RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

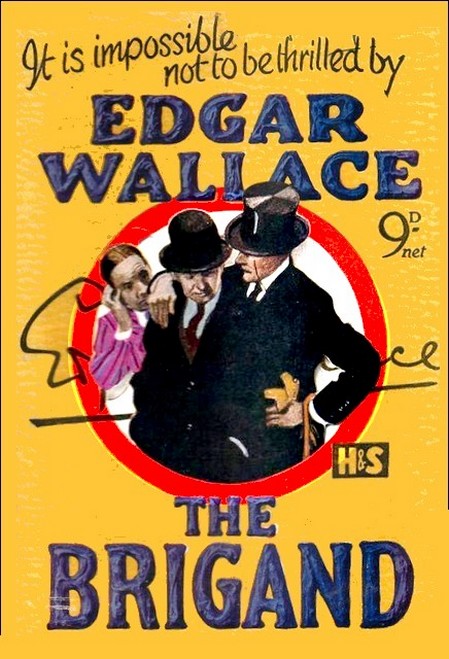

"The Brigand," Hodder & Stoughton, 9-penny reprint

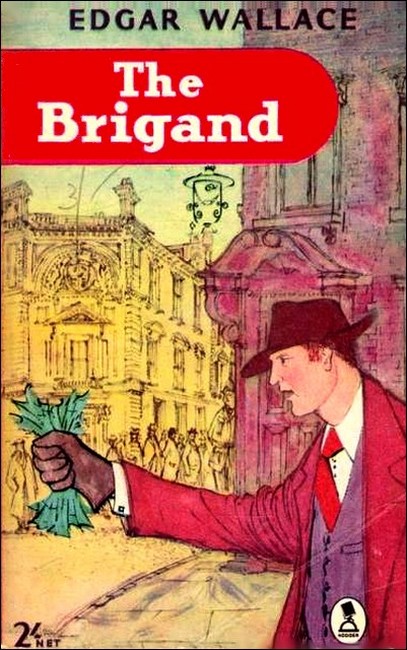

"The Brigand," Hodder & Stoughton paperback, 1957

The Brigand is a patchwork of tales from

different sources. Anthony Newton, the Brigand himself, began

his literary existence as "Captain Reggie Hex" in a series of

seven stories that Edgar Wallace wrote under the pseudonym "E.

Graham Smith" for The Sunday Post, Glasgow, Scotland, in

1919.

The Sunday Post introduced the first story with the words:

"To-day we commence a series of remarkable narratives dealing with the exploits of Captain Hex, a young discharged army officer, who has established a private detective agency, the object of which is to help the ex-Service men and their families who are in dire need. Captain Hex goes about his work in a decidedly novel manner, and devises schemes for procuring munificent sums from those best able to bear the financial burden—even though it is against their wish."

The general title of the series was "The Adventures of Captain Hex." The titles and dates of publication of the stories were:

[* In these stories the hero's first name

was changed from "Reggie" to "Michael." In "Blackmail with

Roses" the villain's name was changed from "Bolivski" to

"Boddin."]

Re-witten versions of the first two stories—"Mr.

Montague Flake, the Margarine King, Hands Over £8,000" and "The

Outwitting of Mr. Theodore Match"— resurface as stories 3

and 4 in The Brigand under the snappier titles "Buried

Treasure" and "A Contribution to Charity."

Other Brigand stories made their first appearance in The

Novel Magazine in 1923 in a series called "The Nerve of Tony

Newton." The titles of the stories in this series were:

The other stories in the book are:

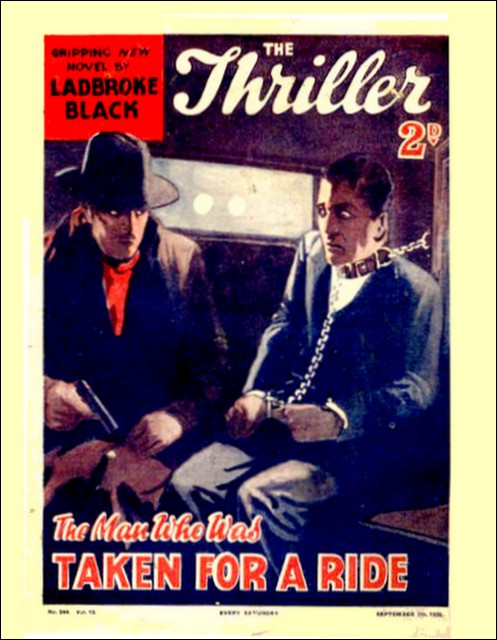

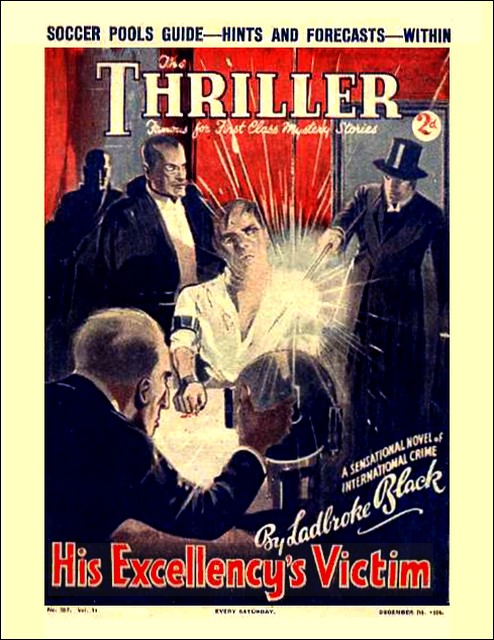

The following Anthony Newton stories are known to have been reprinted in the British juvenile magazine The Thriller in 1935. The titles used in this weekly publication were:

The present RGL edition of The Brigand includes, in addition to this bibliographic note, a number of illustrations from various sources. —Roy Glashan.

Captain Hex (later Anthony Newman)

Portrait from The Sunday Post, Glasgow, February 9, 1919

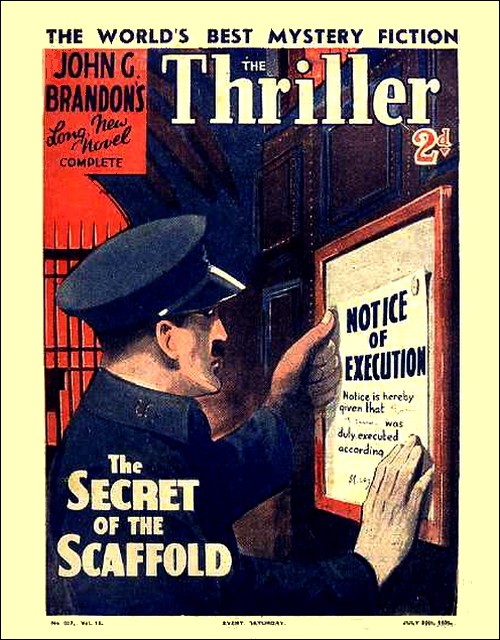

The Thriller, July 20. 1935, with "The Nerve of Tony Newton"

ANTHONY NEWTON was a soldier at eighteen; at twenty-eight he was a beggar of favours, a patient waiter in outer offices, a more or less meek respondent to questionnaires which bore a remarkable resemblance one to the other.

'What experience have you?'

'What salary would you require?'

There were six other questions, all more or less unimportant, but all designed to prove that a Public School education and a record of minor heroisms were poor or no qualification for any job that produced a living wage and the minimum of interest, unless the applicant was in a position to deposit fabulous sums for the purchase of partnerships, secretaryships and agencies.

And invariably:

'I am afraid, Mr Newton, we haven't a place for you at the moment, but if you will leave your address, we will communicate with you just as soon as something comes along.'

Tony Newton struggled through eight years of odd jobs. His gratuity had been absorbed in a poultry farm which as everybody knows, is a very simple method of making money. In theory. And at the end of the eighth year he discussed the situation with himself and soberly elected for brigandage of a safe and more or less unobjectionable variety. His final decision was taken on a certain morning.

Mrs Cranboyle, his landlady, presented a bill and an ultimatum. The bill was familiar—the ultimatum, not altogether unexpected, was both novel and alarming.

He looked at his landlady thoughtfully, and his good-looking face wore an unaccustomed expression of doubt. As for Mrs Cranboyle, a solid, stout woman with a flinty eye and a large, determined chin, she was very definitely beyond any kind of doubt whatever.

Anthony heaved a sigh, and his gaze wandered from his landlady's face to the various features of his small and comfortless room. From the knobbly bed to the 'What is home without a mother?' (a masterpiece of German lithographic art) above the bed board, to the 'All we like sheep have gone astray' above the mantelpiece, to the two china dogs thereon, to the skimpy little hearth-rug before the polished and fireless grate, and then back to Mrs Cranboyle.

'You can't expect me to keep you, Mr Newton,' she said significantly, not for the first time that morning.

'Hush,' said Anthony testily. 'I am thinking.'

Mrs Cranboyle shivered.

'I have worked very hard for all I've got,' she went on, 'and a young man like you should know better than to impose upon a widow who doesn't know where her next pound is coming from—'

'You've got seven hundred and fifty pounds in Government Bonds, two hundred and fifty in the Post Office, and a deposit account at the London and Manchester Bank of nearly five hundred pounds,' said Anthony calmly, and Mrs Cranboyle gasped.

'What—how—' she stammered.

'I was looking through your passbook,' explained Anthony without shame. 'You left it in the drawing-room one day, and I spent a very pleasant afternoon examining it.'

For a moment Mrs Cranboyle was incapable of speech.

'Well, you've got a cheek!' she gasped at last. 'And that settles it! You leave my house to-day.'

'Very good,' said Anthony with a shrug. 'I'll go along and find other rooms, and I'll send a man for my luggage.'

'Send the six weeks' rent you owe,' said Mrs Cranboyle, 'or don't trouble to send at all. If you think I'm going to keep a house open for a gambling, good-for-nothing—'

Anthony raised his hand with some dignity.

'You are speaking to one of your country's defenders,' he said, loftily, 'one who has endured the terrific strain of war, one who, whilst you slept snug in your bed, was dithering through the snow, the sleet, the slush, the fog and the gunfire. Always remember that, Mrs Cranboyle. You can't be sufficiently thankful to men like me.' He glared at her. 'Where would you be if the Germans had won?'

Mrs Cranboyle was quite incapable of speech. She wanted to remind him, for the third time, of the manner in which he had wasted his substance, but he saved her the trouble.

'You tell me I am a gambler,' he said. 'It is true that I backed Hold Tight for the Sheppey Handicap; how true it is, you, who spend your spare time in rummaging amongst my papers, know only too well. Your curiosity will be your ruin.'

He looked out of the window and picked up his hat. Mrs Cranboyle was incapable of comment. She met his stern gaze with the stare of a hypnotised rabbit.

'The least you can do for me, Mrs Cranboyle,' he said sternly, 'is to lend me ten shillings, which will be repaid in the course of the next few hours.'

The landlady came out of her trance, violently.

'Not ten pence—not ten farthings!'

'Your country's defender,' murmured Anthony. 'People like you turn us ex-soldiers into anarchists.'

'If you threaten me, I'll send for the police,' bawled Mrs Cranboyle.

He walked back to the dressing-table, brushed his hair carefully, took up his hat again and put it firmly on his head.

'I will send for my luggage this afternoon,' he said soberly.

She was muttering incoherent and menacing sounds as he walked slowly down the stairs; he realised that the crisis of his life was at hand.

That he was going forth into a hard and unsympathetic world, with six copper coins in his pocket, and the knowledge that he had yet to earn his board and his bed, worried Anthony not at all. He stepped forth into the spring sunlight with a joyous sense of physical well-being and strolled up the suburban street with the carefree air of one who has no worries.

An ex-lieutenant in the Blitheshire Fusiliers, ex-secretary to the veritable Mr Hoad, of Hoad and Evans (Anthony invariably referred to them as 'Odds and Evens', and cherished no malice in his heart against the spluttering and apoplectic Mr Hoad, who had fired him), he knew that the normal sources of income which, at the best, had produced but a trickling stream, were now dried up. He had been fighting when he should have been receiving training and his succession of odd jobs demonstrated the futility of a public school training and a military career as a means of acquiring steady or lucrative employment.

And as Anthony swung on to a bus and paid three of those six remaining coppers of his to the conductor, he had thoroughly made up his mind that the oyster of life was not to be opened either by sword or song.

He spent the morning at the National Gallery, which had ever been a source of inspiration to him, and came out at the hunger hour, singularly deficient in ideas. He was famished, for he was healthy and young and his breakfast had consisted of two hard slices of bread, meagrely buttered and a cup of Mrs Cranboyle's impossible tea.

A policeman saw him standing about on the corner of Trafalgar Square and decided, from his air of indecision, that he was a country or colonial visitor, for Anthony affected soft felt hats, grey and large-brimmed, and he invariably appeared to be well dressed. 'Are you looking for something, sir?' asked the constable.

'I want to know where I can get a good lunch,' said Anthony, truthfully.

'You ought to go to the Pallaterium. A gentleman told me yesterday that that was the best place in London.'

'Thank you, constable,' said Anthony gratefully, and to the Pallaterium he went, for Anthony had faith. He strolled carelessly into the broad vestibule which was crowded with people, the majority of whom were waiting either for guests or hosts, and seated himself in a deep armchair, stretching his legs luxuriously. And from the swing door of the restaurant came a fragrant aroma of food. He watched the greetings between apologetic late arrivals and hypocritical and patient guests; he saw the little family parties drift in and pass into the gilded heaven beyond the glass doors, but he saw nobody that he knew.

Presently four stout people came in, two men and two women. They were expensively dressed, and they were obviously ladies and gentlemen who would not lie awake on hard beds that night, wondering how they might scrounge a good breakfast. He watched them as they, too, went past into the restaurant, and sighed.

'Now, if I were only—' he began, and suddenly an idea occurred to him.

He waited for another ten minutes then, rising slowly, he handed his hat to the cloakroom attendant and passed into the restaurant. He saw the four stout people at a table at the far end of the long room; next to them was a small unoccupied table. The elder of the two men looked up at the sight of a very respectable figure.

'Yes, sir?' he asked.

Anthony bent down and lowered his voice, but it was not so low that all four members of the party could not hear.

'Lord Rothside says he is awfully sorry he can't come, but will you lunch with him instead, at Berkeley Square?'

'Eh?' said the staggered recipient of this invitation.

'You are Mr Steiner, aren't you?' said Anthony, in a tone of apprehension, as though it were beginning to dawn upon him that he had made a mistake.

'No, sir,' said the fat and smiling Hebrew, 'my name is Goldheim. I am afraid you've made a mistake.'

Anthony uttered a 'tut' of impatience.

'I'm awfully sorry, but the fact is I have never met Mr Steiner, and I knew he was lunching here, and—' He broke off in confusion.

'No offence, I'm sure,' said the nattered gentleman. 'I don't know Mr Steiner myself, or I would point him out.' He chuckled round at his companions. 'I've only been mistaken for a friend of Lord Rothside's, that's all,' he said, not without enjoyment.

'I'll wait for him,' smiled Anthony, apologetically. 'I can't tell you how sorry I am to have interrupted you.'

He sat down at the next table; and when the waiter bustled up:

'I am not ordering anything, yet,' he said. 'I am expecting a gentleman.'

At the next table the lunch proceeded and Anthony writhed in agony. Presently one of the party looked round.

'Mr Steiner hasn't come yet, has he?' he asked unnecessarily.

Anthony shook his head.

'I'll wait,' he said, 'though it is rather a nuisance. I am losing my lunch.' There was another interregnum of clattering knives and forks, and then: 'Won't you join us, Mr—?'

'Newton is my name,' said Anthony, 'and really, I don't think it is fair to impose myself upon you.'

But before he had finished the sentence, he was sitting with them, and in five minutes had given his opinion on an excellent Niersteiner.

'Are you Lord Rothside's secretary?'

'Not exactly his secretary,' said Anthony, with a little smile.

He conveyed the impression that the question had been in the nature of a faux pas, and that the position he occupied was something infinitely superior to secretaryship. So might Napoleon have looked if, in the days of the directorate, he had been asked if he was a member of the Government.

The two women were nice-looking motherly ladies, with that sense of humour which Anthony was best able to titillate. He set the table in chuckles as he struggled manfully to overtake them. By the time the coffee stage was reached he was level: he smoked one of Mr Goldheim's cigars with the air of a connoisseur.

'It is strange meeting you like this,' said Anthony reminiscently. 'I shall never forget the first time I dined with the Duke of Minford. I dropped in most unexpectedly, had never met him before, never been introduced, didn't know him from Adam.'

Here, Anthony spoke nothing but the truth, for he had 'dropped in' when His Grace was lying at the bottom of a shell-hole in France, and they had dined upon a biscuit and a bar of chocolate.

'You're in the City, I suppose Mr Newton?'

'I'm everywhere,' said Anthony, vaguely. 'I have a place in the City, of course, but I have only recently returned from abroad.'

Mr Goldheim smiled at him slyly.

'Made a lot of money, eh?'

'Yes, I've made a lot of money.'

'South Africa?'

It was Anthony's turn to smile, but Anthony smiled cryptically. It neither admitted nor denied South Africa. It was a smile which stood as well for the Argentine, Chicago or South America.

'The truth is, I don't know London very well,' he admitted.

All the time he was wondering who were the three quiet, middle-aged men at the next table, who spoke a little, but who gave him the impression that they were listening intently. The first time he noticed them, he realised that they had heard almost every word he had spoken, from his first mention of the great master of finance; and he felt a momentary discomfort. And yet they did not appear to be listening. The man with the big red face, who was nearest to him, seemed utterly absorbed in the meal he was eating. They might have been prosperous farmers in London for the day, or successful north country mill owners.

Soon after, Mr Goldheim called for the bill, tipped the waiter extravagantly (Anthony's palm itched to take back one of the half-crowns), and the party strolled back into the vestibule.

Anthony was the first to hand his check to the cloakroom attendant; and the official accepted Mr Goldheim's tip as for the whole of the party.

'Can we drop you anywhere?' asked that gentleman.

'If you could put me down at the Ritz-Carlton,' Anthony hesitated, 'that is, if it is not out of your way.'

It was not out of their way, for the theatre where they were spending the afternoon was next door to the hotel.

He stood for a moment in the entrance of the hotel waving farewell to his benefactors and then strolled into the reception hall.

'I want a bedroom and a sitting-room,' said Anthony.

He had not the slightest intention of going to the Ritz or to any other hotel; but it seemed such an hotel as a brigand, at sudden war with society, would choose for his headquarters.

'I will bring my baggage in later,' he said, 'but remember, I must have a room overlooking The Mall.'

'What name, sir?'

Anthony signed the book with a flourish, and before the reception clerk could hint gently that rooms could not be reserved for baggageless visitors without a deposit, Anthony was enquiring the exact location of the nearest branch of the Hardware Trust Bank, of New York.

'If you turn to the right when you go out of the entrance, sir, and then turn to the right again, you will find the Trust Company on the left,' said the clerk. 'It is customary in engaging rooms—' and then came a welcome interruption.

A hand fell on Anthony's shoulder, and he turned to look into the smiling eyes of a big jovial man, whose tanned face spoke of an open air life.

'Isn't this Mr Newton?' he asked, wonder and hope in his voice.

Anthony took a step back, and then thrust out his hand.

'By Jove, I don't know your name, but I remember you so well.'

'John Frenchan, of Frenchan and Carter. You remember my store in Cape Town?'

'Remember!' said Anthony ecstatically, and shook the man's hand. 'As if I could forget it! I can't quite recall where I met you, but I know your name as well as my own.'

He turned from the desk; the clerk's face bore a look of resignation. Automatically he placed a room number against Mr Newton's name; in his private register he wrote 'No baggage. OK? The question mark against 'OK' was more than justified.

Anthony's new friend led the way to the lounge, where the coffee and cigar parties were sitting. A waiter came forward expectantly, and spun a chair.

'You've had your lunch? Join me in a cup of coffee,' said Mr Frenchan. 'Did you come over by boat?'

'Yes, on the Balmoral Castle,' said Anthony.

In his capacity of secretary to Hoad and Evans, a firm which conducted an extensive shipping business, he was acquainted not only with the ships of the Castle line, but knew by repute the name of Frenchans. They were amongst the biggest agricultural implement importers at the Cape. Also he was interested in shipping news, and he had noted the arrival of the mail.

'I thought I recognised you in the restaurant,' nodded Mr Frenchan; 'In fact I was sure!'

'Huh?' said Anthony. Now he remembered the three men who had sat at the next table. 'Why, of course! I spotted you and couldn't place you.'

'I suppose you made a lot of money in South Africa, like the rest of us?' Mr Frenchan resented his own share of good fortune if his tone meant anything. 'It's easy enough to make—I was happier when I was earning a few pounds a week. Money? Bah!'

Anthony, who had never had enough money to 'bah!' at, was a little shocked.

'Yes, I made about forty thousand pounds'—he shrugged his shoulders to intimate the absurdity of describing so insignificant a sum as 'money'. 'But I wasn't in Africa very long.'

Mr Frenchan looked at him with a new interest. As the representative of capital, Tony was a possibility—as a capitalist, he was a proposition.

'Do you know the Goldheims very well? I saw you were lunching with them.'

'I don't know them very well,' said Tony, realising that this was a moment for candour. 'In fact, I met them more or less by accident.'

'Smart fellow, Goldheim,' meditated the other, examining his cigar. 'He's in oil—worth a million. Maybe two millions.'

'Dear Me!' said Tony, and to make conversation and at the same time secure a little data, he asked: 'Are you in London for long?'

'For three or four months,' said the other with a grimace of dissatisfaction. 'I shouldn't be here at all if my poor foolish brother hadn't died.'

Anthony wondered whether it was the folly or the poverty of the departed Mr Frenchan which so ruffled his host. Certainly one or the other annoyed him, for he was scowling.

'A man has no right,' he exploded suddenly, 'no right whatever to indulge in eccentric charities. When a man makes a will he should dispose of his property so that it does not hold his relatives up to ridicule, contempt or malice. Envy—yes. But not contempt.'

Anthony agreed.

The hard faced man was blinking indignantly. The memory of his brother's folly apparently stirred all that was uncharitable in his nature. His underlip thrust out aggressively.

'If he wants to leave a thousand to the Stockwell Orphanage, and a thousand to the London Hospital, and ten thousand to the Home for Providing Babies with False Teeth, let him do it! Personally, I never wanted a farthing of his money, neither I nor my family.'

From which lofty declaration of disinterestedness, Anthony gathered that the late Mr Frenchan had not left his brother anything.

'What Church do you attend, Mr Newton?' he asked unexpectedly, and Anthony, for a moment, was taken aback.

'Primitive Methodist,' he said. If Anthony was attached to any sect at all, it was towards Primitive Methodism, the church to which he had been dragged every Sunday morning as a child.

The effect upon Mr Frenchan was electrical. He sat back in his chair and stared at the young man for fully a minute.

'Well, that's a most remarkable coincidence,' he said, slowly. 'You're the first Primitive Methodist I have met in this country!'

Anthony was more than a little astonished. Primitive Methodism acquired a new importance. Never had he imagined this sect of his could provide anything in the nature of a sensation... Almost his heart warmed to the brick chapel of his youth.

What particular significance lay in the fact, Mr Frenchan went on to explain.

'My brother Walter was a bit of a crank. I am not saying that Primitive Methodism is a cranky kind of religion, but Walter carried it to an extreme. He employed nearly two thousand hands in his business, and, if you believe me, sir, nobody had a chance of a job with Walter unless he was a Primitive Methodist. It is a fine religion, I daresay; personally I don't know very much about it. But you might say that Walter lived for the church, and was so bigoted that he could see no good in any other kind of worship. Now, I am sure, Mr Newton, that you, as a man of the world, do not agree that that was an intelligent view to take?'

Anthony murmured his complete disagreement.

'And because he held these eccentric views,' Mr Frenchan went on bitterly, 'he has put me to more trouble than anybody else has ever put me to in my life. I said to my lawyer: "Am I to sit here in London, year after year, looking out for cases of poverty amongst Primitive Methodists, in order to carry out the provisions of Walter's will? I'll be dashed if I do!"'

He grew almost choleric, swallowed the remainder of his coffee savagely. There was a peculiar glitter in his eyes that at first alarmed and then encouraged his companion.

'Will you have a liqueur?' he asked suddenly.

Anthony nodded.

'I should like you to meet my lawyer: he is a man after your own heart, a shrewd man of the world, a little suspicious, but I don't think that any harm in a lawyer. You probably know the firm, Whipplewhite, Summers and Soames.'

Anthony nodded. He had never heard of a firm of lawyers called Whipplewhite, Summers and Soames, but it sounded very much like a firm of lawyers. He knew there was a firm called Bennett, Wilson, Moss, Bennett and Wilson, and he had heard of another firm called Jones, Higgins, Marsh, Walter, Johnson, dark and Higgins, and he was quite prepared to accept so simple a thing as a triple alliance.

Mr Frenchan looked at his watch.

'I wonder if I could catch him?' he said. 'You'd be delighted with him. A dour Scotsman, mind you, but a man with a heart of gold. He looks upon everybody as a potential criminal.' He chuckled to himself, and shook his head. 'I don't know that that is a bad thing in a lawyer,' he reflected.

'It is a very excellent quality, and very much resembles the attitude of my own solicitor towards humanity,' said Anthony sedately. 'After all, lawyers are cautious souls, and the first element of caution is suspicion.'

Mr Frenchan got up.

'Come along. Let us see if we can find him. He is usually to be run to earth in the neighbourhood of the Law Courts about this time and I'd like you to meet him.'

The reception clerk, who looked at him with pleading eyes as he passed, Anthony ignored. It was not desirable that the sordid question of deposits should be mentioned before his opulent friend.

Mr Frenchan called a cab, and they drove down the Strand, halting at the broad entrance of the Royal Courts of Justice.

'Here he is!' cried Mr Frenchan. 'What a bit of luck!'

A thin, cadaverous man, wearing a worried look and a black homburg, was standing on the steps of the Courts in a meditative attitude. He had an expression of profound melancholy and nodded curtly to Mr Frenchan. It was easy to imagine that he regarded the world as a sinful place. He reviewed the throng that hurried past the gates with the basilisk glare of a thwarted executioner.

'I want you to meet my friend Newton, Whipplewhite,' said Frenchan, and the lawyer extended a cold hand. 'Can you come along somewhere? I want to have a talk.'

Mr Whipplewhite shook his sad head.

'I am afraid I can't,' he said shortly. 'I have a case in Court No. 6 in half an hour.'

'Rubbish!' said Mr Frenchan loudly. 'You've got a counsel or whatever you call the fellow, haven't you? Come along.'

Still Mr Whipplewhite was reluctant. 'I'd much rather not,' he said, and looked at his watch. 'I can spare you five minutes, but I can't go very far from the Court.'

'We'll find a teashop, somewhere; a cup of tea won't hurt us, eh, Mr Newton?'

Anything to eat or drink would have hurt Anthony very much at that moment, but he acquiesced, and in a dimly lighted, pokey little teashop, to which the grumbling Mr Whipplewhite led them, Anthony's introduction was continued.

'This is a young gentleman I knew very well in South Africa. Newton —you've heard me speak of him.'

Anthony was still considerably puzzled. That he was being mistaken for somebody else, he had no doubt, but he was patient. The problem of lunch had been settled, dinner seemed a certainty, although he had less inclination for food than he had had for a long time. On one matter he was perfectly satisfied; he would have to produce large and pretentious quantities of baggage before the sloe-eyed reception clerk would hand him the key of his suite. That was a fact. Mr Frenchan was a potential host —though he would not have guessed it.

'By the way, Frenchan, I've taken probate of your brother's will. The net personalty is not six hundred and forty thousand, but five hundred and twelve, six and nine-pence.'

Mr Frenchan made a snarling noise.

'I wish it were six and ninepence,' he said savagely, and the lawyer grunted impatiently. 'I know you think I'm daft,' Mr Frenchan went on, 'but Walter and I were very good pals and, eccentric though his wishes are I intend carrying them out.'

'Why not hand the money over to the church and let them dispose of it?' suggested the lawyer. 'It is the simplest way, and will save you a lot of trouble. Besides, they know more about their own people than you do.'

Mr Frenchan shook his head.

'That would not be carrying out Walter's wishes,' he said firmly. 'How does the will run? "On the first day of January in every year, one-fifth of the residue of my estate shall be placed in the hands of some responsible person for the purpose of distribution."'

'"On the second of January,"' corrected the lawyer. 'But you've got the will a little wrong, Mr Frenchan—it says that "one fifth of my estate shall immediately—"'

'Of course, of course. And then the second fifth to be paid over on the 2nd January; I had forgotten that,' said Mr Frenchan.

The lawyer leant back and chewed a toothpick, his eyes gazing into vacancy.

'What I want to know is,' he said slowly, 'where are you going to find a respectable and responsible person to whom you can entrust these large sums of money? There is no sense in beating about the bush, Frenchan. If you're going to undertake the distribution, all well and good, but how do you know that this money is not going to pass into the hands of some common swindler? I know what you are going to say,' he said, raising a protesting hand, 'that I shall always be around to see that the money is not being put to an improper use: but I am a very busy man and I couldn't undertake the responsibility of guaranteeing that every penny of your brother's money goes to indigent Primitive Methodists. It is absurd to expect me to do so. What you want is a substantial man who can be trusted implicitly, who has money of his own, and some sort of position. In those circumstances I should say go ahead, but unless you find that man, my dear Frenchan, you must remain in England for the next five years —you may groan, but I am talking practical common sense—and undertake the disbursement of the money yourself.'

'That I cannot do,' said Mr Frenchan, emphatically. 'Besides, I'm not a Primitive—by George!' He looked at Anthony. 'This gentleman is a Primitive Methodist.'

'You are not suggesting that you can place this heavy responsibility upon a young man who is probably making his way in the world, and either has not the, time or the inclination towards philanthropic enterprises?'

Anthony listened in silence, wondering... amazed... comprehending.

'Now, look here, Whipplewhite,' said Frenchan sharply. 'I can't allow you to speak in any way disparagingly of Mr Newton. You have known me for many years, and you are aware that my judgment is never at fault so far as human nature is concerned. I know Mr Newton's character almost as well as I know yours.'

'I agree that you are a pretty shrewd judge of men,' said the other reluctantly, 'but here we are dealing with a fantastic, if I may say so, a stupid will, the provisions of which can only be carried out—'

'Can only be carried out by a man of honour,' said Mr Frenchan shortly.

The lawyer shook his head.

'Honour is all very well,' he said doggedly, 'but it is money that counts. If this gentleman has money—if he can show me ten thousand pounds—'

The heart of Anthony Newton was singing a hymn of thankfulness, but his voice was a little husky when he spoke.

'If you will step round to my bankers—' he began, and then: 'I don't know that I want to undertake such a mission, and please, Mr Frenchan, do not insist, but if you are in any doubt as to my financial stability, and if you will come with me to my bank and see the manager, I have no doubt he will put your mind at rest.'

'What did I say?' said Mr Frenchan triumphantly. 'Will you oblige Mr Newton by walking round to his bank?'

'I haven't time to go to any banks,' snarled the lawyer. 'I told you I had a case.' He rose as he spoke. 'But if Mr Newton can, between now and this evening, produce five thousand pounds, and can show me that sum in his possession, then I, as one of the trustees of your brother's estate, will agree.'

'You are too damned particular,' said Frenchan angrily, 'and I am not going to ask my friend Newton to do anything so absurd.'

'Not at all,' said Anthony politely. 'I quite understand Mr Whipplewhite's objection, and if you will name a time and a place, I shall be most happy to bring you five thousand pounds, though of course I am not prepared to hand it over to you.'

'I don't want you to hand it to me,' said Mr Whipplewhite sharply. 'I merely want to see it.'

Anthony breathed deeply.

'There is just time to get to the bank,' he said. 'Now, where shall I meet you?'

'Meet me at the Cambrai Restaurant, Regent Street, at half-past seven. I can't get away before. Will that suit you, Frenchan?'

'I object to the whole proceeding,' said Mr Frenchan, who appeared to be considerably ruffled. 'But if Mr Newton in his generosity agrees to your plan which is to my mind almost as eccentric as my poor brother's will, it is not for me to object.'

It was a quarter to three when Anthony hurried from the coffee house. He could have wished that he might, within view of his new-found friend, leap upon a taxi and give spectacular orders, but the truth was that he had not even a bus fare. He made his way on foot to the park, and strolled along the path looking for discarded newspapers. He found two, and, discovering a secluded seat, he sat down and carefully tore the newspapers into uniform oblong slips, stacking them one after the other into both sides of his faded wallet until it was swollen.

He was so intent upon his work that he did not notice the presence of a man who had approached across the grass, and now stood watching him.

'Making a collection of press cuttings?' asked the voice and Anthony looked round.

There was no reason for him to doubt the profession of his interrupter. Anthony nodded cheerfully. 'I am indeed,' he said.

'What is the idea?' said the man, in a more official tone.

'Each of these is a ten pound banknote,' said Anthony.

The man sat down on a seat beside him.

'It almost sounds as if you and I were going to get better acquainted,' he said.

'I admit it. You're an officer from Scotland Yard, aren't you?'

'I don't know how you guessed it, but you're nearer the truth than you're ever likely to be.'

'Are there many confidence gangs working in London just now?'

'There are about four,' said the officer. 'How people get taken in by them I don't know. Is somebody after you?'

Anthony nodded.

'Then you're a fellow to keep under observation,' said the detective with amusement.

'For the Lord's sake, don't,' replied Anthony in alarm. 'Tell me, what is their modus operandi?'

'Come again?' said the detective as a matter of principle.

'What is their method of working?'

'They've only got one method,' said the other, 'and if you've met them you ought to know all about them. They are generally people who have got money to distribute to the poor and needy. Somebody leaves money for that purpose and they are looking for an honest, respectable lad without brains to whom they can hand the money, without fear that he will blue it on champagne and girls.'

'They are very unoriginal,' smiled Anthony.

'As unoriginal as greed,' said the other, 'and it is the greed in human nature that they work on. Have they got you for a sucker?'

Anthony nodded.

'I am a young man from South Africa with great possessions,' he said, simply. 'This evening I am going to show them five thousand pounds in order to prove my bona fides.'

The detective glanced at the pocket book.

'Sic 'em!' he said, preparing to go. 'And if they give you any trouble afterwards, here's my card.'

At half past seven that night, Anthony kept his appointment. He found the lawyer already waiting for him, reading the evening newspaper, a small glass of absinthe before him.

'A pernicious drink, Mr Newton,' he said, 'but I find it is very beneficial. I suffer from indigestion. I suppose you haven't seen Mr Frenchan?'

Anthony shook his head.

'A strange man, a very trusting man, and how he ever keeps out of scrapes heaven only knows,' said the lawyer in despair. 'He would trust anybody. He would trust a tramp in the street. I hope, Mr Newton, that you are not feeling very sore with me, but a lawyer has to be a little inhuman.'

'That I understand,' said Anthony heartily, and at that moment Frenchan came in.

They talked for a while on an item of news which was being advertised on all newspaper bills and placards, and then Mr Frenchan, with a sigh, said: 'Well, let us to business, and get it over.'

He produced a heavy wallet and took out a wad of notes.

'What on earth did you bring that for?' asked the lawyer.

'Because,' said Mr Frenchan emphatically, 'I thought if you could not trust Mr Newton, there was no reason why Mr Newton should trust us. I do trust Mr Newton, I trust him implicitly.'

'Don't raise your voice,' said the lawyer. 'There is no need to make a disturbance.'

'And Mr Newton trusts me.'

'Have you brought the money?' asked the lawyer practically.

Anthony produced his heavy wallet.

'What did I tell you?' said Frenchan, for the second time that day. 'A man of substance and a man of honour, Whipplewhite. Will you do me a favour?'

He leant across the table and spoke earnestly to Anthony.

'Certainly, Mr Frenchan.'

Mr Frenchan tossed his wallet into Anthony's lap.

Take that wallet and go outside for five minutes, and then return,'

'But why?' asked Anthony, raising his eyebrows.

'To show that I trust you. And I daresay you would do the same for me?'

'Most certainly I would,' said Anthony.

He picked up the wallet.

'But there is a lot of money here, isn't there? I wish you would count it.'

'There is no necessity to count it,' said the other, loftily. Nevertheless, he pulled open the flap and took out a wad of notes. He turned over the first batch of notes and Anthony saw that they were each for ten pounds. Beneath were sham 'Bank of Engraving' notes, he guessed, but those on top were genuine enough.

'I don't like doing it,' he said, as he took the wallet from the other. 'After all, you don't know me.'

'I think I should accede to Mr Frenchan's rather remarkable request,' said the lawyer gently, and Anthony slipped the case into his pocket, and went slowly from the restaurant. A taxi cab was passing.

'Don't stop,' he said, as he ran up to the slowing vehicle. 'Drive me to Victoria.'

As the cab flashed through the darkening streets, he took the wallet and extracted its contents. The twenty top notes were gloriously genuine.

In the restaurant Mr Whipplewhite and Frenchan waited.

'A bright kid,' said Mr Frenchan.

'Ain't they all bright?' said the other contemptuously. 'Ain't they all clever? It is only the clever ones that fall. Hullo!' He looked up with a start to meet the eyes of a soldierly looking man.

'Hullo, Dan, waiting for a mug?'

'I don't know what you mean, sergeant,' said Frenchan. 'We are waiting for a friend of ours.'

'You'll wait a long time, that's my opinion,' said Sergeant Maud, of Scotland Yard. 'I have been watching that lad all the afternoon.'

He clicked his teeth cheerfully, and viewed with great joy the consternation and horror that was dawning on the faces of his victims.

'It is occasions like these, Dan, that make all the policemen in heaven rise up and sing hallelujah,' he added.

POLITE brigandage has its novel aspects and its moments of fascination. Vulgar men, crudely furnished in the matter of ideas, may find profit in violence, but the more subtle and the more delicate nuances of the art of gentle robbery had an especial attraction for one who, in fulfilment of the poet's ambition, could count the game before the prize.

So it came about that Mr Newton found himself in an awkward situation. The two near wheels of his car were in a ditch; he with some difficulty had maintained himself at the steering wheel, though the branches of the overhanging hedge were so close to him that he had to twist is head on one side. Nevertheless, he maintained an attitude of supreme dignity as he climbed out of his car, and the eyes that met the girl's alarmed gaze were full of gentle reproach.

She sat bolt upright at the wheel of her beautiful Daimler, and for a while was speechless.

'You were on the wrong side of the road,' said Tony gently.

'I'm awfully sorry,' she gasped. 'I sounded my horn, but these wretched Sussex lanes are so blind...'

'Say no more about it,' said Anthony. He surveyed the ruins of his car gravely.

'I thought you would see me as you came down the hill,' she said in excuse. 'I saw you and I sounded my horn.'

'I didn't hear it,' said Anthony, 'but that is beside the question. The fault is entirely mine, but I fear my poor car is completely ruined.'

She got out and stood beside him, the figure of penitence, her eyes fixed upon the drunken wreck.

'If I had not turned immediately into the ditch,' said Anthony, 'there would have been a collision. And it is better that I should ruin my car than I should occasion you the slightest apprehension.'

She drew a quick sigh.

'Thank goodness it is only an old car,' she said. 'Of course, Daddy will—'

Anthony could not allow the statement to pass unchallenged.

'It looks old now,' he said gently; 'it looks even decrepit. It has all the appearance of ruin which old age, alas, brings, but it is not an old car.'

'It is an old model,' she insisted. 'Why, that's about twenty years old—I can tell from the shape of the wing.'

'The wings of my car,' said Anthony, 'may be old fashioned. I am an old fashioned man, and I like old fashioned wings. In fact, I insisted upon having those old fashioned wings put on this perfectly new car. You have only to look at the beautiful coach work—the lacquer—'

'You lacquered it yourself,' she accused him. 'Anybody can see that that has been newly done.' She touched the paint with her finger, and it left a little black stain. 'There,' she said triumphantly, 'It has been done with "Binko", you can see the advertisements in all the papers: "Binko dries in two hours."' She touched the paint again and looked at the second stain on her finger. 'That means you painted it a fortnight ago,' she said, 'it always takes a month to dry.'

Anthony said nothing. He felt that her discovery called for silence. Moreover, he could not, for the moment, think of any appropriate rejoinder.

'Of course,' she went on more warmly, 'it was very fine of you to take such a dreadful risk. My father, I know, will be very grateful.'

She looked at the car again.

'You don't think you could get it up,' she said.

Anthony was very sure he could not restore the equilibrium of his car. He had bought it a week before for thirty pounds. The owner had stuck out for thirty-five, and Anthony had tossed him thirty pounds or forty, and had won. Anthony always won those tosses. He kept a halfpenny in his pocket which had a tail on each side, and since ninety-nine people out of a hundred say 'heads' when you flip a coin in the air, it was money for nothing.

'Shall I drive you into Pilbury?' she said.

'Is there anywhere I can find a telephone?' asked Anthony.

'I'll take you back to the house,' said Jane Mansar suddenly. 'It's quite near, you can telephone from there, and I'd like you to have a talk with father. Of course, we will not allow you to lose by your unselfish action, though I did sound my horn as I came round the corner.'

'I didn't hear it,' said Anthony gravely.

He climbed in, and she backed the car into a gateway, turned and sped at a reckless pace back the way she had come. She turned violently from the road, missed one of the lodge gates by a fraction of an inch and accelerated up a broad drive to a big white house that showed sketchily between the encircling elms. She braked suddenly and Anthony got out with relief.

Mr Gerald Mansar was a stout, bald man, whose fiery countenance was relieved by a pure white moustache and bristling white eyebrows. He listened with thunderous calm whilst his pretty daughter told the story of her narrow escape.

'You sounded your horn?' he insisted.

'Yes, father, I am sure I sounded the horn.'

'And you were going, of course, at a reasonable pace,' said Mr Mansar.

In his early days he had had some practice at the law in the County Courts. Anthony Newton recognised the style and felt it was an appropriate moment to step in.

'You quite understand, Mr Mansar, that I completely exonerate Miss Mansar from any responsibility,' he interjected. 'I am perfectly sure she sounded the horn, though I did not hear it. I am completely satisfied and can vouch for the fact that she was proceeding at a very leisurely pace, and whatever fault there was, was mine.'

Anthony Newton was a very keen student of men, particularly of rich men. He had studied them from many angles, and one of the first lessons he learnt in presenting a claim, was to exonerate these gentlemen from any legal responsibility. The rich hate and loathe the onus of legal responsibility. They will spend extravagant sums in law costs to demonstrate to the satisfaction of themselves and the world that they are not legally responsible for the payment of a boot-black's fee. The joy of wealth is generosity. There was never a millionaire born who would not prefer to give a thousand than to pay a disputed penny.

Mr Mansar's puckered face relaxed.

'I shall certainly not allow you to be the loser, Mr—'

'Newton is my name.'

'Newton. You are not in the firm of Newton, Boyd and Wilkins, are you, the rubber people?'

'No,' said Anthony. 'I never touch rubber.'

'You are not the pottery Newton, are you?' asked Mr Mansar hopefully.

'No,' said Anthony gravely, 'we have always kept clear of pots.'

After Mr Mansar had, by cross-examination, discovered that he wasn't one of the Warwickshire Newtons, or Monmouth Newtons, or a MacNewton of Ayr, or one of those Irish Newtons, or a Newton of Newton Abbot, but was just an ordinary London Newton, his interest momentarily relaxed.

'Well, my dear,' he said, 'what shall we do?'

The girl smiled.

'I think at least we ought to ask Mr Newton to lunch,' she said and the old man, who seemed at a loss as to how the proceedings might reasonably be terminated or developed, brightened up at the suggestion.

'I noticed that you mentioned me by name. Of course, my daughter told you—' he said.

Anthony smiled.

'No, sir,' he replied, 'but I know the city rather well and, of course, your residence in this part of the world is as well known as—'

'Naturally,' said Mr Gerald Mansar. He had no false ideas as to his fame. The man who had engineered the Nigerian oil boom, the Irish linen boom, who floated the Milwaukee paper syndicate for two millions, could have no illusions about his obscurity.

'You are in the city yourself, Mr Newton?'

'Yes,' admitted Anthony.

He was in the city to the extent of hiring an office on a first floor of a city building; and it was true he had his name painted on the door. It was an office not big enough to swing a cat, as one of his acquaintances had pointed out. Anthony however, did not keep cats. And if he had kept them, he would certainly have never been guilty of such cruelty.

The lunch was not an unpleasant function, for a quite unexpected factor had come into his great scheme. Nobody knew better than Anthony Newton that it was Mr Mansar himself who every Saturday morning drove the Daimler into Pullington, and when Anthony had purchased his racketty car, spending many hours in the application of 'Binko' to endow it with a more youthful complexion, he had not dreamt that the adventure would end so pleasantly. He knew that Mr Millionaire Mansar had a daughter—he had a vague idea that somebody had told him she was pretty. He did not anticipate when he engineered his accident so carefully, that it would be at her expense.

For, whatever else he was, Anthony Newton was an honest adventurer. He had decided that there was money in honest adventure; he had reached this conclusion after he had made a careful study of the press. There were other adventurers whose names figured conspicuously in the police court reports. They were all ingenious and painstaking men, but their ingenuity and foresight were employed in ways which made no appeal to one who had strict, but not too strict, views on the sacredness of property.

Some of these adventurers had walked into isolated post offices, a mask over their faces and a revolver in their hands and had carried off the contents of the till, amidst the loud protests of postal officials who were on the spot. Others had walked into banks similarly disguised and had drawn out balances which were certainly not due to them.

And Anthony, thinking out the matter, decided that it was quite possible, by the exercise of his mental talent, to secure quite a lot of money without taking the slightest risks.

He wished to know Mr Mansar. Mr Mansar, in ordinary circumstances, was unapproachable. To step into his office and demand an interview was almost as futile as stepping up to the stamp counter in St Martin's-le-Grand, and asking to see the Postmaster-General. Mr Mansar was surrounded by guards, inner and outer, by secretaries, by heads of departments, by general managers and managing directors, to say nothing of commissionaires, doorkeepers, messengers and plain clerks.

There are two ways of getting acquainted with the great. One is to discover their hobbies, which is the weakest side of their defence, and the other is to drop in upon them on their holidays. The man you cannot meet in the City of London is very accessible in the Hotel de la Paix.

But apparently Mr Mansar never took a holiday, and his only hobby was keeping alive an illusion of his profound genius.

Lunch over, and Anthony's object achieved, there seemed no excuse for his lingering. He awaited, with some confidence, the grave intimation that a car was ready to take him to the station, and that Mr Mansar would be glad if he would dine with him at his London house on Thursday. Maybe it would be Wednesday. Possibly, thought Anthony, the function might be deferred for a week or two. But the intimation did not come. He was treated as though he had arrived for a permanent stay.

Mr Mansar showed him the library, and told him to make himself comfortable, pointing out certain books which had amused him (Mr Mansar) in his moments of leisure.

Anthony Newton cooed and settled himself, not perhaps to read, but to think large and beautiful thoughts of great financial coups which he might engineer with this prince of financiers, of partnerships maybe, certainly of profits.

There was a big window looking out upon a marble terrace and as he read, or pretended to read, Mr and Miss Mansar paced restlessly along the paved walk. They were talking in a low voice and Anthony, having surrendered all sense of decorum, crept nearer to the window and listened as they passed.

'He is much better looking than the last one,' murmured Jane, and he saw Mr Mansar nod.

Much better looking than the last one? Anthony scratched his head.

Presently they came back.

'He has a very clever face,' said Jane, and Mr Mansar grunted.

Anthony had not the slightest doubt as to whom they were talking about. When she said 'clever face' he knew it was himself.

They did not return again, and Anthony waited on, a little impatient, a little curious; he had decided that he himself would make a move to go, when Mr Mansar came into the library and carefully closed the door behind him.

'I want a little talk with you, Mr Newton,' he said solemnly. 'It has occurred to me that you might be of the very greatest service to my firm.'

Anthony cleared his throat. The same thought had occurred to him also.

'Do you know Brussels at all?'

'Intimately,' said Anthony promptly. He had never been to Brussels, but he knew that he could get a working knowledge of the city from any guide book.

Mr Mansar stroked his chin, pursed his lips, frowned, and then:

'It is providential your arriving,' he said. 'I have a very confidential mission which I have been looking for somebody to undertake. In fact, I thought of going to town this afternoon to find a man for the purpose but, as I say, your arrival has been miraculously providential. I have been discussing it with my daughter, I hope you will forgive that little impertinence,' he said, courteously.

Anthony Newton forgave him there and then.

'My daughter, who is a judge of character, is rather impressed by you.'

It was clear to Anthony now that he had been the subject of the conversation he had overheard. He was tingling with curiosity to discover exactly the nature of the mission which was to be entrusted to him. Mr Mansar did not keep him waiting long.

'I want you to go by to-night's train to Brussels. You will arrive on Sunday morning, and remain there until Wednesday morning. Have you sufficient money for your journey?'

'Oh, yes,' said Anthony, airily.

'Good.' Mr Mansar nodded gravely, as though he had never had any doubt upon the matter. 'You will carry with you a sealed envelope, which you will open on Wednesday morning in the presence of my Brussels agent, Monsieur Lament, of the firm of Lament and Lament, the great financiers, of whom you must have heard.'

'Naturally,' said Anthony.

'I want you to keep your mission a secret, tell nobody, you understand?'

Anthony understood perfectly.

'I leave the method of travel to you. There is a train to London in half an hour; here is the letter.'

He took it from his inside pocket. It was addressed to Mr Anthony Newton, and marked 'To be opened in the presence of Monsieur Cecil Lament, 119, Rue Partriele, Brussels.'

T do not promise you that you will be paid very well or even be paid at all, for undertaking this mission,' said the millionaire. 'But I rather fancy this experience will be useful to you in more ways than one.'

Anthony detected a certain significance in this cautious promise and smiled happily.

'I think I'll go along now, sir,' he said briskly. 'When I carry out these missions—and as you may guess, this is not the first time that I have been—entrusted with important errands—I prefer that I should lose no time.'

'I think you're wise,' said Mr Mansar soberly.

Anthony hoped to see the girl before he went, but here he was disappointed. It was a very ordinary chauffeur who drove him to the station and, passing the wreckage of his car stranded in the ditch, Anthony did not regret one single penny of his expenditure. Anyway, the car would still sell for the price of old iron.

He reached Brussels in time for breakfast on Sunday morning, and on the Monday he made a call at Monsieur Lament's office. Monsieur Lament was a short, stout man, with a large and bushy beard, and seemed surprised at the advent of this spruce and mysterious young Englishman.

'From M'sieur Mansar,' he said with respect, even veneration. 'M'sieur Mansar did not tell me he was sending anybody. Is it in connection with the Rentes?'

'I am not at liberty to say,' said Anthony discreetly, 'In fact, sir, I am, so to speak, under sealed orders.'

Monsieur Lament heard the explanation and nodded.

'I honour your discretion, M'sieur,' he said. 'Now is there anything I can do for you while you are in Brussels? Perhaps you would dine with me to-night at my club.'

Anthony was very happy to dine with him at his club, because he had brought with him a grossly insufficient sum to pay his expenses.

Over the dinner that nigh, Monsieur Lament spoke reverently of the great English financier.

'What a wonderful man?' he said, with an expressive gesture. 'You are a friend of his, M'sieur Newton?'

'Not exactly a friend,' said Anthony carefully, 'how can one be a friend of a monument? One can only stand at a distance and admire.'

'True, true,' said the thoughtful Monsieur Lament. 'He is indeed, a remarkable character. And his daughter—' he kissed the tips of his fingers, 'what charm, what intelligence, what beauty!'

'Ah!' said Anthony, 'what!'

So charming a companion was he, that Monsieur Lament asked him to lunch with him the next day, and this time the Belgian showed some curiosity as to the object of Anthony's visit.

'Is it in connection with the Turkish loan?' he asked.

Anthony smiled.

'You will, I am sure, agree with me that I must maintain the utmost secrecy,' he said firmly.

'Naturally! Of course! Certainly!' said Monsieur Lament hastily. 'I honour your discretion. But if it is in connection with the Turkish loan, or the Viennese Municipal loan—'

Anthony raised his hand with a gesture of gentle insistence.

Monsieur Lament dissolved into apologies.

Anthony was himself curious and he attended M. Lament's office on Wednesday morning with a joyous sense of anticipation.

In that rosewood-panelled room standing with his back to the white marble fireplace, he tore the flap of the envelope with fingers that shook, for he realized that he might be at the very crisis of his career; and that his good plan to drop into financial society had succeeded beyond his wildest hope.

To his amazement, the letter was from Jane Mansar, and he read it, open-mouthed.

'Dear Mr Newton:

Daddy wants to hand you over to the police or have you ducked in the pond. I chose this method of giving you a graceful exit from the scene, because I feel that such a man of genius and valour should not be subjected to so ignominious a fate. You are the thirty-fourth person who has secured an introduction to my father by novel, and in some cases, painful, methods. I have been rescued from terrifying tramps (who have been hired by my rescuer) some six times. I have been pushed into the river and rescued twice. Daddy has had three people accidentally wounded by him when he has been shooting rabbits, and at least five who have got into the way of his car when he has been driving between the house and the station.

We do recognize and appreciate the novelty of your method, and I confess that for a moment I was deceived by the artistic wreckage of your poor little car. To make absolutely sure that I was not doing you an injustice, I telephoned the local garage, and found, as I expected, that you had kept the car there for a fortnight before the 'accident'. Poor Mr Newton, better luck next time.

Yours sincerely,

Jane Mansar.

Anthony read the letter three times, and then looked mechanically at the slip of paper which was enclosed. It ran:

To MONSIEUR LAMONT,

Pay Mr Anthony Newton a sum sufficient to enable him to reach London, and to support him on the journey.

Gerald Mansar.

Monsieur Lament was watching the dazed young man.

'Is it important?' he asked eagerly. 'Is it to be communicated to me?'

Anthony was never wholly overcome by the most tremendous circumstances. He folded the letter, put it in his pocket, looked at the slip again.

'I regret that I cannot tell you all that this contains,' he said. 'I am leaving immediately for Berlin. From Berlin I go to Vienna, from Vienna to Istanbul; from there I must make a hurried journey to Rome, and from Rome I have to get to Tangier. Then I shall reach Gibraltar in a month's time, and fly to England.'

He handed the slip to Monsieur Lament.

'Pay Mr Anthony Newton a sufficient sum to enable him to reach London and support him on the journey.'

Monsieur Lament looked at Anthony. 'How much will you require, M'sieur?' he asked respectfully.

'About nine hundred pounds, I think,' said Anthony softly.

Monsieur Lament gave him the money then and there and when Mansar got the account he was justifiably annoyed.

He came into Jane, storming.

'That... that...' he spluttered, 'rascal...'

'Which rascal, Daddy, you know so many,' she was half smiling.

'Newton... as you know, I gave Lament an order to pay his expenses to London?'

She nodded.

'Well, he drew nine hundred pounds.'

The girl opened her eyes with joyous amazement.

'He told Lament that he was coming home by way of Berlin, Vienna, Istanbul and Rome,' groaned Mr Mansar. 'Thank God the trans-Siberian railway isn't working!' he added. It was the one source of comfort he had.

Belshazzar Smith (renamed Bill Farrel in "The

Brigand")

The Sunday Post, Glasgow, February 18, 1919

MR TONY NEWTON threw up the window of his sitting-room and looked across the chimney tops of Bloomsbury with a critical eye.

It was a sunny day, and even chimney stacks and gaunt dead-ends have a poetry in the golden light of an early morning in summer to a young man plentifully endowed with faith in his own capabilities.

Big Bill Farrel was his companion, and Bill had just finished at his leisure a large plateful of ham and eggs, and now, with a pipe between his teeth, was at peace with the world.

'Voila!' said Anthony gravely, and with a wave of his hand indicated a number of portraits (mainly cut from newspapers) which decorated one wall of his room.

He walked to the wall where his picture gallery offended the unities, and stabbed with his finger portrait after portrait, as he reeled off their titles and biographies.

'That's William O. McNeal, real name Adolph Bernsteiner, the Meat King; that is Harry V. Teckle, the Steel King; that is Theodore Match, the Shipping King; that is Montague G. Flake, the Provision King; this fellow with the funny nose is Michael O. Blogg, the Jam King—and that fellow with the glasses is the Cotton King; and that lad with the dyspeptic eye and the diamond pin is the Hardware King—bow to Their Majesties, Bill. They are going to make us rich!'

'Eh?' said the startled and baffled Mr Farrel.

They are our little Eldorados,' said Tony calmly, 'our Pay Cash or Bearers; our Money from Home!'

'Do you mean they're relations of yours?' asked Bill, in tones of awe.

'God forbid!' said Mr Newton piously. 'Sit you down and I'll expound the Plan of Operations and the General Idea.'

For an hour he expounded his scheme, and comprehension came very slowly to Bill, but it came.

'And now,' said Tony, getting up, 'we will go to the little office which I have rented in Theobald's Road.'

Painted on the uncleanly glass panel was the inscription:

NEWTON'S DETECTIVE AGENCY

From a drawer in the one table of the room, he took a large card, similarly painted.

'You will find two nails outside the door,' said Tony, 'and your job will be to hang it out every morning and take it in every night, providing the youth of Bloomsbury does not pinch it.'

When Bill returned, his friend was reading a newspaper cutting.

'Listen to this. It is a description of a sale at Floretti's. "A small box of miscellaneous manuscript went to the bid of Mr Montague Flake at 120 guineas. The box is of carved Spanish mahogany," etc., etc. I will not bother you with the details. The point is that Mr Flake is a great collector of old manuscript and a great hog.'

From his wallet he took another and a smaller cutting.

'Listen,' he said, and read: '"A bargain: Small cottage with one acre. Cottage could be made a comfortable weekend residence. Price £1000 for quick sale."' He took a time table from his desk and turned the leaves. 'Here is the place: the train leaves at twelve.'

'I am to buy this property?' said Big Bill, open-mouthed. Tony nodded.

That is your job,' he said. 'It will interest you to know that I have already inspected it, and have an architect's plan in my bedroom. Nevertheless, don't close the deal until you get a telegram from me. You are not to communicate with me except through this office, and under no circumstances are you to disclose the fact that you know me or have any business dealings with me.'

An hour later Big Bill left and Anthony returned to his little hotel, took off his coat and set to work. In a box in his bedroom were half a dozen sheets of age-stained parchment. He spent the rest of the morning and the greater part of the afternoon covering these with fine writing.

There is no more highly respected figure in financial and business circles than Mr Montague Flake, for Mr Flake controlled the butter markets of London, Copenhagen, Rotterdam and many others. From which it may be gathered that Mr Flake was a considerable personage even before the time he managed to corner the butter supplies, to say nothing of the cold storage butter and the butter in transit and the butter of unborn generations of cows.

Officially, Mr Flake did not control the market. Officially he had nothing to do with the cornering of margarine. In all his stores—and there were 631 branches of Flake U.P. Stores throughout the United Kingdom—the 'U.P.' standing for 'Universal Provisions'—there was a large notice respectfully informing customers that the management was doing its best to get supplies of butter and margarine, but that the failure of the hay crop in Denmark, and the root crop in Ireland, was causing much embarrassment, whilst the extra cost of freights (which really worked out at an additional farthing per pound), compelled the reluctant directors to raise the price of butter 3d per pound, and margarine 2d.

And the customers were duly impressed, and, what is more to the point, they paid, and millions of tuppence—ha'pennies went into Mr Flake's pocket, for he was the company, the directors and the shareholders.

Mr Flake had a large house in St John's Square, in the most fashionable part of London. He had a model farm in Norfolk, an estate in Kent, a shoot in Yorkshire and a salmon river in Scotland. He could neither farm, shoot nor fish, but these were the correct things to own, so he owned them.

It is said that his own idea of happiness was to sit in a secluded spot on the edge of the lake on his estate, dabbling his bare feet in the water and smoking a clay pipe, whilst he read the divorce cases in the Sunday newspapers.

He was a harsh-faced man, wholly unsuggestive of butter or anything oleaginous or suave. He was a widower, and lived alone, save for a housekeeper, three secretaries, four chauffeurs, twelve menservants and a small army of white-capped cooks, housemaids and the like.

Mr Flake sat in his magnificent library at a table much larger than the room in which the majority of his customers slept, and he was nibbling his pen, for he was in the agony of composition. He had scratched out twenty lines when a visitor was announced. He took up the card that lay on the silver plate and read the inscription without any show of interest. It read:

THE NEWTON PRIVATE DETECTIVE AGENCY

Captain

Anthony Newton, DSO, MC,

late Blitheshire Fusiliers

He glared up at his secretary, who had followed the footman into the room.

'What does he want? Tell him to write.'

'He insists upon seeing you, sir,' said the footman. 'I told him you were busy.'

'Show him in,' growled Mr Flake.

Tony was ushered in, very grave, very business—like and very well dressed.

'Sit down. Captain—er—Newton,' said Mr Flake, waving his lordly hand to a chair. 'What can I do for you?'

Mr Newton removed his gloves slowly, laid them beside his hat, took out his pocket-book and consulted the interior.

'A few days ago,' he said, 'you purchased a number of miscellaneous manuscripts at Floretti's sale.'

Mr Flake nodded.

'They were the property,' Tony went on, 'of the late Lord Witherall, who was a collector, and they comprised a number of more or less important documents—'

'More or less worthless,' interrupted Mr Flake brusquely. 'As a matter of fact, I bought that lot for the box more than for the manuscripts. I haven't had time to look through them yet.' Tony's eyes gleamed. 'And I don't suppose the manuscripts are worth tuppence.'

'It was on the subject of the manuscripts I wanted to see you,' said Tony. 'I have been employed by a client to interview you under peculiar circumstances. A former confidential servant of Lord Witherall gave into his lordship's custody certain documents, the particulars of which I am not at liberty to give, and these, according to the man's relatives —he has been dead some years, by the way—were kept by his lordship in that particular box. The man's name was Samuels, though that was not the name he was known by to Lord Witherall. If that document is in your possession—it is in the form of a letter addressed to Samuels —my client is willing to pay you £200 for its return.'

Now Mr Flake was, above all things, a good business man, and a good business man knows instinctively that a first offer of £100 for anything means that it is worth much more. And a good business man, moreover, has ever an eye to the main chance.

Mr Flake pressed a bell, and, when his secretary appeared:

'Bring me that box I bought at Floretti's the other day,' he said. 'I can tell you this,' he said, when the girl had gone, 'that I do not promise that I can return any document which may be in this box. A deal's a deal. Captain Newton, and I am a business man.'

Tony nodded.

'I can only remind you,' he said gently, 'that the relatives of Samuels are very poor people, and from what I gather that document may be of the greatest value to them.'

'And to me,' said Mr Flake pleasantly. 'I am poor, too. We are all poor—it is a relative term, as we are on the subject of relatives,' he added humorously.

'I don't think you can compare your condition with theirs, sir,' said Anthony with dignity, 'and I feel sure that you would not attempt to benefit at the expense of poor people—'

'Rubbish!' snapped Montague Flake. 'There is no sentiment in my composition, sir. I am a self-made man, and I have made my money without worrying very much about the people who have had to part. A bargain is a bargain. If I pay 120 guineas for a poke, I'm entitled to the pig I find in it. That's fair, ain't it—isn't it, I mean? Mind you, I'm not going to say I won't sell it,' he added, as the secretary placed the box on the big table before him, 'and I'm not going to say I will.'

He cut the sealed cords which bound the box, and threw open the lid. It was filled to the top with yellow manuscripts. Some were bound together in vellum books, and there were a large number of loose sheets.

Mr Flake hesitated and, lifting out the first stratum, laid it on the desk.

'You say it is a letter?' he said.

Tony nodded.

'This is evidently the manuscript of an old play,' said Mr Flake; 'and this'—he lifted another weighty pile—'seems to be the original manuscript of a story of some kind. Here are the letters.' He picked one up, turned it over to read the signature, and laid it on the table.

Tony turned to the waiting secretary, and then to Mr Flake with an air of indecision.

'I wonder if your secretary would be good enough to look up the telephone number of Sir John Howard and Sons.'

He named the greatest of the London solicitors, a name which carried respect even to Mr Flake.

'Are you acting for Howard?' he asked quickly.

Anthony smiled.

'For the moment I cannot disclose my principals,' he said.

He looked round and waited until the door closed behind the girl; then he sidled close to Mr Flake.

'I can tell you this in confidence,' he said in a low voice. I am acting for—'

He whispered a name in Mr Flake's ear. To reach the financier he had to come round to the corner of the table. As he whispered, he obscured for a moment Mr Flake's view of the box. With somebody whispering in your ear, it is difficult to detect the rustle of parchment.

Tony's hand shot into the open box, and was out again before Mr Flake could recover from his surprise.

'Tup?' said Mr Flake irritably. 'Who the dickens is Tup?'

'That,' said the suave young man, 'I will reveal at some later stage of the enquiry. I thought you knew.'

Mr Flake looked at him searchingly, but the eyes of Tony Newton did not falter.

'Anyway,' said the financier, as he bundled the documents back into the box, 'I haven't time to go through these things now, and I shan't be able to give you an answer for a few days.'

'But it is urgent.' Tony was earnest again. 'If it is a question of money we shall not quarrel over a few hundreds. It is absolutely necessary that we should get this document back immediately.'

'And it is absolutely necessary,' said Mr Flake good-humouredly, 'that I should have my afternoon tea and that I should have time to examine the contents. I will give you your answer to-morrow.'

With this the visitor had to be content. He left the house, curiously enough, without discovering the telephone number he had enquired for, and made his way to the nearest post office. He sent a telegram addressed to 'Smith, Bull Hotel, Little Wenson, Kent,' and the message was: 'Close the deal.'

Four days later a large car drew up before a very small cottage a mile from the village of Little Wenson, and Mr Flake descended.

The cottage was a poor sort of dwelling; the garden was neglected and the windows uncurtained; but he was less interested in the house than in the acre of kitchen garden, equally neglected, which stood at its rear.

Fortunately, he was able to make his reconnaissance without effort, for the cottage stood at the corner of a lane and the western limit of the garden ran flush with the hedge. There were two apple trees, and beyond the broken wall of a well with its crazy windlass.

Mr Flake walked slowly back to the front of the cottage, pushed open the gate, walked along the garden path and knocked at the door. A man in his shirt sleeves answered: a tall, solemn-looking man, who answered Mr Flake's cheery 'Good morning!' with a non-committal nod.

'Is this your house?' asked Mr Flake pleasantly.

'Yes, sir,' said Big Bill Farrel, the cottager.

'Rather nice situation,' said Mr Flake.

'It's not so bad,' said the other, cautiously.

'Been here long?'

'About a week,' said the occupant. 'I haven't been out of the army long, and I thought of starting a poultry farm.'

'Oh, so you were in the army?' said Mr Flake, patronisingly. 'Well, it doesn't seem the right kind of place to raise chickens. Who owned it before you?'

'I forget the name,' said the cottager, 'but it's been in the same family for hundreds of years.'

'H'm!' said Mr Flake. Then, carelessly: 'Can't you recall the name?'

'Something like Samson,' said the cottager, with an effort of memory.

'Was it Samuels?' asked Mr Flake, eagerly.

'Ah, that's the name, Samuels. They weren't the last tenants, but they were the people who owned it years ago.'

'H'm!' said Mr Flake again. 'If it isn't asking you a rude question, what did you pay for it?'

'All the money I had,' parried the other skilfully. 'And as the song says—'

'Yes, yes,' said Mr Flake. I know what the song says, but now, tell me—what would you sell this little property for?'

'I wouldn't sell it,' said the cottager.

'Come, come, you'd sell it for a hundred pounds' profit, surely?' said Mr Flake.

'Not for a thousand pounds' profit,' said the other, determinedly. 'Not for ten thousand pounds' profit. There's some funny tales going about this property. I had a lawyer down here the other day and a private detective.'

'The devil you did!' said Mr Flake. 'Come, now, let's talk business. I am a business man, and I will give you two thousand pounds for this property.'

'If you offered me twenty thousand pounds I wouldn't take it,' said the cottager, with greater determination than ever. 'I am satisfied with it, and, as Socrates says: "Contentment is natural wealth; luxury is artificial poverty."'

'Never mind about Socrates,' said the impatient Mr Flake. 'I will give you—'

'"If man knew what felicity dwells in the cottage of a godly man," says Jeremy Taylor,' the cottager insisted.

'Now look here.' Mr Flake was aroused. 'Will you take a reasonable price for this property? I've got a fancy for it and I will pay anything in reason.'

'Come inside,' said the cottager opening the door. An hour later Mr Farrel shook the dust of Little Wenson from his feet. He was accompanied to London by Mr Flake, and together they journeyed to a bank in Lombard Street, for Mr Farrel admitted to a wholesome horror of cheques, and not until he had received large bundles of banknotes did he affix his signature to the deed which transferred his property to Mr Flake.

It was a long time since Mr Flake had done a day's hard digging, but he felt that he was being well repaid for his labours when, at six o'clock the next morning, he began his excavations. A line drawn at right angles from the centre of the two apple trees passed the well on the right hand side. This was exactly as the document in his possession said it should pass.

Those three sheets of parchment written in a crabbed hand, described how one William Samuels had in the year 1826 stolen from the strong rooms of Cheals Bank, at which he was employed as a porter, 'brilliant stones to the value of £120,000, the property of the French emigre, the Marquis du Thierry', and of how he had hidden that same in the garden of his brother, Henry Frederick Samuels, in the parish of Little Wenson. Mr Flake consulted them again and again. The directions worked out with magnificent accuracy. Nine feet three inches at the right angle from a line drawn between the two apple trees brought the seeker after stolen wealth to the centre of a newly dug garden plot. Four feet down Mr Flake's heart leapt when he came to the 'square flat stone which I have put atop of the Hole in which said Box is Hidden'.

The said box was there. A perspiring Mr Flake discovered it after three hours' strenuous digging and brought it to the light. It looked strangely new. Indeed an ordinary person might have confused it with one of those solid boxes which farmers employ to send eggs by rail. It was heavy, but Mr Flake did not feel its weight as he carried it to the seclusion of the cottage and prized off its top.

It was heavy because it was half-filled with sand. He ran his hand through the sand, and his fingers encountered a square piece of cardboard, which he took out and carried to the light, for he was a thought near-sighted.

There was one line of writing, and that in the same crabbed calligraphy as the letter he had found in his box of manuscript—though, if he had examined that box before Mr Newton had whispered in his ear, he might have saved himself a great deal of labour and no small amount of money.

The inscription ran:

'TUP means The Unfortunate People, on whose behalf I am acting.'

The next morning Mr Flake waited upon Mr Newton. 'You