RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a stained glass window at St. Anne's Church, Nuneaton

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a stained glass window at St. Anne's Church, Nuneaton

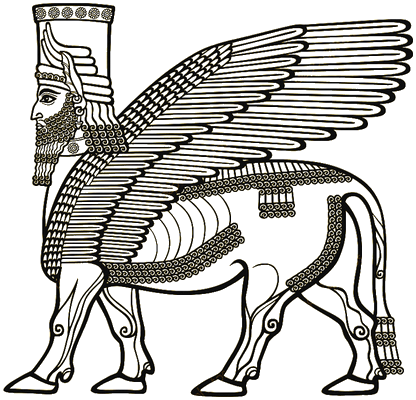

"The Winged Bull," Williams & Norgate, London, 1935

For of old the Sun, our sire,

Came wooing the mother of men,

Earth, that was virginal then,

Vestal fire to his fire.

Silent her bosom and coy,

But the strong god sued and pressed;

And born of their starry nuptial joy

Are all that drink of her breast.

—William Watson

HERE was a sky-fog in Central London that made the heavens look like dirty metal and caused the street lamps to be lit at three o'clock in the afternoon. The British Museum, seen across its hazy forecourt, looked like the entrance to Hell. Ted Murchison had no wish to return to his brother's house at Acton before the hour of the evening meal. He disliked his sister-in-law, and the house was full of kids that needed a spanking and didn't get it. He turned in at a gateway in railings that dripped soot and fog-dew, and set out across the wide expanse of gravel in the gathering gloom.

It suddenly struck him as he mounted the steps of the portico that if the fog grew worse he would have the devil's own job recrossing that wide expanse without any landmarks. But he didn't care. He wasn't going back to Acton to kick his heels till supper-time. The Museum would be warm and lighted, and would give him something to think about and distract his mind from the memory of the interview which had just ended. He had gone up for that interview on a personal introduction from his brother, and had failed to get the job. Now he had to go back to Acton and tell his brother that he had failed to get it, and hear his comments on the failure. And his sister-in-law's comments, too. She was a strong believer in kicking a man when he is down as the best way of helping him to rise.

A rush of hot air smote him in the face as he entered the building. It was warm, as he had expected, and he was glad of the warmth, for there was no overcoat under the old trench-coat that he wore. A relic of the War, it had been good in its day, and had outworn a succession of cheap overcoats. Coats like that did not come his way nowadays. His father had been a colonel in the Old Contemptibles, and one of the first to fall. He himself had joined up straight from school. When he came out of the army there was no money to give him a start in life, and no one to care whether he had a start in life or not. So he took the first job that offered, and when that proved to be a blind alley, took the next one; and as that was a shady employment agency, he came perilously near gaol before he tumbled to what was afoot.

So the years had gone by. Clerking without shorthand. Salesmanship on commission. Anything and everything that would enable him to hand over thirty shillings a week to his sister-in-law at Acton. In normal times he was the type that goes out to the Dominions, but the Dominions were not taking men without capital during the post-war depression. His brother never proposed advancing him the capital. Thirty shillings a week is not to be despised in the home of a clergyman whose principles oblige him to bring into the world an annual baby, whether he has anywhere to put it or not.

With demobilization Ted Murchison's halcyon days were over. He had been an officer and a gentleman, even if a very young one. Digging out the old trench-coat to wear in this drizzling fog had turned his mind back to those days. He had been lucky in his colonel, and his year in the army had done something for him that churches and universities between them had failed to do. As he handed over his hat and coat to the attendant in the muggy warmth of the Museum, he speculated upon what had become of the rest of the members of his mess. Had any of them missed the boat as he had, or were they all getting on in the world and raising families to fight in the next war? Marriage had been out of the question for him, and life had not been any easier in consequence. He was thirty-three now, and was beginning to steady down. There were times when he thought he had quite steadied down. There were other times when he doubted it. The handling his colonel had given him had stood him in good stead during those difficult years and steered him past much miscellaneous trouble.

Brangwyn had been the chap's name. He wondered what had become of him. No one knew whence he came when he joined up, and no one knew whither he went when he had been demobbed. He was of the soldiering type, but was not a professional soldier. He had been a most marvellous handler of men, both in billets and in action. There was less crime and fewer casualties in his command than in any other down the line. As a lad in his teens, Ted Murchison had adored him. As an older man, with wider experience, he realised more and more clearly that his old chief was a man of no ordinary calibre.

The Museum, though warm, was not brightly lit, for the fog hung in wreaths down the long galleries and haloed the lights with a golden haze. It was not the best of conditions under which to see the exhibits, and Murchison was sauntering idly down the central aisle, lost in thought, paying no attention to his surroundings, when suddenly he was startled out of his oblivion by the sight of a face staring at him through the gloom with a curious, questioning expression, as if its owner were about to speak to him. It was a good-humoured face, though slightly cynical, and its eyes seemed to probe his very soul. They looked at each other, he and the owner of the face, without speaking. There did not seem to be any need of speech between them, for thought flowed from one to the other unchecked. He knew that the owner of the face thought he was a damned fool, but liked him. The impulse was on him to speak to this stranger, but an intuition told him that the stranger was a foreigner and would not understand the spoken word. Then he suddenly realized that the face was larger than human, and it was high above his head; he saw the shadow of a vast wing stretching away into the gloom; a vast hoof upon a plinth was planted beside his knee. It was one of the winged, human-headed bulls that guarded the temples of Nineveh that he had been communing with!

Realization gave him something of a shock. He had been so sure the beast was alive, and it had seemed to have something very important to communicate to him; something that would have altered his whole life if he could have learnt it. He gazed up into the quizzical, cynical face that gazed back so steadily, and it seemed to him as if it had a life of its own, a very definite life, despite his disillusionment as to its nature. He had a curious sensation that he had made a friend. That winged bull would know him again, in the same way that some of the beasts at the Zoo get to know visitors who have a flair for animals. He knew that by day the great bull stares out into space over the heads of the sightseers, and that it was only an optical illusion caused by the shadows which made it appear to be looking at him; nevertheless, he believed that even if he returned in broad daylight he would catch its eye, and that there would be recognition in it. He made up his mind that he would return, and return again and again to visit his new-found friend; he had a dashed sight more in common with it, graven image though it was, than with most of the humans he had known during his thwarted life. He believed the bull knew it, too; it knew he would return, it knew they had a lot in common.

Reluctantly he turned away and moved off down the gallery; an attendant was eyeing him in much the same way that the bull had eyed him, though with considerably less goodwill. He passed slowly on down the Egyptian Gallery, and the shadowy gods on their pedestals sat quietly watching him. They, too, were alive with a strange life of their own in the uncertain light of the mist-filled gallery; but they had not the energy of his Babylonian friend, nor did he get en rapport with them in the same way, though he felt their life, till he came to an enormous arm in rose-red granite outstretched with clenched hand upon its pedestal; an arm so vast that it was inconceivable what manner of statue it had come from, ending in a Hand of Power, if ever there was one.

Murchison remembered the Ingoldsby Legend of the Hand of Glory that could open locked doors; but this rose-red granite arm was utterly different in the feeling it gave him from that sinister relic. It was its benignity that impressed him; the benignity that controlled the awful power it possessed. It was an utterly different kind of god to the crucified God in the Christian churches; but it was a good god nevertheless; and it was very much of a god; let the orthodox say what they would.

Reluctantly he moved on again. Another attendant was eyeing him. It did not do to admire the exhibits overmuch or one was suspected of wanting to steal them; though how anyone could make off with that mighty, 20 foot arm was beyond imagination.

He drifted on at random up the broad, shallow stairs, and presently found himself in the Mummy Room and stood gazing thoughtfully at the desecrated dead. A scanty handful of fog-bound sightseers were gathered around the official lecturer, and Murchison joined them. The lecturer exasperated him by patronizing both the dead and the living. Were not the ancients men like unto us? he asked himself. Why should one credit them with the mentality of imbeciles? They had known enough to build the pyramids.

The party was gathered around the leathery individual lying curled up in his imitation tomb. The lecturer was explaining that the ancientest ancients buried their dead like that because that was the attitude in which they slept, and the less ancient ancients buried their dead out flat, because that was the attitude in which they slept. Murchison wondered whether they ever turned over in bed at night, same as other folk—put the question, and got snubbed.

He quitted the party, and drifted off towards the gallery where aboriginal godlets vie with each other in ugliness. But on the threshold he halted. This was altogether too much of a good thing. These, too, had come alive under the influence of fog and dusk, and he backed away, startled. The place smelt of blood.

Murchison turned and went striding away down the long galleries in search of the exit. He had had enough of these presences, and he wanted to smoke. Their effect was altogether too queer. Something in him that the dragging years had numbed into a merciful insensibility woke up and began to ache again. He thought of fighting men on the march, and longed for open spaces and high winds. He was a man, and he wanted a man's job, not this wretched quill-driving for a pittance in the dingy offices of shady concerns. Murchison struggled against a rising tide of anger with life; but it does not do to be angry with life unless one has private means, lest one's last state be even worse than one's first.

Murchison took his hat and coat and went towards the exit. As he approached the glass doors he saw that it was now quite dark outside, but it was not until he passed through them that he realized that a black wall of fog, opaque as a curtain, pressed against his face. He hesitated for a moment. Then suddenly stepped forward into the clinging, smothering darkness, which closed behind him as water closes over a swimmer.

There was no sound whatsoever in that impenetrable blackness; for not only does fog blanket sound, but all traffic was at a standstill. Murchison wondered whether the end of the world had arrived at last, after so many abortive prophecies; or whether, under the influence of his new friend, the man-bull, he had slid back to the dawn of creation, and this was the formless void before the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. He stood motionless, staring with unseeing eyes into the slowly swirling invisibility. Any moment he might see the spirit of God come through and the darkness part, and vast forms of great winged bulls formulate out of the formless mist.

Then a sudden horror smote him at the thought that it might be hideous godlets, creatures of the slime, that would formulate first. But he rejected the thought. Those things in the Aboriginal Gallery had belonged to the decadence of a race, not its prime. No, the things he would see formulate out of the mist were noble, and beautiful, and very strong.

He remembered Hans Anderson's story of the toys that came alive at night and held their revels in the moonlit nursery. The gods on their pedestals had been alive right enough, even before he had left the building. As soon as the last of the readers in the great library had been given his hat and pushed out, would they get off their pedestals and begin their revels? His friend, the door-keeper of the gods, relieved from duty, might come out and join him for a chat and a smoke in the courtyard. He wished he would. He liked him a darned sight better than any human he had ever met before, with one exception, his boyhood's idol, the colonel of the regiment in which he had held his brief commission.

Someone passed him in the smother, and, desiring to be alone with the gods, he advanced a few paces diagonally across the broad portico, felt the edge of the steps under his feet, and passed down them, setting off at random across the wide stretch of invisible gravel. A queer feeling came to him that in so doing he had committed himself beyond all possibility of return. He had left the flagged path that would have guided his feet to the gate, despite the murk, and was astray in black vacancy. He had left the lighted and landmarked ways of men and was adrift in primeval darkness. And who, in that darkness, would come to meet him? The hideous godlets? The spirit of the Ancient of Days, with a long white beard and a golden crown? Or a mighty rose-red Arm that parted the clouds and gave light? His choice fell upon the Arm. He was sick to death of his brother's God:

'A grasping de'il, the image of himsel',

Got out of books by meenisters, clean daft on Heaven and Hell.'

His brother had asked him once whether he thought God would ever forgive him for his attitude towards Him; and he had asked his brother whether he thought he would ever forgive God for His attitude towards him? Anyway, He was a spiteful brute, if all that was said of him were true; and a poor judge of human nature, for He regarded some pretty awful specimens with favour, if their statements were to be believed. Ted Murchison had had enough of Him, and He could go to His own Hell and stop there, for all he cared. He stood alone in the breathless smother and called mentally to his new friend, the winged bull of Babylon.

'I am upon your side!' he cried aloud in his imagination. 'Come to me, O winged one. Door-keeper of the gods! Open to me the doors!'

His chant ceased abruptly. By what name should he call upon his new friend? For names were needful in order that the gods might be invoked. Man-headed, eagle-winged, bull-footed, how should he name him? 'Rushing with thy bull-foot, come!' The words of the old school crib came back to him. 'Evoe, Iacchus! Io Pan!'

Murchison stood alone in the fog-bound darkness of the forecourt of the British Museum and cried aloud, 'Evoe, Iacchus! Io Pan, Pan! Io Pan!'

And echo answered 'Io Pan!'

But a voice that was not an echo also answered, 'Who is this that invokes the Great God Pan?'

URCHISON was so startled by the immediate response to his invocation that he involuntarily exclaimed, 'Good Lord!' which was the invocation of his brother's 'graspin' de'il,' and had nothing whatever to do with the deity he had been invoking with such fervour a moment ago. He heard a footstep on the gravel beside him, and held his breath. A hand touched his arm.

'You seem to have lost your way pretty thoroughly,' said a voice, and Murchison came back to earth with a bump.

'Unless you are going to call on the Keeper of the King's Books, you are decidedly wide of the mark,' continued the voice. 'Would you like me to put you on the track of the gate? I have a pretty good sense of direction. I think you will find me a reliable guide.'

The voice was that of an educated man, and it had the indefinable something that is only to be found in the voice of one who habitually associates with educated men. It was also a strangely resonant voice. He had only heard one other voice as resonant as that. Curious how his mind kept on going back to his brief soldiering that afternoon. He was so astray among his thoughts that he neglected to answer his interlocutor, and the invisible voice went on again.

'I think you had better come along with me, whether you want to or not. No, I am not a policeman, but you don't appear to me to be in any state to take care of yourself at the moment, and Christian charity compels me to lend you a hand as far as the gate. Or, since you were calling upon the Great God Pan, you may prefer to call it pagan charity. But in any case you had better come with me lest you get yourself locked in and have to spend the night in these insalubrious precincts.'

Murchison, feeling very foolish, allowed himself to be led by the arm through the darkness, made a desperate snatch at his scattered wits, and managed to say:

'I'm frightfully sorry. I am afraid you must think me an awful fool. I'm not drunk, really. I—I was just thinking of something else, and got lost in the fog.'

'Hullo? I have heard that voice before somewhere. I never forget a voice. Now, who is it?' exclaimed his invisible companion.

Murchison stiffened. He wondered what sort of confidence trick was about to be played upon him, and did not answer.

'Quite right,' continued the voice, 'never tell a stranger your name in the dark. But I'll tell you my name, however, for I am pretty certain I know you. My name is Brangwyn. Now can you place me?'

If the Great God Pan had appeared in person the effect upon Murchison could not have been more overwhelming. It took him so long to collect his wits and answer that his companion began to think that he had been mistaken in identifying him; but at last he managed to say:

'Good Lord, sir, is it you?'

'Yes, it's me all right, and from your mode of address I think you must have been one of my cubs. Now which is it? Roberts? Atkinson? Murchison? Yes, I believe you are Murchison. Am I right?'

'Yes,' said Murchison, and that was all he could find to say. When one has offered one's soul to the devil, according to all the traditions of one's upbringing, and the god of one's youth suddenly accosts one out of the darkness, the association of ideas is irresistible. Murchison had been deeply stirred by the uprushing rebellion at his thwarted life; his wits were astray in the fourth dimension and could not readily be recalled, and the sudden voice in the darkness that answered his invocation had seemed to turn all his imaginations into reality, and the old gods had verily come again for him. They were all about him, pressing in upon him; for his mind had turned bottom-side up with the shock and reaction that had caught him off his guard, and for the moment subconsciousness had superseded reason and taken charge of his affairs.

Brangwyn could not see his companion's face in the murk, but he listened attentively to the timbre of his voice, for his quick ear told him that something was very much amiss with this man, and that he was under high emotional tension. He remembered well the alert, eager youngster of the last years of the War, and wondered what the years of peace had made of him.

'How has life used you since last we met?' he asked.

'I'm still alive,' said Murchison, with a curt laugh.

A dull orange glow loomed up through the haze ahead of them.

'I expect those are the lamps by the gates. At least, I hope they are,' said Brangwyn. 'Now, if I can continue to pilot you successfully, I will steer you into a certain teashop of my acquaintance in Southampton Row and ask you to join me at a cup of tea.'

Murchison accepted with more than the eagerness that is normally due to the offer of a cup of tea, and Brangwyn wondered if he were down and out and starving. Queer things happened during the peace to fellows who had been temporary gentlemen during the War. But he was wrong. It was not food for which Murchison was starving, but something quite different.

Now that there were the street lamps and the kerb to guide them, it was easier going. Bloomsbury is a land of right angles, and it was only a matter of knowing how many streets to cross until the right turning was reached in order to find Southampton Row. Once there, the lit-up shops gave them all the guidance they needed, and in a few moments they turned into a big café whose brightness almost blinded them after the gloom in which they had been groping for so long.

Brangwyn led the way to a corner table, and for the first time was able to see the face of his companion as they sat down opposite each other.

So this is what the alleged peace had made of that fine youngster? If he had seen him in the street he would not have known him. There was a family likeness to what he had been, but no more.

He studied him closely. He was looking rather dazed and self-conscious, Brangwyn thought, and wondered what had been at the bottom of that extraordinary outcry of 'Io Pan' in the foggy forecourt of the British Museum. It was exceedingly curious that the fellow should have turned up when he did, for he had just been thinking that the type of man he was looking for was the Murchison type. Big-boned, upstanding, Nordic. The Viking breed, in fact; and Murchison, if he remembered aright, was a Yorkshireman, and therefore probably of Viking stock. He studied him closely, after handing him the menu to distract his attention from the inspection. It would not do to be sentimental because the fellow was down on his luck. Nor must he jump to the conclusion that, because the youngster had been the right sort, the man was all that could be desired. Strange things can happen to men in the vital 10 years between 20 and 30, especially in times of stress. He must be cautious, and not let impulse, masquerading as intuition, lead him astray. A mistake would have very far-reaching repercussions.

Murchison looked up from the menu, having made his choice, and for the first time met the eyes of the elder man that had been fixed on him so steadily. He, too, had been making use of the menu for other purposes than those it was intended for, and under cover of its perusal had contrived to pull himself together. Crumpets were agreed upon, and the waitress departed, leaving them alone together. They had the place to themselves, all other wayfarers having been driven home by the fog.

Brangwyn had no mind to come straight to the point. He wanted to walk round his companion sniffing before he committed himself. It would not be fair to rouse the fellow's hopes and then dash them. So he turned the talk on to old comrades and wartime experiences, and Murchison followed him thankfully, for he had no mind to be asked about himself, since he had nothing good to tell, and had no love for pitching a hard-luck story.

So they chatted contentedly over their tea and cigarettes, and Brangwyn watched the likeness to the lad he had known come back into the face of the man opposite him.

'Have you far to go tonight, before you get home?' he asked at length, when empty plates gave them no further excuse to defy a hovering waitress who obviously wanted to get rid of them and go home herself.

'Acton,' said Murchison curtly, brought down to earth abruptly by the word.

'Good Lord, you'll never get there,' said Brangwyn, secretly delighted, and grabbing his opportunity. 'Let me put you up for the night at my place. I've got bachelor quarters just round the corner. We'll brew rum punch over the fire and make a night of it.'

Murchison agreed eagerly. This was a treat beyond all expectation. Brangwyn had all his old fascination for him. He could imagine nothing more delightful than to sit up half the night yarning with him; and, above all, to meet him on an equality; for there is a great gulf fixed between 20 and 40, but the gap between 33 and 53 is by no means unbridgeable. The younger man was now mature, and the elder still in his prime.

They left the shop together, and found that the fog had lifted considerably, which was fortunate, for Brangwyn's abode was by no means easy to find, even by daylight, and he had been wondering whether he had promised more than he could fulfil in inviting his companion to go home with him.

They left Southampton Row, and went down an alley, crossed a square, and went down another alley. It was a cross-country journey, and the district was distinctly insalubrious; Brangwyn was not sorry to have a companion when he saw the lounging groups in alley entrances, for this was a night on which an assault could be committed with impunity.

Despite the slum to which it had been reduced, the district had a charm of its own, and even the extremes of grime and dilapidation of the houses could not destroy the grace of the Georgian architecture, though what the drains must be like it was better not to inquire.

They turned south, into a street of mean shops, and Brangwyn inserted a key in a narrow door beside an Italian restaurant on the corner, and entered. Sufficient light from the street lamp shone through the fanlight to reveal the worn oilcloth of the entry, and a long flight of dingy stairs leading upwards into darkness and flanked on either side by a wall bereft of handrail. It was an unprepossessing abode, and Murchison concluded that Brangwyn must also have come down in the world since the War, for he had been reputed to have money.

At the top of the stairs there was another door, and this also Brangwyn unlocked with a latch-key, though why both doors should require keys was difficult to understand, for no other entrance opened into the slot-like passage and stairs. Brangwyn switched on the light and held the door open for his companion to enter, and Murchison found himself in another world.

The entire upper part of the corner house and its two neighbours had been reconstructed, leaving the facade intact, so that there was nothing outside to hint at what was within. To all appearances the three houses were as dingy as the rest of the street, for such painting as had been done to their woodwork had been carefully matched with the surrounding grime, and dingy Nottingham lace curtains were stretched against the glass of the windows, hidden from the eyes of the occupants of the house by inner curtains of thin golden silk.

A whole floor had been pulled clean out of the corner house, making the lounge hall into which they entered spacious and lofty. A great chimney of mellowed brick, salved from the discarded party wall, occupied the rear angle of the fan-shaped apartment; on its wide, flat hearth a pile of wood and peat awaited lighting, though the place was warm almost to stuffiness with central heating. Thick soft rugs lay about on the dark polished parquetry of the floor, and a divan and two vast armchairs flanked the hearth. Books lined the walls from the floor to the gallery, supported on massive posts of old timber that had once been floor-joists, and on to the gallery opened doors that were presumably bedrooms and what house agents call the usual offices.

Brangwyn bent down and put a match to the pile on the hearth.

'I believe in plenty of fire-lighters,' he said, as the flames roared up the chimney. 'Those are the sort of little things that make all the difference to life, and you never can get women to understand them.'

'Take this chair,' he continued, 'and mind how you sit down; it is on wheels instead of casters.'

Despite the warning, Murchison felt the chair go from under him, and sat down sooner than he meant to.

Brangwyn stretched out a hand to a cocktail cabinet and drew it towards him, for it also was on wheels. Murchison noted that all the heavy furniture was mounted on small, rubber-tyred wheels, and marvelled that no one had ever before thought of such a simple device for increasing comfort and minimizing labour. He drew his great chair up to the now blazing fire with a single easy kick of his heel, and stretched out in luxurious comfort, giving himself up to his brief hour of enjoyment. This was the way a man ought to live. Solid comfort, but no show or fuss; and, above all, no servants to make themselves a nuisance and pinch the drinks. He remembered that even in the front line Brangwyn had always believed in being comfortable, and managed to be so, too, within 24 hours of the biggest push. Moreover, he believed in everyone he was responsible for being comfortable also, as being the best way to get the best work out of them.

Brangwyn was a tall, slight, dark-skinned man; and his black hair, brushed straight back from his forehead, was greying over the ears and receding over the temples. That was the only difference the years had made to him, thought Murchison, as he watched him picking and choosing among a formidable array of bottles. Murchison had never seen him in mufti before, and thought it became him better than uniform; for that ascetic looking scholar's head had always seemed rather incongruous sticking out of a tunic, though his bearing was soldierly enough.

The cocktail Brangwyn finally evolved, after much thought and care and accuracy, was amber-coloured and aromatic, not quite like anything Murchison had ever met before; but it had an authentic kick in it, as was evidenced by the sudden glow of his chilled skin and the livening up of his dazed brain. It amused him to observe that Brangwyn, who looked so ascetic, could be so fastidious in every detail of his way of living. Everything about him seemed to have had the most careful thought lavished on it, though nothing in itself was of any great intrinsic value. Even the compactness of the cocktail cabinet had been forced to find room for three sets of glasses, amber, green and rose, to set off the complexions of the various kinds of drinks, and in its recesses he caught a glimpse of a pile of small black bowls, with silver bases, and wondered what manner of tipple was imbibed out of these.

'Getting a trifle warm, don't you think?' said Brangwyn.

Murchison had thought for some time past it was getting decidedly warm, what with the cocktails, fire and central heating. Brangwyn rose and opened a cupboard in the wall, inset among the books, and revealed an array of what looked like voluminous silk dressing-gowns ranged on hangers; he selected a dark crimson one, and then paused and eyed Murchison and selected another of peacock blue shading off to emerald.

'Like this?' he questioned. Murchison did not quite know what was expected of him, and returned a polite non-committal affirmative.

'Then shed your coat and collar and get into it,' said Bran 'The slippers are in the pocket.'

Murchison did as he was bid, shedding coat, waistcoat and collar after the example of his host, and girding himself about with the flowing silk, amazed to find the extraordinary change that came over his mood as the folds fell about him. In this garb he could have invoked the Great God Pan without any embarrassment.

'I always change my kit when I come indoors,' said Brangwyn. 'I find it helps me to think.'

'It's dashed nice stuff,' said Murchison. 'What does it smell of? It's got the same flavour as the cocktails.'

'Sandalwood,' said Brangwyn.

'But you don't put sandalwood in the cocktails?'

'No, essential oil of santal.'

'How do you get it to mix?'

'Smear it round the glass, and the spirit picks up the aromatic essence.'

They sank into a companionable silence after another round of cocktails, watching the fire change and glow and fall apart in caves of flame. The peat and the pinewood of which it was made smelling sweet and aromatic, blending harmoniously with the sandal-flavoured cocktail. Murchison had never realized before the way in which odour and flavour reinforce each other.

He found Brangwyn an extraordinarily interesting study, apart from the liking and respect he had always had for him. He had evidently brought the art of living up to the level of an applied science. Murchison approved with a sigh of envy. That, beyond all question, was the right way to live; but it needed cash, and plenty of it, for the development of its fine flower, and he, for his part, had had to bring the art of doing without to the level of a science.

'You like my little place?' Brangwyn broke the silence conversationally.

'I like it immensely,' said Murchison. 'But don't you find it rather noisy, what with kids playing in the street, and barrel-organs, and chuckings-out from the local pub? Especially in summer when the windows are open.'

'We never hear them,' said Brangwyn. 'I put sheets of good thick plate-glass inside the windows, and the ventilation comes down the old chimneys with the aid of electric fans.

'I suppose you wonder why I elect to live in a slum?' he continued. 'I am like Oscar Wilde; I can manage without necessities so long as I can have luxuries. I dropped a good deal of money through the War; rents are high in decent parts, so I picked up this bit of slum property cheap because it was too far gone to be worth reconditioning. I didn't attempt to recondition it. I gutted it. I left the front alone because if I had put in decent windows I should have only have had 'em broken twice a week and been assaulted every time I opened the front door. It isn't tactful to make yourself out to be better than your neighbours in this part of the world. They think I am going out disguised for a crime when they see me in my best togs, and entirely approve. If anyone comes around inquiring if I live here, the entire street swears I am non-existent without waiting to be asked. It suits me excellently.

'The chaps in the shops underneath are my tenants; in fact the lad in the bookshop is a manager, not a tenant, because book-collecting is one of my hobbies. The fellow in the Italian restaurant has to look after me as part of his rent. It works admirably. You should see him supervising the charwomen. I will give him a ring when we want supper, and he will come up the back stairs and produce it out of his hat.'

HETHER it was the drinks, or the smell of the sandalwood, or all this warmth and light after his drab existence, Murchison could not have said, but he felt his whole personality changing and unfolding and flowering as he lay back in the big chair sharing the tranquil silence. The warmth of the fire was lulling him to sleep, and as he drowsed with half-shut eyes it seemed to him as if the face of the bull of Babylon was superimposed upon that of his host, so that the two had become one; and the arm that lay along the padded arm of the big chair, its loose, crimson sleeve catching the fire-light, was the rose-red granite Arm of Power. Whether his dream would have led on to the coming of the Great God Pan himself, was mercifully concealed, for his host arose and phoned for a meal, and they adjourned to a small but beautifully equipped little dining-room, where a dark, lively Italian, the owner of the restaurant, served them with admirable food, openly adoring Brangwyn, and apparently quite accustomed to waiting on birds of paradise. Murchison had felt somewhat embarrassed at appearing before Brangwyn's domestic staff in his flowing robes, but Italians take that sort of thing in their stride.

The proprietor-waiter informed Brangwyn or the ingredients of every course; Murchison would have found this exasperating were it not for the light it threw upon his host as an epicure. Brangwyn evidently sensed his irritation, for he murmured in a low voice when the little man was momentarily absent from the room. 'One tips an hireling, but one appreciates an artist,' and Murchison got a yet further insight into his host's nature. The excitable little man, in his second-hand dress-suit, proprietor of a cheap eating-house in a slum, was to be treated as an artist because in his queer way he was an artist.

As Murchison had expected, the talk swung round to his own affairs when they returned to the lounge after dinner. He felt grateful to Brangwyn for his leisurely, Oriental style of diplomacy. It is so much easier to face a thing when one comes to it gradually. But, even so, he was almost rudely secretive in response to the leads his host gave him, because his need was so great, and he was so desperately anxious not to appear to cadge. Brangwyn could learn nothing of his affairs save that he made his home with his brother, had not got any special line of work, and was disengaged at the moment; he guessed the rest, and thought well of his one-time subaltern for leaving him to guess it.

But even the reticence of self-respect can be carried too far, and there were things Brangwyn greatly wished to know about his guest, though he was careful to hide his interest. The fellow might be suitable; and, again, he might not, and he did not wish to commit himself beyond the point where he could readily back out if the latter proved to be the case. But there are more ways of killing a cat than choking it with butter, and he thought that Murchison had had enough butter, and that it was time to cut the cackle and come to the bosses. He shot a sudden, authoritative question at him:

'What were you up to when I met you, calling upon Pan in front of the British Museum?'

Murchison jumped as if he had been stung, and his fair skin blushed painfully.

'Raising the devil, I suppose,' he muttered resentfully, greatly disliking his host's reference to the matter.

'Why did you wish to raise the devil?'

'Living with my brother, who's a clergyman, and his wife, who's a clergyman's wife, is apt to make you want to raise the devil if you can't raise the wind.'

Brangwyn saw that nothing was to be obtained by the direct method, so tried the indirect one, watching for reactions.

'It appeared to me, from what I know of the matter, and I have studied it a good deal, that you were well on the way to obtaining the presence of Pan when I interrupted you.'

Murchison did not answer, but Brangwyn fancied he pricked up his ears.

'Have you ever seen the invocation performed effectually?' he continued.

'No,' said Murchison uneasily.

'I have, and the results are very striking.'

'Does Pan appear in person?'

'How would you define Pan?'

'Ah, you have me there. I haven't any idea on the subject, save that he gave his name to panic.'

'Panic is what he produces in the unprepared, but in those who are prepared for his coming he produces a divine inebriation.'

'Oh, does he?' said Murchison sulkily, 'I prefer beer myself.'

Brangwyn saw that it was inadvisable to pursue the matter further, as the subject seemed a sore one. But as it was sore, he concluded that it was also vital, and ticked off the chief point in favour of the candidature of the unsuspecting Murchison for the matter he had in view. Murchison was reaching out well beyond the veil, whether he knew it or not, and whether he could be got to admit it or not, and as Brangwyn's interests lay exclusively beyond the veil, this was as it should be in a prospective employee.

He came to the point abruptly, 'Murchison, would you care to consider the offer of a post as secretary-chauffeur with myself. Live in and five pounds a week? It's only temporary, I am afraid, because I am liable to be called abroad at any time, and then the arrangement would have to come to an end, but I would help you to get fixed up with something else after you had finished with me.' That gave him a bolt-hole if Murchison did not come up to expectations.

Murchison's first reaction was a horrible suspicion that he was being offered charity, and the suspicion made him ungracious.

'What would the duties be?' he asked unemotionally, though his heart was fuming over inside him at this extraordinary piece of luck that had come his way after the long years in the wilderness.

'The duties,' said Brangwyn, a little puzzled by his manner, 'would be a certain amount of chauffeuring, as my eyes are not equal to long runs, but mainly odd jobs. Cope with correspondence; tackle tradesmen; keep an eye on Luigi and the chars, and stand between me and the world generally. I am engaged in some rather special work, and there are times when I can't be interrupted; and I want someone with the sense to handle things for me on his own initiative at those times.'

'My usual salary is three pounds a week and keep myself,' said Murchison sullenly. 'Why are you offering me a salary like that? It isn't my market price.'

'Because it is a position of trust and requires initiative,' said Brangwyn tactfully, 'and because the hours are irregular. I believe in paying enough to make the job worth while, and then I secure satisfactory service. Moreover, you will have to dress decently and generally keep up appearances, so it isn't all net profit.'

Murchison was mollified. He looked up with a sudden quick smile that completely changed his face. 'I'd like the job first-rate,' he said. 'I'll do my best for you, you know that.'

'Splendid!' said Brangwyn. 'You can fetch your belongings tomorrow. Meanwhile, I suggest we think about turning in. I hope you won't mind if I put you in my sister's room until I can get one fixed up for you.'

'Your sister's room?' demanded Murchison in sudden horror, all his dreams of a delightful bachelor menage falling about his ears.

'Yes, my sister keeps a couple of rooms as a pied à terre, but she doesn't use them much. I can fix you up quite comfortably upstairs. There's a whole lot of space I have never made any use of in this place.'

Brangwyn rose and led the way up a corkscrew wooden stair in the corner on to the gallery that ran round the room at half its height. He opened a door and entered a small room furnished as a sitting-room, passed through it into a bathroom, and then on into a bedroom, Murchison following him.

'A complete flat, you see,' he said, with a wave of his hand. 'all ready for occupation. We always keep the bed made in case she appears unexpectedly.'

'Is she likely to appear unexpectedly at the present moment,' asked Murchison anxiously.

'I trust not,' said his host negligently.

'What time is breakfast?' Murchison thought that he would not be sorry when the night was safely over.

'Tennish,' said Brangwyn, 'I am a night-worker, I am afraid. But if you ring through on the house-phone in the sitting room, Luigi will bring you rolls and coffee or tea and toast, any time you fancy. Then we have a decent breakfast between 10 and 1. Tea about three, and supper latish, when I've finished work. I find that a better way of breaking up the day than the usual arrangements, which spoils your morning sleep, sends you to bed when you are just beginning to wake up, and lays you dead in the afternoon.'

Murchison acquiesced readily enough. He would have acquiesced if his new employer had suggested cannibalism.

Good-nights having been said, Murchison strewed his clothes all over the room in the manner his sister-in-law had never been able to break him of, and then gathered them up hastily in case the redoubtable Miss Brangwyn returned unexpectedly. He wondered what sort of an old dame she would prove to be. Was she lean and cantankerous, or placid and whale-like? Would she keep an eye on his doings and report to her brother, or want to use him as a lounge lizard? She was the one fly in the ointment of what promised to be a perfect existence, and he found it hard to take her philosophically. Then he remembered his employer's words to the effect that the post was only temporary, and a sudden pang shot through him; he must be careful not to strike his roots too deeply lest the wrench of pulling them up should be too great.

He got into the heavy silk pyjamas that had been lent him, comparing them with the flannelette ones that were waiting in vain for him at Acton. He considered the bed, with its great square frilled pillow and deep rose-coloured eiderdown, but did not feel like sleep. It was by no means late, and he suspected that he had been pushed politely out of the way while his employer got on with whatever it was that occupied him o' nights. He wandered into the sitting-room to see if he could find a book. There were plenty of books here, just as there were downstairs. Miss Brangwyn was evidently a lady with catholic tastes in the literal, but by no means the theological, sense. Modern science and ancient philosophy jostled each other on her shelves, together with many modern novels and a very representative selection of the poets. Embarras de richesse here, thought Murchison, moving from shelf to shelf round the little room. He picked out a book at last. Jung on the Psychology of the Unconscious. What a book for an elderly female who ought to be knitting socks while she read missionary reports! He opened it and glanced at the fly-leaf, saw there a book-plate, looked more closely, and lo, his friend the Babylonian bull stared him in the face, wings neatly folded over his back, great bull-foot advanced, and on his plinth the name Ursula Brangwyn.

Murchison nearly dropped the book in his astonishment, not to say horror. He thrust it hastily back into its place on the shelf, got into bed, turned out the light, and put his head under the bedclothes.

It may have been this last act, or it may have been Brangwyn's cocktails that made him dream. For dream he did, and dreams of a quality he had never had before. He was a vivid dreamer, as are many men whose lives are shut in and inhibited; but his dreams were not particularly vivid that night. They reminded him of the times when he slept through his brother's services and the dronings mingled with his dreams. He thought he heard an organ being played in the distance, and the chanting of a mighty choir drawing near and dying away and drawing near again. He dreamt of the War, and searchlights playing up and down the sky, only they were coloured searchlights, of the colours of the robes he and Brangwyn had worn at dinner. All these things he seemed to be seeing and hearing between sleeping and waking, and they were vague and a long way off.

Then suddenly his dreams came to a focus and became crystal-clear and vividly bright, and he dreamt that at the foot of his bed a woman's head, bodiless, hung in mid-air, no larger than an orange, but vividly living, gazing at him intently. He sat up in bed in his dream and stared back at it open-mouthed, unable even to think. There was a curious likeness to Brangwyn about it. It might have been Brangwyn's daughter, if he had ever had a daughter. It neither spoke nor stirred, but it was alive, for the eyelids blinked from time to time. Then it slowly faded, and he woke up to find that he actually was sitting up in bed, but gazing into the blank emptiness of midnight.

He switched on the bedside stand-lamp and looked round the room. The door was shut and locked as he had left it; but even if it had not been, the vision could not possibly have been of a living woman because of the smallness of the head. He switched off the light and dropped back on to Miss Brangwyn's frilled pillow in disgust. He had dreamt of beautiful females before; they were no particular novelty, and he had read enough of popular psychology, which interested him, to know that night was compensating him for the denials of the day. He dropped off to sleep again, and slept dreamlessly till morning.

URCHISON awoke at his usual hour of seven o'clock, tubbed, dressed, and, as breakfast was a long way off, phoned for tea and toast. Luigi appeared in person, in a clean white jacket, and beamingly did the honours, evidently feeling that the responsibilities of hospitality rested upon his shoulders in the absence of his master. Murchison thought that the man who could win the adoration of a box of tricks like Luigi must be a good man to serve. Luigi had evidently been informed of his status in the house, and made a formal speech of welcome with many polite bows. Mistaire Brangwyn was a gentleman it was an honour and a pleasure to sairve. Mistaire—(a strange sound followed here, resembling the uncorking of ginger-beer) was fortunate, most honoured, most blessed, in being admitted to his service.

Murchison replied that he only hoped he would be able to achieve in his department the same lofty standard that Luigi had achieved in his.

Luigi bubbled with delight at this appreciation, and assured Mistaire—(more ginger-beer was uncorked) that he himself was also fortunate, honoured and blessed in having such a collaborator, and that his cooperation was always at his disposal.

Murchison replied that he thought that if they pulled together they ought to be able to make a good job of it. Luigi bowed himself out beaming, and Murchison saw how right Brangwyn had been when he said the tips would not buy the loyalty of a man like Luigi.

Murchison got rather bored hanging about waiting for the 10 o'clock breakfast. He did not like to wander about the house uninvited, nor to go out to get a paper, for he did not know how he would get in again in the absence of a latch-key. He felt that it would be more tactful to stop where he was till sent for, lest he drop unsuspected bricks, for he did not know the ways of the household, and had a suspicion that they were odd.

The air, though fresh, was over-warm for his taste, and he went over to where a diffused amber light came through some draperies and thrust them aside, concluding that here was the window, only to be checked by a sheet of plate-glass behind which was a filthy piece of Nottingham lace curtain and an even filthier sash-window. Peering through a rent in the Isabella coloured net, he saw the dreary facade across the way, and in a bow-window a foreign-looking female hunting small game in her infant daughter's hair. He looked down into the street, and saw a coster slowly shoving his barrow and apparently bawling, but no sound reached him through the thick plate-glass. Murchison dropped the amber silk curtain back into place again. It was certainly a mercy to have all the sights and sounds, and in summer presumably the smells, of that insalubrious neighbourhood shut out, but he wondered how he was going to like spending his days shut away from sunlight and fresh air in that somewhat high temperature, which he guessed to be in the neighbourhood of seventy.

He could not complain of stuffiness, however, and, looking up at the ceiling, he saw an ornamental metal grid, and judged from the slow movement of a curtain in its neighbourhood that air was being pumped into the room thereby, and presumably drawn out through another orifice which he could not identify. It was, he knew, the way most big buildings were ventilated, but, all the same, he found it hard to reconcile himself to it, and to convince himself he was not being stewed and stifled.

He shed his coat and prowled about in his shirt-sleeves, and felt better. The temperature would be all right if you had nothing much on, but in a thick suit and winter underwear it was decidedly oppressive. Then he shed a bit more, and yet more, until finally, hearing a step on the stair, he hastily seized the silken peacock robe that lay over a chair and flung it about him as a dressing-gown in case the visitor should be Miss Brangwyn.

But it was Brangwyn himself, in a robe of amber silk, and he smiled when he saw Murchison's peacock plumage.

'Ah,' he said, 'I see you have realized the value of the robes. All the same, that is not the right shade for the first thing in the morning. One is of the earth, earthy, at that time of day. And brogues, my dear fellow, do not go well with it. Let me beg of you to wear the appropriate slippers. So much more pleasant for both the feet and the carpets.'

Murchison, blushing and feeling a fool, did as he was bid, kicking off his thick, clumping brogues and pulling on the soft, heelless, glove-like kid slippers that matched the robe. Silently as two cats in a jungle they made their way down the corkscrew stairs to the dining-room and took their places at a table laid and decorated with every imaginable shade of amber, yellow and orange, gay as a sunrise.

Luigi did not appear, to Murchison's relief, who found that a little of the temperamental Italian went a long way, with his perpetual chatter of recipes. He himself was accustomed to shovel down whatever was set before him without paying any particular attention to it, which was just as well in his sister-in-law's menage, and spared him a good deal.

Everything was to hand, and they waited on themselves. The porridge, in a fireproof casserole, was ready made, but the bacon was artistically laid out in a shallow copper pan, waiting for the current to be switched on in the electric grill, and they ate their porridge to the accompaniment of its frisky spittings as it cooked, and the silver tinklings of the coffee as it trickled through the percolator.

'That porridge,' said Brangwyn, 'is ground between stones instead of steel rollers, and it comes fresh every week. Incidentally, I may mention, it takes all night to cook it. It is my belief that one should take thought in these small matters. Most people don't. They only take thought in big ones, and then it is usually too late. How much simpler to pay attention to your porridge instead of having your appendix out. Yet most people prefer the latter. I make a fine art of the simplest processes of living, thereby inducing a high degree of efficiency, and I hope to have your cooperation in the matter, Murchison, for I regard it as important.'

Murchison thought that the five pounds a week was going to be earned all right with all this finickiness, but acquiesced politely.

Brangwyn, who was watching him closely, continued, 'You know, my dear fellow, if you were designing a car you would study every detail of every part, right down to the air vacuum in its wake. How much more should one study the details of the machinery of living that make for smooth running and economy of power?'

'I had always thought you were a kind of monk,' said Murchison. 'I had expected to see you eating one of those nut rissoles that set solid inside you, instead of doing yourself jolly well, as you seem to.'

'Yes.' said Brangwyn thoughtfully, 'I always do myself as well as I can, except when I'm fasting. Why not? It has always appeared to me that only fools and slovens do otherwise. Yet what's this breakfast? Porridge, bacon, coffee, toast and butter, honey. But everything is the best of its kind, and I scoured the country till I found where the best was to be had. Most of it comes by post direct from the folk who produce it. It costs very little more than the worst of its kind. I don't suppose there is a shilling's difference between the actual cost of what is on this table and the cost of what you would get in a cheap boarding-house. The only difference is that everything has been thought out. Someone once asked Opie what it was he mixed his colours with to get such brilliant effects, and he said he mixed 'em with his brains. Luigi and I mix our recipes with our brains, and that makes all the difference. Now tell me, don't you feel, sitting there in your flowing robe, beside my yellow breakfast table, as if you were much more alive than you felt when you ate your breakfast yesterday?'

'My God, yes!' said Murchison, thinking of the leathery kidneys and tea that could have tanned them which he had partaken of twenty-four hours ago amid sounds of contention and smells of back-fired gas. There was a curious feeling of satisfaction to be derived from the simple perfection of this breakfast. The wheels of life moved smoothly and easily; his self-esteem seemed established on a firm basis. More things were soothed than the stomach by this minor artistry.

They were tranquilly digesting their breakfast with the aid of cigarettes which, in accordance with Brangwyn's theory that sophisticated smokes should be kept for later in the day, were homely papers, when host once again shot a sudden, revealing question at guest:

'What did you dream of last night?'

Murchison sat up as if a pin had been stuck into him. He hated these sudden questions that could not be parried because they could not be foreseen, and that laid bare the secret recesses of his soul; that forced him to speak of the things that should never be spoken of and exposed his secret self to ridicule. His first impulse was to deny that he had dreamed, or to make up an imaginary dream for his employer's delectation; but he knew that if his employer were a Freud fan, an imaginary dream would be just as revealing as the genuine article. He therefore determined to offer nothing but the truth, even if not the whole truth.

'I dreamt of a church service. Scraps, you know, nothing definite. Music, mainly. And of the searchlights we had during the War, only coloured, like our robes. Then I woke up for a bit, and then went to sleep again and didn't dream any more till I woke up for good at seven.'

Exceedingly innocuous, thought Murchison. Even the fiercest libido hound will find it hard to make anything of that.

'Anything else?' came the inexorable question. Murchison writhed and felt like rebellion, but five pounds a week is five pounds a week, and he answered sullenly:

'Oh, just the usual lovely houri.'

'Could you describe her?'

'Yes,' said Murchison furiously, looking ready for murder. 'She was damn like you. And now I suppose you'll say I've got a schoolgirl crush on you?'

'Not at all,' said Brangwyn placidly, quite unperturbed by the other's simmering resentment. 'There are a lot more things in the subconscious than are dreamed of by our mutual friend, Dr Freud. Forgive my eccentricities, but I am interested in some of the remoter branches of psychology, and one can learn a great deal about a person from their dreams, as you appear to know; and as we are going to work together, and I shall have to place a good deal of reliance on you, I am anxious to know what manner of man you are. I thank you for being frank with me, and I may tell you that I am quite satisfied.'

It was close on eleven before they concluded their leisurely breakfast, and Murchison thought of other meals he had gulped down and fled from. Life lived like this was as far apart from that which was led in his brother's home as the Eskimo from the Zulu. What it was to have money, he thought with a sigh. And then it occurred to him that it was not simply a matter of cash; it was the personality of the man opposite him that was the inspiring force; he would probably have lived in much the same manner, sitting on one packing-case and eating off another in an attic, and discriminating in the brand of his margarine.

Murchison doffed his robe, put on his clumping brogues, and set off to collect his belongings from his brother's house. It seemed like coming out not only into another world, but also into another century, when he stepped out of the front door that was black mahogany on one side and grained deal on the other. He felt rather as if he were a swimmer coming to the surface for a breath of air after the exoticisms of Brangwyn's flat. He made his way over the wholesome, mundane pavements in God's good air, and took the tube for Acton. He was still a little sore at having his houri dragged to the surface, and inclined to be resentful of his employer's easy superiority, though he had to admit that it was the superiority of man over man, and not of employer over employee.

It was nearly noon when he reached his brother's house, but he was met on the steps by a slattern with a bucket and swab, who shrieked to her mistress: 'E's come back, mum!'

The mistress of the house appeared, clad in a soiled afternoon dress that did duty instead of an overall, and, not being washable, was decidedly less sanitary. She had her hair in a bun behind, and a hair-net over her fringe, for being a clergyman's wife she felt it incumbent upon her not to follow the fashions. History teaches us that the good of all ages have always been against the fashions. When men's hair was worn long, the Puritans cut theirs short; and nowadays, when men's hair is worn short, reformers and intellectuals wear theirs long. And likewise with the females of the species. In Victoria's days they cut their hair short; but nowadays, valiantly declining to shingle, bob or bingle, they keep their buns as symbols of souls that rise above the things of this world.

It is curious also how seldom a religion of love sweetens the temper, and Mrs James Murchison was exceedingly acidulated in her greeting of her brother-in-law, rubbing his dignity in the char's filthy swab, as it were, while the slattern listened appreciatively.

'So you've come back at last? And did you get that post?'

Murchison thought how he would have smarted under that inquiry, with the char listening, if it were as his sister-in-law suspected it was. He had a shrewd suspicion that they had never expected him to get that post, knowing he had none of the qualifications that it had turned out to require.

'No,' he replied evenly, 'I did not get that one. In fact, the fellow was rather annoyed at my wasting his time over the interview, as he said he had made it quite clear that shorthand was essential. But I have got another, and much better job, with a fellow I knew during the War, and whom I met quite by chance, and I have come to fetch my things.'

'Fetch your things?' exclaimed his sister-in-law. 'Do you mean to say you are leaving us?'

'Yes,' said Murchison, 'I am glad to say I shall be able to take myself off your hands at last.'

It had been regularly rubbed into him that what he paid did not cover what he ate, and that they badly needed his room for their ever expanding family; but his sister-in-law appeared to have forgotten all that, and rapped out like a defrauded boarding-house keeper:

'You can't leave without notice like that. How do you expect us to manage without your money coming in?'

'Good God,' exclaimed Murchison, 'I always understood I was accepting charity!'

This nonplussed Mrs James for the moment, and made her feel she was not doing herself justice in front of the char, on whose appreciation she was counting, and Murchison did not improve matters by turning on his heel and marching upstairs to his room and slamming the door behind him. He did not trouble to pack formally, but flung all his small gear pell-mell into his old suitcase, chucked the bulkier stuff loose into a taxi, and was gone within ten minutes of entering the house.

He had fairly burnt his boats behind him, he thought to himself with a chuckle, as he sat among his piled-up belongings in the taxi. If he were out of a job again he would have to sleep on the Embankment, Acton would have none of him. But somehow he did not think it would come to that. He ought to be able to save a bit out of five pounds a week, and he did not think that Brangwyn would see him stranded if he served him faithfully. He had a strong inner feeling, that rose again as often as he tried to curb its exuberance, that his luck had turned. He felt as if he had been caught up in the current after swirling aimlessly in a stagnant backwater.

Arrived in Cosham Street, he knocked up Luigi in his restaurant, and begged for assistance in transporting his belongings up the long stairs to Brangwyn's flat. Luigi not only turned out in person, but summoned his entire staff of affable Latins, and Murchison headed a perfect army corps, moving in single file, their arms full of oddments. He inserted in the door at the top of the stairs the latch-key his employer had given him, and the beaming procession began to enter, when from one of the deep chairs by the fireplace someone arose, who had evidently been waiting there for his arrival, and he found himself confronted by a tall, slender, dark girl, very like Brangwyn. The very girl, in fact, whose head, no bigger than an orange, had appeared at the foot of his bed in his dream. He was so startled that he stood clutching his battered old suitcase, quite unable to take the hand she held out to him or respond to her greeting. If the bull of Babylon had walked off its pedestal he could not have been more taken aback.

She smiled at his confusion.

'I am Ursula Brangwyn,' she said, 'Alick's sister. Or, rather, his half sister. And you, I believe, are Mr. Murchison?'

Murchison recovered himself sufficiently to take and shake the hand she was still holding out to him and to admit his identity.

T was a merciful thing that Luigi and his myrmidons were queuing up and needed attention, for although the girl was the more self possessed of the two, as women usually are, it would have been obvious to a discerning observer that there was not much to choose between them in embarrassment.

'I had better show you your room,' she said, 'and then you can tell Luigi what to do with your things.'

She led the way up the corkscrew stairs, went along the gallery past her own apartments, and opened a door in the corner, which gave on a narrow and steep stair that had evidently been part of the original fabric of the house. At the top she opened another door, which was covered with brown baize as if to render it sound-proof, and stepped out on to a small landing lit by a glass door which gave access to a roof-garden.

'You have a little self-contained flat up here,' she said, smiling; and, looking round, he saw that open doors led into two small rooms, bedroom and sitting-room, and a third door, which was probably a bathroom.

The procession marched into the bedroom and shot everything on to the bed. Then it turned and marched down the stairs again, and they heard the door at the bottom shut after it. This did not tend to relieve the embarrassment of the two, who were thus left alone to entertain each other as best they might.

'I hope you have got everything you want,' said Miss Brangwyn, 'if not, you must ask,' falling back upon the conventional hostess's speech to prevent the formation of a silence which her companion seemed quite incapable of doing anything with.

Murchison mumbled an acquiescence, which he strove in vain to make sound decently civil, but his wits had forsaken him. All he could think of was the bull of Babylon and a girl's head no bigger than an orange that floated in the air at the foot of his bed.

Miss Brangwyn led the way out of the little sitting-room and paused on the landing.

'This is the roof-garden,' she said, opening the glass door, and he followed her out into the open air. They found themselves in an open court of some dimensions, for the roofs had been removed from all three houses, the attic walls being left standing to a height of some five feet. Leafless creepers upon the walls and leafless shrubs in tubs promised greenery in the summer, and a seat in an angle of the wall received the winter sun.

Ursula Brangwyn led the way to an embrasure in the wall and mounted a step.

'Look,' she said, pointing, and Murchison looked.

He saw, apparently quite near, the dome of St. Paul's, and in the foreground a huddle of roofs looking like the mountains of the moon. Human beings he could not see, for the near streets were too narrow. They two might have been alone in a dead world.

'The only way out here is through your flat, I am sorry to say,' said Miss Brangwyn, desperately making conversation. 'So we shall have to trespass, I am afraid.'

'Oh—Dr—yes,' said Murchison.

Ursula looked at him, and saw that his shyness was of such a painful intensity that she felt sorry for him, though oafishness was not usually a passport to her esteem.

'I am afraid I shall be the principal trespasser,' she said, smiling. 'And I am afraid I shall bring a gramophone with me, for I have to come out here to practise my dancing.'

'Er—yes,' said Murchison, thinking that if she wanted him for a partner he would fling himself from the parapet. She seemed to guess this, for her smile broadened, and she said:

'It is Greek dancing that I do.'

'Oh—Dr—do you?' said Murchison. 'That—Dr—must be very interesting.'

'Yes,' said Miss Brangwyn, 'it is very interesting.'

And then, mercifully, a deep-toned gong sounded in the depths below them, and she led the way down to lunch, Murchison feeling as if he could kick himself, for though he was not blessed with facile manners with women, he had never in his born days behaved like this before. He prayed that his employer would preside at the lunch table, but his prayer was not answered, and he and Miss Brangwyn settled down to a tête à tête. Miss Brangwyn heaved a slight sigh, and encouraged Luigi to chatter recipes.

With the discovery of the complete impossibility of Murchison, it seemed as if Miss Brangwyn's own constraint passed off, and she set herself to entertain him kindly and patiently.

Murchison realized quite clearly what was her attitude towards him, and it did not improve his state of mind. She had evidently decided that he was of weak mentality, but otherwise harmless. He would have given much to be able to inform her that she was entirely mistaken in her estimate of him; he was of perfectly normal mentality under normal circumstances, but far from harmless; in fact he would cheerfully have murdered her if he could have thought of any way of disposing of her body.

Silence fell between them after Luigi had served the coffee and disappeared; a silence which neither made any attempt to break, each having given the other up as a bad job; when a sudden exclamation from Murchison made the girl look up, startled, to find that he was staring fixedly at her breast.

'What is it? What is the matter?' she exclaimed involuntarily.

'I'm frightfully sorry,' said Murchison. 'I am afraid I am making a complete ass of myself, but the fact of the matter is I had a bit of a shock yesterday, and I'm not quite over it yet.'

'But what was it made you look at me like that?' demanded the girl, in her turn shaken out of her equanimity.

'Nothing. It was a mistake. I'm sorry.' He fixed his eyes on his plate. She raised her hand nervously to her breast. Was it possible that her clothes had fallen off her back? She could think of nothing else to account for his startled expression. Her garments proved to be intact; but as she fingered them she felt under her hand a small carved plaque of dark green jade that hung from a thin gold chain round her neck; a plaque that should have been safely bestowed out of sight under her frock, but which, in the exigencies of leaning forward to drink her soup, had slipped from the folds and escaped; and on this plaque was carved in bas-relief a winged bull of Babylon. Her fingers closed upon it convulsively.

'What do you know about my bull?' she demanded; and now there was nothing to choose between them in bewilderment and mental confusion.

'God only knows,' said Murchison, staring straight before him in acute misery. 'I don't know anything about it. I saw one like it at the British Museum yesterday. That is all!'

'That isn't all,' said Ursula Brangwyn in a low voice. 'You know more about it than that. I wish you would be frank with me.'

'There is nothing to be frank about,' said Murchison sulkily. 'I have told you all there is to tell. I saw a bull like that one on your locket yesterday at the British Museum. I have never seen one before, and I don't know a thing about it.'

The girl looked at him fixedly. 'I had a feeling when you saw me in the lounge that you recognized me, as if you had seen me before. Where was it you saw me? I have never seen you before to my knowledge, but I saw that you knew me.'

Murchison felt himself reddening.

'I wish you would be frank with me,' said the girl, 'you are making things very difficult for me. I don't know where I am, or what is expected of me. My brother simply sent for me. He gave no explanation. He simply said he wanted me to see that the spare rooms were got ready for a Mr. Murchison, who was stopping with him, and to look after him till he got back in the afternoon. And as soon as I saw you, I saw you knew me, and were surprised to see me here; and now I see you know my bull. I do not understand. I—I wish you would be frank with me,' she ended lamely.

Murchison saw that she was really startled and distressed, and her confusion restored his self-possession for the first time since he had set eyes on her.

'I don't understand things either,' he said slowly, squashing his cigarette-end in the saucer of his coffee cup. 'I'll tell you frankly all there is to tell, if it is any help to you. Yesterday I was at the end of my tether. Out of a job, and down on my luck, and all the rest of it. And I turned into the British Museum to kill an hour or two. And I suppose I was pretty wrought up, what with one thing and another. And I came face to face with one of those winged bulls that stand near the entrance to the Egyptian Gallery, and in the half-light—you remember how foggy it was yesterday—I thought the blessed thing was alive for a moment, and it gave me a turn. And I got into a queer mood, I don't know why, and I sort of rose up and cursed. Your brother heard me, and spoke to me. I was wandering about in the fog in the yard outside the Museum. And we found we knew each other. I had been under him during the War. And he offered me a job, for which I was truly thankful, for I was down and out, I don't mind telling you. And I suppose the whole thing upheaved me. You get upheaved when you're down and out. That's all there is to it. I don't understand it. It upheaved me beyond all reason. I am not usually the sort of idiot I am to-day.'

'I begin to understand a little,' said the girl, leaning her chin on her hand and staring at him thoughtfully. 'But you say you had never seen the bull before?'

'Never,' said Murchison. 'I was in an upheaved condition at the time, or I shouldn't have flown off the handle like I did.'

Ursula Brangwyn continued to stare, but made no comment. Finally she said, 'But you still haven't told me where it was you saw me before.'

Murchison felt himself getting as red as a turkey-cock under her scrutiny. He knew by the books on her shelves that she was a student of psychology, and felt she would put her own interpretation on his dream, and lied gamely:

'I have never seen you before.' She continued to fix him with her unblinking gaze.

'I am going to be very rude and say that I am not sure that I believe that,' she said, 'and I think it would be much simpler if we were frank with each other.'

'All right,' said Murchison. 'I don't mind, if you don't. Your brother put me to sleep in your room last night because the spare room wasn't ready; and I dreamt that a woman's head, no bigger than an orange, hung in the air at the foot of the bed. Of course, when I woke up there was nothing there, and I realized that it was a sort of female version of your brother, of whom I have always been very fond; and when I saw you I was struck by the likeness, that was all.' She must think what she pleased, if she were a Freud fan; he couldn't help it. But he was certain the scientific interpretation of that dream was pretty wide of the mark.

Ursula Brangwyn continued to stare at him fixedly without speaking. Then, to his surprise, she shut her eyes for a long moment, and then opened them and blinked like one awakening from sleep.

'Now I think I know why I have been sent for,' she said.

'I am afraid I don't,' said Murchison. 'Won't you be frank with me, as I have been with you? it was to be mutual, you know.'

She stirred the dregs of her coffee thoughtfully.

'You say you have never seen the bull before?' she said.

'Never,' said Murchison for the third time.

'Well, it is connected with an experiment my brother is doing, and that I am helping him with.'

'What sort of an experiment?'

'An experiment in psychology.'

'I am going to be just as rude as you were, Miss Brangwyn, and say that I don't believe your explanation any more than you believed mine.'

'I dare say you don't,' said the girl, 'though it is the truth as far as it goes. There is an old saying that it takes two to tell the truth, one to speak it and the other to hear it.'

'Well, I've been frank with you, and you've had a pretty good look at my immortal soul, which, believe me, it's no pleasure to me to wear on my sleeve.'

'Yes,' said the girl, 'I know you have, and I appreciate it. But it isn't easy to tell you the truth because you would probably misunderstand it if it were told you. Let me put it this way'—she looked up suddenly—'My brother thinks that there was a great deal more in the old pagan faiths than is generally realized, and he is investigating them from the psychological point of view. I have undertaken to help him'—her eyes avoided his, and a wave of colour flooded her face and neck, and even spread down her bare arms. Then she raised her eyes determinedly to his again, and looking him straight in the face, she said, 'I think he thinks you would be able to help him. And I think he sent for me so that I could see whether I would be able to work with you or not.'

'I have been engaged as secretary, Miss Brangwyn, and the engagement is only temporary, till your brother goes abroad.'

Miss Brangwyn stared into her coffee.

'My brother will not go abroad if the experiment is going on all right,' she said in a low voice.

Murchison saw in a flash the loophole that had been left for retreat if Miss Brangwyn had disapproved of him as a possible collaborator. He wondered why she had been embarrassed when he came up for inspection, and he guessed that the departure of her embarrassment had been due to the fact that she had made up her mind that he definitely would not do, and, therefore, she would not be called upon to work with him. But that since he had spoken openly she had revised her decision, and with the revision her embarrassment had returned.