RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

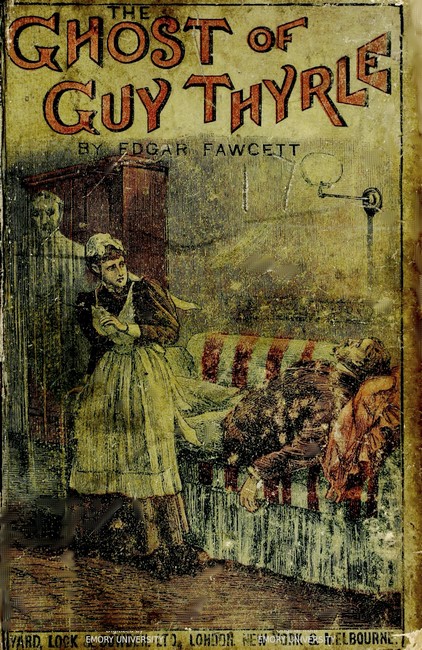

"The Ghost of Guy Thyrle,"

Ward, Lock & Bowden, London, 1895

"The Ghost of Guy Thyrle,"

Ward, Lock & Bowden, London, 1895

My Dear ———

Do you remember how you once called a few former tales of mine ("Douglas Duane," "Solarion," "The Romance of Two Brothers," and perhaps also "The Great White Emerald") ghost-stories pure and simple? I then declared to you that I had never written a positive ghost-story in my life; and now, when I send you my "Ghost of Guy Thyrle," I am obstinate in repeating this assertion. Here, as in those other works, you will discern no truly "superstitious" element. If certain readers choose to decide that Guy Thyrle's weird experiences were other than the coinage of Raymond Savernay's hallucination, it is not because I have failed to give them full liberty to form an opposite belief. Perhaps I am only a poor pioneer, after all, in the direction of trying to write the modern wonder-tale. It seems to me that this will never die till what we once called the Supernatural and now (so many of us!) call the Unknowable, dies as well. Mankind loves the marvellous; but his intelligence now rejects, in great measure, the marvellous unallied with sanity of presentment. We may grant that final causes are still dark as of old, but we will not accept mere myth and fable clad in the guise of truth. Romance, pushed back from the grooves of exploitation in which it once so easily moved, seeks new paths, and persists in finding them. It must find them, if at all, among those dim regions which the torch of science has not yet bathed in full beams of discovery. Its visions and spectres and mysteries must there or nowhere abide. Whenever we have spoken together of realism, my friend, you will recall how I have always held that a few polemic writers are not decrying the romantic, but rather the artificial. Romance is a shadow cast by the unknown, and follows it with necessitous pursuit. It can only perish when human knowledge has reached omniscience. Till then it may alter with our mental progress in countless ways, but the two existences are really one. Books like "Zanoni" and "A Strange Story" thrilled us in earlier years. Nowadays we want a different kind of romanticism, a kind that accommodates itself more naturally to our intensified sceptic tastes. It is the actual, the tangible, the ordinary, the explained, that realism always respects. From the vague, the remote, the unusual, the problematic, it recoils. Yet frequently the two forces of realism and romanticism have met, as in Balzac's "Peau de Chagrin," which might be called a fairy-tale written by a materialist. To make our romances acceptable with the world of modern readers, we must clothe them in rationalistic raiment. So clothed, my friend, I should name them "realistic romances"—stories where the astonishing and peculiar are blent with the possible and accountable. They may be as wonderful as you will, but they must not touch on the mere flimsiness of miracle. They can be excessively improbable; but their improbability must be based upon scientific fact, and not upon fantastic, emotional, and purely imaginative groundwork. From this point of view I occasionally strive to prove my faith in the unperished charm and potency of romance. What results I have thus far reaped may be meagre enough; but I am sure that your amity, despite such drawback, will permit the present effort to tyrannise, even as experimental failure, over your valued attention.

Sincerely,

Edgar Fawcett.

"RAYMOND should go abroad."

"He does look ill."

"It isn't that he's really ill, Vivien; he's come down here from Oxford in a state of nerves."

Vivien Savernay looked out on the lovely vernal lawns while she slowly stirred her coffee. "Oh, Cecil, he'll be all right in a few days. You've often said that the air of Storrowby worked wonders with him."

Raymond Savernay, as it chanced, overheard all this. He gave a soft laugh, which made his brother and sister-in-law discover him at the doorway of the breakfast-room.

"Oh, you dreadful eavesdropper!" exclaimed Vivien.

"I'm sure you don't think me one," he said. He was very fond of Vivien, and kissed her blooming young cheek for good-morning, as she lifted it to him in a way at once matter-of-course and bewitching. Then he nodded to his brother Cecil, and after that he went to the sideboard and got what he wanted and brought it to the table.

"Cecil's right in one sense," he at length said, breaking a silence. "I am in a state of nerves. But it isn't a morbid state."

"Oh, isn't it?" laughed Cecil, who was blond and ruddy, and looked the picture of a prosperous young Englishman. "Last night you sat up with me till midnight and told me all kinds of gruesome things. One minute I thought you believed in the immortality of the soul, Ray, and the next I thought you didn't. And, meanwhile, you smoked scores of cigarettes. I left Oxford only four years ago, and they didn't consume cigarettes there by the bushel then. I'm afraid dear old Balliol has been retrograding."

"Don't they believe everywhere at Oxford in the immortality of the soul?" asked Vivien, with shocked surprise. "I thought it was so orthodox."

"It used to be," said Cecil Savernay, looking at his brother.

"Oh, it is yet," protested Raymond. "My dear Vivien," he pursued, "Cecil finds me odd and droll because I'm passionately interested in the doings of the Society of Psychical Research. It isn't an Oxonian affair at all. It's something of an American origin."

"It sounds clever enough to be American," said Vivien. She had met certain New Yorkers, Philadelphians, Bostonians and Chicagoans, of both sexes, during her last London season, and, to use her own phrase, "swore by" them.

"I reminded Raymond," said his brother, "of the ghost over at Gowerleigh, and he immediately took out a little carnet and booked it."

"Did you, Ray? Did you?" cried Vivien, clapping her hands together in an ecstasy of amusement. "Oh, how delightful! Is that the way you must do when you belong to the Society of What's-its-name?—book all the ghosts you hear about? Please make me a member, won't you? We'll go ghost-hunting together."

Raymond, who was slender and pale, with large, soft, shadowy eyes, looked at his merry kinswoman in a pensively amused way.

"You forget, Vivien," he said, "that you and Cecil are going up to London inside the week. There, of course, are plenty of ghosts; but you'll never pay the least heed to them. You'll drive in the Park, and go to dances in Mayfair, and look in at the opera and the new plays. Perhaps the ghosts will do just the same; only you won't know it, and won't care."

"Ugh!" shuddered Vivien. "Cecil's right. You are in a state of nerves. We must take you with us to London. You're a great swell, you know; you've been graduated with such honours. You haven't got Storrowby, but you're more of a catch than Cecil was (don't scowl at me over your coffee-cup, Cecil), though you are a younger son, for your mother, Lady Adelaide, left you her estates in the south, and that big pot of money, besides; and we'll marry you (won't we, Cecil?) to the belle of the season."

"I sha'n't marry the belle of the season, even if she'll have me," smiled Raymond, in his musing manner. "And I'm not going to Devonshire for an age yet. I prefer the Midland counties; Illsley Park is a beautiful property; but I was born here at Storrowby, and I'm going to keep bachelor's hall here till the autumn; Cecil told me I could. Possibly I may run up to London now and then, though, and get a glimpse of you in all your fashionable grandeur."

"I don't believe you will," pouted Vivien. "You've got too sharp an eye on that ghost at Gowerleigh."

She said it without real meaning, and never gave it a second thought. Later, just before the townward trip, she observed to her husband,—

"He isn't himself, somehow. There are times when he's curiously tired. Do you know, I found him asleep on the great lounge in the morning-room yesterday, only an hour or so after breakfast? He woke with a sharp start, and stared at me for many seconds as though I were some one else. Then, with a heavy sigh, he said, 'I have had such a curious dream.'" Here Vivien's blithe mouth saddened, and she laid a hand on her husband's arm. "Cecil, since he won't come with us to London, dear, perhaps we'd better not leave him here all alone."

Cecil shrugged his shoulders. "Upon my word," he replied, "I believe that's precisely what would please him better than anything else."

AND Cecil Savernay was right. Not that Raymond had no family love; his young heart was, indeed, overbrimming with it. Vivien, to his eyes, was the rarest little wife in all England, and his brother the mightiest of good fellows.

But sometimes, when we know we are not in the best of health, we shrink from the vigilance and solicitude of those who are most dear to us. It was this way with Raymond. It seemed to him that a few weeks of lazy solitude here in Storrowby would work wonders for his jaded brain. He knew every turn of its Tudor symmetries, every tree on the fluctuant emerald of its lawns. A boy, he had plucked roses from the urns of its terraces; a boy, he had scampered on his pony through the rugged vistas of its oaks.

When Cecil and Vivien departed he bade them a most affectionate farewell. Would he join them soon in London? "Perhaps," he answered, and they both decided that the word was too dreamily and dubiously spoken.

What his brother had said of him was quite true. The question of human immortality had keenly interested him of late. There had been a time, not long ago, when its threatened mental absorption had made him fear he would not secure at Oxford the honours which afterwards were happily won there. As for the American movement, a sudden acute sympathy had caused him to give open signs of how he approved and endorsed it.

"I should like," he kept musing, "to send this Society of Psychical Research some important bit of personal experience. But nothing has ever happened to me that in the faintest way might go to prove there is really a life after death. Some of the dreams which have taken from my sleep the element of needed rest are beyond doubt marvellous. I seem to live another life in them, now and then. Their sanity, their verisimilitude, their pungent realism and actuality, are astounding. And yet the hard strain of recent study, there at Balliol, accounts for all of them. And in every case I clearly realise, on waking, that they are 'such stuff as dreams are made of.' It would be so different, I am certain, if any spiritual visitation befell me. Then I should at once be confident no mere cerebral trick had snared my understanding."

One delightful day, with a book under his arm, he strolled for nearly two miles, ending at the grey stone structure of Gowerleigh. The ivies had climbed sheer to some of the turrets' tops, he noted, since last he had seen this small but charming old residence, an almost perfect specimen of the early Norman style. He had got from the housekeeper at Storrowby a certain rather weightsome bunch of keys, which not only unlocked for him the main front doorway, but every chamber, as well, whose threshold he desired to cross. Everywhere through the interior order and cleanliness reigned. Here were the same tokens of careful tendance that one saw among the paths and carriage-drives and flower-plots outside. The bed-linen looked as though the smoothing hand of a servant had just left it; the window-panes were specklessly polished. Raymond remembered how his brother had long ago given orders that Gowerleigh should be kept in a condition of the most thorough culture and repair.

He opened a window in one of the largest bedrooms on the second floor. A gush of bland air set the snowy curtains fluttering. Beyond billows of greenery he could see the roofs of his childhood's home. He sank into a large, soft chair, and opened the book he had brought with him. It was not ill-written, for a work of its kind. It gave the experiences of a celebrated "medium," and teemed, for its reader, with the incredible. Still, its pages fascinated him, and he had a number of books like it, bought during the past year or two, which would often affect him with equal potency.

His intellect was of the imaginative class. Living a hundred years ago, he might have made an admirably reverential priest. But to-day modern scepticism battled with inherited belief. He might give up all doctrinal faith, but there was another residual surrender harder to achieve. And then a certain consideration, too, kept constantly haunting him, and formed the chief reason why he had been so enticed by such a motive as that evidently sheathed in the idea of a society for psychical research. He found it hard, at times, to credit the entire incredibility of all those marvellous tales, records, and experiences, which had managed to embalm themselves in literary form. Such a book, for example, as "Crowe's Night Side of Nature"—could its numerous, almost numberless annals, be in every case the mere product of fantasy, falsehood, and topsy-turvy rumour? Of course, in many cases, misrepresentation, mendacity, must have played their devil-may-care parts. But could this universally have been possible? Among such masses of fabrication must there not lurk at least a few glimmerings of truth?

And then he would recall the theogonies of the ancients—especially those of Greece and Rome. Had not time proved their complete falsity? Did not later definitions of them blend in declaring that all were vacuous myth? And yet how tremendous was their grasp, their sway, for centuries! To Jove, Juno, Diana, Venus, Minerva, how sincere was the tribute paid, and concerning them how intricate and subtle were the details of ceremonious worship! What, then, should a rationalist say of the countless "ghost stories" that nowadays challenged human credence?

Raymond Savernay presently ceased reading his book, and let his eyes roam about the spacious apartment where he sat. Possibly, he reflected, this, was the very room intended for that unhappy girl as her bridal chamber.

"Here," he thought, "would indeed be a ghost-story worth sending the Society. What a powerful contribution they might deem it if I could only mail them, over there in Boston, certain narrative disclosures quorum magna pars fuit And the whole reputed tragedy happened but a few years ago. How I wish that I had some sort of authentic data about this Gowerleigh Ghost! They say it appears to somebody as soon as people take the place and begin to sleep here. How ridiculous!—there's my modern agnosticism. How curious and extraordinary!—there's my inherent superstition. Was ever a man so cast about between two forces of feeling doubt and faith—as am I? Nevertheless, one mood remains immobile—a genuine hunger for some practical test. I should welcome that. Now that I'm alone over there at Storrowby, I could spend a night here without dreading Cecil's gentle sarcasms or Vivien's droll shivers."

Thus deliberating, Raymond looked from the near window and saw an amethyst sky overarch breadths of landscape, so green and yet so glistening that their pastoral undulations seemed like an incarnate troth-plight between earth and sun. Then he turned his gaze inward upon the placid chamber, and saw there nothing but peace, neatness, refinement, and a kind of domestic beauty, broodingly delicate.

"How incongruous!" he almost said aloud.

He was thinking, now, not of the alleged ghost at Gowerleigh, but of the actual tragedy once played there. And with one finger making a book-mark for the volume on his lap, he soon found himself recalling just what the facts of this mystic and momentous episode had been.

GOWERLEIGH had stood for many years the property of the Fythian family; but not long ago they had parted with it to Cecil Savernay. Its domain was not broad, but the Savernays had always coveted those acres, as a completion of what Nature herself had seemed to design for their own seignorial realm. When the chance came to buy, Cecil had bought. He had never meant to pull down Gowerleigh; this would have seemed to him an act of shocking vandalism. But after the purchase several different tenants occupied it, and all quitted it with the same complaint. It was haunted; it had a ghost.

Cecil always treated these declarations with scorn and hilarity mixed. "They mean the ghost of Guy Thyrle," he would scoff, "and they would never have dreamed of seeing it if the babble of village-folk, and of provincial newspapers, and probably of our own servants here at Storrowby besides, hadn't set their nerves nonsensically tingling. Very soon Gowerleigh'll become unleasable, with all this rot spreading broadcast. Well, let it. I'll keep it in decent order for my son on his wedding-day, if luck's good enough to make me the father of one."

And so, with a kind of jovial defiance, Cecil had gone on treating the fine edifice and its encompassing grounds quite as respectfully as if they were a part of his own abode. Raymond had always applauded his course; and while to-day he felt newly imbued with a sense of the loveliness and decorum that pervaded Gowerleigh, his approbation quietly deepened.

Musingly he reviewed all that either he or his brother knew of that uncanny Fythian story. Lord Henry Fythian, second son of the Marquis of Ullinford, had occupied the house when it all happened. There had always been a Fythian at Gowerleigh for Heaven knew how many decades back, and he had always been a younger son, or a cousin, or some sort of kin, to the living peer. This Lord Henry had married very late in life, and was an aged widower when his daughter Violet had passed her eighteenth year. He brought her out in London with something of a flourish; for she was pretty, had tea-rose colouring, and eyes like her name, and would get Gowerleigh, when her father died, and four thousand a year besides. During her second season Violet became engaged to a talented though not very popular young man named Guy Thyrle. Her father began by disapproving the betrothal, it was rumoured, though there is no doubt that, later, it secured his sanction. But suddenly, one morning, Guy Thyrle was found dead in his London home by Vincent Ardilange, a friend who had lived with him for some time, and whom he firmly trusted and dearly loved. Thyrle had been among the first to hail and applaud the modern idea of cremation, and Vincent Ardilange had produced a paper, signed by the deceased and dated several years back, in which, besides its acknowledgment of membership to a certain cremation society, he put into the form of positive entreaty a desire that his body should be burned to ashes before burial. Ardilange had, therefore, superintended the holding of this ceremonial.

Ardilange's marriage to Violet Fythian was to have been held at Gowerleigh on a certain day in early autumn. The bridegroom, the bridesmaids, and all the assembled guests, were waiting the appearance of Violet, when suddenly the most frightful shriek rang forth from one of her apartments. It was a small chamber, and she had gone there, in her wedding robes, for a moment, seemingly desirous of a brief solitary interval. Her women, horrified by the shriek, rushed in to her. They found her fallen on the floor, with a photograph of Guy Thyrle, her dead lover, clutched in one hand. When they raised her she was dead.

The story of this romantic death diffused itself abroad with a speed and sharpness that resembled poor Violet's blood-curdling cry. And what added to the grim poetry of the whole occurrence, clinching it with stronger tenacity of tradition to the picturesque stone walls of Gowerleigh, was the fact that during the next few weeks Vincent Ardilange, the man who had been on the verge of marrying Violet and had so prominently concerned himself with the cremation of Guy Thyrle's corpse, committed suicide. Naturally, stories now floated about that he had murdered Guy Thyrle and that the spirit of the slain had appeared to Violet just before her wedding-hour, informing her of this ghastly truth. In vain Ardilange's defenders made it clear that Guy Thyrle had been pronounced dead by two physicians of excellent repute before his cremation, and that the cause of his death had formally been declared cardiac paralysis. In vain, too, did Lord Henry Fythian flout and scoff the whole phantasmal tale. He died at Vichy within the year following his daughter's demise, though not either of grief or shock. He simply succumbed to gout, at an age when it is apt to carry off many high-livers like himself who have for years neglected its omens. After his death Gowerleigh fell to a sister who had married a German baron who had lived away from England for years, and who detested the idea of returning there. She readily enough assented to Cecil Savernay's offer of purchase, and so the estate of Storrowby absorbed just that tract of land which its owners for several past generations had craved. "It's a charming possession," Cecil had at first exulted. "It's like having a dower-house. I'm proud and delighted to own it, and I intend to be very tyrannical about leasing it to only the most agreeable of tenants."

He failed in this plan, and at length consented that people should occupy it of whom he knew little and cared less. After a few weeks of residence, these occupants deserted Gowerleigh. They had seen the ghost of Guy Thyrle there; or, if they had not seen it, they were said to believe as much, and to state so in shuddering avowal.

"Preposterous rubbish!" Cecil now declared. At this time he and Vivien had been married about six months. "Let's move over there for a while," he said to his wife. "Are you at all nervous about going?"

"Not in the least," laughed Vivien.

They spent three nights at Gowerleigh, and had not the faintest ghostly experience. This course in the master of Storrowby produced its effect. Shortly afterwards a new family of tenants moved into the shunned house. They stayed there precisely a month. Then the head, an irascible barrister, threatened suit against Cecil for having presumed to jeopardise the life of his young and invalid daughter.

"I don't understand you," said Cecil, with a kind of merry haughtiness. "How, pray, have I jeopardised the life of your daughter?"

"I will tell you, sir," began the angry barrister.... But poor Cecil soon found that no lucid disclosure was vouchsafed him. What had happened to the young lady? Had she seen or heard any phenomenal thing? The answers to these inquiries were no less voluble than vague.

"The girl," he afterwards said to Vivien, "has heard that wedding-day story and also certain prattle about our other tenants having quitted the house in a pell-mell scare. She no more saw any ghost than there's any ghost to see. 'Give a dog a bad name,' Viv, dear. It's too idiotic, but I suppose we've got to stand it. And they talk of the superstition of the Dark Ages being dead! Not a bit of it. Luckily, however, we can have cakes and ale without getting them from the Gowerleigh rental.... I've a good mind to refuse the place to the next fellow that wants it!"

But Cecil did not. A weak-lunged Frenchman, with a little tawny, moustached wife, who had persuaded him that "Eenglish" air would bring him marvels of betterment, made a bid for the house and secured it. They stayed six months, and finally departed, with audible shivers.

One or two of the latter reached Cecil's ears. He went over to Gowerleigh, and requested to see the Count de Lespinasse. Cecil spoke French execrably, as do many cultured Britons; but on meeting the Count (who spoke scarcely any English at all) he made himself rather memorably understood.

"You no longer wish to remain at Gowerleigh," he said, "and that, of course, monsieur, is quite your own affair. But you will pardon me for saying that to spread reports of its being haunted is an injury to myself as its owner."

The count, a spectrally pale person, whose white growth of beard always covered a pair of lantern jaws with the effect of his having needed shaving the day before yesterday, now put a skinny hand to his hollow chest and denied that he had ever spoken a derogatory word about Gowerleigh.

Cecil chanced to feel certain that this was a falsehood. Presently Madame de Lespinasse appeared, and airily confirmed the assertion of her spouse.

"Then," said Cecil, "I am to understand that you both will support me in declaring this house free from ghostly intrusions?"

Madame exchanged a glance with the count. "Since we learned that terrible story, monsieur—" began the latter, with solemnity....

His wife waved him an interruption with one restless hand. It made Cecil think of the shops on the Parisian boulevards, or say on the Rue de la Paix, where, if you wanted to buy anything, from a paper of pins to a dozen of shirts, you always began with "Monsieur," only to have "madame" step up and take possession of you.

And madame now took the most irritating possession of her landlord. She did not believe in ghosts—oh, jamais de la vie! But very strange things had happened here of late. Some people might call it nerves; she herself had no nerves to speak of, but her husband, being an invalid, was less fortunate. Seen anything? Oh, it was best not to go into details before Monsieur le Comte. They had made up their minds, in any case, to try Vichy. Monsieur de Lespinasse had a friend who had written him marvels about Vichy at just this particular season.... Had they heard strange noises? Well, yes, many, many. Had they known that dreadful story before taking the house? Possibly no; possibly yes. One hears such a quantity of things that one forgets. The gossip of servants? Ah, who could prevent that from finding its way to one's ears? Had any ghost actually been seen? Ah, would not Monsieur Savernay please be careful? The count did not wish to talk, and madame herself preferred to be silent. On that one subject, "N'en parlons plus, Monsieur Savernay, n'en parlons plus, je vous supplie!"

After this tantalisingly mystic appeal Cecil found himself requested, with the utmost courtesy, to stay to luncheon. Smiling blandly below the dusky down of her moustache, madame besought him to try a cup of chocolate or a glass of Château Larose.

He escaped, however, as civilly as his irritation would permit.

"The same old story!" he exclaimed to Vivien, when they again met one another. "Hang all future tenants for Gowerleigh! I'll keep it up—it sha'n't run to waste; but if I'm offered five thousand a year for it to-morrow I'll say, 'No, thank you; the ghost objects.'"

SITTING there in the cool, commodious room, Raymond let his musings languidly drift him along, like the current of a stream that moves amid mutable landscape. He recalled coming down from Oxford, one vacation, and having a rather heated talk with his brother.

"You're too sweeping altogether, Cecil."

"That's the way to deal with cobwebs."

"Cobwebs, like ghost-stories, are very complicated affairs. You shouldn't forget that, my dear brother."

"I don't, Ray. Their complication, as you call it, is just what makes 'em so hard to destroy."

Here Raymond, who had found time to read many tough and abstruse books, outside of collegiate demands upon his intellect, said, with hardy directness,—

"Look here now, Cecil, you treat an immense mass of human testimony with an immense amount of disrespect."

"Bah!" said Cecil.

"'Bah!'" frowned Raymond, "is not an answer; it's an evasion, and a pretty lame one."

"Lame, is it?" laughed Cecil. "I'll take one of its crutches, young Mr. Impudence, and break it over your head."

"Insult me in whatever way you wish, except by calling me young. You've no right to do that. I'm only three years and eight months younger than you are-"

"And six times as clever, I admit, Ray. But oh, not half so sensible! Mass of human testimony! Why, there isn't a ghost-story ever recounted that a logical, unemotional investigator wouldn't be able to put his hat through if he tried."

"The amazing disclosures of spirit-manifestation in America-"

"Have never been scientifically verified. Assertions of miraculous doings have been made; that is all. If you bring up mind-reading, hypnotism, and all that, I've nothing to say. There's no ghostly element in those. Either they're true or false. If true, then they're dependent on some natural law or laws, yet undiscovered. Recollect, please, that we're talking of only one thing—the existence of the spirits of human beings after death, and of their power to make that existence palpable to living beings here on earth."

"Agreed.... Then how about the revelations from India?"

"India!" gaily jeered Cecil. "The land of jugglers! Superstition has had its clutch on the throat of India for thousands of years. Nature, there, is a constant terrorism. For that matter, the very word 'oriental' is an indorsement of brummagem magic. The whole East is the very cradle of silly mysticism. Everything they haven't understood they've spiritualised. When it thundered, that meant one god; when the earth opened, it meant another. The instant anything scared them out of their wits, from a snake to a cyclone, they got down on their knees and worshipped it. No India talk for me, please! Even the poor old ghost over at Gowerleigh is more respectable."

"You slept three consecutive nights over there at Gowerleigh, you tell me," recommenced Raymond, after a perceptible pause.

"Of course I did," smiled Cecil. "And I'll confess to you, Ray, that each night I made an ass of myself. Dear little Vivien didn't know it; she was too sound asleep—Heaven bless her healthy young nerves!"

"Pray how did you make an ass of yourself?" asked Raymond, with gentle satire, "since you are so magnanimous as to confess the possibility of at least this one miracle having occurred?"

Cecil took a pen-wiper from the library table, near which he sat, and fired at his brother's head its black butterfly of flannel. It struck Raymond's lighted cigarette and put it out. At which Raymond rose and took very deliberate aim, with the same missile, failing, however, to quench the spark, of his brother's cigar.

"Now," muttered Cecil, "I will be magnanimous. I can afford to be."

"Let's hear," said Raymond, re-seating himself, "this particular, up-to-date asinity."

"Take care; I'll put out that fresh cigarette you're lighting."

"It won't matter. I've lots more."

"Of course you have. You ought to be placed on an allowance of them. I believe they're nicotinizing you into a bigoted spiritualist.... Well, my acts of folly were these: each of the three nights I spent a good hour roaming about that house with a candle. And in the dimness and the almost deathly stillness I kept repeating, 'Guy Thyrle, Guy Thyrle, are you here?' And several times I—well, I made overtures decidedly more social. Not anything of the wilder theatrical sort, don't you know? But it was a kind of Macbeth-like invocation business, nevertheless.... Are you laughing at me, off there in the shadow?"

"Not a bit, Cecil. I'm only thinking that you and your vaunted scepticism are not such fast friends, after all.... And Guy Thyrle was irresponsive, eh?"

"Implacably. And because there wasn't any such bugaboo to be otherwise."

"Then why did you seek to call him from his vasty deep?"

"Simply for a final proof—"

"That he was mythical? But you forget that you totally disbelieved in him before. Now, if perfect faith is the sworn foe of doubt, surely complete incredulity should be—"

"Hold your tongue, Ray. Haven't I admitted my own idiocy?"

AND so they had wrangled, that day, though fraternally enough. Later, they had held many more talks together, and the younger brother had begun to look upon the elder as a rationalist whose scorn of all so-termed supernaturalism could scarcely have been shaken if he saw the dead rise from their graves.

Thenceforward Gowerleigh had remained unleased, nor was any occupant sought for. And while he moved from room to room, this fragrant and melodious morning, a resolve shaped itself in Raymond's mind.

He, too, would make a test like that of Cecil. He, too, would sleep at Gowerleigh, not for three nights, but a week of them.

"I mean to give the ghost a glorious chance," he said to himself, grimly jocose. "There'll not be a shred of excuse for him, this time, if he doesn't, as Cecil would phrase it, 'turn up.'"

BUT no such event occurred. Raymond changed his apartment every night in the whole seven. Each night he slept ill. He had no fear, and at times he had in place of it an expectancy high-strung and acute. He would rise, long after midnight, and sit in total darkness. There was no moon that week, or he would have let its light stream through the windows. Repeatedly he stretched forth his hand and waited for some responding touch. Repeatedly, too, he pronounced the name "Guy Thyrle." Once, at surely two in the morning, he descended into the cellar, and stood there for a long interval, amid pitchy gloom.

But no manifestation ever came to him. At times he wondered why he did not imagine one. But always he would tell himself, instantly afterwards, that nothing save the most palpable proof would satisfy him. If, for example, a hand had caught his own, or a touch had fallen upon his person, darkness would have given him only added reason for wrestling with the Presence, whatever it was. Intensely emotional in his desire, he stayed, notwithstanding, intensely cool and brave. Cecil, he felt certain, could not have been more so.

"And yet Cecil," he admitted, "has not my sense of awe, my imagination, my nervous impressionability. Where these would land me if I once found myself face-to-face with what I believed was Spirit, Heaven knows!"

At the end of the week he was pierced with disappointment, while mocking his receptivity to its pangs.

"As if I expected anything would happen!" passed one minute through his thoughts, and "As if I did not expect it!" came, absurdly contradictory, the next. At last he bade good-bye to Gowerleigh; he would go there no more. Its very symmetries and serenities had grown irritating to him. Meanwhile, he had received two or three happy letters from Cecil and Vivien. They were enjoying London vastly; it had never been so gay, so full of novel and delightful, people. Had he not had enough of solitude? Why would he not join them soon?

He decided one hour to obey their genial summons, and the following hour decided that he would stay on at Storrowby. He knew that his health had continued to fail him, but in the way men know such facts when they are wilfully averse to the recognition of them. His first night in his old home was perturbed, packed with fatiguing dreams. At Gowerleigh, too, he had dreamed dismally, luridly, fantastically. But he had never confused dreaming with waking, and he had always laid, as it were, a physician's finger on his own pulse, to mark just how febrile or normal were its beats. He had it hauntingly on his conscience, however, that he needed a real physician to retune something in him which had grown oddly discordant. But at this point he told himself that if he resorted at all to medical aid it should be of the finest and most eminent. Hence he concluded to go up to London, after all, and thus to blend practical benefit there with whatever diversion his two cherished relatives might have in store for him.

"I hope my new mood will be permanent," he thought, unconscious of the mental malady to which this feeble self-distrust perhaps pointed. "If it prove so, I'll have my things packed to-morrow and take a sudden plunge into town turmoils."

But a little later he remembered that he had left at Gowerleigh (in the very chamber where he had first sat and meditated, not many days ago) a certain enamelled match-box which had been the gift of a dear Oxford friend, and which he valued specially for this reason. He therefore determined to visit the place once more, and did so that afternoon.

The sky was clouded, now, and all the distances looked vaporously grey. Every tree was one torpor of breezeless green. The humid heat oppressed and tired him. After he had found his little match-box on the sill of the same window near which he had paused, that recent morning, he sank quite exhaustedly into the same easy-chair he had occupied then.

His gaze wandered about the sunless and placid room. He was not thinking of Guy Thyrle's ghost. This was a subject now wholly dismissed, if not forgotten.

Suddenly, against the walnut panel of a large wardrobe he saw what seemed to him a transparent white figure. The panel was polished, and he at first explained this effect by some reflection of light on the mirror-like glimmerings of its surface. Perhaps even some out-of-door image had been pictured there, caught up through one of the open windows from the adjacent lawn.

Raymond slowly rose. The figure did not change in the least. It was very shadowy, like a sketch done lightly in chalk against a background of pale tints. The limbs and breast were quite nude, and vaguer than the face, which was that of a man somewhat older than thirty, with a short, black, curly beard. It had a look of wildness and great pain; the instant Raymond fully scanned it, he perceived this. The mouth curved downwards at either corner, the brows were knit, the nostrils tense and tremulous. But though a face ravaged by agony and despair, the look of it was still not human. It seemed to affirm, in some piteous yet mystic way, that its capacity both of suffering and joy was spiritual of scope, and hence almost incalculably keener and broader than any which mortals might know. The sublimity of torture conveyed by it awed Raymond.

He approached it, and as he did so it in turn approached him. It seemed to float out from the panel, as though a shape painted there had become possessed of motion. To its observer this act was far more appalling than if night and dead silence had accompanied it. Recently, here at Gowerleigh, night and dead silence would have been for Raymond a natural surrounding of some such anticipated spectre. Now, in prosaic daylight, unprepared for the least phenomenal occurrence, he faced the apparition with fluttering heart and whitening cheeks.

It drew nearer, lifted well above the floor, a vision colourless, nebulous. One might have fancied that some sort of calm air-current had gently propelled it and then left it poised there before him, as buoyant and quiescent as a leaf on a still pool.

"I am the ghost of Guy Thyrle," it seemed to say. But the voice did not cause its lips to move. This sound merely flowed forth from them, as from the stirless marble or bronze of a statue's.

ONE morning, two days later, when Raymond Savernay suddenly appeared at his brother's handsome little house in Curzon Street, Cecil was overwhelmed to see him.

"Ray, my boy, so you've really come to us! Vivien will be delighted. Too bad that she's just driven off—I suppose to Redfern's, in Regent Street, or to squandering of guineas in the Burlington Arcade. Excuse these topsy-turvy flannels. I was tired, from late hours (one does keep such awful hours here!), and so lay down for a little snooze before the garden-party at which we're promised, this afternoon, somewhere over in Surrey.... But, by Jove! my boy, now that I look at you closer, you seem tired, too."

"I am, Cecil—if that's the right name for it."

Cecil had been holding his brother cordially by both hands. He loosed his clasp now, and they both sank into seats, facing one another, so close together that their knees almost touched.

"You mean that you're truly quite ill, Ray?"

"Does it strike you that I look ill?" Then, with a smothered sigh, "Yes, I know it does. If you hadn't told me so already I could read it in your odd stare."

Cecil kept silent, at first. Those feverish eyes, that drawn mouth, that new, livid pallor—what way but one to define them?

"Ray," he soon said, "you're pulled down; there's not a doubt of it. You must see a doctor. That's why you came, old fellow? We'll go together and have a talk with the best that can be found in London."

Raymond shook his head. Then for a moment he closed his eyes, and when he re-opened them their hectic light appealed to Cecil as pathetic in its brilliance.

"No doctor can possibly do me any good," he answered.

"Ray! What are you saying?"

He laid one hand on Cecil's arm, keeping it there while he murmured,—

"I've seen him; I've seen Guy Thyrle; I've met him, face to face, as I meet you now—all that is left of him!"

Cecil looked horror-stricken; then his mouth mellowed into a smile.

"Ray," he cried, "don't be absurd. You've had a specially nasty nightmare; it's nothing but that!" He rose, and took Raymond by both shoulders, leaning over him and gently shaking him. "We'll go at once to Dr. Lascombe; I'm sure he'll be just your man. He has an immense practice, and deserves it. Nervous disorders are his specialty. I chance to know him personally. Three years ago, while you were at Oxford, I'd come up here and was seized with a series of the most frightful headaches. He cured me—oh, but you remember, of course, my boy; I'm sure I've told you about him before. And I've been to see him lately, and he's just as nice and interesting as ever. It's only a short drive from here—to Harley Street, you know.... Wait till I get myself into civilised clothes, Ray. I'll be with you in five minutes. There, now; sit precisely where you are, and ring that bell if you want anything."

Off darted Cecil. His brother sat quite still for a short while. Then he took out a little memorandum-book and stared down at its open pages. Cecil was absent scarcely more than ten minutes. When he reappeared he was not only attired in a morning coat, but was drawing on a pair of modish gloves.

Raymond quietly quitted his chair.

"Cecil," he said, with tones that had a throb of reproach in them, "I clearly understand your anxiety. But, pray, is not your present course of action a trifle precipitate?"

"My dear Ray! You think so now; but I'm sure you'll view the matter differently after we three—you, Lascombe, and I—have had an intimate chat together."

"An intimate chat together," repeated Raymond, sneering the words, though fatiguedly rather than bitterly. "And that will mean—what? A prescription, from your medical friend, of bromides and other sedatives, and his advice that I should dose myself with some sort of German or Austrian water, forswear tobacco, live on a rigidly Spartan diet-"

"No, Ray," began his hearer. "Perhaps, on the contrary-"

"Pardon me. Perhaps, on the contrary, he will counsel me to take a voyage round the world." Here Raymond smiled. "How if I myself proposed for myself to take a voyage out of the world?"

Cecil looked steadily at his brother. Then he bit his lip, and gave his head an impatient toss. "That's very queer talk, Ray, from a sane man."

"Not so queer as you think it."

"Out of the world? What can such a phrase mean except—?"

"Suicide?"

"Yes." ... Here Cecil drew close to his interlocutor. "I know you too well," he went on, with much mingled gravity and sweetness, "to believe you capable of coming here and telling me that you've any such silly, sensational intent!"

Raymond gave a short, sad laugh. "I haven't told you so. But when you've heard what I really did come here to tell you I'm convinced that you will justify suicide in me if I choose to commit it."

"Oh, Ray, Ray!"

Receding a little, the younger brother said,—"Don't pity me. There's another whom you should pity infinitely more."

"Another?"

"Guy Thyrle—or all, as I said, that is left of him." Cecil began agitatedly to pull off his gloves. He dearly loved his brother, and now felt confident that the curse of insanity had overtaken him. This visit to Dr. Lascombe must be abandoned—at least, for the present. Plainly there was some sort of demented confession that Raymond would be willing to make.

"This little room," he now said, "is a sort of private den of my own. Nobody need bother us for an age if you'll just settle yourself comfortably on that big lounge yonder, and speak out with perfect frankness all that you care to disclose. Will you not do so, dear boy?" And he put an arm fondlingly about Raymond's neck.

The tenderness of these words wrought an abrupt and unforeseen effect. Raymond suddenly embraced his brother, and became convulsed by a passionate flow of tears.

A little later Cecil led him to the lounge. He sank upon it, and while the paroxysm wore itself out in recurrent sobs, exquisitely strange and painful to hear, Cecil once more slipped from the room.

He stayed away only long enough to scribble a brief note to Vivien, pending her return. In this note he informed her that Raymond had arrived, that he was deplorably ailing and unstrung, that they would probably remain in privacy together for a good while, and that the best plan was not to look them up at all, but go to the garden-party alone. He gave a few orders, also, to one of the footmen. This concerned the serving of luncheon, for which he would ring when he desired it.

Returning, he found Raymond much calmer. He still reclined on the lounge. Cecil drew a chair to his side and took one of his hands. The hand was drily hot, but the face above it wrung Cecil's heart.

"When you feel stronger, Ray," he soon said, "you must tell me everything. Will you?"

"I—I don't know; I am not sure about it. I came here to speak right out, with no reserve. It seemed to me that I must; and then there was only you. But now, Cecil, you've discouraged me. I see in your face that you will only rate as madness anything I may say. And yet ... you yourself went to Gowerleigh and passed three nights there."

"Did you go as well?"

Raymond nodded, and a loitering sigh escaped him. "Yes, I went as well. I spent seven nights there. But nothing happened then. What befell me was in broad daylight." He spoke on, recounting where and how he had looked upon the phantom. He ceased suddenly in his recital, after stating how it had floated towards him and then paused motionless.

Cecil, though sceptic to the bone, felt his flesh crawl. Raymond, who had spoken with head supported by one hand and an elbow buried in a cushion of the lounge, here lifted himself to a sitting posture.

"I have ordered luncheon to be served here," Cecil said, rising, with tremors in his voice that he failed to steady. "You must have a glass or two of sherry, Ray, before-" And he stopped short.

"Before I tell you the rest?" asked Raymond, with a desolate smile flashing over his face. "The rest!" he repeated, in quivering whisper and as though quite to himself.

When luncheon was brought, Cecil forced his brother to swallow a slice or two of cold fowl. But he ate with plain disrelish, and then drank several glasses of wine in an automatic way. At once the wine seemed both to strengthen and excite him. He got up and began almost impetuously to pace the chamber. At length, with a smothered moan, he returned to his former place on the lounge.

"Of course there is more to tell me," proposed Cecil, with as much easy levity as his discomfiture would permit.

"Yes—there's more."

"Well?"

Cecil was now seated again. He leaned forward, and tried to hold with his own Raymond's disquieted and burning gaze.

"Yes, there's more. The Thing spoke to me. It spoke on and on for hours. I seem to recall every syllable it said. But even if I repeated the whole thrilling monologue, you, Cecil, would think mere madness the mood into which it has plunged me."

"What mood, Ray?"

Many minutes passed before a sentence of response came. And then, in tumult of volubility, these words were poured upon their listener:

"Conceive, Cecil, of a human soul that is doomed for all eternity to wander homeless, hopeless, aimless, denied the right to die! We say 'all eternity,' as if it had an all or a part; it has neither; it has merely immensity, and this encircles for ever one lost and agonised spirit!"

Cecil began to drum faintly with his finger-nails on the table near him. He could not look into his brother's haggard yet enkindled face and call this declaration absurd; still, here in his Mayfair house, with cab-wheels echoing outside and all huge, practical London surrounding him, it perforce wore an incongruity sharply grotesque.

"The ... the ghost of Guy Thyrle said this to you, Ray?"

"This, and far more."

"Upon my word,'I hope it wasn't all so ghastly."

"Ah, Cecil, Cecil," came the weary and yet reproachful answer, "don't treat lightly what to me teems with unspeakable pity and awe!"

"I agree with you that it's most horrifying and melancholy, if it's true."

"True?" cried Raymond, letting one uplifted arm stay arched for a moment above his head. "If it isn't true I'm a living lie myself. And ah, how its truth has burned into my soul!"

"Ray, you must not let yourself go like this! You must draw a tighter rein, dear boy!" While he thus spoke, Cecil Savernay had lost all further doubt concerning his brother's sanity.

"Oh, I can keep myself calm enough," Raymond muttered, "till the time comes."

"'Till the time comes,' Ray? Now, what can you possibly mean by that? Frankly let me learn."

With drawn lips, with tightened nostrils, with one hand fluttering in strange disquiet about the region of his throat, Raymond huskily answered,—

"Oh, I'll be very frank! You may think now that I'm crazed, but you will not think so when you've heard all he confided to me. The great point, Cecil, is this: I must die to save him. I must die to give Guy Thryle's ghost repose from its terrible wanderings. Here's no finely heroic conception; it's merely what any man with a human heart in his breast would feel himself bound to do. We talk of moral obligation. Mine is of stupendous pressure. He has made the course inflexibly clear to me. In brief summary, his case stands thus: Not many years ago he made a great discovery, this man, Guy Thyrle. He not only found out that he had a soul, but he mastered a means of causing it to desert his physical flesh at will. I don't imply any theosophical stuff about the 'astral bodies' of those Eastern dreamers. I affirm that Guy Thyrle did not merely solve through science the problem of the existence of a soul, but that he could make it leave his body whenever the inclination so directed him.... Never mind the details, Cecil; these, if you choose to hear them, will be imparted later."

"I see, dear Ray. And the bare facts are ...?"

"Some time previously he had joined a cremation society at Bristol. A certain bond of agreement existed (half forgotten by himself) which authorised the society to cremate him on his death."

"Yes ... well?"

"This document had been made use of by a friend of his—an enemy in reality—a man whom he had told of the amazing power which he had managed to secure. When, after flights and wanderings, Guy Thyrle's ghost one day resought its body, every shred of it had been resolved into—ashes!"

"Horrible indeed!" broke from Cecil. He rose and peered gropingly along the mantel, as if in search of a match for the unlighted cigar he held.

Meanwhile it was speeding through his brain,—"Poor, dear Ray! How desperately sad! Ah, what can I do for him? It's heart-breaking to see his mind going like this! ... What can I—what ought I to do?"

AS Cecil reapproached him, Raymond again began to speak.

"If Guy Thyrle could have regained his body, and gone through the process of actually dying—whether by violence or what we call a natural death—the terrific doom that now curses him might have been averted. As it is, he came to me a suppliant. It is only with supreme difficulty that he can materialise himself. Of the influences which enable him to do this he is always confusedly doubtful. They are dependent upon certain atmospheric conditions which he is powerless to explain. He is simply aware that these conditions demand on his own part a prodigious struggle—something like the swimming of a stream whose cross-current threatens every second to whirl us over some near abyss. Afterwards his exhaustion is intense, and the pain that follows it like that of one buried alive and gasping below a coffin-lid."

"Ray! What are you saying?"

This came to me from his spectral lips—those immovable lips, that seemed to hold behind their pale curves all the sorrow of all ages and races and climes.... Such despair had breathed through his recital that when he spoke of a possible freedom I almost felt myself shouting with joy—with the joy, Cecil, of realising that some sort of help could conceivably reach him in his unspeakable durance, exile, calamity!"

"Joy, Ray? How is that?"

"There's no other word for it. Say you are walking in the street and see some fellow-creature in great peril. A building is about to fall and crush him; there is a dog crazed by rabies in another street whose near corner he is about to turn. Your impulse is inevitably to save him. If the situation is worse, and involves threat to your own life, you still wish to take personal risks. This is but natural with men of ordinary courage and sympathy.... But intensify these conditions a million-fold. Say that you are brought into contact with a fellow-creature whose tortures must be eternal unless you yourself will to relieve them. Would not you so will at the cost of your own life? Except to some callous egotist, dying would seem triviality beside such endless living as his! And he has made me certain, Cecil, that my own death would be his deliverance."

Cecil controlled his face, and thought how strange were the freaks and tricks of madness. His brother's air was impressive, convincing; it almost made you forget the fatuity of what he said. But for his woeful pallor and the strange brilliance of his eyes, even Cecil might have felt credence duped, at least transiently. Now he said,—

"Dear Ray, your words are fantasy itself! I only hope that soon you and I will smile at them together." Then he paused, not liking the cloud that his own words had quickly put into Raymond's face. "Well," he added, with an effort at laughter, "this ghost of Guy Thyrle is certainly a very selfish fellow. I can't see that he has the least business to require so huge a sacrifice from you or from anybody."

"He does not require it," burst from Raymond. "He has merely disclosed to me the way in which I could release him, were I so to will."

"And this mode of release is—your own death?"

"My own death, if I choose, by dying, to rid him from his present endless curse."

"If you choose, that is, to commit suicide as an act of personal sacrifice."

"Yes."

"But how can your performance of this act aid him?"

"He has made that whole question as clear as it lies in his power to make it. By discovering the means which enabled him to quit his body whenever he so desired, Guy Thyrle (having dealt with purely scientific methods of search into natural laws) violated none of those mystic ordinances which enfold and intersect and underlie the whole enigma of the universe itself. But there was some hidden power that he did violate, though unwittingly, when he failed to find the body he had deserted at will. This body had become disintegrated—resolved into a state impossible for his rehabitation. Compare his spirit, if you please, to a key of some unique design whose lock has been shattered. One slight note in the enormous and complex harmony has become discordant. That note is Guy Thyrle. In the mighty melody it can never resume its former place, save by a single process of reinstatement. A fellow-creature must voluntarily die for him, and while so dying must will that Guy Thyrle's spirit shall instantly flash into the corpse from which his own flies"

With bowed head, Cecil was now nursing one knee. "Poetic, certainly, Ray," he murmured, sorrow and bewilderment both inwardly thrilling him. "But this reincarnation of which you tell me—how could your phantom visitor have found out its expediency except he were in close communion with that unseen Power which might grant him, through its omnipotence, a far less ghastly way of breaking his dismal ban?"

For a moment Raymond seemed to muse. Then, shaking his head in quick negative, "The spirit of Guy Thyrle knows nothing of any primal Power. He has motion and perception which to us would be miraculous. But of ultimate causes he knows nothing. Even the shades of men and women who have died natural deaths are invisible to him. Till he, too, has naturally died he can never envisage the Mystery discernible through death alone. With spiritual eyes he can look upon the material in ways that it now appalls me to think of. But, never having really died, he is powerless to bridge by any species of mental intelligence the chasm between matter and those awful energies which are its origin,"

"And yet he knows ...?"

"And yet he knows, by some unexplainable instinct, the secret of his restoration back within normal limits of entity."

Here a wistful fervour displaced the hard eagerness that had filled for many minutes Raymond's blanched face. He clasped his hands together, and then let them slowly fall into his lap, leaning forward in a posture of earnest entreaty.

"Oh, Cecil, let me tell you the whole story, just as he told it me that morning at Gowerleigh!"

"Willingly, Ray."

"It will be long—I warn you, it will be long."

"Never mind, Ray. But your strength—"

"My strength is wholly equal to the narration."

"And you remember ...?"

"Everything—everything! I seem to see a long written scroll within my brain, where each word is clear as though stamped there in script of scorch. What already I have said on this subject, Cecil, sounds forlornly inadequate. But from beginning to end I could recount Guy Thyrle's whole history, just as he himself related it."

"Pray do so, then, dear boy."

And waiting for no further solicitation, Raymond began. Hundreds of sentences flowed from his lips, but nearly all were delivered in a voice as tranquil as it was vibrant. Even during less composed intervals, however, Cecil noticed the recitative quality of his tones. He appeared to repeat rather than originate, to echo rather than affirm. Several times he went back in a phrase and gave it with a new turn, as though he had not at first rightly remembered it....

When he had ended, the summer twilight was flooding the chamber, and in its delicate bluish dimness the brothers' faces looked vague, each to each.

"There," said Raymond; "you have heard it all now."

"Yes."

Cecil did not know that he spoke. He had drawn out his watch, and was staring down at it. He closed it with a little snap of the gold case. Then, not being aware that he had taken it out, he took it out again, and this time made sure of the hour.

Raymond lay at full length on the lounge, now. He had let himself slip quietly into this posture after having ceased to speak. His face looked ashen and very tired. His eyes had closed, but they opened the moment he heard his brother's voice once more.

"Ray," said Cecil, standing over him, "I feel that you must be exhausted. Take this fresh glass of wine."

"Thanks."

He drank the wine, raising himself a little to do so. Then he dropped back, and smiled up into Cecil's face, wistfully, yet somehow with a sort of drowsy triumph.

"You feel like a short nap, don't you?" Cecil soon pursued. "Dinner is not till half after eight. You've lots of time for the most refreshing of dozes."

"Very well."

"If I leave you now, Ray, you'll stay here, will you not?"

"Stay here?"

"Yes, just here in this room. Dinner will be served you, as luncheon was."

"All right."

"But, Ray...." And Cecil let one hand tenderly stroke the locks above his brother's forehead. "You must make me a promise before I go."

"A promise?"

"Yes." And then Cecil bent down, whispering what more he chose to say.

"I promise," came at length Raymond's answer, slow and lingering.

"On your honour, Ray!"

"On my honour, Cecil.... You'll find me here when you return. And shall you be long gone?"

"I can't state how long. But my absence may last several hours. Meanwhile, trust in my return as a certainty. And remember, Ray, your sacred promise has been given me."

"I remember."

Cecil turned away. He stood quite still for a few seconds, with an irresolute, worried sombreness glooming every feature. Then he veered round again and went up to his brother and touched his brow with a kiss.

"You have sacredly promised, Ray, haven't you?"

"Yes."

"Well, then, I sacredly trust you."

FOR many minutes after Cecil had left him, Raymond lay quite still. Then he slowly drew his form from the lounge, and went to the mirror just above the mantel and watched there, for many minutes more, his own haggard reflection. As if addressing this, he said, in dogged undertone,—

"I've repeated to him the whole story. And he does not believe a word of it. He was intensely moved, and yet he does not believe a word of it. He thinks it all the coinage of lunacy. How well I read him! That friend of his—that Leverett Lascombe, of whom I've so often heard him speak, is first to hear and then to act—Cecil has gone to him. When he comes back he will bring Dr. Lascombe.... And what will be the result? Do I not know as clearly as if this instant I faced it? No matter how I protest and rebel—an asylum. Discipline, close watching, being dosed with drugs for weeks, months, perhaps years. Here I am, absolutely sane, and yet my sanity will profit me nothing. The very love that Cecil bears me will strengthen his zeal of gaolership."

Raymond left the mirror, and reseated himself on the lounge. In brooding way he drew forth a small pistol and held it loosely between both hollowed hands.

"Of course I could find means to fight against my continued imprisonment. A man of my wealth—but pah! why think of that? Having heard his heartbreaking appeal, knowing that I possessed the power to end his anguish—so unprecedented, so infernal—what would all my future life become but one prolonged conscience-pang?"

A new thought seemed to strike him. He started, slightly shuddering. Then he looked down with great steadiness at the pistol, and gave a brief, chill laugh.

"I promised dear old Cecil that I would not. Yes, I promised. But had I not seen in his eyes the bigoted 'no surrender' of the irreversible doubter? Should such a promise be binding? What is the sin of breaking it beside the sin of leaving Guy Thyrle's agonised spirit to endure that thraldom on and on through incalculable ages?"

He rose once more. A second time he drew near the mirror. As before, he stared at his own image. He held the weapon in one lax hand, its slim, lustrous tube pointing downwards. From the dimming London streets outside there came a drowsy roar, which the stillness of the little close-shut room seemed to deepen.

His face, the outlines of his brows and temples, were almost momentarily growing less distinct. Notwithstanding this, he could yet behold himself quite clearly.

"Guy Thyrle," he said aloud, with low resonance, "is not your whole dreadful story one insistent entreaty?"

He stood perfectly motionless and silent for some time, after this, except that his grasp on the handle of the pistol was no longer lax. It had sensibly tightened.

"LEVERETT, I'm so glad I found you at home."

"Have you forgotten my hours, Cecil?"

"No—yes. I've forgotten everything, my friend, except that I need you."

"Need me?"

"Oh, unspeakably."

"You're excited."

"My cab-horse tumbled flat in Piccadilly, and I had to get out. I suppose that has something to do with my distraught bearing. Why is it that whenever one is wildly hurried in London one always chooses a bad cab-horse?"

"Wildly hurried, Cecil? Mrs. Savernay-"

"Oh, Vivien is still at Lady Archie Challoner's garden-party, I suppose. No, Leverett, it's not she."

Then, quite rattlingly, but with good coherence, Cecil spoke on. Meanwhile the strictest attention was manifest in Leverett Lascombe's air. He might have been eight-and-thirty, and he had a clean-shorn face of cameo-like delicacy. He was thought very handsome, both by men and women, and was renowned for his fascinating deportment with the latter. As a physician of nervous diseases he had reached within a few years astonishing heights. He had been called a bloodless infidel, and his face, with its chiselled lips and nostrils, had surely a cold look; but the large eyes could beam very warm and soft from under the broad brow. As a rule unbelievers are not popular, even with our end-of-the-century communities. They who do not write "God" and "miracle" and "soul" and "immortality" with a capital as the first letter of each, very rarely learn, in at least one sense, how to spell the word "success." But Leverett Lascombe had learned. Probably he had done so in a way both audacious and facile; by blending cool indifference to public sympathy with exceptional medical skill.

"All this," he at length said, when Cecil came to a pause, "is surely most extraordinary."

"You mean, Leverett ...?"

"His dreaming like that, and not being afterwards conscious that it was a dream."

"You think, then, that beyond doubt he did dream?"

"Oh, I should say that the cerebral trouble first developed in that way. He fell asleep there at Gowerleigh, and in a few seconds may have dreamed all this grisly chronicle which you say it took him hours to unfold."

"This seems incredible."

"A good many things do seem so when one studies the structure and phenomena of the human brain. Permanent conditions of hallucination are now established in your brother."

"And these make his case a serious one?"

"Naturally, my dear Cecil, I can say nothing until I see him. All hallucinations, however, are serious."

"And what I've told you about his conviction that he ought to kill himself in order to release the spirit of Guy Thyrle from its dolorous bondage?"

"It's picturesque, isn't it?" said Leverett Lascombe musingly. He glanced about him, at the walls of this private apartment in which he had received Cecil. Severe simplicity reigned everywhere. The carpets and furniture were costly, but so plain and modest that to perceive their value was to scan them closely. On the walls, however, hung certain etchings of exquisite rarity.

"Picturesque, Leverett? To me it's terrifying."

"True ... true. Insanity, though, has its poetic splendours. Sometimes one can't help being struck by their sublimity, which verges on the Miltonic."

"But the intense consistency of Ray's assertions...!" Dr. Lascombe started, pursing for a second, in grave deprecation, his sensitive, fine-cut lips.

"Consistency, Cecil? You surely don't wish me to accede that you—always hitherto a thinker after my own heart—have been led to believe your brother really saw that ghost!"

Cecil drooped his eyes. "Oh, Leverett," he murmured, "if you had heard his story as I heard it!"

There came a pause, and then whatever largeness of character, of dominating individualism, belonged to this man, Leverett Lascombe, affirmed itself with decisive speed.

"I have heard many fairy-tales from mad people. They often remind me of the superstitions, both social and religious, which thousands of sane people are to-day venting and exploiting. My friend, madness, after all, as I study it, is a much greater factor of the human intellect than I dreamed it was twenty years ago. Everywhere, I see, men take on trust what exact knowledge would recoil from as the riff-raff of random fancy. This very credulity is a kind of dementia. Now, the human brain, when in perfect order, Cecil, is a rather prosaic affair. A complete equilibrium of all our mental faculties is hardly more interesting than a flatland, dotted over with shrubs.... I can imagine that this 'story' of your brother's is instinct with poetry, feeling, beauty, and even a felicitous kind of horror. But for an instant to credit it! ... Think: a spirit that has left its body through some Cagliostroish mode of exit, finds, one day, that body turned into ashes on application for re-entrance there!"

"You put the thing humorously, Leverett. I might have known you would."

"Oh, but, my dear Cecil! This spirit, then, wails that he can neither positively die nor yet enjoy his full rights of citizenship as a ghost in ghostland! Why, the thrill in the thing is supposable enough; we thrill over the battles of gods in the 'Iliad' and 'Paradise Lost.' But to accept them as verity! I'd as soon—and so ought you—admit that my pen-wiper, here, could flap its black flannel wings, and turn into a bat if so desirous!"

"I know all this, Leverett—I know, I know!" burst from Cecil, impetuously. "Still, I cannot help feeling that if you'd heard what I have lately heard from Raymond, your faith in his having merely dreamed it would be shaken as you're now unable to conceive!"

Lascombe slowly rose. "I'll hear the story," he said. "Will it take so very long? I think you told me it was voluminous."

"You've not the time, now," answered Cecil, as if in courteous afterthought. "I realise too well your many pressing engagements."

"I will make time, in this case," said Lascombe, with decision.... He quitted the room, presently, and Cecil heard his voice outside, or thought he heard it, as though giving certain orders to attendants, assistants, or both. Cecil felt grateful enough when his friend returned, and he said so. "It's no slight affair, I well understand, Leverett, to ask a long audience from one of the most famous physicians in London."

"Oh," smiled Lascombe, "it isn't precisely stopping the planet's revolution.... Now, frankly, Cecil, tell me: while we sit here, you speaking and I listening, shall you have no dread of leaving your brother alone in Curzon Street?"

"Dread?" he repeated, turning pale. "Ah, Leverett, do you think there is danger ...?"

"How can I tell? That is for you to judge. The hallucination exists, I should say, beyond all doubt."

"But his oath—his sacred promise to me?"

"Oath? Promise? He made one? You did not mention this before."

"Did I not?" sighed Cecil, with a hurried pass of one hand across his forehead. When he had spoken further, Lascombe slowly nodded, yet as if in assent that was dashed with doubt.

"My dear Cecil, he may keep that promise, and he may not. Madness is madness. I dare not encourage you."

Cecil seemed to reflect. "Madness!" he suddenly exclaimed. "Oh, Leverett, I can't believe him mad! I can't, and I'm certain that you, if you saw him, if you heard him—"

"My dear Cecil," came the gentle interruption, "if you think this way it is best I made you no answer at all."

"I see—I see," faltered Cecil. He straightened himself in his chair, crossed his legs, and folded his arms. "The risk," he now said, with resolute accents, "I'm prepared personally to take. Mad or not mad, I feel confident Ray will never lift a hand against his own life till he sees me once more. Afterwards I admit that I should not trust him. But afterwards, acting on your counsel, Leverett, I will employ every means of watch and ward that your tried experience may suggest."

"So be it, Cecil. And now for the ghostly disclosure."

A long pause followed. Cecil closed. his eyes and placed a flattened hand against either temple, as though sternly bewildered and oppressed. But soon his entire demeanour changed; new energy and calmness informed him. A little later he commenced the narration of what had been imparted so recently by his brother.

The story was given in a far more broken and hesitant way than when he had heard it from Raymond's lips. At times, too, he even stumbled or halted outright in the telling of it. What he said will therefore not be recorded in his own language. It has indeed been thought best to borrow neither his nor the more convincing voice of his brother, but to unfold in coming pages an impersonal chronicle, as though rearranged by one closely aware of all the leading facts, mindful that each of these shall secure due saliency of presentation, and conscientious in retaining whatever drama, poetry, or spiritual suggestion the original record may have disclosed.

ALL Guy Thyrle's early life was dull and tame.

His mother died in his third year, and he was brought up by a sour, faded old aunt, too fond of nursing her own aches and pains to care much for a boy's pleasures or griefs. Guy's father was the gentlest and most amiable of beings, but for eight or nine years he took slight notice of his only child. Thyrle Grange was once a valuable property, but through its master's indolence (and that, perhaps, of his ancestors as well) it had become heavily mortgaged and been mismanaged in other ways. For hours at a time Godfrey Thyrle would sit in his immense library devouring books. He was that queer combination, an unscholarly bookman. He used to say that he read because he was too lazy to do anything else. But he rarely read from any volume that did not enshrine good literature.

Now and then he would see his little son in an alcove of one of the library windows, or on a lounge, buried in a pile of cushions. Guy would always have a book, but his father took it for granted that pictures and not print allured him. He would stroke the boy's hair or pat his head, but that was all. He seldom spoke to him. He had got into the habit of regarding Guy as quite without the normal share of brains.

This was but natural, though it clearly betrayed his lazy and absent way of drowsing through life. When Guy was three years old he received a severe wound on the head by being flung from a carriage. The horses had taken fright and the nurse at his side had been killed. Had she not clasped little Guy in her arms at the fatal moment, he, too, would have met death. As it was, a fracture of the skull placed his life in peril, and when recovery came, several physicians declared that it would leave him permanently demented. And so, for a long time, it seemed to leave him. Godfrey Thyrle accepted the affliction with a philosophic sigh. There is no doubt that for a good while afterwards his son gave every sign of confirmed idiocy. But as Guy grew older his faculties brightened and strengthened. Meanwhile his father had accepted him, so to speak, as a little mental invalid impossible of cure. More than once his aunt, Miss Martha Thyrle, would tell her brother of the child's "improvement." But he never seemed to realise the full force of this information, and one day the elderly lady, with her sallow face wrinkled into quite a scolding scowl, said tartly,—

"I do think, Godfrey, you ought to treat your son better. That Miss Clagg I engaged for his governess is delighted with him. He's getting on remarkably well in his lessons. All that brain-trouble has passed. He is now a bright, nice boy, though very shy and bashful. He looks on you as a kind of genial bugaboo. It's dreadful that you shouldn't notice him in the least. Of course I can't give him the care I would give if I were less of a sufferer. You told me, not long ago, that you often found him in the library, busied with the pictures in certain books there. This is entirely a mistake. The boy reads those books, and it certainly is your duty to guide him in his perusals of them, for Heaven knows what distressing sort of entertainment he may drift into, browsing on some of those Eighteenth Century authors your shelves are full of."

That speech of his sister's had a world of meaning for the queer, apathetic spirit of Godfrey Thyrle. He at once woke to the fact that his child was intelligent, and soon found out that this intelligence teemed with interest and charm. The father's memory of books now seemed to him like an unopened mine whose veins of precious ore spread so richly just below terrene surfaces that to work them cost slight effort. He soon became Guy's firm friend, and delighted to aid Miss Clagg, the governess, in all questions of the boy's educational cult. There is no doubt that Guy's precocity helped greatly to stimulate and gladden the otherwise rather aimless and dreary years of his father's life. These years were not many, for Godfrey Thyrle died when his son had scarcely reached seventeen. By the time that tutors had fitted him for entrance into Cambridge, his Aunt Martha had also passed away.

At Cambridge Guy soon distinguished himself, though in a way quite unforeseen. His taste for what is called the "humanities" lessened suddenly.

Classical and literary studies ceased to attract him, and he became entranced by the exact sciences. Especially for chemistry he showed striking aptitude, and at the end of his college career he had won, in this department, shining honours.

Meanwhile he had not been popular with his Trinity co-disciples. Having previously lived a lonely life there at the Grange, he was ill-prepared to mingle on easy social terms with the students of the stately old historic town. His name and place in the world were good, but he soon acquired the repute of investing them with spurious importance. By some he was called arrogant, by others unsympathetic, by a few wantonly uncivil, and by a few more callously selfish. No doubt these verdicts were in all cases explainable by a native reserve and that lack of outward winsomeness which can agreeably decorate so many hypocrisies.

"I believe that in all these four years," he said, a day or two before leaving Cambridge, "I have made but a single friend."