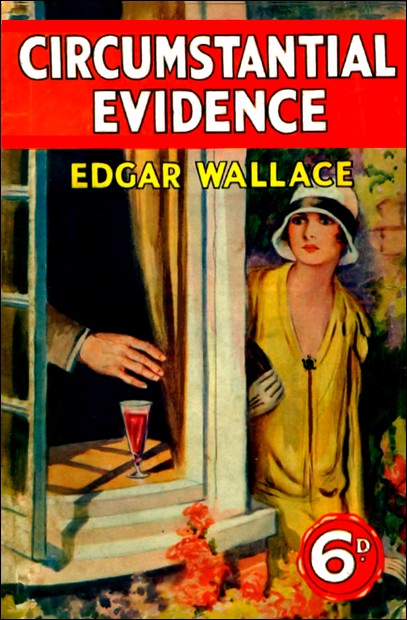

Note: Two collections of short fiction by Edgar Wallace with differing contents have been published under the title Circumstial Evidence and Other Stories. The later collection, published by the World Syndicate Publishing Company, Cleveland, Ohio, in 1934, is also available at Project Gutenberg Australia and Roy Glashan's Library.

Circumstantial Evidence — George Newnes Edition, 1929

Colonel Chartres Dane lingered irresolutely in the broad and pleasant lobby. Other patients had lingered awhile in that agreeable vestibule. In wintry days it was a cozy place; its polished panelled walls reflecting the gleam of logs that burnt in the open fireplace. There was a shining oak settle that invited gossip, and old prints, and blue china bowls frothing over with the flowers of a belated autumn or advanced spring-tide, to charm the eye.

In summer it was cool and dark and restful. The mellow tick of the ancient clock, the fragrance of roses, the soft breeze that came through an open casement stirring the lilac curtains uneasily, these corollaries of peace and order had soothed many an unquiet mind.

Colonel Chartres Dane fingered a button of his light dust-coat and his thin patrician face was set in thought. He was a spare man of fifty-five; a man of tired eyes and nervous gesture.

Dr. Merriget peered at him through his powerful spectacles and wondered.

It was an awkward moment, for the doctor had murmured his sincere, if conventional, regrets and encouragements, and there was nothing left but to close the door on his patient.

"You have had a bad wound there, Mr. Jackson," he said, by way of changing a very gloomy subject and filling in the interval of silence. This intervention might call to mind in a soldier some deed of his, some far field of battle where men met death with courage and fortitude. Such memories might be helpful to a man under sentence.

Colonel Dane fingered the long scar on his cheek.

"Yes," he said absently, "a child did that—my niece. Quite my own fault."

"A child?" Dr. Merriget appeared to be shocked. He was in reality very curious.

"Yes... she was eleven... my own fault. I spoke disrespectfully of her father. It was unpardonable, for he was only recently dead. He was my brother-in-law. We were at breakfast and she threw the knife... yes...."

He ruminated on the incident and a smile quivered at the corner of his thin lips.

"She hated me. She hates me still... yes...."

He waited.

The doctor was embarrassed and came back to the object of the visit.

"I should be ever so much more comfortable in my mind if you saw a specialist, Mr.—er—Jackson. You see how difficult it is for me to give an opinion? I may be wrong. I know nothing of your history, your medical history I mean. There are so many men in town who could give you a better and more valuable opinion than I. A country practitioner like myself is rather in a backwater. One has the usual cases that come to one in a small country town, maternity cases, commonplace ailments... it is difficult to keep abreast of the extraordinary developments in medical science...."

"Do you know anything about Machonicies College?" asked the colonel unexpectedly.

"Yes, of course." The doctor was surprised. "It is one of the best of the technical schools. Many of our best doctors and chemists take a preparatory course there. Why?"

"I merely asked. As to your specialists... I hardly think I shall bother them."

Dr. Merriget watched the tall figure striding down the red-tiled path between the banked flowers, and was still standing on the doorstep when the whine of his visitor's machine had gone beyond the limits of his hearing.

"H'm," said Dr. Merriget as he returned to his study. He sat awhile thinking.

"Mr. Jackson?" he said aloud. "I wonder why the colonel calls himself 'Mr. Jackson'?"

He had seen the colonel two years before at a garden party, and had an excellent memory for faces.

He gave the matter no further thought, having certain packing to superintend—he was on the eve of his departure for Constantinople, a holiday trip he had promised himself for years.

On the following afternoon at Machonicies Technical School, a lecture was in progress.

"... by this combustion you have secured true K.c.y.... which we will now test and compare with the laboratory quantities... a deliquescent and colorless crystal extremely soluble...."

The master, whose monotonous voice droned like the hum of a distant, big, stationary blue-bottle, was a middle-aged man, to whom life was no more than a chemical reaction, and love not properly a matter for his observation or knowledge. He had an idea that it was dealt with effectively in another department of the college... metaphysics... or was it philosophy? Or maybe it came into the realms of the biological master?

Ella Grant glared resentfully at the crystals which glittered on the blue paper before her, and snapped out the bunsen burner with a vicious twist of finger and thumb. Denman always overshot the hour. It was a quarter past five! The pallid clock above the dais, where Professor Denman stood, seemed to mock her impatience.

She sighed wearily and fiddled with the apparatus on the bench at which she sat. Some twenty other white-coated girls were also fiddling with test tubes and bottles and graduated measures, and twenty pairs of eyes glowered at the bald and stooping man who, unconscious of the passing of time, was turning affectionately to the properties of potassium.

"Here we have a metal whose strange affinity for oxygen... eh, Miss Benson?... five? Bless my soul, so it is! Class is dismissed. And ladies, ladies, ladies! Please, please let me make myself heard. The laboratory keeper will take from you all chemicals you have drawn for this experiment...."

They were crowding toward the door to the change room. Smith, the laboratory man, stood in the entrance grabbing wildly at little green and blue bottles that were thrust at him, and vainly endeavoring by a private system of mnemonics to commit his receipts to memory.

"Miss Fairlie, phial fairly; Miss Jones, bottle bones; Miss Walter, bottle salter."

If at the end of his collection he failed to recall a rhyme to any name, the owner had passed without cashing in.

"Miss Grant—?"

The laboratory of the Analytical Class was empty. Nineteen bottles stood on a shelf and he reviewed them.

"Miss Grant—?"

No, he had said nothing about "aunt" or "can't" or "pant."

He went into the change room, opened a locker and felt in the pockets of the white overall. They were empty. Returning to the laboratory, he wrote in his report book:

"Miss Grant did not return experiment bottle."

He spelt experiment with two r's and two m's.

Ella found the bottle in the pocket of her overall as she was hanging it up in the long cupboard of the change room. She hesitated a moment, frowning resentfully at the little blue phial in her hand, and rapidly calculating the time it would take to return to the laboratory to find the keeper and restore the property. In the end, she pushed it into her bag and hurried from the building. It was not an unusual occurrence that a student overlooked the return of some apparatus, and it could be restored in the morning.

Had Jack succeeded? That was the thought which occupied her. The miracle about which every junior dreams had happened. Engaged in the prosecution of the notorious Flackman, his leader had been taken ill, and the conduct of the case for the State had fallen to him. He was opposed by two brilliant advocates, and the judge was a notorious humanitarian.

She did not stop to buy a newspaper; she was in a fret at the thought that Jack Freeder might not have waited for her, and she heaved a sigh of relief when she turned into the old-world garden of the courthouse and saw him pacing up and down the flagged walk, his hands in his pockets.

"I am so sorry...."

She had come up behind him, and he turned on his heel to meet her. His face spoke success. The elation in it told her everything she wanted to know, and she slipped her arm through his with a queer mingled sense of pride and uneasiness.

"... the judge sent for me to his room afterwards and told me that the attorney could not have conducted the case better than I."

"He is guilty?" she asked, hesitating.

"Who, Flackman... I suppose so," he said carelessly. "His pistol was found in Sinnit's apartment, and it was known that he quarrelled with Sinnit about money, and there was a girl in it, I think, although we have never been able to get sufficient proof of that to put her into the box. You seldom have direct evidence in cases of this character, Ella, and in many ways circumstantial evidence is infinitely more damning. If a witness went into the box and said, 'I saw Flackman shoot Sinnit and saw Sinnit die,' the whole case would stand or fall by the credibility of that evidence; prove that witness an habitual liar and there is no chance of a conviction. On the other hand, when there are six or seven witnesses, all of whom subscribe to some one act or appearance or location of a prisoner, and all agreeing... why, you have him."

She nodded.

Her acquaintance with Jack Freeder had begun on her summer vacation, and had begun romantically but unconventionally, when a sailing boat overturned, with its occupant pinned beneath the bulging canvas. It was Ella, a magnificent swimmer, who, bathing, had seen the accident and had dived into the sea to the assistance of the drowning man.

"This means a lot to me, Ella," he said earnestly as they turned into the busy street. "It means the foundation of a new life."

His eyes met hers, and lingered for a second, and she was thrilled.

"Did you see Stephanie last night?" he asked suddenly.

She felt guilty.

"No," she admitted, "but I don't think you ought to worry about that, Jack. Stephanie is expecting the money almost by any mail."

"She has been expecting the money almost by any mail for a month past," he said dryly, "and in the meantime this infernal note is becoming due. What I can't understand—"

She interrupted him with a laugh.

"You can't understand why they accepted my signature as a guarantee for Stephanie's," she laughed, "and you are extremely uncomplimentary!"

Stephanie Boston, her some-time room mate, and now her apartmental neighbor, was a source of considerable worry to Jack Freeder, although he had only met her once. A handsome, volatile girl, with a penchant for good clothes and a mode of living out of all harmony with the meager income she drew from fashion-plate artistry, she had found herself in difficulties. It was a condition which the wise had long predicted, and Ella, not so wise, had dreaded. And then one day the young artist had come to her with an oblong slip of paper, and an incoherent story of somebody being willing to lend her money if Ella would sign her name; and Ella Grant, to whom finance was an esoteric mystery, had cheerfully complied.

"If you were a great heiress, or you were expecting a lot of money coming to you through the death of a relative," persisted Jack, with a frown, "I could understand Isaacs being satisfied with your acceptance, but you aren't!"

Ella laughed softly and shook her head.

"The only relative I have in the world is poor dear Uncle Chartres, who loathes me! I used to loathe him too, but I've got over that. After daddy died I lived with him for a few months, but we quarrelled over—over—well, I won't tell you what it was about, because I am sure he was sorry. I had a fiendish temper as a child, and I threw a knife at him."

"Good Lord!" gasped Jack, staring at her.

She nodded solemnly.

"I did—so you see there is very little likelihood of Uncle Chartres, who is immensely rich, leaving me anything more substantial than the horrid weapon with which I attempted to slay him!"

Jack was silent. Isaacs was a professional moneylender... he was not a philanthropist.

When Ella got home that night she determined to perform an unpleasant duty. She had not forgotten Jack Freeder's urgent insistence upon her seeing Stephanie Boston—she had simply avoided the unpalatable.

Stephanie's flat was on the first floor; her own was immediately above. She considered for a long time before she pressed the bell.

Grace, Stephanie's elderly maid, opened the door, and her eyes were red with recent weeping.

"What is the matter?" asked Ella in alarm.

"Come in, miss," said the servant miserably. "Miss Boston left a letter for you."

"Left?" repeated Ella wonderingly. "Has she gone away?"

"She was gone when I came this morning. The bailiffs have been here...."

Ella's heart sank.

The letter was short but eminently lucid:

"I am going away, Ella. I do hope that you will forgive me. That wretched bill has become due and I simply cannot face you again. I will work desperately hard to repay you, Ella."

The girl stared at the letter, not realizing what it all meant. Stephanie had gone away!

"She took all her clothes, miss. She left this morning, and told the porter she was going into the country; and she owes me three weeks' wages!"

Ella went upstairs to her own flat, dazed and shaken. She herself had no maid; a woman came every morning to clean the flat, and Ella had her meals at a neighboring restaurant.

As she made the last turn of the stairs she was conscious that there was a man waiting on the landing above, with his back to her door. Though she did not know him, he evidently recognized her, for he raised his hat. She had a dim idea that she had seen him somewhere before, but for the moment could not recollect the circumstances.

"Good evening, Miss Grant," he said amiably. "I think we have met before. Miss Boston introduced me—name of Higgins."

She shook her head.

"I am afraid I don't remember you," she said, and wondered whether his business was in connection with Stephanie's default.

"I brought the paper up that you signed about three months ago."

Then she recalled him and went cold.

"Mr. Isaacs didn't want to make any kind of trouble," he said. "The bill became due a week ago and we have been trying to get Miss Boston to pay. As it is, it looks very much as though you will have to find the money."

"When?" she asked in dismay.

"Mr. Isaacs will give you until to tomorrow night," said the man. "I have been waiting here since five o'clock to see you. I suppose it is convenient, miss?"

Nobody knew better than Mr. Isaacs' clerk that it would be most inconvenient, not to say impossible, for Ella Grant to produce four hundred pounds.

"I will write to Mr. Isaacs," she said, finding her voice at last.

She sat down in the solitude and dusk of her flat to think things out. She was overwhelmed, numbed by the tragedy. To owe money that she could not pay was to Ella Grant an unspeakable horror.

There was a letter in the letter-box. She had taken it out mechanically when she came in, and as mechanically slipped her fingers through the flap and extracted a folded paper. But she put it down without so much as a glance at its contents.

What would Jack say? What a fool she had been, what a perfectly reckless fool! She had met difficulties before, and had overcome them. When she had left her uncle's house as a child of fourteen and had subsisted on the slender income which her father had left her, rejecting every attempt on the part of Chartres Dane to make her leave the home of an invalid maiden aunt where she had taken refuge, she had faced what she believed was the supreme crisis of life.

But this was different.

Chartres Dane! She rejected the thought instantly, only to find it recurring. Perhaps he would help. She had long since overcome any ill- feeling she had towards him, for whatever dislike she had, had been replaced by a sense of shame and repentance. She had often been on the point of writing him to beg his forgiveness, but had stopped short at the thought that he might imagine she had some ulterior motive in seeking to return to his good graces. He was her relative. He had some responsibility ... again the thought inserted itself, and suddenly she made up her mind.

Chartres Dane's house lay twelve miles out of town, a great rambling place set on the slopes of a wooded hill, a place admirably suited to his peculiar love of solitude.

She had some difficulty in finding a taxi-driver who was willing to make the journey, and it had grown dark, though a pale light still lingered in the western skies, when she descended from the cab at the gateway of Hevel House. There was a lodge at the entrance of the gate, but this had long since been untenanted. She found her way up the long drive to the columned portico in front of the house. The place was in darkness, and she experienced a pang of apprehension. Suppose he was not there? (Even if he were, he would not help her, she told herself.) But the possibility of his being absent, however, gave her courage.

Her hand was on the bell when there came to her a flash of memory. At such an hour he would be sitting in the window-recess overlooking the lawn at the side of the house. She had often seen him there on warm summer nights, his glass of port on the broad window-ledge, a cigar clenched between his white teeth, brooding out into the darkness.

She came down the steps, and walking on the close-cropped grass bordering the flower-beds, came slowly, almost stealthily, to the library window. The big casement was wide open; a faint light showed within, and she stopped dead, her heart beating a furious rat-a-plan at the sight of a filled glass on the window-ledge. His habits had not changed, she thought; he himself would be sitting just out of sight from where she stood, in that window-recess which was nearest to her. Summoning all her courage, she advanced still farther. He was not in his customary place, and she crept nearer to the window.

Colonel Chartres Dane was sitting at a large writing-table in the center of the room; his back was toward her, and he was writing by the light of two tall candles that stood upon the table.

At the sight of his back all her courage failed, and, as he rose from the table, she shrank back into the shadow. She saw his white hand take up the glass of wine, and after a moment, peeping again, she saw him, still with his back to her, put it on the table by him as he sat down again.

She could not do it, she dare not do it, she told herself, and turned away sorrowfully. She would write to him.

She had stepped from the grass to the path when a man came from an opening in the bushes and gripped her arm.

"Hello!" he said, "who are you, and what are you doing here?"

"Let me go," she cried, frightened. "I—I—"

"What are you doing by the colonel's window?"

"I am his niece," she said, trying to recover some of her dignity.

"I thought you might be his aunt," said the gamekeeper ironically. "Now, my girl, I am going to take you in to the colonel—"

With a violent thrust she pushed him from her; the man stumbled and fell. She heard a thud and a groan, and stood rooted to the spot with horror.

"Have I hurt you?" she whispered. There was no reply.

She felt, rather than saw, that he had struck his head against a tree in falling, and turning, she flew down the drive, terrified, nearly fainting in her fright. The cabman saw her as she flung open the gate and rushed out.

"Anything wrong?" he asked.

"I—I think I have killed a man," she said incoherently, and then from the other end of the drive she heard a thick voice cry:

"Stop that girl!"

It was the voice of the gamekeeper, and for a moment the blood came back to her heart.

"Take me away, quickly, quickly," she cried.

The cabman hesitated.

"What have you been doing?" he asked.

"Take—take me away," she pleaded.

Again he hesitated.

"Jump in," he said gruffly.

Three weeks later John Penderbury, one of the greatest advocates at the Bar, walked into Jack Freeder's chambers.

The young man sat at his table, his head on his arm, and Penderbury put his hand lightly upon the shoulders of the stricken man.

"You've got to take a hold of yourself, Freeder," he said kindly. "You will neither help yourself nor her by going under."

Jack lifted a white, haggard face to the lawyer.

"It is horrible, horrible," he said huskily. "She's as innocent as a baby. What evidence have they?"

"My dear good fellow," said Penderbury, "the only evidence worth while in a case like this is circumstantial evidence. If there were direct evidence we might test the credibility of the witness. But in circumstantial evidence every piece of testimony dovetails into the other; each witness creates one strand of the net."

"It is horrible, it is impossible, it is madness to think that Ella could—"

Penderbury shook his head. Pulling up a chair at the other side of the table, he sat down, his arms folded, his grave eyes fixed on the younger man.

"Look at it from a lawyer's point of view, Freeder," he said gently. "Ella Grant is badly in need of money. She has backed a bill for a girl-friend and the money is suddenly demanded. A few minutes after learning this from Isaacs' clerk, she finds a letter in her flat, which she has obviously read—the envelope was opened and its contents extracted—a letter which is from Colonel Dane's lawyers, telling her that the colonel has made her his sole heiress. She knows, therefore, that the moment the colonel dies she will be a rich woman. She has in her handbag a bottle containing cyanide of potassium, and that night, under the cover of darkness, drives to the colonel's house and is seen outside the library window by Colonel Dane's gamekeeper. She admitted, when she was questioned by the detective, that she knew the colonel was in the habit of sitting by the window and that he usually put his glass of port on the window-ledge. What was easier than to drop a fatal dose of cyanide into the wine? Remember, she admitted that she had hated him and that once she threw a knife at him, wounding him, so that the scar remained to the day of his death. She admitted herself that it was his practice to put the wine where she could have reached it."

He drew a bundle of papers from his pocket, unfolded them, and turned the leaves rapidly.

"Here it is," and he read:

"Yes, I saw a glass of wine on the window-ledge. The colonel was in the habit of sitting in the window on summer evenings. I have often seen him there, and I knew when I saw the wine that he was near at hand."

He pushed the paper aside and looked keenly at the wretched man before him.

"She is seen by the gamekeeper, as I say," he went on, "and this man, attempting to intercept her, she struggles from his grasp and runs down the drive to the cab. The cabman says she was agitated, and when he asked her what was the matter, she replied that she had killed a man—"

"She meant the gamekeeper," interrupted Jack.

"She may or may not, but she made that statement. There are the facts, Jack; you cannot get past them. The letter from the lawyers—which she says she never read—the envelope was found open and the letter taken out; is it likely that she had not read it? The bottle of cyanide of potassium was found in her possession, and—" he spoke deliberately—"the colonel was found dead at his desk and death was due to cyanide of potassium. A candle which stood on his desk had been overturned by him in his convulsions, and the first intimation the servants had that anything was wrong was the sight of the blazing papers on the table, which the gamekeeper saw when he returned to report what had occurred in the grounds. There is no question what verdict the jury will return...."

It was a great and a fashionable trial. The courthouse was crowded, and the public had fought for a few places that were vacant in the gallery.

Sir Johnson Grey, the Attorney-General, was to lead for the Prosecution, and Penderbury had Jack Freeder as his junior.

The opening trial was due for ten o'clock, but it was half-past ten when the Attorney-General and Penderbury came into the court, and there was a light in Penderbury's eyes and a smile on his lips which amazed his junior.

Jack had only glanced once at the pale, slight prisoner. He dared not look at her.

"What is the delay?" he asked irritably. "This infernal judge is always late."

At that moment the court rose as the judge came on to the Bench, and almost immediately afterwards the Attorney-General was addressing the court.

"My lord," he said, "I do not purpose offering any evidence in this case on behalf of the Crown. Last night I received from Dr. Merriget, an eminent practitioner of Townville, a sworn statement on which I purpose examining him.

"Dr. Merriget," the Attorney-General went on, "has been traveling in the Near East, and a letter which was sent to him by the late Colonel Dane only reached him a week ago, coincident with the doctor learning that these proceedings had been taken against the prisoner at the bar.

"Dr. Merriget immediately placed himself in communication with the Crown officers of the law, as a result of which I am in a position to tell your lordship that I do not intend offering evidence against Ella Grant.

"Apparently Colonel Dane had long suspected that he was suffering from an incurable disease, and to make sure, he went to Dr. Merriget and submitted himself to an examination. The reason for his going to a strange doctor is, that he did not want to have it known that he had been consulting specialists in town. The doctor confirmed his worst fears, and Colonel Dane returned to his home. Whilst on the Continent, the doctor received a letter from Colonel Dane, which I purpose reading."

He took a letter from the table, adjusted his spectacles, and read:

"DEAR DR. MERRIGET,—It occurred to me after I had left you the day before yesterday, that you must have identified me, for I have a dim recollection that we met at a garden party. I am not, as you suggested, taking any other advice. I know too well that this fibrous growth is beyond cure, and I purpose tonight taking a fatal dose of cyanide of potassium. I feel that I must notify you in case by a mischance there is some question as to how I met my death.—Very sincerely yours, "CHARTRES DANE."

"I feel that the ends of justice will be served," continued the Attorney-General "if I call the doctor...."

It was not very long before another Crown case came the way of Jack Freeder. A week after his return from his honeymoon, he was sent for to the Public Prosecutor's office, and that gentleman interviewed him.

"You did so well in the Flackman case, Freeder, that I want you to undertake the prosecution of Wise. Undoubtedly you will gain kudos in a trial of this description, for the Wise case has attracted a great deal of attention."

"What is the evidence?" asked Jack bluntly.

"Circumstantial, of course," said the Public Prosecutor, "but—"

Jack shook his head.

"I think not, sir," he said firmly but respectfully. "I will not prosecute in another case of murder unless the murder is committed in my presence."

The Public Prosecutor stared at him.

"That means you will never take another murder prosecution—have you given up criminal work, Mr. Freeder?"

"Yes, sir," said Jack gravely; "my wife doesn't like it."

Today, Jack Freeder is referred to in legal circles as a glaring example of how a promising career can be ruined by marriage.

It is absurd to say that truth is stranger than fiction because, as everybody knows, fiction is the unstrangest product of life. That is to say, fiction would be very strange if it was not stranger. For if it had no novelty, it would be no better than the News-That-is-Fit-to- Print, which is just the dullest kind of printed matter (with the exception of the Theology section of a Free Library catalogue) that offends the eye of mankind.

There was a girl who lived in a tenement house in a very poor part of London, who used to pray to God every night that a nice clean dragon with blunt teeth would seize her and be starting to fly away with his prey, when there would appear upon the scene a young and beautiful man in shining armor, who would slice the head from the dragon and carry her off to a white castle on a purple hill where she would be arrayed in white garments by handmaidens, and given bread and milk in a golden bowl.

She never reached very far beyond that breathless preamble, leaving it to God to fill in the blanks of her imaginings and to supply an adequate continuation of her story—which she had designed as a non-stop serial, each chapter of which was to be more delicious than the last.

Her name was Verity Money, and her age was eighteen. She was very pretty, very slim, and childlike, both in her appearance and in her faith. Her uncle, for whom she kept house—there were two rooms and a kitchen, and she slept in the kitchen, which was warm and cozy—was a grim old market-porter intensely religious for eleven months and two weeks of the year, and somewhat unsober for the remainder. He was never unkind to the girl—indeed he was most lavish in his gifts, and had been known to present her with such undreamt of luxuries as a feather boa and a musical box.

For the other fifty weeks of the year he was a sober and taciturn man—you can picture him lean faced, with a fringe of gray whiskers, poring earnestly over the big print of his Testament and declaiming at length on the virtues of Paul and the vacillations of Peter, the girl, darning needle in hand, listening with every evidence of interest, but her mind occupied by visions of the mythological youth in glittering armor.

When Tom Money died, he left her about fifty pounds and all his furniture. He had been a careful man, and it was discovered that he had paid his rent in advance, and that there was still three years of unexpired tenancy.

So Verity Money lived alone, earning just enough by her needle to keep body and soul together, and was happy in her dreams, and as she had no women friends, she suffered no disillusionment. Her ideals had undergone a change, for a new factor had come into her life. The movies had opened a new world to her and shifted the angle of her visions. Now, she was a little girl with sunlight in her hair, with a slow dawning smile and little uplift of the big, serious eyes to greet the handsome stranger who had ridden into her picture from nowhere in particular. In fine, she adored Mary Pickford, and pinned a picture of that lady on the wall so that it was the first object she saw when she opened her eyes in the morning.

She would slip from her bed, carefully remove the print, and re-pin it above the mantelpiece. She could light the fire and wash the cups, spread the table and take her morning tea and bread and butter with a sense of companionship which was very precious to her.

Her heroes were no longer armed cap-ą-pie. They were handsome young men in sombreros and who wore sheepskin trousers. They rode fiery mustangs and earned a precarious livelihood by shooting one another with revolvers....

The war brought nothing of reality to Verity Money. The wilful murder on a small scale which was screened for her amusement was more real, more terrible, more thrilling than the grand murthering up and down the hundred-league line, eighty miles from her door, where day and night the guns of Flanders crashed and roared and massed ranks went down before the spraying fire of machine-guns.

The war dawned upon her slowly as one by one her customers dropped their orders. Her work was the finest embroidery on cambric and silk. There was plenty of sewing work to be had, but she could not make soldiers' shirts or stitch button-holes in such quantity as would give her a living wage. She was slow and careful, and the few button-holes she made were very beautiful indeed, but she earned exactly eightpence in two days.

She had exhausted much of the money which had been left to her, and there came a time when she had to reduce her expenditure to a point which gave her one square meal a day.

She had no friends. There was neither boy nor man in her life. Her lovers were living in the sunny places of the world, holding their wide-brimmed hats on the pommels of high Mexican saddles whilst they passed the time of day with lovely girls who wore divided skirts and rode astride.

One day she started to starve and nobody knew anything about it. If she had died, the coroner would have had some unpleasant things to say about moving pictures, because she had spent her last threepence to see a great railway picture where half the story was told in the cab of an engine and half in the bullion van, where train robbers and bullion guards took pot shots at one another with deadly effect.

On the second evening of her starvation she went to a house in Berkeley Square to deliver some d'oyleys. The lady was not at home, and nobody had orders to pay this girl with the curious pinched look in her face.

She came slowly down the steps of the house into the dark square, took a few steps, and staggered. Somebody caught her by the arm and pulled her to her feet.

"Hold up," said a voice, but she was beyond obedience, and the stranger lifted her in his arms as though she were a child and stood for a moment frankly embarrassed by the situation in which he found himself.

He looked helplessly around, then whistled to two bright points of light in the distance.

The taxi drove up.

"Take me to the nearest hospital," said the stranger.

"Middlesex?" suggested the driver.

The stranger hesitated.

"Is it near?" he asked cautiously.

"It's nearest if your friend is badly hurt," said the driver.

"That's just what I can't say," said the other.

"Put her in the cab," suggested the chauffeur, getting down; "there's an electric light inside."

"What a brain!" laughed the stranger.

He looked at the girl lying limp and white in one corner of the cab and whistled softly.

Then he pushed back his khaki cap and scratched his head.

"Now what is the matter with her?" he asked irritably—irritability is a natural condition of man in the presence of a sick woman.

"If you ask me," said the driver carefully, "she wants grub."

"Good Lord!" cried the soldier, startled; "food... hungry?"

The driver nodded.

"I've seen them symptoms before—I've driven a cab for twenty-eight years in London."

Still the rescuer was undecided.

"Drive around for a while and if she doesn't recover I'll tell you—then you can go hell for lick to the nearest hospital."

The car had hardly moved before Verity blinked open her eyes and stared, first at the cab and then with a frightened frown at the young man who sat on the opposite seat.

"Are you feeling better?" he asked.

She saw a soldier, indistinguishable from any other of the thousands who had passed her in the mist of her dreams. He was a good-looking mortal, as clean shaven as any cowboy or train robber or even as the blessed saint of England. His uniform was no different from any other, but the badge upon his collar was a bronze leaf.

She was seized with a sudden panic.

"Can I get out please?" she asked in a flutter.

"Sure," he nodded, "but we'd better have some food—I'm starving, and you've made me miss an appointment with a fellow of ours."

To say that she was horror-stricken at this last revelation, is to tell no more than the truth. She had never intruded her influence upon the machinery of society before. Not once, by any act, had she knowingly affected the plans or movements of others. She felt, as she looked at him with troubled eyes and parted lips, that no sacrifice she could make could be too great to repair the mischief which she had caused.

"I'm—I'm very sorry," she gulped; "I would buy you some supper, but—but...."

She went red and her eyes were moist and shining. The young man whistled again—but quite inside himself.

"We will have supper together," said he, with a smile.

So he brought her to a golden palace of splendor. She was not self- conscious and did not realize that she might be an incongruous figure in the midst of all this amazing luxury. He noted that she was neatly dressed and that she was very young—she saw only the clustering bulbs of light in the gilded ceiling, the snowy tables glittering with silver and glass, the gentlemanly waiters who spoke English so funnily, the flowers ... beautifully dressed ladies... some of them smoking.... She drew a long breath which was half a sigh and half a sob.

They brought her soup—thick white creamy soup and curly strips of crisp brown sole, and white slithers of chicken, and an ice and coffee. The man did not offer her wine, knowing instinctively that she would be shocked, and for this reason he denied himself the half bottle of Chablis his soul craved.

He tried to draw her, gently and tactfully, but it was not until he touched on the cinema as a method of filling up odd moments of waiting that she began to talk. He did not laugh, he did not even smile when she revealed herself, her dreams (this she did with a naļveté which brought a lump to his throat), and her illusions. He told her something of the untamed places of the world, of the country north of Edmonton, of the forest of Ontario, of lumber camps on the Kootenay lakes, and of Alberta.

"Are you—you aren't American?" she asked suddenly.

He smiled.

"I am Canadian," he said, "but that is near enough."

She looked at him in awe.

"Do you have cowboys and—and things like that?" she asked. "I mean... is it dreadfully rough there?"

They sat until they were the last people in the restaurant and the waiters stood about them in silent reproach, and in that time he had learnt all there was to tell about her. He learnt, too, of the lady in Berkeley Square who had ordered d'oyleys and had not paid. Then he drove her home by way of the square.

"Lady Grant is a friend of mine," he lied, "and she would like me to see that you were paid—I will go in and get the money."

"Her name is Lady Grey," corrected the girl timidly.

"Didn't I say Grey?" he asked in surprise.

Though she protested that her client should not be disturbed at that hour of the night, he insisted; and stopping the cab some distance from the house, he disappeared into the darkness, returning in triumph with a whole pound note.

"Lady Green asked me to say—" he began.

She looked at him in consternation.

"You went to the wrong house!" she whispered in horror; "oh, you must go back, please! It was Lady Grey—"

He groaned in spirit.

"Lady Grey asked me to say," he went on patiently, "that you—"

"But you said 'Green,'" she protested.

"I did not mention the fact," he answered gravely, "but I am color blind—I always say Grey when I mean Green—anyway, she said the work was so well done that she would like you to accept a little extra...."

All the way to her rooms on the south side of the river she was one babble of gratitude and adoration; Lady Grey was so kind, so generous, so good.

He caught himself yawning.

He went back to his hotel that night singularly thoughtful. A lean man from Toronto sprawling on the settee in the vestibule of the hotel rose up to meet him, and Private John Hamilton met his disapproving eye with a guilty smile.

"I waited till nine o'clock for you at Frascati's," growled the man from Toronto, clipping his canvas belt together, "you're the darnedest old—"

"Gee, Corporal, I'm sorry!" said the young man humbly, "but I met—my—er—cousin—and she—I mean he—well, he insisted—"

"Don't you try to put anything over me," warned the other, stretching himself. "I wouldn't have waited up for you, but I've seen the Colonel—he's going back tomorrow."

He looked round and lowered his voice.

"There's to be a big attack this week," he said, "and the Canadians will be in it. I've made my will," he added.

Hamilton looked at his lank friend with a twinkling eye.

"You're a cheerful soul," he said.

"Yep," said the other complacently. "I've left twenty-four dollars seventy-five cents, and any balance due from my army pay, to three lawyer fellers in Toronto."

He elaborated the scheme of his will, which with any good fortune must lead to endless law suits.

"I hate lawyers worse'n poison," he said, "and I guess I shall be as cheerful as any poor guy that goes west this week."

Hamilton was a long time getting to bed that night. He wrote a letter to his agents in Montreal and one to the manager of his office at Toronto—he was Hamilton of the Hamilton Steel Corporation before he became No. 79743, Private Hamilton of the 40th Canadian Infantry—and another to his London banker.

For an hour he sat on the edge of his bed, his hands thrust deep into his pockets, thinking.

At two o'clock in the morning he rang his bell and demanded of the astounded night porter the address of the Archbishop of Canterbury. The request was received tolerantly by the porter as an example of youthful good spirits. When the young man angrily persisted, the porter diagnosed the case as one of truculent intoxication and went in search of a reference book.

Verity Money had never received a telegram in her life and had no idea who "Hamilton" was. It was an imperative telegram ordering her to meet the said Hamilton at Marble Arch at three o'clock.

She obeyed the summons meekly, for it would have been flying in the face of Providence to disregard a message upon which nineteen cents had been spent.

In truth, she never suspected the identity of the sender, and puzzled her little brain to recall the Mrs. Hamiltons and the Misses Hamiltons who had swum majestically into her placid sea, had thrown overboard instructions and orders for embroidered nightdress cases and pillow-slips, and had as majestically retired.

She was dressed very plainly and very neatly in black, and could have found no more attractive setting to her undeniable beauty, for she was fair and petite, with a complexion like milk and hair of spun gold. Her big gray-blue eyes, her firm little chin, her generous mouth—all these details Hamilton took in as he came forward to meet her. She was frankly and unfeignedly surprised and glad to meet him. He had joined the angels, did he but know it, and was one with St. George and Bronco Billy and other great heroes.

"I want to talk to you," he said brusquely, and looked at his wrist- watch. "We have only a quarter of an hour."

He led her to a seat in the park under a big oak. They were free from interruption but, as the girl was relieved to discover, within call of the police.

"My name is Hamilton," he said, without any further preliminary, "and I am going back to the front by the six o'clock train."

She nodded and looked at him with a new interest. He was going back to the front! It seemed rather splendid and she regretted that she had not paid closer attention to the war. But then, of course, she had not known that he was in it, and that all the bombardments, charges, minings, and bombings had been either designed to destroy him, or to rescue him from danger. For the first time she felt a sense of personal animosity against the German Emperor.

"Now, I want to say this," he went on carefully, choosing his words and speaking slower than was his practice, "I have no relations in the world, and if I am killed nobody will be very miserable."

"I should be—awfully," she said, with an eagerness that brought a smile to his tanned face.

"I am sure you would," he said gently, "and that is what I want to speak about. You see, a man is always sorry for himself. The thought of dying and not being able to continue being sorry for himself is one of the most dreadful thoughts his mind can hold. You've read that in books, haven't you?"

She was doubtful, but admitted that she had often read of people who were quite bitter at the prospect of nobody being unhappy when they died.

"Well," he said, after a pause, "I want you to be unhappy—"

"But I shall be," she insisted, and he laughed again.

"I want you to have the right to be unhappy," he said; "naturally, I don't want to put people who aren't—related—or connected with me to a lot of trouble—so I thought it would be a good idea if you married me before I left."

"Married you?" she said blankly, and stared at him.

He nodded.

"But I—I couldn't marry you, could I—without being your wife?"

It was an insane question and she knew it, but for any words she could utter, she was grateful enough. She found speech almost a physical impossibility, and was amazed that she could speak at all.

"I have a special license," he said deliberately, "and I have a parson waiting. If you will marry me we shall have time for a meal before I go."

"But—I don't think I love you," she faltered, "and that wouldn't be right—would it?"

"I don't want you to love me," he said loudly; "all you have to do is to marry me and be sorry."

"Oh!"

She looked round helplessly.

She could hardly call the policeman to assist her in coming to a decision, and yet she felt the need of legal advice.

"I don't know what to do," she said at length, "I've never been—nobody has ever asked me—suppose I were your—your sister, what would you advise?"

"Come and be married," he said practically, and rose.

At five o'clock she stood upon the platform at Charing Cross Station and waved adieu to the man whose name she bore.

She waited until the train was out of sight, gently twisting the gold band upon her finger, and then with a little lift of her chin she came out to the crowded courtyard.

"Cab, miss?"

She looked at the porter a little frightened, and then with no small amount of dignity inclined her head.

The cab drew up.

"Where do you want to go, miss?" demanded the driver.

"Mrs. John Hamilton!" said the girl and grew for a moment incoherent. "I mean—oh, Hagan's Rents, please!"

Verity Money learnt much from books. Even by cultured standards she was well read, but she found neither in Dickens, nor Dumas, nor in the efforts of the modern authors any situation analogous to her own. Nor did the cinema help her, though she indulged in a systematic search for parallels.

She had letters from her husband—kindly, brotherly letters. He had been in a big fight, and had come out without a scratch, though his friend ("you remember the Corporal who was at the church?") had been severely wounded, though he was now on the way to recovery. Was she well? Did she receive her allowance regularly? Had she moved as he suggested to the furnished flat he had urged her to take?

She answered his letters in a firm, childish hand, perfectly punctuated, and to his surprise and relief not only literate but literary in the sense that they conveyed a freshness and a clarity of view which was little short of marvelous.

"I shall try to be a good wife to you," she wrote, "and I am already reading the newspapers carefully. I have written to Lord Kitchener—"

He sat back on the step of the trench and gasped—then he laughed and laughed till the tears rolled down his face.

"I have written to Lord Kitchener to ask him when the war will be over, and he has written to me saying that he isn't sure, but he will let me know. I hope our marriage isn't a mistake, but I will try to be worthy of a hero who is fighting for his country. I have a picture of a Canadian soldier, and I am learning to sing 'The Maple Leaf.' I went to the flower shop in Regent Street and asked them if they had any maple leaves, but they had none. It was so silly of me, but I did want to buy some."

When John Hamilton came out of the trenches he went to No. 8 Base Hospital and saw a certain swathed and bandaged corporal, and discussed matters.

"Well, Don Quixote, and how is Mrs. Don?" asked the voice behind a large square of medicated gauze.

John sat on the bed and read extracts from the letter.

"I thought you were crazy," said the wounded man, "but I guess you've instinct. There's the making of a woman in that child. You're not feeling sorry for yourself?"

"On the contrary, I'm looking forward to life—it has possibilities," said the other.

Verity Hamilton in the Baker Street flat, with a maid of her own, was a serious little figure facing those possibilities for herself.

She adored her ten-minute husband because she was made to adore those who were kind to her. She prayed for him, she evolved great plans for his future, and she fought hard against the pin-point of doubt which had come into her mind and which was growing with every day which passed.

In a sense he had fulfilled her ideals and her dreams, for he had come violently into her life and had in a sense saved her from destruction. At any rate he had given her food when she was very hungry. And then she had seen him again—and whisk! she was married!

She used to sit with compressed lips, and eyes that were fixed in the far-away, wondering—and doubting.

He could not love her: he had never said that he did. He had not so much as kissed her, and it was only the strong grip of his hand that she remembered.

Her problem was a simple one. She loved her husband and he did not love her. Why he had married her she did not ask herself, curiously enough. Who was she to inquire into his godlike whims?

How could she make her husband love her? That was the problem, and presently a fortuitous visit to the movies told her.

Four months after his marriage, John Hamilton was sent to England on sick leave pending his discharge. The shrapnel bullet which was responsible for so much left him with a perceptible limp, and there was a big chance that he might rid himself of all traces of his wound (so the army doctors told him), but it would take time.

He arrived at Southampton in the early hours of a spring morning, and telegraphed to his wife that he would be staying at the Cranbourne Hotel and that he would call and see her.

He expected she would be waiting for him at Waterloo, but here he was disappointed and a little hurt. Yet—he had heard something of the commotion she had caused at the War Office when the news of the wounding had come through; of how she had appeared armed with a letter authorizing her to call upon a high personage. Being somewhat vague as to her husband's position in the army since he had been promoted to lance-corporal, she had described him as "Colonel," which accounted for her facilities.

And she had demanded to be taken at once to the Holy of Holies to meet the steel-eyed man from Khartoum, and had wept on the breast of a flustered field officer when that permission had been gently denied her.

All this John Hamilton had learnt, and, lying on his back in the Versailles hospital, had chuckled the morning through at the recital.

Perhaps she had a surprise for him? She had indeed.

When he came to her flat the maid opened the door expectantly and primly.

Would he go to the drawing-room—Mrs. Hamilton was waiting.

The drawing-room door was opened and he was announced. He did not hear the door close behind him, for he stood out of breath and speechless looking down at the girl.

She was seated in a low chair before the fire, and on her knees lay a tiny pink-faced thing that scowled and spluttered and stared into space.

"My God!" whispered John Hamilton.

She looked up at him serenely with that smile which was peculiarly her own.

"Isn't he lovely?" she whispered.

John Hamilton said nothing.

"Whose—whose baby is that?" he managed to say at last.

"Mine," she said gravely.

"Y-yours—how old is it?" he asked, a cold sweat of apprehension breaking over him.

"Two months," she said.

He sat down heavily and she looked across at him with growing distress.

"Oh dear—please, aren't you glad?" she pleaded. "I thought you would be—"

He glared from the child to Verity and from Verity to the child, and then he laughed, but it was not a happy laugh.

"What an ass I am!" he said, half to himself. "What a stupid blind fool!"

The tears were standing in her eyes, tears of disappointment and chagrin. She was hurt—he saw the immeasurable pain in her eyes and was kneeling by her side in an instant.

"My dear, my dear," he said softly, "I am an awful brute—but it was such a surprise and I had no idea—"

"I thought—it would make you so happy," she sobbed. "I wanted you—to love me—and children bring people together as nothing else does—I've seen it in stories and things."

He patted her hand.

"Yes, dear—but this is not—my child."

She looked at him open-eyed.

"Of course it is your child!" she cried.

John Hamilton rose unsteadily.

"I think—I rather think you're wrong," he said, his head whirling.

She laid the unconscious cause of her unhappiness upon the downy deeps of the big arm-chair and faced him, her hands clasped behind her back.

"It's no use trying," she said brokenly. "I thought you would love a little baby about the house—I'll have to send it back."

She covered her face with her hands.

"Send it back!" he gasped.

He took her by the wrists and gently pulled her hands apart.

"I—I was going to adopt it," she gulped. "I have it on a week's—a week's trial—"

He took her in his arms and his laughter filled the flat with joyful sound. The baby on the sofa, scenting disaster for itself, opened its little red mouth very wide, screwed up its eyes into the merest buttons and added its voice to the chorus.

Sylvia Crest walked back to her surgery, her quick steps beating time to the song of triumph in her heart. She had declined Jonas Picton's offer to send her home in one of his many cars. Walking, movement of any kind, physical action she wanted to work down the bubbling exuberance which was within her. So she swung down the hill from the big house and through Broadway into busy Market Street, and people who knew her and who observed the lifted chin and the light in her eyes, saw Tollford's one woman doctor as a new being. They saw, though this they could not know, merely the reaction from months of depression bordering upon despair, months of waiting when her most precious quality, her faith in herself and her invincibility had been gradually shrinking until she had almost lost hold.

For she had thrown down the gage to the town of Tollford, and until this morning the glove lay moulding where it fell.

If Tollford had not been founded a couple of hundred years before the birth of Jonas Picton, it might and undoubtedly would have been known to history as Pictonville. It is on record that Jonas offered pretty substantial inducements, including the building of a new Town Hall, the presentation of a town park, and the equipment of a new Fire Station to induce such a change of name; but Tollford was more conservative in those days before Picton's tall smoke stacks stabbed the skyline east and north, and his great glass-roofed factory buildings sprawled half-way down the valley.

And when the Picton works, and some eight thousand Picton employees, had become so important a factor in the municipal life of Tollford, Jonas had outgrown the desire for advertisement and had found life held something bigger than the flattery of a purchased honour.

Yet, in every other sense, Tollford remained conservative. Strangers who came and surveyed the town and marked it down as easy, who saw gold lying on the sidewalks waiting to be lifted, and returned joyously to show Tollford how much better stores, theatres, and newspapers could be run—these people lost money.

Dr. Sylvia Crest had come straight to Tollford from Mercer's Hospital, her diploma painfully new but her heart charged with confidence. She, too, had surveyed the land and had duly noted the poverty of medical resources in the town. Of women doctors there were none—and there were at least four thousand women employed at Picton's. She sat down the night following her visit to Tollford, and, with a pencil and paper and the local health statistics before her, she took stock of opportunity and found the prospects beautiful.

So she arrived one dull day in February, rented a corner house, furnished her rooms with proper severity, put up her sign, and waited. The local newspaper man gave her a most outrageous puff, for Sylvia was pretty—the prettiness of regular features and a skin like silk; but, brazen sign and as brazen advertisement notwithstanding, few patients sought the advice of the new doctor.

Tollford was conservative.

Moreover, working women did not like women doctors. About the female of the medical profession all manner of legends circulated. Women practitioners (by local and even more general account) did not treat women as kindly as men doctors. They were liable to fainting spells, and think what would happen if, in the middle of a critical operation, the doctor needed medical attention!

All these things were said and agreed upon in the lunch hour at Picton's, when the women talked over the new arrival.

"I'd as soon die as have a woman doctor fussing round me," said one oracle, and her light-hearted preference for death before the attentions of one of her sex was endorsed with unanimity.

A haggard and droop-lipped Jonas Picton sitting in his ornate office at the works had heard of Dr. Sylvia Crest, and sighed. Where the great Steyne, most famous of modern physicians, had failed to find any other remedy than the knife, and offered even that dread remedy without assurance of cure, what hope could a "bit of a girl" bring? His secretary had pointed her out to him once when he was driving through Tollford. And yet one day in sheer desperation he had sent for her. The messenger had come at a moment when Dr. Sylvia was facing, perilously near tears, an accumulation of bills which called for an earlier settlement than her bank manager could sanction. No wonder that the sun shone more wonderfully, and the homely folk of Tollford took on a foreign charm under her benignant eyes as she made her way homeward.

Alan Brock was waiting in her study, and the hearth she had left clean and tidy was strewn with his cigarette ends. She looked suspiciously at him as she came in, his face was more yellow, his appearance more untidy than usual, and he had not shaved.

He was the one doctor in Tollford who had given her welcome—he was more presentable the first day he had called upon her—and she had been grateful. She did not realize until later that in seeking her out he had advertised his belief in her failure.

Alan Brock had neither friend nor practice in Tollford, and for good reason.

She took off her wrap, her disapproving eyes upon the figure sprawling in the one easy-chair she possessed.

"Doctor Brock, you have been taking morphine again," she said severely.

He chuckled, stretching out his hand to flick away the ashes of his cigarette. "I must keep one patient, you know," he grinned, "to alleviate suffering, to restore vitality—what used old Professor Thingummy say were the three duties of medicine?"

She smiled.

She was too elated to take anything but a charitable view even of one whose acquaintance she was determined to drop.

"Why don't you go away from here?" she asked. "You need not be a doctor—"

"The good people of Tollford make it obvious," he growled.

"You have money," she went on; "why stay here where—" She stopped, and he looked up.

"Where I'm not exactly respected, eh?" he asked. "Well, there are several reasons, and you're one of them."

"Me?" she was genuinely surprised.

He nodded.

"Yes, you. Do you know, Sylvia, doctoring isn't your line. You haven't the temperament for it, for one thing—it's a horrible profession for a woman, anyway."

Her lips were set tight now.

"That isn't the view you took a month ago, Dr. Brock," she said, and he waved his hand feebly.

"A few weeks ago I wanted to know you and I wasn't such a fool as to start right in telling you your faults. Sylvia, you and I are both hopeless failures."

He rose unsteadily and reached out his hand. Had she not moved quickly it would have rested on her arm.

"I want you to listen to me, Dr. Brock," she said quietly. "There is nothing in our relationship which justifies your calling me by my Christian name. There is, I am sorry to say, very little in our common profession which makes a continuance of our friendship possible or desirable—even the communion of failure has no attraction for me."

He was standing by the table, swaying slightly. The effect of the morphine was beginning to wear off and his face was drawn and haggard. He muttered something and sank back to his chair. Then lifting his sunken head with an unexpected alertness:

"Look here," he said, "I've got money, that's true. I tell you I'm mighty fond of you, and that's true also. Why don't you throw up this business and come away? It would make a new man of me, Sylvia."

She shook her head.

"Supposing I was fond of you, which I'm not, marrying a man to reform him would be a pretty thin occupation; and, honestly, I don't think you're going to be cured."

"You're certain about that, are you?" he said, with an ugly little smile.

"Do you realize," he asked suddenly, "that you're certain about almost everything?"

He was surprised to see the red come into her face. Later he was to learn the reason why.

"I'm sorry," he said humbly. "Don't let us quarrel—anyway, I'm leaving this hole. How did you get on this morning? Did you see the kid?"

"I saw the child," said the girl.

"Well?" He was looking at her queerly. There was something skeptical and challenging in his attitude which annoyed her, until she remembered that there had been a time when this broken man had been Picton's family doctor.

"I saw the child," she said again, "and I think that the trouble is local—in fact, I am certain." She cut the word short, as though it had slipped out against her will, and again she flushed.

"You think the spinal trouble will yield to treatment—in fact, you're certain, eh?" he said slowly. "Well, you're putting your opinion against the biggest expert."

"I realize that," she replied; "but I must say what I believe. I gave the child a thorough examination; she's a pretty little girl, isn't she? I am satisfied that with massage and fairly simple local remedies, the swelling on the back can be absorbed."

Brock was silent. He sat with his chin on his hands looking into the fire.

At last he broke the silence.

"And naturally old man Picton fell on your neck and blessed you."

She looked at him in surprise.

"He was rather grateful—why?"

"Because," said the other grimly, "that's the kind of verdict he's been trying to get for years. Jonas Picton hates the knife. His wife died on the table. His mother died in similar circumstances, and I believe one of his sisters had a very unhappy experience at the hands of a fashionable surgeon. It is just the knife that he wants to avoid, and naturally he believed you and was glad to swallow everything you told him. Do you know what you are, Sylvia? You're the straw, and he clutched you!"

The girl repressed her irritation with an effort.

"I gave what I believe to be an honest opinion," she said.

Dr. Brock had reached out his hand and taken a book from the bookcase and was looking at it idly. He turned the cover.

"S.A.C.—your initials," he said. "'Sure and Certain,' eh?" He laughed.

This time she made no attempt to conceal her anger.

"You are not quite as original as you think, Dr. Brock," she said, her lips trembling. "Those initials have been interpreted that way before by a man who would be a little more competent than you to sit in judgment on my diagnosis."

"Who is that?" he asked in surprise.

He had reached the stage in morphiomania where he found it impossible to take offense at rebuffs more pointed than Sylvia Crest's.

"John Wintermere," she said shortly, and he whistled.

"I remember," he said softly. "I heard some story about it from Mercers. He was rather sweet on you, wasn't he, and you had an awful row with him when you were a student, and—"

The girl had opened the door.

"If you will excuse me now, Dr. Brock, I shall be very glad to have this room," she said. "I am expecting some patients."

"Wintermere, eh?" He rose slowly, groping for his hat. "Good chap, Wintermere. He's married now, isn't he?"

He saw the girl's face go white.

"Married?" she faltered. "I don't know—perhaps—at any rate, it's no business of mine."

He chuckled. The effect of the marriage invention on the spur of the moment satisfied him.

"Perhaps he isn't—now I come to think of it. I was wrong to say he was married. Scared you, didn't it?"

She made no answer.

He turned at the door of the little house. "Jonas has taken you up and you'll get all the patients you want now, but, take my advice, combine business and pleasure by getting John Wintermere down to see Picton's kid. Picton has funked sending for him, though he knows Wintermere's opinion is the last word on spinal trouble—"

The door was slammed viciously in his face.

It seemed almost as though Brock's prophecy was to be fulfilled. As if some secret courier had run from house to house telling Tollford that the new woman doctor was under the sublime patronage of Jonas Picton and was no longer to be avoided. Patients appeared miraculously. Never before had Dr. Sylvia Crest's waiting-room been so crowded as it was that night.

She called the next day at the big house to see her little patient. Picton's car was at the door, and, as she walked up, the big man was pulling on his gloves in the hall and greeted her with almost pathetic eagerness.

"Just come into the library, doctor," he said, opening a door. "I want to talk to you about Fay."

He ushered her into the room, closed the door behind her, and lowered his voice.

"I didn't tell you yesterday, doctor, that I had consulted Dr. Steyne. You've heard of Steyne?"

Sylvia nodded.

"I have heard of him," she smiled, "and I also know that you've consulted him."

Picton looked relieved.

"I'm glad to hear that," he said. "Somehow I didn't like telling you for fear"—he laughed a little nervously—"for fear the knowledge that Steyne had seen her would influence your opinion. You know that he takes a different view from yours? He calls the disease some infernal long name and says that it cannot be cured save by an operation, and that it is extremely rare that such operations are successful. Sit down, won't you?"

He followed her example, stripping off his gloves as he spoke, and gaining something of the animation and forcefulness which Tollford associated with his dominating personality.

"There's another man, Wintermere," Picton went on. "You've heard of him?"

"I've heard of him," said Sylvia steadily.

"Well, they wanted me to bring him down to see the child, and I've heard that he's a pretty clever man. I met him when I was on my vacation, and he seems a very clever fellow, though a bit young looking for a specialist."

The name of John Wintermere invariably annoyed her. Today, with the memory of Brock's gibes so fresh in her mind, there was sounder reason for her irritation. But John Wintermere had been her master in surgery, and common decency demanded a testimonial.

"I don't think I should be deceived by his youthful appearance, Mr. Picton," she said. "I think he is the greatest surgeon in this country."

Jonas Picton pulled a wry face.

"I don't want any great surgeons," he said shortly. "I want a cure without surgery. And you think you can do it, don't you?"

Only for the fraction of a second did Sylvia hesitate.

"Yes, I think so, yes, I am cer—I am confident I can cure the child," she said, and if he noticed her confusion of terms he made no comment.

He rose quickly and gripped her arm with his big hand.

"My friend," he said, and his voice was a little shaky, "put my girl right and you shall never regret having come to Tollford."

Sylvia went up alone to the room of her patient, and she seemed to have lost something of the sprightliness of mind with which she had greeted the day.

In a large room chosen for its situation because its windows offered no view of her father's commercial activities, was the center and soul of Jonas Picton's existence.

"Hello, Miss Doctor!" said a cheery voice from the white bed, and Sylvia went across to her patient and took the thin hand in hers.

Fay Picton was seventeen and a prodigious bookworm; books covered the table by the side of the bed and filled two long cases which ran the length of the room. She was a pretty, fairy-like thing who turned big, smiling eyes to the newcomer.

"You're the first interesting doctor I've had," she said, "and I've had a lot. Your name is Sylvia, and it's what I'm going to call you. I couldn't tell you this yesterday because Daddy was here, and I had to appear impressed by all that stuff you were talking."

"And weren't you impressed?" smiled Sylvia, as she sat by the bed.

"Not a dreadful lot," said the girl, with disconcerting frankness. "You see, I know much more about my unhappy case than you or Daddy. I've read a lot about it."

But Sylvia was nettled. To suggest the fallibility of the young is outrageous.

"You ought not to have read any medical books," she said severely.

"Oh, skittles," said the patient contemptuously; "you don't suppose they'd let me have medical books, do you?"

"Well, where did you read about it?"

"In the encyclopędia, of course. Everything's in the encyclopędia, isn't it?"

Sylvia, for the first time in her life, was genuinely embarrassed.

"Well, anyway, we're going to cure you," she said cheerily, and Fay Picton laughed quietly.

"Of course you're not going to cure me," she said calmly. "This thing is more or less incurable. The only remedy is an operation, and there have been just four cases where an operation has been successful. Only Daddy shrieks inside himself at the very idea—poor soul!"

This was not exactly the start which Dr. Sylvia Crest had expected. She was dismayed at the thought that her task was to be doubly difficult and that she had two fights to wage—one against the disease and one against the skepticism of this self-possessed young person.

"You see, doctor dear, the spine and all its eccentricities is terra nova to the poor doctor," the patient went on remorselessly. She stopped suddenly as she saw the look in Sylvia's face. "I'm awfully sorry." She put out her hand and laid it on Sylvia's knee. "Anyway, it doesn't matter; do your best and come every day and talk to me, and I'll pray hard for faith in your treatment."

That was the beginning of the curious and torturing friendship which shook the self-confidence of Sylvia Crest more than the admonitions of professors or the jeers of Alan Brock.

"Fay is quite brightening up under the care of that woman doctor," Picton told his cronies, his managers, and the few who enjoyed the privilege of intimate friendship with him. "Never saw her looking so cheerful, my boy."

One afternoon Sylvia went in haste to her patient, obeying an urgent telephone summons from the nurse, and found the girl lying on her side, haggard and white, with a queer little smile on her face.

"Doctor, darling," said Fay, "send that gaunt female out of hearing and I'll tell you something."

Sylvia dismissed the nurse.

"Bend down as they do in books," whispered the girl, with a little laugh that ended in a grimace, "and I will tell you my guilty secret."

"What is wrong, dear?" asked Sylvia.

She was in a panic—an unreasonable, fearful panic—and there was need to exercise control, lest her voice betrayed her. The girl's bright eyes were fixed on hers, and there was elfish laughter struggling with the pain in her voice.

"If we could have a little slow music," she whispered, "I think it would be appropriate. Sylvia, you won't let that raw-boned creature weep over me, will you?"

"For God's sake, Fay, be quiet," said Sylvia hoarsely. "What are you talking about?"

"I'm going to glory," said the girl. "I sort of know it."

"Let me see."

Sylvia's hand trembled as she examined the spine. The tiny swelling which it had been her daily care to reduce had grown ominously, and there were other certain symptoms which could not be ignored.

Jonas Picton, called from a board meeting, came back to the house and listened in silence whilst Sylvia told the new development.

He seemed to shrink visibly at the telling, and when he spoke his voice was husky.

"I—I had a lot of confidence in you, doctor," he said. "Do you think—do you think there is anything to be done—"

Sylvia was silent for a while. But he might have foretold her answer in the sudden stiffening of her body and the upward throw of her chin.

"I still have faith in my treatment," she said.

He did not speak again, but sat on the edge of his chair, his head bent forward, his fingers twining, and then without a word he rose and went up to the girl's room.

Sylvia did not follow him. Somehow she knew instinctively that he wished to go alone. She waited for ten minutes and then he came back. He did not look at her, but walked to the window and stared out. Presently he turned.

"Who is the best surgeon in this country?" he asked.

"John Wintermere of Mercer's Hospital," she replied.

He nodded and went out of the room. Then he came back and opened the door wide, but he did not come into the room, nor did he look at her.

"You'd better go up and see Fay," he said. "I've telephoned to Dr. Wintermere, and he will be here this evening."

Sylvia Crest walked heavily up the stairs. She had heard the doom of her professional career, as though it were pronounced by a judge.

Fay lay with her face turned to the door, and as the girl entered she beckoned her.

"I had to do it, Sylvia darling," she said. "You don't mind me taking liberties with my staid old family doctor?"

She took the older girl's hand between hers and fondled it.

"Had to do what, dear?" asked Sylvia quietly.

"I had to tell him to send for Wintermere."

"You told him?" said Sylvia in surprise.

The girl nodded.

"You see, I've been thinking things out, and it occurred to me that I might be the fifth case in history, and really, for poor Daddy's sake, I ought to take a chance. You don't mind, do you, not really?"

Sylvia stooped and kissed the girl.

"No, dear," she said.

"It means a tremendous lot to you, in your profession, doesn't it, I mean your—your—" Fay checked the words.

"My mistaken diagnosis," finished Sylvia, with a laugh. "Yes, I suppose it does, but it means more to me that you should have the best treatment, irrespective of my fine feelings, and even though the treatment is contrary to my idea of what is right."

Sylvia waited at the house the whole of that afternoon, and she was alone in the drawing-room when John Wintermere came. She had nerved herself for the meeting, and was in consequence more cold and more formal in her attitude than she intended.

He walked slowly across the room to her, and it seemed as though the passage of six years had made no alteration in the disparity of their relationships. He was still the professor, she was still the student, though she felt she had grown older at a faster rate than he. But he was also the man who had held her hand one sunny day in the hospital gardens and had spoken incoherently of love, urging her to drop the profession to which she had dedicated her life. Perhaps the memory of this added to the awkwardness of the meeting.

"I'm glad to see you again, Sylvia," he said in that soft voice of his. "It is curious I should be called into a case of yours. Won't you tell me about it?"

She did not resent the "Sylvia." It came so naturally and rightly, and, in the detailing of Fay Picton's case, her nervousness wore off. He listened gravely, interjecting now and again a question, and when she had finished he heaved a long sigh.

"Well?" she challenged.

He hesitated.

"It may be what you think," he said, "but it seems to me that the symptoms suggest a series of complications. Have you"—he hesitated again—"have you offered a definite opinion?"

She nodded.

"Did you tell Picton that the case would yield to your treatment?"

She nodded again, and his face lengthened.

"So if the opinion I give is in contradiction to yours...?"

She shrugged her shoulders.

"If that is the case," she said, "I shall regret not having followed the advice you offered to me six years ago."

He was looking at her thoughtfully.

"It would mean ruin for you, of course," he said. "I—I wish I had not been called in."

"That's absurd, Dr. Wintermere," she said sharply. "Personal friendship and that sort of thing—I don't mean friendship," she went on confused, "I mean—"

"I know what you mean," said Wintermere. "Will you take me up to the child?"

Jonas Picton was in the room when they went in, and he remained by one of the windows whilst the examination was in progress. After a while Wintermere rearranged the bedclothes.

"Well?" said Fay, looking up into his face, with a smile; "to be or not to be?"

He smiled back at her and gently twigged the end of her nose.

"That is the privilege of an eminent specialist," he said gravely.

"To be or not to be?" persisted the girl.

"Fay, Fay, don't talk about such things." It was her father who had come to her bedside and had taken her little hand in his. "Don't talk about things so flippantly, darling. You hurt your old Dad."

Then with sudden resolution he looked across the bed to Wintermere, and asked harshly:

"Is an operation necessary?"