"The Green Pearl." Cover art by Terry Walker©2017

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

"The Green Pearl." Cover art by Terry Walker©2017

THIS book is a product of a collaborative effort undertaken by Project Gutenberg Australia, Roy Glashan's Library and the bibliophile Terry Walker to collect, edit and publish the works of Aidan de Brune, a colourful and prolific Australian writer whose opus is well worth saving from oblivion.

Mark Therrold, British Secret Service Agent, took a small case from his pocket and placed the one gem it contained on the table before the astonished hotel manager to whom he had been speaking.

The manager's verdict was: "A pearl, M'sieu... the Queen of Pearls. Ah! you beautiful, beautiful thing."

"Beautiful, yes," said Therrold. "It should be beautiful, bathed in the blood of countless men and women. Can you imagine the thousands who have marched to misery and death—because in the depths of the ocean an oyster conceived the only known green pearl?"

What was the secret of the pearl?

Why had so many died trying to win it?

The secret is revealed in "The Green Pearl," the thrilling serial by Aidan de Brune, commencing in this week's "World's News."

Headpiece from "The World's News."

"MR. ROHMER, I am certain that a woman entered my room last night."

Carl Rohmer sat back in his chair and smiled.

During the twenty years he had managed the Hotel Splendide he had listened to stories and theories sufficient to fill a library. Few of the confidences received by him ever became public. It was his uncanny ability to stifle gossip and scandal that had won for him his position in Sydney's largest and most luxurious hotel.

"And, the lady, M'sieu. What did she do?" Rohmer carelessly picked up an ivory, paper-knife from the desk, tapping with the blade, softly and irregularly, on the polished wood.

"You think I had a pipe-dream?" the man on the opposite side of the desk laughed lightly. "Let me tell you, Mr. Rohmer—"

"Tut, tut!" Rohmer's white hand waved away the suggestion. "I asked the question, Mr. Therrold, in the way of business. It is well to commence at the beginning of the story. M'sieu had supper and retired to his apartments, yes?"

Mark Therrold nodded; A tall; clean-shaven man of about 35 years of age, he seemed strangely perturbed, huddling down in the big lounge chair and running his fingers, continually, through his fast-greying hair.

"My supper, if you call it so, consisted of a few sandwiches and a whisky-soda at the bar," he retorted. "Then I went up to my room. It was a hot night and after a shower I sat smoking and reading for an hour. Then I turned in."

"And the time?" The hotel manager nodded encouragingly.

"When I went to bed? About 12.30, I should say. I did not look at my watch."

"M'sieu slept well, eh?"

"No. It was too hot to sleep. S'pose I dozed a bit. Anyway, it was some time after I turned in that I had an idea that there was someone in my room."

"The person—a woman, M'sieu suggested—made some noise?"

"Hardly a sound. I woke suddenly with the idea that there was someone in the room; but I could hear nothing." Therrold shifted restlessly. "I simply felt there was someone near. Oh, I can't explain. I had the feeling that there was a woman near."

"A woman?"

"I saw her, later. I lay still, with my eyes half-opened, watching. Shifting restlessly, I managed to roll over so that I could watch the half-lights through the windows. After some considerable time, I saw a shadow lift before the light. I thought she was making for the bathroom, but she came to the side of the bed and bent over me."

"M'sieu says that the lady bent over him as he lay in bed. What then did she do?"

"Nothing. She stood for a minute as if listening to my breathing. Probably wanted to see if I was; asleep. I lay quiet, hoping to find out what she was after, but she seemed to move quite aimlessly around the room. Once I caught a fair view of her. She appeared to be about 25 years of age, and fair. I noticed that her hair was closely cropped, just like a boy's."

"Yes?" The drumming of the paper-knife on the table became insistent. "You say the lady was young—and possibly of good looks and—M'sieu did not say what she wore—possibly evening dress?"

"I shouldn't call it that, Mr. Rohmer." Therrold laughed. It was a pleasant laugh, and softened the lines of his face. "To my ignorance it appeared to be more like night attire—just a long coloured wrapper, caught up at the side by a button or a hook."

"M'sieu has good eyesight. If I mistake not, he said that the only light came from the window—and the night, it was dark."

Therrold flushed. "The girl bent over me; I saw her quite close. S'pose she wanted to make sure that I was asleep. When I moved, to try and get a clearer view of her, she disappeared."

"M'sieu missed nothing from his room?"

"Not a thing. When I was certain that she had left the room I got up and searched. She had taken nothing."

"M'sieu intrigues!" Rohmer hesitated. "Has M'sieu with him anything of value?"

For a few seconds Therrold did not reply. He stared intently at the little hotel-manager, then let his eyes wander around the beautifully appointed office. Rohmer's room was more like a sitting-room than the nerve centre of a busy hotel. The large desk in the centre of the room, was of rare black oak, in keeping with the other furniture. Around the walls were black-oak bookcases, filled to overflowing. On the bookcases and tables stood rare specimens of china and statuary. The floor was of highly polished parquet blocks, over which were scattered valuable rugs and skins. A few pictures hung on the walls, but each of them was signed by some noted Australian painter.

The hotel-manager watched his guest carefully. Except for the incessant tap-tap of the paper-knife, he was immobile. Once he glanced across at a tall Japanese screen in a corner—and then a little smile played on his lips.

At length Therrold appeared to have made up his mind to some action. Leaning forward, he pulled from his waistcoat pocket a small enamelled box. From it he took a roll of black velvet and, placing it on the blotting pad before Rohmer, flicked it open.

"A pearl!" The manager learned forward, with a quick whistling intake of his breath. "M'sieu, the Queen of Pearls!"

It seemed as if a ball of lambent fire lay on the small velvet square. The pearl was medium in size and almost pure oval in shape, containing within its far depths a wonderful green fire, A lover of rare and beautiful jewels, Rohmer bent worshipfully over it. His fingers twitched as if anxious to lift the beautiful thing and fondle it.

"The Romanoff Green Pearl." Therrold spoke softly. With a pencil he gently rolled the jewel over. The movement seemed to set the iridescent green moving in long, surging waves of colour.

"So!" Rohmer could not take his eyes from the jewel. "It is wonderful. Unique! There is not another like it in all the world. M'sieu, I have heard of—this, but I never hoped to see it. Behold—it is priceless—no money can buy it! But so, it is worthless, for who will pay for it—anything? It stands alone—the one green pearl known to men. Ah, you beautiful—beautiful thing!"

"Beautiful, yes." Therrold spoke bitterly. "It should be beautiful; bathed in the blood of countless, men and women. Mr. Rohmer, can you realise the misery and sin this overlaid grain of sand has caused through its existence? Can you picture the thousands who have marched to misery and death—because in the depths of the ocean an oyster conceived the only known green pearl? You cannot—nor can I. Yet, if its history were known and published, the whole world would demand its destruction. Wherever it has rested it has caused misery, covetousness and—"

"And you, m'sieu?" Rohmer lifted inquiring eyes at his guest.

"I?" Therrold shrugged. "Yes, Mr. Rohmer, you can number me among its victims. Five years ago I accepted a commission from the Grand Duke Paul, the heir to the Romanoff Crown, to venture into Russia and recover the Green Pearl. For nearly five years I have lived a life I shudder to remember. I have lived with men—no, beasts, devoid of all human instincts. Men drunk with the lusts of blood and rapine. For over a thousand days I have lived, not knowing if I was to see the morrow's light. I staked my employer's money—my own life—on the quest. Oh, I've succeeded—but at what cost?"

"Behold, you have accomplished!" Rohmer waved his hands over the jewel.

"I entered Russia from—Europe—intending, when successful to retrace my steps. With almost incredible luck I got in touch with the men who had the jewel. When opportunity offered, I stole the pearl from them—the men who had stolen it from among the Russian Crown jewels. Unluckily, their suspicions against me were aroused. Failing to regain the jewel they denounced me to the rulers of Russia claiming that I had been the original thief—that I had stolen it from among the regalia. I was thrown into prison; my belongings and person were searched again and again—but I had hidden well. I was questioned—tortured. I escaped—and was recaptured; to be again questioned—again tortured. Again I escaped and for months lay hidden within a few miles of my former prison. Then a chance came for me to leave Russia, across the old German frontier.

"The opportunity appeared too easy—or perhaps I was over-suspicious. Yet I accepted the venture. On the frontier I was again arrested and searched; but the pearl was not on me. For a time I thought that they would put me across the frontier. In that case I would have lost, for the pearl was hidden in Russia. One night I was taken from prison and carried into the heart of the empire. Months of questioning and torture followed—and again I escaped. Now I had to retrace my steps to where I had hidden the pearl. It was still there.

"Then a friend warned me not to venture towards the European frontier. I turned east, lacking food, money, and, even clothing; almost dead from the privations and injuries I has sustained at the hands of men who preached a universal brotherhood. Day after day I plodded on, towards the rising sun. Man, if I told you one tithe of what I saw and suffered you would call me a liar.

"One day when I had almost given up hope of getting anywhere, I crossed the borders of the Chinese Empire. There wasn't much chance—for me; I had evaded the emissaries of the Russian Government, but now I faced the Chinese bandits. News of what I carried seemed to have flown before me. Again and again I was searched—but always managed to conceal the pearl. Even when I got into districts where European influence held sway I found, that. I had enemies, secret and unscrupulous. Then, suddenly, I had to face an added danger—and a strange passport."

"In what, m'sieu?" Rohmer questioned, interestedly.

"I found that the Green Pearl was some sort of sacred jewel of some long-forgotten Central Asian Empire. This meant, that while I had not lost my enemies—and indeed they seemed to multiply the closer I got to the coast—I had friends. It was through those friends I at last managed to get on board a boat—bound for Australia; That is all, ex—"

"Except that you have arrived here."

Rohmer gazed curiously at the man who had, into a few short years, crowded the adventures of a lifetime. "Now, m'sieu; as to the woman—the woman of the night. M'sieu suspects—"

Therrold shrugged. "The Soviet commands strange agent, and have a nation's wealth to forward their aims. Then," he hesitated. "There are others."

"The pearl, m'sieu." Rohmer spoke firmly. "You should have deposited it in the safe of the hotel. It is my duty to warn m'sieu, that the proprietors cannot except any risk occasioned. If it were stolen—"

"A not uncommon incident in the life of the Green Pearl," Therrold laughed. "No, Mr.—Rohmer. The pearl has its—home and would be hard to find; even if I did not stand in the way; Point of fact; it has been stolen from me three times since I left Russia. Then I stole it from the men who stole it from the Russian Government. They stole it from the Romanoffs, who probably stole it from some race they conquered. Possibly that race had to record a theft—Who can tell how far back its history goes—of theft and murder, for a jewel weighing only 18 grains. It's safe with me—"

"What's that?" Therrold was on his feet, automatic in hand. The air of weariness had fallen from his shoulders; Again he was the alert Secret Service Agent holding his life of less value than the safety of his charge.

Backing slowly, he came to the corner of the desk so that he commanded not only the screen, from behind which had come the noise that had startled him, but also the alarmed hotel-manager.

"You—behind that screen! Come out, quick! I've got you covered!"

"M'sieu!" Rohmer held out an explanatory hand. "M'sieu, let me—

"Be silent!" Therrold spoke impatiently. He turned to the screen again. "Come on out. I shall count three and then fire." He waited a moment. "One—two—"

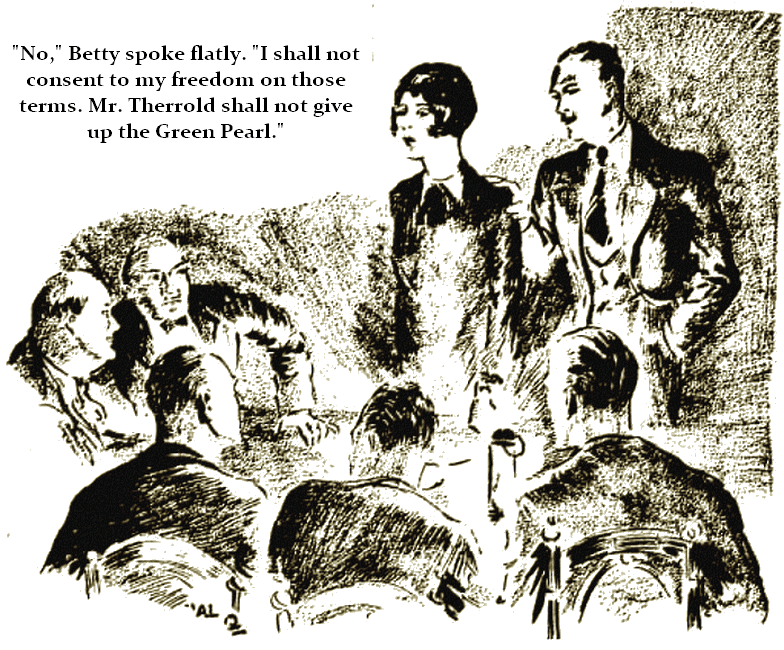

The screen was swept to one side and a tall, slender, pale-faced girl walked into the room. She held an open note-book in her hand. Falteringly, she came towards the desk, her terror-stricken eyes fixed on the automatic, levelled at her. Therrold's hand dropped to his side. He stared at the girl in amazement.

CARL ROHMER ran round the desk and placed himself between the girl and Therrold, waving his arms wildly and pouring out words in half the languages of Europe.

The Secret Service Agent stood back, watchful. He made no attempt to gather the meaning of the manager's excited torrent of words. He knew that in time the man would exhaust his excitement, and a proper explanation would then be forthcoming.

"M'sieu! M'sieu!" At length Rohmer dropped into English

"I, Carl Rohmer, am to blame, it is not the young lady—No, she is but an employee of the hotel—the establishment. It is the rule; and m'sieu must pardon that I make it obeyed, that she place herself behind the screen. I—I—myself—I am desolate—despairing. It is my fault, m'sieu. I blame myself that I did send for the girl that she might make for me a record of a story most marvellous."

So that was the meaning of the tapping with the paper-knife. Therrold laughed in relief.

"You gave me quite a scare, Mr. Rohmer. I'm not yet used to civilisation again. S'pose I must offer my apologies to the young lady, for the shock I must have given here. Also to you, Mr.—"

The quick pause made Rohmer turn suddenly.

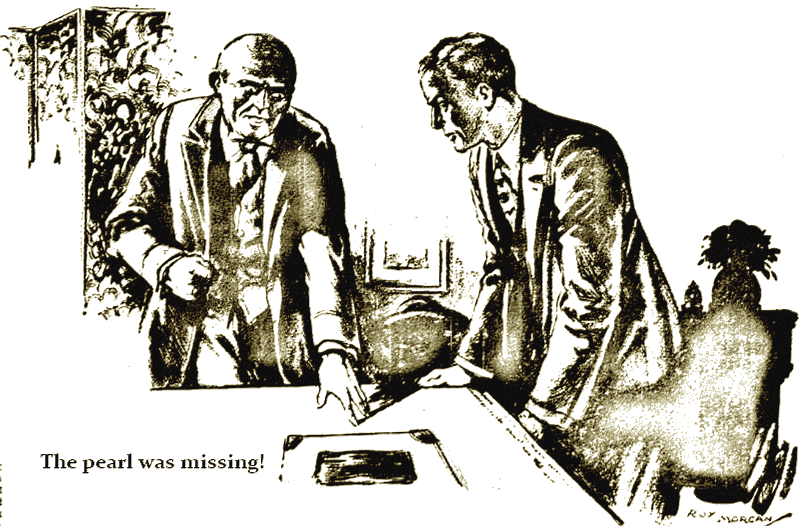

Therrold was staring at the desk. The manager's eyes went to the blotting

pad. On it still rested the square of black velvet—but the Green Pearl

had disappeared.

"The pearl!" Rohmer gasped; "it had—!"

He made a step towards his chair to feel the Secret Service Agent's automatic touching his chest.

"Quite so!" Therrold's smile was chilly. "I am beginning to understand. Quite an interesting plot, yet I don't quite fathom the reason for the lady of the night. Did she search for the pearl on her own account, Rohmer, or was she but a decoy to make me betray where she had hidden it? No, you needn't answer, unless you really want to talk—that is at present."

For a few moments the Secret Service Agent stood motionless; his automatic covering the manager and the girl.

Then he laughed, harshly. "Of course, the lady of the night was a decoy. She drove me to you, I was fool enough to let you know that I carried the pearl and—yes, you had your plans ready—that girl behind the screen to draw my attention at the psychological moment. I fell into the trap. Very pretty. Looks to me that I'll have to accuse you of stealing the pearl, Rohmer. You were behind me for a few seconds, while I was engaged in persuading your confederate to come out into the open. Yes, yes! You alone had the opportunity to steal it! But, how do you mean to get away with it? The pearl's in this room, I'll swear to that! Bluff me? I don't think so!"

Again Therrold paused, his keen eyes searching the room and its appurtenances. He lowered his gun and bowed mockingly.

"Rohmer, unless you hand me that pearl at once I shall accuse you of its theft. Oh, I know it's not on you." The agent laughed at the motion of denial from the manager. "I don't have to search you to know that. I don't think it's in the desk, or on it; for you expect the desk to be searched. The girl hasn't got it; I'm certain of that, unless you two can act quicker than I believe. Is it in the room? You must have guessed that I'd search everywhere—to drop it into one of those delicate pieces of china would be absurd. Well, well, I'll be absurd, just to please you."

With lithe, swift steps the Secret Service Agent moved around the desk and seated himself in the manager's chair, his automatic ready for instant use. For a moment he stared at the pair before him, the hotel manager a picture of distressed dismay, the girl pale, but more composed.

"We may save a lot of unpleasantness—" Therrold hesitated. "Pardon me, I am forgetful. Mr. Rohmer, may I trouble you to place a chair for the lady—before the desk. Miss—er—I haven't the pleasure of knowing your name—will you please be seated. Thanks, Rohmer, you'll find that chair comfortable. Yes, like that! Your hands well in sight, please. Thanks. Now—but it is understood, Mr. Rohmer, that neither you nor the lady attempt to communicate without my consent. Now I'll place my gun on the desk—so. Please remember, I have the reputation of being an excellent snap-shot—and I shan't be careless again, to-day."

He drew the telephone towards him, keeping a keen watch en his prisoners. Calmly, he requested the switch operator to connect him with police headquarters. A few moments and he gained the connection and requested that a couple of detectives be sent to the hotel.

Replacing the receiver he looked up at Rohmer.

"Perhaps I might have asked the direct question, before calling in the police." Therrold's voice was almost careless. "I believe you realise that I command the situation. I can assure you that I possess credentials that will ensure me all the help that I require." He paused, then added suddenly: "Rohmer, have you the Green Pearl?"

The hotel manager shook his head, slowly. His eyes were on the automatic on the desk, but a few inches from Therrold's hand. He was strangely pale, his eyes glittering dangerously.

"Quite so!" The Secret Service Agent laughed. "And you have no knowledge of where it is. No? Really you are very stubborn. Mr. Rohmer. Now, Miss—er—well, names don't matter. Have you the pearl?"

The girl shook her head. Therrold frowned. He picked up the paper-knife and tapped with it meditatively on the desk.

"Strange!" The adventurer spoke after some moments meditation. "I was just beginning to feel safe in this big caravanserai of yours—and hearing English spoken around me again. S'pose I relaxed a bit. That gave you the opportunity. Careless, very. Should have remembered that those devils of modern Russia manage to get quite decent people in their employ. No, there's no need to talk, Rohmer, unless you want to tell me where the pearl is. Just keep your hands in your lap and—"

He paused, the paper-knife still drumming on the desk. Suddenly, its tapping changed from the rhythmic drumming to an irregular, staccato beat.

Therrold's eyes lifted, staring directly at his prisoners.

"Got that, Rohmer? No?" The man laughed slightly. "Well, it was a simple request, in rather poor Morse, for the return of the pearl. Really, that tapping was a brilliant idea. Didn't use the Morse, or any code. Just the steady beating—and it caught me. I'd have read the Morse, if you had used that."

A knock came at the door. Therrold left the desk and opened the door, peering out. Then he stood back, admitting a couple of men. An hotel attendant, who attempted to follow them, was thrust back and the door locked, and bolted.

"Mr. Rohmer, the manager of this hotel, and the young lady, name unknown, who he states to be his typist." Therrold introduced his prisoners, in response to the bewildered looks of the detectives. "I'm staging something like a hold-up, y'know. May I ask who is in charge?"

"Detective Sergeant Saunders, from headquarters." The elder man spoke brusquely. "Who are you and what are you doing with that gun?"

"Seregeant Saunders."

Therrold repeated the man's name; then he stepped forward. "I think this has a meaning for you, Sergeant."

He held up his closed hand. As the detective's eyes came down to his closed fingers they opened. On his palm lay a queerly cut and marked disc of gold.

"I understand, sir." The officer glanced sharply at Therrold. "This is plain-clothes constable Browne. May I ask your name?"

"Mark Therrold—" For a moment the Secret Service man's eyes met the constable's. "It happens that I am a guest at this hotel. A bare half hour ago I was seated in this room alone, as I supposed, with Mr. Rohmer. I was lodging a complaint that someone had entered my room during the night. He asked me if I carried anything of value. I showed him a very valuable pearl that I was carrying out to England. I had taken it from my pocket and placed it on a scrap of velvet, on the blotting pad before Mr. Rohmer. I heard a sound behind that screen. At my challenge this young lady walked into the room. After explanations with her and Mr. Rohmer I turned to the desk—to find that the pearl had disappeared."

Sergeant Saunders looked puzzled. A largely-built man, of ordinary intelligence, he had gained his present rank in the service by hard plodding work. Crime was to him but the happenings of the day and to be solved on rigid, orthodox police lines. Happenings of uncommon nature perplexed and confused him.

"Mr. Rohmer is a responsible person, sir," he suggested, after an interval.

"I agree." Therrold smiled. "I'm holding him entirely responsible. Only we three were in the room—and he, alone, was in a position to take the pearl, unobserved."

"And the lady, sir?"

"A matter of precaution. Understand, Sergeant, no one enters or leaves this room until I get that pearl back—or am satisfied that it is not in the room, or on the person of anyone here."

"Are you giving Mr. Rohmer and the lady in charge, sir?" Saunders stared at the Secret Service Agent in dire perplexity. He had not the faintest notion of how he should act.

Had it been the case or an ordinary theft—yes; but, here he had been shown an emblem of power that awed him.

"Don't be an ass, man!" Therrold spoke sharply. "I don't want anyone arrested. I want that pearl. Rohmer will not make any fuss at anything you think fit to do. He has his hotel to think of. Now, get busy and find that pearl."

As Therrold turned impatiently from Sergeant Saunders, his eyes caught those of Constable Browne. The man stepped forward saluting sharply.

"S'pose you've forgotten me, Captain Therrold. Constable Browne—Tom Browne! Knew you at once, sir."

For a fraction of a second the Englishman looked at the constable. Then his face brightened and he held out his hand. "Thought I knew your face. Sergeant Tom Browne. Say, Browne, can you get some action in this country of yours. I want this room searched for the pearl. If it's not in this room, then it's on someone here—one of the three of us. Shouldn't be difficult."

Browne saluted again and with a muttered word to his superior officer, took charge of the proceedings. Here Sergeant Saunders was on safe ground and showed great ability. Therrold watched with keen admiration, yet with sinking hopes. The pearl was not in the room. At length the young man went to where the Secret Service Agent stood.

"It's not in this room, sir. I'll swear to that." The man spoke in a low voice. "Unless—?"

"If you can't find the pearl in this room you'll have to search them," stated the adventurer, firmly.

Rohmer started an energetic protest, which was supported by the red tape sergeant.

"'Fraid you'll have to give them in charge first, sir," interpreted Browne, with a broad grin. "We're not on the Somme here, sir."

"Charge, nothing." Therrold spoke irritably. "My authority carries me, I believe?" Browne shook his head, dubiously. For the moment the Englishman was perplexed. During the past five years he had lived where his warrant tor his actions was his ability to shoot first, and straightest. The laws and regulations of civilisation irked and baffled him.

The girl broke the tension. From the moment she had walked from behind the screen she had not spoken, obeying Therrold's orders, passively. "Send for a women and she can search me," she said in a low voice. "I have not stolen your pearl, Mr Therrold, and I am not afraid."

Detective Browne immediately called headquarters, asking for a woman searcher to come to the hotel. Then he went to the Japanese screen and righted it, then turned to Therrold.

"There's two in this room you can't suspect, Captain," he said, briskly. "Sergeant Saunders and I came in long after the pearl was lost. I suggest that you give Mr. Rohmer a lead by allowing the sergeant to search you. Then he can't think you're trying to put one ever on him."

Therrold looked at the hotel manager, who nodded assent. He went to the screen, beckoned the sergeant to accompany him. Five minutes later he emerged into the room, pulling on his coat.

Without a word, Rohmer left his seat and joined the officer behind the screen. Almost immediately a knock came at the door. Browne opened it and a middle-aged woman entered. A few words from the police officer and she walked to where the girl sat. Almost immediately Rohmer and the sergeant came from behind the screen. The police woman touched the girl on the arm and walked to the screen. For some minutes the four men waited. At last the woman came out, shaking her head, negatively.

"No results, sir." Brown swung round to face Therrold. "The pearl's not in this room, and it ain't on either of you three people. It fairly beats me."

Therrold looked uncomfortable. For a second he hesitated, then went to where the girl sat. "I owe you an apology for the indignity of the search," he said, haltingly. "I know you must think badly of me, but—'

"You forget." The girl smiled slightly. "I was behind that screen during your interview with Mr. Rohmer. I can't understand how the pearl has disappeared. It is very valuable, you said."

"It is not the value, exactly." Therrold hesitated. "The pearl is valueless, except to three groups of people in the world. It is so unique—the only Green Pearl—that it would be absolutely valueless to anyone but one of the three claimants for it. It is unsaleable, yet—"

"Some jewels carry a fate beyond their worth," completed the girl.

Therrold did not reply. He looked at her with interest a moment, and with renewed apologies, he turned to the detectives.

"I'm afraid—'

"An exclamation from the hotel manager caused him to turn sharply. Rohmer was standing before the desk with the square of velvet in his hand. On the blotting pad, where the velvet had rested, was drawn a large red chalked 'IV."

THERROLD gazed at the red chalk mark on the desk in amazement. A few minutes and he walked to the windows and stood staring out over the Domain, his hands thrust deep in his pockets. Detective Browne went to him.

"Queer business, Captain." The officer spoke in a low voice. "Make anything of it?"

Therrold smiled, but did not answer the question. He pointed out of the window towards the Harbour. "One of the finest views in the world, Browne. This country of yours is magnificent. A great pity you cannot attract a big population."

"Not all immigrants are acceptable, sir." Browne stared out of the window, following the line of Therrold's pointing finger. "No! Yet Australia takes any immigrant, so long as he can pass a simple language test, is in fair health and is not a known criminal. I suppose the riff-raff of the European continent come here—Greeks, Italians, Russians, Maltese, Swiss—' The Englishman made quite an appreciable pause between each nationality. At the word 'Swiss' the detective made a slight sign.

"The Swiss make good immigrants, sir," he protested, somewhat loudly. "Mr. Rohmer has quite a number of them in his employ."

"Is that so? I thought there were only three in the hotel."

"That's so; but there is a fourth coming soon." Browne turned. "Mr. Rohmer. I've been telling Mr. Therrold about your Swiss waiters. Is it three or four that you have?"

"The Swiss are the finest hotel men in the world." Rohmer left the Sergeant and came across to Therrold and Browne. "All my waiters are Swiss. I will have no others."

"Then we were both mistaken, Browne." Therrold laughed. He turned to the senior police officer. "What do you propose to do next, sergeant?"

The man scratched his chin, meditatively. "All I can do it to report the matter to headquarters, sir," he announced after an appreciable pause. "Mr. Rohmer's story agrees with yours. The pearl was certainly lying on the desk when you heard the young lady behind the screen, and turned. He says that he is certain that it was lying on the velvet when he jumped up from his chair to come round the desk. As there is no door on that side of the room, I can't understand how it could have been taken."

"Seems we're all at fault, sergeant." Therrold laughed bitterly. Without detective Browne, he would have been at the mercy of this slow-witted official. "I've lost the pearl that I sacrificed five years of my life to gain. I've failed in my mission, and that at the time when I began to think of success."

Browne looked curiously at Therrold. The Secret Service man was taking the loss of the pearl far too easily. Even if he had not known the Englishman Browne would have been suspicious; but he had worked with the captain, he knew his tenacity of purpose. He guessed that the present attitude of careless ease—of quiet acceptance of defeat—must cover some rapidly evolved scheme.

"By the way, Mr. Rohmer," Therrold continued, speaking directly to the hotel manager for the first time since the police officers had entered the room. "I must apologise for the unceremonious manner in which I held you up. I have apologised to Miss—"

"Miss Easton," supplied the hotel man, hastily. "It is not necessary for m'sieu to apologise. In the excitement of the happening it was a mistake forgivable. In the room happened only M. Therrold, myself and the young lady. Would m'sieu steal his own pearl? No, no!" The little manager held out a white hand. For a moment Therrold hesitated, then barely touched it and turned to Browne.

"Come and see me, sergeant. Any time you're free, and we'll have a yarn over war days. My telephone number is—let me see—Ah, yes, 519. That's it."

"Pardon!" Rohmer interrupted quickly. "M'sieu is mistaken. The number of the telephone is the number of the hotel. It is B0 3175. M'sieu has the room with the number 519."

The Englishman laughed slightly. "I must again apologise to everyone for the trouble I have occasioned."

He walked to the door and opened it. Miss Easton followed him. As he stood aside to let the girl pass out he caught Browne's eyes. A glance, full of significance, passed between the men.

In the big lounge, filled with the usual gay, inconsequent throng, Therrold paused and watched the girl pass through the swing doors leading to the general offices. A slight frown puckered his brow, a frown that deepened as the girl glanced back, and hesitated. For the moment he thought that she was going to return, but with a little shrug she passed out of sight.

Passing to the lifts, Therrold went up to his rooms and dropped wearily into a chair. He had lost the Green Pearl—the Queen of Pearls—he smiled at the title the hotel-manager had bestowed on the jewel. It fitted somehow; fitted a jewel that had glowed in the crown of more than one monarch in Europe and Asia.

Thrice, as he had told Rohmer, the pearl had been stolen from him. And—each time it had come back to him—sometimes in circumstances that might be named decrees of fate. Now he had lost it again—for the fourth time. Well, he would have to recover it.

In the big city under the Southern Cross he had relaxed his precautions. He had thought himself safe, forgetful of the fact that the Soviet agents are scattered all over the world, unmindful of the fact that from the moment he passed the frontier into China every Soviet agent in the world had been apprised of his possession of the jewel—that world-wide orders had proceeded from Moscow that the pearl was to be regained at any cost. The years that he had spent in Russia had convinced him that the Green Pearl in Russian eyes was something very sacred—a belief even held by men who protested a violent disbelief in God.

His experiences in Asia had convinced him that in some remote corner of that vast continent lived a race that looked upon the jewel with the utmost veneration—that the Romanoff possession of the pearl had made for their great ascendency over the country. He knew that if he escaped from the east with the pearl in his possession—if he succeeded in fulfilling his mission and placing the jewels in the hands of the Grand Duke Paul—that the Russian Government would go to any lengths—even to inciting a fresh world war, to regain it.

They dared not let it rest in the hands of the Romanoffs. The pearl would become the centre of innumerable plots and revolutions. Even in European Russia there were men who looked upon the jewel as a definite sign of empire—men who could follow any aspirant to the Russian throne who carried on his standard the sign of the Green Pearl.

He knew that he would regain possession of the pearl and carry it to England—to the man who had set him a task others had proclaimed impossible. He was confident of his ultimate success. He had worn the Green Pearl over too many weary miles to doubt—carried it through too many trials and dangers to lose confidence now that he again walked under the British flag.

Therrold was aroused from the reverie into which he had fallen by a knock at the door and the entry of detective Browne. A sign from the Secret Service man prevented him closing the door.

"Thought you'd come up," remarked the Englishman. "Sit down. I'll get some drinks." Browne dropped into the indicated chair and watched Therrold go to the telephone.

"Queer how the pearl disappeared." Therrold spoke inconsequently. "Can't understand it. What did that chalk 'IV' mean? If it means that this is the fourth time the infernal jewel's been stolen from me, the writer isn't far out."

"Keep an eye on the mirror," he whispered, as he passed the detective when returning to his seat. "There's quite a bunch of spies in this house."

Browne glanced up sharply. The door was set at an angle that prevented him seeing through, though in the mirror he had a fair view of the corridor. Therrold's seat commanded a smaller, but direct view, at a different angle. No one could be in the corridor, before the room door, without one of the men being aware of their presence.

"S'pose you haven't formed a theory about that chalk mark, Browne?" Therrold was mixing the drinks. "Say when?"

"Thanks, sir. Not a ghost of an idea. Quite a mystery."

"Many Soviet agents in this city?"

"'Reds' you mean, sir? Quite a few but noisy—not dangerous." The Englishman sipped his drink, meditatively. Suddenly he swung to face the detective.

"How many Internationals have there been, Browne?"

The police officer was silent for a minute.

"The Third Conference of the Third International was held at—" He hesitated. "In Europe about a couple of years ago!"

"There'll be no more Conferences." The Secret Service man laid a strong emphasis on the last word.

"You mean that a new International will be held?" Browne asked quietly. "That will be the Fourth International?"

"The Fourth International." The eyes of the two men met. In their minds rose the 'IV' chalked on Rohmer's desk.

"I asked you as to the strength of the Soviet agents in Australia." Therrold spoke after a pause. "You state they are negligible."

"Others might hold a different opinion, sir." Browne looked perplexed. "It is not for me—"

Therrold's hand shot forward and opened. Under the police officer's eye glittered the queerly shaped badge. The man sprang to attention. "Before wife, children, land, parents." The Englishman spoke as if reciting a ritual. "Before love of women, honour of men, our country, king and Empire."

"Sir?"

"To-morrow I shall ask the Commissioner of Police to transfer you to special duty—and gazette you for long leave of absence. You will report to me, here. I think you understand that the Green Pearl has to be recovered—at any cost."

Therrold's manner suddenly changed. Again he became the careless English officer travelling for pleasure—an attitude he had assumed on reaching Australian soil. He stood up and held out his hand, cordially, to his subordinate. Some sixth sense drew the eyes of the two men to the mirror. The door had swung slightly more open. Framed in the glass was a young girl and behind her a slim grey-faced man, on his head a queer-shaped skull cap from beneath which straggled long locks of grey hair. His features were decidedly Asian.

FOR some seconds the two men stared at the figures in the doorway. Then Browne jumped to his feet and dashed towards them. He tripped over a rug and fell heavily. Therrold, more deliberate in his actions, sprang over the detective's prostrate body and reached the door, pulling it violently open.

The corridor was empty. Fifty feet along the corridor was a corner, where the passage led to the elevators. Glancing to the left, and seeing no one in that direction, the Secret Service man dashed to the corner and raced down to the lift gates. The indicators showed that both lifts were near the bottom floors, one of them descending and the other rising. The man and woman could not have escaped that way.

Going back to his room, Therrold examined the doors on either side of the corridor. He wanted to knock at each door and enquire who occupied the room, but he had no excuse for the action. At his own door he met Browne, who had searched the corridor in the opposite direction.

"No luck, sir," the man reported. "Gosh! I went a thud that time."

"Perhaps it is just as well we didn't catch them," Therrold laughed. "All they did was to peer into a room where we were enjoying a drink. That's not illegal. Did you recognise either of them?"

"Can't say as I did, sir." Browne set the door at the old angle, before returning to his chair. "The man didn't look quite natural—rather funny, in fact."

"A Chinese?" queried the Secret Service man. "I thought so, too. That help, Browne?"

The police officer thought deeply for a few minutes. He drew a small memorandum book from his pocket and turned the leaves. "There was a Chink here, two years ago, sir, who gave the Department a bit of trouble. Name, Dr. Night—or that's what he chose to call himself."

The detective paused and looked up at the Englishman. "From what we discovered it appeared that he was the big noise in the Sydney dope-world. Get away after wrecking the house he occupied and killing a bunch of our fellows who were raiding the place. The description broadcasted stated that Dr. Night looked like a Chink, yet had points that might lead one to think him to be of partly European ancestry."

"The man at the door was certainly Chinese—or from one of the Central Asian countries," observed Therrold, thoughtfully. "If he is not pure Chink, then he comes from one of those mysterious tribes in Central Asia that seem to have provided the population for Europe and Asia. I heard quite a lot of queer yarns about those tribes while making my way from Russia to Singapore. One of them ran that in almost prehistoric days a Central Asian monarch over land that is now China, and most of the other parts of Asia, establishing what he claimed to be world-wide empire. From what my informant said, that empire lasted some hundreds of years."

"What became of it?" Browne asked the question idly. He appeared to be interested in his manuscript book.

"Drowned in its own success." Therrold stretched out his hand for the soda siphon. "Degenerated until they could not hold their sway over the many tribes they had conquered. The legend tells that they were driven back into the hill fastnesses of their country and disappeared from those days of practical politics. Most of the legends of Central Asia are founded on similar themes—and always with the same ending; that they or their descendants, are to come back in the fullness of their old glory, reconquer their old territory and establish a far larger and more lasting empire. In that is embodied the instincts of all races—the hope of a Messiah, to lead the lost nation back to their past glory."

Browne was gazing into space, a puzzled frown on his face. He held the little book open in his hand, apparently forgotten. At length, he sat upright and closed the book. A quick glance towards the door and he leaned forward.

"That was Dr. Night, sir—the man who peered in at the door," Browns spoke in a whisper. "He comes from somewhere out of the heart of Asia and claims to be a sort of prophet king. There was a reporter on the Mirror. He could tell you quite a tale about him. From what was rumoured at the time, this Dr. Night kept him a prisoner in his house for days—and he was in the underground room when Dr. Night blew it and Inspector Frost and his men up. Hardy's his name, Robert Hardy, and he tells some queer story of being transported into some hidden city in Asia and seeing Dr. Night on his ancestral throne, wearing a wonderful Green Pearl in—Lord!"

"The Green Pearl!" Therrold was all attention. "The legend of the Green Pearl is that it once adorned the crown of some great Asian monarch. Why, Browne, even the rumour that I was carrying it gave me a queer sort of kudos in many districts I passed through."

"Then Dr. Night came after the jewel, sir. You can bet on that." Browne stared at the Englishman with wide eyes. "And that girl; she is in it, too. Acting for Dr. Night, no doubt. That's why she was in your room last night."

Therrold lit a cigarette, thoughtfully. For a time he lay back, blowing rings towards the ceiling. Suddenly he sat up. "You've given me quite a lot to think about, Browne," he said. "Yes, I think our friend at the open door and Dr. Night are the same person. What's his game? The Green Pearl, you claim. I don't think you're far out. Now, does he know that I lost it in Rohmer's office? If not, how long will it take him to find that out. Once he gets that information, what will he do. Go after Rohmer? If he does, should I keep tabs on him or stick to the trail of the Green Pearl. I'd rather he thought I still had it; then he'd only watch my dust. Anyway, the pearl's gone for the present."

"Doesn't seem to trouble you, sir," Browne chuckled.

"The thing that's troubling me at the moment is that 'IV' on Rohmer's desk. The pearl will come back. That's certain. I've lost and recovered it before."

"Who's got it now, sir?"

"Quién sabe!" Therrold laughed. "So far as I know there are three groups of people after it—and intend to possess it, by hook or by crook. The Soviet Government claims it because they rule Russia. The Romanoffs claim it because they ruled Russia and wore it in their crown. This Dr. Night appears likely to put in a claim for it because his ancestors once owned it. Who'll get it eventually I'm not going to try to guess. One thing only I know—that is that I shall recover possession of it and deliver it to the man who sent me in search of it. If he's wise, he'll put it under a hammer until it's dust—but he won't do that."

"Who was the girl with the doctor, Captain?"

"The girl who came into my rooms last night and searched my belongings." The Englishman rose to his feet. "Well, Browne, I'll see the Commissioner and get your release. Then we'll take the trail of the Green Pearl. By the way, you might tip your chief that Dr. Night is loose in this city. If he can jug him for a time that would help us considerably. We'd only have our Soviet friends to consider then. See you to-morrow, constable."

For some time after Browne had left the room Therrold sat thinking deeply. Then he threw off his coat and waistcoat and stretched out on the lounge, closing his eyes. For nearly an hour he lay; then sat up and looked at his watch. It was just on two o'clock.

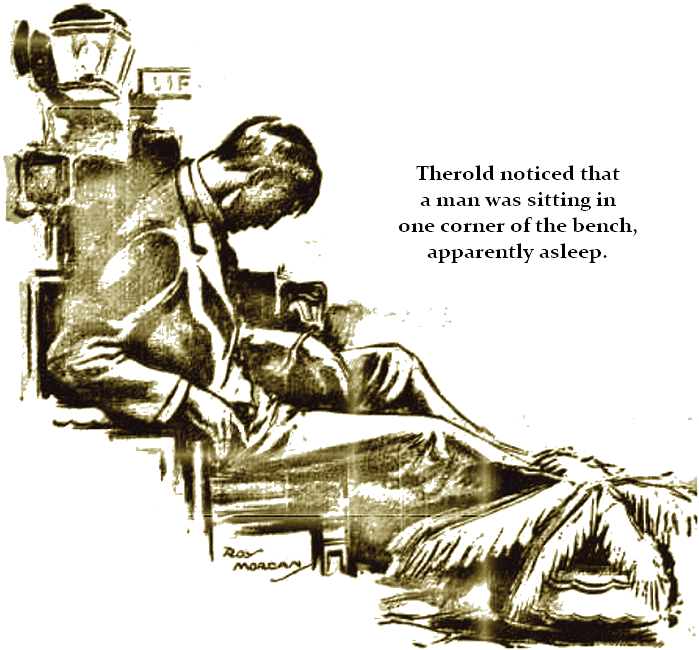

Dressing leisurely, he sauntered down the corridor to the elevators. Opposite the lift-gates a long bench stood against the wall. As he came towards the gates, Therrold noticed a man on the bench, apparently asleep. He looked at him curiously, but his face was bowed, concealing his features. Therrold rang the lift bell then turned again to face the man.

There was something strangely familiar about him. He went to the bench and stooped to peer into the man's face; then straightened, with a low whistle. When the elevator reached the floor, he was standing square before the gates.

"Get down to the offices and bring up Mr. Rohmer as quickly as you can," he ordered tersely. "Tell your mate not to bring anyone up to this floor. That applies to you, too."

The man looked doubtful, but Therrold was imperative. When the lift had dropped out of sight, the Englishman returned to the seated figure. Taking care not to touch him, he bent and made a careful examination. The man's hands attracted attention. The Englishman tore his handkerchief in two and with the linen covering his fingers wrenched the man's hands apart. Something small and glistening fell from the hands and rolled under the bench.

The Englishman bent and flicked the article into the open. With a sudden gust of rage he made as if to crush the thing with his foot; then changed his mind and rolled the article into a piece of paper. In his hands he held the Green Pearl. Whistling thoughtfully, he carried it to the window and made a careful examination. For some seconds he rolled it from side to side, on the paper; a grim smile forming on his lips.

The opening of the lift gates behind him caused him to turn swiftly. He crushed the Green Pearl into the paper and slipped it into his pocket, as Carl Rohmer stepped on to the floor.

"The attendant at the elevator informed me that you required my presence, m'sieu?" The hotel manager glanced curiously from the Englishman to the seated figure. "Is it of the Green Pearl that m'sieu would speak?"

"Send that man down and stop all persons coming to this floor, Mr. Rohmer." Therrold spoke in an undertone.

When the manager hesitated, he added: "You don't want a scandal here, do you?"

When they were alone Therrold turned to the seated figure on the bench, beckoning the hotel manager to approach.

"Know him?" Rohmer bent down, peering into the grey face. "Mon Dieu! It is—he is—"

"Detective Browne," snapped the Englishman. "Murdered! No, don't touch him, man! There's something damned queer here."

"ON the facts, Detective Browne was murdered by Dr. Night," said Mark Therrold.

"Loose reckoning!" Superintendent Dixon grumbled. The head of the Detective Branch of the New South Wales Police was a heavily built man with a square rugged face, relieved only by keen blue eyes, shining from under shaggy eyebrows. "Thought you'd do better, Captain Therrold, with your reputation. All your facts are, that you and Browne saw a Chinese looking individual spying on you—a Chink that Browne thought he could identify with a Dr. Night who gave us some little trouble a few years ago. As to the cause of death—nothing. Can't understand what medical science has come to. We've had half a dozen deaths in this State during the past two years—suspected murders—and the doctors can't tell me what drugs, or means, were used."

"You're forgetting the presence of the Green Pearl in Browne's hands," reminded Therrold. "By the way, Superintendent, you have the pearl. I should like to try a small experiment with it."

Dixon turned to a large safe behind his desk and brought out a small box. Removing, the lid, he exposed the Green Pearl, lying on a bed of cotton-wool.

"There's the cause of Browne's death." The Englishman spoke sadly. He stooped and from a case at his feet took a live rabbit and placed it on the desk. From his pocket he took a pair of strangely shaped pliers.

"What's the game?" inquired Dixon interestedly.

"A little experiment in doctored jewels. I want to find out how close I was to death yesterday."

The Secret Service man picked up the Pearl with the pliers. "Hold that rabbit's head, please."

Very quietly Therrold brought the Green Pearl to the rabbit's nose and rubbed it gently over the nostrils. Then he placed the rodent on the office floor, allowing it to roam at will. In sudden tension, the two men rose to their feet, watching the little animal. For some time it appeared interested in the worn rug, then started to hop across the room. A derisive smile was forming on the Superintendent's lips when the rabbit showed signs of uneasiness. It sat up and rubbed its nose with its forepaws. Suddenly it toppled sideways; a few convulsive struggles and it lay still.

Therrold bent and felt the still-warm body.

"So died Sergeant Thomas Browne." The Englishman spoke with some emotion. He lifted the body into the suitcase.

"The evidence is complete, Dixon. Now we can reconstruct what happened in the hotel corridor. Some time after leaving my room, Browne picked up the Green Pearl, probably in the corridor. He held it clasped in his hand. Why he did not come back to me with the jewel I cannot yet fathom. Perhaps he was close to the elevators and sat down on the bench he sat there until he died. Take care to reason things out first. Anyway, of that pearl, Dixon. It is coated with some subtle poison that acts through he pores of the skin."

"Not very strong," Dixon grumbled. "Why, it took all of ten minutes for the poison to kill that rabbit."

"Possibly the power of the poison is disappearing by evaporation," Therrold answered quickly. "Possibly when Browne handled the pearl the drug was new and very strong."

"But you and Rohmer handled the pearl only a few hours before," objected the Superintendent.

"We handled the Green Pearl." Therrold emphasised the two words.

"What do you mean?"

"That thing is not the Green Pearl." Therrold lifted the pliers holding the jewel with an expression of disgust. "This is an imitation. Why, its weight alone gives it away. This bit of glass weighs possibly thirty grains or more and the Green Pearl's only eighteen and a half grains. I knew it was not the Green Pearl the moment I lifted it from the floor."

For some moments the Superintendent was lost in thought. Therrold lifted the pearl on to it bed of cotton wool and replaced he lid of the box. The pliers he placed in the case with the dead rabbit.

"Where is the Green Pearl, Therrold?" The Superintendent spoke suddenly.

"I should like notice of that question," the Secret Service Agent smiled grimly. "Long notice, too. For I guess I'll suggest that the Soviet agents in this city have a better knowledge of the pearl's whereabouts than anyone else."

"They're—" Dixon expressed contempt.

"That is a popular attitude towards Communism." Therrold shook his head. "Surely you know better than that, Dixon. It's all very well to express disbelief in the abilities of the exponents of that creed and to sneer at it a fad that will soon be exploded. Yet, in your heart you realise that it is a great force—one that will have to be very seriously reckoned with in the near future. We know that it is gaining fresh adherents every day, not in ones and twos but by thousands. You know that Communism, as preached by Soviet Russia, has the wealth of a powerful nation behind it."

"The Communists have no political support here. Every party is against them. They've mighty little support anywhere in the world. There's not a Government in the world that has given them anything but the most partial recognition."

"Yet the Communists have active agents in every political party and organisation." The Englishman spoke emphatically. "Even among the 'die-hard' Conservatives they have agents working for the general unrest that is to forerun the world war that is to sweep capitalists and bourgeoisie from this globe. You ask, what are they there for? To encourage unrest; to persuade the unthinking employer to press more rapidly on the working man. They're put there, and provided with capital to establish futile businesses, by the Soviet Government of Russia. Money talks. The exponents of the Third International have unlimited capital for their propaganda—not only from the Russian nation, which they now own, but from the tribute they draw from their adherents all over the world. Of course we know that quite a lot of that money sticks to the fingers of the men who handle it, but there's enough and to spare. Russia, of to-day, is the big financial centre for the world revolution to Communism."

Dixon shook his head disbelievingly.

"Of course, it is difficult for you to see it," continued the Englishman. "You Australians are living in an era of prosperity, high wages and general comfort. So long as the present standard of living is maintained at the present level there is little to fear from Communism. Let the standard of living be lowered, however, below the line where the working man will have no spare cash to play with; below the margin at which the working man's wife has to forgo the luxuries she has learned to look upon as necessities—and the Soviets will quickly gain adherents."

"Some people would say that you were preaching Communism, Captain!" Dixon laughed.

"There are many rich and powerful men in Sydney who do more than I do to help along the Soviet revolution," Therrold continued. "Let me instance. Some little while ago a body of Australian employers went to the Arbitration Court pleading that the working man required but two shirts a year, and the working man's wife needed only one new dress in every four years. That plan, did more to help Communism among the working classes than all the sermons and speeches delivered in your Domain—more than a whole year's income of Soviet Russia could command."

"There's no Communism in Australia," asserted Dixon, doggedly. "A few talkers, that's all."

"Keep the workers employed and amused and they won't heed Communism," laughed the Englishman. "I've spent five years in Russia, studying their methods: They can only succeed where there is poverty, discontent and envy. While the worker has a neat, comfortable home, plenty of clothes for his family, money for a fair amount of amusements, he won't listen to anything that suggests a change. Why, man, the Communists themselves acknowledge that. They openly state that there can be no revolution unless the workers are starving and discontented. You can hear that any Sunday afternoon in the Domain. But, go among the crowd that cheers the speakers and tell them there's a bookie up the street who is paying greater odds on the favourite for the next big race than is general, and that crowd will melt like snow before the sun. Why? Because they've got money to burn—and while the workers have that Communism can knock at their doors in vain."

Picking up the suitcase, Therrold turned to the door. On the street he hesitated. He had to get rid of the dead rabbit—and he would have to wait until nightfall to do that. He turned and went back to the hotel. Too restless to remain indoors, he came out on the street again. Pangs of hunger reminded him that he had missed his midday meal. He glanced at his watch. It was past three o'clock. He half-turned to retrace his steps to the hotel, then halted. He did not want to go back here; the place held too many unpleasant memories.

At the foot of Hunter Street a sign above a door attracted his attention. It advertised a first-class restaurant. The place looked quiet, and that was what he wanted. He ascended the stairs and looked about him. There was only half a dozen people in the room. He sauntered across to a table. He ordered a meal that made the pert waitress raise her thinned eyebrows, then sat back to await its arrival. He had much to think over.

The Green Pearl had to be recovered, and he had but one solitary clue to the theft. That clue pointed to Carl Rohmer, the hotel manager. He was certain that the man could explain the disappearance of the pearl, if he chose. True, the search of his office had proved abortive, but the pearl was small and easily hidden. There was the girl behind the screen to be taken into account; and the Asian and the girl who had peered into his room while he had talked with Browne. That girl—

The crash of broken china brought Therrold from his reverie. A lady rising from an adjacent table had swept some crockery to the ground. The waitress hurried forward and the lady opened her purse to pay for the damage, accidentally dropping a book she carried. Therrold stooped to retrieve it. As he handed it to her their eyes met. The Englishman stared at the girl in blank amazement. It was the girl who had searched his room the previous night—the girl who had been with Dr. Night a few minutes before Sergeant Tom Browne died.

THERROLD only betrayed surprise by a sudden setting of the muscles of his face. As the girl took the book from him he bowed and turned indifferently away. But the desire for the meal had now left him. He watched the girl keenly, yet very puzzled. When she had taken the book from his hand she had looked straight at him. She must have recognised him, yet not for a single moment did she betray recognition. He watched her walk to the door. As she disappeared down the stairs, Therrold suddenly beckoned the waitress and obtained his check. Avoiding any appearance of hurry, he went down to the street. The girl was not in sight.

For some moments he searched the street in vain; then returned to the restaurant. The waitress stated that she had never seen the lady before. Therrold then sought the manageress. A carefully garbled tale, with a grossly untrue sentimental motif, resulted in a promise that if the lady again visited the restaurant the Englishman should be immediately advised.

Therrold left the place, cursing himself for a fool. He had been daydreaming and had let a valuable clue slip through his fingers. If he had watched more closely he would have recognised the girl immediately he had entered the restaurant. Then he could have turned back to the street and watched. When the girl left the place he could have traced her, unobserved.

In Pitt Street, Therrold caught a tram to Bathurst Street and walked up towards Hyde Park. At Railton Chambers he went up to the third floor halting before a door bearing the name and designation "Martin Thorne, Foreign Agent."

Entering the general office, he asked for Martin Thorne, using no courtesy title. The clerk looked up quickly, then, without a word, went to the inner office. He returned almost immediately and lifted the flap of the counter, in invitation. A nod indicated the inner room.

A short stout man with a ruddy, clean-shaven face, looked up at Therrold. For half a minute the Englishman stood in the doorway, then entered and placed his hat and stick on a side table. He turned to the man behind the desk.

"Martin S. Thorne?" The Secret Service Agent slightly emphasised the "S."

"Ah!" Thorne raised his brows. "You are?"

"Mark Therrold. And you?"

"B13." The words were scarcely breathed.

"Good." The Englishman held out his hand. On his palm lay the strangely shaped gold disc. Without a word the head of the Australian Branch of the British Secret Service indicated a chair beside the desk. Therrold seated himself, leaning forward. He traced an intricate pattern on the desk top. Thorne smiled. "I heard you were in Sydney," he said. "I hardly expected that you would come here. Is there trouble?"

"The Green Pearl has disappeared—stolen." Therrold spoke without emotion.

"Not for the first time, I believe." The stout man slipped down comfortably into his chair. "Suppose you want help. You know we're short-handed here."

"One good man will do. I must have someone I can depend upon during the next few days. I suspect the manager of the hotel—he, alone, appears to have had the facilities to annex the pearl. Who he is working for I have yet to discover. I know the Soviet agents in Sydney have been instructed to recover the pearl at any cost. Then, there is a mysterious Asian who appears to have an interest in the jewel. His name is Dr. Night. But, you know the pearl's history. I want someone to watch my room."

"But you say the pearl has disappeared." Thorne looked up inquiringly.

"That is right." The Englishman hesitated. "Yet I believe that my room will be searched again by both groups interested in the Green Pearl. Of course, an agent of one of the groups has the pearl. The other group, possibly, does not yet know that the pearl has passed from my possession. I want to know and identify, the active agents of both parties. Then—"

The Secret Service Agent hesitated.

Thorne opened his eyes questioningly.

"A girl entered my room last night. I believe she was after the pearl. After the jewel had been stolen from me I saw her watching me through the half-opened door of my room. With her was Dr. Night. This afternoon I saw her in a restaurant in Hunter Street. Unfortunately she got away too quickly for me to follow. I have arranged to get word if she returns to the restaurant. I want her traced. I want to know her connections with Dr. Night." Therrold paused, to continue in a graver tone. "I warn you, Thorne, your man will be sitting in on a dangerous game. Already Detective Browne has paid the penalty for attempting to assist me. Your man will be in danger from the jump-off, for he will be a menace to both groups, as I shall have to use him as a screen behind which operate."

Again he paused.

"I don't think that I am in much personal danger, for the moment. One group has the pearl and has no reason to act against me, unless I get too closely on the pearl's tracks. The other group might even protect me; a kind of double chance of getting the pearl from where it is now. Understand?"

"Well?" Again the chief unclosed his sleepy eyes.

"Your man had better act apart from me, for a time—until I give him different instructions. I will find some way to communicate with him as occasions require. Of course, we can recognise each other as guests at the same hotel. That's all, I think."

"The message from the restaurant—in regard to the girl."

"That will be a telephone message. If I am not in the hotel the slip will be placed in my room by one of the pages. Your man will have a key to my room and will get the message as soon as possible and act as he considers best." Thorne nodded. He sat up and drew the telephone to him.

"Hotel Splendide?" He spoke after obtaining the connection. "Yes? Captain Leslie Thomas speaking. I shall arrive in Sydney this afternoon. Will you please reserve a room for me. No. Yes. I have been advised to ask for No. 519. Well, if I can't have that one—what? No? 520? Yes? Oh, opposite 519. Yes, I suppose it will do. Right. Book it, please. Yes, Captain Leslie Thomas." The stout man hung up the receiver and turned to face Therrold.

"No. 520 will suit us, I think. Opposite your room. You'll remember the name—Captain Leslie Thomas. His own name; we find it best to use our proper names, if possible. Tall, fair man, with a small military moustache. Good stand, and has his wits about him. Should suit you. M'm! Well, Therrold, am I to know the full story?"

Therrold nodded. For many minutes he spoke in a guarded whisper, recounting his adventures from the day he left London for Russia. When he came to the point where he landed in Sydney and went to the Hotel Splendide the Secret Service chief became more markedly attentive. As the Englishman finished his account of the search of Rohmer's office, he interrupted:

"Let's straighten that out, Therrold. You say you took the pearl in to the office and placed it on the desk before Rohmer. The only door to the office was behind you. Before you were the windows and the desk. The Japanese screen was on your right. You are certain that Rohmer, the girl and yourself were the only persons in the room. The girl never came near the desk until after the pearl had disappeared. Rohmer was the person closest to the pearl—closer than you, in fact. You allowed no one, except the police, to enter the room until some time after it, and you three persons, had been thoroughly searched. Ergo, the pearl was in the room all the time—and after you left it."

"So?"

"You are certain that Rohmer could not have thrown the pearl out of the window?"

"I was facing the windows all the time. Again, he would have had to chance losing the pearl. The windows open directly on to the pavement."

"Then the windows are discounted. You say the room was effectively searched?"

"Very effectively." Therrold spoke decidedly. "Constable Browne was an experienced and thorough man. The room was thoroughly searched."

The chief meditated a moment; then cleared the centre of his desk with a sweep of his hand. Picking and choosing from the common articles, he questioned Therrold as to the places they occupied on Rohmer's desk. At length he had the scene set to his satisfaction. "Does Rohmer use a fountain pen?"

"Don't know."

"Ink well on desk?"

"Yes." The Englishman thought a moment. "Rather a wide-mouthed one—open; you know the sort of thing I mean."

"Very handsome carpet on the floor, I think you said?"

"A very fine one. Old Turkey, I should say."

"Then Rohmer was in luck that you didn't guess his trick." Thorne smiled secretly. "Yes, I'm certain that if you had guessed you'd have emptied that inkwell over his handsome carpet."

"What do you mean?" Therrold stared curiously at the man.

"You'd have found the Green Pearl—if you had emptied that inkwell over Rohmer's very handsome carpet." The chief laughed gently. "Clever trick! Just waited his opportunity and slipped the pearl into the ink well. That man's got brains. Pearl under your eye all the time and you and the police searching the room. Very, effective!"

Silently the Englishman cursed himself for a simple fool.

"Never thought of that, eh? Probably would though, if you'd tackled the problem as you gave it to me just now. One's apt to get hot at the moment and miss points. Still, you did well, Therrold; don't see how you could have acted better. Now, I've got some information that may help. At the same time you mustn't rely on me too greatly. You know you've been permitted to use your position rather largely on a private matter"—the B.G. winked the other eye—"but, then, there are limits.

"I had word from—you know." The chief made a slight motion with his hand. "To give you what assistance I could. You understand, of course, that we are greatly hampered here. Men and money are both lacking. You know what the Home Government is—get results without cost. We get little or no help from the Federal Government—they've got a police of a sort—remarkably inefficient. You'd better rely on the ordinary police for detail work. I'll have word got to Dixon to help you all he can. Now, get out! It was dangerous for you to come here—for you're being watched. Still, you had to risk it. I'll pass the word to London and if you want to communicate with me, tell Thomas. Good luck, man!"

Again in Bathurst Street, Therrold looked at his watch. It was a little after five o'clock, almost too early to return to the hotel and dress for dinner. He sauntered down to Pitt Street, determined to call in at the restaurant on his way to his hotel, to find out if they had learned anything about the girl. A few yards from the Market Street intersection he stopped so abruptly that several people bumped into him.

He was staring across the road at the corner of the block known as "Fashion Row." A moment's hesitation and he crossed the road and sauntered more slowly towards King Street. Before him, utterly unconscious of his presence, walked the young lady of the restaurant—the girl who had entered his rooms the previous night.

Therrold sauntered on, certain that the girl had not seen him or, if she had, did not know that he had recognised her. She was walking slowly, stopping every few yards to examine some shop window. At the King Street corner she turned abruptly and retraced her steps.

The Englishman felt caught and wondered if she would speak to him, but she passed without a sign of recognition. Again, at Market Street, she turned up towards Hyde Park, crossing the open lands to the Oxford Street corner. Here she had to wait a few minutes before the traffic at the five ways intersection allowed her to cross to the opposite side.

In Oxford Street she quickened her pace and about three hundred yards up the road entered a small antique shop. Therrold wandered if the girl lived there. He determined to wait. In about a quarter of an hour the girl emerged from the shop and walked to a tram stop. There she boarded a Bondi tram.

Impatiently, the Englishman looked for a taxi. He would follow the girl and discover where she lived. Then, another thought came to him. What had the girl been doing in the shabby shop? Telling the taxi driver to follow, he walked to the antique shop window. The shop door was open and Therrold hesitated whether to enter or not.

He could see a slatternly woman, lazily wielding a feather duster amid a motley collection of antiques. As he watched she called on someone in the rear room, and the man came into the shop. He spoke to the woman and then went to a corner and switched on the shop lights. As the man turned again to face the woman Therrold started in surprise. The man, evidently the owner of the shop, was an Asian—in every point answering to the description detective Browne had given of the master crook, Dr. Night.

THERROLD awoke late the next morning. It was a Sunday and the weekend newspapers lay on the floor, before the door. Dressing leisurely, he went down to breakfast. During the meal his thoughts turned to the incidents of the previous day. He had had big luck, in spite of the loss of the Green Pearl. He had found the lady of the night—and she had led him to the lair of the one man he had always feared—the man he now knew to be Dr. Night. Yet the mysterious Asian had not the Green Pearl. Therrold was certain of that.

If Rohmer had acted for the Asian in the theft of the pearl, then the murder of detective Browne had been wanton violence, totally at variance with the character of the Asian, as described by Superintendent Dixon and detective Browne. Both men had insisted that Dr. Night would not use violence, except as a last resource.

That Dr. Night had returned to Sydney after his escape from the police two years previous, was remarkable. That he should live in the same police district—a district where the police would retain a vivid remembrance of him—was astounding daring.

Why had the man returned to Sydney? Why had he been about the Hotel Splendide at the time when the Green Pearl was stolen. Therrold was certain that the man was after the pearl; but he had not obtained it. Therrold was inclined to believe that Rohmer still had the pearl; that for the present he would retain it, too frightened to try to pass it on to those who employed him. Who were the hotel manager's employers?

Now that he had traced down Dr. Night and the "lady of the night," the Englishman had little doubt. Rohmer was an agent of the Russian Soviet, perhaps not directly but certainly one detailed to obtain the Green Pearl from him. A scheme formed in the Secret Service Agent's brain to lure Rohmer into his room. It would be easy to overpower and search him—but would the man dare carry the pearl on his person?

The previous day Martin Thorne had cleared many points that had puzzled Therrold. But he had not been able to explain the red-chalked 'IV' that had so mysteriously appeared on Rohmer's desk.

If Rohmer had stolen the pearl, then he had made that strange chalk mark. Therrold remembered that Rohmer, himself, had discovered the sign. He remembered that the man had been shifting aimlessly around the room while he had been talking to the detectives. He could not remember if a red-chalk pencil had lain on the desk—but the man might have had one in his pocket.

Sergeant Saunders would not have considered a red pencil an article of suspicion when he searched the man—but the search was long before the sign appeared on the desk and the drawing of the 'IV' would not take more than a couple of seconds.

Leaving the restaurant, Therrold went to the elevator doors. Before him was standing a tall, fair man, a small military moustache decorating his upper lip. As Therrold waited, the man turned and surveyed him, screwing a monocle into his left eye. He gave no sign of recognition; yet the Secret Service man was certain that he was Captain Thomas. The description Thorne had supplied was exact. When the lift came to the floor, Therrold held back, allowing the fair man to precede him. At the fifth floor the Englishman was compelled to alight first, being close to the door of the cage. The fair man followed him on to the corridor.

Passing Therrold, the man walked quickly down the corridor, to stop before room 520 and fit a key into the lock. The man acted ostentatiously, as if he was trying to attract Therrold's attention to his acts. As the Englishman halted at his door the fair man looked back, and winked. As Therrold entered his room he stopped abruptly. Someone had been in his room while he had been in the restaurant. The Sunday newspapers still lay on the floor, where he had thrown them, but on the table, under one of the windows, lay another newspaper. It was opened at one of the central pages. One of the advertisements had been outlined in red ink. The Englishman read the advertisement. It was notice of a meeting to be held that evening at a small hall in Sussex Street. Comrade Vivian Atkins was to deliver a lecture on his visit to Soviet Russia.

Who had placed that newspaper in his rooms? Whoever had done so was evidently anxious that Therrold should know of that lecture. Had the newspaper been brought to his room by Carl Rohmer? That was possible; but what reason lay behind the act? What connection lay between a lecture on Soviet Russia, in Australia, and the Green Pearl? Therrold's thoughts flew to the man in the opposite room. Had he watched for Therrold to go down to the restaurant and had then come across and left the newspaper on the table? That theory appeared reasonable.

He believed the man to be Captain Thomas who was to help him in his task of recovering the Green Pearl and Thorne had said that he possessed information that might be of value to him. He had told the Secret Service chief that he did not want Thomas to recognise him until he gave the signal. Had the man taken the newspaper as a means of conveying certain information?

The Englishman strolled leisurely into the corridor. As he turned to lock his door he whistled a few bars of a quaint melody. A moment and Thomas' door opened and the fair man came out. As Therrold turned from the door they collided slightly. "By Jove, old chappie! Awfully sorry, and all that!" Thomas picked up his monocle and screwed it into his eye. "My fault, you know."

"'Fraid I must accept some of the blame." Here Therrold grinned amiably. "Hope I didn't hurt you?"

"Please don't mention it, old chappie." Thomas hesitated. "Do y'mind if I ask if you're English? I am, y'know. Quite a few of us in this 'better 'ole,' don't y'know. Beastly bore, Sunday, what? Nothing to do and all the time to do it. Eh, what?"

"It is dull," agreed the Englishman. "I've been wondering how to put in the time. Mess about the lounge, I suppose."

"Oh, I say!" The Australian appeared staggered. "How beastly awful. Now, I try to improve my mind, y'know. Only time during the week, I assure you. There are dandy meetings in this town, Sunday nights. Serious, old bean! It's the thing, y'know! They all do it. Shouldn't be surprised if they had to. Act of Parliament, and all that. It's a Labor Government, y'know. Strong on improving the mind of the proletariat, and so on, y'know."

So Thomas had left the newspaper in his room. It was a clever trick and one not likely to be suspected by the hotel servants, if they had had entered the room. An hour in the lounge wearied the Secret Service Agent. Thomas had disappeared or he might have started an acquaintanceship with him.

He sent a page for his hat and stick and wandered into the city. There were few people about and they wore a dejected air. Therrold turned into Hyde Park and then through the park to Oxford Street, and up to the antique shop. The door was fastened and from what he could see, there was no one in the shop. For some minutes he stood scanning the dusty articles in the window. Then suddenly he stiffened.

At one end of a glass shelf was a small enamelled box—the exact replica of the box in which he had carried the Green Pearl. He had thought his enamelled box unique. He knew that the Green Pearl had rested for centuries in a similar box, among the Russian Crown jewels. So far as he was aware the box was still in the possession of the Soviet Government. He had tried to get possession of it and had failed.

While passing through China he had chanced to be of service to a mandarin of high rank. The nobleman had been grateful and had opened his treasure house to the Englishman, asking him to select from the array of exquisite bijouterie and jewels a souvenir of their friendship. To his surprise Therrold had seen there a duplicate of the box in which the Green Pearl had so long reposed, in Moscow. He had selected the box, deeming it to be of ordinary value.

To his surprise the mandarin had hesitated. Therrold had immediately withdrawn his choice. The Chinese had, however, insisted on him accepting the box. In answer to his question, Therrold learned that the box was a relic of some long-forgotten empire and that it was held in great veneration in the district.