RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

Credit and thanks for making this work available to RGL go to Gary Meller, Florida, who donated the scanned images of his print edition of "The Quest for Winter Sunshine" used to produce this e-book.

"The Quest for Winter Sunshine," Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1927

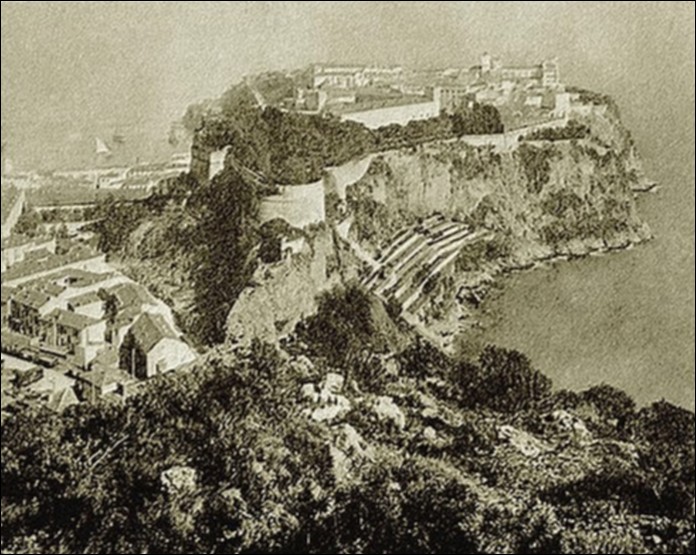

Frontispiece

Monaco

EVERY age sees the revival of some form of actual or mythological belief, translated into modern standards and adapted to modern needs. The sun-worshipper of thousands of years ago, devotees of a very logical form of it religion, have their descendants to-day in the light-hearted crowds who, with golf clubs and tennis rackets in their kit, fill the Blue Train and join in the general exodus from the grey northern winters of Great Britain to the sunnier southern lands. It is a recent but irresistible impulse. The coal fires of the country houses and the steam heating of the cities may warm the body, but the mentality of to-day seems to become numb and frozen by week after week of lowering skies and grey mists hovering over a rain-sodden land. The call to the South becomes like the whisper of the west wind to the swallows. We book our seats for our chosen destination, and the Paris-Lyon-Mediterranean train does the rest.

Nothing in the records of our immediate ancestors gives any indication of their having shared that almost feverish desire for sunshine with which the whole world now seems to be suddenly inspired. The Continental trips of bygone days were undertaken more as a tribute to the fetish of fashion and for the purposes of some education in the gentler arts than from any genuine desire to escape from the rigours of a climate too uncomfortable to be willingly endured. The chronicles of those days treat eloquently of the picturesqueness of the old towns of France, the fascination of the boulevards, the elegance of the Parisiennes, but allude very seldom to the climate. To-day one seems content to take all those other things for granted, and to spread one's wings southwards for one purpose, and one purpose only. There is, as a matter of fact, an age-suppressed revolt against the depressing influence of our long, sunless winters, which seems to be spreading not only amongst the wealthy, but amongst all classes of society. The winter Continental traffic has increased by leaps and bounds, until it has become an amazing thing. The cross-Channel steamers are invariably overcrowded; it is necessary to book seats in the trains weeks, and even months, beforehand. The cynic might seek to account for the annually increasing exodus of sun-seeking pilgrims by the falling franc or lira. This, perhaps, may sometimes be a deciding factor to people of moderate means, but personally I have come to the conclusion that a certain change in the Anglo-Saxon temperament, evidenced to-day in their literary and artistic efforts, is also partially responsible.

Life has become more frivolous and less pompous. There exists a desire amongst all classes, worn out by a ceaseless struggle against difficult conditions, for a more gracious and easier passage towards their latter days. It is not only the physical craving for sunlight and softer airs, blue skies and the music of gently-lapping waters which draws us southwards, but also an unacknowledged, gently stirring desire for life under less severe conditions, for some degree of slackening in the more rigorous code of existence which seems to prevail under our grey and fog-depressed skies. Certainly the farther north one travels, the more austere becomes the creed of life. Calvinism had its home in Scotland, where Sunday closing is still in force, and the joyless spectre of prohibition is always in the offing. The more picturesque religion and less rigid standards of the Latin countries—countries of sunshine and ease—make to-day an irresistible appeal to a nation a little weary of its own sterner but more hypocritical attitude towards life.

Who is not weary of that grandmotherly legislation which decides when we may or may not buy a box of chocolates or cigarettes, and the exact hour at which our glass of wine— sometimes after a hard day's work—is snatched away from us; weary, too, of that school of politicians who have made their country an almost impossible place for the average citizen who objects to spending his remaining years in a state of semi-starvation for the sake of the unborn generation? Where the warmth of the sun is more generous, gentler principles of life prevail, and a far more intelligent system of national thought.

"My people of to-day must live," Mussolini is reported to have lately said, when he swept away with indignation some proposals for additional taxation. Uninspired by the vanity of a spurious patriotism, the rulers of Italy are content, as are also the rulers of France, to let their people dwell peacefully and happily in the sunshine of a temporal and actual prosperity, rather than bleed them to death for the shadowy, academic satisfaction of watching those poor, harassed phantoms of financial status—the franc and the lira—-mount on a pyramid of human misery to an artificial value.

Nothing to do with this matter of sunshine? I am not so sure. The more one wanders in countries which warm the heart as well as the body, the more one realises the analogy of kindlier feelings, the greater latitudinarianism of thought, which thrive under gentler atmospheric conditions.

Currency is rather a ridiculous fetish. The French and Italians alike, with equal blandness, equal candour, but with all their national graciousness, make very clear to us, sun-seeking sojourners amongst them, the fact that as the franc or lira rises to higher figures, so does the cost of our daily life. So also seems to increase their very sensible lack of desire for importing luxuries on an adverse exchange, and so also develops their inventive genius concentrated upon the task of making for themselves at home those goods and that merchandise they have been accustomed to buy in foreign countries. From the point of view of our politicians, France is no doubt in a parlous financial state; actually she is prospering as she has not prospered for centuries. The standard of living amongst the middle classes and poor is higher than it has ever been—far higher than our own to-day. Her industries are everywhere flourishing; she is absolutely without unemployed. Here are figures which give one to think. The precise number of men, women and children capable of work and unemployed last week (July, 1936) amounted in the official statistics to nine hundred and sixty-eight. If it is the chief duty of a statesman to keep his people happy and contented, then the much-derided statesmen of France could show our fellows a thing or two!

But about that matter of sunshine!

THE Intelligent seeker after sunshine learns very soon that there are many degrees and qualities this greatest gift of the Unknown. There is tropical sunshine, of which I know very little and desire to know less. In its intensity it is inclined to be pitiless. Never can one bask, happy and relaxed, and feel the joy of it creep through one's veins. It dries up the earth, burns the life and energy out of man, draws strange and scentless flowers from a parched and crumbling earth. One may watch with wonder its slow birth on the far horizon of an oily sea, or a waste of desert, but at the end of the day one breathes a sigh of relief at the sinking below the sky-line of its blood-red heart. It is like the passionate goddess of mythology who gives too fiercely and too much.

It is not the sun of which we pilgrims are in search, The full sweetness of her lies nearer home—in Algeciras, perhaps, and all that pleasant Mediterranean-girt country between Toulon and Alassio. She is at her kindest, too, in Sicily; her moods in Egypt are sometimes glorious.

Algiers basks often in her full favour, but there are times here when she reminds one of her desert cruelty, and we, her worshipping children, must creep beneath a roof and pray for the night. Then, as though in a fit of pique, she gives way to rain—grey, pitiless rain, bringing with it a chill reminiscence of home, and a dreariness of spirit which sends us hastening to Cook's for a list of steamers.

Algiers, the Promenade

Algiers to me always seems not entirely one thing or the other. There is something a little spurious about its Africanism, some quality of hardness in its sunshine, exhausting rather than recuperative. Her mid-day fierceness draws strange spicy odours from those bales of merchandise upon the wharves, from the wine vats, the olive casks and the orange-barrels, and less savoury reminders of her puissance from the piled-up goat skins in the warehouses behind. Even her own children shrink from her sometimes for hours at a time, and lie huddled up against the walls, under a wagon, or wherever shade is to be found.

The sunshine which I like best is the sunshine which brings scented flowers from a not too parched earth, which leaves the perfume in the flowering orange trees, the song in the throat of the bird; which for long hours warms you in her kindly embrace, and which drives you only for a brief space of time into refuge, to creep out again as soon as she begins to sink ever so slightly towards her western home.

The sunshine of my fancy must have a note of gentleness even in her least tempered heat. She may, perhaps, in her moods, be a trifle capricious at times, hide for a day or more, but only to come back with a freshness and sweetness which seems to make amends for her absence. There must be a note of that elusiveness about her which we love in our womenkind, so that, even when she leaves us for an hour or so, we have always with us a sense of her nearness, a feeling that she is there for our comfort and delight, and that at any moment the joy of her may pass once more into our body.

The sunshine of northern Africa is not the sunshine with which one would wish to live. It is too fierce, and at the same time too fitful.

One has to remember, however, that this business of seeking for warmth is no personal matter, and Algiers, with its mingled Gallic and African atmosphere, possesses, without a doubt, an unanalysable attraction, especially when one is fresh from the sombre skies and gloomier life of our own country. The streets are full of colour and life. The burnous-clad Arab brings, at any rate, a picturesque reminder that we are on the borderland of desert life, although he seems strangely out of the setting, loitering along the pavements and gazing into the windows of the very modern shops. The dusky-faced mendicants of the back-streets are more convincing indications of the fact that we have passed on to another continent. There are hotels to be found of every class, a few pensions and many villas now being built. Living here, however, is certainly not cheap, and the domestic service problem is almost insoluble. On the whole I should look upon Algiers as a delightful spot for the casual wanderer, or as a stepping-off place for the tourist on his way to the desert, but for any one seeking a more or less permanent place of abode scarcely to be taken seriously into account unless the lure of Orientalism is strong enough in the blood to outweigh minor considerations.

Let me be fair, in passing, obstinate Briton that I am, to the scant sunshine of my own country. There are times when one can absorb the joy of her in one's Norfolk garden, or wherever else in England one may chance to be, and nothing in the world seems more beautiful than the freshness she brings with her warmth, the soft exhilaration which comes with the joy of her. But, alas, in the full height of one's brief spell of happiness, up drift the clouds. On the morrow there is rain, the next day a grey sky, soggy turf, and dripping flowers; on the next a lew gleams of that unhappy solar deity struggling to force her way through sullen banks of mist, gleams which bring no warmth to the body, and only tantalise; on the fifth or sixth day she may come again, but by that time one's heart is a little sick.

Occasional elusiveness is a quality delightful enough, but with our English sun it is, alas, not a question of furtiveness but a question of hiding altogether. When our mistress sulks for too long, we lose heart, however great her charm. A land may be sunless, and its children remain a moral, law-abiding race, but there is a quality of happiness which they can never know.

"Ah, but so much sunshine," a neighbour of mine from the mist-bound eastern county which I still call home, remarked recently, "produces a lethargy, makes the people idle. The Latin races don't know what work means."

In my younger days I might have had the same idea; now I know better. So far from the sun developing the spirit of idleness amongst her children, it is my belief that she acts upon them as a veritable tonic. I have spent the greater part of the last five years near a small town in the south of France. I have employed work people there, I have watched the mechanics, talked to my entrepreneur, observed the springing into life not many miles away of an entirely new settlement.

I consider that the French workman works longer hours, and takes a keener interest in his job, than the British working man of to-day. The tradespeople keep their shops open later, and are to be found always behind their counters, and not at the neighbouring cafés. To observe the methods of a Frenchman who is out on business in one of the big towns is an education; to hear him talk of commerce with a possible buyer or vendor is a study in alertness. An American businessman is slow compared with a Frenchman, when the latter gets going. The tradesmen, merchants and mechanics of these southern towns, from Lyon to Marseilles, and round to Nice—which few people realise is in itself a great commercial centre—are as keen and hard-working all the lime as though the success of their lives depended upon their efforts during that one particular day. They not only work for longer hours than the English, but they usually work for the whole day on Saturday; and sport, except on a Sunday, is a thing which does not concern them. It is true that a few troublesome fête days sometimes upset one's plans, but I have never yet met a Frenchman who wasn't eager to give up his holiday and work instead, for a consideration.

In some parts of southern Italy, perhaps, my friend might find some justification for his criticism—not even there, though, amongst the tradesmen or the merchants, but amongst the labouring classes. I watched a gang of a hundred men repairing a tramway line in Naples a few weeks ago, and I must admit that their efforts were languorous. They reminded one of the disgusted comment of an American foreman who was sent a gang of fifty newly arrived Neapolitans to work under him. "And these are the . . . they make Popes of!" he exclaimed, after watching them for a short time in despair.

In northern Italy, though, and in all the great commercial centres, the operatives in the factories arc at least equal to our own in productive capacity, and the businessmen themselves equal to any in the world in enterprise and industry. Curiously enough, an Italian friend with whom I was talking the other day blamed them for their superabundant caution—a quality not usually associated in our minds with the Latin races. But, after all, nine tenths of our flamboyantly given opinions about the Latin races on based on ancient prejudices, and with us nothing dies so hard.

No one who has spent any time in their county, though, could ever describe the Sicilians as a lazy race. The peasant-farmer, hard-working, industrious, rises with his beloved sun, and as often as not retires with its last lingering beams. His land is always in good shape, his vines carefullly pruned, his lemon-groves neatly enclosed, he himself frugal in habits and a downright honest toiler. He is one of the sun's children, and the sun has brought him nothing but good.

ONE recent day in February, I lay at ease high up on one of the grass-grown tiers of the ruined amphitheatre above Taormina, with the faint perfume of the wild thyme sweetening the air, and a vista of the ancient town, with the blue sea below, framed in one of the tottering grey arches before my eyes—and the February sun warmed me, body and soul. The sunshine of Italy is a golden and a wonderful thing. Inland, as far as one can see, it has brought to yellowing magnificence the myriads of lemons with which every tree seems laden; to a deeper golden the rough- skinned, luscious oranges; has painted the faces of its children that rich olive brown which no sunburn specialist has ever succeeded in imitating for the benefit of cinema actors or week-end chorus girls; and, even in places where only its morning warmth can penetrate, has brought to early blossom the luxuriantly growing Bougainvilleas.

Taormina, the Ruins and Mt. Aetna.

It has drawn from the earth the deep-coloured violets, strong in the stalk, perfumed, with that faint touch of purple in the colouring which distinguishes them from the violets of northern latitudes. Already, so early in the year, there is blossom upon the peach trees, and the carefully-pruned vines, stark and still, seem to be feeling the sap of life in their gnarled interiors.

Away, over the peak of Aetna, are slowly-moving masses of cumulous, pearly grey clouds. One may watch them pass, and gain occasional glimpses behind of the deep spaces where the sun has melted a ravine of snow, to send a flood of ice-cold water hurtling downwards into the joyous warmth of the blue sea below.

The early sunshine of Italy has heaven-like qualities as it pours down upon the glad earth a living stream of gentle fire—never, in these days of early spring, with a single touch of that fierceness which drives one later into the shadowy places. It helps one to pass with light footsteps along the flag-stoned main street, whose picturesque charm survives even its suggestions of the tourists' paradise. The tall, grey buildings, on the ground floor of which are the little shops with their almost too flamboyant offerings, are cleft here and there with unexpected gaps, through which are glimpses upwards of flights of worn steps, leading perhaps to a court of ancient but grimy houses, or, by better luck, to a church, with its shrine and cross and hospitable, wide- flung doors. Looking downwards, there are still more wonderful vistas—the yellow-dusted tops of a grove of lemon trees, the flowery intervention of a peach orchard, a grey- fronted villa, red-roofed and smothered with Bougainvilleas or clematis, a chasm of blue untroubled sea below.

Commercialism is a little flagrant in this fascinating thoroughfare, triumphant though must always remain its architectural charm. It is not the free gold of the sunshine, it is the trade gold of the world for which the Sicilian's hands are anxiously extended, and in which he takes his pleasure. Manifold indeed are his wares—antiques, modern scarves of silk, designed after Oriental fashion, needlework in plenty which pleases, with a curious admixture of the necessities of modern life—American-made boots and shoes, English tweed caps, French drugs, and Italian tortoise-shell. The genuine antiques are mostly little fragments of figures or shrines from the old churches, collected one would scarcely wish to ask how, and brought in from those mountain hamlets more often than not at the bottom of a wooden box or sack of vegetables. They have their charm, these relics, wrenched, some of them, from the whitewashed walls of a wind-swept ancient church, built high up in the hills, from whose proximity the little congregation of worshiper has dwindled away to seek a more sheltered and more favourable neighbourhood on the slopes of the valley. Here they have planted lemon trees, a few vines, a few square yards of maize, and reared laboriously a new habitation, so that only the stark walls of their former dwellings remain, as though destroyed long ago by fire—a state of ruin to which in time the church also attains.

These deserted hamlets are no indication of any falling away in the population, or any lack of enterprise in their efforts towards self-support. They simply mean that a more practical generation, finding a wider market for the fruits of their husbandry, and no longer in fear of predatory attacks from their neighbours, have moved downwards towards the richer soil.

There is an oil painting hanging in state in one of the more pretentious of the shops, reputed to have been the altarpiece at a famous monastery, and the name of one of the greatest of the Italian masters is hinted at mysteriously by the judiciously reticent salesman. Such treasures, however, are not for the casual wanderer, even if they should chance to attract, so you pass on, and with the ending of the narrow street comes a richer flood of yellow sunshine, some of which you have lost in the narrow spaces. It is almost as though you have stepped out of a tunnel into the light of day. Up above are ruined castles and battlements, for the Saracens were always fighting folk, and down below, peace, with the lemon groves stretching even to the edge of the sea, bathed in sunshine which seems full of life and fire and wonder.

In a moment of enthusiasm you are almost inclined to retrace your steps to the classic environment of that magnificent ruin, throw yourself on the dry, sweet-smelling turf, and declare that the sunshine which is warming your body is the whole sunshine of paradise, and that further wandering would be waste of time. Then the violet dusk descends with unexpected suddenness, and the lights flash out—the lights from the mountain villages behind, climbing almost to the leaning stars, the lights from the distant coast of Italy, glittering like jewels against the dark background of the unseen land.

With the morrow comes a certain measure of disenchantment. The sunshine is still there, but a great steamer lies in the bay, and the invasion of the place by a crowd of tourists has already begun. Little carriages and motor cars, with numbers attached, filled with the usual crowd of intelligent sight-seers, are dashing up the hill, the streets are white with dust, guides are ranting at the corners.

You carry out your last night's enthusiastic intention, and visit the office which announces villas for disposal, but those on offer seem cold and bare. You have an uneasy conviction that half the world has been before you. Your hotel bill makes you gasp. The price of those two cocktails last night makes you long for the modest tariff of the Embassy! You are told that living is no longer cheap—and you remember that the mutton last night was tough! You decide to consider Taormina for the present as a beautiful dream, and to forget the nightmare waking of those concluding hours.

THE seeker after sunshine becomes in time a connoisseur of vintages, discovering grades and variations in what our earlier enthusiasms acclaimed as above and beyond criticism. When we first escape from our fog-bound climate, with its melancholy procession of grey skies and colourless days, any sunshine which warms our frozen veins and brings that little thrill of springtime gladness to our pulses seems wonderful. But later on, when the habit of seeking for sunshine, as the toiler seeks for his daily bread, becomes an obsession, one develops it finer sense of criticism, is inclined to quibble in a mellowed and tolerant fashion with what in, after all, very near perfection.

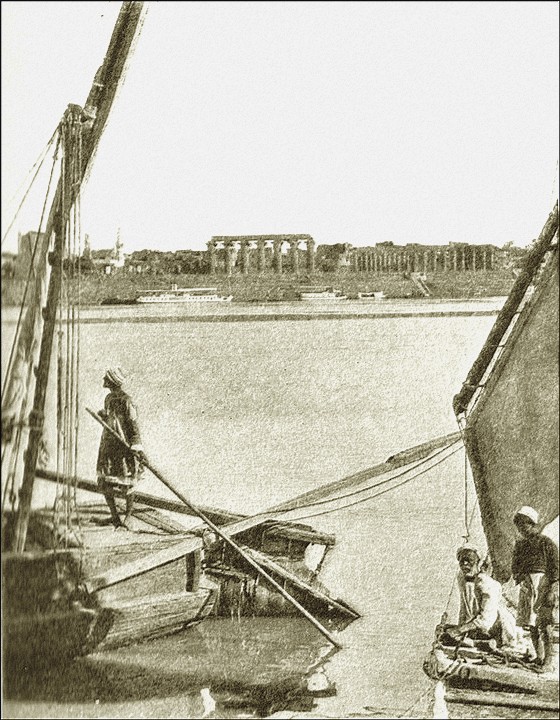

The sunshine of Luxor for four months in the year is, perhaps, as beautiful of its sort as anything in the world. From the inevitability of its gracious dawn, through what seems to be a transparent mist of rosy pink, to the serene, full-blooded majesty of its untroubled departure, it gives us freely and unfalteringly of the great gift which we seek. Although, in a sense, its charm may find its way a little gradually into the hearts of us westerners, accustomed to a more florid type of landscape, how beautiful the country which each day basks in its warmth—that silvery belt of desert land with its oases of cultivation, its green and flowery patches of vegetation. There is a strange beauty, too, about the Nile, as wide here and majestic as at Cairo, four hundred miles north, carrying on its broad bosom the graceful dahabeah, the smaller sailing boats with their brightly-clad fishermen.

Luxor and the Temple.

Away from the river banks, towards the Valley of the Kings, there is a certain dreariness in the colourlessness and desolation, but on the other side of the river, where there are stretches of wheat and rice fields, clusters of palms, and a few Bougainvillea-covered villas, it is as though one had found an oasis of sweet colouring, an oasis with a haunting charm which follows one back to the newer world. The serious side of Egypt, the majesty and wonder of these revelations of past civilisation and splendour, make our own utilitarian passage through the greyer places of life seem sordid and unbeautiful. Almost we are inclined to fancy that there was a lamp hung on high in those days, the light of which has become dimmed for us.

Speculations of this sort, however, make for unrest, and, personally, I should never fancy a day-by-day life amongst such surroundings. One may lounge for a few hours or a week upon the terrace of the hotel, watch the glistening splashes of the Nile through the palm trees, and rebuild in our minds the panorama of the past, but ours, after all, just now, is a more sensuous mission. It is the sunshine of which we are in quest. Here, like the lizards, we may bask in its full and glorious profusion. No hint of a cloud dims the deep blue of the sky. It is as though the gracious lady of our dreams were opening her arms wide, giving without stint or reserve. To cavil in any way, to exercise that hypercritical sense developed by principles of comparisons, seems an ungenerous act here, when what we have sought is offered so freely.

Yet one has one's fancies. Sometimes, half shamefacedly, one is inclined to speculate as to whether there is not a touch of hardness in the serene and even fire of this Egyptian sunshine, something a little overpowering; whether—if you might reduce such a matter to the analogy of sex— there are not masculine qualities in its unchanging heat, as compared to the gentler, more feminine warmth which brings to one's senses the softer stimulus of aesthetic intoxication, the languorous content of bodily and mental well-being. The sunshine of Luxor is a great and glorious thing. It is scarcely, however, the sunshine which warms the heart to peace with the world and life.

I think one could be happy enough at Luxor, especially if the peculiar charm and mystery of the Egyptian landscape make sufficient appeal. Egypt, as we all know, is no longer the country for any one of strictly moderate means, but at least the prices of Cairo do not prevail here. There are some smaller hotels where, for an extended stay, reasonable terms can be arranged, but these are, alas, too close to the dusty and noisy streets for real comfort. There are a few villas too, almost hidden in a wealth of greenery, and gardens sloping down to the Nile. The rent asked for them, however, last time I was there, when one was occupied by a distinguished novelist of my acquaintance, places them outside the pale of all general consideration. Luxor is easily reached, and in most luxurious fashion, by sleeping- car train from Cairo, but it is more a home for the Egyptologist pure and simple than for the ordinary human being seeking to continue an everyday life under gentler and sunnier conditions.

Sunshine at sea, with the eternal sobbing and sighing of the wind in the

rigging, is rather like a cup of strong wine, heady in its exhilaration,

stimulating rather than soothing to the senses. Its kingdom seems

illimitable. A million dazzling gleams of silvery fire reflect its

brilliance. In rough weather the whipped spray is transformed in mid-air into

a cascade of diamonds, the tranquil ocean becomes a rocking sheet of

iridescent splendour. The wind and the tang of the sea form, with the

sunshine of our desires, an intoxicating trinity.

Yet, there is some quality about the sunshine in which we revel joyfully on the ocean which places it in a different category from the sunshine of the land. In the garden of our fancy, when the skies are blue, and the greatest joy in life is in the heavens, its warmth not only steals into our bodies, lulls and soothes our senses, sweetens our pulses and our thirst for life, but gives, also, of its glory to the flowers and to the grass, the budding trees and green earth. Throughout the long day, not only we, but the whole world, seems to drink in its sweetness. It radiates from the blossoming hedges, the trees and the meadows. It is reproduced in the song of the birds, the perfume of the flowers, the murmuring of the insects, the joy of life in the humming bees or the swiftly-darting lizard. It is like a halo upon the land.—But, alas, the sea has no home for its beneficent mistress, after it has once tasted of her splendour. The hard white decks of our steamer show no signs of glorified life where its burning rays have lingered, any more than those flowers of the sea, far down in its mysterious depths, can profit by its warmth. Mankind is, after all, gregarious, and would share his happiness, if only with the grasshoppers. But at sea the sunshine is for man alone.

I HAVE heard of people visiting Corsica in search of sunshine, and finding it. They have the advantage of me. I have been there twice, and found nothing but rain! The country behind Ajaccio, through which I motored during the brief intervals of moderate weather which we were vouchsafed, seemed to be beautiful in a rocky and picturesque fashion, reminiscent, naturally enough, of a more prolific and richer-soiled Sicily. The vineyards are of rough appearance, the cattle thin, and the peasants in their unusually sombre attire lack that frank graciousness of manner and speech to which one has become accustomed in Sicily and in the southern States of Italy. The only bandit I saw was at a café at Ajaccio, and the only wine fit to drink I found at Cortet.

Ajaccio and its Water Front.

Nevertheless, I remember the place with some affection because, on my last visit there, driven to spend nearly a fortnight through incessant rain and rough seas on board a small yacht in the harbour, I completed the first draft of an entire novel! Curiously enough, having landed the next morning, with great difficulty, to visit a barber, I confided to him my experience.

"You," he remarked, "are not like the last author who visited here. He came to write a novel about the place, but the sun shone every day, and he was so charmed with his explorations in the interior that when the time came for his departure he had nothing but a few notes to take away with him."

Afterwards I discovered that this more fortunate person was Joseph Conrad!

I would hate to seem unfair or prejudiced about any place, but this is a slight collection of personal impressions, in no way intended to achieve finality, and therefore I may say that the only impressions I brought away from Corsica were of some very fine pine forests in the interior, some wretched roads, and vast stretches of stony land, a lukewarm regard for a population of poverty-stricken appearance, and of Rain: rain-soaked streets with great puddles like muddy lakes; rain-dripping quays, slippery and dangerous in the imperfect light; the smell of soggy mackintoshes as one crowded into a dinghy and felt the drops from the next person's umbrella trickling down one's neck; the rain-drenched decks of the little yacht which had been lent to me by a kindly friend; rain pattering upon the cabin roof, rain streaming down my porthole window, morning, noon and night. I found no sunshine in Corsica!

Algeciras consists mostly of an hotel, which is more like a hospitable

palace, an hotel wreathed in flowers, impressive with its Moorish

architecture, its great spacious courtyard, its terraced gardens, and

magnificent palms. There are flowers of unexpected varieties, considering the

hardness of the soil, the Bougainvilleas are in themselves a rich feast of

colouring and, for spectacular effect, there is the bay with its crowd of

shipping, less sinister now since the war, but reminiscent always of grim

possibilities.

On the right, the more picturesque Spanish coast stretches to the farthest point of the Straits, and on the horizon the shadowy outline of Africa divides sea and sky. It is hard to find the country behind Algeciras itself anything more than vaguely interesting, with its scrublike forests of cork-trees, its lack of colour and its lank- faced, sour-visaged Spanish peasants. The terraces of the gardens of the hotel are its chief glory, and its grove of trees, to which at night comes a strange rush of birds, only to depart in the early hours of the morning—birds of whose habits and origin everyone professes ignorance, but which certainly lend an air of mystery to the place. In the gardens are many sheltered corners where one may lounge in a flower-scented silence, and bask in the sunshine, which is, alas, in the early season of the year, a little fitful, but always with qualities of warmth and never wholly disappointing.

I always feel that Algeciras has an atmosphere which I have failed to catch. Perhaps the continual crowds of English people from Gibraltar, or tourists from one of the frequent steamers, give a sense of unreality to the place. It seems as though that wonderful corridor and those Oriental-looking gardens with their flowery background were just a scene in some musical comedy, and that these well- dressed, jargon-speaking Anglo-Saxons, nearly all of a certain type, who appear at times to take such complete possession of their surroundings, were just the moving chorus, so that the whole thing becomes quite fantastic, and could never by any possibility exist in actual life. The fact of the matter is that the setting is too small. It is a place in which we put one foot, but the other remains in England. Nevertheless, its gardens, with their wealth of colouring and sunshine, and the views of the glittering bay, contain their own peculiar beauty, and on the days when the launches from Gibraltar are few, and the tourist steamers are not, Algeciras possesses a very pleasant and inspiring tranquillity.

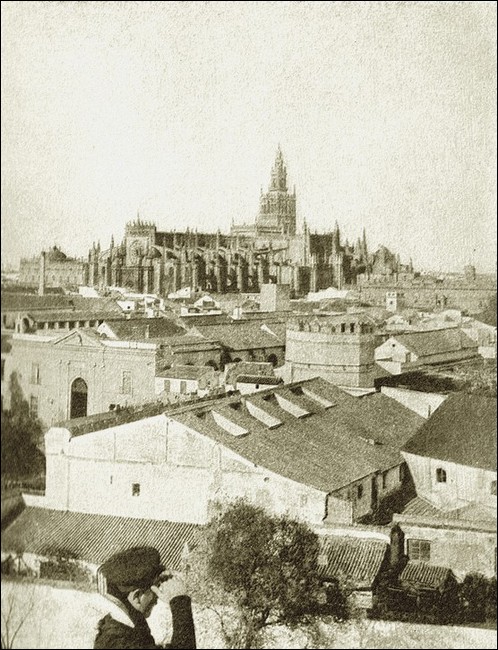

And then, a little farther north—a short distance in any country except

Spain—is Seville. Here, at the proper seasons of the year, is sunshine

in plenty, but there are also occasional catastrophes in the shape of a

devastating east wind which brings with it clouds of the white dust which

lies thick upon the hard country roads. On a perfect day though, with its

garden-bordered plazas, its arches of acacias, its beautiful houses, so

quaintly protected in old- time fashion from the over-curiosity of the

wanderer, its gay, well-dressed throngs of happy promenaders, Seville is

certainly unique of its type, a pastel of sparkling and brilliant life. Here,

too, in the outskirts, are to be found trees, so lacking in Spain; the whole

surroundings of the place, indeed, except along the borders of that terrible

road by which it is approached, show signs of a somewhat richer and more

luxuriant vegetation than usual in this country of windy hills and passes, of

rock-strewn landscapes, of scrubby olive trees and struggling

vines.

Seville, the Cathedral.

Seville in its way is a gem amongst cities—less rich, perhaps, in architectural wealth than some of the other treasure spots of Spain, but still a happy, joyous place with some trace of that humour to be found in the bright eyes, the lips ever ready to smile, and the jaunty bearing of its children, which reminds us of the famous Don Pedro, concerning whom there is still told with relish a certain story so quaint, so indicative of the spirit of his people, that however often one tells it one is tempted to tell it again:

The great Don Pedro, like many other princes of the Middle Ages from Bagdad westwards, loved secret and nocturnal adventures, and was a frequent wanderer in the streets of his city. One night, on his way to pay a belated afternoon call, he found another gallant serenading the lady of his momentary infatuation, engaged him in fight, as he was always ready to do, and killed him. The gallant, however, was a nobleman of quality, and trouble followed. Don Pedro, confident that his disguise had not been penetrated, and aware that only one old woman had been a spectator of the combat, sat in his court and demanded that the murderer be brought before him. The old lady was nonplussed. With an ingenuity, however, the reproduction of which one seems to find in the spirit of the laughing crowds of to-day, she prepared with the utmost care an effigy of Don Pedro which she brought into the court.

"There, Don Pedro," she announced, "is the murderer!"

There was probably some slight embarrassment in court, which, however, was not shared by the person chiefly concerned. He congratulated the old lady and promptly sentenced the effigy to be hanged—justice which seems to have satisfied all concerned.

Seville, however, for all its charm, and its frequent wealth of sunshine, seems to me always rather a place for the scholarly tourist than for the resident. Strangers are welcomed only with words. The place is indeed typical of the whole country, amongst the population of which there seems to exist an almost passionate disinclination to enter into any sort of intimacy with the wanderers from other lands. Spain merely shows her treasures—and bids us depart. But one can console oneself for her inhospitality by the reflection that her climate is treacherous, the conditions of any form of social life impossible, and her cooking, except in Madrid, atrocious.

ON the whole I like Hyères, which may perhaps be considered as the western outpost of the French Riviera, and it is certainly to be taken into serious account by the sun- seeker searching for a spot in which to pitch his tent. In my younger days, it was a paradise for the poverty-stricken. The equivalent to four or five shillings a day provided one with perfectly adequate accommodation even though one had to stay in the town itself instead of mounting the lordly slopes to what is now an hôtel de luxe—the Golf Hotel. Those days have unfortunately passed, but the place still offers many attractions to the person of moderate means. In the heart of the town, but pleasantly situated, are many large and quite excellent hotels, where accommodation can still be had at very much lower prices than in the fashionable resorts nearer the real centres of the Riviera. There are villas here too, in plenty—less pleasantly situated, perhaps, than in some districts, from the fact that Hyères itself is some kilometres distant from the sea, but most of them with the compensation of gardens, and, if their immediate surroundings are a little lacking in specific attractiveness, they are at least situated in a neighbourhood with a hundred outlets into very beautiful country.

At first sight, especially to the traveller who has arrived by train, the approach to the place is not particularly encouraging. The palms which fringe the long boulevard leading to the town have a dejected air, owing to their proximity to the dusty road, the shops are characterless, the hotels, although large, externally uninteresting. One feels that the place lacks atmosphere, yet, beyond, when one climbs the avenue which winds upwards from the main road to the caravanserai dominating the golf links, one begins to realise how it is that Hyères has obtained its vogue.

The links themselves, on a perfectly flat strip of country, negligible to the serious golfer though they certainly are, possess a quaint sort of attraction, hard to put into words. I have picked here, only a few yards from the fairway, the earliest spring flowers: anemones, growing so thickly that as you stand upon the tee you see a little carpet of pink and purple on your right, gently-growing flowers which bend with every breath of the slightest breeze—and, on the left, a clump of stiffly-growing but sweet yellow narcissi. In the spinney farther away there are always violets, and, as the spring draws on, a plague of bees makes the approach to one of the holes—I believe it is the sixteenth—a matter to be considered with some diffidence. Their gentle murmuring seems to take one back to an English meadow where the cows are standing swishing their tails, knee-deep in the rich grass, and the cowslips and buttercups and daisies are starring the fields with yellow and white; or to an old-fashioned garden with hollyhocks, sweet Williams and mignonette scenting the air, and in the distance—in the shelter of a yew hedge perhaps—a neat row of hives.

We cross the road at one part of the course, in pursuit of our golfing activities, and, if we linger in this corner of the world long enough, there is an orchard of cherry trees whose perfume alone is sufficiently intoxicating to atone for a misspent morning doing homage to our national fetish.

Why must we Britishers drag our games with us, I wonder, into all the beauty spots of the world? England, with its chill days, its inevitable associations, almost demands our tribute, generally too lavishly paid, upon the altar of sport, but here, where exercise is less a necessity, it seems that one might do better when one has come to a land full of unexplored beauties, than to make ourselves unpopular by taking away the peasants' land to make a golf course, and continuing with grim seriousness the routine of an English holiday with cup days and medal days and competitions to distract our thoughts from more worthy things. The call of the sunshine in which this country is bathed, after the rain and cold winds of early spring at home, might lure us to better doings.

Hyères is scarcely the centre of the most picturesque part of the Riviera, but it has surroundings full of their own peculiar charm. There is a pleasing and pastoral serenity about its long strips of rich, well-tilled land, the tender shoots of the young wheat, the vineyards looking in springtime as though some careful housewife had dusted and trimmed each morning the sturdy shoots.

Here, too, are the first of the violet farms—soft, alluring carpets of purple and blue, with little narrow footpaths between the blossoms, along which passes the Frenchwoman with her basket; generally she is a woman of past middle age, with a touch of vivid colouring somewhere about her, and a face looking as though it were carved from the wood. In the old days, Madame accepted a few francs with gratitude, and bade one pick here and there as many of the sweet-scented flowers as one cared to carry away. To-day things arc sadly different. There arc numbered market baskets to be scientifically filled by professional pickers, and stowed away on a Citroen farm car. Madame of to-day is still polite, but the wanderer who simply wishes to fill both hands with her blossoms is scarcely welcome. She is too fond of money still, however, to refuse even a five-franc note, but you are no longer free of her scented paradise, and it is a very small bunch which is twisted together by skilful fingers and proffered to you.

There is something about this part of the world reminiscent at times of our own countryside in midsummer. For instance, there is a genuine footpath by the side of a small river which winds down from the background of hills encircling the place. The footpath passes through small woods where the undergrowth is starred with anemones, and where occasionally the singing of birds is to be heard. In the open country it threads its way through meadows where the herbage is deeper and richer in colour than is common in this part of the world, interspersed, too, with many strange grasses which quiver in the slightest breeze, and where, here and there, one finds some of the simpler flowering weeds, pleasant enough to look at and smell, even if they lack the more intoxicating perfume of the violets and cherry blossoms. Here is a good place to repose for a time, to lie down in a corner by the side of a grey stone wall—choose the corner where the wild violets are growing, and a little tuft of narcissi is blossoming in a crack between the grey stones. A good place to lie down with your hands clasped behind your head, to feel the warmth of the sun creep through all the nerves of your body, and give thanks for that spirit of wandering which bade you leave behind for a time the fogs and grey skies, the necessities of work, the daily passage along the sloppy pavements, or in the musty taxicab along the muddy streets. If you can make up your mind to leave those golf clubs alone for a time, so much the better. Attune yourself to the climate, let the spirit of languor creep through your pulses and into your heart, repulse that customary desire to be exercising limbs and body rather than the gentler senses.

This languor, after all, is not laziness. It is in moments of dreaming, with every nerve in one's body at rest, with even one's brain quiescent, with the gentle peace of the quiet places in your heart and the caress of the sunshine upon your body, that sometimes a new energy is born, new figures shape themselves in your brain, and even new ambitions are conceived. I often think that in our daily life mental rest in the beauty spots of the world appeals to us too seldom, finds too small a place in our programme of living and being, and I fancy too that the sunshine helps us to realise it.

THERE was a hot day—towards the middle of last November, I think it was—a day full of sweet odours, when I flung myself at full length upon the yellow sands, with the blue Mediterranean lapping idly at my feet, leaned back against the trunk of a pine tree, drew in one long breath of that sweet fragrance, and swore that I had found my El Dorado, and that where I was I would live and die.

Then I slept—slept, mind you, not dozed—with that perfume lingering in my senses, and the swishing music of the sea in my ears. When I awoke, the inspiration was still with me. I made a pilgrimage to the pine-grown slopes behind, accompanied by a voluble but persuasive land agent, and I considered plots of land. It was the old story all over again. Plots with sea frontage would have needed the gold of a fairy prince; plots on the near and sheltered part of the hillside were sold. There they were, all staked out like lots in a cemetery, and not even my eloquent friend was able to persuade me that the land which remained was really the best of all.

There are many pleasant little spots between Hyères and Beauvallon, but Beauvallon will always remain one of the most charming corners of the western Riviera. Sunshine and sea, pine woods and the sheltering mountains, with a view of the ancient town of St. Tropez over the bay! What could man want more? And yet, when one closed one's eyes, and fancied villas built on all those marked-out spaces, one felt some of the charm fade away; one's gregarious instincts faltered before even the faintest thought of a growing garden city. I love my neighbours, but not building houses!

But what a coast! Hyères lacks the joy of a sea frontage, but here the road winds its way for many kilometres within a few yards of the softly lapping waters of the Mediterranean. There are sheltered places which might be corners in paradise, outjutting rocks from which one could dive into twelve feet of clear, sweet water, sandy stretches upon which one could walk barefoot until one's toes were entangled in the strange, large-leaved seaweed with its pungent odour of the ozone.

One comes presently to St. Maxime, and I have never yet made up my mind whether St. Maxime is a real place or not! There is a toy harbour, there are busy cafés with tables reaching out on to the street, notices imploring you to taste the bouillabaisse and friture du pays of the maison; "mine host", more unreal than his habitation, rotund, waxen-faced, with neatly-curled black moustache, the black apron of the sommelier preserving his trousers, his coat ridiculously short, the ends of his bow-tie flapping round his ears. In his hand is the bottle of wine he is reverently offering to his patrons, in his eyes, as he glances at the passer-by, there is a perpetual wistfulness. There are real men and women, apparently, eating at the tables, real children playing in that tiny square, and in the end you will probably do as I did—succumb, and take a table set out on the edge of the main road which reaches from Marseilles into Italy, gaze frequently across a few yards of shingle to the sea whilst you eat your well-cooked but strangely-tasting food, and drink wine a little different in flavour to any you have tasted before. I tried to get on human terms with my host, but found him, though polite, unresponsive, until I mentioned my eternal quest, my thought of some day buying a villa—a villa which must be in the sunshine, where one could be sure of sunshine all the time. It was then that my host took command of the situation. He took off his black apron, he sent for a bowler hat, and, my meal being finished, he led me out to my car.

"It is the villa which Providence must have intended for Monsieur," he assured me, "for sale by the most marvellous chance. Monsieur will settle there for the rest of his days, and Madame—the inconsolable Madame—must sell, or weep her eyes out."

So we drove a little way along the main road, turned in at a brightly painted gate, and pulled up before the strangest effort in architecture upon which my eyes have ever rested. It was pink and green; it had many angles; it had minarets, cupolas and façades all jumbled together without rhythm or sense of outline. In front was a flower garden in which there were as yet no flowers. There was a tiny vineyard, about twenty metres square, a tiny orchard, the trees of which had yet to grow, a strip of grass upon which the livestock of the establishment—a tethered goat!— was feeding. It was, as my host explained enthusiastically— "Si complet!"

And the interior! Never out of bedlam could one conceive such wallpapers, of an immense design and lurid colouring, furniture of incredible strangeness, a covered-in terrace, built to avoid the sun, with queer chairs, neatly placed in a row, and painted a bright vermilion. Madame, in deep mourning—she had just lost her husband—was there at our service, a cambric handkerchief in her hand, tears ready to flow if good might seem to come of it.

And then afterwards, what I said to Madame, and what she said to me, how I escaped from the house, how I bade farewell to my host, of what lying laudations I was guilty, what vague promises I made, I simply do not remember. I left St. Maxime more convinced than ever that there is something fantastic about the place, that it has been pushed up, or let down, from another world, and that one day I shall wake up to discover it off the map, and shall motor along the road and find nothing there but a peaceful farmhouse, or perhaps a café!

And then, following the Lower Corniche, which skirts all the time the

Mediterranean, there is St. Raphael. Many people like St. Raphael, and there

is no reason why they shouldn't. It has some pleasant-looking shops, one or

two attractive hotels, a short and rather overcrowded sea- frontage, and

beyond, villas—miles of villas—very beautiful some of them, but

somehow a little pretentious for one seeking only a simple, pleasant home in

the sunshine. Behind, at picturesque Valescure, are golf links, a little hard

going, but growing more popular every year. St. Raphael has its devotees

amongst the sun-seekers of the world, and without a doubt deserves them.

Places, however, arc very much like human beings. They attract, they repel,

or they leave one neutral. I am entirely neutral about St. Raphael; probably

St. Raphael feels the same way about me.

Valescure, on the other hand, has charm and possibilities. It is within a few

kilometres of St. Raphael, where even the Blue Train condescends to make a

brief halt, and bungalows are being industriously built amongst the pine

woods which have been wisely left undisturbed so far as possible. Here is

beautiful air, fascinating glimpses of the Mediterranean, curling into the

bays and inlets below, a golf course, rapidly improving, and two excellent

hotels on the links themselves. My only fear about Valescure is that it may

soon become almost too popular, that the bungalows will multiply until it

will rather resemble one of the latest of those garden suburbs with golf club

which are suddenly springing up around our own metropolis. But, after all,

here at Valescure we shall always have the compensation of the softer airs

and constant sunshine, so that when the faintest of west winds comes down

from those sheltering hills, the perfume of the pines is shaken into the

warmed air.

Still travelling towards my particular Mecca—when one is free from that

long arm of villadom which stretches for several kilometres—one comes

to some pleasant and livable country. Agay is a place which attracts, and

which still possesses many delightful sites for building, and, a little

beyond, on the far side of a sweeping bay, is the house of my latter-day

dreams. It is a plainly built, Provençal farmhouse, standing on the edge of

the sea, and, quaintly enough, at the extremity of a little semicircle of

perfectly level meadows which stretch back to the road—not all meadows,

though, when one comes to think of it, for there is a vineyard, from the

grapes of which I was told the best wine of the neighbourhood was made, a

cherry-orchard, and a small strip of arable land. The place is exactly

reminiscent of an exceptionally large and ancient Norfolk farmhouse, of a

severer type of architecture than that which one usually meets with in our

own country. Its stained pink walls and deep red tiles have become mellowed

with age; its front abuts almost upon the yellow sands, and behind, in place

of a garden, there is an orange-grove and an avenue of cypresses. Except for

the more exotic vegetation—the vineyard in place of the turnips, the

orange-grove instead of the apple-orchard, the mimosa in place of the

lilac—it really might well be an English homestead, a little oasis of

restful tranquillity in the midst of a very beautiful but curiously different

country. I have wondered every time! have passed along the road wherein lies

its peculiar charm? It is difficult to define, for its simplicity is akin

almost to baldness. Yet it possesses an air of peace and of gentle luxury, as

though the sun for generations had burned its way into the pinkish-grey

front, and soaked the gardens and meadows with its gentle warmth. It is

somewhat pretentiously called the Château d'Agay, and it is not for

sale—or I should not have told you about it!

The whole of the seaboard between the outskirts of St. Raphael and Théoule

possesses innumerable delightful sites for anyone desirous of building a

bungalow or modest habitation. The villas immediately upon leaving St.

Raphael are very beautiful, very large and very costly. From about three

kilometres westwards, however, there is a curving stretch of coast with many

charming little bays, strips of sandy beach, and an abundance of pines where

the rocks come down to the sea. It is a land of peace, and a paradise for the

sea-bather. The property here is nearly all for sale, and prices can be

obtained on application to a land agent at St. Raphael. There is in one part

a little promontory in a sheltered corner, where one could build to the very

edge of the sea and where a dive from one's sitting-room windows straight

into a pool of deep blue water would be perfectly feasible. Land here, for

some reason or another, has not been bought with the same avidity as nearer

the casino centres, but to the lover of a quiet life, it seems to possess

even more picturesque and sunfull possibilities.

AFTER Agay, although there are some charming little bays fringing the road, and Théoule, near which there is much land for sale which presents possibilities to the sun- seeker, there is no place at which I would set up my Temple to Sol until one reaches Cannes. Just as Hyères may be considered the western outpost of the whole Riviera, so Cannes may take its place as the western boundary of that intensified strip of territory which we have in mind when we speak of the Riviera. Concerning Cannes, I feel myself a little dumb, not because I do not know it well, but because most other people know it probably as well as I do. It is one of the three capitals of the district, and if one wishes to lead the life of gaiety which one usually associates with a holiday upon the Riviera, the choice between Cannes, Nice and Monte Carlo—all three great centres of sport, society and gambling—may be fairly left to one's personal tastes and inclinations.

Cannes, with its picturesque old town and harbour, its magnificently-situated Casino, its pre-eminence in sport, will always attract the élite of the world. Its hotels are the best upon the Riviera, its shops the most expensive. It has a magnificent promenade,—the Croisette—a glorious sea, continual sunshine—although the warmth of the place is a little interfered with by the prevalent winds. There are plenty of beautiful villas in the neighbourhood, especially in the Californie district—some of these, alas, since the decline of the Russian influence, now permanently empty. It is not only the smartest place upon the Riviera, where one meets more folk who are well known in the social world than anywhere else, but it is also the centre of the literary colony. One of the greatest of our living novelists has made his home there, and upon his flower-embowered balcony, with its dazzling view of the Mediterranean, many interesting reunions, enlivened by a lavish hospitality, have taken place.

Cannes and its Harbour.

But, to my mind, Cannes is too brilliant, too vivid in its day-by-day life, and too dead when the so-called season has passed, to ever become the El Dorado of the home-seeker. It is more the Mecca of the tired man of the world, seeking a brief holiday amongst his own friends in a gentler climate. Here indeed is everything to make such a holiday perfect. There are excellent golf links, picturesquely situated; the tennis is world famous; the Casino delightfully managed, with an unequalled restaurant, and the gambling is the most spectacular in the whole district. The best-dressed and the most beautiful women of the Riviera are to be seen here, and, in case by any chance they should find their supply of toilettes insufficient, there are branches in the Croisette of nearly every one of the famous dressmakers and milliners whose headquarters are in Paris. Probably in its varied appeal to the world of society and the world of sport, Cannes, which from January until the middle of March is full of vivid and pulsating life, is pre- eminent upon the Riviera. To the ordinary person, however, the Croisette at the fashionable morning hour becomes a little too much like the Rue de la Paix, or Bond Street, and one is inclined to doubt whether it is a real heart-hunger for the sun which has brought this cosmopolitan but aristocratic crowd to frolic in a gentler atmosphere. Yet, for whatever purpose they come, the place is the gayer and the more brilliant for their presence.

In one very important respect, the administrative powers of Cannes seem to have been guilty of a peculiar short-sightedness. They have failed to realise what has been dawning upon every lover of the Riviera for years—that this is not only a land of refuge for a few months from the rigours of a northern climate, but that it is a very delightful resort in the summer months. Farther down the coast, the realisation of this fact has caused an immense change in the local conditions. At Cannes, however, with the commencement of May, the place may be said to go to sleep. The Casino closes, the Carlton draws down its blinds, the Croisette shops put up their shutters, the tennis courts are deserted. Along the whole front you will scarcely see a solitary promenader. The place has suddenly taken to itself the atmosphere of an English country town on a Sunday.

It is an ill wind which blows no one any good, however. Along the coast, only

a few miles away, Juan-les-Pins—in the days when I first knew it a

hamlet of no significance whatever—is rapidly establishing itself as

the centre of summer life upon the Riviera. A wonderful Casino has been

opened there—and I use the word advisedly. Some inspired

person—or group of persons—showed themselves possessed not only

of vision, but had the courage of their convictions, and, instead of building

a casino as an experiment, built one which can compare favourably in

architecture, management and cuisine with any similar establishment

along the coast. As soon as the gaiety at Cannes is over—sometimes even

before then—the place is filled with parties from the villas and hotels

of her more aristocratic neighbour.

There is an open-air terrace, overhanging the sea, upon which it is a sheer delight to lunch or dine, and, later on in the season, the little place becomes reminiscent of Biarritz or St. Jean-de-Luz. Ample and excellent accommodation is provided by the Casino, and the sandy beach is crowded with bathers, lying about taking their sun baths, with no cold winds or grey skies to send them hurrying into a bathing tent, or to rub themselves, shivering, with a great towel, but with a sun the strength of which is always tempered by a slight sea breeze, and which at the end of a month is capable of producing a new race of human beings, tanned and bronzed to an almost unrecognisable extent. From the terrace of the Casino, one can watch all this, or join in, and return afterwards for one's morning apéritif.

At night one can dine and dance in the same surroundings. Last summer, for instance, the popular invitation was to bathe and stay on and dine. People who shrink shivering from the idea at any of our own watering places here enter the water fearlessly. I know a lady in her fifty-ninth year, who has learned to swim within the last season—a confirmed and ardent Englishwoman, but very difficult now to drag away from these warm beaches even during the hottest months of summer.

JUAN-LES-PINS, however, is temporarily paying the price of its too great success, of the wonderful vogue which it enjoyed after the opening of its Casino. The speculative builder has marked it for his prey, and it is as though the heavens had opened and let down a torrent of mortar-tubs, scaffolding-poles, cement-blocks and piles of masonry of every description. Villas creep up like mushrooms in the night; the whole town is a bedlam of noisy industry. However many attractions a place may possess, they can scarcely survive an atmosphere of brand-new buildings, the state of continual hammering, the condition of unrest when a whole neighbourhood is thrilled with excitement at the idea of making money with undreamed-of facility. Land speculators haunt the bars of the hotels and Casino, hint at extraordinary bargains, concerning which decisions must be arrived at during the next few hours, whisper of gigantic deals consummated on the previous day. There are stories of plots of land which have changed hands half a dozen times during the week. There is all the fever of easy money-making in the excited atmosphere. Nothing will ever detract from the popularity of Juan-les-Pins as a bathing resort, as long as there is an inch of space left to lie on its brown sands, a yard to turn over in the sea, or a vacant table even in the most retired corner of the Casino terrace, but anyone seeking a home in the place to-day would have to be a man who loved his neighbour's elbows.

One breathes more freely as one traverses the sea road, and, through a still

apparent but decreasing maze of villadom, arrives at the Cap d'Antibes. Here,

a single hotel monopolises one of the most beautiful sites on the whole

Riviera. Its plain, undecorated exterior, with level rows of windows,

presents the appearance of an old French château, and, from its broad

front to the sea, a straight road has been cut through what was once a dense

pine forest. Here, indeed, is a veritable refuge for anyone desiring to

escape from the gayer life of the Riviera, to remain in touch with it and

yet, in the grounds surrounding the hotel and reaching to the sea, to attain

an isolation rare and difficult in this too popular neighbourhood. The genius

of a venerated and happily obstinate hotel proprietor has kept the land

agent, with his almost fabulous offers, entirely at arm's length.

Cannes and its Harbour.

Here is to be found solitude—secluded spots at the fringe of the woods, and the borders of the sea, or farther back amongst the strong-smelling pines, where one can choose one's own little view of the glistening sea. There is no road, or any sort of thoroughfare near, save that one broad avenue from the hotel to the beach. You can attain here all that quietude of environment which is one of the delights of the pilgrim sun-seeker. You can stretch yourself out on a sun-drenched bed of pine needles, give your body to the sunshine, and send your thoughts wandering into the soothing and pleasant places. No one will disturb you. You will hear the murmuring of the sea. You may catch glimpses of a little company of Morris dancers, indulging in their strange antics upon the flat roof of a building overlooking the bay.

Presently, if the fancy takes you, you can plunge yourself into those amazingly blue waters. There are no sands to lie about upon as at Juan or Alassio, and you must take your sun bath, as nearly the whole world here does, on the rocks. The greatest luxury of all is to lie there until the moisture has been dried from your body, and the salt only remains, and then wrap your dressing gown round you, and go back to your quiet place. Any touch of languor has gone. You feel that with the sun and the sea you have helped yourself to the greatest gifts of life, and, with a perfectly healthy human instinct, you have the inspiration to return in some measure these wonderful offerings. It seems that yours is the most pleasant task in the world, as, with pencil and notebook? by your side, you set to work to trap the fancies of your stimulated brain. One feels that before long those woods must go in face of the ceaseless and urgent demand of the land speculator, but whilst they remain we are grateful for them. The name of the hotel—why should I conceal it—is the Hotel Cap d'Antibes, and I take off my hat in respectful homage to its proprietor, who has refused a great fortune for his grounds, and kept them for the solace and enjoyment of his visitors. Some day or other, alas, one feels that conditions will change, but until then there remains the most ideal spot for either summer or winter residence I have ever come across in the course of my wanderings, with a single, but sometimes fatal, drawback—it is not to-day for the man of strictly moderate means!

There are beautiful villas between the Cap and Antibes itself—one

especially, on the edge of the sea, sheltered, retired, with perfect bathing

and outlook, the home, as seems fitting, of a literary man of

distinction—but the most desirable of these are all too firmly held.

One must pass on to the wider spaces, where the land hunger is not yet born,

if we would seek the peace that goes with the sunshine. There are pleasant

spots around Garoupe, but too many people have already realised the fact, and

so, through the old city of Antibes, we come once more to the Route

Nationale. Purposefully, for the moment, we pass through Cagnes, with only a

glance at the ancient town on the hill, and the inviting-looking valleys

beyond. We reach Nice, which I suppose may be called the metropolis of the

Riviera.

The Port of Nice.

I can give Nice nothing but the Promenade des Anglais, seven miles long, and one of the most famous sea-bordering walks in the world, a wonderful sea, and its full measure of sunshine, very fine hotels, and cheaper shops and markets than either of its neighbours. At the back of the old town is Cimiez, where many people still live contentedly in fine villas and comfortable hotels, and certainly in a very sheltered spot, with a magnificent sea view and complete immunity from the cold winds.

Nice, notwithstanding its size, its population, and its reputation as the El Dorado of the bourgeoisie, is not to be lightly dismissed as a place of residence. It is distinctly a handsome city, with two fine casinos, a very good opera house, many picture-palaces, and excellent shops. There are many of us to whom an urban life by the sea presents many attractions. Nice offers them all. She is the Brighton of the Riviera. She offers cheap living, fine air, plenty of amusements, and a magnificent sea promenade. The Jetée Casino is built like an English pier, over the sea, and you can dine, gamble or dance, with the music of the waves in your ears. There arc Russian restaurants, dancing places, cafés galore of all characters. There is a night life, which I have insufficiently explored, but which my young friends tell me should provide amusement for the most enterprising pleasure-seeker. The gambling here is perhaps more cosmopolitan than at any place along the Riviera. The game is frequently higher even than at Cannes, and one hears sensational stories of immense sums which have sometimes changed hands in a single night. For some reason or other, Nice seems to have become the headquarters of any Eastern potentate who may come this way, and his presence invariably attracts the professional gambler from Cannes or Monte Carlo, or wherever his temporary resting place may be.

As a home for sport, Nice is not to be despised. Her race-course is crowded every Sunday, she has an aerodrome of considerable size, her tennis is thoroughly well- established, and the golf, although it is nine kilometres away, of its kind excellent. As a further tribute to the sporting instincts of the place, I might add the fact that there is no pigeon-shooting!

FROM Nice, travelling eastwards, we pass Villefranche, with its magnificent harbour where, from the Corniche road, a dazzling height above, a warship looks like a toy boat in a violet sea, pass also Cap Ferrat, bristling with villas—a very attractive stretch of land, but which we do not seriously consider as a place of habitation, as the villas are all eagerly held, and the hotel is always overflowing. There is land still to be bought—one particular strip overlooking the harbour of Villefranche, with many attractions—but personally I have no fancy for villas built on dizzy promontories which overhang the sea; and the view, beautiful though it may be, would never compensate one for the climb up from the sea-level after the morning's bath.

On the other side of the Cap, which is naturally more exposed, there is some land for sale on the sea level, but this particular little corner has become the Mecca of cheap restaurants. Altogether, to my thinking, Cap Ferrat lacks that reposeful air which is the chief charm of the country westwards, and in a matter of sunshine, the towering background of rocky hills, the last ridge of the Alpes-Maritimes, rather shorten the hours of our delight.

Beaulieu has its attractions, but its intensely English character destroys our sense of being abroad, and its villas are either too magnificent or too unattractive. There is a little harbour, overlooked by an incongruous medley of pink, brown and green houses, and, during four months of the year, one of the best restaurants in the world opens its hospitable gates to the dilettante in food.

Beaulieu, the Harbour Front.

From a spectacular point of view Èze imposes itself upon the notice of the wanderer along this sun-warmed coast. The old town, built a thousand feet above the sea, precipitous, age- and battle-scarred with the years, occupies a truly commanding position from every angle; but as a dwelling-place, although a few English artists have established a precarious home there, it is scarcely to be seriously considered. There is no drainage, the streets are narrow and impassable for any form of vehicle, and the few inhabitants who toil in the terraced vineyards and olive- plantations near at hand seem more than any other community along the coast to have preserved the Saracenic blood and savagery of their direct ancestry.

Èze and the Côte d'Azur.

But sheer below, on the sea-bordering road, there is a strip of beautiful and fertile land, with a handful of very attractive villas smothered with flowers. Their gardens are an oasis of colour and perfume at all times of the year. One villa, early in the season, is hidden under its Bougainvilleas; nowhere is there such a wealth of mimosa; roses grow out of the very walls, and, as the summer months advance, the terraces are festooned with ivy geraniums of every shade of pink and scarlet. Unfortunately of land here there is little to be sold—so little that as a place of even temporary habitation it is scarcely to be reckoned with. But those gardens—so rich in colour, in cunningly devised, sheltered corners, in lemon-trees and the rarer flowering shrubs! I sometimes think that the traveller passing by train, within reach of the perfume as well as the vision of all this loveliness, may well believe that this is a little corner of Paradise into which he has made his way. Round the bend in the road is Monte Carlo, with all its pageantry and paganism. But here is beauty!

Cap d'Ail, with its huge hotel and handful of villas, has little more to

offer. The fact is, in these districts, although they comprise the very heart

of the Riviera, the land speculator and builder has had little chance to

pursue his vocation. The seaboard is too narrow, and inland the rocky hills

are too steep to make building operations practicable. I know of no place

between Nice and Monte Carlo which I should recommend to the sun-seeker for a

lengthened sojourn. But Monte Carlo, the most discussed, most belauded, and

most upbraided place upon the Riviera—that is another matter!

Monte Carlo, curiously enough, has a life at which few people guess—an almost domestic life lived by families of English folk, some of whom discovered it as a beauty spot even in the days when olive-trees were growing on the site of the present Casino. The number of residents has increased year by year, and it is an undoubted fact that few people who have once taken up their abode here ever leave—as for instance, one of our most brilliant and popular women authors, whose villa in the heart of the Principality is a happy meeting place for kindred spirits.

Monte Carlo from the Pier.

For sheer picturesque beauty Monte Carlo easily triumphs over its neighbours. It has every quality which attracts. Its streets are beautifully-kept, its gardens filled always with choice flowers; its restaurants are equal to any in London or Paris; there are two famous tennis clubs, and its golf, although a little sensational in character, is situated amongst surroundings unique in the world. The trouble about every critical appreciation of Monte Carlo— and there arc plenty of them—is that too much is written about the Casino and the gambling, and too little about a very elusive but real atmosphere with which the place is without a doubt endowed, and which makes it one of the most important and in some respects beneficial of the health resorts of the world. Aix-les-Bains, Vichy, Evian, and a score of others, all have their much-advertised baths and cures. What they may do for the tired body, Monte Carlo can often do for the tired mind. For the place does possess that most intangible of gifts, an atmosphere, and if that atmosphere could be subjected to analysis, like the waters of these famous body-curing centres, it would be found to contain the allegorical equivalent to the chemical formula for gaiety.

It is the greatest thing in the world to be light- hearted, and if one thinks of it one can only be really light-hearted with light-hearted people. Turn your back, actually and mentally, upon that stuccoed and minareted pile of architectural absurdity, the Casino, and stroll across to the café. When I was a young man in Paris, they used to say that if you took a seat outside the Café de la Paix in the Boulevard des Italiens, and stayed there long enough, you would encounter every acquaintance you had ever made, even in the most distant corners of the earth. To-day the same thing might be said, with even more truth, of the Café de Paris at Monte Carlo. It is always full at the popular hour, but there is always a table. The ubiquitous little company of strangely clad maîtres d'hôtel, ever watchful and attentive, see to that. Stroll about amongst the crowd as though in search of an acquaintance, and try to find the conventional gambler with his lined face and weary eyes. You won't find him, because he scarcely exists. Try even to pick out a loser, and you will probably fail. You will find men and women, girls and youths, of every nationality, mostly laughing. Such a motley gathering! A sprinkling of the tennis crowd, the men in flannels, tweed coats and white mufflers—good-looking men too, most of them, burned with the stinging breezes of Mont Agel, or the sunshine pouring down on La Festa; Frenchwomen—dangerously attractive—such smiles, such intimate whisperings, such an abandon of mirth when the story is told; family parties too, in soberer groups, flirtatious couples, a sprinkling of camera-slung Americans from the steamer in the bay, taking in their surroundings with that vivid gift of swift appreciation which they have made a national characteristic. And behind, the Gipsy band, bending to their task, which is to preserve their wonderful music and yet let the voluptuous thrill of it sob its way through the babel of voices. Very little drinking—for an intensely sociable place, one drinks less in Monte Carlo than any other place in the world—the lightest of apéritifs, grenadine and orangeades. But the laughter! And why?