his brother was riding a horse, while Jimmy—grinning as usual—brought up the rear. Walter, quite forgetting the stranger in his surprise, broke into a run.

'Hullo! where did you get the nag, Frank?' he cried, coming up.

'That's my emu—whoop!' replied Frank.

'Your emu?'

'All we got, anyway. We tracked 'em until Jimmy saw by their footmarks that they had made a big spurt, and it was no use going on. Something must have frightened them. Coming back, we sighted this animal grazing peacefully in our path, and easily caught him—saddle and bridle and all! Wonder who he belongs to?'

The captain stepped forward.

'The horse is mine, Mister Dennison!' he said. 'Thanks for catching him!'

'Yours?' Frank looked at the stranger, and there was a world of unaffected amazement and perplexity expressed in the one word. Then he dismounted.

Walter was likewise perplexed. 'Say, how did you know our names?' he demanded.

'Let me see—I shouldn't wonder if you were Mister Walter, now?' said Barkham, ignoring the question.

Walter admitted it.

'And you—you're Mister Frank, of course?'

Frank nodded.

'As for this gentleman'—indicating Jimmy, who was still grinning—'I don't know him, but it strikes me he bears a remarkable family likeness to my runaway nigger.'

'Oh! Jimmy's all right,' Walter hastened to assure him. 'He's our confidential servant. But how'—

The captain, having enjoyed his laugh at the boys' surprise, was ready to explain. 'How? Partly by guess-work,' he said—'partly from an old description of you. Besides, haven't I got a letter for you in my pouch?'

Now the Dennison boys were not in the habit of receiving letters, and consequently they became more excited than ever.

'A letter!' cried Walter,

'For us!' cried Frank.

Both held out their hands for it.

'Slowly!' said Barkham. 'It's for you, right enough—I saw it written—but as it happens to be enclosed in one to Mr Maitland, I reckon you'll have to wait until we get to Hamilton Gap.'

Here a strange idea came into Walter's head.

'Is it—is it from New Guinea?' he asked, eager to know, yet half-hesitating to inquire.

'You've guessed it, boy! It is from New Guinea; straight from the land of the Golden Plume, as they call it. And that reminds me,' the captain went on, 'that I should have introduced myself long ago as James Barkham, master of the Bird of Paradise, at present lying in Cooktown harbour after a voyage to the Louisiade Islands and New Guinea. It was there, in New Guinea'—this in the most matter-of-fact tone—'that I ran across your father, and took up this commission. He's an old friend of mine, you know.—But what in the name o' creation's the matter?'

It was now the boys' turn to be demonstrative. To Walter, and in a less degree to his brother, the good news of their father's safety was so utterly unexpected that for a little they were speechless: they could only catch hold of the captain's hands—Frank the right, Walter the left—and shake them, as the former would have put it, for all they were worth. Barkham endured it with great good-humour for a minute or two, and then called a truce.

'Then he is alive?' said Walter. Having recovered his voice, he was eager for confirmation.

'As much alive as I am—more, maybe,' replied the captain, gently rubbing his bruised side. 'Or at least he was six weeks ago, when I saw him last.'

This was satisfactory, but when Frank had given utterance to a wild whoop of delight, Walter—who had still the Commissioner's letter on his mind—had another question to ask. He did it gravely:

'And well?'

'And well—barring a slight limp, caused by putting his foot into a trap. I did the same myself once.'

'Why doesn't he come back, then?' demanded Frank.

'If it isn't in the letter, I daresay I can give you a good reason for it, Mister Frank,' said Barkham. 'As it is, better wait for the letter. Which reminds me,' he went on, 'that I don't know yet how far it is to Hamilton Gap, and that I'm getting peckish. We may as well tramp, I think.'

Needless to say, there was no opposition to the suggestion, for the boys were now as eager to reach Hamilton Gap as he was. They started at once, he on the horse, they on either side, and Jimmy as guide to strike out the nearest path. On the road he answered as best he could their numberless inquiries about Mr Dennison, or entertained them with a full and vivid account of his misadventures after leaving Baronga; and he had also a question or two to put by way of satisfying his own curiosity. For instance, with a glance at the guns:

'You are good at the shooting, I suppose?' he surmised.

Walter admitted that they were pretty fair, while Frank seized advantage of the first opportunity to prove his ability by bringing down a bird on the wing. Said the captain, as he applauded the shot:

'And is your brother as good, Mister Frank?'

'Better,' returned Frank, loyally: which was the case.

Barkham seemed gratified.

In this way was the journey lightened; and by the time they issued from the bush, an hour or two before sundown, they were all the best of friends. Here Frank was sent forward to prepare his guardian. You may be sure he fulfilled the duty with breathless vehemence and with many gesticulations.

Mr Maitland was in his chair in the veranda when they arrived, ready to offer the new-comer a hearty greeting.

'You'll excuse me for not rising, sir,' he said. 'But you're welcome to Hamilton, and twice welcome that you bring good news. Now, not a word until you've had a wash and some dinner! It's a custom here.—Walter, take Mr Barkham to your room.'

DINNER being over, the seniors lit their cigars, little Ruth squatted down in her favourite position beside her father's chair, and the boys set themselves to listen with all their ears to Captain Barkham's story.

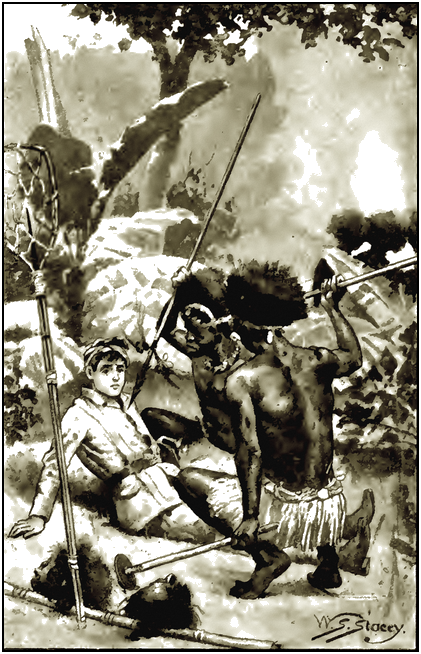

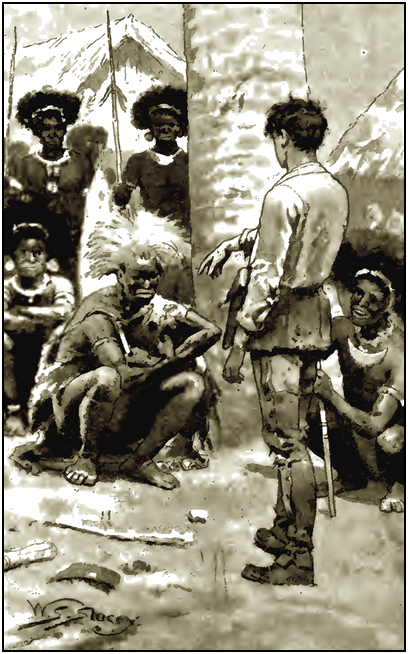

'It was in this way that I met Mr Dennison first,' he began. 'Somewhere about three years ago I was chartered at Sydney by a man of the name of Lambert to run my schooner—the Bird of Paradise she's called—to run her to an out-of-the-way village at the head of the Gulf of Papua. I had never heard of the place myself, although I've sailed those seas for twenty years and more, but Lambert had the bearings, and seemed to know what he was about. He was very close about his plans, but they were plain enough, for he had any amount of exploring stuff and such like on board. Well, we arrived at the village in due course. Mr Dennison and another man—he's dead since, poor fellow—were waiting for Lambert there, keeping friendly with the natives. From what I saw I gathered that they were bound on a long trip into the interior in search of gold; and, as it happened, I saw a good deal of them, for we were detained for nearly a week by contrary winds. On the second or third day, I had a sort of an adventure. Somehow or other, I managed to put up the back of one of the savages—and it's easily enough done if you haven't the lay of their customs, and ain't careful—and as a consequence he came at me with his club. We had a bit of a tussle, and he got rather the best of it, not being hampered by clothes. Indeed, to tell the truth, he was just in the act of bringing down the club on my head when Dennison turned up and caught his arm—in the very nick of time. He cooled down then, and a paltry present squared him. But I was none the less grateful to Dennison, and then and there I made him a promise that I should look in at the place for news of him whenever I chanced to be in the latitude. That,' said the captain, 'was one point to him.'

His cigar had gone out, and he lit it afresh and continued:

'Well, I didn't forget my promise. Twice, at pretty long intervals, I called in; but he hadn't returned, and I could get no news of the party whatever. The visits had this good result, though—I did some trade with the natives, and so kept up the friendship for white men which they had had ever since Dennison's arrival. The third time I was more lucky. It was six or seven weeks ago, when, being on that coast, I thought that I would pay the place another visit. Not that I expected to find your friend, mark you—it was merely for curiosity's sake, and maybe to do a bit of trade. Well, judge of my surprise to see, the first thing after our anchor was down, a native boat put off with a white man in the stem! I must say I didn't recognise him at first, for his clothes were rather promiscuous, and he was bearded like an up-country digger. Then I heard a hail:

"Ahoy! Is that you, Barkham?"

"Not Dennison, bless my heart!" I cried, thinking I knew the voice.

'But it was Dennison—well and hearty, too, barring a sprained ankle. You may be sure we were delighted to see each other again. He had been there a month, having just missed one of the Commissioner-fellows by a week or two, and as he couldn't leave the place, my arrival was like a Godsend to him. Shortly told, his story was that for more than a couple of years he and his chums had been staying with a tribe up-country, who had such a high opinion of them that at first they wouldn't let them go at all, and afterwards not until they had promised to come back. More than that—but this was between ourselves—they had struck gold. Finally they got away on the promise aforesaid, which was just what they meant to do—of their own accord. On the road to the coast, however, they had managed to lose most of their things, and one of the three had died as well. As for the other man—Lambert—he was at that moment lying at death's door with swamp-fever, and Dennison was doubtful of pulling him through. And this was the pass he was in when I turned up; there were no means of leaving the country at that point, and even if there had been, he couldn't have done so because of Lambert. As to sending a letter to the Commissioner at Port Moresby, even putting out of sight the objection to that on the ground of policy, it would have been almost impossible to do it in the native boats. Not that he hadn't seriously thought of trying; indeed, the letter was written, enclosing one to be sent to you. By good luck, I arrived just in time to save him the trouble—one point to me. Of course, the first thing I did was to offer him a passage to Australia. But Lambert couldn't be moved; still less could he be left in the care of the natives; and as, owing to the nature of my cargo, I couldn't stay until there was a change for the better or the worse, there was nothing for it but to leave Dennison in Papua and be his messenger here. And this was his commission, Mr Maitland,' concluded the captain, producing from the depths of a capacious pocket a small but heavy parcel—'first, to bring this packet to you, which I've done; second, to carry out certain instructions under your orders; and last, to get back to New Guinea with as much speed as might be.'

'And I'm sure you deserve our best thanks, Captain Barkham,' said Mr Maitland, as he took the packet and rapidly tore off the cover. The boys watched him with eager eyes. Inside were two letters and another little parcel. Of the former, one was addressed to himself, the other to Walter and Frank. The parcel, as being of minor importance, was put aside for future examination.

'Oh! not at all,' said Barkham, in answer to Mr Maitland. 'Why, bless my heart! I had a score to settle, and I'd do the same again for a friend like Dennison—barring the trip through the bush,' he added. 'Next time I'd take the road.'