RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

"The Mountain Kingdom," Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1891 edition

"The Mountain Kingdom," Title Page

Frontispiece.

"In an instant my revolver was out, I had covered my man,

and the next moment he fell, shot through the brain."

MY experience in the literary way has been so small that it was only after great persuasion that I was induced to commence this history. Being conscious of my shortcomings, I wished to hand over the task to some one more capable of doing it justice; and it was not until my friends, the Hon. Eric Trevanion and Mr. Francis Lee, of Nepaul, had used considerable pressure that I gave in to them. They said that as I had been leader it was my duty to give an account of our marvellous adventures to the world, and no one else had any right to do it. So, in the end, I consented, though it was with much reluctance.

Before beginning, however, it may be necessary for me to remind the reader that there is an ancient proverb to the effect that "Truth is stranger than fiction." Otherwise, he or she may be apt to forget that this is a true narrative, and not the creation of an imaginative novelist's brain. The incidents I intend to relate, especially in the latter half of this volume (always provided, of course, that I do not throw up the whole thing in disgust by that time) may appear, to say the least of it, strange and uncommon, as, indeed, they appeared to us ourselves at the time; but it is known, on the authority of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark,

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

Strange things we saw, and strange things we did, as shall be

related in their proper places—things of which, in our

philosophy, we never at one time even dreamt. But we are wiser

now, thanks to the expedition above referred to; and I hope that

my readers, before they finish all that I mean to write, may be

in the same condition.

Well, making the best of an uncongenial job—for, even at college, I was more at home with a bat or an oar than a pen—I suppose I shall have to begin at the beginning. Know, then, that on a certain spring morning in the year of grace 187—, I, Douglas Dalziel of Airth, Esquire, was in my twenty-fourth year. Airth, which, as every one knows, is in Inverness-shire, N.B., had passed into my possession on attaining my majority, my father having died nine years previously. He had had one younger brother, who, all through my boyhood and youth, was a mystery to me. For a long time all that I knew of him was that he had died or been killed somewhere abroad; that his loss had been so acutely felt by my parents that they could hardly bear to hear his name mentioned; and that a monument had been erected to his memory in the family burying-place, the inscription on which ran:

ALISTER DOUGLAS DALZIEL.

Born, 1825. Died, 1851.

"He, the young and strong, who cherished

Noble longings for the strife,

By the roadside fell and perished.

Weary with the march of life."

Often in my boyhood, while my father was still alive, have I

stood by this monument, musing on my uncle's probable fate, and

wishing I could know more of one whom I placed alongside of

Richard Coeur de Lion, Ivanhoe, the Knight of the Leopard, and my

other favourite heroes of chivalry.

One day, when I was about twelve, I summoned up courage to ask my father concerning him. I don't know why I had not done so before, unless it was that intuitively I had felt that it was a subject about which he did not care to talk, and accordingly I had curbed my impatience until it was no longer possible to do so.

I shall never forget the look of pain which crossed his face when I put my question; but after considering for a minute or two he merely replied:

"Not just now, Douglas; you are still too young to understand. When you are older I may tell you the story of his death. But never speak to me of him again, my boy, for it costs me more pain than I like to own even to think of him."

After that I said no more, though my curiosity underwent no abatement.

Then my father died, and shortly afterwards I was sent to Rugby, whence I passed to Oxford. In the midst of the work and play of school and college, I thought less of the mystery surrounding my uncle's death, and it was only on rare occasions during vacation time that the desire to unravel it returned to me.

At Rugby and Brasenose my greatest chum was the Hon. Eric Trevanion, the youngest of the four sons of Lord Trevanion. In school and out of it, we were well-nigh inseparable; and so our common delight may be imagined when Eric's father bought the castle and estate of Loch-Eyt, which was, as it were, next door to our house in Lochaber. We had now finished our careers at Oxford (doing nothing very distinguished, I am afraid), and what we should do, or where we should go next, was still a controversial matter. But during this spring we were enjoying ourselves at home—a thing which at no time presented any great difficulties to us.

Well, on this April morning in 187—, I had occasion to pass my uncle's monument, and I stood still, as in my boyhood, to read the inscription. Doing so, the same desire as of old came over me, but more irresistibly than it had ever done before; and, as I remembered my father's words before his death, I determined to ask my mother to tell me my uncle's story. Surely it was now time that I should know!

The resolution was no sooner taken than I acted upon it. Returning at once to the house, I sought my mother's room, and finding her disengaged, I asked her to tell me all about my Uncle Alister.

Contrary to my expectation, she made no demur, but only said:

"I have been anticipating such a request for a long time, Douglas, and have only wondered that it was not made sooner. Your poor father, before he died, told me that he had promised to tell you the whole story, and asked me to do so instead. The tale is a sad one to me, and I do not like to dwell upon it; but you may as well hear it just now as later."

Settling herself comfortably in her chair, while I took possession of another by her side, she commenced.

"You know that your Uncle Alister was your father's younger brother, and they were passionately fond of each other, so much so that they were seldom apart. After our marriage, Alister, at that time about your age, continued to stay with us. He was a tall and good-looking young fellow, and one of the strongest men in the county; and he was such a general favourite that I believe he could have raised a regiment from amongst his admirers.

"Your father, like many more of the family, had been a great traveller before he succeeded to the estates, and had been over most of America and Africa. He had been about to start for India when his father died, and the principal ambition of his life was to thoroughly explore the unknown places of Asia before he died. He had curious ideas of the wealth that perhaps lay in many of the out-of-the-way parts of that vast continent; and, had he lived, I believe he would have carried out his intentions.

"Well, Alister had also the family craze for travel—a craze which I see is developing itself in you, Douglas; and this your father, in default of going himself, strove to turn into an Asiatic channel. But Alister inclined to Africa, and seemed to care little for Asia. I saw that your father would, for very little cause, be off himself to Central Asia, and that the only way to prevent such a thing would be to get Alister to go in his stead. Accordingly I added my influence to Evan's—your father's— and, his brain once fired by thoughts of adventure, he was not difficult to manage.

"In 1850 he started for India, his only companion being an Anglo-Indian of the name of John Nimmo, who had been introduced to him in London as a traveller who had gone through Southern China from Canton to Burma. Nimmo was desirous of further travel, and as he knew much of the languages and manners of many of the peoples of Eastern Central Asia, he seemed just the partner for Alister.

"We first heard from him when he reached Calcutta. He had by that time, in conjunction with Nimmo, decided his course, which was to strike through Assam to the frontier of Burma and Thibet. Then they meant to see if it were possible to cross the intervening mountains and follow the Yang-tse-Kiang northward by way of Bathang and Miniak to its sources; and passing through the Tartar province of the Koko-Nor and the Chinese one of Kansuh, reach the great wall of China, which he and Nimmo would attempt to follow eastward to Peking. This enterprise was bold even to rashness, for at that time the Chinese Empire was shut to foreigners, or rather Europeans, on pain of death. But Alister and his friend apparently thought little of the danger, and we on our part could only hope that he would return all right.

"About three months later we got another letter which had been given to a native guide on the frontiers of Burma, and brought by him to Calcutta. This told of their progress through Assam. Everything had gone well so far—natives friendly, country splendid, and game plentiful.

"This was the last letter your uncle wrote. A year passed without any further news of the travellers, and we were just beginning to feel anxious when a letter arrived from Nimmo from Rangoon containing the sad news that Alister had been murdered by a band of roving brigands in the region of the lakes of the Koko- Nor. But get the letter from my escritoire. It is in the top right-hand drawer above the other papers. Here are the keys."

Deeply interested in the narrative, I hastened to obey, and in a few seconds returned with the letter, of which I give a verbatim copy:—

At Messrs. J. and A. Swan's, Rangoon,

31st October, 1851.

My Dear Sir,

I only arrived here this morning, and consequently can only send you a few lines at present to tell you of the sad fate of your brother, Mr. Alister Dalziel. Fuller particulars will arrive by next mail.

After passing the frontier into Thibet we struck northward—slightly north-west—keeping as far as possible out of the track of native villages, and after incredible difficulties had been surmounted, we reached Sourmang in September. There finding the natives favourably disposed towards us we wintered, starting again in April, and reaching the fertile plains of the Koko-Nor shortly after. Hearing that it would be impossible to penetrate eastward without being discovered and arrested by the Chinese authorities, we determined to go westward through Turkestan and so into Kashmir.

On the evening of the 15th of May we encamped on the banks of one of the small lakes near the Koko-Nor, or Blue Sea. About eight o'clock Alister saw a cloud of dust approaching from the south-east, and by the aid of his glass he made out this to be caused by a large troop of mounted Kolo (brigands, the terror of the peaceful Tartars) coming directly towards us. There was no time to flee. They soon sighted us, and rode down upon us, spear in hand. We held up our hands in token of surrender, but they either did not understand us or did not wish to do so; and in a few minutes we were completely surrounded. I was at once knocked down by a blow on the back of the head, and as I lay on the ground I saw your brother empty his revolver amongst them. He was then set upon by at least six Kolo, and he had received many thrusts, which must have been fatal, before I lost consciousness.

When I recovered I was being cared for by an honest Tartar family, who had found me after the brigands left. On inquiring for your brother I learned that the dead had been thrown by the Kolo into the lake. After my recovery I retraced my steps, eventually reaching Burma in safety.

There can be no doubt, my dear sir, that your brother was killed, and before closing this letter (the post leaves in ten minutes) I must express to you my deep sorrow at the occurrence. Alister had become like a brother to me, and I feel his loss acutely. I will write fuller to-morrow, and meanwhile am, yours very sincerely,

John G. Nimmo.

"We waited for several days," continued my mother, "for the

promised letter, but on its non-arrival your father telegraphed

to the firm mentioned in Mr. Nimmo's letter, Messrs: J. and A.

Swan, bankers, of Rangoon, and from them he received the

intelligence that Nimmo had gone up country immediately, with

what purpose no one knew.

"Inquiries were set on foot, but all in vain. To this day no more has been heard of Nimmo; and at the time it was conjectured that he had been killed by dacoits in Upper Burma. But, unfortunately, there could be no doubt about the truth of his story. Everything pointed to the same conclusion—the wound on the back of his head, the condition in which he reached Rangoon, and the story he told so circumstantially to the people there. His disappearance was the only doubtful point, and he might have had powerful reasons of his own for it.

"Your father's inquiries regarding the Kolo only served to confirm Nimmo's statements. These brigands are hordes of Si- fan, or Eastern Thibetans, who, descending from their mountains like the Highlanders of old, pillage and murder the Mongol tribes who wander over the fruitful plains of the Koko-Nor. They very seldom take prisoners; they are not averse to murder if their purpose can be accomplished in no other way; and, in short, nothing could be more likely than that your uncle had been killed by them.

"That is all the story, Douglas, for it would be too painful for me to tell you how the news affected your father and myself. Indirectly, we were responsible for Alister's death; and I believe your father was never the same man again. He could not bear to hear the incident spoken of, and to the day of his death he reproached himself, perhaps too much, for his share in the matter."

So this was my uncle's sad story! I confess that I was

strangely affected while my mother was narrating the events that

led up to his death; and after thinking over the matter in all

its bearings, I cried, impulsively:

"Mother, I don't believe my uncle was killed by these brigands!"

"Why?" she asked, with more indifference than I had expected.

"That fellow Nimmo wasn't killed, and why should uncle be? True, he fired at them, and Nimmo saw him receive several thrusts; but, all the same, he had fully as much chance as his friend, and I believe he's alive yet, though perhaps in captivity. Then Nimmo's disappearance looks rather queer, to say the least of it, and that letter of his strikes me as somewhat hypocritical. No, I don't think he was killed, and I've a good mind to go in search of him—or, at least, to make sure."

I may here mention that my mother was quite right when she said that I was developing a craze for travel. Such crazes are, I think, hereditary; certainly my father's had descended to me; and this story had served to give mine the impetus it needed. I had always longed to be an explorer, and Central Asia would do as well as, perhaps better than, any other part of the globe; it was certainly less known and much more difficult of access, and there was more than the usual danger when one got there—things not to be despised in this latter end of the nineteenth century.

No wonder, then, that I was quite excited over my new idea. My brain seemed on fire as I pondered over the story I had heard, and considered the chances of finding my uncle still alive. Thibet!—Tartars!—there was magic in the very names; and it was a magic which, in my case at, least, did not take long in accomplishing its purpose.

With my usual impulsiveness—my friends tell me I am very impulsive—I wished to bring down atlases and books of travel at once; but my mother interposed with a still better suggestion.

"I think you might do worse than take a walk over to Loch-Eyt to see Eric; and perhaps you may be able to discuss the matter more calmly on your return."

I was all eagerness to find out what my friend thought of the matter; so I adopted the proposal on the instant, and, five minutes later, I was striding across the moors to Loch-Eyt Castle, with my faithful dog Tray trotting by my side.

THE Hon. Eric Trevanion was three months my junior as regards age, but there was little to choose between us in all other particulars save one. That one was his physique. And, considering that he stood six feet three in his stockings, and his breadth and strength were proportionate, it is not to be wondered at that I came off second-best in this respect. A better specimen of an Englishman than Eric, taking him all round, it would have been difficult to find.

Clear-cut features, hair and eyes of a chestnut-brown colour, and a frank and open expression—these had my friend in common with his three brothers; and as for his accomplishments, when I say that he was a dead shot, an indefatigable deerstalker, a bold rider to hounds, as good a swimmer as Byron is said to have been, and had as much coolness, courage, and determination as any one I ever knew—you should have a pretty good idea of Eric.

As may be supposed, he was a general favourite in the county. He had a word, a joke, or a quotation from his favourite poets for every one; and his bright and cheery presence was, I am told, sadly missed during the periods he was absent.

In short, he was just such a man as one would care to have as a companion when in a tight place; for he could be relied upon to stand by one in every emergency.

He was standing on the steps of the terrace in front of Loch- Eyt Castle—a hoary old pile dating from the time of Harlaw—when Tray and I came up; and he had with him his brother Harold and a stranger. My dog was not long in announcing our arrival. He had been a present to me from Eric, who had named him after the harper's "poor dog Tray" of Thomas Campbell; and I verily believe he had as great an affection for his late master as for his present one. At all events, he always greeted him with great vehemence; and on this occasion he bounded forward and jumped upon him in great glee the moment he caught sight of him.

Eric, as he came down the avenue to meet me, hailed me in his characteristic manner, in the words of Scott:

"'Thy name and purpose! Saxon, stand!'"

"Who is your friend, Eric?" I asked, when I had returned his greeting.

"A sort of half-cousin of ours—an East Indian, immensely rich, and a jolly fellow all round. Come on; I'll introduce you."

I followed him up to the terrace, and, addressing the stranger, he said, "Frank, allow me to introduce to you Dalziel of Airth. Douglas—my cousin Mr. Frank Lee."

Mr. Lee was so dark as to be almost brown, taking the word as it is used in connection with Hindu colour, and his whole appearance gave one the impression that he was not English. Jet- black hair, heavily ringleted, and eyes which seemed almost as black as the hair, denoted that he had at least a strain of foreign blood in his veins. His mouth was almost covered by a heavy moustache, but had a kindly expression hovering round its corners; and, altogether, judging from a first impression, he seemed as nice a fellow as one could wish to meet.

We stood chatting for a few minutes, and then Harold Trevanion called him away to see the kennels; and during his absence I took the opportunity of asking Eric concerning him.

"He only arrived this morning," he answered, "along with his servant, a pure-bred Ghoorka. You may have noticed that he's rather dark, which is not strange, considering that he's a half- breed. His father was my mother's full cousin, and had a somewhat romantic career. During a shooting expedition to Nepaul he fell in love with a dusky beauty, the only daughter and heiress of a wealthy old Ghoorka chief. The father would have nothing to do with him, so he waited until he died, and then married her. After a couple of years in Calcutta, they took up their residence somewhere on the Himalayas, where Frank—who, by the way, is more generally known as 'the Sahib,' a name which was first conferred upon him at school, and which he has no objection to, but rather likes—well, Frank was born and brought up there. Both his parents died lately; like you, he has no brothers or sisters, and, as I have remarked, he is as rich as old Croesus. His servant, Sirikisson, they call him, is a sort of hereditary body- guard, he having done the same duty to old Lee and his Ghoorka wife, and his father to the Sahib's maternal grandfather, and so on."

"And is he (the Sahib) touchy regarding his descent?" I asked.

"Not he. There is nothing he likes better than to talk of his Ghoorka progenitors and their deeds. You know these Ghoorkas, under a fellow called Prithi Nareyan, conquered Nepaul in the middle of last century; and one of the Sahib's ancestors was the most active of the lot, as far as plundering was concerned. No doubt that is how the family got their riches—like some of our own old families, the Trevanions not excepted."

"He must be an interesting sort of fellow, Eric, and I'm glad, for several reasons, that I've met him. How long does he intend to stay?"

"No more than a week or ten days, and then he returns to India. At his place in Nepaul, on the Himalayan slopes, he keeps up royal state; and he has invited me to return with him, promising me as many lions, tigers, and other big game as I wish. If you were only to come, Douglas, by Jove! see if I shouldn't accept."

I had been waiting for an opportunity of opening up the subject nearest my heart; and, now that my chum seemed so set upon going to India, I felt that there would be little difficulty in taking him further.

"It's certainly an enticing prospect," I said, "and I should like nothing better—the more so because I have just heard all about my mysterious uncle, and therefore I'm anxious to get both you and myself off to Central Asia."

"That's good news, although I don't quite see the connection between your uncle, who, according to his epitaph, died nearly a quarter of a century ago, and Central Asia."

"I'll soon make everything clear even to your thick skull," I retorted. "The story is a rather long—But here comes your friend; let us see what he has to say on the subject of Central Asia."

Before I had time to broach the subject to Mr. Lee, however, Eric proposed that the three of us—Harold had taken himself off— should adjourn to the morning-room, in which we could discuss any question, from the income-tax to the Eastern difficulty, more comfortably than in the open air, where the breeze off the sea was still very keen.

Accordingly, we took possession of the room, and, to ensure secrecy, after Eric had brought half-a-dozen atlases and special maps from the library, we locked the door.

Then I told my uncle's story, and read Nimmo's letter, which I had brought over with me. After I had finished, Eric asked:—

"And what is your opinion of it all?"

"That he was not killed at the time, whether he has died since or not."

"It would be worth while to go out just to settle the point. Of course we have the chances of getting served in the same way, you know; but, after all, there is no fun without danger, as the Irishmen say at Donnybrook. And there's sure to be plenty of adventure and sport. What do you say, Sahib, as a man who knows all about it?"

"I can't pretend to know much about it," answered the Indian; "but all the same, I have no difficulty in vouching for the sport. As to your uncle being alive, Mr. Dalziel, I hardly think it probable. Surely, during all these years, he would have had at least one opportunity of escaping and returning home. But if you have any doubts on the subject, it may be better, as Eric says, to settle the matter once and for all. You may rely upon me to give you every assistance in my power."

"Thanks. I will do so if I decide to go."

"Which," interposed Eric, "there is nothing to prevent us doing. Your mother has too much common sense to keep you at home; and my father told me yesterday that all I needed was a couple of years abroad—the more danger the better. So, you see, we may as well look upon it as decided that we go to Asia."

"You are jumping very quickly to decisions."

"And why not? America, North and South, is now as civilized as France; the Arctic regions are out of fashion for the present; Africa is becoming stale, though I admit there is still something to be done in that quarter; so that we have only Asia left. And I have always had a fancy for that quarter of the world. Like your father, Douglas, I believe there's a lot of treasure knocking about in the centre of it; and, as I am not particularly well off—younger sons never are—some of it would be welcome enough to me. Take Thibet for instance. What do we know of it? That not more than four Europeans have penetrated to Lhassa, its capital, during this century; that throughout its immense extent it is practically unexplored; and that it is very rich in gold, silver, and all other minerals. Where is there a better field for a good explorer? Why, for all we know, there may be half a dozen other peoples within it who are utterly unknown to us."

"Speaking of that," said the Sahib, "reminds me of a legend we have in Nepaul, to which it has been exported from the other side of the Himalayas—Thibet. You know that long ago, before British diplomatic blundering in 1792 caused the Thibetans to close the passes between their country and Hindostan, a large trade was carried on; and, even yet, Nepaul, as an independent country, does something with the Thibetans. By means of this intercourse the legend of which I am speaking has reached Nepaul; and as it is a very curious one, and has, besides, some bearing on Eric's conjectures, I will, with your permission, relate it. There is also another reason for attaching importance to it; but of that more in a minute or two.

"The legend, as told by the natives, is as follows: Long ago, hundreds of years before the birth of Tsong-Kaba, the regenerator of the Buddhist religion, which took place in 1357, there was a great war between the Chinese and a portion of the Eastern Thibetans; and the latter, being conquered by superior numbers, retired westward until they came to great mountains. At the foot of these they rested for nine days; but at the end of that time a fierce people swept down upon them from behind the mountains and well-nigh annihilated them. A few were captured, blindfolded, and conducted into a large valley, wherein was a city surrounded by a ring of small mountains, out of which issued white smoke. There were also many more valleys and plains, exceedingly rich, with gold, and silver, and precious stones in abundance. In this El Dorado the prisoners remained for a long time, after which they were again blindfolded, led to where they had been captured, and set free, being warned not to return on pain of death. They reached their own country in safety, and told the story; and since that day many expeditions have striven to reach the mountains, but in vain, for no one knows in which direction they lie—at least with any certainty. Such is the legend of the Kingdom of the Smoking Mountains, generally shortened into the Mountain Kingdom."

"'Gold, silver, and precious stones in abundance,'" repeated Eric, when his cousin had concluded; "it must be a jolly sort of place, that Mountain Kingdom."

"No doubt—if it exists," I replied.

"Every one's not so sceptical as you, old man, and I, for one, am a firm believer in legends. Like Montgomery—

All that old traditions tell

I tremblingly believe.

"But, seriously, there may be some foundation in fact for this one, don't you think? What's your opinion, Frank?"

"I agree with you that it may be true—it would be strange if I, a native of Nepaul, did not believe in a Nepaulese legend."

This was said with a peculiar smile, as if he still knew something more than he had told.

"And what can these 'mountains out of which issued white smoke' be?" continued Eric.

"Volcanoes, no doubt," I said, "though I never heard of them so far inland. It's a remarkable story altogether, and in the course of ages it may have grown from some trifling fact into its present dimensions; but that, again, is scarcely so probable as that there has been at one time a strange people amongst the Thibetan mountains. But legends, however interesting, are not facts, whatever Montgomery or any one else may say."

"Well, the only way to settle it and convince you, Douglas, is to go in search of it and your uncle at the same time."

This bold proposal, thrown out in Eric's most offhand manner, fairly took away our breaths; and before we had recovered, he went on:

"And I'll give either or both of you an even bet of a hundred that we discover this Mountain Kingdom before the end of the year!"

"Done!" I cried. "I know my money's safe enough. Take it up, Lee."

"Thanks, but I'd rather not"

"Why?"

"Because, as I said before, I've another very weighty reason in favour of my legend; and when you have heard this you won't be so confident of the safety of your money."

"Have you seen the Mountain Kingdom?" asked Eric, in excitement.

"No; but I think you know my man Sirikisson Teli? Well, I rather think he can throw some light upon the story; and, with your permission, I'll call him up."

"Do so, by all means," said Eric, himself ringing the bell; and when the servant appeared he told him to send up Mr. Lee's man.

A few minutes later Sirikisson Teli entered the room.

SIRIKISSON Teli appeared to be a little over forty years of age, and his keen and intelligent countenance gave one a good idea of his mental powers. He was short, wiry, and lithe, as be≠came a mountaineer born and bred; and he looked capable of enduring any amount of suffering and fatigue. In almost perfect English—which, as I afterwards heard, he had learned while attending the Sahib during his schooldays—he asked:

"What might the gentlemen sahibs be pleased to require?"

"Sirikisson," replied his master, "this gentleman, Mr. Douglas Dalziel, Mr. Eric, and I have been speaking about Thibet, and we should like to hear all you know about the Kingdom of the Smoking Mountains."

"So you shall," answered the Ghoorka; and, standing where he was, he commenced without any further preliminaries:

"In the days"—

But this did not suit Eric, and he interrupted: "Take a chair, Sirikisson; it's no good standing when there are seats to be had for the asking. And as it's dry work talking, help yourself to whatever you please"—indicating the tray with various liquid refreshments.

Sirikisson availed himself of the chair, respectfully refused the proffered drink, and went on with the story, which I give as I remember it, though I regret exceedingly that I cannot reproduce the Ghoorka's native wealth of imagery and metaphor.

"In the days of old, when the Ghoorkas were at the height of their power, they invaded and conquered Nepaul. Then, hearing of the great riches which lay stored in the palace of the Panshen Lama, then a minor, at Teshu Lumbo, in Thibet, they determined to invade that country, and raised a large army for this purpose. Of this army the great-grandfather of the Sahib was one of the leaders, and my grandfather, Teli, was his servant and trooper.

"At the call of the chiefs, eighteen thousand Ghoorkas assembled at Khatmandu; the passes through the mountains were seized; and our army marched to Teshu Lumbo without the least resistance being offered by the Thibetans. Hearing of our approach, the Regent fled to Lhassa, taking with him the young Lama; and our army captured and sacked the place, took and divided the plunder, and pitched their tents with the intention of remaining.

"But by this time the Regent had sent messages to the Old Buddha at Peking"—(the Emperor of China)—"who despatched an envoy to demand the return of our spoil, on pain of extermination. The Ghoorkas were not afraid of the Chinese, and told them so; while, as for giving up the plunder; our army was determined to fight to the last before doing any such thing. So General Sun-Fo was sent against us with seventy thousand men, and, by means of his cannon, we were defeated."*

(*This Nepaulese invasion took place in 1792, and, after the defeat mentioned by Sirikisson, the Ghoorkas were again routed at the passes. Sun-Fo followed them into Nepaul, defeated them a third time near Khatmandu, and dictated his own terms. The plunder had to be restored, and, to prevent future raids, the passes were closed against natives of India, as they remain to this day.—D.D.)

"Teli, my grandfather, after doing his utmost—but what could one do against four?—fled when he saw that there was no hope of victory; but, being cut off from the rest of the Ghoorka army, he was forced, to save his life, to flee in the direction of the setting sun. For eight months, mostly winter, through snow and ice, he wandered over mountain and valley, hardly knowing or caring whither, and living on the hares and wild fowl he snared, the fish he caught, and the black barley he stole from the huts.

"In this way he came to a river, which, confined between walls of rock, was nevertheless broad and calm, flowing on so placidly that it seemed out of place amidst such scenery, where one would rather expect a wild and turbulent mountain stream. He swam across this at a point at which the walls were low, and climbed the opposite bank, only to find mountains which, rising up almost as high into the air as the Himalayas, were little less than perpendicular, and absolutely impossible to climb. He followed their base for many miles, but nowhere could he reach more than a few hundred feet up; until, despairing of finding another way onward, or so much as a pass, he recrossed the river. The next morning he saw in the distance a mountain whose summit appeared to be higher than those he had attempted to climb; and determined to find out, if possible, what was behind, he made his way to it, and, after difficulties which would have appalled any one but a Himalayan Ghoorka, he reached the summit as the sun was setting. There he spent the night, and on the morn, when the sun had dispersed the clouds, he looked westwards and saw, over the belt of protecting mountains, several small peaks out of which white smoke was issuing.

"It was the Kingdom of the Smoking Mountains!

"But the summits of these were all he could see from his post, although the mountain he was on was the highest for miles around. For more than a week he searched for a pass which should lead him into the Mountain Kingdom, but all in vain: search as he might he found nothing but impassable mountains and sterile ravines.

"At last, his patience and his provisions exhausted, he gave up the quest, retraced his steps, and wandered back to the Himalayas and reached his home, where he had long been mourned for as dead. He never again crossed the Himalayas into Thibet, but on his death-bed he told my father this story, and from him it has descended to me. I believe it to be true, and I am ready to start for the spot at any time."

I have given the narrative of the Ghoorka in as few words as I could; but it is as impossible for me to describe its effect upon Eric and myself as to present an adequate idea of the animated manner in which it was told. Personally, I had been determined to go to Central Asia since hearing the story told by my mother; and, as may be imagined, the Sahib's legend and its subsequent confirmation had in no wise lessened the force of this resolution. As for Eric, he whistled softly to himself, and then repeated under his breath:

"Gold, silver, and precious stones in abundance—by Jove!"

Lee, on his part, watched for some time and with a little amusement the effect of the story on us, before he broke the silence by asking:

"Well, what do you think of it now?"

"The story," I said, "certainly is 'confirmation strong' of the legend, and I have now no doubt that some strange people, unknown to the rest of the world, exist behind these mountains, wherever they are. That is for some one to find out, and, if we decide on going to Central Asia, why not we?"

"Correct, Douglas," cried Eric, with enthusiasm. "Wouldn't it be jolly for the three of us to discover this terra incognita away in the wilds of Asia! But, I say, Sahib, has either of you ever been in Thibet?"

"I haven't; but I believe Sirikisson has—eh?"

"Yes—often," replied the Ghoorka. "As you know, gentlemen sahibs, I was born on the great snowy mountains, and from my boyhood upwards I have been trained as a mountain guide. So, although the passes have been closed, I have often been into Thibet. It is a dreary country, all mountain and ravine, with only a fertile valley here and there."

"Were you ever at Lhassa?" I asked.

"Once, in 1861. At that time the blockade was very strict; but I got over by a pass known only to a few of us guides. I reached Lhassa, and stayed there six months. It is a grand city, with many splendid Lamaseries and much riches—a fine city to pillage."

"So I should suppose," laughed Eric. "But what about this pass? Is it practicable for us?"

"That'll do," I interrupted. "You're taking it for granted, Eric, that we're going"—

"As we are, with you as commander-in-chief, the Sahib as aide, Sirikisson as principal guide, and I as commissary-general and master of ordnance."

"With an eye to the precious stones and other valuables. But proceed, Sirikisson: what about the pass?"

"It is hardly a pass, sahib, and highly dangerous. But, as I have said, I have gone by it, and may do so again; so, if you decide to proceed into Thibet in that way—the only one I know of—I am ready to lead you."

"Well said, Sirikisson," cried Eric; "'your actions to your words accord.' We accept your offer."

"That's all very well," I said, "but you seem to overlook one point. What are we to do after reaching Thibet?"

"Find the Mountain Kingdom!" was the ready reply.

"But how? We have nothing save the faintest idea of the direction in which these mountains lie. The legend says westward; Sirikisson's grandfather wandered towards the setting sun; so that they must lie somewhere in the western portion of Thibet. But that country is vast and unexplored, and we might search over it for years without coming upon this mountain-encircled kingdom, if it really exists."

"There is something in that," gravely responded the Sahib. "And, besides, Teli must have wandered in all directions during these eight months, and his 'setting sun' is really no guide."

While we were discussing this knotty point, Eric intently studied the latest map of Central Asia; and in a few minutes he gave us the results of his investigations.

"Look here," he said, pointing to a spot in the north-west of Thibet, "that must be the place, or near it. All the rest of the map is pretty well filled in, but here it is quite vacant, which shows that it is unexplored and unknown. Moreover, the mountains are very dense around it."

"Sirikisson mentioned a broad river: is it to be seen on the map?"

"No," replied Eric, after a close examination; "there are no signs of one here; but, you know, this part of the country has probably never been explored."

"In that case, should we decide to go, we must be guided greatly by chance. If we escape arrest, the perils of the country, and brigands, not to mention many other dangers, we may make a great discovery; if not, you two will have had your apprenticeship in travel, and perhaps—who knows?—be elected Fellows of the R.G.S."

The mention of brigands recalled to my memory what I had almost been forgetting—that in the first place I had determined to proceed to Asia for the purpose of searching for my uncle, and not of discovering any unknown nation whatever; and thinking that my companions were equally forgetful, I asked:

"And what about my uncle?"

"Just the question I was anticipating," said Eric. "We must manage to kill the two dogs—don't think I am referring to you, Tray—with one bone, as we say in Scotland here, and search simultaneously for both your uncle and the Mountain Kingdom. How is it to be done?"

"I don't know. The Koko-Nor must be more than a thousand miles from this part of Thibet."

"I have a plan," said the Sahib. "After Sirikisson pilots us over the Himalayas, let us strike across Thibet in the direction of the spot Eric imagines to be the Kingdom; and then, if we find no traces of it, we may continue our journey over the Kuen-Lun Mountains into Turkestan, go eastward, and so reach the Koko- Nor."

"A very feasible project," I said; "but don't you think, before pledging ourselves, it would be better to take a little time and consider the matter well? I, for one, know very little of that portion of Central Asia, and I should like to find out something about it before finally deciding."

"What's the use?" said Eric. "I intend to go, so do you, and so does Frank there, not to mention Sirikisson. The best way to find out about anything is by experience."

"Another thing," said the Sahib, "it is now April, and we haven't a day to lose. We should reach the Himalayas by the end of May, cross them and Thibet before the winter—which, I believe, is terribly severe there—comes on, and finish the year in the Mountain Kingdom, if we find it."

"Hear, hear!" approvingly cried Eric. "So you see, old man, you must decide before dinner to-night."

"I don't exactly say that," continued Lee, "and I have a proposition to make—that you consider the matter overnight, consult your people, and meet here in the morning to decide finally."

To this very sensible proposal both Eric and I gave in our assent.

"As for myself, if you two go, Sirikisson and I go with you; and, if not—well, I suppose we shall remain on the southern side of the Himalayas."

After some further discussion the door was unlocked. Refusing an invitation to remain to dinner, I returned to Airth, with Tray at my heels, building castles in the air—castles which, it is needless to say, had the mysterious Kingdom of the Smoking Mountains as foundation.

I HAVE spent more time than I intended over these preliminary notes; and it may be as well, to prevent unnecessary repetitions, to hurry over the few details which still remain to be told concerning our doings at home.

My mother at first positively refused to assent to my journey to Central Asia, giving as her reason that I was certain to meet with the same fate as my uncle; but when I pointed out to her that we should be in much greater force, and were, moreover, going to a different part of the continent, she so far relented as to argue the matter. Then I went over the whole facts of the case, putting particular stress on our guide's knowledge of the country; and in the end, seeing that I was completely bent upon the project, and perhaps knowing the uselessness of trying to dissuade me, she gave a conditional assent.

"Bring over Eric and this Mr. Lee to-morrow," she said, "and, if their arguments are as strong as yours, I may see my way to give in to you. But you must distinctly understand, Douglas, that nothing is more against my wishes; and if I consent, I only do so because I see that you will never rest until you have become tired of travelling."

Knowing that my friends' arguments would be much more cogent and persuasive than mine own, I had little doubt of the final result; so little, indeed, that as we took our usual after-dinner walk I said to Tray:

"Three months hence we'll be tramping over Thibet instead of old Lochaber. What do you think of the prospect, doggie?"

Tray, who, as a year-old collie of the best breed, was as wise as dog can be, looked up into my face affectionately, whisked his big, bushy tail, and barked delightedly, as if to say:

"Yes, won't it be splendid?"

"I see you're as bad as I am, Tray. All the same, we'll take your delight as a good omen."

As my mother desired, I brought over Mr. Lee and Eric to Airth; and the result of their visit was just what I had anticipated. Eric, especially, was fervid in his arguments; so much so, that my mother was fain to ask:

"I am sure that you have some great reason of your own for this expedition, Eric. What is it?"

"Really, now, Mrs. Dalziel, this is hardly fair. You shouldn't ask such personal questions. But I admit that to me the prospects of this journey are very fascinating."

"In what way?"

"In the adventure and sport, for one thing. And then there are—"

"Well?"

"The chances of discovering this Mountain Kingdom of which Frank has been telling you, with all its gold, silver, and precious stones!"

So, when my mother saw that she was overruled, she, like the wise little woman she was, gave in with as good a grace as possible; and, although I now know that she felt my departure much more keenly than she showed, she raised no further objections.

And thus it was decided that we should, ten days later, sail in the steamer Victoria for Calcutta, en route for Thibet.

Were I to detail the various steps we took in preparing for our expedition to Central Asia, my reader would doubtless consider them both tedious and uninteresting; and, accordingly, I only venture to remark that, with the help of the Sahib and Sirikisson, everything was done in a thoroughly efficient and trustworthy manner. To make sure that our instructions were being properly carried out by the London firms to whom we had entrusted our commissions, Lee ran up to town three days after that on which we decided, and there he stayed—Sirikisson, of course, being with him—during our remaining week, while Eric and I made the best of our last days in Lochaber for many a month, possibly many a year, to come.

The seven days fled quickly away. Eric and I had bidden farewell to our friends; the tenantry on both estates, although they had such short notice, had given us a farewell banquet; and now, on this our last day in Scotland, we had only to part with our relatives and our homes.

Partings, whether from individuals or from places with which we are familiar and which we love, are invariably sad, and it is not less so when on one hand it is known that a thousand dangers are sure to block the wanderer's path, and that there are ten chances to one against his safe return. Ours was no exception to the general rule; and, even when it was all over, and Eric, Tray, and I were being whirled south to London, we felt terribly downcast. Should we ever return to our native country? or would it be our lot to perish in the pathless wilds of the Great Forbidden Land, our very fate unknown to those nearest and dearest to us?

But our youth and natural buoyancy soon reasserted themselves; we banished all such gloomy forebodings from our minds, and long before we reached the great metropolis we were in our normal spirits, chatting gaily on the prospects of an adventurous journey.

The Sahib and his servant were waiting for us at Euston, and we were conducted to the hotel of the former, where we heard how our preparations had been advanced.

"Your places in the Victoria, which sails to-morrow, have been booked; and everything, from the ropes and tinned meats up to the arms and scientific instruments, is carefully packed, and by this time stowed away in the vessel's hold. In short, we have nothing further to do but go on board with our personal luggage."

This we did next morning, the good P. and O. steamer weighed anchor, and, before evening, we were in the Channel. Next day we caught a last glimpse of Old England, gradually receding from view; and we realized for the first time the full significance of the words—outward bound!

For the reasons I have already given, I will not dwell upon the voyage, although much of what passed was new and fascinating to Eric and me, but not to Lee, who had already been three voyages to and from our Eastern Empire.

Of our various fellow-passengers, and what they said and did; of the first storm and its consequences; of the various interesting matters connected with her Majesty's mails, and the guardian thereof; of the numberless devices invented to make time fly: of all these many interesting details could be told. But the subject has already been treated by other and abler writers; and so we pass on to other matters, more directly concerning our narrative.

The passenger who occupied the berth adjoining mine was a man whose age might have been fifty, and whose whole appearance and demeanour showed that he had travelled much. Of average height, but seemingly very strong, with a deeply-bronzed face, a long, shaggy, brown beard, and hair of the same colour, and a scar on his face, from his brow down his right cheek to his beard—such was Mr. G. Graham Edwards outwardly; and he appeared so ferocious that more than once I have seen the children scatter and flee at his approach. But from what I saw of him at dinner he was by no means a bad fellow, and I suppose that it was his scar more than anything else that frightened the youngsters.

My attention was first particularly drawn to him through my dog Tray. Tray was perhaps the most popular—I can hardly say person, but he fairly eclipsed every "person" on board—animal carried by the Victoria, and every one, from the mighty captain down to the child in arms, vied in doing him honour. I had more than one very high offer for him from rich Indian officials and others; but no fancy prices could tempt me to sell him. His tricks never became stale, however often performed, and as a source of amusement to the passengers he was invaluable.

Well, when we were at Malta I went on shore, and happening to return two or three hours before the others, I was in time to see a strange sight. This was Edwards, surrounded by an admiring crowd of boys and girls—who had apparently conquered their antipathy for the time being—feeding Tray and two other dogs with choice tidbits, after making them go through various evolutions. On seeing me he said:

"We must amuse the youngsters, you know."

I made some commonplace answer, and no more was said; but it struck me as rather curious that a man of his age and position should have grown anxious so suddenly about the amusement of his juniors.

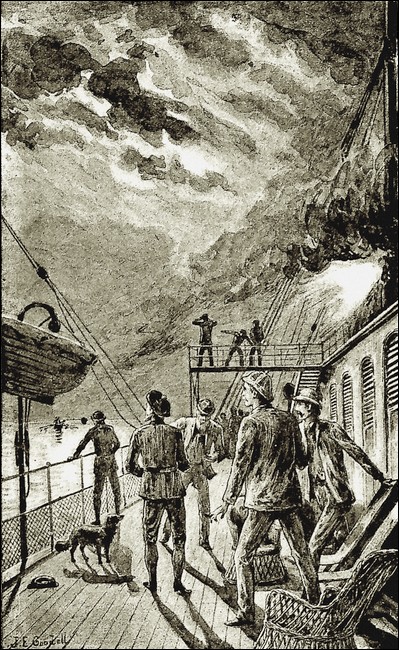

BUT for one event our voyage would have been as monotonous as a voyage to India via the Canal usually is. This solitary event caused some excitement at the time, and formed a fruitful subject of conversation until our arrival at Calcutta.

Steaming down the Red Sea one night, above a week after our departure from Malta, our vessel had almost run down an Arab dhow. It was a beautiful moonlit night, and the three of us—Lee, Eric, and I—were seated on deck, discussing the matter, when we saw that something was exciting those forward. A minute afterwards we heard a splash, and, before we had time to rush forward, the cry which "those who go down to the sea in ships" know so well arose:

"Man overboard!"

"Man overboard!"

We immediately, on hearing the cry, ran forward to where the sailors and passengers were standing; but the moon at this unlucky moment became obscured, and we could see nothing.

Fortunately, we were not going at full speed, and no time was lost in reversing the engines. As soon as the cry had been heard a boat had been lowered, and now, manned by willing tars, it was ready to go to the rescue.

"In which direction?" inquired the second mate as he jumped into it and prepared to cast off.

"By this time he must be at least a quarter of a mile astern," said one of the passengers, whom by his voice I knew to be Mr. Graham Edwards. "I threw him a belt which I am almost sure he caught."

The boat at once pulled off, its officer crying loudly to attract the attention of the "man overboard," should he be above water; while we on the deck of the Victoria waited in terrible suspense, praying for the moon to come out again.

"Who is it? How did it happen?" asked Eric of Edwards.

"Don't you know? It's your black servant!"

"Sirikisson! Heavens! he cannot swim a stroke!" cried Lee in great excitement.

"The sea is as smooth as glass, and he will easily keep up. Besides, he has a belt. But hear that! They are cheering; they must have rescued him!"

From across the water we heard a long cheer; and, just at the minute, like the proverbial policeman who appears when he is not needed, and at no other time, the moon again showed her face, lighting up the scene almost as effectively as if it were day.

Then we saw that the boat was being rapidly rowed towards us; and as it came nearer we distinguished our hardy little Ghoorka sitting beside the steersman, looking none the worse. He stepped on board as nonchalantly as if nothing out of the way had happened; he and his rescuers being greeted with a loud cheer by the passengers, who had assembled in full force at the prospect of some excitement.

The Sahib said something to his servant in the native dialect, and Sirikisson answered at length, seemingly describing the accident. Then he was hurried below to change his clothing, and Lee, turning to Mr. Edwards, said:

"My servant tells me that it is to you, sir, he owes his life. Will you allow me to thank you, both in his name and in my own?"

"It was nothing, I assure you!" answered Edwards. "I happened to be standing near; I saw him topple overboard, and threw him a belt, which he caught—that is all."

"How did it happen?" asked Eric.

"Sirikisson will tell us when he has had a change," answered the Sahib.

"If you will allow me," said our new friend. "I saw it all, from beginning to end."

"Come down to our crib, then," I suggested, "and let us have the story over a glass of wine. It's getting rather cold up here for the tropics."

Mr. Graham Edwards had no objection to accept the invitation so kindly issued; and, accordingly, we descended to our private cabin to discuss the matter with some degree of comfort.

"Your servant," began our guest, after emptying his glass, "was sitting on the bulwark, talking to some of the sailors. I was about a couple of yards off. He had been describing some native tricks, and his hands were in the air, when suddenly the vessel gave a lurch, he lost his balance, and went overboard. There happened to be a belt at my hand, and I tossed it towards a black spot in the water which I judged to be him; but just at that moment the moon retired, so that I could not be exactly sure whether he caught it or not. The only thing I am surprised at is that his head did not strike the side of the vessel as he fell."

"It wouldn't have hurt him, anyhow," laughed Eric. "He is as hard as nails, and has as many lives as a cat."

"What part of the peninsula is he from?" he asked.

"He is a Nepaulese Ghoorka," answered the Sahib.

"Ah! a fine race these Ghoorkas—best in India in my opinion. A matter of ten years ago I was up Nepaul way, shooting big game on the Himalayas, and I saw a lot of them then. Liked them very well. By-the-by, that was where I got this scratch on my face, in a rough-and-tumble with a bear. The bear got the worst of it."

And so on he went until the small hours, telling us tales reminiscent of other days, when he had hunted lions in Africa, grizzlies in the Rockies, tigers in the Sunderbunds, and buffaloes on the plains of the Great North-West. He was a most entertaining companion—and no wonder, for, according to himself, there was hardly a country on the face of the globe he had not at one time or another visited. Even the Arctic regions, we discovered incidentally, were known to him by experience, although of his adventures there he was strangely reticent. When we parted, it was with the prospect of having such another "night" soon.

And we had—more than one of them. On board ship friendships rapidly spring up—much more quickly than on shore; and, in our case, our intimacy with Mr. Graham Edwards soon ripened. Before we reached Aden he had, as it were, become one of ourselves, and the three of us began to look upon him as more than an ordinary acquaintance.

On one occasion, while he was speaking of having been in every part of the world, it struck me to ask if he had ever visited Thibet, and I was just about to do so, when, after some skirmishing to lead up to the question, he inquired if he might join our party.

This took us a little by surprise, and I, as leader, asked him if he was aware of our destination and object.

"Not with any certainty," he responded; "but I can guess. You are going to the Himalayas, aren't you? I've been that way before, and I should like to have another shot at the big game— that is to say, if you care to have me. Of course, I'll pay my share of the expenses. What do you say?"

"We never reckoned on an addition to our party," I answered; "but we'll talk over the matter among ourselves and tell you to- morrow."

"Nothing could be more reasonable," replied Edwards; and then the subject dropped.

A little afterwards I took the opportunity of asking him if he had ever been in Central Asia. He darted a quick look at me before asking:

"Which part?"

"Thibet, or thereabouts."

"Once, in '65 and '66. Know the country pretty well; but it's not much worth, except as regards minerals. Speaking of Central Asia reminds me of a question I intended to ask you, Mr. Dalziel. Are you any relation to a fellow called Alister Dalziel, who was killed about twenty years ago—perhaps more—somewhere in Chinese Tartary?"

"Yes," I replied, not a little surprised; "he was my uncle."

"Indeed! How strangely things occasionally turn up! Why, Mr. Dalziel, I knew your uncle very well in London before he started on his ill-fated journey."

This was news, in faith, and I am not sure that I was not drawn to Mr. Edwards more than ever by the knowledge that he had known the uncle whom I had never seen.

"Did you know Nimmo?" I asked.

"Nimmo! Who was he?"

"My uncle's travelling companion."

"Ah, I remember now. He managed to get off, didn't he, and was afterwards killed somewhere? No; I never happened to meet him."

After considering the matter well, the Sahib, Eric, and I agreed to accept Edwards' proposal, provided he stuck to it after we had told him everything. His experience would no doubt be of much value to us, and, moreover, every addition to our party lessened whatever danger there might be.

So next morning I took him aside and explained fully what we intended to do and where we intended to go; told him all we knew concerning the Mountain Kingdom, and also told him that, failing to discover such a place, we meant to search for my uncle. He listened with much attention until I had finished, and then said:

"You have marked out for yourselves a formidable programme, but I don't say you won't succeed. I think you will."

"Succeed in finding the Mountain Kingdom, do you mean?" I cried, excitedly.

"Yes, if it exists."

"And do you think it exists?"

"I cannot say; but I have seen so many strange things in my travels that I am beyond surprise. As to your offer, I'll certainly go with you, on the understanding you name. I place my services most unreservedly at your disposal, and perhaps my experience may be of some use to you."

In this way the bargain was concluded, and we shook hands over it.

"There is only one detail," he went on, "in which I think your plan is faulty, From what I have seen of the Himalayas, they appear little less than impassable; and I can't imagine how we are to get over, baggage and everything."

"We have considered that," I answered, "and made sure of the matter. Mr. Lee's Ghoorka, the fellow you saved, is familiar with the ground; and he is to lead us over the mountains by a pass with which he is perfectly intimate."

"That is all right. But here are your other two friends, and my future comrades."

Eric and the Sahib shook hands with our new comrade in ratification of our agreement; and henceforth he was regarded as one of our regular party, admitted into our many councils, and consulted on every knotty point that arose. And his advice was really valuable; his experience, as he had hinted, was of much use to us, extending as it did over everything connected with travel and sport. We had the less hesitation in taking advantage of his counsel on account of the pleasant way in which it was given—never ostentatiously, or as if relying on his superior age and experience. He was, moreover, always ready to concede to us any controversial matter; and he carried this to such perfection that I don't believe we had a quarrel, or even anything approaching a heated argument, during the remainder of our voyage.

Pleasantly the days flitted past as our good vessel cleaved the waters of the Indian Ocean on her way Eastward ho! At last we touched Ceylon; the southern point was rounded, and we steamed up the Bay of Bengal, the heart of every one on board beating as he thought of the wondrous Eastern land we were nearing.

And then, two days afterwards, the Victoria let go her anchor in the Hoogly alongside Calcutta. We were in India!

"BY Jove!" exclaimed Eric, "this is rough work. It completely knocks the Alps out of time. As the Wizard says:

No pathway meets the wanderer's ken,

Unless he climb, with footing nice,

A far projecting precipice."

It was exactly ten days after the arrival of the Victoria at

Calcutta, and we were already amongst the Himalayas, and, by my

aneroid, close upon ten thousand feet above the level of the sea.

Before us stretched a glorious picture, of which Nature was the

only artist. We were standing upon the edge of a cliff, which

sheered down almost perpendicularly for more than fifteen hundred

feet; the opposite bank, hardly less steep, but much higher, was

clothed from head to foot as with a garment by a forest of

magnificent deodar cedars; while at the bottom of the ravine a

turbulent mountain stream raced on to join some tributary of the

sacred Ganges. To the north we saw a vast and seemingly

interminable range of snowy peaks, raising their silvery heads

into cloudland—it was to these we were journeying; and these we

must pass before we reached the confines of the Great Forbidden

Land of Thibet. And above all stretched the blue sky, not a

cloud, even in these altitudes, to be seen over its whole

expanse, the tropical sun pouring down his rays upon our devoted

heads with merciless vigour.

It was a grand scene, as much beyond the small powers of man to describe as the stars are beyond his reach.

From Calcutta we had passed to Darjeeling, on the lower spurs of the Himalayas, but still more than seven thousand five hundred feet above the sea, and to which the railway did not then, as now, penetrate. There we heard that the two principal passes into Thibet, the Jeylepla and the Parijong, were so firmly closed that we could not hope to get through; and that, in fact, several sportsmen had been turned back only a few weeks previously.

Three days afterwards we arrived at the Sahib's place in Nepaul, charmingly situated in a valley amongst the mountains. I have no space to tell of the patriarchal welcome he got there; of what we said and did during our short stay at his little estate; and of how we heard our national bagpipes, which are said to be now the national music of the Nepaulese also.

We had here to face a very serious question, which at one time threatened to bring our plans to the ground. We had a considerable amount of baggage of various kinds—a large bell- tent, our arms and ammunition, hatchets and knives, scientific instruments, changes of clothing, ropes and a rope-ladder, a supply of food and medicine, a few books, lighting materials, and the various nondescript but not less necessary articles which go to make up the outfit of an exploring expedition. We had nothing but what was absolutely needful; but how were we to get such an amount of luggage over the Himalayas? It would be far more than we could ourselves carry, even if we were only to walk over level ground, instead of having to climb almost impassable mountains.

We were all at loggerheads on the subject, until Lee solved it in his usual quiet way.

"Leave it to Sirikisson and me," he said, "and be ready to start to-morrow morning at ten o'clock."

We were quite willing to do so. And, sure enough, next morning, when we were ready to commence our march, imagine our surprise when we saw six sturdy little hillmen shouldering our stores, each taking a load which would have more than sufficed for two English porters!

"And do you mean us to take these men with us also?" inquired Eric.

"Certainly; why not? Besides their load, each carries his own provisions—enough to last him over the mountains and back again; for I do not intend to take them any further. After that Sirikisson will manage for us. These men all know the road; two of them are brothers of Sirikisson and the others kinsmen. Depend upon it I have done the best thing under the circumstances— indeed, it was the only thing we could do."

So we were obliged to make the best of it, and it was really a very comfortable arrangement for us. With only a light load each of the more valuable things, and our rifles in our hands or slung over our shoulders, we were free to do as we pleased.

Thus, when Eric made the exclamation which begins this chapter, we had just scaled a steep precipice, or khad, as it is called by the natives, and he and I had halted a minute to rest on the broad ledge above it. The others were all in front; Sirikisson and one of his brothers, accompanied by the delighted Tray, leading, Edwards and the Sahib next, with the other carriers straggling behind. The four Europeans—I include Lee under this category, though I am by no means sure whether he himself would have liked it so—wore white pith helmets, which are about the best things going for keeping out the sun, which at such a height is terribly hot. Eric in his helmet looked a perfect giant, if one may imagine giants with genuine repeating- rifles.

"Yes," I said, in reply to his exclamation, "it is rough work, and the sun is confoundedly strong. All the same, it's hardly as bad as I expected; but perhaps we have still the worst before us."

The others had halted on a miniature plateau under the shadow of a group of pines, and were beckoning on us to come up. By the time we did so they had lit a fire and were cooking a brace of chickore (hill partridges), which Edwards had managed to bring down.

Luncheon over, we resumed our march along the face of the rocks, Eric and the dog a good distance in front, and the Sahib, Edwards, and I in rear. A little afterwards we heard a shot from the rifle of the first-named, and saw a buck bound away on the other side of the ravine.

"Eric has missed," cried Lee. "The shot was too far for him."

After firing, Eric neglected to reload his rifle, but, carrying it under his arm, strode on, looking on every side for more game. But all kinds of animals appeared to be scarce on this part of the mountains, and it was only occasionally that any of us could get a good shot.

Coming to a spot where the ledge he was on widened out to five yards, on which several trees were growing, Eric stopped, intending to wait for the rest of us. Placing his gun against a tree, he took out his pipe and tobacco-pouch, and was about to fill the former, when, to his consternation, he saw a large bear leisurely rounding a tree and coming towards him. Tray gave several barks, but retreated towards his late master, as if uncertain what to do, while Eric, on his part, dropped his pipe and tobacco hastily and made for his gun.

But that, alas! was not loaded, and the only other arms he had were a dirk and a revolver, the latter being, like his rifle, empty. He accordingly could only unsheath his dagger, and, seeing that the huge animal blocked his way to safety prepare for her coming—we found afterwards that she was a mother-bear—as well as he could.

On she came until she was within a yard of him; and then, raising herself upon her hind legs, she wobbled towards him until she was so near that he could feel her foul breath upon his cheek. With his dirk he stabbed her with all his strength; and, just at the critical moment, Tray, with an angry growl at the brute's presumption in daring to attack a Trevanion, sprang upon her back. This created a slight diversion in Eric's favour, but only for a moment; and the bear, shaking off her canine adversary as contemptuously as we brush off a fly, again made for her enemy.

This time there was no escape from her clutches, and Eric, for the first time in his life, was clasped in a bear's embrace, but not before he had succeeded in slashing her over the face with his dirk. Blinded with her own blood, and tormented by the plucky attacks which Tray, with many a bark and growl, was making in her rear, Mrs. Bruin was now in a thorough rage; and it looked as if it would go hard with my friend, struggling ineffectually in the animal's iron grip.

And hard it assuredly would have gone had it not been that, alarmed by my dog's peculiar barks, we hurried up in time to prevent a catastrophe.

My gun, by good fortune, was loaded, and taking in the situation at a glance, I came up behind her, and, placing the muzzle in her ear, pulled the trigger. She fell like a stone, drawing down Eric with her.

Luckily, with the exception of some trifling bruises, he was little the worse, and a sip of brandy set him upon his feet almost immediately. The animal was a magnificent specimen, and, thinking that her skin might be of some use should we ever reach Thibet, the hillmen relieved her of it. On examining her body we found that Eric's first stab had penetrated to within an inch of the heart, while his second had rendered her right eye useless. My bullet had lodged in her brain, killing her instantaneously.

These animals, it is said, are as a rule quiet, unless when attacked; but in the latter case they become so ferocious— especially if they are mothers with one or two cubs—that they are almost as much to be feared as tigers. Indeed, it is seldom that a native escapes from their clutches without a permanent disfiguration—if, that is to say, he gets off with his life. This being so, we could not understand the cause of the unprovoked attack on Eric, until we surmised that, as the animal was a female, her lair was not far away, and that she had merely been defending it. A search was accordingly organized, and, sure enough, we discovered it not a hundred yards distant, occupied by two three-months-old cubs. These Sirikisson despatched.

On our return from this little expedition, we found Eric engaged in loading his rifle and revolver, and when he had received our congratulations he said:

"It was a narrow shave, and no mistake, and, for one thing, it'll teach me in future to keep my arms loaded."

"You've managed to come off better than I did, Trevanion," said Edwards. "It was down country a little that I met my bear, and he left his mark on my face before I polished him off."

This was our first real adventure, and as we sat round our roaring fire on the spot where the combat had taken place—for it had been resolved to spend the night here, both to allow Eric to recover fully from the effects of the encounter, and because it was a favourable place in which to camp—we had reason to feel pleased that it had turned out so well. Tray, especially, was more than satisfied at his share in the transaction; and as he licked his lips after a savoury supper of bear's steaks, he no doubt wished for a few more fights of the same kind.

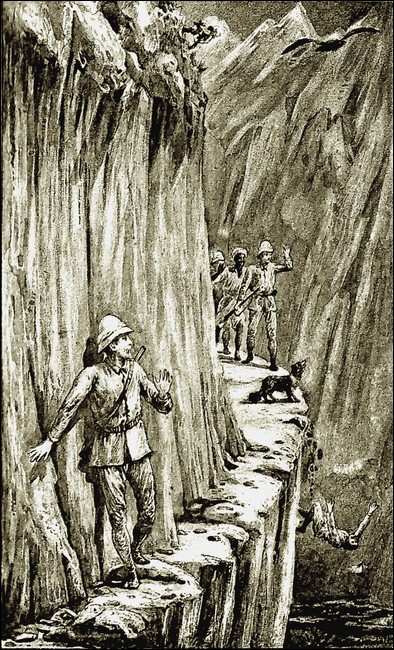

Next morning we continued our journey, the route being along a ledge three feet (less in some parts) wide, which wound up and down the south front of a mountain. It was a precarious foot- path, for one false step would have sufficed to hurl us hundreds of feet down the khad to death and annihilation. But it was the only one available, and with moderate care safe enough to people used to mountaineering, as all of us were.

I could easily fill a volume with our experiences in the Himalayas, telling of the wonderful varieties of animal and vegetable life we saw at such an altitude, and of our various doings; but keeping in mind how much has lately been written about life amongst these mountains, and that I have still to relate the particulars of our journey across an unknown country, I do not think you will quarrel with me if I only touch upon our more remarkable adventures, and upon points which have a direct bearing on my narrative. Minor incidents I must pass over— unwillingly enough, but yet of necessity.

One of these remarkable adventures took place that very day. We were proceeding slowly along the ledge in single file, with a considerable distance between each, Sirikisson first, followed in order by Edwards, Eric, the Sahib, Tray, and myself, with the hillmen behind. Beautiful white and red rhododendron bushes were blooming above and below us, sometimes over the path, and we found it hard to fix our attention closely upon our footsteps, while all around nature was so lavishly beautiful, literally "wasting its sweetness on the desert air."

Sirikisson had more than once warned us to take care at places where the ledge had crumbled away, and now he did so again. Edwards and Eric passed safely, but the Sahib had been more occupied in watching the evolutions of a golden eagle than in paying attention to the guide. In consequence he stepped on the dangerous spot carelessly, his foot slipped on the crumbling earth, and before he could put out a hand to save himself he had disappeared over the khad.

I HAD been about fifty yards behind Frank Lee, and, immediately on seeing him miss his footing and disappear over the khad, I rushed forward with a cry of horror, entirely careless of the danger of haste on such a precarious path. But, long before I reached the spot, my dog Tray was at it; and, when I came up, he was standing on the extreme edge of the precipice, howling piteously. This alarmed those in front, who, looking back, missed the Sahib, and, at once realizing that an accident had taken place, retraced their steps.

The Sahib in danger.

In the meantime I had got upon my knees, and almost sick with apprehension—though I am by no means a nervous man—looked over the khad. I hardly know what I expected to see; I had a dim idea that if I saw my comrade at all it would be lying mangled and shapeless on the sharp rocks at the bottom of the ravine. Judge, then, of my joy when I saw that, not fifty feet below, a magnificent gnarled deodar tree (which in the Himalayas is something widely different from the puny specimens to be met with in England) grew outwards from a crevice in the hillside; and entangled amongst its branches the Sahib was lying, they having proved thick enough to bear his weight.

"Hurrah, Eric! he's safe!" I cried, forgetting in my excitement that our comrade was still in a rather tight place, to extract him from which might turn out a very difficult job.

Eric, Edwards, Sirikisson, and the carriers had by this time joined me, and were now engaged in gazing over the all but perpendicular cliff.

"Hullo, Frank! how do you find yourself down there?" shouted Eric. "Keep up your spirits, and we'll have you up in a jiffy."

No answer.

"He must be insensible," I said.

"He is, so far as I can see," announced Edwards who had been looking at him through a field-glass. "I can't see his face very well; but from the way he's lying I'm sure he's unconscious."

"We must get him up somehow," I said; "but how is it to be managed? The khad is absolutely unclimbable—"

"I have it!" exclaimed Eric; and then, without deigning to inform us further, he asked Sirikisson which of the hillmen had the ropes.

The particular carrier found, his load was unpacked with all haste, and the rope-ladder and ropes taken out.

One end of the ladder was affixed to a stout young cheel pine, as also was one of the ropes, on the other end of which we made a running knot. The other end of the ladder was then thrown over the khad, and Eric, taking the looped rope in his hand, descended it until he reached the deodar.

He found the Sahib lying across one of the largest branches, his head supported by another, and one of his legs dangling in mid-air. He himself dared not leave the trunk of the tree, for his extra weight might have broken the branch, and doomed them both to a frightful death; and, therefore, seeing that the Sahib could do nothing for himself, he had some difficulty in adjusting the rope round his body.

At length, after many futile attempts, he succeeded in placing the noose below Lee's arm-pits, and, after drawing it tight, he gave us the signal to hoist up. This was a work of no little danger on such a narrow ledge; and it was naturally much more so for Eric, ascending the swaying ladder with the help of one hand and steadying his cousin with the other. But, every one aiding, it was safely accomplished, and our unconscious friend raised and laid upon the path.

Fortunately no bones were broken, and the Sahib soon recovered from the effects of his disagreeable adventure; and after a couple of hours' rest we were able to continue our journey. But the incident had one good effect: it taught us a lesson we much needed—to be more careful of every step we took, and to follow implicitly the advice of our guide, as one who was better qualified than we ourselves to know what to do.