RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

The Admirable Carfew, 1920's Reprint

The Admirable Carfew, Ward, Lock & Co., London, 1914

The author gives pleasantly a series of important phases in the life of an irrepressible young man, Carfew, whose ready wit and daring and downright "front" carry him through anything and everything. Carfew volunteers for any kind of forlorn hope in business, and usually wins handsomely. The sketches of this tornado of energy are done brightly; even a languid reader will be hurried along gladly. He would be a sad man who would not be obliged to laugh heartily at some of Carfew's "turns."

IT was an idea; even Jenkins, the assistant editor, admitted that much, albeit reluctantly. Carfew was an erratic genius, and the job would suit him very well, because he had a horror of anything that had the appearance of discipline, or order, or conventional method.

In the office of The Megaphone they have a shuddering recollection of a night in June when the Panmouth Limited Express, moving at the rate of seventy miles an hour, came suddenly upon an excursion train standing in a wayside station beyond Freshcombe.

The news came through on the tape at 5.30, and Carfew was in the office engaged in an unnecessary argument with the chief sub-editor on the literary value of certain news which he had supplied, and which "the exigencies of space"—I quote the chief sub, who was Scotch and given to harmless pedantry—had excluded from the morning's edition. Carfew had been dragged to the chief's room, he protesting, and had been dispatched with indecent haste to the scene of the disaster.

"You can write us a story that will thrill Europe," said the chief, half imploring, half challenging. "Get it on the wire by nine, and, for heaven's sake, give your mind to the matter!"

Carfew, thinking more of his grievance against an unwholesome tribe of sub-editors, who, as he told himself, suppressed his copy from spite, had only the vaguest idea as to where he was being sent, and why.

The flaming placard of an evening paper caught his eye— "Railway Disaster"—as he flew through the Strand in a taxi-cab, and then a frantically signalling man on the side-walk arrested his attention.

"Hi—stop!" shouted Carfew to the driver, for the signaller was Arthur Syce, that eminent critic.

Now, it was rumoured that there was some grave doubt as to the authenticity of the Ribera Españolito, recently acquired by the National Gallery, and Carfew was hot for information on the subject. Indeed, it was he who had planted the seeds of suspicion concerning this alleged example of the Spaniard's work.

The great news agencies sent in their disjointed messages of the railway smash—they came by tape-machines, by panting messengers, by telegrams from the local correspondents of The Megaphone at Freshcombe—but there was no news from Carfew. Ten o'clock, eleven o'clock, eleven-thirty—no news from Carfew. Skilful men at the little desks in the sub-editors' room, working at fever speed, pieced together the story of the accident and sent it whizzing up pneumatic tubes to the printer's departments.

"If Carfew's story comes in, use it," said the despairing chief; but Carfew's story never came.

Instead came Carfew, with the long hand of the clock one minute before twelve,—Carfew, very red, very jubilant, almost incoherent in his triumph. "Hold half a column for me!" he roared gleefully. "I've got it!"

The editor had been leaning over the chief-sub's desk when Carfew entered. He looked up with an angry frown. "Got it? Half a column? What the devil have you got?"

"The Spaniard is a fake!" shouted Carfew.

He had forgotten all about the railway accident.

If he had not been a genius, a beautiful writer, a perfect and unparalleled master of descriptive, he would have been fired that night; but there was only one Carfew—or, at least, there was only one known Carfew at that time—and he stayed on, under a cloud, it is true, but he stayed on.

Newspaper memory is short-lived. Last week's news is older than the chronicles of the Chaldeans, and in a week Carfew's misdeed was only food for banter and good-humoured chaff, and he himself was sufficiently magnanimous to laugh with the rest.

When the dead season came, with Parliament up and all the world out of town, somebody suggested a scheme after Carfew's own heart. He was away, loafing at Blankenberghe at the time, but a wire recalled him: "Be at office Tuesday night, and follow instructions contained in letter."

"To this he replied with a cheery "Right O!" Which the Blankenberghe telegraphist, unused to the idioms of the English, mutilated to "Righ loh." But that by the way.

"Do you think he will understand this?" asked the editor of his assistant, and read: "You will leave London by the earliest possible train for anywhere. Go where you like, write what you like, but send along your stuff as soon as you write it. We shall call the series 'The Diary of an Irresponsible Wanderer.' Enclosed find two hundred pounds to cover all expenses. If you want more, wire. Good luck!"

The assistant nodded his head. "He'll understand that all right," he said grimly.

The chief stuffed four crinkling bank-notes into the envelope and licked down the flap.

Then came a knock at the door, and a boy entered with a scrap of paper. The editor glanced at it carelessly. "Writes a vile hand," he said, and read: "'Business—re engagement.' Will you see him, Jenkins?"

His second shook his head. "I can't see anybody till seven," he said.

The editor fingered the paper. "Tell him—oh, send him up!"—impatiently.

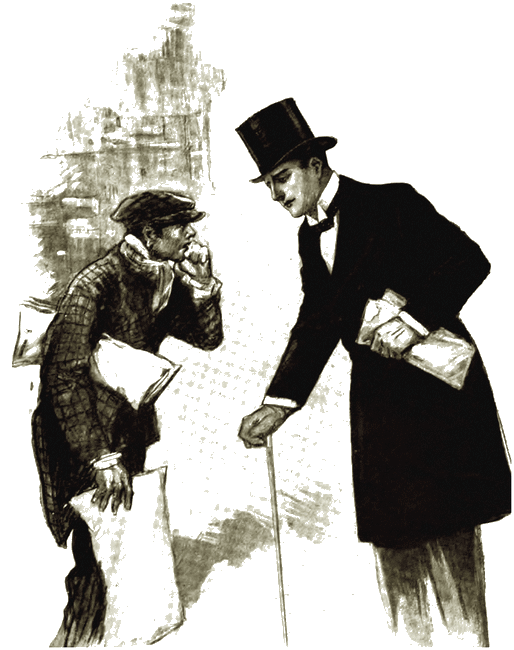

In the waiting-room below was a young man. He sat on the edge of the plain deal table and whistled a music-hall tune cheerfully, though he had no particular reason for feeling cheerful having spent the two previous nights on the Thames Embankment. But he was blessed with a rare fund of optimism. Optimism had brought him to London from the little newspaper of which he was part-proprietor, chief reporter, editor, and advertisement canvasser. His part-proprietorship was only a small part; he disposed of it for his railway fare and a suit of clothing. His optimism, plus a Rowton House, had sustained him in a two months' search for work and a weary circulation of newspaper offices which did not seem to be in any urgent need of an editor and part-proprietor. More than this, optimism had justified his going without breakfast on this particular morning that he might acquire a clean collar for the last and most tremendous of his ventures—the storming of The Megaphone editorial. He had tossed up whether it should be The Times or The Megaphone and The Megaphone had won. He had a sense of humour, this young man with the strong, clean-shaven face and the serene eyes. He was whistling when the small boy beckoned him.

"Editor'll see you," said the youth.

"That's something, anyway, Mike."

"My name's not Mike," said the youth reprovingly. "Then you be jolly careful," said the aspirant for editorial honours as he stepped into the lift, "or it will be."

The chief glanced at his visitor, noted the shining glory of the new collar and the antiquity of the shirt beneath, also some fraying about the cuff, and a hungry look that all the optimism in the world could not disguise in the face of a healthy young man who had not broken his fast.

"Sit down, won't you?" he said. "Well?"

"Well," said the young man, drawing a long breath, "I want a job."

This was not exactly what he had intended saying, though in substance it did not differ materially. The chief shook his head with a smile and reached for a fat memorandum-book.

"Here," he said, running the edge of the pages through his fingers, "is a list of three hundred men who want jobs; you will be number three hundred and one."

"Work backwards and get a good man," said, the applicant easily. "There are not many men like me going." He saw the chief smile kindly.

"I'm like one of those famous authors' first manuscripts you read about, going the rounds of the publishing offices and nobody realising what a treasure he's rejecting till it's snapped up by a keen business, man. Snap me up."

The chief's smile broadened. "You've certainly got a point of view," he said. "What can you do?"

The young man reached for the cigarette that the other offered. "Edit," he said, knocking the end of the cigarette on the desk "partly propriate, report, take a note of a parish council, or write a leader."

"We aren't wanting an editor just now," said the chief carefully, "not even a sub-editor, but—" He had taken a sudden liking for the brazen youth. "Look here, Mr.—I forget your name—come along and see me at eleven to-night. I shall have more time to talk then."

The other rose, his heart beating rapidly, for he detected hope in this promise of an interview.

"I shall be able to give you a little work," said the chief, and walked to the safe at the far end of the office, unlocked it, and took from the till a sovereign. "This is on account of work you might do for us. You can give me a receipt for it." He laid the coin on the edge of his desk. "I've an idea that you'll find it useful."

"I'm jolly certain I shall," breathed the young man as he scrawled the IOU.

He went down the stairs two at a time. He was a leader writer at the second landing, managing editor by the time he reached the ground floor, and had a substantial interest in the paper before the swing doors of the big building had ceased to oscillate behind him. He was immensely optimistic.

He engaged a room in the Blackfriars Road, paying a week's rent in advance, and breakfasted, lunched and dined in one grand, comprehensive meal.

The greater part of the evening he spent walking up and down the Embankment, watching the lights, that had a cheerier aspect than ever they had possessed before. Some of his dreams were coming true. He had never doubted for a moment but that they would; it had been only a question of time.

Eleven o'clock was striking when he stepped into the lobby of Megaphone House. There was a new boy on duty, and, in default of a card, the visitor wrote his name on a slip of paper.

"Who is it you wish to see, sir?" asked the boy.

"The editor."

The boy looked at the slip.

"The editor has been gone half an hour," he said, and the young man's heart sank momentarily.

"Perhaps he left a message?" he suggested.

"I'll see, sir."

Anyway, he thought, as he paced the narrow vestibule, to-morrow is also a day. Perhaps the chief had forgotten him in the stress of his work, or had been called away. Cabinet Ministers, it was reported, sent for the editor of The Megaphone when they were undecided as to what they should do for the country's good.

There was a clatter of feet on the marble stairs, and a man came hurrying down, holding his slip of paper in his hand.

"I'm sorry, sir," he began breathlessly, "but the editor has asked me to say that he has been summoned home unexpectedly. I should have come to meet you, but I have only recently been appointed night secretary, and I have not had the pleasure of meeting you"—he smiled apologetically—"so I should not have recognised you." He handed an envelope to the young man. "The editor said I was to place this in your hands, and that you'll find all instructions within."

"Thank you!" said the youth, breathing a sigh of relief. It was pleasant to know he had not been overlooked. He had left the building, when the secretary came running after him.

"I didn't make a mistake in your name, did I?" he asked a little anxiously.

"Carfew," said the youth—" Felix Carfew is my name."

"Thank you, sir, that is right," responded the secretary, and turned back.

MR. FELIX CARFEW—not to be confused with the great Gregory Carfew, special correspondent to The Megaphone—made his way to a little restaurant opposite the Houses of Parliament with his precious package at the very bottom of the inner-most pocket of his aged jacket. (Gregory Carfew had light-heartedly missed the boat connection at Ostend, and at the moment was playing baccarat in the guarded rooms of the Circle Privée.)

"Now," said Felix, having ordered coffee, "let me see what my job of work is to be."

He opened the envelope and, making involuntary little noises of astonishment, took out four pieces of white paper, whereon the admirable Mr. Nairne promised to pay fifty pounds to bearer; then he opened the letter and read it. He read it three times slowly before he grasped its meaning.

"'Go anywhere!... Write about anything!...'" he repeated, and drew a long breath. "'Earliest possible train!'... You maybe certain of that, O heavenly editor!" he said, and paid his bill without touching the coffee he had ordered.

Earliest train—earliest train!

Now, where did the next train leave for—the next train that would carry him out of London, away from the possibilities of recall, supposing that this too-generous light of the newest and best journalism repented his hasty munificence?

He whistled a taxi-cab, and made up his mind before the car stopped at the kerb. "Victoria," he said. At any rate, Victoria was near, and if there was no train, he could go on to Euston and catch the northern mail. It was half-past eleven as he drove into the station-yard, and he had an uncomfortable feeling that it was very unlikely that there would be a train for the Continent at that hour. (He had unconsciously decided on Paris as his objective.)

"I want a train for the Continent," he told a porter.

"What sort of train, sir?"

"Any sort you've got?" said Felix generously.

"I mean, are you one of the gentlemen who are going by the special?"

"Yes," said Felix, not knowing exactly what the special was, or who were the gentlemen going thereby.

"Well, you'll have to hurry," said the man, galvanised of a sudden out of his normal restfulness. "Come this way, sir."

Since the porter ran, Felix thought it no shame to follow his example, and they came to an ill-lit bay platform just as a whistle shrilled and a very short train began to move.

"Special, Bill!" shouted the porter, and the guard beckoned him furiously.

There was an empty carriage next to the guard's van, and into this Felix leapt. He turned to throw a shilling in the direction of the porter, and then sank back on to the soft cushions of the carriage and wiped his perspiring forehead.

It was a corridor carriage, and he had recovered some of his lost breath when he heard the snap of the guard's key, and the official came through the bulkhead door into the corridor without. The man nodded civilly.

"Nearly lost it, sir," he said. "Have you got a ticket, or are all the tickets on one voucher?"

"Eh?" said Felix, and then began to realise dimly that there was some sort of explanation due to the guard.

"The fact is, guard," he explained, "I am going to the Continent."

Into the guard's face came an expression of distrust.

"Are you one of the party or not, sir?" he asked briefly.

"I am, and I'm not," said the cautious Felix. He felt in his pocket and took out the envelope with the notes. These he extracted and smoothed deliberately on his knee. He felt that this was a moment of crisis. He had evidently boarded somebody's special train, and it was up to him to demonstrate his respectability. A cynic might have been vastly amused at the tender solicitude which suddenly crept into the guard's tone.

"I am afraid, sir," he said gently, "you have got aboard the wrong train. This is a special ordered by his Excellency the Ambassador of Mid-Europe."

"Tut, tut!" said Felix, apparently annoyed. "What am I to do?"

The guard, pondered, tapping his teeth softly with his key. "You keep quiet, sir," he said, after a while; "I'll fix it up for you. There are no passengers on this bogie, and nobody need have any idea that you're aboard."

With these words of cheer, a touch of the cap and a smile, the guard went forward to attend to the official passengers, and Felix stretched his legs to the opposite seat and reviewed the situation. The first part of his instructions was carried out. He had left London by the earliest possible train. At any rate, he could get as far as Dover. Would his Excellency the Ambassador of Mid-Europe have chartered a special boat to enable him to cross the Channel? Anyway, one could cross by the first boat in the morning. And then for Paris! What should he write about? A visit to the Morgue, full of grisly details in restrained but vivid language? That had been done. On a night in the Montmartre as seen by the eyes of one who had absorbed six absinthes? He had a notion that had been done too.

Perhaps he might hap upon some big, exclusive "story"—his luck was in. The Opera House, crowded with the beauty and wit of Paris, might collapse, and he be the only journalist present. That was unlikely in a city where one man in every three owned a newspaper, and the other two wrote for it.

A brilliant thought struck him. An interview with the Ambassador of Mid-Europe!

Everybody was interested in Mid-Europe and its erratic Empress. She had recently delivered an impassioned and bellicose speech, obviously directed towards Great Britain, and diplomatic relationships, in consequence, had been somewhat strained.

Felix Carfew's eyes sparkled at the thought. If he could secure the interview, his fortune would be made, the faith of this trustful editor of his fully justified. How pleasantly surprised The Megaphone would be to receive, say, a thousand words from Paris, beginning:

"I have been accorded an interview with H.E. Count Greishen, who gave me his views on the recent utterances of the Empress."

The tremendous possibility of the thing gripped him, and he jumped to his feet. The train was roaring and swaying through the sleeping country. Rain had begun to fall, and the carriage window was streaked with flying drops.

As the idea took shape he did not hesitate. He was on the train; he could not be thrown off, because this was evidently a non-stop run.

He was out of the compartment and in the corridor before he remembered that the guard had gone to the fore part of the train, and would be coming back in all probability. Reluctantly he returned to his seat and waited. He had to wait a quarter of an hour before the official returned, and for another five minutes he chafed inwardly whilst the guard made polite conversation, which was mostly about people who caught the wrong train and found themselves stranded in little, out-of-the-way stations.

At last the man in uniform turned to go; then it was that Felix remembered that he was under an obligation.

"Oh, by the way, guard," he said, "can you change a fifty pound note?"

The man favoured him with a melancholy smile.

"I couldn't change a fifty-penny note, sir," he said; "but"—brightening up—"I could get it changed for you."

Felix handed over the note. "What time are we due at Dover?" he asked.

"One o'clock, sir," said the man.

"Then hurry up with the change." Felix was growing impatient; he had little more than half an hour to carry out his plan. He wondered exactly how the guard would get change, and his curiosity on this subject was satisfied when, in a few minutes, the man returned with a handful of gold and small notes.

"I suppose you wonder how I got that?" he said, as he counted out the money. "The steward of the Embassy is on board, and, leaving hurriedly, of course he had no time to change his small money."

He rambled on in this strain for a few minutes, but Felix was not listening toward the end.

"Leaving hurriedly!"

When ambassadors "leave hurriedly," taking with them their whole staff—leaving so hurriedly, indeed, that special trains must be ordered—it has a significance. He tipped the guard a sovereign, and sat down with his head in his hands to think.

There was a time-table on the rack over his head, and this he took down. Turning the leaves, he discovered that the last ordinary train for the Continent left London at nine o'clock. What was the urgency of the case that compelled a special at eleven-thirty!

"Felix, my boy, you've found news!"

He had made up his mind before the train ran alongside the ocean quay. It was a mild, wet night, he had no overcoat, but this did not worry him. He stood back in the shadow of the train and watched the Ambassador's party descend. There were fourteen in all, and they made their way along the quay to where lay one of the smaller channel steamers.

"Chartered," said Felix to himself.

He took the landward side of the train and stepped out quickly. Half-way along the deserted platform he came upon a solitary seaman-porter. With a recollection of a previous calling, he asked: "Can you get me an oilskin?"

The man hesitated. "I've only got my own, sir," he said.

"I'll give you a sovereign for it," said Felix.

"It's yours," said the other promptly, and stripped it off.

"I've got a sou'wester kicking about somewhere," said the porter, pocketing the coin. "You'll want it if you're crossing. Wait here, sir."

Felix waited for a moment, when the man came running back, the hat in his hand. "Here you are, sir! Hurry up if you're going by the special!"

"I'm going by the special all right," replied the confident youth. "Would you like to earn a sovereign?" he asked suddenly.

In the darkness he could not see the man smile at the absurdity of the question.

"I should say so," he said.

"Come along to where there's some light." Under a flickering arc lamp Felix wrote a brief message on the back of his blessed envelope.

"Get through to London on the telephone," he said. "You'll be able to do it, if you persevere—and send this message."

"I can do it from the post-office, or from one of the hotels if I tip the night-porter," said the man.

"Well, tip him; here's another half-sovereign."

The steamer at the quayside hooted warningly, and Felix thrust the money and the message into the porter's hand. "You'll have to dig out the telephone number," he called back, as he hastened his steps to the ship. None challenged him as he ran down the slippery gangway to the heaving deck of the steamer. The Ambassador's party had disappeared below, and a sailor directed him to the saloon.

"Thanks, I'll stay on deck," said Felix. He waited until the pier light slipped astern, then made his way below. Along the main deck, on either side ran an alleyway, and a door abaft the engines opened to a flight of stairs leading to the saloon of the steamer. Very cautiously he stepped inside. From where he stood he had a capital view of the saloon. A long table had been laid for a meal, and round this the various members of the Embassy were grouped. Felix recognised the old Count, with his fierce, white moustache and his shaggy eyebrows, sitting at the head of the table. They were talking in a language Felix did not understand, but he used his eyes with some effect, and by and by he saw the Ambassador take from his pocket a leather case, open it, extract what was evidently a long telegram, and compare it with a sheet of paper which had been folded with the wire.

"Those are his instructions," said Felix; "they are in code, and that paper is the translation. I'm going to have those if I die in the attempt!"

The danger would be, he told himself, that the boat would arrive at Calais before he had time to put his plan into execution; the party might sit at their meal until the harbour was reached. He prayed fervently for a choppy sea or a gale of wind that would send them flying from the saloon; but the sea was like oil, and the drizzle of rain was a sure indication that no wind could be expected. He went up to the top deck to think out a scheme. Over to starboard a bright light flashed on the horizon at regular intervals.

"What light is that? "he asked a passing deck-hand.

"Calais, sir."

"Calais! Oh, of course, we leave Calais on the right?" He put the question carelessly.

"Yes, sir, for Ostend."

"Oh!" said Felix, who had secured the information he wished. For an hour he paced the deck enjoying the novelty of the position. Then there was a stir at the companion-way, and half a dozen men came up, heavily coated, and made their way to a covered shelter behind the funnel. The Ambassador was not one of these, and the adventurer moved forward to investigate. He went below again. There were a number of cabins opening out on to the main deck, and he had time to see the broad back of Count Greishen disappearing into one of these.

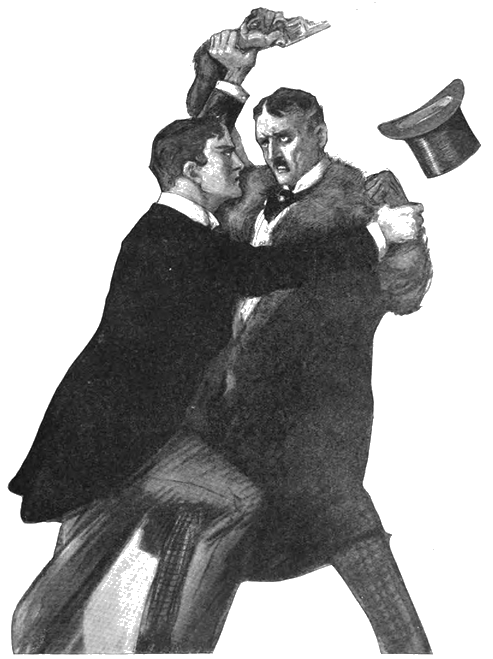

"YOU'LL excuse me," said Felix, switching on the light, "but I want to get your views on the European situation." It was the sort of thing he would say if he had been interviewing the member for East Poshton, and the respectful tone was all that could be desired.

An elderly diplomatist, awakened at two o'clock in the morning by an imperturbable youth in oil-skins and sou'wester, might be excused a feeling of irritation; but when the awakening is performed by the sudden switching on of an electric lamp, and the first greeting he receives is a request for his views on the political situation, his wrath, however great, may be pardoned.

He was speechless for a moment, the while Felix produced a conventional notebook and seated himself on a settee.

"In cases like this—" he began, when the Count found his voice.

"Who are you, sir, and what do you mean by coming here? I'll have you arrested, you—you—"

Felix raised a warning hand.

"Do not let us forget that we are gentlemen," he said, with dignity. "Now, on the question of diplomatic relationships, don't you consider that your people are behaving like goops? Now, take the question of that silly speech of the Empress—"

"Sir," said the diplomat, with terrible calm—he was sitting up in his bunk, and the fact that he wore green-striped pyjamas detracted somewhat from his impressiveness—"you are going too far. I gather that you are a journalist?"

"Carfew, of The Megaphone," said the young man proudly.

"Mr. Carfew—I shall remember your name," said the Ambassador. "You have forced your way by some means on to a boat which has been privately chartered. Now you force a way into my cabin, and I shall have you removed. In all my life I have never—"

"I dare say you're right," interrupted the youth graciously; "but that's beside the point. What we have to arrive at now is a modus vivendi. A similar situation occurred in Pillborough, where the mayor had a terrific row with the borough surveyor, and wouldn't sit in the same room. You needn't try to ring the bell, because I've cut the wire outside. Now, your Excellency, let us talk this matter over. You've had instructions to return immediately?"

"This," said the Ambassador, trembling with anger, "is an outrage against every civilised law!"

"Let me ask you a few questions." Felix poised his pencil. "You have been recalled—yes?"

"Let me ask you a few questions."

"I refuse to answer."

"As a result of the recent speech of our Prime Minister—"

"Your Foreign—Confound you, sir, I won't answer your beastly questions!" roared his Excellency.

"Very good," said Felix writing rapidly. "'As a result of the speech of the Foreign Secretary, my Government recalled me. The instructions did not reach me until after nine—'"

"How do you know that?" demanded the astonished diplomat.

"We have sources of information undreamt of," replied the young man gravely.

For the greater part of an hour they sat—the persecuted and the persecutor—until the slowing of the engines warned the reporter that the end of the journey was at hand.

ANOTHER man had been aroused in the middle of the night, to his intense annoyance. This was Gregory Carfew, to whom, at 3 a.m., came an urgent telegram:

YOUR TELEGRAM RECEIVED: HAVE CONFIRMED FACTS. WE SEND YOU THIS TO HOTEL IN THE HOPE YOU WILL CALL IN FOR WIRES. LET US KNOW IF YOU WERE ABLE TO GET ABOARD SEABIRD.

Now, Carfew was really a great correspondent, and, albeit, bewildered by the character of the message, he scented a story, and lost no time in dressing. The Seabird he had never heard of, but in the dark hours of the morning he found a marine superintendent who afforded him some important information.

"Seabird, m'sieur? Yes, it is one of the smaller of the packets. It is strange that you should ask, for we have just received a wireless message from her; she is seven kilometres outside. She has asked for police to be present to arrest a suspicious character who is hiding aboard."

"'Curiouser and curiouser,'" quoth Carfew, settling himself down on the wooden quay to await the arrival of this mysterious steamer.

After a while, six Belgian policemen came and took up a position on the jetty. Then, in the grey light of dawn, the little paddle-boat came stealing into the harbour and made its stealthy way to the pier. The policemen were the first aboard, and Carfew followed.

Since the interest would seem to centre round the police and their presence, he followed them at a leisurely pace and came upon a group. An elderly man, speaking volubly in French, was talking, and instantly Carfew recognised him.

"By Jove," he ejaculated, "it's old Greishen!" and elbowed his way through the little crowd."

"I do not think I should recognise him," the Ambassador was saying. "He kept his hat on all the time, and when the engines stopped he fled.... But he is on board the ship somewhere."

"Pardon me, your Excellency"—Carfew pushed his way forward—"can I be of any assistance? My name is Carfew, and I am on the staff of The Megaphone."

"That's the man!" roared the Ambassador, and rude hands seized the astonished correspondent.

"You have made a mistake, my friend," said the Count, his English failing him in his excitement. "You carry this off with a bloff, but I will put you where your mischievous pen will rest for a day or two. Listen, my friend!" He wagged a fat forefinger in the face of the paralysed Carfew. "If you had published what you had discovered last night, what you stole from me—yes, I have detected the loss of my despatch—if you had published, you might have made serious embarrassment for my country; but when you publish all the world will know. Two days, three days, you will go to prison, and then we can afford to release you. Marchez."

Carfew One was swearing terribly as he was hustled across the gangway, what time, snugly hidden in one of the boats that swung not two yards from where the arrest had been made, Carfew Two was busily making notes for the story which was to establish his fame in the London newspaper world.

CARFEW could never quite make up his mind whether he would like to be a millionaire, or whether he would prefer to jog along with five or six thousand a year. He lived in Bedford Park, and occupied the period of time it took him to walk from his lodgings to Turnham Green Station in setting his affairs in order. Thus, he would never make a will. It is much better to be magnificent living than munificent dead. The newspapers would record both qualities, giving as much space to either, with the added advantage that the living philanthropist could read all about it in the morning newspapers.

His favourite distribution of wealth was as follows:

Foundation of scholarships (the Carfew Foundation for the Children of Journalists), fifty thousand pounds.

Endowment of a children's hospital, two hundred thousand pounds. (A baronetage would probably follow, though Carfew was democratic, not to say socialistic.)

The establishment of an ideal newspaper, and the maintenance of same without advertisement revenue, one hundred and fifty thousand pounds. (Carfew had had bitter experience with advertisers, who blankly refused to "come in" to the little sheet of which he had been part-proprietor, and he had rehearsed some exceedingly nasty things he would say to would-be advertisers. "No, sir, we cannot print your advertisement. I don't care if you offered me twenty pounds an inch—I would not insert an announcement concerning your infernal soap!")

Motor-cars handsomely furnished, lit with electric light and replete with down cushions, say, ten thousand pounds.

Mansion in a lovely park, where he would live, alone, one hundred thousand pounds. ("Who is that sad-faced young man?" strangers would ask the inhabitants of the village. "Him? Why, don't you know?" the rustics would reply, in hushed but respectful tones. "Yon's Squire Carfew, the millionaire. They du say that he be a turruble man to cross in anger.")

Such possessions demanded the application of the millionaire's schedule, and were infrequent. In the main, Carfew was content with five thousand a year and a life of travel. One morning in April Carfew was busy endowing a hospital or an orphan home. He had reached the point where His Royal Highness had declared the building open.

Carfew was kneeling on a red velvet cushion, and the Prince's sword was raised for the accolade, and Carfew had stopped in his walk that he might enjoy the emotion of the moment, when he came into collision with an elderly gentleman, who, after carefully closing the gate of his suburban villa behind him, had bumped into the stationary figure standing wrapped in thought on the side walk.

He was a very fierce old gentleman, somewhat spare of build, grey-haired and grey-moustached, and he had the ruddy-pink complexion of one who had served his country faithfully and had written to the papers about it.

"Your Royal Highness," began Carfew genially, "I regret—"

"Why on earth don't you look where you're going?" asked the elderly gentleman.

"I usually do," said Carfew, "but apparently the accident was caused by my not looking where I was coming from."

"You are an impertinent puppy!" fumed the other. "By Jove, sir—"

He flourished his silver-knobbed walking-cane suggestively.

Carfew evaded the waving cane, then took a leisurely survey of the street.

"If you are endeavouring to attract the attention of a wandering motor-bus," he said, "it is my duty to tell you that you are off the line of route."

The bristling gentleman shrugged his shoulders elaborately. "Puppy!" he repeated, and walked on, giving vicious little tugs to his frock-coat and patting himself here and there. A gladiator strutting from the gory floor of the Colosseum might so have arranged his disordered dress.

Carfew followed at a respectful distance, his heart filled with mild resentment.

He did not object to the hasty appellation—he strongly resented the interruption to the interesting ceremony of which he was the central figure. Carfew at the moment was out of elbows with fortune. He had been fired from the staff of The Megaphone—that great organ of public opinion. He had fallen with what the provincial reporter loves to describe as a "dull, sickening thud."

This happened two months before Carfew collided with the military gentleman in Bedford Park. Three months' salary paid regularly lasts three months. Three months' salary paid in advance lasts exactly six weeks. I do not explain this economic phenomenon—I merely state it as a fact. And here was Carfew counting the change from a shilling at the Turnham Green booking-office. And here was Carfew, who became severely practical in a train, debating in his mind whether he should tell his landlady exactly how he stood financially, or whether he could bluff it out another week.

When he had left The Megaphone he was not decided in his mind whether he would start a rival newspaper, or whether he would take employment with a rival journal. He had, with a pencil and paper, worked out a scheme whereby he could produce a paper which would show a profit of two thousand pounds a month, but convinced nobody but himself. He was no more fortunate when he decided to offer his services to other journals.

There was a conspiracy designed to keep him unemployed. Nobody wanted him. The editors in Fleet Street gave him audience readily enough, were immensely polite, but unsatisfactory. They felt that, in the present state of journalistic depression, they could not offer him the salary which his services deserved. Every single newspaper, daily or weekly, to which he applied, informed him that his visit coincided with a period of rigid economy.

It may have been that the modest estimate he made of his own value was not sufficiently modest. Be that as it may, Carfew, on this memorable spring morning, was "up against it, good and hard." He alighted at Temple Station, and turned on to the Embankment. It was a glorious spring day. The world was aflood with April's yellow sunlight. The trees were bursting into green, and through the railings of the Temple he saw great splashes of vivid colouring where the tulips bloomed in beds of stiff and orderly formation.

Carfew squared his shoulders and stepped out briskly, for he was young and buoyant and had faith in Carfew. And the world was bright and beautiful and sunlight fretted the waters of full Old Thames with criss-cross patterns of gold, and there was a fat, black tug pulling a string of lazy barges against the stream.

Carfew decided to cross the broad thoroughfare to get a better view of the river. There was a man walking in front of him—an elderly gentleman, with a jaunty silk hat and a frock-coat cut tightly in at the waist. The back view was familiar. Half way across the broad thoroughfare, Carfew suddenly reached out his hand, grasped his elder by the shoulder, and unceremoniously dragged him back.

The fact that half an hour previously he had called the other a puppy did not seem to Colonel Withington sufficient justification for the assault.

"Sir!" he gasped awfully.

A motor-car whizzed past within a few inches of where they stood. The chauffeur flung a sinful observation in passing about people who did not look where they were going.

"I have saved your life," said Carfew modestly, "but do not, I beg of you, thank me. I am sufficiently repaid by the driver's offensive remark."

He released the Colonel, and they crossed the remainder of the road together.

"I am awfully obliged," growled the elderly gentleman. "I didn't hear what the man said."

He added his opinion of the man with true soldierly frankness.

"He told you to look where you were going," said Carfew sweetly.

"Humph!" said the Colonel. They reached the side-walk in safety. Carfew, with a courteous little bow—one he had invented specially for the occasion of his presentation to Royalty—turned to the parapet. The Colonel hesitated, walked on a little way, stopped and looked round at the unconscious youth, drinking in the beauties of the river, then, after a moment's hesitation, walked back to him.

"Excuse me," he said, and tapped his shoulder lightly with his cane.

Carfew turned.

"Can you spare the time to walk a little way with me?" said the Colonel gruffly. He was a trifle stiff, being an uncompromising, explosive colonel, not given to graciousness. In his lifetime he had sentenced many guilty soldiers to cells, had presided at courts-martial, and had spent many hours of his life shouting incomprehensibly at eight hundred men, and the eight hundred men had done exactly what he shouted without so much as saying: "Excuse us, sir, but haven't you made a slight error?"

Carfew fell in by the other's side.

"My name is Withington, Colonel retired," said the Colonel briefly. "I am greatly obliged to, you. I am afraid I was rather rude to you—apologise."

"Certainly," said Carfew; "I apologise, though why I should apologise for your—"

"Huff!" said the Colonel. "You misunderstand—I apologise. What's yours?"

"Thank you," said Carfew; "but, if you don't mind, I'd rather have a cup of tea. Any kind of drink—"

"What's your name? What's your name?" demanded the military gentleman, testily. "I'm not inviting you to drink. You don't suppose, my good fellow, that I'd walk into a public-house, eh? What on earth do you think I am—eh?"

Carfew did not tell him; instead, he offered vital information. "I am Carfew," he said. That was all. He was Carfew. Everybody knew Carfew. It had appeared. in the papers—it had been printed.

"Don't know you," said the Colonel, "but I'm awfully obliged to you. What d'ye do?"

Carfew was annoyed.

"I am Carfew," he said distinctly—"Carfew the journalist—the Carfew."

The Colonel looked at him suspiciously.

"Reporter, eh?" He wagged a warning finger. "Don't put anything in your beastly paper about me: 'Famous Inventor's Narrow Escape: Rescued from Death on the Thames Embankment! ' None of that! I know you!"

Carfew was speechless. If there was one thing in the world he hated more than another, it was being called a reporter. He felt as the Colonel might have felt had he received a letter addressed "Lance-Corporal Withington."

And the arrogance of the old man! He thought himself famous! And he did not know him!

"You need not trouble," he said brutally; "you're worth about three lines, including your biography. You are what we call a 'fill.'"

They walked on in wrathful silence, crossing Queen Victoria Street by the subway.

"I don't dislike you," said the Colonel suddenly, as they emerged from the underground passage. "Are you free?"

"As the air," said Carfew, mastering his annoyance.

"Then come along—come along," said the Colonel. They walked on in silence for a while, the soldier twirling his cane and humming a mutilated fragment of a song which was popular enough in the 'sixties, and the words of which, as far as Carfew could gather, were:

Ta looral um, looral um, oh,

Ta diddy, la diddy, hi hay,

Oh, dee dum ti tiddle,

Oh, loorum lum liddle,

Oh, tumpty, would any one say!

"Three lines, eh?" said the Colonel suddenly—"three lines? Ah, you're a child—you do not know!"

He went on with his song, the second verse of which did not differ materially from the first. Now and again he shot a swift glance at the lean-faced youth at his side. What he saw satisfied him, for of a sudden he remarked explosively:

"I'll make your fortune! Hang it, I'll make a millionaire of you!"

Carfew was impressed. A dream had been realised. Somewhere in the background of his life there had ever lurked a munificent old gentleman who would adopt him.

"I have no parents," he said encouragingly, "and no relations whom I know. I have always felt the need of such a father as you would make, Major—"

"Colonel!" snapped the other. "And don't talk to me about my being your father! I'm not old enough, sir, to be the father of a big gawk like you. I don't suppose there is twenty years between us."

He glared challengingly at Carfew.

"How old are you?"

"Twenty-four," said Carfew.

"Hum!" said the Colonel. "I'm over forty—just a little over forty."

Carfew was sufficiently discreet to stop himself saying that he looked older.

"Here we are." They turned into a block of offices facing the Salvation Army Headquarters. In the vestibule the Colonel grasped his arm and pointed with his cane to the white-enamelled indicator.

"Colonel G. Withington, Inventor," he read. "The Withington Compass Company, The Withington Dry Plate Syndicate, The Withington Gun Recoil Company, The Withington Patents. Fourth floor."

Carfew read all this, and the Colonel was gratified to note that at every enterprise his young companion nodded his head approvingly. The liftman, who was also the hall-porter, saluted the inventor punctiliously.

"Man of my old regiment," introduced the Colonel, with a jerk of his head. "Eh, Miles? Got you this job. Out of work and starving—three children—foolishly improvident!"

"Yes, sir," said Miles, who had long since ceased to be embarrassed by the crude recital of his misfortunes. "Left the regiment sixteen years ago. You were Major—"

"That will do, Miles," said the Colonel loudly. The lift rose slowly to the fourth floor and they stepped out. Immediately facing was a door on which was painted the Colonel's name and the title of his companies.

The tenant unlocked the door with a flourish—he did everything with a flourish—and waved Carfew inside.

"No clerks," said the Colonel. "No spying, prying, lying—er—""

"Trying," suggested Carfew."

"No, sir—no clerks. Here's my little home—my little gas stove—I make my own tea—my desk, my drawing-table, my modest library. Take a chair."

He opened a cupboard, and took down a soiled velvet coat and a faded smoking-cap, such as you see in the earlier Du Maurier drawings.

"Work, work, work!" said the Colonel. He opened a drawer of his desk and took out a flat tin of tobacco and a large pipe, and, whilst he filled it, Carfew recovered from his disappointment.

For this was no millionaire's sanctum. It was a poverty-stricken little office. There was a file of newspapers, an antiquated filing cabinet, a bureau, which combined the useful functions of desk and bookcase, two chairs, the gas-stove, and a few almanacks.

"I like you," repeated the Colonel. "You are the type of man I have been looking for—pushful, resourceful, thick-skinned—a bluffer."

Carfew looked thoughtful.

"I'm an inventor," said the Colonel. "Does it pay? No, sir. When I am dead, some rotter will be rolling in luxury, sir, on the fruits of my genius. This time fifty years—millions; to-day—that."

He banged down on the desk a handful of money, hastily drawn from his pocket. Carfew noted with dismay that it was in the main made up of coppers.

But his dismay turned as quickly to laughter—good-natured laughter—and the Colonel's grim face relaxed.

"We're in the same boat, sir," said Carfew, and chuckled at the humour of it.

The Colonel's uplifted hand stopped him. "But we are at the end of our penury," he said. "Read this!" He pushed a letter towards the young man. It was headed "Swelliger and Friedman," and read:

DEAR SIR,—

We have to thank you for your favour of even date. We have gone into the question of your patents, and we are willing to acquire two—namely, the Withington Compass and the Withington Gun Recoil Patent. We offer you the sum of three hundred and fifty pounds for these, though, in doing so, we feel it is our duty to tell you that we regard neither as being of such commercial value as will recoup us for our speculation.—

We are, etc.

Carfew read the letter again. Here was a firm of financiers offering three hundred and fifty pounds for something they expected to lose money over.

"We'll go into this," said Carfew with energy. He spent a busy morning examining curious and boring specifications. He found the Colonel a most extraordinary mixture of shrewd worldliness and childlike innocence. At eleven o'clock Carfew was a partner in the most promising business in London. At twelve he had been summarily reduced to the ranks, deprived of his living, the partnership dissolved, and degraded to the honorary position of ignorant jackass. (This was the direct result of his questioning the value of the patent compass; the Colonel was a little annoyed.)

At one o'clock they went out arm in arm to an A B C shop, Carfew being at the moment managing director with authority to act.

He had many vicissitudes that day; for the Colonel, who, as he proudly confessed, had neither chick, child, wife, nor any other master but the King, God bless him!—"Amen," said Carfew piously—was unused to being dominated. Carfew had a method of his own, He had energy; he had that supreme contempt for the world which every proper journalist possesses; he had business knowledge and a commercial diplomacy—which only comes to the country reporter who has learnt that an advertisement must be balanced with a flattering editorial notice of the advertiser. He had, in fact, all the qualities that the Colonel lacked,

For three days Carfew worked at top speed, reading specifications, strenuously grappling with drawings which he but imperfectly understood—the Colonel had been an R.E.—sorting out the correspondence which had been neglected. He found that there were all sorts of little sums due to the inventor—little royalties, too small for the magnificent seeker of millions to notice. These he claimed peremptorily. In the meantime came an urgent letter from Swelliger and Friedman, begging the favour of an immediate reply to their letter.

But Carfew had gone into the question of the patent compass and the patent recoil. The compass he understood, the recoil carried him into a dark desert of dynamics, through which he vainly groped a way.

"Let 'em have it—let 'em have it," said the Colonel impatiently. "They are thieves! The compass is worth a million of anybody's money, but let 'em have it."

"What is the recoil worth?" asked Carfew.

"Millions," said the Colonel impartially, "but no commercial value, my dear boy. Limited output, limited income. I worked it out to amuse myself."

Carfew knew a man who was manager to a firm of scientific instrument makers, and to him he went. Briefly he explained the compass and exposed a model.

"Now, I am not trying to sell this to you," he said, "and I want you to forget you're in an office, and try to think you're in a church. What is the value of this invention?"

The man looked at it and laughed. "I've seen it before," he said; "we examined the specification for a client. It is worth nothing."

"Absolutely?"

"Absolutely. There are compasses on the market that do all the funny things that this does, and more."

"Would you be surprised to learn that Swelliger and Friedman want to buy it?"

"I should not only be surprised," said the manager carefully, "but I should be incredulous."

That afternoon Carfew had a letter typed asking the financiers to fix an appointment for "our Mr. Carfew" on the following day at two o'clock. On the morning of that day the adjutant—he accepted the rank and appointment from the Colonel's hands with gratitude—called at the War Office, and sent his name up to His Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for War.

I do not explain how it came about that the interview he sought was immediately granted. There are, you must remember, two Carfews. I would not dare to suggest that the card—inscribed "Mr. Carfew, Daily Megaphone"—had anything to do with the invitation "Will you come with me, sir?" of the liveried messenger.

The War Secretary was tall and thin, and a little severe. He looked over his pince-nez at Carfew, and appeared to be surprised.

"I thought you were Mr. Carfew," he said.

Carfew bowed, and the Secretary of State, who was a tactful man, as one should be who had to deal with a Service jealous of influence, indicated a chair.

"I know the other Mr. Carfew," he said pleasantly. "Now, sir?"

Never a word-spinner, Carfew said all he had to say in five minutes.

"An invention," said the Minister, and shivered slightly. "It sounds valuable. I think I know Colonel Withington." He pressed a bell on his table, scribbled a note on a card, and when the messenger appeared, "Take this gentleman to Major-General Vallance," he said. He offered a mechanical hand to Carfew, favoured him with an almost automatic smile, and, "This officer will attend to you," he said.

Carfew was taken down a long corridor, and after a wait he was ushered in to Major-General Vallance, a little man, very bald, and very unhappy.

"Invention?" He shook his head sadly. "Guns—recoils? Let me see?"

Carfew handed the typewritten sheets, and the officer read them carefully. Then he examined the drawings, and then he re-read the specifications. Then he looked at the drawings again, and checked certain sections with the description. With his head between his hands he read the specification again. When he had finished he said "Ha!" and looked at the ceiling.

He folded the papers carefully, replaced them in their envelope, and handed them back to Carfew. "It is an invention," he said—"a good invention—we have proved it—but of doubtful value to us. It would mean pulling all our Q.F. guns to pieces to introduce it, and that would never do."

"But—" said Carfew, "wouldn't it be better than your present system?"

"If we had guns of another pattern," said the officer carefully, "and we anticipated their employment in circumstances— er—different, so to speak—well, we might consider the matter."

"I see," said Carfew glumly. He saw himself accepting the three hundred and fifty pounds offered by the speculative financiers.

"It would mean pulling our guns all to pieces," mused the General, "and, of course, very careful and detailed experiments before we paid thirty thousand pounds for an invention like that. You would be well advised to accept a lower offer."

Carfew sat bolt upright. "Thirty thousand pounds?" he repeated huskily.

The officer nodded. "That was the sum you mentioned in your letter, I think." He did not observe Carfew's agitation as he pulled out a drawer of his desk and lifted out a little folder. This he laid on the desk before him and opened. He turned over two or three letters before he came to the one he sought.

"Yes," he said, reading, "thirty—oh—er—um!" He hastily folded the portfolio again. "I see. Yes, wrong letter. Confusing you with somebody else."

But the mischief was done. Carfew had seen the magic words "Swelliger and Friedman," and rose to the occasion.

"That's all right, General," he said, getting up from his chair; "the offer was made to you through our agents, Swelliger and Friedman. I thought I'd see you myself. We can always sell the patent, but naturally Colonel Withington wanted you to have the first refusal. Before I left the office this morning the Colonel said: 'Whatever we do, Carfew, we must persuade the British Government to take this. If it's worth sixty thousand pounds to Germany, it is worth thirty thousand pounds to Great Britain!"

"Very proper," murmured the General—"very proper indeed. I wish we could—"

"Fortunately," Carfew went on with quiet dignity, "neither Colonel Withington nor I are in need of money—the question of payment does not come into the matter. We naturally have to protect our shareholders."

"Naturally," agreed the officer cordially.

"If the Government would pay us a couple of thousand pounds to secure the option—" suggested Carfew.

The General hesitated. "It would mean pulling our guns to pieces," mourned the General plaintively; "and—er—I think we have already got the option."

"Wow!" said Carfew, but he said it to himself.

He slipped the envelope into his breast-pocket, lingered a while, received no encouragement to stay, and took his leave.

He and the Colonel lunched frugally, and he told the senior partner all that was necessary for him to know.

"Did you mention the compass?" asked the Colonel anxiously.

This compass of his was very dear to him in every sense, for he had spent a small fortune in protecting it.

"No, I did not," confessed Carfew.

"Then you're an ass!" said the Colonel vigorously. He banged the marble-topped table at which they sat, to the scandal of the habitués of the A B C shop.

"You have failed, sir, in your duty! You undertake a mission entirely on your own initiative; you bluff your way into the presence of the most incompetent minister of modern days, sir; you bluff your way into the office of that old fool, Vallance; you have opportunities, sir, and you fail to avail yourself of them! I should never have gone to the War Office—I have a supreme contempt for it—but had I gone there, sir, I should have played my strongest card—the Withington Luminous Compass. You're a fool!"

Carfew sniffed and suffered.

"You had better consider yourself my clerk," growled the old man—"attend to correspondence, do nothing without orders! You are not fit to be a partner."

"Shall I pay the bill, or will you?" asked Carfew.

"You!" snapped the Colonel. "You know very well I paid for the postage stamps this morning, and there is that infernal milkman to be paid to-day." (It may be mentioned that the partners made their own tea.)

Carfew was junior clerk for nearly half an hour, till a discreet word of praise for the Withington Vacuum Brake, on which the Colonel was engaged, restored him to his managing directorship.

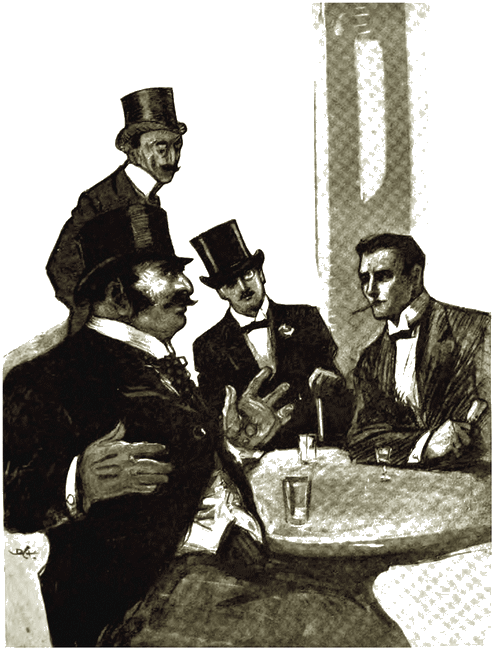

At two o'clock, prompt to the minute, Carfew presented himself at Swelliger and Friedman's portentous offices in Lothbury. He was shown into a waiting-room, and was detained ten minutes, at the end of which time he sent a message to the effect that he was a very busy man, and, if the partners could not keep their appointment, he must forego the pleasure of the interview.

"Could he call back again in half an hour?" asked the messenger.

"In half an hour," said Carfew, putting his hand into his watch-pocket and examining his palm, "I must be at the War Office."

In twenty seconds he was in Mr. Friedman's room. It was a beautiful room, "more like," described Carfew subsequently, "a blooming boudoir than an office."

The carpets were thick, the tables and desk were highly polished; there was a magnificent chimney-piece, and an Old Master above it. Mr. Friedman, however, had not been delivered with the furniture. He was not in the scheme, and harmonised neither with the soft-hued carpet nor the Louis Quinze electrolier.

He was very short and very stout. He had side whiskers and a moustache, and his pockets bulged with hands. He took one out reluctantly and offered a limp greeting.

"Sit down, won't you!" he said, with the aplomb of one who was rich enough to be affable to his superiors. "Now, what's all this about, hey? What's all this about?"

He sat heavily in a gorgeously-upholstered chair, and stuck his short legs forward stiffly.

"You're from Colonel Withington, ain't you? Now, what about this invention—these inventions, I mean to say—of his?"

"We'll sell," said Carfew.

"That's right—that's right," said Mr. Friedman. "It's a speculation for us; but then, as the old sayin' goes: 'If you don't speculate, you don't accumulate, hey?'"

"We'll sell," said Carfew, "at a price."

"Three-fifty, I think," said Mr. Friedman.

"Three-fifty, I don't think," said Carfew.

Mr. Friedman said nothing. He gazed long and earnestly at the young man.

"What d'ye want?" he asked.

"For the compass—" began Carfew.

"Don't separate 'em, my dear lad—don't separate 'em," said Mr. Friedman.

"For the compass," said Carfew, "I will take three hundred and fifty pounds, and for the recoil—"

"Yes?" Here the financier became alert.

"Twenty-five thousand pounds," said Carfew slowly.

Mr. Friedman wriggled in his chair. "Hear him," he said appealingly to an invisible deity—"hear him! Twenty-five—No deal!"

He got up and held out his limp hand.

"Goo'-bye," he said.

"For all rights," said Carfew, ignoring the hand— "American, French, German, Austrian, Italian, Russian and British."

"Goo'-bye," he said. "For the British rights alone you'll get thirty thousand pounds," Carfew went on. "We want a quick deal, or we should sell direct."

"Glad to have met you. Goo'-bye," said Mr. Friedman.

"It will pay you handsomely," said Carfew thoughtfully. "You've been making experiments, and you know that the thing is genuine. The War Office expert has approved, and it's only a question of a thousand or two one way or the other with them."

Mr. Friedman shook his head vigorously.

"Experiments cost us nearly a thousand," he said, "an' you expect—Bah! Well, I'm busy. Goo'-bye."

Carfew shook the extended hand and walked to the door.

"Here," said Mr. Friedman suddenly—"come back! Be a sensible young man. Sit down."

"Come back! Be a sensible young man."

He pulled open a drawer and took out a box.

"Have a good cigar," he said. "You can't buy those in London under five shillings."

"I shan't try," said Carfew, and selected one. He puffed in silence for a few minutes.

"Now, be sensible," begged Mr. Friedman, "and I'll be frank. You said you wanted twenty thousand. I'll tell you what I'll do. I'll give you five thousand, half cash down. Now then?"

"I said twenty-five," corrected Carfew, "and I'll take twenty-five, cash down."

Mr. Friedman was undisguisedly upset.

"Compromise," he said severely, "is the essence of business. Meet me fair, and I'll act fair. I've got all sorts of irons in the fire, and it does not matter to me whether I do a deal or whether I don't. I'll give you ten thousand, an' that's my last word. How's the cigar drawin'?"

"Fine," said Carfew.

"I pay five shillin's each for 'em wholesale. Here, put a few in your pocket. "Now, man to man, is it a go?"

"Twenty-five thousand pounds," said the obdurate Carfew.

"Goo'-bye!" responded Mr. Friedman with such energy that the young man knew that this was the end of the interview. As he opened the door, a clerk came in with two telegrams. Carfew had left the office, and was walking along Lothbury, when the same clerk came running after, him.

"Will you go back to Mr. Friedman?" he asked.

"No," said Carfew, but his heart quaked at his own temerity. He stood irresolutely at the end of Lothbury, watching from the corner of his eye the building he had left. By and by he saw the top-hatted Friedman come hastily forth and walk in his direction. Carfew leisurely signalled a taxi.

"Here," said Friedman—"one word with you, Mr. What's-your-name."

The cab drew up.

"My last word with you," said Friedman solemnly, "is fifteen thousand pounds cash."

Carfew shook his head. "I am sorry, Mr. Friedman," he said. Then to the driver: "The War Office, and afterwards to the German Embassy."

It was a mighty guess, but he felt Mr. Friedman's fat fingers grasping his arm.

"Your price is my price," said the financier. "You're an obstinate young man." He shook his head in reproof and admiration.

Carfew smiled. "Will your clerk pay the cabman?" he asked. "I have no change."

"Certainly, my boy," said Friedman with boisterous good humour; and he himself, from his august pocket, with his own imperial hand, produced a shilling. This saved Carfew some little embarrassment, for the liquid assets of Carfew, Withington & Co. at that moment were eightpence, and the Colonel had sixpence of that to pay the weekly milk bill.

A MAN who attracted money to him by the exercise of one set of qualities, and repelled it by the employment of another set, money in Carfew's hands was inflammable. It went with a flare and the roar of a kerosene refinery after the president's son—new from college, but strange to the business—had dropped his cigarette end in the basement.

Carfew came to the Grand Western Hotel with six thousand golden sovereigns standing to his credit in the L. & S. Bank. He came in a taxi-cab, with a worn portmanteau and a cheque-book, and he spent a glorious week of life tearing out the little pink slips till they were exhausted. After which he got another cheque-book.

In the meantime he had got another portmanteau, a remarkable wardrobe, and the reputation of being an American bank robber.

"For," argued the gorgeous German hall-porter of the Grand Western, "he could not his money with such profusion spend if he had it honestly acquired."

Carfew was indifferent to the opinion of the hall-porter, being in that stage of superiority which allowed him to wear heliotrope socks without shame. People came to see him—people who wanted to render him invaluable services. Some wished to lead him to the private road which cuts off ten miles of the dreary path to fortune; some had ideas that only wanted money.

These latter Carfew laughed to oblivion, for he had ideas of his own—and money.

His money enabled him to indulge his taste in his own particular ideas, which ran in the direction of the Burlington Arcade, and took expression in artistic cravats and socks that spoke for themselves. It is a grand thing to be rich—to be able to write "Pay bearer five thousand pounds," without running the risk of being arrested.

His vices were inexpensive. He did not drink. He was no epicure, he loved fresh air and taxi-cabs. Theatres could not cost him more than three guineas a week, for of all the vices to which men are victims, he was least troubled by the greatest—he had no friends. He was dressing for dinner one night when the valet announced a visitor. "Show him up," said Carfew.

There came to him a tall, cadaverous man, with a profusion of hair and a certain untidiness of dress which usually marked the unsuccessful genius.

"Carfew?" he demanded.

The young man nodded.

"Your hand," demanded the other briefly. "Your name I know—I have heard of you. My name is Septimus."

"Glad to meet you, Mr. Septimus," said Carfew formally. "And what goods can we show you this evening?"

Carfew wanted amusement; he could spare this unpromising stranger at least half an hour.

"You don't mind my dressing?" he asked, as he lazily adjusted his tie before the glass.

"Not at all—not at all," said Mr. Septimus, with a fine sweep of his hand. "A busy man—I am no hog." He seemed pleased with the negative illustration, and repeated in a whisper that he was no hog.

"Mr. Carfew," the visitor went on, "I have heard of you. You are the man who negotiated the sale of a certain patent, receiving as your share of the sale many thousands of pounds."

"That's true," said Carfew modestly; "I am best known, perhaps, as Carfew the Inventor."

"I do not know you as Carfew the Inventor," said the seedy man deliberately. "You have a title to fame more wonderful, more extraordinary, more far-reaching for humanity; you have attracted the attention of three men of gifts. Sir, will you honour me with your company this night?"

"My dear chap," said Carfew reproachfully, "to-night! Now be reasonable."

"To-night," said the weird-looking visitor dramatically. "It is not unreasonable, believe me."

He was very earnest, so earnest that Carfew looked at him more closely. His clothes were old and stained, his cuffs were frayed and not over-clean, his neck was innocent of collar; a black silk cravat clumsily tied in a bow left a space of scraggy throat between neckband and neck-wear. He had two days' growth of beard, and yet there was an undefinable air of refinement about him which puzzled the young man. His hands, long, thin, and white, were scrupulously tended.

"We're rather at cross purposes," said Carfew, kindly. "I would do anything to oblige you except"—he was on the point of saying "lending you money," but instinct arrested the speech—"except commit myself to a promise that I might not be able to fulfil. Now, exactly what is it you want?"

The man clicked his lips impatiently.

"I want nothing—absolutely nothing," he said, with a shade of annoyance in his voice. "I have no single desire in the world; there is no material with which, if money could fulfil, would remain unsatisfied. Look here."

He thrust his hand into the baggy pocket of his Inverness, and drew out an untidy bundle of papers. "You think I am a needy adventurer," he said, and it was apparent that his anger was rising; "you imagine that I have come here with some hare-brained scheme—"

"My dear sir!" said Carfew, somewhat embarrassed by the truth of the man's utterance.

"You think this—bah!"

He flung the bundle of papers into the air; they scattered on bed and floor. One fell at Carfew's feet.

"My dear chap," he expostulated, as he stooped to pick it up, "you're only—"

He stopped suddenly, for the paper he held was a Bank of England note for one hundred pounds. There was no doubt whatever as to its genuineness.

And the floor was covered with them. There was a round dozen on the floor, two or three on the eiderdown which covered the bed, two on the dressing-table. Carfew, bewildered, hastened to collect them.

"Money," said the strange visitor bitterly—"money! Do we live for nothing but money? Is that the be-all and end-all of things? Is that the ultimate aim of humanity? Take it—keep it! Add it to your puny store. Tell your friends that Septimus of the Agreeable Company made you a present of it!"

He hitched his worn cloak round his shoulders and flung open the door. "Au revoir!" he said haughtily. "We are not likely to meet again."

He was half-way down the corridor before Carfew recovered from his surprise.

"Hi, come back!" Carfew darted down the corridor and caught the man by the arm. "Come back, come back, for heaven's sake!" he begged. "You mustn't go away and leave me with this money. I don't want the beastly stuff."

"Do you mean that?" There was suspicion in the stranger's frowning glance.

"Absolutely. Just give me a minute."

Reluctantly the man returned, and as reluctantly he took the notes from Carfew's hand and stuffed them into his pocket.

"Count them," said the anxious young man. "One might have gone astray."

"What matters?" responded Septimus carelessly. "I shall be little worse off. Let the man who finds it keep it."

Carfew gazed on him in awe, and for the first time a faint smile played round the thin lips of the seedy visitor.

"I think," he said quietly, "you are a little astonished at my indifference to money—perhaps you think it is an affectation. The truth is, money is of the least importance to me and to the Agreeable Company. For every sovereign you possess, I have probably three hundred. That would make me more than a millionaire, wouldn't it?" He smiled again pityingly. "Money does not count, believe me," he said seriously. "There are three men in the Agreeable Company, and if you were to add their fortunes together, they would—But I will only say that I am the poorest of the trio." Again there was that odd little mannerism, for he repeated, speaking to himself in a voice which was scarcely more than a whisper: "The poorest of the trio—the poorest of the trio!"

Now, Carfew was by every instinct a journalist. His very faults might be traced to this quality, for he would jump at the shadow of a "story," and miss the bone of probability.

And here, indeed, was a story—the Agreeable Company of Millionaires!

"If you could tell me exactly the object of your visit," he said, "and just how I can serve you, I am quite willing to accompany you tonight."

"Are you?" Septimus leant forward eagerly, his eyes shining. "Are you really? Now, that is good of you! I want you to meet Decimus. You will adore Decimus. He is a man after your own heart—a brain ingenious, terrifically introspective, and with the idea."

Carfew, dazed by his tremendous character of the unknown Decimus, could only nod his head.

"The idea is the thing," the stranger went on. "I can see by your eyes that you think I am a little mad—perhaps more than a little. You think we are all a little mad!"

Carfew blushed guiltily.

"Ah, you do! But you shall see," exclaimed the stranger. He rose hitched up his cloak again, and smiled.

"It is now twenty-three minutes past seven by your new watch."

Carfew started and pulled out his new chronometer hastily; it was exactly twenty-three minutes past seven. "How on earth—" he began.

The stranger was amused. "Simple, very simple. You have a new watch—all young men who suddenly acquire wealth have new watches—and new watches keep perfect time. I know it is twenty-three minutes past because it is exactly eight minutes since the clock struck the quarter after. I know it is eight minutes because I have counted four hundred and eighty seconds. One half of my brain is counting all the time. But that is beside the point. It is now twenty-six minutes past seven. Will you meet me in front of the National Gallery at nine o'clock?"

Carfew did not hesitate. "I will," he said.

Septimus stood at the door. "If you have any nervousness, if you are in any way afraid of the consequences of your adventure, I shall not complain if you come armed."

And, with a profound bow, he departed.

Carfew went down to dinner in a condition of mind which it would be difficult to analyse. He had embarked on that variety of enterprise which is dear to a young man's heart—the enterprise which has the necessary envelopment of mystery, and the end of which could not be surmised. He finished his dinner in half the time it usually took, hurried back to his room and changed into a tweed suit. The night was damp and chilly. It offered him an excuse for wearing an overcoat and a soft felt hat, which the remarkable character of the interview justified. Prompt to the minute he took his stand by the steps leading up to the National Gallery. The clocks were striking nine, when a big motor-car, driven slowly from the direction of Pall Mall, drew up, and the stranger got out. By the light of a street standard, Carfew recognised him, though he might have been excused if he had not.

For now Septimus was a radiant being. Dressed in an evening suit of perfect cut, his long hair trimmed and brushed, his lean, intellectual face innocent of scrubbiness, he was the pattern of propriety. He came quickly toward Carfew and held out his hand.

"I am one minute late," he said; "these clocks are slow."

Carfew suddenly realised his own wilful shabbiness. "I am afraid I have changed my kit," he said, and felt unaccountably sheepish.

Septimus smiled. "Please don't bother," he said, and held open the door of the car. "Decimus is no hog either."

Carfew sank back into the luxurious cushions as the car glided noiselessly across Trafalgar Square, and tried to adjust his whirling thoughts.

"I suppose," said his companion, who seemed possessed of a fiendish power which allowed him to read men's minds, "that you are mentally quoting Mr. Pickwick when he found himself in the middle of the night chasing the electric Jingle and the erring sister of Mr. Wardle."

He had put off his eccentric style of address with his seedy costume, and Carfew noted that his voice was soft and cultured. All the extravagance of attitude and language had disappeared. He spoke easily, fluently, of men and things, the news of the day, touching lightly on politics, merely observing that the trend of recent legislation seemed to be in the direction of Socialism. He thought that such legislation was bad for property. It did not affect him, he said; all his money was fluid capital. This was an astonishing statement, for Carfew had never heard of a man whose wealth was so placed.

"I lend money," the other explained—"short loans, you know. It means a quick profit. I would not do this but for Octavius, who is the mortal enemy of laziness. He says that idle money does more mischief than idle men. What a brain that man has—what a brain!"

It was a return of the old enthusiasm, and Carfew waited, but Septimus said no more. The car had crossed Westminster Bridge, had passed through the tangle of traffic at the Elephant and Castle, sped quickly along the gloomy stretch of the New Kent Road into the bustle of the Old Kent Road.

Not another word said Septimus, and Carfew was content to engage himself with his own thoughts. They were climbing the steep hill that leads to Blackheath when Septimus again spoke.

"I have only one request to make to you," he said, "and that is that you do not make any mention of the Straits Settlements to Decimus."

"The—?" asked Carfew, not a little bewildered.

"The Straits Settlements," said the other calmly. "It is the one subject upon which I fear the otherwise perfectly-poised brain of the good Decimus is not too delicately adjusted."

It seemed a subject easy to avoid, and Carfew said as much. The other nodded gravely.

The car flew up the steep hill, turned to the right, and began skirting the heath. Halfway round, it slowed and turned into some grounds through two gaunt gates, along a short, dark avenue of trees, and pulled up before the gloomy door of a big house. There was no light in any window; even the hall was in darkness.

The two men descended, and Septimus, mounting the steps, rang the bell—Carfew heard its far-away tinkle. They waited a little time before the door was opened. The only light in the hall was the candle held by the man who had admitted them.

As the door closed upon them Carfew became conscious of the magnificence of the servitor who held the light. He was a footman of imposing proportions. Clean-shaven, with a quiet dignity of mien, he wore a livery such as the personal attendant of a reigning monarch might have adopted. His coat was of royal blue velvet, thickly laced with gold; his breeches were of white satin, his stockings of rose-pink silk. On his feet he wore the shiniest of patent shoes, adorned with jewelled buckles that flashed back the light of the candle as only diamonds can. His hair was powdered white, the whitest of snowy ruffles were at his wrists, the most snowy of cravats at his throat; across his breast he wore a string of medals such as the domestics of royal households wear. Carfew noted the blue and white of the British House, the yellow and scarlet of Spain, the diagonal stripe of the German, the green and yellow of Austria.

"Messieurs Decimus and Octavius await your Excellencies," said the man, and his voice had exactly the quality of humility which his office demanded. Septimus nodded. He handed his coat to the man, and Carfew followed suit. Now it must be said of Carfew that he was not easily overcome by outward show. He was by instinct and training a journalist, and no journalist permits himself to be impressed. Yet there was something awe-inspiring in the spectacle of that gorgeous lackey in the unfurnished hall.

The dim light of the candle accentuated the desolation of the place. A huge black stairway led to the upper floors. The hall itself was innocent of chair or table, yet the candlestick in the footman's white hand was of silver and most beautifully designed.