RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Title Page

Headpiece from Lippincott's Monthly Magazine

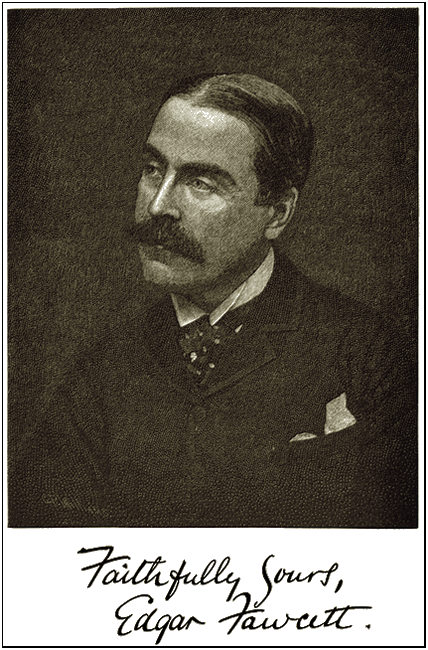

Frontispiece

Edgar Fawcett

ALL day there had been a warm rain, with fog, and sometimes low growls of thunder. But toward evening it cleared off, and you saw blue pools of sky in the west, with flat strips of gold cloud, calm and dreamy as if they were beaches of the Fortunate Isles.

A fresh wind sprang up, too, with woody perfumes on its unseen wings. As this delightful breeze blew in the face of Hugh Brookstayne, he smiled to himself for pure refreshment, and that sense of spiritual expansion which comes to a scholar who has been pent among books throughout a dull and rainy day, and finds that the weather, after all, is not the sluggard and churl he has grown to think it.

This nook which he had chanced on among the mighty Swiss Alps just suited him. Veils of vapor were hurrying away from noble green mountains on every side of him, as he trod the pale smooth road fringed with splendid pines. Some of the great peaks were not very far off, though you did not get a view of any snow-clad summit unless you made a certain little détour for the purpose. Hugh had chosen this especial spot because it had seemed to him the least sublime in a country of sublimities and exaltations. His pension was quiet, and not badly kept for one of so meagre a size. He was not at all a hater of his fellow-Americans, and yet it pleased him to have found lodgement where he met only a few stout, commonplace Teutons, with a light sprinkling of bourgeois French. By paying a trifle more than the regulation eight francs a day he had secured a commodious room, whose casements gave upon a sheer cliff over which drooped the white airy foam-scarf of an enchanting cascade.

All in all, he was highly pleased with his summer quarters. When he needed exercise, diversion, and a change of scene, he could start off at a swinging pace for Lucerne and note the glorious panoramic changes on either hand until at last he reached that happy vale which even throngs of the most prosaic tourists cannot make less lovely than it is. More than once he had smoked a cigarette and sipped beer on the piazza of the huge Schweizerhof, and told himself how fascinating was this gem of all Alpine towns, lying beside its peerless lake. He had strolled under the low interlaced chestnut boughs in the walk that fronts the great hotels, and had watched Pilatus, Titlis, and Scheideck, looming in their variant grandeurs of contour across the blue-green waters, or that steep, dark flank of the Rigi whose habitations always look to the gazer below as if toppling over the precipice near which they are so dizzily built. He had traversed more than once the roofed bridge across the fretful Reuss, with its faded mediaeval pictures, or had sat and thrown crumbs of cake to the swans in the grottoed and fountained basin below Thorwaldsen's noble-sculptured Lion. This immortal carving, as it gleamed from the solid rock-wall of whose dumb blank it made an almost sentient part, would pierce him with suggestion. The whole place, however small might be its limit, struck him as no less lordly than monastic and consecrated. 'Never,' he would tell himself, 'was so superb a tomb raised to the illustrious dead. Art has here asked herself what she shall do that will be grandly commemorative of those loyal Swiss soldiers who died in defence of their king, and Nature has answered the question by saying to Art, "I will mate my powers with yours!" Together they have made this unique monument, overwhispered by these towering elegiac firs!'

But this afternoon Brookstayne did not go as far as Lucerne. He paused at the door-way of a small inn which he would now and then visit during his briefer strolls. The little room beyond was vacant, except for one man, seated off beside a rather remote window; the man's back was alone visible; he did not turn or move in any way at the sound made by Brookstayne's feet on the sanded floor. Soon a lank waiter came shambling in, to take the new guest's order. A sallow smile lit his fat blond face the moment he recognized the new-comer.

"Ach, mein Herr; habe die Ehre," he began, with his most cordial gutturals. "How can I serve you this evening?"

"By making to-morrow finer than to-day has been, my good Hans," replied Brookstayne, lazily seating himself.

Hans grinned. He thought this big-framed American gentleman, with the kindly hazel eyes and the short, dense auburn beard, a most winsome and gracious person. After Brookstayne had got his mug of beer and lighted his brier-wood pipe, he fell into a revery which the dreaminess of the hour no doubt induced. Outside, those golden glamours had not yet faded; they seemed to burn with even keener vividness as he watched them from the window at his elbow. But just beneath, glimpsed between monstrous buttresses and stanchions of mountain, was a bit of liquid, living emerald,—the divine lake itself! Brookstayne leaned forth upon the sill, breathing the moist, scented midsummer air. That radiant spot of water burned for him like a star of hope.

He was excessively ambitious. Now in his twenty-eighth year, he had already achieved note if not plain fame as the author of two strikingly fresh and acute scientific works. During the winter he held a somewhat subordinate though responsible position in a Massachusetts college. He had sailed for Europe in the previous spring with not a few sharp misgivings about the size of his letter of credit and a great desire to talk with three or four eminent scientists in Paris and Berlin. He had accomplished the latter object, and had indeed done considerably more, since words of the most stimulating praise from these high-priests of knowledge now dwelt with him as vital souvenirs of his interviews. The chief study of his life related to questions of cerebral function, capacity, structure, and degeneration. It had long ago occurred to him that if we benighted mortals could learn really to grasp and define the meaning and the working of our own brains, we should reach grades of elevation hardly more than imagined to-day; for besides being a scientist Brookstayne was a philosopher, a psychologist, as well.

His new work was progressing in a way that cheered him to think of it; By September he would have got it half finished, and then, in the long winter evenings at his placid New England home, he could continue and end it with that mental security which comes from having made a momentous beginning. All through the present day he had been dealing with a knotty and problematic point on the subject of hallucination. He had had time to make some copious notes at the K.-und-K. Hofbibliothek in Berlin and the Bibliothècque Nationale in Paris, but even these had not proved fruitful of precisely the aid requisite.

'What that chapter now needs,' he mused, puffing at his pipe and watching the smoke from it waver somnolently out into the lucid yet dusky gloaming, 'is a personal, practical record of some experience with a fellow-creature beset by a mania which leaves him outwardly sane and yet has rooted itself into his daily life and thought. Some close study of that kind would make an admirable finis to my "hallucination chapter."' Here he smiled to himself, and unconsciously drummed a ruminant treble with the finger-nails of one hand on the wooden table before him. 'There's that huge lunatic-asylum at home, not far from the college. Perhaps I could find my "specimen" there. I've a mind to search for him when I go back. It might not be a very pleasing task, but then my nerves are still good and strong.'

He did not know how soon and how drastically their strength was fated to be taxed. Only a little while after this, it chanced that he let his gaze wander toward the window at which was seated the one other occupant of the room. That personage had ceased to peer forth into the luring sunset glimmer, but had now half turned toward Brookstayne, though not showing the least sign of consciousness that the latter had begun to observe him. His head was drooped, and a soft revealing glow smote it, with something of the artificial effect so often seen in modern photography. Only the stranger's profile was visible, but how fall of beauty and power that showed! Brookstayne, unlike most men of the ratiocinative turn, loved art, and it now occurred to him that a knack of swiftly sketching so rich a "subject" would have wrought high satisfaction. The gentleman himself must surely never have become aware that his likeness was being covertly taken; he looked absorbed enough to refrain from shifting his posture if Pilatus, with fierce terrene clangors, had suddenly slipped into the lake.

The high, unusual light cast upon his facial outline made even one long upcurling eyelash evident. But above this gleamed a brow massive and scholarly, while below it was a nose arched in the faint yet definite purity that we call Greek; then came a moulding of mouth and chin virile, sensuous, poetic. He wore neither beard nor moustache, and his scant whitish hair, growing somewhat back from the temple and ceasing a little further upward, gave the whole silhouette a mature look which its lower lineaments failed to warrant. These appeared almost youthful, and in them, clothed as they were with unaltering pallor, Brookstayne seemed to detect the symmetry of perfect sculpture.

'A man with a past,' he began to muse. 'A man who must have suffered deeply,—the drawn-down muscle at the corner of his mouth more than hints of that; who may have loved passionately,—the firm yet ample curves of throat and chin suggest that. He has a brain of no mean force, too, for the brow is so generous. Not the face of a poet, in spite of his rapt and pensive mood while I watch him. Something like an austere challenge to imagination or fancy invests every feature. He might be a mathematician, or a drinker at the well of science, like my poor ardent self. But, whatever he is, he interests, attracts me... Yes, wonderfully ... I should like to know him. I—'

Brookstayne's meditations paused there. Abruptly the stranger had risen, and, with the air of one who has been roused to an unwelcome realization of some discomforting gazer, he now turned, making his full face apparent.

A thrill of horror shot through Brookstayne's nerves. It was not a full face at all. The other side of it, hitherto unseen, was almost entirely gone. Never was the spell cast by beauty more quickly and cruelly broken.

'Good God!' thought the man who had been silently admiring him. 'He is not a human being: he is a monster,—a creature whose face has only one side. How terrible!'

While Brookstayne sank backward in his chair, the man who had dealt him so sharp a shock passed slowly from the chamber and disappeared. He had a limping step, which denoted lameness in one limb, and bore a stout cane which he used as a palpable support.

Left alone, it was some little time before Brookstayne recovered from his dismay and consternation.

AT length, however, he regained composure, and softly laughed at his own weakness. But curiosity replaced bewilderment. Hans, the waiter at the inn, presently appeared, and a prompt series of questions followed.

Oh, yes, Hans knew the gentleman very well. He would often come in and sit like that when he thought there was nobody about.

He usually chose just this hour, but he did not come by any means every day. Oh, indeed, no. Sometimes he would not be seen twice for a whole fortnight. He lived not far away. Did not the gnädiger Herr know the chalet next to that one which a huge stone had fallen on and crushed? Yes? Well, the gentleman lived there. Two old peasants, a man and a woman, kept the place. It had been said that they were relatives of a certain servant whom the gentleman had once had in another country.

"And pray, what is the poor fellow's name?" asked Brookstayne, with almost an irritated tone; he was so tired of hearing "gracious gentleman" repeated over and over.

Hans made an effort, which resulted in a sound somewhat resembling Stoffot. Then he shrugged his big shoulders and smiled at Brookstayne with a queer, herculean wistfulness.

His hearer gave an encouraging nod. "Stafford," he said. "An English name; no doubt he's an Englishman."

No; an American; Hans was sure of that; he had heard from the old woman of the chalet; she sometimes came there and gossiped a little; she and her husband were so sorry for Herr Stafford.

"Oh," said Brookstayne, with lazy irony, "I see. You're very discreet, Hans; you're loath to tell me, point-blank, that you've done most of the gossiping yourself. Well, and did you find out how this Herr Stafford received that frightful mutilation? Was it an accident? Or can it have been a deformity that he was born with?"

But the old woman, Linda Hertz, had no real knowledge of what had caused it. Her daughter had gone into service at Berne, years ago. There she had met an Englishman and married him, leaving her native land to live with him in England. Later, when her husband died, she had emigrated to America, and there had again entered service, this time with a family named Stafford. One day, not very long since, she had brought the gentleman with the strange face to dwell at the chalet. She had answered very few of her parents' inquiries, had Hilda. She had merely told them that Herr Stafford was a very quiet and harmless gentleman indeed, though it had been thought by some people who knew him in his own country that he was out of his mind.

"Out of his mind?" Brookstayne broke in sharply, at this stage of the narration. The phrase concerned his own rattier, so to speak; he listened with closer attention to the rest of the recital.

That was brief enough. Hilda had said something about a railway calamity, but her parents had doubted this explanation. Yet they had soon found their daughter was bent on giving them no further details. Herr Stafford, she instructed them, would pay handsomely; and he did. She went away and left him there; she had been absent several months, now. He was easy as a child to get along with,—much easier, in fact, for his wants were few, and he would either stay for hours at a time quite silent in the little room that had been fitted to suit his simple tastes, or wander forth among the loneliest dells and slopes when the weather permitted, only now and then coming to the inn if it seemed void of visitors and taking a glass of red wine and a bit of brown bread. On his arrival he had worn a bandage over the hurt side of his face, concealing it, but this had greatly discomforted him, and afterward he had altogether given it up. Both Frau Hertz and her husband felt sure that he was crazy besides being so oddly deformed. At first they had been very timid about having him there in the chalet, but the money was so acceptable. And then had not their daughter, Hilda, been mindful of them in their old age for a long time past, sending them help each month from her own earnings? It would never have done to disoblige their duteous Hilda, the old couple had concluded. But now they had grown thoroughly used to their guest, and would have missed him a good deal if he had left them. Still, it did look very much as though he were out of his head. Some sort of ghost appeared to haunt him, seen only by himself. His one eye (for only one remained to him) would almost start from its socket at times like these, and he would gnaw his lips in a wildly restless way. But such fits may merely have meant the return of unpleasant memories. Hans wished to be honorably exempted from the ghost-idea. He had no beliefs of that superstitious kind. He had gone to school in Zürich till he was fifteen. It was different with two old peasants who had never seen a city larger than Basle, and scarcely knew how to read their Bibles.

Brookstayne longed for another meeting with the ill-fated being who had so lured and yet so repelled him. He could not help feeling convinced that any human creature who lived in such complete loneliness would not wholly shrink from communication with his kind. Between pity for the man's frightful affliction and a professional impulse to note his mental state, the young scientist was perhaps equally swayed. This double motive produced, in the course of a few days, its natural result. One afternoon Brookstayne happened to be passing the chalet in which he was aware that Stafford dwelt. Suddenly he perceived a shape, standing with folded arms and drooped head amid a knot of fir-trees, just where a lawny space broke away from the common road. Then, as he became nearly certain that he had recognized Stafford, the shape slid out of sight For a moment Brookstayne hesitated. Then he turned his steps in upon the springy turf and walked straight toward the little thick-boughed grove. He had been right. The loiterer was really Stafford, and now, as they confronted each other, Brookstayne once again felt his flesh creep. There was something literally unhuman about the visage into which he peered. When thus directly seen, it made you heedless of the fine moulding one side revealed, because the other was so denuded of flesh and entirely ghastly. The left eye was missing; the left cheek seemed to have been quite torn away. An outward force must have wreaked the desecration; that he had come into the world with it was an untenable belief for any one with the least experience in flesh-wounds.

He recoiled while Brookstayne approached him. Then, as if having made up his mind that the intrusion was a premeditated one, he stood motionless, with an air of doubt and trouble, though not by any means of incivility.

At once Brookstayne spoke, with tones all courtesy and gentleness, yet guarded against a sign of undue compassion. "Pardon me, but you seemed a little lonely here, and I thought I would make bold enough to come over and have a word with you. We are of the same nationality, unless I am mistaken," he went on with his frank, sweet smile; "and I have always found that two Americans, no matter how radically they may differ on a hundred diverse points, are sure to have that one for purposes of agreement."

"You know, then, that I am an American?" was the reply. It came in a grave, soft voice that put the hearer almost wholly at his ease again and made him glad of his recent overture.

"Yes. Hans, over at the inn, told me."

"Ah ... the waiter, there... yes."

Brookstayne clearly saw that he meant to be quite courteous, but also that a miserable mixture of shame and dread had begun to work havoc with his self-possession. What, however, could he fear? The revolted feeling that this nearer view of him might awaken? Doubtless; and already he had witnessed, most probably, like seizures of disgust at various other periods. Brookstayne's pity deepened while he furtively watched how the slender and well-shaped hands had commenced to tremble as this retiring son of solitude strove not to cower before the publicity of even his own single look.

A sudden irresistible impulse took hold of the young student. It was a quick growth from a soil that dealt only in good products. He laid one hand upon the shoulder of the unfortunate man beside him, and said, with speed, fervor, and a ring of manful sentiment vibrant in each word,—

"Don't think me too bold and rude if I tell you that this great seclusion in which you live is a very bad thing for you. I'm something of a physician, and so am able to speak rather knowingly. I saw you, not long ago, there at the inn. You don't remember, of course; you had but a glimpse of me in the twilight before you rose and went out. And will you pardon me if I confess that I asked our friend Hans a few questions about you? He really told me very little. But he told me that you are an American, and that your name is Stafford... I suppose I am desperately presuming. But now, having so scandalously betrayed myself, I shall go on and say to you that my quarters are only a short stroll from here, that my name is Hugh Brookstayne, and that the fact of our being neighbors and fellow-countrymen might form an excellent excuse for us occasionally to see one another."

Some men could have made this kind of familiar outburst easily offensive. Brookstayne could not have made it so if he had tried. His manner was one of well-blended intimacy and delicacy, and withal touched by a spell of the hardiest honesty and good faith, like the light which breaks along edges of certain felicitous portraits.

The effect of his words immediately told. He had stretched out his hand to Stafford with delightful daring, and a second or so later it was met by a nervous and somewhat feverish clasp.

"You are very good, Mr. Brookstayne,—very good indeed... I have never been one who cared much for the company of his kind. That is, I could do without it, even before... well, before the gloomy thing occurred which has made me as you see me now. And since then" (there was an accent of strange pathos in the speaker's voice, at this point) "I have thought it best to accept a completely solitary life..." The hand dropped away from Brookstayne's here, and the fearfully outraged face turned away from him also, leaving visible only that profile whose beauty became swiftly manifest as by some almost theatric trick of transformation. "I appreciate the kind sentiment which has caused you to address me," he continued. "Candidly, there are many men whose advances would have proved a positive pain to me. Yours do not. And yet I cannot respond to them as you have so genially suggested that I should. I cannot. There, just that terse little sentence must be enough. I don't mean it rudely. Mine is an ended life. I am here waiting for it really to close, and in comparative peace. The sooner it closes the better. If I were not beset by certain very bitter memories I should call my days here actually pleasant. The life that has renounced both hope and energy is not always a miserable one. There is a sort of moral and mental drowsiness that steals over it, like a tired child's longing for the sleepy depths of its crib... you understand... Good-by, and many thanks, Mr. Brookstayne; many thanks..."

He passed at once out of the grove toward the chalet, whose thatched and slanted roof was overbrowed by an enormous wall of beetling mountain. Brookstayne watched him disappear, and at the same time said to himself in stubborn protest that this meeting should not be their last. Now that he had broken the ice he meant that its aperture should not get time enough to freeze over again.

Oddly determined in any purpose finally formed, and armed with his rare native gifts of mind and mien, he at last won a victory absolute though gradual. To force himself once more upon Stafford was not hard. To insist upon being tolerated and endured against the will of his new acquaintance would have been an affair almost brutally facile. But Brookstayne managed to carry his point with airy yet stringent diplomacy. He played, however, no purely cold-blooded role. The humanity in him had been touched, apart from all aims that altruism could not necessarily share. He contrived that their next meeting should seem the very random flower of accident; again, having discovered that Stafford cared to read diverting French books (when his enfeebled sight allowed him to read at all), our benevolent plotter managed to fall in with him just after finishing a new novel by Daudet, which was drawn from an opportune pocket, in the midst of warm critical praises. There was a big jump, surely, between eulogizing the book and afterward reading many pages of it aloud to Stafford in his clean, prim, white-curtained little chamber; but even this last remarkable coup Brookstayne finally accomplished. An actual friendship between the two men now began to grow and thrive. Still, for a long time Stafford's reserve continued impregnable regarding his own past. Perhaps the first words that he volunteered on this head related to the Swiss woman, Hilda, who had accompanied him hither and left him in the home of her parents.

"She is at Berne," he said. "She has been very faithful. She was my mother's maid for a number of years, and my own nurse when I was a little boy. It was her idea that this trip across the Atlantic, ended by a long stay in Switzerland, would help me to.. to bear what had happened. I have only to write and she will come to me from Berne. She is with a sister of hers who lives there,—a married sister, whom she loves very much, poor, sturdy, true-hearted Hilda! These old people are very good to me. I think Hilda understood that even her kind presence now and then troubled me a little. And her parents are mere amiable shadows; I dare say she has instructed them as regards their deportment; it is the perfection of discreet silence."

"Ignorance and discretion sometimes look wonderfully like one another," laughed Brookstayne.

"Oh, I suppose ignorance has a great deal to do with it," he replied. "But, whatever its origin, it is highly satisfying. I imagine that some of these old Swiss peasants have mastered the secret of perfect domestic peace. But then they have the calmer temperament, the cooler heads, unlike so many of the other European peasantries. I recall, in the case of Hilda, how forethought, prudence, and self-rule always predominated with her. I observed that in the midst of my worst sufferings, both mental and physical."

Brookstayne felt his pulses throb a little faster. This was but the second direct allusion which had thus far been made by the sombre hermit to his own woeful condition. Still, Stafford's auditor did not wish to seize the present chance too roughly, lest it might slip away from him like the shy head of a turtle into its shell.

"She was then so capable a nurse?" he asked, seeking to make his tones quite ordinary and zestless.

"Indeed, yes. I shall never forget her courage and skill, her strength and patience."

"All that was needed, no doubt," Brookstayne ventured.

"Needed? I was at death's door for weeks. It amazes me, now, that I should ever have recovered."

"And the accident was...?" began Brookstayne. Then he paused, leaving his question thus bluntly incomplete. "Pardon me," he went on, with a soft dexterity which the other perhaps quite failed to fathom; "I may have no right to inquire at all concerning your misfortune; you have not yet authorized me to do so."

He watched, with not a little secret anxiety, the single alert and luminous eye in that sadly ruined face. Plain rebuff might quickly manifest itself, and afterward a most depressing 'no thoroughfare' as regarded all further disclosures.

But he was mistaken in his fears. "I did not think to tell you or any one how I became what I am," he said. "And now, if I should give you even the slenderest explanation I would be dealing you an almost cruel shock."

"There you are mistaken," affirmed Brookstayne. "You would only be adding to my sympathy, which is already great."

Stafford bowed his head. "Ah, there is something about you that tempts my unrestrained candor," he murmured. "I never thought to let a living soul know, between the hour of my recovery and that in which I died! I believe that hour is not far off... and yet, pshaw I what man can be sure of the real summons? I've reason to long for, to crave mine,—God knows I have!"

Brookstayne realized that he could be bold, now. "You must have suffered unspeakably," he said. "I long to have you acquaint me with the cause of your suffering!"

Stafford touched the forlorn side of his face with a light, vacillant gesture. "You mean... this?"

"I mean whatever you choose to tell me."

He rose from the chair in which he had been seated, close to Brookstayne. It was a lovely day in latter August, and the dimity curtains at the quaint little dormer-shaped windows were swaying ethereally in the fresh Alpine breeze. He looked all about him, for a moment, in a dubious, insecure way. Suddenly he came very near to Brookstayne, and with a movement which his observer had learned pitifully to explain, he made only the unravaged part of his countenance apparent.

Then he stooped down a little, still with the same evident concealing design, and spoke a sentence or two in brief, hard undertone.

Brookstayne rose flurriedly. "No!" he exclaimed. "It was that? Really! How horrible!"

"There," Stafford answered; "I knew I would shock you! Shall I say anything more? Better not... better not!" And he flung himself into his chair again.

Thrilled as he was, Brookstayne bent over him and gently said, "Such an occurrence was indeed dreadful. To have an angry dog tear your face in that way! What a hideous outrage!... But while I recognize the full ghastliness of the accident I—I confess myself surprised—excuse that expression—I—I hardly know how to explain just what I mean..."

"You thought," Stafford broke in, as his companion hesitated and stammered, "that I had some less vulgar mode of explaining the wretched injury."

"Less vulgar?" Brookstayne repeated. "No,—not that. And yet..."

"And yet it robs my story of whatever romance you might have fancied concerning it."

"Romance," faltered Brookstayne; "yes. And still-"

"Ah," interrupted Stafford, with a ringing melancholy of voice, "but you have not yet heard my story."

"I wish to hear it; I wish to hear it very much," said Brookstayne. At the same time he was thinking, 'A dog tore him to pieces. How prosaic!—though still a love-affair might somehow have lain behind the calamity, as I suppose there did! It had grown to be almost a marriage, or something like that, when the dire thing took place.'

"If you wish to hear my story," Stafford soon went on, "I will give it you."

"Thanks."

"While we have talked together, of late, you may have noticed that I have shown some knowledge of science,—that the feet of you yourself being concerned with scientific pursuit has in a measure drawn me toward you."

Brookstayne replied without hesitation, "Yes. You have made many inquiries, all of which caused me to feel sure of your familiarity with data and developments I should not have suspected you of knowing."

There was a slight pause. Then Stafford said, "I know more than you have guessed,—or even dreamed. I have followed everything that you have uttered, and often feared lest I should betray an erudition that might startle you.... But there is now no further reason for concealment. There is nothing you know which I have not long ago known and digested. There is much I know which would be of inestimable worth to yourself."

'His hallucination!' thought Brookstayne, recalling the words of Hans. Aloud he said, with soft vehemence, "I do not deny your statements. How can I do so without proof?"

"You shall have proof,—great, incontestable proof," came the response, "when you hear why this awful wound curses me...."

AT length Brookstayne did hear the whole wild and amazing tale. It is not averred of him that he ever actually credited it. Days elapsed before he could win from Stafford avowals definite enough to make him accept points and explanations of a sort that related to pure scientific discovery, and even then he rejected certain postulates with the hardihood born of a sceptic's personal surety.

The narrative which he heard was never afterward put into manuscript form, as far as correct annals have recorded. It may have been that through some oath given to Stafford he refrained from ever transcribing or imparting it in its clear entirety. But that he somehow and somewhere repeated it allows of no question. It has come to the present chronicler in a biographic form, and thus it will be made known to the reader. It is a tale which has floated about, for a number of years, among a particular set of credulous, imaginative, or romantic-minded people. What Brookstayne (who has been living in Germany for a long time past) would say to it in its present shape, one might not readily conjecture. Perhaps he would damn it as the idlest of exaggerations, or affirm, on the other hand, that its verisimilitude was but faint of coloring beside the original facts. Assertions have reached me that he has more than once denied ever having met so afflicted a creature as Stafford, apart from having bruited abroad those appalling statements which the reader is now asked to consider. But such declarations are the mere pyrotechnics of doubt; for there is a flamboyant kind of distrust in the world, precisely as there is a bovine sort of bigotry, and certain people are never so happy as when informing us, with very sober countenances, that the grass is not really green and the sky not really blue.

HIS full name was Kenneth Rodney Stafford. All his early life was passed in a large, quiet old New England homestead, among the fascinating hills of Vermont. When a boy he was very beautiful, but with a decidedly girlish look. His mother, who adored him, cut off his long, thick golden curls because he yearned to lose them, although she performed the task with great regret. He was her only child, and his father's death occurred while he was yet almost an infant.

"I hate so to do it, Kenneth," she said, with the scissors in her hand. "Why should you care if the boys in the village do call you 'missy' and 'girl-boy'? You've quite as much manliness as they, and..."

But Kenneth made stout interruption, just here. "I do care, mamma," he said. "Please cut them; you promised me you would. Cut them quick, and let us get it off our minds!"

Mrs. Stafford smiled and obeyed him. He was only eight years old, but already she had begun to find his will in many ways paramount to her own. She was, herself, an excessively gentle lady, with a figure lissome as a willow-stem, gray-tinged auburn hair that rippled back from a brow of alabaster chastity, and the whitest and most delicate hands in the world.

But just as she had finished what she held to be an act of mild outrage, her sister, Miss Aurelia Rodney, entered the room and surveyed the suddenly-altered Kenneth with a harsh little grimace.

"I hope you think you've improved the boy, Margaret!" exclaimed Miss Aurelia, with a little adverse toss of her small, sleek head. "He looks more like a girl, now, than ever,—only, like a girl who plays marbles with the boys and keeps a top hidden away among her dolls."

Kenneth bit his lip, at this. He and his aunt Aurelia were not good friends, even at that early period of his life. He had no language in which to define her, but if words had been given him he would have pronounced her a posing sentimentalist.

He would not have been very far wrong. "Poetry" was often at the tip of her tongue, but there was a slight enough hint of it in her appearance. Years the senior of her sister, Mrs. Stafford, she was a spinster of spare and angular shape, with a severe little gray eye and a pair of lips thin as the blades of a knife. She had, however, a most expansive imagination, a most exploring and fetterless fancy. She had once been passionately religious, but of late had turned her attention to certain speculative "fads" and "isms." Her sister bore with her, deplored her, often quite failed to understand her, and always clingingly loved her.

Kenneth passed through childhood, there in his placid country home, with augmenting disapproval of all that his aunt Aurelia did, thought, or said. The boy, notwithstanding his feminine look, was full of pluck and fire. He rode fearlessly, and laughed at any danger that was wed with sport. He soon showed keenness of intellect, and surprised his governess by large powers of memory. She who discharged that office was none other than this same aunt Aurelia, and between the two a kind of dull, covert, stubborn war was forever being waged.

"The boy is born without any imagination whatever!" Miss Aurelia would lament. "I never saw a child so stolidly matter-of-fact. The other day I told him that invisible angels were always near us, and he wanted to know if they brought lunch-baskets with them when they came to spend the whole day down here, so far away from heaven. Did you ever hear of anything so blasphemous?"

"I don't believe he meant it to be so, Aurelia," said Mrs. Stafford. At the same time she secretly sighed. She was thinking of her late husband, whose audacious radicalisms had not seldom pained her own meek orthodox spirit.

One day Kenneth came to his mother with a little red spot on either of his delicate cheeks, and with a spark of droll arrogance in his fine clear eyes.

"Aunt Aurelia can't teach me arithmetic any more," he said. "She doesn't know how."

"Why, Kenneth!"

"It's true, mamma. She doesn't understand fractions at all. She has to look in the book and study the rules; and this morning I caught her in a big mistake."

Here was open contumacy indeed. Kenneth faced his aunt, a little later, with this awful charge, and at last the affair ended by Miss Aurelia bursting into vexed tears and saying to her sister that she would no longer dream of teaching so saucy and disrespectful a pupil.

"He is full of the most unbecoming pride," she complained. "He shows it to you, Margaret, but your love blinds you so that you either cannot or will not see the truth."

"I'm as fond of mamma as she is of me, every bit!" cried Kenneth; and, with a challenging glance at the kinswoman who roused his dislike, he threw both arms round the neck of his mother.

Miss Aurelia turned away with a shrug of her thin shoulders. "Some day," she murmured, in tones of sibylline affront, "you will be sorry, Margaret, that you ever tolerated his whims and follies."

A little later, when his aunt was absent, Kenneth said to his mother, "Don't most people think Aunt Aurelia a lady that makes herself out ever so much wiser than she really is?"

"Kenneth," sprang the reproving answer, "what put such a naughty fancy into your head? Of course nobody thinks anything of the sort."

"Well, I think so," declared the boy, with a funny gruffness.

From that period the tuition of Miss Rodney ceased. A gentleman was summoned from New York to be Kenneth's tutor. He was a person well past fifty years, with a bristly brown beard, chronic green glasses, and a manner which Miss Aurelia at once pronounced bearish.

But he swiftly won Kenneth's liking. No doubt for this reason Mrs. Stafford, whom his lack of suavity also repelled, both endured and smiled upon him. "How does my son progress in his studies?" she inquired about a fortnight after the tutor's installation. "I have been hoping, Mr. Apsley, that you would give me some kind of favorable account."

The grim tutor rubbed his rough beard with one rather dingy hand. "He's deficient in some things," was the bluff response. "But not from want of ability. Bless me, no! He's been horribly taught,—abominably, in fact."

"Ah," murmured Mrs. Stafford, in furtive thankfulness that her sister was not present; "that sounds discouraging!"

"But in some ways," continued Mr. Apsley, "he astonishes me. He has a most extraordinary mind. I'm a good deal mistaken, madam, or your son has got it in him to make, if he chooses, a really great logician and mathematician. I've never before met a boy of his years whose understanding could pierce through sham and reach certain plain, hard facts with so much ease and speed."

His father, again,' thought Mrs. Stafford. Tenderly as she loved the memory of her husband, she could not forget how often he had shocked her of old by the ruthless vigor with which he had tilted against this or that so-named fallacy and illusion.

In these boyish years of Kenneth's he was called upon to suffer one sharp, self-humiliating sorrow. Not more than a quarter of a mile away from his own home stood the handsomer and more modern residence of his mother's third- or fourth-cousin, Mr. Rodney Effingham. This gentleman was a widower, with one child, a little girl called Celia, about three years the junior of Kenneth. Celia was even then a beauty, with big, dark eyes and captivating dimples. Kenneth would sometimes be taken to visit her, or would sometimes (when leisure from studies allowed him) go alone. He preferred the latter mode of procedure as age advanced with him, because of its more manly look.

But, alas! he might have spared himself all such ambition as that of ever appealing to Celia through the medium of manliness. Her graceful head, with its dark, mutinous curls, would poise itself haughtily on her little white throat while she surveyed him. She thought him the most tryingly odd boy to behold! It was like seeing a girl in boys' clothes. Celia felt sure that she would look a great deal more like a boy if she were dressed as he was. Now and then her red lips let him learn this, unsheathing the milky teeth behind them in that merciless mockery a child's laughter will sometimes wear. For Kenneth her blundering little shafts were tipped with a venom which no other satire could have equalled, and went fleeting home to their mark with fearful accuracy.

But there was another form of his misfortune which he found harder still to bear. Celia's contempt for his effeminate face and figure was odious indeed, but when it became coupled with the scorn of an ally, and that ally an urchin of about his own years, tolerance forgot the virtue of stoicism. Celia had even then another admirer, though by no means as devout a one as Kenneth. Young Caryl Dayton was the son of a wealthy Bostonian whose large estate adjoined that of the Effinghams. It was a noble amplitude of acres, and a sort of castellated gray-stone mansion rose from it which the country-folk round about regarded as an abode of baronial splendor. The Daytons were social new-comers in Boston, and the fortune made by Caryl's father had been one of those rapid growths which were quickly amassed from the shady and shabby railroad enterprises that interested our national Congress and Senate somewhat disreputably from fifteen to twenty years ago. Caryl had brothers and sisters older than himself, who held their heads high as adults; and he, as a youth just bordering on his teens, followed their supercilious example. He was a tall, vigorous fellow, with light-blue flashing eyes and a mouth whose childish yet resolute curve too often evinced an unwonted worldliness and cynicism.

Almost from the first moment that he and Kenneth met, the latter detested him. Celia, who rode dauntlessly on her shaggy little pony, showed herself flattered whenever Caryl rode at her side on a fine thoroughbred out of his father's well-stocked stables. But Caryl was not a good horseman, and one day Kenneth felt a thrill of wicked delight when he chanced to join Celia and her companion, he himself being mounted on a stout-limbed, hard-mouthed horse apparently beyond his feeble powers of control. Kenneth could manage his own steed adroitly, notwithstanding his frail build and slim wrists, while in the course of a mile or so Caryl's horse suddenly shied and threw him. A few minutes before this, the millionaire's imperious son had murmured a few disdainful words to Celia, whose import partly reached Kenneth; and so, when the disaster overtook his rival, the heir of the Staffords could not resist a secret exultant glow. Still, he behaved very well, and at once dismounted after the accident, tying his horse by the bridle to a near sapling and doing his best to stanch Caryl's bleeding forehead, though the hurt soon proved to be the merest surface-wound.

Caryl had shown disarray and alarm, at first. His horse had dashed at a skittish gallop completely out of sight, but he paid no heed to this feature of his overthrow. His injury had dizzied and shocked him, and, while Celia broke into sympathetic plaints, Kenneth behaved with the nicest coolness and good will. But very soon Caryl became his old pert self. He almost threw Kenneth's proffered handkerchief in the latter's face, and presently walked away in the direction that his fugitive horse had taken, with a sulkily clouded brow and a churlish growl of annoyance.

Kenneth, after this repelling treatment, grew to be the sworn foe of Caryl. They met several times afterward on the lawn of Celia's dwelling. Twice or thrice the father of Celia happened to be present, but at last there came an afternoon when one of Caryl's most insulting humors overtook him, and then, as it chanced, the three children were alone together. They were playing croquet, and Kenneth alone knew how to treat the game with other than the merest hap-hazard stroke. But Kenneth did nothing at random; he had long ago shrewdly seen that blind force is the idlest of spendthrifts. Caryl gnawed his lips at having been badly beaten a second time, and no doubt the cut went deeper because he had had Celia for his partner, Kenneth playing against them both. But now Caryl asserted that their foe's game was not half so difficult as their own. "To manage two balls, as you did," he grumbled, "is a good deal the easiest way."

This, under the circumstance, appealed to Kenneth as the worst freak of silliness. "Why, you told Celia how to make all her shots," he said,—"and she made most of them very well, too. But, if you prefer, I'll play against you with Celia, and you can take the 'dummy' just as I did before."

The alacrity with which Celia acceded to this idea may have ruffled Caryl still further. The little girl was to-day in one of her most coquettish moods, and chose either to feel or affect pique at Caryl; it may have been that she wanted him stoutly to oppose Kenneth's new plan and insist on retaining herself as a partner.

Matters turned out no more successfully for Caryl during the next game than they had heretofore done. Indeed, he was beaten somewhat more ingloriously. Celia applauded all Kenneth's brilliant shots, followed his counsels with a pointed eagerness, and exulted loudly in their joint victory.

"Well," suddenly exclaimed Caryl, with savage irony, "it is rather unpleasant to be beaten by two girls!" And then he laughed out his acrimony, shrilly and harshly.

Those were the last insolent words one boy ever spoke to the other. Kenneth flung his mallet on the dark-green turf and dashed up to where Caryl stood. He had little fists and frail arms, but he did not strike out at all like a girl. Caryl had got two or three blows full in the face before he could just master his poise. After this the pair were matched most ill, for one boy loomed robustly above the other, so that it became a fray alike droll and pathetic. But, though neither lacked pluck, Kenneth had the long smart of grievance to spur and goad him. He had science, too, of a sort that resembled his deftness at croquet,—empiric, perhaps, but showing plainly the drift of temperament, and that pugilism, like other forms of experience, had passed under his analytic survey. Caryl's blows were given with twice his antagonist's force, but they were parried, every now and then, with an unforeseen skill. Celia's cries rang out wildly as the blood began to stream from Kenneth's face. She ran shrieking into the house, and luckily found her father, who was about emitting it When Ralph Effingham tore the two boys apart, Kenneth had drawn nearly as much blood as his enemy, and showed twice as much disposition to continue the fight. It was a scarlet feather in Kenneth's cap that so big a lad as Caryl had fought him and not promptly triumphed. Though Mrs. Stafford put her son to bed pale and aching, several hours later that same afternoon, tidings of his prowess presently transpired everywhere throughout the neighborhood, and what scars Caryl Dayton wore during the next fortnight or so were widely proclaimed the badges of disgrace.

A year or two later the Stafford household began to spend each winter in New York. Miss Aurelia persuaded her sister to make this change. She had become devotedly attached to spiritualism, clairvoyance, mind-reading, and other like shams by which our poor human brains are sometimes duped. She had taken to weeping over Andrew Jackson Davis, and she read aloud to her patient sister profuse "trance poems" all about the "summer-land." But being near other spiritualists did not form Miss Aurelia's only reason for going to New York. Mr. Ralph Effingham, little Celia's father, dwelt there every winter.

EFFINGHAM had surely given his daughter none of her beauty. He was, indeed, a man with a chalky cheek and a viscous, ascetic eye, and was never in the best of health. As a young man he had had literary ambitions, amiably looked on by some of his patrician relatives and anxiously by others. But there was no cause for any alarm: the vulgar guild of letters did not prove zealous in seeking his membership, and perhaps he had never been vain enough to imagine that it would. He was apparently most modest about his own powers; you saw the tyrannous autocrat spring up within him only when he discussed those of others. A few generations ago he would no doubt have been a fervid religionist. It is not probable that to-day he was even much of a church-goer, but he had certainly plunged his spirit into idealisms of various phases, and went abroad among his fellows with a perplexed air of spiritual remoteness that must have seemed sadly incongruous among the New York drawing-rooms he frequented. After a little while, however, he ceased to frequent them; he had found in one of them a congenial sweetheart, a Miss Van Styne, whom he soon made Mrs. Effingham, It was thought a most proper match, for there was Knickerbocker blood on either side. But in a few years they were saying mournfully of poor Mrs. Effingham that the whole melancholy meaning of her brief marriage had seemed for her to become the wife of her husband, to bear him a pretty little golden-haired girl, and then prematurely to die. She certainly left no resigned and plaintless widower. Effingham now became more immersed in abstractions than ever before. If he had been a great poet some of his stanzas on his dead wife would have thrilled the world, for so much genuine grief went to make them. But as it was, his turn for verse took the form of what he would have told you remained the only verse worth writing at all,—the "natural," the "simple," the "spontaneous." If he had been a poor man there is little doubt that he would have become a critic and controlled a column or two of some newspaper in which all the minor bards, from Cowley to Barry Cornwall, would have been besieged with eulogy, and all the living ones who stood even a faint chance of immortality through the sustained and academic excellence of their work would have been either covertly satirized or openly abused. But Effingham's wealth prevented, as it now happened, one more emotional trifler from entering the critical field. He employed the splendor of his clairvoyance in constructing lyrics that "breathed," as he expressed it, "an indefinable feeling." This elusive quality, he maintained, was at the root of all real poetry, and consequently, like every member of his irritating school, he placed security of artistic touch below a kind of daintily devil-may-care naiveté. Among modern poets he held Tennyson to be ornate and Longfellow mechanical. Certain metrical hysterics of the late Sidney Lanier he thought entrancing, and the worst things that Mr. Browning has written he found "packed with soul." As for his own compositions, they were apt to run somewhat like this:

I stood on the headland and listened

To the warring of waters below:

In my heart was an infinite sadness

More deep than the sea's ebb and flow.

I said to the cloud sailing o'er me,

"O light-hearted roamer, God-speed!"

I said to the swallow, "Be joyful;

Thy wings from all bondage are freed!"

And the cloud and the swallow went past me,

And I stood on the headland alone,

In my heart all the sea's rhythmic rapture,

Yet all its mysterious moan!

But to write such verses never has meant or can mean more than

the possession of a graceful facility. Effingham's trouble was

that his nature preferred the flickering rays of a candle to the

steadfast light of stars. He was too feverish, too feeble, and

too shallow a personality for the grand repose of true poetic art

not to strike him as "stilted." He so disastrously confused

thought and feeling that his mentality might be compared to the

gaudy tangle a girl's workbox will sometimes present, after her

favorite cat has been intermingling silks with worsted: His

metaphysics and transcendentalisms had affected not a few of his

old friends repellently. But they did not so affect Miss Aurelia

Rodney, who doubtless blended her choicest smiles with a lurking

recognition of his eligible widowerhood. It was because of

Effingham that Aurelia induced her sister to winter in New York.

Kenneth, who was now growing up with that extraordinary speed

which almost deals pangs of fear to adults over-sensitive about

the flight of time, would regard these two elderly cousins as

though they were the odd denizens of another sphere. His fair

straight brows would crease themselves in a perplexity charged

with all the sarcasm of his own innocence while he watched his

aunt Aurelia in the company of her kinsman. It struck the lad

that they were both talking for the mere sake of hearing their

own strange words and phrases, and with no actual desire to reach

any real goal of truth. He could not understand people ever

talking like that. To listen and observe, in their case, would

sometimes give him resentful thrills. Effingham, who had admired

his courage that day on the croquet-ground, soon got cordially to

detest him. And still later, when Kenneth had definitely left the

crude bounds of urchinhood and when Miss Aurelia had abandoned

sentimentalities of a more general scope for the dives and

flights of spiritualism, affairs in the Stafford home-circle

assumed a still sterner aspect. Kenneth had succeeded in making

himself so odious to Effingham that the latter had informed

Aurelia of his disgust. "The boy should be sent abroad, or

somewhere, to school," he had said. "Caryl Dayton is now at

Geneva. The idea of Kenneth having the impudence to ask me

whether I can prove the existence of a spirit as I can—no,

as he can—prove the multiplication-table! Good heavens! one

can answer grown-up folk when they assault one with such

materialisms, but what answer can be given a youngster of his

years except to make him hold his precocious little tongue?"

"If he could only be made to hold it!" sighed Aurelia. "But he is not all to blame. His mother pets and humors him so. As for discharging his masters and sending him off to a boarding-school, there is very little chance of her showing that amount of discipline. No, I regret to say, my sister is too weak in her love." Here Aurelia sighed again and obscured those sharp little gray eyes of hers for a moment in their drooped lids. "But is not all love weak, Ralph? I can realize its lofty and sublime self-abnegations; I can comprehend how mysterious powers in the vast invisible world beyond our groping sight may give many a tender and subtle monition to some heart either doubtful of its own love or wondering if this be adequately returned by another; but, after all, love, as I grasp the idea of it, is an emotion, an impulse quite ungovernable,—and therefore weak, quite weak!"

And then Aurelia looked up into the rather dead eye of Effingham, while another very faint and fluttering sound passed from her lips. Perhaps her kinsman did not see the connection between this little rhapsodic burst and the fact that Kenneth Stafford needed either a good trouncing or a long sojourn at boarding-school, or both. And possibly this dubious mood was reflected in the brief, blunt answer received by Aurelia.

Still, as time went on, she managed to convince Ralph Effingham that brief and blunt answers were better left unspoken. Kenneth did not go to boarding-school, but profited by his mother's proud appreciation of his talents and acquitted himself finely under the care of the several different daily instructors with whom she provided him. Scientific study was now recognized and accepted as his strong point, and Mrs. Stafford, realizing that gifts remarkable as those of her son should be improved without stint, crushed down all futile regret and gave him every rich chance for their ample culture. She would have preferred, poor lady, that Kenneth should show something of that ideality which might have made him less fond of the bare, rigid fact and more submissive to even the most illusory spells which environ it.

But Kenneth grew hardier, month by month, in his rationalistic tendencies. His passion for pure science augmented, and the spiritualism which his aunt Aurelia began to cultivate roused in him a scorn often defiant of civil usages. At last there came a period, during his residence in New York with his mother and Miss Rodney, when merely for him to know that the latter attended séances and spiritual meetings provoked in him a sombre zeal of challenge. His aunt had more than one fit of tears over his placid gibes and scoffs.

"That boy would fling Easter-lilies to swine!" she once vehemently told her sister.

"Not unless they were a proper article of diet for those animals," replied Kenneth, who chanced to enter the room just then and to catch in full this picturesque aspersion. "I should lay a strict veto on the lilies if they had any bad effect on the character of the pork."

Mrs. Stafford laughed nervously. "Ah, my son," she said, "that is just what your aunt means,—that you would always be thinking more of the pork than of the lilies."

"One helps us to live," he retorted; "the others merely decorate life."

Not very long after this a medium was introduced by Aurelia, one evening, into the abode of her sister. Kenneth, whose hostility and sarcasm had alike been dreaded, surprised both ladies by conducting himself with thorough politeness toward the new-comer. She was in the drawing-room, talking with his aunt and Effingham, when he appeared there at the side of his mother. She looked to be a person somewhat past fifty years, and wore above her stout bosom a huge enamel brooch bearing the face and half the form of a gentleman with a stock and a capacious collar. She might have seemed passably pretty if all her hair had not been drawn back from her brows and temples with excessive tightness and tied into a severe little knob behind, making her glazed chestnut head strike Kenneth as oddly like an acorn deprived of its cup, and rounded off, so to speak, by the insertion of a human face. It was not a very happy face, either; it had a restless, uneasy expression; and very soon after Kenneth and his mother came into the room it grew still more troubled.

"I kinder feel as though there was antaggernistic influences to work," said the medium, answering an earnest request of Aurelia's that the séance should begin. "I guess we won't have much of a seeunce tonight. Things ain't right, somehow."

Aurelia stole a side-glance at Effingham, to see how he stood such lawless orthoepy and syntax from even the "child of nature" that she had already described her priestess of a new faith.

"Oh, Mrs. Gallup," she then said, with blended conciliation and persuasion, "I'm sure it will all turn out splendidly when it once begins. You had such success at your own rooms, the other evening, that can hardly realize how to-night can prove a failure."

"Goodness me!" said Mrs. Gallup, with a shake of the head that seemed to imply vast hidden plenitudes of wisdom, "if the conditions was only always alike I'd never be afraid of disappointing a soul, and reg'late all my doings jus' by the amount of psycher-ma'netic fluid I was able to receive at every seeunce."

"What do you mean by psycho-magnetic fluid?" asked Kenneth, with a sudden curtness.

The youth sat with his hard, bright eyes on her face and his lip unconsciously curled. He was not far from early manhood, now, and although there was a boyishness in his look which until old age came he could never wholly lose, there was still a good deal of high-bred beauty and not a little delicate dignity as well.

"There!" exclaimed Mrs. Gallup, suddenly pointing her finger at Kenneth, "it's you! Young man, I couldn't no more tell you what that psycher-ma'netic fluid is than you could tell me who and where Gord is! I jus' know it kinder comes a-flowing and a-flowing all aroun' me" (here the lady made undulatory movements with both hands), "and then it's—we'll, then it's time!" She beamed upon Miss Aurelia with a sudden smile, after giving her sentence this abrupt end, with its ghostly intimations. "You understand me, o' course!"

"Oh, yes," said Aurelia, with a repressed fervor that hinted of freer speech when her present auditors had been absent; "indeed, Mrs. Gallup, I do!"

"It's him," pursued the medium, once more pointing at Kenneth. "That young man's a septic, and he's spoiling the conditions. I felt he was in the house as soon as I come into it."

"Does that mean you'd like me to go?" asked Kenneth, with a tantalizing repose.

Mrs. Gallup gave him a sullen stare, and then turned toward Aurelia with another exorbitant smile. "'Tain't for me to say who shall be at a seeunce when I'm engaged to give one."

"Still," persisted Kenneth, with his calm, bell-like voice, "you think you could humbug everybody here a good deal better without me. You're afraid I might see through some of your shams if I stayed; though perhaps I might be equally dangerous if I left the room. As it is, I intend to stay." He reached over for his mother's hand and took it in both his own. "When my mother goes into the company of such brazen frauds as all you people are, I go with her."

Under the circumstances (as will be seen hereafter), this was a most reckless little gauntlet for Kenneth to fling down. But youth and impetuosity are seldom other than twin terms. However he may have regretted them a few seconds after they were spoken, no power could then unsay them.

Just what he did not desire to have occur now took place. Effingham sprang up from his seat with a disgusted sniff. Aurelia threw both her hands toward the ceiling, as if she wanted to invoke some sort of celestial ire upon this perverse young desecrator. As for Mrs. Gallup, she was seized with a fit of trembling and whimpering that threatened to finish in hysteria.

But it did not. The stance was to be paid for by a fat sum out of Mrs. Stafford's pocket, and here may have lain the secret of that fine composure which soon replaced the medium's disarray. His mother had softly implored Kenneth to offer some kind of apology, but this he refused to do, sitting with his graceful head obstinately thrown backward and a stern resolve on his tender, boyish lips. Effingham now and then shot looks of disgust at him, but Aurelia wholly occupied herself in salving Mrs. Gallup's wounds.

The latter presently recovered with an almost startling expedition, and told Kenneth in tones of sullen wrath that she would try and let him see whether she was the brazen fraud he had been impudent enough to call her.

"Go ahead, then," returned Kenneth. "I'll take back what I said about you when you've proved to me I was wrong."

"Bless my soul!" murmured Effingham to Aurelia. "Only think of such talk from a lad of his age! If I had a son like that I'd soon show him the meaning of manners."

"For his own sake, poor boy," Aurelia murmured in response, "I do wish that he had been your son!"

And meanwhile, in a low voice, Mrs. Stafford was saying to Kenneth, "Oh, my boy, how ungentlemanly has been your conduct I And under your mother's roof!—your own roof! Ah, with all your past fits of willfulness, I never believed you would come to this!"

But Kenneth merely gave a chill smile and lifted his head a little higher. His dislike of Mrs. Gallup had not been personal. He loathed, as if through indomitable instinct, all that she represented. This detestation of every alleged claim to wield occult and necromantic powers formed a sort of corollary to his reverence for the firm exactitudes of science.

The stance began soon afterward. It was held, of course, in a darkened room. Earlier in the evening Aurelia had spoken, with tones of expectant rapture, regarding the blessed chances of a "materialization." It seemed as if Mrs. Gallup might be so favored by some of her spiritual allies as to produce one, and a very handsome specimen of its grisly kind as well; for in the almost pitchy darkness that now filled the room she suddenly said, with a voice of hollow resonance,—

"Margaret Stafford, your little girl, Elsie, that you lost years ago, is a child o' light now, and would like to let her ma see what a 'cute and sweet little dearie they've made out of her, off there into the summer-land."

Mrs. Stafford started, and shuddered audibly in the gloom. Her first-born, Elsie, had indeed died years ago, but the wound of that loss had never wholly healed, as so many a mother will understand. But her sensation was not only one of pain; terror mixed with it. She stretched out one hand gropingly for Kenneth, who had been seated next her at the lowering of the light. But she could not find him. Where had he gone? She had not heard him leave his chair. "Kenneth," she called, in a low whisper. No answer came.

"How... how marvellous!" the voice of Aurelia was now heard to quiver. "I never dreamed of mentioning poor little Elsie's name to Mrs. Gallup."

"I think we'd better be quite quiet, hadn't we?" said Effingham.

There was a silence, during which Mrs. Stafford's terror grew. She felt like screaming her boy's name aloud. If the little dead one were to come back, she wanted Kenneth near by; he had somehow got to be so strong and big, of late; and then she wasn't ever at all sure, nowadays, about her feeble nerves.

"I guess little Elsie'll come," at length proclaimed Mrs. Gallup, though with the effect of a person who talks in sleep. And then, in a monotonous, droning whine, "Come, little petty... come away from them heavenly blooms and birds you're a-playing among; come here for a little while and see your own darling mommer, that ain't forgot you yet, nor never can."

For the mother who heard them these nasal strains might have been the rarest euphony, while it is doubtful if she even noted the raw vulgarity of their appeal. The longing, the agitation which they roused had slight concern with their tone, their taste, or their grammar. Like many religious people, she was easily impressed by just such quackeries as the spiritualist, the occultist, the theosophist, the Christian scientist, or whatever he may choose to call himself, may care to deal in. She stretched forth her yearning arms as a vague light stole through some sort of aperture yards beyond. Slowly the rays increased until they made one broad shaft on curtain and carpet. And then, suddenly, but with no more sound than the coming of the light itself, a small shape, clad in white, with a lovely childish face and a pair of lifted arms, glided into view.

Sobs broke from Mrs. Stafford. "My child! my Elsie!" she exclaimed.

"Hush!" said Mrs. Gallup, with a dreadful solemnity.

"Hush, Margaret!" gasped Aurelia.

And now Mrs. Stafford's imagination went wildly to work. She distinctly recognized the child whom she had lost years before. She had not a doubt but that her own dead little Elsie stood in spectral beauty just yonder. A cry—an eager maternal cry—trembled on her lips, when the swift darting from shadow of another shape stilled it. A moment later she saw that Kenneth had seized the child. Then there came a shrill, babyish scream, and some one rushed toward the chandelier with its turned-down gas-jets, making each, in quick succession, burn again mercilessly bright.

There stood Kenneth, near the drawn portière of the adjacent dining-room, with a laugh of terrible scorn that drowned the affrighted wails of the child he was holding. But he held it very tenderly, and almost at once, after the spectacular éclaircissement (which had been wrought by none other than Luke, an old butler long resident in the Stafford family), he brought the dismayed little girl over to his mother, saying, with clear, vibrant voice,—

"There, you see she's only somebody else's flesh-and-blood child, after all! Kiss her and hug her all you please, poor little frightened thing. She deserves it for being made the tool of that wretched old mountebank there!"

He turned to Mrs. Gallup as he spoke the last words, and contempt flashed from his ardent young eyes, glad with the joy of a complete victory.

Soon afterward, to the humiliation of Aurelia, every detail of the real truth transpired. Kenneth had heard from Hilda, his mother's devoted maid and his own former nurse, certain words which had caused him to suspect that Mrs. Gallup had been trying to corrupt one of the other female servants. Whatever may have been the medium's triumphs at private residences in previous times, her vicious arts had failed her in the present instance. She had bribed too much or too little; the maid whom she had insidiously approached had betrayed her, and Kenneth, with his hot young soul aflame for the exposure of charlatanism, had not found it hard to enlist on his side the Swiss woman, Hilda, who adored him, or the old Irish butler, Luke, who held him in devoted esteem.

Mrs. Gallup went away crestfallen and feeless. Kenneth had proved himself a power against which the innuendoes of his aunt and the morose mutterings of Effingham were alike futile. His mother clung to him more than ever after that night when he had so pitilessly yet with so austere a kindliness brought to her side the little guiltless, hired minion of Mrs. Gallup's detected chicanery. In spite of his youth, Kenneth now became the real head of the household. Even Aurelia bowed to him, with no more muffled complaints against his "cold-bloodedness" or "lack of sentiment." But his reign as acknowledged autocrat proved, nevertheless, a brief one.

ONLY a few months later Mrs. Stafford, whose health had not for years been strong, suddenly sickened and died. Kenneth was overwhelmed with horror and loneliness at her demise. It changed him for a long period. He would scarcely see or speak to one of his tutors; there were moments when he meditated suicide.

The news of his aunt's prospective marriage with Effingham woke him into comparative action. He disliked them both, and appeared at their wedding in deep mourning, scarcely uttering a syllable. Soon afterward he made up his mind to go abroad, and as soon as his financial affairs could be arranged according to the terms of his mother's will, he departed for Europe. Mrs. Stafford had been rich in her own right, and had left certain amounts to religious charities. Kenneth paid over all these sums, and found himself afterward possessed of a large fortune, the heritage of both his parents.

Reaching Europe, he went almost directly to Germany. He knew his own ignorance, just as he was perfectly aware of his own exceptional attainments. He gave himself in the humblest spirit up to the instructors of the Berlin University, and soon became aware that an enormous amount of study waited between his ambitions and their potential span. But he was prepared to shirk no height of toil, and in his later career as a student of science he won shining distinction. The new atmosphere tingled for him with a most welcome stimulus. Intercourse with congenial minds at first nearly intoxicated him by its delicious novelty. This life of the university, as he soon perceived, filled a yawning vacuum in his nature. He was now a living refutation of the cynical words "Tout nôtre mal vient de ne pouvoir être seul." It seemed sometimes to Kenneth as if absolute solitude would henceforth become hateful; he forever sought an interchange of ideas with his co-disciples, and frequently dispensed to them on this very account entertainment which his well-filled purse made a light enough consideration. For such reason, and for others as well, he was popular. His freshness amazed and pleased everybody. He went about seeking knowledge everywhere and from all informants. "He is not a man," said one of the students: "he is a thirst." "No, an enthusiasm," preferred another. They called him kenntnisverrückt behind his back, and made amiable sport of him for his craze after knowledge of a certain character. But they all liked him for his fine simplicity and that species of courtesy which holds no man, not even the meanest, an unimportant factor in social forces. For nothing so flatters the ordinary human intellect as to become convinced of its own instructive value. The moment you make a fellow-creature believe that he can help you by information which at once costs him nothing and yet shows forth any of his own mental equipments, you have created an eager, if temporary, friend. And friends of this description Kenneth did create by the score. His drift was away from orthodoxy, and plenty of encouragement with respect to this mood awaited him at the Berlin University. He was confronted, indeed, with not a few atheists, who occupied their leisure in shaping dauntless and biting epigrams which sounded like shibboleths to be printed glaringly on the banners of some future rationalistic revolt. But he revealed no sympathy with this mode of destroying conservative tenets. He had a rooted and inherent distrust of eloquence, and it gradually grew upon him that oratory as an art was one of the most harmful enemies of civilization. The deeper he plunged into science the more potently he was convinced of how its lustral waters cleansed the mind from every form of parasitic and clogging impediment. "I live," he once announced to a throng of intimates, "in search of nothing except the actual. Progress has for centuries lost untold opportunities through her hospitality toward imagination. All dreams are a disease; the really healthful sleep has none. It has often occurred to me that mankind now suffers from an immense and distracting toothache, called religion."

"Are you going to invent a cure for that toothache, Stafford?" queried one of his companions, over their beer and pipes.

"No," said Kenneth. "But time will. They gave one of the mythic Fates a scissors; I would put into her hand a forceps, and have her pull out that' raging tooth! She's bound to do so sooner or later; she's tugging away at the nuisance now. When the entire world perceives that there is nothing to worship, it will comprehend that there will be nothing to feel afraid of,—not even death. For death, shorn of all ecclesiastic appendices, is really a most sweet falling asleep; and nature has prepared an annihilation of dusky yet enticing splendor. No gorgeous paradise of the Koran's most glowing pages ever equalled it. The dark slaves of oblivion wait upon us there; they are better than the loveliest houris; they can never be corrupted, for the simple reason that they are corruption itself."

"Aha!" cried one of his hearers, "you're a pessimist, then!"

"No," said Kenneth. "A pessimist is a rebel. I am a martyr." And he laughed a little. "I shall always believe in having the human race accommodate itself sensibly to the curse of consciousness."

That last phrase roused a roar of laughter from a certain clique of devotees at the grim shrines of Schopenhauer and Von Hartmann.

But Kenneth seldom obtruded his materialistic feelings. He nurtured them in silence, and with but few incidents of unreserved disclosure. They strengthened within him, however, as his course at the university continued. Year after year he reaped the highest honors. Electricity attracted him more than any other branch or science, and his environment gave him the best means for exhaustive researches. He was so rich that he could purchase the most precious instruments without a thought of their cost. Subjects that also keenly interested him were physiology and brain-structure in all their subtlest details. He was never tired of microscopic investigations with respect to animal tissue, nerve-cells, ganglia, cerebral mechanism. Our entire mortal coil, physical and mental, was a source of exquisite interest to him. He would spend hours before his microscope, gazing at bits of human brain-matter in which evidence of some lesion like paresis had shown itself. It was declared of him that he had the temperament and mind of a great physician, if he should choose to make medicine his cult. But once, on hearing that this had been stated, he shook his head and dryly answered,—

"Oh, no. Medicine is all a huge experiment. I prefer to know something."