RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

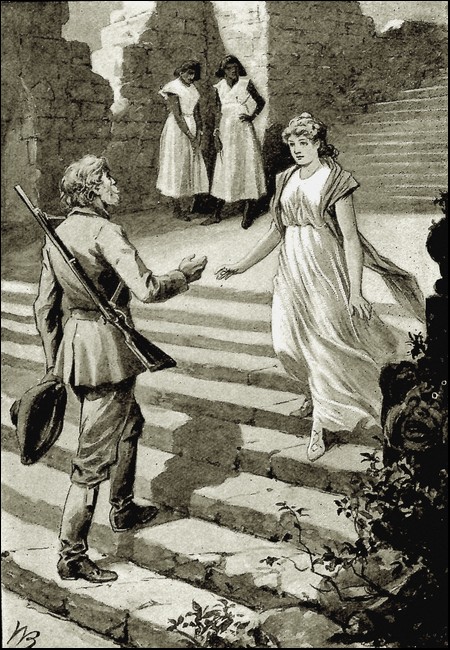

"The White Princess of the Hidden City,"

W. & R. Chambers Ltd, London & Edinburgh, 1898

"The White Princess of the Hidden City," Title Page

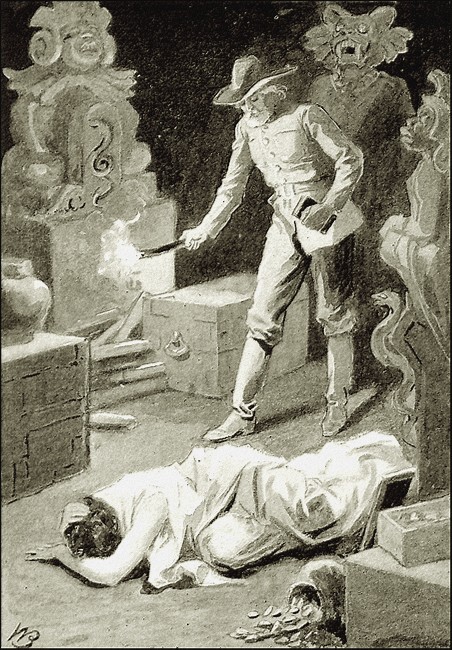

She flung herself on the floor beside the pile

of silver in an uncontrollable outburst of sobbing.

CRACK! Crack!

The quick rattle of a volley of small-arms rang out, and with a whir of wings a score of zopilotes, or black vultures, deserted their duty as scavengers and rose in grave disapproval to the flat roofs of the houses. It was a familiar sound in the streets of Salvatierra, the capital of the little Central American republic which (for diplomatic reasons) we shall call by the same name: familiar alike to the dirty, ungainly birds now settling on the parapets and to the inhabitants in whom a too frequent repetition had long since bred contempt. To the wiser of both species it gave the same warning—the one to keep out of the way in the seclusion of their courtyards, the other to await on the house-tops the passing of the storm. For it only meant that another 'revolution' was in progress; and in Salvatierra revolution vies with bull-fighting as a favourite and engrossing amusement of the populace. It has the advantage over the latter that it is slightly more dangerous.

To one man, however, the sound had a stranger significance. At that moment Mr Leslie Rutherford, an English traveller, was reclining lazily in the interior veranda of the Casa Americana, one of the houses facing the main street, and barely a stone's-throw from the Plaza. He had arrived in the city on the previous evening, and had been tempted by the advertisement of the hotel—it claimed, with trans-Atlantic modesty, to be the only house out of the United States 'replete with every American home-comfort, and managed entirely by Americans'—to make it the starting-point of his present travels. Having had some experience of the States, he had not been unduly disappointed. Now, as preparation for the sight-seeing of the day, he was digesting his breakfast with the help of a cigarette. Leslie looked more than his age of twenty-four or twenty-five years. He had the resolute air of a man who knows his own mind and is not afraid of following its counsels; and with his tall and well-knit figure, blonde hair and moustache, clean-cut features, and eyes that allowed little to escape their eager, intelligent scrutiny—eyes, nevertheless, which at times betrayed the imaginative reflections of the day-dreamer—he could scarcely have been mistaken for a native—for other, indeed, than a type of the race which governs India and has colonised two continents. As the ominous rattle reached his ears and startled him out of vagrant thoughts of his Scots home, and of one whom he had left in the old country, he jumped briskly to his feet.

'What on earth?—'

Crack! Crack! Crack!

He glanced round. For a moment he was alone on the veranda. Tossing his cigarette aside, he picked up his hat and ran across the patio to the open gateway. A minute before the long street, lined in sombre uniformity by the gray, one-storied, flat-roofed houses for which Spanish taste and the fear of earthquakes are equally responsible, had been deserted save by the wrinkle-necked vultures; but now it was echoing to the patter of panic-driven feet and the din of a hundred tongues; and before Rutherford's eyes passed in review an epitome (as it were) of the inhabitants of the republic—Indians in their striped serapes of gay-coloured cloths, mestizos, a few women of the lower class, and last and most significant of all, a ragged company of the native soldiery. More than the exclamations of the crowd, it was the sight of these warriors, fleeing in hot haste from the Plaza, which told the Englishman the truth: not only that a rebellion had broken out, but that in its first steps it had been successful.

In the Plaza the rifle-fire had been followed by round after round of cheering, varied by an occasional revolver-shot. The soldiers were not pursued; and, while the passing mob tailed off with an undecided straggler or two, Leslie Rutherford hesitated whether to seek refuge indoors or venture into the midst of the uproar. He had learned enough about Salvatierran politics to have good cause for hesitation. The day was one sacred to these manifestations of public feeling: the anniversary of that on which the little republic, one of the smallest and most turbulent on the Pacific coast, had—in the noble words of the first pronunciamento—taken her place among the great nations of the earth. True that hitherto she had not quite succeeded in establishing her claim to the satisfaction of the Great Powers; but perhaps that was less by reason of her pretensions than the jealousy of the older and more effete states. For a dozen years past, when not engaged in contracting loans which were afterwards repudiated, she had indulged herself in a quick succession of Presidents, all more or less dishonest, and each as incapable as the others. The present ruler, General Alcazar, had, on the strength of some influence with the army and a saving faith in gunpowder, managed to establish a record of fifteen months' sway. The wiseacres hinted that his time was nearly up. It was rumoured that he had quarrelled with his Minister of War, General Barros Romero, who had also some influence with the soldiers; and as latterly he had become less popular with the fickle mob, developments were hopefully expected. Only the occasion was wanting, and Independence Day invariably gave rise to an ebullition of patriotic excitement. The clamour in the Plaza on this October morning seemed to show that the occasion had not been lost.

Leslie's decision was soon taken. The more prudent part was certainly to stay in the hotel. But he had come to Central America in search of adventures, and his desire to be witness of a revolutionary outbreak was quite enough in itself to outweigh the warnings of discretion. He listened eagerly. A comparative quietness had again fallen on the city; only the low hum of many voices was to be heard, and even the bolder of the zopilotes were returning to their self-imposed duties on the streets.

'I'll do it!' he said to himself; and, running indoors, he armed himself with a revolver and made some hasty changes in his dress. He was recrossing the patio on his way to the street, when he noticed that his host—Isa B. Gray hailed from Hartford, Conn., and had divers lucrative occupations in addition to that of hotel-keeper—was leisurely closing the gate. A little crowd of servants and others had gathered inside.

'A minute, please!' cried Leslie.

The American looked round. 'Oh! it's you,' he said. 'Not going out, eh? Shouldn't advise it, sir. The atmosphere's not very healthy for foreigners this morning.'

'I was thinking of it. There's a shindy on, isn't there? What's it all about?'

'Guess it's only their way of celebrating Thanksgiving Day—with considerable variations. The old story; some racket about knocking under to the Britishers—no offence, sir—any excuse is good enough here for pop-gun practice. This is the way of it. Plaza packed all morning with howling mob—official orators stoned—escort fired upon, and when they retaliated with a couple of volleys, chased from the square. Then the mob appointed orators of their own, and now they are working themselves red-headed against the President. It means trouble, of course. Shouldn't wonder if Alcazar finds some use for those ancient guns of his before he's an hour older.'

'And then?'

'Oh, there's no saying. I'll be considerably surprised if General Romero hasn't a hand in this game, and in that case it's a toss-up. Anyhow, there's bound to be shooting. Take my advice, Mr Rutherford, and lie low. Listen to that! No, sir; the Plaza isn't exactly a healthy spot at this moment.'

'I think I'll risk it,' said Leslie quietly.

Gray shrugged his shoulders. 'Please yourself, but don't blame me if you get a ball through your head. It's no use arguing with a Britisher. Me? Not if I know it, thanks! I've seen seven revolutions, and I expect that's about enough for a respectable Christian. In fact, it's time the gate was barred. They've got to make a rush for the palace sooner or later, and this is their direction. Come, you won't he persuaded?'

'Oh, I'll take good care of myself, never fear,' returned Leslie. 'Now that I'm here, I don't want to miss any of the regular sights. And it isn't every day you have the chance to take part in a revolution.'

'Well, it's your own affair,' said the American, opening the gate. 'Good luck! I'll keep a man here to let you in when you've had your fill of it.'

Nodding his acknowledgments, Leslie passed out and turned quickly in the direction of the Plaza. It was not more than a hundred yards distant. He had almost reached the corner when a new sound reached his ears—or, rather, a medley of sounds, confusing at first, but every moment waxing louder and more distinct. Then the truth struck him: the crowd was breaking from the square. It was even so. As he paused irresolutely, doubtful whether to go on or retire, the advance-guard swept round the corner and was upon him. He had no time for retreat. Before he could realise the full peril of the situation—certainly before he could take the smallest step to avert it—he found himself in the midst of a mob of frantic mestizos, his head ringing with the cries of 'To the palace! to the palace!' 'Down with Alcazar!' 'Viva la Libertád!' 'Down with the English!' and a score of others, shouted out in a hundred discordant and menacing tones. A single attempt did he make, almost instinctively, to draw aside into the shadow of the wall. It was useless. He was completely surrounded by the rioters, carried forward by them in their wild rush as resistlessly as a piece of driftwood by a stream in flood, fearful that recognition of his nationality meant the immediate diversion of his companions' fury to himself. And then?

The emergency demanded the boldest course. Hands had not yet been laid upon him, but there were too many rifles and revolvers around for comfort, and those in his vicinity were glancing at him with curiosity and distrust as they moved onward along the street. He saw that something must be done to disarm suspicion, and saw also that it must be done before the rebels had an opportunity to translate their vague doubt into action. But what could he do?

While he was racking his brain for an idea he felt a touch on his arm.

'Shout!' said a voice in his ear, in good English. 'Shout like fury, sir!'

Looking over his shoulder, he recognised in the speaker one with whom he had exchanged a few remarks on the previous evening in the patio of the Casa Americana. He was a little, wiry, dark-complexioned man, with exceedingly bright eyes, in age between thirty and forty, and apparently a Spaniard or of Spanish descent.

'Shout!' he repeated, crushing to the Englishman's side.

The advice was excellent, and Leslie took it at once. In a minute he was shouting as loudly as any for the downfall of President Alcazar and the English; and, instead of allowing himself to be carried passively on, he was pressing forward with an affectation of zeal that surprised himself. He did not like it, of course; but one does not stick at trifles when one's life may be at stake; and if he must pose as a revolutionary at all, he preferred to act the part to the best of his ability. And he acted it with sufficient vigour to deceive his neighbours. The ruse served its purpose; he had become an unit in the crowd, and was no longer marked out from the others. For the time being he was safe from molestation.

'That's right!' said his new friend. 'You're out of danger now—for the present.'

'Thanks to you, señor.'

'Oh, I am in the same boat myself—caught in the crowd, and couldn't get away. We'll hold together, if you have no objection. Two are always better than one in a fight.'

'Only too pleased,' said Leslie. 'But wouldn't it he safer to speak Spanish?'

'You know it?'

'Yes.'

'Then by all means. . . . There, shout again.'

Thus, almost in the forefront of the mob, they swept down the long Calle Mayor, past the American hotel, towards the national palace. Here and there a head showed itself behind a grated window, but save for these occasional appearances the rebels had the street to themselves. As yet no sign of opposition was visible. Gradually the Englishman gained confidence, and began to take stock of his involuntary associates. Two things were obvious at first sight. Without exception they were mestizos; and a few had rifles, many more had pistols, and all were armed with the machete, or long knife of the country. Their determination was beyond question. Evidently their feelings of bigotry, patriotism—call it what you like—had been worked upon to the utmost, and for the moment they were bent on mischief with all the impulsive impetuosity of their race. The outburst might not be lasting, but there was no saying what it might do while it was still at white-heat. Even Leslie, inexperienced in such crises as he was, recognised their spirit as dangerous.

Meanwhile he felt a certain enjoyment in the position. It had a touch of incongruity that appealed to his sense of humour. Yet this did not make him forget the peril before them; he had no wish to he in the front when the shooting came off. He whispered his fear to his companion.

'Right,' he replied; 'but how are we to get out?'

'Keep cool—look out for the first chance.'

'If we can't?'

'Make one!'

'At the worst. ... I suppose so.'

They were interrupted by an unexpected stoppage on the part of those in advance, and looked round to discern the cause. A significant glance passed between them.

'Why, it's your consulate!' cried the Spaniard, louder than was prudent.

'Gently. . . . Got a shooter?'

'Yes; my Smith-and-Wesson.'

'Have it ready, then. Take care.'

There was a minute or two's jostling and agitation, and then the crowd came to a standstill. The reason was apparent—they had at last found something on which to vent their patriotic spleen. For over one of the houses in the street a Union-jack was flapping lazily against its staff, and it seemed that the mere sight of it had sufficed to redouble the rioters' ardour. For a little the hubbub was deafening. If uproar could have accomplished the death of all the Englishmen in Salvatierra, and pulled down the obnoxious flag, and sacked the consulate—it was for these that the mob clamoured—they would have been done twenty times over. As it was, it was fortunate for those within the building that they kept themselves hidden. Presently words were followed by action; a shower of stones fell pattering against the walls and windows; and then, by way of variety, some of the wilder spirits took to firing at the ensign.

Hitherto Leslie had managed to remain pretty quiet, though not without the exercise of a little self-control. But the last insult was too much for his equanimity.

'This is getting beyond a joke!' he cried, and made as if he would personally chastise the nearest of the rioters.

His companion gripped his arm. 'Is it worth while, my friend?' he asked.

Leslie hesitated, and then laughed. 'Thanks; I dare say you're right. The old country has no need for martyrs while it has a good Foreign Office. To-morrow will bring an apology—and perhaps another indemnity. All the same,' he said, 'I don't know that I can stand much more of this. They're such a lot of unwashed ruffians!'

Luckily, his patience was put no further to the proof. They had already noticed an undersized, agile man in the front rank, conspicuous not less by a brilliant red scarf thrown over his shoulder than by his energy and the war-like manner in which he flourished his rifle. The fellow seemed to regard himself, and be regarded by the others, as a leader; and now he was to be heard alternately commanding and entreating his comrades to waste no more precious time there, but to follow him to the palace before the soldiers were upon them. Leslie was near enough to hear his reasoning: that the consulate could wait until the more important business (whatever it might be) was settled. In the end he had his way, and again the van of the procession started on its march. It was somewhat significant, however, that the previous impetuosity had given place to a steadier and more deliberate advance, as if the gravity of the enterprise had become better understood with the approach to their destination.

And still, to Leslie's surprise, the road remained clear. He could not fathom it. Why had the President made no attempt ere this to suppress a rising of which he could not be ignorant?

He had soon an answer to his question. In two minutes more they would reach the side street which led to the palace; insensibly the pace quickened; in the rear the shouting broke out anew; and then, led by the little man in the red scarf, the vanguard swung round the corner into full view of what awaited them. There was an instantaneous change. Leslie, on his part, had just a glimpse of cannon and soldiery before other matters claimed his attention. Plainly the sight not approve itself to the rioters, for a sudden shiver ran along their ranks, and they looked as if they would have given much to be able to stop or to retrace their steps. But by the impetus of those behind they were pressed forward until the little street was completely filled with the surging mob. It was every man for himself, and for the moment Leslie and his companion had quite sufficient to do in keeping together and preventing themselves from being knocked down. This, while all was confusion—

While those behind cried 'Forward,'

And those before cried 'Back'—

was surely the opportunity of the authorities. It was not

taken. When at last the mad jostling and pushing ceased the pair

were abreast of a large church—the church of Santa Catarina

de Sienna, Leslie learned afterwards—in the fourth or fifth

row of the crowd, and the crowd itself was confronting the

soldiers at a distance of not more than fifty yards.

A glance gave them their bearings. Leslie's friend freed his right hand, in which he held his revolver.

'Into the church when the firing begins!' he whispered.

Leslie nodded assent. 'If we can!' said he.

'We must! It's that—or go under!'

And in truth, on summing up, neither was too confident of his chances. On the one side, they were still hemmed in; on the other, the square in front of the palace was occupied by several battalions of infantry and one of cavalry (so called), while the street in which the assailants were massed was commanded by a pair of forty-pound cannon of the period of the Crimean war—doubtless the 'ancient guns' mentioned by Mr Isa B. Gray. Insignificant as the Salvatierran troops might be as troops, they were at least superior to a half-armed rabble; and, at the best, cannon-shot and bullets are no respecters of persons. One consolation there was—both parties seemed equally reluctant to begin hostilities. It was as if they were under some spell.

For fully a minute the strange scene was continued, and soldiers and citizens stared at each other, silent and inactive. Behind the former rose the grim pile of the national palace, one of the few imposing edifices in the capital, with walls of a tremendous thickness, and every window loopholed and heavily grated. Originally the college of the Holy Inquisition, it had latterly been in the occupation of the Society of Jesus, and, after the declaration of independence, had been chosen as the presidential residence on account of its strength and possibilities of defence. Opposite was the large church dedicated to Santa Catarina; and, for the rest, the square was flanked by two rows of dingy barracks, recent and infinitely more flimsy buildings.

At length the spell was broken. A mounted officer, after consulting with some of his comrades, rode forward alone towards the crowd; and the hum of amazement with which the action was greeted showed that this was an innovation in the established procedure of Salvatierran revolutions. What it portended remained to be seen.

THE officer pulled up ten yards or so from the front rank, and for a second smilingly surveyed the crowd.

'Who is he?' whispered Leslie to his companion.

'Romero!'

The attitude of the rioters (that alone) showed that he was no common messenger—that this was no ordinary occasion. He was a man of middle age, with the agile form and skin and features of an Indian, and nothing in his appearance to tell of Spanish blood except his moustache, and perhaps his quick, restless eyes. Yet he claimed descent from one of the Conquistadores—everybody does in Spanish America—and himself was indeed no other than General Barros Romero, Minister of War, and reputed to have an ambition to supplant President Alcazar in the highest office of the state.

When he spoke it was in the most conciliatory tones. 'And what is the meaning of this, my friends?' he asked.

The leader—he of the red scarf—stepped out, and in answer poured forth, with many gesticulations, a fiery denunciation of the administration's misdeeds, spoke of the increasing power of the foreigners: how they flourished while natives were starving, their perfidy and intention (well known to everybody) to annex the country, and so on, and so on; and, in conclusion, demanded either that the evil should cease, that there should be no more truckling to the faithless Anglo-Saxon, or that Alcazar should make place for wiser and better patriots. 'And if not—we are the people—it is for us to use our remedy!' he cried. He turned to his followers: 'You are ready, comrades—is it not so?'

The speech—it was really an eloquent speech, most eloquently punctuated by the exclamations of the crowd—was finished to quite a chorus of the old shouts. The rioters were ready; they had recovered voice and boldness under the intoxicating influence of their spokesman's oratory.

Romero listened attentively and without remark, and at the end raised his hand for quietness.

'So that is all, my children?' he inquired, in the same suave accent. 'Believe me, it is nothing. Listen to me!'—this as a clamour of dissent broke out. 'Am I known to you for a traitor? And if what you fear were true, believe that the first man in Salvatierra to join you, to help you, would be Juan Barros Romero! But I do not know it to be true; if it is, you have my word that I am ignorant of it. I cannot believe it'—here he was interrupted by some shouts of 'Death to Alcazar!' 'Down with the President!'—and continued quickly: 'Ah, you doubt the President—is it so, my friends? (Sí! Sí!) Listen to me again! What if I can prove that you are mistaken, that there has been some misunderstanding? Surely it is folly for patriots to kill each other when a minute may settle the matter. I will do this, then—remain quiet for a little while, and I will bring his Excellency the President here to speak with you face to face, to tell you himself that it is all a mistake, to show you that he has no thought of selling our country! I can trust you, señores,' he said, with his bravest air. 'I ask you to trust me. If I am wrong I give you full liberty to do with me as you please. I put myself freely in your hands.'

He did not await a reply—several cries of 'Viva Barros Romero!' there were, to be sure—but wheeled at once and rode to the great gateway of the palace. The mob, confounded by the strange turn events had taken, unable, apparently, to comprehend it, stood passive until he had dismounted and disappeared within. And amongst them, not the least astonished (to judge from his face) was Leslie Rutherford's new friend.

'This is beyond me,' he confessed. 'What's his game, I wonder? Where does the President come in? He has something up his sleeve—sí—but what? I don't understand!'

'Watch!' said the other.

Just as he spoke the next move was made. It was bold, unexpected—and successful. From the red-scarfed leader came a quick word of command; the crowd dashed forward, breaking away to this side and that to avoid the guns; for a few minutes our friends had to undergo a repetition of their former experience; and then they found themselves stranded near one of the cannon, with the rioters swarming in front of the palace, and all around and amongst the soldiers. Those, on their part, had done nothing; that they had not was, from their demeanour, not altogether against their inclination. How it was perhaps too late.

Leslie and his companion edged closer to the gun, round which the officer in charge—who was doubtless an adherent of Alcazar—had drawn his men in some order, swearing in an undertone the while. The Spaniard, recognising him as an acquaintance, greeted him sympathetically.

'You here, Don Gaspar? cried he, and expressed his surprise at seeing him in the midst of the turmoil. 'But you are everywhere! You are wonderful!'

'A mere accident, Señor Capitán. But tell me, why on earth didn't you clear the square?'

The officer shrugged his shoulders. 'A soldier must obey orders, señor,' he replied.

'Orders! You had orders not to fire?'

'On no account.'

'From whom? . . . Pardon me, but it seems strange. From his Excellency, I presume?'

'Oh no! The General had the supreme command to-day, and doubtless he has his reasons.'

'General Romero?'

'That is so, señor.'

Don Gaspar—as it appeared his Christian name was—whistled softly under his breath. 'I think I can see daylight now,' he confided to Leslie, reverting to English. 'It's a deep game that Romero's playing; but what I don't understand yet is the President's part. He's not usually a fool. However, another minute should bring the crisis,' he said; and with that he took the Englishman's arm to draw him away.

'Why, what now?' asked Leslie.

'Only a fancy. I am going to keep my eyes on Red Scarf,' answered the other.

They perceived the little leader, after a few seconds' search, standing in the midst of a group of his men right opposite the great gateway, between the soldiers and the palace. The intervening crowd, though still swaying hither and thither, was not so dense as to preclude them from approaching pretty closely; and they had just reached the outskirts of Red Scarf's circle, and (on Gaspar's initiative) were trying to edge still nearer, when a loud roar from the mob, dying gradually away in a hum of expectancy, warned them of a new development. They looked up. Above the gateway were two windows, and through one of these, at this moment, a man had stepped out upon the balcony commanding the square—a tall, soldierly man, with grizzled hair and moustache. He was in undress uniform, bareheaded, and apparently unattended.

'El Presidente!'

The words ran from mouth to mouth; there was an instant's stir as each individual in the square craned forward to gain a better view at his neighbour's expense; and then silence unbroken and complete. And President Alcazar, with one hand upon the stone balustrade, looked down upon the crowd of intermingled soldiers and citizens, and calmly bided his time. Whatever his other faults might he, he had the bearing of a brave man and a cool-headed soldier.

And at last he spoke.

'Señores!'

He got no further than that one word. The quietness had become profound as the clear and sonorous voice rang out over the square; but the President hesitated—his power of speech seemed to fail him—he stared straight down as if fascinated, incapable of using voice or limb. Almost involuntarily Leslie also dropped his eyes; and there, not five yards from him, he saw that a little circle had somehow been cleared, and that in the middle of it stood the man with the red scarf, rifle to shoulder. And even as he looked—before he could have raised a finger to prevent it—the catastrophe had befallen. There was the report of a single shot, and, without a groan, President Alcazar pitched forward on the balustrade—dead. The instigator and hero of one revolution was the first victim of another.

For a second, in common with those around, Leslie appeared scarcely to realise what had happened. Then he felt himself gripped by a mad, irresistible impulse. To this day he cannot account for his actions; all that he knows is that he was impelled to do it. He could not refuse. He did not try. Raising his revolver, he took a deliberate aim at the assassin—and fired. The man dropped.

It had been left to a stranger and an alien to send the murderer to his account with his crime still hot upon him.

Simultaneously with the second report the crowd found articulate voice and surged forward. But, before the puff of smoke had blown away, Leslie's arm was seized by his companion, and he was being haled through the breaking mass. It seemed, however, as if in the tension of the moment their share in the tragedy had altogether escaped notice. At the worst, nobody deemed it his duty to stop them. Doubtless the death of the President prevented interest in an event so comparatively insignificant as that of his assassin: it would not be until afterwards that the question would be asked how it had happened. Whether it would remain unanswered was for the future to decide. In the meantime luck was with them. After the passing of the first shock of stupefaction chaos prevailed. Populace and soldiers were pressing this way and that like sheep without a leader, no man knowing what to do, each man waiting for the next move. In this confusion it was easy for the fugitives to make their escape from the square without attracting undue attention. Leslie followed his guide with commendable docility, and at length was brought in safety to the lane running behind the church of Santa Catarina. It was deserted, and so they could now talk freely.

'By the skin of our teeth!' cried Gaspar, dancing a step or two. 'But what on earth induced you to do such a madcap thing, man? You might have got a dozen bullets in you for your pains!'

'I really can't say,' admitted Leslie. 'It was all done on the spur of the moment. I didn't think.'

'But I didn't know you cared a red cent whether Alcazar or Romero was uppermost.'

'I don't. It was all one to me. Only, I suppose, I have a natural dislike for cold-blooded murder. Most Scotsmen have; it's a part of our religion.'

'Knowing nothing of the merits of the case?'

'Wrong-doing can't excuse assassination.'

'Oh, don't let us argue about ethics. They are singly a question of nationality. There! listen to the result of the morning's work'—this as the echo of loud cheering came to their ears from the square. 'Le roi est mort; vive le roi! Exit Alcazar—enter Romero. They may change the figurehead every month, but it won't matter a cuartillo to the country except for the worse. More important just now, there is yourself to consider, Mr Rutherford. I have your name, you see.'

'And that reminds me that I haven't thanked you yet,' said Leslie, offering his hand.

The other took it frankly. 'You will thank me best by saying no more about such a trifling affair,' he replied. 'It was the least I could do for a countryman—partly at least.'

'A countryman! But'—

'My name, at your service, is Gaspar O'Driscoll,' said he, laughing at Leslie's expression of surprise.

'Then you are an Irishman?'

'My grandfather was. But our respective histories can wait until later. Just at present we have to consider the probable consequences of this escapade. There mayn't be much time to lose.'

'That's just what I want to find out,' interposed O'Driscoll quickly; 'and also, if you were seen, what is likely to happen. By good luck, I have friends at court—it will be easy to get the truth. And I have one or two points of my own to settle. For you, Mr Rutherford, the best plan will be to get back to the hotel as quickly as possible—I will put you on the way to do so—and stay indoors until I return. You have no objection?'

'None whatever. I am entirely in your hands.'

'Then that is a bargain. For my own part, I will promise to relieve your anxiety at the earliest moment. And now, if you are ready, we'll go on.'

O'Driscoll seemed to have a perfect familiarity with the city, for he led Leslie through quite a labyrinth of narrow streets and lanes before bringing him out finally in the Calle Mayor within a short distance of the hotel. There, repeating his warning to remain within for the present, he left him. Leslie walked slowly to the Casa Americana, cogitating over many things.

His host admitted him in person. From his first words it was evident that he had already heard the news, and was full of it—too full of it, fortunately for Leslie, to be particularly curious concerning his guest's adventures.

'Glad to see you back with a whole skin, sir!' he remarked pleasantly. 'You've had better luck than most. Guess it isn't often that we get our revolutions over so nicely.'

Leslie hinted that he had been a little disappointed.

'I dare say. But it looks as if we were civilising some, don't it? The bother here, you see, is to persuade our Presidents to demit office fast enough to give all the claimants a show. Well, sir, I must say I fancy Romero's way. Seems reasonable to begin at the top, and kill only one man instead of a hundred or two, as in the old days.'

'Then the affair's over, you think?'

'Trust Romero for that! If this is his shout, I'm rather Inclined to put my money on him. For one thing, he's shown originality—which means brains. Not that I can quite follow his play all through, but I suppose it's right. I'll take a walk round presently, when they've stopped making history, and ferret out the essential facts. It'll go hard if I don't.'

'Let me know the result,' said Leslie, moving away. The American's point of view, if he were serious, was rather interesting. Morality had certainly not much to do with it. But was the question of ethics, as O'Driscoll had said, one of nationality?

This reminded him of his late companion.

'By the way, Mr Gray,' he said, turning back, 'you have a gentleman called O'Driscoll staying here, I believe?'

'That's so, sir.'

'Who is he? Do you know anything about him? . . . I met him this morning,' he explained.

'I don't know much. Only that he's been staying here a week, and appears to find his way about. Hails Guatemala way, I'm told. The only thing Irish about him is his name. For the rest, he's a Don, and a good sort at that.'

Leslie ascended to the roof, which had been laid out with some taste. Taking a chair to the parapet, he sat down to watch the scene below. The street was again becoming animated; groups of people, deep in talk, were flocking in the direction of the Plaza; the women and Indians were reappearing in their holiday finery; and occasionally a more war-like company went past, shouting the name of General Barros Romero. Presently a patrol of cavalry turned up, and were heartily cheered. Mine host was evidently right: the revolution was over.

Confirmation came in the course of the forenoon from the same source. Somehow or other the landlord had managed to get his 'essential facts'—he was as fond of the phrase as if it were his own copyright—and from them he constructed a complete and cocksure history of the affair. The late President (according to his information) had recently effected a reconciliation with General Romero on the basis that the latter should succeed him on the expiry of his term of three years, that in the interval they should work together, and that at the end of it Romero should have the assistance of Alcazar's influence. Trusting in the War Minister's honour, therefore, the President had imagined that he could afford to disregard any hostile demonstration. That morning, being somewhat indisposed, he had left him in full command. The rest was easy. After his speech to the mob he had induced Alcazar—on the ground that the citizens merely wished his word that nothing derogatory to their sensitive amour propre was intended—to show himself on the balcony. One point was in dispute. The friends of Romero strenuously denied that the President's assassin was an accomplice, and had their story of private revenge to account for the incident. But nobody believed them—assuredly Mr Isa Gray did not. It was very significant, in his opinion, that the troops in the square should be those attached to Alcazar, while Romero's adherents were massed in readiness at various strategic spots. To Leslie the most remarkable aspect of the matter was this: nobody in Salvatierra seemed to think a penny the worse of Romero for his treachery.

He had an inquiry of his own to make. 'What of the man who shot down the assassin?' he asked.

'They're looking for him yet,' replied Isa. 'Some say it was an officer of Alcazar's party—some that Romero had fixed it up beforehand. It's a bit of a mystery.'

'And if he's caught?'

'Leave Romero to settle the matter quietly—with a file of his soldiers. It wouldn't do to have awkward questions cropping up the first day of office. The council's sitting just now at the palace, and the General has a regiment outside to make certain they vote the right way.'

And, sure enough, General Don Juan Barros Romero was, less than three hours later, proclaimed provisional President of the Republic of Salvatierra, in room of Don Calisto Alcazar, deceased. From his post on the roof of the Casa Americana, Leslie heard the salutes of the army and the loud acclamations of the mob, and formed his views concerning the democratic institutions of Central America accordingly.

As the hours passed, and still O'Driscoll failed to return, Leslie Rutherford's curiosity—he could hardly call it anxiety—regarding the upshot of his adventure grew rather more acute. So, after dinner, he betook himself again to his old position, for it was quieter on the roof than in the patio, where the foreign residents were wont to gather of a night for a gossip with stray visitors. There was also more to be seen—even if it were only, as now, the home-going of tipsy Indians or the sedate rejoicings of the mestizo. Apparently Alcazar was entirely forgotten. But his successor was too wise to leave anything to chance; his soldiers patrolled the streets continually, and gently hut firmly discountenanced the least inclination to form a crowd.

As Leslie's cigar burned down he fell into a half-dreamy state. It was his first visit to Central America, and yet much seemed familiar to him in a strange, half-forgotten way—as if in days long past he had been acquainted with the country and with its two races, conquerors and conquered. And, dreaming on, a very different scene from that in the city beneath—different also from the scene of the morning—rose before him. He saw a vast number of natives and white men, the latter clad in quaint, seventeenth-century costumes, fleeing in panic before a little company of ragged, bearded, fierce-eyed mariners; he heard the shrill cries of the one, the oaths and terrifying shouts and musketry-fire of the other; and in imagination he took part in the pursuit and carnage—he, a stalwart man with flaxen hair and beard. He could see it all: the plundering of churches and houses, the torturing of prisoners, and the trail of fire and smoke that rose from the sacked town as the little band of adventurers defiantly retreated, laden with booty. How real it was to him! An ancestor of his, as he well knew, had been one of that later brotherhood of buccaneers who had, for more than a decade, been the terror of the South seas—had captured fortified cities with a handful of daring men, had engaged the great war-vessels of Spain in mere cockle-shells, had earned the curses of all the Spanish colonies—themselves had indulged in wild orgies and deeds of cruelty and infamy almost incredible, and yet had performed miracles of bravery and endurance. Were these imaginings and recollections, so vivid and real to him, but the result of some strange hereditary freak? Or could the cause be traced to something else, still more strange and inexplicable?

Then the scene changed. It was the gray of the dawn; and the dreamer saw a tiny rocky islet, over which the tide was breaking in spray, and, clinging to it like limpets, the same hand of weather-beaten, truculent adventurers; and amongst them was again his alter ego, naked to the waist, his wet hair plastered to his face, encouraging his comrades with heartsome voice. And at that moment the sun rose out of the waters and showed a land-locked bay or estuary, the shores lined with people, a town nestling amongst its orange-groves not a gunshot from the little rock; and, surrounding the rock on every side, albeit at a respectful distance, a flotilla of boats full of armed men. And for a space the two parties stared at each other and bandied words, the assailants mocking yet afraid to strike, those at bay contemptuous and defiant. Then at length one boat darted forth from the circle, and in the bow stood a warrior in half-armour, and in form and countenance he was the counterpart—of whom but Don Gaspar O'Driscoll! But before the boat had gained the rock—while he, the flaxen-haired leader, was poising himself on the slippery foothold to meet the onset—there came, of a sudden, the report of a big gun from seaward. ...

Leslie's mind returned to the nineteenth century with something of a shock. For O'Driscoll himself was standing by his side, regarding him with a curious, puzzled expression in his eyes.

THE two looked at each other for a full minute, and then Leslie recollected himself.

'I beg your pardon,' he said. 'I didn't hear you coming up.'

O'Driscoll drew up a chair, and seated himself with his feet comfortably placed on the parapet. 'I've interrupted your nap, I'm afraid,' he said, smiling. 'My excuse must be that I have some good news for you.'

'You would be welcome in any case, Don Gaspar.' He passed over his cigar-case. 'Help yourself.'

'Thanks,' said O'Driscoll, choosing one and lighting it. 'I should apologise for keeping you on the rack so long, but I wished to make absolutely certain of my ground. Well, this is the net result of my investigation, Mr Rutherford: you needn't trouble yourself about this morning's work. There are all sorts of rumours about your identity—except the real one. That isn't even suspected. There's no reason why it should. You, for good reasons of your own, will hold your tongue about it as long as you 're here'—

'Or anywhere else,' said Leslie.

'That's for yourself, of course. Elsewhere it has merely the interest of a traveller's tale. As regards our friend Romero, it's not his policy to be too inquisitive. Indeed, from what can gather, you've done him an excellent turn. Quite sufficient of the plot has leaked out already for his comfort. It's whispered, for instance, that the assassin was no stranger to him—at all events, the fellow lived at a little village about half-a-dozen miles west of the city, and not two from Romero's hacienda, and was well known for a dead shot. With the information I have ferreted out, the whole intrigue is as plain as daylight;' and he went on to unfold a story that in its 'essential facts' differed very little from that told by the perspicacious Isa B. Gray. 'But enough of this, Mr Rutherford!' he concluded. 'You are right: it is pretty sordid, and must seem worse to you than to a native like myself. But if there is one thing I pride myself upon, it is that I have kept myself clear, in spite of every temptation to do otherwise, of Central American politics. I dare say, if I had cared, I might have been a President long ago. I preferred to remain a gentleman. ... To get back to business, however. You are safe enough here, as I've said; but in case of the unexpected that sometimes happens, I shouldn't advise you to stay too long in Salvatierra—especially as there's nothing to be seen or done. You are travelling for pleasure, I suppose?'

Leslie nodded. 'I have a fancy to cross the country to the Caribbean coast,' he said.

'From this point?'

'Well, not exactly,' said Leslie, with some hesitation. 'Farther south, perhaps. My idea, in fact, was to start from Fonseca Bay, and cut across to the Mosquito Reservation. But it's only an idea as yet.'

'Ah! ... It's a very difficult country, Mr Rutherford.'

'You know it?'

'Intimately. Indeed, there's scarcely a part of the continent, from Mexico to Chili, that I don't know well—and Nicaragua rather better than the rest. In this case, then, I may be able to be of some service to you. You see, Mr Rutherford, I have been a wanderer all my life. It's a legacy from my Irish ancestors, no doubt. Rut there!' he cried, throwing back his head, 'tell me, at first sight, to what nationality you would say I belonged.'

Leslie scrutinised the keen, dusky-skinned face, with its closely-cropped beard and lively eyes—a handsome and engaging face it was, frank and open in expression—and replied at once:

'Spanish—except for the eyes.'

'And these?'

'Undoubtedly Irish.'

O'Driscoll gave a hearty laugh. 'You're right, of course—so far. Nothing else?'

'Well, I can hardly say—unless (you'll forgive me) there's a strain of Indian blood to account for the darker tinge. But I dare say that is only the sun.'

'Not at all: you're right again. My blood is, I believe, half-Spanish, and for the rest Irish and Indian in equal degrees. Oh, you needn't have been afraid to mention it, Mr Rutherford. I am not in the least ashamed of my native ancestry. Why should I be, when I am probably descended on that side from a race that was highly civilised when my other ancestors—and yours—were little more than barbarians? They have fallen far, but what of that? The root is still there. Anyhow, you'll agree that it's a curious blend. And the result? I can give you my history in a few words: I'm a nomad. I was born in Guatemala—where I have still a small plantation, which affords me the means of a precarious livelihood—educated in the States and England, was for a few years in the army, and ever since I have roamed all over the continent, usually on other people's business. You may think it a wasted life, Mr Rutherford'—

Leslie shook his head.

'At the least, I have managed to enjoy it as well as most men—more so, perhaps—and in a humble way may have done a little good in my generation.'

'I have my own case as witness, Don Gaspar,' said Leslie cordially; 'although, to be candid, I can't see for what reason you bothered to interest yourself in me at all. Not many fellows would have run the risk. I shan't forget it in a hurry.'

'Oh, it was really from no motive of general benevolence. Shall I tell you the truth? When I spoke to you in the patio last night, your face struck me as being very familiar, but I could not for the life of me recall why. You and I had never met: I was sure of that. Well, it was the same this morning; I was haunted all day with a fancy that I couldn't trace, and it was not until I came up here, and—and, in fact,' he said, hunting for a phrase, 'had a good look at your face in repose—it wasn't until then that I suddenly remembered. It was the expression more than anything else that settled it, I think.'

Leslie reddened a little. 'I was dreaming at the time—not exactly asleep—a had habit I've got into,' he explained.

'Well, you reminded me of one I had met some years ago, in rather queer circumstances,' O'Driscoll went on, 'and so strongly that I'm only surprised I failed to see it sooner.'

'On this side?'

'Yes.'

'Then it must have been merely a chance resemblance,' said Leslie indifferently. 'I have no near relatives abroad—none at all, indeed, except my little half-brother, who is fifteen years younger than myself.'

'A chance resemblance—most certainly, considering the circumstances,' agreed the other. 'But, all the same, the resemblance is so close as to be quite remarkable. The more I think of it, the more I am staggered. If the type had been a common one, now—But it isn't, over here at least; and in this case, making allowance for the difference in sex'—

'It was a woman, then?'

'Didn't I say so? Yes, and a pretty one, too. What was more, she saved my life. And, barring the difference in age, one would assuredly have taken her for your twin-sister! Strange? Why, the whole affair was a mystery—it is a mystery to me to this day.' He mused for a little, puffing hard at his cigar. Then, tossing the stump over the parapet, he resumed: 'The circumstances, as I have said, were most peculiar in every respect. It was down in the back-country of Nicaragua'—

From Leslie came a quick exclamation. For the first time his interest was thoroughly roused.

'In Nicaragua,' repeated the other. 'But perhaps you would like to have the yarn from the beginning, Mr Rutherford? If it does no more, it will help to pass the half-hour until sunset.'

'By all means!' said Leslie. 'I should like nothing better.'

He settled himself easily in his chair, prepared to give the narrative his best attention. For he was now full of eager curiosity: some instinct told him that the story would he well worth hearing. And O'Driscoll, having fortified himself for the task by lighting another cigar, plunged at once into his yarn.

'When was it?' he began. 'Let me see—yes! it was four years ago this fall. You must know, Mr Rutherford, that I had a commission from a friend of mine, a German zoologist of good repute, to make a complete collection for him of the snakes of Central America, paying special regard to the scarcer varieties. It would not interest you to go into details; but there was one snake in particular of which he was anxious to secure a specimen. It was a variety of the corali, very venomous, and from a peculiar combination of colour on the back is commonly called the Purple Cross. By that name it is often mentioned in the ancient records of New Spain, and it seems to have been hunted down by the early settlers with unusual hatred. Perhaps for this reason it has become very scarce—indeed, it is popularly supposed to be extinct—and there are only two specimens of it in the museums of the world. So you may imagine my friend's desire—and my own—to settle the point one way or the other.

'I had started early in the year from Truxillo, on the Bay of Honduras, and had worked with moderate success across country to Jutecalpa. There I spent the rainy season arranging and classifying my collection—it was fairly good in all the ordinary varieties—and then sent it down to the coast under charge of one of my men. By the end of September I was ready to start again. I had two Indians with me, Ramon and Tomas, both very capable and intelligent men; and my purpose was now to round off my work by a thorough search for the scarcer and new varieties, and particularly for the wonderful snake of the Purple Cross, of which I had hitherto failed to find the least trace. With this end in view, I meant to cross into Nicaragua, and cut in a transverse direction from the Rio Coco to the Mosquito Territory—across a tract of country, in fact, that was unexplored and practically unknown.

'Well, the adventure happened about the middle of October. We had crossed the Coco a fortnight before, and for fully a week had left the inhabited parts behind us—had been feeling our way step by step through the jungle of a pathless, mountainous region, in which there was no sign of the presence of man. Except for certain indications, we might have been the first persons who had ever penetrated into these wilds. And these indications were few and harmless enough—in one place the ruins of an aqueduct, in another those of a great temple—only the ineffaceable marks of a long-forgotten civilisation that doubtless had once spread its network from one ocean to the other, and, having conquered Nature for a time, had again been conquered by her in turn. It was a hard life, but not unpleasant. Food was plentiful—and so were the snakes.' Breaking off: 'I don't know if you have ever tried the excitement of snake-hunting, Mr Rutherford?' he asked.

Leslie laughingly shook his head.

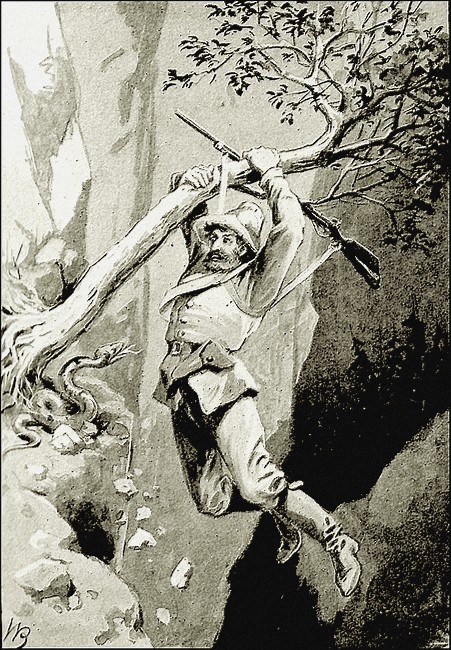

'Oh! it has a fascination of its own—especially when the odds are about level whether the man or the snake is to have the chance of striking first. Only, in this case it was rather disappointing. I had set my heart on the Purple Cross; all other varieties had lost their attractions for me. But no Purple Cross was to be seen. And when at last I did see it—but there! that brings me back to my yarn. One morning, then, I set out alone on a ramble. I left Tomas and Ramon in the camp, which had been fixed the previous evening in a little dale by the side of a stream; and as the country was becoming more and more broken and difficult, it was my intention to climb as high as I could get, and try to map out the easiest course. For two hours or so I steadily ascended, cutting my way through the tangle of undergrowth with my machete, and blazing the trees as I walked along—and always, of course, keeping my eyes wide open. And then, as luck would have it, I found my upward progress blocked by a steep ravine, wooded on both banks. I hesitated for a little whether to return or descend to the bottom in the forlorn hope of some discovery. The latter, by means of the trees, seemed a matter of possibility; and finally I decided to risk it. So I slung my Winchester across my back, and began to swing myself cautiously downward from tree to tree. At first everything went well. I had accomplished a good half of the descent in safety, and may have been tempted by my success to be less careful—at any rate, the accident took place. I must have missed my footing, or slipped in some fashion—I really can't explain how it was—but down I crashed through the bushes that grew outward from the rock, grabbing wildly at them as I fell. Then I was brought up again with a sudden jerk. Somehow or other my gun had caught between the trunk of a cedar sapling and one of the branches, and so had saved me—for the moment. Reaching up, I caught the trunk with my hands. But it was only when I glanced beneath that I realised the full peril of my situation. For here the side of the ravine shelved inwards, and below me was a clear drop of perhaps a hundred feet. If the sapling gave way—it was already swaying uncomfortably under my weight—or if my strength proved unequal to the task of pulling myself up, my chances of escaping death were of the smallest. And there I hung for a second, suspended between heaven and earth.

'Would the cedar hold? The whole question hinged upon that, and it must be settled first. I stole a half-fearful look at the roots of the sapling, and as I looked I perceived something which almost caused me to let go my grip of the tree in sheer terror. It was not that the roots were gradually being dragged from the cleft in the rock—though that, in all conscience, was serious enough—but that amongst them, scarcely two feet from my face, a pair of small, glittering eyes were fixed intently upon mine. God help me! I knew at once what it meant. I had no need to see the forked tongue, and the triangular-shaped head swaying this way and that as it moved nearer and nearer to me, and the dull metallic lustre of the skin—I had no need of these proofs to convince me of the terrible truth. I had disturbed the snake in its retreat; I was utterly powerless to protect myself against it; I could only watch my fate creeping nearer inch by inch—watch it as if fascinated. And yet, with death staring me in the face—you will hardly believe it, Mr Rutherford—I had the instinctive curiosity of the collector as to what branch of the species my enemy belonged. Then, as I discovered it, my head seemed to whirl round. I could have no doubt, the fact was so palpable—for there, on its back, were the two interwoven hands of dark purple, standing out distinct from the surrounding black and yellow and red—I could even trace the slight differences, in shape of the head and such-like, between it and the related genera—yes! I had found the Purple Cross at last!

I could only watch my fate creeping nearer inch by inch.

'Found it? I could have laughed aloud, Mr Rutherford, at the irony of the encounter. Rather, it had found me. The hunter had become the hunted; instead of the Purple Cross falling a victim to me, it was plain that I was marked out for its victim.

'All this, you must remember, had passed in less than a minute. The end must now he a matter of seconds. I could do nothing to avert it—do nothing at all but hang on, waiting for the reptile's forward dart. And the end did come, but not as I had expected. There was a sudden rending sound above me; the rocky side of the ravine flew upwards; my breath seemed to leave my body; I was conscious only that I was falling down—down—for miles and miles, as it appeared to me; and then—utter oblivion.

'I don't know how long I lay insensible—for many hours, I dare say. When at length I came to myself, it was to feel a sensation of sickening pain all down my left side. I was lying among the brushwood beneath a dwarf evergreen oak, through which I had doubtless crashed in my descent, and which by breaking the fall had perhaps saved my life. It had also, I feared, broken my arm and several of my ribs—indeed, the feeling was just as if the whole of my left side had been smashed with a hammer. The slightest movement caused me the most frightful agony. Yet I managed—how I cannot realise—to raise myself on my right hand to look around. The first object I saw was my rifle, with the leather sling hanging loose; the second was the sapling, lying a little beyond. The rifle wasn't three yards away, but it took me all my strength and resolution to crawl towards it. I thought I should faint again every moment. What I had first to do, however, was clear enough. My boys, as soon as they missed me, would have no difficulty in following my track to the edge of the ravine: it was my part to guide them to this spot. So (to be brief) I cleared a circle in the undergrowth, made a pile of the wood, and set it alight, fired my repeater thrice in rapid succession, waited a minute, and fired again; and then, leaving the rest to the smoke and the signal, swooned right away. But as to the pain which I had endured while I was doing this—why, to this day I cannot think of it without shuddering, and when I dream of it at nights I wake up with, the sweat running from every pore in my body.'

Here O'Driscoll stopped; and at that moment, in truth, the sweat was standing in great heads on his forehead at the mere recollection. His listener was scarcely less moved. He had held his breath in excitement as the story culminated; it was thrilling in itself, and, helped out by the expressive voice and dramatic gestures of the narrator, it had assuredly lost nothing in the telling. For the man was a born artist; he had the power to bring the scene before one with a vividness as of actual experience, and in this case with some of the pain as well. Leslie felt both.

'It must have been terrible,' he said, shivering.

Don Gaspar admitted that he should not care to go through it all a second time. 'And the worst was still to come,' he added, 'though, luckily for me, I was too bad to realise it fully. What I did realise was, Heaven knows, quite sufficient.'

FOR a few minutes the two men smoked on in silence. Below, in the city, the near approach of evening was heralded by the flickering glimmer of the oil-lamps in the Calle Mayor; the hum of the populace was dying down; the sun had already disappeared from sight behind the houses; but there, on the roof of the hotel, it was still daylight. In a little the night would have fallen.

'And the story?' suggested Leslie at last.

O'Driscoll started. 'You'll excuse me, Mr Rutherford,' he said, with contrition; 'but in going over these days again I'm afraid I forgot you altogether. Where was I? Oh yes! . . . I was brought out of my second faint by a recurrence of the intolerable pain in my side. It couldn't have been long afterwards, for my fire was still smoking. I had been pulled roughly to my feet by a couple of men, who were now supporting me—the agony of the action must have roused me—and perhaps a dozen others were standing around, staring at me curiously. The strangers were certainly Indians, but of a tribe unknown to me, being of a finer physique than most, somewhat lighter in complexion, and dressed differently from any whom I had ever seen. Then, looking down, I noticed Ramon and Tomas lying bound on the earth at my feet. What could it mean? To be made prisoners by the docile natives, in this latter end of the nineteenth century: surely it was beyond the range of possibility! They were jabbering away amongst themselves; and although my acquaintance with the various dialects of the isthmus is fairly extensive, I could not recognise a single word of their talk. But I hadn't much opportunity for investigation. Following a sudden order from one of the bystanders, my guards started to drag me forward, ignorant or heedless of the torture to me. I bore it for a second, and then was forced to cry out; the next, I had mercifully succumbed once more.

'My recollections of the next stage are of the haziest kind. I must have been unconscious most of the time. But in a dim, far-off way I can recall two awakenings—one in daylight, the other when it was dark—and in both the outstanding impression was that of being carried in a litter of some sort, over rough ground, and of my own sufferings as the result of the jolting. As to the distance, and the nature of the country, and the number of hours or days occupied in the journey, frankly, Mr Rutherford, I can tell you nothing whatever. It is all a blank to me.

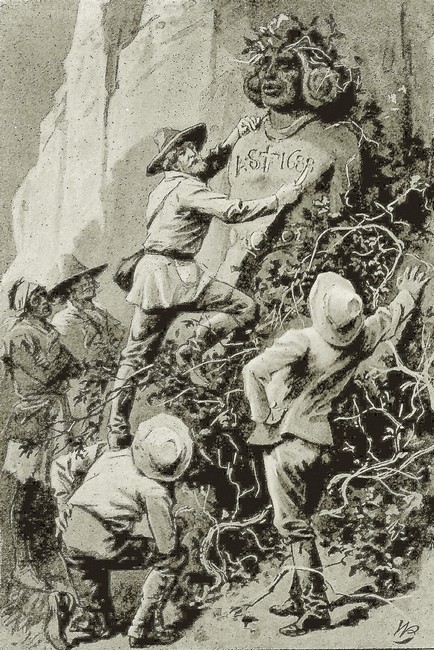

'Let me hurry on. I can understand that you're growing impatient for the appearance of the lady, but of course I must take the events in the proper order. The strangest part is now to come; and, to enable you to follow it—to form a right judgment upon it—I must trouble you for another minute with my own sensations. As I have said, I don't know how long I was in this state of insensibility. Curiously enough, the first of my senses to recover seemed—to be that of smell; for, before anything else, I think I became conscious of a pungent, aromatic odour, not unlike incense. Then I was aware of the sound of music, of people singing to the accompaniment of instruments, in which the drum predominated; but at first it appeared distant. So soothing was the influence of these combined that for a little I lay in a sort of dream. I did not feel the pain of my injuries; I had no curiosity; and in fact, at this moment and throughout all the wonderful doings which ensued, I must have been light-headed—conscious, but little more. And at last my eyes began to see, or at least to convey to my brain some idea of what they saw. True, it was only the ruin of a high roof of gray stone, through which the blue sky was visible and the sunshine was striking in vertical lines; and about the same time I recognised that the music was really at my ears. Then my mind resumed its work. Slowly, and with an effort, I realised the facts: that I was lying prone upon my back, that I was in a building of some kind, that there were many people around. I struggled into a sitting posture, careless of the renewed pain in my shoulder and side. And this, to be brief, is what I discovered concerning my position. I was in the middle of a vast, bare hall; in front of me, at no great distance, a crowd of many hundreds of Indians, men and women, were standing in a semicircle round a fire, from which rose clouds of aromatic smoke; and behind them, towering above them, was a colossal stone statue or idol in the image of a man. The idol fascinated me. It was rudely done; but somehow the sculptor had managed to give the face an expression of frightful, diabolical cruelty. It seemed to be looking straight at me, and a shiver of downright fear ran up the small of my back. Dragging my eyes from it, I was able to take in the other details of the scene—the light complexions (comparatively speaking) of the Indians, their strange dress, the drum-like instruments to which they accompanied their chant, their absorption in the music. And it was a wonderful scene, Mr Rutherford: I can see it all, but I despair of bringing it before anybody in an adequate way.'

'I think I can see it too,' said Leslie Rutherford slowly. His voice had a queer impersonal ring about it, just as if he were trying to speak in the half-remembered tones of another; but the darkness had now settled down, and O'Driscoll could not watch the expression on his countenance. 'Listen! It is a long, rectangular building, partly in ruins; there are no windows on the side-walls, which are ornamented with curious sculptures of men and beasts; and the floor-space is quite bare, excepting only for the statue and a row of stone slabs facing it'—

'Eh?' O'Driscoll was startled into the exclamation.

'And at each end,' Leslie went on, unheeding, 'there is a great archway, and through the eastern one you have a view across a stretch of green to a lake—and the lake is spanned by a broad causeway or bridge—and on the other side the ground rises in successive terraces, where huge buildings alternate with clumps of verdure half-way to the summit of a peculiar-looking, double-coned hill—and over-topping it all, catching the eye at once, is a pyramidal-shaped edifice that stands isolated above the other structures, and the apex of it seems to be of some burnished metal, for it throws back the rays of the sun. . . . And that is all, Don Gaspar; my imagination can carry me no further,' he concluded, breaking off rather suddenly.

But O'Driscoll had jumped to his feet, and was pacing to and fro on the roof in manifest agitation of spirit.

'Imagination!' he cried, stopping in front of the other. 'No! no! You have been there, Mr Rutherford; you must have been there! It is the very scene—Dios mío! I had almost forgotten the lake and the pyramid and the ruins on the hillside; now I remember them! and the stone slabs—oh! it is impossible that it can be imagination. Tell me, how do you know it all?'

Leslie did not reply for a moment. Then: 'Really, I can hardly say,' he acknowledged. 'I have never been there, of course; and unless I have read the description somewhere'—

'That, too, is impossible!' interrupted O'Driscoll, with conviction.

'Perhaps. If I did, I don't remember of it. And yet the place is before me, as clearly as if I had seen it with these eyes. That is what I feel; but how to explain it, more especially as the description seems to be accurate—well,' he said, 'I have one theory to account for it, and even that is too far-fetched—too inconceivable, in a word—for ordinary mortals to swallow. What is it? I'm afraid it would take too long to tell. Besides, you have your story to finish; I've interrupted you too often already. Pray, go on, Don Gaspar; afterwards, if you like, we can discuss the other matter.'

Don Gaspar paid no attention. He had not yet succeeded in overcoming his amazement, and for a little longer he paced the roof, revealing by his ejaculations in Spanish and English that his companion's strange interposition was more in his mind than his own adventures.

'It is altogether beyond me!' he cried at last.

'And me also—barring the theory,' said Leslie, laughing. 'But won't you take pity on me, señor? I'm dying to hear about my mysterious savage twin-sister.'

Don Gaspar sat down again, and complied; yet not, it was evident, without a great effort of will. 'It is marvellous!' he repeated, for perhaps the twentieth time. 'These stone slabs alone, Mr Rutherford—why, on my word, it was on one of those very stone slabs that I was lying at that moment! I discovered the fact as I turned away my eyes from the crowd. There was a row of five or six of them in all, raised four feet or so from the floor, each long and broad enough to hold a man, and each with a shallow depression extending from the sides to the middle; and it was on the one at the extreme left that I lay. At the same instant I discovered also that my two servants were on the adjoining tables, Tomas next to me, Ramon on the third. Both were still bound hands and feet with lianas—those, I suppose, with which they had been tied on their capture. My own limbs were free, thanks, no doubt, to my helpless condition. I realised all this; then my eyes caught those of Tomas. Never to my dying day shall I forget the look of abject, unutterable terror on the poor fellow's face—he was a good lad, who had served me well and faithfully—never can I forget his appealing, hopeless cry when he saw that I recognised him. It rings in my ears now:

'"Save me, patron! Par el amor de Dios—save me! save me!"

'"What is it, Tomas?' I whispered back. 'Where are we? What has happened?"

'But he seemed distracted, able only to repeat his cry: "Save me, señor! They are savages—man-eaters—they are going to kill us—for the love of the Holy Virgin, save me!" His voice rose to a scream; there was an answering cry from Ramon. For myself, I had a stupid inclination to laugh. Somehow, all my fear was gone; I was indifferent: the fever was in my head, and I had no sense of the gravity of our peril. Then a sudden weakness came over me, and I fell back. Presently the singing stopped, and I looked up again. An Indian was standing over me, impassive as a statue; he had a long machete in his hand; his arm was raised. Suddenly the music broke out again, and again stopped; then there was a frightful scream—it was in Ramon's voice—and in a kind of dream I heard a clamour of sounds—a louder outburst of the music, and amidst it Tomas's harrowing tones as he alternately plead for mercy and pattered incoherent prayers to his saints. The sickening horror of it! The scene was repeated: this time the cry was from Tomas himself. I knew what had taken place as surely as if I had seen it: that my poor servants had been butchered in cold blood. And my own turn was next. I closed my eyes, awaiting the stroke; I could do nothing to prevent it: I am not certain that I wished. If only it came quickly!

'A full minute passed—you may imagine the fearful suspense—then another, and I was aware of a low hum as of surprise from the crowd. What could it be? I wondered. I could endure it no longer. The executioner still stood above me, with his arm upraised, but his attention was elsewhere. I sat up. The cause of my reprieve was now evident. A new-comer had arrived upon the stage, and one plainly of some importance, for the semicircle of Indians had parted in two, leaving a clear lane from the great archway, and, men and women alike, they were bending nearly to the ground in obeisance to a woman—a young woman—who was slowly advancing up the hall, followed at a distance by a little group of attendants. At first I distrusted the evidence of my eyes. In appearance, in demeanour, the girl—her age could have been no more that sixteen or seventeen—was a European: the mere fact of her presence there amongst that mob of bloodthirsty Indians was astounding. She was so different from them in every essential: like an angel amongst savages. Yet there, beyond all doubt, she was. How can I describe her? It can only be in conventional terms, for no words can do her justice. She was clad in a long robe of some white stuff, caught at the waist and shoulder by slim golden ornaments; her arms and head were bare; she was above the average height, and carried herself like a queen. Her whole appearance, as I have said, was that of a European. Her skin was no darker than a pure-bred Spaniard's, and in everything else—features and eyes and hair—she looked every inch the part. The hair of a flaxen colour, with just a touch of gold in it; the blue eyes; the broad, low brow, the long and straight nose, the short upper lip, the well-rounded chin—but to you, Mr Rutherford, I need detail these no farther. Allowing for the differences of sex, you have only to glance in a mirror to see them all. Her expression, too—it was the recollection of that, as I've told you, which reminded me of her when I noticed a similar one on your face. For the rest, enough that I thought her the loveliest woman I had ever seen. No, that isn't meant for flattery, delicately applied—it is the bald truth. I saw her twice, and no more. And I think so still.'

'Go on!' said Leslie breathlessly.

'Well, I didn't speculate much about the effect of her arrival upon my own fate. For one thing, I hadn't the time to recover from my astonishment before it was over. Having reached the end of the lane, she turned at once and addressed the crowd; and although, of course, I could not follow the remarks, it was pretty obvious from her tone that she was lecturing them very heartily. At least they attempted no reply; and presently, turning again, she came straight towards me. She threw a single glance at the horrible sight on the neighbouring slabs, and shuddered; and then she stopped in front of mine. For a moment we looked at each other. It did not strike me until afterwards that, to put it mildly, I could scarcely have made the best show possible; but just then I saw nothing except the womanly expression of pity on her face; and when she spoke—very slowly and distinctly—the same quality was (or so I believed) perceptible in her voice. For me, I could only shake my head. I understood not a word. Then she gave a quick command, and the three executioners—two of them with their blood-stained swords—marched off at the double-quick; another, and immediately four men advanced from the crowd, and under her directions raised me very gently from the slab. And with that the reaction came. Throughout the whole adventure it had been my bad luck to faint away at the most inopportune times. Now I did so again.

'I have little more to tell. The fever must have gripped me almost at once. One more recollection of her I have, indeed—not so distinct as the other, but to me more precious. The scene is all jumbled in my head; I had a sense of great relief and freedom from pain, of the scent of flowers, of people moving noiselessly about; but the outstanding impression was that of the girl herself bending over me, with her cool hand on my brow—a ministering angel, if ever there was one. And it is so that I like to recall her. She had certainly saved my life in the temple; I have not the least doubt myself that she saved it a second time during my illness. But that illness now closed down upon me. The rest is darkness.

'And there for me, as far as she was concerned, the experience ended. For when I finally struggled back to consciousness, I was an inmate of a miserable Indian hut near the mouth of a small river on the Mosquito coast, about fifty miles to the south of Cape Gracias à Dios. From the natives, who did what they could for me, I learned that I had been found one morning three or four days previously, lying on the bank, my rifle beside me, raving in high fever. There was no canoe, no indication how I had got there. And, by the lowest calculation, I was at least a hundred miles from the spot at which I had met my accident—a hundred miles, mind you, of country unknown and unexplored, and supposed to be practically impassable! More than that, it was (as I discovered afterwards) nearly three months since that event—was, in fact, well on in January of the following year. I was still as weak as water; but, strangely enough, my arm and side were quite healed, and from various indications it was quite evident that the injuries had been treated with some skill. It was another month before I was able to travel, and during that time the friendly Mosquitoes did everything in their power—it wasn't much—to make me comfortable. At length, with their assistance, I managed to reach Blewfields, where I was able to repay them to some extent for their kindness. Thence I went on to Greytown, and then by the San Juan and the Lakes to Granada, and so by slow stages home to Guatemala. My health was shattered: it was long months before I was completely myself. At first I told my story to many people, but it was invariably received with so much polite disbelief—put down, by the most charitable, as a mere hallucination of the fever—that I soon learned to keep it to myself. In my own mind, I have never wavered for an instant. There are points, as you have heard, that cannot be explained by any such theory. There are others, of course—a score of others—that want clearing up. And to settle these, I have always intended to make another journey across country, but hitherto have been prevented by a series of accidents which it wouldn't interest you to detail. But I still intend to do it, whatever the trouble and dangers—and as early as I possibly can. . . . And that, Mr Rutherford,' he concluded, 'is the true yarn of my adventure. It is strange, in some respects almost incredible; I acknowledge that; and I don't know that I have the right to ask you, a foreigner, to believe what my countrymen won't. At the least, you may have found it amusing.'

'I believe every word of it, Don Gaspar,' said Leslie, speaking with unusual seriousness. 'And I will tell you why. All the circumstances of our meeting—our presence in this city at the same time, the revolution, your recognition of me—all these go to form a wonderful coincidence. Either that, or Providence has designedly brought us together—perhaps the only men in the world who can help each other in a certain enterprise. For I think I can give you the clue to the mysterious points in your story; I think you have found the clue to mine. Not my own exactly, but one in which I am concerned, although it began more than two centuries ago. But first,' said he, 'I have a question for you. There is nothing else that you can remember about this strange girl—nothing that struck you in particular?'

O'Driscoll thought not. 'But wait!' he cried, after a second's deliberation. 'Did I mention the ring?'

'The ring? No!'

'I can't understand why I forgot it—it was perhaps as strange as anything. She wore it on the thumb of her right hand: a man's signet ring of heavy gold, by the shape and appearance very ancient, and most undoubtedly of European design, for the seal was a crest—an heraldic animal of some kind. I am too ignorant of those things to say what.'