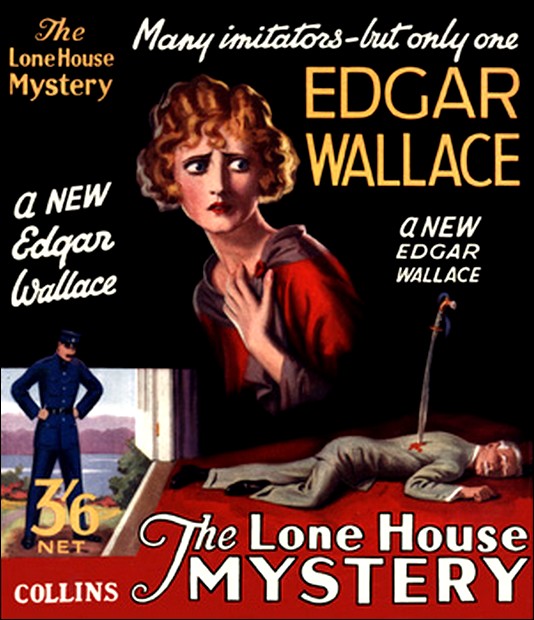

The Lone House Mystery, William Collins & Sons, London, 1929

Detective Story Magazine, 28 September 1929,

with the first part of "The Lone House Mystery."

I AM taking no credit out of what the newspapers called the Lone House Mystery. I've been long enough in the police force to know that the man who blows his own trumpet never gets into a good orchestra. So that, if anybody tells you that Superintendent Minter of Scotland Yard is trying to glorify himself, give them a dirty look for me.

"Superintendent" is a mouthful, and anyway, it is not matey. Not that I encourage young constables to call me "Sooper" to my face. They never do. I want " sir " from them and every other rank, but I like to overhear 'em talking about the old Sooper, always providing they don't use a certain adjective.

Mr. John C. Field always called me Superintendent. I never knew until he pronounced the word that there were so many syllables in it.

No man likes to admit he was in error, but I'm owning up that I broke all my rules when I liked him at first sight. It's all very well to go mad about a girl the first time you meet her, but it's wrong to file a man on your first impressions. Because a man who makes a hit the first time you meet him is going out of his way to make you think well of him. And normal men don't do that. Commercial travellers do and actors do, but they're not normal.

John C. Field was the type that anybody could admire. He was tall, broad-shouldered and good-looking, for all his fifty odd years and his gray hair. He had the manners of a gentleman, could tell a good story and was a perfect host. He never stopped handing out the cigars.

I met him in a curious way. He lived in a smallish house on the banks of the Linder. I don't suppose you know the Linder—it's a stream that pretends to be a river until it runs into the Thames between Reading and Henley, and then it is put into its proper place and called the "Bourne." There is a house on the other side of the stream called Hainthorpe, and it was owned by a Mr. Max Voss. He built it and had an electric power line carried from Reading. It was over this line that I went down to make inquiries. I was in the special branch of Scotland Yard at the time and did a lot of work that the county police knew nothing about. It is not an offence to use electric power, but just about this time the Flack brothers and Johnny McGarth and two or three of the big forgery gangs were terribly busy with private printing presses, and when we heard of a householder using up a lot of juice we were a bit suspicious.

So I went down to Hainthorpe and saw Mr. Voss. He was a stout, red-faced man with a little white moustache, who had lost the use of his legs through frostbite in Russia. And that is how his new house came to be filled with electric contraptions. He had electric chairs that ran him from one room to another, electric elevators, and even in his bath-room a sort of electric hoist that could lift him from his chair into his bath and out again.

"Now," he said, with a twinkle in his eye, "you'll want to see the printing presses where I make phoney money!"

He chuckled with laughter when he saw he'd hit the right nail on the head.

I went there for an hour and stayed three days.

"Stay to-night, anyway," he said. "My man Veddle will give you any sleeping kit you require."

Voss was an interesting man who had been an engineer in Russia. He wasn't altogether helpless, because he could hobble around on crutches, though it wasn't nice to see him doing it.

It was pretty late when I arrived, so I did not need any persuasion to stay to dinner, especially when I heard that young Garry Thurston was coming. I knew Garry—I'd met him half-a-dozen times at Marlborough Street and Bow Street and other police courts. He had more endorsements on his driving licence than any other rich young man I know. His hobbies were speeding through police traps and parking in unauthorised places. A bright boy—one of the new type of criminals that the motoring regulations have created.

He had a big house in the neighbourhood and had struck up a friendship with Mr. Voss. I suppose I'm all wrong, but I like these harum-scarum young men that the public schools and universities turn out by the thousand.

He stopped dead at the sight of me in the smoking room.

"Moses!" he said. "What have I done?"

When I told him that I was after mere forgers he seemed quite disappointed.

He was a nice boy, and if I ever have the misfortune to be married and have a son, he would be the kind that would annoy me less than any other. I don't know what novelists mean when they write about "clean-limbed men," unless they're talking about people who have regular baths, but I have an idea that he was the kind of fellow they have in mind.

We were half-way through dinner when I first heard the name of Mr. Field. It arose over a question of poaching. Voss remarked that he wished Field's policemen would keep to their own side of the river, and that was the first time I knew that Field was under police protection, and asked why. It was then that young Thurston broke in.

"He'll need a regiment of soldiers to look after him if something happens which I think is happening," he said, and there was something in his tone which made me look at him. If ever I saw hate in a man's eyes I saw it in Garry Thurston's.

I noticed that Mr. Voss changed the subject, and after the young man had gone home he told me why.

"Thurston is not normal about this man Field," he said, "and I needn't tell you it's about a girl—Field's secretary. She's a lovely creature, and so far as I can tell Field treats her with every respect and deference. But Garry's got it into his thick head that there's something sinister going on over at Lone House. I think it's the psychological result of poor Field living in a place called Lone House at all!"

That explained a lot to me. Young men in love are naturally murderous young animals. Whether it's normal or abnormal to want to murder the man who squeezes the hand of the young lady you've taken a fancy to, I don't know. I guess it's normal. Personally speaking, I've never been delirious except from natural causes.

"Field's policemen" rather puzzled me till Mr. Voss explained. For some reason or other Field went in fear of his life, and paid a handsome sum per annum for individual police attention. There were usually two men on duty near the house all the time.

I couldn't have come to a better man than Max Voss to hear all the news of the neighbourhood. I think that red-faced old gentleman was the biggest gossip I have ever met. He knew the history of everybody for twenty miles round, could tell you all their private business, why engagements were broken off, what made Mrs. So-and-So go to the Riviera in such a hurry last March, and why Lord What's-his-name was selling his pictures.

And he told me quite a lot about Field. He lived alone except for a few servants, and had no visitors, with the exception of a negro who came about once a month, a well-dressed young fellow, and a rather pretty half-caste woman who arrived at rare intervals.

"Very few people know about this. She comes up river in a launch, sometimes with the negro and sometimes without him. They usually come in the evening, stay an hour or two and disappear. Before they come, Field sends all his servants out." I had to chuckle at this. "Sounds to me like a mystery." Voss smiled. "It is nothing to the mystery of Lady Kingfether's trip to North Africa," he said, and began to tell me a long story.

It was a pretty interesting story. Every time I woke up something was happening.

I went to bed late and tired, and getting up at six o'clock in the morning, dressed and went out into the garden. Mr. Voss had told me his man Veddle would look after me, but devil a sign of Veddle had I seen, either on the previous night or that morning, and I understood why when I came upon him suddenly on his way from the little cottage in the grounds where he lived. He tried to avoid me, but I've got pretty good eyesight for a man of sixty. No man who had ever seen Veddle could forget him. A heavy- looking man with a roundish face and eyes that never met you, I could have picked him out a mile away. When Voss had said "Veddle," I never dreamed he was the same Veddle who had passed through my hands three times. Naturally, when criminals take on respectable employment they become Smith.

He knew me, of course.

"Why, Mr. Minter," he said in his oily way, "this is a surprise!"

"Didn't know I was here, eh?" I said.

He coughed.

"Well, to tell you the truth, I did," he said, "but I thought it would be better if I kept out of your way. Mr. Voss knows." he went on quickly.

"About your previous convictions?"

He nodded.

"Does he know that two of them were for blackmail?" I asked.

He smiled lopsidedly at this.

"It's a long lane that has no turning, Mr. Minter. I've given up all that sort of thing. Yes, Mr. Voss knows. What a splendid gentleman! What a pity the Lord has so afflicted him!"

I didn't waste much time on the man. Blackmail is one of the crimes that makes me sick, and I'd sooner handle a bushel of snakes than deal with this kind of criminal. Naturally I did not mention the conversation to Voss, because the police never give away their clients. Voss brought up the subject himself at lunch.

"That man Veddle of mine is an old lag," he said. "I wondered if you'd recognise him. He's a good fellow, and I think I pay him enough to keep him straight."

I didn't tell him that you couldn't pay any criminal enough to keep him straight, because there isn't so much money in the world, because I did not want to discourage him.

I saw Veddle again that afternoon in peculiar circumstances. He was always a bit of a dandy, and had considerable success with women of all classes. No man can understand the fascination which a certain kind of man exercises over a certain kind of woman. It isn't a question of looks or age, it's a kind of hypnotism.

I was taking a long walk by myself along the river bank. The river separated Mr. Voss's property from the Lone House estate. Lone House itself was a square, white building that stood on the crest of a rising lawn that sloped up from the river, which is almost a lake here, for the stream broadens into what is known locally as the Flash.

A small wood on Mr. Voss's side of the river hides the house from view. I was coming out of Fay Copse, as it was called, when I saw Veddle waiting by the edge of the stream. A girl was rowing across the Flash. Her back was turned to the servant, and she did not see him till she had landed and tied up the boat. It was then that he approached her. I was naturally interested, and walked a little slower. If the girl did not see Veddle, Veddle did not see me, and I was within a dozen yards of the two when he went up to her, raising his hat.

I don't think I've ever seen anybody so lovely as this girl, Marjorie Venn, and I could quite understand why Garry Thurston had fallen for her. Except for police purposes, I can't describe women. I can write down the colour of their eyes and hair, their complexion and height, but I've never been able to say why they're beautiful. I just know they are or they're not; and she was.

She turned quickly and walked away from the man. He followed her, talking all the time, and presently I saw him grip her by the arm and swing her round. She saw me and said something, and Veddle turned and dropped his hand. She did not attempt to meet me, but walked off quickly, leaving the man looking a little foolish. But it's very difficult to embarrass a fellow who's done three stretches for felony. He met me with his sly smile.

"A nice little piece that," he said—"A friend of mine."

"So it appears," said I. "Never seen anybody look more friendly than she did."

He smiled crookedly.

"Women get that way if they like you," he said.

"Who was the last woman you blackmailed?" I asked; but, bless you, you couldn't make him feel uncomfortable. He just smiled and went on his way.

I watched him, wondering whether he was trying to overtake the girl. He hadn't gone a dozen paces when, round the corner of a clump of trees, came swinging a man who I guessed was Field himself. You can tell from a man's walk just what is in his mind, and I wondered if Veddle was gifted with second sight. If he had been he would have run, but he kept right on.

I saw Field stand squarely in his path. He asked a question, and in another second his fist shot out and Veddle went down. To my surprise he made a fight of it, came up again and took a left swing to the jaw that would have knocked out any ordinary man.

It wasn't any business of mine, but I am an officer of the law and I thought it was the right moment to interfere. By the time I reached Mr. Field, Veddle was running for his life. I was a little taken aback when Field held out his hand.

"You're Superintendent Minter? I heard you were staying in the neighbourhood," he said. "I hope you're not going to prosecute me for trespass—this is a short cut to Hainthorpe Station and I often use it. I don't know whether Mr. Voss objects."

Before I could tell him I didn't know what was in Mr. Voss's mind about trespassing he went on:

"Did you see that little fracas? I'm afraid I lost my temper with that fellow, but this is not the first time he has annoyed the young lady."

He asked me to come over to his house for a drink and, going back to where the skiff was moored, he rowed me across. We landed at a little stage and walked together up the lawn to the open French windows of his study. I noticed then that in front of these the grass was worn and that there was a patch of bare earth—it's funny how a police officer can register these things automatically.

The little study was beautifully furnished, and evidently Mr. Field was a man who had done a lot of travelling, for all the walls were covered with curios: African spears and assegais, and on the shelves was a collection of native pottery. He saw me looking round and, walking to the wall, picked down a broad-bladed sword.

"This will interest you if you know anything about Africa," he said. "It is the Sword of Tuna. It belonged to the Chief of Ituri—a man who gave me a lot of trouble and who predicted that it would never be sheathed till it was sheathed in my unworthy person."

He smiled.

"I took it from his dead body after a fight in the forest, so his prediction is not likely to be fulfilled."

The blade was extraordinarily bright, and I told him that it must take a lot of work to keep it polished, but to my surprise he said that it was made from an alloy which always kept the blade shining—a native variety of stainless steel.

He replaced the sword, and for about a quarter of an hour we talked about Africa, where, he told me, he had made his money, and of the country, and only towards the end of our conversation did he mention the fact that he had a couple of detectives watching the house.

"I've made many enemies in my life," he said, but did not explain any further how he had made them.

He rowed me back to the other side of the Flash and asked me to dinner. I was going the following night. He was the kind of man I liked: he smoked good cigars, and not only smoked them but gave them to the right kind of people.

On my way back to Hainthorpe I met Mr. Voss, or, rather, he nearly met me. The paths of his estate were as level as a billiard table and as broad as an ordinary drive, and they had need to be, for he drove his little electric chair at thirty miles an hour. It was bigger than a bath chair and packed with batteries, and if I had not jumped into the bushes I should have known just how heavy it was.

I did not think it was necessary to hide anything about Veddle, and I told him what I had seen. He was blue with rage.

"What a beast!" he said. "I have given that man his chance and I would have forgiven a little light larceny, but this is an offence beyond forgiveness."

Every afternoon he was in the habit of driving to the top of Jollyboy Hill, which gave him a wonderful view of the surrounding country, and, as he offered to put his chair into low gear, I walked up by his side, though it was a bit of a climb. From the top of the hill you saw the river stretching for miles, and Lone House looked a pretty insignificant place to be the homestead of a thousand acres.

In the opposite direction I could see Dobey Manor, an old Elizabethan house where Garry Thurston's ancestors had lived for hundreds of years.

"A nice boy, Garry," said Mr. Voss thoughtfully. "Don't tell him about Veddle—I don't want a murder on my hands."

I dined with him that night, though I ought to have gone back to London, and he arranged that his car should pick me up at Lone House after my dinner and take me down.

"You are very much favoured," he said. "From what I hear, Field does not invite many people to his house. He is rather a recluse, and all the time I have been here he has not been to see me or asked me to pay him a visit."

I saw Veddle that evening. He had the most beautiful black eye I had ever seen on a man, but, as he did not speak about the little scrap, I thought I'd be tactful and say nothing.

I was just a little bit uneasy because Veddle was marked on the police books as a dangerous man. He had twice fought off detectives who had been sent to arrest him and had once pulled a gun on them. I happen to know this because I was one of the detectives.

In the morning I was strolling in the garden when I saw him coming from his little cottage, and thought it wise to offer a few words of advice.

"You got what you asked for," I said, "and if you are a wise man you'll forget what happened yesterday afternoon."

He looked at me a bit queerly. I'll swear it was one of the few times he ever looked any man in the eyes. "He will get what is coming to him," he said, and turned immediately away.

That afternoon I sat on the terrace at Hainthorpe. It was a warm, drowsy day after a heavy shower of rain, and I was half asleep when I saw Mr. Voss move along the path in front of the terrace in his electric chair. He was going very fast. I watched him till he disappeared in the little copse near the river's edge and saw the chair emerge on the other side and come up the winding path towards Jollyboy Hill.

Mr. Voss always wore a white bowler hat and gray suit, and it was easy to pick these up even at a distance of a mile and a half, for, as I say, my eyesight was very good.

He was there longer than usual this day—he told me he never stayed more than ten minutes because he caught cold so easily. While he was there my eyes wandered to the copse, and I saw a little curl of smoke rising and wondered whether somebody had lit a fire. It was pretty hot—the sort of day when wood fires break out very easily. The smoke drifted away and presently I saw Mr. Voss's chair coming down the hill and pass through the wood. A few minutes later he was waving his hand to me as he turned the chair on to the gentle incline which led to the front of the house. He guided the machine up to where I sat—the terrace was broad and stone-flagged.

"Did you see some smoke come over that wood? I thought the undergrowth was on fire."

I told him I had seen it. He shook his head.

"There was nothing there, but I was a little alarmed. Last year I lost a good plantation through gipsies lighting a fire and forgetting to put it out before they left."

We talked for a little while and he told me he had made arrangements for his Rolls to pick me up at Lone House at ten.

"I hope you won't tell Garry about Veddle," he said. "I am getting rid of him—Veddle, I mean. I heard so many stories about this fellow in the village, and I can't afford to have that kind of man round me." He questioned me about Veddle's past, but naturally I was cautious, for, no matter how bad a man is, the police never give him away. He knew, however, that Veddle had been charged with blackmail, and I thought it necessary that I should tell him also that this ex-convict was marked dangerous at headquarters.

He asked me to come into the house with him as Veddle had gone out for the afternoon, and I helped him into the lift and into the little runabout that he kept on the first floor. I was thoroughly awake by the time I got back to the terrace and sat down to read through a case which was fully reported in that morning's newspaper and in which I had an interest. I had hardly opened the paper before one of the maids came out and said I was wanted on the telephone. I didn't know the man who called me, but he said he was one of the detectives engaged to look after Mr. Field. I didn't recognise the voice.

"Is that Superintendent Minter?... Will you come over to Lone House? Mr. Field has been murdered... "

I was so surprised that I could not speak for a moment.

"Murdered!" I said. "Murdered?"

Then, hanging up the receiver, I dashed out of the house and ran along the path through the wood to the place immediately opposite Lone House. The detective was waiting in a boat. He was so agitated and upset that I could not make head or tail of what he was saying. He ran across the lawn and I followed him.

The French windows were wide open, and even before I entered the room I saw, on the damp, brown earth before the door, a distinct imprint of a naked foot. The man had not seen it, and I pushed him aside just as he was going to step on it.

I was first in the room and there I saw Field. He was lying in the centre of the floor, very still, and from his back protruded the hilt of the Sword of Tuna.

I DIDN'T have to be a doctor to know that Field was dead. There was very little blood on the floor, considering the size of the sword blade, and the only disorder I could detect at the moment was a smashed coffee cup in the fireplace and a little table which had held the coffee service overturned on the floor. The second cup was not broken; the coffee pot had spilt on the carpet—when Field fell he might have overturned the table, as I remarked to the detective, whose name was Wills.

Now in a case like this a detective's work is usually hampered by a lot of squalling servants who run all over the house and destroy every clue that is likely to be useful to a police officer; and the first thing that struck me was the complete silence of the house and the absence of all servants. I asked Wills about this.

"The servants are out; they've been out since lunch time," he said. "Mr. Field sent them up to town to a charity matinee that he'd bought tickets for."

He went out into the hall and I heard him call Miss Venn by name. When he came back: "She must have gone out too," he said, "though I could have sworn I saw her an hour ago on the lawn."

I sent him to telephone to his chief. I'm the sort of man who never asks for trouble, and there's no better way of getting trouble than interfering with the county constabulary. I don't say they are jealous of us at Scotland Yard, but they can do things so much better. They've often told me this.

While he was 'phoning, I had a look at Field. On his cheek was a wound about two inches long, little more than a scratch, but this must have happened before his death, because in his pocket I found a handkerchief covered with blood. There was nothing I could see likely to cause this wound except a small paperknife which lay on a table against the wall. I examined the blade: it was perfectly clean, but I put it aside for microscopic examination in case one of these clever Surrey detectives thought it was necessary. I believe in giving the county police all the help you can, and anyway it was certain they'd call in somebody from the Yard after they'd given the murderer time enough to get out of the country.

Leading from the study were two doors, one into the passage and the other into a room at the back of the house. On the other side of the passage was a sort of drawing-room and the dining-room. I say "sort of drawing-room " because it was almost too comfortable to be a real drawing-room.

I tried the door of the back room: it was locked. Obviously there was another door into the same room from the passage, but I found this was locked too.

When Wills came back from 'phoning—he'd already had the intelligence to 'phone a doctor—he told me the story of the discovery. He was on duty single-handed that afternoon; the second detective attached to the establishment had gone to town in Mr. Field's car to the charity matinee. Wills said that he had been told to hang around but keep well away from the house, and not to take any notice of anything he saw or heard. It was not an unusual instruction apparently.

"Sometimes," said Wills, "he used to have a coloured woman and a negro lad come down to see him. We always had the same instructions. As a matter of fact, I was watching the river, expecting them to turn up. They usually arrived on a motor-boat from down-stream, and moored off the lawn."

"You didn't see them to-day?" I asked.

He shook his head.

"No; only the instructions I had to-day were exactly the same as I had when they were expected, and usually all the servants were sent out—and Miss Venn."

I made a quick search of the house. I admit that curiosity is my vice, and I wanted to know as much about this case as was possible before the Surrey police came in with their hobnailed boots, laying their big hands over all the finger-prints. At least, that's what I felt at the time.

I was searching Field's bedroom when Wills called me downstairs.

"It's the deputy chief constable," he said.

I didn't tell him what I thought of the deputy chief constable, because I am strong for discipline, and it's not my job to put young officers against their superiors. Not that I'd ever met the deputy chief constable, but I'd met others.

"Is that you, Minter? Deputy chief constable speaking."

"Yes, sir," I said, expecting some fool instructions.

"We've had particulars of this murder 'phoned to us by Wills, and I've been through to Scotland Yard. Will you take complete charge of the case? I have your own chief constable's permission."

Naturally, I was very pleased, and told him so. He promised to come over later in the afternoon and see me. I must say this about the Surrey constabulary, that there isn't a brighter or smarter lot in the whole of England. It's one of the best administered constabularies, and the men are as keen a lot of crime-hounds as you could wish to meet. Don't let anybody say anything against the Surrey constabulary—I'm all for them.

My first search was of the desk in the study. I found a bundle of letters, a steel box, locked, and to which I could find no key, a loaded revolver, and, in an envelope, a lot of maps and plans of the Kwange Diamond Syndicate. I knew, as a matter of fact, that Field was heavily interested in diamonds, and that he had very valuable properties in Africa.

In another drawer I found his passbook and his bank deposit book and with these a small ledger which showed his investments. As near as I could gather, he was a half-a-million man. I was looking at this when Wills came in to tell me that Mr. Voss was on the other bank and wanted to know if I could see him. I went down to the boat and rowed across. He was in his chair, and he held something in his hand which looked like a big gun cartridge.

"I've heard about the murder," he said "I'm wondering whether this has got anything to do with it."

I took the cartridge from him; it smelt of sulphur. And then, from under the rug which covered his knees, he took an awkward-looking pistol.

"I found them together in the copse," he said, "or at least, my servants found them under my directions. Do you remember the smoke, Minter—the smoke we saw coming from the trees?"

I'd forgotten all about that for the moment, but now I understood.

"This is a little smoke bomb. They used them in the war for signals," said Voss.

His thin face was almost blue with excitement.

"The moment I heard of what had happened at Lone House, I remembered the smoke—it was a signal! I got my chair out and came straight away down with a couple of grooms, and we searched the copse thoroughly. We found these two things behind a bush—and something else."

He dived again under the rug and produced a second cartridge, which, I could see, had not been discharged.

"Somebody was waiting there to give a signal. There must have been two people in it at least," he said. And then: "He is dead, I suppose?"

I nodded. He shook his head and frowned.

"It's queer. I always thought he would come to an end like that. I don't know why. But there was a mystery about the man."

"Where is Veddle?" I asked, and he stared at me.

"Veddle? At the house, I suppose."

He turned and shouted to the two grooms who were some distance away. They had not seen Veddle. He sent one of them in search of the man.

Veddle had been in my mind ever since I had seen the body of Field with the sword of Tuna sticking through his back. I hadn't forgotten his threat nor his police record, and if there was one man in the world who had to account for every minute of his time that man was Mr. Veddle.

"I hadn't thought of him," said Voss slowly.

He knitted his white eyebrows again and laughed.

"It couldn't have been Veddle: I saw him—now, when did I see him?" He thought for a little time. "Now I come to think of it, I haven't seen him all the morning, but he's sure to be able to account for himself. He spends most of his time in the servants' hall trying to get off with my housemaid."

A few yards beyond the copse was a small pleasure-house which had a view of the river, and this was equipped with a telephone, which the groom must have used, for he came back while I was talking and reported that Veddle was not in the house and had not been seen. Mr. Voss brought his electric chair round, and I walked by its side back to the copse.

Locally it was called Tadpole Copse, and for a good reason, for it was that shape; large clumps that thinned off into a long tail, running parallel with the river and following its course downstream. It terminated on the edge of the property, where there was a narrow lane leading to the main road. It struck me at the time that it was quite possible for any man who had been hidden in the copse to have made a getaway without attracting attention even though the other bank of the river had been alive with policemen.

Voss went back to the house to make inquiries about his servant. He promised to telephone to me as soon as they were completed, and I returned to the boat and was ferried across to the house.

Two doctors were there when I arrived, and they said just the things you expect doctors to say... that Field had died instantly... that only a very powerful man could have killed him, and that it was a terrible business. They had brought an ambulance with them, and I sent the body away under Wills's charge and went on with my search of the desk.

I was really looking for keys. There were two locked rooms in the house, and at the moment I did not feel justified in breaking open any door until the servants returned.

I went round to the back of the house. The window of the locked room was set rather high and a blue blind was drawn down so that I could not see into it. Moreover, the windows were fastened on the inside. In all the circumstances I decided to wait till I found the key, or until the headquarters Surrey police, who were on their way, brought me a pick-lock.

Why had he sent his servants out that afternoon, and what could Marjorie Venn tell me when she came back? Somehow I banked upon the secretary more than upon the servants, because she would know a great deal more of his intimate life.

I went back to the desk and resumed my search amongst the papers. I was turning over the pages of an engineering report dealing with the Kwanga Mine when I heard a sound. Somebody was knocking, slowly and deliberately. I confess I am not a nervous man. Superintendents of police seldom are. If you're nervous you die before you reach the rank of sergeant. But this time I could feel my hair lift a little bit, for the knocking came from the door of the locked room.

THERE was no doubt about it: the sound of the knocking came from behind that locked door. I went over and tried the handle. I am a believer in miracles, and thought perhaps the knocker might have opened the door from the inside, but it was fast.

Then I heard a voice—the voice of a girl—cry "Help!" and the solution of that mystery came at once. I didn't wait for the keys to come; outside the kitchen door I had seen a big axe—in fact, I had thought that it might be useful in case of necessity. Going out, I brought in the axe and, calling the girl to stand aside, I had that door open in two minutes.

She was standing by a large, oriental-looking sofa, holding on to the head for support.

"You're Miss Marjorie Venn, aren't you?"

She couldn't answer, but nodded. Her face was like death; even her lips were almost white.

I set her down and got a glass of water for her. Naturally, as soon as she felt better she began to cry. That's the trouble with women: when they can be useful they become useless. I had to humour her, but it was about ten minutes before she could speak and answer my questions.

"How long have you been there?"

"Where is he?" she asked. "Has he gone?"

I guessed she was referring to Field. I thought at the moment it was not advisable to tell her that the late Mr. Field was just then on his way to a mortuary.

"He's a beast!" she said. "He gave me something in the coffee. You're a detective, aren't you?"

I had to tell her I was a superintendent. I mean, I'm not a snob, but I like to have credit for my rank.

It took a long time to get the truth out of her. She had lunched alone with Mr. Field, and he had become a little too attentive. Apparently it was not the first time that this had happened: it was the first time she had ever spoken about it. And it was only then she discovered that all the servants had been sent out.

As a matter of fact, she had nothing to tell me except what I could already guess. He had not behaved himself, and then he had changed his tactics, apologised, and she thought that the incident was over.

"I'm leaving to-night," she said. "I can't stand it any more. It's been terrible! But he pays me a very good salary and I couldn't afford to throw up the work. I never dreamt he would be so base. Even when the coffee tasted bitter I suspected nothing." And then she shuddered.

"Do you live here, Miss Venn?" I thought she was a resident secretary, and was surprised when she shook her head. She lodged with a widow woman in a cottage about half a mile away. She had lived at the house, but certain things had happened and he had left. It was not necessary for her to explain what the certain things were. I began to get a new view of Mr. Field.

She had heard nothing, could not remember being carried into the room. I think someone must have interrupted him and that he must have come out and locked her in.

Wills admitted to me afterwards that he had come down to the house and that Field had come out in a rage and ordered him to go to his post.

I thought, in the circumstances, as she was calmer, I might tell her what had happened. She was horrified; could hardly believe me. And then she broke into a fit of shuddering which I diagnosed as hysteria. This time it took her some time to get calm again, and the first person she mentioned was Wills, the detective.

"Where was he—when the murder was committed?" she asked.

I was staggered at the question, but she repeated it. I told her that so far as I knew Wills was on the road keeping watch.

"He was here, then!" she said, so emphatically that I opened my eyes.

"Of course he was here."

She shook her head helplessly.

"I don't understand it."

"Now look here, young lady," said I—and although I am not a family man, I have got a fatherly manner which has been highly spoken of —"what is all this stuff about Wills?"

She was silent for a long time, and then, womanlike, went off at an angle.

"It's dreadful... I can't believe it's true."

"What about Wills?" I asked again.

She brought her mind back to the detective.

"Mr. Field was sending him away to-day. He only found out this morning that he is the brother of that dreadful man—the convict."

"Veddle?" I said quickly, and she nodded.

"Did you know that it was Mr. Field who prosecuted Veddle the last time he went to prison? Or perhaps you didn't know he'd been to prison?"

I knew that all right, as I explained to her.

"But how did he find out that Wills was Veddle's brother?"

Field had found out by accident. He was rowing down the river, as he sometimes did, and had seen the two men talking together on the bank. They were on such good terms that he got suspicious, and when he returned he called Wills into his study and asked him what he meant by associating with a man of Veddle's character, and Wills had blurted out the truth. He hadn't attempted to hide the fact that his brother was an ex-convict. In fact, it was not until that moment really that Field remembered the man.

"Mr. Field told me," she went on, "that his attitude was very unsatisfactory, and that he was sending him away."

Just at that moment the deputy chief constable arrived by car and brought a crowd of bright young men, who had got all their detective science out of books. It was pitiful to see them looking for finger-prints and taking plaster casts of the naked foot, just like detectives in books, and measuring distances and setting up their cameras when there was nothing to photograph except me.

I told the chief all I knew of the case and got him to send the young lady back to her lodging in his car, and to get a doctor for her. One of his bright assistants suggested that we ought to hold her on suspicion, but there are some suggestions that I don't even answer, and that was one of them.

I went over with the deputy to see Mr. Voss, who had sent a message to say that he had heard from Veddle. The man had telephoned him from Guildford. Half-way across the field he came flying down to meet us. I must say that that electric bath-chair of his exceeded all the speed limits, and the wonder to me was that he hadn't been killed years before.

There are some gentlemen who should never be admitted into police cases, because they get enthusiastic. I think they get their ideas of crime out of books written by this fellow whose name I see everywhere. He wanted to know if we'd got any finger-prints, and his red face got purple when I told him about the young lady locked in the room.

"Scandalous! Disgraceful! By gad, that fellow ought to be horsewhipped!"

"He's been killed." I said, "which is almost as bad."

Then I asked him about Veddle.

"How he got to Guildford in the time I haven't the slightest idea. He must have had a car waiting for him. It's the most astounding thing that ever happened."

"What did he say?" I asked him.

"Nothing very much. He said he would be away for two or three days, that he'd got a call from a sick brother. Before I could say anything about the murder he hung up."

I decided to search the cottage where Veddle lived. It was on the edge of a plantation, and consisted of two rooms, one of which was a sort of kitchen-dining-room, the other a bedroom. It was plainly but well furnished. Mr. Voss, who couldn't get his machine through the door and shouted all his explanations through the windows, said he'd furnished it himself.

There was one cupboard, which contained an old suit and a new suit of clothes and a couple of pairs of boots. But what I particularly noticed was that Veddle hadn't taken his pipe away. It was lying on the table and looked as if it had been put down in a hurry. Another curious thing was a long mackintosh hanging behind the door. It was the longest mackintosh I have ever seen. On top of it was a black felt hat. I took down the mackintosh and, laying it on the bed, felt in the pockets—it is the sort of thing one does mechanically—and the first thing my fingers closed round was a small cylinder. I took it out. It was a smoke cartridge. I put that on the table and went on with the search.

One of the drawers of the bureau was locked. I took the liberty of opening it. It had a tin cash-box, which was unfastened, and in this I made a discovery. There must have been three hundred pounds in one-pound notes, a passport made out in the name of Wills—Sidney Wills, which was Veddle's real name—and a book of tickets which took him to Constantinople. There was a sleeper ticket also made out in the name of Wills, and the whole was enclosed in a Cook's folder, and, as I discovered from the stamp, had been purchased at Cook's west-end office the day before the murder.

There was a third thing in the drawer which I didn't take very much notice of at the time, but which turned out to be one of the big clues in the case. This was a scrap of paper on which was written:

"Bushes second stone's throw turn to Amberley Church third down."

I sent this to the deputy chief constable.

"Very mysterious," he said. "I know Amberley Church well; it's about eight miles from here. It's got a very famous steeple."

As I say, I didn't attach a great deal of importance to it. It was too mysterious for me. I put it in my pocket, and a few minutes afterwards I had forgotten it, when I heard that Wills, the detective, was missing.

THE disappearance of Wills rattled me. And I'm not a man easily rattled. Now and again you meet a crook detective, but mostly in books. I knew just what they'd say at Scotland Yard—they'd blame me for it. If a chimney catches fire, or a gas main blows up, the chief constable says to the deputy: "Why isn't the Sooper more careful?"

Wills hadn't done anything dramatic: he'd just walked to the station, taken a ticket to London and had gone. I got on to the Yard by 'phone, but of course he hadn't turned up then, and I placed the chief constable in full possession of all the facts; and from the way he said: "How did that come to happen, Minter?" I knew that I was half-way to a kick. If I wasn't one of the most efficient officers in the service, and didn't catch every man I was sent after, I should be blamed for their crimes.

I got one bit of evidence. After I'd finished telephoning and come out of the house, I found an assistant gardener waiting to see me. He had seen Veddle walking towards his cottage about the time of the murder. He had particularly noticed him because he wore a long mackintosh that reached to his heels and a black hat; the mackintosh had the collar up and the tab drawn across as though it were raining. This was remarkable because it was a fairly warm day. The gardener thought he was a stranger who was trying to find his way to the house, and had gone across towards him, when he recognised Veddle.

"From which way was he coming?"

"From Tadpole Wood," said the man. "I told Mr. Voss and he sent me on to tell you."

I liked Mr. Voss: he was a nice man. But the one thing that rattles me is the amateur detective. I suppose the old gentleman found time hanging on his hands, and welcomed this murder as a farmer welcomes rain after a drought. He was what I would describe as a seething mass of excitement. His electric chair was dashing here and there; he was down in Sanctuary Wood with half a dozen gamekeepers and gardeners, finding clues that would have baffled the well-known Shylock Holmes. He meant well, and that's the hardest thing you can say about any man.

He gave me one idea—more than one, if the truth be told. It was after I rowed across to Lone House and had come upon him and his searchers in the wood.

"Why do you trouble to row?" he said. "Why don't you get Garry Thurston to lend you his submarine?"

I thought he was joking, but he went on: "It's a motor-boat. I call it the submarine because of its queer build."

He told me that Garry had had the boat built for him to his own design. The river, though not an important one, is very deep, and leads, of course, to the Thames, where the Conservancy Board have a regulation against speeding. You're not allowed to use speedboats on the Thames, because the wash from them damages the banks and has been known to wreck barges.

As Garry was keen on speed, and had taken a natural science degree at Cambridge, he had designed a boat which offered him a maximum of speed with a minimum of wash.

"It honestly does look a submarine. There's only about four feet of it above water, and the driver's seat is more like a conning tower than a cockpit."

"Where does he keep it?" I asked.

Apparently he had a boathouse about two hundred yards from the Flash. We afterwards measured and found that it was exactly two hundred and thirty yards in a straight line from Lone House.

Mr. Voss was full of enthusiasm, and we went round the edge of the estate, touched a secondary road and in a very short time came to a big, green boathouse, but there was no boat there.

"He must be out in it," said Mr. Voss, a little annoyed, "but when he comes in—there he is!"

He pointed to the river, and I'll swear to you that although my sight is as good as any man's I couldn't see it.

The boat was moving against a green background, and as it was painted green it was almost invisible. If I hadn't seen Garry Thurston's head and his big face I would never have seen it at all. The top was shaped like a sort of whaleback. The whole boat seemed to be awash and sinking.

He came up to us, moving very quickly, and Garry waved his hand to us, brought the boat alongside and stepped out.

"I've been down to the river," he said, "and nearly had an accident—Field's nigger friends were rowing up and they fouled my bow."

I had heard about these strange negroes who came to see Field occasionally, and I was very much interested.

"When was this?" I asked.

He told me. It must have been half an hour before the murder was committed.

"They were lying under the bank, and the boy evidently decided to row across into one of the backwaters, and chose the moment I was hitting up a tolerable speed for this little river. I only avoided them by accident. Why doesn't Field bring his native pals in a purdah car?"

I thought it was a bright moment to tell him that John Field had met his death that afternoon. He wasn't shocked, did not even seem surprised, and when he said "Poor devil!" I did not think he sounded terribly sincere. Then he asked quickly: "Where was Miss Venn?"

"She was in the house," I said, and I saw his face go pale.

"Good God!" he gasped. "In the house when the murder was committed—"

I stopped him.

"She knew nothing about it—that's all I'm prepared to tell you. At least, she said she knew nothing about it."

"Where is she now?" It was Voss who asked the question.

He was more shocked by the fact that the young lady had been locked in the room, although I had told him before, than he was by the murder.

"Where is she now?" asked Garry. He looked absolutely ill with worry. I told him that I had sent her to her lodgings, and I think he'd have started right away if I hadn't pointed out that it wasn't quite the thing to go worrying the girl unless she had given him some right.

"And anyway," I said, "she's a police witness, and I don't want her interfered with."

I told him what I'd come for, and told him at the same time that his boat was quite useless for the purpose: it was too long and too full of odd contraptions for me to bother my head about. But he had what I had thought was a row-boat, under a canvas cover, but which proved to be a small motor dinghy, and with this he ran me down to the Flash, showing me in the meantime how to work it.

I hadn't by any means got through Field'spapers. In his pocket had been a bunch of keys. There was one odd-looking key for which I could find no lock. I discovered it that evening, when I was trying the walls of his study. Behind a picture, which swung out on hinges, I found the steel door of a safe. It was packed with papers, mostly of a business nature, and I was going through these carefully when Miss Marjorie Venn arrived. About tea-time I had sent her a note, telling her that when she was well enough I would like her assistance to sort out Field's papers. I didn't expect that she'd be well enough to come until the next day, but they telephoned, just before I began my search, to ask me if I would send the car for her.

She was quite calm; some of the colour had come back to her face; and I had a closer view of her than I had had that day on the bank, when Veddle had behaved like a blackguard. She was my ideal of what a woman should be: no hysterics, no swooning, just calm and sensible, which women so seldom are.

The servants had come back from the matinee, and I wanted to know exactly how I was to deal with them. She went out and saw them, and arranged that they were to stay on until further orders. A couple of the women, however, insisted on going home that night. She paid their wages out of money which she kept for that purpose.

There was no doubt about her being a help. She knew almost every document by sight, and saved me the trouble of reading through long legal agreements and contracts.

I sent for coffee when we were well into the work. It was while we were drinking this that she told me something about Field. He paid her a good salary, but she was in fear of him, and once or twice had been on the point of leaving him.

"I hate to say it of him, but he was absolutely unscrupulous," she said. "If he had not been a friend of my father's, and I was not obeying my father's wishes, I should never have stayed."

This was a new one to me, but apparently Field and Miss Venn's father had been great friends in South Africa. Lewis Venn had died there—died apparently within a year of Field finding his gold-mine.

"When Mr. Field came back I was about fifteen and at school. He paid for my education and helped my mother in many ways, and after dear mother's death he sent me to Oxford. I had never met him until then. He persuaded me to give up my studies and come and act as his private secretary. I was under that deep obligation to him—" She paused. "I think he has cancelled that," she said quietly.

Her father and Field had been poor men, who had wandered about Africa looking for mythical gold-mines. One day they came to a native village and discovered, under a heap of earth, an immense store of raw gold, the accumulation of centuries, which the natives had won from a river, and which had been handed on from chief to chief.

"The Chief of Tuna," she said. "This sword—" She stopped and shuddered. It was this that had put them on the track of the gold-mine.

"Mr. Field often spoke about it."

She stopped rather abruptly.

"Now I think we ought to get on with our work," she said.

It was five minutes after this that we made a discovery. There was a false bottom to the safe, and in this was a long envelope, and, written on the outside: "The Last Will and Testament of John Carlos Field." The envelope was sealed down; I broke the seal and opened it.

It was written on a double sheet of foolscap evidently in Field's own hand, and after the usual flim-flam with which legal documents began, it said: "I leave all of which I die possessed to Marjorie Anna Venn, of Clive Cottage, in this parish—"

"To me?" Marjorie Venn looked as if she had seen a ghost. She evidently couldn't believe what I was reading.

"If you're Marjorie Anna Venn—"

She nodded. "That is my full name." She spoke like somebody who had been running and was out of breath. "He asked me my full name one day, and I told him. But why—"

There was a big space under the place where he and the witnesses had signed, and here he had written a codicil, which was also witnessed.

"I direct that the sum of five hundred pounds shall be paid to my wife, Lita Field, and the sum of a thousand pounds to my son, Joseph John Field."

We looked at one another.

"Then he was married!" she said.

At this minute one of my men came in to see me. "There's a young man called. He says his name is Joseph John Field."

I pushed back my chair, as much astonished as the girl.

"Show him in," I said.

We didn't speak a word. And then the door opened, and there walked into the room a tall, young, good-looking negro.

"My name is Joseph John Field," he said.

DID I say I was not easily rattled? Well, I'm not. But I'd been rattled twice in one day.

I looked at the negro, I looked at Marjorie.

The boy—he was about nineteen—stood there motionless; there was no expression on his face or in his brown eyes.

"Joseph John Field?" I said. "You're not the son of John Field, who was the owner of this house?"

He nodded.

"Yes, I am his son," he said quietly. "My mother was the daughter of the Chief of Tuna."

I could only look at him. I thought these kinds of cases only existed in the minds of people who wrote cinema stories. But there was this negro, making a claim that was so preposterous that I simply couldn't believe him.

"Then your grandfather was the Chief of Tuna—I suppose you know that the Sword of Tuna—"

He interrupted me.

"Yes, I know that."

"Who told you?" I asked sharply.

He hesitated.

"A detective. He telephoned to my mother to-night."

"Wills?" I asked.

Again he hesitated.

"Yes, Mr. Wills. He has been a good friend of ours. He once saved my mother from—from being beaten by Mr. Field."

"Is your mother black?" I asked. There was no time to consider his feelings, but apparently he was one of these sensible negroes who didn't mind being described as black.

He shook his head.

"She is negroid, but she is almost as pale as a European."

He had the cultured voice of an English gentleman. I found afterwards that he had been educated at a public school, and was at that time at a university.

"Mr. Wills thought that I should come and see you, because, as mother and I were in the neighbourhood to-day, and we were known to have visited the house recently, suspicion might attach to us."

"It certainly does, young man," said I, and it was only then that I asked him if he'd sit down.

I could see Marjorie was listening, fascinated. The young man drew up a chair on the other side of the desk. He wore dark gloves and carried an ebony cane. His clothes were made by a good west-end tailor. He was in fact more like a real swell than any negro I've ever met. There was nothing ostentatious about his clothes, and, as I say, his voice was the voice of a gentleman.

He put his hand in his pocket, took out a leather case, opened it and handed me a folded paper. It was headed "March, 17th, being St. Patrick's Day, 1907, at the Jesuit Mission, Kobulu." Written in faded ink were the words: "I have this day, and in accordance with the rites of Holy Church, performed the ceremony of marriage between John Carlos Field, English, and Lita, daughter of Kosulu, Chief of Tuna, and issue this certificate in proof thereof."

"MICHAEL ALOYSIUS VALETTI, S.J.

Underneath was written:

"Confirmed.—MOROU, District Commissioner."

I handed the document mechanically to Miss Venn. She read it.

"This is your mother's marriage certificate," she said.

He nodded. "You are Miss Marjorie Venn? I've never seen you before, but I know you very well. My mother knew your father. They came to our village more than twenty years ago, my father and yours."

I thought it was a pretty good moment to ask him about Field's life in Africa, but the boy would tell me nothing, except that Field behaved very badly to his mother and had brought a number of tribes with him to attack the village and had killed the Chief—his father-in-law.

I was a little knocked out to find a buck negro claiming to be the son of a white man, but if I'd had any sense, I'd have realised that this is one of the jokes that nature plays in marriages of mixed colour. It was understandable now why Field invariably sent his servants away when his wife and son called upon him.

My first inclination was to admire the man for having done the right thing by this coloured son of his, but then I realised that he could not very well do anything else. I didn't suppose his wife blackmailed him, but the possibility of the fact leaking out that this country gentleman was married to a negress would be quite sufficient to make him pay well to keep her quiet.He could not even divorce her or allow her to divorce him without creating a scandal. I mentioned this fact to the boy, who agreed and said that Field had offered his mother a large sum of money to apply in the District Courts—I think they were Belgian—for a divorce, but his mother, having been mission-trained a Catholic, would not hear of divorce.

I wanted to get his reaction to the will, so I told him that he had been practically cut off, except for a thousand pounds. He wasn't a bit surprised, except that he had been left anything at all.

"Where did my father die?" the girl asked suddenly, but Joseph Field would say very little about what happened in Africa twenty-two years before. Possibly he did not know very much, though I am inclined to believe that he knew more than he was prepared to tell.

He did throw some sort of light on the cause of the quarrel between Field and the Chief of Tuna.

"My father had difficulty in locating the mine and came back and tried it again and again. He tried to persuade Kosulu—my grandfather—to let him have a share of the gold store which we kept in the village. Kosulu was Paramount Chief and the gold had been accumulating for centuries. It was to gain possession of this that he attacked the village—"

"Was my father in the attack?" asked the girl quickly.

Joseph Field shook his head.

"No, Miss Venn. The partnership had already been broken. Your father at the time was prospecting elsewhere. He did go back to the village after Kosulu was wounded and nursed him. John Field was bitterly disappointed because he had not been given the gold. He thought when he married my mother he would be able to take possession of the store. Mr. Venn at that time was a very sick man. My mother tells me he was planning to go to the coast to make his way back to what you call civilisation "—I saw him smile; I guess he had his own idea of civilisation. "It was on his way to the coast your father died."

I cross-examined him as to the number of times he and his mother had visited Lone House, but I could get nothing that helped me very much. They had only come once without invitation and that was the time that Wills had to intervene to save the woman from John Field's hunting crop.

There was nothing for me to do but to take his name and address. He and his mother lived in a flat in Bayswater and I told him that I would call to see them on the first available opportunity.

"What do you make of that?" I asked the girl when he had gone.

She shook her head.

I thought she looked rather sad and wondered why; not that I spend much time in analysing the emotions of females.

"Isn't it tragic, that poor boy with all the instincts of a gentleman and the colour of a ncgro?"

I told her negroes did not really mind their colour, if they were good negroes, and only the third-rate coon gets his inferiority complex working because he happens to be of a different shade from the man who is being executed next week for cutting his wife's throat. There is just as much sense in a white man getting rattled because he doesn't match up with Paul Robeson.

We did not do much more searching, but spent the next hour discussing Joseph John Field, and the part he may have played. I told her I knew that they had been in the neighbourhood that day and where I had my information from. When I mentioned Garry Thurston she went very pink and started very quickly to talk about his boat.

"It's curious," she said. "Mr. Field used to detest that motor-boat. I think it was because he hated being spied upon, as he called it, and he had an idea that Garry used to come down on to the Flash without being seen to—well, to see me."

"And did you see him very often?" I asked.

"He is a great friend of mine," she answered.

It's funny that you can never get a woman to give a straight answer to a straight question. However, it was not a subject that I wanted to pursue at the moment, so I let it drop.

The truth about John Field's relationship must come out at the inquest: I told Joseph that when I saw him off the premises, but he didn't seem much upset. It was clear to me that there was no love lost between him and his father. Generally when he referred to him he called him "John Field." I could see that the horsewhip incident was on his mind, and probably there were other incidents which nobody knew anything about.

It was easy to understand now why Wills was not popular with Field: he knew too much and probably presumed upon his knowledge. I guess that the woman must have told the detective that she was Field's wife.

An idea occurred to me suddenly.

"Do you mind if I ask you a delicate question. Miss Marjorie?" I said, and when she said no, I asked her if Field had proposed marriage to her.

"Three or four times," she said quietly, and I did not pursue the subject, because it might have been a very painful one for the young lady.

From what she told me it seemed that Field had lived almost the life of a hermit: he knew nobody in the neighbourhood and made no friends.

"Mr. Voss asked him to dinner once, but he refused. He tried to buy Hainthorpe—"

"Mr. Voss's house?"

She nodded.

"He hated people living so close to him and he had an idea of building a house on top of Jollyboy Hill; in fact, he offered Mr. Voss a very considerable sum of money through his agent for the hill alone, but the offer was not accepted."

There wasn't much more to be done that night. Mr. Voss had asked me to stay with him and, after seeing the young lady home,I got one of our men who understands engines to take me across the Flash. Here I found the little two-seater which Mr. Voss had put at my disposal: I don't understand motor-boats, but I can drive a car.

As I think I have explained, the house stands in a little stretch of meadow which is wholly encircled by trees. The path to the house is just wide enough to take a small car. The roads runs a little way through Tadpole Wood, through the thickest part of it. I was within a few yards of what I would call the exit, when I saw, by the reflection of my headlamps, somebody standing by the birch tree. Thinking it was one of the searchers, I slowed my car almost to a walk, and shouted:

"Do you want a lift?"

I had hardly spoken the words before the figure straightened itself and fired twice at me.

THE bullets stung past me so close to my face that I thought I had been hit. For a moment I stood paralysed with astonishment. It was the sight of the figure running that sort of brought me to life. I was out of the car in a second, but by this time he was out of sight. If I'd had the sense to bring my car round on a full lock, the lamps would have made it possible for me to see. As it was I was stumbling about in the dark with no chance of following my gentleman friend.

I think I ought to explain that Mr. Voss had made dozens of"walks" in Tadpole Wood and there were paths running in all directions—a real laby—what's the word? Maze. I went back to the car and got my hand lamp, which I should have taken before. I ought to have known that any kind of search was a waste of time, but a man who's been so fired at doesn't think as calmly as the chief constable sitting in his office (as I told him later). I hadn't any difficulty in finding where this bird had stood. I found the two shells of an automatic pistol lying on the grass. They were both hot when I found them. Naturally I kept them, because nowadays there is a new-fangled process by which you can identify from the cartridge the pistol that fired it, and I didn't think it was a satisfactory night's work. To go running through the wood was a waste of time—I realised that. The only hope was that the shots would have aroused one of Mr. Voss's gamekeepers and that the man might be seen. Apparently it had aroused them, but in the wrong direction. Their cottages were on the other side of the house and I met them running over the ground on my way to Hainthorpe. By the time I told them what had happened, I remembered that I had two or three detectives at Lone House who would want to know all about the shooting, and I turned back to see them. I was giving instructions about notifying the police stations around, with the idea of putting a barrage on the roads, when I heard two more shots fired in quick succession. They came from the direction of Hainthorpe. I got into the car again and flew up the road, not so fast as I might have done because I had police officers and gamekeepers piled into the machine or hanging on to the footboards.

The entrance of Hainthorpe is a great portico, and the first thing I saw in the lights of the motor lamps was a ladder lying across the drive. The house was in commotion. A servant, who looked scared sick, met me and asked me to come up to Mr. Voss's room. He took me in the elevator. Mr. Voss was sitting in bed. He was very red in the face, all his white hair was standing up and he was in his pyjamas.

"Look at that!" he roared send pointed to the curved bedhead.

It had been made of gilt wood, but now, for a space of about a foot, it was smashed to smithereens.

"They shot at me," he said.

(Did I say "he said"? He yelled it.)

"Look at that!"

Over the bed was a square hole in the wall that had shivered the plaster and sent it flying in all directions. The damage was so great that it didn't look like an automatic bullet that had done the work.

When he pointed to the French windows leading to the portico I understood why.

One window was smashed to smithereens, one was neatly punctured with a hole—both bullets must have started somersaulting the moment they touched the obstruction of the glass. I went out on to the top of the portico. It was surrounded by a low balustrade and had upon it a canvas awning—Mr. Voss used to be pushed out here to enjoy the sunlight and sometimes, he told me, he had slept there.

One of the cartridge cases I discovered on the balustrade, the other on the drive below the next morning.

When I got Mr. Voss quiet, he told me what happened. He had not apparently heard the first two shots that were fired at me, but he was awakened by the sound of a ladder being put against the portico. He sat up in bed and switched on the light.

"It was the most stupid thing I could have done, for the devil could see his target. The light was hardly on before—bang! I actually saw the glass smash... "

Though he was always regarded as a man of iron nerve, he was trembling from head to foot. One of the splinters from the wood had cut his right hand, which was wrapped up in a handkerchief. I wanted him to see a doctor about it, but he pooh-poohed the idea. I went downstairs whilst he dressed himself with the assistance of a servant, and after a while he came down the lift and wheeled himself into the library. He was much calmer and had enough theories to last him for the rest of the night.

I had all the servants in the house brought into the library one by one and questioned them. Nobody had seen the man who had done the shooting. The ladder was one belonging to the gardeners and was used in the orchard, but kept hanging near the house. I questioned everybody closely as to whether they had seen a pistol in the possession of Veddle. They were all very vague, except a gardener who had actually seen an automatic in Veddle's cottage. Mr. Voss was very emphatic on the point.

"There was no doubt at all," he said, "he had a pistol: I saw him practising with it once and told him to throw it into the river."

He told me then what he had never told me before: that in the course of the past year he had received two threatening letters written by anonymous correspondents.

"I didn't think it was worth while keeping them," he said. "They were written by some illiterate person, and I always suspected some gipsies I had turned off a corner of my land about this time last year."

"They were not in Veddle's handwriting?"

"No," he said slowly. "I don't think I have ever seen Veddle's handwriting now that you mention it."

I had the little scrap of paper in my pocket which I had taken from Veddle's cottage and I showed it to him. He examined the mysterious message it contained, reading out the words:

"Bushes second stone stop turn to Amberley Church third down."

I took the paper from him. I could have sworn that the third and fourth words were "stone's throw," but I saw I had made a mistake. Even with the change of the words it was as plain to me as it had been at first.

"I think that is Veddle's writing," he said.

"What does it mean?"

"I haven't the slightest idea," I said. "The point is: is the writing anything like the anonymous letters you received?"

He shook his head. "So far as I can remember, it isn't." He pulled out another handful of letters from his pocket, trying to find some note which Veddle had written to him. He was one of those careless men who keep money.letters and odd memoranda in one pocket. As he went through them in search of the letter he threw half of them away.

"I get my pockets full of this stuff," he said. "It is what I call a bachelor's wastepaper basket."

I stooped and fished into the real waste-paper basket, and handed him something he had thrown away. They might have been old bills, they were so sprinkled with ink, but I've got an instinct for money.

"You may be a rich man," I said, "but there is no reason why you should chuck your money into the wastepaper basket."

They were bank notes, three for ten pounds and one for twenty pounds.

He chuckled at his carelessness.

"Perhaps that is why Veddle always took personal charge of my wastepaper basket. I wonder how much the rascal has made out of my carelessness."

It was nearly four o'clock when I went up to my room, after a long talk with the chief constable on the wire.

I am one of those old-fashioned police officers who never have got out of their notebook habit. Give me a bit of a pencil and a paper and I can collect all my thoughts on one page. Here were the facts:

1. A very rich man, occupying a lonely house by the river, is killed. The only immediate clue is the impression on the earth outside of a naked footprint.

2. In the house at the time of the murder and locked up in a room is his private secretary, a girl to whom he had been making love although he was a married man. It was impossible that she could have locked the door herself, for the key of the room was found in the dead man's pocket when he was searched.

3. One of the detectives engaged to look after Field disappears, and we discover that he is the brother of Veddle—Mr. Voss's servant, a man who had a quarrel and a fight with Field and who threatened to get even with him.

4. Veddle and Wills disappear, but on the night following the murder, some person unknown appears in the grounds and fires at me and attempts to assassinate Mr. Voss.

5. Mr. Garry Thurston, who is in love with the secretary, possesses a boat which could approach the house unseen. He states, and this is confirmed, he was cruising along the little river at or near the time of the murder, and discovers a negress, who is Field's wife, and a young negro, who is Field's son, within striking distance of the house.

I wrote all this down, and the sun was shining through the windows by the time I had finished. I didn't feel like sleep. It's a queer thing—there is a point beyond which tiredness cannot go: you either drop into a heavy sleep where you sit, or you suddenly become as lively as a cricket. I had got to the cricket stage. I had a bath, shaved and, dressing myself, I went downstairs, unlocked the front door and stepped out. It was going to be a gorgeous day: the sun was up, the air was fresh and sweet. I decided to walk across the park towards Lone House. I knew the detectives would be there and some of them would be awake and could make me some coffee.

I stepped out very cheerfully, never dreaming that I was on the point of making a discovery which would change the whole complexion of the case.

As I think I told you, to reach the place where the river spreads out on a little lake one has to pass through Tadpole Wood. The birds were singing and it was the sort of morning somehow that you could not associate with police work, murders and midnight shootings.

I reached the spot where I had been fired at and, although I didn't expect to find anything, I had a sudden impulse to go off the path and make a search of the undergrowth. There was more than a possibility that I should find something which we had overlooked. I poked about with my stick in the undergrowth and in the grass and was turning to go when suddenly I saw two feet behind a bush; they were wide apart, the toes turned up. The man, whoever he was, must have been lying on his back.

I am not easily agitated, but there was something about these feet and their absolute stillness that sent a shiver down my spine. I walked quickly past the bush. Lying on his back was a man, his arms outstretched, his white face turned up to the sky. It was not necessary to see the blood on his throat to know that he was dead.

I stood looking at him, speechless. He was the one man I didn't expect to find murdered on that summer morning.

THE dead man was Veddle. He had been shot at close quarters, and the doctor who saw him afterwards said he must have been killed instantaneously.

What struck me at the moment was that he had not been killed in the place he was found. His attitude, the fact that there was little or no blood on the ground, and the fact that I found afterwards traces of a heavy body being dragged to behind the bushes, all put the O.K. to my first impression.

I didn't do any searching at the moment, but, running through the wood, I came to the water's edge, intending to call assistance from Lone House. The first thing I saw was Garry Thurston's queer-looking boat. It was moored to the bank, the painter tied to a tree, and its stern had drifted out so that it lay bow on to the bank. One of our men was on the lawn, and I shouted to him to come over. He travelled across in the little motor dinghy.

"How long has that boat been there?" I asked.

"I don't know. I saw it a quarter of an hour ago when I came out on to the lawn, and wondered what it was doing there. It belongs to Mr. Thurston, doesn't it?"

I wasn't worrying about the ownership of the boat at the moment, but took him up to the place where the body lay, and together we began our search.

He had heard nothing in the night, except that, just before daylight, he thought he heard the sound of a motor-car backfiring. It seemed a long way off, and nothing like the sound of the shots he had heard earlier in the evening.

Some rough attempt had been made to search Veddle's body, for the pockets of the jacket and the trousers pockets were turned inside out. It was in his hip pocket, on which he was lying, that we found the money—about two hundred pounds. The money was a bit of a shock to me, and upset all my previous calculations. It only shows how dangerous it is for an experienced police officer to make up his mind too soon.

"A hundred and eighty pounds," said the sergeant, counting it.

I put it in my pocket without a word.

We began to comb the wood, and in ten minutes we had found the place where the murder was committed. We should have known this by certain signs, but there was an already packed suitcase and an overcoat.

The place was about thirty yards from the drive which runs through Tadpole Copse, very near the spot where I had been shot at on the previous night.

There wasn't time to make more than a rough search of the suitcase, and that told us nothing.

I went down to the Flash and examined Garry Thurston's boat. The floor of the cockpit was covered with a rubber mat, of white and blue checks, and on these were the marks of muddy foot-prints. They weren't so much muddy as wet; it looked as if somebody had been wading in the water before they got into the boat.

Taking the motor dinghy, I went up to the boathouse. The gates facing the river were wide open; the little door on the land side was locked. I knew, because Garry Thurston had told me, that the gates opened automatically by pulling a lever on the inside of the boathouse, and they could only be opened from the inside. The boathouse itself was supported on piles, and I saw at once that it was possible for anybody who would take the risk to dive under its edge and climb up inside. I told the detective to take the suitcase across to Lone House, and, taking the police car, I drove up to Dobey Manor, where Mr. Garry Thurston lived.

It was an old Elizabethan manor house, one of the show places of the county. I am not very well acquainted with the habits of the non-working classes, and I expected it would take me an hour to make anybody hear at that time of the morning. But the first person I saw when I got out of the car was Mr. Thurston himself. He was up and dressed, and by the look of him I guessed he had not been to bed all night. He was unshaven, and his eyes had one of those tired, poker party looks.

"You're up early, Mr. Thurston," I said,and he smiled.

"I haven't been to bed all night. In fact I've only just come in." And then, abruptly: "Have they found Veddle?"

That was the one question I didn't expect him to put to me, and I was a little taken aback. The one person I didn't think he would be interested in was Veddle.

"Yes, we've found him," I replied.