"The Carson Loan Mystery." Cover design by Terry Walker©2017

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

"The Carson Loan Mystery." Cover design by Terry Walker©2017

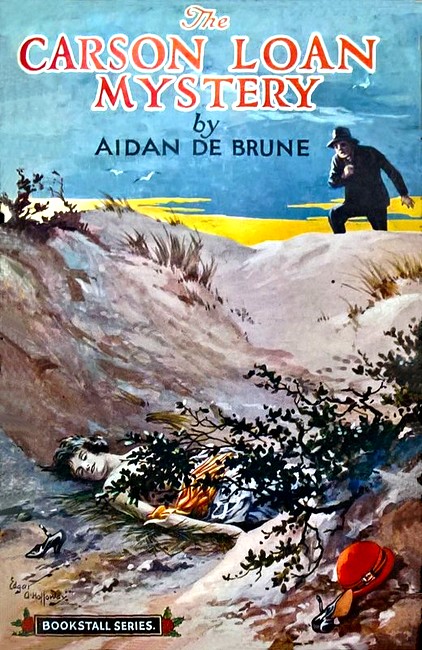

"The Carson Loan Mystery,"

The NSW Bookstall Co. Limited, Sydney, Australia, 1926

THIS book is a product of a collaborative effort undertaken by Project Gutenberg Australia, Roy Glashan's Library and the bibliophile Terry Walker to collect, edit and publish the works of Aidan de Brune, a colourful and prolific Australian writer whose opus is well worth saving from oblivion.

"The Carson Loan Mystery" by Aidan de Brune is an addition to the Bookstall series, published by the N.S.W. Bookstall, Co., Ltd. As its title indicates, the novel is one of mystery, and deals with complications arising out of a loan of a large sum of money. The locale of the story is Sydney, and introduces many places familiar to those who have visited that capital."

—The Sunday Times, Perth, 27 March 1927.

An entertaining book for a couple of autumn evenings has been added to the Bookstall series, in the story with the above title. It is by Aidan de Brune, who... writes a most interesting story, concerned with the unscrupulous activities of several more or less shady characters in the multi-phased life of Sydney. The author knows Sydney, and also knows passing well the procedure in police and detective departments, besides having a passing acquaintance with newspaper staff feuds. The result is a smart novel, brightly written.

—The Gosford Times and Wyong District Advocate, 17 March 1927.

Frontispiece

"I'm the Tiger Lily, an' don't yer forget it. Naw, what d'yer want wi' me?"

"IT'S the queerest bit o' business I've seen."

Constable Nicholls was standing on the sandhills that border Little Bay, looking down into a shallow depression, in which lay the body of a naked woman. His large, red, good-humoured face wore an expression of almost comical dismay, as he leisurely scratched his thinly covered head with the peak of his official cap. Nicholls was not recognised in the New South Wales Police Force for his readiness to grasp a situation.

The woman had been about forty-five years of age. The features, once possessing a measure of beauty, had been coarsened and lined by a life of dissipation and want. The hair, roughly bobbed, was sprinkled with grey, and the liberally applied cosmetics had formed grotesque channels through the action of the heavy morning dew.

The woman lay on her back, her knees slightly drawn up. Under her had been strewn a rough bed of rushes, and, for some reason, the murderer had carefully folded and placed across the lower part of the body the clothes the woman had worn in life. Her face was placid, but for a queer twisted smile that curved the thin bloodless lips.

Nicholls looked at his watch. It was just five o'clock, and the first rays of the morning sun were lifting above the eastern horizon. A haze, almost thick enough to be called a fog, hung over the sandhills, giving the surroundings an effect of long distances. About three hundred yards north of where the constable stood the waters of the bay shone intermittently through the haze.

"They should be here, soon," commented Nicholls, stowing in an inner pocket the massive silver timepiece he had consulted. Then he turned to his companion, a long lanky youth of about seventeen years of age: "There's no work for you t'day, m'lad."

Archie Clarke nodded vacantly, and continued to stare down at the woman's body.

"She was like that when I found her," he said, hesitatingly.

"Likely, lad," replied Nicholls, magisterially, "Them as 'as been treated as she 'as don't move much after. Leastways, not till we moves 'em."

"I didn't touch 'er," continued the youth. "'Struth, I didn't. She's just as I told you I found 'er. I was comin' across that 'ere path, same as I've done every day this year past, to go to work, when I seed 'er."

"Is it more'n a year, or less'n a year, you've come across 'ere'?" The constable stuck his hands on his hips and frowned down on his companion. "You've got ter be exact, y' know, in these cases."

Archie looked puzzled.

"You might remember later on," added Nicholls, shaking his head, sadly. "Go on wi' yer tale, Archie. It ain't many as remembers th' exact particulars when face ter face wi' th' lor. Yer 'ave ter be trained to it."

"I've told you all I know about it, Mr. Nicholls," protested the youth.

"So yer 'ave, an' I writ it all down," replied the constable, "But it won't 'urt yer t' say it all over agen. You'll tell a better story when yer comes affore th' magistrate. I does it m'self. I goes over an' over it agen, an' agen, an' adds a bit 'ere, an' leaves out a bit there, as don't count. Y' don't know wot you're up agenst. If yer tells it wrong they may even take yer up for th' murder. They've done it affore, an' they'll do it agen, I can tell yer."

Nicholls paused, and looked down at his companion, now duly impressed.

"You're a decent lad, Archie Clarke. I've 'ad me eye on yer fer some time, you livin', so t' speak, in my district. An' I makes no complaint, tho' there's them as might seein' th' row you an' your mates make in Main Street ov a Friday night."

"We don't do no 'arm, Mr. Nicholls," argued Archie.

"P'haps not. So I gives yer a word of advice." Nicholls spoke authoritatively. "You tells your tale as you told it me, an' as I writ it down, an' don't yer make no h'errors. When we lays 'ands on th' bloke as done this, you tells your tale to th' Judge and jury—an' th' Loord 'ave mercy on yer soul."

"All right, Mr. Nicholls," answered Archie cheerfully. "They won't do anythin' to me, will they? I couldn't 'elp findin' er."

"Not if yer do as I ses," replied the constable. "An' there's one thin' more. Beware of them noospaper blokes. They'll be all over yer, tellin' yer wot a fine feller y'are, an' ow yer saved the country by findin' this 'ere female. Then, they'll take yer words an' cut an' twist 'em, an' turn 'em up-side-down an' yer won't know wot yer sed, an' then th' H'Inspector 'll call yer a fool, an' worse, an'—Yes, sir."

The constable sprang to attention as a tall form loomed out of the mist.

"There you are, Nicholls. Had a devil of a time getting here. Ah, there she is. Bad case, eh!"

"Very bad, sir. It's—murder," announced Nicholls pompously. "This 'ere's the principal witness, sir."

Inspector Richards looked at Archie Clarke, casually; then nodded.

"I'll hear what you have to say presently, my lad," he said, brusquely. "You've not touched the body, constable?"

"No one's been down there, sir, 'cept th' murderers. Clarke and I 'ave stood up 'ere ever since 'e fetched me."

With a nod of approval the Inspector walked down into the hollow and stood beside the corpse. Bending down he looked, earnestly, into the still face. Then, silently and methodically, be circled the body, carefully examining the ground.

"Humph!" Richards climbed on to the high ground, and stood beside the constable and youth. "You don't seem to have done any damage, Nicholls. She's dead, so we'll leave things as they are until the doctor and others arrive. I'm a few minutes ahead of them."

The Inspector looked down on the dead body, thoughtfully, for a few seconds. Then he turned briskly to the boy.

"So you are the boy who found her? What's your name?"

"Archie Clarke, sir."

"Where do you live, Clarke?"

"14 Milton Street, Maroubra, sir."

"Good. Now, how did you come to find the body? Speak up, smartly."

"I've got it all writ down, sir," interposed Nicholls, importantly.

"Then keep it so," snapped Richards. "We may want it later, but I'll get my facts first-hand. Now, Clarke, tell your story."

The constable stepped back, somewhat abashed. Archie Clarke hesitated.

"Get on with it, boy. You say you live at Maroubra. Well, how did you come to be on these sandhills so early in the morning?"

"I come across 'ere every morning', sir."

"What for?"

"To go to work."

"Early or late, this morning?"

"'Bout usual time, sir. I leaves 'ome about 'arf-past three an' gets there about four. I shall be late this mornin'."

"Afraid you will." Richards smiled, grimly.

"What's your job, Archie?"

"Milk round, Walker's Dairy, Randwick. Can I go now? Mr. Walker told me not to be long."

"Not unless you take Constable Nicholls with you, my lad. Do you think he would look pretty on the cart. No, I can see you don't. For the present you'd better stick close to the constable. Later, you may be able to go home or go to work, just as you please. Now, lets get your tale straight. Your name is Archie Clarke; you live at Maroubra, and you work for Mr. Walker, a dairyman, at Randwick. Then you said you come across this track every morning between three-thirty and four o'clock. That right?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then how did you come to see this woman? You can't see into this hollow from that track?"

"I wasn't walkin' right on th' track sir," replied the youth. "Just alongside, an' I saw some ov them things flutterin'. So I came over to see what it was—an' then I saw 'er."

The youth hesitated.

"Go ahead, Archie," urged the Inspector kindly. "What did you do then?"

"Ran all the way to Mr. Walker's, an' told 'im."

"And then?"

"Mr. Walker rang up the police station an' told 'em. Then, when Mr. Nicholls came, he told me to bring 'im 'ere. An' I did."

"That lets you out," observed the Inspector. "Wait a moment."

Richards left the pair and walked over to the track. There he carefully scanned the ground, walking along the pad a considerable distance both ways.

"Quite right, Archie," he said, when he returned to the edge of the hollow. "When I've heard the constable's report I may be able to indulge your secret passion for work. Yes, constable."

"Robert Nicholls, constable, number 41,593, stationed at Randwick, sir." Nicholls drew himself up erect, and spoke in a severely official voice. "At 4.10 a.m. received instructions from Sergeant Appleby to go to Mr. Walker, a dairyman, at Randwick, in reference to a case of suspected murder. At Mr. Walker's saw witness, Archie Clarke, who stated he had found the dead body of a woman on the sandhills near Little Bay. I accompanied him to the spot indicated and investigated, sir."

"Your investigations taking the form of mounting guard," commented Richards, drily. "I admire your discretion, constable."

"I was examining the witness, sir." Nicholls assumed an air of injured rectitude. "Then I was—"

"Perhaps it is as well I arrived before the examination concluded," observed the Inspector, grimly. "There seems to be few clues as it is, and if you had commenced tramping the ground down there—"

"What's that?" Archie Clarke was pointing over the sandhills to where the indistinct form of a man clad in a long white coat loomed out of the mist. He was acting in a very peculiar manner, stooping low, and dodging from bush to bush.

"Who's that?" shouted Nicholls, importantly.

The man halted, and dropped behind a clump of bushes. For some minutes the officers strained their eyes to see where he had gone to. Presently Clarke touched the Inspector on the arm, and pointed well away to the right. Richards caught a glimpse of a white coat vanishing around a clump of rushes. Beckoning to his companions, Richards led the way towards where the man had disappeared. Again Clarke pointed to the right. The man was evidently circling to get to the place where the woman's body lay.

"Halt, or I fire," Nicholls rushed forward, tugging at his revolver.

The man gave a swift look round and then started to run, curving around in the direction of Randwick.

"You damned fool," muttered Richards, angrily. "If you had kept your ugly mouth shut in the first place he would have walked into our arms. Come on, he's getting away from us."

It was heavy running on the loose sand. Nicholls plodded heavily along in the rear, groaning and spluttering. Clarke, younger and lighter, drew steadily ahead, and noticeably gained on the fugitive.

"There's a road over there," panted Nicholls, heavily.

"What's the good of that?" shouted the Inspector, testily. "A road's not a wall. It's up to that boy. He can run."

The fugitive breasted a steep sandhill that slowed the pursuing officers to a walk. Archie Clarke made up a lot of ground on the climb, and was only half a dozen yards in the rear when the man reached the summit. There, the man turned and waved a derisive farewell to his pursuers, and slid out of sight.

The Inspector struggled gamely up the loose, shifting sand, confident that when he reached the top he would have his quarry under observation into the town. Once there he halted and looked around. The man had disappeared.

At the feet of the officer lay Archie Clarke, insensible, and bleeding from an ugly head wound.

RUGH THORNTON tilted his chair back and hoisted his feet on to his desk. Business was slack, and the afternoon's Star interesting.

Twelve month's previous Rugh had been a member of the Star's staff. Investigations he had made into the activities of certain assurance company-promoters had attracted the attention of leading men of the assurance world. He had received an offer from a syndicate of the leading assurance companies to enter their employ and carry on his investigation work, and had promptly accepted. His work was interesting. Every new assurance company came under his review, and his keen insight into their methods and objects, as well as into the history of the men behind them, had resulted in making New South Wales unsafe for the unscrupulous insurance company promoter, and wild-cat companies.

The Star's account of the finding of a woman's naked body on the sandhills around Little Bay was extremely brief and pointless. Rugh was puzzled, for the Star's criminal investigator, Harry Sutherland, was a keen and clever journalist, usually well ahead of official investigations.

In the matter of the Little Bay Mystery the Star had taken a scrupulously official viewpoint. No attempt had been made at an independent newspaper investigation, and the impression conveyed was that the Little Bay Murder was one of the sordid crimes common to large cities.

The well-trained brain of the assurance investigator refused to consider the murder in the aspect presented by the Star report. There were many unexplained points that puzzled him.

The woman's body had been stripped. It was not uncommon for murderers to strip their victims in the search for valuables of one kind or another. Yet the police were confident the woman was one of the "lost sisters" of the city, and unlikely to have anything of value on her person.

Again, while the body had been stripped, the clothes had not been thrown about haphazard, but had been carefully folded and placed on the body. This, alone, presented a problem of an original character. Few murderers are sufficiently cool-headed to spare time and thought for such actions.

The man seen by the police in the vicinity of the dead woman, almost immediately after the discovery of the body, presented another problem. If the woman was one of the "lost sisters" of the city, and had been murdered by this man, why should he hang around the spot? Murderers usually place a considerable distance between themselves and their crimes, as quickly as possible.

While the official report strove to show the Little Bay murder as a common, sordid crime, it could not conceal the unusual nature of the surroundings. The report laid great stress on the doctor's report that the woman had been kicked to death, as supporting their theory of thug-murder, but neglected to explain the stripping of the body, the careful disposal of the clothes, and the return of the supposed murderer to the scene of his crime.

Rugh laid the newspaper aside with an exclamation of displeasure. It was a mystery that would have appealed to him during his journalistic career. He would have thrown himself, heart and soul, into the hunt, combing Sydney's underworld from end to end.

Those days had passed. The greater tragedies of the city were not for him. He had his work in the protection of a branch of the city's commerce. In the hunt for the murderer in the Little Bay mystery he was now but one of the great public who stand and watch the passing show.

Not altogether. Harry Sutherland, the criminal investigator on the Star's staff, was his personal friend. Harry would willingly give him inside information and discuss the mystery with him.

Rugh caught up the telephone. The girl at the Star's switchboard recognised his voice, and under a minute he was speaking to his friend.

"Rugh Thornton, by the favour of the gods," ejaculated Harry, on listening in. "The one man I wanted. I was going to hunt you up this afternoon, old man."

"Hunt round my office, now," invited the assurance man. "I'm not running away. How long will you be?"

"Five minutes," replied Harry, reaching for his hat. "Dinkum."

Less than five minutes later the Star man entered Rugh's offices and deposited his long length in the most comfortable chair he could find. Then he took off the high-powered spectacles he wore and polished the lenses carefully.

"What's the trouble, Harry?" asked Rugh. The careful polishing of the glasses was an unfailing sign of worry with Harry Sutherland.

"Same inquiry from the Star man," retorted Harry. "As you beat me to the 'phone, suppose you spill first."

"All right," replied Rugh, indifferently. "I want the correct dope on the Little Bay Mystery."

"Read the Star. All the winners, spiced with political scandals, and the dinkum official dope on births, marriages, divorces, and sudden deaths."

"Since when has the Star assumed the role of official apologists for the N.S.W. Police Force?" asked Rugh, sarcastically.

Harry pulled out his watch and studied it. Then he gave his crop of unruly black hair a characteristic rake.

"A little over three and a half hours," he replied with a cheerful grin. "To be exact, since the noon edition, a copy of which I see on your desk."

"Well?"

"Are you interested, old man?"

"Intensely. I am interested to know when Harry Sutherland lost his punch."

"Your people expect you to take an interest in claims against them?" asked Harry, ignoring the assurance man's question.

"Occasionally. You know they run claim inspectors for that work."

"Yet, they are liable to call on you?"

"They might. In the event of their regular men falling down on it."

"They have called on you to investigate claims?"

"What are you driving at, Harry?" asked Rugh, impatiently. "Yes, if you want to know, they have called on my services. Twice."

"Thought so. And they'll call again?"

"Possibly. Get on with your beans, you ass."

"Say, in the event of a mysterious murder?"

Rugh was silent a minute. Then he got out of his chair and strode over to where Harry was seated. "There's something on your mind," he commanded. "Spill it."

"The Little Bay Murder."

"Do you suggest any of my companies are likely to be concerned in the matter?" Rugh asked, speaking deliberately. "Your account of the police investigations presumes the murder to be of an ordinary type and likely to be quickly solved by the authorities."

"Think so?" Harry pulled out a well-seasoned briar pipe and earnestly explored the interior. "Nothing in that account that strikes you as—well, strange?"

Rugh looked at his friend, closely. Harry was intent on his pipe.

"Only that you wrote it," he said at length.

"So." The journalist carefully pieced his pipe together. "There's a Chink, calling itself a Scot, in our office."

"Name McAdoo." The investigator returned to his seat. "What's his latest?"

"Damned if I know." Harry reached out a long arm and commandeered Rugh's tobacco pouch. "He called me on the carpet this morning. Informed me space was valuable, and that an experienced journalist would not require more than a half-column for so trite an affair as the Little Bay murder."

Rugh laughed.

"I guess the 'experienced journalist' had something to say?"

"Said a lot, and all to the point, but—"

"Was informed, somewhat brutally, that three-quarters of the journalists of the Commonwealth were eager to jump into the position of investigator to the Star newspaper. Eh?"

"You might have been behind the door." Harry pulled vigorously, and inquisitively, at his pipe.

"Interesting," commented Rugh.

"Damned interesting." Harry hit the arm of his chair with his open hand, angrily. "I'm coupling that up with a conversation I heard an hour or so previous. No, you old flathead, I wasn't snooping in the office. You know what the 'phone service is there. Wires all of a tangle, and when you cut in you're likely to get anything from the Governor-General to an electric shock. I got McAdoo."

"Well?"

"Heard two sentences before I realised I was snooping. They were: 'The police statements are all I require published.' That was a stranger speaking. Then McAdoo's sweet tones, super-oiled, replied: 'That will be difficult to arrange, Mr. Brene. But if you insist, of course I will do my best.'"

"Sam Brene!" Rugh whistled softly. "You are sure it was the murder they were discussing, Harry?"

"It links up." Harry blew out a cloud of thick evil-smelling smoke. "Story killed, on top of what I overheard. No other police matter in the paper of moment, and—"

"Well?"

"I didn't handle McAdoo any too gently when he called me off," confessed the journalist. "It got me on the raw, and—well, it's the best thing I've had since I took over your job on the Star. I asked McAdoo, straight, what Brene's interest in the matter was."

"Good. You've got a nerve, all right. What did he answer?"

"Stalled badly, of course. The old man can't keep a straight face when he's cornered. Asked what I meant, and looked as confused as a flapper when handed an ice-cream instead of a cocktail."

"Seems reasonable," remarked Rugh, after some minutes' reflection. "Now, where do I come in?"

"Sam Brene's not too far off when there's money floating around," answered the Star man, shortly. "You know his record. Boss of the Town Hall, jury fixer, and king of the grafters' brigade."

"You're guessing a lot, old man."

"I am." Harry abandoned his air of carelessness, and leaned forward earnestly. "I'm guessing it all. I'm guessing that within twenty-four hours you will be on the trail of the Little Bay murderer, with a stake in the game worth playing for."

HARRY SUTHERLAND'S insistence that he would shortly be officially interested in the Little Bay Murder case much perplexed Rugh Thornton. It seemed improbable that the violent death of one of Sydney's "lost sisters" should have any connection with the syndicate of assurance companies employing him. It was possible the woman had been insured for a small amount in one of the companies specialising in low priced policies, but in that event the assurance would be paid without demur. The amount would be too trivial to fight over.

Rugh had a great respect for the abilities of the Star investigator. Harry had a reputation in the journalistic world that was unquestioned. His report of the telephone conversation between Sam Brene and the Star's Chief of Staff was disturbing, though it might not apply to the murder mystery. At any rate, it showed that the Town Hall boss had a string tied on the newspaper.

The next morning Rugh went down to the Criminal Investigation Branch of the New South Wales Police and asked for Inspector Richards. At times he had come in close contact with the police officer and had learned to respect his undoubted abilities.

"You interested in the Little Bay Murder?" exclaimed Richards, when he heard Rugh's errand. "There's nothing in the case that can possibly touch the interests of your companies, Thornton. Why, the woman was one of the type you meet by hundreds in the poorer quarters of the city."

"You have traced her, Richards?"

"Sure thing. Wasn't a difficult matter." The Inspector drew a photograph from his pocket. "Do you know her?"

Rugh shook his head. It was not probable he would have come across such a woman in circumstances that would cause him to remember her. He took the photograph, and studied the pictured face. The woman had once possessed some little claim to beauty, and death, most merciful, had wiped away the coarsening lines of years of evil living.

"Didn't think you would," continued Richards. "Still, newspaper men run up against some queer people in their work. We've got a line on her. Found her husband, and got that photo from him. It's five years old, and she's aged a lot in the time."

"Her husband?" exclaimed Rugh. "Quick work, that, Richards."

"Not so slow, I think." The Inspector appeared to be well satisfied with himself. "He couldn't give us much. Hadn't seen the lady for four or five years. She left him, and went on her own."

"What about the husband?" asked the investigator.

"A decent, hard-working chap," replied the Inspector. "A bit of a pal of one of our chaps at Headquarters. Carpenter by trade, and has a good character from his employers. No, he's let out of it."

"You say she left him. What for?" Rugh was probing for a motive for the murder.

"Not fast enough, s'pose." Richards spoke carelessly. "You'd be surprised how many women in that walk of life give their hubbies the 'good-bye.' Life's too strenuous for them. They read in the papers of Jazz parties and surfing, and late suppers and flickers. It makes 'em discontented; cookin' hubby's tea and breakfast, and washing up after him, has no excitement."

"I had no idea you were a social reformer, Richards," laughed Rugh. "You're almost eloquent."

"Most of our chaps are," retorted the Inspector, soberly. "It's from this woman's class most of the serious crime comes. Take this little lady—Ruth Collins is her name. She gets discontented with her husband, and her life. Takes a drop to cheer her up. Along comes another chap, single, and with a bit of dough. Throws it about, and boasts what a good time he'll give his girl."

"So the lady falls?"

"Sure thing." Richards waved a hand, vaguely, "It's a choice between drudgery and what's called a life of pleasure. Off goes madam on the time-payment system."

"What the—" Rugh stared at the officer, amazedly.

"What else can you call it?" demanded Richards. "She goes with the man on the chance time will clear hubby out of the road. Sometimes time is kind, and the loving couple get married, and quarrel ever after. Let me tell you, my boy, I've come across a good many of these ladies in my time. They're honey itself to their lovers, while hubby's alive. Lord, if they'd given their legitimate mates half the sugar they waste on other men, married life would be a garden of Eden."

"Get back to Ruth Collins," suggested Rugh.

"Oh, in her case hubby was too much in love with life. A hectic year or so, and the lover disappeared. Ruth couldn't go back and hubby couldn't afford a divorce. So there was another lover. It's that, or ill paid factory work."

"Finally?" queried the investigator.

"The streets. Believe what you like, Thornton, I've got a big sympathy with our 'lost sisters.' Life's damned hard on them. Virtue's its own reward, and there's damned few pleasures scattered on the straight and narrow path."

"Inspector Richards preaches an immoral sermon," murmured the investigator. "I take it, the identification of Ruth is the extent of police knowledge, at present?"

"Practically," admitted Richards, honestly, "It's early days to form theories. Why, we can't even get a dear description of the man who knocked down the boy, Archie Clarke. And I saw him with my own eyes."

"How is Clarke?"

"Improving quickly. Got a nasty bump on the head. Lucky for him it was a slanting blow, but that wasn't the fault of our white-coated friend. He hit for murder, damned vicious scoundrel."

Rugh looked down at the photograph of the murdered woman he had held during the conversation. "May I keep this, Richards?" he asked.

"Sure. But what's your game, Thornton. Thought you were employed to guard vested interests. This dead woman isn't likely to cause a run on the coffers of your assurance companies."

"More unlikely things might happen," said the assurance man, lightly. "No one has put in a claim on her behalf, yet, but one never knows."

"If that happens the company may offer a private reward for the apprehension of the murderer," chaffed the Inspector.

"Possibly. Would it be a gift for the police force?" Richards became grave.

"We shall get that man, Thornton," he said. "There's few of 'em who succeed in baffling us."

"Look here, Richards." Rugh made up his mind to test Harry Sutherland's information. "Is there a string on this inquiry?"

The Inspector looked puzzled.

"You can guess what I mean," continued Rugh. "It would not be the first time some influence has stepped in between a criminal and justice. Are you chaps after the murderer for all you, and the department, are worth?"

The Inspector flushed with anger.

"If I didn't guess you had a good reason behind your question, Thornton, I should resent it," he said, sternly.

"I've got a reason, and a good one," replied Rugh, calmly. "I'm not saying the string is on you, but—is it on the Department?"

"If there's a string anywhere it won't affect me, and I handle this case. If I thought the N.S.W. police force was out to shield a murderer, I'd resign."

"I believe you," exclaimed Rugh, impulsively, holding out his hand.

"You had a reason for your question?" asked Richards, quickly.

Briefly, Rugh recounted Harry Sutherland's tale of the overheard telephone conversation between the Star's Chief of Staff and Sam Brene. The police officer listened, thoughtfully.

"I am not going to say there have not been attempts made to tie strings on to the police," he remarked, when Rugh finished. "Politics, to-day, is a game of string pulling. More than once big influence has been used to protect criminals—and not always has that influence utterly failed."

The Inspector paused, and looked steadily at the assurance investigator.

"But, not in murder cases." he continued, passionately. "Murderers stand alone, against the whole police force. Sam Brene may have a pull in the Star office. More than likely he has. But, he has no pull with Edward Richards, Inspector of Police. Take that from me."

Rugh strolled down to his offices, thinking deeply of his interview with Inspector Richards. The theory advanced by Harry Sutherland, that he would be mixed up in the Little Bay Murder seemed so remote as to be absurd.

His clerk met him as he entered his offices.

"Mr. Wilbur Orchard, of the Balmain and South Assurance Company, telephoned an hour ago that he would be glad to see you immediately," said the boy. Then he added, in a half-whisper: "Said it was in reference to the Little Bay Murder."

THE SUMMONS to the Balmain and South Assurance Company astonished the investigator. He had laughed when Harry Sutherland affirmed he would be involved, officially, in the Little Bay Murder, within a short time. Now had come a request to attend the managing director of the largest and wealthiest of the companies retaining his services. That request had been coupled with the direct intimation that the Little Bay Murder would be the subject of the interview.

Leaving his offices, abruptly, Rugh went down to the assurance company in Elizabeth Street. Wilbur Orchard was awaiting him, striding agitatedly up and down his room. When Rugh entered the private office he came to meet him with outstretched hand.

"Glad you were able to come right away," he said, curtly. "I rang up directly I knew the tangle we were in. Sit down, Mr. Thornton."

Rugh looked curiously at the managing director of the Balmain and South. Although that company was a prominent member of the syndicate he served, this was the first time he had come in touch with Wilbur Orchard, its controlling genius. He saw a short, thickset man of about fifty years of age. The face was square, clean-shaven, and dominated by a forceful chin. Prominent eyebrows, thickly sprinkled with grey, shaded keen grey-blue eyes. The forehead was high, and surmounted by closely cropped hair, almost white.

"Curiously, I have been making a few enquiries into the Little Bay Murder this morning," replied Rugh.

Wilbur Orchard turned abruptly to face the assurance investigator.

"What for?"

"A journalist friend is on the case for his newspaper. His statements of certain aspects of the case aroused my curiosity." Rugh spoke formally. He rather resented the autocratic tone of the question.

"That all?" Wilbur Orchard crossed to his desk and sat down. "Sorry if I am somewhat abrupt this morning. Had some news that upset me."

"I presume it is because of that news you sent for me?"

"Yes." Wilbur Orchard fumbled on his desk for a few moments. Then he passed a postcard-size photograph across to Rugh. "Know that woman?"

"Ruth Collins, the woman who was murdered two days ago on the sandhills at Little Bay." Rugh smiled, and produced from his pocket a similar photograph. "I am curious to know where you obtained your copy of the photograph, Mr. Orchard. When I was given my copy I was informed only a few copies had been printed."

"Never mind that. Yes, I will tell you. I sent over to the Inspector-General for it."

"You must have had a very strong reason for so unusual an action," commented Rugh.

"I had. I believe this company is to be the object of a deliberate fraud."

"Is to be," repeated Rugh. "Then any scheme to defraud has not yet been put in operation?"

"Not so far as we are aware of." Wilbur Orchard picked up a panel photograph from his desk and handed it to the assurance investigator. "Do you know that woman?"

It was the portrait of a girl in her early twenties. Rugh thought he had never seen a more beautiful face. The steadfast eyes looked out from a pure, oval face, framed in a wealth of wavy hair drawn low over the forehead. A slender, rounded, neck held the beautiful head proudly on well-shaped shoulders. The dress was short, revealing graceful legs, slender ankles, and well-formed feet.

"No." Rugh surrendered the photograph, reluctantly. "If your story connects these two photographs it will be, indeed, strange."

"It does." Wilbur Orchard leaned forward across his desk, drumming on the wood with the tips of his fingers. "Are these photographs of the same woman?"

Rugh looked up, startled.

"What exactly do you mean, Mr. Orchard?" he asked, deliberately.

"Answer my question. Would you take these photographs to be of the same person?"

"No." The assurance investigator spoke emphatically. "No sane person would suggest such a thing."

"I believe within a very short time such a claim will be made on this office." Wilbur Orchard smiled grimly as he spoke. "In fact, I have received information to that effect."

"You wish me to understand a claim will be made on this office for an assurance on Ruth Collins, the woman murdered at Little Bay?" asked Rugh, incredulously. "You know the history of that woman?"

"The Inspector-General sent over certain details. Her husband is a carpenter. She left him, lived with other men up to the time or her death. Do you know more?"

"No. You have all the information at present available. Such a woman would hardly be assured for a sum worth fighting about?"

"Do you call two hundred thousand pounds a trifle, Mr. Thornton?" Wilbur Orchard uttered the words in a low tone.

"Two hundred thousand pounds!" Rugh stared at the managing director amazedly. "Do you mean to say that woman was assured in your office to that amount?"

"I have not made such a statement." Wilbur Orchard became peculiarly calm. "I said a claim for that amount will probably be made on this company, within a few days. Perhaps I had better tell you the story in proper sequence. I intend to fight that claim, with your assistance, Thornton."

Turning to a wall safe behind his chair, Wilbur Orchard took out a bundle of papers, and opened them on his desk.

"Twelve years ago the Balmain and South Assurance Company was young and struggling." commenced the managing director. "We had only a small capital and assurance was difficult to write. Money was scarce at that time. It became necessary to raise a sum of fifty thousand pounds. Applications to the banks were unsuccessful. A financial house offered an accommodation, but the terms were extortionate. We had almost decided, however, we must accept these terms when an offer of the sum we required came from a private source."

The assurance director turned over the papers on his desk and selected a legal looking document.

"The offer came from a Mr. Colin Carson, of Roxine Chambers, Pitt Street, Sydney. He described himself as a financier. The offer was a good one."

Again Wilbur Orchard paused, and consulted the document he held.

"The terms were extremely good," he continued. "Unusual in some particulars, I will grant, but faced with the alternative of paying nearly seven times the interest per annum and hampering conditions, from the financial house we had been negotiating with, my fellow directors agreed with me that our best course was to close immediately with Mr. Carson's offer, and ignore anything unusual."

"Wait," exclaimed Wilbur Orchard, as Rugh was about to speak. "There was a condition Mr. Carson insisted on having inserted in the deed, although we assured him we did not require the money for more than a few months; six at the outside. He stipulated that if the money was not repaid to him, personally, or to his heirs, personally, on the due date, the interest should automatically increase by one per cent for every year the loan was outstanding, and interest at the same rate be paid on all interest due."

"The interest for the second year would be seven per cent.," suggested Rugh.

"Precisely. For the third year, eight per cent., and so on. Of course, a like interest would be payable on the interest outstanding."

"Your directors made no objection to so unusual a condition?" asked Rugh.

"We never contemplated the possibility of the loan standing longer than twelve months," replied Orchard.

"From your remarks I judge the loan has not yet been repaid," said Rugh. "With a company as financially strong as the Balmain and South I am surprised. The interest to-day must be very large."

"Last years interest on the accumulated sum of the loan was at the rate of seventeen per cent. As you have stated, the loan has never been repaid."

"For what reason, Mr. Orchard?"

"The absence of the lender. He disappeared. At the end of the first twelve months I wrote to the address given in the deed, informing Mr. Carson the company proposed to repay the loan on due date."

"Yes?"

"That letter was returned to me, by the Postal authorities, marked 'addressee unknown.'"

"YOU MEAN to say Mr. Carson left Sydney without advising you where he was going, and did not return?" asked Rugh, perplexedly.

"Exactly." Wilbur Orchard had lost the air of irritableness that had characterised him during the first part of the interview, and now spoke with the direct crispness of the successful business man. "We made every endeavour to find him. Advertised. Employed detectives, but to no purpose. He literally vanished from the face of the earth."

"Leaving behind him the sum of fifty thousand pounds!" said Rugh, astonished.

"Considerably more than that," corrected the insurance director. "There was interest due, amounting to three thousand pounds."

"I take it that your directors were anxious to repay the loan at the end of the first year?"

"Yes," Wilbur Orchard smiled slightly. "You must remember that there would be a further amount of compound interest, at the rate of seven per cent., falling due the following year, if we failed to make the repayment at the time stated. Seven per cent. on a loan not required is good money thrown away."

"The loan agreement does not provide for the absence of the lender?" asked Rugh. He was seeking a motive for the peculiar business methods of Colin Carson.

"The direct stipulation provided for in the loan deed required that repayment must be made to the lender, or in the event of his death to his heirs, personally."

"It would be open to the Company to apply to the Courts to presume the death of Mr. Carson," said the assurance investigator.

"That action must, undoubtedly, be taken at an early date." The managing director shifted, uneasily, in his seat. "Do you realise, Mr. Thornton, that we are compelled to provide interest on the compounded total of the loan at the rate of seventeen per cent. It's enormous. This last year we had to set aside out of our profits a sum of over £23,000 as interest on this loan. At the interest for next year—18 per cent.—we shall be liable for a sum considerably over £30,000. A few years and the yearly interest will rapidly exceed the original capital sum.

"Why have you allowed the total to amount up in this way?" Rugh asked, curiously. "It would have been but common sense to go to the Courts for relief—to presume the death of the lender, and pay the money into some fund—years ago."

Wilbur Orchard hesitated, before replying.

"To the average man such action would appear most natural. But great organisations, such as the Balmain and South, exist on too precarious a commercial plane. You would be surprised, Mr. Thornton, if you were told the large sums of money a company such as this parts with every year rather than go to law. Cases the average commercial man would fight tooth and nail are compounded by us. Our business is too complicated and insecure to allow of law publicity."

"Insecure?" Rugh thought of the millions held in reserve by the assurance companies in Australia, alone.

"Yes. Insecure. We must be continually seeking new business, and from a fickle public. If we made a practice of resisting claims made on us we should quickly forfeit public favour. The statement would be broadcast that we were resisting legitimate claims, and a large quantity of the new business would go to our competitors."

Rugh thought deeply for a few minutes.

"You are asking a difficult thing, Mr. Orchard," he said, at length. "From what you tell me the trail is so old I shall have great difficulty in finding people who may have come in contact with Colin Carson. For instance, the solicitors who drew up the loan deed?"

"Mr. Carson asked that our solicitors should do that."

"Still, they must have interviewed him, as to details?"

"Weston, Sons and Hamilton, are our solicitors." Again Wilbur Orchard answered hesitatingly. "I believe Mr. Hamilton attended to the matter personally. He looked after our business. I regret to say he died some years ago."

"I presume you conducted the preliminary negotiations for the loan," said Rugh.

"I did. Mr. Carson called on me at this office twice. Other details were arranged by letter."

"Then you should be able to give a fairly accurate description of the man."

Wilbur Orchard laughed, shortly.

"There you have me at a disadvantage, Mr. Thornton," he exclaimed. "When Mr. Carson came to see me he was muffled up to the eyes. Said he was suffering from a severe attack of influenza, and he certainly looked like it. When I mentioned the matter to Mr. Weston he informed me he had caught but a glimpse of Mr. Carson when he called at his offices and he was then muffled in the same manner."

"But you can surely give me some description of the man?" exclaimed Rugh, in surprise.

The assurance director turned to the papers on his desk.

"The detectives we employed asked of me the same thing," he remarked, picking out a paper. "Here is the description of Colin Carson I drew up then. You will remember it was drawn up some years ago, so it is more likely to be accurate than my memory to-day."

Slipping on his glasses, Wilbur Orchard commenced to read slowly.

"Height, nearly six feet, very thin. Bald in front. Hair, scanty and black. High forehead. Eyebrows, thin and straight. Eyes, very dark brown, enlarged pupils. Nose, Roman. Remainder of face covered by thick woollen muffler. Voice, very husky and low, due to severe influenza attack. Hands, encased in thick woollen gloves, dark grey. Wore a heavy dark brown overcoat, with big collar; turned up. Kept it buttoned while in my office. Trousers, dark grey, indefinite pattern. Boots, lace-up, black. Carried an umbrella with an ivory skull as handle."

"Umbrella with ivory skull handle," repeated Rugh. "There's not many of them about."

"You must remember I am speaking of at least ten years ago," reminded Wilbur Orchard. "That umbrella is, no doubt, destroyed by this time. By the way, there is one thing I remember now I did not tell the detectives. The man had a mole high up on the left cheek-bone."

Rugh finished his notes and placed them in his pocket.

"Now, Mr. Orchard," he said, "we will go back to the two photographs. You asked me if I could trace any resemblance between them. What reason had you for such a question?"

"I thought you would come back to that," remarked the assurance director, with a smile. "Before I answer I should inform you of a conversation I had with Mr. Carson prior to the completion of the loan."

The managing director fidgeted with his papers for a while, and then continued:

"When Mr. Carson informed me of the terms he proposed I was somewhat taken aback. In particular, I questioned the clauses relating to the repayment of the loan. The fact of retaining the money for twelve months at the low rate of interest proposed was acceptable, although we had anticipated making the repayment in three or four months. I may say here, the terms proposed by the financial house we approached were, for three months' loan, at the rate of ten per cent."

"For the three months?"

"Yes. I questioned, particularly, the personal repayment clause. Mr. Carson would not give way. In conversation he stated he had a daughter, a schoolgirl, and that he had no other relatives. In the event of his death within the twelve months the money would be repayable to the trustees of his child."

"Did Mr. Carson say where the child was? If she was at school, or where?" asked Rugh.

"He promised me full particulars at a later date. Unfortunately the matter slipped my memory."

The assurance director hesitated, and then added:

"You will understand, Mr. Thornton, an institution, such as the Balmain and South was at that time, can use any amount of capital. Six, seven, and even ten per cent. are reasonable interests in building up a large business. Once we realised we were out of touch with Mr. Carson we allowed the matter to drift. It was inexcusable of us, I admit, but we thought Mr. Carson might turn up at any time, and we could come to some arrangement in regard to the accumulated and increased interest. It was only when the interest began to mount up abnormally, we began to get anxious."

"Then you have no knowledge of the daughter?"

"None, whatever."

"Yet you connect her, in some way, with the woman who was murdered on the sandhills at Little Bay. So far as I can see, Mr. Orchard, there are no grounds for such connection."

"You can see no likeness between the two women?" Wilbur Orchard asked the question, anxiously.

"There is no likeness. You have forgotten the big difference in ages."

"They are not the same women?"

"No."

"Yet I have been advised, by telephone, that a call will shortly be made on this Company for the repayment of the Carson Loan."

"That in no way connects the two women." Rugh spoke impatiently. The man before him appeared wishful to conceal information he had.

"I asked, over the 'phone, if I was speaking to Colin Carson, and received a reply in the negative. I then asked if my informant was speaking on behalf of Colin Carson's heiress."

"Yes?"

A brutal laugh came to my ears over the wire. Then the voice said: "Oh, she's on the sandhills at Little Bay!"

"You asked who was speaking?"

"Twice. The first time the question was ignored; the second time the answer was: 'You'll know soon enough.'"

"Did you recognise the voice? Have you any remembrance of it? Was it a man, or a woman, speaking?" Rugh asked the questions rapidly.

"A man spoke. I seem to have a recollection of the voice, but at present I cannot place it."

"When did this conversation take place?"

"This morning," replied the managing director, his face blanching. "I had been reading about the murder coming in on the train. Immediately I telephoned for you."

WHO WAS the man who had telephoned Wilbur Orchard informing him a demand would shortly be made on the Balmain and South Assurance Company for the repayment of the Carson loan? Wilbur Orchard had stated he believed an attempt was to be made to defraud the Company and explained the telephone message as a piece of bravado on the part of one of the gang.

Rugh could not accept this theory. The reference to the heiress of Colin Carson being "on the sandhills at Little Bay" puzzled him. Was it an attempt to induce the belief that the murdered woman was Colin Carson's heiress?

Harry Sutherland's assertion that he would shortly be interested, officially, in the Little Bay Murder appeared to bear out this theory. On the other hand, Rugh could not trace any resemblance between the photographs or the murdered woman and Colin Carson's daughter, and some general likeness was necessary to support the mysterious telephone message that Colin Carson's heiress would be found "on the sandhills at Little Bay."

Returning to his offices Rugh telephoned the Star offices, to be informed that Harry Sutherland was out at the moment. Leaving a message at the switchboard for the journalist to communicate with him immediately on his return, Rugh closed the door of his private office, and sat down to con over the problem.

Before him were three lines of inquiry. Slender threads but one of them might result in a clue he could follow. There was the man who had telephoned Wilbur Orchard. It was the newest clue, but a very weak one. Probably the call had originated from a public telephone booth. In that case much depended on the situation of the booth. If the man had used a booth at one of the crowded centres of the city he would have disappeared in the crowd immediately he left the instrument.

On the other hand, a man engaged on so delicate a mission might seek a booth in a situation where the chances of being overheard were slight. In that case, there was a possibility of him being remembered by someone in the vicinity. Pulling the telephone towards him, Rugh rang up "Information."

"A telephone call was put through to Mr. Wilbur Orchard of the Balmain and South Assurance Company about ten o'clock this morning," he said, when he obtained connection with the officer in charge. "Will you give me the number and address of the caller?"

"The Balmain and South have a large number of calls every day," objected 'Information.' "It may be impossible to single out the one you want."

"Quite so," Rugh laughed, softly. "Mr. Orchard will he obliged if you will give the messenger he is sending to you a list of the calls made to the Balmain and South between nine and ten-thirty this morning. All right. I will send over at once."

Opening his door, Rugh instructed Teddy Marlow, his clerk, to go to "Information" and ask for the list of calls being prepared for Mr. Orchard, of the Balmain and South Assurance Company.

Leaving his door open, so that he could watch the outer office during the absence of Marlow, Rugh returned to his desk.

The principal problem Wilbur Orchard had set him to solve was the disappearance of Colin Carson. A man of wealth has usually many anchors to civilisation. Colin Carson had been able to lend the Balmain and South a very large sum of money. Rugh had inquired on what bank the cheque had been drawn, and the managing director had stated the money had been handed over in the form of bearer securities. The financier had informed Orchard he had a daughter, a school-girl. Her name should appear in the records of some school, more probably a boarding school. Schoolgirls are prone to make lifelong friendships. Possibly he might chance on some schoolgirl-friend who still maintained a correspondence with Rita Carson.

Finally, there was the building in which Colin Carson had had his offices. "Roxine Chambers, Pitt Street," had been the address on the loan deed. This was a very slender clue. Years before, the detectives employed by the directors of the Assurance Company had no doubt searched the place. Even it they had missed a few points it would be almost impossible to pick them up after so long an interval.

The assurance investigator was roused from the reverie into which he had fallen, by the noisy entrance of the Star man.

"So." Harry Sutherland stood in the doorway, and looked down, quizzically, on his friend. "So, my words have come true. The noble protector of indigent assurance companies is on the track of the Little Bay murderer."

Rugh looked up with a start.

"What do you mean?" he exclaimed. "Look here, Harry, your remarks indicate you know more than you have told me. How do you come to know I am on the murder?"

Harry crossed the room and seated himself on the edge of the desk.

"If you desire, dear comrade, to peer into the depths of a detective's brain, catch him in maiden meditation, and let your fancy free. Seems my shot told. 'Nother thing. The famous Sherlock Holmes sent for his faithful Dr. Watson."

Rugh laughed. There was nothing else to do with Harry.

"All right," he said. "I am on the murder. At least, partially. Listen, and I will tell you how it came about."

Very briefly, Rugh went over the interview with Wilbur Orchard.

"Somewhere the two matters link up," he concluded. "You said I would be officially interested in the murder. I am. Now what reasons had you for that statement?"

"Not one iota of reason. Nothing but the bare fact that our mutual friend, Sam Brene, appears to be interested in the murder also. When that gentleman appears interested I look around with wide open eyes. His particular object in life is money, lots of it and, apparently, the dirtier, the better. Assurance companies have lots of money. Q.E.D."

"A damned long shot," commented Rugh.

"Not at all," returned the journalist, blithely. "Most people are insured, now-a-days. All Sam would consider, if he came across a dead body, would be, how much the dear departed was insured for, and, more particularly, how he could get his talons, not talents, dear comrade—on it."

"Reasonable reasoning for a Star journalist," laughed Rugh. "How's the hunt going?"

"Legions of police; hordes of the public; a few journalists, and many more 'would-be's;' fewer camera-men, and regiments of film-wasters, make Little Bay the latest, newest, and most excitingly popular seaside resort."

"Granted." Thigh leaned back in his chair and looked critically at his friend. "I should have reminded you my inquiry was not due to idle curiosity. What progress have the police made? We will deal with the social side later."

"Progress!" Harry threw up his hands in mock horror. "They've trampled the place flat. First, they drew a cordon of large footed members of the force in a circle of about a hundred yards diameter around the spot marked—'X' in brackets—and then proceeded to systematically demolish everything within that magic circle. Bushes, rushes, trees, all brought to the ground. They even trod down the sand."

"With the result?"

"Nil. Absolutely nil." Harry made an eloquent gesture. "I've had the time of my little life, lying on my little bingie on a sandhill, outside the circle, watching and learning how not to catch a murderer. Borrowed, without explanation or regrets, the sporting man's glasses. He tipped three winners straight off, through the shock of losing them."

"That all? I thought you would know the police theory?"

"My boy!" Harry became mock serious. "You asked for facts. I did not know you required them mixed with fiction. I am officially advised the police have found a cast-iron theory."

"Which is?"

"From information received—to wit, a tram conductor, and a few passengers—the police are convinced Ruth Collins left the city on a Little Bay tram about four o'clock on the afternoon preceding the day her body was found. She is said to have been accompanied by a man of seafaring aspect."

"Well. What's wrong with that?" asked Rugh impatiently. "It sounds reasonable."

"Most reasonable." Harry laughed, derisively. "You will deduce from that, the woman never returned to the city."

Rugh sat up quickly, intent on his companion.

"Enough of fooling, Harry. What, exactly, do you know?"

"The woman was murdered in or near the city and her dead body conveyed to Little Bay in a motor car."

"That's serious," exclaimed Rugh. "You must have excellent reasons for that statement."

"Think, man." Harry spoke energetically. "If you'd thought over the facts you would agree with me. Listen. Three indisputable facts make my proof. First, there were no signs of struggles on the spot. The police admit that is correct. Do you think the woman lay down and meekly allowed her assailant to do her to death? Secondly, the clothes were neatly folded and piled on the body. What murderer would go to that trouble, while in the open beside the body of his victim? That alone, is proof the deed was committed in some place, such as a room, where the murderer was reasonably safe for a time. Lastly, the amount of blood around the body was remarkably small. Too small for the hideous wounds she received."

"She was kicked to death," objected Rugh.

"Another police yarn," said Harry, in disgust. "She was murdered with a blunt cutting instrument, and her clothing shows neither cuts nor bloodstains."

"YOU say the woman was murdered with a blunt, cutting knife?" said Rugh, slowly. "Are you certain of your facts, Harry? If you are correct you are bringing a grave charge against the police force."

"I know what I am saying," replied Harry, testily, "I'm not stating she was not kicked, brutally, nor that her death was not the result of being kicked. I am saying that a knife, or some similar instrument was used on the body, prior to it being conveyed to Little Bay."

Rugh sat silent for some minutes, conning over the fact Harry Sutherland had placed before him. If the Star man had not made a mistake, the police were withholding valuable information. Were they doing so for a definite purpose?

"I had a talk with Richards this morning," said Rugh at length. "He told me the only information the police had related to identification. Where did you get your information, Harry?"

"Constable Nicholls." Harry searched his pockets for his pipe. "An interesting member of the police force, my son. An officer of diligence, and activity. With a fixed conviction the detective department is composed of incompetents."

"In which theory he is ably and consistently supported by a well-known member of the Australian Journalists' Association," added Rugh.

Harry grinned.

"Got any 'bacca, Rugh. You used to keep your pouch on the desk. I hate suspiciously mean people. Where was I? Oh, Nicholls. Owing to this well-known incompetence, an intelligent member of the road-levelling brigade has taken the lonesome trail."

"Nicholls, on his own."

"Exactly. Theories are worrying things, and induce a desire for a sympathetic friend."

"Harry Sutherland, the sympathetic friend! By the little gods, Harry, you and Nicholls make a great team."

"Don't we?" Harry ran a hand through his mop of unruly black hair. "Damn this pipe. Won't draw. Pass over that spike, old man. Never mind the papers, they won't get in my way. Oh, take them off if you want to. I don't mind. Yes, sir. The new firm of Nicholls and Sutherland is on the trail. The senior partner forms the theories, and states facts. The junior partner listens. Both satisfied. Say, Rugh—"

Harry put down his pipe, and sat up, intent on a new idea that had occurred to him.

"How about a jape on the most clever, intelligent, and dignified police department of N.S.W.? You've not met Nicholls. He's great. The real, dinkum, musical-comedy policeman, with more than a hint of old time melodrama."

"Something's going to break now," Rugh looked at his friend in mock alarm.

"Quit your kidding. This is serious. You can't acquire any kudos over the affair, even if you solve it—with my help, of course. 'Chink' McAdoo bars my way to fame, as the solver of the great 'Little Bay Mystery.' What about boosting Constable Robert Nicholls, as the great sleuth?"

Harry leaned back in his chair and shouted with laughter.

"Oh, it's great. All the big-wigs at Headquarters outguessed by a constable they despise and snub. Nicholls says the mighty Richards gave him an awful dressing down the morning the body was found. He's still sore over it."

"You're going too fast, young man." Rugh's eyes sparkled at the idea of the joke. In his journalistic days he had suffered, in common with other pressmen, by the cock-sure attitude of certain members of the police department. "First we've got to find the murderer, and build up the proof against him, before we can hand over a ready-made reputation to your new friend."

"The firm now is Nicholls, Thornton and Sutherland," chuckled Harry, irrepressibly. "Lord, what a mouthful. We'll succeed, all right, old man. By the way, there's a chap coming to see us here. He was coming to the Star office, but when I got your message I left word for him to follow me here."

"About the murder?"

"Sure thing. Name's Smith, Joseph Smith. Calls himself a bushman. Says he has information about the Little Bay murder."

"Why doesn't he take it to the police?"

"Says he did and they turned him down cold. That's believable."

A knock came at the door, and Teddy Marlow entered.

"The paper you required, Mr. Thornton." Teddy was always mysterious over business.

"Hullo, Teddy," greeted Harry. "How's Sexton Blake, and all his merry crew?"

Teddy grinned. A well-set youth of fifteen, he thought he had attained the ideal situation when he became clerk to the investigator. His chief study was detective literature of all kinds, and his ambition wavered between a private detective agency and journalism.

"I'm studying the Star lately," he answered, turning at the door to grin broadly at the journalist.

"I bought that," Harry shouted with laughter. "Never mind, I'll chalk it up to McAdoo's account. What have you there, Rugh?"

The assurance investigator spread a sheet of foolscap paper on the desk.

"I asked 'Information' for a list of calls made to the Balmain and South this morning, early. Here it is."

"Some list," commented the journalist. "I suppose we can leave out of account all calls from reputable firms and people?"

This reduced the list considerably. At the end of five minutes Rugh had pencilled on a pad five numbers that appeared to require investigation.

"One of these should represent Wilbur Orchard's unknown caller," he said. "We'll ask the Balmain and South if they can identify any of them."

"Balmain and South?" he asked when be obtained the connection. "No, young lady. I want a word with you. Rugh Thornton speaking. I'm going to give you five numbers—telephone numbers. I want to know if you have had calls through them from people you know. Yes? Well, ask Mr. Orchard. He will tell you to give me the information I ask for."

Rugh turned to the journalist with a broad smile on his lips.

"The young lady is discreet. Says she cannot give me information without authority, and—"

"Yes," he spoke into the instrument. "All right? Well, listen, Y00407."

The investigator paused and wrote a few words on his pad. Then he gave the other telephone numbers in succession, pausing after each number for the switch operator's comments.

"That reduces our investigations to three," he commented, as he hung up the receiver. "The lady says W0449 and Y507 are telephones used frequently by B and S agents."

"The city numbers will give us some trouble," remarked Harry thoughtfully. "Probably both these city numbers are at the G.P.O. or at city post offices."

"That leaves F3111 to be considered." Rugh lit a cigarette. "That number belongs to the Waverley district and would suit a man bent on the errand we are tracing."

"A man to see you, Mr. Thornton. Says his name's Smith, Joseph Smith," announced Teddy, putting his head in at the door.

"Bring him in, Teddy." Harry Sutherland shifted his chair back from the desk "We're going to hear something now Rugh."

The door opened and Teddy ushered in a tall thin man, well bronzed by northern suns. For a moment he stood in the doorway, looking from Rugh to Harry. At length he advanced to Harry.

"Guess you're Mr. Sutherland," he said, holding out his hand. "Got your message at your office to come 'ere."

"Good guess," laughed Harry. "How did you do it?"

"You don't fit th' place. Leastways, not as 'e does. 'Sides, th' boy looked at 'im as if 'e was boss, when 'e opened th' door."

"Sit down, Smith," said Harry. "Let me introduce you to Mr. Thornton, whose offices we have taken possession of. Mr. Thornton is interested in what you have to tell me. That is, if it's in connection with the Little Bay murder."

"Pleased to meet you." Smith shook hands, solemnly with Rugh. "It's about th' murder I came t' speak t' you."

"Why did you come to me?" asked Harry, curiously.

"I asked a chap at t' Coffee Palace, an' 'e ses I'd better go to the th' Star. So I 'phoned an' th' young lady as answered sed I'd better see Mr. Sutherland."

"What do you know about the murder, Mr. Smith?" asked Rugh.

"I knows a lot," drawled Smith, in his peculiar clipped bush speech. "I guess I can put you on to th' bloke as did it."

"You know the murderer?" asked Harry, eagerly.

"I don't know 'is name," replied the bushman. "But I guess I can give you a line on 'im as'll 'elp you t' find 'im. 'E's a tall man as weighs a good bit, an' e's lame ov th' left foot."

"A lame man!" Harry looked incredulous.

"W-e-l-1 not ter say exactly lame. But 'e's got a bad limp, all th' same. It may be natural, or it may be 'cos ov a blister, or summat on 'is 'eel."

"YOU'RE making an astounding statement, Smith," said Rugh gravely. "What are your grounds?"

Joseph Smith stretched his long legs in front of him and thrust his thumbs into the armholes of his waistcoat.

"Th' trouble wi' you towns-folk is that you can't see what's under your eyes," he said in his peculiar drawl. "I was stayin' at th' Coffee Palace when this 'ere murder 'appened an' I thought as 'ow I'd take a look round an' see if there was anythin' about as you town-fellers 'adn't noticed."

"City folks are unobservant," remarked Harry, gravely.

"You've sed it Mr. Sutherland," answered the bushman earnestly. "There's a lot on th' ground, an' in th' air, an' sky they don't see. Cos why? They ain't edicated t' it. Well, as I ses, I 'ad a look round so far as th' cops 'ud let me. That wasn't fur, for they'd got a lot ov men marchin' round in a big circle, a-warnin' peoples orf. I wanders round th' circle, an' looks about me, an' comes across a pad as led from where th' woman was lyin', down to t' beach. I'd given up 'opes ov a look round when th' cops stopped me from goin' t' where she was found, so I wanders down that pad, casual-like.

"Suddenly I saw sumthin' that made me look agen. It was a bootmark, an' looked as if it 'ud been made about th' time th' woman 'ad been murdered. I trailed it up an' found th' t' other one—that's th' left foot, an' saw as 'e was lame."

"You're certain of that, Mr. Smith?" interposed Rugh.

"You can't deceive me as t' pads," replied Joseph Smith proudly. "I've seen too many ov 'em. 'E wos goin' down to th' water, but I followed 'im up backwards, 'cos I wanted ter see where 'e'd cum from. Th' pads led right up to where th' body 'ad laid. When I got to th' police circle a cop stops me. I showed 'im th' mark, an' e calls a pal, an' they calls th sergeant. 'E looks at th' pad as if 'e'd never seen one affore, an' e asks me wot I wanted ter do."

"I told 'im I wanted ter foller 'em up, an' 'e asks: 'Wot for?' I ses, I suspicioned as th' bloke as made 'em might 'ave 'ad sumthin' ter do wi' th' murder. 'There's been a lot ov our chaps a-walkin' round 'ere,' e remarks, an' I agrees. It wos plain ter see they 'ad. 'Can you follow 'em up?' asks Mr. Sergeant, an' I answers as 'ow I might try. 'Very-well, then,' e ses, 'Come along.'

"So I went along an' th' Sergeant went wi' me, watchin' me sharp. I showed 'im th' pads 'ere an' there, an' e ses, 'Jest so,' an' 'Certainly.' Then we comes to th' place where th' body wos found, an' there, 'arf under a big footmark as wos like th' Sergeants's, I found another pad ov th' limpin' man."

"Th' Sergeant wouldn't let me go down th' 'ollow, but I walks alon' th' edge. Presently I stops an' bends down. 'Wot d'yer see?' asks th' Sergeant. 'Th' limpin' man came over 'ere,' I ses. 'Sure?' 'e ses. 'Certain,' ses I, 'an' e came from over there.' I followed th' pads up, th' Sergeant tailin' on behind me, an' th' pads went down another 'ollow. At th' bottom I turns up th' sand a bit. 'Wot d'yer make ov that?' I asks th' Sergeant, 'andin 'im a bit ov caked sand. 'Wot is it?' 'e asks. 'Blood,' ses I. 'Th' poor creature was dumped 'ere first, an' then dragged over there. There's th' marks plain ter be seen.' But 'e couldn't see 'em. Those town cops aren't edicated enough. Th' tracks led out ov th' 'ollow an' up to th' road, an' just afore 'em was th' tracks ov where a motor car 'ad pulled orf th' road, an' stood sum time."

Rugh looked at Harry. The journalist had his lips pursed in a silent whistle.

"What did you do then?" asked Rugh of the bushman.

"Followed th' pads back agen," answered Smith promptly. "I wos curious ter see where they led to. So, wos th' Sergeant, fer 'e came with me. They went right down th' track to th' beach an' down t' where th' tide 'ad washed 'em out. I cast round a bit, an' then th' Sergeant left me. But I wouldn't give up. Th' bloke never went down there fer nothin'."

"I got a good way alon' th' beach afore I chances on wot I wos lookin' fer. It wos this."

The bushman pulled from his pocket a roll of newspaper and placed it on the desk. Harry reached over and unrolled it. In the paper lay a woman's stocking, dirty and sodden by sea-water.

"A stocking!" Harry gave a shout.

"The lost stocking. I wondered where it had got to," he cried. Then noticing Rugh's astonishment. "Didn't you know, Rugh. The clothing found with the woman was incomplete. Among the things missing was a stocking?"

"I didn't know that neither," put in the bushman. "But I did know as that limpin' man 'adn't gone down to th' beach fer nothin'."

"A limping man, a stocking, and the body dragged from one place to another," commented Rugh. "The mystery deepens."

"What's this?" exclaimed Harry, who had been handling the stocking. "There's something in it."

Gingerly he turned the stocking inside out. There rolled on to the desk a well-worn gold ring, tarnished by sea-water. It was a man's signet ring, and on the shield were engraved letters. Harry picked up a magnifying glass lying on the desk and examined the engraving.

"As well as I can make out it's a couple of 'C's,'" he remarked.

Two 'C's' exclaimed Rugh. He leaned over and took the ring from the journalist. A glance satisfied him that Harry was correct.

"Colin Carson!" Harry uttered the thought in Rugh's mind.

"Nonsense," exclaimed Rugh. "'C's' are common initials. The woman's name was Collins. Probably her husband had a christian name commencing with 'C.'"

"His name is 'William,'" stated Harry. "I've seen the man. 'William' is his one and only name."

"Still this ring might not have belonged to Colin Carson," argued Rugh.

"And yet it might." Harry took the ring and dropped it in the stocking again. Then he rolled the stocking in the newspaper and handed the package to Smith.

"My advice to you Mr. Smith is, to go down to the Police Headquarters in Hunter Street, and see Inspector Richards. Give him this and explain where you found it. Make your statements as fully as you have made it to Mr. Thornton and myself."

"Sure," replied the bushman, pocketing the package. "Hope I 'avn't done wrong in comin' ter you fellers?"

"Not at all," replied the journalist suavely. "We are much obliged for your interesting narrative. At the same time I would suggest you did not mention at the Police Department your call on Mr. Thornton and myself. These 'cops' as you expressively name them, are rather jealous of newspaper men, and might resent you informing us of your find."

"I'll make a note ov that," said Joseph Smith, shaking hands formally and vigorously.

"Colin Carson, again," said Rugh, softly, as the door closed on the bushman.

"Sorry I blundered, old man," remarked Harry. "Shouldn't have mentioned the name before our bushman friend. But it was a blow under the belt."

"How did the woman come to have Colin Carson's ring?" asked Rugh perplexedly. "Of course, there is nothing to prove it is Carson's ring, but it looks bad."

"Coupled with the tale of the telephone message to Wilbur Orchard, it certainly does look bad," agreed Harry. "I was half inclined to keep the bally thing, but—"

"Wouldn't have been wise," replied Rugh. "Smith might have talked. Looks as if Wilbur Orchard was right in saying he believed a fraud on the Balmain and South was brewing."

"You've got your work cut out," commented Harry sliding down into his chair, in a characteristic attitude. "A fight to a finish between Rugh Thornton, the famous assurance investigator, and a gang of crooks."

"The purse being two hundred thousand pounds," added Rugh with a laugh. "I don't feel at all—"

The telephone bell broke in on his sentence. Rugh picked up the receiver and gave his name. Then he listened intently for a couple of minutes.

"Richards wants to see me at once," he said, as he replaced the receiver. "He says there's a new development in the Little Bay murder."

Harry looked at his watch.

"Smith hasn't had time to reach Headquarters," he observed. "Appears to me things are moving rapidly this morning."

"I'M coming with you," exclaimed Harry, reaching for his hat. "You don't mind, Rugh?"

"Not a bit," answered the assurance investigator. "Richards is an old friend of yours. He won't mind, considering the attitude your newspaper is taking on the murder."

Harry made a wry face as he followed Rugh to the lift.

"Afraid that attitude will come a bad cropper presently," he observed, when they were on the street. "I've put in a formal complaint against 'Chink' McAdoo's interference to old Osmond."

"Any results?" queried the investigator.

"Nope. But the old man won't stand for the Star running a bad second to the 'Post.' Humphries, who is doing the murder for them, is making things very willing."

"The Limping Man will make a good yarn," laughed Rugh. "Don't mention the ring, old man. I want any connection with Colin Carson kept out of the newspapers."

Harry looked doubtful.

"Richards is particularly thick with Humphries," he said. "Ten to one he gives him the tale complete. Might as well go the whole hog, old man. After all, the Carson loan affair is, so far, between you and the company."

Rugh thought a minute. They had turned into Hunter Street and were only a few yards from Police Headquarters.

"All right," he said; and led the way up the steps into the vestibule. Richards was waiting for them in the corridor, and led the way to one of the interview rooms.

"Glad you came with Thornton," said the Inspector, as he shook hands with Harry Sutherland. "I put a call through to your office, but you were out."

"The Little Bay Mystery forges ahead," observed the Star man with a grin. "How do you like investigation work without the valuable aid of the Star, Richards?"

"It's strange," laughed the Inspector. "Truth is, the Chief simply gasps when he opens your rag. Can't get used to the new conditions."

"Why not telephone McAdoo and protest?" suggested Harry, with a twinkle in his eye.

"And get a leader on police irresponsibility," countered Richards. "He might publish that letter the Chief sent the Star some months ago, protesting against unfair criticisms of our methods."

Harry caught Rugh's eyes, and winked. From the Inspector's observations the police were running true to form.

"What's the new development you spoke of on the 'phone?" asked Rugh.

The Inspector settled himself comfortably in his chair and took from his waistcoat pocket a small article wrapped in tissue paper. While he spoke he held it in his hand.

"The Little Bay Murder is one of the biggest problems the police have tackled of recent years," he commenced, gravely "There is a total lack of motive, and clues are few."

"The identification of the woman leads to no results?" queried Harry.

"Identification was easy," answered Richards. "We guessed she would be known to some of our men who do duty in the Surry Hills district. Several men identified her, and it was not long before we traced her history back to the time she left her husband."

"You have not her record before her marriage?"