RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"The Cheetah-Girl." Cover of Limited First Edition

THE collection of stories written by Edward Heron-Allen under the pseudonym "Chrisopher Blayre" The Purple Sapphire and Other Posthumous Papers (1921) lists "The Cheetah-Girl" in the table of contents but does not include it in the book. Instead we find only the note:

[The Publishers regret that they are unable to print this M.S.]

The story appeared separately in 1923 under the title: The Cheetah-Girl—Being the MS. not published with the collection under the title of "The Purple Sapphire.". In this edtion, Heron-Allen preceded the narrative with a "Note of Explanation" for the publishers' decision (qv).

The website of the Heron-Allen Society offers the following information about the work:

"Heron-Allen's recent literary reputation ... is based on the sale of a very slim volume, The Cheetah-Girl, at Sotheby's a couple of years ago. For the collector the book is almost too good to be true. Written under the pseudonym of Christopher Blayre, it is supposed to have been suppressed in the 1920s because it dealt with various sexual taboos. Only twenty copies were printed—just enough that one surfaces for sale every decade. The contents had been hinted at in reference books, but as very few had ever read the story then they would not have known that various forms of unconventional sexuality were dealt with, including prostitution, lesbianism, bestiality and pederasty."

— Roy Glashan, 25 April 2021.

THE note by my Publishers on page 211 [of The Purple Sapphire and Other Posthumous Papers] requires an explanation [of] which circumstances rendered it both difficult and desirable to offer in that place. The seven published MSS. were selected by me from among a large number of which I had become custodian, as explained in my Antescript to The Purple Sapphire and at the same time I brought away with me from the safe in the University library, for re-perusal, the MS. of The Cheetah-Girl. This MS., though setting forth the principles of an enquiry, and experiments, in a branch of Biological research the importance of which it would be impossible to overestimate, contains matters of record of such a nature that it could not possibly be published in a volume destined for public circulation. The table of contents was, however, compiled from the Title covers of the MSS. by my Secretary, who, I may mention parenthetically, made the mistake of writing "Deposited by the Professor of Biology" instead of "of Physiology"—there is no chair of general Biology in the University of Cosmopoli. This "table" went to the Printers after my departure from England on a protracted holiday, and was "set-up" with the rest of what is technically called "the preliminary matter." When, on my return, my Publishers asked for this MS. I considered that I was justified in showing it to them in confidence, and they at once agreed with me that it could not be printed. Hence the "Note" which Reviewers have regarded, some in the light of a joke (!), and some as a touch of intentional sensationalism.

Christopher Blayre.

I HAVE spent a long and very tiring day in London, and I have come home, worn out physically and mentally. But I have settled all my worldly affairs, and am, I think, prepared for any eventuality. I am now ready therefore to kill my wife on the first opportunity that offers.

I have written that deliberately; so as to see and to realise how terrible it looks, written down to "stiffen myself" so to speak, for, if it be possible, I admire my wife even more to-day than I did when we set out upon our wonderful honeymoon, just over three months ago. But, terrible as it is to contemplate, she must die as soon as possible; the welfare of the Race demands her death. There is bound to be an inquest, and I dread, even now, what the Post-mortem examination of her beautiful body may reveal. The manner of her death I have thought out and decided upon, and there is not, I believe, the slightest possibility of my being connected in the remotest degree with the tragedy, but I have deemed it expedient to make such arrangements as regards my affairs as may become necessary in the event of my being hung for murder. For I should not offer any defence or explanation of my act—I owe that to her, to her mother, to my predecessor in the chair of Physiology in the University, and to the memory of three months of the most passionate happiness which have ever fallen to the lot of man. And even if I did explain my action, would my explanation be believed? Perhaps it might, in the light of proofs I could bring forward, but would life be possible for me among human beings afterwards? A thousand times No. But I owe it to Science to record the circumstances which have led to the step I am henceforth seeking the opportunity to take. I shall deposit this record with the Registrar of the University, with precautions that it shall not be read until many years have elapsed after my death—I have no near relations, and I shall not marry again—therefore no one living can be hurt. And in any case the facts I have to record, whilst of paramount importance to Physiologists in the future, can never be given any wide publicity—if indeed they can be imparted to anyone at all, excepting under the seal of professional secrecy.

Thus much by way of introduction. My record must commence with the year 19—, when, having taken my degrees of Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Science, I was appointed Assistant and Demonstrator to Professor Paul Barrowdale, F.R.S., Professor of Physiology* in the University of Cosmopoli. With our academic duties I am not concerned now, and the records, so far as they could be published, of the research work done in the laboratory of that daring and brilliant Physiologist are to be found scattered among pages of the contemporary journals of Science. It is with our personal relations that I am constrained to deal. These became, almost from their inception, of the most intimate nature; in our work in the University, I recognised in him a brilliant master; he recognised in me a devoted and assiduous pupil; outside our professional connection our tastes, our views, were strangely identical. He was no narrow-minded or ascetic Scientist, and, away from the University, his appreciation of the pleasures of life, of "wine, woman and song," of travel, literature and art found a ready response in me, and we became confidential friends and companions, to a degree which is very rare between a Professor and his Assistant.

[* The print edition has "Psychology," which is presumably either a lapsus calami or a typographical error. —RG.]

There was only one subject upon which he never touched even in our moments of closest intimacy and confidence and in regard to which I never attempted to break the seal of silence which he had imposed upon himself, and tacitly upon me. This subject was Mrs. Clayton. As regards this lady, though the gossip which is indigenous to a University town no doubt from time to time formulated theories (for Barrowdale was a very free-living bachelor, was, as such, looked askant upon by many of the Professorial Staff and their wives) no one would ever "come out into the open," so to speak, for the all-sufficient reason that any scandal openly promulgated would have to be rapidly sterilised, should Barrowdale have shown any signs of wanting to marry any daughter of the University, and much will be tacitly ignored in a bachelor professor of more than ample private means.

Mrs. Clayton lived in a charming little house about three miles out of the town. It was understood that Barrowdale was her trustee and had charge of her business-affairs. There was a child, a girl, whom no one ever saw, but whether the child was born after Mrs. Clayton's arrival in the neighbourhood, or before that event, no one was in a position to say. One Academic lady (with daughters) had gone so far as to ascertain that the child, whose curious name was "Uniqua," was not registered at birth in the District Registry. Beyond this nothing was known; Barrowdale never afforded any intelligence, and if, as was whispered from time to time with bated breath,"à quatres yeux" she was his daughter, there was nothing on record to convey the slightest indication ora priori evidence of the fact.

I saw her once—I was walking with Barrowdale and we met Mrs. Clayton and the child, an ugly, sallow, swarthy little thing, who struck me as singularly repellent and uninteresting. Mrs. Clayton was a nervous, faded person, gentle in manner and appearance, but quite unnoticeable. She went nowhere and knew no one. Neither mother nor daughter interested me in the least. Now and then I believe an undergraduate would refer contemptuously to "old Barrowdale's woman," but there was no "talk," in the University sense of the word.

Several years passed by during which our work in the Laboratory and Schools, and our pleasures in companionship, grew more and more intimately connected, so much so that I refused the offer of a Professorship in a Northern University rather than be separated from Barrowdale—for the work we were engaged upon was of the highest Physiological importance. He was grateful to me for this, and I know that he never lost an opportunity of impressing upon the Authorities that I was his natural and indicated successor in the Chair of Physiology on his death or retirement. This came about one day with appalling suddenness. Barrowdale had been seedy, nervy "off colour," for several days. He had been out more than once to see Mrs. Clayton, as I knew, and one evening came home tired to death and drenched to the skin. The next day he was in a high fever, in the evening sceptic pneumonia of a most virulent type set in, and in twenty-four hours he was dead.

I found that he had made me, together with his solicitor, a worthy old man in London, his Executor and Trustee. He provided an annuity of £600 a year for Mrs. Clayton, which on her death devolved to Uniqua. The rest of his property, he being apparently alone in the world, was bequeathed to the University. The good woman, who seemed absolutely paralysed by the death of Barrowdale, came into Cosmopoli to see me whenever her affairs required an interview, always the same nervous uninteresting creature. I confess I hoped she would be led on some occasion to speak of Uniqua's father, but in spite of one or two "leads" she never "followed," and, being really quite uninterested in the matter, I never tried to press the subject.

In due course, almost mechanically, I succeeded Barrowdale in the chair of Physiology, and I had neither time nor inclination to concern myself about my two "cestuis que trustent."

We come then by effluxion of time to the end of last term. The men were due to go down for the Long Vacation next day, and I had made all arrangements for a protracted tour down the Loire and through the Midi of France. I may mention that Barrowdale left me by his will the comfortable and comforting legacy of £10,000. Some paper came to me on this memorable day from my co-trustee, connected with a change of investment, which required Mrs. Clayton's signature. There was no time to communicate by post, so I jumped into my two-seater and ran out to her house. I rang the bell and the door was opened by the most Beautiful Being that I had ever seen in my life—and I had seen a good many.

"Mrs. Clayton—?" I began.

"Mother is out," she replied, "you are Professor Magley? Please come in."

She held out her hand, which I took, and without letting go of mine, she drew me into their sitting-room, a cosy little place furnished with great taste (Barrowdale's taste) and strewn with fur rugs which gave off a warm sensuous perfume. The touch of the girl's hand was electrical, it sent a thrill of intense desire up my arm to my brain, and when she dropped my hand and stood before me, her lips parted in a smile more provoking than anything of the kind I had ever seen, I was simply struck dumb, and stood looking at her, my heart beating violently.

She was a lithe creature of rather more than average stature, draped, rather than dressed, in a kind of dull red silk wrapper, confined at the waist by a suede leather belt. It folded across her breasts (one of which, perfect in form, almost escaped from the folds) and came down to just below her knees—her legs were bare, and her feet were shod in fur-lined slippers. I verily believe that, save for this garment, she was naked. Her face was indescribable, a mass of purple-black hair gathered into a loose bunch on the top of her head, thick dark eyebrows shadowing long lazy eyes which seemed to me to be enormous, her complexion a tawny russet brown, with a suspicion of down on the cheeks and more than a suspicion of it at the corners of her upper lip. She had let her hands fall by her sides, and as she looked at me with that marvellous smile, the tip of a crimson tongue passed slowly across her lower lip from one side to the other. I was struck, even at that wonderful moment, by the comparative prominence of her little canine teeth, which gave an indescribable and characteristic charm to her smile.

Without saying a word, and, I declare, without any conscious volition of my own, I held out my arms, and she stepped forward into them. I crushed her body to me and our lips joined. I thought until then that I knew what it was to be kissed. I did not. The lingering passion of Uniqua's kiss was unlike anything I had ever dreamed of as possible. Her tongue which sought mine was strangely long and firm, and even in the delirium of the moment it seemed to me that her lingual papillae were accentuated almost to the point of roughness, but the exquisite power of it defies words. Her arms were round me, her legs were twisted into mine, and I think I should have fallen had she not gently disengaged herself and, still holding me by one arm she drew me towards a low divan covered with fine skins from which I had evidently aroused her. As she reached it she flung herself down upon the skins, and as she fell one beautifully modelled leg, bare to mid-thigh, escaped from the folds of her wrapper. She raised her arms to me in a gesture of divine invitation—and at that moment the door opened and Mrs. Clayton came in.

I do not know what was to be read from my face as I turned towards her, but if it was a reflection of Uniqua's, Mrs. Clayton must have been blind indeed if she did not take in the situation at a glance. I began, very haltingly, to utter apologies and to explain my visit. She was obviously very much upset and distressed, but all she said was—in short, disjointed sentences:—

"I see, I see. I could not have expected—no one comes here—I should not have gone out—I never do. Please bring the papers in here"—and she led me into the dining-room, where there were pens and so on.

All this time Uniqua had not moved or uttered a sound, but just lay curled up luxuriously on the divan, watching me with her huge eyes, and, as it were, "swaying" her beautiful smile from side to side—I cannot describe it otherwise. The slipper had fallen from the foot of the leg which still lay unconcernedly outside her "sarong," and here was the only movement that she made. The toes opened and shut and curled inwards towards the palm of her foot with a regulated movement which seemed to me to be indicative of extreme and perfect luxury.

Mrs. Clayton signed the papers, with a shaky hand it is true, but said nothing about Uniqua. The silence becoming oppressive, I thought it obvious and tactful to say:—

"Your daughter has grown into a very striking young woman."

"Yes—very," replied the poor woman nervously, "very. I never leave her if I can help it—but expecting no one, I went in next door for something—the servant is out—and so," she tailed off incoherently, and I saw that I was distressing her, so I took my leave as casually as I could, with my blood boiling in my veins and my heart throbbing.

When I got outside I took a deep breath, but I seemed saturated with the tense, sensuous perfume of Uniqua's room and of Uniqua herself, for, whether it was contact with her divan or what, her whole body gave off a perfume for which there was only one word—it was intoxicating—slightly savage. It clung to me all the way back to my rooms, and even afterwards when I had opened all the windows. I need hardly say that I could not get her out of my thoughts all day—nor did I want to—and I dreamed a dream!

Next morning, as I went on with my packing, and the College was rapidly emptying of the men off on Long Vacation, I said to myself:—

"Look here, my son, you are that girl's guardian. Barrowdale has entrusted her to you. It's a damned good thing that you are off to-morrow for three months—and when you get back again, keep clear of it"—Thus I apostrophized myself, and I knew that I wanted Uniqua more than anything else in the world.

By the afternoon the College was practically empty, and I had finished my packing, and was trying to read an abstruse German treatise on Cytology—but I couldn't. My senses were on edge—unnaturally keen—hypertrophied as it were. I heard a step in the Quad, it "slithered" up my stair—a rap on the door—I knew who it was before the door was flung open. In an instant we were in one another's arms. The long witchery of her kiss, the invitation of her magical tongue, everything was my dream come true. I had in my rooms a divan no less vivid with willing complicity than the one at the cottage; we fell upon it without a word, and in spite of the fact that Uniqua was in a physical condition in which it is customary for young women to withhold themselves from active caress, we gave ourselves up to one another, naturally, unthinkingly, in a whirlwind orgy of exquisite possession and ecstasy.

Presently, when we were able to talk—for until then not a word had been uttered on either side—I asked her how she had got away.

"Mother's had a sleepless night," she said, "and this afternoon she locked the front and back doors and went to bed. I got out of the window. I wanted you so frightfully."

An hour passed in a delirium of sensuous delight which cannot be hinted at—not from motives of reticence, for I am determined to record here the absolute facts as they occurred, without any periphrasis, but because the marvel that was Uniqua simply beggars and defies description. I thought I had known passion—fool! I had never even touched its fringe.

If Uniqua was wonderful to behold in her dull red sarong, what was she naked! No painter or sculptor ever imagined, much less reproduced, so perfect a body; her beautiful breasts stood out in perfect proportion, the nipples prominent and surrounded with a silky aureole of tiny purple curls, tender and fascinating. Her axillary hair was phenomenally thick and I speedily found that to be kissed and petted under her arms drove her frantic with delight. I have had reason to remember and be thankful for this, as will be seen later. The whole of her body was covered with the light soft down such as is seen upon many fair women, but upon Uniqua it was deeper in shade than usual, and it was punctuated here and there with little streaks, and sometimes almost circles of a still deeper tone. From her navel downwards it increased into a glorious mass of pubic hair which extended from hip to hip, and though so dense, was of the most amazingly soft texture, covering the whole of the lower stomach and intercrural space with a veritable "fourrure"—it was wonderful, and, to repeat the only adjective which describes any of Uniqua's esoteric attributes—intoxicating. Her forearms and legs were deliciously hirsute, and even up and down her spine a narrow furry band invited one's most ingenious caresses. Whoever gave her the name of Uniqua knew what he was about—prophetically.

We were lying in one another's arms, whispering passionate secrets to one another, I in a silk bath-robe, and she clad only in her wonderful skin and hair, when the door—which we had never thought of locking—was flung open, and Mrs. Clayton stood before us—frankly petrified and aghast.

I sprang to my feet and burst into words:

"Do not misjudge us," I cried, "we love one another as I never dreamed it possible to love. We shall be married at once—I will get a licence to-morrow, and next day Uniqua will be my wife. Forgive us the passion that has made us irresistible to one another—you will understand, I am sure—you are a woman who has loved, and you are her mother. Now you will have a devoted son as well as a daughter."

I paused. Mrs. Clayton had not said a word, she had fallen into a chair and, ashy-white, looked back and forth from me to Uniqua, who, utterly unconscious of her exquisite nakedness, lay on the divan, looking at us—with the same wonderful smile that had overwhelmed and held me, her crimson tongue passing to and fro across her lower lip. Then Mrs. Clayton got up— apparently with an effort—and she said:—

"No—no—no. It cannot, it can never be. You don't know. Oh! I am a wicked woman! At these times she is not responsible for what she does—and besides, she knows nothing. I never let her out of my sight until the time—the danger is over. Let me take her away!"

"But my dear lady," I said, "reflect a moment. We must be married now. We are both—I comparatively—young, and for a University Professor I am rich. I will be the best of husbands to her—the best of sons to you. Our old friend Barrowdale would have wished it, I am sure. I was his favourite—his only intimate friend."

At Barrowdale's name the poor woman started as if she had been stung.

"No, no, no," she cried again, "he would not—he would have killed himself and her rather. It has all been so sudden—I have not had time—forgive me for God's sake, and let me take her away."

"Well then, let us be engaged for a short while," I said ineptly.

"No, never. She must never marry. She can't. Oh, don't torture me!"

There was no reasoning with her. She was like a mad woman. Uniqua stood up in all her glorious statuesque nudity and allowed her mother to dress her with shaking hands whilst I looked on. I cut a poor figure. When she was dressed Mrs. Clayton took her away. She went without casting a look in my direction.

I was simply stunned.

I can give no description of the phantasmagoria of my thoughts for the rest of the afternoon and evening. One thing was certain: I could not leave England without having this matter cleared up and placed upon a proper, the only possible, basis. I thought and thought. What mad idea could the woman have? I tried to reason it out—I racked my brains for an explanation but found none. The girl was alive with passion, she was predestined to fall into the hands of some casual sensualist—what better solution, if her passion was in part, or in any way, pathological, than to give her to a husband who would look after her? I wearied myself with thoughts, and tumbled into bed at midnight.

At 3 a.m. I was awakened by a rapping at my door. I started into vivid wakefulness—It could only be Uniqua. It was. I subsequently learned that she had got past the Porter with a statement that her mother had sent her with a message of vital urgency—and with other inducement.

"I have got away again, sweet lover of mine," she said, as I took her in my arms. "Mother is mad, I think. Hide me—and take me away with you. Marry me or not, I don't care, I love you and want you so frightfully that I could kill anyone who stood between us."

What was I to do? I wanted her just as badly as she wanted me. She wanted to be loved—had, there and then—but I, with that practical good sense which I flatter myself distinguishes me, made coffee and toast and an omelette, and made her eat with me. Then we stole down and got past the heavily bribed Porter (remember Term was over, and he was once more a human being, and I no longer a Professor) reached the garage, carrying my bags which were already packed, got out the car and made a bee-line for London, where we put up at a quiet west-central hotel. Next day, I visited my co-trustee early, whilst Uniqua went shopping. She had of course come away wholly unprovided with any sort of trousseau. I confided the facts, in outline, to my co-trustee (who was horribly shocked!) got a Special Licence at Doctors' Commons, and in the shortest possible time we were married at a Registry and fled—yes, we absolutely fled—to Paris. From Paris we both wrote to Mrs. Clayton announcing the inevitable, irredeemable event, but we gave her no address, merely saying that we should be away for at least three months, and would send an address for her to write to and forgive us. 'The only person to whom I confided my whereabouts was the horrified lawyer.

I COULD, in normal circumstances, take a vivid pleasure in recalling and recording the amazement and delight of the most wonderful honeymoon that was ever granted to mortal man. Uniqua who, to my surprise, I found had never been further from her home than Cosmopoli, was delighted, not childishly, but wonderingly, with everything she saw. The beauty of nature, of art, of architecture, of antiquity filled her with deep happiness, which, oddly enough was merged with her in a deep sensual enjoyment of life. Keenly intelligent and interested in everything she saw, whenever she found herself in surroundings of exceptional beauty, a thrill of passion would come over her which rapidly communicated itself to me, and the wayside scenery of Le Vendée and the Bocage, the ruins of departed civilization, a hundred spots in Western and Southern France where we stopped the car to roam at will, come back to my mind as scenes beautified to memory by the most exquisite physical delights. The natural disturbance of her system in which we made our flight from Cosmopoli, seemed to ripen her physical and mental faculties to the highest point, but whenever this was past, she displayed a power of response to emotional stimuli which I sometimes almost feared would wear her out, but we were determined, "not to climb mountains until we reached them," and lived long days and marvellous nights, unimagined by the most poetic and fantastic dreamers of the East.

It was at Avignon one morning as she was lying in my arms, watching the sun rise through our open window, that she said with her lips on mine:—

"Rex—we are going to have a child."

It needed but that to complete our happiness, though from that moment the joy we had in one another became more reasonable, perhaps a little less passionate. I could always rouse her to an ecstasy of desire by caressing and playing with the wonderful masses of hair under her arms, and, her desire appeased, could always soothe her to sleep by the same means. But her passion for me, as a male, had to some extent given place in her to a fierce maternity. As soon as she knew that she was pregnant—she never had any doubt about it—she wrote announcing her news to her mother, and we anxiously awaited her reply, for we felt that this would put the finishing touch to her mother's forgiveness, and reconcile her to the marriage she had so strenuously opposed. A week passed by, and then I received a telegram from my co-trustee. It said:—

MRS. CLAYTON HAS DIED SUDDENLY UNDER DISTRESSING CIRCUMSTANCES. PLEASE RETURN AT ONCE.

I was horrified, and wondered how I should break the news to Uniqua. We were sitting in the Palace of the Caesars, quite alone that afternoon, and I thought it a good opportunity, I began:—

"Darling—I have had bad news to-day."

"Have we got to go back?—I shan't mind much, I've got my baby"—she always talked of it as if it were already born.

"No darling," I replied, "it's about your mother."

She looked at me quite gravely, and said:

"Is she dead?"

I could not help feeling a little shocked. She might have been asking if lunch was ready. I began:—

"You must not take it too much to heart. You have got me—"

"And I've got my baby, what does anything else matter? When do we go home?"

I was chilled, but in the circumstances it was better that she should take it like this, than that she should suffer paroxysms of grief. She accepted the situation quite calmly. When I told her she should now have £600 a year of her own, she said:—

"I shall not have to spend any of it, shall I? You are quite rich. I shall save it all for my baby." She never said "our baby".

Then she said: "Do you think Professor Barrowdale was my father?"

This was a blow between the eyes, and I said rather lamely:—

"Well, I have often wondered about it myself, but he never told me anything about it. Did your mother never say anything about your father?" I was curious that we had never touched upon this subject before.

"No," she answered. "I never asked her but once, and then she seemed dreadfully upset, and said I must never speak to her about my father. She could not bear to think about it." After a pause she added, "I don't think Professor Barrowdale was my father—I never felt like it, and I don't think I should have, if—. He seemed more interested in me, and how I got on with lessons and things, and how I was growing up, than really fond of me. Sometimes I fancied that he disliked me—that I 'repugged' him," (one of her words), "but anyhow he must have been an awfully good man. See how he looked after us."

"He was a good man," I answered stoutly, "no one ever knew what a lot of fine things he did. Especially for women—the sort of women you have never heard of, women who had come to grief, and were down and out."

"Do you mean prostitutes?"

I was ceasing to be amazed at my wife's sudden remarks, which from time to time showed an esoteric knowledge of the world, gathered I am at a loss to know how or whence.

"Well," I said, "that is about it."

"I don't wonder he was so good to them. It seems awful for men to be so down upon girls who are what I should have been—and proud of it—if you hadn't married me. After all, they are responsible, aren't they?"

"Perhaps."

"And yet I don't know. I wanted you so frightfully the moment I saw you, that you could not have helped having me. No one can say you seduced me!"

And thereupon this amazing girl turned to other subjects as if this had been an ordinary dinner-party conversation. But I never loved her more than I did then, or, for that matter, more than I do now. In truth I could reply when, as she often did, she asked me, "How much do you love me, Rex?"

"A little more than I did yesterday, but not so much as I shall to-morrow."

And then by a three days' journey, for I was anxious in the circumstances that she should travel easily, we came back to London, and the world crashed into ruins around me, and the light went out of my life for ever. Ich habe geliebt und gelebt.

WE arrived one evening of the late summer, and put up at the same hotel as that which sheltered us when we fled from Cosmopoli, and next morning I called upon my co-trustee, who received me with grave and forbidding formality. It was clear from his manner that he regarded me as a perverter of youth, and incidentally as a murderer. I tried to open the conversation upon conventional lines.

"This is a most unfortunate circumstance," I began.

He interrupted me. "It is more than unfortunate, it is deeply tragic."

"You mean?"

"Professor Magley," he replied, "it is not my duty, nor have I the inclination, to sit in judgement upon your actions, or even to express an opinion, though, of course, I hold an opinion which I should be loath to express. I will confine myself to the facts. When you—eloped is, I believe, the technical expression—with Mrs. Clayton's daughter, she came up to town and saw me. She was quite dazed—stunned—by what she termed the catastrophe. I will admit that she seemed to regard your action with a horror which, bad as it was, appeared to me exaggerated, seeing that you had repaired your fault, as far as it could be repaired, by rapid marriage. She bitterly blames herself for having so far relaxed her vigilance as to make the meeting between yourself and our ward possible, but the extraordinary, if I may say so, the indecent rapidity with which these events took place made it impossible for her to 'do her duty' as she expressed it. What may have been that duty, and what the views entertained by herself, and by the late Professor Barrowdaie as to her daughter's future may be, I cannot conjecture, nor did she enlighten me, but I gathered that she had solemnly sworn to prevent her daughter's marriage if it were possible, by the revelation of certain facts known only to herself and the late Professor. Of what these may have been I have no idea, but I gather that they are contained in a written statement which it becomes my duty to deliver to you. I saw her no more after this interview, but I went down to Cosmopoli to see after her affairs and to attend the inquest."

"The inquest!"

"Yes—you have not seen the papers this morning?"

"No—I arrived last night, and came straight here this morning."

"It took place yesterday, and her remains were buried in the Parish Churchyard yesterday afternoon. It was her wish that neither you nor her daughter should see her again—she was right—it was no sight for a young woman who expects to become a mother."

"Then you know?"

"Yes. One moment. I learned from her servant that on receipt of a letter from our ward in which she announced her condition Mrs. Clayton spent two days without moving from her chair, refusing to eat, or to see such neighbours as she had admitted to a slight acquaintance. On the morning of the third day the servant entering the sitting-room which this unhappy lady had not left, found her lying upon the divan which was soaked in her blood. She had cut her throat—inexpertly—with a common penknife; she must have bled slowly to death, the windpipe was not severed, and the jugular vein only just sufficiently wounded to allow the blood to escape—comparatively slowly. She had left a letter for me which you had better read."

He handed me a sheet of paper scrawled over with incoherent sentences. It said:—

I cannot face it, I am a coward—I knew I should be when the time came. I ought to have—but I had no chance. I am going to kill myself. I cannot face Uniqua, she must never know, I promised Paul B. that when a man wanted to marry her I would give him the papers. I had no time—if I had had time I know I could not. Mr. Magley must see them, no one else, not even you. You have them, the packet I gave you when Paul B. died. He will understand. What he will do—I forgive him, it wasn't his fault, it was my fault, he will understand when he reads. God help him—and her. It must not be.

Ursula Clayton.

"What does it mean?" I asked in a voice which I hardly recognized as my own.

"I do not know. But, Professor Magley, I own that I am terrified, and that I am deeply sorry for you. Paul Barrowdale was a strange man. There were episodes in his earlier life that no one knew about—and what I could guess from collateral evidence and an occasional hint which he dropped, appalled me, hardened as I am by a long professional career to the wilder aberrations of the human mind. Not that Paul Barrowdale was mentally affected—no one was ever more sane, but—he indulged what seemed to me to be terrible and morbid curiosities. Though my views as to your conduct remain unaltered, believe me, I am deeply sorry for you, for I fear that the punishment of your crime—I put it as high as that—may be almost more than any human being should be called upon to bear. Mind! I know nothing, I can only guess, and my brain reels when I allow myself to wander into conjecture. I will now give you the packet of papers to which Mrs. Clayton refers in her letter. I had some difficulty in keeping them from the Coroner on the grounds of professional confidence, and that the papers were not hers but Barrowdale's, and consequently the property of yourself and me as his Executors."

And with that the lawyer handed me a large square envelope sealed at every flap with Paul Barrowdales private seal.

"If I may add a word of advice," continued he, "I would earnestly beg you not to open this envelope until you and your wife are settled in whatever house you have provided, or will provide, for her. Until that is done you will require all your presence and concentration of mind. I will not hide from you the fact that these incidents are likely to have a significant influence upon your career and position in the University."

My mouth was dry as a morphinomaniac's—I felt deathly cold to the tips of my fingers and toes. I felt that my world was collapsing and that I was being buried in the wreck and ruin of forces of which I was utterly ignorant.

I hardly know how I got back to Uniqua. Fortunately she was quite calm, and showed no curiosity as to my co-trustee. A few days passed during which I went down to Cosmopoli and took a small furnished house in the town, and instinctively I engaged the girl who had been in Mrs. Clayton's service to come and attend to us. Whether it was an effect of the nervous tension in which I was living, the sense of impending horror—conscience if you will—I do not know, but it seemed to me as if the few acquaintances whom I met looked curiously, and askant upon me, avoided me rather. My one object now was to get settled, and to know the worst.

I brought Uniqua down to Cosmopoli, where she took to her new abode like a cat to a new and comfortable basket. She never mentioned her mother—my precautionary warning to the servant not to go into details with the ineradicable gusto of her class was unnecessary. Uniqua did not go out at all, she lay most of the day on the divan which I had installed in conformity with what I knew to be her inclination, and did not appear to notice that in these days passion was utterly dead within me. At night she curled up by my side with her arms and legs wound round me as if I had been a sister to her, and slept peacefully whilst I lay awake listening to the University clocks and praying for daylight.

I put off the opening of Paul Barrowdalc's envelope from day to day—I was afraid! I told myself that I must get my nerves into stable condition before I undertook the perusal of—what?

THE time came however when I pulled myself together and determined to solve the mystery, and one evening—it was about a month ago—when Uniqua had gone to bed I broke the seals. I read. And all the time—continuously it seemed to me, the University clocks cut off and flung into the rag-bag of the past, section after section of my life.

THIS must be written. Some day a man may want to marry Uniqua, and he must know. I am sorry for him, whoever he may be, but he must know. With an introduction setting forth the physiological researches which have led to the terrible position of affairs here recorded, I will set down the facts in narrative form.

The study of the physiological phenomena of gestation and reproduction, and the evolution of genera and species has occupied my mind almost exclusively during the whole of my career. Closely connected with this question are the remarkable experiments (and their results) upon the artificial fertilization of parthenogenetic—or to use Lankester's preferable "impaternate"—eggs, carried out by Jacques Loeb, Bataillon, Deslages, and others. The outcome of their researches has seemed to prove incontestably that the function of the male spermatozoön in the fertilization of the female ovum is, in the first place, purely mechanical. They have fertilized and brought up to a pronounced stage of development the larvae, and even to relative maturity, parthenogenetic (impaternate) eggs of Echinoderms and Batrachians, by means of artificial stimuli, such as hypertonic solutions, pricking with a fine needle, brushing with camel-hair brushes, to cite in a generalized form only a few of the methods employed in the laboratories of Science. Those who would know more of this are referred to the many papers published on the subject in scientific journals, and of late in the text-books. We start therefore from the conclusion that the action of the spermatozoön is primarily mechanical; it merely perforates and excites the ovum, and "sets it going," so to speak, and may therefore be replaced by artificial and mechanical means.

This being so, we may turn to the theory which deeply occupied the mind of Alphonse Milne-Edwards during the later years of his life. The question arises, why should there be any limits to the possibility of miscegenation? We know that, within a genus, allied species can breed together, as for example a horse with a donkey, a tiger with a jaguar, a fox with a dog—instances might be largely multiplied. But genera cannot breed with genera, as for example a dog with a cat, a horse with a hyena, or an elephant with a rhinoceros—to carry it to the highest point, a man with a mare, a woman with a dog. Why not? If the action of the male spermatozoön is mainly mechanical, why not? This was the problem which occupied the mind of Milne-Edwards and he discussed it with Ray Lankester shortly before his death, and Lankester has recorded his impressions of the discussion in one of his later volumes of collected scientific essays. I will transcribe here his account of the matter. He says:—

"He (Milne-Edwards) held it to be probable, as many physiologists would agree, that the fertilization of the egg of one species by the sperm of another, even a remotely related one, is ultimately prevented by a chemical incompatibility—chemical in the sense that the highly complex molecular constitution of such bodies as the anti-toxins and serums with which physiologists are beginning to deal is 'chemical'—and that all the other and secondary obstacles to fertilization can be overcome or evaded in the course of experiment. He proposed to inject one species with 'serums' extracted from the other, in such a way as seemed most likely to bring the chemical state of their reproductive elements into harmony, that is to say, into a condition in which they should not be actively antagonistic but admit of fusion and union. He proposed, by the exchange of living and highly organised fluids (by means of injection or transfusion) between and male and a female of separate species, to assimilate the chemical constitution of one to that of the other, and thus probably so to affect their reproductive elements that the one tolerate and fertilize the other."

In this case, observe that the influence of the male spermatozoön would be more than merely mechanical, the male would transmit his physical characteristics to the zygote—the embryothus called into existence. When the Sea-urchin's (Echinus) eggs to which I have referred above, are pierced (as is done in laboratory experiments), by the sperm filaments of Feather-star (Comatula) introduced for the purpose in another series of experiments, the sperm filaments pierce the egg-coat but contribute no substance to the embryo into which the egg develops. They merely "stimulate" it and set changes going. But if physiological technique could be perfected to such a point as to harmonize the fluids of the Feather-star with those of the Sea-urchin we should, or might, get a hybrid between Comatula and Echinus.

To adumbrate is at once an ultimate result to be aimed at. How often we find a splendid young woman married to a physically perfect young man, keenly anxious to have babies and carrying out to the full their privileges towards that end—but they remain childless. It is clear that their serums are toxic to one another. The man has a passing affair with a servant-girl or shop-assistant, and she immediately has a baby; the woman gives herself sporadically to a lover and immediately conceives: they have found their natural "affinity." There is in my opinion a great future in store for the bold surgeon or physiologist who will rectify matters in these "sterile" marriages, by bringing the husband and wife into a condition of mutual equilibrium by injection, inoculation or transfusion as suggested by Milne-Edwards.

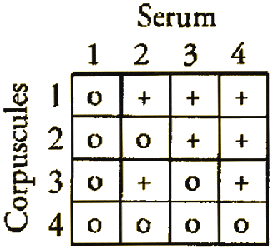

How is this to be done, and how are the facts to be established? The answer comes to us from the Physiologist's Laboratory, and from the clinic. How often one reads in the newspapers, and even in novels, of devoted friends who have offered themselves, when a comrade is suffering from severe haemorrhage (and in other circumstances), for transfusion of blood. Sometimes we are told that in spite of the heroism of the friend, the patient has died—in nine cases out of ten it is, or was, because of that heroic gift of the friend; the patient has been killed, as surely as if the operating surgeon had blown out his brains. The War-hospitals of 1914-18 afforded us, first examples, then experiments, and at last lessons, which, once learned, have abolished the grave danger attending transfusion of blood from one human being to another. It has been established that in this matter the human subject is divided into four classes, between which phenomena are varied. If a drop of blood from the donor and recipient are mixed upon a microscope slide, the corpuscles either swim about freely together in the mixed serum—in which case the operation may be safely performed—or, haemolysis (agglutination) takes place. The corpuscles "clot" together, and we know that, if the operation is proceeded with, the recipient will be almost immediately killed. Before the dawn of this knowledge, how many patients may have fallen victims to the "heroism" of a toxic friend? To make this matter clearer, if you are not already familiar with it, I will reproduce here the diagram from Back and Edward's Textbook of Surgery (p. 79):—

In the case marked "+" agglutination takes place. In the cases marked "o" no agglutination takes place. Thus it will be seen that the blood of group 4 may safely be given to any recipient—they are the "universal donors." The serum of group 1 does not agglutinate when mixed with that of any of the others—they are the "universal recipients." But give the blood (say) of group 3 to a patient of group 2 and you will kill the patient.

In the case of the sterile marriages a simple blood test of this kind will establish the facts upon which the surgeon may safely proceed.

You will wonder—whoever you are, who is destined to read this manuscript—why I have delayed my narrative by this long scientific introduction. It is in the nature of an "apologia" in the classical sense of the word, for what follows.

As a young man, and beyond that time, I made many experiments to prove the truth of this theory—many of which were entirely successful. I produced hybrids between widely separated genera, which often shocked even myself. I did not dare to publish my researches to the world, the time was not ripe—the scientific outlook was not yet sufficiently broad. Negligent as I was, almost to the point of fearlessness, of public opinion, I shrank from the howls of ignorant rage which would have greeted the publication of my results. The anti-vivisection mania was at its height. Foul libels upon the earnest workers at physiological research found ready publication in the Press, and it was tacitly understood among physiologists that our experiments must for the most part be kept to ourselves. University authorities looked ever with an anxious eye upon the biological laboratories, ever anticipating the eruption of some sensational scandal or subversive theory, which would rouse a storm of ill-informed invective against the scientific teaching of the Universities. But in my private laboratory—which became a veritable zoological garden—I never relaxed my efforts.

You will not be surprised—even though you be shocked—at what I am going to say next. I looked forward, as the crowning experiment of my career, to the production of a hybrid between one of the higher forms of the Animal world—and Man. You must realise my position. The sexual union of human beings and animals is, no doubt properly, shuddered at, as perhaps the foulest form of unnatural crime. It figures in our books of jurisprudence under the name of "Bestiality," a felony punishable until comparatively recent years with death, and actually with penal servitude for life. How could a man in my position put himself into the power of a man who would lend himself to so "filthy" an experiment? The widely varying forms of Sodomy were looked upon as "aberrations," but were none the less punished by long terms of imprisonment, but Bestiality was regarded as an even lower and more revolting form of vice. The accomplice would necessarily be of the lowest order of criminal, and one would have laid himself open to everlasting blackmail. The suggestion is obvious that I might have been an active participator in the "experiment." I will only say that my whole soul revolted from the idea with shuddering disgust, and I should—to put it on no higher grounds—have been physically impotent in approaching the subject from a personal point of view. I read the horrible treatise on the subject of Dubois-Dessaules published in 1705, and my gorge rose at the long catalogue of horrors he had resuscitated from the Morgue of forgotten criminal records.

Bestiality, as a crime, dates from the highest antiquity. In the more outspoken early editions of our Bible it is indicated, haud incerta voce, as rife among the Jews both male and female, and the references to it in Exodus and Leviticus are explicit.*

[* 1 Exodus, XXII. 19. Leviticus XVIII. 24 and XX. 15, 16. ]

In Mythology it appears as a common ruse among Gods, who appear to have found it easier to seduce the daughters of men metamorphosed as animals, than clothed in their normal and god-like attributes; the legends of Phoebus and the Lesbian Issa, of Pasiphaë, of Leda, of Io, are prominent examples among the Metamorphoses of Ovid. In the Middle Ages the Devil is constantly taking the form of a goat for the purposes of sexual connexion with reputed Witches. The work of Boguet upon the Sorcerers (1607) teems with examples, and gives categoric instances of women who have been fecundated by dogs, whilst the laborious compilation of Dubois-Dessaules runs to 450 pages of revolting record. The works of Voltaire bristle with instances on record of the resultant birth of the monsters. In India, sculptures on the Temples of Shiva, especially at Orissa, represent continually the sexual conjugation of women with apes, dogs and other animals.

The Criminal Codes of Prussia, Germany and the United States recognise the crime, that of Pope John XIII provided for its "accommodation" but a fine of 250 livres. The historians Aelian and Athenaeus cite numerous instances as a mere matter of record, and as lately as 1882 Lacassagne has produced a work La Criminalité chez les Animaux. As active or passive agents, human beings form a long procession down the records of Jurisprudence, and the work upon the subject of Tardieu is well-known to Pathologists, Alienists and Jurists, As a rule the crime was included under the general heading of "Sodomy," but the earlier jurists drew a sharp distinction, e.g. A. de Liguori who gives the definition "Sodomia, i.e. cum persona ejusdem sexus; et Bestialitas, i.e. concubitus cum bestia."

Bestiality as a deliberate inclination is classed by Krafft-Ebing with Sadism, Flagellation, Exhibitionism, Necrophily, and Homosexuality under the general heading of Paresthesia, and the scientific attitude towards these aberrations may be summed up as follows:—

Too many different factors concur to produce races for it to be possible to unify, to codify, human morality. Heredity, climate, education, social conditions, riches or poverty, each of these contributes a different factor. The Human Creature is not always master of his functions, his existence depends upon inimical or allied factors against which it is sometimes impossible for him to react. Therefore, in the face of the worst turpitudes of human nature, known to us as crime or vice, the Scientist does not protest, he merely seeks for the causes and tabulates the effects.

Undoubtedly the dominating factor is heredity, and Tardieu goes even further than this in ascribing such aberrations to atavism, and we find the records of such factors in every corpus of legend and tradition from the Golden Ass of Apuleius down to the bestialities of the Arabian Nights; from the references of Nicolas de Venette to those of Montaigne, and of Balzac, of Armand Charpentier and others. Among savage races we have the amazing records of Paul du Chaillu dating from comparatively modern times. With loathsome "romances" of de Musset (Gamiani), Bishops and of other Pornographers we have not to concern ourselves. This rapid historic review has seemed to be necessary as an indication of the lines along which this horrible subject may be pursued and studied, should it be required to do so.

There have been many cases recorded of Bestiality in which women have been the passive human participants—they in fact constitute the majority of recorded instances, obviously by reason of the fact that, in such cases, the reasoning human participant is not called upon for action. These are no less horrifying than the others, but it was clear that to find such a woman one would have to ply a muck-rake among the ranks of the lowest, most abandoned, and depraved members of the prostitute class—one had heard of such things in the brothels of Paris, Berlin and Naples. I shrank from the bare idea of encountering such creatures. I had experimented successfully in artificial fecundation with the lower animals—but when I considered the possibility of carrying this higher, I found myself confronted with the same insuperable feeling of horror and repulsion. But none the less, theoretically, the thing became an idée fixe in my mind—an ultima ratio probably never destined to get beyond the theoretical stage.

This brings me down to a moment—now fourteen years ago—which, in the success of achievement, has cast a shadow over the whole of my remaining life.

I HAD read so far in Barrowdale's manuscript, and at this point I sprang to my feet, overcome with a hideous nausea; I felt that I was fainting from sheer terror and apprehension. What was I going to read? I put down the MS., took a stiff dose of brandy and walked out into the night air, to think, to recover my senses, to overcome the horror that was gripping me. I had almost determined to read no further, when a fearful thought crossed my mind. It will probably have crossed the readers. I tried to put it from me in vain—it simply tortured me physically—but I knew I must read on. After an hour I returned home. I crept up to our bedroom. Uniqua was sleeping peacefully, her delicious smile just parting her perfect lips. I reassured myself for a moment, and then fell back again into my previous mood of terror and consternation. Whatever I was to read, I had brought it upon myself, and I went back to the damned MS.

I USED to get the animals which served me for my research work down at the Docks—from the successors of the renowned Jamrach. They thought, and I did not undeceive them, that I was an agent of the Zoological Society. One day I visited my purveyor in answer to a note informing me that he had a remarkable splendid specimen of Felis jubata, the Indian Hunting Leopard or Cheetah, an animal I had long desired to possess, on account of its curious capacity for being domesticated and kept as a pet. It was a most beautiful beast, a male about a year old which had been bred in captivity, and was already as docile and as responsive to caress as any ordinary cat. I bought him and made arrangements for his transfer to my house in the country where I kept my creatures. The few colleagues who were admitted to a knowledge of my experiments called it my "Island of Dr. Moreau"—from the late H.G. Wells's dreadful book of that title. Not, however, that my work had anything even remotely in common with the horrors suggested in that remarkable work. By the use of general and local anaesthetics my animals were never alarmed, or indeed conscious that they were what the Anti-Vivisectionists would have called "Martyrs to Science"—they were a very happy family, and, in point of fact, when they had spent their allotted time with me and had bred the desired hybrid, or failed to do so, in ease and comfort, I transferred them to Regents Park. No animal ever died under my care or treatment, except from pneumonia or some other disease incidental to our climate, or to the artificial conditions of its existence.

I was returning late in the afternoon up Ratcliffe Highway, speculating upon the motley crowd of seafaring folk of all nations that throng that historic thoroughfare, and the degraded types of harlot who ply their wretched trade among them, when one of these, giving my arm a gentle nip as she passed me, said, in a half-whisper:—

"D'you want a naughty girl?"

I looked at her as I shrugged her off. She was a finely-made, bold-looking strumpet, younger in years and it seemed to me of a higher racial type than the generality of the local consorority. Very fair, neatly though shabbily dressed, with large wistful grey eyes, and teeth that were both clean and regular. Her appearance surprised me. My short scrutiny encouraged her and she said rapidly:

"I'm the naughtiest girl in the Highway, and I like old gentlemen. I'll do anything, show you anything you like. Don't you want to come with me? I'll astonish you."

"Go to the devil," I said brutally, "or I'll give you in charge."

"All right, Governor," she replied. "I'm going. Au revoir, mon ami," and before I could recover from my surprise at her accent, which was perfect, she flung herself on the rails in front of a rapidly approaching tram-car.

Deeply shocked, and responding to an irresistible instinct, I flung myself after her, caught her by one ankle, and jerked her free of the lines. The driver had applied his brakes, but the front wheels crushed her hat. It was the nearest thing possible. I hauled her on to the pavement and immediately a dense crowd of loafers, seafarers and street-walkers collected round us. She had fainted.

"Give us a little room," I said, "I am a doctor. Does anybody know anything about her?"

"Know anything?" ejaculated a sailor, "yes we all know all there is to know, and that's too much—the dirty bitch."

"Oh lor!" chimed in a loathsome and pustular female who had forced her way to the centre of the crowd, "the gent's in luck, ain't he? He's got Menagerie Sal!"

"Whatever she is," I replied hotly, "she can't he left here. Where does she live?"

"Anywhere you like to take her," said another Brute. "Here, get up Sal!" and he kicked her in the side.

I sprang up and would have collared the beast but, perhaps fortunately, the invariable and imperturbable policeman appeared among us, and the crowd fell back.

"Who—what is she?" I asked the man in blue.

"One of the worst, sir, about the worst I reckon." The woman was coming round. "Here, get up Sal," continued the constable, "and go home, if you've got one—or I'll take you."

"I am a doctor," I said quickly, and gave him my card. "Whatever she is, I can't leave her alone in this state—Help me to take her in here."

There was an eating-house just where this occurrence had taken place, and, aided by the constable, I got the woman inside and sat her down in a corner box. The crowd dispersed. As they did so, a draggled harlot called out:—

"The old gent's in for it all right—good luck to him!" And the strange sobriquet was bandied from foul mouth to foul mouth— "Menagerie Sal—Menagerie Sal!"

I sent for some brandy and sat, looking at her as she gradually recovered her self-possession, without saying a word. At last she gave utterance to a short hoarse laugh, and said:—

"What the hell did you do it for? You told me to go there, and I tried to. Yer don't want me; what did yer stop me for?"

"True," I said, "I don't want you, but I couldn't let you kill yourself before my eyes. I'm a man, not a brute."

"All men are brutes," she said defiantly.

There was a most extraordinary struggle of accents in her speech. She spoke the low cockney vernacular with fluency and emphasis, but occasional words, intonations, seemed to jar against the vulgarity of the rest of it.

"Not all," I replied. "Myself for instance. Now look here. I'll turn your own question on you—what did you do it for?"

"What's that to you?"

"It's a good deal. You are too young and healthy to want to die, however beastly your life may be. Whilst there's life there's hope. You are worth saving."

"Saving! My Gawd! let me up and out of this. You're a bloody gospeller, that's what you are. You're going to talk about the Temple of my Body, and Gawd and that. I ain't a Temple, it's a Cesspool, and there ain't no Gawd. Let me go!"

"I am not a gospeller, and I don't want to preach to you; but I'm a doctor and I want to know what it all means."

"It means that I'm down and out—I've stuck it long enough. You heard what they call me 'Menagerie Sal' (she pronounced 'Menagerie' perfectly) I'm too low down for any self-respecting whore to speak to—I can't get a lodging except in a Chinks' Dive, and I can't get a man unless he's a stranger in these parts—that's why I clawed you—or a right down utter beast of a heathen."

"You are in a wildly hysterical state—that's evident. Now look here, I've saved your life and you belong to me until I've done with you." The wretched creature turned on a professional smile. "Don't misunderstand me—I'm not going to have you, but I'm going to make you eat something—hungry?"

"I don't know—I ought to be. I know I've been empty as a drum for two days. I wonder what you're getting at?"

"Nothing in particular," I replied, "but you are going to have some food. We can't sit here and do nothing for the good of the house."

I ordered some food, which arrived, coarse, but plain and good, and she ate sparingly—and with a strange refinement contrasting remarkably with her vocabulary. When she would eat no more, I lit a pipe and gave her a cigarette. She had calmed down.

"Now look here," I said again; "do you feel anything like gratitude to me for what I've done!"

"No, I don't," she replied; "but that doesn't matter. There are other ways. I'll do it when there's no interfering Toff around."

"No you won't. You are going to promise me not to do it again."

She looked me straight in the face without speaking, her chin resting on her hand, puffing cigarette smoke quietly, so as not to reach me.

At last I said, "Well?"

She replied, "Shut up! I'm thinking."

"A penny for your thoughts!"

"I'll take the penny. I want one. You couldn't make it a shilling, I suppose?"

I laid a sovereign on the table. "Will that help you out a bit?" I asked.

"Haven't seen one for years. Ta, Governor." And she deftly slipped the coin into her stocking and resumed her scrutiny of my face.

"You haven't told me your thoughts—and I've paid," I suggested.

And then I experienced the shock which Balaam must have felt when his Ass addressed him. She took her cigarette from her lips and said quite slowly and without a trace of cockney accent:—

"You look like an intelligent man—I should say a scientist of sorts—not many doctors are scientists down this way. How can you be such an idiot as to ask me to promise you not to do it again? Do you remember what that girl, Wade, in 'Little Dorrit' said to the champion ass Clennam? (by the way I've often wondered if Dickens knew he was describing a Lesbian)—you know—about people who are all the time coming to meet us from strange places along strange roads, and what they'll do to us, and we to them will all be done? Whether I do it again or not has nothing to do with me; it depends at the moment upon you, or rather upon the puny little part you happen to be playing in the inexorable progress of inevitable consequences."

I was dumbfounded! It was my turn to sit and gaze at her. "This way and that, dividing the swift mind"—and she, taking up my case from the table where I had laid it, took a new cigarette, lit it, said "Thank you", and resumed her position, her chin on her hands, looking at me.

At last I said: "How in God's name have you come to this?—you are too good—"

"Oh! Don't begin that—that's what that the Missioners to Fallen Women begin with. And don't bring in God—unless you feel the need of him for conversational emphasis—or convenience, like Xerxes at the end of a rhyming alphabet."

"Let's put it on the lowest grounds then. You are a woman of some education evidently—and, permit me to say—of some refinement. You are too good for Ratcliffe Highway. If prostitution is your vocation in life, why not practise in the West End? Why not the Empire or the Alhambra?" (The "promenades" at these places had not been closed in those days).

"Never mind when or where I started—that's none of your business. I came to grief on a P. and O. steamer—I'd had lots of men—some of the best; but coming home once from China I fell madly in love with a Lascar. A common ship's hand—a bronze god. I wanted him—and I seduced him; it didn't take much doing—I had some money then—but I was ashamed (I was capable of it then) to take him up West. I joined him down here. I used to go up West myself sometimes—no one here knew it—when I was just longing for love—real love—a woman."

"A woman?"

"Yes—for a real lover, or mistress. Oh! don't look shocked; if you're a doctor you know women can love a woman better than any man on earth."

"Then—among other things—you are a—"

"Lesbian—don't be afraid to say it."

"But I don't understand how you—"

"It's easy enough. Men don't hear of the brothels where women can have anything they want and can pay for, from a vicious flapper of fifteen to an insatiable Messalina of fifty. The only difference between those, and—the others—is that all the ‘staff' are amateurs; some shop-girls and clerks, but mostly gentlewomen. You've never heard of No. 100, Canterbury Square have you?—no, it's kept pretty quiet—but I didn't go there, I preferred to find my own romances."

"Romances!"

"Yes—can't you imagine the delight, after the brutes down here, of meeting eyes in an omnibus, of a thigh pressed against yours, of a foot that touches yours as if by accident? Of seeing a pretty shop-girl go scarlet when you squeeze her hand as she hands you a parcel? A few ordinary words—a suggestion of meeting again, and then tea together somewhere, and, later, dinner and a night spent in love that leaves you shattered and sleepy and dreaming for days?"

"It seems horrible to me."

"That's because you are a man and don't know what love—really exquisite love—means. Very few men do—but when they do they're divine!"

"But did you not horrify them—at first?"

"Never. We know one another in a flash. The most wonderful love I ever had was a girl of nineteen—the daughter of a peer—Oh! She had been to a good school—a finishing school—it finished her, I can tell you. I got to know her people. Oh! yes, I can be a gentlewoman when I like, and I took her away into the country for a week. I bet you she remembers it, as I do. And then—back to my brute. He'd have been after me otherwise (he thought I'd gone to get more money), and then there would have been hell—and blackmail. So long as my money lasted we lived in a fairly decent set of rooms, and we had a wonderful time, but my God! he was a brute; he thrashed me sometimes—I loved it. And vicious!—I don't want to make your hair stand on end. I'd read a lot of filthy books here and abroad and I thought I knew what vice was. The things he did to me—and that he made me do! I tell you the Five Cities of the Plain rolled into one were a Trappist Monastery compared to our flat. And his friends that he brought to me—and their animals—-you people west of Chancery Lane can't dream what are the vices among the Lascars, Chinamen. Malays, half-breed Spanish-Americans, Niggers, Mulattos of all kinds. One didn't know at the end of an orgy whether one was a girl, or a boy, or a beast. Lucky animals can't breed with humans."

A strange, bitter smile flickered over her lips.

"Now my friend," she continued recklessly, "you know what you've 'saved.' You heard what they called me—Menagerie Sal."

Literally my hair did stand on end. At least, I felt a cold contraction of the scalp, and my sight vacillated.

"This is too horrible. How could you—why did you—stand it?"

"I liked it."

"What?"

"I don't want you to take home any illusions about a repentant sinner. And I've paid for it—my God! I have paid for it. When my money was gone—I had quite a good deal and it lasted a longish time, I sank, if one could sink below that—but one is always comparatively up, when one can pay; I sank lower and lower, the most vicious of the Scum knew of me all over the world, and came to me like filings to a magnet. It was too late to get away. I was 'Menagerie Sal'—the Darling of the Beasts—human and otherwise—and that's where I am now. I told you the truth just now when I said that no self-respecting whore would be seen speaking to me—and if any clean white man showed any signs of wanting me, they are all round me and on to him—at once—telling him things—mostly true—and what's more, none of them would go with a man if they knew he'd been with me. You know there are grades of respectability even among harlots—I am afraid I am shockingly mal vue in the oldest profession in the world, even as practiced in Ratcliffe Highway! It is not often that I have enough to eat—I shouldn't be allowed in here if you hadn't brought me. Now you know why I am going to kill myself. If I don't, one of the brutes will kill me some day. See this scar?" and she pulled her blouse away upon her shoulder, "that was done by a sort of Gorilla—I was trying to get away from him. So I am going to 'out it'—don't you think I'm right?"

I could not answer. I was paralysed with horror, especially by the calm manner with which she spoke of these unspeakable atrocities. I harked back, and repeated in an undertone:—

"You like it!"

"Yes—sometimes—that's the truth. But I'm afraid of the end of it—afraid!" and she covered her face with her hands and shuddered.

I sat looking at her—at last, as though she were a curious pathological case in a mental Hospital. And then a horrible but irresistible thought came into my mind. The Cheetah!

I BEGAN, my heart beating violently, to feel my way.

"What a life!" I said. "But I confess you interest me dreadfully"

"Do I?" she said suddenly looking up; "Aren't you disgusted?" Then she gave a short laugh and said: "I wonder! Well—I expect you'd be as bad as any of them if you had a chance—if the truth were only known—"

"And suppose I were?"

"Oh! I shouldn't mind—I've been through too much. But I am surprised—you with your solemn learned old air,"

I thought rapidly, and then, to my eternal misery, I made up my mind. Such a chance could never occur again. I said:—

"Supposing I were a worn out old rake, with unnameable curiosities? Jaded with all ordinary vices? And supposing I said to you, 'Come away from here, come and live in the country. I'll settle a sum of money upon you which will keep you from want in the event of my death. I am a Scientist—a vicious one, if you like. I should want to try all kinds of experiments on you.' What would you say?"

"I'd say, as the Yanks do: 'Put it there, Governor.' You can't do anything worse to me than I've had done to me already. And I'd love to be away from all this mob. When do we start?"

We talked on for half-an-hour and then I left her. She gave me an address to write to—at a Poste Restante.

A month later she was installed in a cottage in the village where I then had my Research Laboratory. She had no desire to mix with the people of the place, but for the information of the public and the parson, she gave herself out to be a young widow. The name she adopted was Mrs. Clayton. Of course it was immediately observed that she had come there at my instigation, and that when I was at the Laboratory she was constantly at my house. They drew their own—the inevitable—conclusions, but, as I had steadily repelled any attempt on the part of the aborigines to establish social relations with me of any kind, this did not trouble us.

Ursula Clayton left behind her in the parlieus of the Docks every trace of her "professional" career, accent, vocabulary and manner. When my solicitor (who with my assistant Rex Magley will be trustee of my will) had proved to her that a certain income was settled upon her in any event, she abandoned all reserve with me; hitherto our relations had been a trifle strained; she seemed unable to realize that I was determined to act in her permanent interest, and was not merely amusing myself with her for a time. She became a really delightful companion; I was a bachelor, and never at any time an Anchorite, and the society of Ursula Clayton was interesting—and satisfying in every respect. I gradually came to know her history, which, though it does not concern this narrative, is illuminating as an explanation of her abnormal sexuality.

In the eighties of the last century, there are still people old enough to remember, a hot wave of what are known as Unnatural Vices almost openly and unblushingly practiced, swept over our English Society. It was the outcome of the Aesthetic Craze, intimately associated with the name of Oscar Tilde, who ultimately, in the nineties, paid for everyone, and subsequently died overwhelmed with public infamy, and the private admiration of the few. It became a matter of ordinary conversation to discuss homosexual love affairs of men and women prominent in Society—especially of the latter. In a word, Sodomy and Lesbianism were—sub rosâ—fashionable. Pre-eminent among the male "perverts" was a well-known Peer of artistic taste and enormous wealth, at whose house in the county homosexualists of both sexes congregated, and where, as was averred, "orgies" took place that were spoken about with bated breath in the most fashionable boudoirs. Prominent in this society was a very high-born dame indeed, in whose hands, or arms, no woman was safe, and she formed the centre of a Lesbian côterie which spread like a rodent ulcer into almost every class of society. It was in the unnatural order of things that the masculinity of the Lady, and the femininity of the Lord X—, should bring them closely together, so closely indeed that, to the astonishment of the inverted world, Lady Z—gave birth to a child who was christened Ursula. This child was sent abroad, to be brought up in Italy. A respectable sum of money was "settled" for her maintenance and education which became hers absolutely on attaining her majority. With such an heredity it is not surprising that Ursula developed, early, a sexual precocity and désinvolture, which the settlement made upon her by her parents enabled her to gratify to the fullest extent of her inclination. She told me her early sexual history, which was amazing, but does not concern us, beyond what she told me in Ratcliffe Highway, and which I have already recorded. By the time she came to "our village" her fires were burning low, her sexuality was to a great extent satiated, and she showed no trace in her manner or proclivities of the storms which had disturbed her youth. She was a charming companion, an intelligent and well-educated friend, and a charming mistress.

And the Cheetah? We called him "Kumar". He settled down in our two houses as a great affectionate domestic pet. Sometimes, in passage between the two, led on a chain by Ursula, he terrified the inhabitants of the village, human and animal, but this was very seldom, and the villagers had grown accustomed to what was known as "the Professor's Zoo." The attachment between "Kumar" and Ursula became very close, and indeed I sometimes feared a precipitation of events, but Ursula was too keenly interested in my work to endanger the results by premature action. I conducted my experiment on the lines suggested by Milne-Edwards; it was nothing to inoculate Kumar under a local anaesthetic—he would never have dreamed of the possibility of being hurt by either of us.

The day arrived when the blood tests were wholly satisfactory. The serum of the one accommodated the corpuscles of the other without any trace of haemolysis—and I left the rest to Ursula.

I DO not know what I expected to be the outcome of this experiment. It was impossible to anticipate. As a practising surgeon I was skilled in obstetrics and had no fear for the result, only an intense curiosity. If I expected anything, it was a queer little "monster," which I should allow to live long enough to be perfectly formed, and then "prepare" as a specimen, explaining its presence as an arrival from a native collector in India. At the end of only six months anticipation Ursula gave birth to one of the most perfectly formed little female children it has ever been my lot to look upon. She was remarkably furry, but new-born babies are often thus, and, as in the case of this child, they lose it in a month or two. I should mention, though it is not material, that I took a house on the South Coast for Ursula to await the event. I delivered her myself, and she brought the child, whom we had registered as of illegitimate birth under another name, and had baptized Uniqua—the only apposite name, it seemed to me—back to our village. There could not be any question of destroying so perfect a little specimen of humanity, and when Ursula returned with her, she "explained" her, when necessary as a foundling she had adopted from a workhouse on her travels.

(I WILL not try to set down here what were my thoughts as I read this frightful record. They are indescribable—it was all I could do to prevent myself burning the MS. and taking five grains of morphine on the spot. But I dared not do it. I had to read on, though it was now broad daylight.)