RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

IN an article published on June 18, 1911, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote:

At a recent Saturday night house dinner at the celebrated Savage Club of London, E. Phillips Oppenheim, the popular novelist, who presided, read a rhymed "roast" on himself to the amusement of 100 brother "Savages." The "poem," which originated in America, begins as follows:

I have read your latest book, Oppenheim;

it involves a swarthy crook, Oppenheim;

and a maid with languid eyes,

and a diplomat who lies,

and a dowager who sighs, Oppenheim, Oppenheim,

and your glory never dies, Oppenheim.

These lines were written by the then highly popular author-poet-journalist Walt Mason (1862-1939) of Emporia, Kansas, who writings were syndicated under the name "Uncle Walt." A book with a collection of his writings was published in 1910 by George Matthew Adams Co., Chicago under the title Uncle Walt: The Poet Philosopher. Here is the full text of Mason's poem about E. Phillips Oppenheim as it appeared in this collection.

I have read your latest book, Oppenheim;

it involves a swarthy crook, Oppenheim;

and a maid with languid eyes,

and a diplomat who lies,

and a dowager who sighs, Oppenheim, Oppenheim,

and your glory never dies, Oppenheim.

Oh, your formula is great, Oppenheim!

Write your novels by the crate, Oppenheim!

When we buy your latest book

we are sure to find the crook,

and the diplomat and dook, Oppenheim, Oppenheim,

and the countess and the cook, Oppenheim!

You are surely baling hay, Oppenheim,

for you write a book a day, Oppenheim;

from your fertile brain the rot

comes a-pouring, smoking hot,

and you use the same old plot, Oppenheim, Oppenheim,

but it seems to hit the spot, Oppenheim!

You're in all the magazines, Oppenheim;

same old figures, same old scenes, Oppenheim;

same old counts and diplomats,

Dime Musée* aristocrats,

same old cozy corner chats, Oppenheim, Oppenheim,

and we cry the same old "Rats!" Oppenheim.

If you'd only rest a day, Oppenheim!

If you'd throw your pen away, Oppenheim!

If there'd only come a time

when we'd see no yarn or rhyme

'neath the name of Oppenheim, Oppenheim, Oppenheim.

It would truly be sublime, Oppenheim!

* Dime museums were institutions that were popular at the end of the 19th century in the United States. Designed as centers for entertainment and moral education for the working class (lowbrow), the museums were distinctly different from upper-middle class cultural events (highbrow). Wikipedia

IT has been said that success is one of the greatest of a great man's qualities. Certainly most successful men whom I have known have thoroughly enjoyed their success. There is, of course, a common affectation to pretend that no success is worth having, that the game is not worth the candle, and that the prize is always a Dead Sea apple. But this is generally nothing but a kindly pretence intended to solace the unsuccessful. Sometimes, of course, success is so hard to win and the struggle so long and strenuous that, when the goal is reached, the power of enjoyment has departed. But this is the exceptional case. The rule is that success is a very jolly thing to have, and the jolliest sort of success is that which comes to a man whose work brings pleasure and enjoyment to his fellows.

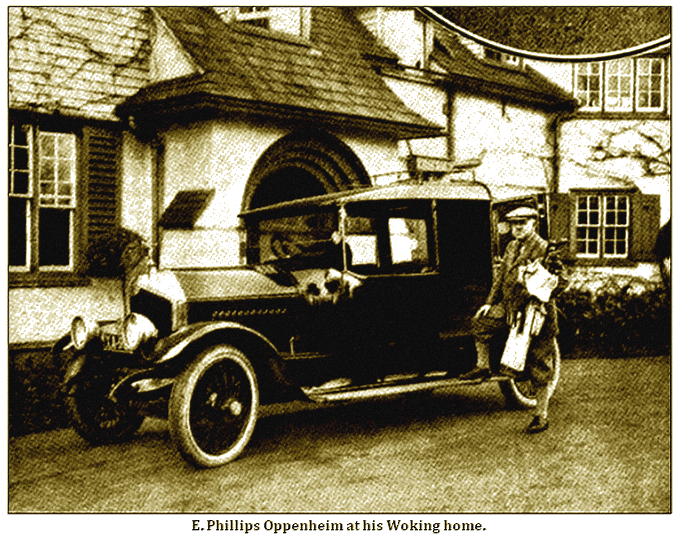

I know no man who more obviously enjoys or more thoroughly deserves success than E. Phillips Oppenheim, the novelist, whose well-conceived, well-constructed stories are so familiar to readers of The Strand Magazine. Oppenheim is a man of fifty-four—of middle height and, in these days, tending to stoutness. But his stoutness is not that of the over-fed, under- exercised townsman, but merely the common evidence of the approach of comfortable middle life. Oppenheim, indeed, like so many other successful writers, is essentially a countryman. For twenty years he has lived away from London, in Leicestershire, in Norfolk, and more recently in Devonshire. Oppenheim is a keen open-air man, an excellent shot, a good golfer, and addicted to sea fishing. He flourishes best in the bracing air of the East Coast, and he found the atmosphere of the West a little enervating and, he says, a little depressing, though I am bound to confess I find it hard to believe that he can be depressed anywhere or in any circumstances. Anyway, he has recently given up his Devonshire home and now lives at Woking, with a little flat in Mayfair, conveniently situated over a famous Bridge club, Oppenheim being, among other things, a conspicuously good bridge player.

As I have already suggested, the quality of the man is

cheerfulness. He meets you with a smile that has nothing whatever

to do with "company manners." He smiles while he gossips. He

smiles when he says good-bye—not the uncomfortable smile

that makes you feel that he is glad you are going, but a

flattering smile that makes you feel sure that he will be glad

when you come again. His most striking feature are his light blue

eyes, rather out-of-the-way, steadfast eyes that, as eyes always

do, tell a good deal of the man's character. There is a

suggestion of the practical in the manner in which his eyes

fasten on you as he talks, and Oppenheim is eminently a practical

person. He was brought up to be a business man, and he was a

business man until he was thirty-five. Even then he did not

really cease to be a business man. The modern English writer is

generally conspicuously clever in obtaining the full pecuniary

reward for his work. If Barabbas is still a publisher, he must

certainly be a semi-bankrupt publisher. Men like H. G. Wells and

Arnold Bennett see to it that they obtain all that their work is

worth, and Oppenheim has the same justifiable habit. But while

his eyes suggest this business acumen, they also indicate the

amazing imagination of a man who can write novel after novel

without ever repeating incidents or making characters mere

imitations of their predecessors.

Oppenheim's first novel was published when he was twenty years old. He has therefore been writing fiction for thirty-four years, and during this time he has produced no fewer than seventy separate novels and collections of short stories. In a review of his first novel, "Expiation," a writer in the Athenaeum compared the story to those James Payn used to write before he discovered he had humour. Oppenheim has made the same discovery since. Thirty years ago Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, with his Sherlock Holmes series, invented the idea of writing a number of short stories each having the same leading characters. Phillips Oppenheim at once realized the advantage of this scheme from the point of view of the story writer. It meant economy in invention. And he was one of the first writers to develop the Conan Doyle idea. Another advantage of a series of short stories with the same central theme is that they make a far better and more interesting volume than a number of stories with different characters, different plots, and written in different veins.

Oppenheim's first story was a sufficient success to convince him that it was worth while to continue writing fiction. He sold the serial rights of his second story for fifty pounds, and two years afterwards he received an offer for the serial rights of a story of two hundred and fifty pounds from the proprietors of the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph. Oppenheim told me that he remembers that, when this offer came to him, he felt that his fortune was made, and indeed it may be said to have been the beginning of his fame. He continued to write serials for the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph for fifteen years, and he recalls the long association with almost affectionate gratitude for the consideration and encouragement he received.

Oppenheim's father was a leather merchant, and after his death his son was compelled for some years to assist in the direction of the business. But in this, as in almost everything in his life, fortune dealt him the winning cards. His business associates appreciated his talents and made it easy for him to devote a certain part of his time to fiction. But it was not until he was thirty-five that he was able to retire from business and to devote himself entirely to literature.

I have used the word literature designedly, because the Oppenheim novels have a distinction that makes them different in kind to the rut of popular fiction. The drama is always well stage-managed. Incredible coincidence is rarely, if ever, employed. And the writing has form and style. It is remarkable enough that one man should have been able to turn out two novels a year for over thirty years. It is much more remarkable that there should be no falling-off in the character work, and that, on the contrary, his last work should generally be his best. Oppenheim told me that his latest novel, "The Great Impersonation," is the greatest success he ever had. For six months it was one of the six "best sellers" in America and it has had a corresponding sale in this country. Unfortunately, it frequently happens that fiction of the smallest artistic value produces the most satisfactory pecuniary results. "The Great Impersonation," however, has pleased the critics as much as it has pleased the great reading public. Sir William Robertson Nicoll calls it a "mighty yarn," and he says:—

"There are no difficulties in the way of accepting its statements and situations. These are followed out with the most marvellous and meticulous skill. There is not a weak spot in the working out of a difficult and delicate plot. The triumph, however, of the book is its conclusion. The solution of the mystery is reached at last, just as the reader has settled down to believe that there is no mystery at all."

I have quoted this eulogy from a critic of unrivalled

authority since it indicates one of Phillips Oppenheim's greatest

qualities. His situations may be outside the common experience of

his readers, but they are never incredible. He may deal with

improbabilities, but he always persuades that the improbabilities

are at least possible. Sir William Robertson Nicoll says that he

has written "one of the greatest yarns in the English

language."

E. Phillips Oppenheim is modest about his achievements, and certainly does not talk readily about his success, but he will admit that he is above all other things a storyteller, and he suggested to me that it is because, unlike the needy knife- grinder, he always has a story to tell that his books are so popular in the United States.

"The Americans," he said, "are great story readers. I don't think they are much interested in modern introspective fiction. They love colour and movement and situations. Give them that and they are satisfied, and, of course, if you have skill to add to that they are still more delighted. Joseph Conrad and W.J. Locke are the two most popular English novelists in America to-day, and both of them, whatever else they may do, write novels with a full-blooded plot."

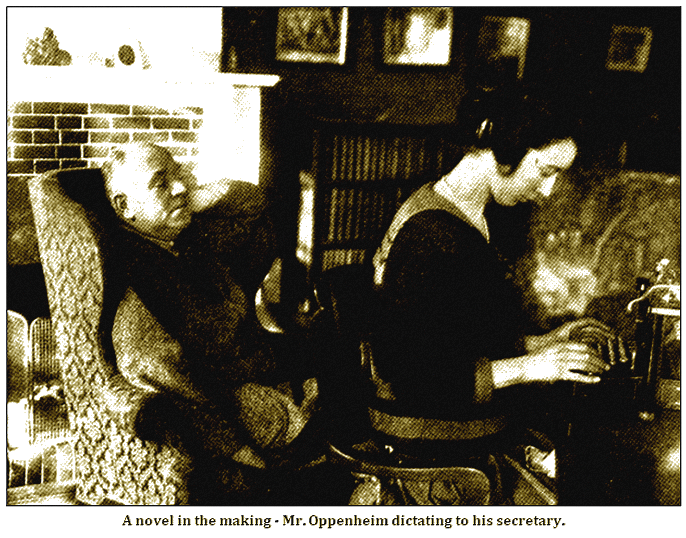

No man could have an output equal to Oppenheim's without persistent industry. The novelist who waits for inspiration, and who can never write unless he is "in the mood," will certainly never publish two novels and a volume of short stories in one year. Perhaps it would be truest to say of Oppenheim that he is always in the mood. He is lucky enough to possess a very expert secretary who has been with him for a number of years, and he dictates to her everything that he writes. Sometimes the secretary takes down in shorthand. More often she types straight on to the machine.

The novelist's favourite position, while he works, is to sit

hunched upon a low easy chair. When he is in the country he will

generally work from about a quarter past nine to twelve. Then he

will play golf or tennis for an hour or so, returning to work

early in the afternoon and going on until nearlv dinner-time. On

a good day he will dictate about five thousand words, and an

average day will mean about four thousand words. Every third or

fourth day he takes a holiday and does no work at all.

Oppenheim practices his drive.

In the popular novel the situation is certainly a greater

asset towards success than the characterization. It is what the

characters do rather than what they are that interests the

readers. It might therefore be supposed that the successful

popular novelist would begin by conceiving a series of

situations, and that he would afterwards invent characters to fit

those situations. Oppenheim tells me that his method is exactly

the opposite. He begins a novel with two or three characters, and

then (to use his own phrase) he lets them rip. When he begins his

novel he rarely has any idea what will happen to the characters,

what will be the chief situation, what will be the curtains. The

characters being created in his brain, he spends his life with

them, has them with him as his partners or opponents at golf,

takes them with him when he goes out fishing, even has them with

him when he goes to bed—always trying to find out what such

people would do in certain circumstances. It often happens, he

told me, that two entirely different development s occur to him,

and he then has to decide what is the most likely and the most

appropriate.

Just as it as in real life—to quote George Eliot's

hackneyed couplet:—

"Our deeds still follow from afar

And what we have been makes us what we are,"

so the actions of the Oppenheim characters in Chapter One of each of his novels really determine what they shall do in Chapter Two, and so on until the end of the story. The intrigue being constantly in the novelist's mind, he is able to dictate his stories rapidly and sometimes for hours on end almost without hesitation. When, however, the dictation is finished, the stories are very carefully revised, and Oppenheim says that the revision generally takes much longer than the original dictation.

Oppenheim recalls, with perhaps a little satisfaction, that in his "The Maker of History" and other novels he foretold war between Great Britain and Germany ten years before the Great War broke out, and that he did something to back Lord Roberts in his insistent endeavours to persuade this country to prepare for what he believed was an inevitable conflict. Germany, Oppenheim says, realized the part he had tried to play, and he was among those who were destined to be shot had the Germans succeeded in imposing their will on England. So repeated was this German note in his novels that, when war actually began, one newspaper said that it had at least robbed Oppenheim of his vocation. During the war he was among the many novelists who assisted in the work of the Ministry of Information.

"I suppose I must admit," he said, "that my name suggests a German origin, and perhaps it is of some interest that my father and his father before him were both born at Faringdon, in Berkshire, and that I have hardly ever been in Germany in my life."

I asked Oppenheim if he felt that the English reading public was becoming more critical, and if he had noticed any change in public taste during his long, successful career.

"Of course," he replied, "the world is always changing. I myself am very different from the man I was twenty years ago, and I suppose my work must be different too. I fancy that the reading public in England is more exacting than it was, that it is quicker in detecting blunders, that it is more intelligent and critical. My appreciation of these facts leads me to take far more care with the revision of my stories than I used to do. It is a care that I give very willingly, for nothing is more stimulating to a writer than to realize that he will be read critically, and nothing can be more delightful than the whole- hearted appreciation of a really critical public."

Within recent years a number of the Oppenheim novels have been turned into picture plays, and the development of the cinema marks a new era in the novelist's career. I asked him if he found that the picture plays founded on his novels were very unlike the original.

"There are," he replied, "I suppose, inevitably many additions and alterations. At present I know hardly anything of the conditions under which picture plays are produced, and I am having the thrilling experience of learning a new art."

Oppenheim was recently asked by a famous firm of American film producers to supply them with an original plot suitable for a picture play. It was an entirely new task for him. I have already explained that he lets his stories develop from the characters, and that he never begins, as many novelists begin, with a sort of synopsis of the plot. But this is exactly what is required for a picture play—a story told on six pages of foolscap, and told in such a way that it can be cut up into scenes and repeated in pictures instead of in words. Oppenheim confessed that he was delighted to have a new experience, and he added, with his characteristic twinkle, that he understands that his picture play plot has been approved by the authorities.

"Instead of the picture play being made from the novel, as has happened until now with me, the novel will be a sort of development of the picture play, for I certainly intend to use the theme of the play for one of my forthcoming novels."

"If this were to become the rule," I said, "don't you think that the limitations of the cinematograph might have serious and, on the whole, very evil effects on the art of fiction?"

"It is very possible that they might. I am not sure, for the whole thing is quite new to me. But I am conscious of the possibility, and for that reason I am determined, however my cinema work may develop, to continue to write novels which will begin as novels, and which shall be conceived and worked out as novels."

Oppenheim recalls with pride that Sir James Barrie is one of his most faithful admirers. Sir James has all the Oppenheim novels specially bound in similar bindings.

WAR is upon us, thundering at our gates the real war of bloodshed, of ruined homes of hatred, of lust and rapine, of gigantic; world-shattering passion born but once in a thousand years. From the Urals, across the Carpathians, over outraged Belgium and the pleasant plains of France, the harvest of summer has become the harvest of death. Our own freedom, our great Empire, our whole creed of civilisation, trembles now in the balance. And the most amazing thing of it all is that a single man or woman of us in this country should pretend to be surprised.

For generations the ostrich head of our people has buried itself, year by year, a little further in the sands. Even the casual student of history, the most superficial observer of German ideals of German ambitions, of German policy, has seen before him the absolute inevitability of what has now come to pass. Let us English men and women at least be honest with ourselves. This war finds us unprepared in the one essential thing. As usual we wake up too late and lash our selves into belated realisation. The columns of our papers are filled with verbose outpourings and avalanches of rhetoric addressed to the young men of England--excellent all in their way, but tardy. These passionate pleadings, which from their very haste and fervor must savor now almost of hysteria, are simply an exuberant form of what should have been the sober text of our every-day life.

May I, for my, own selfish satisfaction, refer to a novel of mine, entitled "The Illustrious Prince;" published three or four years ago. The hero was a young Japanese prince sent over here by his Government to report upon our national character and institutions. His report was unfavorable and he departed to his country, predicting that before many years had passed England's day of trial, would come. "Nothing." he declares, "will wake your people but war itself. Nothing but tribulation will raise the thoughts and ideals of your young men." The war has come and we are awake. We are going to suffer as it is only right that we should suffer. As a nation we have been handicapped for many years by too great a prosperity, too great a love of sports, too little regard for the vital and serious things of life.

We are going to pay for it, but the end is certain. As a nation we shall rise even to the heights necessary to surmount and triumph at this crisis. But at what a cost--what a pitiful, unnecessary cost!

This article appeared in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle under the header:

OPPENHEIM TELLS HOW WORD "PEACE" STIRS

POILUS' ANGER

NOVELIST DRAWS GRAPHIC PICTURE OF

FRENCH

SOLDIERS' WRATH AT KAISER'S OFFER

"STINKS IN OUR

NOSTRILS."

"WE SHALL FIGHT UNTIL FRANCE SAFE"

WILSON'S

NOTE TERMED PEACE BABBLE.

"What the Poilu Thought" is the title of the following article written by E. Phillips Oppenheim, the English novelist, and placed by him at the disposal of The Eagle. Mr. Oppenheim recently visited the Anglo-British fronts in France.

"As an example of how widely President Wilson's peace note was misread abroad," writes Henry Suydam, The Eagle's London correspondent, in forwarding Mr. Oppenheim's story, "it is interesting to note that Mr. Oppenheim refers to the note as 'peace babble' and makes his French soldier say, 'What did M. le Président mean when, in black and white, he set it down as an accepted thing that Germany, that our enemies, were fighting for the same cause as we—the cause of the smaller nations? Have they never heard of Belgium over there?'"

IT was a slow and tedious crawl in the long French train away from the battle-scarred country. There was nothing particular going on at the front, yet we seemed to be continually shunted for the passing of huge supply trains, moving eternally in the other direction. When the morning twilight rolled slowly away from the face of the country, leaving at first little clouds of white mist hovering over the freshly-plowed fields, the sound of the guns was still in our ears. The face of the country, however, had changed. There were farmhouses to be seen, some of them intact and apparently prosperous; a château or two on the hillside, old men and women and young girls at work in the fields.

We stopped at the station of some small town, and stretched out our eager hands for the cups of hot coffee and the rolls and butter wheeled along the length of the platform. The warmth of the coffee was like a talisman. My two companions thawed as I did under its genial influence. Monsieur Poilu accepted a sip from my flask and a cigarette with a grateful little ejaculation. Madame, elderly, in deep mourning, a little shabby, but wonderfully neat, beamed content upon us. The smoke did not incommode her. As for the flask—ah, well, she took only coffee and a little wine and water herself, but nothing in the world was too good for the brave soldiers.

CONVERSATION blossomed out between the two, and flourished. At first I barely listened. We were passing through a marshy district, which reminded me of home—little pools of water, tall rushes moving in the morning breeze, sedgy places, from which, at the sound of the shrill whistle of our locomotive, a flight of duck rose hastily. Then I heard a word behind me which in these days inevitably stirs the blood. The word was "Peace." I turned away from the window and listened.

"But, my son, have patience,", the old woman was saying. "I speak who may speak, for I have lost a husband and two sons. Yet I have others fighting, and it is of them I think. If indeed these Boches are weary of fighting, if indeed it is peace they offer, why should one not at least listen?"

The Poilu turned toward her. His haversacks, with their queer collection of miscellaneous articles, was on the seat by his side. The mud of the trenches was thick upon his clothes. There was a week's beard bristling upon his chin. Yet his voice suddenly proclaimed him a man of some education.

"Madame," he demanded, "who are they to offer peace as a gift, they who deliberately brought this war upon the world? And what sort of a peace do you suppose is in their minds? You have read the boastful, arrogant words of their Emperor's declaration? Is there anything there of the humility of the wrongdoer, of the man who wishes to restore what he has stolen, to repair the greatest wrongs which have ever stained the pages of history? Peace, Indeed, mother! There is no peace in their hearts."

Madame sighed. She felt herself no match for this man in whom her words had kindled a sudden eloquence. But in her heart there was the longing.

"THEY are brutes and savages, my son," she admitted, "and our people would do well never to clasp again in friendship the hand of one of them. But, behold, I have two sons left. I have lost much and suffered much. Day by day I have seen the losses of those about me increasing. I am 58 years-old, and peace would give me me back my two sons. There are so many like me."

"Madame" the soldier answered, and this time he seemed to include me in the argument. "Peace will not give back to the many hundreds of thousands of French mothers the sons and husbands they have lost. Peace would only dishonor their memories, would bring the cruelest of all bitterness into their lives. Look you, they fought for their homes and their womenkind, they fought for a sacred cause, they fought for others besides themselves. See how it is today with those others. Belgium! Can one speak of it! It is Belgium who shall make peace when it comes. Who has a better right? What will she ask for, I wonder? Fifty thousand German men and women to make slaves of them? The maidenhood of Germany to debauch? No; they are not Boches; but strict justice would give them all that and more."

Madame shook her head. She, too, was moved.

"ONE must forget," she muttered. "I had a niece myself at Lille—but one must not speak of those horrors. God alone can punish such crimes."

The Poilu rolled another cigarette viciously.

"Monsieur," he said, glancing across at me, "I appeal to you. You are English, are you not?"

"I am English," I told him, "but with your permission I will be silent. Even our friends call us a somewhat obstinate nation. They say that we find difficulty in seeing any side of these great issues save our own. Let me hear you speak more of this peace."

The Poilu lit his cigarette. Madame leaned forward.

"Listen," she intervened. "I have heard it said that the Boches now are willing to restore all Belgium, that they will give back the whole of their conquered territory."

"If we leave their military machine, their great engine of tyranny, autocracy, aggression and destruction, with all the power in it that made them begin the war," the Poilu interrupted vigorously. "Ah Madame, there is the trap. We trusted once to German treaties and German faith. See how they regarded them. Treaties! It was Germany who dismissed them with the immortal phrase 'mere scraps of paper.' Promises! Listen, madame. Their own chancellor—he stood up in their parliament and he pleaded guilty to a great broken faith. Necessity, he declared, demanded it. And I tell you this. When necessity which, with them, means German ambition, demands anything, then a German promise and a German treaty are worth just a snap of the fingers—no more! That is why I say—I, and those others who have lived and fought through these desolate years—that with an unconquered Germany there can be no peace."

"My son," the old lady declared, looking at him with interest, "you speak like one who has thought much."

The Poilu glanced down at his mud-stained clothes.

"I WAS an advocate's clerk before the war," he said, grimly. "What I am now God only knows; but up there in the front it is not all fighting. There are long, lonely hours when the brain works, hours of solitude when one sees the truth."

Madame sighed.

"It is not often." she confessed, "that I read the journals. My eyesight is failing, and my daughter—well, we will not speak of her. I lost her. Therefore, it is a new thing for me to talk to one like yourself. Remember now if you please that I speak only in the language of the village. They say—I have heard it said—that Germany hungers for peace, that therefore it is better for us to give peace now, and so spare needless suffering."

A little cloud of smoke surrounded the soldier's head. His clenched fist struck the knapsack by his side. His eyes—hot and red they were with fatigue—flashed.

"They talk like cattle, madame," he declared vigorously. "Where are Germany's conquests? Belgium, with odds against her of ten to one in men and fifty to one in artillery! Montenegro—a mountain tribe. Serbia? Well, it took them eighteen months and cost them a good many army corps to drive the Serbians from their country and the end of them is not yet. Rumania? Victims of a foolish campaign, if you will, but even then overpowered with the war machine which it has taken Germany, thirty-five years to evolve. Where are her victories against France, or Russia, or England? Her victories, I say, when you come to consider that for forty years she was slowly preparing whilst we refused to believe. Man for man, gun for gun, we are the better race. England is the better race, Russia is the better race. Therefore I say to you, madame, wait. Germany's last hour of triumph has struck. England has gathered strength beyond all that was expected. France stands firm and undismayed, ready to spring when the hour comes. And Russia—Russia has shown what she can do. Wait till the mountain snows have gone. Germany has scattered her men, sacrificed them on every battlefield, the pawns of the game. It is not forever she can do this. In the end it is the pawns who count."

THE woman's eyes were filled with tears.

"It is brave talk," she cried, "brave talk, my son. I shall speak to them in the village of you."

"Not of me, madame." he begged. "Look at me: I speak for what I represent. I am the common soldier of France. I am the man who bids good morning to Death, day by day, and will continue to do so until the end comes, rather than leave our beloved land to face the dread of mutilation again."

There was no sound of guns here. The train clanked across the streets of an old country town and drew up at the platform. Madame laid down her basket and embraced the Poilu.

"Son of my country," she exclaimed, "the good God guard you."

She kissed his cheeks and departed. The Poilu handed down her basket and waved his hand. He was once more gay.

"One is tempted, perhaps, to talk overmuch, monsieur," he ventured, turning to me.

"One can never say too much in the language you speak," I assured him.

He accepted more of my cigarettes, and the journey was resumed.

Presently he leaned out of the window and looked forward, shading his eyes with his hand.

"Soon," he announced, "I reach my home. For a week I shall rest. Monsieur is English?" he asked, turning suddenly toward me—not American?"

"I am English." I told him once more.

"America," he said thoughtfully, "is a great country. America has been the good friend of yourselves and of France I would not say a word which might seem lacking in courtesy and yet—there is this note which started this peace babble, the note which they say Monsieur le Président wrote.

"It has been answered," I reminded him.

"IT has been answered with great words," the Poilu assented, "and of that no more. But always this puzzles me. What did Monsieur le Président mean when in black and white he set it down as an accepted thing that Germany, that our enemies were fighting for the same cause as we—the cause of the smaller nations? Have they heard of Belgium over there, monsieur? Have they hear of the many thousands of slaves being dragged weekly from that country? Have they heard of Serbia and Montenegro? They were small countries, monsieur. Germany is very great indeed in her care for the small nations, but it is her way of caring not ours. What did he mean, do you think, monsieur?"

I shook my head.

"The ways of diplomacy are not always so easy as they may seem," I replied. "Besides, there is much which remains behind all that is said in print."

The man's attention had wandered. He was gazing ecstatically out of the window. He beckoned me to his side. About a little wood-crested slope a space had been cut. A white farm-house stood there, and nearby a few cottages and a church with a quaint tower.

"My home," he pointed out with a little catch in his throat. "You see the hills beyond, monsieur? It was there that the Boches swung round. A few more miles and I might have been homeless, wifeless—and the children..."

He stooped and picked up his haversack. His eyes were curiously bright.

"You see," he concluded, "that is why we fight: that is why the word 'peace' today stinks in our nostrils. We shall fight until France is safe."

Many thousands of American readers will recognize the name of the writer of this article as that of the author of a large number of extremely popular stories of plot and action which have been published in England and later in America. — The Editors.

HE who wrote that the "pen is mightier than the sword" lived in other times. To-day the sword is the lightning that flashes heavenwards, and the pen halts in our paralyzed fingers. Before the supreme sacrifice offered to-day by the youth of our happily joined countries, nothing else counts—is worthy of counting. Youth alone claims the immortal sacrifice made gracious and splendid by the righteousness of our cause.

What, then, can we others do? The man or woman to whom that question has not presented itself is no true citizen of the United States or Great Britain. In England the voice of conscience and duty is reinforced in a hundred different ways. Our hostels and thoroughfares are thronged with the broken and maimed of our young manhood. There are gaps in our own family circle and amid the ranks of our friends. The thunder of the guns reaches us across the narrow seas, the smell of gunpowder is in the air, many of us have gazed with our own eyes upon that far- flung line of horrible death and grim devastation. Day by day fresh instances of German savagery rise tangible and material before our eyes. We don't read of these things, we see them.

War for us is no longer an abstract and remote thing. War as the Germans have made it will remain for the rest of our lives a ghastly and unendurable nightmare.

There seems something ridiculously inadequate in the drawing out of our check-book. Yet our check-books and the valor of our fighting men will win the war.

Pardon for a moment or two the personal note. In the earlier days of the war I was induced to devote a certain portion of my time to recruiting. I worked hard and hated my job. I was all the time trying to persuade others to do what I was not doing myself. True, I was a year or two over age, but this ugly fact remained in the background, clogging speech, militating all the time against any natural gift of persuasiveness.

It's a different matter when one comes to talk about the War Loan. I am not a provident person, but, like most others, I have my savings, invested before the war in American railways. To-day, seven-eighths of them are in the War Loan. This is our chance, we others, to identify ourselves with our country. If England goes down, I go down too. I take my risk, and am thankful for the chance.

Go for your Liberty Loan in the same spirit. Tackle it before the suggestion becomes the ghostly whisper of a wasted opportunity. You don't want a man's death upon your conscience, slain because the barrage behind him became a thought slower for the want of ammunition. These aren't idle words. That very thing might happen. A Government can only provide what it can pay for. See that it never runs short.

There's your interest—good, sound, punctual. There's your security, your country's honor, and if that goes you don't want to live on among your hoardings. And you're doing your share with the boys at the front. You can look them in the face when you meet them; you can sleep soundly at night, for your money's helping.

I have not said a word to you about the justice of our cause. Wilson knows—no man better—and you trust him. But lift for a moment your eyes a little higher still. It's freedom you're helping to bring to the world —God's greatest gift to man—the most, wonderful heritage for your children and your children's children. Had money ever a greater power, a more wonderful opportunity?

Even to-day Germany is asking, Is America in earnest? Just show her.

IT is beyond my small power to comprehend the reason for the derogatory attitude of a modern world toward the modern girl. I think the modern girl is worth a dozen of her long-skirted, long-faced, pale-lipped sisters of the straitlaced strata.

I am for her. I vote for her every time. I think she is charming. I think, as you Americans say, that she is a peach, a pippin! She is piquante. She is alluring. She is more modest in her frank, self-confident way than the rather silly young female who held the center of the stage in the reign of Victoria.

Girls are just as nice today as ever they were in any period of the world's history—just as modest—and a blessed sight more sensible; more able to take care of themselves. It's asinine to go along on the assumption that women don't know anything, that they are giddy innocents. The girls of Victoria's time knew about all there was to know, I fancy, but they were guilty of a peculiar kind of hypocrisy and deception in pretending invariably to be stupidly unaware of the commonest facts of life, and of making a face over even the accidental revelation of an inch of ankle. How silly it all was!

Modesty is a grace of the soul, not an advertisement of the dressmakers. I see not the slightest reason why a girl who clips her tresses, vermillions her lips, wears her skirts to the knee, powders her pretty little nose whenever she jolly well pleases cannot be as sweetly souled as Jeanne d'Arc.

The bobbed-hair girl, lip-rouged girl that I left behind me, but that meets me here again in the New York I had not seen for eleven years, I salute her. I shall make her a heroine of mine. It may be that in my seventy-first novel she will reign supreme, a new portrait in the long gallery of the lovely ladies of my fancy. And she will not be the least lovely in that somewhat crowded gallery.

IF, indeed. it be true according to the dictum of one of our greatest thinkers, that history in its broadest sense is a species of philosophy teaching by examples, then those of us who are students of the daily press must certainly come to the conclusion that history in its narrower orbits—the day- by-day history or our own lives and the lives of our fellows—is a minor, but no less inevitable, sort of philosophy underlined and punctuated by tragedy.

The ages teach us so much in substance and so little in detail.

We are every day confronted by instances of fellow-creatures who, with the experience of remembered and forgotten worlds behind them, still attempt the impossible and pay the penalty.

It is a well-known saying among physicians that a man's physical age is the age of his arteries. Following a similar line of argument, the sentimentalist might declare that a man's capacity for married happiness might be equally determined by the elasticity of his sentimental possibilities.

There are men of 50 who might enter upon the matrimonial state with every hope and prospect of success, but these are men who, by reason of their environment or by the promptings of their natural disposition, have kept full the wells of sentiment and basked often in the sunshine of romance.

Such a man may marry as late as fifty years of age or even older—may marry even a young woman of more romantic race—and the result may yet bring happiness.

The man of fifty, indeed, who is not a celibate by choice or disposition has many advantage to offer. He is past the age of impetuous fault-finding, of expecting from his companion agreement on every point. He has learned tolerance and kindness.

He realizes, too, that in marrying a younger woman the favor of the union is with her, and it behooves him to mingle with his lover-like affection a certain tenderness which comes only from maturity, and which is possible only from age to youth.

A broad-minded appreciation of the situation upon this basis may, and sometimes does, result in the happiest of unions between people of ages apparently incompatible. But such are, without a doubt, the exception.

A French philosopher, who is somewhat of a cynic, once declared that the only really satisfactory husbands are reformed rakes or widowers. In a sense he was driving at the heart of the business.

The celibate is a man who has learned to live alone, to depend upon himself for his comforts and amusements, to do without that sympathy and companionship, the desire for which leads the normal male to matrimony.

He has had his hankerings, without a doubt, but either from policy or inclination has never yielded to them. He lives alone, and automatically, as the woman is not there, he fills his life with other and less human interests.

In proportion as those bring contentment and satisfaction, so a man passes into the narrower ways of individualism. His brain may flourish, his work, especially if it be in the main mechanical work, may even benefit, but as a gregarious person, a human being with human affections and predilections, the man himself must shrivel up.

Every year of lonely living, every year during which the man proves that he is sufficient unto himself, must lessen the possibility of his ever being able to alter the whole conditions of his existence, to eject a score of substitutes, to tear the ivy of habit from the trunk of his dally life, and to endeavor to replace it by the most radical and vital change a human being can possibly introduce into his existence.

Selfishness and habit have formed a crust around him, an armour at once of defense and self-chosen isolation.

Yet there is nothing more usual or pathetic in life than that almost passionate desire which comes to a man. especially man of intellect, in the dawn of his later days to take scrupulous and particular care that he does not miss any of the vital experiences of the life along the pathway of which his footsteps are beginning to flag.

One can imagine a certain wistfulness in the mind of the individual whose life has been given to scholarly pursuits who, deliberately finding his way into a very alien land of romance, suddenly realizes, however imperfectly and however belatedly, a new and unexpected sense of warmth and sweetness, nature tardily pointing the way toward a happiness which, after all, under such conditions, must be only a mirage.

To men of a different temperament and habitude of life a belated excursion into matrimony need not by any means spell disaster, but to be successful in such an enterprise the essayer needs to be free from the thrall of habit, to understand from actual experience something of the needs and desires of women, to be prepared, above all things, to relinquish the narrow ways of single living, to be prepared, even in middle age to step cheerfully forth into a new world, and to be led, as well as to lead, into the paths of adventure.

It is a very difficult undertaking, this. For one of those who succeed there are many who fail, there are many who day by day wear the chains of misery.

THERE are certain matters in life with which it is notoriously dangerous to interfere—crude nitroglycerine is one and the marriage laws another.

Some time ago the progressive dictator of the Turkish empire in Constantinople suddenly decreed the abolition of harem life, and probably with a tremor about his left eyelid, enunciated the doctrine of "one man, one wife." The decree scarcely seems to have given universal satisfaction. In a French newspaper we read of a wealthy merchant of Constantinople, owning a harem of 36 helpmates, who apparently received the mandate in entirely the wrong spirit. He took the unusual course of inviting the 36 to a sumptuous banquet at which he himself presided.

The press is silent,as to the means employed, but in the morning the 36 wives and their disconsolate lord and master were dead! The latter's only known comment upon the subject was that, sooner than send 36 women whom he had loved to disgrace, he preferred to obtain for them a place in Paradise. It is doubtful whether his solution was altogether satisfactory to the unfortunate ladies.

Without accepting such an episode, which sounds more like an extract from the "Arabian Nights" than a real happening, as a serious warning to us Westerners, we must still admit that from whatever point of view we study the subject there is a certain amount of danger in tampering with one of the laws upon which much of the structure of present-day society rests.

No change in the marriage ordinances, now or in fifty or a hundred years' time, which reflects prejudicially upon the spiritual or sentimental side of matrimony can be for the welfare of the human race.

Easier divorce, so freely advocated nowadays and so confidently anticipated in the future, must naturally tend to lessen the sanctity of marriage.

To take the chosen woman of your heart and soul for the remainder of your lifetime is a sacrament; to take her on probation to see how you get on would be to strip one of the world's most beautiful institutions of much of its poetry and romance.

Any emasculation of the marriage ordinance in years to come would be a retrogression toward pre-civilized ethics, would mark a deterioration in the spiritual and romantic outlook of the coming ages which it is hard to believe possible.

A very possible development in the future, however, may be a relaxation of the laws of divorce applicable only to the childless.

There have been, and still are, countries in which childlessness is looked upon as a disgrace and a fit and proper cause for an annulment of the marriage vows. Certainly a union without children can never rank in the same category as a union which has resulted in the successful operation of the laws of nature. This is where vital changes might come into effect, especially in the countries of declining birth rates.

Married people with children have given a lien to destiny. If man and wife sometimes drift apart in course of time, they must remember that they have enlarged the circle of their affections; they must endeavor to find in their children the consolation for any real or fancied lessening in the bond of sympathy between each other.

But the case of the childless presents possibilities. There seems to be no reason why, in days of increasing latiludinarianism, two people who fail to get on together, and have no one but themselves to consider, should not be given an opportunity of making a fresh start in life.

Even then, though, if the sociologist of the future should preach such a doctrine and embody it in legislation, it would only be the reincarnation of a principle accepted in various parts of the universe from the dawn of civilisation.

AFTER writing 140 books, E. Phillips Oppenheim, the British novelist, complains that diplomatic intrigue—his favorite fictional theme—isn't what it used to be. He knew the old patterns sufficiently to foresee events.

His novels, "The Mischief Maker," "Our Great Secret," and "The Makers of History" predicted the World War with almost perfect accuracy in time and the alignment of powers. Given a certain number of diplomats, of standard specifications, engaged in routine phenagling over old established punctilio, and he could figure out when the shooting would start.

But that's all over, says Mr. Oppenheim, visiting this country for the first time in ten years. Diplomats call names and tell all they know, and more, on the radio, and the laggard novelist shouts "Wait for baby!" as they touch off more deviltries than he can invent.

At the age of seventy-one, the genial, sturdy Mr. Oppenheim is one of the few writers who can man two dictaphones at once, keeping a novel racing through each of them without stopping for water or feed. Caesar could work three stenographers at once, if this reporter remembers his high school Latin correctly, but it was a lost art until Mr. Oppenheim and the late Edgar Wallace came along. There was talk of staging a dictating race between them when they both lived at Nice.

Mr. Oppenheim has been writing fifty-one years, although his first novel, "Expiation," did not appear until 1897. Previously he had published short stories. Of his 140 books, 100 have been novels and the others volumes of short stories, three omnibus works and a travel book.

He likes to have a good time during the day, swimming, golfing or flirting with Lady Luck when he's on the Riviera, and usually works from four o'clock in the afternoon until seven, during which hours he keeps the dictaphone smoking.

He never blocks out his yarns. He just starts talking, and lets the story unravel as it may.

In 1925 they rudely taxed him out of England. He took refuge on the Riviera but now lives on Guernsey Island in the British Channel.

When he was eighteen, he was flunked in mathematics and quit school to work in his father's leather business. When he visited Paris, a French café owner told him some tales of underworld intrigue, with international complications. That started his long writing marathon.

A Consolidated News Feature. WNU Service.

What you are asking us to do really is to criticise our critics, which is in a way an invidious proceeding when we think of our next novel shortly to be entrusted to their tender mercies. You might as well ask us to express our opinion of publishers as a class! If I may enter briefly into the discussion, however, waving a white flag and deprecating recrimination, I should say that the practical value of criticism to an author is scarcely so great to-day as some fifteen or twenty years ago. The reading public nowadays have formed their own ideas as to what they like and what they don't like, and in these times of universal novel-reading are not so easily influenced. I am not sure that I should not consider the good will of the principal librarians as important an asset to an author to-day as the best press notices a novel could receive.

At the same time, apart from the influence of kindly or destructive criticism upon the public, there is also the author himself to be considered. A favourable and appreciative notice of his work is often an inspiration to the writer, whereas those few sarcastic lines, which a short time ago were rather the fashion amongst a certain type of reviewer, although they may do him little harm with the public, are often unduly depressing to their sensitive victim. Disraeli has told us that the ranks of critics are recruited from those who have failed in their own attempts at creative work. That was probably true about a century ago, and may easily have accounted for a certain virulence, happily absent from the pens of most modern reviewers. The vogue of deliberately destructive criticism is certainly on the wane. Where a periodical of repute thinks well to give a lengthy notice to a work of fiction, it is nearly always appreciative and encouraging.

If one were to seek to find fault with the English reviewer, one's complaint might be that he is too apt, having read one or two, say of X's novels, to take up a further volume by the same author, and believe that he knows all about it before he has read half a dozen page. Any variation of theme or treatment is lost upon him. It is an "X" book, it is to be put in the "X" category of merit or demerit, and where you started in the estimation of that particular reviewer, there you will remain to the end of your days. The last criticism I saw of one of my own novels came to me from an American newspaper two days ago, in connection with which I should perhaps explain that, owing to unusual circumstances, it happened to be the third during the year. The notice was terse, and there was a finality about it which amounted to genius. It ran as follows:

Prodigals of Monte Carlo,"

by E. Phillips Oppenheim.

Another OPPENHEIM! Gee!!"

LAST Sunday morning I found the village postmaster and grocer loitering in the fields around my house, heedless of the church bells.

"What's the meaning of this, Morris?" I asked. "Who's going to pass the plate this morning?"

"I fancy there'll be someone to look after that, sir, he replied, with a faint smile. "I am not feeling exactly like service today."

"How's that," I enquired.

He hesitated for a moment. Perhaps the fact that I was a wanderer myself encouraged him to proceed.

"I don't know how it seems to you, sir," he confided, "but I can't stand the service at church these days."

"The village folk round about here, sir," he went on, "do make me sometimes wish that just one single hamlet hereabouts might be treated as scores in Belgium and France have been. You can't get through their hides; you can't make them understand the terrors that are so nigh to us. They go on in the same old way, and, begging your pardon, sir, it's the same with the Church service."

"There's a roll of honor in the porch, and a prayer for the King, and a kind of litany for those suffering in the war, and at best a few words from the parson as to our great fight for civilization. And that's all. It's a long way off, sir. It's mainly the same old service that I listened to gladly in the days of peace, but there seems something wrong with it now. What's the use of talking about love and charity when millions of our fellow-creatures are sweating and fighting, striving to tear the life out of one another like wild animals? One feels that the Sunday newspapers the boy will bring over on his bicycle in an hour or so are flaming contradiction of everything we hear in there," he added, with a jerk of his head towards the church.

Morris is in his way, a thinker and a man of feeling. Besides, I was in sympathy with him.

"Tell me, how would you have it altered?" I enquired.

"Well, sir," he said, "I am not a travelled man nor a great reader, but it seems to me that everything in this country has changed to fit in with the war, except the Church, and I don't see how the Church can expect to hold its own unless it makes a sight better effort then it's made up till now. It's the Church at home I mean, sir," he went on earnestly. "No one has anything but praise for those young parsons that have turned themselves into chaplains and even fighting men."

"What could the Church do that would draw you back, Morris?" I asked.

"It's a hazy sort of idea, mine, sir," he answered apologetically, "but it comes to me sometimes whether the War Office, say every Friday night, couldn't draw up an account of the Week's fighting that was just trustworthy and distribute it through all the churches in the country, so that on Sunday, instead of a sermon about someone in the Old Testament which we can't sort of fasten our minds on in these times, or words about love and charity which sound like moonshine, the parson could up and tell us just how things stand--things that we want to hear about. There's newspapers, that's true, but it isn't all of us who read them, and something authoritative coming from the pulpit, which might become part of our church-going--well, it'd seem more human, somehow, sir. It'd bring the Church once more nearer to our daily life and thoughts."

The church bell had ceased. We heard the voices of the children singing one of the old familiar hymns.

"It's just an idea of mine, sir," Morris said, as he turned to pursue his lonely walk.

Crimes Weird, Morbid, and Matter-of-Fact—

How Murderers are Made and Missed—

Some Interesting Observations on World-Crime Experiences

WHY do we like to read about crime?

If any individual is qualified to answer the question which forms the subject of this article, it should be E. Phillips Oppenheim. A profound student of crime from the age (as he now reveals) of eighteen, Mr. Oppenheim is to-day perhaps the best-known writer in the English language in his own particular field. He has held the attention of millions of readers in his swift and convincing stories of crime. He should be exceptionally conversant, therefore, with the factors which cause the crime news in the daily papers to be so steadily and widely read.

THE study of crime is my business. A correct analysis of the motive behind any possible deed of violence, an analysis gauging its strength and its breaking point, must be one of the equipments of the sensational novelist. Your stories won't ring true unless they might have happened.

For that reason I am interested professionally in only one crime—the murder or the robbery with violence—that could happen to or that could be committed by almost any average person under a give set of circumstances. The arch-murderer on the rampage leaves me cold. The crime which provides me with food for study is the crime which potentially or vicariously concerns a bank manager and his family in Liverpool, a retired schoolmaster at Brighton, the hard-working young proprietor of a garage just off the Grade Concourse in the Bronx and a high school senior in Vancouver, or a clerk in the Santa Fe railroad offices in Kansas City.

Plausibility is what I want and to attain that I need for my characters, however amazing their subsequent adventures may be, men or women whom one might meet at any hour of the day. It is only when the reader actually feels that he himself might have been in the place of one of the principal characters that you are sure of his attention.

PRECISELY the same reasoning holds good as regards the interest or lack of interest of the public in any of the great murder trials of today. The newspaper reader declines to be very much interested in the knifing of half a dozen Canton coolies by one another, nor is he very much concerned when two professional gun men shoot one another to death in the back of a low dive. These people do not come within the day-by-day sphere of our interests. But when a business or professional man in our own walk of life enters the offices of a broker and shoots him to avenge his own ruin, or gets up in a music-hall of which we ourselves are patrons and shoots another man because he is there with his wife, then the thing comes home to us.

Our interest is excited and our senses are kindled, for the simple reason that, victor or victim, the thing might have happened to us. This is the inner meaning of plausibility, to the understanding of which you can only attain by an intensive study of human nature under varying conditions. If you write about crime, you must be able to trace the mental process that led up to it.

The fascination of such a study grows as also do its dangers. In any modern criminal case—say a murder trial—the student is compelled to start at the wrong end. He has to start with the climax, namely, the murder itself, and go backwards through a maze of attendant circumstances to the fully-developed motive, thence to its inception and finally to the primary idea. An interesting study in a way, but rather like reading a novel backwards. The psychologist may gain something, but not the story-writer.

THE real enticement of the time for the latter comes in when you can fix on a man or a woman whom you know, draw around him a web of circumstance, and decide from a close and eager study of his character and tendencies exactly the amount of aggravation or temptation which will lead him to commit any given crime.

This isn't really difficult. Human nature, notwithstanding its variations, is reduced to a common denomination with amazing facility. Given a close enough study of the individual, it is possible to make almost an exact calculation of his attitude towards the commission of any certain crime under any given chain of circumstances.

There is a man of my acquaintance at the present moment who I am perfectly certain would commit a murder to-morrow if he had the courage. The desire is there.

ALSO the slight and poisonous vein of morbidness which lends a lurid fascination to the perpetration of the horrible. All that he needs is the courage. Circumstances may at any day supply this.

My first personal association with crime was when, at the age of 18, I was spending a few months on Exmoor—the loneliest part of England. In the next cottage—half a mile away—lived a shepherd, his wife and three children. The shepherd—Abraham Rodd, his name—was a man of excellent character, honest, industrious, religious, a faithful husband and an affectionate father. His wife had in her a strain of gipsy blood. I used to see her sometimes across the Combe, as the Devonshire ravines are called, hanging out clothes at the back of her cottage, her black hair streaming in the wind always wild-looking and seemingly affected with a queer sort of restlessness, an odd mate for a yokel.

ONE night, when Rodd was out with his sheep, an unexpected snow storm came on. He drove his flock into shelter and made his own way home. In the evidence which was subsequently offered at the inquest and the Assizes, it seems that after his entrance into the cottage he stood for minutes like a man turned to stone without a word of anger or reproach. Afterwards he took his wife's visitor—a travelling tinker of her own blood—outside and beat him to death. It was 38 years ago, when the law was in a sense more obdurate, and notwithstanding the provocation, he was sentenced to death and hanged.

I never spoke to him myself after his conviction, but I talked often with the clergyman who went to see him. He was never afraid. He never for a moment regretted what he had done. His attitude in his cell and on the scaffold was simply one of intense, pathetic surprise. He couldn't understand how any man could have done other than what he did, or why he had merited death for it. He died wondering.

It was this episode in real life which led me seriously to consider the psychology of crime. There are, of course, an infinite number of subdivisions, but broadly speaking, all infractions of the law can be regarded from two points of view.

FIRST, then, there is the evil deed—we will take murder as being the premier crime—committed by the habitual criminal who is devoid of any sense of moral restraint, whose wrong-doing is a matter of calculation, proceeding either from, cupidity, sheer lust for blood owing to moral degeneration, or for the purpose of closing forever the lips of one who might give evidence against him.

Such men or women are the mental invalids of the world. They are probably born with an inherited tendency towards crime. They gravitate into an environment which aggravates their criminal proclivities, and if they end their days in prison without expiating their crimes upon the scaffold, it is probably because the circumstances pointing to a successful commission of murder have never presented themselves. The activities of this order of being have increased since the war, possibly because since those days of wholesale slaughter the value and sanctity of human life have fallen in the scale.

Why is this barbarous crime of robbery coupled with ruthless murder more prevalent to-day in the United States than in England? Certainly not, I imagine, because the standard of morality varies in the two nations, but chiefly for diverse and material reasons. In the first place the risk of capture is less in the former country. It is not that the detective systems are not equal—as a matter of fact, I think the American to be superior—but there are other considerations.

OUR country is so small and our passport system so rigid, that it is an easy matter to watch our ports and although politically we may seem to the world sometimes to resemble a nation of idiots our Courts of Justice are above all suspicion and the law is administered without the slightest regard to the social position or wealth of the criminal. Witnesses, too can be brought from any part of the Dominions, and the laws under which justice is administered, which, except for variation in the penalties, have been practically unchanged since the days of the Magna Charta are the same all over the Empire.

In America you have the varying laws in different States to contend with and the occasional introduction of political influence into a case where the connections of the accused can command it.

The American race of to-day has attained homogeneity and an individuality, recognised the world over. The country's ports, however, are still open, although to a restricted degree, to a constant stream of immigrants anxious to share in her prosperity. Naturally enough, this leaven of hot-blooded denizens of Eastern European countries, many of them newly arrived in the country, makes for a larger percentage of crime.

A STRANGER who has not yet settled down into his surroundings, who has not the goodwill of friends, and a social position, however humble, is far more likely to yield to the impulse of committing an illegal action than a person leading a settled life among friends, and neighbors, whose good opinion must unconsciously influence him. It is generally the alien and the wanderer who braves the penalties of the law, rather than the householder and taxpayer, even when the element of character does not present itself.

But this habitual criminal, this person who commits crime as a matter of business or through sheer moral degeneration, is of very little practical use to the novelist. No one wants to read about him and he makes no general appeal. The works of Dickens, would have been just as readable without Bill Sykes, and the vivid gifts of Eugene Sue might have been far better employed than in presenting a series of powerful but horrible pictures of the mechanical puppets of sin. The novelist in his eager probing of life in search of material is attracted wholly and entirely by the second class of criminal, namely, the man or woman who commits an offence against society through lack of restraint. This is the man worth talking about, worth studying, worth analysing.

Abraham Rodd was a very simple example of this class. He hadn't a criminal instinct in his nature. He was without the slightest predisposition towards crime. He loved his wife and children, he loved his fellow human beings, he loved godly living. Yet Abraham Rodd committed the greatest crime in the catalogue of crimes through lack of restraint, and suffered the extreme penalty. He was the victim of a code which exists for the benefit of the majority, and from which the minority must suffer. He perpetuated what he considered, and what undoubtedly was, an act of justice. Unfortunately for him, the law says that a civilised country can only continue to exist as such if the law alone metes out punishment and the individual bares his back to the stripe.

LOGICAL, all this, no doubt, but the worst of it is that our subconscious sense of justice may sometimes lead us to take the law into our own hands only to find that law and justice, for the benefit of the community perhaps, do not run on parallel lines. You kill me because I have seduced your wife—murder! I kill you because I desire your wife—Murder. Thirty years ago we should most certainly both have been hung, although I should have deserved it and you would not. To-day, although you would probably escape with penal servitude, the distinction between our crimes is not legally recognised.

In its way, however, the argument of the lawmaker is unassailable. A community must be governed by standardised statutes and not by the standard of a variable human intelligence subject at all times to variation of influence. The moment that the registered penalties for crime were removed or made more elastic and punishment was administered from a human sense of justice only, whether by judge or jury, the moral state of the community might perhaps show no signs of deterioration, but the perpetration of crime would without a doubt increase in every direction. Fixed laws are the only practical deterrent.

Abraham Rodd, always the prototype in my mind of the innocent criminal, must suffer that the community may gain in freedom and security.

E. Phillips Oppenheim Still Enjoys Living and

Writing After Many Long, Busy Years of Both

Author of 140 Book Containing Ten Million Words Keeps

His Zest for Everything From Roulette to Attractive Women

STAGGERING facts about E. Phillips Oppenheim: Some hundred and forty books (just a little matter of 10,000,000 words), a fifty-year career, more active today than when it was born, a yacht that looks like a honey, a pivoting summer house, a tower from which to watch storms off the Guernsey cliffs, and on and on.

As to Mr. Oppenheim himself, now past seventy, an appetite for living that is even more staggering.

ROULETTE. He loves it. Nobody knows exactly how many years he has played or how many hundreds of Monte Carlo scenes his readers have been let in on. Or how sensational some of his winnings have been. Always he has stuck to the same numbers. Seven-fourteen-twenty-nine, played, I think you say it, with chevaux.

HEAVY SEAS. His tall, slender Irish secretary. Helen Symes, for some crazy reason called "Tiny," described a recent trip from Saint-Malo to the Isle of Guernsey on the Echo, Oppenheim's eighty-ton yacht. Rolling and tossing all the way, she said, turned all on board green in the face, all, that is, except the owner. The rougher the seas the hungrier "Mr. Opp" got.

FISHING. The Echo has a crew of five, including Mr. Oppenheim, who said he was usually to be found at the wheel. He recalled one thrilling day when he caught 170 mackerel and then nearly got shipwrecked. Seas were too heavy to get home, so the captain turned to broiling mackerel. "And a surprisingly good cook he turned out to be," said Mr. Oppenheim. "We kept him at it all night."

WRITING. Miss Symes is sure that when we are all dead "Mr. Opp" will be plugging right along, dictating six or seven hours every day. "I love writing" he explained, "love to think about the things I mean to write, then to dream of them at night. Going to bed early, lying out on the piazza, adding a little bit here and a little bit there to the story you're going to write the next day! Jamaica, where I've just been, is the most isolated, most charming spot in the world to write in—coconut palms, nutmeg trees, richly-flowering shrubs, and below you, far, far below, the bluest water in the world, so blue that it's sometimes green."

READING. E Phillips Oppenheim reads little contemporary fiction. He becomes, he said, either discouraged about his own writing or fearful that he will imitate. P. G. Wodehouse. however, one of his oldest friends, he reads, as he did the late Edgar Wallace. Wallace and he worked entirely different gold fields and as to Wodehouse, well, nobody could imitate him. Poetry he loves. Browning, Shelley. Swinburne and Tennyson. "'Now," said he, "I will make myself really unfashionable. I love the rhythm of 'Maude' and I can still get sentimental over 'Locksley Hall.'"

"PEOPLE AND PICTURES, however, give me more thrills. Pictures are my hobby, and whenever I went a complete change I go to Florence, which is entirely different somehow from going to an English gallery. I haven't collected pictures because the ones I like are priceless; only rich Americans can afford to take them away from galleries But on a quiet day in a gallery in Florence I can be content; there I find the real spirit of the Renaissance."

MONEY. "Of course I've made money, lots of it, but I've spent almost as much. And just because I like poetry and pictures, don't put me down as an aesthete. I like all sorts of worldly things, the best restaurants, the best food, the best-dressed women. But it costs to live, costs me as much to poke about in the slums of Continental Europe as it does to live in the Ritzes of the European capitals. One always spends in life if you expect to get anything out of it, and that goes for love as well as money. You can't, you know, receive all the time."

VIOLENCE. Not even Mr. Oppenheim knows how great a vicarious bluebeard he is. He admits there is some truth in the legend that the first thriller he wrote found all his characters killed off when the book was only half finished so that a whole new set had to be invented; but today, he affirms, after all his experience, his killings are always neat, always well swept up after. He prefers his violence well-seasoned with tenderness

LIFE. "Life's an adventure if you treat your days carefully. Keep your thoughts in order, your mind fixed on something worth-while, because incidents prove so small a part of life, really. I used to think adventure meant going about the slums of Marseilles with a semi-detective and with a gun in my pocket, but I know now that you—and It doesn't matter where you are in the world—make your own adventures. Life's a thrill, a great thrill. We just don't realize how much we are the masters all the time."

AND LADIES. "American women are so charming, and parties, too, are nice, nicer than they were when I was in New York ten years ago. Prohibition was raging then and it was all rather sloppy, having to do your drinking under the table. And ladies, not necessarily beautiful but attractive! Ah! Nothing in the world can touch the right light in the right eyes.

Mr. Oppenheim, in America with his wife and nobody knows how large an entourage, was one of the guests of honor at the centennial dinner given by his publisher, Little, Brown, in Boston on Wednesday. His 100th novel, "The Dumb Gods Speak," was published recently and the 101st is even now off the fire. It will be called "The Man Underneath."

Mr. Oppenheim. back at the Ritz Carlton in New York this weekend, sails for London on Monday.

NEW YORK. Feb. 22. — The greatest thing that has happened to America in the past 11 years has been the coming of golf.

It has always been an Englishman's weakness—and now the American has fallen for it, too. It is most encouraging.

When I was here in 1911 I went begging for a game. I couldn't get a partner. Everyone was too busy at his office. Late Saturday afternoon, or Sunday, I sometimes found a player. During the week—never!

It seems that the American has learned the trick of mixing business with his game. He's ready to run off to the links 'most any time. If the weather permitted, I probably would be playing now—with some extremely busy business man, who would want to go around the course in a hurry.

It is characteristic of the American—doing everything quickly.

Your young man can't wait to grow up before he goes in some business. If he does not like it, he gets out just as quickly and starts over again.

In England, he is much more sedate. He takes his time, thinks it over, and then decides on some course. If, perchance, it proves unsuccessful, the young man feels that he must pull up his stakes for life. Over here he thinks nothing of changing his occupation until he meets with success.

Even your flapper here has more ambition than her sister. She has the air of wanting to face the world with unclasped galoshes. She is a charming thing!

I honestly think that the American girl of 20 is the most attractive person in the world. She knows just enough—not too much—and her manners are delightful.

As a result of this speeding up at home, in business and even at his game, the American business man retires early. I have met him many times traveling abroad taking it easy at the age of 38 or 40!

The Englishman never retires. He takes it easy all the time.

Who gets the most out of life?

I don't know. But sometimes I think that we miss part of the fun by our lack of your ambitious hammer-and-tong method of beating out the future.

We get there just the same, however—a little later.

There is one marked difference that I have noticed in the women—the American wears her clothes better. She is a little egotistical, while the Englishwoman likes to be dominated.

But here—

If I go on talking this way, you will think that I'm lecturing—and that is something I never do.

When a writer tries to deliver a lecture, it is usually 50 per cent curiosity on part of the audience and 50 per cent platitudes on part of the lecturer. A writing man—or woman—should stick to the pen.

But there is one thing I want to tell you—

The American customs officials have become polite.

I never met with such courtesy before. It was almost shocking.

LARGE numbers of people have noted the fact that in certain of my earlier novels I prophesied wars and world events that actually did come to pass. In "The Mysterious Mr. Sabin," I pictured the South African Boer War seven years before it occurred. In "The Mischief Maker," "The Great Secret," and "The Maker of History," I based plots upon the German menace and the great war that actually did occur. And in my forthcoming novel, "The Great Prince Shan," I have tried to picture the consequences that would result if Great Britain abolished her international secret service, her army and navy, and relied on some form of a League of Nations solely for protection and peace. First of all, it must be understood that what I write is done absolutely from the standpoint of fiction. My plots are necessarily distorted in order to drive my themes home. But I try to put more into the books than romance. Plausibility is one of the things I aim at. Indeed, I think that no novel can stand sturdily upon its own legs unless it possesses sufficient plausibility to make the theme possible in actual life.