RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

THIS book is a product of a collaborative effort undertaken by Project Gutenberg Australia, Roy Glashan's Library and the bibliophile Terry Walker to collect, edit and publish the works of Aidan de Brune, a colourful and prolific Australian writer whose opus is well worth saving from oblivion.

Aidan de Brune in this dramatic article has endeavoured to reconstruct the Marrickville Murders from details and theories gleaned by a week's study of the district and the habits and the friends of the murdered women. Time alone may tell if the story, as told here, is a faithful recital of the facts of that fateful night. In any case the theory that is the basis of the deductions is quite feasible.

"IT'S up to you, Tom." Jos. Petersen, confectionery manufacturer, stamped angrily up and down his small, boarded office. "I ain't sayin' it's your fault she hasn't paid. Perhaps you ain't pressed her enough—you're fair soft-hearted. But she's got th' money! Oodles of it!"

"What do you want me to do?" The young, tall, smart traveller glanced sullenly at his employer. "If the old girl won't pay when you want—"

"Won't?"

"Oh, well, she hasn't said she won't, but—" The man shrugged his shoulders.

"She's hard."

"Hard!" Petersen laughed. "Say, those two women are the softest marks in the district. They listen to all the tale-tellers. Money to burn, if all the tales that are told of their lendings is true. What I want to know is what are you going to do about it?"

"What do you want me to do?' The sullen expression swept again across the young man's face.

"What's the good of acting sulky, Tom?" The confectioner patted the youth on the shoulder. "You ain't got nothin' much to do this morning. Why not go over to the old girl an' 'ave a heart to heart talk with her? Tell 'er I want the cash. If you can't get it I'll go over myself."

The young man turned abruptly towards the door, shielding from the old man the look of alarm that had come to his eyes. If Petersen went to Marrickville?

"Don't act nasty, Tom." The confectioner mounted the high stool and turned the pages of a ledger. "Money's money, y'know. 'Sides the old girl's been running for quite a time. Year or so ago she paid spot cash. Can't make out what's changed her."

The door slammed heavily. In the yard the young traveller turned up the collar of his overcoat. Out of sight of the confectionery factory, Tom stopped and pulled a shabby pocket-book out of his breast-pocket and turned the leaves. One page was covered with a series of small amounts. He totalled them, breathing heavily. Miss Vaughan owed Petersen twenty-seven pounds odd. No. He owed Petersen that amount. He had taken it from the money he had collected on behalf of Petersen from the little elderly woman in Marrickville Road.

Stuffing the book back in his pocket he strode to his mean lodgings. He looked round the room vacantly. The torn wallpaper, the old, battered furniture he called home, were not pleasant to look at. Well, he wouldn't see them much longer. Monday morning he would have to go to Petersen and tell him he had taken the money. Petersen would call the police. He would be arrested; dragged through the streets to the police station.

Abruptly he started to his feet and strode over to the rickety chest of drawers. Yes, it was there! He pulled out something, held it in his closed hand. On his palm lay a small, snub-nosed revolver. He remembered the day he had bought it. He had just commenced work with Jos. Petersen. He had seen the gun in a second-hand dealer's window and had purchased it. He would want a gun to safeguard from thieves the large collections he would have to make for his employer. As the days passed he had ceased to carry the gun. The sums of money he carried to the factory were small, insignificantly small.

Thieves! Thieves! He was a thief! He had taken the money paid to him by the little woman living in Marrickville Road. Before his eyes rose a picture of the two women and their little shop. He lived again the day he had called there—bedraggled and soaked by the fierce, sudden downpour of rain—coughing heavily. They had exclaimed in horror and sympathy, dragging him behind the counter to the small table in the corner. A few minutes and he had been gulping down hot soup and tea; feeling the warm blood coursing again through his half-frozen veins.

"Tom! Tom!" On the landing stood Jerry, a fellow-lodger in the house. "What are you doing this afternoon, Tom?" The bright-faced youth on the landing laughed at the long face of his chum.

"Nothing!"

"Don't be a mug. I've got tickets for the races to-day. Come on!"

The races! Tickets for the races! Tom turned into his room, feeling in his pockets. He knew the confectioner trusted him. If he went to him on Monday with money in his hand? If he could not produce all that was owing—that would not matter. If he could win half—yes, not less than half! Say a tenner! Yes, that would, do. If he lost—Well, the same way out of trouble still lay open to him. He would not want money on that road.

"Aw! Come on, Tom, I'm flush today. We'll have a drink. That'll put you straight."

Dazed and unquestioning, Tom followed his friend. The raw spirits taunted him. He drank another and yet another. Insistently he put the money question from him. He raced Jerry for the tram, laughing and talking noisily. He couldn't lose! His tide of luck, commencing with the first race, had at last turned. At first he had betted cautiously. A few races and he had thrown caution to the winds. Then luck changed. He began to lose steadily and consistently.

Some men standing behind him had spoken of a horse that couldn't lose the last race. He waited for it, his face white and fixed. Immediately the betting opened he drew his remaining money from his pocket and thrust it at the bookmaker. With his heart in his mouth he stood and watched the horses line up at the barrier. Jerry was talkative, but he held silent.

"Who won, Jerry?"

The youth's answer silenced him.

"I'm going." He turned and plunged through the crowd towards the exit gates. Once he felt Jerry's hand on his arm and shook it off roughly. "Get on home, Jerry."

He stopped some little distance from the crowd surging toward the line of tram-cars.

"Where are you going, Tom?" The youth spoke in a low voice. "Lord, you were a fool, Tom. Lost your bundle?"

"Every cent in the world!" He laughed hoarsely. "No, not that!—I've got a shilling or two, somewhere."

"I'm going to stick by you, Tom. You're not well?

"I am well."

He turned angrily on the youth. "I tell you, you can't stick. I've got to see—see someone."

"I've got a quid or two—"

"I'm not borrowing from you, Jerry. You're like me, hard up at it. No, I'll borrow from someone who's got plenty."

He turned from the trams, walking fast, not knowing or caring in which direction he went. Once he stopped and looked around. Jerry was standing where he had left him, looking after him. He was going to borrow! No, he was going to give—to give the life he had fooled and degraded. Again his hand sought his pocket, feeling the cold steel with savage satisfaction.

The by-road was rough. Yet he walked on swiftly. He did not know where he was going; he did not care. Any place would do for the last act of his life—his life of twenty-three years! He laughed aloud. Morley! He turned swiftly as two men passed him. What were they talking about? Money! Oodles of money! Oodles of money!

Petersen had said the old women had oodles of money! They had been kind to him. Petersen said they were easy on hard-luck tales! Should he go to them and ask them to lend him the money? Why not? They would listen to him, even if they refused. Would they refuse? Well, what if they did? There was still the "thing" in his pocket! He turned into the Marrickville Road and walked in the direction of Dulwich Hill. He asked the time of a passing man. It Was just a quarter past ten. Yes, Miss Vaughan's shop would he open. They stayed open late on a Saturday night. Little Miss Vaughan and her sister! Yes, he would, tell them everything. It would be easy, and perhaps good for him. They would give him the money and he would repay them—somehow!

Passing the Town Hall he kicked against something lying on the pavement. He looked down. It was a black thing—with a piece of broken elastic attached to it. He stooped and picked it up. Then laughed. There was a carnival dance in progress at the Town Hall. Someone had lost his mask. He turned it over curiously on his hand as he walked on. Once he lifted it to his face, peering in at a darkened shop-window. But he must get to Dulwich Hill quickly or the shop would be closed. Miss Vaughan would lend him the money. But if she would not? If she refused, repulsed his persuasions, would he have to tell Petersen, or—

In one of his pockets he found a piece of string. Mechanically he joined the broken elastic. He slipped the mended mask into his pocket. For a moment his hand rested on the revolver—so cold and silent, yet so potential.

If the woman would not lend him the money? He knew where they hid money in the shop. Only the previous week he had watched Miss Vaughan go down on her knees behind the counter and draw a tin of notes from beneath the window. She had paid him for some goods from that tin.

A thief? Well, wasn't he a thief? He had stolen from Petersen—or—had he stolen from Petersen or the women? He tried to think. He looked up. At the top of the hill he could see the line of darkened shops. Again his fingers sought the mask. With that on his face and the gun in his hand! Who could recognise him? They were only two old women and he must have the money.

No, he wouldn't take it for good, but he could have no refusal. He dared not ask for the loan. He dared not chance that the women refuse. He must have it; he must take it. Somehow—some way, he would get it back to them. True, they, would be frightened, but he would do them no harm.

A few yards from the door of the shop he stopped and drew the mask from his pocket. As he lifted it to his face he started. God! What was that? He turned swiftly. Only a tramcar, running to the terminus, some three to four hundred yards up the road.

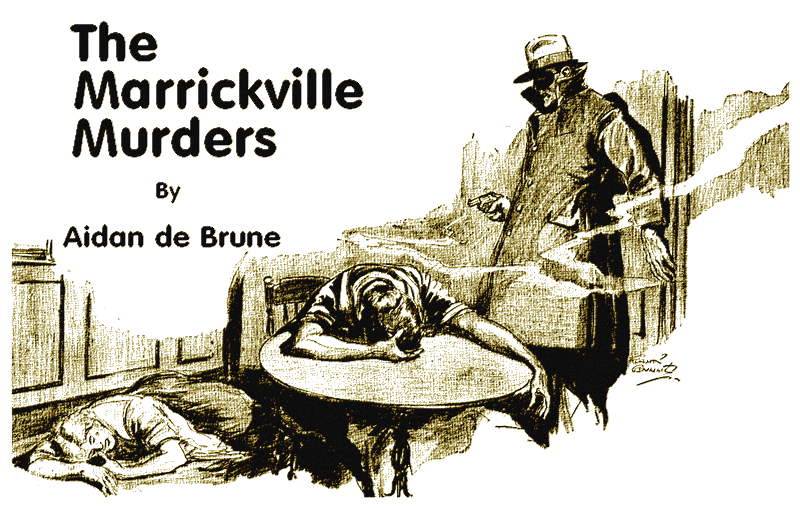

Impatiently he drew the mask down, covering his face. He lugged the revolver from his pocket and strode to the door of the shop, swinging it open. He could see Esther Vaughan standing behind the counter, taking the money from the cash register. Far down the shop he noticed Sarah Falvey's head showing above the end counter. She was sitting at the table where he had sat—the day they had brought him back to life, feeding and mothering him.

"Hands up." At the hoarsely growled words the little elderly woman behind the counter turned swiftly. "Utter a sound and—"

"What do you want?" The old voice quavered. "Who are you?"

"Get down to that table. Hold your tongues and I won't harm either of you. Speak, and—" He waved the revolver.

For a moment he stood with his back to the closed door carefully examining the shop. Where was the money? For the moment he had forgotten. He looked round the little shop, speculatively; a feeling of cold resolution steadying the hand holding the revolver. Ah! He remembered.

At the shop window he bent down, feeling blindly into the dark space.

His hand encountered a tin.

He drew it out. Yes, that was the tin he sought; the tin from which the woman had taken the notes. Still covering the women with his revolver he knocked off the lid of the tin and looked down. Yes, he had found the money he sought; sufficient for his purpose.

The sound of rustling skirts caught his attention. He straightened himself, abruptly. Sarah Falvey had darted from behind the end counter and was running to the front door. With a bound he sprang over the counter to the centre of the shop, but the woman had passed him.

"Stop, or I fire!" The woman stopped suddenly and turned to face him, a dawning wonder in her eyes. She bent forward, peering closely at him. What had he done? What had he said? A sudden panic seized him. For a moment he stood, wondering. He had spoken in his natural voice; the voice that both women knew well.

Somehow he must stop that look of dawning recognition in Sarah Falvey's eyes. "Get back! Get back, or I fire!"

"Esther! Esther!" Sarah Falvey spoke in terrified wonder. "Esther! It's Tom!"

"Open that door! Open that door!" Again his voice slipped. He ran towards the woman, now standing with arms outstretched to bar his passage. "Esther! It's Tom—"

A short, sharp crack and the woman answered with a little sobbing cry. She swayed a moment on her feet, then staggered to a chair beside the door, sinking on it in a huddled heap. He looked from the woman to the gun in his hand, in silent wonder. What had happened?

"Sarah! Oh, Sarah! What has he done? Oh, you've shot her; you've shot her!"

He turned to face Esther Vaughan, running from behind the counter to her sister's aid. Almost as the woman's hands were on him he raised the gun again. What was she doing?

He felt her catch the barrel of the gun in her hands. He tried to pull it from her; to turn to the door and escape. The woman struggled to possess the weapon. With a savage growl he tugged at the butt. Suddenly the woman collapsed, falling to the ground. He stood, looking from the woman crouched in the chair by the door to the woman lying under the shadow of the counter. Had he shot them? No, no! He had never intended that!

With a cry of terror he thrust the gun in his pocket and snatched at the mask covering his face. He wrenched open the door and strode out into the street. A man stepped suddenly from his path, pushing before him a woman and some children. Through the darkness of the night he staggered on, circling the district; making for the one refuge he had, the room he called home. In his room he flung himself on the bed, panting and exhausted. Suddenly, he was aroused by a knock at the door.

"There, Tom?" It was Jerry's voice.

"What's up?"

"Thought I heard you come in some time ago. I came and knocked but you didn't answer. I could hear you breathing, though. Breathing hard. Catch a cold at the races, to-day?"

"Bit of one. I'm all right, Jerry."

"Get that oof from your pal?"

"Money!" He checked himself hastily. Then laughed harshly. "Oh, yes, Jerry, I got the money. Oodles of it! Oodles of it!"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.