RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

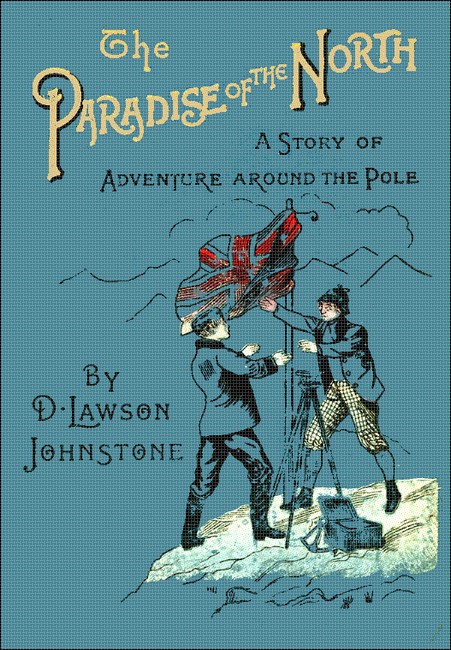

"The Paradise of the North," Remington & Co., London, 1890

"The Paradise of the North," W. & R. Chambers, London & Edinburgh, 1893

"The Paradise of the North," title page of Chambers edition.

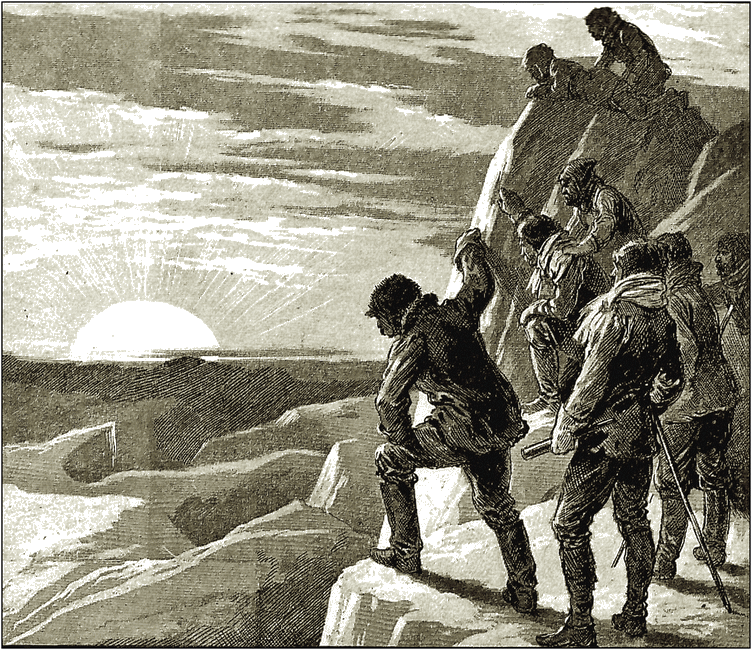

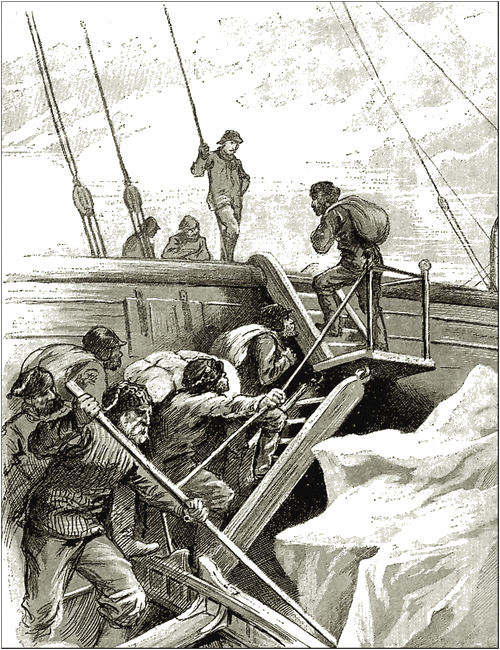

Frontispiece.

Before us stretched a narrow but level valley,

in which patches of snow alternated with green.

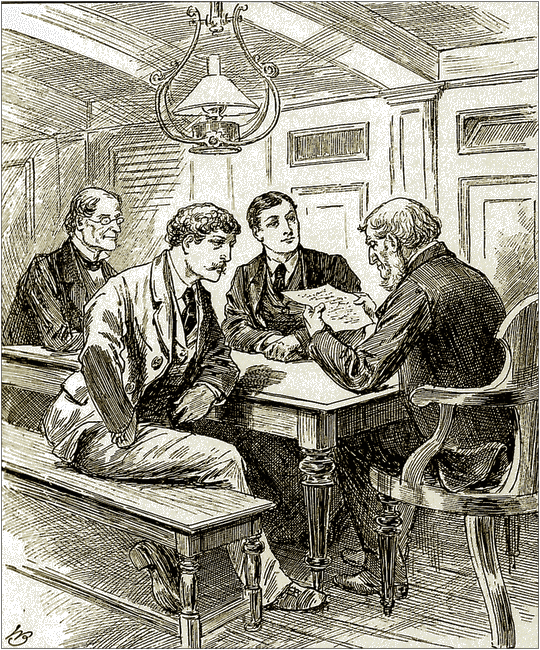

THE solicitor cleared his throat.

'The will I am about to read,' he began, 'was drawn up in June last. Mr Torrens had just been informed by his doctor that he might be carried off at any moment by the disease of the heart from which he eventually died. Accordingly, he called upon me and gave me instructions to prepare this will, which was signed next day. With your permission, Miss Torrens, I shall now proceed to read it.'

There were not many present, this gloomy February morning, to listen to the reading of the last will and testament of Randolph Torrens of the Grange: his only child and heiress, Edith Torrens; her aunt; I, Godfrey Oliphant, of Dreghorn Towers, the manor- house of the next parish; my younger brother Cecil, who had a place as by right at Edith's side; one or two neighbours; a few of the servants, there on their mistress's invitation; and Mr Smiles, the family lawyer. The funeral was just over, and the great crowd which had assembled in the little country churchyard to do honour to the dead had melted quietly away. Now only the memory of a good and upright man was left. For more years than I could remember, Randolph Torrens had been my best and truest friend; and as I sat in his library, listening to his last commands, I could scarcely realise that I should never again hear his cheery greeting.

The friendship between the two houses had always been close, and the bond had been strengthened by my brother's engagement, a few months before, to Miss Torrens. Even then, incongruous as the thought apparently was, I could not help thinking how lucky Cecil had been to win the love of such a girl as Edith. Sitting there together, they seemed 'made each for the other, in the good Providence of life,' as the old chronicler quaintly has it. Cecil—clean-limbed and handsome (I don't mind confessing that the traditionary good looks of the family have somehow missed its present head), in a word, as good a specimen of young English manhood as one could wish to meet; and Edith, a perfect match—her beauty enhanced by the look of pathos in her dark eyes, and the expression eloquent of her grief.

She looked up as the lawyer spoke.

'Pray go on, Mr Smiles,' she said.

The will began in the usual way; bequests of small sums were made to the servants and others, and a larger amount to Mr Smiles; an annuity of seven hundred and fifty pounds was left to his sister, and five thousand pounds each bequeathed to my brother and me, 'as a slight mark of appreciation of the coming connection between the Oliphants of Dreghorn Towers and my family, and of personal friendship towards the said Godfrey Oliphant, Esq., and Cecil Oliphant, Esq.' Then the residue of the estate, consisting of landed property in various counties, articles of value, etc., and the sum of one hundred and ten thousand pounds invested in the Three per Cents., were left unreservedly to his daughter, Edith Belhaven Torrens, Mr Smiles and myself being named as executors. At the same time a sealed packet was to be handed to Miss Torrens; and, the will went on, it was the wish of the testator that his daughter should exercise her own judgment whether the directions therein conveyed should be carried out.

'And this packet,' concluded Mr Smiles, 'it is now my duty to hand to you, Miss Torrens. It was given to me, I may say, at the time the will was signed.'

The servants and strangers here retired, and Edith, who had abstained from examining it while they were present, now took it up with some curiosity. On the cover was the following inscription:

To my Daughter, Edith Torrens—To be opened after my death, and read in the presence of my executors and Mr Cecil Oliphant, and such other persons as she may desire to be present.

'All those mentioned being here,' said Edith, 'I suppose there

is no reason why this should not be opened now?'

'None whatever,' said the lawyer; and so the seals of the packet were broken, and its contents found to be several manuscripts in the handwriting of Randolph Torrens, of which the principal was evidently one headed in the same manner as the envelope.

'May I ask you to read this, Mr Smiles?' inquired Edith, after glancing over it; and the lawyer, who was apparently as anxious as any of us to know what it said, answered in the affirmative, and forthwith commenced:

To my Daughter—

It is my earnest desire that you carry out the directions contained in this note, and it is only in case it seems to you and to those whose advice you take that to do so would be madness, that I leave the matter to your discretion. It is because I am confident that my last wish will be sacred to you, that I do not take other means of ensuring that the hope of my life shall at length be converted into a certainty.

I have left you a sum of money amounting to one hundred and ten thousand pounds, invested in the Three per Cents.—the result of fortunate speculation, animated by one aim. My wish is that this money, or as much of it as may be necessary, should be used for the special purpose of an Arctic expedition. To this end my instructions are: Accompanying this you will find details (drawn up by one of the greatest living authorities on polar exploration) to guide whoever may undertake the enterprise, as to the buying or building of a suitable steam- vessel, and its equipment in the most thorough manner with every Arctic necessity. The captain appointed must have experience, and the crew be well chosen and amenable to discipline. Let the vessel be provisioned for three years.

It is my wish that your future husband should accompany the expedition as your representative; and I hope his brother Godfrey may also go.

The vessel will sail in the course of the July following its preparation to the Nova Zembla[*] Sea; and, if the season be a good one (if bad, the expedition to be postponed until the following year), penetrate north-east to latitude 83° 25′, and longitude 48° 5′ E.

[* Novaya Zemlya. —R.G.]

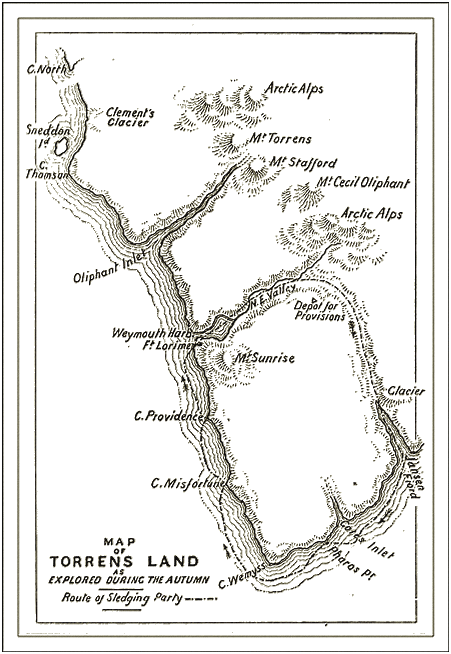

At this point, if the party should be fortunate enough to reach it, will be found a land-locked bay, on a mountainous coast which has never been visited but once, but which I now anticipate to be either a part of Gillis Land, or of the land lately discovered by Lieutenant Payer and the Austrian expedition, and called by them Kaiser Franz-Josef Land. It was here that I and others wintered thirty years ago; and although, for many reasons into which I cannot enter, no account of this voyage was published, it is a fact that our party penetrated farther north than any other has yet done. Here, as there are extensive coal-fields, the expedition may winter in comfort. Then a thorough search will be made within a radius of twenty miles of the bay, and especially in a NE. direction, towards the mountains which will be seen in the distance. This is to be the principal motive of the expedition: To examine the ground carefully for traces of white men, and to follow up any such traces to an end. My reason for this step I am precluded from giving, but I hope it will be enough that I consider it of such importance that I should not care to die without taking means to have it carried through.

The search over, those engaged in it are at liberty to undertake any other project they may have in their minds. It is to be remembered that this point, if they gain it, is nearer the North Pole than has up to the present time been reached. I have every reason for believing that this route is much more practicable than that generally advocated—namely, via Smith's Sound and Robeson Channel; and so, if that be an inducement, those who go will have a better chance of attaining the goal, which so many have striven to reach in vain, than has yet fallen to the lot of any other party!

I have only to request, further, that the strictest secrecy be kept regarding these proceedings. This is more necessary than may be thought.

You have now my directions before you, Edith, and it remains for you to say whether this expedition shall or shall not be despatched; whether the hope I have long cherished is to come to naught or is to be carried out; and whether a mystery which I have never been able to solve myself is to be solved after my death through the agency of my daughter. The choice is before you, and it may not be long before you will have to decide, for I have just heard from the doctor that I may die at any moment.

Randolph Torrens.

June 14, 188—.

As the lawyer finished reading this extraordinary document,

the live of us simultaneously gave a gasp of astonishment. Had

Randolph Torrens really meant what he had written? or had he been

acting under a temporary aberration of the mind? But the

instructions were plain enough, and all doubts as to how they

would be received by the one principally concerned were put to an

end by Edith.

'I don't know what you think of papa's directions,' she said, in a tone of determination, as if she expected opposition, 'but I mean to carry them out, if it costs every penny of the hundred and ten thousand pounds and everything else I have! I know now what he meant just before he died,' she went on, her eyes filling with tears at the recollection, 'when he said, "Edith, be sure and obey me, even after my death." And I will, as far as I can!'

'But, Edith,' interrupted her aunt, 'think of wasting such an amount of money as that—a hundred thousand pounds!'

She stopped as if stupefied by the mere thought, and the lawyer chimed in.

'Consider, my dear Miss Torrens! Don't rush into a decision all at once!'

She turned to him.

'Then what do you think of it, Mr Smiles?' she asked. 'What do you advise?'

'My hands are tied, so to speak,' he answered. 'Some time before your father's death, he called upon me and took me in a manner into his confidence. He strictly enjoined me not to influence your decision in any way, nor, particularly, to do or say anything against the project, but merely to acquiesce in the decision you arrive at. But I could see that his mind was thoroughly bent on this work being undertaken after his death—why, I cannot even suspect.'

'I am equally in the dark,' said Edith. 'All I know is that before his marriage he had been several voyages to the Arctic Seas. Of this one he never said a word to me; but I remember his excitement when, in 1874, he heard of the discovery of Franz- Josef Land, and of his disappointment that the explorers had not penetrated farther north. And often while he has been asleep after dinner I've heard him mutter about "ice" and "open water" and "treachery." "Treachery" was a word he often used. Perhaps it had some connection with the mystery he speaks of.'

'That we must discover,' said Cecil. 'We must reach the place mentioned by some means or other; your father's directions leave us no other alternative. If we didn't, it would be like a breach of trust. We must go!'

Edith gave him a glance of gratitude, and then asked what my opinion was.

'That we should first take technical advice—consult somebody who has been to the Arctic. Then we may know our ground. And, fortunately,' I cried, 'we've got the authority ready to our hand.'

For a sudden thought had struck me. On the shore, half-way between the Grange and Dreghorn, stood a house known all over the Riding as Narwhal Cottage. It was occupied by a retired seaman, who had been for thirty years the commander of Greenland or Spitzbergen whalers (alternated, in the earlier part of his career, with occasional voyages as ice-pilot to Franklin search and other Arctic expeditions), before, in his own words, saving enough to come to an anchor on land. Captain Sneddon he was called; and many were the stories he had told me of his adventures in the frozen sea, with which he was perhaps as well acquainted as any man alive. We could hardly, indeed, have found one better suited for our purpose if we had searched all England.

'Just the man!' declared Cecil, when I had mentioned his name.

'Then let us see him at once!' said Edith; and by her tone I knew that she reckoned on the worthy captain as a recruit.

CAPTAIN SNEDDON, however, was not consulted just at the moment. Edith in her impulsiveness wished to see him without loss of time; but the lawyer had one or two remarks to make before the meeting broke up.

'Your suggestion is a very sensible one, Mr Oliphant,' he said, approvingly, 'and I am only sorry that I cannot accompany you on your visit to this gentleman. I am compelled to return to London by the first train, but I shall await your decision with the greatest interest. Whatever it may be, I have full confidence in your wisdom and discretion. As to the details Mr Torrens has referred to, I have been looking over them, and I find that, as far as I am a judge, they are very comprehensive and complete. But I presume their discussion may be postponed until you finally decide.'

And, after some further talk, he took his departure for London, while Cecil and I looked over the details of which he had spoken. They covered nearly a hundred pages of closely-written manuscript, and embraced, as the lawyer had indicated, every imaginable point connected with an Arctic expedition.

Meanwhile Edith and her aunt had been whispering together.

'Now that Mr Smiles has gone,' said the former, 'I don't see why we shouldn't get this decided as quickly as possible. And there is only one decision we can come to. Of course I can't go out to-day, but if you wouldn't mind, Godfrey, you and Cecil might see Captain Sneddon, and tell me what he thinks.'

'Certainly we will,' I replied.

'And at once, please. Somehow, I feel that the longer we wait the more I am disobeying papa's last wish. I'm sure I shall never be easy in my mind until this expedition has started. For it must go; if I didn't obey that letter, I'd feel like a criminal all the rest of my life!'

'But a hundred thousand pounds to be spent in that way!' reiterated Miss Torrens the elder, as if the fact were still beyond her.

'Yes,' answered Edith, a little fiercely; 'two hundred thousand, if I had it!' Then, more gently, 'What does it matter, aunt? Haven't I, without this, more than enough already? Anyhow, rich or poor, the expedition starts. As to that there can be no other thought!'

'Then what was the use of this show of deliberation?' I asked myself. But I saw that the events of the day had put Edith into a state of nervous excitement, and so, as the best means of calming her, Cecil and I resolved to pay our visit to the captain at the moment. Besides, we were burning with curiosity to have a chance of talking over the matter with one who had experience at his back. So in a short time we took our leave, and as may be supposed, our conversation between the Grange and Narwhal Cottage was of nothing save the dying request—command, one might say—of Randolph Torrens. We discussed it from every point of view, and with more or loss enthusiasm, and I was not surprised to find that Cecil was quite determined to go. As for myself, I succeeded better in concealing my real feelings.

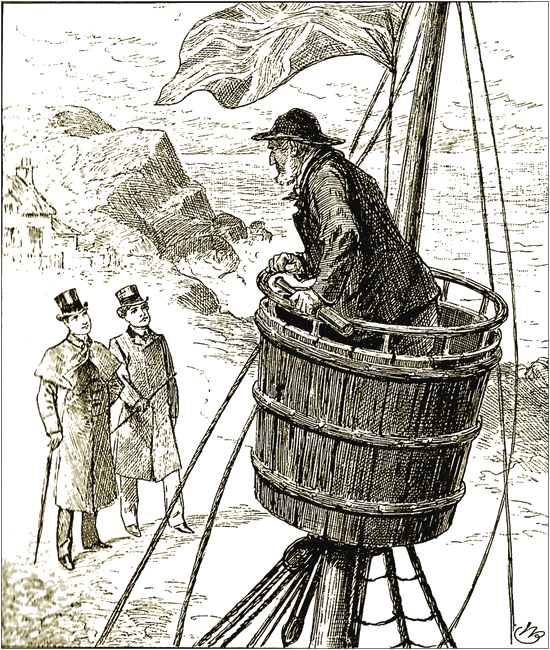

Narwhal Cottage stood a little back from the road, sheltered by a cliff from the sea winds, and within a hundred yards of a tiny cove that harboured the captain's boat. Upon the cliff stood a mast bearing a genuine 'crow's-nest,' one used by its owner during many a hazardous voyage in the frozen seas. Above this tapered the flag-staff, the Union Jack this day at half-mast. The cottage itself was a small but cosy house, 'for,' as the captain was wont to say, 'it's like killing more whales than you can carry to have a bigger dwelling than you need.' His maiden sister, and only relative, was his housekeeper, and, in sight and earshot of the sea as he was, he was as thoroughly happy as he could be while not upon that element.

He was in the crow's-nest—in which he spent most of the day, and, it was rumoured in the district, most of the night also—as we came up; and, seeing us, he descended with the agility of a sailor, and advanced to meet us. He was a man of between fifty and sixty, tall, strong, and unmistakably a seaman; his face baked brick-colour by thirty or forty years' exposure to sea-breeze and sun; his eyes shrewd, intelligent, and those of a man who is conscious of having done his duty, and of being capable of doing it again; and his voice loud, hearty, and as free of affectation as lifelong shouting of orders could make it.

The captain was in the crow's nest when we came up.

'Glad to see you, Mr Oliphant, and you, Mr Cecil,' he said, 'and sorry, too, in those clothes. You will come in and sit down a minute? Thank ye. Mr Torrens's death was as sudden as the fall of an iceberg. I saw him that morning, looking as healthy as you or me. Poor Miss Edith! How does she take it, Mr Cecil? Maybe I shouldn't mention it, and you'll excuse me doing it in my rough way, but it's your duty now to look after her as if she was a vessel on her return voyage, with every barrel full. And,' he went on, with a kindly glance at Cecil, 'you'll do it, I'm sure of that.'

'Please Heaven, I will,' answered Cecil, sincerely, giving the old sailor a cordial hand-shake.

By this time we had entered the cottage, and passed into the captain's cabin, as he called it—a small, circular room, fitted up as nearly as possible like a ship's cabin. It was full of curiosities: harpoons and firearms of every description, models of the various vessels he had commanded, Esquimaux spears, walrus tusks, relics of Arctic expeditions, and so on. Here, as soon as we were seated, he produced a bottle of Highland whisky and some biscuits from a locker.

'Now, captain,' began Cecil, when we had gratified him by drinking his health, 'we've come down to consult you about a very important matter, one that you can advise us about as nobody else that Miss Torrens knows can.'

'Heave ahead, my boy! You shall have my advice, so far as it is worth anything, with the greatest of pleasure.'

Thus encouraged, Cecil went on to relate the events of the morning, read the manuscript of the dead man, and finally repeated the substance of the conversation which had ensued. While he was doing so I watched his auditor closely to see what effect it had upon him; but all I saw was that he followed it with the deepest interest, occasionally nodding to himself as if in satisfaction.

'Well, what is your candid opinion, Captain Sneddon?' I inquired, when my brother had finished.

'With your permission, I will tell you,' he replied, after a minute or two's thought. 'First, that in my opinion Miss Edith is bound to carry out her father's instructions. Dead men must be obeyed; in honour they've a sort of right to it, over and above the usual parental right in this case. Then as to the possibility of success: 83° 25′ is a pretty stiff latitude, especially up Spitzbergen way. Parry's farthest, the highest in those seas, falls far short of it—82° 45′ it was, I think—and it was across nearly two hundred miles of ice. But I don't say it's impossible; the unexpected always turns up in the Arctic, as the saying goes. Sometimes myself I've seen a season commence without any prospect of the ice breaking up, and yet come home full up to the brim. It's chance, and nothing else. This year may be bad, and it may be good; and even if it's good, you'll be lucky to get farther north than 80°.'

'Have you been often in the Nova Zembla Sea?' Cecil took occasion to ask while the captain was refilling his glass.

'Above a dozen times to the west of Spitsbergen, but only twice to the east, between it and Zembla. The first time I was stopped by the ice-barrier in latitude 74°, and came home empty; that, to be sure, was an exceptional year. The other time was in the Moray Firth of Peterhead in '71, when I had the record cargo of the season. We went round the top of Spitzbergen, saw in the distance this Gillis or Giles' Land you spoke of, touched at Nova Zembla, and found no ice to the north of it up to latitude 78°. I've heard it said that you might almost have sailed to the Pole that year; anyway, if I had been my own master, I believe I might have discovered the North-east Passage, instead of this Swedish fellow that has done it since.'

'Then' interposed Cecil, eagerly, 'we've at least one chance in two of reaching this point?'

'By no means!' was the emphatic reply. 'The vessels that usually go to the Arctic—such as whalers, and those foreign scientific turns-out that are pleased with anything— these may have an equal chance. But a vessel with a special purpose like yours—no! One chance in fifty, I should say; perhaps one in a hundred when the purpose is the Farthest North. But for all that I don't say stay ashore; if you do go, you may manage to catch that very chance. And if this paper of Mr Torrens's is correct—I don't say it isn't —he reached that point, and why shouldn't another?'

'No reason at all,' said Cecil, who seemed determined to perceive no obstacles in our way.

'No,' continued the captain. 'As for the paper, it seems to me bony and fidy, as the lawyers say; and if it isn't, the squire know what he was talking about at any rate. Point one—he has struck the right season. August and September are the only open months in those seas. Point two—he's right about the Pole; if you do reach 83° 25′, and find land to the northward, you're bound to succeed. Of course I don't know anything of this route, but I've seen something of the Smith's Sound one, and it's impracticable. I knew Dr Kane, one of whose party said he saw the open Polar Sea; and I've met Captain Hall of the Polaris, who died up there; and yet, if you ask any whaler who knows anything about it, you'll hear that an open basin's rank nonsense.'

At this point we handed him the detailed lists which had been affixed to the document, and requested him to state what he thought of them. He examined them carefully before answering.

'All I have to say is,' he said at length, 'that if you carry out these orders, as I should in your place, your expedition will be the best and completest that ever sailed to the Arctic seas! And what's more,' he went on, 'I'll take it as the kindest thing you ever did if you'll accept my services in whatever way you please, so that, when you sail, you carry James Sneddon with you. It doesn't matter what as—captain, mate, or seaman—but I mean to go, if you'll have me!'

'Then your opinion is,' I summed up, catching some of his excitement, 'that we should carry out the squire's request so far as in us lies, and trust to Providence for success?'

'It is. If you don't go, I've mistaken both Miss Edith and yourselves, and you'll regret it all your lives.'

'You are right, captain,' I said. 'We shall go to the North Pole if possible, and you and Cecil and I shall be of the party.'

In this way was our decision arrived at, as it was evident from the beginning would be the case—arrived at honestly, but perhaps with only a vague sense of the responsibility of that decision, the consequences of which none of us foresaw or could even imagine. Then we went over the principal details with the captain, whose practical knowledge we found to be of immense value. Till then I had had no idea how thoroughly he was master of his profession; but, now that I did know, I made a mental note of it for future use. In the end it was agreed that, after consultation with Edith and Mr Smiles, we should decide as to the best manner of preparing the expedition according to the squire's detailed instructions.

'And,' said the captain to us, as we bade him good-bye at his door, 'be sure and submit my name to Miss Edith as her first volunteer.'

That we did so at once the reader may be certain, and also that Edith was much gratified by the offer, and by the decisive way in which it was made.

Before we went farther, however, Cecil suggested that we should have some one to look after the multifarious arrangements that fell to be made—in fact, to be commander of the enterprise for the present; and he was kind enough to mention me as 'the one best fitted for the work of organisation, which, you know,' he said, 'wouldn't suit a fellow of my habits at all.'

As Edith backed him up, I could do nothing but accept, and I may only mention here that every one concerned afterwards worked so well together that my leadership in that respect was pretty much of a sinecure.

My first step, with the concurrence of Edith and my brother, was to offer Captain Sneddon the command of the vessel to be built or bought. No better man, I knew, or one with more experience, could be had; and, besides, I wished to be able to avail myself officially of his advice on all points on which he could speak with authority.

'Will I accept?' he said, when I made him the offer; 'aye, proud and willing and eager am I to do it, Mr Oliphant. As I said before, I would have gone with such an expedition as a common hand, and now you offer me the command of the vessel! Well, sir, I accept, and if I can help to make it a success you won't have reason to complain. And one thing I'm sure of, though it may look like a boast, and that is, that you'll have the best vessel and the best crew that money can command—and what can't it? I'll pick the men myself, and in Dundee or Peterhead there isn't a Greenland sailor who won't ship under James Sneddon; and there isn't one I don't know and can't vouch for! Yes, barring accidents, this voyage'll be a record one. How could it be anything else, with details like those, and plenty of money to carry 'em out?'

Thus it was that our captain was chosen, and a start thus made with the fulfilment of Randolph Torrens's last request; and as I signed the papers in all due formality, I felt sure that not the least enthusiastic member of the adventurous expedition, of which the history is related in the following pages, would be Captain James Sneddon.

BEFORE the end of April our arrangements were so far completed that a steamer had been bought and fitted up for the special purposes we had in view. The instructions of Randolph Torrens were that a vessel should be built, if one could not be obtained which came up to his requirements; but, fortunately, Captain Sneddon was able to recommend one that fulfilled the conditions. This was the Aurora of Dundee, one of the whaling- fleet that annually proceeds from that port to Baffin Bay. She was a vessel of four hundred and fifty-two tons and seventy-five horse-power, and had been once to the Greenland fishery, having been built by Stephen & Sons for that purpose only two years before. As she had been specially designed for ice-navigation, she required very little strengthening when she came into our hands. The only considerable alterations we made were to introduce sheets of felt between the inside planking and the lining in order to keep up the temperature should we be compelled to winter in the pack, and to have davits on the quarters for shipping and unshipping the rudder when in danger from the ice.

Naturally, our proceedings did not escape notice in Dundee. But the general opinion there, when it became reported amongst those interested in such matters that Captain Sneddon had bought the Aurora, 'and paid a pretty stiff price for her, too,' was that he intended going on a whaling cruise on his own account. He was so well known as a daring ice-navigator and successful whaler that nobody was surprised thereby. This was as well, seeing that under our orders we could not divulge our real mission; and for the same reason Sneddon, in engaging the hands, had to be somewhat indefinite in his statements. He had no difficulty, however, in getting together a good crew. Besides the general readiness to ship under him, the offered pay (double the ordinary wages, and a bonus of one hundred pounds to each man if we succeeded in our object) was such that we could have quadrupled our number of thirty-eight if we had wished.

'You may depend upon it,' said the captain, 'that you'll get men to ship with you on the most risky voyages if only you offer enough.'

Although we were not to sail until July, all the men were engaged during April, for the reason that if we had not chosen them then they would have gone to the Baffin Bay whaling at the beginning of May. They were the pick of the fleet, and many were the lamentations of Greenland skippers that year that the best men were not available. Each hand was well known to the captain, and was willing to spend one winter or more in the ice; 'for,' as he said to them, 'I may tell you at once, though in a manner under sealed orders at present, that our voyage won't be an ordinary one.'

The mystery which otherwise might have surrounded the vessel and its destination was thus partly averted by the captain's adroitness, and partly by the confidence of his men in him.

In other ways I found Captain Sneddon invaluable. There was not a point connected with the vessel to which he did not personally attend, and so thoroughly was he acquainted with all matters pertaining to circumpolar navigation that I felt sure that if we did not succeed it would be through no fault of his. His discretion, as I have indicated, was beyond reproach; and so sure was I that the squire's injunction as to secrecy had been carried out, that I was more than surprised when, one morning at breakfast, I saw in a well-known society paper the following paragraph:

It is whispered that the late Mr Randolph Torrens of the Grange, Yorkshire, whose death we announced a few weeks ago, has left the large sum of one hundred thousand pounds for the purpose of equipping an expedition to the North Pole. We understand that it is now in preparation, and will shortly start. It will be under the command of Messrs Godfrey and Cecil Oliphant of Dreghorn, the latter of whom is engaged to Miss Torrens. The result of this enterprise will be awaited with much interest.

'Look at that!' I said, throwing the paper over to Cecil.

'The douce!' he ejaculated, as he read it. 'How on earth, I wonder, have they found out?'

'Goodness knows!' I replied; 'but it's confoundedly awkward, for now we'll have no peace until we sail. I wish I knew.'

I was not long in discovering the culprit. Having occasion to be over at the Grange that morning, I read the paragraph to Edith and her aunt, and asked if they knew of its author.

'I don't, for one,' said Edith; 'and I don't suppose aunt has mentioned the subject to any one—have you, aunt?'

She said this quite unsuspiciously, but I saw at once she had struck the mark. And, knowing well the elder Miss Torrens's nature and love of gossip, I was not surprised when she replied, somewhat guiltily:

'I'm afraid I haven't been so reticent. Indeed, I saw no reason for it. I was so much against this mad scheme of throwing away your fortune—a hundred thousand pounds, too!—that I mentioned it the other day when writing to Lady Wyllard. And that's all I know about it.'

It was quite clear now, for I knew that Sir Thomas Wyllard, besides being proprietor of the paper in question, was supposed to take also a considerable interest in the editing of it.

Luckily for us, a rival journal had a statement on its own responsibility the following day to the effect that 'it had the best authority for announcing that there was no truth in the story,' and, as proof, pointing to the will, in which the Pole was not even mentioned. What its authority was, I neither know nor care; but, at any rate, the rumour was effectually stopped, for a confidential letter to Sir Thomas Wyllard prevented its recurrence in his paper. Even as it was, we received above a score of offers of service during that one day alone—a warning of what might have been!

One effect it had, however, for which we had reason to bless it. Two days after its appearance, Cecil and I were looking over several reports we had received from Captain Sneddon in reference to the vessel and men, when a servant brought us a card

I recognised the name as that of one of the foremost savants of the day, a man who had a world-wide reputation, and was member of most of the learned societies of Europe. Better still, Cecil, who had studied medicine at a northern university for some time before our father's death, knew him personally as one of the lecturers at Edinburgh.

'Dr Lorimer!' he exclaimed. 'What can have brought him here? I saw the other day that he was in for one of the scientific professorships at Edinburgh, and was sure to get it. But show him up, John.'

In a minute Dr Felix Lorimer entered. He was a man of forty or so, tall and extremely thin, but with a countenance suggestive of much thought and learning, and an equal amount of sagacity not unmixed with enthusiasm. He wore eye-glasses, behind which his eyes twinkled in an extraordinarily animated manner.

'Mr Godfrey Oliphant?' he inquired, advancing into the room, and shaking hands cordially; and when I had replied in the affirmative, he went on: 'Your brother I have the pleasure of knowing. He would have made a good physician some day, if he hadn't been spoiled by fortune.'

'Take a chair, doctor,' said Cecil, with a laugh, 'and tell us if we are to congratulate you as Professor Lorimer.'

'Congratulate me!' he burst out. 'Why, haven't you heard that Hamilton Nelson has got it?—he who knows no more of science than a street newsboy. Beat me by one vote and by superior influence! And that's why I'm here.'

Dr Hamilton Nelson is, as all the world is aware, Dr Lorimer's great rival; but what connection that had with us we could not divine.

'Yes,' he resumed, 'just after I got the news that the Senatus in their wisdom had nominated Nelson, I saw that paragraph in the Sun'—throwing down the obnoxious society paper—'and came off at once to offer my services. I shall go with you to the North Pole, and, when I return with my theories verified, I shall annihilate him—rout him bag and baggage!'

'But doctor,' I interposed, 'haven't you seen this contradicted in yesterday's Mercury?'

He looked as if stupefied for a moment, and then, glancing from one to the other, he continued, quickly and with many gesticulations:

'Isn't it true, then? If it is, as it should be, I offer my services as medical officer free, subject, of course, to you, Mr Cecil. I shall conduct all the scientific observations at my own expense, and I shall subscribe five thousand pounds towards the expenses of the expedition. If that doesn't suit you, I promise to agree to whatever terms you please; for, if an expedition starts, go with it I must!'

He paused as if waiting for us to speak, and his enthusiasm was so catching that I felt inclined to accept him there and then. But I restrained myself, and instead asked him why he was so anxious to go to the Pole.

'I will tell you. In the first place, as I have remarked, I mean to controvert Dr Hamilton Nelson. His theories and mine regarding the Arctic regions are diametrically opposed. He holds, for instance, that there is an open polar sea, and this although now, since the voyage of the Alert, there isn't a prominent geographer, except an American or two—perhaps not even them—who agrees with him. And what are his reasons? His first and greatest is the migration of such birds as the knot, which goes north every spring, is found still going north by the inhabitants of Greenland and Siberia, and comes south in autumn in increased numbers. It is admitted by every naturalist that they must breed somewhere around the Pole—in a land at least temporarily milder as regards climate than the known Arctic regions. But that land isn't necessarily washed by an open polar sea, as he contends, and as I deny. In the second place, he says that as the point of greatest cold is several degrees from the Pole, so the Pole is as likely to have an open sea as any given point south of that point of greatest cold. Now, what I contend, and mean to prove, is that the ice-cap extends over the whole circumpolar region. Open lanes may, I admit, be met with occasionally; winds and currents may produce that temporary effect; but that a permanent open and navigable basin exists is to the highest degree improbable. More: it is absolutely impossible, owing amongst other causes to the configuration of the Arctic Ocean, and to the nature and insufficiency of the channels by which the congestion of the accumulated ice might be relieved. In fact, the whole theory is as plainly a chimera as Raleigh's El Dorado. Then, Hamilton Nelson and ethnology aside, look at what results one may attain, what discoveries one may make in geography, in hydrography, in meteorology, in geology, in zoology, in botany, in geodesy, and in many kindred sciences! And I have no hesitation in saying that an expedition which starts without some one trained to take these valuable observations carefully and exactly, deserves the severest reprobation of the civilised world.'

This very matter of a scientific observer had troubled me not a little; and now that it had been brought home to me in such a forcible manner, I could not but see that our visitor was right.

'There would be little use, doctor,' I said, 'in denying to you that an expedition of the character stated in this paper is on foot'—he seemed as if preparing to give a shout of joy, but sobered down as I went on—'but as to your offer, I am afraid I cannot accept it off-hand. But if you care to stay with us over night, we'll consult the lady we're responsible to, and let you have an answer by to-morrow morning at the latest.'

'Agreed!' he cried, and there the matter ended for the moment, the doctor immediately changing the subject, and going on to speak of the topics of the day, proving himself a thoroughly agreeable and genial fellow. Cecil, in the meantime, rode over to the Grange to lay his proposal before Edith.

'I see no reason for refusing it,' she replied, promptly. 'But we mustn't accept the man's money. Surely we've enough of our own; and perhaps he hasn't too much'—

Cecil hastened to assure her that he was known to have a large private fortune.

'Then it will be the better fun,' she said gleefully, 'to engage him as the ship's doctor at the usual salary, and thus bring him under discipline. And, mind, give him no concession whatever except the choice of a cabin and the liberty to fit it up as he likes.'

After dinner that evening, therefore, I made the doctor the offer suggested by Edith, and after considerable demur he accepted it, though it was with reluctance that he relinquished the idea of contributing towards the expenses.

'But it's all as it should be,' he said, in the end. 'No doubt I'll do my duty better when I know that instead of a proprietor, as it were, I'm only a hired servant. And you may be sure, Mr Oliphant, that the scientific fittings of this cabin I'm to get will be no disgrace either to the expedition or to the cause in which we shall be engaged.'

'Nor,' interposed Cecil, 'to the reputation of Dr Felix Lorimer.'

The doctor bowed; and, now that he was in reality a member of our party, I told him the whole story from beginning to end (impressing upon him, of course, the necessity of secrecy), and how far our arrangements were completed.

'Admirable!' was his comment, when I had concluded. 'Randolph Torrens is a benefactor of the human race, and his daughter worthy of him. Henceforth, if Mr Cecil will allow it, she has a fervent admirer in Felix Lorimer. My friends, I have a belief that we shall fathom both this mystery and the great and hitherto unconquered mystery of the Pole; and I only wish we were on board the Aurora, and on our way to Franz-Josef Land.'

'You may see her to-morrow, if you please,' said I. 'I have just had a letter from Captain Sneddon saying that the alterations are now made, and that she is ready for sea. So we go to Dundee to inspect her before bringing her round to London to fit her up and provision her, and if you care to accompany us you can enter into possession of your cabin at once.'

'But why don't you provision her in Dundee?' he asked.

'Partly because we don't want to cause more remark there than we've already done, and partly to keep the men better in hand than we could at home.'

So on the following day we journeyed to Dundee in company, and found that everything necessary to equip the Aurora for her fight with the ice had been done. As the doctor enthusiastically remarked, she was absolutely perfect. The cabin he chose was one of three opening from the mess-room, the other two being occupied by my brother and myself. It is unnecessary to say that our savant made immediate preparations to utilise his space to the best advantage; and, at least a week before the vessel sailed, the little room was completely fitted up with everything needful in the way of instruments, books, and medicine-chests.

Captain Sneddon had, we found, engaged as chief mate an officer of the name of Norris, who had sailed under him for many years, and who was thoroughly capable of taking command in case of need. A second mate he had not yet obtained. Two engineers, Green (first) and Clements (second), with two stokers, had also been engaged, as also a boatswain, Murray, and the full crew.

Immediately on the arrival of the Aurora in the Thames, the work of loading her was begun. Her bunkers, enlarged for the purpose, were filled to the brim with coal, and the precious fuel was also stowed away wherever room could be found for it. Provisions of every kind, from the salted and preserved meat and the pemmican down to the tea, coffee, and cocoa, were daily received and packed systematically below under the captain's personal superintendence. Nothing likely to preserve health was neglected. Antiscorbutic preparations, such as lime and cranberry juice, cloudberries, pickles, horse-radishes, mustard-seed, etc., we carried in considerable quantities. In addition, we had a large stock of dynamite and gunpowder, the most approved blasting and sawing apparatus, and sufficient firearms and ammunition to serve for many years.

Nor were the means of recreation forgotten. Besides a piano, the doctor's violin, and various musical instruments belonging to the men, a magic-lantern and several games were sent on board, and by means of a well-selected library of two thousand volumes we hoped during the long winter days and nights to keep at bay the demon of ennui.

Our boats, built at Dundee, included a mahogany whaleboat, with swivel harpoon-gun, two smaller ones, two light ice-canoes, convertible into sledges, and several india-rubber Halkett boats. We had also six M'Lintock sledges. But our speciality was the steam-launch Randolph Torrens, built specially to our order by an eminent firm of Clyde engineers. It was of fifteen horse-power, and was adapted for consuming chemically-prepared alcohol instead of coal. The advantage of this (the idea being the doctor's) was that we could carry about with us a larger amount of fuel, and thus make more extended voyages. The launch was a complete success, and was afterwards of the greatest service to us.

Another speciality was a balloon, and the machinery for manufacturing gas for it.

While these preparations were going on, Edith found relief for her mind by continually dragging her aunt up to London to examine our progress. The elder Miss Torrens naturally objected, but, in spite of her protests, not a week passed without a visit from the fair owner of the vessel, for whom the men soon had a warm admiration. 'She'll bring good-luck to the voyage,' the captain said, and the superstitious sailors actually believed in it. But at last, on the 10th of July, everything was done, and the Aurora ready for her cruise to the Northern Seas.

AT three o'clock on the afternoon of the 12th of July, the Aurora cast off from the jetty, and dropped into the centre of the stream.

All arrangements necessary in view of a lengthened absence from England had been made, not only respecting our personal affairs, but also with regard to the safety of the expedition. Should nothing be heard of us for two years, a relief vessel was to be despatched after the second winter; and, to facilitate her inquiries, we were to leave records in prominent places mutually agreed upon. But as it might be impossible to carry out this agreement completely, we promised to take every opportunity of sending home notices of our progress and future prospects by means of such whalers and fishing-vessels as we met.

We had bidden farewell to the many friends who, if uncertain of our destination, had yet no hesitation in wishing us good- fortune and a safe return; and Cecil, on his part, had seen the last of Edith for many months to come. She, the evening before our departure, had got from the captain the names of all on board; and, that morning she had sent down a large box, inscribed 'To he opened on Christmas Day, in, if possible, latitude 83° 25′ N. and longitude 48° 5′ E.'

'And if we can't do it in the Aurora,' said Captain Sneddon, 'we deserve to have had only a herring-boat—it would have been good enough to fail in.'

Edith, her aunt, Mr Smiles, and a few friends of the officers and men, had come down to see us off, and to wish us the best of luck in the discoveries we hoped to make. How reluctantly the final partings were taken, it is needless to say; but at length the hawsers were cast off, and, after a last embrace and cordial hand-shake, the visitors were put on shore amidst the hearty cheering of the men. Slowly the vessel lengthened the distance between her and the shore; in a minute or two we could not see the fluttering handkerchiefs for the intervening shipping; and then, gently and tardily, as if she were reluctant to leave, the Aurora passed through the dock gates and into the Thames. Before evening we were cleaving the waters of the German Ocean on our northward way, and our voyage towards the Pole had begun.

It would have been difficult to analyse the feelings of most of us that night, as we assembled round the mess-room table for the first time.

Here we were, bound on a mission in which the dangers and uncertainties were far out of proportion to the safety, and in which the chances of return were at least as much against us as in our favour. But if there were any for whom that fact was not the greater inducement, we failed to discover them.

It was the captain's idea to take the officers into our confidence as soon as we were at sea, for the reason that if any of them did not care for the voyage they could be set ashore when we touched at Peterhead, as we meant to do to allow the men, most of whose homes were there, to say farewell to their families.

'For if any of the officers don't like our sailing orders,' said Sneddon, 'they must go at once; better work shorthanded than have grumblers and fault-finders on hoard, Why, they'd tell more against us than all the ice in Greenland!'

So the Aurora, for the time, was given into the charge of Murray, the boatswain, and the conference began. One of the eight present was the second mate, George Wemyss, who had been engaged at the last moment. He was an old schoolfellow of ours and an ex- naval officer, who had sent in his papers owing to some quarrel with a superior; and as he had had experience in Arctic work, and was besides a good officer, we were fortunate in having secured him.

I fully explained the origin and purposes of the expedition, not forgetting to mention the probable difficulty of carrying them out, and finally asked each to give his candid opinion of our mission. It lay with themselves, I said, to go or to stay at home; but if they decided to go, we expected that they would honestly and faithfully do their duty.

Wemyss was the first to answer.

'I, for one, am with you to the end,' he said, 'and I'm certain that, if success is to be attained at all, the Aurora will do it!'

For he, too, had been seized by the fascination which our vessel seemed to exercise over every one who had any connection with her.

'And I say with Mr Wemyss,' put in Clements, the second engineer, 'that we're sure to succeed; and, further, that with a vessel and crew like this it would be almost a crime not to go on and do our best.'

'These men we can depend on,' whispered the captain to me. 'I'll be surprised if they don't turn out to be of the very stuff that Arctic explorers are made of.'

Norris and Green also signified their approval of our plans, and their willingness to go on with us, though it was more soberly and with less ostentatious enthusiasm than their juniors.

'Then, that being settled,' said Dr Felix Lorimer, 'let us join in a bumper to our captain and the owner's representatives, Messrs Godfrey and Cecil Oliphant; good-luck to our voyage and the accomplishment of its purpose; and, lastly, to the conquest for the first time, and by Englishmen, of the North Pole!'

Glasses having been emptied to this toast, we went on deck, glad that we had come to an understanding which promised so well for the future.

On the evening of the 14th the Aurora steamed into the harbour of Peterhead, having made an exceptionally quick passage, and proved her sea qualities to be of the highest order. Most of the hands went on shore at once, but were ordered to return the first thing in the morning, that we might take advantage of the forenoon tide. Several letters that had arrived for us were brought on board, and one received by the captain appeared to contain unpleasant or unwelcome news. After reading it several times, and scratching his head as if deeply perplexed, he signed to Cecil and me and Dr Lorimer to follow him into his cabin.

'I've a letter here from my agent in Dundee,' he began, when we were seated, 'and his news strikes me as rather queer, not to say alarming. From what he writes I gather there's a rival in the field—that ours isn't the only vessel that sails this year to the Arctic!'

'I've a letter here from my agent in Dundee,' he began.

'A rival!' exclaimed Cecil, sceptically. 'Do you mean that there's to be an exciting race to the Pole, to end up with a sanguinary encounter in latitude 90°?'

'Joking aside, this is serious news,' I said. 'What does the agent say, captain?'

'Read the letter,' suggested the doctor.

'Just what I was going to do,' said Sneddon, and then went on:

Dundee, 12th July 188—.

My dear Sir—As it may have some bearing on your enterprise, I have thought it my duty to inform you of a curious fact I discovered yesterday by the merest chance. For some time past a whaling-vessel called the Northern Pharos—no doubt you know her—that was built at the same time as the Aurora, but which, for some reason, did not go to the fishery this season, has been fitting out at the docks. It never transpired, however, for what purpose she was intended, nor where she was bound for, and a few days ago she steamed away without any one being any the wiser. Yesterday, as it happened, I fell into conversation with the late owner of the Northern Pharos, and my surprise may be imagined when I learned the following facts. Early in May a stranger had bought the vessel, and ordered her to be fitted up according to instructions he furnished. The strictest secrecy was observed, and so well that nobody suspected that the Pharos was getting ready for a voyage to the Arctic regions. But this is the case, for the man who bought her (whose name I couldn't learn) inadvertently divulged to my informer the information that she was going up 'Spitzbergen way.' Knowing that you would be interested, I ascertained further (for my friend was ready enough to speak now that the vessel had gone) that she was manned by officers and sailors from some English port, and provisioned for three years.

This is all that is known here about the matter, but perhaps you may fall in with her yourself and find out her purpose.

Yours truly,

G. H. Thompson.

A minute's silence followed the reading of this letter. Nobody seemed to know what to think of the thunderbolt that had thus fallen amongst us; and while we were trying to make up our minds Sneddon continued: 'That's the letter, and it strikes me there's something in it that's worth considering. With your permission I'll state the various points I see. In the first place, is this Northern Pharos (I know the vessel well enough—she's smaller than ours, but perhaps quite as well suited for her purpose)—I say, is she going north merely by chance, or in rivalry, as Mr Cecil hinted, to some other vessel? If the former, why has there been so much quietness about it? It looks queer, to say the least if it, that even the owner's name has never leaked out. Then, as to her sailing date—and it is this point that concerns us more than any other—is it only accidentally, so to speak, that she sails almost on the same day as ourselves? These are three points, gentlemen, that seem to me worth looking into.'

'Then your opinion is that, after all, and speaking seriously, we have a rival in the field, or, rather, on the sea?' asked Cecil, in his usual impetuous way.

'Begging your pardon, Mr Cecil,' replied the captain. 'I gave no such opinion, nor meant to; what I did was only to point out what I thought suggestive facts—nothing else.'

'And your facts are suggestive, captain,' I said—'in fact, rather too suggestive to be pleasant. Your agent, I know, is to be trusted, and so we may put every confidence in his information, I suppose. We know, then, that the Northern Pharos has been bought by some one unknown and fitted up for Arctic work; that her destination, like ours, is the Spitzbergen seas; and that she has already started. What we have to consider is if it concerns us—if, in fact, it is by chance, or in opposition to us.'

'All that I have to say is,' said Cecil, 'that it's morally impossible that this expedition is a chance one; the whole circumstances, as we know them, are utterly against the theory. Nothing is more plain than that this mysterious owner, like ourselves, had some definite plan which he wished to keep secret from the world.'

'Then, gentlemen,' interposed the captain, 'it must have been rivalry, according to your own suggestion, Mr Godfrey.'

'And that brings us to the question,' I replied, 'as to any one fitting out an expedition in pure opposition—even saying nothing as to how he discovered our purpose.'

Hitherto the doctor had remained silent, but had apparently followed the discussion with interest. Now, however, he spoke.

'It was, I think,' he asked, 'during the first week of May that the paragraph about the expedition appeared in the Sun?'

'You are right,' I answered. 'It was on the 4th.'

'Then,' he went on, 'I consider that we have a satisfactory explanation of the mystery at hand. Some Arctic enthusiast—I am glad to say there are still a few such—has seen that paragraph, and either disbelieving or having reason to disbelieve the denial that appeared, he has become fired by an ambition to forestall you in reaching the Pole. If he has any knowledge at all of what I may call Arcticology, he would naturally turn first to Dundee for a vessel. While there, he may have learned enough of the Aurora and her destination to serve his purpose. This done, there is no difficulty in imagining the rest.'

'I see, doctor,' said the captain. 'You may be right; so far as we have the facts, you seem to be. But if you are, what's to be done now?'

'We can do nothing but go on with the expedition according to our plans. But if we should happen to meet our rival, as is probable enough, let us go on board and frankly tell him our mission. If he is agreeable, and circumstances permit, we may join parties; if not, let us go our respective ways—within the Arctic circle there is surely room for two ship's crews! Our life, after all, isn't so long that we need allow any such miserable jealousies to disturb us and injure the cause of science.'

This, in the end, was agreed upon as our plan of campaign if we met the Northern Pharos; but, notwithstanding the doctor's theories, there was not one of us who did not retire that night with the feeling that a strange and indefinable air of mystery was hanging over our future movements.

Next morning we left Peterhead, and finally steaming away from the coast of Britain, headed the Aurora for northern Norway. It was our intention to call in at Tromsö in Lapland, to obtain dogs, sledges, and other necessaries not to be had elsewhere, and also to get, if possible, information as to the state of the ice that year from the whalers who frequent the quiet little town. It would doubtless be as tedious to reader as to author to describe in detail the voyage across the North Sea. From a narrative point of view it was absolutely uninteresting; we had not even a storm worthy of the name to break the monotony; and if the doctor and Cecil and I never tired of standing on deck and watching the sea, it was probably owing more to the novelty of it than to any other reason.

In magnificent weather we crossed the Arctic Circle, and a few days later were among the Lofoden Islands. Here occurred an incident—almost the only one of the passage—that caused some excitement to such of us as knew of the letter the captain had received at Peterhead. We had been steaming lazily northward under the lee of a high, rocky island. Suddenly, while we were below at breakfast, we heard the cry: 'A large steamer in sight!'

Going on deck, we found that we had passed the island, and that, not a mile and a half off, close into another island, was the steamer in question, which had hitherto been hidden from us by the land we had left behind. In a minute the captain had brought his glass to bear upon her. After a long and steady look he significantly motioned us aside.

'It's the Northern Pharos!' he said. 'I'm as sure of it as if she belonged to myself. She's the only one of the Dundee fleet besides the Aurora that can be in these waters just now; and if that isn't a Dundee-built whaling-steamer I'll acknowledge I never saw one!'

This latter fact being confirmed by Norris, the first mate, and several of the men, our excitement began to rise.

'What's to be done?' I asked.

'Make sure,' replied the captain; 'and then, as the doctor advises, signal her and find out her destination.'

So saying, he gave orders to get up full steam, which was done; and for above five minutes we approached nearer and nearer the strange steamer. But then those on board seemed to become aware of our rapid approach, and long before we were near enough to distinguish her name, she had also increased her speed and disappeared behind one of the many small islands that are studded about those seas.

'Shan't we have a search for her?' inquired Cecil.

'No use,' said Sneddon. 'We should only lose time, and perhaps find a mare's-nest after all. Best get to Tromsö as quickly as we can.'

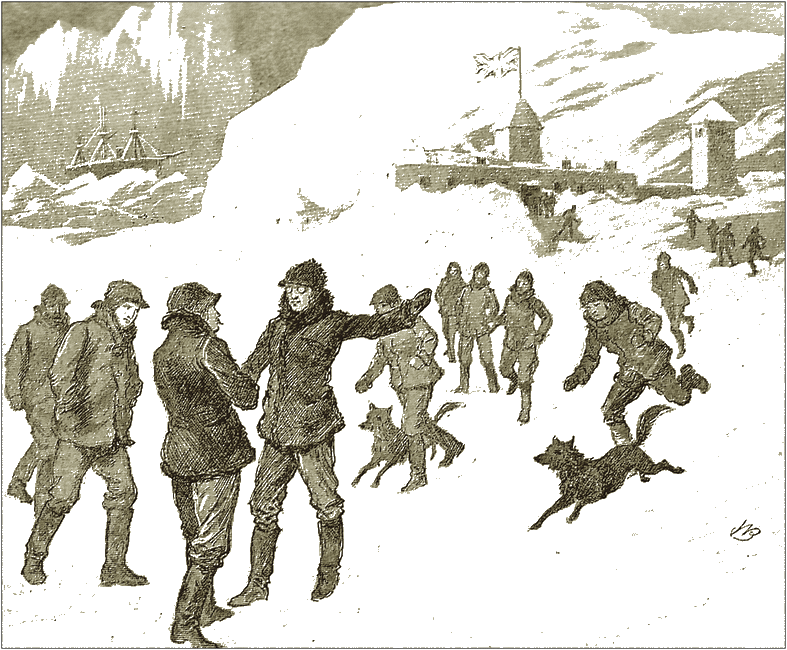

Next afternoon we reached the rocky island of Fuglö, without having again sighted the other steamer; and, taking on board a pilot, wore guided through a perfect labyrinth of sounds and fiords to the anchorage of Tromsö. The British consul immediately placed his services at our disposal, and through him we were not long in purchasing two dozen dogs and three sledges, such as are used by the Lapps, with sufficient meat for the animals. Better still, he recommended to us a Norwegian harpooner and pilot who wished an engagement. This was Nils Jansen, a man who had been an ice-pilot, and as such had accompanied Arctic expeditions ever since his early youth. Needless to say, we secured him at once, and a thoroughly valuable acquisition he was to prove in the days to come.

Late that evening, as the doctor, Cecil, and I were returning from dining with the consul, we were surprised to see through the fog—of darkness there was none, for we were now in the land of the midnight sun—the lights of a large vessel, apparently anchored at the entrance to the harbour. She had assuredly not been there earlier in the evening; and, actuated by a suspicion we could not put to rest, we ordered the boatmen to row down to her. And there, sure enough, when we arrived under her stern, we saw on a rail under the light of a lamp the name Northern Pharos!

'We have her now,' chuckled the doctor as we returned to our ship, on which only one light was shown. 'The morning will verify or disprove my theory, and supply some solution of this perplexing mystery.'

But, unfortunately for Lorimer's reputation as a prophet, the morning did no such thing. These were the words, shouted into my ears by the excited savant, which awakened me seven hours later:

'The Northern Pharos is gone!'

I jumped up. 'Impossible!' I cried.

'Come and see!'

Throwing on some clothes, I rushed on deck and turned to the entrance of the harbour. One glance showed me that he was right; neither at the entrance nor within was she to be seen; she had disappeared as completely as if she had vanished into thin air.

'Where can she have gone to?' I asked, in bewilderment.

'Goodness knows!' was the doctor's rueful reply. 'I am half inclined to believe that this Pharos is only a phantom sent to plague us—a sort of Arctic Flying Dutchman.'

At this moment our new pilot, Nils Jansen, came on board, and I took occasion to ask him for an explanation.

'The vessel you name left this morning as soon as the commander rose,' he said, speaking in almost perfect English. 'My brother Karl, who is her pilot, brought her up last night late; but this morning when the commander woke he at once said to go down again. I was on board at the time, and he looked over to you with not a pleased face. He is a tall man, with much beard.'

This was practically all the information we could get of the Pharos, of the mysterious movements of which the four of us in the secret were never tired of speaking; and we could only hope that the next time we saw her we should be more fortunate in discovering something tangible. Until then it was of no use speculating on what were or might be her aims and reasons.

In the meantime it was agreed that neither the officers nor crew should be told of the vessel; for, as Captain Sneddon said, it was difficult to know how they might receive it. In all likelihood the seamen would find in it some evidence of the supernatural, and their superstitious dreads were capable of leading them into any kind of mischief.

Having received all our purchases on board, and filled up with as much coal as we could carry, we left Tromsö with the good wishes of the kindly inhabitants, and piloted by Nils, passed through the intricate sounds to the open sea. Off Rysö we hailed a whaler going up to the town, and instructed the pilot to inquire if she had seen a steamer bearing northward.

'No steamer,' was the reply given through Nils; 'only a few whalers and sealing-boats.'

We had hardly expected any other answer; but we were more grateful for the information that the whole of the Barents Sea, from Bear Island to Nova Zembla, was particularly free from ice that year.

'Good news!' said Captain Sneddon, gleefully. 'We'll run over to Zembla in four or five days at the most, leave a record there, and then penetrate as far to the north as the ice allows us. With good-luck we may reach our destination before the autumn has quite begun.'

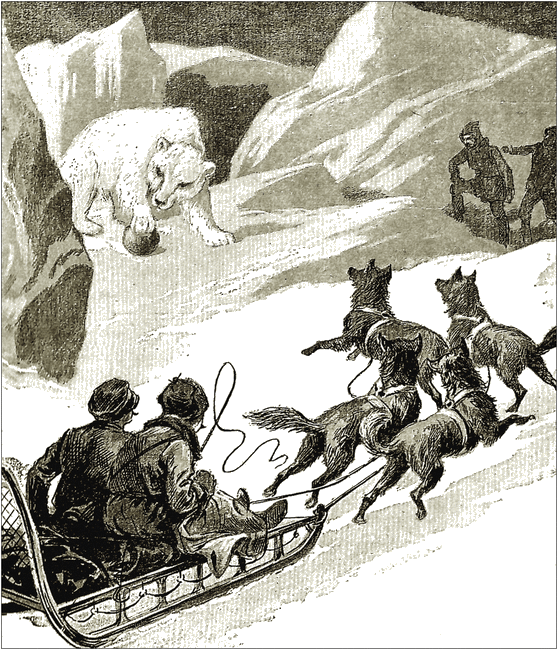

The captain was right, for on the fourth day out from Tromsö we caught sight of Pervousmotrennaya Gora, a mountain on the west coast of Nova Zembla, nearly three thousand feet high, which for centuries has been the landmark of every voyager and adventurer in those lonely seas. Ice now became plentiful, and the temperature fell much below freezing-point. But where there was ice there was game in abundance; and seals and auks, with an occasional bear, whom we never got near, afforded fair sport to those who were inclined that way.

We came at length to a spot where we found it almost impossible to proceed, but as the ice-free coast water was visible beyond, steam was got up, and the Aurora charged the barrier again and again, until she had forced her way through. Once within the ice-lagoon, we steamed quickly northward along the coast, our object being to make Admiralty Peninsula, one of the points at which it had been agreed we should leave a record. Much ice was met with opposite Matochkin Strait, which divides Zembla into two, and leads into the Kara Sea; but, on the whole, the sea was much freer than Nils Jansen had ever seen it at the same period of the year.

On the 1st of August we anchored in a little bay on the west side of Admiralty Peninsula, just above latitude 75°. To the west and south there was a water-sky beyond the small amount of ice visible; but to the north-east the pack stretched up to Cape Nassau, and even farther north, while the ice-blink[*] was particularly well defined.

[* The ice-blink is a peculiar brightness in the sky caused by the reflection of large masses of ice on the air above them. It appears just above the horizon. A water-sky indicates open water in that direction.]

'No farther in this direction, at any rate,' said the captain, 'Better land our depôt and record, and get off to the west and then north as long as we have a chance. Dealing with ice, the man that hesitates is lost.'

The prospect on land was not of an inviting description. It rose in a succession of terraces from the coast to a range of low hills, and the ice and snow still lay on many parts of it: where the thaw had taken effect, the grayish-brown earth was seen, covered here and there with clumps of dark-green moss or saxifrage; and over the whole surface were studded isolated masses of rock of all sizes and shapes.

Here, in a cleft between two rocks that could easily be rendered bear- and weather-proof, we chose a place for the depôt of provisions we had decided to make in order to secure our retreat in the event of the loss of the vessel. It consisted of fifteen hundred rations, chiefly of pemmican, and some ammunition. Finally, two records in tin cases were left in a prominent position, with a notice to the first vessel that touched there to forward one of them to the address given, and leave the other where it was.

ON the 3d of August the Aurora left Nova Zembla, and steaming without difficulty through the ice that lay at a distance of twenty-five miles from the coast, reached open water. She was at once headed northward, her fires put out, and the sails hoisted, and henceforth for the next week or so, until the ice-barrier was reached, her cruise was more like a pleasure trip than a hard-working expedition with a definite aim. The following extracts from my journal may be of some interest, as giving a glimpse of the monotony and uneventful character of this part of the voyage:

August 4.—Compelled to lie-to nearly all day, on account of a dense fog. Nothing is more remarkable in those seas than the sudden changes of weather. In the forenoon it may be the brightest sunshine; by afternoon we may be having a typical Arctic snow-storm; and in the evening we may be enveloped in a fog worthy of Newfoundland.

August 5.—On the rising of the fog this morning, Norris, from the crow's-nest, reported a brig to the southward. We at once hailed her, and on finding her to be a Norwegian whaler almost full, sent on board a packet of letters to be posted when she reached Hammerfest, and also a present of tobacco and spirits for the captain. Shortly afterwards that officer returned the visit, bringing with him some dried fish and seal's flesh for the dogs; and we were much amused by his curiosity and persistent efforts to discover our purpose. We parted at noon, after saluting each other by dipping the Norwegian and British flags. No ice in sight. The whaler reported the year a remarkably favourable one.

August 7.—Sea calm, and still no ice visible. Weather good, with the temperature 35° Fahrenheit in the sun. With a slight breeze from the SW. we made fair progress to the north.

August 8.—To-day crossed the seventy-eighth parallel, without so far having observed any signs of the ice barrier, which, according to all accounts, should have been found much farther south. Not unnaturally, we are elated by our exceptionally good-fortune.

August 10.—Owing to a stiff wind, the Aurora made good progress yesterday and to- day. For the first time since leaving Nova Zembla we have passed several detached pieces of salt-water ice. Cecil and Nils killed two seals. Wemyss reported a slight ice-blink to the NW., but a water-sky to the north. Owing to the fog that came down at night, and the probable vicinity of ice, steam was got up to be ready for any emergency.

August 11.—Passed through large masses of field-ice in latitude 70° 6′. Temperature so much lower that winter dress was distributed to the men. We are evidently near the dreaded ice-barrier, and our real work is now about to commence.

During the whole of that day (the 11th) we threaded our way through the loose ice which, under the combined influences of wind and waves, had been detached from the pack. Towards evening it became more and more plentiful and difficult to navigate; and by midnight there could not be the least doubt that we had reached the illimitable ice-field that so many of our predecessors had found barring their way to the Pole. On every side of us stretched the white, level surface, only diversified here and there by ridges and hummocks which marked the scenes of violent concussions between opposing floes. But, to our immense gratification, the pack was intersected in every direction by open lanes of water that promised at least a chance of reaching still farther north. For the present, however, we sailed eastwards along the edge of the barrier, there being in that direction less of an ice-blink than in any other.

'We've had good-luck so far,' said the captain, next morning, 'and if we can only escape being beset—and we should, with so many advantages that those before us never even dreamt of—we can surely find leads, passes, and ice-holes somewhere to allow us northward. It's a well-known fact that the ice is broken up at this time of the year by lanes and ice- holes'—

'Polynyas, the Russians call them,' the doctor interposed, 'being sometimes of immense extent.'

'Yes; and with discretion and continued good-luck, there is no reason why we shouldn't find them serve our purpose up to latitude 83°.'

At that moment one of the seamen reported that Mr Wemyss from the crow's-nest had seen open water directly north-east, separated from us by a broad tongue of compact ice. We rushed on deck immediately, and in a few minutes the water beyond the barrier was plainly visible from where we stood. Not the smallest opening, however, was to be seen, and the weather was too settled to admit of any hope of a change taking place sufficient to burst the ice.

'We must charge it!' said Captain Sneddon, when he had examined it from the mast-head. 'That open water extends as far north as I can see, and we have only to reach it to have a plain course before us again.'

'Is it quite safe, captain?' I asked, looking doubtfully at the immense mass.

'Under ordinary circumstances it might be risky charging such a floe; but situated as we are just now, with every moment precious, I think we must risk it. And I wouldn't say so unless I was certain the Aurora could stand it.'

Everybody was on deck to see the result of our first conflict with the ice, and as the orders were given to get up full steam and go ahead, I think the heart of each was in his mouth.

The captain himself took the wheel.

'Where does the ice seem weakest?' he asked.

'To starboard a little!' answered Wemyss from above.

'Will that do?'

'That will do, sir. Go on!'

With a shock that shook her from stem to stern, and threw down every one on deck who had not held on like grim death, the Aurora struck full against the ice; and, rising to it six or seven feet, crashed down upon it with the tremendous power of her iron stem. A second time she rose and came down with crushing force. Then, her impetus exhausted, she settled down amongst the fragments into which she had pounded the brittle ice. In spite of the enormous resistance, the vessel had escaped the least injury, and was as sound as before her attack upon the frozen bank. But as yet that attack was not entirely successful; for, although much had been done, the way into the open water was still blocked.

'Another charge will do it!' cried Wemyss, who had remained at his perilous post throughout the whole struggle.

'Steam astern!' ordered the captain.

It was done; and, when we had got a little way on, we returned to the attack at a speed of fifteen knots an hour. Gallantly the Aurora dashed into the passage she had already made, struck the floe with her whole weight, and, amid the ringing cheers of the crew, split it completely in twain, thus gaining the open water she so much coveted after a struggle as sharp as it was short.

'Hurrah!' we shouted in unison.

But our cheering was premature, for the appearance of the ice- hole we had entered proved to be of the most deceptive character. Before we had gone far it began to close in on both sides, until the passage was no more than a thousand yards broad; and by evening we had reached a point where minor leads branched off in every direction. No open water was visible beyond any of them; and, as it is one of the tenets of ice-navigation never to enter even the most promising lane unless one sees where it is to end, the captain was in the deepest perplexity.

'What's to be done?' he asked.

'Take the one nearest our course,' suggested Cecil.

'That won't do—we cannot afford to trust to chance here,' said the doctor. 'Very likely one out of every two of those leads is a cul-de-sac; and if you take the wrong one, it may end in the Aurora being beset. I suppose that's your idea, captain?'

'That's just it, doctor,' he answered. 'It's only a pity the ice is so level here; if we had a decent berg to get to the top of, as you may have at any time in Baffin Bay, we shouldn't be long in settling our course. There's an ice-sky, but with some trace of vapour above the blink. If we could only get a larger range!'

'The balloon!' I exclaimed, suddenly remembering that this was one of the purposes for which it had been bought.

'The very thing!' shouted the doctor; and the next minute he was energetically directing some of the men to raise from the hold the cases containing the balloon and the machinery for manufacturing the gas. Under his personal superintendence the engineers and Gates were not long in fixing the latter; and by next morning we had a supply of gas sufficient for our purpose, though it woefully diminished our coal. There was much interest on board as the immense bag was gradually inflated, and when everything was at last ready for the ascent, the seamen could hardly restrain themselves from thronging aft to examine it more closely.

When the doctor and I had taken our seats in the car (which could hold four at a stretch) the captain followed, with the half-apologetic remark that he wasn't altogether sure about it, but as some people had eyes in their heads and didn't know a 'pass' from a cul-de-sac, he thought he might as well go aloft with us.

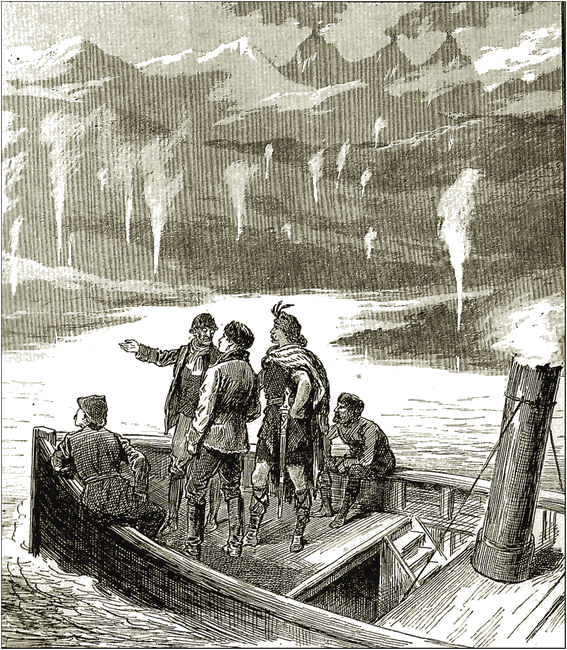

Then the word was given to pay out the captive rope, which, having been made for the purpose, was of unusual strength and practically unbreakable. Slowly we rose, and as we did so the vessel below us gradually lessened in size, while our horizon widened with every foot we ascended. The rope being six hundred feet long, we could get no higher. It was a beautifully clear day, and we saw in every direction the bluish-white ice-fields, intersected by the dark lanes of water, that looked like ink- lines on a sheet of white paper. Through our glasses we closely scanned the view to the north; but none of us could make anything of it but the captain, who, after an exhaustive examination, pointed out as our course a lane we should never have thought of taking. Not only did it seem to lead in a wrong direction, but at the entrance there was scarcely room for the passage of a vessel; but it broadened as it advanced, and led to the only open water that was visible.

'That's our course,' said the captain, 'and I'm bound to say that but for this craft I should no more ha' thought of taking it than of cutting through the ice with a pickaxe.'

By the aid of the windlass we descended without waste of gas, and then the inflated balloon was affixed top and bottom to a part of the poop where it would be out of the way, and be ready for further ascents. This was rendered necessary by the value of our coals, of which no more could be spared for the manufacture of gas. This done, the Aurora entered the narrow channel we had chosen, and was soon again winding her way through the ice to the north.

Hitherto the weather had been calm, but now a breeze from the south-west rose, and a fear was expressed that if it continued it might set the pack in motion. That this fear was only too well founded we were soon to discover; for, just as we had reached the ice-hole we had seen from the balloon, it began to narrow more and more under our eyes. Here, too, the nature of the ice changed, and instead of the comparatively level pack we had met so far it was now raised and hilly, as if from the effect of some convulsion. Bergs, mostly of a small size, also became more numerous as we dashed across the polynya at full speed in the hope of finding a road to the north before the ice closed in. But before long we were again among extensive ice-fields, and although at first we found a broad opening, the lookout from the crow's-nest soon reported that farther progress that way was blocked. With the Ancient Mariner we might have said:

The ice was here, the ice was there,

The ice was all around:

It cracked and growled, and roared and howled,

Like noises in a swound! . . . .

And through the drifts the snowy cliffs

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken—

The ice was all between.

Hither and thither amongst it the Aurora darted in the hope of finding another pass, but always without success; and as the movement of the floes still continued, and a heavy fall of snow had begun, Captain Sneddon decided to anchor her to a berg we noticed in open water, and await the cessation of the ice movements.